The Dual Ethical Dimensions of “Tian” in Xizi-Belief: Unveiling Tianming and Tianli Through a Hunan Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Religious Philosophy of “Tian”

1.2. Brief Review of Published Literature and Research Gaps on Xizi-Belief

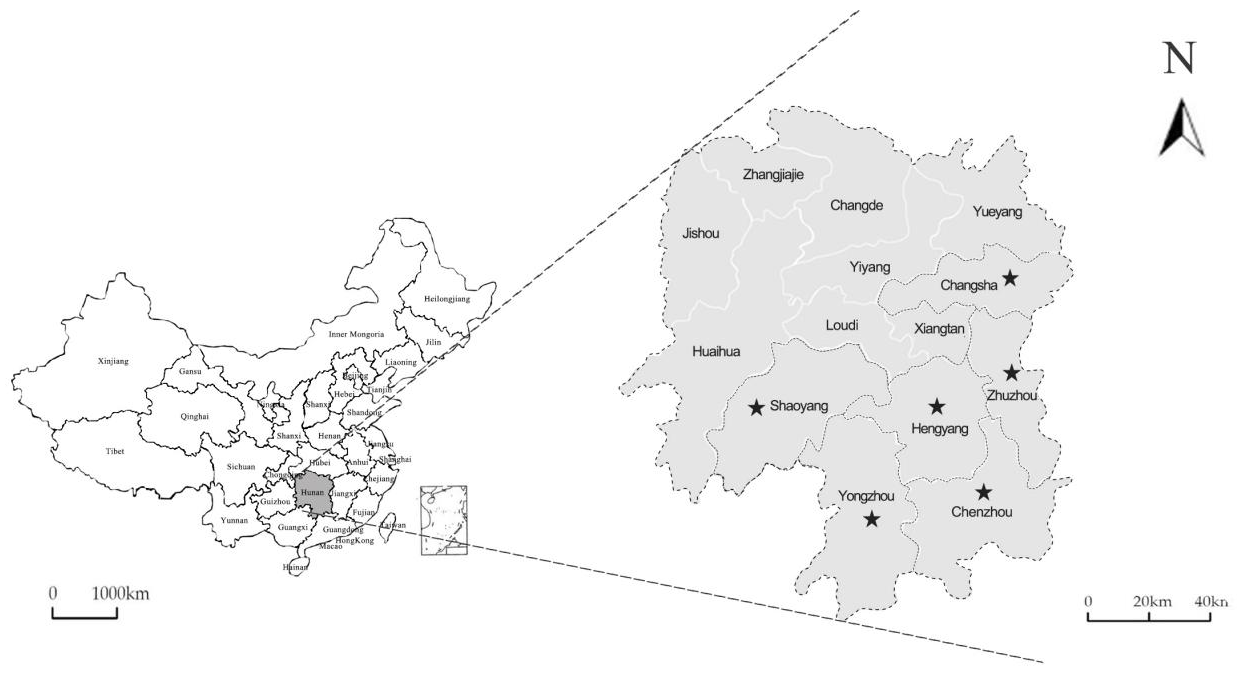

1.3. Research Materials and Methods

2. Tian Worship and Religious Philosophical Manifestation in Xizi-Belief

2.1. The Religious Philosophical Origin of “Tian” in Xizi-Belief

“仓颉始视鸟迹之文造书契则诈伪萌生,诈伪萌生则去本趋末,弃耕作之业而务锥刀之利,天知其将饿,故为雨粟;鬼恐为书文所劾,故夜哭也。‘鬼’或作‘兔’。兔恐见取豪 (毫) 作笔,害及其躯,故夜哭。”

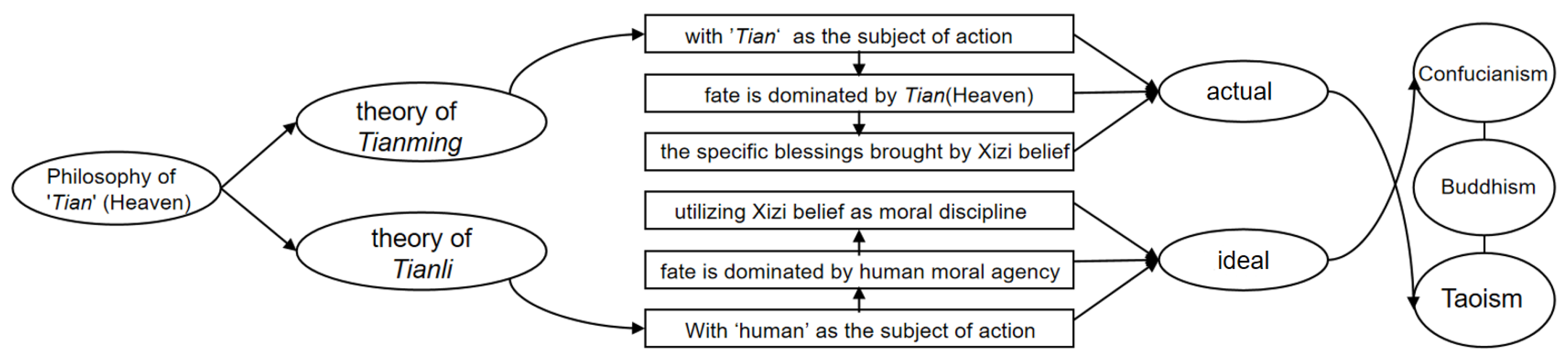

2.2. The Ethical Connotations of “Tian” in the Xizi-Belief Model

2.3. Philosophical Ontological Distinction Between Tianli Theory and Tianming Theory in Xizi-Belief

3. The Comparison Between the Theory of Tianming and the Theory of Tianli in Xizi-Belief

3.1. Important Embodiment of Tianming’s Theory in Xizi-Belief

| Region | Location | Taoist Mythological Illustrations | Origins of Mythological Legends |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xintian County, Yongzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Juwan Village | Wenchang Dijun, Kui Xing Bestowing Success (魁星点斗)15 | Divine Mythology |

| Xizi Pagoda in Zhoujia Village | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Hidden Eight Immortals | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Tangjia Village | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood, Hidden Eight Immortals | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Pengzicheng Village | Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood, Hidden Eight Immortals | Immortal Mythology | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Dongxin Village | Door Gods of Fortune and Prosperity (福禄门神)16 | Divine Mythology | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Fengzixi Village | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Hidden Eight Immortals, Consecutive Triumphs, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology | |

| Ningyuan County, Yongzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Xiwan Village | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Hidden Eight Immortals, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood, Consecutive Triumphs | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology |

| Xizi Pagoda in Tangtouling Village | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Door Gods of Fortune and Prosperity, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Laobaijia Village | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood, Consecutive Triumphs, Hidden Eight Immortals | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology | |

| Jiangyong County, Yongzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Daxu Town | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology |

| Chengbu Miao Autonomous County, Shaoyang | Xizi Pagoda in Yijiatian Village | Heavenly Official’s Blessing (天官赐福)17, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood, Three Stars of Fortune, Prosperity, and Longevity (福禄寿三星)18, Hidden Eight Immortals, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology |

| Longhui County, Shaoyang | Xizi Pagoda in Hebian Village | Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood | Immortal Mythology |

| Dawei Mountain Town, Liuyang | Xizi Pagoda in Chudong Village | Door Gods of Fortune and Prosperity, Hidden Eight Immortals | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology |

| Hengnan County, Hengyang | Xizi Pagoda in Jingchong Village | Heavenly Official’s Blessing, Kui Xing Bestowing Success | Divine Mythology |

| Xizi Pagoda in Zhanhe Village | Heavenly Official’s Blessing, Door Gods of Fortune and Prosperity | Divine Mythology | |

| Guiyang County, Chengzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Xincun Village | Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood, Hidden Eight Immortals | Immortal Mythology |

| Xizi Pagoda in Maofu Village | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Door Gods of Fortune and Prosperity | Divine Mythology | |

| Xizi Pagoda in Zhongliu Village | Door Gods of Fortune and Prosperity, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood | Divine Mythology, Immortal Mythology | |

| Linwu County, Chengzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Shijia Village | Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Door Gods of Fortune and Prosperity | Divine Mythology |

| Changsha County, Changsha | Xizi Pagoda in Juanshi Village | Hidden Eight Immortals, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood | Immortal Mythology |

3.2. Important Embodiment of Tianli’s Theory in Xizi-Belief

3.3. The Differences Between the Concepts of Tianming and Tianli in Xizi-Belief

3.4. Common Points Between the Concept of “Tianming” and “Tianli” in Xizi-Belief

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion: Three Models of the Influence of Tianli and Tianming on Xizi-Belief

4.2. Conclusion: The Positive Role and Value Regeneration of Xizi-Belief’s Religious Philosophy from a Modern Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Feng Youlan divided “Tian” into five different meanings: the heaven of matter, the heaven of domination, the heaven of destiny, the heaven of nature, and the heaven of righteousness. The philosophy of “Tian” is rooted in the cultural soil of the Chinese nation, influencing social lifestyles and individual thinking patterns. For details, see Feng Youlan’s History of Chinese Philosophy (I). |

| 2 | The concept of “Tianli” here refers to “heavenly principles”, which are unchanging moral laws in the universe and are realized through human virtues. |

| 3 | Tian determines blessings and misfortunes based on a person’s good and evil deeds. |

| 4 | The fate and consequences of an individual are determined by the will of Tian. |

| 5 | The core of Taoist philosophy is “effortless action (无为)”, which advocates an attitude in life of conforming to nature and governing by inaction, pursuing harmonious coexistence between individuals and the universe (Gao 2024, Issue 13). |

| 6 | The concept of “the Tianming is called nature (天命之谓性)” comes from the book Liji’·Zhongyong (礼记·中庸), which states that the “heavenly mandate is called nature, free will is called Tao, and cultivating Tao is called teaching”. This means that following human nature endowed by the heavenly mandate is to follow the heavenly mandate, and following the heavenly mandate and improving moral cultivation is to achieve education; derived from Zou (2020, p. 40). |

| 7 | Kuixing (魁星): the god in charge of good or bad articles in Taoist mythology is the great lucky star that dominates the cultural movement in the world, corresponding to the first Tianshu star or the general name of the first four stars in the constellation of the Dipper. |

| 8 | Divine Mythology (神灵神话) tells the stories of the primordial True Saints, including natural deities, the gods within the human body, and figures such as San Qing Si Yu (三清四御) in Taoism. It embodies the idea that all things possess a spirit, reflecting a worldview in which everything in the universe is animated by spiritual essence (Tan 2009). |

| 9 | Taoist mythology (道教神话) is primarily divided into three major categories: Taoist Fairyland Mythology, Divine Mythology, and Immortal Mythology. |

| 10 | San Yuan Da Di (三元大帝) refers to the three gods in charge of the three realms of heaven, Earth, and water in Taoism. They are also known as the three great emperors, including heaven, Earth, and water officials, who are responsible for blessing, forgiveness, and reconciliation. |

| 11 | The Eight Immortals (暗八仙): The Eight Immortals finally become immortals through their own cultivation. Their magic weapons contain magical power and meaning. For example, the gourd of Li Tieguai symbolizes fortune and exorcism, while Lv Dongbin’s sword symbolizes killing demons and protecting all living creatures. The dark Eight Immortals refer to the patterns of magic instruments held by the Eight Immortals. This is a common auspicious sculpture in China. Because the magic instruments refer to immortals, they are called the dark Eight Immortals. |

| 12 | Consecutive Triumphs (一路连科) is a phrase that originated in the imperial examination era of China. It is a blessing for those preparing for or participating in the imperial exams, symbolizing continuous success and victory. The phrase is derived from wordplay involving homophones: “鹭” (heron) sounds similar to “路” (road), and “莲” (lotus) sounds like “连” (continuous). Thus, “一路连科” carries the wish for candidates to succeed in a series of exams, one after another, achieving unbroken success. |

| 13 | The Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood (鲤鱼跃龙门) is a legend that states that if a carp can leap over the Dragon Gate, it will transform into a true dragon. This is used as a metaphor for the spirit of hard work, determination, and ambition. After the implementation of the imperial examination system, the phrase “Carp’s Leap over the Dragon Gate” was used to symbolize success in the imperial exams. |

| 14 | Immortal Mythology (神仙神话) refers to stories of mortals who attain immortality through cultivation. In these narratives, the protagonists are typically ordinary humans who, through continuous cultivation and enlightenment, gradually transcend the human condition of emotions, desires, and the cycle of birth, aging, sickness, and death. As a result, they acquire miraculous abilities, such as the power of flight and transformation (Tan 2009). |

| 15 | Kuixing Dian Dou (魁星点斗) refers to an ancient legend where the deity Kuixing uses a brush to point out the names of successful candidates in the imperial examination, symbolizing being the top scorer and achieving the title of “Zhuangyuan” (the highest honor in the imperial exam). |

| 16 | The Door Gods of Fortune and Prosperity (福禄门神) are deities in Chinese folk belief that protect the household. They are typically affixed to doors during the Chinese New Year to ward off evil spirits and bring good luck and prosperity. “Fu” (福) represents happiness and good fortune, while “Lu” (禄) symbolizes wealth and status. |

| 17 | The Heavenly Official (天官) is one of the gods in Chinese mythology, responsible for blessing the world. This phrase means that the Heavenly Official bestows blessings and good luck on people and usually prays for the Heavenly Official’s blessing in the new year or on special occasions. |

| 18 | The Three Stars of Fortune, Prosperity, and Longevity (福禄寿三星) are three auspicious gods in Chinese folk beliefs, representing happiness (Fortune), wealth (Prosperity) and longevity (Longevity). Their images often appear in traditional decoration, symbolizing people’s yearning for a better life. |

| 19 | The image is from a website: netease subscription, [have art realm—have art thought] “Ancient college entrance exams, worshiping the right god is very important”. |

| 20 | The image is from the official microblogging site of the Palace Museum. |

| 21 | The image is from intu.com: Fortune and Longevity Three-Star picture, traditional culture, and art design gallery. |

| 22 | Quàn Shàn Shū (劝善书): this is a type of letter or essay that encourages people to do good deeds, cultivate personal morality, and pursue virtuous behavior and good conduct. |

| 23 | The word “阴骘” originally came from the ancient book Shangshu Hongfan《尚书·洪范》. It refers to the rewards and punishments that heaven does not announce but uses to secretly supervise people’s good and evil behaviors. The scholars Daisaku Suzuki and Paul Carus chose “YinChihWen” as the English translation of “阴鸷文”. It not only retains the cultural connotation of the original text but also tries to be concise for overseas readers to understand; from https://www.amazon.com/Yin-Chih-Wen-Extracts-Commentary/dp/1013766555 (accessed on 29 December 2024). |

| 24 | The complete process of the sacrificial ceremony in the Kamalan Hall (now Yilan) region of Taiwan is clearly documented: “The discarded characters are collected together, then washed with Fragrant Water. Next, the water is filtered through a sieve to prevent any characters from being missed or falling out. After sun-drying, the characters are placed in a tower for storage, and once a certain amount is accumulated, they are burned. After the incineration, the ashes left in the tower are scooped out with a wooden spoon and placed into a jar, or sometimes into a wooden box. The ashes are then transported by boat to the sea or the center of a river, where the ritual of ‘sending paper ash into the sea’ is performed, waiting for the ashes to slowly submerge. The entire ceremony is conducted with great solemnity and sanctity, requiring scholars to be properly dressed, accompanied by the sound of drums and wind instruments along the way, until the sacred trail disappears from sight, marking the completion of the ritual” (Shu and Yang 2023). |

| 25 | Water Spraying for Exorcism (喷水驱邪), also known as 噀水 (Chuan Shui), is a Taoist exorcism ritual that uses water to drive away evil forces or inauspicious energies. The act of spraying water is believed to cleanse the environment and protect individuals or spaces from negative influences. |

| 26 | Water Official dispelling calamities (水官解厄): The Water Official is one of the three revered deities in Taoism (along with the Heavenly Official and Earthly Official). In Taoist belief, the Water Official Emperor descends to the human world on the 15th day of the 10th lunar month, specifically to relieve the calamities and hardships of virtuous people, dispelling disasters and alleviating difficulties. |

| 27 | The Qinghe Nei Zhuan (清河内传) is a Taoist text from the Ming Dynasty, attributed to the legendary Emperor Wen Chang, who is said to have narrated his own life story. The work blends historical events with mythology, advocating for virtues such as loyalty, filial piety, integrity, and the transmission of ancestral moral values through virtuous deeds. |

| 28 | The Record of Merits and Responses from Cherishing Characters (惜字感应录) is a book that compiles numerous rules, admonitions, and case studies related to the practice of cherishing characters, with the aim of encouraging people to respect culture and treasure words. |

| 29 | Offering a Memorial Prayer (进表): Taoism believes that by Offering a Memorial Prayer, the writing in the prayers of believers can be sent to the heaven, and saints can come to the altar to worship, bless, and prolong age and receive the blessings of ancestors. |

| 30 | Gui (圭) is ancient Chinese ritual ware, which refers to flake jade ware with a sharp upper part and a straight lower end. The gui shape adopts the shape of this ritual vessel, which is a unique shape in ancient Chinese architecture. |

| 31 | Jiao Jie Xin Xue Bi Qiu Xing Hu Lv Yi (教诫新学比丘行护律仪) is a book written by the Tang Dynasty monk Daoxuan. It specifically records norms and guidance for the behavior, daily life, and rituals of bhikkhus (Buddhist monks) in training. |

| 32 | Zengguang Wen Chao Vol. 2, Wan Hui Jie Yun Hu Guo Jiu Min Zheng Ben Qing Yuan Lun. |

| 33 | Niu Dou (牛斗) are tools used in ancient sacrificial rites shaped like ox horns. |

| 34 | Dian Xue (点雪) symbolizes the reverence of the ancients for words. It is as pure and flawless as a snowflake and needs to be carefully protected and cherished. At the same time, it implies that knowledge is precious and short-lived. Like snowflakes, it is beautiful but perishable and needs to be cherished and inherited in time. |

| 35 | Rong Jing (镕经) refers to the fusion and refinement of classical literature or knowledge to form a new understanding or system. |

| 36 | Wen Kui (文魁) refers to Wenxing (文星) and Kuixing (魁星). It is also used to refer to an outstanding person in the field of literature to express praise and admiration for literary talent or excellent results in the imperial examination. |

| 37 | The architectural design of Xizi Pagodas typically features odd-numbered layers, such as one, three, or five levels. |

| 38 | The architectural floor plan of Xizi Pagodas typically features even-numbered geometric shapes, such as quadrilaterals, hexagons, or octagons. |

| 39 | The Chinese mythological story describes the Eight Immortals of Taoism, each using their own magical treasures to communicate with gods across the sea. Later, this story was also used as a metaphor for individuals who excel in their own unique ways, each demonstrating their special abilities. |

References

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2017. Liquid Modernity 流动的现代性. Translated by Ouyang Jinggen 欧阳景根. Beijing: China Renmin University Press, p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Fang 陈芳, and Xiaodong Liu 刘晓冬. 2014. A Brief Discussion on the Character Library Pagoda: Starting from the Qing Dynasty Character Library Pagoda in the Collection of Chengdu Wuhou Temple Museum 字库塔小议——从成都武侯祠博物馆馆藏清代字库塔说起. Chinese Culture Forum 8: 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Guy. 1994. Discourse and literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Shengyuan. 2021. Study on the Concept of Sacredness of Pre-Qin Writing 先秦“书写”神圣性观念研究. Social Science Front 3: 176–84. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Jiafu 杜家福. 1906. Xizi Zhengzong 惜字正宗, Reprinted in the 32nd year of the Guangxu era.

- Editorial Department of Literature, History and Philosophy 文史哲编辑部. 2011. Confucianism: History, Thoughts and beliefs 儒学:历史、思想与信仰. Beijing: Commercial Press, p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Liming 高黎明. 2024. Research on the Thought of Destiny in Confucian Philosophy 儒家哲学中的天命思想研究. Philosophical Progress 13: 2449–53. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books, p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Zaiyi 郭在贻, Puquan Zhang 张浦泉, and Zheng Huang 黄征. 1990. Dunhuang Bianwen Ji Jiao Yi 敦煌变文集校议. Changsha: Yuelu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1999. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Translated by Weidong Cao, Xiaojue Wang, Beicheng Liu, and Weijie Song. Shanghai: Xuelin Press, pp. 40–42, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, Hui 海慧. 2009. An Exploration of Monk Xuyun’s Thought on the Pure Land on Earth 虚云和尚人间净土思想探微. Fa Yin 11: 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- He, Ning 何宁. 1998. Huainanzi Jishi 淮南子集释. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, p. 571. [Google Scholar]

- He, Yiwen, He Lai, Zhou Qixuan, and Xubin Xie. 2024. Study on the Religious and Philosophical Thoughts of Xizi Pagodas in Hunan Province of China. Religions 15: 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Yiwen, Xuemin Zhang, Xinlei Chen, Dong Fu, Bei Zhang, and Xubin Xie. 2023. Study on the Protection of the Spatial Structure and Artistic Value of the Architectural Heritage Xizi Pagoda in Hunan Province of China. Sustainability 15: 8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Sheng 姜生. 2023. The Study of Emperor Shi of Han: The Origin of Emperor’s Power and Celestial Teacher’s Teaching Power 汉始皇帝考——天子君权与天师教权之源. Wen Zhe 3: 57–95. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Na 李娜. 2011. A Study on the Folk Belief in Cherishing Characters in the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China 清代、民国民间惜字信仰研究. Master’s thesis, Huazhong Normal University, Wuhan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Shan 梁珊. 2015. On the Present Significance of Cheng-Zhu Theory 论程朱理学的现世意义. Times Report 3: 263. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Yuhui 罗用会. 2024. Zunyi Area Zikuta Survey and Research遵义地区字库塔调查研究. Master’s thesis, Guizhou University of Nationalities, Guiyang, China. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Yongjie 彭永捷. 2018. A Brief Introduction to the Political Philosophy of Confucianism’s Heavenly Way: A Discussion on the Scientificity of Confucianism 儒家天道政治哲学发微——兼论儒学的科学性. Exploration and Controversy 5: 117–22+144. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Qingju 乔清举. 2011. On the Chronological View of the Heavenly Way in Confucian Natural Philosophy and Its Ecological Significance: Centered on the Book of Changes 论儒家自然哲学的天道时序观及其生态意义——以《易传》为中心. Zhouyi Research 周易研究 5: 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Yongzhou 秦永洲. 2008. History of Chinese Social Customs 中国社会风俗史. Jinan: Shandong People’s Publishing House, p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, Liangzhi 桑良至. 1996. The worship of information in ancient China: Cherishing the calligraphy forest, picking up calligraphy monks, and Dunhuang grottoes 中国古代的信息崇拜——惜字林、拾字僧与敦煌石窟. Journal of Peking University 3: 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Ying, and Luo Yang. 2023. Word Stock Tower in Chongqing’s Countryside: The Guardianship of Ploughing and Reading Culture 巴渝乡村字库塔:耕读文化的守望. City Geography 城市地理 11: 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Georg. 2003. The Stranger and Other Essays. In Modern Man and Religion 现代人与宗教. Translated by Wei Dong Cao 曹卫东. Beijing: China Renmin University Press, pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Lian 宋濂. 2014. The Complete Works of Song Lian 宋濂全集. Beijing: People’s Literature Publishing House, p. 633. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Rong Lei 孙荣耒. 2006. The custom of honoring characters paper and its cultural significance 敬惜字纸的习俗及其文化意义. Folklore Research 2: 166–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Dandan 檀丹丹, Huifang Liu 刘辉芳, and Lin Liu 刘琳. 2021. Analysis of the Architectural Culture of Xizi Pagoda in Hunan Province under Local Environment and Architectural Form 风土环境与建筑形态下湖南省惜字塔建筑文化分析. Urban Architecture 18: 171–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Min. 2009. Historical and Cultural Characteristics of Taoist Mythology 道教神话的历史文化特征. Journal of Southwest University for Nationalities 西南民族大学学报 (人文社科版) 30: 184–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Wei 田薇. 2011. Simmel’s View of Religion Centered on ‘Religiosity’ 西美尔以“宗教性”为轴心的宗教观. Journal of Renmin University of China 5: 143–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Thi Phuong, Tan Hoang Phan, and Nhu Vo Tam Nguyen. 2024. Cultural schemas and folk-belief: An insight into the belief in worshiping the Mother Goddess in Vietnam. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Kevin J. 2023. Rethinking the Mengzi’s Concept of Tian 天. Religions 14: 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Victor. 2006. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Translated by Jianbo Huang 黄剑波, and Boyun Liu 柳博赟. Beijing: China Renmin University Press, p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guoliang 王国良, and Xia Wang 王霞. 2012. On Zhu Xi’s View of Tianren (Heaven and Man) and Its Practice 论朱熹的天人观及其实践. Social Science Front 4: 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Liqi 王利器. 1993. Yanshi Jiaxun Ji Jie 颜氏家训集解. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Mingming 王铭铭. 2010. The Magic of Writing: An Anthropology of Writing 文字的魔力: 关于书写的人类学. Sociological Studies 社会学研究 25: 44–66+244. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Hong 魏红. 2004. Research on the phenomenon of worship of ancient Chinese characters 中国古代文字崇拜现象研究. Master’s thesis, Qufu Normal University, Jining, China. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Zhongming 吴忠民. 2025. On the Great Generative Significance of Science and Technology for the Dynamics of Modernization On the Great Generative Significance of Science and Technology for the Dynamics of Modernization 论科学技术对现代化动力的巨大生成意义. Journal of Shandong University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Baisong 向柏松. 1999. Taoism and Water Worship 道教与水崇拜. Journal of the Central South College of Nationalities 1: 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Qingxiong 张庆熊. 2002. The Category of Christian Theology: A Comparative Study of History and Culture 基督教神学范畴——历史和文化比较的考察. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zehong 张泽洪. 2018. The Yellow Emperor in the Perspective of Taoist Beliefs 道教信仰视野中的黄帝. Journal of Sichuan University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition) 2: 104–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Fasheng 赵法生. 2015. The Transformation of Xunzi’s Theory of Heaven and the Pre Qin Confucian View of Heaven and Man 荀子天论与先秦儒家天人观的转折. Journal of Tsinghua University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 30: 97–106+189. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Guangming 赵广明. 2023. From “Jedi Sky Communication” to “Dao Cheng Sensation”: A Religious Philosophical Examination of the Relationship between Heaven and Man 从“绝地天通”到“道成感觉”——对天人关系的宗教哲学考察. World Religion Research 10: 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Peng 赵芃. 2013. The culture of talismans in Taoism 道教中的符箓文化. Chinese Religion 7: 54–55+92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Xiong 郑熊, and Fang Huang 黄芳. 2024. From “mandate of heaven” to “principle of heaven”—Han Yu, Er Cheng’s theory of heaven, and the development of Confucianism during the Tang and Song dynasties 从“天命”到“天理”——韩愈、二程天论与唐宋之际儒家的发展. Journal of Northwest University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 10: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shuja 周叔迦. 2004. Summary of Buddhist Literature and Arts 释家艺文提要. Beijing: Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Hanmin 朱汉民. 2023. ‘Heaven’: From Divine Worship to Philosophical Construction “天”: 从神灵崇拜到哲学建构. Social Sciences 5: 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Hong (明) 株宏. 2011. Complete Works of Master Lianchi: Volume II 莲池大师全集下. Edited by Jinggang Zhang 张景岗点校. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Xinming 邹新明. 2020. Respect for Heaven and Ethics 敬天与伦理. Beijing: Beijing United Publishing House, p. 47. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Region | Location | Construction Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yongzhou, Xintian County | Tao Lingjiao, Zhoujia Village Xizi Pagoda | In the 20th year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1841) |

| 2 | Sheep Town, Oujiawu Village Xizi Pagoda | In the twelfth year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1832) | |

| 3 | Jiantou Town, Juwan Village Xizi Pagoda | In the fourth year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1824) | |

| 4 | Jiantou Town, Tangjia Village Xizi Pagoda | In the eighth year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty (1882) | |

| 5 | Longquan Town, Mao Liping Village Xizi Pagoda | In the fourth year of the Qing Dynasty’s Tongzhi reign (1865) | |

| 6 | Jiantou Town, Pengzi City Village Xizi Pagoda | During the Xianfeng period of the Qing Dynasty | |

| 7 | Longquan Town, Meiwan Village Xizi Pagoda | During the Xianfeng period of the Qing Dynasty | |

| 8 | Xinwei Town, Hechang Village Xizi Pagoda | During the Xianfeng period of the Qing Dynasty | |

| 9 | Jiantou Town, Dongxin Village Xizi Pagoda | The Qing dynasty | |

| 10 | Jinpen Town, Fengzi Xi Village Xizi Pagoda | The Qing dynasty | |

| 11 | San Jing Town, Tangjia Village Xizi Pagoda | In the eighth year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty | |

| 12 | Xiuling Shui Village Xizi Pagoda | In the tenth year of the Tongzhi reign of the Qing Dynasty (1871) | |

| 13 | Changfu Village Xizi Pagoda | In the eighth year of the Tongzhi reign of the Qing Dynasty (1882) | |

| 14 | Yongzhou, Ningyuan County | Taiping Town, Tangtou Ling Village Xizi Pagoda | The Qing dynasty |

| 15 | Xiwan Village Xizi Pagoda | Qing Xianfeng Erjian (1852) | |

| 16 | He Ting Town, Lao Bai Jia Village Xizi Pagoda | During the Xianfeng reign, in the tenth year of the Xianfeng reign of the Qing Dynasty (1860) | |

| 17 | He Ting Town, Pipa Gang Village Xizi Pagoda | The Qing dynasty | |

| 18 | Yongzhou, Lengshuitan District | Xiao Jia Yuan Xizi Pagoda | The Qing dynasty |

| 19 | Yongzhou, Jianghua County | Daxi Town, Baojing Village Xizi Pagoda | The early Qing Dynasty |

| 20 | Shaoyang, Longhui County | Tantou Town, Santang Village Xizi Pagoda | In the 23rd year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1843) |

| 21 | Yankou Town, Riverside Village Xizi Pagoda | In the 29th year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1849) | |

| 22 | Shaoyang, Chengbu Miao Autonomous County | Dan Kou Town, Yi Jia Tian Xizi Pagoda | During the Daoguang period of the Qing Dynasty |

| 23 | Liuyang, Daweishan Town | Chudong Village Xizi Pagoda | During the reign of Emperor Guangxu, in the 33rd year of the Qing Dynasty (1907) |

| 24 | Hengyang, Hengnan County | Jing Chong Village Xizi Pagoda | In the second year of the Bingzi reign of Emperor Guangxu of the Qing Dynasty |

| 25 | Zhan He Village Xizi Pagoda | In the 12th year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty (1886) | |

| 26 | Chenzhou, Jiahe County | Chujiang Village Xizi Furnace | In the 19th year of the Jiaqing reign of the Qing Dynasty (1814) |

| 27 | Chenzhou, Guiyang County | Xin Cun Xizi Pagoda | During the Tongzhi period, in the third year of Tongzhi (1862) |

| 28 | Sha Li Mao Fu Village Xizi Pagoda | During the reign of Emperor Daoguang, in the third year of the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1850) | |

| 29 | Zhong Liu Village Xizi Pagoda | In the first year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty (1875) | |

| 30 | Shuangjiang Village Xizi Pagoda | In the first year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty (1875) | |

| 31 | Chenzhou, Linwu County | Shihuiyao Village Xizi Pagoda | In the 19th year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1839) |

| 32 | Shi Jia Village Xizi Pagoda | During the reign of Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty | |

| 33 | Changsha | Wangcheng District Shanmu Qiao Tower | In the 13th year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty (1887) |

| 34 | Jiufengshan Village Tea Pavilion Xizi Pagoda | In the 18th year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1838) | |

| 35 | Mashi Xizi Pagoda | In the 23rd year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1843) | |

| 36 | Changsha County, Juanshi Village Xizi Pagoda | In the ninth year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1830) | |

| 37 | Xinhua Village Xizi Pagoda | In the 23rd year of the Qing Dynasty’s Daoguang reign (1843) | |

| 38 | Zhiji Xizi Pagoda | In the 23rd year of the Guangxu reign of the Qing Dynasty (1897) |

| Design of Paper Entrance | ||||

|  |  |  | / | |

| voucher | gui-shaped30 | square-shaped | orbicular | / | |

| Characteristics of Ash Exit Design | |||||

|  |  |  |  | |

| copper coins | orbicular | square-shaped | animal heads | voucher | |

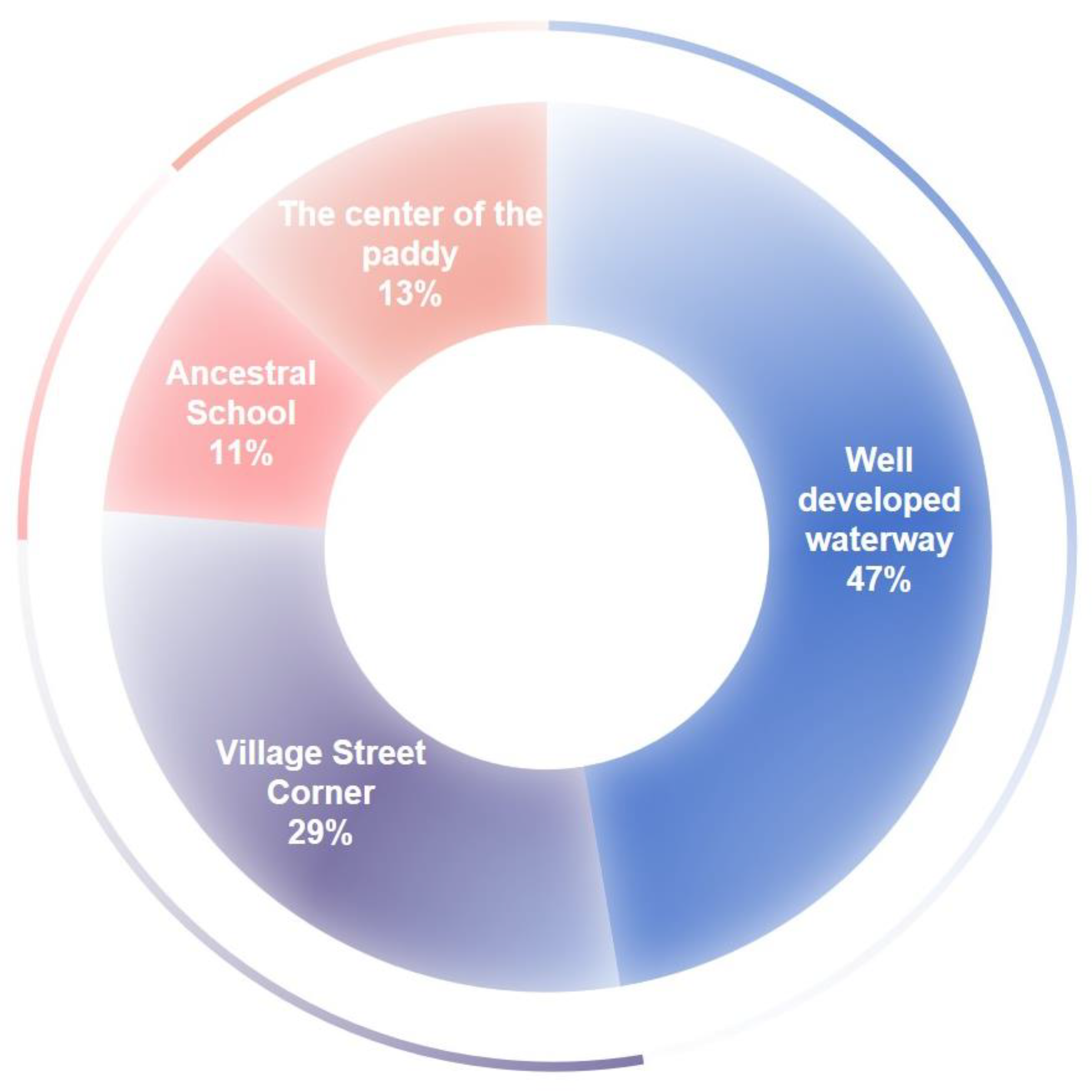

| Xizi Pagoda Locations | Number | ||||

| Well-developed water systems | 18 | ||||

| Village entrances | 11 | ||||

| Ancestral halls and schools | 4 | ||||

| In the center of rice fields | 5 | ||||

| Region | Xizi Pagoda | Plaques | Couplets | Connotation of Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longhui County, Shaoyang | Xizi Pagoda in Santang Village | Xizi Furnace | The Holy Emperor venerates Confucianism and upholds literature, honoring the relics of ancient sages and philosophers. This is by no means merely a transient embellishment, but a deeply meaningful and lasting respect. (圣天子崇儒右文至意,尊古先神哲遗迹,岂徒侈一时粉饰云尔哉) | Reverence for the Holy |

| Linwu County, Chenzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Shihuiyao Village | Xizi Furnace | The blazing furnace’s light shines like the stars, while the ashes, with the preserved characters, are as precious as gold. (火灿洪炉光射斗,灰珍遗字重如金) | Veneration of the Written Character |

| Xintian County, Yongzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Meiwan Village | Xizi Furnace | The cauldron burns the written papers, and the Niu Dou33 with the brilliance of the characters. (鼎炉焚字纸,牛斗灿文光) | Veneration of the Written Character |

| Guiyang County, Chenzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Maofu Village | Veneration of the Written Word | The form of the pagoda can house books, while its inner spirit is extraordinary and transcendent. (形能藏简册,气自绕云开) | Veneration of the Written Character |

| Longhui County, Shaoyang | Xizi Pagoda in Hebian Village | Xizi Pagoda | Treasure and carefully preserve the official records, collecting and gathering the scattered fragments. (珍重开司籍,搜罗小拾遗) | Veneration of the Written Character |

| Guiyang County, Chenzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Zhongliu Village | Dian Xue (点雪34) | The writing is refined by the dragon, and the ink and brush transform into clouds and smoke. (文章归蛟炼,笔墨化云烟) | Veneration of the Written Character |

| Chengbu Miao Autonomous County, Shaoyang | Xizi Pagoda in Yijiatian Village | Xizi Furnace | The value of culture and civilization should not be lost or disappear, while the principles and the tools or methods to achieve them will always remain (斯文宜未坠,道器自常存) | Exaltation of Literature |

| Xintian County, Ningyuan | Xizi Pagoda in Xiwan Village | Xizi Pagoda | The written words contain profound wisdom and philosophy, much like the mysterious forces of the universe and nature (Zao Hua Gong), capable of enlightening the human heart. (丹篆文明象,洪炉造化功) | Exaltation of Literature |

| Xintian County, Yongzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Maoliping Village | Rong Jing (镕经35) | Heaven and Earth are one great furnace, and all writings (or literary works) have reached a transcendent and extraordinary realm. (天地一洪炉,文章皆化境) | Exaltation of Literature |

| Hengnan County, Hengyang | Xizi Pagoda in Zhanhe Village | Wen Kui (文魁36) | The writing enters the realm of transformation, and the ink and brush leave behind a lasting fragrance. (文章入化,翰墨流香) | Exaltation of Literature |

| Xintian County, Ningyuan | Xizi Pagoda in Pipagang Village | Glorify | Aspiring to both external glory and status, as well as inner wisdom and talent. (文章光日月,笔墨化云烟) | Exaltation of Literature Pleasure in Learning |

| Xintian County, Yongzhou | Xizi Pagoda in Hechang Village | Full of Vigor 有元气 | Aspiring to both external glory and status, as well as inner wisdom and talent. (头品顶戴,满腹经纶) | Exaltation of Literature Pleasure in Learning |

| Cultural Schema | Influencing Models | Description | Theory of Tianming | Theory of Tianli | Examples of Belief | Cultural Representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Schema | The religious philosophy integration model | ① The ideological system of Xizi-belief. ② The construction of the worldview of Xizi-belief through Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist philosophies. | ① The expected specific blessings brought by the virtuous act of cherishing characters. ② Emphasizing the destiny and blessings carried by characters. | ① The moral order represented by characters. ② Binding the respect for paper to the observance of the Divine Principle and the preservation of moral order. | Confucianism: respect for knowledge Buddhism: cause and effect, karmic retribution Taoism: harmony between human affairs and destiny (Tianming) | Religious scriptures Doctrines and Educations Regulations on cherishing characters |

| Text Schema | The ritual practice model | ① Folkloric manifestations of Xizi-belief. ② Ritual behavior in the living world. | Faith Practice: praying for the protection of Tianming and seeking divine blessings through sacrificial rituals to fulfill one’s wishes. | Moral Practice: considering the ceremony of cherishing characters as an act of accumulating virtue and encouraging people to perform kind deeds, thereby regulating social order. | ① Ritual Text: Collecting Written Paper, Washing, Sifting, Sun-Drying, Incinerating, Clouds of Smoke Ascending to Heaven, Storing Ashes, Conveying Ashes to the Sea. ② Ritual Efficacy: strengthening reverence and respect for characters; enhancing the connection between humans and supernatural forces. | Xizi promotion Xizi organization Xizi Ceremony |

| Language Schema | The architectural embodiment model | ① The linguistic symbolic carrier of Xizi-belief. ② The symbolic patterns of architectural language. | Symbolic Metaphor: site selection, architectural form, and carving patterns. | Symbolic orientation: couplet texts and inscriptions on towers. | ① Visual language: Taoist mythological imagery; image function, which implies reverence for and compliance with Tianming. ② Written language: Couplets’ text: Reverence for the Holy, Veneration of the Written Character, Exaltation of Literature, Pleasure in Learning. The function of the text: reflecting ethical values and respect for knowledge. | Xizi architecture Xizi couplets Xizi decoration |

| Concept | Description | Embodiment of Tianming | Embodiment of Tianli |

| Religious Structure | Two Philosophical Models of Religious Structure | Religiositǎt Religious character of the inner nature | Religion Religious forms of outward manifestation |

| Origin | The Philosophical Foundation of Xizi-belief | Tian-derived ① Respect for the supernatural power of characters. ② Fate is determined by “Tian”. | Moral-derived ① Respect for the moral commandments represented by writing. ② Following the principle of cherishing characters to align with Tianli for self-cultivation and family harmony. |

| Believers | The Theoretical Divergence in the Worship of “Tian” | Taking “Tian” as the subject of action Fate is governed by supernatural deities. | Taking humans as the subject of action Fate is governed by the moral laws of the universe. |

| The Practice of Faith | The Manifestation of Faith in Daily Life | The sacred world: praying for divine protection through the cherishing of words and seeking to fulfill wishes such as success in the imperial examination. | The secular world: enhancing moral cultivation through the act of cherishing words, spreading cultural knowledge, and achieving social harmony. |

| Moral Education | The Influence of Faith on Moral Norms | Causal Domination Cherishing words brings good rewards, while desecrating words leads to punishment. | Ethical Domination The ethical morals in the practice of cherishing words cultivate a sense of reverence and responsibility in individuals. |

| Social Drama Stages | Description | Embodiment of Tianming | Embodiment of Tianli |

|---|---|---|---|

| Separation | Ceremony preparation | Prepare sacrificial items and written paper, perform purification rituals, etc., to show reverence for Tianming. | Emphasizing the purification of the heart. |

| Liminality/Margin | Processes and symbols of the Ceremony | ① By burning paper, the ashes rise to the heavens, allowing the heavens to perceive the prayer and fulfill the wish, thus establishing communication with the divine. ② Offering items symbolizing divine will, such as incense and sacrificial offerings. | ① Moral cultivation and enlightenment through ritual etiquette. ② Offerings symbolize reverence and respect for the divine. |

| Aggregation | Ceremonial results and transmission | ① Gaining the protection of Tianming through the Xizi Ceremony, fulfilling desires such as success in the imperial examination. ② Expressing the importance of cherishing words and respecting knowledge through family traditions and other means. | ① Emphasizing individual and societal moral improvement and achieving harmony with Tianli through Xizi actions. ② Passing on the concept of Tianli through education, cultural dissemination, and other means, promoting social progress. |

| Architectural Elements | Description | Embodiment of Tianming | Embodiment of Tianli |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural Site | Location Choice | Feng Shui: Often chosen in areas with well-developed water systems or auspicious sites, symbolizing the divine protection carried by words. | Natural subject: emphasizes harmony and coexistence with the natural environment. |

| Architectural Style | Visual Characteristics | ① Pagoda-style shape; ② Single architectural level37; ③ Even-numbered geometric shapes38. | ① Simple and unadorned design; ② Practical functionality; ③ Natural materials. |

| Architectural Function | Practical Application | ① Burning paper with characters; ② Emitting smoke; ③ Communicating with the divine; ④ Offering prayers and wishes. | ① Moral education venue; ② Cultural transmission carrier; ③ Warning of cherishing paper. |

| Architectural Decoration | Decorative Motifs | Mythological symbols: Kui Xing Bestowing Success, Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea (八仙过海)39, Carp’s Leap to Dragonhood, Consecutive Triumphs. | Moral education: educating the people through inscriptions to revere the saints and exalt literature. |

| Architectural Metaphor | Cultural Symbolism | ① Buddhist Culture. ② Religious philosophy of Yin–Yang balance: “Assign the yang numbers to the heavens, and the yin numbers to the earth (以阳数配天,以阴数配地)”. | ① A simple appearance metaphorizes the simplicity of Tianli. ② Everyday materials emphasize the reality of Tianli. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Liao, L.; Xie, X. The Dual Ethical Dimensions of “Tian” in Xizi-Belief: Unveiling Tianming and Tianli Through a Hunan Case Study. Religions 2025, 16, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16020194

Zhang X, Liao L, Xie X. The Dual Ethical Dimensions of “Tian” in Xizi-Belief: Unveiling Tianming and Tianli Through a Hunan Case Study. Religions. 2025; 16(2):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16020194

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xin, Lei Liao, and Xubin Xie. 2025. "The Dual Ethical Dimensions of “Tian” in Xizi-Belief: Unveiling Tianming and Tianli Through a Hunan Case Study" Religions 16, no. 2: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16020194

APA StyleZhang, X., Liao, L., & Xie, X. (2025). The Dual Ethical Dimensions of “Tian” in Xizi-Belief: Unveiling Tianming and Tianli Through a Hunan Case Study. Religions, 16(2), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16020194