1. Introduction

In late January 1556, a cataclysmic earthquake devastated Shaanxi and neighboring regions of the Ming empire (1368–1644). “The number of officials, soldiers, and people crushed to death and officially reported by name exceeded 830,000… Those not known by name or not yet reported were beyond counting” (

Ming shilu 明實錄 1577). It was one of the deadliest seismic events in recorded history. Within the framework of Ming political culture, such a disaster was far more than a natural phenomenon. It was a “Heavenly punishment” (

tian zai 天災) under the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven (

tianming 天命), a dire portent that could be interpreted as a sign of the emperor’s declining virtue, thereby threatening the very legitimacy of his rule under the Mandate of Heaven (

Jiang 2011;

Feng and Yuxia 2010;

Schneewind 2006). If mishandled, a catastrophe of this magnitude risked not only being perceived as Heaven’s judgment upon an unworthy sovereign but also inciting widespread popular panic or even rebellion

1. The court did issue some relief measures; in the second lunar month of 1556, the throne allocated 40,000 taels of silver for counties under Pingyang Prefecture (modern Linfen and its surrounding regions in Shanxi) and Yan’an Prefecture (modern Yan’an and surroundings in Shaanxi), and ordered partial remissions of the grain tax according to severity (

Ming shilu 明實錄 1577). For scale, this amounted to roughly 0.2–0.3 percent of mid–sixteenth–century central non–agricultural receipts at contemporary commutation rates—hardly a large sum (

Huang 1974). However, the state’s response pivoted toward symbolic and ritual measures designed to manage the crisis’s ideological aftermath. By imperial command, Zou Shouyu 鄒守愚, Left Vice Minister of Revenue, was dispatched to conduct state sacrifices and proclaim imperial rescripts at key cult sites. He traveled to the Temple of the Jiao-Long Spirit (

Jiaolong shenmiao 焦龍神廟) on Mount Nanshen (

Nanshen Shan 南神山) in Wuxiang 武鄉, Shanxi, and the Shrine of Empress Nüwa (

Wahuang ci 媧皇祠) in Hou Village 侯村, Zhaocheng 趙城, Shanxi

2, in order to petition the resident deities.

Shortly after these rituals, commemorative stelae were erected at the sites of sacrifice. These stone monuments bore inscriptions on both their front and back faces, which together form a notable duality. The front (beiyang 碑陽) of each stele is inscribed with a solemn imperial text, a ritual proclamation addressing the deity in the lofty voice of the Son of Heaven, essentially “commanding Heaven” in the wake of disaster. In contrast, the back (beiyin 碑陰) carries a more humble, supplicatory text, which is a prayerful plea in the voice of the imperial envoy and local officials, petitioning the deity for relief. In doing so, a single monument embodies a two-sided textual performance: the front “informs” or even reproaches the god from on high, while the back “implores” the god with humility. This phenomenon raises a central question: do the front and back inscriptions serve distinct functions in the context of disaster rites? In other words, do they constitute a deliberate front–back pairing of “disciplining the divine and appeasing the divine” discourse structure, with the front voice reproaching or instructing the deity, and the back voice entreating the deity?

Scholars have seldom examined this dual textual structure of stele inscriptions in a systematic way. Traditional epigraphic scholarship, especially from the Song through the Qing, prioritized rubbings and treated the obverse inscription of a stele as the primary object for historical and calligraphic analysis. Reverse inscriptions were often ancillary. Until recently, both epigraphic compilations and scholarly studies tended to privilege the stele’s obverse inscription for transcription, rubbing, and analysis, while the reverse was commonly relegated to an appendix, such as donor rolls, colophons, and later addenda, or was often summarized or omitted altogether. This front-centric habit obscured the independent evidentiary and performative value of back-side inscriptions. In fact, the back inscription often possesses a distinct voice, tone, and social role, one that should not be overlooked as merely supplementary. Under the influence of material culture approaches, scholars have treated inscriptions as public texts: media of political communication and memory-making, inseparable from their ritual performance and spatial context. Scholarship has richly analyzed Chinese stelae as public monuments and epigraphic genres

3. Recent scholarship, such as Wang Jinping’s analysis of two 13th-century dual-faced stelae, has begun to address this phenomenon (

Wang 2023,

2025), but a systematic framework has been lacking

4. Building on this material-focused perspective, this study reads the two faces of the stele as an integrated three-dimensional medium and argues that there is a recurrent pattern of paired discourse in late imperial disaster inscriptions: cosmic discipline versus devotional appeasement.

This article contends that the double-faced inscription format on the stelae erected in the wake of the catastrophic Jiajing earthquake of 1556 was no mere quirk of formatting, but a purposeful strategy of ritual communication within the Ming court’s disaster response. In the aftermath of calamity, this approach transformed a chaotic seismic event into a structured ritual discourse that mediated the fraught relationship between imperial authority, divine power, and locals’ expectations. This study examines in depth two such stelae erected after the 1556 earthquake in Shanxi, the Wuxiang Stele of the Jiao-Long Spirit (

Jiaolong shen 焦龍神) and the Zhaocheng Stele of Empress Nüwa (

Wahuang 媧皇), as case studies. Through close readings of their front and back inscriptions, attending to differences in voice, formulaic diction, closure conventions, speaker roles, intended audience, and textual placement, I develop an analytical framework of “epigraphic layering” and “dual voice”. By “epigraphic layering,” I mean that the obverse and reverse faces carry hierarchically and functionally distinct texts, each in a different register. By “dual voice,” I refer to a two-part inscriptional discourse: an imperial edict on the obverse, delivered in a stern, directive register that asserts the Mandate of Heaven, and a supplicatory prayer on the reverse, delivered by the envoy and co-signed by local officials, which tempers and localizes the message. The front face reasserts cosmic order and imperial authority, effectively disciplining the divine, while the back voice addresses communal emotion and offers spiritual solace, thus appeasing the divine. In essence, the two faces provided a coordinated dual voice for crisis ritual, and further evidence suggests that this two-sided strategy had broader currency in late imperial epigraphic practice. Whereas Wang analyzes a single pair of dual inscriptions from the 13th century

5, the present study develops a broader theoretical model of epigraphic layering and applies it to the major 1556 case, thereby extending the analysis to late-imperial disaster management.

This study makes three main contributions. First, in the field of epigraphy, it advances the concept of epigraphic layering in imperial stelae dedicated to deities in the earthquake and similar cases, highlighting how distinctions in voice, mood, formulae, intended audience, and closure map the stratification between obverse and reverse texts. This moves beyond front-focused approaches and foregrounds the distinct historical and religious significance of backside inscriptions rather than treating them as mere appendices. Secondly, in the realm of disaster politics, it identifies a Ming-period discursive tactic for managing “Heavenly punishment”: pairing a directive imperial voice on the front with a placatory envoy voice on the back, a coupling that helped balance Heaven’s mandate and imperial accountability. This finding clarifies how ritual language underwrote dynastic legitimacy, illuminating the communicative strategies deployed by the court in times of catastrophe. Thirdly, from a ritual-anthropological perspective, it shows how, within the negotiated space of the temple, the juxtaposed front and back texts mediated between state liturgy and local belief. The double-faced stele thus functioned as a deliberate medium in which the state mobilized material form and textual layout to resolve social crises and restore cosmic order.

2. Part I: The Stele of the Jiao-Long Spirit

In the second month of Jiajing 35 (1556), the court dispatched Zou Shouyu as an imperial envoy to Mount Nanshen. His mission was to perform an imperial sacrificial ritual (jiao 醮) to the local deity known as the Jiao-Long Spirit, beseeching peace and stability.

Who is the Jiao-Long Spirit? The Jiao-Long Spirit was a regional rain-and-water deity whose cult anchored drought-relief and calamity rites in southern Shanxi. In the Song, it received the ennobling title “King of Manifest Beneficence” (

Zhaoze Wang 昭澤王), and under the Ming, it was further recognized explicitly as the “King of the Sea Watercourse” (

Haidu Wang 海瀆王), a formulation that situates the god within the empire’s hydrological pantheon and links him to rainmaking efficacy (

Wei 1638). There are a substantial number of inscriptions concerning the Jiao-Long Spirit at Mount Nanshen (

Li 2000) indicating the deity had become a focal node of local governance, ritual mobilization, and memory

6.

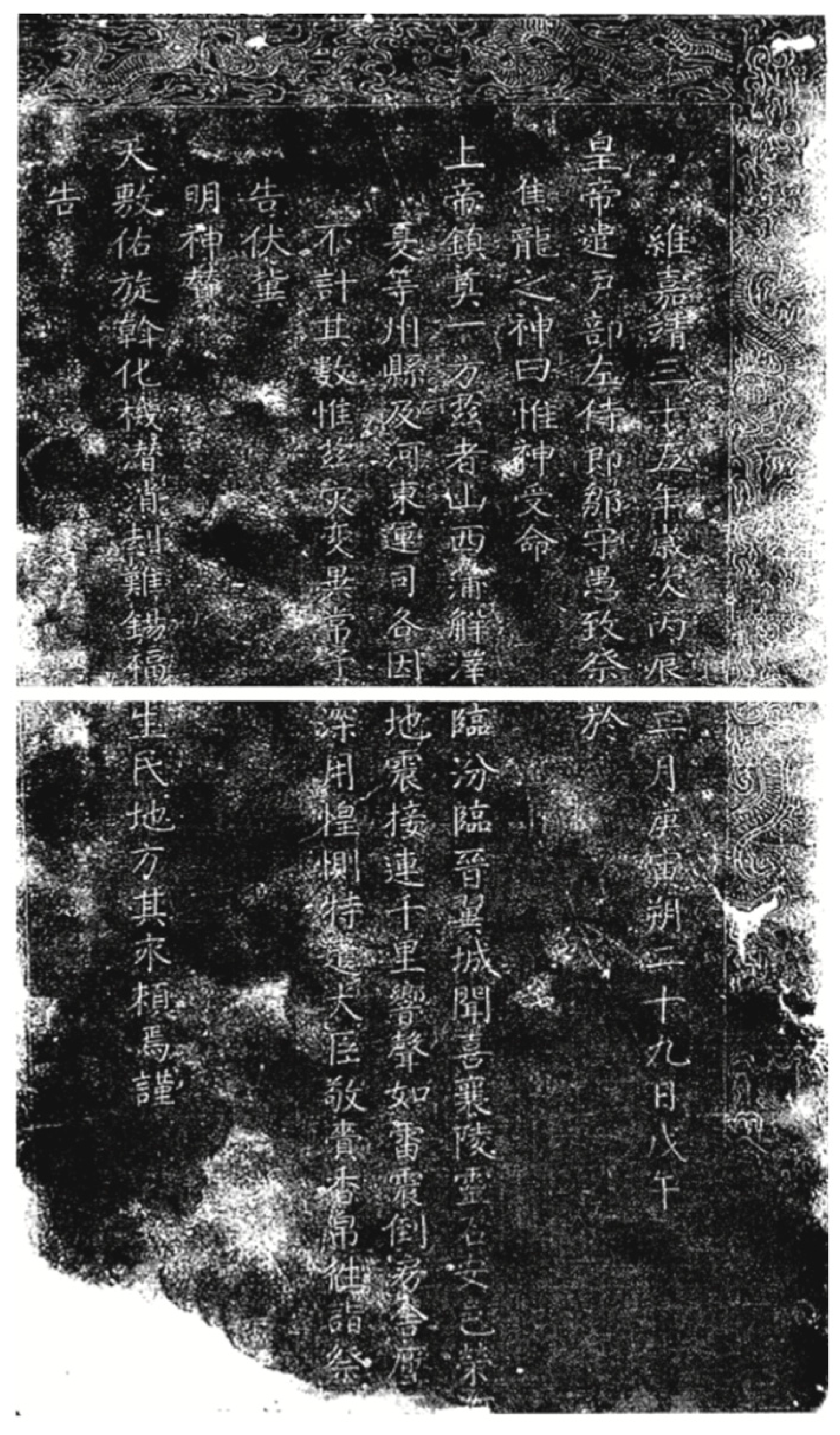

The content of this ritual offering was inscribed on a stele at the Temple of the Jiao-Long Spirit, with text engraved on both the front and back faces. The front side of the stele carries the Imperial Edict sacrificial text addressed to the Jiao-Long Spirit, issued in the emperor’s name and read aloud by the envoy during the ritual. The back side contains the envoy’s own prayer text to the deity, a supplicatory oration delivered by Zou Shouyu on site. The front inscription consists of 10 lines of 29 characters each, approximately 290 characters total, and the back inscription consists of 14 lines of 34 characters each, around 476 characters (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). From the rubbings, the front and back sides were likely brushed by one hand—plausibly Li Shike 李世科 named on the backside. Column alignment and character pitch are tightly regulated on both sides: the module, slightly lifted centers, and ductus match. Distinctive treatments recur: the radicals “礻”, “雨,” and “忄” are compressed left with identical entry and exit strokes; verticals end in the same short outward tick; hooks and turns share angle and pressure–release. As both texts pertain to Zou Shouyu’s mission, a single scribe would imply an integrated project, with both sides cut in one carving campaign.

However, the two texts differ markedly in speaker identity, audience, tone, narrative frame, and signature structure. The front text is issued in the name of the imperial court, spoken by Zou on behalf of the emperor, and exemplifies the imperial power speaking down to the deity in a formal, admonitory mode. In contrast, the back text is a prayer presented by the envoy in his own capacity, using the humble voice of a servant imploring the deity for mercy on behalf of the people. Together, they form a complementary dual voice addressing the crisis.

Below is the full text of both the front and back inscriptions of the Jiao-Long stele. The front is the imperial offering to the Jiao-Long Spirit at Mount Nanshen, titled “Stele of the Emperor’s Offering to the Jiao-Long Deity at Mount Nanshen” (Nanshen shan huangdi zhiji Jiaolong shen bei 南神山皇帝致祭焦龍神碑), and the inscription reads:

On the 29th day of the second month in the 35th year of Jiajing, His Majesty the Emperor dispatched Zou Shouyu, Left Vice Minister of the Ministry of Revenue, to present sacrificial offerings to the Jiao-Long Spirit. The imperial proclamation to the deity reads as follows:

“O God, you have received the mandate of the Lord on High to watch over and settle this region. Recently, in Shanxi, the prefectures and counties of Pu, Xie, Ze, Linfen, Linjin, Yicheng, Wenxi, Xiangling, Lingshi, Anyi, Ronghe, Gaoping, Ruicheng, Xia, along with other counties, as well as the Hedong Transportation Commissioner’s office, an area spanning a thousand li, have all been struck by an earthquake. The rumbling sounded like thunder. Houses collapsed, crushing an untold number of people to death.

This calamity is extraordinary and uncanny. I am deeply grieved and apprehensive. Therefore, I am specially dispatching a high minister, reverently bearing incense and silks, to come and offer sacrifices and make an admonishment at your shrine. I humbly hope that you, illustrious Spirit, will assist Heaven in spreading blessings: set the heavenly mechanism aright, quietly dispel this catastrophe, grant fortune and well-being to the common people, so that this region may forever depend on your protection. Respectfully admonished”.

維嘉靖三十五年歲次丙辰二月庚寅朔二十九日戊午, 皇帝遣戶部左侍郎鄒守愚致祭於焦龍之神曰: “惟神受命上帝, 鎮奠一方。茲者山西蒲、解、澤、臨汾、臨晉、翼城、聞喜、襄陵、靈石、安邑、榮河、高平、芮城、夏等州縣及河東運司, 各因地震, 接連千里, 響聲如雷, 震倒房舍、壓死人民不計其數。惟茲災變異常, 予深用惶惻, 特遣大臣敬賫香帛, 往詣祭告, 伏冀明神: 贊天敷祐, 旋斡化機, 潛消劫難, 錫福生民, 地方其永賴焉。謹告!”

7.

The reverse side is Envoy Zou Shouyu’s Prayer to the Jiao-Long Spirit, and it reads:

On the 29th day of the second month of the 35th year of Jiajing, I, Zou Shouyu, Left Vice Minister of the Ministry of Revenue, reverently led Deputy Envoy Wang Lai and Commander Wang Yu in offering an animal sacrifice, fine wine, incense, and silk at the altar of the Jiao-Long Spirit. We declared:

“The Son of Heaven, enlightened and sagely, occupies the throne between Heaven and Earth and thereby cares for both gods and men. Toiling with concern from dawn to dusk, he strives to achieve perfect governance and transformation. Now, an extraordinary phenomenon, this earthquake, has occurred beyond the ordinary course of events, and His Sacred Majesty’s heart is deeply pained by it. He fears that the spirit may not be at peace in its abode. Not considering me unworthy, His Majesty urgently dispatched me to announce this to the spirit. Could it be that this sudden upheaval was fated and thus unavoidable? May the spirit refrain from alarm or anger!

Moreover, His Majesty knows of the spirit’s manifest efficacy in this land and regards me as one who faithfully serves the divine. He therefore bade me offer earnest prayers with utmost sincerity, entreating the spirit in hope of receiving a sign of favor. We beseech you to harmonize yin and yang, to summon beneficent clouds and rain, to make the five grains prosper in abundance, and thereby bring health and order to our people. Surely these blessings lie within the spirit’s power, may the spirit not begrudge them! I, Shouyu, foolish and insignificant as I am, now present these meager offerings, daring to implore the deity’s grace. I earnestly hope you will accept my words as sincere. Thus, may I thereby, above, gladden the Imperial heart, and below, bring harmony to the people, so that this mission will not have been undertaken in vain. If by relying on the spirit’s aid we avert further misfortune, will not the spirit thereby shine in eternal glory in the days to come? May the spirit examine and heed this plea!

Please accept this offering”.

Stele erected by Acting Magistrate Wang Jiren of Wuxiang, the Vice-Prefect of Qinzhou, together with Vice Magistrate Liu Dengshi, Instructor Wang Chongdao, and Clerk Sun Shilu. Composed and inscribed by county scholar Li Shike.

維嘉靖三十五年二月庚寅朔二十有九日戊午, 戶部左侍郎鄒守愚謹率副使汪來、都指揮王玉, 以牲醴香帛致祭於焦龍之神。曰:“天子明聖, 道在位天地而撫神人, 宵旰憂勤, 期臻至化。乃者地震之異, 出於非常, 聖心惻焉。懼神之不安於居也, 不以余為不肖, 亟遣以告於神, 適然之變, 毋亦出於數而不可逃者耶? 神其毋或震驚! 乃又知神之顯靈於茲土也, 以余為善事神者, 亟禱以虔, 請於神, 冀錫之鑒, 和陰陽、興雲雨、蕃登五穀、以康乂我人, 則固神之能也, 神其毋或靳惜! 守愚不揣, 以不腆之羞, 敢用徼惠於神, 幸以余言為信也。俾余藉以上歡宸衷, 下輯民和, 庶幾用茲行。或者托神以逭咎, 而神不亦永顯耀於來茲也乎。維神其鑒之! 尚饗!”

署武鄉縣事沁州同知王繼仁 縣丞劉登仕 儒學訓導王崇道 典史孫世祿 立 邑庠生李世科書

8.

In these texts, the contrast in register and rhetoric between the two sides is immediately evident. The front inscription speaks with the authoritative voice of the emperor. It opens with the formal dating and identification of the envoy, then directly addresses the deity with elevated epithets and ritualistic praise. The emperor’s message frames the deity’s status and duties in an orderly way: “You have received the mandate of Heaven to guard this region,” thus placing the deity’s authority under the Heavenly mandate that legitimizes the emperor himself. The front text then recounts the disaster in factual detail, essentially reporting the calamity to the god as one would formally report to a superior. This serves a dual purpose: it explains to the deity why the ritual is being conducted, and at the same time signals to the public that the court has duly noted the disaster and is taking appropriate action. Finally, the imperial text sets out the petition and closes with “respectfully admonished” (jin gao 謹告). The tone is lofty and imperative: a directive in the guise of a polite entreaty. While couched in respectful terms, the emperor’s words are effectively instructing the deity to fulfill its duty at once.

On the front side of the Jiao-Long stele, this directive shades into admonition: phrases such as “assist Heaven in spreading blessings” and “quietly dispel this catastrophe” carry a commanding undertone, warning the deity against neglect of office. This is what I term as the front voice of admonition, directive speech from the throne to a subordinate supernatural entity. Notably, the Emperor still maintains ritual decorum by using honorifics for the deity, but beneath the deference lies a clear expectation of compliance. Politically, this front-face directive has the effect of shifting some responsibility for the disaster onto the deity. According to traditional cosmology, the earthquake could signal imperial misrule, yet by emphasizing the deity’s duty to protect the realm, the burden of restoring order is partly transferred to the divine realm. In other words, the emperor’s inscription subtly says that he has performed the proper rites, and now it is the deity’s duty to fix this. This is a tactic of responsibility displacement, easing the moral pressure on the throne by framing the disaster response as a task for the deities.

By contrast, the reverse speaks in Zou Shouyu’s own voice, as a humble official, and represents local supplicants. It opens with his name, title, and date, then moves to praise the deity’s virtues and powers by pointing out “spirit’s manifest efficacy” and the deity’s power to “harmonize

yin and

yang, to summon beneficent clouds and rain, to make the five grains prosper in abundance, and thereby bring health and order to our people”. That rhetoric exalts the deity and prepares the plea: having saved the world previously, the deity can save it again. The register is optative and prayerful. Zou repeatedly self-abases, calling himself “foolish and insignificant,”

9 and begs the deity not to consider them unworthy, not to be alarmed or angered, not to begrudge assistance. He also softens the imperial stance: rather than scolding the god, he reports that the emperor was pained and feared the spirit was not at peace, raising the possibility of fate to deflect blame. This approach exonerates the deity while urging renewed protection, promising that by averting harm the god will shine in lasting glory. In effect, the reverse soothes divine feelings and flatters the deity’s sense of efficacy, repairing any tension created by the front side’s imperial admonition. For local worshippers, it is more relatable and consoling than the austere front, and it would not further offend, if the front does, their beloved deity. The envoy pleads on their behalf, explicitly hoping to “gladden the Imperial heart above and bring harmony to the people below,” positioning himself as intermediary between emperor, deity, and community.

Crucially, the reverse is co-signed by local officials. In the Jiao-Long stele, Zou’s prayer is followed by the names and titles of the acting magistrate and county officers who erected the monument, and it credits the local scholar who composed and inscribed the text, firmly rooting the backside in community participation. The front bears no personal signature: it speaks in an impersonal imperial voice. This contrast reinforces the two voices: the front as state proclamation, the back as personal, community-backed testimony. The two sides privilege different publics—a primary, display-oriented public on the obverse and a secondary, more initiated public on the reverse. The front publicly demonstrates that the state has fulfilled its ritual duty while admonishing the deity; the back speaks more intimately to the deity and to the local faithful who circulate around the monument. By splitting the text in two, the Ming court preserves an authoritative façade on the side exposed to the sacred space, while channeling emotive and penitential expression to the reverse, a functional safety valve that complements the front’s austerity.

The Jiao-Long stele thus offers a clear example of the pairing of reproach versus supplication in action. To examine whether this was an isolated case or part of a broader pattern, this study next explores a second stele from the same year’s earthquake, dedicated to the goddess Nüwa, which exhibits a very similar double-faced structure.

3. Part II: The Zhaocheng Nüwa Stele: Dual Discourses Compared

Another significant monument arising from the court’s response to the 1556 earthquake was the Stele of Empress Nüwa, erected at Nüwa’s shrine in Zhaocheng County, Shanxi. Nüwa 女媧 is the primordial mother in Chinese mythology, famed for creating humankind from earth and for “mending the sky” after a cosmic rupture, acts recorded in early classics and analyzed by modern scholarship

10. In Shanxi, her cult coalesced around the Nüwa Temple at Hou Village in Zhaocheng, which enjoyed long-term imperial recognition and local devotion. Abundant stelae document court sacrifices and supplications at this shrine, showing the temple’s role as a regional center for drought relief, earthquake rites, and communal pledges (

Wang 2009). In a province dense with temple networks and public epigraphy, the Nüwa cult linked state ritual to village devotion. Historical records show that in the wake of the disaster, the Jiajing Emperor also sent officials to offer sacrifices at Nüwa’s temple. The stele that resulted from this ritual likewise bears inscriptions on both front and back, following the same dual-voice pattern as the Jiao-Long stele.

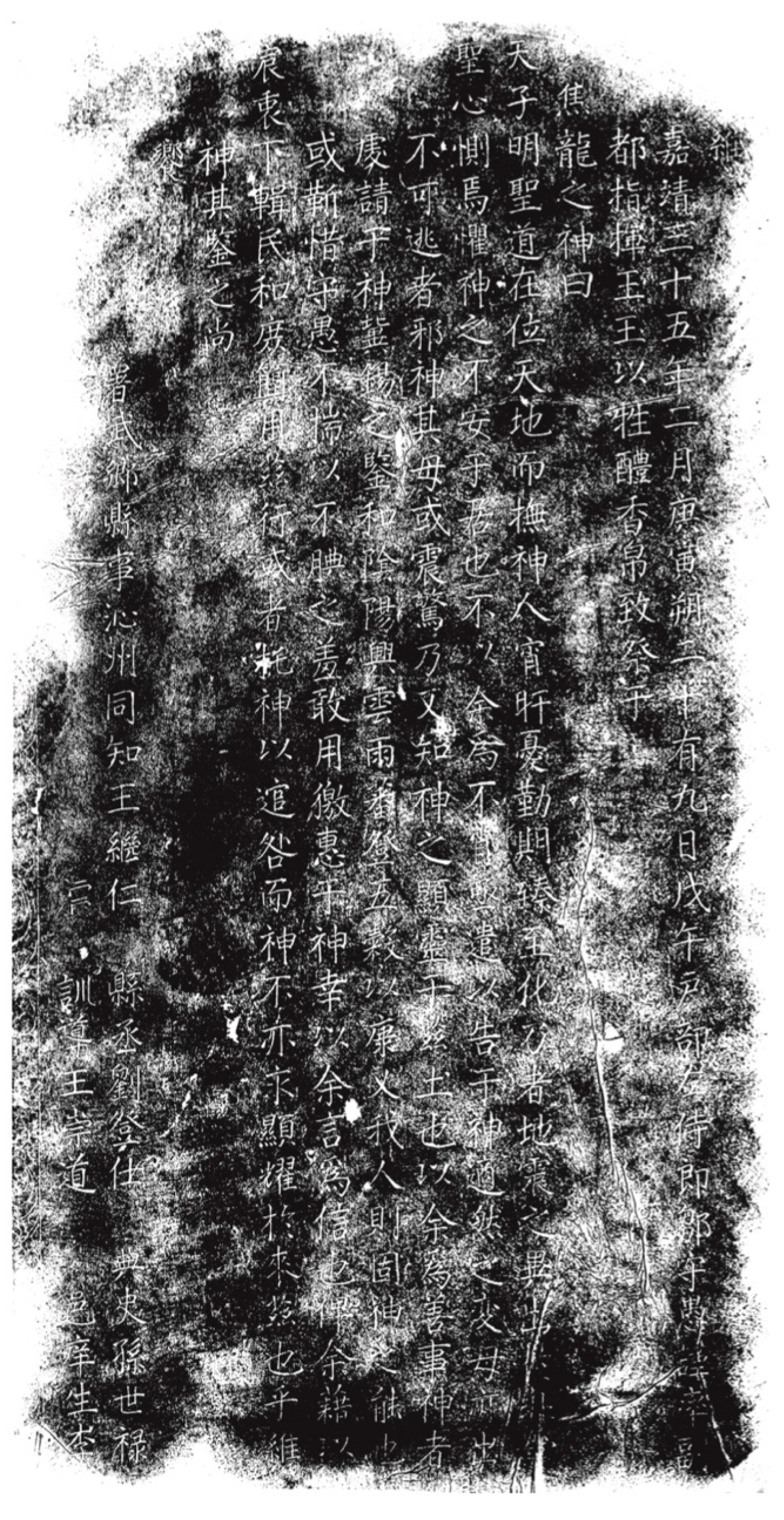

The Nüwa stele’s inscriptions are preserved thanks to later being recorded in the Shunzhi-era

Zhaocheng County Gazetteer. Otherwise, since the original stele was likely erected in 1556, it might not survive today. The front is explicitly an “Imperial Sacrificial Text to Empress Nüwa,” (Yuji Wahuangshi wen 御祭媧皇氏文)

11, dated the 6th day of the third lunar month of 1556 and issued by the Emperor via Zou Shouyu. The back is Zou Shouyu’s own prayer text to Nüwa, dated the 7th day of that month, documenting the offerings and the plea delivered by Zou, along with another official, Wang Lai 汪來, and Assistant Inspector Zhao Zuyuan 趙祖元, who accompanied him. Notably, the Nüwa front and back texts parallel the Jiao-Long texts in structure and tone, confirming that the same dual-discourse strategy was employed. Indeed, a comparison reveals that the Nüwa stele’s two texts correspond almost exactly to the respective roles of the Jiao-Long stele’s front and back, even though the local context and deity differ. Below is the front side of the stele:

In the 35th year of Jiajing, on the 6th day of the third lunar month, the emperor dispatched the Left Vice Minister of the Ministry of Revenue, Zou Shouyu, to present a sacrifice to Empress Nüwa, with the following decree:

“Truly, the divine spirit obeys Heaven’s will and cares for the world, settling the land and protecting the people. With sacred virtue and divine achievements, you have been relied upon throughout the ages. Now, due to a great earthquake, the city walls of three prefectures, including Pu Prefecture, and of twelve counties, including Linfen, as well as the walls of the Hedong Transportation Commissioner’s office, have collapsed and sunk. Houses crumbled down, crushing countless people to death. The provincial officials reported the facts truthfully. I was overwhelmed with alarm and grief at this news. Therefore, I have dispatched a great minister, respectfully bearing incense and silk, to go to your shrine to offer sacrifice and make this admonishment.

I humbly hope that the holy spirit will witness our sincerity and grant protection, silently aid to set the heavenly mechanism aright, and transform this disaster into good fortune, so that the region may be forever under your shelter. Respectfully admonished”.

維嘉靖三十五年歲次丙辰, 三月庚申朔越六日乙丑, 皇帝遣户部左侍郎鄒守愚, 致祭於媧皇氏曰: “惟神奉天撫世, 奠境保民, □□神功, 萬世攸賴。兹因地震, 致將蒲州等三州、臨汾等一十二縣、河東運司城垣陷下, 房舍倒塌, 壓死人口不計其數。守臣據實奏聞, 朕不勝惶惻, 兹遣大臣敬賫香帛, 往詣祭告, 伏冀聖靈鑒佑, 默相化機, 轉災爲祥, 地方其永作庇焉。謹告。”

12.

On the back side is Zou Shouyu’s sacrificial text to the Empress Nüwa:

In the 35th year of Jiajing, on the 7th day of the third month, the Left Vice Minister of the Ministry of Revenue, Zou Shouyu, together with Wang Lai, Deputy Provincial Inspector of Shanxi, and Zhao Zuoyuan, Assistant Inspector, brought sacrificial animals, sweet wine, incense, and silk to offer a sacrifice to Empress Nüwa, and said:

“Truly, the Empress responded to Heaven and became a sage, her spirit equal to that of the gods. She melted five-colored stones to mend the sky and cut off the great turtle’s legs to set up the four pillars. At the dawn of creation, such a deed was rarely seen, and nothing of its like is recorded in the chronicles. Furthermore, her divine transformations are said to number seventy, and the miraculous changes wrought by her spirit cannot be fathomed! As for the story that she first crafted the reed organ to imitate the sounds of nature’s music, that indeed is a small matter; it is too trivial to be reported to the High One (Supreme Above) in this solemn rite.

Recently, an extraordinary earthquake has struck the regions of Shanxi and Shaanxi. The Son of Heaven, saddened at the thought of Nüwa’s toil in smelting stones and cutting the turtle to save the world, promptly dispatched me to earnestly pray to the Empress for relief. I, Shouyu, reverently and with sincere humility, pray that you will clearly see our devotion, even though our plea is conveyed only through these material offerings. If the Empress’s divine spirit truly has such efficacy, who can say that a deity only wanders in Heaven and roams across the Earth without responding? Surely, your spiritual presence cannot remain vague or indifferent.

Now, we humbly hope that you will secretly assist through unseen workings so that this calamity may quickly be dispelled. In this way, you will help our country enjoy enduring peace and long-lasting order. Indeed, without the Empress’s aid, such a splendid state of lasting peace could not be achieved. We make this plea with the utmost respect and without irreverence. May the Empress heed our petition. Please accept our offering”.

維嘉靖三十五年三月七日, 户部左侍郎鄒守愚, 謹率山西按察司副使汪來、僉事趙祖元, 以牲醴香帛, 致祭於媧皇氏曰: “維皇應天作聖, 與神侔靈, 煉石補天, 斷鰲立極, 肇開辟而罕有, 考載籍而靡聞。矧又神化之至於七十, 而靈變之不可測也乎!乃若首作望簧, 效聲天籟, 固其細者, 非所以譖於上也。邇者山、陝地震之變出於異常。天子惻然於煉石斷鰲之思, 亟遣以禱於皇。守愚敬□□誠仰祈昭鑒, 乃響之囿於形也。皇若是乎其靈也, 孰謂神之行乎天而游乎地也。皇獨不可恍惚其靈, 於今乎幸其潜贊機緘早消□矣, 用相我國家久安長治之盛, 信非皇而弗能也。以是弗瀆, 維皇其聽之。尚饗。”

13.

The front inscription is an imperial sacrificial text to Empress Nüwa, issued in the emperor’s name and delivered through Zou Shouyu; the back contains Zou’s own prayer to the goddess. The pair corresponds closely in structure and tone to the texts on the Jiao–Long stele. On the front, the imperial voice first affirms Nüwa’s Heaven–bestowed charge to “settle the land and protect the people,” then reports the earthquake’s devastation in factual terms before issuing a courteous injunction that the holy spirit “witness our sincerity,” aid the turning of fate, and turn calamity into blessing. The piece ends with the closure “respectfully admonished”.

On the back, Zou opens with learned praise of Nüwa’s mythic feats, smelting five–colored stones to mend the sky and severing the turtle’s legs to raise the four pillars, explicitly linking that cosmogonic labor to the present crisis and to the emperor’s decision to dispatch him. He then advances a plea at once reverent and insistent, gently challenging the goddess to manifest efficacy rather than remain aloof, and asking for hidden assistance to disperse the calamity and secure enduring peace. The prayer closes with the liturgical formula “Please accept our offering,” confirming the same front and back pattern already seen on the Jiao–Long stele.

Comparing the two stelae, a consistent pattern appears. Both Nüwa and Jiao-Long front texts are formal imperial addresses: they follow the ritual memorial format by listing date, envoy introduction, and announcement of sacrifice, then praise the deity’s cosmic role, such as “received the mandate of Heaven to care for the realm” and “settling the land, protecting the people,” then detail the disaster as the occasion, and finally state the petition and conclude with a respectful admonishment, underscores imperial authority and finality of command. Both end with “respectfully admonished,” giving the front an official, serious, close-ended feel, like an imperial proclamation that has been submitted. The tone is dignified and restrained. The back texts, in both cases, read more like personal supplications or liturgical prayers: they incorporate narrative, such as myth and circumstance, emotional appeals, and explicitly humble language. Both back texts end with “please accept our offering,” which is a deferential and open-ended closure, fitting a prayer rather than an edict.

The linguistic and structural dichotomies observed across both the Jiao-Long and Nüwa stelae are too consistent to be coincidental. To illustrate succinctly the differences, the following comparison table highlights key features of front and back texts (

Table 1):

Obviously, the front side of these ritual stelae consistently articulates the imperial stance: it is disciplinary and normative, placing the deity within the state’s cosmological order and asserting that the disaster is being handled through proper ritual, while also insinuating that the deity bears a share of responsibility. The back side voices the local ministerial stance. It is conciliatory and hopeful, softening the front’s severity and reinforcing the reciprocal bond between community and gods by promising continued offerings and acknowledging miracles. This duality enables the stele to “speak” to multiple constituencies, the gods, the bureaucracy, and the local faithful, each in its own register. The two faces operate as a coordinated sequence: the emperor’s stern injunction establishes duty, and the envoy’s supplication follows to affirm trust and request aid, forestalling divine offense. For observers, the pairing displayed both authority and humility, a balance central to legitimacy under the Mandate of Heaven.

In sum, the Nüwa stele corroborates the pattern observed at Jiao-Long: “front admonishes, back beseeches” became a reproducible template in Jiajing’s earthquake response. With this pattern established, this study turns to a broader analysis of why the dual structure proved effective and how it functioned within Ming disaster management.

4. Part III: Multiple Functions of the Two Voices: Shifting Blame, Soothing Hearts, Rebuilding Order

Across the two earthquake stelae discussed above, the front and back inscriptions each fulfilled a deliberately distinct role in the wake of catastrophe. The front delivered an authoritative imperial admonition to the deity; the back offered a conciliatory plea on behalf of the people. Deployed together, the Ming court struck a careful equilibrium in managing the political and social fallout of the 1556 earthquake.

The front (yang) is the imperial voice, aiming to reassert order and shifting responsibility. The front of each stele presents the emperor’s official pronouncement to the deity, written in a dignified, imperative tone. This yang-voice written on the front served a crucial political function: it reasserted cosmic order and subtly shifted the burden of responsibility away from the throne. While a natural disaster can be interpreted as a Heavenly warning that could undermine an emperor’s legitimacy if not properly answered, the Jiajing Emperor’s front inscriptions met this challenge by highlighting his proactive virtue, detailing how he promptly performed solemn rituals and dispatched high ministers to aid the people, while pointedly reminding the god of its own Heaven-bestowed duty to safeguard the realm. Essentially, the emperor used the front text to command the deity to do its part. For example, the imperial edict to the Jiao-Long Spirit explicitly invokes the deity’s Heaven-bestowed role to “watch over and settle this region” and to “protect the people,” and explicitly admonishes the spirit to fulfill the duty. By reproaching the god in this manner, the emperor deftly reframed the narrative of causality: if cosmic order was disrupted by the quake, the fault lay at least partly with the local deity’s negligence rather than with imperial misrule. Through this ritualized displacement of blame, the sovereign’s moral authority under the Mandate of Heaven remained intact.

In effect, the front voice proclaims to the public that the state has duly done its part; if peace returns, it vindicates imperial virtue. If not, likely then the implication was that the deity had failed in its office. This tactic of shifting blame to the deity echoes earlier imperial practices of demoting or rebuking gods after disasters, as seen in Ming and earlier dynasties

14. Moreover, by publicly issuing a firm edict to a deity, the emperor projected an image of control amid chaos. He presented himself as an authoritative guardian who could still command unseen forces despite the upheaval, and this reassertion of hierarchy was vital to restoring public confidence. In short, the stele’s front face functioned to reprimand the god in order to protect the sovereign, preserving the emperor’s status as Heaven’s mediator. Notably, the Emperor showed little penitence toward the subordinate spirit in these public texts; he remained the central moral pivot actively directing both people and gods toward harmony, rather than passively accepting blame for Heaven’s wrath.

The back (yin) voice, by contrast, is a local, supplicatory register that softens the message and comforts the populace. As noted above, for local communities in southern Shanxi, the Jiao-Long Spirit and Nüwa were pivotal ritual authorities for rainmaking, agriculture, and post-disaster restoration. Their cults also sustained local memories and everyday ritual practice. These back inscriptions are authored by the imperial envoy and couched in a humble, supplicatory tone, resonating the local voice. This complementary voice served as an emotional balm for the community. In contrast to the stern admonitions on the front, the back text is empathetic and conciliatory, effectively translating the state’s response into terms local believers could embrace. After a disaster, people look for meaning, comfort, and reassurance, and they often turn to familiar deities for solace. An unmitigated imperial scolding of those gods might have struck local sensibilities as discordant or even offensive. The Ming authorities seemed to avoid letting the emperor’s reproach stand as the final word. By appending the envoy’s gentle prayer on the back, they immediately tempered the overall tone of the communication. Thus, anyone who read or heard both sides would see that the emperor’s admonition was promptly balanced by the envoy’s reverent praise and earnest plea, reaffirming the deity’s honor and compassion in the eyes of the faithful.

Zou Shouyu’s prayer to the Jiao-Long Spirit illustrates this dynamic. In that back text, he praises the spirit’s miraculous efficacy, avoids blame for the catastrophe, suggesting the earthquake was fated and unavoidable, and fervently entreats the deity’s aid. He even vows that if the spirit helps the people, the regime will glorify the temple in return, promising that the deity will “shine in eternal glory in days to come”. Such assurances told what the local devotees most needed to hear—that their beloved god was still respected by the court, that the state would continue to honor its cult, and that officials shared in the people’s piety and grief. The back inscription soothed popular anxiety and preserved religious loyalty by humanizing the state’s response. The imperial envoy presented himself as a fellow sufferer and supplicant, fearful, earnest, and self-effacing in his appeals, presenting himself almost as a prostrate supplicant. By calling himself “unworthy” and imploring the deity as a child would implore a parent, he signaled that the state shared the people’s fears and hopes. This approach reassured the populace that their rulers understood their hardship, uniting the people’s prayers with the state’s own. By asking the god for help and addressing the community’s spiritual needs, the reverse text helped to defuse potential anger and despair. It also turned crisis into a chance to renew the usual exchange between society and the divine under imperial sponsorship: officials pledged continued reverence and support for the cult, and in return implored the deity to keep protecting the people. The backside often listed the local officials and elders who sponsored or witnessed the rite, giving community leaders a visible stake in the recovery narrative. And because the stele’s reverse often faced the temple’s inner sanctum, it remained a focal point in subsequent ritual observances. Over time, later miracles, donations, or temple renovations might be recorded around it, weaving the earthquake episode into the temple’s living memory. Thus, the gentler back voice made the disaster story participatory rather than imposed, and it helped to rebuild social cohesion at the grassroots.

Together, these two voices, one rigid and one pliant, allowed the Ming state to ritualize the disaster and steer the recovery toward restored order. This dual-pronged discourse addressed both the cosmopolitical implications of the earthquake and the psychological needs of the populace. Social theorists observe that public rituals are often essential after calamities to create meaning from chaos and to alleviate collective fear

15. Public rites performed in times of shock work to re-articulate social relations and rebuild solidarity, integrating different social levels and constituencies

16. The Ming response to the 1556 catastrophe, embodied in its double-faced stelae, can be seen as a distinctly Chinese iteration of this principle. On one face, the ritual text imposes an interpretive order: Heaven sent a warning, the emperor responded with proper virtue, and now the gods are charged to aid, framing the calamity as comprehensible and manageable within the cosmic hierarchy. The front text voices confidence that misfortune can be turned into auspicious fortune, implying the disruption is temporary and can be corrected through proper devotion and rites. The reverse text acknowledges grief and uncertainty, then channels those emotions into hopeful prayers for renewal, pleading for beneficent rain, abundant harvests, protection from further harm, and so on. In other words, fear and trauma are systematically converted into petitions and vows.

The very act of engraving these paired texts in stone at a temple, a sacred public space at the heart of the community, gave material permanence to this narrative of recovery. The stele became a monument that could be repeatedly “re-read” for reassurance that the disaster had been properly addressed. It monumentalized the event not just as a tragedy, but as a moment of collective supplication and imperial concern. This produced a form of symbolic healing: villagers could point to the stele and recall that the emperor, through his envoy, had acknowledged their suffering and that their gods had been officially entreated to secure their future. That memory, in turn, helped restore a sense of cosmic and social order after the upheaval. The front voice reaffirmed that the moral cosmos remained intact, and proper rites had been performed, while the back voice provided catharsis by expressing sorrow and hope, allowing communal grief and aspirations to be sanctified within an official ritual framework. Together, the two inscriptions converted raw trauma into shared memory and hope, easing the psychological strain and reinforcing a communal consensus of the disaster’s meaning. This approach strongly resonates with Émile Durkheim’s insight that collective ritual is vital to society’s recovery from disturbance (

Durkheim 1995): by publicly inscribing both a firm reaffirmation of values and a compassionate response, the community reasserted its core beliefs and achieved a kind of collective relief. The Ming state’s epigraphic strategy exemplified this dynamic. The stele served as a point of convergence for imperial authority, divine will, and popular piety, all finding a new equilibrium after the shock. In the end, the earthquake’s threat was ritually contained and integrated into a broader narrative of harmony between Heaven and the Earth.

5. Part IV: Public Text Space

Before examining the broader implications of this dual-text format, it is worth noting that double-faced stelae were not an invention of 1556 but had notable precedents in earlier periods. At the Empress Nüwa shrine in Zhaocheng, for example, an imperial stele erected in the eighth month of the eighth year of the Hongzhi era (1495) already carried texts on both faces (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The front bore the formal imperial sacrificial message, titled “Imperial Sacrificial Text to Empress Nüwa” (

Yuji Wahuangshi wen 御祭媧皇氏文)

17, while the back preserved “Record of the Sacrifice to Empress Nüwa by Imperial Command” (

Fengzhi ji Wahuang ji 奉旨祭媧皇記) by the envoy Wang Jin’s 王進 pleading for rain, a rhymed, locally inflected plea, a register entirely different from the stately edict on the front

18. This indicates that, by the late fifteenth century, the stele’s backside had become an accepted space for a freer, more locally inflected, complementary voice alongside the official front text. Even earlier, the same shrine underscores this pattern. In the sixth year of the Kaibao era (973), the Song court erected the monumental stele, titled “Stele Inscription and Preface for the Newly Rebuilt Nüwa Temple of the Great Song” (

Da Song xin xiu Nüwa miao bei ming bing xu 大宋新修女媧廟碑銘並序), a classic state inscription by Pei Lize 裴麗澤 and Zhang Renyuan 張仁願

19. Over three centuries later, in Hongwu 7 (1374), Zhang Mengjian 張孟兼 added a “Back Inscription” (

beiyin ji 碑陰記) on the reverse that recorded epiphanies and issued local protective rules, such as “prohibit the gathering of firewood and timber near the sacred site”

20. Such precedents, documented in local gazetteers, show that inscribing dual texts was an established epigraphic practice well before Jiajing’s time. In fact, this pattern is not rare on stelae of late imperial China. The innovation in 1556 lay in how creatively this existing medium was deployed to meet an extraordinary crisis.

Another way to understand this two-sided stele system is as an interactive platform mediating among three realms: the emperor, the deity, and the people. By virtue of its dual inscriptions, each monument set up a triangular dialogue. The front and back faces effectively functioned like two stages of a single ritual drama: the front face, often oriented toward the public space of the temple courtyard, presented the Emperor’s voice addressing the deity in view of the populace, while the back face, typically facing the inner sanctum, presented the local community’s voice, via the imperial envoy, addressing the deity in a more intimate register. In effect, the stele allowed for a negotiated exchange in which imperial authority, divine will, and popular piety all had a role. This triangular configuration can be broken down into three interrelated relationships:

1. Emperor and Deity: Through the front inscription, the emperor, speaking through his envoy, honors the deity with a formal rite and simultaneously charges that deity with the task of restoring order. This is a public statement from the state to the god, and it implicitly assures the people that the gods have been duly directed to set things right.

2. Deity’s Response: Although the deity remains silent, it is expected to respond by granting the requested relief. If subsequent events proved favorable, such as aftershocks subsiding, good rains and harvests, both the state and the deity could claim credit. If not, the groundwork was laid to suggest that the deity had likely not been sufficiently appeased or was not performing its role, without directly blaming the emperor. Importantly, the back text’s flattery ensured the deity’s honor was maintained as it was implicitly put on notice.

3. People and Deity via the envoy: The back inscription represents the locals’ voice conveyed through the imperial envoy. It affirms the emperor’s solicitude for his subjects while expressing the community’s devotion and plea to the deity. This bridging discourse works in two directions. It signals to Heaven and the local gods that the populace remains pious and grateful, and it assures the people that Heaven, through the local deity, remains benevolent. All of this occurs under the emperor’s auspices. In the end, all three parties appear in agreement, with their roles inscribed in stone in a complementary fashion.

This dual arrangement created a public text space, a single medium that accommodated layered discourses. The earthquake stelae show how one monument could at once serve as an instrument of state ideology and a vessel for local religious expression, without the two realms openly clashing

21. The temple, often described as a negotiated sacred space where imperial authority meets popular belief, was here literally inscribed with a negotiated text: the imperatives of the state and the claims of faith were each given distinct domains on the stone and made to speak to one another

22.

Studies of early Chinese epigraphy and ritual textuality have shown that inscriptions were not merely records; they were performative media that enacted imperial presence and ritual order in space. Martin Kern reads the Qin First Emperor’s stele inscriptions as ritual proclamations carved into strategic landscapes during imperial tours; these texts’ placement bound political authority to sacred topography and scripted ceremonial reading and public display (

Kern 2000). In Kern’s account, the stele’s text, materiality, and emplacement formed a single communicative act, projecting authority while soliciting assent through ritualized language and site-specific visibility. Subsequent scholarship has broadened this insight. Mark Edward Lewis shows how writing itself became an instrument of command and consent in early China (

Lewis 1999), while Dorothy C. Wong traces how the indigenous stele form was adapted in Buddhist contexts to coordinate icon, text, and donor lists, making a single monument carry multi–voiced participation (

Wong 2004). Read together, these studies offer a genealogy for our case: late Ming disaster stelae stand in a long tradition in which epigraphic monuments articulate ritual authority, stage layered address, such as imperial and official alongside communal and donor registers, and bind textual discourse to sacred space. If Kern and Lewis illuminate the performative imperial authority embodied on the front side, Wong’s research reveals the multi–voiced participation inscribed on such monuments. This raises new questions: what do the backsides of the 1556 earthquake stelae express? How did these inscriptions ritualize trauma and stabilize meaning after catastrophe? Here, political scientist James C. Scott’s framework of “public transcripts” and “hidden transcripts” offers a useful theoretical parallel.

Scott uses these terms to describe how subordinate groups often maintain an outward, deferential script in the presence of power, as the public transcript, while reserving a separate, offstage discourse, as the hidden transcript, for their true feelings, criticisms, or resistance, away from the gaze of the powerful (

Scott 1990). In broad terms, the front inscription corresponds to an official public transcript of power, the outward script of authority that emphasizes social order, and the state’s legitimacy with no admission of weakness. The back inscription, in contrast, shares some qualities of a hidden transcript: it is more candid about fear, suffering, and need; it admits the emperor’s distress and the community’s desperation; and it speaks in a pleading, humble tone that would be out of place on the front. However, unlike a typical hidden transcript generated spontaneously by subordinates, this back transcript was deliberately authored by the state’s own agent and made semi-public by being inscribed in stone for the community to witness

23. In essence, the Ming court provided its own “backstage” voice on the backside of the stele.

By orchestrating this dual script, the state managed to convey what could not be openly expressed in the front-stage proclamation. The emperor’s inviolable image was preserved on the front and there is little vulnerability or self-abasement in the imperial edict, while the necessary humility and contrition were voiced through the envoy on the back. In this way, the gods were duly implored, and the people’s suffering was acknowledged, yet the emperor’s dignity remained intact. This arrangement effectively preempted potential criticism. Observers likely found it difficult to accuse the emperor of impiety or callousness, as the back text displayed the earnest concern. The two registers reinforced each other and bolstered both the cosmic and the communal legitimacy of the regime.

Implementing this two-voiced strategy required a capable intermediary at the local level. The imperial envoy Zou Shouyu, in his dual role as the emperor’s agent and as a negotiator with the local community, was pivotal. In many ways, Zou Shouyu functioned as a broker between the state and local religious society

24. The temple and its deity constituted a crucial node in the local authority and belief, and Zou’s task was to align that local spiritual nexus with the aims of the state. He had to carry out the emperor’s mandate by conducting the official ritual and proclaiming the imperial edict. Yet, he also had to reassure the populace and placate their gods to maintain order. The double-faced stelae, therefore, became the textual vehicle that allowed him to perform this balancing act. On the front, Zou spoke with the emperor’s authority, asserting hierarchy and cosmic order. On the back, he effectively “code-switched” into the idiom of local piety, becoming almost a humble supplicant on the community’s behalf. In doing so, he translated the court’s agenda into terms that the local religious culture could accept. Imperial orthodoxy thus was being brokered into the local cult’s idiom. The result was a well-calibrated blend of sternness and solace. This dual inscription produced a unified narrative of disaster response in which the state and the supernatural spirits appeared to work together for the public good. By aligning the official voice on the front with the communal voice on the back, Zou effectively fused imperial authority with local religious legitimacy. Such collaboration between state ritual and popular belief was essential to the recovery’s social success. The populace could see that the emperor’s envoy was not antagonistic to their gods but was instead praying alongside them, and this likely helped to rebuild public trust and restore social order in the aftermath of calamity.

Finally, as noted at the start of this section, the two-sided inscription format that the Jiajing court employed in 1556 was not a sudden novelty but rather a creative adaptation of long-standing epigraphic conventions. Late imperial epigraphy had long recognized the stele’s reverse as a space for supplementary or localized voices. The Nüwa shrine examples of 1495 and 1374 underscore that the Ming court in 1556 was building upon a well-known template. Seen against this background, the Ming response in 1556 did not create a new medium so much as elevate an existing convention to meet an extraordinary crisis. Both of the Jiajing earthquake stelae deliberately partitioned their discourse into a stern, directive front, disciplining the divine, and a conciliatory, supplicatory back side, appeasing the divine. This technique was not by chance, but a creative adaptation of established epigraphic norms to the demands of disaster management. By allocating imperial authority and religious humility to two opposing faces of the stone, the Ming court found a materially simple yet conceptually sophisticated solution to an otherwise intractable dilemma: the emperor needed to both command and express contrition.

6. Conclusions

The dual-voice stelae that were erected after the 1556 Jiajing earthquake reveal how register, ritual, and power were orchestrated to restore equilibrium and social order amid chaos. Through a strategy of epigraphic layering, the court of the Ming Dynasty embedded two distinct, complementary messages on a single stele. One message asserted imperial order, positioning the local deity within that order, and emphasized the god’s subordination to the throne as well as its duty to protect the realm. The other message affirmed reverence for the deity and respect for local belief, which acknowledges the community’s devotional world. This dual inscription strategy was sophisticated and deliberate. Through this balanced approach, the Ming court could navigate the Heavenly warning without undermining the Mandate of Heaven. The emperor’s moral prestige thus could remain intact, while his regret was expressed through a proxy, and the local people’s faith in both state and deity could be enhanced by an inclusive ritual discourse.

This two-sided approach sheds new light on late-imperial disaster management. Earlier scholarship often focused primarily on the stele’s front face, but this study focuses on the crucial role of the largely neglected backside text. The dual-voice stelae reveal that what might superficially be taken as a single public edict is in fact a dialogue, an interplay of voices, inscribed in stone. Theoretically, the Jiajing earthquake stelae exemplify carefully calibrated blending of what James Scott calls the “public and hidden transcripts” (1990). Here, the state itself crafted a public transcript of power alongside a parallel, semi-hidden transcript of regret, thereby preempting dissent and absorbing the community’s voice into the official narrative. At the same time, these monuments were places where central authority and local religious culture converged. The Ming state successfully brokered that encounter by giving each side a voice on the stele. The Ming response to the 1556 catastrophe was not only about practical relief but also about ritual and communicative healing. By literally carving a partnership between Heaven, the emperor, and the human realm in stone, the imperial court attempted to transform a moment of crisis into a reaffirmation of cosmic harmony and social order.

By conceptualizing epigraphic layering, this study encourages epigraphists to treat backside texts not as mere appendices but as integral, stratified components of meaning. By identifying the dual voice strategy, it adds a new dimension to our understanding of state-temple interactions.