Addressing a Sibling Rivalry: In Seeking Effective Christian–Muslim Relations, to What Extent Can Comparative Theology Contribute? An Evangelical Christian Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Aims and Objectives

- To identify underlying issues within relations and current trends in Christian–Muslim exchanges.

- To critically evaluate CT and its ability to navigate truth claims and peace. Evaluation extends to potential barriers within CT, including the following:

- ‘Epistemological preconceptions’ within TOR;

- The extent of ‘learning from’ another tradition as a source of meaning.

- To explore other disciplines that could contribute to understanding aspects associated with ‘people of faith’.

- To formulate recommendations for developing more effective relations and a deeper understanding of each other’s faith.

1.2. Methodology

- Descriptive–empirical task;

- Interpretive task;

- Normative task;

- Pragmatic task.

- Descriptive–interpretative task: by asking ‘what is going on and why?’, factors affecting Christian–Muslim relations are considered.

- Normative task: a critical analysis of CT and if, or how, it might contribute to effective Christian-Muslim relations within theological enquiry regarding the question ‘what should be going on?’.

- Theoretical-contribution task: in asking ‘what could be going on?’, concepts from the social sciences are explored, specifically in relation to attitude, epistemology, and psychology.

- Pragmatic task: recommendations are sought in order to contribute to developing more effective Christian–Muslim relations.

1.3. Significance

2. Descriptive–Interpretative Task

2.1. Analysing Approaches

2.2. Confrontational Approach

2.2.1. Theological Difference

2.2.2. Approaching Each Other’s Scripture

2.2.3. ‘Educating’ Ourselves

2.2.4. Approaching Each Other

2.3. Conciliatory Approach

2.3.1. Historical and Socio-Political Issues

2.3.2. Scriptural Reasoning

2.4. Summary

3. Normative Task

3.1. Comparative Theology

3.2. What Truth?

- Exclusivism—denies the presence of relevant truth of other religions;

- Particularism—suspends judgement on another’s epistemological status given the incommensurability of competing claims;

- Closed inclusivism—recognises possible elements of truth in another religion but fullness in one’s own;

- Open inclusivism—discovers new forms and expressions of truth in another religion, when not contradictory to one’s own;

- Pluralism—based on the equivalence of all religions in matters of truth;

- Post-colonialism—deems religious boundaries as hegemonic.

3.3. Where Is Meaning?

3.4. Whose CT?

3.5. Summary

4. Theoretical-Contribution Task

4.1. ‘Exclusivism Is Intolerant’

4.2. The Certainty Trap

4.3. The Interpretation Gap

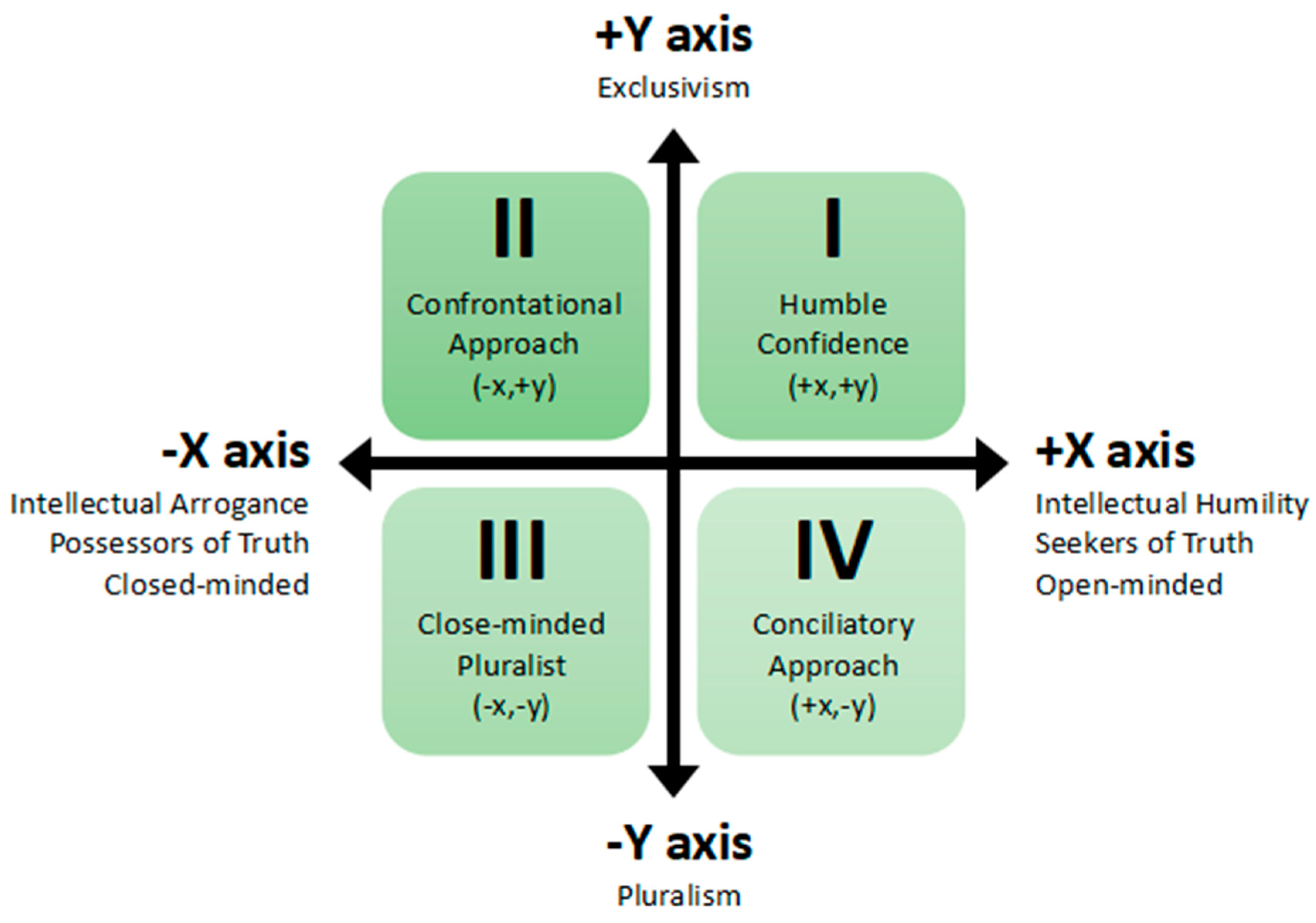

4.4. Attitudes Are Everything

4.5. Diverging ‘Solutions’

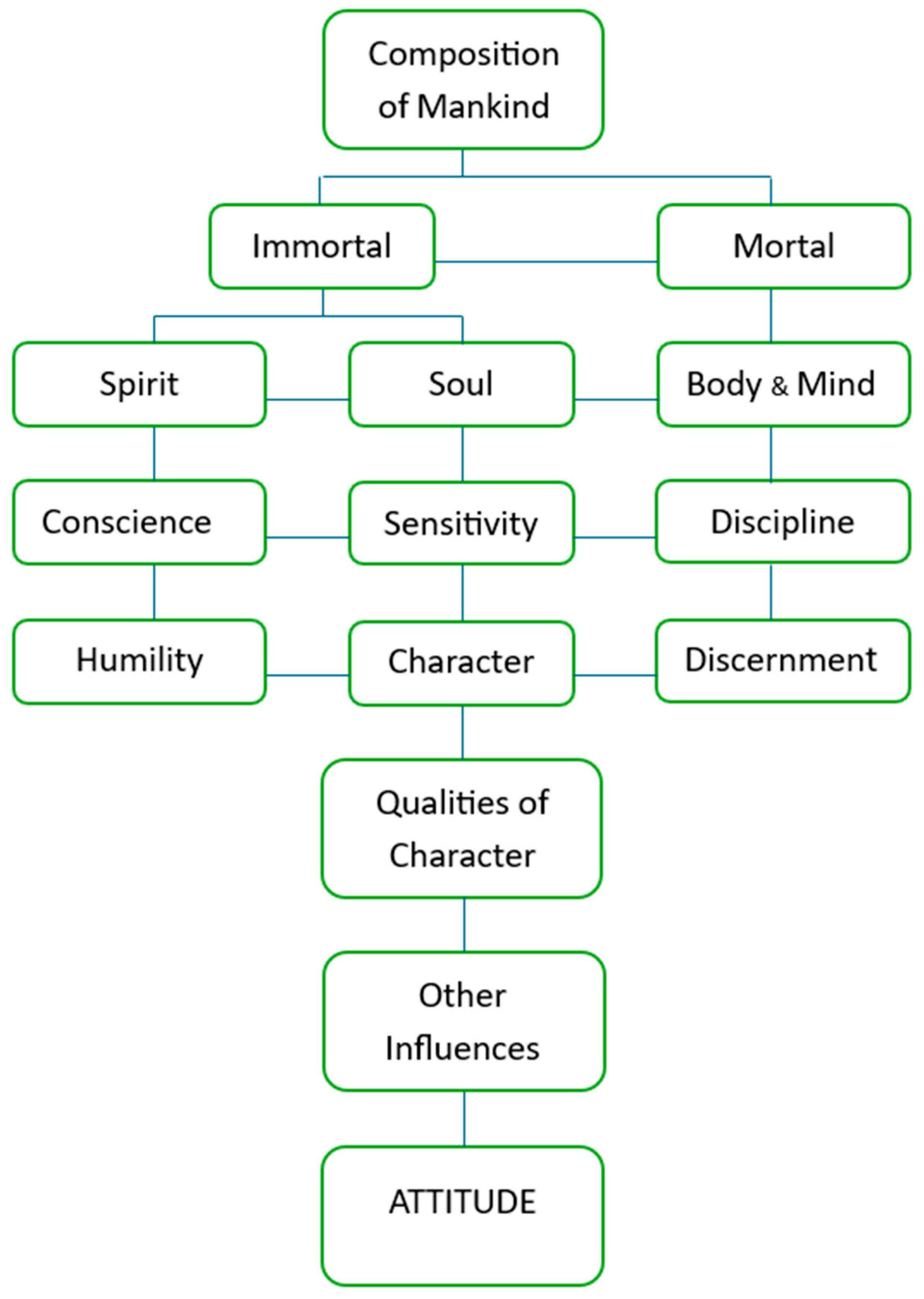

4.6. A Christian Understanding of Attitude

4.7. Humble Confidence

4.8. Summary

5. Pragmatic Task

5.1. Two-Dimensional

5.2. Orientation

5.3. ‘+x’ of CT

5.4. ‘−y’ of CT

5.4.1. Recommendation One: CT and Holistic Missiology

5.4.2. Recommendation Two: CT, Hermeneutics, Contextualisation and Flexibility

5.5. People of Faith

5.5.1. Recommendation Three: Embracing Healthy Disagreement

5.5.2. Recommendation Four: Improved Classification in Exchange

5.5.3. Recommendation Five: Using CT in SR

5.5.4. Recommendation Six: ‘Mind the Gap’

5.6. Ultimate Motivation

6. Conclusions

6.1. Reviewing Objectives

6.1.1. Objective One: Identify Underlying Issues Within Christian–Muslim Relations

6.1.2. Objective Two: Critically Evaluate CT

6.1.3. Objective Three: Explore Other Disciplines in Relation to ‘People of Faith’

6.1.4. Objective Four: Formulate Recommendations

- CT needs a holistic missiology, including TOR employing soteriological criteria, and accommodation for apologetics.

- CT needs flexibility in hermeneutics and contextualisation, allowing for prioritisation of the authority of scripture.

- Embracing healthy disagreement.

- Improved classification in exchange.

- Using CT to inform SR.

- ‘Mind the gap’ between God and our theological claims about God.

6.2. Sibling Implications

6.3. Future Directions

6.4. Limitations

6.5. Final Reflection

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Accad, Martin. 2019. Sacred Misinterpretation. Reaching across the Christian-Muslim Divide. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Accad, Martin. 2020. Developing a Biblical Theology of Islam: A Practical Missiology Based on Thoughtful Theology, Moving Beyond Pragmatic Intuition. In The Religious Other: A Biblical Understanding of Islam, the Qur’an and Muhammad. Edited by Martin Accad and Jonathan Andrews. Carlisle: Langham Global Library, pp. 124–34. [Google Scholar]

- Accad, Martin, and Jonathan Andrews, eds. 2020. The Religious Other: A Biblical Understanding of Islam, the Qur’an and Muhammad. Carlisle: Langham Global Library. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, Domenik. 2023. Mosaic Tiles: Comparative Theological Hermeneutics and Christian-Jewish Dialogue About the Land. Cross Currents 73: 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Rumee. 2013. Scriptural reasoning and the Anglican-Muslim encounter. Journal of Anglican Studies 11: 166–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay-Dağ, Esra. 2017. Christian and Islamic Theology of Religions: A Critical Appraisal, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Shabbir. 2018. The New Testament in Muslim Eyes. London: Routledge. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/1567579 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Albaghli, Bashar, and Leonardo Carlucci. 2021. The Link between Muslim Religiosity and Negative Attitudes toward the West: An Arab Study. The International Journal for The Psychology of Religion 31: 235–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar-Zadeh, Darius. 2019. Interreligious Peacebuilding through Comparative Theology. International Journal on World Peace 36: 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Atoi, Ewere Nelson. 2018. The Epistemology of Truth-Claims in the Global Multi-Religious Ambiance. Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 28: 129–47. [Google Scholar]

- Avci, Betül. 2018a. Comparative Theology: An Alternative to Religious Studies or Theology of Religions? Religions 9: 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, Betül. 2018b. Comparative Theology and Scriptural Reasoning: A Muslim’s Approach to Interreligious Learning. Religions 9: 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, Betül. 2021. The Qur’ānic View of History, Revelation, and Prophethood: An Exercise in Comparative Theology. Journal of Ecumenical Studies 56: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baatsen, Ronald Allen. 2017. The will to embrace: An analysis of Christian-Muslim relations. HTS Theological Studies 73: 33–90. [Google Scholar]

- Banas, Mark. 2021. Meaning and Method in Comparative Theology by Catherine Cornille (review). Journal of Ecumenical Studies 56: 149–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, Andy. 2021. Do Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God? London: Inter-Varsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew, Craig G. 2015. Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics: A Comprehensive Framework for Hearing God in Scripture. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Bauckham, Richard. 2016. The Bible in the Contemporary World: Exploring Texts and Contexts—Then and Now. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, David. 2021. The Evangelical Quadrilateral. Baylor: Baylor University Press. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/2935931 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Bengard, Beate. 2021. Echanges Apres. In La théologie comparée: Vers un dialogue interreligieux et interculturel renouvelé? Edited by Christophe Chalamet, Elio Jaillet and Gabriele Palasciano. Geneva: Editions Labor et Fides, (Unpublished editors translation utilised in dissertation, kindly provided by Dr. Christophe Chalamet, April 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Clinton. 2008. Understanding Christian-Muslim Relations, 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Matthew Aaron. 2022. The Qur’an and the Christian, An In-Depth Look into the Book of Islam for Followers of Jesus. Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, Matthew A. 2021. Disagreement and Religion. In Religious Disagreement and Pluralism. Edited by Mathew A. Benton and Jonathan L. Kvanvig. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Jan Albert Van Den. 2017. Tweeting dignity: A practical theological reflection on Twitter’s normative function. HTS Theological Studies 73: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bevans, Stephen B. 2002. Models of Contextual Theology. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Beyers, Jaco. 2018. Scriptural reasoning: An expression of what it means to be a Faculty of Theology and Religion. HTS Theological Studies 74: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, David Jacobus. 2012. Transforming Mission Bosch Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission, 2nd ed. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Daniel. 2020. Where Do Scriptures Come From? In The Religious Other: A Biblical Understanding of Islam, the Qur’an and Muhammad. Edited by Martin Accad and Jonathan Andrews. Carlisle: Langham Global Library, pp. 257–73. [Google Scholar]

- Carducci, Bernado. 2015. Psychology of Personality. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/3866321 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Centre Muslim-Christian Studies. 2023. The Oxford Muslim-Christian Summer School—More Than Your Usual Interfaith Encounter. Available online: https://www.cmcsoxford.org.uk/studying/summer-courses (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Christman, Bryan M. 2022. Lewis and Kierkegaard as Missionaries to Post-Christian Pagans. Evangelical Review of Theology 46: 123–36. [Google Scholar]

- Clooney, Francis Xavier. 2001. Hindu God, Christian God: How Reason Helps Break Down the Boundaries Between Religions. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clooney, Francis Xavier. 2008. Beyond Compare: St. Francis de Sales and Srí Vedānta Deśika on Loving Surrender to God. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/949567 (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Clooney, Francis Xavier. 2010a. Comparative Theology: Deep Learning Across Religious Borders. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Clooney, Francis Xavier. 2010b. The New Comparative Theology: Interreligious Insights from the Next Generation. London and New York: T&T Clark International. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/817859/the-new-comparative-theology-interreligious-insights-from-the-next-generation-pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Clooney, Francis Xavier. 2011. Comparative Theology. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/1013710 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Clooney, Francis Xavier. 2021. Clearing the Way: On the Future of Comparative Theology. In La théologie comparée: Vers un dialogue interreligieux et interculturel renouvelé? Edited by Christophe Chalamet, Elio Jaillet and Gabriele Palasciano. Geneva: Editions Labor et Fides, pp. 1–40, (Unpublished editors translation utilised in dissertation, kindly provided by Dr. Christophe Chalamet, April 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Cornille, Catherine. 2017. Soteriological Agnosticism and the Future of Catholic Theology of Interreligious Dialogue. In The Past, Present, and Future of Theologies of Interreligious Dialogue. Edited by Terrence Merrigan and John Friday. Oxford: Oxford Academic, pp. 201–15. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198792345.003.0013 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Cornille, Catherine. 2020. Meaning and Method in Comparative Theology. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Crowson, Michael H. 2009. Does the DOG Scale Measure Dogmatism? Another Look at Construct Validity. The Journal of Social Psychology 149: 265–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, Joseph. 2008. Toward Respectful Witness. In From Seed to Fruit: Global Trends, Fruitful Practices, and Emerging Issues among Muslims. Edited by Dudley Woodberry. Pasadena: William Carey, pp. 311–23. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/3294922 (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Custer, William L. 2022. Forty Years of Progress in Christian Apologetics: An Atheist Changes His Mind. Stone-Campbell Journal 25: 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Dadosky, John D., and Christian S. Krokus. 2022. What Are Comparative Theologians Doing When They Are Doing Comparative Theology? A Lonerganian Perspective with Examples from the Engagement with Islam. Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 32: 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Degner, Samuel. 2020. Christian Apologetics in a Post/Modern Context. Wisconsin Lutheran Quarterly 117: 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Denffer, Admad Von. 2011. Ulum al Qur’an: An Introduction to the Sciences of the Qur’an (Koran). Leicestershire: The Islamic Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- DePoe, John M. 2022. Classical Evidentialism. In Debating Christian Religious Epistemology. An Introduction to Five Views on the Knowledge of God. Edited by John M. DePoe and Tyler D. McNabb. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- DePoe, John M., and Tyler D. McNabb. 2022. Debating Christian Religious Epistemology, An Introduction to Five Views on the Knowledge of God. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Dormandy, Katherine. 2020. The Epistemic Benefits of Religious Disagreement. Religious Studies 56: 390–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, David. 2013. Scriptural reasoning: Its Anglican origins, its development, practice and significance. Journal of Anglican Studies 11: 147–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, Ida. 2005. The Bible and Other Faiths, Christian Responsibility in a World of Religions. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, Hugh. 2020. A History of Christian-Muslim Relations, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goheen, Michael W. 2014. Introducing Christian Mission Today: Scripture, History and Issues. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson, Jacob. 2021. The Philosopher’s Playground, Understanding Scriptural Reasoning through Modern Philosophy. Eugene: Cascade Books: Wipf and Stock Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gov.uk. 2022. 16 Faith Groups to Share £1.3 Million ‘New Deal’ Fund to Help Support Communities. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/16-faith-groups-to-share-13-million-new-deal-fund-to-help-support-communities (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Green, Todd. 2019. Interfaith Etiquette in an Age of Islamophobia. Dialog 58: 212–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greifenhagen, Franz Volker. 2010. Scripture Wars: Contemporary Polemical Discourses of Bible Versus Quran on the Internet. Comparative Islamic Studies 6: 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grierson, Bruce. 2023. The Certainty Trap. Psychology Today 56: 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Groothuis, Douglas. 2000. Truth Decay: Defending Christianity Against the Challenges of Postmodernism. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hackney, Charles. 2021. Positive Psychology in Christian Perspective. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/2984260 (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind, Why Good People Are Divided by Politics And Religion. London: Penguin Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, Paul. 2023. Comparative Theology On and In Place: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Cross Currents 73: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, Mark. 2019. Comparative Theology at Twenty-Five: The End of the Beginning. Modern Theology 35: 163–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, Mark. 2020. Paths to Wholeness: Comparative Theology and the Ecumenical Project. Journal of Ecumenical Studies 55: 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, Dennis. 2019. Clothing Christian Convictions in Intellectual Humility. Cultural Encounters 15: 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Imbert, Yannick. 2023. Apologetics and Mission: Western European Hope and Values. European Journal of Theology 32: 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interfaith.org.uk. 2024. INF Funding. Available online: https://www.interfaith.org.uk/about/ifn-funding (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Isgandarova, Nazila. 2014. Practical theology and its importance for Islamic theological studies. Ilahiyat Studies 5: 217–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam Newsroom. 2022. Jesus-Test (That Christians FAIL). Available online: https://www.islamnewsroom.com/news-we-need/1349-jesus-test-who-failed (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti. 2013. Christ and Reconciliation. A Constructive Christian Theology for the Pluralistic World. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti. 2020. Doing the Work of Comparative Theology. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, Mohammad Hassan. 2012. Islam and the Fate of Others: The Salvation Question. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Adil Hussain, and Michael A. Cowan. 2018. Why Christian-Muslim “Dialogue” Is Not Always Dialogical. Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 28: 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Khorchide, Mouhanad, and Klaus Von Stosch. 2019. The Other Prophet: Jesus in the Qur’an. London: Gingko Library. [Google Scholar]

- Kiblinger, Kristin Beise. 2010. Relating Theology of Religions and Comparative Theology. In The New Comparative Theology: Interreligious Insights from the Next Generation. Edited by Francis Xavier Clooney. London and New York: T&T Clark International, pp. 21–42. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/817859/the-new-comparative-theology-interreligious-insights-from-the-next-generation-pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Klein, William W., Craig L. Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard. 2017. Introduction to Biblical interpretation, 3rd ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Knitter, Paul F. 2002. Introducing Theologies of Religions. New York: Orbis. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, James. 2012. The Epistemology of Religious Disagreement. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/3507953 (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Kuiper, Matthew J. 2021. Da’wa: A Global History of Islamic Missionary Thought and Practice. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Legenhausen, Muhammad. 2023. Comparative Theology in the Islamic Sciences. Journal of Philosophical Theological Research 25: 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Philip, and Sadek Hamid. 2018. British Muslims, New Directions in Islamic Thought, Creativity and Activism. Edinburgh: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Love, Christopher W. 2021. The Epistemic Value of Civil Disagreement. Social Theory & Practice 47: 629–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Kristi. 2019. More> Truth, Searching for Certainty in an Uncertain World. London: Inter-Varsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, Simle. 2022. COVID-19 and Orthodoxy: Uncertainty, Vulnerability, and the Hermeneutics of Divine Economy. Analogia 17: 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, David. 2006. Heavenly religion or unbelief? Muslim perspectives on Christianity. Anvil 23: 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Massad, Alexander E. 2020. Who Is the Other? Reconsidering “Salvation” through Classical Islamic Thought. In The Religious Other: A Biblical Understanding of Islam, the Qur’an and Muhammad. Edited by Martin Accad and Jonathan Andrews. Carlisle: Langham Global Library, pp. 341–55. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, Richard. 2020. Something New, Something Old: The Challenge of Religious Diversity. In The Religious Other: A Biblical Understanding of Islam, the Qur’an and Muhammad. Martin Accad and Jonathan Andrews. Carlisle: Langham Global Library, pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, Richard. 2024. Evangelical Christian Responses to Islam. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/4300803/evangelical-christian-responses-to-islam-a-contemporary-overview-pdf (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- McCann, Hilton. 2021. The Psychology of Attitude. London: Austin Macauley Publishers. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/3122146 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- McGrath, Alister. 2016. Mere Apologetics: How To Help Seekers And Sceptics Find Faith. London: SPCK. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1233308&site=ehost-live (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Meister, Chad. 2010. Philosophy of Religion. In The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion, 2nd ed. Edited by John R. Hinnells. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 111–20. [Google Scholar]

- Melnik, Sergey. 2020. Types of Interreligious Dialogue. The Journal of Interreligious Studies 31: 48–72. [Google Scholar]

- Meulenberg, Michal. 2023. Muslim-Evangelical Interfaith Programming: Are People Actually Changing? Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ab2686bcef37284f39cbe8b/t/649aefe049682465077fc56a/1687875552480/Muslim-Evangelical+Interfaith+Programming++Are+people+actually+changing+Michal+Meulenberg%2C+PhD.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Migliore, Daniel L. 2014. Faith Seeking Understanding—An Introduction to Christian Theology. Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Moreland, Anna Bonta. 2022. Comparative theology: A wellness checkup. Modern Theology 39: 121–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyaert, Marianne. 2012. Recent developments in the theology of interreligious dialogue: From soteriological openness to hermeneutical openness. Modern Theology 28: 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyaert, Marianne. 2017. Ricoeur, Interreligious Literacy, and Scriptural Reasoning. Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 27: 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Muck, Terry C. 2020. A Theology of Interreligious Relations. International Bulletin of Mission Research 44: 320–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Jeff. 2022. Truth Changes Everything. Perspectives: A Summit Ministries Series; Ada: Baker Books. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/3294209 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Newbigin, Lesslie. 1990. The Gospel in a Pluralist Society. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Newbigin, Lesslie. 1995a. The Open Secret—An Introduction to the Theology of Mission. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Newbigin, Lesslie. 1995b. Proper Confidence: Faith, Doubt and Certainty in Christian Discipleship. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Gary. 2012. Heart-Deep Teaching: Engaging Students for Transformed Lives. Nashville: B&H Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson, Hugh. 2010a. The New Comparative Theology and Theological Hegemonism. In The New Comparative Theology: Interreligious Insights from the Next Generation. Edited by Francis Xavier Clooney. London and New York: T&T Clark International, pp. 43–63. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/817859/the-new-comparative-theology-interreligious-insights-from-the-next-generation-pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Nicolson, Hugh. 2010b. Comparative Theology and the Problem of Religious Rivalry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ons.gov.uk. 2024. Office for National Statistics Census Data 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/religion/articles/religionbyageandsexenglandandwales/census2021# (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Osborne, Grant R. 2006. The Hermeneutical Spiral: A Comprehensive Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. Downers Grove: IVP. [Google Scholar]

- Osmer, Richard R. 2008. Practical Theology: An Introduction. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Pachuau, Lalsangkima. 2022. God at Work in the World, Theology and Mission in the Global Church. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanasiou, Athanasios N. 2014. Is Comparative Theology Orthodox? Studies in Interreligious Dialogue 24: 104–18. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanasiou, Athanasios N. 2021. An inquiry into the tension between faith, hospitality, and witness. Reflections on Comparative Theology from an Orthodox point of view. International Journal of Orthodox Theology 12: 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Parshall, Phil. 2003. Muslim Evangelism, Contemporary Approaches to Contextualization, 2nd ed. Waynesbro: Gabriel Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, Colin. 2019. What has Eschatology to do with the Gospel? An analysis of papal documents on mission ad gentes. Missiology 47: 285–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piretti, Luca, Edoardo Pappaianni, Alberta Lunardelli, Irene Zorzenon, Maja Ukmar, Valentina Pesavento, Raffaella Ida Rumiati, Remo Job, and Alessandro Grecucci. 2020. The Role of Amygdala in Self-Conscious Emotions in a Patient with Acquired Bilateral Damage. Frontiers in Neuroscience 14: 677. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.00677/full (accessed on 17 August 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piwko, Aldona, Zofia Sawicka, and Andrzej Adamski. 2021. Islamic Doctrine on Mass Media: From Theological Assumptions to the Practical Ethics of the Media. Journal for the Study of Religion & Ideologies 20: 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Lucinda, and Alita Nandi. 2020. Ethnic diversity in the UK: New opportunities and changing constraints. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 46: 839–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, Elizabeth M., and Trena M. Paulus. 2023. Agree to Disagree? Allowing for Ideological Difference during Interfaith Dialogue Following Scriptural Reasoning. Journal of Ecumenical Studies 58: 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, Douglas. 2021. Contemporary Christian-Muslim Dialogue. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/2096215/contemporary-christianmuslim-dialogue-twentyfirst-century-initiatives-pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Ralston, Joshua. 2020. Law and the Rule of God. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/4223301 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Ralston, Joshua. 2022. At the Border of Christian Learning: Islamic Thought and Constructive Christian Theology. Interpretation 76: 117–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, Paul. 2016. The Psychology of Conflict: Mediating in a Diverse World. Bloomsbury: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Reitsma, Bernhard J. G. 2020. Vulnerable Love. Islam, the Church and the Triune God. Carlisle: Langham Global Library. [Google Scholar]

- Rooms, Nigel. 2012. Paul as Practical Theologian: Phronesis in Philippians. Practical Theology 5: 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, Andrew. 2009. Practical theology: What is it and how does it work. The Journal of Youth Ministry 7: 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Andrew. 2016. Regulating the Empirical in Practical Theology: On Critical Realism, Divine Action, and the Place of the Ministerial. Journal of Youth and Theology 15: 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabates, Angela M. 2022. The ABC’s of Christians’ Anti Muslim Attitudes: An Application of Eagly and Chaiken’s Attitude Theory. Journal of Psychology and Theology 50: 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Abdullah. 2013. New Directions in Islamic Education Pedagogy and Identity Formation. Leicestershire: Kube Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger, Jamie. 2012. Intellectual humility and interreligious dialogue between Christians and Muslims. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 23: 363–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmacher, Thomas. 2020. Observations on Apologetics and Its Relation to Contemporary Christian Mission. ERT 44: 359–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schlabach, Gerald W. 2018. Christian Peace Theology and Nonviolence toward the Truth: Internal Critique amid Interfaith Dialogue. Journal of Ecumenical Studies 53: 541–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejdini, Zekirija. 2022. Rethinking Islam in Europe: Contemporary Approaches in Islamic Religious Education and Theology. Berlin: De Gruyter. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=3113686&site=ehost-live (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Shumack, Richard. 2020. Jesus Through Muslim Eyes. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Thomas W. 2023. Faith as Trust. The Monist 106: 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, James A. K. 2012. The Fall of Intrepretation, Philosophical Foundations for a Creation Hermeneutic, 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Sam. 2010. Challenges from Islam. In Beyond Opinion. Edited by Ravi Zacharias. Nashville: Thomas Nelson, Sam Soloman section. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/554107/beyond-opinion-pdf (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Solomon, Sam. 2016. Not the Same God, Is the Qu’ranic Allah the Lord of the Bible? London: Wilberforce Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Springs, J. A. 2020. Healthy Conflict in an Era of Intractability: Reply to Four Critical Reponses. Journal of Religious Ethics 48: 316–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenmark, Mark. 2006. Exclusivism, Tolerance and Interreligious Dialogue. Studies in Interreligous Dialogue 16: 100–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosch, Klaus Von. 2012. ‘Comparative Theology as Liberal and Confessional Theology. Religions 3: 983–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, Daniel. 2021. On Being Soteriologically De-motivated. Themelios 46: 494–502. [Google Scholar]

- Takacs, Axel Oakes, and Joseph Kimmel. 2023. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Comparative Theology, A Festschrift in Honor of Francis X. Clooney, SJ. London: Wiley-Blackwell. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/4233569 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Tennent, Timothy C. 2002. Christianity at the Religious Round Table: Evangelicalism in Conversation with Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=992596&site=ehost-live&ebv=EB&ppid=pp_29 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Tennent, Timothy C. 2014. Postmodernity, the paradigm and the pre-eminence of Christ. The Evangelical Quarterly 86: 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatamanil, John. 2020. Integrating Vision: Comparative Theology as the Quest for Interreligious Wisdom. In Interreligious Education, Experiments in Empathy. Edited by Heidi Hadsell and Najeeba Syeed. Boston: Brill Rodopi, Leiden, pp. 100–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tieszen, Charles. 2020. The Christian Encounter with Muhammad, 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Toren, Benno Van Den, and Kang San Tan. 2022. Humble Confidence, A Model for Interfaith Apologetics. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Toren, Benno Van Den. 2023. Openness, Commitment, and Confidence in Interreligious Dialogue: A Cultural Analysis of a Western Debate. Religions 14: 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, Olli Pekka. 2021. Luther’s Theological Ontology and the Contemporary Discussion Concerning Relational Ontology. Kerygma und Dogma 67: 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoozer, Kevin J. 2004. Exegesis and Hermeneutics. In New Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Edited by Desmond T. Alexander and Brian S. Rosner. Leicester: IVP, pp. 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Pete. 2017. Introducing Practical Theology: Mission, Ministry, and the Life of the Church. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. Available online: https://belbib.overdrive.com/media/3188017 (accessed on 17 December 2023).

- Webster, Joseph. 2022. Nor shadow of turning: Anthropological reflections on theological critiques of doctrinal change. Australian Journal of Anthropology 33: 360–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Ethan Doyle. 2019. Christianity, Islam, and the UK Independence Party: Religion and British Identity in the Discourse of Right-Wing Populists. Journal of Church & State 61: 381–402. [Google Scholar]

- Whittingham, Martin. 2022a. Christian Theological Reflection on Muslim Views of the Bible. Islamochristiana 48: 141–55. [Google Scholar]

- Whittingham, Martin. 2022b. A History of Muslim Views of the Bible, 1st ed. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Wier, Andy. 2017. From the Descriptive to the Normative: Towards a Practical Theology of the Charismatic-Evangelical Urban Church. Ecclesial Practices 4: 112–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Glenn R. 2018. On Some Suspicions Regarding Comparative Theology. In How to Do Comparative Theology. Edited by Francis Xavier Clooney and Klaus Von Stosch. New York: Fordham University, pp. 122–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, David. 2022. A Question No Muslim Can Answer (Prove Me Wrong!). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4of-PbRvdqo (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Zebiri, Kate. 2013. Muslim Perceptions of Christianity and the West. In Islamic Interpretations of Christianity. Edited by L. Ridgeon. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, pp. 179–204. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/1675922/islamic-interpretations-of-christianity-pdf (accessed on 2 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hadden, J.S. Addressing a Sibling Rivalry: In Seeking Effective Christian–Muslim Relations, to What Extent Can Comparative Theology Contribute? An Evangelical Christian Perspective. Religions 2025, 16, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030297

Hadden JS. Addressing a Sibling Rivalry: In Seeking Effective Christian–Muslim Relations, to What Extent Can Comparative Theology Contribute? An Evangelical Christian Perspective. Religions. 2025; 16(3):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030297

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadden, Joy S. 2025. "Addressing a Sibling Rivalry: In Seeking Effective Christian–Muslim Relations, to What Extent Can Comparative Theology Contribute? An Evangelical Christian Perspective" Religions 16, no. 3: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030297

APA StyleHadden, J. S. (2025). Addressing a Sibling Rivalry: In Seeking Effective Christian–Muslim Relations, to What Extent Can Comparative Theology Contribute? An Evangelical Christian Perspective. Religions, 16(3), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16030297