Abstract

This paper presents the theoretical and methodological foundations of Living a Life of Meaning and Purpose-C (LAMP-C), a novel quantitative instrument designed to assess meaning-making capacity among emerging adults to be used as part of a battery of assessments for religiosity. Drawing on Constructive-Developmental Theory (CDT) as articulated by Robert Kegan, Sharon Daloz Parks, and Marcia Baxter Magolda, LAMP-C operationalizes complex developmental constructs such as cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal growth. LAMP-C integrates CDT with the Rasch/Guttman Scenario (RGS) methodology, which systematically structures items to reflect incremental developmental complexity. An instrument for assessing meaning-making contributes to the comprehensive interpretation of assessments of religiosity among emerging adults. By framing meaning-making through four facets—ideation, relational awareness, conflict resolution, and sense of responsibility—this paper provides a comprehensive conceptual foundation for measuring growth in meaning-making. The RGS methodology further enhances construct validity by enabling precise, context-specific, and developmentally sensitive assessments across three contexts. LAMP-C bridges the gap between qualitative depth and quantitative breadth in assessing developmental constructs, offering a tool that supports both large-scale applications and nuanced theoretical alignment. LAMP-C establishes a framework for assessing meaning-making while setting the stage for future empirical research (e.g., longitudinal studies) to evaluate religiosity in emerging adults.

1. Introduction

Assessment of religiosity among emerging adults has become increasingly vital as patterns of belief, practice, and affiliation continue to shift in the United States and globally (Arnett 2004; Tong 2025). With growing numbers of emerging adults identifying as religiously unaffiliated (Funk and Smith 2012), researchers have sought to understand not only the extent of this disaffiliation, but also the underlying motivations, spiritual orientations, and evolving expressions of faith. Appropriate inquiry requires frameworks and tools that can capture the complexity of emerging adult religiosity—ranging from traditional religious commitment to individualized spiritual paths and secular worldviews. Rather than measuring institutional engagement alone, contemporary assessments might explore how emerging adults relate to belief systems, religious communities, and personal meaning-making. Assessing religious belief and belonging is challenging in part because religions are themselves complex systems of belief, practice, and membership. Furthermore, how an individual engages with religion can change over time as that individual develops and encounters new life experiences.

There are various understandings of the function and value of religious belief and belonging for meaning-making. Is religion a cultural system that offers meaning through its practices and tenets (Geertz 1973)? Are religion’s myths expressing something essential about human existence (Eliade 1954)? Do religions communicate something true and eternal or are they constructs of social worlds for social cohesion (Berger 1990)? It can be valuable to frame the discussion of religion for various philosophical, political, and anthropological purposes. However, such a discussion is beyond the scope of this paper. Rather, we are considering the individual and their epistemological stance towards religion. By assessing an individual’s meaning-making capacity in conjunction with their location on scales of religiosity, investigators gain insight to the individual’s capacity to make sense of religious practices, religious belonging and religious tenets.

Most often, assessment of religiosity is conducted through a battery of scales, as seen in the recent work on young people in Malta (Galea and Sultana 2025). The 2013 Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality identified sixty-six different scales used in the measurement of spirituality and religion (Hill 2013). There are dispositional scales that measure attitudes and practices, including scales that assess development (Benson et al. 1993; Hall and Edwards 1996; Leak and Fish 1999; Leak et al. 1999). There are functional scales that reflect “how a person’s religious or spiritual life is experienced” (Hill 2013, p 62). Since religious belief and practice can inform moral choice, scales for moral development can prove useful (Rest et al. 2000; Thoma et al. 2013). Finally, because religious belief can be used as a means of making sense of one’s life, scales that assess meaning and purpose (Schnell and Danbolt 2023; Hanson and VanderWeele 2021; Ludlow et al. 2022) and the sources of meaning (Schnell 2009) can be helpful tools.

However, amid all of these scales, there are no quantitative scales that consider a person’s epistemological approach to religion. That is, rather than what is the person’s religious practice, affiliation or belief, such scales would help interpret how they make sense of religious practices, affiliation and belief. How do they use religion to construct meaning? Assessment of meaning-making capacity would provide a valuable window to understanding how religious belief and belonging factors into a person’s life.

Measuring meaning-making is inherently complex and is usually assessed by employing qualitative methods that are inefficient in large-scale studies. We built a quantitative tool to assess meaning-making, one that employs a novel approach to quantify difficult-to-measure constructs: the Rasch/Guttman Scenario (RGS) methodology. Our tool, Living a Life of Meaning and Purpose-C (LAMP-C), comprises three self-report instruments that capture meaning-making capacity among emerging adults. LAMP-C assesses an emerging adult’s “approach” to situations in three different contexts: in school, among family, and with friends. Accordingly, it yields three different quantitative scores that are “specific, interpretable, and actionable” (Ludlow et al. 2020, p. 376). LAMP-C does not include religion as a context, so as not to privilege any particular religion or religious expression. Rather, it provides an assessment of meaning-making capacity to be used alongside various scales on religiosity.

The LAMP-C assessment is the result of combining two different conceptual frameworks. The first is Constructive-Developmental Theory (CDT), which supplies the meaning-making construct the instrument seeks to capture (Baxter Magolda 2001; Daloz Parks 2000; Kegan 1994). The second is the Rasch/Guttman Scenario psychometric approach that guides instrument development (Ludlow et al. 2014, 2020).

As LAMP-C is the first successful attempt at a quantitative assessment of meaning-making, this paper describes its theoretical and methodological foundations. It begins with a discussion of key research contributions concerning meaning-making. Second, it offers a reframing of CDT for the purpose of operationalizing the theory to support quantitative assessment. Third, it describes the Rasch/Guttman Scenario methodology and its role in the development of LAMP-C. Finally, it briefly discusses preliminary findings, identifies next steps, and suggests implications for further research.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Foundations

The literature on meaning-making development comprises a rich tapestry of interconnected ideas that collectively deepen our understanding of human development. All theorists cited below build upon the cognitive development legacy of Jean Piaget (1952) but expand beyond the cognitive domain to explore how individuals construct and evolve their understanding of the world, themselves, and their relationships. Collectively, this is called Constructive-Developmental Theory (CDT). This theory has been instrumental in shaping research that examines how people, particularly in educational settings, navigate the cognitive and emotional challenges of growth, and it could prove useful in the domain of research in religious belief and belonging (O’Keefe and Jendzejec 2020).

Central to CDT is the body of work of Robert Kegan (1982, 1994). Kegan’s theory posits that development is a process of progressively more complex meaning-making, by which individuals move through distinct stages of understanding as they grow from childhood to mature adulthood. Rather than focus on what people know, it attends to how people know; how they see and interpret their world and themselves. His theory integrates cognitive, interpersonal and intrapersonal elements. Kegan’s emphasis on the transformation of meaning-making processes, rather than merely the acquisition of new information or skills, has resonated across various domains, particularly in education and leadership (Kegan and Leahy 2000, 2009).

Sharon Daloz Parks (2000), who studied emerging adults, identified how enhancement in meaning-making impacts and is impacted by cognitive capacity, but also one’s relationships, and “construal of authority” (Daloz Parks 2000, p. 78). She was instrumental in identifying the social and affective aspects of meaning-making, as they had implications for the nature and diversity of one’s relationships, as well as who one trusted as a source of information.

Marcia Baxter Magolda’s (2001, 2009) longitudinal research followed traditional age college students into mature adulthood. Her work has been crucial for understanding how young adults achieve self-authorship, a key developmental milestone, one in which individuals begin to internalize and truly own their values, beliefs, and identities.

James Fowler (1981) contributed to this field with a theory of “faith development” by studying children and adults and their use of religious belief to make meaning in their lives. While valuable for this work, it largely focused on the cognitive development of individuals, and not on the inter and intrapersonal aspects.

Subsequent research has enriched CDT by exploring how development is influenced by narrative identity (McAdams 2013), leadership (Helsing and Howell 2014), social context (Abes and Hernández 2016; Pizzolato 2003), power and privilege (Taylor 2016), and educational practices (King 2009; Stewart and Wolodko 2016; Gwyn and Cavanagh 2023).

All of these studies have involved some form of qualitative interview, such as the Subject–Object Interview developed by Kegan and colleagues (King 1990; Leahy et al. 2011). Qualitative interviews, while highly informative, are problematic for large-scale administration because they are time consuming, both in administration and in interpretation of data. They are usually reserved for small samples. A few self-report questionnaires and instruments have been created to assess self-authorship as it pertains to career readiness (Fallar et al. 2019; Creamer et al. 2010; King 1990). However, these measures have limitations, particularly in their ability to capture the dynamic and developmental nature of meaning-making across contexts. Our goal has been to create a valid, practical, quantitative assessment of meaning-making, drawing on CDT to inform instrument development.

3. Constructive-Developmental Theory and Gradation

As indicated above, meaning-making is not an automatic and necessary by-product of cognition and mental capacity. Indeed, Kegan writes that he is “referring to the person’s meaning-construction or meaning organizational capacities. I am referring to the selective, interpretive, executive, construing capacities … I look at people as the active organizers of their experience” (Kegan 1994, p. 29). As a person develops complexity of mind, or meaning-making capacity, they do not forget or reject what was previously known, but subsume it and organize it in a richer, more complex framework of meaning. The person becomes able to notice more in their world, make better sense of what they see, thereby enhancing their agency. “It is about the organizing principle we bring to our thinking and our feelings and our relating to others and our relating to parts of ourselves” (Kegan 1994, p. 29).

As explained in greater detail below, the Rasch/Guttman Scenario psychometric approach facilitates the operationalization of complex constructs, like meaning-making, by requiring that the construct be broken down into its constituent characteristics, or facets. In the present case, we break down meaning-making into facets through the use of CDT. Following detailed design guidelines, these facets are then combined in specific ways to construct scenarios that describe a character’s possible response to a situation. The situations occur in common contexts in which emerging adults exercise meaning-making. Within a context, the scenarios are incrementally modified to represent gradations of the facets, reflecting different responses to the situations and, thus, different capacities with respect to meaning-making. Further explanation of the scenario development process is given in the next section. For the moment, we offer the warrants for both the facets and their gradation by drawing from our analysis of the theories of Robert Kegan, Sharon Daloz Parks, and Marcia Baxter Magolda. Each facet below will be associated with at least one theorist’s framework. In doing so, we offer a reframing of the theories for the purpose of operationalizing them to facilitate quantitative measurement.

In terms of gradations, the three theorists cited above identify developmental steps in which individuals exhibit qualitatively different capacities for interpreting and responding to their worlds. Kegan, whose framework spans the lifecycle from early childhood to adulthood, identifies five possible (but not inevitable) “orders of consciousness” across the lifespan (Kegan 1994, pp. 314–15). Daloz Parks identifies four “forms” spanning adolescence to mature adulthood (Daloz Parks 2000, p. 90). Baxter Magolda names four “phases,” starting in college and extending into mature adulthood (Baxter Magolda 2001, p. 40). This developmental process typically takes many years and requires the appropriate balance of challenges and support. Kegan is most explicit in claiming that people spend more time transitioning between orders than in stasis at any given order, and that such transitions takes years.1

In view of our focus on emerging adults, we propose five gradations, which we call “positions.” Three positions are based on Kegan’s framework and range from “2nd order,” associated with later childhood and early adolescence, and ending with “4th order,” possible in later young adulthood. We then name two “emerging” positions to distinguish between when a particular “order of consciousness” is first onboarded (emerging) from being more established. Furthermore, our emerging positions create better alignment with Daloz Parks and Baxter Magolda’s frameworks. Table 1 offers a correspondence among the five positions of LAMP-C and the three frameworks offered by these theorists.

Table 1.

Five Positions and Constructive-Developmental Frameworks.

In the following subsections, we identify and describe four facets that we assert reflect the cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal characteristics of meaning-making capacity. They are ideation, relational awareness, conflict resolution, and sense of responsibility. Each of these facets have implications for, or transferability to conceptions of religiosity, as illustrated below. As detailed in the following sections, our facet descriptions and their gradations are grounded in CDT. We describe the most characteristic or default forms of meaning-making of people in the five positions. Individuals at a given moment may respond in ways that reflect positions above or below their default. Furthermore, we offer examples of how these positions might be reflected in religious belief and belonging. These examples are offered as illustrations of how different capacities for meaning-making might be expressed.

3.1. Ideation (Cognitive)

The first facet, or characteristic, of CDT is cognitive ability. Within the field of developmental psychology, Jean Piaget’s work on cognitive development is foundational.2 For the range of development considered here, the gradations of cognitive capacity identified by Piaget are Concrete-Operational, Early Formal Operational (able to recognize and think thematically) and Full Formal Operational (able to recognize and think ideologically). These gradations are reflected in Kegan’s framework: Categorical, Cross-categorical and System-Complex. We represent this range through the five positions in Table 2.

Table 2.

Gradation of Cognitive Capacity for each of the 5 LAMP Positions.

With increased cognitive complexity comes the ability to better recognize and make sense of the world. This is reflected in a person’s ability to recognize their own interior life (e.g., thoughts, emotions, hopes) and attribute similar interiority to others.3 It also means they move from thinking in terms of concrete actions and objects to being able to think about ideas, values, and themes, and potentially being able to think ideologically. Placed within the context of religious belief, those in Position 1 would be able to articulate what the beliefs, norms, and practices of a community are, but are not independently guided by values or concepts embedded therein. This contrasts with those in Position 3, who can recognize and talk about the religious values and beliefs they hold and try to live by, but may be challenged to prioritize among competing values, unless guided by a moral framework that offers such prioritization. Finally, those in Position 5 can prioritize independently among competing values, as they can organize values within a theological vision, ideology or worldview. As Kegan writes, they have “values about values” (Kegan 1994, p. 90). Increased cognitive complexity is also reflected in their ability to recognize the relationships among religious practices, beliefs, values and worldviews or theologies. For example, the concrete knower (reflected in Position 1) can recognize and talk about the concrete practice (e.g., initiation ceremony), but it requires the capacity to ideate (Position 3) to reflect critically and creatively about the meaning behind the practice (e.g., What does it mean to be a member of this community, and how does the ceremony embody that?). This is different from the ability (Position 5) to recognize diverse ideological approaches (e.g., Does an initiation ceremony make someone a member, or does it recognize that someone has been a member of the community?). Similarly, they can increasingly recognize connections between themselves and others, and the mutual impact that is inherent in relationships. These interpersonal and intrapersonal developmental capacities are elucidated in the following facets.

3.2. Relational Awareness (Interpersonal)

The second facet is relational awareness. Sharon Daloz Parks writes, “an underrecognized strength of the Piagetian paradigm is its psychological conviction that human becoming absolutely depends upon the quality of interaction between the person and his or her social world” (Daloz Parks 2000, p. 89). With appropriate challenges and support, it becomes increasingly apparent to the person that they have been and are in relationships with others. It is not just that they are better able to engage in relationships with mutuality, but that they are already beginning to recognize the relationships of which they are a part.

According to Kegan’s framework, the second-order adolescent is unselfconsciously self-interested. They may recognize that others have a point of view, just as they do, but they are unable to “take their point of view and another’s simultaneously” and are likely to “manipulate others on behalf of [their] own goals” (Kegan 1994, p. 30). They do not recognize they have relationships with implicit expectations. While this lack of relational awareness is normal in older children, it is something that they are expected to grow out of as they move through adolescence. Consequently, we think it is appropriate to begin our instrument with Kegan’s second order as Position 1.

The move towards Kegan’s third order brings a capacity to recognize relationships and begin to take others into consideration. This happens first in a tacit manner (Position 2), whereby a person becomes generally aware of social pressures and expectations, such as peer pressure or family expectations. In time, and with encouragement (Position 3), tacit belonging is replaced by conscious alignment (or disaffiliation), whereby one takes on and can even become a proponent for the values and expectations of particular relationships. Daloz Parks names this as “Conventional” belonging, “marked by conformity to cultural norms and interests” of the relationship or community (Daloz Parks 2000, p. 92). With this capacity there is a presumption of similarity within a group and strong boundaries, thus eliciting a self-imposed expectation to live within those boundaries.4

Position 4 marks a shift in one’s sense of dependence on and obligation to one’s relationships. It reflects what Baxter Magolda names as the “Crossroads.” In her research she found that people came to a crossroads because following the “external formulas” of their relationships “did not produce the expected results” (Baxter Magolda 2001, p. 93). This prompted the opportunity to name their own needs and perspectives, even if doing so might risk the relationship. In Position 4, one is beginning to risk sharing one’s perspective as distinct from another’s (e.g., a valued person’s or group’s perspective). By the time they are in Position 5 they are more confident in claiming their own voice and have a greater ability to recognize and appreciate diversity of perspectives within their communities. Rather than being bound by the expectations of a relationship, an individual in Position 5 can have a “relationship to the relationship” (Kegan 1994, pp. 91–92). Furthermore, they “can sustain respectful awareness of communities other than [their] own” (Daloz Parks 2000, p. 100). We represent the range in relational awareness through the following five positions in Table 3.

Table 3.

Gradation of Relational Awareness for each of the 5 LAMP Positions.

Within a religious context, a person in Position 1 would not recognize “religious belonging” as such, even as they may attest that they “go to” church or synagogue or temple, recounting the things done there. They “belong” because someone else requires it (parents) or they find it enjoyable. By contrast, those at Position 3 can demonstrate conscious alignment with a religious community, its values and norms, and feel confident expressing perspectives that align with the community. They can be deeply loyal to the community and what it stands for, teaching others about it. Yet they tend to see their religious community as monolithic and expect others to experience it as they do. They perceive those who express the religious tradition differently as wrong or no longer part of the community. Those in Position 5, however, recognize greater diversity of expression and belief within the group, and appreciate that diversity as legitimate if it fits within the wider worldview of the community. They have confidence in articulating divergent perspectives, even as they feel deep commitment to the community. To be clear, the above information is simply illustrative of how these positions might be used to interpret an individual’s religious engagement; they could also be used to interpret an individual’s lack of religious engagement.

3.3. Conflict Resolution (Intrapersonal)

In this facet, we recognize some alignment with Kohlberg’s work on moral development. Kohlberg writes “a moral choice involves choosing between two (or more) … values as they conflict in concrete situations” (Kohlberg 1975, p. 682). However, Kohlberg and those who have built on his work attend almost exclusively to cognition (e.g., values and moral frameworks) and how social expectations factor in moral reasoning (Rest et al. 2000). They do not consider the affective aspects of interpersonal and intrapersonal factors within conflict resolution, which can be found in CDT. Each of the three CDT theorists argues that the interpersonal (awareness of others), intrapersonal (awareness of self), and cognitive are intertwined. We assert that situations of potential conflict are spaces in which intrapersonal awareness is made apparent. Essentially, how one chooses to resolve a conflict reflects a sense of self in relation to others and in relationship to principles or values. How someone identifies the source of, as well as the resolution of, conflict can be indicative of their intrapersonal awareness.

The person in Position 1 can think logically about their perceptions but is unable to simultaneously consider the perceptions of others; their focus is on their own interests and preferences. Therefore, in a conflict they will usually resolve it in favor of their own needs and desires, not for any principled reason. The shift from second order (Position 1) to third order (Position 2), Kegan argues, is reflected in the “need to take out membership in a community of interest greater than one, to subordinate their own welfare to the welfare of the team, even, eventually, to feel a loyalty to and identification with the team” (Kegan 1994, p. 47). At first this may be a tacit acceptance to conform to what “everyone” expects (Position 2). In time, it may develop into a greater sense of identity, grounded in particular relationships, social alignments, and values (Position 3). The capacity to identify one’s relationship and to make choices for the good of that relationship is an indicator of development beyond prior positions. In time, this capacity may limit the self, as the boundaries and expectations of the relationship can serve as the boundaries of the self.

The person in Position 4 becomes able to distinguish between themselves and their relationships and is better able to express a self that is distinct from those relationships. While remaining deeply invested in their relationships and their values, they increasingly do not feel the need to conform to others’ expectations of them for those relationships. The person in Position 5 is even more integrated; they reflect principles and values that they hold dear, even as they are mindful of their relationships and context. Baxter Magolda describes this as “trusting the internal voice” (Baxter Magolda 2010). These positions align well with the three schemas identified in the Neo-Kohlbergian Defining Issues Test (DIT) of moral development, except that those schemas lack consideration of the affective dimensions of relationships and self-understanding (Rest et al. 2000; Thoma et al. 2013). We represent our range through the following five positions in Table 4.

Table 4.

Gradation of Conflict Resolution for each of the 5 LAMP Positions.

Within a religious framework, given a conflict, a person in Position 1 would choose the path that was most personally advantageous. There is no sense of “morals,” as that requires the ability to ideate. There are only rules regulating behavior. They would do “the right thing” if there were negative personal consequences for not doing so, perhaps meted out by an all-powerful and watchful God. In Position 3, if religious belief and belonging are important, there is a strong desire to align with the religious community and act as expected by the community’s norms. There may be a strong sense that not to align, in belief or practice, is to be unfaithful to that community, which is to be avoided. The individual in Position 5 is guided by the community but is aware that they are responsible for their decisions in a conflictual situation and how those decisions impact others. They are more aware of diversity within the community, and even accept as valid members, those with whom they strongly disagree.

3.4. Sense of Responsibility (Intrapersonal, Interpersonal and Cognitive)

The final facet, sense of responsibility, reflects both intrapersonal, interpersonal, and cognitive characteristics. As “boundaries of awareness … expand … the person begins to move in new ways in the adult world of responsibility” (Daloz Parks 2000, p. 93). As such, a person’s sense of responsibility, often expressed as guilt, can be a strong indicator of meaning-making capacity (Leahy et al. 2011, p. 15).

Framed within a religious context, in Position 1 relationships and obligations to others are not yet acknowledged, so there is no sense of responsibility to other people, values, or beliefs. They may feel guilty for their actions, but that is usually reserved for situations for which there are obvious and immediate negative consequences. Those in Position 3 reflect an awareness of relationships and social connections, resulting in feelings of responsibility to those relationships. For them, religious belonging can be very important, thus they can align with the community’s beliefs and moral framework. In fact, they may feel guilty for upsetting others or falling short of the community’s teachings or expectations but are still looking to others to determine the rules of engagement (Kegan 1994).

As an individual comes to see themself as having relationships, but not being defined by them, they can begin (Position 5) to “reflect on, control, take responsibility for” those relationships (Leahy et al. 2011, p. 9) by determining how they will be in them. In the religious context, they determine how they engage in their relationships within the community. They can develop a linkage between the religious community’s beliefs and their own interpretation, which then directs their actions within their relationships. In Position 5 they can consistently name who they are in their relationships and better see how their attitudes and actions shape the relationship for themselves and others. As such they become more responsible for those relationships. They recognize they not only determine their own beliefs and practices, but also their example and guidance shape the rules of engagement for everyone within the religious community (see range in Table 5). Again, these positions align well with the schemas of the DIT (Rest et al. 2000; Thoma et al. 2013).

Table 5.

Gradation of Sense of Responsibility for each of the 5 LAMP Positions.

This concludes our description of the four facets of CDT and their gradations that serve to operationally define meaning-making in order to facilitate quantitative assessment. In the next section we describe how we used this reframing to develop the LAMP-C instrument.

4. Methodological Foundations

4.1. Rasch/Guttman Scenario Method of Instrument Construction

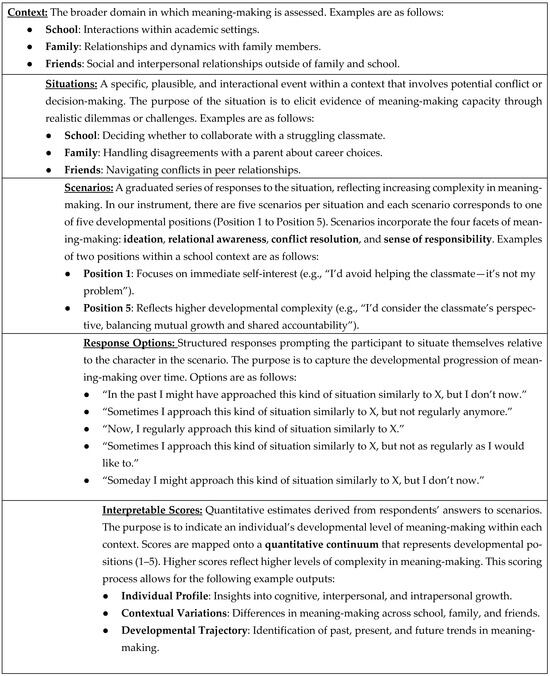

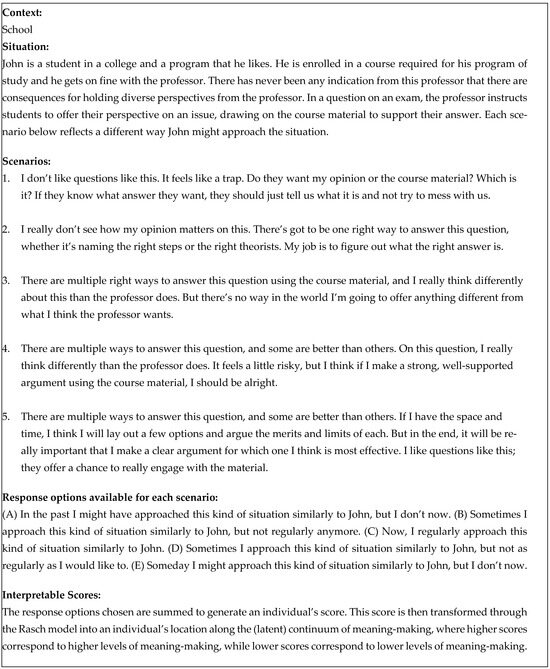

As mentioned above, the Rasch/Guttman Scenario approach to instrument construction begins by breaking down a complex construct (like meaning-making) into its characteristics, or facets (Ludlow et al. 2014, 2020). These facets are carefully combined to generate scenarios that incorporate responses to situations—typically involving some sort of conflict—in common contexts in which emerging adults exercise meaning-making. In LAMP-C, we produce three instruments, each reflecting a different context: school, family, and friends, with a potentially conflictual situation. For each context, there are five scenarios, the facets of which, identified above, are incrementally changed to reflect gradations of meaning-making capacity. The full sequence of scenarios within the context reflects the range of meaning-making capacity among emerging adults in that context. In this section, we discuss the choice of contexts and the development of situations within each context; the construction of scenarios; the formulation of the response options; and the interpretation of scores. Scheme 1 describes the relationships among context, situation, scenario, response options, and interpretive scores. Figure 1 (below) demonstrates how these components come together for the school instrument.

Scheme 1.

The LAMP-C Framework for Assessing Meaning-Making.

Figure 1.

The LAMP School Context.

Next, we turn to a discussion of how language use is an important consideration in instrument development. Each of the theorists, Kegan, Daloz Parks, and Baxter Magolda, uses qualitative interviews to gather information about subjects. For example, the Subject–Object Interview protocol developed by Kegan and Leahy offers interview prompts, such as “What makes being in this school important to you?” (Leahy et al. 2011, p. 51). It also offers rubrics for coding the interviews. Central to the coding process is attending to how subjects use language to describe their circumstances. A subject’s use of language is an important consideration in assessing meaning-making capacity. For example, does the subject use concepts, themes, or values in their narration, or is their speech limited to concrete actions and preferences? Is their speech primarily self-referential or do they consider their relationship to and impact on others? When considering decisions, to whom do they defer? How a person talks about themselves and their world reflects how they perceive and make meaning of their worlds (Leahy et al. 2011).

In contrast to the Subject–Object Interview, LAMP-C assesses meaning-making capacity through an approach whereby the situations and the language are provided by the instrument. Instead of offering interview prompts, the RGS method requires the development of a set of scenarios that correspond to a particular situation that emerging adults would likely encounter and recognize within a context. As described above, each scenario is designed to be a capsule description of a character acting in a real-life situation. The respondent is asked to compare themselves to the character in the situation. Since the scenarios present five distinct ways of making meaning of the situation, each scenario must reflect the language and concepts as they would typically be used by people in the corresponding position. Consequently, within a context, different kinds of language appear in each scenario. In Position 1, the character speaks of concrete actions and personal preferences. By Position 5, the character talks about prioritizing among competing values and ideas. This pattern of change over the five positions, as shown in Figure 1, is constructed so as to reflect an increasing complexity in meaning-making capacity.

4.2. The Choice of Contexts, the Development of Situations and Scenarios

LAMP-C comprises three instruments, each corresponding to a specific context, with each context presenting a plausible, interactional situation.5 Since “cognitive-developmental assessment is not independent of context” (King 1990, p. 84) and we are assessing emerging adults, we chose contexts that would likely be relevant to them. They are family, school, and friends. We hypothesize that emerging adults will typically exhibit higher levels of meaning-making in the school context, as school is designed to challenge and support new ways of meaning-making (Daloz Parks 2000). On the other hand, in the context of family, students may exhibit lower levels of complexity in meaning-making, as there are longstanding patterns of behavior and potentially strong emotional consequences for change. By challenging emerging adults to respond in three different contexts, we intend to create a rich profile of their meaning-making capacity, with particular interest in apparent differences across the three contexts.

In order to elicit evidence with respect to an individual’s capacity for meaning-making, the situations are potentially conflictual, as each situation calls for a decisive action. Whether it is interpreted as conflictual depends on how the individual makes meaning of the situation. Five possible ways of making meaning of each situation are manifested in the five scenarios, designed to represent gradations in meaning-making. The emerging adult responds to each scenario, employing one of five response options.

The construction of the scenarios to define each meaning-making position followed the Rasch measurement principles and procedures (See Ludlow et al. 2014, 2020):

- The items should measure a single construct and range from lower to higher levels of the construct;

- The items should define a clear, substantively meaningful, hierarchical progression with respect to the construct; and

- The a priori underlying theory of the construct should be reflected in the empirical results.

This means LAMP-C scenarios were written to follow principles 1 and 2 with the third principle as a cornerstone for the establishment of content and construct validity. Following principle 1, each scenario combines elements of the four facets of the construct “meaning-making” identified above: cognition, relational awareness, conflict resolution and sense of responsibility. The first scenario reflects the facets as outlined for Position 1, and so forth, until the last scenario reflects Position 5. Following principle 2, the sequence of five scenarios within a context represents a progressively more complex capacity for meaning-making. As an example, consider the school instrument in Figure 1. This deliberate, systematic item construction procedure is intended to generate an a priori expected ordering of the scenarios along our hypothesized meaning-making continuum for the context, thus aligning with principle 3. We address construct validity in the next section.

4.3. Response Options and Instrument Validity

The RGS approach functions differently from typical instrument development in important ways. Rather than using traditional response formats, such as agree/disagree, an RGS instrument employs distinctive “comparative response” options. In LAMP-C, the respondent is asked to compare themselves to the character in each scenario. More specifically, the instructions direct the respondent “to imagine yourself in each situation and consider the degree of similarity between your approach to that of the character’s approach.” They are then offered five options:

- In the past I might have approached this kind of situation similarly to X, but I don’t now.

- Sometimes I approach this kind of situation similarly to X, but not regularly anymore.

- Now, I regularly approach this kind of situation similarly to X.

- Sometimes I approach this kind of situation similarly to X, but not as regularly as I would like to.

- Someday I might approach this kind of situation similarly to X, but I don’t now.

Since our instrument is based on CDT, we presume respondents have experienced change in meaning-making capacity over time. Therefore, the response options represent change over time, requiring the respondent to situate themselves vis-à-vis each scenario in a manner that reflects their recollection of those changes in meaning-making over time.

As mentioned above, RGS empirical results should reflect the a priori expected order of the scenarios, aligned with their levels of developmental capacity of meaning-making. By creating scenarios that contain five increasingly complex approaches (positions) to situations and asking respondents to compare themselves to the character in each scenario, we are able to test the validity of the instrument itself. Further, by requiring respondents to choose a response for each scenario, rather than identify a scenario that best fits their current situation, we are able to produce a “score” for each scenario, not just for each respondent (Ludlow et al. 2021). Therefore, if meaning-making changes developmentally, then we expect to see respondents reflect on their changes over time through their selection of responses to the full sequence of scenarios (e.g., in the past I might have approached (Position 1 scenario) and someday I might approach (Position 5 scenario)). Ideally, with a well-designed instrument, the ‘scores’ of the scenarios will form a ladder-like progression that is congruent with their hypothesized order.6

However, if the results for a sample of students do not conform to our design expectations, we first consider the instrument to be the source of the problem, not necessarily the sample. This means that the RGS method inherently relies on an iterative process of feedback and corrections to guide modifications.

4.4. Respondent Score Interpretation

Once the internal validity of the instrument has been established, it is then possible to generate rich interpretations of an individual’s location along the (latent) continuum of meaning-making. To this end, the so-called ‘variable map’, a key product of a Rasch model analysis, is crucial. These maps are graphical representations that simultaneously display the scenarios’ scores (i.e., their “difficulty” estimates) and the estimates of the respondents’ levels of meaning-making, both as locations along a quantitative continuum. This continuum, together with the scenarios’ design features provide the basis for a specific and actionable interpretation of a person’s score.

For example, in addition to the ordering of the scenarios from simpler (Position 1) to the more complex (Position 5) responses to situational interactions, the response options are framed in terms of past to future responses to those situations. Thus, scores are generated for both scenarios and respondents. Specifically, higher scores for respondents correspond to greater complexity in meaning-making, while lower scores correspond to less complexity in meaning-making. A respondent’s score can then be interpreted in terms of their meaning-making capacity, employing the facets identified above: cognition, relational awareness, conflict resolution, and sense of responsibility. However, research indicates that it is easier for respondents to recognize themselves within a given scenario, rather than producing their own response to a situation (King 1990). While this is a distinct benefit of our approach, enhancing accessibility, it is also possible that respondents may recognize a level of meaning-making somewhat higher than their capacity to produce on their own. Therefore, score interpretation requires some nuance, with the respondent located within a specific range of meaning-making capacity. It would be beneficial to conduct some qualitative interviews (e.g., Subject–Object) with emerging adults who have taken the LAMP-C scale and analyze the results of both assessments. Feedback from that process could potentially offer further validation of the construct and the corresponding scale as well as guidance on score interpretation. LAMP-C offers a rich narrative of an emerging adult’s meaning-making capacity. Were the instrument to be administered at different occasions over the course of time, it should be able to capture and represent enhanced meaning-making capacity.

Although LAMP-C does not assess religious belief or belonging, an individual’s scores can be interpreted in conjunction with their scores on religiosity scales to yield a more comprehensive understanding of the individual. For example, someone providing Position 1 and 2 level responses across the scenarios within a context would likely be participating in religious practices because someone requires it of them, but they may not be able to accurately express the meaning of those practices and will likely choose to end the practice if given the opportunity. A person providing primarily Position 3 level responses across the scenarios may be deeply committed to their religious community, understand the meaning behind its practices, but they may also see their tradition as monolithic, with clear lines separating those in and out of the community. Finally, a person providing Position 4 and 5 level responses may also be deeply committed to their religious community yet be more selective in their religious practices or diverse in their beliefs, either in frequency or manner. They may also feel a strong sense of responsibility to that community and its values. Those values would be evident in their interactions within the community, as well as beyond the community.

More specifically, by assessing the individual’s meaning-making capacity alongside another scale, we get a sense of their ability to make meaning of religious practices, beliefs, and affiliation. For example, if someone provides Position 1 and 2 level responses on LAMP-C and responds “Definitely not true” to the statement “My religious beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life” found in both the DUREL and the Hoge scales, we might conclude that they probably cannot imagine a “whole approach” to their life, since they perceive life as more concrete and episodic (Hoge 1972; Koenig and Büssing 2010). However, if they provide Position 3 level or higher responses while offering the same Hoge scale response, we might conclude that they have the capacity for a “whole approach” to life, but that religion does not factor into that approach.

5. Implications and Future Directions

The development of LAMP-C represents a significant theoretical and methodological advancement in the assessment of meaning-making among emerging adults. By reframing CDT into quantifiable facets—ideation, relational awareness, conflict resolution, and sense of responsibility—this work bridges the gap between theoretical constructs and practical assessment tools. The implementation of the Rasch/Guttman Scenario (RGS) methodology both requires and enables the creation of scenarios that reflect developmental complexity. It also facilitates the systematic measurement of nuanced growth processes across contexts (e.g., school, family, and friends). This novel approach advances the field by providing a scalable, quantitative alternative to labor-intensive qualitative methods.

5.1. Value of the LAMP-C Scales

The importance of defining and assessing meaning-making as a developmental construct for emerging adults is underscored by research demonstrating the relationship between meaning-making and such outcomes as identity formation, resilience, interpersonal competence, and overall well-being (Baxter Magolda 2001; Kegan 1994; King 2009). We believe that assessing an individual’s capacity for meaning-making has real value for projects assessing religious belief and belonging, since an individual’s cognitive, interpersonal and intrapersonal capacities delimit how they understand, relate to and use religious belief, belonging, and practice. The mechanisms for assessing how meaning-making capacity influences religiosity remain an area of exploration, but insights from constructive-developmental theory suggest that the ability to navigate complexity, resolve conflicts, and maintain a sense of responsibility plays a central role in fostering personal growth and purpose (Daloz Parks 2000; Kegan 1994). We believe LAMP-C adds the valuable construct of meaning-making capacity to an overall assessment of emerging adults’ religious belief and belonging.

This work contributes to the building of a nomological net (Cronbach and Meehl 1955) for a more nuanced conceptualization of religious belief and belonging by attending to meaning-making and its developmental progression within context-specific applications. The LAMP-C scales operationalize this construct in a way that allows for both precise measurement and systematic investigation, creating pathways for linking meaning-making to religiosity.

Beyond assessment of religiosity, LAMP-C could contribute to other assessments of well-being, purpose and flourishing (Padgett et al. 2024). Finally, meaning-making is a complex construct, which until now has only been assessed through qualitative means. LAMP-C, as the only quantitative tool for assessing this construct, can be a valuable instrument in diverse projects with emerging adults.

5.2. Practical Applications of the LAMP-C Scales

Scores on the RGS-based LAMP-C scales represent an emerging adult’s location along a continuum of developmental complexity incorporating the facets of ideation, relational awareness, conflict resolution, and sense of responsibility. This measurement approach not only describes an individual’s current developmental stage but also provides specific insights into what would be required to advance to a higher level of meaning-making complexity. By providing interpretive frameworks for scores, the LAMP-C scales offer a roadmap for understanding developmental progress and evaluating change over time.

The potential utility of the LAMP-C scales could extend beyond assessing religious belief and belonging to applications in assessing programming efficacy and in institutional planning. Although this remains speculative, formation leaders could use the scale scores to identify those who may benefit from targeted support, such as those struggling to reconcile competing values or navigating relational complexities. Similarly, religious institutions might employ the scales to assess the efficacy of formative initiatives aimed at fostering reflective and purpose-driven individuals.

For example, we can imagine that a respondent with a relatively low score profile corresponding to frequent Position 1 level responses might be well served by religious instruction that offers the meaning behind the tradition’s practices or moral injunctions. Simply assuming that such a low-scoring person already understands the teachings or values of the community could result in misaligned efforts. Similarly, those providing frequent Position 2 level responses would likely benefit from appreciating the value of their particular religious community so as to affiliate intentionally. Finally, those providing frequent Position 3 level responses would benefit from learning about the diversity within their religious tradition and community, so as to ground their belief and belonging within a wider world.

Repeated administrations of the scales over time could chart growth, offering actionable data to inform programmatic efforts and better meet developmental needs. Moreover, the developmental progression potentially captured by the LAMP-C scales would align with evidence suggesting that meaning-making is both measurable and malleable (Baxter Magolda 2010).

In sum, the LAMP-C scales have the potential to provide a robust framework for measuring, interpreting, and fostering meaning-making capacities among emerging adults. By integrating developmental theory with a rigorous measurement methodology, these scales can offer valuable insights into the complexities of development and practical tools for enhancing formation. This combination positions the LAMP-C instrument as a critical resource for advancing both research and practice.

5.3. Future Directions

To enhance the validity and utility of the LAMP-C construct and scale, researchers could conduct qualitative interviews with some individuals who have also taken the LAMP-C scale. Analysis of the results of both could create a valuable foundation for LAMP-C score interpretation.

By situating LAMP-C within broader frameworks of research on religion, future studies could examine correlations with religious practice, affiliation, and belief. Scales like the 10-item Hoge scale on intrinsic religiosity or the DUREL could provide interpretable feedback on the observed correlation (Hoge 1972; Koenig and Büssing 2010).

Subsequently, repeated administrations could evaluate developmental progressions and deepen our understanding of how meaning-making actually evolves across life stages.

6. Conclusions

This paper has outlined our theoretical rationale for distinguishing among four foundational facets of meaning-making—ideation, relational awareness, conflict resolution, and sense of responsibility—while demonstrating how these constructs can be systematically defined and measured through the methodological rigor of RGS. Looking ahead, LAMP-C has the potential to enhance the assessment of religious belief and belonging by integrating an individual’s meaning-making capacity into a comprehensive assessment of emerging adults’ religiosity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.O. and L.H.L.; methodology, L.H.L.; writing—original draft preparation T.A.O. and L.W.; writing—review and editing, L.H.L., C.M. and H.I.B.; visualization C.M.; funding acquisition T.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by contributions from the Association of Youth Ministry Educators through the Taylor University/Lilly Foundation Grant (2023), as well as by Boston College through a Formative Education Grant (2022) and a Teaching, Advising and Mentoring Grant (2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston College (protocol code: 24.076.01e; approval date: 9 August 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, T.AO., upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LAMP-C | Lives of Meaning and Purpose-C |

| CDT | Constructive-Developmental Theory |

| RGS | Rasch/Guttman Scenario methodology |

| DUREL | Duke University Religion Index |

| DIT | Defining Issues Test |

Notes

| 1 | The coding instruction guide for the Subject–Object Interview, distinguishes six positions across a transition from one order to the next: X, X(Y), X/Y, Y/X, Y(X), Y. (Leahy et al. 2011, p. 42). |

| 2 | Kegan offers a rich review and analysis of Jean Piaget’s contributions to constructive-developmental theory in chapter one of The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development (Kegan 1982). |

| 3 | The neurobiological changes that begin with the onset of puberty were unknown to Jean Piaget at the time of his research but are widely recognized now. These changes, particularly the development of the prefrontal cortex, create the possibility for self-consciousness, ideation and executive functioning, as well as a deeper sense of time past and future. However, the development of complexity of mind is not inevitable, but requires the neurobiological tools and the appropriate challenges and supports (Kegan 1982, 1994). |

| 4 | Conscious alignment is not inevitable. This can also be a time of intentional disaffiliation, when one no longer wishes to be part of the community one has been part of by circumstance, like family membership (O’Keefe and Jendzejec 2020). |

| 5 | An instrument refers to the set of items that are measuring a construct. In LAMP-C we have three instruments, each measuring meaning-making but each instrument is for a different context. The set of three instruments comprises a battery or ‘portfolio’. |

| 6 | An early iteration of LAMP-C was presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association in 2022. While there were initially positive results, that version did not present the desired ladder-like distribution as clearly as was intended, so this current version is a dramatic reworking of the instruments (O’Keefe et al. 2022). |

References

- Abes, Elisa S., and Ebelia Hernández. 2016. Critical and Poststructural Perspectives on Self-Authorship. New Directions for Student Services 2016: 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey J. 2004. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter Magolda, Marcia B. 2001. Making Their Own Way: Narrative for Transforming Higher Education to Promote Self-Development. Sterling: Stylus. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter Magolda, Marcia B. 2009. The activity of meaning making: A holistic perspective on college student development. Journal of College Student Development 50: 621–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter Magolda, Marcia B. 2010. The interweaving of epistemological, intrapersonal, and interpersonal development in the evolution of self-authorship. In Development and Assessment of Self-Authorship: Exploring the Concept Across Cultures. Edited by Marcia B. Baxter Magolda, Elizabeth G. Creamer and Peggy Meszaros. Sterling: Stylus, pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Peter L., Michael J. Donahue, and J. A. Erickson. 1993. The Faith Maturity Scale: Conceptualization, measurement, and empirical validation. In Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion. Edited by Monty L. Lynn and David O. Moberg. Greenwich: JAI Press, vol. 5, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 1990. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Open Road Integrated Media, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer, Elizabeth G., Marcia B. Baxter Magolda, and Jessica Yue. 2010. Preliminary evidence of the reliability and validity of a quantitative measure of self-authorship. Journal of College Student Development 51: 550–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, Lee J., and Paul E. Meehl. 1955. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin 52: 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daloz Parks, Sharon. 2000. Big Questions, Worthy Dreams: Mentoring Young Adults in Their Search for Meaning, Purpose, and Faith. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1954. The Myth of the Eternal Return. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fallar, Robert, Basil Hanss, Roberta Sefcik, Lucy Goodson, Nathan Kase, and Craig Katz. 2019. Investigating a quantitative measure of student self-authorship for undergraduate medical education. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development 6: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, James. 1981. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, Cary, and Gregory Smith. 2012. ‘Nones’ on the Rise. Washington: Pew Research Center. Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Galea, Paul, and Carl-Mario Sultana. 2025. The Religiosity of Adolescents and Young Adults in Malta: Tracing Trajectories. Religions 16: 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gwyn, Wendy G., and Michael J. Cavanagh. 2023. Adolescents’ Experiences of a Developmental Coaching and Outdoor Adventure Education Program: Using Constructive-Developmental Theory to Investigate Individual Differences in Adolescent Meaning-Making and Developmental Growth. Journal of Adolescent Research 38: 911–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Todd W., and Keith J. Edwards. 1996. The initial development and factor analysis of the Spiritual Assessment Inventory. Journal of Psychology and Theology 24: 233–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, Jeffrey A., and Tyler J. VanderWeele. 2021. The comprehensive measure of meaning: Psychological and philosophical foundations. In Measuring Well-Being: Interdisciplinary Perspectives from the Social Sciences and the Humanities. Edited by Matthew Lee, Laura D. Kubzansky and Tyler J. VanderWeele. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 339–76. [Google Scholar]

- Helsing, Deborah, and Annie Howell. 2014. Understanding leadership from the inside out: Assessing leadership potential using constructive-developmental theory. Journal of Management Inquiry 23: 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Peter C. 2013. Measurement, assessment, and issues in the psychology of religion and spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2nd ed. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 48–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hoge, Dean R. 1972. A validated intrinsic religious motivation scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 11: 369–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegan, Robert. 1982. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan, Robert. 1994. Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan, Robert, and Lisa Leahy. 2000. How the Way we Talk Can Change the Way we Work: Seven Languages for Transformation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan, Robert, and Lisa Leahy. 2009. Immunity to Change: How to Overcome it and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Patricia M. 1990. Assessing Development from a Cognitive-Developmental Perspective. In College Student Development: Theory and Practice for the 1990’s. Edited by Don G. Creamer. Washington: American College Personnel Association, pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- King, Patricia M. 2009. Principles of development and developmental change underlying theories of cognitive and moral development. Journal of College Student Development 50: 597–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold, and Arndt Büssing. 2010. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A Five-Item Measure for Use in Epidemiological Studies. Religions 1: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, Lawrence. 1975. The Cognitive-Developmental Approach to Moral Education. The Phi Beta Kappan 56: 670–77. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy, Lisa, Emily Souvaine, Robert Kegan, Robert Goodman, and Sally Felix. 2011. A Guide to the Subject-Object Interview: Its Administration and Interpretation. Cambridge: Minds at Work. [Google Scholar]

- Leak, Gary K., and Stanley B. Fish. 1999. Development and initial validation of a measure of religious maturity. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leak, Gary K., Anne A. Loucks, and Patricia Bowlin. 1999. Development and initial validation of an objective measure of faith development. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: 105–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludlow, Larry H., Christina Matz-Costa, Clair Johnson, Melissa Brown, Elyssa Besen, and Jacquelyn J. Brown. 2014. Measuring engagement in later life activities: Rasch-based scenario scales for work, caregiving, informal helping, and volunteering. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 47: 127–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludlow, Larry H., Katherine Reynolds, Maria Baez-Cruz, and Wen-Chia Chang. 2021. Enhancing the interpretation of scores through Rasch-based scenario-style items. In Basic Elements of Survey Research in Education: Addressing the Problems Your Advisor Never Told You About. Edited by Allen G. Harbaugh. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, pp. 673–718. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, Larry H., Maria Baez-Cruz, Wen-Chia Chang, and Katherine Reynolds. 2020. Rasch/Guttman scenario scales: A methodological framework. Journal of Applied Measurement 21: 361–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, Larry H., Theresa O’Keefe, Henry Braun, Ella Anghel, Olivia Szendey, Christina Matz, and Burt Howell. 2022. An Enhancement to the Theory and Measurement of Purpose. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 27: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, Dan P. 2013. The psychological self as actor, agent, and author. Perspectives on Psychological Science 8: 272–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, Theresa A., and Emily Jendzejec. 2020. A New Lens for Seeing: A Suggestion for Analyzing Religious Belief and Belonging among Emerging Adults through a Constructive-Developmental Lens. Religions 11: 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, Theresa A., Larry H. Ludlow, Christina Matz-Costa, Henry I. Braun, Ella Anghel, and Olivia Szendey. 2022. Measuring the development of meaning-making. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA, USA, April 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, R. Noah, Jeffrey Hanson, Julia S. Nakamura, James L. Ritchie-Dunham, Eric S. Kim, and Tyler J. VanderWeele. 2024. Measuring meaning in life by combining philosophical and psychological distinctions: Psychometric properties of the Comprehensive Measure of Meaning. The Journal of Positive Psychology 20: 682–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, Jean. 1952. The Origins of Intelligence in Children. Translated by Margaret Cook. New York: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzolato, Jane E. 2003. Developing self-authorship: Exploring the experiences of high-risk college students. Journal of College Student Development 44: 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, James R., Darcia Narvaez, Stephen J. Thoma, and Murial Bebeau. 2000. A neo-Kohlbergian approach to moral judgment: Overview of the Defining Issues Test Research. Journal of Moral Education 29: 381–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Tatjana. 2009. The Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (SoMe): Relations to demographics and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 483–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Tatjana, and Lars J. Danbolt. 2023. The Meaning and Purpose Scales (MAPS): Development and multi-study validation of short measures of meaningfulness, crisis of meaning and sources of purpose. BMC Psychology 11: 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Cherry, and Brenda Wolodko. 2016. University educator mindsets: How might adult constructive-developmental theory support design of adaptive learning? Mind, Brain, and Education 10: 247–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Kari B. 2016. Diverse and Critical Perspectives on Cognitive Development Theory. New Directions for Student Services 2016: 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, Stephen J., Pitt Derryberry, and H. Michael Crowson. 2013. Describing and testing an intermediate concept measure of adolescent moral thinking. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 10: 239–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Yunping. 2025. Globally, 1 in 10 Adults Under 55 Have Left Their Childhood Religion. Washington: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2025/06/26/globally-1-in-10-adults-under-55-have-left-their-childhood-religion/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).