Abstract

This paper shows the outputs of a study on interfaith dialogue based on community action in Catalonia (Spain). Our hypothesis was to check to what extent interfaith dialogue is a facilitator of community action. The study was carried out between 2023 and 2024 in three phases: the first one devoted to mapping the existing practices within the research context; a second one focused on building an indicators system as well as an instrument for monitoring and assessing interfaith dialogue practices based on community action (the questionnaire QCID_CA); and a third one oriented to identify some conditions for success. We implemented qualitative methods: document analysis, individual interviews, focus groups, active participant observation from an ethnographic position, and comparative analysis. We identified the existing interfaith dialogue practices in Catalonia that are developed under community action; we raised some indicators to assess these practices to promote community action within local contexts; we validated the QCID_CA tool by contrasting it with current interfaith dialogue practices; and we confirmed the dialectical relationship between interfaith dialogue and community action. Interfaith dialogue practices based on community action print a real influence on social interactions in the contexts where they take place. This is the reason to implement a public policy based on some principles like knowledge, acknowledgement, action, and transformation. Interfaith dialogue aims to confront individualism and social fragmentation, which may be the prelude to increasing inequalities and exclusion. It also fights against a passive understanding of citizenship by inviting participants to feel like active agents in raising their standards of living. And more: interfaith dialogue based on community action creates alliances between participants to face the lack of spirituality nowadays. Some limitations were raised from the analysis, mostly related to the number of analyzed cases and the instrument’s implementation. Further research should be required to explore that.

1. Introduction

Interfaith dialogue is a reality worldwide. This dialogue is revealed as a substantial space for a democratic building and social development in Africa (Coppola 2024; Nkulu-N’Sengha 2023), a significant tool to fight against extremism and prejudices in the Middle East and Asia (Cao 2024; Khan 2024), or a strategy to foster social cohesion in Australia (McDonald 2023). Interfaith dialogue grows under the umbrella of a soft-religion understanding (Galtung 1997). A soft-religion paradigm that seeks relationship, mutual understanding, and recognition of the otherness, in front of a hard-religion concept that rather requires intrareligious dialogue.

In Europe, the religious landscape is heterogeneous, with many religious communities living side by side, and interfaith dialogue becomes essential to guarantee religious freedom and social cohesion (Mernissi 2023). interfaith dialogue becomes the path towards a religious pluralism committed to action (op.cit.). This dialogue, as a dimension of a wider intercultural dialogue (Birzea 2008), can be understood under two basic approaches in the European continent: as a field of social action and cooperation and as public policy (Lehmann 2020).

European citizens are supposed to be competent in interreligious dialogue, and these competences should be considered by the school curriculum (Aneas et al. 2023). An interreligious competence that includes dimensions such as: (1) the ability to learn, to understand, and to critically analyze; (2) the capacity to manage the emotions that may arise in these situations of discomfort, ambiguity, or confusion; and (3) the skills required for the regulation of behavior based on all these conditioning factors (op.cit.).

This paper shows the main outputs of research on interfaith dialogue as social action in a specific European context, Catalonia (Spain), with a special focus on the social skills required to implement it. In other words, our aim is to explore the relationship between interfaith dialogue and community action and what conditions shape this dialogue as a good practice for community development. Catalonia has a long tradition of interfaith dialogue, and it is a part of public policy. As stated by the Catalan Religious Diversity Advisory Board (Generalitat de Catalunya 2014), a willingness to achieve mutual understanding is key to the diversity management process and, based on the universal ability to communicate, must prevail in interaction and dialogue between groups. The latest survey on interfaith dialogue in Catalonia identified up to 167 practices between 2022 and 2024, implemented by 15 different religious groups (Sabaté 2024).

Today, the significance of interfaith dialogue, coupled with community action, is increasingly recognized, since religious and cultural diversity is a reality that poses challenges for living together and social cohesion (Orton 2016). This has been particularly highlighted in recent times, exemplified by its reaction to community needs during the pandemic—an example of its paradigmatic importance (Casavecchia et al. 2023)—or other current challenges such as climate change (Albareda-Tiana et al. 2024).

Interfaith dialogue refers to the process of communication and mutual understanding between people coming from different religious traditions and/or beliefs. The aim is to promote harmony and cooperation between these people and to promote peace-building and justice in their communities (Ibrahim et al. 2012), as well as to develop theological and spiritual issues. For many years now there has been a growing recognition of the importance of interfaith dialogue throughout the world. Globalization, increased mobility and immigration, and religious conflicts have led to greater contact and dialogue between people of different religious traditions and beliefs (Mitri 1997).

One of the challenges of interfaith dialogue is that of representativeness. The tendency for dialogue participants to be leaders from predominant religions often misrepresents a community’s religious diversity and minimizes the contributions of grassroots individuals. Moreover, those without religious ties frequently find themselves marginalized from interfaith debates. In addition, people who have no religious affiliation can be excluded from interfaith dialogue, leaving no room for an interconvictional dialogue (Fundació Ferrer i Guàrdia 2022). To face this challenge, research provides evidence on how some groups try to involve a wider spectrum of people, including young people, women, or religious minorities (Cornelio and Salera 2012; Fundació Ferrer i Guàrdia 2021; Kuppinger 2019; Rigual et al. 2022; Sabariego Puig et al. 2017).

Mutual understanding presents another challenge. Religious differences in a framework of diversity can lead to misunderstandings and conflicts. It is not uncommon to find individuals from various religious backgrounds harboring prejudices and stereotypes about the beliefs and practices of others. (Abu-Nimer 2004; Kruja 2021). The literature points out that, to overcome these challenges, interfaith dialogue must be a continuous process based on mutual respect. Communities must be open to learning about the beliefs and practices of others and be willing to question their own beliefs and prejudices (Edwards 2018; Van Esdonk and Wiegers 2019; Helskog 2015; Pope 2021).

Community action, on the other hand, refers to the collaboration between members of a community to face challenges and improve the community’s standards of living (Gomà 2008). This can include activities such as the improvement of the urban environments where these communities live, the promotion of education and training of young people, or the care of people in situations of social vulnerability. Community action is important because it can foster cooperation and empowerment among community members. Like interfaith dialogue, community action encounters its own set of challenges, notably the sustainability of its initiatives over time. Many community action initiatives depend on external resources, which may restrict their reach and long-term action. Moreover, without a clear strategy and a unified vision, these efforts risk becoming fragmented and inefficient. To overcome these challenges, community action must be seen as a long-term investment, a project that goes beyond the here-and-now of our infocratic society (Han 2022). Community action initiatives, for them to become structural, must be based on collaboration and sustained participation (Essomba 2019).

The relationship between interfaith dialogue and community action has been proved since both initiatives aim to promote peace-building, justice, and harmony in society (Ibrahim et al. 2012; Orton 2016). As mentioned above, interfaith dialogue belongs to that soft-religion approach focused on relationships and social development (Galtung 1997). This approach is revealed as coherent with the aim of social transformation associated with community action. Europe is a context where interfaith dialogue is mostly developed as a practical activity oriented to social action (Lehmann 2020). Through interfaith dialogue, prejudices and cultural barriers that exist among different religions and communities can be minimized. This can help foster cooperation and mutual understanding, which can lead to more robust community action and collective problem-solving. Community action can also be a means to promote interfaith dialogue. When working together on community projects, people with different beliefs and cultures can learn about their similarities and differences and develop greater understanding and mutual respect.

In many cases, interfaith dialogue and community action have been monitored to address specific issues, such as the fight against poverty, the promotion of education and training, or the resolution of conflicts, both in an international and a national context (Daddow et al. 2019; Meri 2021; Puig et al. 2018; Baños et al. 2022). In addition, interfaith dialogue and community action can also be a way to face wider social and political challenges. For example, in some countries, religious organizations have worked together to tackle climate change challenges (Purnomo 2020).

However, we cannot avoid mentioning the obstacles in the promotion of interfaith dialogue and community action pointed out in this research. As we said, one of the biggest challenges is the lack of understanding and tolerance that can emerge between communities belonging to different religions and cultures (Abu-Nimer 2001; Edwards 2018; Farrell 2014; Miller 2017; Pallavicini 2016; Vilà Baños et al. 2018). This can prevent collaboration and mutual work on community projects. A certain absence of trust due to historical conflicts between different religious groups can hinder cooperation and community action (Helskog 2015; Kuppinger 2019). In addition, more general challenges in promoting interfaith dialogue and community action can be found. For example, linguistic and cultural barriers that hinder communication between different religious groups (Kruja 2021; Mitri 1997) and logistical and institutional challenges that often arise in the organization of community projects. Despite these challenges, the research literature provides evidence on numerous initiatives around the world to promote interfaith dialogue based on community action. In the context where our research took place, Catalonia (Spain), some studies confirm the potential of both dimensions, from a social perspective (Freixa-Niella et al. 2021) as well as from an educational one (Baños et al. 2022). However, all of them refer to the absence of a systematic collection of practices, the lack of tools to monitor and assess these projects, or the need to highlight the necessary public policy to support it. These are the gaps we aim to fill with our work.

2. Materials and Methods

The methods of this research are qualitative. Our hypothesis was to check to what extent interfaith dialogue is a facilitator of community action. The research was run in three phases. and some specific methods were allocated for each phase. Through all this, we envisaged reaching the following research goals:

- To identify the existing interfaith dialogue practices based on community action in Catalonia.

- To set up an indicators system for monitoring and assessing interfaith dialogue practices based on community action in local contexts.

- To identify conditions for success from the analysis of local practices of interfaith dialogue based on community action.

In phase 1, we first run a literature review together with some interviews with three highly qualified experts in the field. The literature review was conducted by using criteria to ensure the relevance and significance of sources, including public administration publications, NGOs’ reports, and scientific papers. It was helpful to set up scientific networking with other research in process on interfaith dialogue’s mapping and become inspired by some of their preliminary results. Regarding the interviews, they were conducted with three key stakeholders, selected because of their expertise and experience in the field. We balanced their representativeness regarding public administration, social organizations, and academia. The outputs of all these research actions allowed us to set up a first state-of-the-art about interfaith dialogue practices based on community action in Catalonia. Then this draft report was validated by two external judges from AUDIR, the UNESCO Interfaith Dialogue Association. This NGO operates in Catalonia but with an international scope—it organized the World Parliament of Religions—and it is the main stakeholder in interfaith dialogue in the country. The experts from AUDIR refined and improved our findings through a systematic analysis according to Gomà (2008)’s definition. The final output of this phase was an updated map on interfaith dialogue practices based on community action in Catalonia.

In phase 2, the focus of the research was the design of an indicators system for monitoring and assessing interfaith dialogue practices based on community action. This design was made within the frame of a focus group. Three sessions were conducted online: a first for conceptual clarification and categories’ identification; a second one for the indicators design stricto senso; and a third one to validate the draft proposal. The focus group consisted of nine participants representing the public administration, social organizations, and academia. The group dynamics were set on brainstorming, open discussion, and consensus. The output of this phase was a set of indicators for monitoring and assessing interfaith dialogue practices based on community action. We must be aware of the limitations when using it in other cultural contexts since the focus group’s members belonged to the same cultural framework.

In phase 3, we went through a deeper understanding of some interfaith dialogue practices based on community action. During this phase, two cases were chosen intentionally according to criteria of relevance, significance, territoriality, and confessionalism: the case of Badalona and the case of Manresa. Badalona is the third largest city in Catalonia, with a population of 224.301 inhabitants (2023), and is placed within the metropolitan area of Barcelona. It has a long tradition of welcoming migrant populations from all over the world, and it is well known for its rich cultural, religious, and linguistic diversity. On the other hand, Manresa has a population of 80.208 inhabitants (2023), and it is placed in the Catalan countryside. As a pole of attraction of newcomers to work in agriculture and industry, Manresa has a wide religious diversity and one of the longest traditions of interfaith dialogue in Catalonia. The fieldwork on both sites consisted of a total of four interviews, six active participant observations of interfaith dialogue activities, and four document analyses between March and June 2024. Two field reports came up from this fieldwork. Both reports were the key sources of information to proceed on a comparative analysis. The main output of this phase was a validated instrument for monitoring and assessing interfaith dialogue practices on community action.

The theoretical framework for designing the indicators system came from Hatry (2014)’s contributions. Thus, criteria of relevance, clarity, consistency, precision, accessibility, relevance, and adaptability were taken into account in the configuration of the indicators system, and a three-step procedure was followed when leading the focus group: a first step defining objectives and the conceptual frame; a second step identifying measurement areas, that is, identifying the areas or aspects that will be measured; and a third step in defining the indicators that will allow the identified areas to be measured are established. We were aware of this set of indicators to be relevant, clear, consistent, precise, accessible, pertinent, and adaptable.

Regarding the two case studies, we chose the multiple case study method instead of the single case study for several reasons. Since the single case study is used to find out very specific and detailed variables, the multiple case study helps examine patterns and trends, which is what we were interested in observing in terms of interfaith dialogue based on community action. Representativeness was another reason: a multiple case study allows an analysis that facilitates generalization. And a third reason was comparability: the single case study focuses on the depth of a case, while the multiple case study focuses on comparison and provides a more useful overview at the time to design public policies (Mishra 2021). We designed the research process through case selection; data collection through documents, interviews, and active participant observation; analysis of these cases; and a comparative analysis of them.

Table 1 summarizes the methods briefly.

Table 1.

Research methods.

3. Results

3.1. Mapping Interfaith Dialogue Based on Community Action in Catalonia

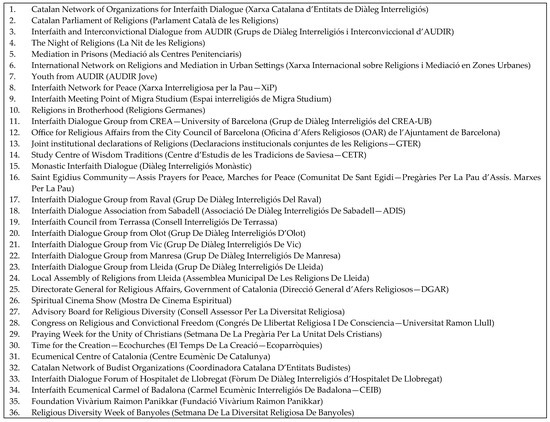

The work carried out in phase 1 provided a first output: a map of interfaith dialogue practices based on community action in Catalonia. This mapping was provided by the document analysis, some interviews with key stakeholders, and the validation process made by two external judges from AUDIR. A total of 36 initiatives were identified, and they can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of interfaith dialogue practices based on community action in Catalonia. Source: Own source in collaboration with AUDIR.

A detailed analysis of the aforementioned identified practices allows us to observe some unique characteristics of how interfaith dialogue based on community action is developed in Catalonia:

- Firstly, we observe the existence of interfaith dialogue groups whose community action consists of meeting the needs of groups at risk of social exclusion, such as young people (AUDIR Jove) or immigrants (Espai Interreligiós de Migra Studium).

- There are also interfaith dialogue groups that address their community action to social groups that are already excluded, such as prisoners (Mediació als Centres Penitenciaris) or neighbors from socially disadvantaged areas (Xarxa Internacional sobre Religions i Mediació en Zones Urbanes; Grup De Diàleg Interreligiós Del Raval).

- Thirdly, we highlight the role that interfaith dialogue plays within local contexts, which allows us to glimpse the relationship between this dialogue and the community action that is carried out in local areas. Catalonia shows a prominent presence of interfaith dialogue groups based on community action to meet the needs of local communities across the whole region (interfaith dialogue groups in Olot, Vic, Manresa, Lleida, Banyoles, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Badalona, Terrassa, Sabadell).

- Another feature of interfaith dialogue based on community action in Catalonia is the intervention of the public administration to promote it. The two most powerful administrations in the region, the Barcelona City Council and the Government of Catalonia, are key stakeholders, and they provide resources to promote this dialogue.

- From a thematic point of view, peace-building is a relevant topic. This is very consistent with the findings in the literature review, where it is stated that “the development of improved dialogue between people identifying with different religious faiths has often been promoted as a positive way of building more cohesive communities in response to the perceived threat and conflict which can arise from divisions” (Orton 2016). Some interfaith dialogue groups focus their goals on the promotion of peace-building, and they implement community action processes to achieve it (Comunitat De Sant Egidi—Pregàries Per La Pau d’Assís. Marxes Per La Pau; Xarxa Interreligiosa per la Pau, XiP).

- Finally, we wish to highlight the connection between the interfaith framework based on community action and the academic world, which promotes reflection on this dialogue and this action (Congrés De Llibertat Religiosa I De Consciència—Universitat Ramon Llull; Grup de Diàleg Interreligiós del CREA-UB; Center d’Estudis de les Tradicions de Saviesa—CETR; Fundació Vivàrium Raimon Panikkar).

This mapping became a starting point to link with phase 2, mostly to define some categories and some quality criteria to be aware of when monitoring and assessing interfaith dialogue based on community action.

3.2. Towards an Indicators System for Improving the Quality of Interfaith Dialogue Based on Community Action

As mentioned, the mapping of interfaith dialogue based on community action provided us with a set of criteria and guidelines on the concept of this dialogue and this action, clearly in line with the findings already found in the literature review.

In turn, the mapping also provided the following emerging questions that became an inspiration for phase 2, devoted to the construction of an indicators system to monitor and assess the quality of practices of interfaith dialogue based on community action in Catalonia:

- Should interfaith dialogue based on community action be limited to the local level, or can we point to practices of interfaith dialogue that seek community action in a more regional or national dimension?

- What should the role of public administration be for the promotion and/or assessment of interfaith dialogue oriented towards community action? Leading role or subsidiary role?

- What should the content of community action be to promote interfaith dialogue? Oriented towards the material needs of the population at risk of exclusion, or more open to the spiritual needs of the whole population?

- How should the approach be, quantitative or qualitative?

- What other indicators exist in this regard at the national or international level? Are these systems transferable to our context?

The focus group was responsible for answering all these questions during the first session, and the following six key categories were identified to become the basic structure of our indicators system:

- Category 1—Individual sense. Under this category we wanted to develop indicators that would allow us to monitor and assess the vital meaning that interfaith dialogue based on community action has for its participants. Indicators that would emphasize the personal growth of the people involved.

- Category 2—Social sense. Closely related to that previous category, we considered a category to bring together indicators on the social meaning of interfaith dialogue based on community action. Here the core to be assessed is the potential of this dialogue to print a significant social impact.

- Category 3—Content. Under this category we wished to design indicators that relate interfaith dialogue based on community action with the thematic focus of such dialogue.

- Category 4—Context. In this category we wished to provide indicators that contribute to clarifying the quality of interfaith dialogue based on community action according to the spaces in which both this dialogue and action take place.

- Category 5—Actors. In this category we wished to design indicators that allow us to assess the quality of interfaith dialogue based on community action according to the typology of social actors who have participated in the dialogue processes.

- Category 6—Process. Under this category we want to raise a set of indicators that would help clarify the quality of interfaith dialogue according to the methods used as well as the management of the activity.

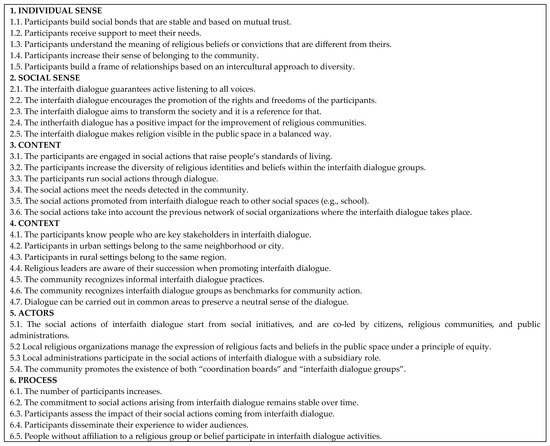

After these preliminary decisions, it became evident that the indicators should be qualitative and thus dive into the intersubjectivity of the focus group members to deal with. Through a creative process using the brainstorming technique and later a process of reflective self-regulation that guaranteed a simultaneous validation of content, the focus group developed a draft proposal of qualitative indicators that can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Indicators system for monitoring and assessing the quality of interfaith dialogue based on community action. Source: Own source.

This set of indicators was followed by the design of an operational instrument to monitor and assess the quality of interfaith dialogue actions based on community action: the QCID_CA questionnaire. This questionnaire aims to be a tool for self-assessment by communities that run interfaith dialogue as community action. The research team transformed the indicators into items and introduced a scale from 1 to 4 to score the degree of agreement (1 = none; 2 = a little; 3 = enough; 4 = a lot). A draft version of the questionnaire pending validation can be found in Appendix A.

3.3. Lessons Learned from the Case Studies Analyses

Research in phase 3 consisted of fieldwork in two case studies. The research goal for this phase was mainly to identify conditions for success when implementing interfaith dialogue based on community action in local settings. The sample was selected from the 36 practices identified in the mapping drawn up in phase 1 and by considering some criteria that emerged from phases 1 and 2. We intentionally selected the local interfaith group in Badalona, as well as the local interfaith group in Manresa. Both groups share the fact of being rooted in local contexts and are therefore suitable for exploring the relationship between interfaith dialogue and community action. They both also have more than three decades of experience in putting interfaith dialogue into practice and a wide diversity of religious groups and cultural backgrounds among their participants. However, they differ in terms of demographic dimension: while Badalona is a large city with a high density and is influenced by its proximity to the capital, Barcelona, the city of Manresa is a small town in the countryside, with social dynamics of community building closer to the rural. This difference was meant to be a key factor to proceed on comparative analysis: the shared features become more significant since they come up in different social contexts.

Through documentary analysis, interviews, and direct participant observation through an ethnographic approach, we developed a rich qualitative data collection in line with the research goals. The criteria for data selection through different sources of information (documents, participants, and observations) were based on the indicators system created in the previous phase. This methodological choice allowed us to meet two necessary quality requirements: on the one hand, to introduce a factor of internal consistency and coherence with the development of the research; on the other hand, to carry out an empirical validation of the indicators to guarantee the design of a high-quality monitoring and assessment instrument.

Two case study reports emerged from a qualitative content analysis, and a comparative analysis was run afterwards. Thanks to the use of the same data collection criteria, we managed to describe a series of common trends for both cases that we may consider as controversial issues. It seems clear that interfaith dialogue will always contain controversial issues, since “there will inevitably be continued differences of opinion about deep matters such as what different participants believe to be true and how that relates to their everyday values and actions” (Orton 2016). Community action should be a platform to recognize these differences and provide a framework to manage them together (op.cit.). These controversial issues are described as follows:

- In both cases, there is a clear intention to distribute leadership among the different participating religious groups. Although the predominance of the Catholic groups over the others is evident due to the roots and presence of this religion in society, there is a clear wish that all groups can perform the big group’s leadership at some point.

- We observed difficulties in management when scheduling a common calendar, since each religious group has its own calendar of religious celebrations, and some overlaps make full participation of all groups difficult.

- Although each religious tradition has a different approach with respect to gender and gender roles, in interfaith dialogue activities, gender roles give rise to a more informal, heterogeneous distribution where men and women tend to carry out shared roles.

- Since most of the participants in interfaith dialogue based on community action are foreigners, the Catalan language (Manresa) or Spanish (Badalona) play a role as a common language for communication and exchange. Participants can express their proposals, beliefs, and concerns in a safe and confident place where everybody can understand each other.

- The spaces for interfaith dialogue based on community action have not been set aside from technological innovations in recent times. Consequently, ICT has been introduced as a communication tool in interfaith dialogue activities to facilitate the participation of some people who could not attend to them. In this case, ICT acts as a key tool to overcome difficulties for participation and attendance.

- The community actions that are promoted through interfaith dialogue mainly promote two values: peace-building and interculturality. Spaces for joint prayer and activities that promote these values in society are carried out. Here, interfaith dialogue becomes a space for active protest, and community action a framework for social transformation.

- Although local interfaith dialogue groups work for the community based on the values above mentioned, some concerns and contradictions also take place. Spaces for interfaith dialogue thus become spaces for conflict and for confrontation of ideas. Dialogue and respect become the regulating values of this confrontation.

- Both local interfaith groups spend time sharing the silence. Contemplation and spiritual connection are a relevant part of their activity. Silence draws a shared common space where each participant can meet their own spiritual needs together with people from other religious groups.

- In both case studies, we observed how participants with different religious backgrounds participate in interfaith religious celebrations where different symbolism and rituals take place. Interfaith celebrations act here as a lever for the understanding of otherness from experience and not only from dialogue.

- Community actions that are projected from interfaith dialogue tend to be oriented towards two purposes. On the one hand, it serves to build community bonds through joint activities that facilitate mutual knowledge, the exploration of relationships, and the construction of social support networks. Here, interfaith dialogue acts as a promoter of a sense of belonging to a shared community. On the other hand, it is a framework for analyzing common social challenges and a platform for action to solve them. Challenges can be related to a social issue (helping people at risk of poverty), an environmental issue (cleaning up a riverbank), or any other kind of problem that affects the community. Social transformation through community action reinforces the value and sense of interfaith spaces.

These controversial issues describe a set of dilemmas that can be tackled through community action and are associated with these conditions for success. These challenges are synthesized in the following Table 2:

Table 2.

Community action challenges emerged from multiple case study analyses.

We must also acknowledge some differences between the two case studies. To identify them, we used the QCID_CA instrument derived from the indicator system, and we carried out an assessment of each case by four academic judges—research team members. This assessment allowed us to achieve two milestones: on the one hand, to carry out an empirical validation of the instrument and refine some of the indicators; on the other hand, to explore the singular features of each case.

The output from empirical validation—the final draft of the instrument—can be found in annex A of this paper. Regarding the differential features of the two cases, we provide the following results:

- The local interfaith dialogue group from Manresa obtained the lowest score—and therefore the greatest need for improvement—in indicators related to the category “Context”. In particular, the interjudge assessment points out future challenges in two indicators: “The participants know people who are key stakeholders in interfaith dialogue”, and “Religious leaders are aware of their succession when promoting interfaith dialogue”. It seems that the local interfaith group from Manresa shows difficulties in ensuring its sustainability and certain confusion regarding the lack of key stakeholders involved in the group’s continuity.

- The local interfaith dialogue group from Badalona obtained the lowest score in indicators related to the category “Actors”. Specifically, the inter-judge evaluation points out limitations in two indicators: “Local religious organizations manage the expression of religious facts and beliefs in the public space under a principle of equity”, and “The community promotes the existence of both coordination boards and interfaith dialogue groups”. Considering the assessment, the local group from Badalona must face challenges related to the public presence of the different religious groups, as well as to the institutional roles of their representation.

In summary, the assessment allows us to easily identify challenges in interfaith dialogue and community action systematically and evidence-based. The Manresa group must face challenges based on its sustainability in its social context, while the Badalona group’s challenges are more related to the actors’ institutional dynamics. As we can see, the instrument derived from the indicators system is revealed as a tool for shaping and pointing out the challenges of interfaith dialogue processes based on community action in local areas.

4. Discussion

According to the research results, a positive relationship between interfaith dialogue and community action is confirmed. However, this was not our research goal, but rather to find out what kind of positive relationship is established and what conditions are necessary for it to be possible.

Our data allows us to state that this relationship is dialectical. Interfaith dialogue has a reflexive nature, while community action has an active one. Apparently contradictory to each other, we observe that the relationship between both social practices strengthens and multiplies the effects that could be expected separately, giving rise to a genuine practice that goes beyond dialogue and action in the service of social transformation.

Thus, community action strengthens interfaith dialogue because, as our results show, such action provides a more participatory framework for dialogue. Community action generates opportunities to create social bonds, to promote acknowledgement among participants from another perspective, and to open senseful social spaces. In turn, interfaith dialogue strengthens community action. Our data illustrates how interfaith dialogue offers an opportunity in community action projects to reflect on diversity, on the meaning of action, and on the ethics beneath.

Furthermore, we also stated the limitations that both interfaith dialogue and community action must deal with without feedback from the others. Of course, there are experiences of community action that are not related to interfaith dialogue, and we wonder how the multiplying effect of the combination of both social practices can be lost. There are also interfaith dialogue practices that are not based on community action; in Catalonia we count almost a hundred of them. We envisage that these practices may have more difficulties in finding a shared sense and understanding by their participants.

Our hypothesis was certainly verified: interfaith dialogue can be a facilitator of community action. It seems clear that interfaith dialogue based on community action constitutes a specific way of practicing this dialogue, and we can define it from a public policy defined by the following four basic principles: (1) knowledge; (2) acknowledgement; (3) action; and (4) transformation.

- Knowledge among participants in interfaith dialogue based on community action makes sense thanks to praxis. Participants must know each other not only to meet each other but to do something together, and this approach nourishes a dimension of interculturality that reinforces this knowledge.

- Knowledge opens the door to acknowledgement. Participants in dialogue also acknowledge each other because they must share time and space to carry out a praxis beyond the logos, and this causes an effect of increasing trust between them. Acknowledgement reinforces a dynamic of openness to alterity.

- Acknowledgement is the condition for projecting action. This action is not senseless but born from a shared will of mutual understanding among participants from different religions. Action requires a positive propensity to otherness, as well as a spiritual sense to carry out a social praxis.

- Finally, action is the condition for transformation. All the voices heard during the research were conclusive—interfaith dialogue must be a space for community action because the main aim of this dialogue is social transformation in accordance with a principle of social justice.

Interfaith dialogue based on community action—through these four principles of knowledge, acknowledgement, action, and transformation—aims to confront individualism and social fragmentation, which may be the prelude to increasing inequalities and exclusion. It also fights against a passive understanding of citizenship by inviting participants to feel like active agents in raising their standards of living. And more: interfaith dialogue based on community action creates alliances between participants to face the lack of spirituality nowadays. Catalonia no longer draws a space of confrontation and struggle between religious groups but between these religious groups altogether and a society empty of spirituality.

Of course, our research has limitations that must be considered. We missed more participation from people who practice interfaith dialogue based on community action, and we wished to analyze more case studies to strengthen the validity of our results with a larger volume of data. Whatever the case, we believe we have opened a path that can provide further research in the future. The Catalan interfaith dialogue practices have learnt the lesson from that Japanese proverb which reminds us that “going on your own, you go faster; going together, you go further”. Let us hope that we will find new chances soon to keep analyzing the way they do it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.V., M.N. and M.À.E.; methodology, A.T.V., M.N. and M.À.E.; validation, A.T.V., M.N. and M.À.E.; formal analysis, A.T.V., M.N. and M.À.E.; investigation, A.T.V., M.N. and M.À.E.; data curation, A.T.V., M.N. and M.À.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.V. and M.À.E.; writing—review and editing, M.À.E. and M.N.; supervision, M.À.E.; project administration, M.À.E.; funding acquisition, M.À.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Generalitat de Catalunya, grant number DGAR22/22/000001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as the local legislation confirmed by the Generalitat de Catalunya. This procedure exempts from processing an Institutional Review Board statement since a superior body and legislation already state that this study is in accordance with the required ethics considerations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data have been compiled and processed in four research reports. These research reports are available in public access in the digital documental repository of UAB, and they can be found through the following links: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/307457; https://ddd.uab.cat/record/307464; https://ddd.uab.cat/record/307465; https://ddd.uab.cat/record/307463 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Indicators System of Quality Criteria for Interfaith Dialogue Based on Community Action

| QCID_CA QUALITY CRITERIA FOR INTERFAITH DIALOGUE BASED ON COMMUNITY ACTION (1 = none; 2 = a little; 3 = enough; 4 = a lot) | ||||

| 1. INDIVIDUAL SENSE | Scale | |||

| 1.1. Participants build social bonds that are stable and based on mutual trust. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1.2. Participants receive support to meet their needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1.3. Participants understand the meaning of religious beliefs or convictions that are different from theirs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1.4. Participants increase their sense of belonging to the community. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1.5. Participants build a frame of relationships based on an intercultural approach to diversity. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. SOCIAL SENSE | Scale | |||

| 2.1. The interfaith dialogue guarantees active listening to all voices. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2.2. The interfaith dialogue encourages the promotion of the rights and freedoms of the participants. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2.3. The interfaith dialogue aims to transform society and it is a reference for that. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2.4. The interfaith dialogue has a positive impact for the improvement of religious communities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2.5. The interfaith dialogue makes religion visible in the public space in a balanced way. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. CONTENT | Scale | |||

| 3.1. The participants are engaged in social actions that raise people’s standards of living. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3.2. The participants increase the diversity of religious identities and beliefs within the interfaith dialogue groups. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3.3. The participants run social actions through dialogue. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3.4. The social actions meet the needs detected in the community. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3.5. The social actions promoted from interfaith dialogue reach other social spaces (e.g., school). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3.6. The social actions take into account the previous network of social organizations where the interfaith dialogue takes place. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. CONTEXT | Scale | |||

| 4.1. The participants know people who are key stakeholders in interfaith dialogue. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4.2. Participants in urban settings belong to the same neighborhood or city. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4.3. Participants in rural settings belong to the same region. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4.4. Religious leaders are aware of their succession when promoting interfaith dialogue. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4.5. The community recognizes informal interfaith dialogue practices. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4.6. The community recognizes interfaith dialogue groups as benchmarks for community action. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4.7. Dialogue can be carried out in common areas to preserve a neutral sense of the dialogue. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. ACTORS | Scale | |||

| 5.1. The social actions of interfaith dialogue start from social initiatives, and are co-led by citizens, religious communities, and public administrations. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5.2 Local religious organizations manage the expression of religious facts and beliefs in public space under a principle of equity. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5.3 Local administrations participate in the social actions of interfaith dialogue with a subsidiary role. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5.4. The community promotes the existence of both “coordination boards” and “interfaith dialogue groups”. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. PROCESS | Scale | |||

| 6.1. The number of participants increases. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6.2. The commitment to social actions arising from interfaith dialogue remains stable over time. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6.3. Participants assess the impact of their social actions coming from interfaith dialogue. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6.4. Participants disseminate their experience to wider audiences. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6.5. People without affiliation with a religious group or belief participate in interfaith dialogue activities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

References

- Abu-Nimer, Mohammed. 2001. Conflict Resolution, Culture, and Religion: Toward a Training Model of Interfaith Peacebuilding. Journal of Peace Research 38: 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Nimer, Mohammed. 2004. Religion, Dialogue, and Non-Violent Actions in Palestinian-Israeli Conflict. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 17: 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albareda-Tiana, S., Mónica Fernández-Morilla, Gregorio Guitián, Francisca Pérez-Madrid, Joan Hernández Serret, and Emilio Chuvieco. 2024. Similaritries and Differences between Religious Communities in Addressing Climate Change. The case of Catalonia. Worldviews—Globlal Religions, Culture and Ecology 28: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneas, Assumpta, Carmen Carmona, Tamar Shuali Trachtenberg, and Alejandra Montané. 2023. Interreligious Competence (IRC) in Students of Education: An Exploratory Study. Religions 15: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños, Ruth Vilà, Asumpta Aneas Álvarez, Montse Freixa Niella, and Melissa Schmidlin Roccatagliata. 2022. Evaluación de competencias para el diálogo intercultural e interreligioso. Estudio exploratorio en estudiantes de secundaria de Barcelona. RELIEVE 28: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Birzea, César. 2008. Presentation of the Recommendation CM/Rec(2008)12 on the Dimension of Religions and Non-Religious Convictions Within Intercultural Education: From Principles to Implementation. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Yanqing. 2024. An Empirical Study of the Effectiveness of Interfaith Dialogue for Peacemaking. The International Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Society 14: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casavecchia, Andrea, Chiara Carbone, and Alba Francesca Canta. 2023. Living interfaith dialogue during the lockdown: The role of women in the Italian case. Religions 14: 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, Nicolamaria. 2024. Religioni, dialogo interreligioso e sviluppo sociale in Africa. Religioni e Società 108: 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelio, Jayeel S., and Timothy Andrew E. Salera. 2012. Youth in interfaith dialogue: Intercultural understanding and its implications on education in the Philippines. Innovación Educativa 12: 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Daddow, Angela, Darren Cronshaw, Newton Daddow, and Ruth Sandy. 2019. Hopeful cross-cultural encounters to suport Student well-being and graduate attributes in higher education. Journal of Studies In International Education 24: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Sachi. 2018. Critical reflections on the interfaith movement: A social justice perspective. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 11: 164–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essomba, Miquel Àngel. 2019. Educación Comunitaria: Crear Condiciones para la Transformación Educativa. Rizoma freireano—Rhizome freirean, n. 27. Instituto Paulo Freire de España. Available online: https://www.rizoma-freireano.org/articles-2727/educacion-comunitaria (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Farrell, Francis. 2014. A critical investigation of the relationship between masculinity, social justice, religious education and the neo-liberal discourse. Education and Training 56: 650–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixa-Niella, Montse, Mariola Graell-Martín, Elena Noguera-Pigem, and Ruth Vilà-Baños. 2021. El diálogo interreligioso: Una asignatura pendiente entre las organizaciones sociales y educativas. Modulema: Revista Científica Sobre Diversidad Cultural 5: 151–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundació Ferrer i Guàrdia. 2021. Feminismes, Religions i llibertat de Consciència. Barcelona: Fundació Ferrer i Guàrdia. [Google Scholar]

- Fundació Ferrer i Guàrdia. 2022. Una laïcitat Inclusiva per una Societat Diversa. Barcelona: Fundació Ferrer i Guàrdia. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, Johan. 1997. Religions, Hard and Soft. CrossCurrents 47: 437–50. [Google Scholar]

- Generalitat de Catalunya. 2014. Religious Diversity in Open Societies. Criteria of Discernment; Barcelona: Department of Justice.

- Gomà, Ricard. 2008. La Acción Comunitaria. Transformación Social y Construcción de Ciudadanía. RES: Revista de Educación Social. Barcelona: Consejo General de Colegios de Educadoras y Educadores Sociales, ISSN 1698-9007, Nº. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2022. Infocracia: La Digilitalización y la Crisis de la Democracia. Taurus Editorial. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8773219 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Hatry, Harry P. 2014. Transforming Performance Measurement for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Helskog, Guro Hansen. 2015. The Gandhi Project: Dialogos philosophical dialogues and the ethics and politics of intercultural and interfaith friendship. Educational Action Research 23: 225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Ismail, Mohd Yusof Othman, Jawiah Dakir, and Abdul Latif Samian. 2012. The importance, ethics and issues on interfaith dialogue among multi racial community. Journal of Applied Sciences Research 8: 2920–24. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Minhas Majeed. 2024. Building Bridges of Understanding: Cross-Cultural Religious Literacy Initiatives in Pakistan. Review of Faith & International Affairs 22: 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kruja, Genti. 2021. Interfaith harmony through education system of religious communities. Religion and Education 49: 104–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppinger, Petra. 2019. Spaces of interfaith dialogue between protestant and muslim communities in Germany. In Gender and Religion in the City: Women, Urban Planning and Spirituality. London: Routledge, pp. 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, Karsten. 2020. Interreligious Dialogue in Context: Towards a Systematic Comparison of IRD-Activities in Europe. Interdisciplinary Journal for Religion and Transformation in Contemporary Society 6: 237–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Gregory. 2023. Factors Influencing Australia’s Uniting Church toward Christian-Muslim Dialogue: Adelaide—A Case Study. The International Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Society 14: 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meri, Josef. 2021. Teaching Interfaith Relations at Universities in the Arab Middle East: Challenges and Strategies. Religions 12: 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mernissi, Fatima. 2023. Interfaith dialogue in contemporary Europe: Challenges and prospects for religious pluralism. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion 15: 182–99. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Kent D. 2017. Interfaith dialogue in a secular field. Management Research Review 40: 824–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Shreya. 2021. Dissecting the Case Study Research: Yin and Eisenhardt Approaches. In Case Method for Digital Natives: Teaching and Research, 1st ed. Edited by Ajoy Kumar Dey. Greater Noida: Bloomsbury, pp. 243–64. ISBN 978-93-54355-21-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mitri, Tarek. 1997. El diálogo interreligioso e intercultural en el espacio mediterráneo en una época de globalización. Perspectivas: Revista Trimestral de Educación Comparada 1: 135–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nkulu-N’Sengha, Mutombo. 2023. Democracy and Interreligious Dialogue in Africa: Prolegomenon for an African Political Theology. Journal of Ecumenical Studies 58: 331–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, Andrew. 2016. Interfaith dialogue: Seven key questions for theory, policy and practice. Religion, State and Society 44: 349–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavicini, Yahya Sergio Yahe. 2016. Interfaith education: An islamic perspective. International Review of Education 62: 423–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, Elizabeth M. 2021. Facilitator guidance during interfaith dialogue. Religious Education 116: 369–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, Marta Sabariego, Montserrat Freixa Niella, and Ruth Vilà Baños. 2018. El diálogo interreligioso en el espacio público: Retos para los agentes socioeducativos en Cataluña. Pedagogía Social: Revista Interuniversitaria 32: 151–66. [Google Scholar]

- Purnomo, Aloys Budi. 2020. A model of interfaith eco-theological leadership to care for the earth in the indonesian context. European Journal of Science and Theology 16: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rigual, Christelle, Wening Udasmoro, and Joy Onyesoh. 2022. Gendered forms of authority and solidarity in the management of ethno-religious conflicts. International Feminist Journal of Politics 24: 368–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabariego Puig, Marta, Angelina Sánchez Martí, and Omaira Beltrán. 2017. Las entidades ante el diálogo intercultural e interreligioso. In Actas XVIII Congreso Internacional de Investigación Educativa: Interdisciplinariedad y Transferencia (AIDIPE, 2017). Salamanca: University of Salamanca, pp. 1613–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté, A. 2024. Mapa del diàleg interreligiós a Catalunya. Ponència presentada a la Jornada de Projectes de Recerca. Direcció General d’Afers Religiosos. Generalitat de Catalunya. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Esdonk, Susanne, and Gerard Wiegers. 2019. Scriptural reasoning among jews and muslims in London dynamics of an inter-religious practice. Entangled Religions 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilà Baños, Ruth, Assumpta Aneas Álvarez, Montserrat Freixa Niella, Marta Sabariego Puig, and María José Rubio Hurtado. 2018. Educar en competencias para el diálogo interreligioso e intercultural para afrontar el radicalismo y la intolerancia religiosas. In Educación 2018–2020. Edited by Teresa Lleixá Arribas. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).