His emphasis on Christians as an external threat, while excluding Jews, arose from a combination of factors including their visibility, demographic weight, the symbolic power of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, international connections, and rhetorical effect. In this way, Christians served as a stronger “mirror” for Muslims to recognize their own shortcomings.

In short, al-Khalīlī’s discourse was not limited to the practical defense of property but functioned as a warning that called the Muslim community to construct its boundaries consciously against both external threats and internal dissolution. His admonitions to waqf administrators represent more than a moral reproach; they serve as a caution against internal disintegration. This critique highlights the necessity for the community to discipline its boundaries against both internal laxity and external pressures. Within this framework, intercommunal relations in Ottoman Jerusalem did not take the form of a closed and homogeneous structure but rather of a social field grounded in the circulation of different forms of capital. The mixed fabric of neighborhoods allowed individuals to navigate between both Muslim and non-Muslim circles, mobilizing economic, symbolic, and social capital in their interactions.

2.1. Conversion and Acceptance into the Community

In the early modern world, conversion was a closely observed event at both individual and social levels, functioning as both an act of faith and a public performance. From that moment onward, converts moved beyond personal spiritual experience and entered the representational sphere of the state, community, and counter-community. In Brummett’s words, converts became “public property,” their identities exposed to the meaning-making processes of others on political and symbolic levels. They also became spectacles orchestrated by public authorities to reinforce religious and political order. During such public ceremonies, converts received rewards such as new clothes, gifts, and stipends, reinforcing their new identity and allegiance in the public eye (

Brummett 2017, pp. 110–11).

Identity formation can be seen as a process shaped by religion, gender, family ties, and economic position. The intersectionality framework provides an analytical lens to examine how religious identity emerges through the interaction of these axes and how power relations become visible in this interplay. In this context, conversion appears as a process of re-positioning within the historical setting where diverse normative orders intersect (

Riedel and Rau 2025, pp. 388–408).

In Jerusalem, where communal boundaries were continually reproduced through social interaction, individuals positioned themselves by mobilizing multiple forms of capital across different social fields. Conversion marked the threshold at which these multilayered fields intersected. As an individual’s religious identity changed, kinship ties, gender roles, and economic position were likewise redefined. Individual transformations of identity were expressed not only through social negotiation but also through specific ritual and symbolic practices.

In the Ottoman Empire, conversion to Islam occurred through an institutionalized ceremony with both official and symbolic dimensions. The technical procedure was uniform across gender, status, and age. It was sufficient to raise the right index finger and, before two Muslim witnesses, recite the shahāda affirming God’s unity and Muḥammad’s prophethood (JCR, 203/55). The removal or symbolic sale of the yellow turban and the donning of a white one marked separation from the former community (

Cohen 1984, pp. 74–76). The ceremony thus reconstructed religious, legal, and social boundaries along the axes of faith and community, enacting a symbolic rupture from the former group through ritual and naming, while affirming a new identity through legal norms, court registration, and, at times, spatial relocation.

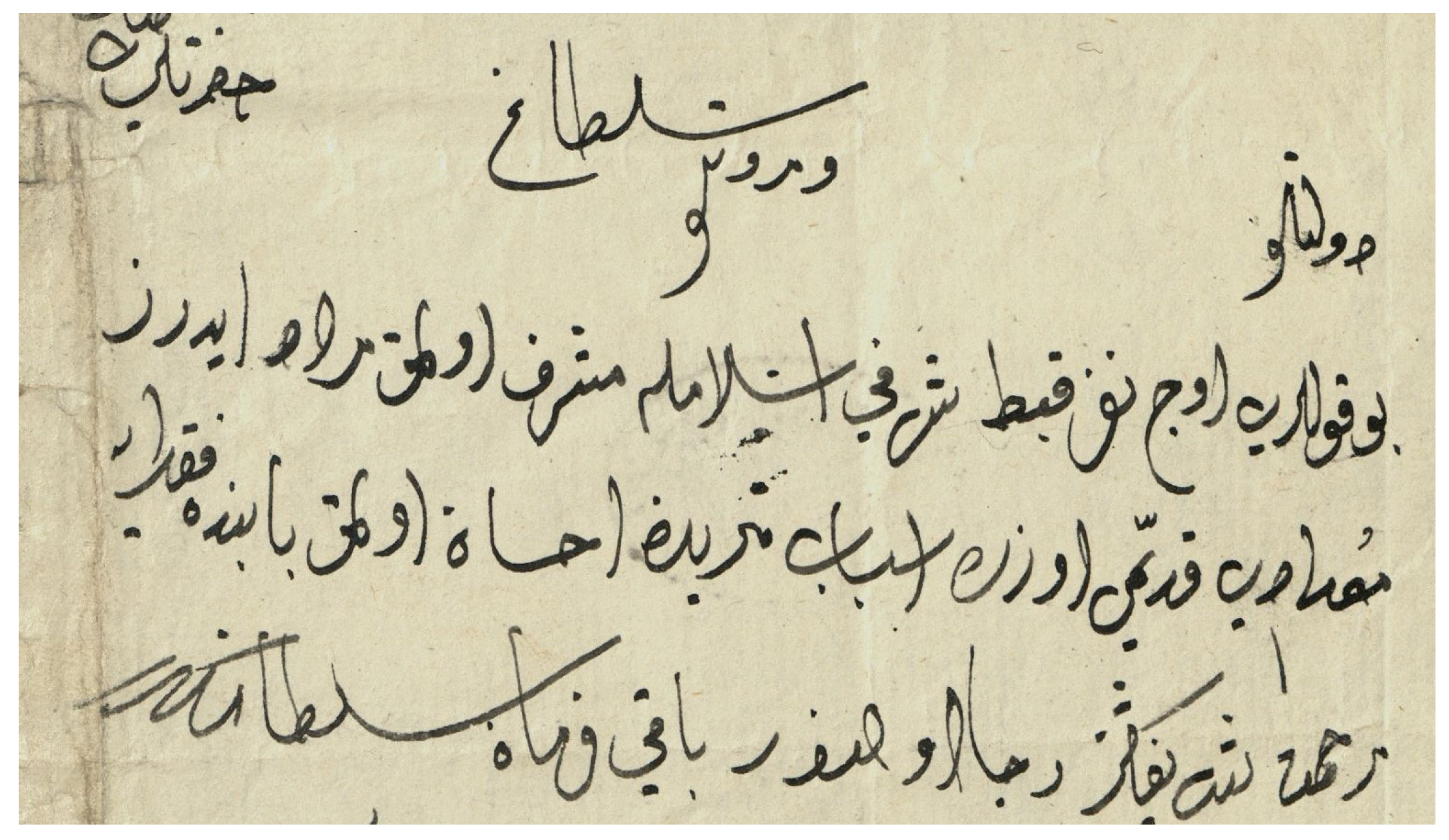

The stage of this identity transformation was the local court, while for those residing in or able to reach Istanbul, it was the imperial palace. A 1761 document (

Figure 1) records two Jewish women who sought to embrace Islam before the sultan. Converts submitted petitions requesting the sultan to prompt them with the shahāda and could receive material aid (BOA, C.ADL. 4/259). Notably, the women identified themselves as “Jewish subjects” prior to conversion, a phrase marking both their former affiliation and the starting point of their transition into a new community. Yet, as

Çetin (

1999, pp. 78–79) notes in the Bursa case, conversion before a qāḍī or even the sultan did not always ensure social acceptance, tensions often arose between official Islam and actual communal recognition, and some converts were required to reaffirm their faith in court to dispel public suspicion.

While court records contain straightforward typologies of conversion in which the shahāda and name change were officially registered, fatwās provide information about cases where social reactions and socio-economic aspirations played a role. The conversion of the Sulaymān through the shahāda, and that of the woman who abandoned the name Aṭya and adopted the name Emīne, represent examples of this straightforward acceptance typology (JCR, 215/1). The case of Mūsā, recorded as “Muḥammad al-Muhtadī,” with Qurʾānic prayers noted in the court register, exemplifies the spiritual and symbolic dimensions inherent in the conversion process. The epithet “al-Muhtadī” also marked his recognized place within the community (JCR, 234/175).

In court cases, converts were generally recorded not with the names of their non-Muslim fathers but with names such as “Raḥmān” or “ʿAbdallāh,” the latter meaning “servant of God.” In this way, their new Muslim identity was documented, while ties to their family lineage were severed (

Aydın 2022, p. 178). However, the name ʿAbdallāh was also common among Arabs and Eastern Christian communities prior to Islam. The most significant example is the Prophet Muḥammad’s father. In 1705, when ʿAbdallāh Naṣrānī converted to Islam, he abandoned this name, which was used in both communities, and adopted the name “Muḥammad,” thereby making his new identity more explicit (

Figure 2, JCR, 203/55). Here, the symbolic dimension of conversion becomes clear. Through the change of name and the public recitation of Qurʾānic formulas, conversion was publicly affirmed as a recognized social identity.

Although a change of name was not a compulsory element of conversion in Islam, it often symbolized the weakening of former ties and the consolidation of new communal boundaries. The new name affirmed the convert’s inclusion within the Muslim community and reflected a dual process of identity reconstruction at both individual and collective levels. For instance, Circis b. Bôlis al-Armanī adopted the name “ʿAbdallāh” upon conversion. While some converts later abandoned this name, others retained it, indicating that name change was less a legal obligation than a symbolic act (JCR, 215/1).

If the adoption of a new name represented the symbolic boundary of belonging, the reconfiguration of family and property ties revealed its material consequences. The Christian woman Maryam, who converted to Islam in 1785, was the daughter of a priest. Maryam’s relationships with both her priest father and her husband would later become defined by financial disputes (JCR, 266/43).

It is worth noting that registering converts in court did not completely sever them from their past. Many later approached the court to adjust family relations or to resolve financial and social disputes. As will be shown below, the fatwā concerning the continuation or dissolution of marriage during the waiting period (

ʿidda), depending on the husband’s stance (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, p. 54), was put into practice in the 1719 case of Fatma (JCR, 213/146). For male converts and mixed marriages, the normative framework was shaped by fatwās that prioritized family unity and social peace.

According to the Islamic principle “al-Islām yajubbu mā qablahu” (Islam effaces what preceded it), fatwās safeguarded the marriage and household of new Muslims, resolved disputes, and regulated matters such as the status of children and the possibility of irtidād (apostasy) (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, pp. 2–3, 7). The case of a youth of Ashkenazi origin who voluntarily converted and adopted the name Aḥmad exemplifies voluntary acceptance (JCR, 203/55). Likewise, the 1745 transfer of a convert’s child to the Muslim father by his non-Muslim mother reflects a model in which acceptance was established through both familial agreement and court registration (JCR, 245/35).

Finally, the acceptance of converts into the community also appeared in the socio-economic sphere through the framework of inheritance and debt law. Based on the principle that “a Muslim cannot inherit from an unbeliever, nor an unbeliever from a Muslim,” fatwās restricted converts from inheriting property within their former community (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, pp. 55–56). The cases and fatwās that will follow below illustrate how this rule was applied with evidentiary precedence.

In conclusion, admission into the community was a multifaceted process that intersected the realms of identity, faith, family, and property, though shaped in each domain by different paths and rules.

2.2. The Legal and Social Echoes of Conversion: Marriage, Children and Community Ties

In Ottoman Jerusalem, conversion operated within legal and social spheres, influencing property, kinship, and communal relations. The court registers documented converts’ rights concerning marriage and children, thereby formalizing their new status, while fatwās reinforced the social legitimacy of conversion through religious and moral discourse. Drawing on intersectionality theory, this section explores how conversion in Ottoman Jerusalem operated at the crossroads of law, gender, kinship, and communal belonging, and how it contributed to the construction of communal boundaries.

One court record and fatwā examined in this study illustrate this process through the case of a non-Muslim woman who converted to Islam and subsequently married a Muslim man. The case involved questions of the marriage’s sharʿī validity, the dower (

mahr), the rights of children, the severing of ties with the former community, and integration into the new one. The fatwā ruled that if the woman converted after consummation, the continuation of the marriage during the waiting period (ʿidda) depended on the husband’s conversion. If he did not convert, the marriage was annulled immediately upon the wife’s conversion, and he was required to provide maintenance during the ʿidda (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, p. 54). This judicial ruling pertains to the sphere of Islamic familial jurisprudence. In cases of annulment, the husband was also obliged to provide accommodation for the woman (

Günay 2010, pp. 48–50). Such provisions preserved the distinction between divorce (

ṭalāq) and annulment (

faskh), ensured the woman’s economic security, and protected her new religious identity through the right to maintenance. Overall, the fatwā reveals that conversion functioned as a legal and social process that redefined the convert’s family relations, right to support, and position within the community.

The fatwā, which stipulated that the marriage would be determined during the waiting period according to the husband’s stance, provided the legal basis for the court’s decision in the 1719 case of Fatma. The court applied the provisions of annulment and maintenance exactly as stated in the fatwā. Fatma, the daughter of the Jew Shuʿa, converted to Islam before the court at the age of fourteen. Although there is no explicit evidence of her relationship with Sayyid Aḥmad, who testified that he knew Fatma in court, his invitation may have influenced her conversion. Upon Fatma’s entry into Islam, the qāḍī summoned her husband Yasef to accept Islam, but Yasef refused. As a result, the qāḍī annulled the marriage (

Figure 3, JCR, 213/146). The Qurʾān prohibits Muslim women from marrying non-Muslim men under any circumstances, while Muslim men may marry Jewish and Christian women (

Qurʾān n.d., al-Baqara 2:221; Qurʾān, al-Māʾida 5:5). After the waiting period, Fatma married a Muslim man and claimed the possessions given to her as mahr from Yasef and his mother, successfully recovering them. This marked the formal recognition that she was no longer Yasef’s wife and that he retained no rights over her.

This case highlights how, at the intersection of gender and religious status, conversion raised questions concerning women’s financial rights (maintenance, mahr, personal property) alongside the communal belonging of their new identity. Thus, conversion functioned both as a legal rupture and as a material guarantee of belonging. Fatma’s possessions gold and silver jewelry, clothing, fabrics, and household textiles offer valuable insights not only into personal property but also into the domestic living standards of the period.

In sum, while Fatma’s case shows conversion as a legal and socio-economic negotiation, the case of Emīne mentioned above was limited to a declaration of faith and a name change. Thus, conversion could at times constitute a complex process surrounded by social and legal tensions, while at other times it remained a simple ceremony confined to the declaration of faith and the alteration of one’s name.

Tucker’s examples likewise indicate that conversion was not a single act but a process that set in motion a series of legal consequences. A woman’s adoption of Islam reshaped both her own identity and her husband’s legal position, affecting the procedure of divorce and his financial responsibilities (

Tucker 2000, pp. 52–55, 82). Conversion thus appears as a social event with a “domino effect,” compelling the transfer of economic capital from the woman’s former husband and thereby reconfiguring intercommunal financial relations through law. In other words, individual conversion initiated a flow of material capital from the old community to the new one. In this sense, beyond Barth’s notion of “boundary making,” conversion, through Bourdieu’s theory of capital, emerges as a process that restructures the economic field between communities, with the law serving both to recognize identity transformation and to redistribute resources.

A contrasting narrative of rebirth appears in a fatwā concerning a non-Muslim man who converted to Islam while his Christian wife remained in her faith. The validity of the marriage was questioned, and the response emphasized the Muslim community’s duty to protect the woman. The fatwā prohibited Muslims from separating her from her husband, returning her to her family and spreading rumors regarding the legitimacy of the marriage. This ruling illustrates how conversion affected family law and communal relations within the Ottoman legal framework. According to the decision, if a man from amongst the People of the Book converted to Islam, his marriage remained valid even if his wife did not convert. Procedural irregularities from the earlier period such as the absence of a guardian, lack of witnesses, or contracting the marriage during the ʿidda were rectified upon entry into Islam (

Shaykh al-Islām Fayḍ Allāh Efendi 2009, pp. 26–27). This reflects the legal principle that “Islam effaces what preceded it.” Fundamentally invalid unions, such as marriages within prohibited degrees of kinship, however, remained excluded from this rule (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, pp. 55–56).

In a similar fatwā, the ruling goes beyond a legal determination and assigns Muslims an explicit religious duty to preserve the marital union and support the newly converted man against those seeking to separate him from his wife. While the fatwā envisions the protection of the marriage both legally and socially after conversion, it also places on the Muslim community the responsibility to uphold this bond against attempts to disrupt it. The warning in the text, invoking the ancient tribes of

Qays and

Muḍar, questions why the zeal shown for ethnic solidarity is not extended to religion. This call for unity based on religious identity reflects an effort to prevent potential tensions during the conversion process in Ottoman cities and to safeguard both the marital bond and the social legitimacy of the new Muslim (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, p. 57).

Indeed, Krstić acknowledges the “open and integrative” aspect of Ottoman policies toward converts, yet emphasizes that texts frequently reveal experiences of exclusion, suspicion about sincerity, and denigration based on the past. Such exclusion was present both within the Muslim society and among non-Muslim communities. This phenomenon can be seen as a moral stigmatization and exclusion strategy aimed at preserving communal integrity (

Krstić 2011, pp. 17, 157–18). Community leaders, in particular, sought to prevent the conversion of orphans and the vulnerable, yet such cases provoked deep anxiety and collective unease within the community (

Cohen et al. 1996, pp. 253–65).

In this context, a fatwā recounts the case of a Christian woman who, after converting to Islam, faced pressure and reproach from her former community. The woman, of sound mind and previously of dhimmī status, embraced Islam in her hometown with the testimony of Muslims known as

al-Zaghālīla. She later moved to another village and, after falling in love with a Muslim man, married him before the qāḍī of Jerusalem. The fatwā inquiry addressed whether any external interference with the woman or her marriage was permissible, particularly whether reproaching or condemning her affection for her husband under the influence of her former Christian relatives could be considered religiously legitimate. Together with the previous fatwā, this ruling reveals the social tensions that often accompanied conversion in the multi-religious communities of the Ottoman Empire (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, pp. 54–55). As

Krstić (

2011, pp. 157–58) observes, converts frequently experienced both acceptance and exclusion, their sincerity questioned by members of the Muslim community as well as by their former co-religionists.

After the registration of the conversion in court, this fatwā affirmed that the rights of the woman and her husband within the community had to be absolutely protected. The woman’s entry into Islam was presented as a test of the honor and integrity of the Muslim community itself. This trial was framed in terms of warning against hypocrisy for those who might be swayed by the influence of the woman’s Christian relatives. In the fatwā, the muftī exalted her conversion as “God’s illumination,” and declared that anyone who opposed her right to a dowry or her marriage would be guilty of “enmity toward God and His Messenger,” counting such people among “the party of Satan.” The reactions of her former Christian relatives must therefore be understood within a framework of “conversion and betrayal.” The fatwā explicitly ruled it impermissible for Muslims to listen to her Christian kin, to reproach her, or to attribute fault to her. Accordingly, the woman’s decision to convert was recognized as an act of her own free will, requiring neither the permission of her family nor of her former community. The fatwā did not limit itself to a legal ruling but also warned society against such challenges, concluding with the ḥadīth of the Prophet that emphasized the virtue of conversion: “If God guides a single person through you, it is better for you than red camels (a symbol of great wealth)” (

al-Khalīlī n.d. vol. 2, pp. 54–55).

This conversion case is significant for understanding how relatives and the former community sought to interfere with the woman’s dowry rights, revealing the discriminatory attitudes and pressures faced by converts. The fatwā records that the woman converted to Islam before going to the man she loved, though it remains possible that their relationship predated her conversion. If she converted for the sake of marrying him, the case illustrates that conversion could be driven not only by theological conviction but also by emotional and personal motives. Yet this decision also provoked a crisis of belonging and social tension. As Tucker notes (

Tucker 2000, pp. 52–55), when a woman converted to Islam and her husband refused to do so, the marriage was legally annulled. Conversion therefore marked both entry into a new community and the legal severance of ties with the old one, operating as the formal registration of an exit from a community. From this perspective, the processes of integration and exclusion become equally visible.

On the other hand, women’s financial rights, such as mahr and dowry, were often seen less as personal property and more as part of the family’s collective capital. The mahr received by a woman was considered an indirect gain for her family. Consequently, a woman’s conversion to Islam created the risk that this “family capital” would pass into another religious community. Her former relatives may thus have sought to prevent an economic loss by insisting that “this property should remain within our community.” In their eyes, her conversion rendered her economic rights questionable. By claiming a share in her mahr, they were, in effect, attempting to maintain her former belonging in both legal and symbolic terms. Moreover, the act of demanding the mahr back could also function as a deterrent mechanism, conveying the message that embracing a new faith entailed a tangible material cost.

Ultimately, the Christian relatives’ claim to the mahr can be interpreted as a strategy aimed both at protecting economic interests and at preserving communal boundaries. This shows that cases of conversion were not only instances of religious transformation but also arenas where conflicts over economy, family capital, and communal belonging intersected.

Finally, the fatwā engaged in interreligious comparison, noting that the Armenian, Jewish, and Christian communities protected their women despite the “falsehood” of their respective faiths. Muslims, by contrast, were criticized for failing to defend a woman who had embraced Islam, an act described as “the greatest disgrace.” The admonition to Muslim men that “white turbans are the crown of Islam” served as a symbolic affirmation of communal identity, countering the yellow headgear that marked non-Muslims and urging the preservation of Muslim distinctiveness. These symbols functioned as visible markers of identity that concretized communal boundaries. In this sense, the fatwā functioned as both a legal ruling and a sermon-like admonition intended to reinforce the social acceptance of new Muslims and to strengthen the faith-consciousness of the Muslim community in multi-religious Ottoman Jerusalem. The woman’s conversion was portrayed in al-Khalīlī’s fatwā not simply as an individual act of faith but as an event in which communal boundaries were redefined and the distinction between “us” and “the other” made tangible. In the same fatwā, the phrase “she has left unbelief and become sinless” encapsulated a narrative of rebirth that erased the convert’s past (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, pp. 54–55).

These fatwās consolidated communal boundaries through norms, rituals, and kinship ties, thereby establishing an invisible yet effective form of authority. This corresponds to Bourdieu’s notion of “symbolic power,” which operates precisely when legal-religious norms are accepted as unquestioned truths and are reproduced by community members themselves (

Swartz 2013, pp. 99, 123). In the first instance, muftīs, most notably al-Khalīlī, redrew the boundaries of the social field through the language and symbols deployed in their fatwās, thereby defining communal identity. He exercised “symbolic power” by creating a new form of social recognition at the intersection of identities, defining the criticisms of Christian relatives and the Muslims who supported them as coming from “those who deny God and His Messenger”. By doing so, he reinforced the convert’s belonging to the Muslim community within the multi-communal setting of Jerusalem. His discourse translated abstract communal boundaries into lived social practices, thereby reinforcing their legitimacy. Secondly, the actions of social actors combined both material and symbolic interests. Marriage choices in this context served as instruments for securing such interests, functioning as strategies to maintain or elevate one’s social position through kinship ties.

As

Brummett (

2017, pp. 103–28) has indicated, the muftī, as in previous cases, transformed the convert into a public figure. The newly incorporated believer emerged as a public figure symbolizing communal unity and serving the state’s performative displays of legitimacy. In these ceremonies, conversion functioned as a public performance of order, authority, and representation between religious communities.

Children in Conversion Records

Ginio, citing Rozen, recounts a case of conversion that shook the Jewish community of seventeenth-century Jerusalem. According to Franciscan sources cited by Rozen, two young brothers converted to Islam. The twelve-year-old elder brother chose Islam in order to resist and punish his father’s violence, while the eight-year-old younger brother followed the same path out of jealousy at the attention his elder sibling had received. The elder brother’s conversion was recognized as valid, whereas the younger brother was returned to his family for a large ransom. Yet this ransom and the child’s recovery provoked the anger of Muslims, who declared that they would take revenge on the Jewish community (

Ginio 2001, p. 98). It should be noted that the term “child” in this account originates from the Franciscan sources themselves, reflecting their own moral and theological perspective rather than the legal terminology of the Ottoman court.

According to this example that conversion can be influenced by faith, as well as by family conflicts and emotional responses. The twelve-year-old boy’s decision to convert as an act of “disobedience” toward his father suggests that conversion sometimes functioned as a means of personal revenge or emancipation. His younger brother’s choice, driven by jealousy, reveals that even within the world of children, conversion could express rivalry and the pursuit of attention. In this case, family conflict and negotiation clearly take center stage.

This case highlights the psychological implications of conversion, alongside its sociocultural and economic dimensions. Aköz, noting the timing of conversion in the Konya context, observes that converts were often young and frequently converted after the death of a parent (

Aköz 2000, pp. 550–51). In comparison with the case above, the two brothers also experienced a symbolic form of paternal loss. This provides an important perspective for understanding the emotional and individual dimensions of conversion.

Fatwās and court records indicate that religious affiliation was influenced not only by legal norms but also by family will and inter-communal power dynamics. Fatwās suggest that when a father converted, small children were automatically regarded as Muslims “following their origin.”

A court record dated 1759 offers a noteworthy example concerning children. Naqīb al-Ashrāf

3 Sayyid ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Ḥusaynī appeared in court together with the young son of Rabbi Aharon and requested that the boy be kept away from his father on account of violence. In the presence of Jerusalem notables, Rabbi Aharon was warned and instructed not to beat his son without reason. On the same day rumors spread that the child had come to al-Ḥusaynī wishing to become a Muslim and that al-Ḥusaynī had prevented the conversion while accepting bribes from Jewish representatives. Thereupon al-Ḥusaynī requested an inquiry from the court. In a session attended by the Jerusalem mutasallim (district governor), prominent ʿulamāʾ and Jewish representatives, it was established that the rumor contained slander and sedition and had originated with the Shāfiʿī muftī Saʿīd. In the end, representatives of both the Muslim and Jewish communities confirmed al-Ḥusaynī’s reliability and the rumor was annulled (JCR, 242/26).

In this case the rumor that a child wished to convert to Islam posed a potential “danger” to the Muslim-Jewish boundary. The episode illustrates that beyond being a simple “possibility of conversion,” such situations reshaped communal boundaries through rumor, court practice, and collective approval. From the perspective of intersectionality, the child, defined in the court as ṣaghīr (minor) and vulnerable by virtue of age and religious identity, the father Rabbi Aharon as familial authority, Naqīb al-Ashrāf al-Ḥusaynī as protector-mediator and the target of rumor, as well as Jewish communal leaders and Ottoman officials all intersected along different axes of identity. In this process the boundaries between the Muslim and Jewish communities were redrawn.

The child who lacked discernment (tamayyuz) due to his age and identity was in need of protection both from the Jewish community and from the Ottoman court system. Naqīb al-Ashrāf Sayyid ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Ḥusaynī, by virtue of his religious nobility (sayyid status) and his elite position in Jerusalem society, emerged as “protector” and mediator, yet simultaneously as the target of rumor. The Jewish father Aharon and the community leaders appeared before the court both in relation to domestic violence and because of the rumors concerning the child. The judicial process functioned to redefine and reinforce this boundary, and the declaration that the rumor was false ensured that the boundaries of both communities remained “in place.” The participation of Jewish leaders in the court and the joint approval of the Muslim ʿulamāʾ sustained the boundary by mutual consent and regulated the relationship between the two communities.

At the same time, the conversion of a very young child raised theological doubts regarding his capacity to distinguish between good and evil. In Islamic law this situation is treated within the framework of “ḥajz” (guardianship restriction), a judicial limitation placed upon a person due to lack of legal capacity. In this context the conversion of children could be considered valid only if their intellectual and legal competence was recognized by the court (

Ginio 2001, p. 99). Yet the frequent absence of age references in conversion records, replaced instead by the formula that the person had reached puberty (

āqil bāligh), suggests that exceptions may have existed (

Tramontana 2014, p. 45).

Both the example transmitted by Ginio and the petition of Rabbi Aharon’s son reveal that vulnerable children, defined by age and religion, were positioned less by individual will than by the rules of the social field shaped through domestic violence and inter-communal boundary tensions.

A fatwā addressing whether the underage children of a Muslim convert should also be counted as Muslims illustrates that conversion was both a matter of belief and a question of social order, entrenching communal boundaries through kinship, bodily ritual, and collective oversight. Furthermore, the fatwā indicates that conversion entailed a transformation of identity shaped through family ties, social oversight, and bodily discipline. According to this ruling, minor children and the mentally ill were deemed Muslims by following their father’s religion, regardless of personal will. After reaching puberty, however, conversion became an individual responsibility, while renouncing Islam (irtidād) was regarded as a grave offense carrying severe penalties (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, pp. 22–23).

In the fatwā, the requirement of circumcision as a sign of faith, along with the absolute prohibition of a Muslim father’s daughter marrying a non-Muslim, served to secure the retention of subsequent generations of the new Muslim family within the community. The reminder of the duty to “command right and forbid wrong” emphasized communal oversight as much as individual responsibility. According to the fatwā, Muslims were expected to intervene collectively to ensure that the children of new converts fulfilled their religious obligations (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, pp. 22–23).

A court record from 1762 (

Figure 4) showed that the question of which community the children of a mixed marriage would belong to was brought before the Jerusalem court. Maḥbūra, the daughter of the Jew Avraham, was married to the convert Muḥammad

. After her husband’s conversion to Islam, Maḥbūra declared that she had handed over her young son (ṣaghīr) Ḥayyim to his father “of her own free will, without any coercion.” The qāḍī, after recording the mother’s statement, specifically noted that the child was in good health. The convert father then lawfully received his son. To preempt possible objections from the Jewish community, the court formally recorded the mother’s consent and verified the child’s sound health, thereby completing the process within a legal framework. The note on the child’s “healthy condition” served as a preventive safeguard. This case, registering the incorporation of a child of Jewish origin into the Muslim community, illustrates that conversion and communal affiliation were shaped through family agreement and judicial procedure rather than individual religious choice. Ultimately, it exemplified the practical application of the fatwā’s principle of “following the origin,” turning a normative precept into a concrete legal and social ruling (JCR, 245/35).

Examples from the seventeenth century reflect a similar situation. In cases concerning the custody of children, it is evident in many instances that only the husband converted, while the wife, even when negatively affected in her life, retained her original religion. In all such cases, the husband’s conversion and the wife’s refusal to become Muslim resulted in the wife losing custody of the children (

Tramontana 2014, p. 53).

A similar case occurred in reverse in Konya. The marriage of Gülvert Hatun, an Armenian woman who embraced Islam, was rendered null and void due to her husband’s refusal to convert to Islam. However, custody of their underage children was granted to the mother (

Aköz 2000, p. 556). The transfer of children who had not reached puberty to their mother’s religion illustrates how Ottoman law defined the link between guardianship and faith. The will of the children was not considered; owing to their young age, the mother’s religious identity was deemed determinative. From this, it becomes clear that at the intersection of gender, custody, and minority status, it was parental religious and legal authority rather than individual choice that determined a child’s religious identity.

In the example of Bursa, Çetin notes that the main reason children were transferred to their converted parents was to guarantee their Islamic upbringing. However, as childcare responsibilities were not always the father’s, young children were sometimes permitted to remain with their non-Muslim mothers for a period of time. For example, when Mehmed of Armenian origin converted to Islam and separated from his Christian wife Gülfın, their young daughter Maryam was left with her mother until she reached an age at which she might “grow accustomed to unbelief” (

kufr-i maʾnūs). Afterwards she was to be transferred to her father (

Çetin 1999, p. 92). This suggests that the ability of a small child to adapt to their surrounding environment and adopt its values could make it more difficult to embrace a Muslim identity later on. The concept operated as a boundary the preservation of the child’s religious identity and guided the decisions of the qāḍīs. In the Ottoman legal idiom “kufr-i maʾnūs” denoted not merely habit but also the risk of an orienting tendency toward an alternative identity. This signified the possibility that young children might drift away from the Muslim community and identify with a different religion and culture instead. Thus, this case elucidates that conversion involved transformations operating at both the individual and familial levels. The invocation of kufr-i maʾnūs reveals how communal boundaries were safeguarded through concerns about the gradual socialisation of children, thereby reinforcing the preventive function of Islamic legal reasoning.

The fatwā cited above had stipulated that minor children followed the religion of their fathers, but upon reaching puberty they would be able to exercise their own will in matters of religious choice. In the conversion case of Mūsā in 1705, his registration as a “youth” emphasized that he had reached puberty and acquired legal capacity for religious responsibility. The court accepted without hesitation his voluntary recitation of the shahāda and his adoption of the name Aḥmad. In this way the court applied the second stage anticipated by the fatwā, namely the principle that after puberty individual will should be decisive (JCR, 203/55).

In a 17th-century case in Palestine, it was stated that in the divorce case of Shamsīa, who had converted to Islam, the older children opted to remain in their father’s religion. Meanwhile, the two younger children were accepted as Muslims by following their mother’s lead (

Tramontana 2014, p. 46). The divergent affiliation of elder and younger children in this case exposes the fragile and negotiable nature of communal boundaries, where age and maturity shaped the legitimacy of religious belonging.

In conclusion, the fatwā articulated the principle that children follow their father’s religion through normative indicators such as the obligation of circumcision and the absolute prohibition of a Muslim daughter marrying a non-Muslim, thereby defining Muslim identity within a legal and moral framework. Court records, in turn, reveal how this principle was implemented across diverse social contexts. Religious identity thus emerges as a social construct continually renegotiated at the intersection of family relations, gender dynamics, communal affiliations, and law.

2.3. Socio-Economic Aspirations: The Impact of Religious Conversion on Inheritance and Financial Obligations

In the last days of

Ramaḍān (July) in 1785, the Jerusalem court dealt with the case of Maryam, the daughter of a priest from Ramallah. The case of Maryam highlights the intersection of religion, gender, and economic dependency in processes of conversion. Her decision to embrace Islam broke both marital and paternal ties. When her husband Musallam b. Naṣr Allāh Shāhīn refused to convert, the qāḍī annulled their marriage. On the same day, Maryam filed debt claims against both her husband and her father but was unable to present any evidence. Her attempt to pursue financial rights reflects the search for economic security that often followed conversion. Yet her inability to substantiate her claims before the court also reveals the evidence-based procedural logic that structured judicial authority (

Figure 5, JCR, 266/43).

In this case, Maryam was not merely a convert; she simultaneously embodied the identities of a priest’s daughter, a woman, a wife, and a creditor. This multiplicity of roles reveals a process through which conversion reconfigured both familial hierarchy and social status. Since her father was a clergyman, her adoption of Islam produced a dual rupture. It was at once an act of defiance against paternal authority and a symbolic separation from the Christian community. Her conversion thus represents a form of rebellion against patriarchal power and a passage into a new field of identity.

At these points of intersection, Maryam sought to renegotiate her right to belong within communal, familial, and legal spheres. While her new status as a Muslim woman granted her formal legal autonomy vis-à-vis her father and husband, the loss of her former social networks weakened her capacity to provide evidence or summon witnesses, limiting her ability to translate her new identity into material empowerment.

Maryam’s experience was not an isolated case but part of a broader legal and social pattern in eighteenth-century Ottoman Jerusalem, where conversion intersected with property, taxation, and imperial policy.

Cases from eighteenth-century Jerusalem indicate that conversion was closely bound up with economic expectations such as inheritance, mahr, and disputes over family property. These examples reveal that the social and financial outcomes of conversion did not always favor the new Muslim. In addition to controversies over inheritance, converts of dhimmī origin were exempted from paying the

jizya tax. Conversion therefore entailed, in addition to the declaration of faith, a fiscal and political transformation. For example, when the villagers of Dayr Abān in seventeenth-century Palestine converted, their dispute with the jizya collector over whether they remained subject to taxation was brought before the court. The court ruled that with their conversion to Islam they were no longer liable (

Tramontana 2014, pp. 68–72).

This connection between conversion and fiscal obligation was not limited to taxation but also appeared in the system of state-sponsored assistance for new Muslims.

The Ottoman administration did not ignore the demands of the newly Muslims. In this context, the practice of kisve bahāsi (a clothing allowance granted to new converts) and the assignment of certain duties to converts suggest that conversion could also be pursued for purposes of social and economic interest. Through this practice, converts were provided not only symbolic but also material support, including temporary subsistence aid, clothing and housing assistance, and cash payments.

Moreover, those seeking conversion submitted petitions (

arżuhāl) to the sultan requesting the kisve bahāsi (

Güneş 2025, pp. 431–34). The petitions contain statements indicating that Islam was preached to them or that they were honoured with Islam. For example, three Copts desiring to embrace Islam wrote to Mehmed IV requesting assistance (

Figure 6).

The phrase “we wish to be honored with Islam” recorded in the petition indicates that they had not yet converted. The petition itself points to the potential misuse of the kisve bahāsi practice. Nevertheless, the request was not ignored, and the chief treasurer (ḥazīnedārbaşı) was ordered to provide assistance to the Copts (BOA, AE. SMMD.IV 8/762). This petition highlights the entanglement of economic aspiration and imperial patronage in conversion dynamics, revealing how material incentives could both encourage sincerity and open the door to pragmatic, strategic uses of Islamization.

The cases examined here do not provide detailed information regarding the role of the jizya or the allocation of the kisve bahāsi; however, they indicate that conversion could entail a potential shift in legal status with implications for fiscal or military responsibilities. This transformation, whether actual or nominal, directly influenced property rights and social standing.

In eighteenth-century Jerusalem, the fatwās issued by al-Khalīlī indicate the fundamental principles of Ottoman sharʿī law regarding conversion and, in particular, their reflections on inheritance and debt law. These fatwās are based on the principle that a person’s religious status at the time of death is the key factor in determining financial rights and liabilities.

The courts consistently applied the foundational principle of Islamic inheritance law that “inheritance is determined by the religious status at the time of death” (

al-Bukhārī n.d., ḥadīth no. 6764;

Sunan Abī Dāwūd n.d., ḥadīth no. 2909, 2911;

Okur 2007, pp. 103–5). If a child was non-Muslim at the time of the father’s death, later conversion to Islam did not retroactively alter the distribution. This principle functioned as a safeguard against instances where conversion might be motivated by self-interest. Preventing the instrumentalization of religious conversion for the acquisition of worldly rights such as inheritance was one of the key aims of Ottoman inheritance law. Thus, whether conversion was sincere or opportunistic, inheritance rights were determined by the status at the moment of death, eliminating grounds for dispute.

The first of al-Khalili’s fatwās is recounted in a style similar to that used in court records to describe events. This fatwā addresses the matter of inheritance rights in the aftermath of a Christian father’s demise. Two sons (Sālim and Sirḥān) had converted to Islam during their father’s lifetime, while the third son (Dāyib) remained Christian. According to the fatwā, inheritance “is fixed according to the religious status at the time of death.” This juristic principle is based on the rule “lā yarithu’l-muslimu’l-kāfira wa-lā’l-kāfiru’l-muslima”, namely, a Muslim does not inherit from a non-Muslim, nor does a non-Muslim inherit from a Muslim. Consequently, since at the time of their father’s death two sons were Muslim, they were excluded from the inheritance, while the third son Dāyib, who was Christian, was recognized as the heir. Dāyib’s later conversion to Islam after his father’s death did not alter the outcome, as inheritance rights are established at the moment of death. This ruling also set aside any debate regarding the sincerity of conversion. Whether an individual experienced a genuine spiritual transformation after the father’s death or only adopted Islam formally, the law did not grant retroactive rights. In this way, al-Khalīlī closed the possibility of manipulating inheritance through conversion, thereby preventing both legal uncertainty and potential social tensions (

al-Khalīlī n.d., vol. 2, p. 8).

From the perspective of intersecting identities, this fatwā clearly reveals the tension between religious status and family bonds. Three different forms of belonging operate simultaneously in this case: religious identity, family ties, and the economic position shaped by inheritance rights. By emphasizing the legal maxim that “inheritance is fixed according to the status at the moment of death,” the juristic rule redefines the intersection of these three spheres. On the one hand, the sons remain part of the same family as their father; on the other, their Muslim identity excludes them from their father’s estate.

This approach reflects Islamic law’s reflex to safeguard social order. Preventing the use of conversion to manipulate inheritance helped secure the economic boundaries of both Muslim and non-Muslim communities. The fatwā not only resolved the issue of inheritance but also served as a regulatory precedent operating at the intersection of multiple identities gender (male heirs), religion (Muslim-non-Muslim), and family ties (father-on). This intersection illustrates how faith and familial rights were defined through an intercommunal legal boundary.

The practical implications of the fatwās are visible in inheritance cases recorded in the court registers. In one such case, the convert Mustafa b. Isḥāq

4 entered into a property dispute with his uncle, who had been appointed as his guardian after his father’s death, but his claim was rejected due to insufficient evidence. Mustafa alleged that his uncle had seized his father’s estate, which included a considerable fortune consisting of twenty-four horses, fifteen pieces of cloth, six garments, two hundred ducats of gold, two quintars of copper, and two hundred dirhams of silver. One of the unmentioned details, however, was the religious affiliation of Mustafa’s father at the time of his death. The court’s insistence on requiring evidence suggests that Mustafa may have converted only after his father’s passing (

Cohen et al. 1996, p. 269).

If the father was disabled or had died, responsibility for supporting the child was often left to the father’s family, particularly grandfathers and uncles (

Tucker 2000, p. 137). In this case, Mustafa was still a minor at the time of his father’s death and was placed under the guardianship of his uncle. Once he had reached the age of majority (

rushd), he wanted to take ownership of the property that had been left to him by his father. For guardianship was not merely a matter of care but also an economic position. Yazbak notes that children in the Palestinian context who had reached the age of majority petitioned the court to terminate their guardianship (

Yazbak 2001, pp. 136–37). This procedure signified the recovery of both their financial and legal identity.

This case reveals that this person occupied a position that intersected with both his former community and their new social structure. Mustafa had to prove that he had converted to Islam while his father was alive, so the boundaries regarding him were determined by legal procedure.

Children also resorted to various means to prove their rushd. In a case from the Jerusalem court in 1754, twelve-year-old Sayyid Yusuf, who was under the guardianship of his uncle, claimed that he had experienced nocturnal emission (iḥtilām) and thus reached the age of majority, asserting that he no longer required a guardian. The qāḍī, however, ruled that it was impossible for a twelve-year-old to have attained puberty and therefore declared him still a minor. Yusuf nonetheless stated that, if a guardian were to be appointed for him, he wished it to be his grandfather Ismail Efendi. Some notable figures of Jerusalem present in the same case alleged that his grandfather was a corrupt man, yet Yusuf was ultimately entrusted to him (JCR 238/59; JCR 238/73).

In this context, it is essential to note that the distinction between a fourteen-year-old married woman (in the case of Fatma) and a twelve-year-old Yusuf does not reflect a modern judgment, but rather the legal categories employed by the Jerusalem court itself.

These cases suggest that guardianship extended beyond the protection of children and was closely linked to economic interests and struggles for social authority. Yusuf’s claim of early maturity reflected his desire to escape dependency, while the qāḍī’s ruling and the debates surrounding his grandfather’s conduct illustrate that guardianship operated at the intersection of family authority, economic capital, and judicial power.

Another court record from 1783 illustrates the principle in its clearest form. Muḥammad b. Masʿūd al-Maghribī, who had embraced Islam, claimed the inheritance of his deceased aunt Maryam, who had died four years earlier, consisting of two hundred dinars in gold and goods worth three hundred qurush, asserting that it had been transferred to a Jewish waqf. The Jewish communal leader dragoman Murqada responded that Muḥammad had converted to Islam five years after his sister’s death and therefore requested the case be dismissed. The court applied the legal maxim that “a Muslim does not inherit from a non-Muslim” and rejected the claim accordingly. By rejecting the convert’s inheritance claim, the court reaffirmed the principle that conversion could not retroactively alter economic rights, thereby preserving the fiscal autonomy of both Muslim and Jewish communities (JCR, 264/8).

These examples show that while conversion granted individuals a new status within the Muslim community, it simultaneously barred any claim to the property of their former group. This outcome affirms the juristic maxim in practice, illustrating that entry into Islam did not entail material gain and that communal boundaries were protected through legal mechanisms. Both fatwās and court rulings thus prevented the instrumental use of conversion for inheritance, preserving the integrity of intercommunal order.

Courts strengthened this boundary by transferring inheritance to communal leaders or to family members within the same community, thereby consolidating interreligious economic separation through legal mechanisms. In this way, at the intersection of kinship and religious affiliation, economic rights were defined along communal lines, safeguarding the economic rights of both Muslim and non-Muslim groups.

At the same time, the case of Fatma and her former husband, Yasef (JCR, 213/146), together with the 1783 case mentioned above, presents two contrasting scenarios of how conversion influenced property relations within the family. When Fatma, after converting to Islam, demanded her mahr and personal belongings from her former husband Yasef, the Jerusalem sharīʿa court recognized her property rights and compelled Yasef to return the items. Accordingly, the court protected both the religious identity and the economic entitlements of the new Muslim woman.

The same reasoning appears in a fatwā on debt liability. It asked whether a son who had converted to Islam was responsible for his non-Muslim father’s debts. In this case, the inheritance rule operated in reverse. Al-Khalīlī ruled that debt was tied to the original debtor and could not be transferred to the Muslim heir. Socially, the fatwā served two aims: it shielded the convert from economic pressure that might weaken his position within the Muslim community, and it prevented the debts of non-Muslims from entering the Muslim fiscal sphere. Through this logic, fiscal separation and communal boundaries were reinforced. Religious identity, rights, and obligations were thus defined strictly along lines of communal affiliation (

al-Khalīlī n.d. vol. 2, p. 7).

Similarly to the conversion cases recorded in the Jerusalem court registers, another fatwā issued by al-Khalīlī takes the form of a vivid “case narrative” that depicts how the legal and social position of a newly converted woman was safeguarded. After declaring the shahāda, a young woman married a Muslim man in the presence of the Jerusalem qāḍī. The dispute centered on the claims of her former non-Muslim relatives concerning her marriage and especially her right to the mahr. The relatives’ demands were categorically rejected (

al-Khalīlī n.d., v. 2, p. 38).

This fatwā can be evaluated from several perspectives. First, at its core lay the declaration that the converted woman now belonged to the Muslim community. The muftī emphasized that she was among the people of Paradise and that the previous religions had been “abrogated,” thereby confirming with theological language her complete rupture from “the other community.” This rhetoric functioned as a religious justification for her inclusion within the new communal boundary.

Second, the rejection of the former community’s economic and social claims concretized this boundary. The relatives’ demand for a share of the mahr was explicitly declared invalid, and this financial right was affirmed as belonging solely to the woman. In this way, the property and family law of the Muslim community was shielded from the interference of the former group, closing its boundaries to outside influence.

Third, the fatwā’s call upon the political authorities (ūlū al-amr) to safeguard these boundaries underscores that the communal line was reinforced not only through religious discourse but also through legal and political mechanisms. By assigning rulers the duty of “preventing pressure from the former community and protecting the woman,” the boundary of the Muslim community was consolidated at both religious and institutional levels. In doing so, religion here emerges as a multilayered field of identity in which gender, kinship, and financial rights intersect.

In sum, this fatwā indicates that in Ottoman Jerusalem, communal boundaries were shaped through theological affirmations, the regulation of financial rights, the redefinition of family relations, and the protective role of the state. The woman’s conversion was more than a formal transition; it functioned as a public affirmation of belonging that consolidated her new identity while legally severing ties with her former community.

Taken together, these examples show how conversion operated through inheritance, debt law, mahr, and family ties to structure inter-communal relations.