Abstract

This article examines the cult surrounding an esoteric form of Avalokiteśvara, known by different names across regions, such as Cakravarticintāmaṇi, Cintāmaṇicakra, Ruyilun Guanyin, and Nyoirin Kannon. Through an analysis of Sanskrit, Chinese, and Japanese textual sources, the study explores the complex transmission of this cult from India to Southeast Asia and East Asia via the Maritime Silk Routes. As the cult spread, variations in its iconography emerged in different regions. The study highlights how, in India, the bodhisattva was depicted with specific attributes, which were reinterpreted in Southeast Asia. In China and Japan, further modifications appeared, with Chinese representations emphasising the six-armed form that later influenced and matured in Japanese iconography. Additionally, the texts reveal that Cintāmaṇicakra was introduced to royal courts as part of state rituals to ensure the acquisition and preservation of sovereignty. This association with kingship and state protection contributed to the deity’s prominence across the region. The culmination of this transmission occurred in Japan, where Cintāmaṇicakra remains a revered deity to this day. The article concludes that from the 7th to 9th centuries, Buddhist monks were instrumental in spreading the cult of Cakravarticintāmaṇi. As a result, the iconography evolved in response to regional artistic traditions, creating distinct yet interconnected forms of the bodhisattva across the Maritime Silk Routes.

1. Introduction

My first encounter with Cakravarticintāmaṇi Avalokiteśvara occurred during a research trip to Candi Mendut in Java, where a group of philologists and art historians debated the identity of a two-armed stone statue of Avalokiteśvara Padmapāṇi, seated to the right of Mahāvairocana at the centre. Some speculated that this figure could represent Cakravarticintāmaṇi Avalokiteśvara, based on the biography of Bianhong (ca. late 8th century), a Javanese monk and the author of a coronation manual with a possible link to Candi Mendut and who, after travelling to China for a series of spiritual empowerments, was said to have attained the supernatural powers of Cakravarticintāmaṇi. However, the art historians in the group were sceptical, pointing out that the statue lacked key iconographic features: if the figure was indeed Cakravarticintāmaṇi, where was the cintāmaṇi? The bodhisattva’s left hand held a lotus, and the open right palm was empty. This led me to explore further examples of Avalokiteśvara imagery, scrutinising bronzes and paintings where the cintāmaṇi was present. However, I found that very few representations were conclusively identified as Cakravarticintāmaṇi. While several figures held the cintāmaṇi, few also held the cakra, leaving art historians hesitant to attribute them to this specific form of Avalokiteśvara without these defining attributes. The notable exception is Japan, where the deity is known as Cintāmaṇicakra and often possesses both attributes.

Additionally, I have observed that studies of esoteric forms of Avalokiteśvaras have often been divided by discipline and region, and research tends to focus on isolated geographical areas, seldom exploring the transmission of rituals and iconography across regions. My aim, therefore, is to bridge this gap by tracing the journey of Cakravarticintāmaṇi from India through Southeast Asia, China, and Japan via the Maritime Silk Routes,1 offering a comprehensive view of the deity’s spread and development across these cultural landscapes.

Although rooted in art historical analysis, this study extends beyond surveying artistic styles. It seeks to highlight the dynamic relationship between images and texts, emphasising regional variations in attributes, the number of arms, gestures, and other iconographic features as these traditions migrated and evolved across different regions. Furthermore, it underscores the necessity of adopting a multidisciplinary approach—integrating textual, ritual, and art historical studies—to fully understand the esoteric and complex imagery of figures such as this bodhisattva.

By examining the material culture and textual evidence connected to various monks such as Bodhiruci (ca. 6th century CE), Vajrabodhi (671–741 CE), Amoghavajra (705–744 CE), Huiguo (746–805 CE), Bianhong, and Kūkai (774–835 CE), it becomes evident that between the 8th and 9th centuries, a cult of an esoteric form of a bodhisattva bearing a wish-fulfilling gem, known in Sanskrit as the cintāmaṇi, emerged roughly around the same time in the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. In these regions, this form of Avalokiteśvara is referred to by different names: Cakravarticintāmaṇi in India and Southeast Asia, Cintāmaṇicakra in both China and Japan, Ruyilun Guanyin in China, and Nyoirin Kannon in Japan. As evident in other patterns of Buddhist transmission across Asia, the dissemination of the texts and iconography of Cakravarticintāmaṇi occurred via both the overland Silk Roads and the Maritime Silk Routes. However, this study focuses on the transmission along the Maritime Silk Routes, which were likely the primary pathways travelled by some of the aforementioned monks. Historical records reveal that these monks journeyed from India to Southeast Asia, then onward to China, and ultimately to Japan.

As the cult of Cakaravarticintāmaṇi spread, its iconography (see below, Section 3) underwent regional adaptations. In India, the bodhisattva was depicted with specific attributes, which were later modified in Southeast Asia, especially in the Malay Archipelago. By the time the cult reached China, the six-armed form of Avalokiteśvara had become prominent, influencing the depiction of the deity, which gradually spread and matured in Japan (Chutiwongs 2002, p. 301). Building on this observation, this study traces the evolution of the bodhisattva’s iconography across regions, beginning in India and progressing through Southeast Asia to China, and finally to Japan. It explores how region-specific forms emerged, how the iconography transformed as it was transmitted across cultures, and how these forms are interconnected between regions, drawing cross-references to highlight their relationships. This study further reveals that the Cintāmaṇicakra form of Avalokiteśvara held a significant role in state rituals, particularly in royal courts, where it was believed to secure sovereignty and ensure state protection. This association enhanced the Cakravarticintāmaṇi’s importance in royal ceremonies across Asia, culminating in Japan, where Cintāmaṇicakra remains a venerated deity today, particularly within the Mikkyō 密教 tradition of the Shingon sect, which incorporates the “Three Mysteries” (sanmi, 三密)—mudrā, mantra, and maṇḍala—in its practice.

2. Textual Sources on Cakravarticintāmaṇi

The cult and worship of Cakravarticintāmaṇi has been corroborated by the circulation of various Esoteric2 Buddhist texts, originally composed in Sanskrit and spread across Southeast and East Asia. Based on evidence that the aforesaid monks first travelled to Southeast Asia before reaching China, texts attributed to or associated with them were likely transmitted to Southeast Asia and then to China during the Tang dynasty by these monks and their disciples, eventually making their way to Japan. However, other sets of texts might have travelled the opposite route: from India via the overland Silk Roads to China, Korea, and Japan. Among these texts, the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra—translated into Chinese as Guanzizai ruyilun pusa yujia fayao 觀自在如意輪菩薩瑜伽法要 (T. 1087) and was brought to Japan by Kūkai and became known as Kanjizai nyoirin bosatsu yuga hōyō 觀自在如意輪菩薩瑜伽法, which substantiates the iconographical connection between India and Southeast Asia’s Cakravarticintāmaṇi, China’s Ruyilun Guanyin, and Japan’s Cintāmaṇicakra and Nyoirin Kannon as manifestations of the same deity.3

Almost nothing is known about the worship and practices of Cakaravarticintāmaṇi in India due to the lack of textual and inscriptional evidence. In fact, most of the texts in the original Sanskrit have been lost and only their translations in Chinese, which were also brought to Japan survive. Claudine Bautze-Picron (2004, p. 238) argues that the earliest textual source on Cakravarticintāmaṇi/Cintāmaṇicakra is a sūtra translated by the Indian monk Nan-ti in 420 CE, which describes the bodhisattva as possessing the ability to liberate beings from suffering in the six realms of Devas, humans, animals, Asuras, and Pretas. Similarly, the Amitāyurdhyānasūtra, translated by Kālayaśas (383–442 CE), another Indian (or Central Asian) monk who was one of the earlier translators of texts into Chinese, highlights how the bodhisattva emits light from his body to bless beings across the six realms. In Southeast Asia, the only textual information on Cakravarticintāmaṇi can be gleaned from the biography of Bianhong, a Javanese monk4 who travelled to China to be initiated into the Tantric system of Vairocanābhisambhodi under Huiguo (Sinclair 2016, p. 33). Written by Kūkai (also known by his Japanese name Kōbō-daishi), another well-known disciple of Huiguo and the founder of the Shingon sect, the biography reveals that Bianhong attained yogic powers through the worship (sādhana) of Cakravarticintāmaṇi before his journey to China (ibid., p. 31; Sundberg and Giebel 2011, p. 3).

In China, based on a substantial corpus of texts, the cult of Cakravarticintāmaṇi appears to have been more widespread. The principal text concerning the worship of Cakravarticintāmaṇi is the Padmacintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra, which exists in several translations. This repertoire of texts forms part of the Taishō Tripiṭaka 大正新脩大藏經, or the Taishō Canon, which contains several texts that provide detailed instructions for the worship of the deity. The translations, which date back to the late 7th and early 8th centuries, are attributed to Bodhiruci, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra (Fremerman 2008, p. 10), confirming that worship of Cakravarticintāmaṇi was practised during this time. Volume 20 of the Taishō lists twelve texts [no. 1080–1091] that describe homa rituals, talismans, and visualisations of the deity, depicted either with two or six arms. For example, the Guanzizai ruyilun pusa yujia fayao (Skt. Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra, T. 20, 1087, attributed to Vajrabodhi) presents the six-armed form of the deity. Additionally, the Guanshiyin pusa Ruyilun tuoluoni [jing] bing biexing fa 觀世音菩薩如意輪陀羅尼[經]並別行法 [Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva Cintāmaṇicakra Dhāraṇī with Alternative Methods of Cultivation; T. 20, 1080, attributed to Dharmagūpta] outlines instructions on creating talismans and performing various homa rituals, along with their associated benefits. The Guanzizai pusa ruyilun zhou kefa 觀自在菩薩如意輪咒課法 [Method of Using the Spell of Cintāmaṇicakra-Avalokiteśvara; T. 46, author unknown] further elaborates on the usage of Cakravarticintāmaṇi’s spell, while the Foshuo dalun jin’gang zongchi tuoluoni fa 佛說大輪金剛摠持陀羅尼法 [Buddha Preaches the Method of the Great Wheel Vajra Practice of Dhāraṇīs], subtitled Guanshiyin ruyilun wang Monibatuo biexing fa 觀世音如意輪王摩尼跋陀別行法 [Different Method of the Avalokiteśvara Cintāmaṇicakra King Maṇibhadra], attributed to Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, is partly based on T. 1230 and details the use of spells and talismans of Cakravarticintāmaṇi (Sørensen 2011, pp. 41, 58–59). Finally, the Qixing Ruyilun mimi yao jing 七星如意輪祕密 要經 [Scripture on the Secret Essentials of Cintāmaṇicakra and the Great Dipper] (T. 20, 1091, attributed to Amoghavajra) also prescribes the methods of making three talismans.5

It appears that the cult of Cakravarticintāmaṇi in China is particularly associated with the use of talismans, which became popular during the Tang Dynasty and is closely associated with Amoghavajra. Several Dunhuang manuscripts also support this evidence, such as the Guanshiyin Ruyilun tuoluoni huaxiang fa bing biexing wen 觀世音如意輪陀羅尼化相法並別行文 [Method of Avalokiteśvara Cintāmaṇicakra Dhāraṇī for Transforming Forms with the Text of Alternative Practice; P. 2153], which also contains descriptions on talismans (Sørensen 2011, p. 192).

Additionally, given the elaborate and expensive nature of these rituals, it is likely that they were performed by or for bureaucrats and members of the royal family, in line with the religiopolitical context of the Tang state (Goble 2016, p. 127). The association of Cakravarticintāmaṇi with the coronation ceremonies (rājyābhiṣeka) suggests that the deity’s name, meaning “the Emperor of the Wish-Fulfilling Gem”, was symbolically linked to kingship.6

In Japan, the cult of Cintāmaṇicakra reached its zenith of popularity. One of the earliest texts on this deity, the Cintāmaṇicakradhāraṇīsūtra, translated from Sanskrit into Chinese by Bodhiruci in 709 CE, is known in Japanese as the Nyoirin daranikyō (Fowler 2005, p. 121; Pal 2021). Two more texts that specifically outline the visualisation and rituals of Cakravarticintāmaṇi are the Daihōkō Hakurokukaku Zenjū Himitsu Darani Kyō 大寶廣博樓閣善住祕密陀羅尼經 [Sūtra of the Secret Dhāraṇī That Resides Well in the Great Jewel Pavilion] and the Ichiji Bucchō Rin’oh Kyō 一字佛頂輪王經 [One-Syllable Buddhoṣṇīṣa Cakravartin-sūtra], both attributed to Amoghavajra, and are very close in content to the Cintāmaṇicakradhāraṇīsūtra. Shinohara (2014, p. 170) remarks that the former sūtra is categorised as a “recitation manual”, used for the general abhiṣeka (initiation) and the latter as a “yoga manual”, used as a specific manual of the abhiṣeka of a specific deity and many mantras are taken from the Vajraśekharasūtra. Both manuals outline the visualisation of Cintāmaṇicakra with six arms with other common attributes. Later, Kūkai brought back more texts, collectively known as the Gō shorai mokuroku 御請來目錄, which included the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra/Guanzizai ruyilun pusa yuqie fayao and other texts that prescribe the rituals and mantras of Cintāmaṇicakra7 (Fremerman 2008, p. 16).

The bodhisattva often appears androgynous or understood more widely as male in China; in Japan, however, Cintāmaṇicakra is commonly referred to as the “jewel woman” (yunü; gyokujo 玉女).8 This is attributed to several monks who reported having dreams of a goddess promising salvation through love. It is believed that the feminisation of Cintāmaṇicakra in Japan occurred around the mid-9th century (Aptilon 2010, p. 895). This interpretation is also reflected in the Kakuzen-shō 覺禪鈔, a Shingon ritual compendium written by the monk Kakuzen (1143–ca. 1213 CE), dated to 1182 CE, which describes Cintāmaṇicakra as a female deity who grants both liberation and worldly pleasures, as seen in the following passage:

“The mind of wrong views arises, and one is overcome by lustful desires, [so that one] must fall and descend into [this] world. Nyoirin herself becomes the jewel woman of sovereign. [She] becomes his beloved wife or concubine, and they fall in love. For a lifetime [she] adores [him] with blessings and honour, and causes boundless good things to be accomplished. [She] causes him to attain Buddhahood in the Western Pure Land paradise”.(DNBZ 47, 181b–182a; See Fremerman 2008, p. 2)

In addition to such benefits, the Kakuzen-shō also provides instructions on how to conceive a child and alleviate difficulties during childbirth. This suggests that in Japan, the cult of Cintāmaṇicakra was practised not only by male elites but also by women who had access to and were able to read the manuals, or were guided by monks. Similar to China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), where the bodhisattva is also considered an astral deity along with Mañjuśrī and Maming (Sørensen 2011, p. 234), the worship in Japan is also linked to the veneration of the stars, specifically the Seven Stars of Ursa Major or the Northern Dipper. Legend holds that these stars guided Kūkai into the mountains, where an image of Nyoirin was to be enshrined at Kanshinji. This aligns with the content of the Qixing ruyilun mimi yao jing (T. 20, 1091), which prescribes rituals to enshrine Cintāmaṇicakra alongside the stars as the main deities (Fremerman 2008, p. 103–4).

3. The Iconography of Cakravarticintāmaṇi

Various esoteric forms of Avalokiteśvara, including Ārya, Sahasrabhuja-Sahasranetra, Ekādaśamukha, Hayagrīva, Cuṇḍī, Amoghapāśa, and Cakravarticintāmaṇi, originated in India. These forms spread from India via sea routes to Southeast Asia, as well as overland routes through the Himalayan regions to China, gaining popularity during the Tang Dynasty. They are attested in Japan from the 8th century onward (Gethin 1998, pp. 268–69).

Only a handful of images of Cakravarticintāmaṇi have been identified in the Indian subcontinent. While only a few have been identified in Southeast Asia and several more in China, the largest concentration has been discovered in Japan, where the bodhisattva’s cult remains active today. However, the identification of certain esoteric forms of Avalokiteśvara, including Cakravarticintāmaṇi, presents significant challenges. One key issue is the absence of detailed iconography for this form in major Esoteric Buddhist texts, such as the Sādhanamālā and Niṣpaṇṇayogāvalī, which typically prescribe the forms of deities (Pal 2021; Bautze-Picron 2004, p. 242). Furthermore, as Chandra (1988, p. 11) points out, the extensive corpus of textual variants and translations within Esoteric Buddhism further complicates the identification of the deity’s various forms and modes of worship. Moreover, the conflation of several Hindu and Buddhist deities under names like Avalokiteśvara, Lokeśvara, or Lokanātha adds another layer of complexity. As a result, Avalokiteśvara is often identified by generic descriptions, such as “two-armed Avalokiteśvara”, “four-armed Avalokiteśvara”, or “seated Avalokiteśvara”. A notable exception is the twelve-armed Amoghapāśa found in East Java, which can be distinctly identified owing to inscriptions specifying its name.

Before examining the forms and stylistic representations of Cakravarticintāmaṇi across various regions, it is essential to first highlight the distinctive features commonly observed in many of these examples. While the images included in this study exhibit significant variations in the number of arms, mudrās, and attributes, this article will primarily focus on the key attributes and defining characteristics of the Cintāmaṇicakra iconography as it developed in Japan, where this form reached its most mature and widespread expression. These include the mahārājalīlāsana pose, the pensive or contemplative gesture, where the bodhisattva’s head is slightly tilted usually to the right as if gazing downwards and seems to rest on one hand, and most importantly, the central attribute—the cintāmaṇi. Other attributes, however, may vary and will be discussed and compared as needed to provide a comprehensive understanding of regional variations and their interconnectedness.

The mahārājalīlāsana, or “royal ease” pose, where the left leg is pendent horizontally to the body and the right leg is bent vertically, is a variant of the lalitāsana pose (with the right leg pendent and the left leg bent horizontally) and represents meditative repose, equanimity, and aristocracy. In Buddhist art, this posture is mostly seen in the iconography of Avalokiteśvara and Mañjuśrī. It may have been modelled after imported sealings, plaques, bronzes, and paintings, possibly carried by travelling Buddhist monks and pilgrims from South Asia and Southeast Asia, where such āsana is common in the portrayal of these deities, as seen in India, Sri Lanka, and the Malay Archipelago (Huang 2022, p. 8).

According to Pratapaditya Pal (2021), the pensive gesture, which he quotes from a translation of a sūtra by Vajrabodhi (though the specific sūtra is not named),9 suggests that the bodhisattva is contemplating the causes of all suffering. The gesture may derive from the Sanskrit word cintā, meaning ‘thought’, and therefore, the cintāmaṇi is sometimes referred as the “thought-jewel/gem” in art history. This gesture is commonly found in Gandhāran representations of the Buddha and bodhisattvas from the Swat Valley, particularly Maitreya and other figures appearing in the scene of the Great Miracle of Śrāvastī.

The cintāmaṇi—the central attribute of Cakravarticintāmaṇi—usually depicted as an orb or a pear-shaped gem, is a symbol of profound significance in many Hindu and Buddhist myths and philosophies. Generally, it denotes a magical gem capable of fulfilling any desire for whoever possesses it. In Hinduism, the cintāmaṇi is sometimes linked with the kaustubha, the celestial gem of Viṣṇu and a symbol of royal authority, produced during the churning of the ocean as mentioned in the Mahābhārata and various Purāṇas (McHugh 2018). In Buddhism, besides being a divine object as part of the aṣṭamaṅgala and the saptaratna (see notes 2 and 4), the cintāmaṇi is a common attribute in images of bodhisattvas, especially Avalokiteśvara. The Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra, a ca. 5th-century text that praises the virtues of Avalokiteśvara, describes him as wearing a crown adorned with the cintāmaṇi in the middle of his matted locks (jaṭārdhamadhye cintāmaṇi mukuṭadharya) (Bautze-Picron 2004, p. 235). In early Indian art, this concept is visually represented as a round protuberance like a cockade prominently featured in the headdresses of Avalokiteśvara images from Mathura and Gandhāra, dated from the 3rd or 4th century CE (ibid., p. 235).

In China, the cintāmaṇi also came to symbolise the Dharma and Dharmakāya (unmanifested body of buddhas and bodhisattvas) during the Tang Dynasty (Chen 2020, p. 233) and the bodhisattva’s limitless blessings and unfailing answer to prayers (Yu 2001, p. 12). Besides images of Avalokiteśvara possessing the cintāmaṇi, depictions of other bodhisattvas such as Mañjuśrī and Kṣitigarbha,10 as well as other forms of material culture from the Tang period, such as paintings of arhats11 and religious or state banners, also feature the cintāmaṇi motif, suggesting that the cult of cintāmaṇi was widespread. Texts such as the Bodhisattvagocaropāyaviṣayavikurvaṇanirdeśa and the Daśacakrakṣitigarbhasūtra, translated by Bodhiruci and Xuanzang (602–664 CE), respectively, outline that the cintāmaṇi has eight virtues: relieving the suffering of sentient beings, curing sickness, preventing harm from beasts, releasing one from prison, and providing riches, wealth, and other material comforts (Chen 2020, p. 235).

In Japan, the cintāmaṇi usually takes the form of a pearl, which can be spherical, oval, round, or heart-shaped, and is believed to grant all desires (Saunders 2018, p. 154). In some contexts, the motif represents the Triratna—the Buddha, Dharma, and Saṅgha—and in esoteric doctrine, the cintāmaṇi symbolises the manas, or the sixth sense (ibid, p. 155), which could correspond to the six arms of the bodhisattva. Moreover, the cintāmaṇi motif played a pivotal role in the deity’s iconographical transformations, sparking a chain of new connections with both local and imported Indian deities. This process, which Faure (1999) calls ‘metonymic drift’, eventually linked the cintāmaṇi with relics of the Buddha. Kūkai is said to have received the cintāmaṇi from a Nāga King and given it to the Japanese court, where it eventually became a regalia of the legitimation of imperial power (Faure 1999, p. 16; 2015, p. 235; Chen 2020, p. 236). The possession of the cintāmaṇi or relic as a sacred, physical object became crucial to legitimising royal authority, beginning with the Shirakawa feudal domain (r. 1072–1086). Ono Shingon rituals played a key role in supporting this legitimacy through a ritual system centred on the deity and the cintāmaṇi. For example, the Ono monks performed the worship of Cintāmaṇicakra and the object cintāmaṇi near the ruler’s chamber in the imperial palace for the protection of the nation (Aptilon 2010, p. 897). Furthermore, Cintāmaṇicakra assimilated or became associated with local deities who also possess the cintāmaṇi, such as Seiryō Gongen (the female Nāga and dragon deities), Benzaiten (Sarasvatī), Kichijōten (Lakṣmī), and Dakiniten (Ḍākiṇī), the flesh-eating deity who became central to Shingon imperial ordination ceremonies (Fremerman 2008, p. 14 and Aptilon 2010, p. 895).

The cakra is another significant attribute that occasionally appears in depictions of Cakravarticintāmaṇi, though, as this study illustrates, it is not always included. The cakra, a prominent symbol of authority, epitomises the ideal king or Cakravartin in both Hinduism and Buddhism. It also symbolises the wheel and, by extension, the solar disc. In Buddhist tradition, the cakra represents the Buddha, who is revered as a descendant of the solar dynasty and embodies the universal emperor. The Buddha, as the Cakravartin, sets the wheel of dharma into motion, radiating in all directions. Furthermore, the cakra serves as an abstract symbol in early Buddhism, signifying the teachings of the Buddha, as evidenced at Bhārhut and Amarāvatī. Saunders (2018) notes that the cakra shares an affinity with the lotus: just as the sun causes the lotus to rise above the water and bloom, the eight spokes of the cakra correspond to the lotus’s eight petals. These spokes symbolise the eight cardinal directions, the Noble Eightfold Path, and other related concepts.

Regarding the iconography of the deity as a whole, in the Dictionary of Buddhist Iconography (Chandra 1999, p. 809), Lokesh Chandra provides a table detailing various forms of Cakravarticintāmaṇi/Cintāmaṇicakra/Nyoirin Kannon from various countries, mostly from China and Japan, with two, four, eight, ten, eight, and twelve arms, each associated with different combinations of attributes. A table (See Chandra 1999, p. 809) highlighting different attributes of the deity demonstrates that the cintāmaṇi is not always a required feature. For instance, the second example of the two-armed form depicted in the Zuzō-shō,12 only shows the abhayamudrā and varadamudrā, without any additional attributes.

Nevertheless, the most commonly observed form of this bodhisattva today features six arms, seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose, displaying a pensive gesture, and holding a cakra and a cintāmaṇi, along with the other attributes previously mentioned. This fully developed form is prominently seen in Japan. The significance of the six arms may symbolise the six perfections (ṣaṭpāramitānirdeśanakarāya) (Bautze-Picron 2004, p. 235) and the six realms of existence, as represented in the ṣaḍākṣarī-mahāvidyā mantra: oṃ maṇi padme hūm—the principal mantra (mūlamantra) of Avalokiteśvara, introduced to China by the monk Zhiyi (538–592 CE) in the 6th century CE (ibid., p. 238).

4. Indian Subcontinent

Very few depictions of Avalokiteśvara in India have been identified as Cakravarticintāmaṇi, and those that have are still subject to debate. As mentioned earlier, this uncertainty likely stems from the scarcity of textual and inscriptional evidence. Hence, only a handful of Cakravarticintāmaṇi images have been recognised within the Indian subcontinent. Chandra (1999, p. 819) lists three examples from India:

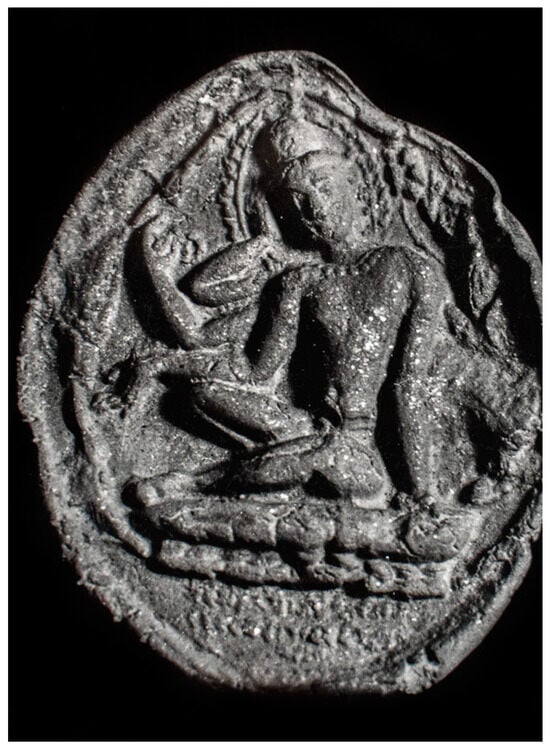

- A terracotta sealing from Nālandā, housed in the Ashutosh Museum of Indian Art, Calcutta University, and described by Pratapaditya Pal (JISOA 2/1967–1968, pp. 39–48, pl. XIII). (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Clay sealing depicting Cakravarticintāmaṇi, Nālandā. Prapatditya Pal (2021).

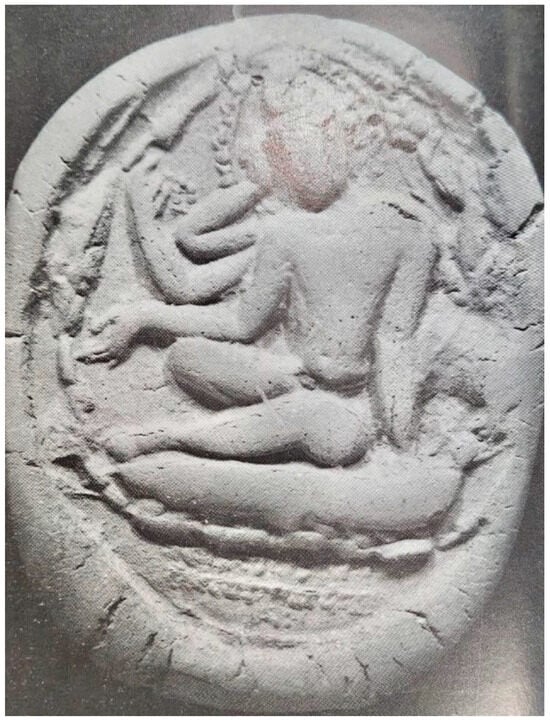

Figure 1. Clay sealing depicting Cakravarticintāmaṇi, Nālandā. Prapatditya Pal (2021). - A Nālandā sealing in the Bharat Kala Bhavan, Benares Hindu University (acc. no. 5250), described by T. K. Biswas in Certain Rare Aspects of Avalokiteśvara in Bharat Kala Bhavan. (Biswas 1989, pp. 175–80). (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Clay sealing depicting Cakravarticintāmaṇi, Nālandā. T. K. Biswas (1989).

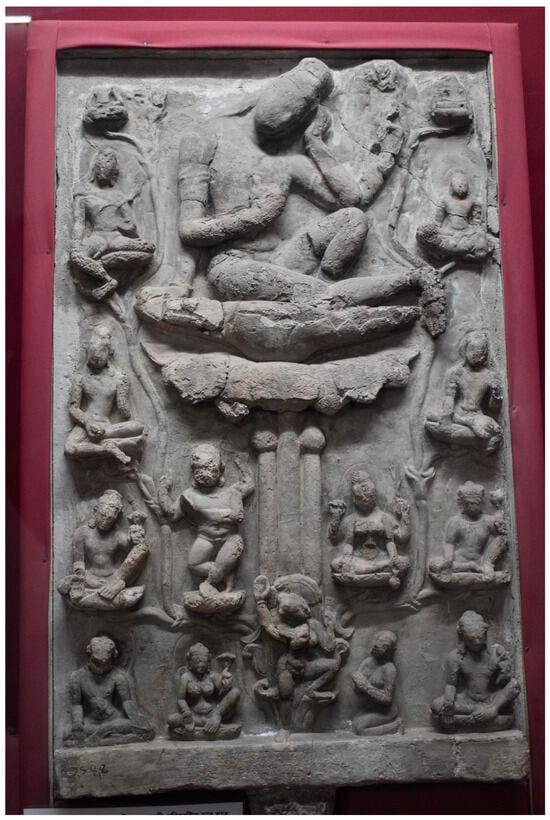

Figure 2. Clay sealing depicting Cakravarticintāmaṇi, Nālandā. T. K. Biswas (1989). - A stone panel from Koṭilā-murā in Mainamati (also known as Paṭṭikera, now in Bangladesh), dating to the 10th or 11th century, described by Frederic M. Asher in The Art of Eastern India (Asher 1980, p. 112). (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Stone panel depicting four-armed Cakravarticintāmaṇi, Kotila-mura, Mainamati. Photography: Abira Bhattacharya.

Figure 3. Stone panel depicting four-armed Cakravarticintāmaṇi, Kotila-mura, Mainamati. Photography: Abira Bhattacharya.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 are identical sealings from Nālandā, probably made from the same mould, identified by Chandra (1999) and T. K. Biswas (1989) as Cakravarticintāmaṇi. The six-armed bodhisattva is seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose on a lotus. His hair is fashioned in the jaṭāmakuṭa style and he wears only a necklace on his bare torso. His head tilts to the right side of the body, resting on the upper right hand. The second right hand holds the akṣamālā (rosary), while the third rests on his right knee in the varadamudrā gesture, possibly holding the cintāmaṇi. Of the three left hands, only one is visible, resting on the lotus seat, while the other two are either damaged or not clearly formed due to defects in the mould. Below the lotus, there is an unreadable two-line inscription. Based on the style, Pratapaditya Pal (2021) suggests that the plaque dates to the 9th century. It is also noteworthy that Vajrabodhi, to whom the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra is attributed, was trained and taught in Nālandā before he travelled to China (Pal 2021).

Figure 3 shows a panel carved of soft stone from the stūpa at Koṭilā-murā in Mainamati (in present day Bangladesh) (See Asher 1980, p. 63), depicting a profile of a four-armed Avalokiteśvara with the left leg bent in the mahārājalīlāsana pose and the right leg extended, suggesting a variation of the mahārājalīlāsana pose. The deity’s hairdo is in the jaṭāmakuṭa style, but no image of Amitābha is visible in the hair. The figure’s head tilts to the left, supported by the raised left hand in the pensive gesture, while the right hand is held at chest level, possibly holding the cintāmaṇi. Due to the panel’s age, the object and other attributes in the remaining hands are not discernible, making confirmation difficult.

Figure 4 shows an unstudied terracotta sealing at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. It is a terracotta, lamp-shaped sealing dated to the 9th century, depicting a two-armed bodhisattva with the jaṭāmakuṭa hairstyle, seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose. The right hand stretches out with an open palm, possibly holding the cintāmaṇi, but it is unclear due to wear. The ambiguity of this object may lead some to interpret the gesture as varadamudrā. The left arm is bent, resting on the head of either a human or an anthropomorphic figure. The background of the piece shows a foliage motif, likely a lotus, the bodhisattva’s primary attribute. The museum identifies the figure as Avalokiteśvara. However, this image is very similar to the Nālandā sealing (Figure 1), dated to the same period and identified by Pratapaditya Pal (2021) and Lokesh Chandra (1999) as Cakravarticintāmaṇi. Both figures are seated in identical poses, with their right hands extending forward in the same manner. The key difference between the two images is the number of arms.

Figure 4.

Terracotta sealing showing a two-armed Avalokiteśvara, 9th century, Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

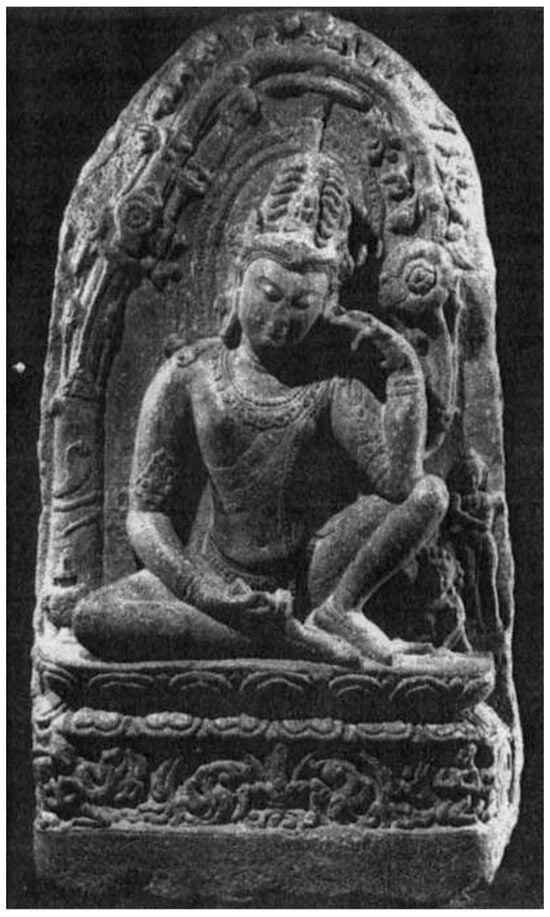

Claudine Bautze-Picron (2000) published an image of a two-armed Avalokiteśvara from the Pāla period (Figure 5), which she identifies as possibly representing Cintāmaṇicakra. This identification is based on the cintāmaṇi held in the right hand placed on the right thigh and the cakra depicted in the tree in the background, among other objects, which Bautze-Picron interprets as the saptaratnas (seven treasures of the Cakravartin). The bodhisattva, also characterised by a tall jaṭāmakuṭa hairstyle with Amitābha at the centre, is seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose and displays a pensive gesture, touching his left cheek with the index finger of his left hand. Other significant attributes of the bodhisattva in this composition include the lotus stem stretching beside the left arm and extending above the left shoulder, as well as the kamaṇḍalu placed beside his right knee. Two figures are seen on the left side of the bodhisattva; these could either be human devotees or the bodhisattva’s attendants, Hayagrīva and Sudhanakumāra. Gouriswar Bhattacharya (2002) suggests that this image originates from Bodhgayā in Bihar and represents Maṇipadmā Avalokiteśvara, a feminine interpretation of the male bodhisattva, depicted holding the cintāmaṇi.

Figure 5.

Grey stone relief of Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara from Bihar, Pāla Period c. 9th century CE, Neumann Collection, Switzerland.

5. Southeast Asia

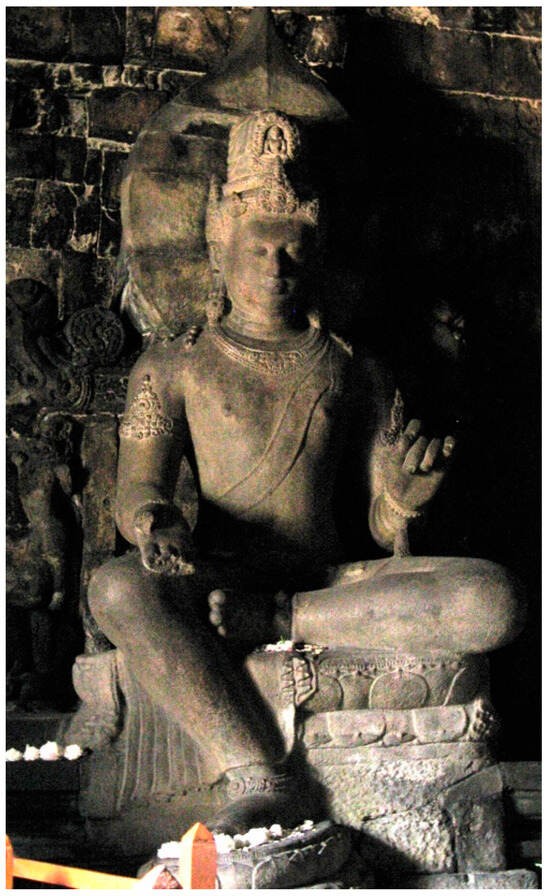

In Java, many images of Avalokiteśvara exist, but they are seldom identified by their specific forms, and no stone and very few bronze sculptures have been definitively recognised as Cakravarticintāmaṇi. Presently, the colossal statue of Avalokiteśvara seated in lalitāsana (Figure 6), located to the right of Mahāvairocana, seated in the bhadrāsana pose at the centre of Candi Mendut, is the only stone sculpture tentatively associated with Cakravarticintāmaṇi. This link is primarily due to Candi Mendut’s association with Bianhong, a Javanese monk whose work, Ritual Manual for Initiation into the Great Maṇḍala of the Uṣṇīṣa-Cakravartin (T. 959) (See Sinclair 2016, p. 2), may have been connected to the temple, which was potentially used for state coronation ceremonies.13 The identification is further supported by a faintly visible orb in the right hand, which could represent the cintāmaṇi. However, there remains scholarly debate over whether the protrusion in Avalokiteśvara’s right palm is a cintāmaṇi or simply part of the figure’s anatomy.

Figure 6.

The stone sculpture of the two-armed Avalokiteśvara, early 9th century, Candi Mendut.

The Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra (Ch. Guanzizai ruyilun pusa yujia fayao), which details the iconography of Cakravarticintāmaṇi in its visualisation verses, somewhat corresponds with Raffles’ sketch14 (Figure 7) and has been identified as Cakravarticintāmaṇi in Sinclair’s research (Sinclair 2016). This text may provide crucial insights in clarifying the identities of these images. The relevant passage is as follows:

Figure 7.

Six-armed Cakravarticintāmaṇi, metal statuette, 7th–9th century, current location unknown; drawing in Raffles (1817, II, pp. 56–57, third page of plates).

“The first [right] hand is pensive due to [his] sympathising [with] beings. The second holds a wishing gem, which can fulfil desires. The third holds a rosary, as though lifting out from the suffering of rebirth. The left [hand] holds down the radiant mountain, succeeding in not upturning [it]. The second holds a lotus, which can purify sinful dharmas. The third holds a wheel, which can circulate the unsurpassed dharma” (T. 20, 1087.213b17, 20–25).(See Sinclair 2016, p. 32).

However, the passage above and Raffles’ sketch do not align perfectly, as the cakra is missing from the sketch, and other attributes differ from those described in the text. It is possible that the cakra was originally depicted above the index finger of the upper left hand, as seen in the bronze image from the Ashmolean Museum (listed next, Figure 8) and Japanese depictions of the bodhisattva (listed later), but it has since been broken off. Alternatively, the cakra may have been present in the lower right hand, similar to its depiction in a silk painting from Dunhuang held at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (listed in the next section). Notably, the sketch already shows an object in the lower right hand, resembling a pāśa (noose).

Figure 8.

Gilt bronze figure of the six-armed Cintāmaṇicakra, late 9th-early 10th century. Ashmolean Museum, EA2013.80.

Conversely, one attribute—the kamaṇḍalu (water pot) held in the bodhisattva’s lower left hand—is not described in the passage from the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra quoted above. Furthermore, the lotus mentioned in the text is also absent. It is plausible that the lotus was originally present in the upper left hand, as a long, foliage-like form is visible flowing down the upper left arm and extending all the way to the base of the statue. However, it is unlikely that the lotus and the cakra would have both appeared together in the same hand, as the attributes are typically distributed across different hands in such iconography. It is also plausible the cakra may not have been depicted at all from the beginning.

Sofia Sundström’s (2020) thesis on the iconography of Avalokiteśvara includes a chapter and extensive catalogue on “The Sorrowful Avalokiteśvara” (Catalogue Nos. 85–119). All thirty-four bronze depictions of Avalokiteśvara, despite having two, four, or six arms, are mostly shown seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose and share key attributes such as the jaṭāmakuṭa, padma (lotus), akṣamālā (rosary), pustaka (book), and notably, the cintāmaṇi in most cases. The overall characteristics of these representations correspond to either Indian or Central Javanese style and align with certain iconographic details found in the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra and Raffles’ sketch, which is also featured in Sundström’s catalogue (Cat. No. 113). However, only two of these images (Cat. Nos. 114 and 115) portray Avalokiteśvara with six arms.

Sundström’s catalogue includes five bronze examples of two-armed Avalokiteśvara (Cat. Nos. 85–89), seated in either lalitāsana or mahārājalīlāsana. In all but one of these images, the head rests on the right hand in the pensive pose, and the cintāmaṇi is clearly visible in the left hand, either stretched out or held at chest level. For the four-armed bronzes, there are twenty-three examples (Cat. Nos. 90–112), all seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose on a lotus base. Many of these also feature a prabhāmaṇḍala (mandorla) and a chatra (parasol) (some of which are broken) behind the figure (Cat. Nos. 90, 96–106, 109–110). Most significantly, each of these examples holds a cintāmaṇi in either the right or left hand at chest level, with the head resting contemplatively on one hand, usually the right. Other key attributes include the jaṭāmakuṭa (with Amitābha visible in some examples), yajñopavīta, and in some cases, a pustaka. These figures are also richly adorned with jewellery such as bracelets, armlets, anklets, necklaces, and diadems.

There are three bronze images of six-armed Avalokiteśvara, including the Raffles sketch, all seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose. The Cat. No. 114 image has three damaged arms, making it difficult to identify their attributes, but the head is still seen resting on the upper right hand in the pensive pose. The gilt bronze statue from the Ashmolean Museum (Cat. No. 115; Figure 8) is the only image Sundström refers to as “Cintāmaṇicakra Avalokiteśvara”, likely due to the clear depiction of both the cintāmaṇi and the cakra held by the upper left hand. Some features of this image resemble Raffles’ sketch (Cat. No. 113), apart from the missing cakra, and it is nearly identical to the description of Avalokiteśvara’s iconography in the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra, except for the kamaṇḍalu held by the middle left hand in Raffles’ sketch. Furthermore, the bodhisattva’s outstretched lower hand holding the cintāmaṇi resonates with the six-armed images on the clay plaques from India (Figure 1 and Figure 2), where the cintāmaṇi is also held in the outstretched lower right hand. The differences lie in the representations of the cakra. In the Indian examples, the cakra is not depicted and the lower left hand is placed on the ground, supporting the body. At the same time, the Ashmolean bronze shows the bodhisattva holding an undeterminable object that could represent other important attributes, such as the akṣamālā or the padma, as described in the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra.

In the same section of the catalogue, Sundström further lists four baked-clay sealings depicting Avalokiteśvara: two examples with two arms and another two examples with four arms (Cat. 116–119). These originate from Southern Thailand, Bali, and Myanmar. All four sealings depict the bodhisattva seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose. The first example features two arms—the right hand touching the head with the pensive gesture, and the left hand supporting the body on the floor. The remaining examples, with four arms, display varied hand positions similar to the bronze figures mentioned earlier. The cintāmaṇi is not clearly visible due to the nature of the clay objects, but it is either resting on an outstretched palm or held at chest level. These sealings closely resemble those from India, with the outstretched lower left hand possibly holding the cintāmaṇi, suggesting a shared iconographic tradition and the transmission of Avalokiteśvara’s imagery across regions, facilitated by the portability of such artefacts.

6. China

In China, countless images of Avalokiteśvara exist, both standing and seated, yet in museums and digital resources, few are identified as Cintāmaṇicakra, or by the Chinese name, Ruyilun Guanyin. It is said that the caves at Dunhuang contain thirty-nine images of Cintāmaṇicakra in total, second only to images of Sahasrabhuja, which are forty in number (Yu 2001, p. 84). The earliest known image from Dunhuang may be the clay figures from niches in Mogao Caves 148 and 384, dated to 776 CE, but unfortunately, many of these images are now missing. Closest to these examples is probably the silk painting from Dunhuang housed in the British Museum, dated to the 9th century CE (Figure 9), labelled “Cintāmaṇicakra Avalokiteśvara”. This painting depicts a six-armed bodhisattva seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose with hair styled in a jaṭāmakuṭa with an image of Amitābha, alongside other significant attributes such as the cintāmaṇi and cakra, affirming the bodhisattva’s identity. Although the six-armed bodhisattva’s attributes are challenging to discern due to its age, it is obvious that the left hand, held at chest level, is supporting an object. In the light of the analysis of the bronzes from Java discussed above as well as the bronze statue from Sotheby’s (listed next, Figure 10), this object is most likely the cintāmaṇi. Among various possible reasons, one compelling argument is that the cintāmaṇi is the most common attribute of Avalokiteśvara, typically held at chest level. The placement of the cakra is not easily identifiable in the image from the British Museum. However, by comparing the British Museum image with another silk painting from Dunhuang, housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Figure 10) and dated to the same period, we observe that the flaming cintāmaṇi is held in the right hand at chest level, while the cakra is positioned in the lower right hand. This suggests that in the statue from Sotheby’s, the cakra was possibly held in the lower right hand, which is depicted in katakamudrā,15 a gesture indicating the act of holding an object. Notably, in the Dunhuang painting, the cakra in the lower right hand is rendered with a transparent quality, emphasising its celestial divine nature.

Figure 9.

Silk painting of the six-armed Cintāmaṇicakra from Dunhuang, 9th century, British Museum, 1919.0101.0.10.

Figure 10.

Silk painting of the six-armed Cintāmaṇicakra from Dunhuang, 9th century, Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Sotheby’s listed a gilt-bronze image of a six-armed Avalokiteśvara (Figure 11), dated to the late Tang dynasty, which was sold in 2019. In this piece, the bodhisattva, with clear Chinese facial and costume features, is seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose on a lotus pedestal, displaying typical attributes, such as the jaṭāmakuṭa hairstyle with Amitābha at the centre. The head rests on the upper right hand in the pensive gesture, and the cintāmaṇi is visibly held in the right hand near the chest. However, the cakra, which was probably held in one of the hands, has been broken off. At first glance, the overall iconography of this bronze closely resembles Raffles’ sketch and the Javanese bronze in the Ashmolean Museum, particularly in the āsana, with the number of arms, the mudrās, and the presence of the cintāmaṇi. However, upon closer examination, certain attributes depicted in Raffles’ sketch are either arranged in different hands or are absent altogether—namely, the akṣamālā in the upper right hand and the kamaṇḍalu in the lower left hand. Moreover, the bodhisattva holds a lotus stalk in the middle left hand, which resembles the Japanese images from the Murōji Temple and Kanshinji Temple (listed in the next section), suggesting a possible connection.

Figure 11.

Gilt bronze figure of the six-armed Cintāmaṇicakra, late 9th–early 10th century. Sotheby’s auction, sold in 2019.

Another depiction is a wall painting (tempera on clay) at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Figure 12), titled “Ruyilun Guanyin (Cintāmaṇicakra) Bodhisattva Seated on the Lotus Throne”, dated between 951 and 953 CE from the Cisheng Monastery in Henan Province. The two-armed bodhisattva is depicted in the padmāsana pose on a lotus. The hair is tied in the jaṭāmakuṭa style with Amitābha at the centre. Although some damage obscures the attributes in the hands, they appear to be positioned together in either the dharmacakramudrā or its variation, the dharmarājamudrā16, without any visible attributes. Instead, the cakra, one of the main attributes, may be symbolically represented by the dharmacakramudrā itself, which signifies the Buddha’s preaching and the setting of the wheel of dharma into motion (Bunce 2005, p. 58). Furthermore, the cintāmaṇi can be interpreted as embodying the Dharmakāya body of the bodhisattva, as discussed earlier in the previous section.

Figure 12.

Painting of the two-armed Ruyilun/Cintāmaṇicakra, ca. late 9th–early 10th century, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 52-6.

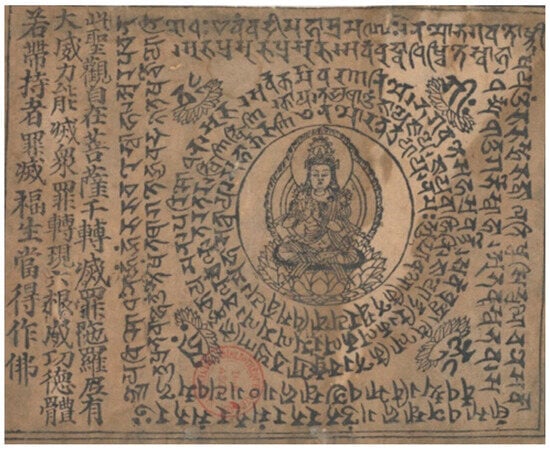

A similar image to the Nelson-Atkins’ two-armed Cintāmaṇicakra is found in printed dhāraṇīs from Dunhuang (Figure 13), called Shengguan zizai pusa qianzuan miezui tuoluoni 聖觀自在菩薩千轉滅罪陀羅尼 (Dhāraṇī of a Thousand Turns of the Saintly Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara Who Expiates all Crimes), which were used as talismans. There are thirty copies of these, measuring 14 × 17 centimetres, printed on a single sheet of paper. The two-armed bodhisattva is depicted at the centre with the hands together in the same manner as in the Nelson-Atkins painting. The figure is surrounded by Sanskrit mantras, including bījākṣaras (seed syllables) written in Nāgarī script. There is also a Chinese explanation to the left of the dhāraṇī, which states that for the talisman to be effective, it should be cut (into separate sheets), rolled up, and carried on the body (Li and Ma 2017, p. 340). Additionally, a handwritten Chinese title at the top reads Jiuchannan tuoluoni 救產難陀羅尼 [Dhāraṇī for Delivery from Childbirth Obstacles], confirming that it is a talisman for the safe delivery of children. Although Li and Ma (2017) do not identify the talisman image as Cintāmaṇicakra, the widespread cult of this bodhisattva during the Tang period, as described by Yu (2001), underscores its significance. Yu notes that Cintāmaṇicakra was the second most-frequently depicted form of Avalokiteśvara in the material culture of Dunhuang. Furthermore, evidence suggests that Cintāmaṇicakra was widely worshipped in China and Japan as a deity associated with safe childbirth. The Nelson-Atkins painting has also been proposed to depict Cintāmaṇicakra. Thus, it is plausible to suggest that the bodhisattva images on the Dunhuang talisman may represent the same bodhisattva or are closely related to the two-armed form of Cintāmaṇicakra found in Japan, such as the example discussed in the next section. This Japanese form is also depicted seated on a similar lotus pedestal and appears to display the dharmacakramudrā at chest level.

Figure 13.

Printed Dhāraṇī of a Thousand Turns of the Saintly Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara Who Expiates all Crimes from Dunhuang depicting two-armed Avalokiteśvara, ca. late 9th–early 10th century, Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The production of talismanic devices for various purposes, particularly for protection during pregnancy, as exemplified by the Dunhuang Cintāmaṇicakra talismans, was also significant in the cult of Mahāpratisarā in Java. Cruijsen et al. (2014) identify Mahāpratisarā as a “textual deity”, with her mantras and attributes—such as protection and blessings—elaborated in the Sanskrit dhāraṇī Mahāpratisarāmahāvidyārājñī, dated to the first half of the 7th century CE. While this dhāraṇī provides instructions for crafting amulets adorned with specific symbols, it does not detail her iconography. Over time, these symbols became central to her depiction, as outlined in texts such as the Sādhanamālā and Niṣpannayogāvalī. A mantra from the Mahāpratisarāmahāvidyārājñī is inscribed on the back of a bronze statue from Java, now preserved in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, confirming its association with Mahāpratisarā. This suggests that the statue’s creation likely relied on at least two textual sources. Similarly, this evidence raises the possibility that Cintāmaṇicakra may have also originated as a dhāraṇī deity, as descriptions of bodhisattvas are frequently recorded in dhāraṇīs as previously described. Cintāmaṇicakra’s visual representations, too, were also likely drawn upon diverse textual traditions.

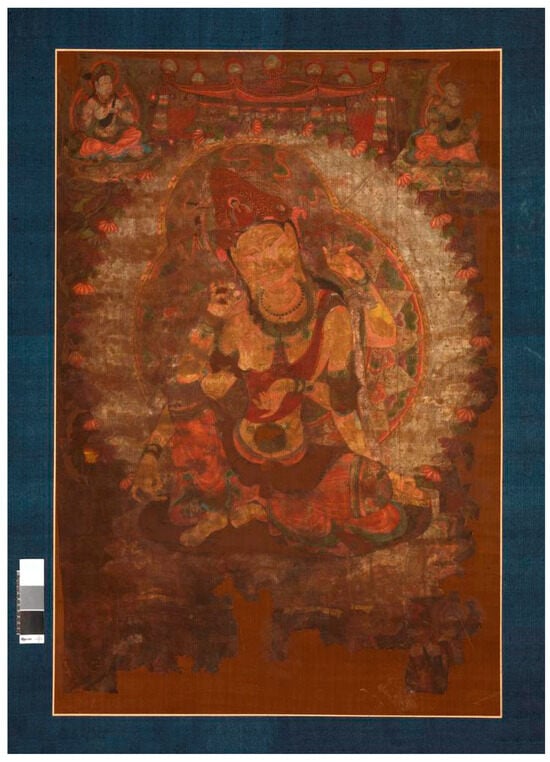

In her 2021 study, Tamami Hamada identified Cintāmaṇicakra in two paintings from Dunhuang among the retinue of deities attending Sahasrabhuja-Sahasranetra (Thousand-armed) Avalokiteśvara. These paintings, from Mogao Cave 17 and dated to the Tang dynasty, show the bodhisattva in the mahārājalīlāsana pose with four arms: the cintāmaṇi held at the chest in the lower left hand and the cakra suspended on the index finger of the upper left hand. Another image of Cakravarticintāmaṇi appears in the same type of painting in the Dunhuang manuscript P. 3352, now at the Musée Guimet and dated to the 10th century CE. Though the image is not currently accessible, Hamada states that the bodhisattva is similarly positioned to the upper left of Sahasrabhuja. The same depiction can be found on the north wall of the main enclosure of Yulin Cave 36 and in a banner painting (MG 17659; Figure 14) featuring a donor at the bottom, recovered from Mogao Cave 17. It is significant that Cakravarticintāmaṇi appears on the opposite side of Amoghapāśa, suggesting that both are the attendant bodhisattvas of Sahasrabhuja Avalokiteśvara.

Figure 14.

A silk painting of Thousand-Armed Avalokiteśvara (Sahasrabhuja) of the ‘Dabei Gathering’ from Dunhuang, ca. 10th century CE, MG 17659.

The depiction of Sahasrabhuja Avalokiteśvara, along with the retinue of deities, has its source in the Dabeixin Dhāraṇī, which is a portion of the Qianshou Qianyan Guanshiyin Pusa guangda yuanman wuai dabeixin tuoloni jing 千手千眼觀世音菩薩廣大圓満無礙大悲心陀羅尼經 (hereafter Qianshou jing), a part of the Dunhuang manuscripts P. 3352,17 and also the Nīlakaṇṭhasūtra.18 The chanting of this scripture in praise of Sahasrabhuja Avalokiteśvara occurs during a gathering called the ‘Dabei Gathering’.19 Notably, the painting at the Guimet contains inscriptions at the back, listing the names of the attendant deities summoned to offer protection and assistance. Many of these deities are also referenced in the aforesaid dhāraṇī, which recounts how Sahasrabhuja sends ‘benevolent spirits, the Nāga Kings and Guhyapāda Vajraḥ’ and a plethora of other deities to safeguard those who gather for the chant of the Dabeixin Dhāraṇī, which was preceded by a litany invoking these deities.20 However, Cintāmaṇicakra and Amoghapāśa are not mentioned in the list (Hamada 2021, p. 164).21

7. Japan

The cult of Cakravarticintāmaṇi, known in Japan as Cintāmaṇicakra and Nyoirin Kannon, remains both prevalent and thriving today. He is one of the most popular deities in a group of six Kannons worshipped in Japan. It is generally believed that Kūkai, the founder of the Shingon sect, who went to China in 804 CE to study with Huiguo in Chang’an, was instrumental in popularising the deity’s cult by circulating additional texts and establishing images. Thus, most scholars, including Dorothy Wong (2008), propose that the cult of Cintāmaṇicakra arrived in Japan only in the 9th century CE. However, as noted earlier, textual evidence suggests that the cult might have existed in Japan prior to Kūkai’s return. It is also believed that Kūkai, upon his return, brought back many artefacts, including paintings and sūtras, some of which are now national treasures of Japan, preserved at the Tōji Temple in Kyoto (Pal 2021). Consequently, the worship and images of Cintāmaṇicakra are closely associated with Shingon-affiliated temples, particularly the Sanbō-in, Kajūji, and Saidaiji branches (Faure 2015, p. 235).

Images of Cintāmaṇicakra in Japan are widespread and come in various sizes and materials, such as bronze, wood, and paintings. The iconography often includes both the cintāmaṇi (wish-fulfilling jewel) and the cakra (wheel). During the Kamakura period (1185–1333 CE), at least six variations of Cintāmaṇicakra were documented, namely Shō Kannon (Ārya Avalokiteśvara), Senu Kannon (Sahasrabhuja Avalokiteśvara), Batō Kannon (Hayagrīva Avalokiteśvara), Jūchimen Kannon (Ekādaśamukha Avalokiteśvara), Juntei Kannon (Cuṇḍī Avalokiteśvara), Fukūkenjaku Kannon (Amoghapāśa Avalokiteśvara), and Nyoirin Kannon (Cintāmaṇicakra Avalokiteśvara) (Fowler 2016, pp. 17–28). These include depictions of the deity seated in mahārājalīlāsana, lalitāsana, and padmāsana poses, or standing on a lotus pedestal or the back of a dwarfish figure. The deity is shown with two, six, eight, or twelve arms and depicted either alone or with other deities in maṇḍalas (Pal 2021).

The Ishiyamadera Temple arguably houses some of the oldest wooden statues of Cintāmaṇicakra in Japan, as records show that the worship of the deity, referred to exclusively as Nyoirin Kannon, has been practised there since the 8th century CE. Most of these images, dated to the 9th century CE, have two arms and represent the earlier form of the bodhisattva (Fowler 2005, p. 122; 2016, p. 28). Similarly, Pal (2021) observes that most restored images at Ishiyamadera, which was destroyed by fire in 1048 CE, also possess two arms: the left hand holds a lotus, while the right hand displays the vyākhyāṇamudrā (also known as vitarkamudrā or the “teaching gesture”). These images likely predate the arrival of the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra or its Chinese translation, the Guanzizai ruyilun pusa yujia fayao, which was later translated into Japanese, as previously mentioned. The main image of the bodhisattva enshrined at Ishiyamadera is said to have replaced the original, which was also destroyed in the fire. This new image is a secret image (hibutsu 秘仏), usually displayed to the public only once every thirty-three years (Fowler 2005, p. 122).

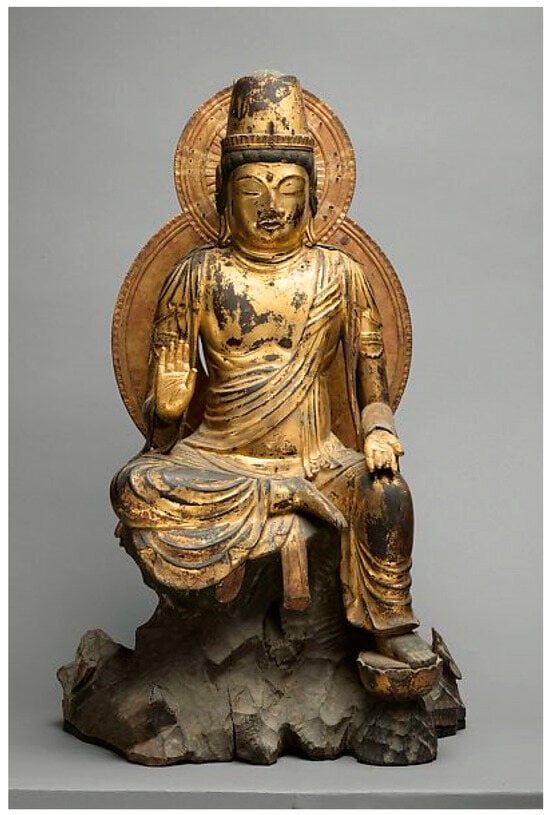

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has a two-armed wooden image labelled as “Nyoirin Kannon/Cintāmaṇicakra” (Figure 15) in its collection, which may be one of the restored images mentioned by Pal (2021). The bodhisattva is seated in the lalitāsana pose on Mount Potalaka, surrounded by a mandorla, with the right hand showing the abhayamudrā and the left hand showing the varadamudrā. The hairstyle does not feature the typical jaṭāmakuṭa with an image of Amitābha at the centre, as seen in most examples from India, Southeast Asia, and China. Instead, it appears that the bodhisattva is wearing a kirītamakuṭa, a canonical headdress typically associated with Viṣṇu. Since the two-armed form is an earlier representation of the bodhisattva, it is plausible that this iconography follows the description in the Nyoirin daranikyō 如意輪陀羅尼経 (Skt. Cintāmaṇicakradhāraṇīsūtra), one of the earliest texts describing the deity as emitting a great light and sitting on a lotus. The “great light” could symbolise the Dharmakāya or the cintāmaṇi itself.

Figure 15.

Wooden sculpture of the two-armed Cintāmaṇicakra, originally at the Ishiyamadera Temple, 10th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art. SL.7.2019.19.2a–f.

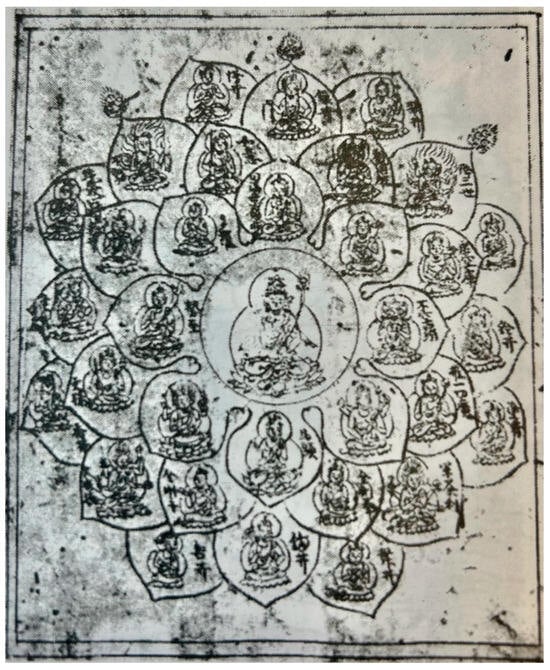

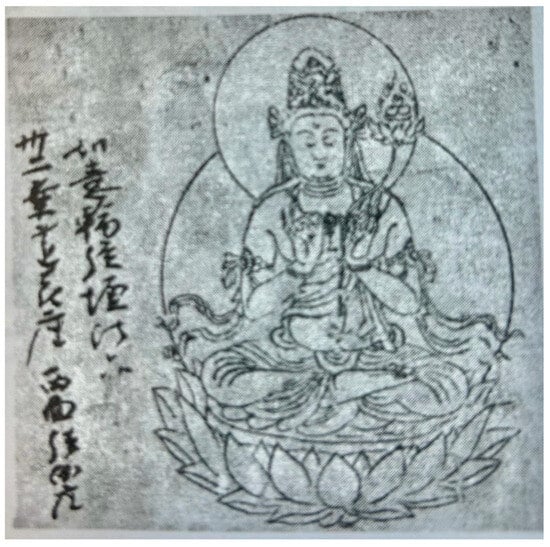

Furthermore, a sketch of a maṇḍala from the Kakuzen-shō (Figure 16) depicts a two-armed Avalokiteśvara at the bindu, suggesting that the deity occupies a central position within the maṇḍala. He is seated on a lotus pedestal with a lotus stalk rising above his left shoulder, and his hands are positioned at chest level. However, the exact mudrā being displayed is unclear. The identity of this bodhisattva becomes apparent in another sketch (Figure 17), which serves as a transcription of the same maṇḍala, where the name “Cintāmaṇicakra Ārya Avalokiteśvara” 如意輪聖観音, is written in Kanji at the centre. This transcription sketch is part of a maṇḍala collection (TZ. 99.17-18) compiled by the Shingon monk Genshō (1146–1222 CE). Additionally, several other similar maṇḍala sketches found in the Zuzō-shō 図像抄 (TZ.86.67) and Shika-shō-zuzō 如意輪観音(TZ.89.59-61) also portray a two-armed bodhisattva. (See Chandra 1999, pp. 810–11). These depictions show the bodhisattva performing a mudrā that closely resembles the dharmacakramudrā or a variation thereof, such as the dharmarājamudrā with both hands. Another sketch (TZ.319.40; Figure 18) depicts a two-armed bodhisattva seated independently on a lotus pedestal, and not in a maṇḍala. The bodhisattva is accompanied by a lotus stalk, and a flaming lotus flower with three orb-like buds is positioned above the left shoulder. The two hands are depicted possibly performing the dharmacakramudrā. A Kanji inscription accompanying the image identifies the figure as “Nyoirin Kannon” 如意輪観音, further confirming the deity’s identity as Cintāmaṇicakra.

Figure 16.

Maṇḍala of Two-Armed Cintāmaṇicakra in the Kakuzen-shō (TZ. 102.169), 12th century, from Dictionary of Buddhist Iconography Volume 3 by Chandra (1999, p. 810).

Figure 17.

Transcription of Cintāmaṇicakra Maṇḍala in Collection of Maṇḍalas by Genshō (TZ.99.17-18), 12th century, from Dictionary of Buddhist Iconography Volume 3 by Chandra (1999, p. 810).

Figure 18.

Sketch of the Two-Armed Cintāmaṇicakra in Zuzō-shō (TZ.319.40), 12th century, from Dictionary of Buddhist Iconography Volume 3 by Chandra (1999, p. 811).

It is worth noting that the two-armed images in these sketches somewhat resemble the two-armed depiction of Cintāmaṇicakra from China, housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum and the printed dhāraṇī from Dunhuang. As seen in the Nelson-Atkins image, the dharmacakramudrā may signify the cakra itself. Saunders (2018) observes that this mudrā known in Japanese as tembōrin-in embodies the symbol of the Dharmacakra—the Wheel of Law—which the Buddha set in motion during his first sermon at the Deer Park. Moreover, the circular bulbs, which resemble flaming lotus buds, could also be interpreted as a cintāmaṇi, as it is common, especially in Himalayan art and Javanese art, for the primary attribute of a bodhisattva or deity to be placed on a lotus flower with a stem extending above the left shoulder. However, this feature is absent in both the Nelson-Atkins image and the printed dhāraṇī/talisman from Dunhuang. It is also worth noting that the ‘flaming cintāmaṇi’ motifs appear at the periphery of the sketches of the Cintāmaṇicakra Maṇḍala (three at the top) and in its transcription (eight at the cardinal directions) from the Kakuzen-shō described above, further reaffirming their significance as a major attribute of the bodhisattva.

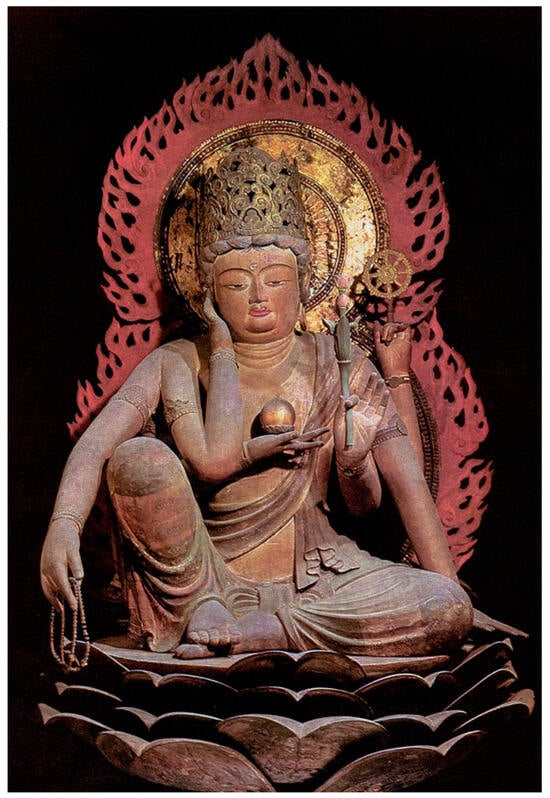

However, the most common iconography of Cintāmaṇicakra in Japan is the six-armed form. These representations are nearly identical to the Chinese six-armed images, such as the Sotheby’s bronze, with minor variations in the placement of attributes, sometimes held in different hands. Two of the oldest six-armed images in Japan are believed to be located at Murōji Temple and Kanshinji Temple, both of which are thought to have been consecrated by Kūkai.22 These examples likely served as prototypes for other six-armed depictions of the bodhisattva in sculpture and painting. Notably, the iconography of the images at Murōji (Figure 19) and Kanshinji (Figure 20) aligns with the descriptions in the Kanjizai nyoirin bosatsu yuga hōyō and the Guanzizai ruyilun pusa yujia fayao, the Japanese and Chinese translations of the Sanskrit Cakravarticintāmanidhāraṇīsūtra. The English translations by Fowler (2005, p. 121) and Sinclair (2016, p. 32) are also nearly identical, confirming that the six-armed Cintāmaṇicakra images in Japan and the six-armed Cakravarticintāmaṇi images in Java, such as Raffles’ sketch and the bronze in the Ashmolean Museum, share the same textual source. However, these images stem from different translations, also with some variations in the attributes, sometimes held in different hands.

Figure 19.

Wooden statue of the six-armed Cintāmaṇicakra at the Murōji Temple, 9th century CE.

Figure 20.

Wooden statue of the six-armed Cintāmaṇicakra at the Kanshinji Temple, 9th century CE.

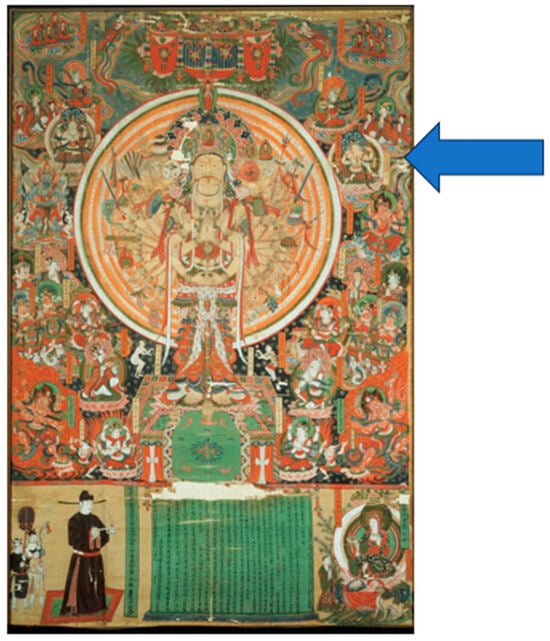

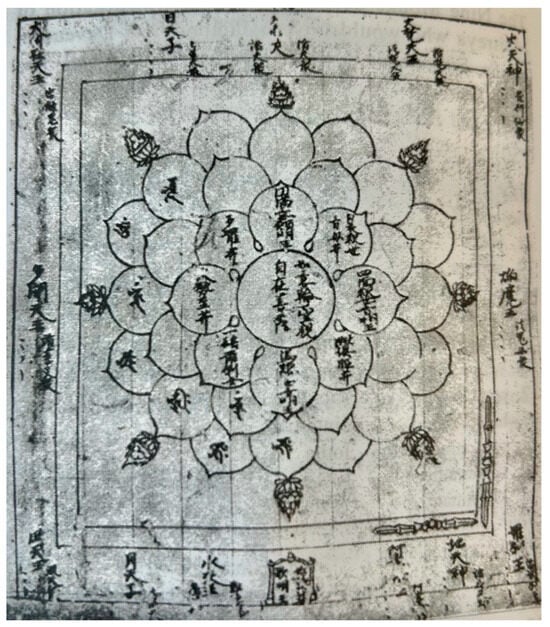

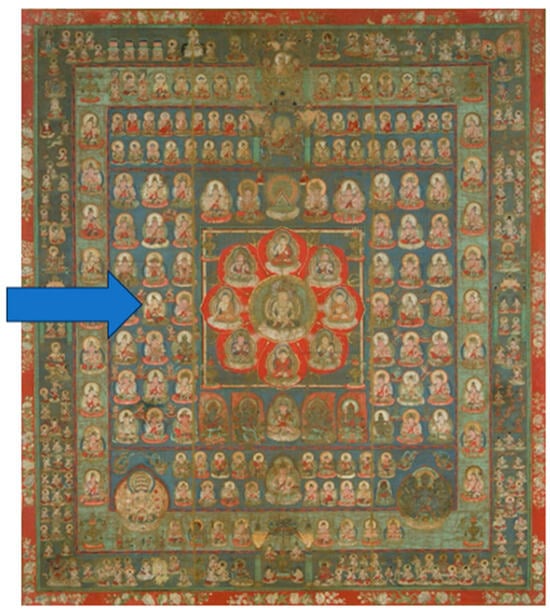

The six-armed Cintāmaṇicakra, seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose, is also depicted among the deities in the visual representation of the Mahākaruṇāgarbhadhātumaṇḍala (Womb Maṇḍala; Figure 21). Cintāmaṇicakra is part of the group of twenty-one bodhisattvas (fourth down from the second line) of the Padmakula (Lotus Family), positioned to the right of Mahāvairocana at the centre, who is surrounded by the eight Tathāgatas. On the opposite side, the twenty-one bodhisattvas of the Vajra family are positioned.

Figure 21.

Silk painting of the Mahākaruṇāgarbhadhātu (Womb) Maṇḍala, 9th century, Tō-ji, Kyōto.

The Daihōkō hakurokukaku zenjū himitsu darani kyō 広大宝楼閣善住秘密陀羅尼経 (T. 1005A and 1006) and the Ichiji bucchō rin’oh nenju giki 一字頂輪王念誦儀軌 (T. 954A and B) also provide visualisations of Cintāmaṇicakra with six arms and other common attributes. The latter, however, specifies a unique visualisation where bodhisattvas emerge from a maṇi, and their teachings culminate in the cakra. As the visualisation progresses, the sādhaka (practitioner) is instructed to imagine the maṇi gradually transforming into the six-armed form of Cintāmaṇicakra, which is visualised as being within the body of the sādhaka (Shinohara 2014, p. 183). This visualisation, therefore, affirms that the cintāmaṇi motif is synonymous with the physical form of the deity, in other words, representing the subtle body and the gross body.

In summary, the six-armed images of Cintāmaṇicakra in Japan uniformly follow the following iconographical programme:

- Mahārājalīlāsana pose;

- The upper right hand is relaxed beside the body and holds a rosary;

- The middle right hand displays a pensive gesture, touching the right cheek;

- The lower right hand holds the cintāmaṇi at chest level;

- The upper left arm rests on the side of the body, supporting its weight;

- The middle left hand holds the cakra;

- The lower left hand holds the lotus stem with the vitarkamudrā;

- Wearing a crown, seated on a multi-layered lotus base, and surrounded with a double mandorla with the flame motif.23

Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the feminisation of Cintāmaṇicakra in Japan began around the mid-9th century CE, as suggested by the Kakuzen-shō, which describes the deity as female. However, 9th-century figures remain androgynous, resembling Chinese depictions. This is likely because these sculptures were created before the Kakuzen-shō became influential, replacing earlier interpretations. As time progressed, representations of the bodhisattva, especially the six-armed images, gradually became more feminine or androgynous, displaying greater grace and poise compared to the earlier two-armed images in Japan, and even more so than those from the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Nevertheless, later paintings reveal that while the overall characteristics of the bodhisattva became more feminine, traces of male characteristics persisted in some examples. For instance, the bodhisattva’s chest is often partially covered, and sometimes a moustache is depicted on the face, as seen in a painting from the Nara National Museum dated to the 12th century CE (Figure 22).

Figure 22.

Silk painting of Cintāmaṇicakra, Kamakura Period, Nara National Museum.

In addition to the two-, four-, and six-armed forms, the Zuzō-shō collection contains sketches of an eight- (TZ.86.62) and twelve-armed (TZ.86.64) Cintāmaṇicakra. These forms are unique because the bodhisattva has two of the upper hands joined together in the añjalīmudrā above the head, while the two lower arms are sometimes together, either performing the cintāmaṇimudrā or holding other attributes (Chandra 1999, pp. 827–28). Nevertheless, the cintāmaṇi motif is present in all of the images. Since there is no evidence of the eight- and twelve-armed forms found in other regions, the form may have developed and been exclusively worshipped in Japan, potentially following different textual sources not mentioned in this study. Finally, the Kōmyō shingon 光明真言, or “Mantra of Light”, one of the most significant mantras in the Shingon School, originated in India and was transmitted to China by Bodhiruci and Amoghavajra, eventually spreading to Korea and Japan. This mantra is closely associated with Cintāmaṇicakra and is used for healing, purification, and the expiation of sins for both the dying and the deceased (Unno 2011, p. 863). The mantra reads as follows: ‘Praise be to the flawless, all-pervasive illumination of the great mudrā (the Seal of the Buddha), turn over and set in motion the jewel, lotus, and radiant light’ (translation by Unno 2011, p. 863).

The phrase ‘turn over and set in motion’ can be understood as symbolising the movement of the cakra, while the ‘jewel, lotus, and radiant light’ may represent the cintāmaṇi itself. A common ritual involves charging sand with the power of this mantra and sprinkling it on corpses or in charnel grounds to help the spirits of the deceased attain higher rebirths. This practice is in line with the contemporary custom of erecting images of Cintāmaṇicakra in cemeteries.24 Thus, Cintāmaṇicakra becomes synonymous with the formless, radiant light of Mahāvairocana, represented by the cintāmaṇi motif seen in the material culture.

8. Iconographical Discussion

To address the issue of iconography, we can draw upon the well-established depictions of Cakravarticintāmaṇi in the regions highlighted in this study. In Java, this is found in Raffles’ sketch of a lost bronze statue and the bronze housed at the Ashmolean Museum, both of which largely correspond to the iconographic descriptions outlined in the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra. Similarly, images of Cintāmaṇicakra in China and Japan align with textual evidence from translations, as well as contemporary worship practices. In these depictions, the bodhisattva typically appears with six arms, holding a cintāmaṇi and a cakra, seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose, and displaying the pensive gesture, although there are some variations in other attributes.

Based on these features, I propose that the two-, four-, and six-armed forms found in Southeast Asia, seated in the mahārājalīlāsana pose, displaying the pensive gesture and with one hand at the chest and holding a cintāmaṇi in that hand or another outstretched hand, and either seen with or without a cakra, likely represent the same bodhisattva. Additionally, textual evidence regarding Bianhong’s attainment of the siddhis of Cakravarticintāmaṇi suggests the prevalence of this bodhisattva’s cult in the region.

It is plausible that the iconography of Cakravarticintāmaṇi in India and Southeast Asia during this period initially only has the cintāmaṇi, symbolising the wish-fulfilling and the boundless blessings aspect, as the primary attribute. Over time, the cakra, representing the concept of ‘turning’ or movement and sovereignty, likely became an additional attribute. This evolution may have been influenced by the concept of the cakravartin (“universal ruler”), who is often depicted with a cakra. Consequently, the cakra became another significant symbol associated with the bodhisattva, reinforcing his role as the protector of kingship.

The differences in the variations of attributes and the number of arms in the bodhisattva’s iconography may suggest that the Cakravarticintāmaṇi was initially conceptualised as a dhāraṇī deity, as demonstrated by Cruijsen et al. (2014) in the case of Mahāpratisarā. Similarly, this further implies that the bodhisattva’s iconography likely drew upon multiple textual sources for the development of its visual representation.

Furthermore, as Robert L. Brown (1995) notes, the development of Indian deities in Southeast Asia differs from their evolution in India, as Southeast Asian artists often reinterpreted Indian art in ways that reflected their indigenous beliefs and local traditions. Moreover, the language, translations, and interpretation of texts, along with their regional variants, played a significant role in producing iconographical variations across different regions and ateliers.

This research also corroborates the presence of two-armed Cintāmaṇicakra forms, holding neither a cintāmaṇi nor a cakra, and possibly performing the dharmacakramudrā in textual sources, particularly in the Cintāmaṇicakradhāraṇīsūtra (Jp. Nyoirin daranikyō), as well as in sketches found in the Kākuzen-shō and in the Zuzō-shō, Shika-shō-zuzō, and the maṇḍala collections by Genshō. The dharmacakramudrā may be interpreted to symbolise the cakra itself, and the whole ethereal body of the bodhisattva represents the cintāmaṇi.

Regarding the two-armed Avalokiteśvara at Candi Mendut, it is at present impossible to positively identify the statue as Cakravarticintāmaṇi. However, if we consider Chandra (1980)’s proposal that Candi Mendut represents the Mahākaruṇāgarbhadhātumaṇḍala, then the stone image in question—certainly a bodhisattva of the Padmakula—could represent all twenty-one forms of Avalokiteśvara, including Cakravarticintāmaṇi, whose presence is confirmed in depictions of the same maṇḍala.

Finally, it must be understood that the cintāmaṇi is essentially a concept involving an esoteric process, in which an orb of light symbolising the Dharmakāya—the unmanifested form of the deity—serves as the focal point of visualisation. From this initial point, deities can be visualised and manifested internally by the practitioner. Unlike Hindu texts on the Śilpaśāstra, which provide specific guidelines for crafting images of worship, the dhāraṇīs instruct the sādhaka (practitioner) on how to visualise and meditate, sometimes leaving the details, such as the positioning of attributes and other nuances, to the practitioner’s imagination. This creative freedom directly influences artistic representations, often leading to the establishment of new iconographic standards or traditions. The artist’s own imagination and experience also play a significant role, leading to variations in attributes, postures, expressions, and other subtle elements. Therefore, the context in which iconography is produced must be fully considered, rather than relying solely on art historical classifications alone.

9. Conclusions

The emergence and spread of the Cakravarticintāmaṇi cult along the Maritime Silk Routes during the 8th and 9th centuries underscore the interconnectedness of religious practices and visual culture across India, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. Variations in these representations arose from diverse textual traditions among different Buddhist schools and sects, the influence of local customs, and the artistic freedom exercised in creating such images. Known by different names in various regions, the bodhisattva’s form underwent significant iconographic and ritualistic adaptations as it crossed cultural and geographical boundaries. Originating in India as Cakravarticintāmaṇi, the deity’s form evolved in Southeast Asian and further developed in China and reached its apex in Japan as Cintāmaṇicakra. Each region developed its own distinct style, with variations in the number of hands, attributes, postures and gestures. Incorporating this esoteric Avalokiteśvara into royal and state ceremonies highlights its political and spiritual significance, particularly in ensuring divine protection and sovereignty. The enduring legacy of Cintāmaṇicakra as a revered deity in Japan exemplifies the lasting impact of early trans-regional exchanges and the adaptability of Buddhist iconography to local contexts.

In the course of this study, it became evident that the transmission of the Cakravarticintāmaṇi is remarkably expansive, with the cintāmaṇi motif playing a significant role imbued with profound philosophical, spiritual, and political symbolism. Besides the Maritime Silk Routes, the dissemination of texts and iconography associated with this bodhisattva traversed the overland Silk Roads, too. Further research focusing on the material culture along these routes, particularly from India to the Himalayas, Nepal, and Tibet, as well as overland connections to Turfan and Dunhuang and further into Mongolia, could illuminate its spread and influence. Similarly, the cintāmaṇi motif, in association with the iconography of bodhisattvas and buddhas, is evident in Khmer and Cham art and, as observed in clay plaques, extended as far as Bali. Future investigations in this area will further reveal the extent of the mediaeval Buddhist network through the study of this form of the bodhisattva and his wish-fulfilling gem.

Funding

This research and its publication have been partly supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR), project MANTRA—Maritime Asian Networks of Buddhist Tantra (ANR-22-CE27-015), coordinated by Andrea Acri (EPHE, PSL University, Paris) from 2023 to 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I extend my gratitude to the guest editors, Andrea Acri and Francesco Bianchini, for their support throughout this research. I am also deeply thankful to Nobuyuki (Shinko) Suzuki, a Buddhist priest ordained in the Koyasan Shingon tradition of Japanese Buddhism, for sharing his invaluable insights into the practice of Cintāmaṇicakra in Japan and its textual sources within the Japanese context.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The expressions “Silk Roads” or “Silk Routes” have been the subject of considerable scholarly debate. Firstly, silk was not the sole commodity traded along these networks; consequently, some researchers have opted for alternative terms such as “Spice Routes”. Moreover, as Khodadad Rezakhani (2010) argues, the notion of the “Silk Roads” represents a constructed, continuous concept that may not accurately reflect the actual historical trade networks. Rezakhani further suggests that the term was coined by Europeans, reflecting a romanticised, Eurocentric perspective rather than the realities of these routes. Despite these critiques, the term “Silk Roads” remains widely used, as no academically accepted alternative has emerged to encapsulate the extensive movements of people, goods, and ideas across land and sea between the continents. Therefore, this study employs the term for clarity, while encouraging readers to approach it as a conceptual framework rather than a literal designation of specific routes connecting distinct points. |

| 2 | The term “esoteric teaching” has often been used to denote what a particular writer regards as superior within the tradition. However, it was only in the 10th century that the term emerged as an exegetical category explicitly contrasting “esoteric teaching” with “exoteric teaching” to define a specific lineage, school, or tradition—comparable to the Shingon tradition in Japan or the Vajrayāna sects in Tibet (Orzech 2006, p. 44). Proffitt (2023) further argues that “Esoteric Buddhism” can be taken as a synonym for Mahayana Buddhism itself in particular contexts, where it takes a polemical rather than descriptive function. |

| 3 | Although the original Sanskrit text is no longer extant, the term Cakravarticintāmaṇi has been identified as the original Sanskrit name based on reconstructions from Chinese translations of various sūtras associated with this form of the bodhisattva. This term corresponds to the Chinese name “Ruyilun” and, as noted by Sinclair (2016, pp. 31–2; see note 11), supersedes the use of Cintāmaṇicakra in Japan. |

| 4 | Bianhong’s homeland is said to be Helin or equivalent to Kaliṅga in Sanskrit, which is identified to be an island in the Malay Archipelago, probably Java. See Sinclair (2016, p. 31). |

| 5 | The text also prescribes the numbers of recitation of the dhāraṇī of different classes of people: a king should recite 1080 times, a queen or a royal concubine, 900; a prince, 800; a princess, 700; a minister, 600; a Brahmin, 500; a kṣatriya, 400; a vaiśya, 300; a śūdra, 200; a monk, 108; a layman, 106; a laywoman, 103; a boy, 100; and a girl, 90. This demonstrates that the worship of Cintāmaṇicakra was practised by all members of the society. See Yu (2001, pp. 70–1). |

| 6 | In fact, the etymologies of the deity’s two foremost attributes, the cintāmaṇi and cakra, are often linked to kingship. The cintāmaṇi originates from the aṣṭamaṅgala, or the eight auspicious objects in both Hinduism and Buddhism, while the cakra, the most important weapon of Viṣṇu and a symbol of royal authority, became a representation of the teachings and the spread of the Dharma in Buddhism. |

| 7 | See Giebel (2012), for the complete list of texts. |

| 8 | It is noteworthy that in many Sanskrit texts on kingship, the “jewel woman” is one of the seven jewels (saptaratna) that the cakravartin should possess. The Dīrghāgamasūtra is more specific, listing a wheel, chariot, precious stones, consort, horses, and elephants. It details the golden wheel, white elephant, dark blue horse, celestial jewel, jewel woman, merchant–artisan, and military commander. See Ruppert (2000, p. 206). |

| 9 | I suspect the sūtra to be the Japanese version of the Cakravarticintāmaṇidhāraṇīsūtra because the translation closely resembles Sinclar’s translation quoted in this article, and also because Pal included some Japanese terminology in his article. |

| 10 | The cintāmaṇi is also one of Kṣitigarbha’s principal attributes, alongside the khakkhara (monastic staff), which, among other purposes, serves to guide the spirits of unborn children to higher realms. |