Qualitative Testing of Questionnaires on Existential, Spiritual, and Religious Constructs: Epistemological Reflections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Two Approaches to Qualitatively Testing a Questionnaire

2.1. The Cognitive Interview

2.2. The Semi-Structured Interview

3. Epistemological Differences and Similarities Between Cognitive and Semi-Structured Interviews

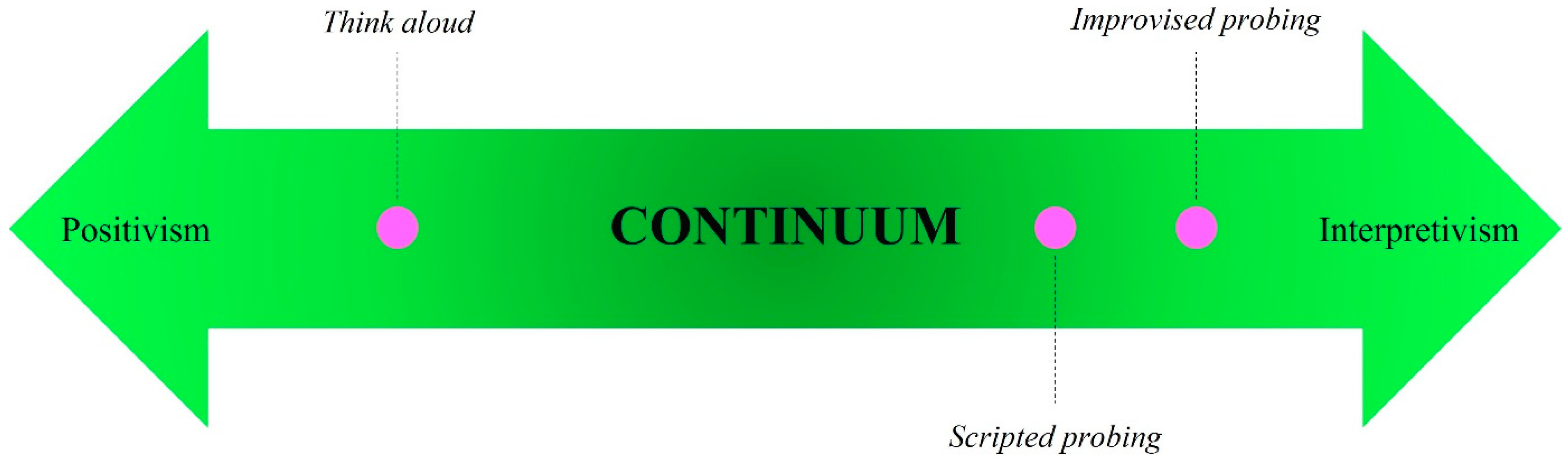

Probing over Think Aloud?

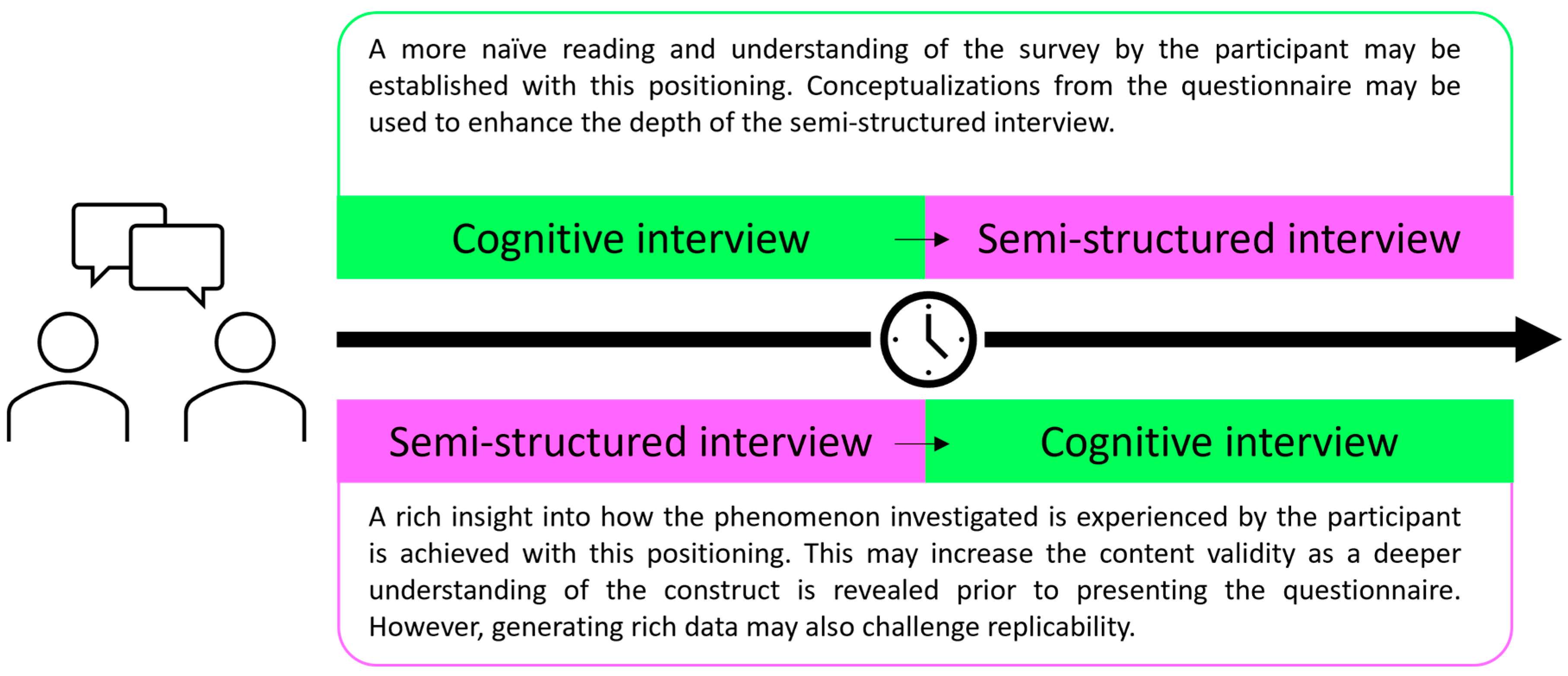

4. Epistemological Approaches in Combination

4.1. Cognitive Interview Before Semi-Structured Interview

4.2. Semi-Structured Interview Before Cognitive Interview

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beatty, Paul, and Gordon Willis. 2007. Research synthesis: The practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opinion Quarterly 71: 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, Sebastian Boesgaard, Tobias Anker Stripp, Ricko Damberg Nissen, Johan Albert Wallin, Niels Christian Hvidt, and Dorte Toudal Viftrup. 2025. Measuring spiritual, religious, and existential constructs in children: A systematic review of instruments and measurement properties. Archive for the Psychology of Religion. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Hans-Joachim Balzat, and Peter Heusser. 2010. Spiritual needs of patients with chronic pain diseases and cancer-validation of the spiritual needs questionnaire. European Journal of Medical Research 15: 266. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3351996/pdf/2047-783X-15-6-266.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannell, Charles F., Kent H. Marquis, and André Laurent. 1977. A summary of studies of interviewing methodology. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 2, Data Evaluation and Methods Research 69: 1–78. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, Jeremy D. W. 2020. Managing validity versus reliability trade-offs in scale-building decisions. Psychological Methods 25: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, Debbie. 2015. Cognitive Interviewing Practice. New York: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damberg Nissen, Ricko, Erik Falkø, Dorte Toudal Viftrup, Elisabeth Assing Hvidt, Jens Søndergaard, Arndt Büssing, Johan Albert Wallin, and Niels Christian Hvidt. 2020. The catalogue of spiritual care instruments: A scoping review. Religions 11: 252. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/11/5/252 (accessed on 3 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Damberg Nissen, Ricko, Erik Falkø, Tobias Kvist Stripp, and Niels Christian Hvidt. 2021. Spiritual needs assessment in post-secular contexts: An integrative review of questionnaires. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 12898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davie, Grace. 1994. Religion in Britain Since 1945, 1st ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace, Paul Heelas, and Linda Woodhead, eds. 2003. Predicting Religion: Christian, Secular and Alternative Futures, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vet, Henrica C. W., Caroline B. Terwee, Lidwine B. Mokkink, and Dirk L. Knol. 2011. Measurement in Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCicco-Bloom, Barbara, and Benjamin F. Crabtree. 2006. The qualitative research interview [Article]. Medical Education 40: 314–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervieu-Léger, Danièle, and Simon Lee. 2000. Religion as a Chain of Memory. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hvidt, Niels Christian, Elisabeth Assing Hvidt, and Peter la Cour. 2021. Meanings of “the existential” in a secular country: A survey study. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 3276–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabine, Thomas B., Miron L. Straf, Judith M. Tanur, and Roger Tourangeau, eds. 1984. Cognitive Aspects of Survey Methodology: Building a Bridge Between Disciplines, Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Robert Burke, and Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie. 2004. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher 33: 14–26. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3700093 (accessed on 3 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold George. 2008. Concerns about measuring ”spirituality” in research. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders 196: 349–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, Harold G., and Arndt Büssing. 2010. The duke university religion index (durel): A five-item measure for use in epidemological studies. Religions 1: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold George, Dana E. King, and Verna Benner Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, Steinar, and Svend Brinkmann. 2009. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Kerry, Gordon Willis, Barbara Forsyth, Alicia Norberg, Martha Stapleton, Debra Stark, and Frances Thompson. 2009. Using cognitive interviews to evaluate a spanish-language translation of a dietary questionnaire. Survey Research Methods 3: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Tony, and Martin Johnson. 2000. Rigour, reliability and validity in qualitative research. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing 4: 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mes, Marissa Ayano, Amy Hai Yan Chan, Vari Wileman, Caroline Brigitte Katzer, Melissa Goodbourn, Steven Towndrow, Stephanie Jane Caroline Taylor, and Rob Horne. 2019. Patient involvement in questionnaire design: Tackling response error and burden. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 12: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, Lidwine B, Henrica C. W. de Vet, Caroline A. C. Prinsen, Donald L. Patrick, Jordi Alonso, Lex M. Bouter, and Caroline B. Terwee. 2018. Cosmin risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Quality of Life Research 27: 1171–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, Caroline A. C., Lidwine B. Mokkink, Lex M. Bouter, Jordi Alonso, Donald L. Patrick, Henrica C. W. de Vet, and Caroline B. Terwee. 2018. Cosmin guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Quality of Life Research 27: 1147–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchalski, Christina M., Robert J. Vitillo, Sharon K. Hull, and Nancy Reller. 2014. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine 17: 642–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, Herbert J., and Irene S. Rubin. 2011. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sale, Joanna E., Lynne H. Lohfeld, and Kevin Brazil. 2002. Revisiting the quantitative-qualitative debate: Implications for mixed-methods research. Quality and Quantity 36: 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuman, Howard. 1966. The random probe: A technique for evaluating the validity of closed questions. American Sociological Review 31: 218–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, Kirsten, Omar Ummer, and Annette E. LeFevre. 2021. The devil is in the detail: Reflections on the value and application of cognitive interviewing to strengthen quantitative surveys in global health. Health Policy Plan 36: 982–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, Clive, David Silverman, Jaber F. Gubrium, and Giampietro Gobo. 2003. Qualitative Research Practice. London: Sage, pp. 1–640. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, Michael F., Patricia Frazier, Shigehiro Oishi, and Matthew Kaler. 2006. The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53: 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strack, Fritz, and Leonard L. Martin. 1987. Thinking, judging, and communicating: A process account of context effects in attitude surveys. In Social Information Processing and Survey Methodology. Edited by Hans-J. Hippler, Norbert Schwarz and Seymour Sudman. New York: Springer, pp. 123–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stripp, Tobias Anker, Dorte Toudal Viftrup, Ricko Damberg Nissen, Sonja Wehberg, Jens Sondergaard, and Niels Christian Hvidt. 2023a. Testing the acceptability and comprehensibility of a questionnaire on existential and spiritual constructs in a secular culture through cognitive interviews. Survey Research Methods 17: 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stripp, Tobias Anker, Sonja Wehberg, Ardnt Büssing, Harold Koenig, Tracy A. Balboni, Tyler J. VanderWeele, Jens Søndergaard, and Niels Christian Hvidt. 2023b. Spiritual needs in denmark: A population-based cross-sectional survey linked to danish national registers. The Lancet Regional Health-Europe 28: 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stripp, Tobias Kvist, Arndt Büssing, Sonja Wehberg, Helene Støttrup Andersen, Alex Kappel Kørup, Heidi Frølund Pedersen, Jens Søndergaard, and Niels Christian Hvidt. 2022a. Measuring spiritual needs in a secular society: Validation and clinimetric properties of the danish 20-item spiritual needs questionnaire. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 3542–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stripp, Tobias Kvist, Sonja Wehberg, Ardnt Büssing, Karen Andersen-Ranberg, Lars Henrik Jensen, Find Lund Henriksen, Christian Borberg Laursen, Jens Søndergaard, and Niels Christian Hvidt. 2022b. Protocol for exicode: The existential health cohort denmark—A register and survey study of adult danes. BMJ Open 12: e058257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, Caroline B., Cecilia A. C. Prinsen, Alessandro Chiarotto, Marjan J. Westerman, Donald L. Patrick, Jordi Alonso, Lex M. Bouter, Henrica C. W. de Vet, and Lidwine B. Mokkink. 2018. Cosmin methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A delphi study. Quality of Life 27: 1159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, Gordon B. 2005. Cognitive Interviewing. London: Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Gordon B., and Anthony R. Artino, Jr. 2013. What do our respondents think we’re asking? Using cognitive interviewing to improve medical education surveys. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 5: 353–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Think Aloud Example | Probing Examples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant reading and thinking aloud in relation to a question concerning belief in a guardian angel. Answer categories: Yes, No, Don’t know | Real time | Retrospective | |

| Participant reading out aloud: “Do you believe in a guardian angel?” Participant thinking aloud: “Well, especially when I was a kid, I liked to think that somebody was watching over me. Now I … ehm… I don’t really know. I am not sure if I really believe in that, but I can still get a feeling sometimes that somebody is looking after me or is with me, you know. So, I guess that means “Yes”.” | Scripted probe | What did the question [specific wording] make you think of? | Do you feel that there are certain spiritual beliefs, which you have had, or have, that were not covered by the questionnaire? |

| Improvised probe | That question seemed particularly difficult for you to answer. Could you elaborate on that? | I wonder if there were any words or questions in any of the items that you found it difficult to identify with? | |

| (post) Positivism | Interpretivism/Constructivism |

|---|---|

| Objectivity—belief in an unbiased truth | Subjectivity—the belief that people construct reality through social and cultural processes |

| Knowledge reflects a reality which already exists to be collected | Knowledge is a product of co-interpretation and co-construction, e.g., through language |

| Hypothetical deductive inquiry—belief in the scientific method through which data can be replicated | Inductive/interpretive approaches rely on naturalistic methods, e.g., entering real-world settings to observe, interact, and understand |

| Reliability is established by repeating identical measurements (replicability) | Knowledge is co-created and never considered replicable. Reliability is established by transparency in approach and subjectivity |

| ‘Detached’, neutral, and unbiased scientist—biases need to be controlled | Involved researcher biases need to be understood and are inseparable from the inquiry and outcomes |

| The predominant use of quantitative methods in which units are counted, weighed, and analysed with statistical methods | The predominant use of qualitative methods in which observations and interviews are conducted and analysed through hermeneutic analyses |

| Seeks to explain phenomena | Seeks to understand phenomena |

| Main Findings |

|---|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stripp, T.A. Qualitative Testing of Questionnaires on Existential, Spiritual, and Religious Constructs: Epistemological Reflections. Religions 2025, 16, 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16020216

Stripp TA. Qualitative Testing of Questionnaires on Existential, Spiritual, and Religious Constructs: Epistemological Reflections. Religions. 2025; 16(2):216. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16020216

Chicago/Turabian StyleStripp, Tobias Anker. 2025. "Qualitative Testing of Questionnaires on Existential, Spiritual, and Religious Constructs: Epistemological Reflections" Religions 16, no. 2: 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16020216

APA StyleStripp, T. A. (2025). Qualitative Testing of Questionnaires on Existential, Spiritual, and Religious Constructs: Epistemological Reflections. Religions, 16(2), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16020216