1. Introduction

Mental health disorders have become a global public health priority, affecting an estimated one in eight individuals during their lifetime, according to the

World Health Organization (

2025). As society searches for effective, culturally competent solutions, there is increased attention directed towards the role of religion and spirituality in mental health care (

Koenig 2012;

Kanu and Nosike 2025;

Vieten et al. 2023). Religion has been, throughout history, a central element in how individuals and societies understand suffering, healing, and the human condition overall (

Koenig 2012;

Park 2005;

VanderWeele 2017). Over the centuries, it has shaped not only spiritual life but also approaches to mental distress, often providing comfort, a sense of purpose, and community support. However, its impact is not always a positive one, and while religious beliefs can help, they can also have a negative impact by contributing to feelings of guilt, fear, or shame (

Martínez de Pisón 2023;

Moroń et al. 2022;

Pastwa-Wojciechowska et al. 2021).

Because adhering to religious beliefs provides believers with a sense of purpose, those who follow them often report higher levels of satisfaction with their life and overall well-being (

Garssen et al. 2020;

Mancuso and Lorona 2023;

VanderWeele 2017). Religion can considerably improve mental health by offering existential answers and a structured framework for interpreting life’s obstacles (

Garssen et al. 2020;

Mancuso and Lorona 2023). Religious concepts and teachings provide a defined set of ideals and goals that one can work towards, which give life a deep meaning and direction for many people. In addition to that, religious beliefs and rituals can help people interpret personal suffering and hardship within a bigger, more meaningful framework. When individuals view hardships through the lens of their faith, seeing purpose, growth or divine reasoning, they tend to cope more effectively (

Koenig 2012;

Park 2005;

VanderWeele 2017;

Zaidi 2018). In a study of 169 bereaved college students who had experienced a significant personal loss,

Park (

2005) found that those who could reinterpret their sad experience through religious meaning-making reported better emotional adjustment than those who could not.

Considerable social support is given by religious communities; in turn this support is strongly correlated with improved mental health outcomes. Belonging to a religious organization and engaging in religious group activities can promote social integration, reduce feelings of isolation and offer emotional support (

Hefti 2011;

Koenig 2012;

Krok 2014;

VanderWeele 2017). Beyond the symbolic value of shared beliefs, what proves especially beneficial is the actual support individuals receive from their faith communities. Emotional encouragement, fellowship and practical help received within these groups have been linked to fewer physical complaints, lower rates of depression and improved social functioning (

Krok 2014;

VanderWeele 2017).

Another meaningful, positive contribution of religion lies in the impact of religious practices-such as prayer, meditation, scripture reading, and participation in communal rituals that have been associated with improved mental health outcome (

Boelens et al. 2009;

Goyal et al. 2014;

Hefti 2011;

Koenig 2012). These activities are believed to reduce stress and anxiety by fostering emotional stability, a sense of inner peace, and spiritual connection. Studies have shown that prayer can significantly lower depression and anxiety, can increase optimism, promote emotional resilience and support daily well-being (

Boelens et al. 2009;

Hefti 2011;

VanderWeele 2017).

As for meditation, it holds a similarly important place across many religious traditions (

Goyal et al. 2014;

Koenig 2012;

Lucchetti and Vallada 2021;

VanderWeele 2017). Whether in the form of silent contemplation (Christianity), dhikr (Islam), scripture focused reflection (Christianity, Judaism), mantra chanting (Hinduism, Buddhism), meditation is designed to deepen spiritual connection and cultivate inner peace. Apart from its spiritual role, research consistently demonstrates its psychological benefits, in reductions in anxiety, depression and perceived stress (

Goyal et al. 2014;

Koenig 2012;

Lucchetti and Vallada 2021;

VanderWeele 2017).

In certain religious communities, mental illness may be interpreted as a lack of faith, a form of divine punishment or a sign of personal weakness (

Ciftci et al. 2012) Such perceptions can create stigma, which often acts as a significant barrier to seeking professional help, leading some individuals to delay or completely avoid necessary treatment (

Ciftci et al. 2012;

Nugent et al. 2021;

Kanu and Nosike 2025). Stigma can manifest both externally (from the community) and internally (self-stigma), both worsening emotional distress. Research has shown that religious stigma is negatively correlated with mental health service utilization, especially in conservative and fundamentalist contexts (

Ciftci et al. 2012).

Religious belief systems often support moral values and a sense of spiritual responsibility. But when these ideals are taken too strictly, they can lead to persistent and overwhelming guilt. There are studies that show that religious settings that strongly emphasize sin or moral imperfection can make feelings of guilt and shame more intense. (

Martínez de Pisón 2023;

Moroń et al. 2022;

Pastwa-Wojciechowska et al. 2021;

Sawai et al. 2017). Also, this feeling of guilt can be intensified by the realization that they cannot meet the expectations or live up to the ideals set by their faith. When this feelings of guilt become chronic, especially in environments that do not encourage forgiveness or emotional healing, it is linked to higher anxiety and depression rates and lower self-esteem (

Martínez de Pisón 2023;

Moroń et al. 2022).

When God is perceived as a punitive or condemning figure, personal crises such as illness, loss or failure may be interpreted through the lens of divine punishment. This perception of a punitive God can also amplify anxiety and depressive symptoms, as the fear of eternal or earthly retribution becomes a persistent psychological burden (

Martínez de Pisón 2023;

Moroń et al. 2022;

Upenieks and Schieman 2021;

Hefti 2011).

Furthermore, the mental health impact may be aggravated by social exclusion and isolation, brought on by discriminatory views within religious communities (

Ciftci et al. 2012). Members of the religious community may reject or exclude those who struggle with mental health issues, which can result in a lack of social support and increased feelings of hopelessness and loneliness (

Ciftci et al. 2012;

Krok 2014;

Nugent et al. 2021)

The aim of this study is to explore medical students’ perceptions of the impact of religion on their mental health, offering a detailed analysis of how they view both the potential benefits and challenges that religious belief and practice can bring to psychological well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey study designed to explore the relationship between religious beliefs and mental health outcomes. A structured questionnaire, specifically developed for this research, contained 16 items addressing demographic characteristics (age and gender), religious affiliation, conversion status, degree of religious practice and perceived importance of faith, feelings of guilt associated with non-observance of religious rules, personal experiences with mental health issues, attitudes toward psychiatric care and psychotherapy, the impact of life hardships on mental and spiritual well-being, the role of religion and spirituality as coping mechanisms, and perceptions of religion as a source of social connection or isolation.

The response options were structured as categorical variables. Age was grouped into four categories (<20, 20–25, 26–30, >30), and gender included female, male, or other. Religious affiliation options included Islam, Catholicism, Orthodoxy, Atheism, “I do not wish to disclose,” and “Other.” Questions on religiosity offered scales such as highly practicing, practicing, moderately practicing, not practicing. Although atheism is not a religion per se, it was included among the affiliation options to allow each participant to indicate a position within the broader spectrum of belief and non-belief. This ensured that all students could select a category corresponding to their worldview. Items on sensitive aspects such as guilt for not following religious rules, whether being “too religious” may cause mental health problems, or whether respondents had ever struggled with mental health, sought psychiatric help, or benefited from therapy, were answered with the options: yes, no, or I do not wish to answer. Questions about the influence of hardships allowed respondents to indicate whether these experiences brought them closer to or distanced them from religion. Coping strategies were measured through one-choice option (the most frequent one used) including exercising, resting, talking to family or friends, praying or putting faith in God, or none of the above. Finally, social perceptions of religion were assessed by asking whether religion brings people together or isolates them.

The questionnaire was created and administered using Google Forms and distributed online among international medical students enrolled at a medical university in Romania A total of 100 valid responses were collected. Completion of the survey required approximately 5–7 min, and participants could withdraw at any point prior to submission. No personally identifiable information was collected, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality throughout the research process.

Responses were exported into Microsoft Excel for initial organization and descriptive analysis. Frequencies and percentages were calculated to summarize demographic and categorical data. For inferential statistical analyses, GraphPad Prism version 10.5.0 (774) was employed. Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square tests were applied for 2 × 2 contingency tables, while the Chi-square test of independence was used for larger tables. All statistical analyses performed in this study are summarized in

Table 1. An alpha level (α) of 0.05 was adopted for all statistical tests, and

p-values below this threshold were considered statistically significant.

Participants were fully informed about the aims, scope, and academic purpose of the study before beginning the questionnaire. Electronic informed consent was obtained, and participation was entirely voluntary. The study was conducted anonymously in strict compliance with ethical principles of research on human subjects and data protection regulations. Ethical approval was granted by the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Center for Psychotherapy and Personal Development, Romania (Registration no. 81), which confirmed that the study met all ethical standards for scientific research.

3. Results

The following section presents the results of the questionnaire data and the analysis performed on them. Regarding Demographic Information, we can notice that the sample consisted of young individuals, the age group 20–29 years old comprising 89% of the total sample, 8% under 20 and 3% were above 30. Regarding gender distribution, the sample included 59% female and 41% male participants.

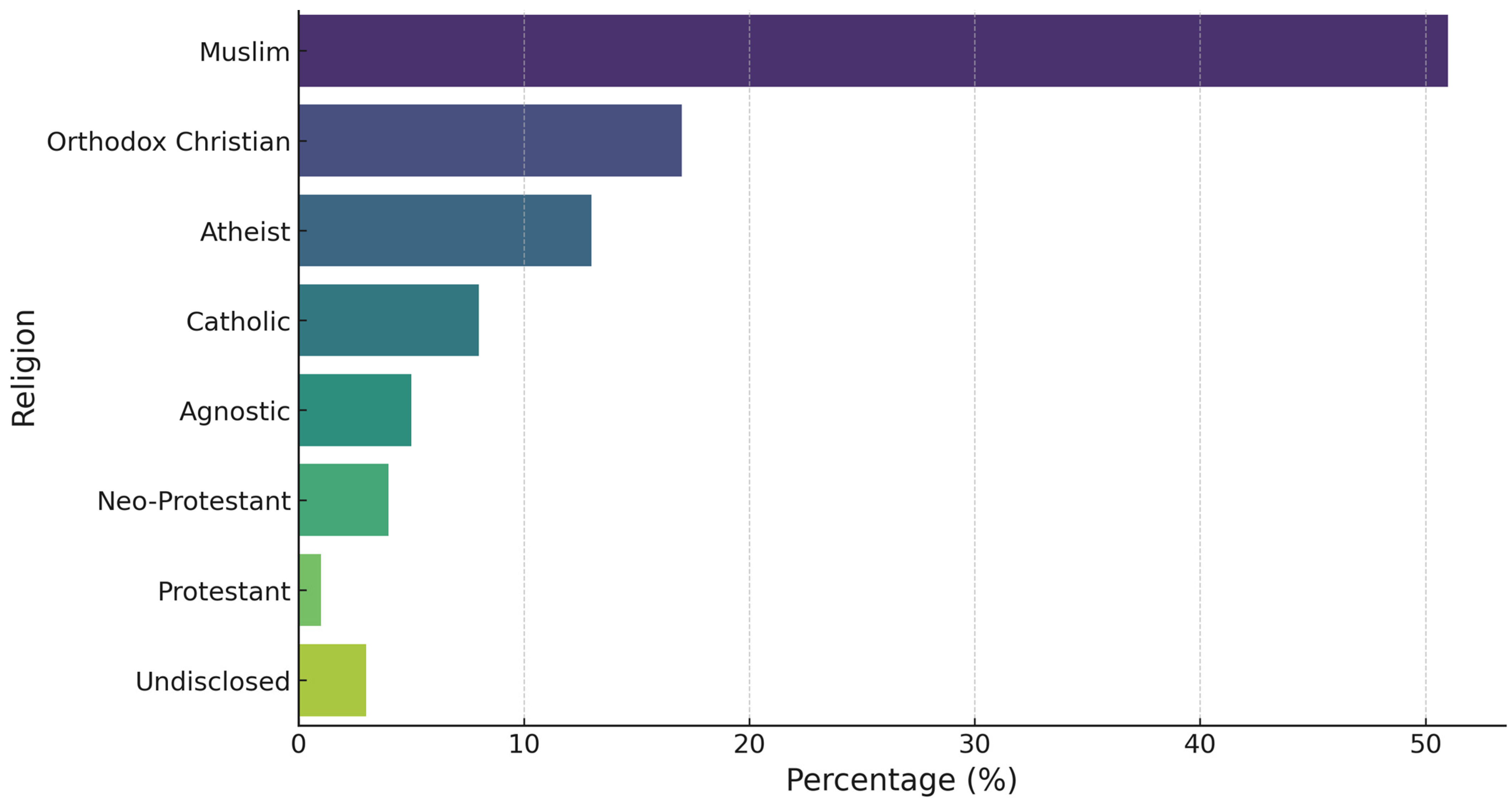

In response to religious affiliation, participants reported a diverse range of backgrounds, as shown in

Figure 1. The largest group identified as Muslims (51%), followed by Orthodox Christians (17%), Atheists (13%), Catholics (8%) Agnosticism (5%), Neo-Protestants (4%), Protestants (1%), and chose to not disclose their religion (3%). This variety allowed for a comparative analysis of how different religious identities relate to mental health perception and coping mechanisms.

The fourth question on the questionnaire, asked the participants to choose whether they were born into the Religion, chosen in the question prior or if they converted to this religion. 15% of the participants were converts, while the majority of participants were born with their religious beliefs (85%).

In the fifth question of the questionnaire participants were asked to self-assess the extent to which they consider themselves practicing in their religion. Based on their responses, they were put in four categories: 4—highly practicing, individuals who engage consistent in religious activities, participate in community worship, attend religious services, follow the rules of their religion, daily practices; 3—practicing, individuals actively participate in religious life, attend services, follow the rules, but less strictly than the previous category; 2—moderately practicing, individuals who occasionally engage in religious activates with moderate commitment to religious principals; 1—not practicing, individuals who identified as religiously affiliated, but report little or no engagement in religious practices. 19% responded with highly, 33% practicing, 19% moderately, 23% not practicing and 6% did not disclose.

A Chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the association between religion and level of religious practice. The association was statistically significant, χ2(21, N = 94) = 69.05, p < 0.001, indicating that the distribution of practice levels differed significantly across religious groups. Muslims reported higher levels of religious practice than those from other religious backgrounds.

When asked whether they frequently feel guilty for not adhering to their religion’s rules, 56% of participants responded affirmatively. Feelings of guilt were most commonly reported among Muslim and Neo-Protestant participants, while atheists and agnostics reported little to no such experiences.

A Chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the association between level of religious practice and feelings of guilt about not following religious rules. The association was statistically significant, χ2(3, N = 87) = 31.27, p < 0.001. Participants in the “Practicing” (86%) and “highly practicing” (83%) categories reported guilt more frequently than those in the “Not practicing” category (17%).

Next question was asked to identify whether the participants believed that being too religious could negatively impact mental health. Responses revealed a divided perception, 41% of the participants do believe that excessive religiosity could contribute to mental health burden, while 56% disagreed and 3% preferred not to answer.

A Chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the association between level of religious practice and the belief that “being too religious” can contribute to mental health problems. The association was statistically significant, χ2(3, N = 91) = 38.53, p < 0.001. Participants in the “Practicing” (91%) and “highly practicing” (79%) categories were more likely to respond “No” to the statement, whereas those in the “Moderately practicing” (72%) and “Not practicing” (82%) categories were more likely to respond “Yes.” These findings suggest that lower levels of religious practice are associated with a greater tendency to perceive high religiosity as potentially detrimental to mental health.

Three questions (8, 9, and 10) were designed to explore participant’s personal experiences with mental health and their view on seeking professional support.

In response to question 8, if they ever have struggled with their mental health, 64% have reported struggles at some point in their life, and 36% indicated no such experience. Despite the prevalence, question 9 revealed that only 32% had consulted a psychiatrist, and 68% have not.

A Chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the association between level of religious practice and self-reported struggles with mental health. The association was not statistically significant, χ2(3, N = 91) = 3.48, p = 0.324. These results suggest that, within this sample, the prevalence of reported mental health struggles did not differ significantly across practice levels.

Fisher’s Exact Test was conducted to examine the association between experiencing mental struggles and seeking professional psychiatric help. The association was statistically significant, p < 0.001, indicating, as expected, that participants who reported mental struggles were substantially more likely to seek professional help compared to those without reported struggles. However, it is notable that within this group, only 47% of participants who reported mental struggles had actually sought professional help, highlighting a considerable gap in help-seeking behavior. In addition, a Chi-square test of independence showed no statistically significant association between level of religious practice and seeking professional psychiatric help, χ2(3, N = 91) = 6.93, p = 0.074.

The question 10 whether they believed that psychotherapy is beneficial 97% responded affirmatively. This indicates a general openness to the concept of therapy, even among those who did not personally use it. The contrast between belief and behavior points to other possible obstacles such as stigma, cultural or religious norms, lack of access, personal hesitation, or the cost of services, which may be especially relevant for students.

A Chi-square test of independence was applied to examine the association between level of religious practice and belief that therapy is beneficial. The association was statistically significant, χ2(3, N = 94) = 7.97, p = 0.047, indicating that views on therapy differed slightly across practice levels. While nearly all participants agreed that therapy is beneficial (ranging from 81.8% to 100%), the “Practicing” group had a slightly lower proportion of affirmative responses compared to the other groups.

Question 11 to 14 aimed to explore whether participants used religion when going through hard times and whether they have used their religion as a psychological coping tool.

The majority of participants (76%) reported that they have experienced hardships that affected their mental health (question 11). The follow up question aimed to see if these hardships influenced their religious orientation and 66% stated that they felt drawn closer to their religion as a result, while 34% felt pushed away by it. Furthermore, question 13 asked if they ever sought refuge in their beliefs, and 76% of the respondents declared that they have, while 24% have not.

A series of Chi-square tests of independence were applied to examine the associations between level of religious practice and several coping variables. No statistically significant association was found between level of religious practice and reporting hardships that affected mental health, χ2(3, N = 94) = 2.28, p = 0.516, indicating that the proportion of participants reporting hardships was similar across practice levels.

A significant association was found between level of practice and the effect of hardships on religious beliefs, χ2(3, N = 74) = 17.55, p = 0.001. Descriptive analysis showed that the “highly practicing” and “Practicing” groups were more likely to report that hardships brought them closer to their religion, whereas the “Not practicing” group more frequently indicated that hardships drove them away from religion.

Finally, a significant association was also found between level of practice and seeking refuge in religious beliefs, χ2(3, N = 94) = 16.05, p = 0.001. Although the majority of participants in all categories reported seeking refuge (ranging from 52.2% to 94.7%), the proportion was notably lower among the “Not practicing” group compared to all other groups.

The next question aimed to evaluate participant’s perception of the social dimension of religion, whether they believe that religion serves to bring people together or isolate them from society. The vast majority, 83%, viewed religion as something that facilities social connection, while 17% perceived it as isolating.

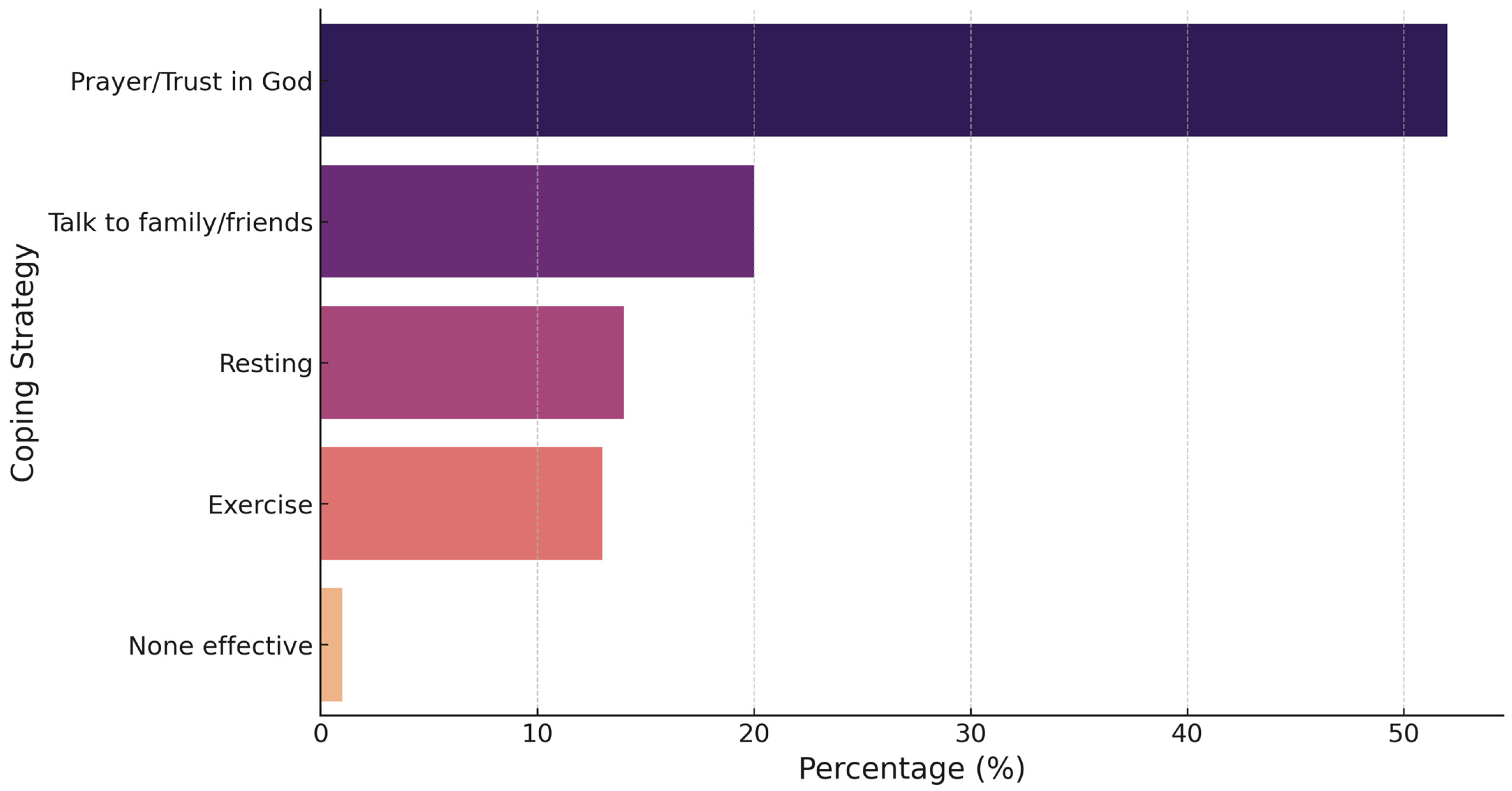

The final question explored which coping strategies were preferred by the participants during difficult moments with the aim to identify the role that religious plays compared to other common strategies. Results are shown in

Figure 2. We Observed That 52% indicated that prayer or having trust in God was their primary way of coping. Other approaches included talking to family or friends (20%), resting (14%), exercise (13%), and 1% reported that none of those strategies were effective.

4. Discussion

Regarding age distribution, the majority of respondents were between 20 and 29 years old. In the context of this study, age distribution can be explained by the fact that the sample consisted of medical students in English section, whose academic stage naturally falls within this range. The group is relatively uniform with respect to age and level of education. As for the gender distribution, in this particular sample, female respondents (59%) represented a larger proportion of the group compared to male respondents (41%). While this difference may be partly random, it is more plausibly explained by the demographic composition of medical schools, where female students are frequently more numerous than male students. In addition, many studies (

Koenig 2012;

VanderWeele 2017;

Vardy et al. 2022). show that women tend to report higher levels of religiosity than men and are more likely to incorporate faith into their coping strategy. A comprehensive cross-cultural investigation from 2022, involving 2002 individuals from 14 diverse societies supports this hypothesis (

Vardy et al. 2022).

The university years are widely recognized as stage marked by psychological and emotional demands, as students navigate academic pressure, personal development and life transitions (

Dyrbye et al. 2006;

Park 2005;

A’ini et al. 2025). The English section medical students are even more exposed to stress because they study abroad, far away from their family of origin. Young adults often seek effective strategies to manage these challenges and religion can serve as an important tool for many (

A’ini et al. 2025).

Religious affiliation (question 3) found that Islam was the most represented religion (51%); followed by Orthodoxy (17%) and Atheism (13%). This distribution differs from national statistic in Romania, where Orthodox Christianity is the predominant religion. The difference is explained by the composition of the study population, the research was conducted among international students, a large proportion come from predominantly Muslim religion, either from Muslim countries or second generation of emigrants in western European countries. This sample characteristic is important, as cultural background strongly influences both religious engagement and perceptions of mental health.

Analysis of religious conversion rates shows that only 15% of participants had converted to another faith, while 85% remained in the religion into which they were born. This distribution highlights the significant role of familial and cultural background in shaping religious identity. Being raised in a specific religious environment can lead to early internalization of beliefs and practices that continue to influence coping strategies, moral values and perception of mental health into adulthood (

Regnerus and Burdette 2006).

Regarding levels of religious practice, Muslim followers reported higher practice rates than other groups. This aligns with

Koenig and Al Shohaib (

2019) who highlights that Islam prescribes structured daily rituals—most notably the five daily prayers, fasting during Ramadan and regular Qur’anic recitation tends to reinforce religious engagement.

In contrast, religious practice among Orthodox and Catholic respondents, while also rooted in tradition, is generally less structured in terms of daily obligatory acts. Atheist participants naturally reported the lowest levels of practice, consistent with their lack of formal religious observance. Such differences in ritual structure and frequency likely explain the variance in reported practice levels across groups.

When examining feelings of guilt for not following religious rules, more than half of the participants reported experiencing frequent guilt, with higher rates among Muslim respondents compared to other groups. We also found a significant association between level of practice and feelings of guilt, with more practicing individuals tending to feel guilty more often. Participants in the “Practicing” and “highly practicing” categories reported guilt more frequently than those in the “Moderately practicing” and “Not practicing” groups.

Künkler et al. (

2020), analyzing Protestant adolescents and young adults using the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) and the Emotions toward God (EtG) inventory, found that guilt is the most prominent negative emotion toward God among highly religious individuals, significantly more so than among moderately religious peers.

In a study involving 250 Malaysian Muslim Youth, it was found a strong positive correlation between religiosity and feelings of shame and guilt. There is a stronger tendency to experience guilt when religious obligation is not fulfilled among individuals with higher levels of religiosity and moral consciousness (

Sawai et al. 2017).

For international students, including those in this study, the ability to maintain regular religious practices can be difficult because of contextual limitations. Access to mosques, designated prayer spaces, and community gatherings is often limited; some students may struggle to fulfill their entire religious obligation, which can sometimes lead to feelings of guilt or frustration.

Regarding the question 8, 41% of participants agreed that being “too religious” could contribute to mental health problems, while 56% disagreed. These differences reflect a boarder debate in the literature about the impact of religiosity intensity on psychological well-being. Research generally shows that moderate, balanced religiosity is associated with positive mental health outcomes, such as greater life satisfaction, lower depression, and stronger coping resources (

VanderWeele 2017). However, religious overcommitment or scrupulosity—characterized by excessive concern over sin, ritual correctness, or moral purity has been linked to induce anxiety, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and distress (

Moroń et al. 2022). The perception among participants that excessive religiosity may be harmful is consistent with these findings.

Regarding past mental health struggles 64% of participants reported experiencing such difficulties in their life, and 76% participants reported experiencing hardships that had an impact on their mental health (question 9 and 11). This is consistent with research showing that university students, especially those in high-pressure academic fields such as medicine, report higher rates of anxiety, depression, and stress compared to the general population (

Dyrbye et al. 2006). In addition, the students in this study were also exposed to other factors that could affect their mental health such as financial pressure, separation from family and the need to adjust to new cultural and social environments.

However, the next question revealed that 68% had never sought help from a professional, despite 97% (Question 10) believed that psychotherapy is beneficial.

These findings suggest that while awareness of the value of professional mental health services is high, likely influenced by their medical training, significant barriers: cultural, religious and stigma-related, continue to limit help-seeking among students.

The followed-up question was addressed to see the impact that these hardships had on their religion, and 66% reported feeling closer to their religion, while 34% felt distanced from it. These results reflect patterns seen in the literature: adversity can either strengthen religious commitment, serving as a source of meaning and resilience, or lead to spiritual struggle when hardships are interpreted as divine neglect or punishment (

Park 2005;

Ciftci et al. 2012;

Upenieks and Schieman 2021).

Furthermore, our findings indicate that participants with higher levels of religious practice were more likely to report feeling closer to their religion after experiencing hardships, whereas those with lower levels of practice more frequently reported feeling distanced. This suggests that the degree of religious engagement may influence whether adversity is perceived as an opportunity for spiritual growth or as a factor contributing to spiritual distancing.

The next two questions aimed to analyze if respondents sought refuge in their beliefs and if they helped in overcoming problems. The results showed that 76% of participants turned to religion as a coping resource, and 85% of the ones that did, reported that it helped them manage and overcome their challenges.

A significant association was found between level of practice and seeking refuge in religious beliefs, with most participants across all practice levels reporting that they turned to religion for support. However, this was less common among the “Not practicing” group compared to others.

These findings suggest that while religious coping is present at all levels of practice, individuals with higher levels of religious engagement are more likely to seek refuge and help in their faith during difficult times.

Although the data reflect personal perceptions rather than clinical outcomes, they offer valuable insight into the subjective usefulness of faith-based coping, particularly in times of hardship. These findings reinforce the idea that religion can function as an internal support system, offering comfort, stability, and meaning during adversity.

Regarding the role of religion as a tool for social interaction, question 15 examined whether students perceived religion as a way to connect with others or as a source of isolation. The results showed that the majority (83%) believed that religion brings people together.

This perception aligns with existing literature describing religion as a source of social capital, providing emotional support, shared values, and community networks. Even more, for international students, religious communities can serve as important points of integration, offering stability and a sense of belonging in unfamiliar cultural environments.

In contrast, the minority of respondents who reported feelings of isolation may reflect challenges faced by students belonging to minority faith groups in a mostly Christian country such Romania. Research suggests that in societies where the dominant religious culture differs from that of minority communities, these groups may face limited religious infrastructure, reduced social representation, or cultural misunderstandings (

Syahrivar et al. 2025).

The results indicated that students’ preferred coping strategies when facing personal difficulties were prayer and religious engagement (61%), followed by talking to family or friends (20%), resting more (14%), exercise (13%), and other (1%).

These findings align with prior research showing that in populations with moderate to high religiosity, religious coping such as prayer, reading sacred texts, or participating in religious community activities is often a primary and preferred strategy for managing stress and emotional challenges (

Koenig 2012;

Lucchetti and Vallada 2021).

Taken together, the results point to several major implications. First, religion stands out as a central coping mechanism for international medical students, offering meaning and resilience during a period characterized by high academic stress and personal transitions. Second, the data highlight the dual role of religiosity: while moderate religious engagement appears to be associated with psychological benefits, excessive religiosity can foster guilt and distress, reflecting the ambivalent impact of faith on mental health described in the literature on scrupulosity. Third, both cultural and gender dynamics shape the way students engage with religion and use it in coping, underlining the need for culturally sensitive approaches in psychological support for international students. Finally, the marked gap between the high prevalence of psychological difficulties and the low rate of professional help-seeking suggests persistent cultural and stigma-related barriers, as well as a tendency to view religion as an alternative or substitute for professional care.

The data confirm previous evidence that religion functions as a double-edged sword (

Koenig 2012), but they also contribute to new perspectives by exploring this phenomenon in a culturally diverse population of students studying abroad. In dialog with broader psychoanalytic and sociological approaches to belief (e.g.,

Domínguez-Morano 2018;

Lucchetti and Vallada 2021) our findings suggest that religious identity, whether expressed through adherence, practice, or rejection continues to shape emotional life and coping strategies into young adulthood.

Domínguez-Morano (

2018) emphasizes that religion can act both as a psychological resource, offering meaning, stability, and social belonging, and as a potential source of inner conflict, guilt, or neurotic tendencies when beliefs are internalized in an overly rigid or punitive way. From this perspective, religion represents an ambivalent force of mental health: capable of fostering resilience while also contributing to vulnerability under certain conditions (

Domínguez-Morano 2018).

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its valuable findings, this study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the sample was limited to 100 medical students from a single academic institution, which may restrict the generalizability of the results to broader populations. Additionally, the use of self-reported data may introduce biases related to personal perception, social desirability, or underreporting, particularly when addressing sensitive topics such as mental health and religious beliefs. The cross-sectional nature of the study also limits the ability to draw causal inferences, as it captures perceptions and experiences at one point in time.

Furthermore, although the 16-item questionnaire was carefully designed to address the study’s objectives, it was not based on previously validated instruments. This may affect the comparability of the findings with existing research and limits the ability to evaluate measurement reliability. Some complex constructs (such as feelings of guilt or perceived hardships) were assessed using simplified categorical items with limited response options, which may not fully capture their nuance. In addition, the questionnaire did not include a specific item addressing whether religion itself was perceived as a source of hardship, an aspect that may be relevant for future investigation.

The statistical analysis was also limited by the relatively small sample size. More advanced methods, such as logistic regression, could not be used effectively because there was not enough statistical power and the response categories were unevenly distributed.

Future studies should consider using larger, more diverse, and multi-center samples to enhance external validity. Longitudinal designs would be valuable for exploring how religious beliefs and mental health coping strategies evolve over the course of medical training. Qualitative approaches, such as interviews or focus groups, could provide richer insight into the personal experiences underlying the quantitative trends identified in this study. Comparative analyses across religious groups, as well as between religious and non-religious individuals, may further deepen understanding of how spiritual or secular frameworks shape psychological resilience or vulnerability.

Future research should also consider practical implications for students’ well-being. Providing prayer spaces or opportunities for minority religious groups to meet may foster inclusion and community support. Likewise, targeted approaches for non-religious students who often acknowledge the benefits of psychological support yet may be less likely to access it, could help reduce differences in help-seeking. Addressing the needs of both religious and non-religious students may lead to more balanced and effective mental health support within academic environments.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights that religion plays a significant role in shaping mental health, though its effects are not uniformly positive or negative. For many students, it serves as a valuable psychological resource, offering coping strategies, emotional stability, and a sense of belonging; yet for others, it may also contribute to distress through guilt, fear of failing religious obligations, or social stigma.

These findings, drawn from the perspectives of international medical students, provide insight into how future health care professionals view the impact of religion on their own well-being. They also suggest that personal religious or non-religious orientations may influence attitudes toward well-being, help-seeking, and patient care.

The varied experiences reported by participants reinforce the importance of personalized and culturally sensitive mental health approaches that acknowledge students’ spiritual backgrounds without assuming uniform effects. Looking ahead, future research should explore these dynamics through longitudinal and cross-cultural designs, clarifying how religiosity, spirituality, and non-belief evolve over time in relation to psychological resilience and vulnerability.