Abstract

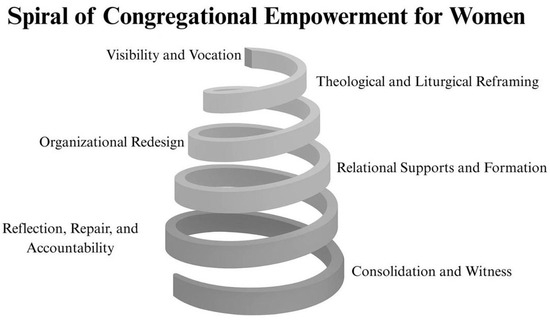

Patriarchy has long structured Christian life and practice. In many Baptist settings, even formal affirmations of women in leadership leave a gap between stated commitments and women’s lived experience. This study investigates how Baptist congregations cultivate empowering environments for women by tracing the interplay of beliefs, practices, and processes through which theology is enacted in congregational life. Drawing on feminist theology and lived-religion perspectives, and using constructivist grounded theory, we conducted nine semi-structured interviews with 15 women clergy across seven U.S. Baptist congregations. Analysis proceeded through iterative initial, focused, and theoretical coding with attention to reflexivity and trustworthiness. Findings highlight four interlocking dynamics: structural shifts in leadership and policy that institutionalize gender equity; cultural and theological intentionality in worship and congregational routines; relational practices of support and education; and the persistence of microaggressions and benevolent sexism that complicate progress. Synthesizing these themes, we adapt Cornwall’s cyclical account of empowerment and Carr’s feminist praxis into a Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women comprising six phases (see Discussion). This study contributes to feminist theology, congregational studies, and the sociology of religion and offers practical implications for congregations and ministerial formation to align worship, policy, culture and accountability for sustained gender equity.

1. Introduction

Patriarchy has been deeply entrenched within the Christian church and its traditions for centuries (Barr 2021; Daly [1968] 1986; Ruether 1983). At the same time, the Christian church has been one of the most influential institutions in the United States with a long history of influencing social norms and values. This influence has diffused patriarchy beyond church walls and has validated and supported the subjugation of women. This subjugation has not only influenced women’s spiritual lives, but it has also shaped their opportunities, roles, and autonomy in society (Daly [1968] 1986; Ruether 1983).

Within Baptist traditions, this patriarchal inheritance has been particularly acute, as women have been excluded from leadership roles and relegated to secondary positions within congregational life. In the most recent State of Women in Baptist Life report (SOWBL) (Baptist Women in Ministry 2022), Baptist Women in Ministry reported that 86% of the women they surveyed faced obstacles in their ministry due to their gender, revealing just how deep-seated patriarchal ideologies remain within Baptist congregations. Although many Baptist churches in recent decades have affirmed women in ministry, the persistence of patriarchal practices creates an incongruence between stated commitments to gender equity and the lived experiences of women in these congregations.

Feminist theology has long argued that authentic Christian witness requires the dismantling of these patriarchal structures and the cultivation of congregations where women’s gifts are recognized as integral to the life of the church (Bloom 2019; Custis-James 2011; Lauve-Moon 2021; Ruether 1983). Likewise, the study of lived religion emphasizes the importance of attending not only to formal doctrine but also to the everyday practices, rituals, and organizational patterns that shape religious congregations (Ammerman 2021). Taken together, these perspectives suggest that the question of how congregations empower (or disempower) women is both a theological and a practical concern.

Both feminist theology and lived-religion scholarship frame empowerment as a theological and practical concern for congregational life. This study explores the beliefs, practices, and processes by which Baptist congregations foster empowering environments for women, using empowerment theory through a feminist lens and constructivist grounded theory. We preview an emergent, integrative model—the Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women—that synthesizes these dynamics across theology, worship, structure, and relationships.

2. Theoretical Orientation

2.1. Feminist Theology and Empowerment

This study begins from the feminist theological conviction that women’s full humanity and giftedness before God are non-negotiable for the life of the church. Classic feminist theologians argue that patriarchal God-images and ecclesial hierarchies have authorized women’s subordination, and that justice requires transforming both symbols and structures (Daly [1968] 1986; Flowers 2016; Pierce et al. 2021; Ruether 1983; Schussler Fiorenza 1983, 1993). Empowerment theory, read through a feminist lens, treats empowerment as a praxis-driven, relational and contextually situated process: conscientization, critical reflection, and action mutually reinforce one another in everyday life (Carr 2003). This framing enables us to interpret congregational change not as a single policy decision but as a sustained theological, cultural, organizational, and relational reordering aimed at equity.

2.2. Lived Religion and Congregational Practice

Attending to lived religion shifts the analytic focus from formal doctrine alone to the practices, rituals, speech, and organizational routines through which belief is enacted and socialized in congregational life (Ammerman 2021). In congregations, who speaks, how God is named, how decisions are made, and what policies govern staff are not peripheral details; they are formative liturgies that teach people who God is and who may lead. This lens positions worship language, governance models, hiring and leave policies and everyday interactions as data for understanding how gender equity is either undermined or concretized in congregational life.

2.3. Constructivist Grounded Theory

The theoretical approach for this qualitative study is constructivist grounded theory (CGT). Following Charmaz (2014), we employed sensitizing concepts—ideas that orient inquiry without dictating categories or sequence. Two are central here: (1) feminist empowerment as cyclical praxis (Carr 2003) and (2) Cornwall’s (2016) description of empowerment as a spiral, an interactive, mutually reinforcing and non-linear process. We use these concepts to remain alert to recursive patterns in the data while allowing categories to emerge inductively.

The first author’s identity as a Baptist woman and professional work supporting and advocating for women in ministry necessarily shape the research encounter. Consistent with CGT, we approach this study reflexively, acknowledging how our social locations, commitments, and interactions inform data generation and interpretation (Charmaz 2014), while centering participants’ accounts.

We also used sensitizing concepts that orient inquiry without dictating categories or sequence (Charmaz 2014). Two are central: Carr’s (2003) feminist empowerment as cyclical praxis and Cornwall’s (2016) description of empowerment as a spiral—iterative, mutually reinforcing, and non-linear. We remain alert to recursive patterns while allowing categories to emerge inductively, and we later name the integrated pattern we observed as a Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women rather than imposing a priori stages.

3. Methodology

This study employed a qualitative design using constructivist grounded theory to explore the markers, beliefs, practices, and processes that foster empowering environments for women in Baptist congregations. Data were collected through nine semi-structured interviews with 15 women clergy across seven U.S. congregations identified in partnership with Baptist Women in Ministry. Data analysis proceeded through CGT iterative cycles of initial, focused, and theoretical coding (Charmaz 2014). This study prioritized trustworthiness through triangulation, peer debriefing, and the maintenance of an audit trail, while researcher reflexivity and positionality were integrated throughout the analytic process.

3.1. Recruitment and Participants

This study utilized a purposeful sampling strategy. Churches were identified in partnership with Baptist Women in Ministry (BWIM), a national nonprofit organization that supports women pursuing ministry and leadership through resources, advocacy, and community. BWIM staff initially contacted congregations where women clergy had reported experiences of empowerment, and these congregations were invited to participate in this study. Inclusion criteria required that participants (a) self-identify as a woman, (b) be at least 18 years old, and (c) currently serve or have previously served in a ministry or leadership position in a Baptist congregation identified by BWIM as fostering empowering environments for women. Congregations without women clergy or without such an identification were excluded.

Fifteen women clergy from seven Baptist congregations across the United States ultimately participated. Participants serve in a range of pastoral roles, including senior pastor (n = 4), pastor (n = 1), associate pastor (n = 3), children’s pastor (n = 1), retired pastor (n = 2), and co-pastor (n = 4). Ages ranged for the 30s to 60s with six participants in their 30s (40%), four in their 40s (27%), one in her 50s (7%), and four in their 60s (27%). One participant identified as lesbian and two identified as Hispanic/Latina. To protect confidentiality, each congregation and participant was assigned a pseudonym, and identifying details were altered.

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

The researcher conducted nine semi-structured interviews with 15 participants across the seven congregations. All interviews were conducted during site visits to the congregations. In some congregations, the pastors were interviewed individually. In other congregations, the pastors were interviewed as a group. Whether or not the pastors were interviewed individually or as a group was determined by the availability of the pastors for interviews while the principal investigator was on site. Each interview lasted between 60 and 120 min and was audio- and video-recorded with participant consent. Sampling concluded when thematic saturation was reached, as no new themes emerged across congregations.

3.2.1. Interview Protocol

The qualitative interview protocol was developed by the researcher, drawing on existing literature on feminist theology, empowerment theory, and congregational studies, as well as the researcher’s professional experience with BWIM. The protocol included open-ended questions in five domains: (1) how they define an empowering environment for women, (2) congregational theological and biblical support for women, (3) congregational structure, policies, and decision-making processes, (4) relationships in the congregation; and (5) worship and liturgy. This structure allowed participants to reflect on both empowering and disempowering dynamics in their congregations while ensuring consistency across interviews. All interviews, whether one-on-one or as a group followed the same interview protocol.

3.2.2. Transcription and Confidentiality

Audio and/or video recordings were transcribed using a combination of Trint transcription software, a trained graduate student, and the researcher. The primary researcher verified all transcripts against the recordings for accuracy. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Confidentiality was prioritized through data collection and analysis. Pseudonyms were assigned to each participant and each congregation, and sensitive details were altered or omitted to protect identities.

4. Analysis

Analysis proceeded through three iterative stages: initial coding, focused coding, and theoretical coding (Charmaz 2014). During initial coding, each transcript was examined line by line to identify actions, beliefs, and processes described by participants. The codes remained provisional and close to the data, privileging participants’ language. This process generated 77 initial codes, which captured both empowering practices (e.g., inclusive worship, egalitarian policies) and persistent challenges (e.g., microaggressions, benevolent sexism).

During the focused coding stage, initial codes were compared, clustered, and refined into more analytically robust focused codes. The researcher and a second coder independently reviewed coding decisions. Areas of divergence were discussed until consensus was reached, thereby strengthening intercoder reliability.

The final stage, theoretical coding, synthesized the focused codes into higher-level theoretical categories that explain the processes by which congregations foster empowering environments for women. These categories form the basis for the conceptual model presented in the findings. During focused and theoretical coding, we integrated categories into an emergent process model that we later termed the Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women. We did not code to fit a pre-existing framework; rather the model crystallized as a higher-order synthesis of participant accounts.

4.1. Reflexivity and Positionality

Constructivist grounded theorists approach research with reflexivity, recognizing that both the research process and its outcomes are shaped through interpretation. These interpretations develop within existing structural contexts, in response to evolving circumstances, and are influenced by the researcher’s own perspective, social position, privilege, interactions, and geographical contexts (Charmaz 2014, pp. 239–40). This means that researchers need to critically reflect on how their own privileges and assumptions influence their analysis, rather than trying to remove or ignore them (Charmaz 2014).

The researcher identifies as a Baptist woman and served on staff with Baptist Women in Ministry during this study. This required explicit attention to reflexivity throughout analysis. Memos were maintained during coding to document analytic decisions and to reflect on the ways in which researcher positionality, privilege, and professional commitments may have shaped interpretation. This reflexive practice enhanced trustworthiness and rigor.

4.2. Trustworthiness and Rigor

Several strategies were employed to ensure analytic rigor. These included triangulation where codes were compared across participants, churches and data sources. This study also used peer debriefing. The researcher remained in regular consultation with the second coder to challenge assumptions and validate emerging themes. Finally, recruitment ceased when data saturation was reached and no new categories emerged, indicating sufficient depth for grounded theory development.

5. Findings

Drawing on nine semi-structured interviews with fifteen women clergy across seven U.S. Baptist congregations, the analysis illuminated four processes through which Baptist congregations create empowering environments for women: (1) structural shifts in leadership and policy that institutionalize gender equity; (2) cultural and theological intentionality in worship and congregational routines; (3) relational practices of support and education that sustain women’s flourishing; and (4) persistent challenges of microaggressions and benevolent sexism that complicate these efforts. Across themes, beliefs appear as visible markers, which configure everyday practices and are reproduced through congregational processes. Collectively, the findings depict empowerment as an interactive, multilevel reordering of congregational life rather than a singular decision to affirm women. Taken together, these structural, cultural/theological, and relational patterns recur in iterative cycles. We synthesize them as a Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women elaborated in the Discussion.

5.1. Structural Shifts in Leadership and Policy

In Baptist congregations, empowering women starts with how leadership and governance are structured. Churches in this study progressed gradually toward affirming women in pastoral roles, often moving from acceptance of women deacons to associate pastors before ultimately calling women as senior pastors. Alongside this progression, congregations created egalitarian staff policies that institutionalized gender equity, including inclusive hiring practices, flexible work arrangements, equitable leave provisions, and sexual misconduct policies. Many also adopted feminist organizational structures that resisted hierarchal models, embraced co-pastoring, and implemented consensus-based decision making. These structural transformations reflect theological commitment to shared authority and challenge traditional ecclesiologies rooted in patriarchy.

5.1.1. Shifting Perspectives on Women in Leadership

Several pastors (n = 5) in this study noted that their congregations progressed over years and decades to their full affirmation of women in ministry and leadership. Typically, churches in this study began with affirming women serving as deacons then progressed to women serving as associate pastors and finally affirmed women in the senior pastor role. For many of these congregations in this study, the women currently serving in the senior pastor role are the first to do so. Ellen, pastor of Atlantic Baptist Church noted,

She further explains, “They had women deacons…always women deacons…[and] at least since the 80s there has been a semi-regular presence of women in the pulpit.” It seems for many congregations, the jump from women serving in associate pastor roles to senior pastor roles is a large hurdle and one that can take decades to overcome.I was the first woman called as pastor here in 2019 for a congregation that has been supportive of women in ministry since its creation in 1953…That’s [more than] 60 years before they had their first woman pastor…They have had female associate pastors. They have had female interim pastors, but they’ve never had a [senior] pastor.

This gradual progression from women serving as deacons to associate pastors and eventually senior pastors often meant that when a woman did step into the senior pastor role, she was already a familiar and trusted presence within the congregation. This pattern of internal transition helped ease the shift toward full affirmation of women in senior leadership. Several churches noted that the first woman that served in the senior pastor role assumed this role after serving for a time as the associate pastor. Rachel, a long-term pastor of Urban Baptist Church, now retired, noted that she had an easier time with her congregation affirming her in the senior pastor role, “because I was on staff for so long in a very acceptable position.” Laura, pastor of East Baptist Church, explained that her church had woman in the associate pastor role that came to the church in the late 1980s “and she served as an associate pastor. And then, they ended up calling her as the as the pastor after the previous minister left.” These examples illustrate how the path to senior pastoral leadership for women was often paved by years of faithful service in associate roles, allowing congregations to grow comfortable with their leadership and ultimately embrace their transition to the senior pastorate.

In addition to women moving from associate to senior pastor roles, the presence of female pastoral interns also played a crucial role in shaping congregational openness to women in ministry. Georgia, one of the co-pastors of Second South Baptist Church, also credits the use of female pastoral interns for their congregation’s growing affirmation of women in ministry stating, “I think the number of young women who have come through here as interns, has made a difference in the culture. Because not only have they come as students; they’ve brought fresh theological, eyes, fresh liturgical work, energies, creativity.” By mentoring and empowering these young women, congregations not only benefited from their fresh perspectives and creativity but also fostered a culture increasingly receptive to women in pastoral leadership.

Another important step that several congregations (n = 6) noted was the intentional inclusion of lay women in congregational and lay leadership roles. Isabel of Western Baptist Church described her congregation as an empowering congregation for women because women have opportunities to serve in congregational leadership roles. She states, “this church has a long history of…women running committees, women making the church happen, women serving in leadership.” Ellen, when asked how she knew Atlantic Baptist Church was an empowering congregation for women simply stated, “The women were in leadership roles.” The consistent presence of women in key lay leadership positions may not only demonstrated their capability but may also normalized women’s influence and decision-making within the life of the congregation.

Simply having women in leadership roles may not be enough to ensure that the congregation’s environment is empowering for women. Intentionality to ensure that women, and congregants of diverse backgrounds in general, are given opportunity is needed, as clarified by Barbara, the associate pastor of South Baptist Church,

While the presence of women in lay leadership roles is an important step, true empowerment often requires a deeper commitment to intentional inclusivity and diversity in leadership representation.[the nominating committee] is very careful about [paying attention to] how many men are on there? Well, how many women are on there? What age groups are on there? Well are people gay and straight, you know, not necessarily ask that, but they’re paying attention to those kinds of things.

Women of the church have been doing the work of the church for a long time, often in the background. Intentionality to including women in congregational leadership roles must keep this work in mind as congregations provide leadership opportunities for women in their congregations. As Pam, the senior pastor of Urban Baptist Church states, “I think women feel tired from using all our gifts. We do all of the stuff of the church, you know? So, the environment, I think, is one of use your gifts and serve. And many of the women here are serving, I would say, in multiple capacities.” Recognizing and valuing the long-standing contributions of women is essential for creating truly empowering environments—ones where their leadership is not just welcomed but supported in sustainable and equitable ways.

5.1.2. Creating Egalitarian Staff Policies

Nearly every congregation in this study (n = 6) noted the importance egalitarian staff policies for creating an empowering environment for women in their congregations. Practices and policies mentioned included considering employee needs, inclusive hiring practices, implementing flexible work practices, establishing equitable leave policies, and enforcing sexual misconduct policies. For many of the participants in this study, churches with empowering environments for women consider what the women need when creating staff policies and “considers the total person and what their needs are,” as Barbara stated.

Developing Inclusive Hiring Practices

Congregations in this study (n = 3) implemented various hiring practices to ensure the hiring process was more equitable for women. The practices include expanding requirements for experience, implementing gender-blind resume reviews, and actively seeking women to fill pastoral roles. Barbara noted that South Baptist Church considers total experience stating, “I think they…want total experience in leadership, not just in title.” According to Quinn, when she went through the hiring process at Urban Baptist Church, “[the head of the search committee], had to black out any gender-identifying information.” Ellen also stated, “I know for a fact that when they were doing the search committee for [the former pastor] and it may have been for the pastor before him also, that [the head of the search committee], he was like, we must look for women pastors. We must receive resumes of women in ministry.”

Implementing Flexible Work Policies

Flexible work policies were highlighted multiple times by the participants (n = 6). These flexible work policies were both formal and informal and allowed flexibility in job expectations and schedules while maintaining accountability and allowing staff to balance work and family responsibilities. When asked to describe an empowering environment, Barbara from South Baptist Church described it as “one where flexibility in the job is built in, expected, inherent.” For Janice and Isabel, the ability to create their own hours empowers them, “Our hours are kind of what we want,” said Janice. Isabel further clarifies, “we can be flexible… but it doesn’t feel like anybody is like breathing down our necks or like watching us.” For Delores at Atlantic Baptist Church, flexible work hours and the opportunity to work remotely were necessary for her to even consider the position,

I want to do this job, but I need flexibility. And that was one of the things I remember we discussed. Yeah. Sundays and Tuesdays are requirements, but other than that, it’s teleworking. You know, your flexibility in terms of what you can do at home. But that was a huge part of me accepting the position.

Establishing Equitable Leave Policies

Establishing equitable leave policies for staff was a key component of creating an empowering environment of women in the congregations. Laura from East Baptist Church discussed how her congregation revised personnel policies to reflect the values of the congregation, “The Personnel Policy manual revision…was a work in progress for a number of years…we were trying to do something that was both aligned with our values of wanting to support women and families and also like something that was sustainable for the church.” Several congregations mentioned that they have non-gendered parental leave policies that offer flexibility in how the parental leave is used, “We have a parental leave policy in our church. Men or women can take 12 weeks off for parental leave, and they can decide within that first year how to use it,” describes Amber from South Baptist Church. Participants described having a variety of leave options as helping them feel empowered in their congregation. Amber discussed South Baptist Church’s foster leave policy “for anyone who is adopting a child or even just taking the foster child into the home.” Laura explained East Baptist Church’s sabbatical program that staff are eligible for every five years,

The policy clearly states that this is not something that you get for, like work done. It’s not something that you earn…the guiding principle of it is that the church believes that rest and renewal is essential for ministers and that the church wants to provide that. And, you know, one of the things that I appreciate about it is that it’s an option every five years. You know, a lot of places have it like every six or seven…and a lot of people don’t get to it…and…there’s a clause in it, you can’t work. And they don’t expect you to do or create something…It’s not like an academic sabbatical.

Enforcing Sexual Misconduct Policies

According to Baptist Women in Ministry’s latest State of Women in Baptist Life report (Baptist Women in Ministry 2022), “one in four respondents have been sexually harassed or sexually assaulted while working and serving in their ministry setting” (p. 7). It is no surprise that several of the respondents (n = 3) noted that enforcing sexual misconduct policies is vital to creating an empowering environment for women in Baptist congregations. According to Amber, South Baptist church provides sexual abuse training for all volunteers that work with minors and vulnerable adults. Barbara further explains, “We have a policy that is reviewed annually…our policy is not just for children and youth but includes vulnerable adults. And it’s annual. Everyone is subjected to an annual background check, and sexual abuse training that they must complete.”

Creating egalitarian staff policies is a crucial step in fostering empowering environments for women in Baptist congregations, as evidenced by the diverse policies implemented in the congregations in this study. From developing inclusive hiring processes, to implementing flexible work policies and creating various and equitable leave policies to creating and enforcing sexual misconduct policies, these congregations express their commitment to the well-being and safety of women in their congregation.

5.2. Adopting Feminist Organizational Structures

Nearly every congregation (n = 6) in this study has moved to more feminist organizational structures. Each congregation had their own particularities in how they did so. However, several common actions arose among the congregations including resisting hierarchical structures, embracing collaborative leadership, facilitating consensus building, and modeling feminine power.

5.2.1. Resisting Hierarchical Structures

Many of the pastors (n = 6) indicated that they are more comfortable with less hierarchical structures. Amber, senior pastor of South Baptist Church stated,

Resistance to hierarchical structures can take form in everything from reworking committees and governance all the way to simply how the names of staff are printed in the bulletin. Ellen and Delores of Atlantic Baptist Church discussed how they made this transition in their congregation:I don’t like the image of pastor as CEO. I don’t love hierarchical models of ministry where you have one person who is the authority…I’m most inspired by churches that have a more flattening structure, where my job is…to hold it all together. You know, to make sure this part’s functioning, this part is healthy. But my job is not to say this is how it’s going to be.

Ellen: After [the former pastor] retired, the bulletin, the staff list. It was listed, like, [senior pastor name], [associate pastor name]– like, all the other positions then after that.

Delores: Hierarchical.

Second South Baptist Church eliminated their personnel committee and supervision roles of the co-pastors altogether as Christine and Georgia explained:Ellen: Yeah. I was like, nope, there’s no reason for that. And, so I just put everything in alphabetical order because like, and that’s so subjective, like I don’t understand what subjectivity was leading to that list.

Christine: We don’t have a personnel committee.

These examples illustrate how resisting hierarchical structures fosters a culture of trust, shared accountability, and collaboration, reflecting a more egalitarian vision of church leadership.Georgia: And all of those policies exist somewhere, and nobody pays attention to them because there’s such inherent trust in the staff that we’re going to take the time off that’s provided. We’re not going to take advantage of that. We’re going to do our work. We’re accountable to one another. We don’t have supervising roles except for interns that, the [Divinity School] needs us to do. It’s much more…it’s a very collegial kind of thing…I haven’t said to anybody other than the other staff members I’m going to be on vacation in years. I mean, we make an announcement to the church but there’s not a need to turn something in.

5.2.2. Embracing Collaborative Leadership

This shift away from hierarchical models naturally paves the way for a deeper embrace of collaborative leadership, where decision-making, responsibility, and vision are shared across staff and congregation alike. Several churches (n = 4) have moved away from hierarchical models to co-pastor models. Both Second South Baptist Church and Western Baptist church function in a co-pastoring model and share responsibilities of the pastoral role. While other congregations may not have a stated co-pastor model, they function in much the same way. Delores, the associate pastor at Atlantic Baptist Church describes how this contributes to an empowering environment for her stating, “that is a very unique experience that I think contributes to the empowering environment is that there’s a safeness with Ellen, with the staff, with the way [Ellen] set up the dynamic in our staff. There’s a safeness there.” Ellen describes this environment further stating, “It’s just like in our nature, who we are. We cover for each other. Not in a way that drains any of us. But like, we cover for each other, and we don’t need to say anything else about it.”

A shift away from a hierarchal structure to a more flattened and collaborative structure does not necessarily mean a lack of organization. The co-pastors of Western Baptist Church learned this the hard way when their congregation decided to dismantle all church committees. Isabel explains,

I think that they thought…that there were a lot of proactive people in the congregation who would just step up to do things, and that is just not true. And they’re like, this is going to make things easier for the staff. It’s like, no. Now that we don’t have a worship committee, we don’t have a children and youth committee, we don’t have an education committee, Sunday-school, like any of that stuff. It’s all on us.

This experience illustrates that while moving toward a more collaborative model can foster inclusivity, it still requires clear structures and shared responsibility to prevent the burden from falling solely on leadership.

5.2.3. Facilitating Consensus Building

Most (n = 6) of the congregations in this study currently make decisions as a congregation through consensus building or are working towards this decision-making model, shifting from Robert’s Rules of Order which is a very structured process of motions, time for discussion, and majority vote decisions. As opposed to majority vote, consensus building seeks to work together to reach a decision that is acceptable to group members. Special attention is paid to ensuring that everyone’s concerns are addressed, allowing everyone in the group a sense of ownership of the decision.

Only one church within this study has fully moved to the consensus building model for congregational decisions and noted that the process is time consuming and requires more patience but is worth the effort. Most of the remaining congregations have made steps of varying degree toward instituting the consensus building model. Western Baptist Church learned about the consensus building model from their regional association of the American Baptist Church and has begun implementing the model at the committee level with the goal of moving it beyond committees to full church decisions.

South Baptist Church does not officially follow the consensus building framework. For larger or more contentious decisions, they institute elements of the model, as Barbara states,

I think we’ve learned that when there’s something potentially contentious or just a big change, that we don’t put it out there to the congregation or a vote immediately. What we do is educate the congregation, you know, have a lunch and learn, a listening session. Something to let people understand…so that people can have time to think about it and process it and understand what’s driving the need or the concern or the issue or, you know, whatever. Because usually if you give people time to digest, think, talk outside that, you know, then you can get around to knowing what the right thing to do is, or at least move people toward a time of decision, and then it gets done in a better way and all the things get talked about or considered.

5.3. Cultural and Theological Intentionality

Beyond structural change, congregations cultivated cultural and theological practices that reinforced gender equity. This included the use of gender-inclusive language for God, intentional choices in worship and liturgy (such as the adoption of women-centered lectionaries), and the rejection of gendered ministry groups in favor of inclusive alternatives. These practices signal a reimagining of God’s nature, scriptural interpretation, and congregational life in ways that expand theological horizons and create more inclusive environments.

5.3.1. Using Gender Inclusive Language for God

One way the churches in this study create empowering environments for women is through their language for God. Many (n = 3) avoid using male-centric language for God in prayers, sermons, and liturgy. As Barbara from South Baptist Church stated, “we try not to use male language to talk about God around here as much as possible so that people have a more open and free view of who God is as mother and father and that language is used in the pulpit and people will say it in prayers…Motherly Father or just praying to our Heavenly Mother.”

Other congregations (n = 2) in this study seek to move beyond a gendered view of God by using gender-neutral or expansive pronouns like they/them for God. For Janice, a co-pastor at Western Baptist Church, “a place is empowering for women when…we have an expansive view of God…having an expansive understanding of…God is many things.” Laura, the pastor at East Baptist Church, discussed how her church has a long history of using inclusive language for God and has used litanies that refer to God as they. Several pastors mentioned how they try to emphasize God’s transcendence beyond gender, “seeing God…rise above genders” as Amber of South Baptist Church stated. This intentional use of inclusive and expansive language not only reflects a theological commitment to gender equity but also fosters a more inclusive and empowering environment for women within these congregations.

5.3.2. Making Intentional Choices About Worship and Liturgy

In addition to using gender-inclusive language for God, congregations also demonstrate their commitment to empowering environments for women through intentionality in their worship and liturgical practices. Intentionality is key to this process as it implies awareness, thought, and deliberation behind decisions. For several congregations in this study (n = 3), intentionality in language and liturgy choices was paramount. Pam, the senior pastor of Urban Baptist Church, clearly emphasizes intentionality in reading and paraphrasing passage of Scripture,

Ellen from Atlantic Baptist Church also demonstrates deep intentionality and thought behind worship and liturgy choices,So, there is intentionality? Today in my sermon, the text of James said ‘Brothers and sisters.’ I said siblings intentionally. We don’t have to say it. But I was rephrasing scripture. I wanted to not reenforce male, brother and sisters, we’re siblings. And that’s talking about humans and not God, but it’s all sort of related. How much of that is sinking in? I would love to know. But I think it’s sinking in.

For these congregations, practicing intentionality in worship and liturgy goes beyond intentionality to language. They also practice intentionality through incorporating expansive and diverse theological resources. The pastors of Atlantic Baptist Church practiced intentionality in ensuring women’s voices were heard in worship and spent an entire year using Dr. Wil Gafney’s A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church, going so far as to purchase a copy for everyone in the church which they brought with them to church every Sunday. Other congregations noted that they are intentional to use gender-inclusive translations of the Bible in worship and center other marginalized voices.We were just talking about this, our sons and daughters, brothers and sisters and like now, right now since our Minister of Music retired at the end of May, now that I’m the one picking the hymns…I am having to spend a lot more time with them to…look at the language. Let me make sure it’s right…Do I need to change words here? So, we’re doing a lot more printing words than we used to because we’re trying to focus on that.

5.3.3. Rejecting Gendered Ministry Groups in Favor of Inclusive Alternatives

Several congregations (n = 3) in this study responded that they no longer separate the work of the church into gender-specific groups. Instead, they replaced gender-specific groups like women’s groups, men’s ministry, and men’s and women’s retreats with inclusive alternatives. For these congregations, the choice to create more inclusive alternatives derives from their desire to be a more inclusive environment. As Barbara stated,

Creating non-gendered groups can create a more inclusive and empowering environment, but it does create dissonance between the congregations and larger Baptist entities who create resources designed for gendered groups. Laura discussed this incongruence when reflecting on the mission work of her church,we don’t have any of those gendered groups. It just doesn’t fit. The language just doesn’t work here. I’ve even, you know, I have thought about sometimes like we should have a women’s retreat. And then I think now that leaves out too many people. So we end up having a spirituality retreat. And then anybody can go. Yeah, these gender groups just don’t really…it just doesn’t. It never has felt right coming out of my mouth around here.

Not having gendered groups- That’s just been the culture of the church…The missions committee laughs because we get these directions from the, the [Regional] Baptist Association…and they’re basically made for the women’s mission groups in the church. And we don’t have that. We have a missions commission. And so, we just kind of laugh about that. But that’s actually been one of the challenges of us, like kind of interfacing with the American Baptists is some of those kinds of structural things we just like don’t have.

Ultimately, the shift away from gendered groups reflects a broader commitment to inclusivity and empowerment, even as it presents challenges in navigating traditional denominational structures. This commitment to resisting gendered structures not only reshapes the organization of church groups but also reflects a deeper cultural shift—one that requires ongoing intentionality and long-term dedication to creating truly inclusive and empowering environments.

5.4. Relational Practice of Support and Education

Congregations also fostered empowerment through relational practices that nurtured both clergy and congregants. Women in ministry described the importance of peer support networks, mentoring partnerships, and congregational advocates who sustained them in their roles. Churches invested in education for children and youth around gender, sexuality, and embodiment, as well as congregational education on gender justice. Many pastors also emphasized the importance of calling out sexism directly, confronting double standards, and addressing internalized sexism among women themselves. These relational practices highlight how empowerment is sustained through interpersonal and communal bonds that shape the lived religious experience.

5.4.1. Developing Support Systems

Congregations in this study fostered empowering environments for women by developing various support networks for women. These support networks included peer support networks, church leadership support, and congregational support. Women in ministry often face significant isolation. Peer support networks help create connections among women pastors to combat this sense of isolation, provide spaces for personal and professional check-ins, and a way to share resources and advice. Christine shared that she and Georgia have been meeting with a group of women pastors for more than 14 years. She states,

It doesn’t happen every week. It doesn’t happen every month. But somebody will say, I got this thing, you know. Have you done a suicide funeral lately? You know what’s the language that we use? Or if I kill my husband, then will you all come see me in the penitentiary, or you know, my kid’s in therapy and I’m just so done with everything right this minute. Or, what’s something, please does somebody got an advent? Does anybody got an advent? And, you know those women put themselves out every year, sometimes more than once, to be in the same place together for several days where the agenda is checking in -sometimes hours at a time. You know, until we’ve caught up with each other and we know how to retain the connection that sustains us.

Participants (n = 3) described church leadership that is supportive of women and the women in ministry in the congregation as a key to creating an empowering environment for women. Amber at South Baptist Church noted that she has a liaison from the personnel committee she can turn to with issues, stating,

Ellen at Atlantic Baptist Church has a similar experience with her personnel committee, “I trust them completely…they check in with me all the time and our current chair of Leadership Council and Vice Chair of Leadership Council, I have conversations with them all the time.”And they help me figure through how to handle that…And if it’s an issue that needs to be addressed on a higher level for my own protection, that will be done. And if it’s just something I need to think through, like, how do I create a better boundary here? That person or the personnel committee can help me do that.

Georgia at Second South Baptist Church noted how church leadership stood up for her when she was called as a gay female co-pastor of her church, “they established a committee to kind of deal with publicity and said, ‘it’s ours to do. We’re not going to stick you out there in front of everybody to carry this.’” These examples show how vital role of supportive church leadership in fostering empowering environments for women in ministry, ensuring they have guidance, support, and protection needed to thrive in their roles.

Congregational support is an important component of an empowering environment for women, according to several participants. Congregation members can show support by cultivating visible encouragement through presence and participation, addressing practical needs to foster comfort and inclusion, and advocating for women’s leadership opportunities. During a stressful time at Second South Baptist Church, Christine and Georgia created a list of supportive congregants they could rely on and encouraged their visible support for the ministers. Christine stated,

we asked [them] to be committed in their attendance, that they would be here and that they would be a part of it, that they be in the church house because it helps us to see their faces. And we asked them to tell the good news. If you can’t stop a negative conversation, at least balance it with your own experience.

Other congregations (n = 2) had members advocate on behalf of women in leadership in their congregation. Ellen at Atlantic Baptist Church stated, “we have people who have been around causing good trouble around women in ministry here for a long time, because they’ve been saying for a very long time that this place needed to have a woman pastor.” Rachel, the former pastor of Urban Baptist Church, remembered a time before she was the senior pastor when a specific congregation member advocated for Rachel’s participation in worship, “I give a lot of credit to one member…who, when I started as the children’s worker, she is the one who went to the senior pastor and said, ‘why aren’t you using Rachel in worship?’ and I started telling the children’s sermon.” Congregational support plays an integral role in creating an environment where women can feel valued, included, and empowered in leadership roles.

5.4.2. Educating and Addressing Gender Issues

Participants noted that addressing gender issues in various ways in the life and work of the church are integral aspects to creating an empowering environment for women. Participants mentioned that preaching on gender equity, reinforcing women’s empowerment as a congregational value, educating children and youth on gender and sexuality, educating the congregation on gender issues, calling out and addressing sexism, and checking internalized sexism were important aspects of fostering empowering environments for women.

Several (n = 3) congregations pointed to addressing gender issues and gender equity in their sermons as a way they seek to build an empowering environment for women in their congregation. Janice at Western Baptist Church noted at times she or Isabel will preach sermons, “lifting up different texts that centralize ‘women’s issues’ or theological stances.” Other churches noted that preaching on gender equity is part preaching about justice. Christine from Second South Baptist Church said,

Ellen expressed the same sentiment about situating preaching about women’s equality in justice stating, “I largely preach, obviously, from a White western feminist perspective, but I also try to bring in womanist theologians, and a variety of voices. And I can remember so many women coming to me and saying, ‘I’ve never heard a sermon like that before.’” Preaching about gender issues and gender equity is crucial for cultivating an empowering environment for women within congregations. For Rachel, in her tenure as senior pastor at Urban Baptist Church, consistently preaching on how all people are made in the image of God instilled gender equity into the congregation.we try to do this sermonically too, but I’ve preached several times about being racist because I am. I don’t want to be. I’m trying not to be, but I am. I preached one sermon that was entitled ‘The Otherist.’ I was like, ‘I’m an -ist about every single thing that is not…a 51-year-old, White, straight woman Baptist Pastor in the South. Everybody else is other.’

A few pastors (n = 3) noted that educating children and youth on gender and sexuality in their church was important for fostering an empowering environment for women. Some described promoting body positivity and avoiding gendered dress codes and body shaming, others described how they are providing sexuality education, using inclusive language and diverse imagery in faith formation, and others are offering children’s resources that highlight both women’s and men’s roles.

Delores at Atlantic Baptist Church explained how she talks about God with the children in her congregation, “[It’s about] faith formation and how we talk about God to our children, right? Mother God. Father, not just Father God, but a lot of mothering language and trying to use neutral, nonbinary language and talking about Creator God.” Sarah at Urban Baptist Church describes how she uses children’s resources to create an empowering environment for women with the children in her church,

I would say at least using the children’s Bible that we have, they have really solid stories of women roles, and they have really solid men roles. And I think it’s helpful for them to see both sides…and then I think just relating it to their everyday life…where do you see this in your life?

Youth group rules about gender appropriate dress can also be a sticky situation for congregations seeking to empower the women in their youth groups. Many congregations have rules on what the youth, especially female youth can wear, for example, one-piece swimsuits for girls yet boys can be bare chested when swimming, no spaghetti straps for girls in worship, and other gendered clothing rules. Often, these rules place more restrictions on female youth and hold them responsible for the actions of male youth. Barbara discussed this quandary she faced,

These congregations want their youth to be empowered in their knowledge of sex. Several hold sexuality seminars for their youth groups or sexuality retreats, wanting their youth “to think that church is a safe place to have these conversations. We want them to be properly educated about their own bodies, sexuality, biology, consequences,” Barbara stated. These congregations are actively working to create empowering environments for women among their children and youth by promoting gender equality, fostering body positivity, providing comprehensive sexuality education, and ensuring that all children and youth can engage in faith formation free from harmful gendered expectations.I think our [summer camp] experience really influenced me on that. Like, I did not want to have a lot of rules about what kids can wear, and I certainly did not want to make any girls more responsible for their bodies than the males were…under my leadership, there’s never been any you know, swimsuit rules or what you could wear or couldn’t wear. I have only ever talked about kids standing up in front of the congregation. And I’m like, just think about how short whatever you’re wearing is. You know, you’re up here and they’re down here. I mean, just do the math. But like just being real careful about body shaming and not wanting girls to have to take more responsibility for what they wore than anybody else. But it’s been very intentional, very intentional.

Another practice that participants (n = 2) mentioned is educating the congregation on gender issues. The churches did this in various ways including providing educational opportunities on gender and sexuality, promoting awareness of challenges faced by women in ministry, and intentionally amplifying women’s voices through lectionaries and resources. Laura from East Baptist Church shared how they brought in outside help for their educational opportunities, “we’ve done education around these kinds of things and around sexuality around language…we’ve brought people in to do some of those things, from different organizations here in town.” Ellen discussed how her decision to reorder the staff list in the bulletin was an educational opportunity, “I was like, you guys noticed that? And I was like, well, here’s why I changed the staff list.” These examples show that educational opportunities come in many forms, some may be larger like training and educational programs, others may be smaller, like taking a moment to explain a decision and why it’s important. Both formal and informal educational practices are needed to develop empowering environments for women.

5.4.3. Calling Out Sexism

Another practice that several (n = 3) participants noted has helped develop empowering environments for women in their congregation is calling out and addressing sexism as it occurs. Participants have named and addressed sexism in their congregation both on the individual and corporate level including addressing sexist language and behavior in personal interactions, encouraging direct and honest communication, confronting gender-based double standards and unequal treatment, and naming and challenging paternalism and undermining of women.

For many women, it takes time to learn how to address sexist language and behavior in personal interactions. For Christine at Second South Baptist Church, she realized, that it needs to be addressed in the moment and “when something is said going, ‘Ow ow ow ow ow ow! That’s gonna leave a bruise!’” For both Christine and Georgia, honest and direct communication works best, “You can say, ‘that’s really not a nice thing to say.’ Or say ‘we don’t talk about each other like that.’ And we put some mantras in people’s mouths. We said, you know, one of the things that you can always say is when somebody complaining about me, ‘What did Georgia say when you talked to her about that?’” explained Christine.

Several participants also discussed that confronting gender-based double standards helped create empowering environments for women. Janice of Western Baptist Church discussed a time when she asked a congregation member to consider Janice’s and Isabel’s perspectives,

Christine shared a similar experience she and Georgia faced in confronting gender-based double standards,I said, I want to ask you something. Can you put yourself in our position? You are the first women pastors in this church. You are heads of staff, you’re new, and somebody goes behind your back to start a new position and does it all behind your back without your knowledge, all of it, to put a full-time person on your staff. Not one conversation, not one. And I say, can you put yourself in our position and imagine? And we even said in that conversation, that if we were men that wouldn’t have happened.

Empowering environments for women cannot be fostered in Baptist congregations if people in the congregations do not call out, confront, and address sexism as it occurs. Unchecked, this can lead to an environment that may seem empowering yet is one that is completely unexamined.We sat in one of those personnel committee meetings from hell during the years from hell. And after, after something was going on, Georgia said, ‘I just wonder…’ And said it kindly because she’s kind. She said, I just wonder if you would be asking [the former male pastor] these questions?’ He’s the pastor we followed. And they lit up like a Christmas tree. ‘That’s just crazy. That’s just crazy. How could you say that to us?’

5.4.4. Checking Internalized Sexism

Sexism against women in Baptist congregations is not relegated solely to those who are not women. Women themselves are often perpetrators of sexism against other women stemming from internalized sexism. A couple of participants (n = 2) in this study realized that they must continually examine their own internal sexism. Barbara from South Baptist Church recalled,

Pam from Urban Baptist Church recalled having to confront her own internalized sexism in her interactions with couples in her church,I have recently recognized and called out in myself and called it in others or offered it as ‘I wonder if you’re doing the same thing I’m doing?’, which is I don’t expect boys to behave as well as I expect girls to behave. And I think I’m being very gendered in my comment right there to say that this child… I wonder if they had been born male…If we would be making more excuses for their behavior or seeing it as normal, instead of seeing it as problematic and challenging because it is not what we would expect from a girl child.

For Baptist congregations be empowering environments for women, all women must be willing to analyze and address their own internalized sexism. Sexism in any form is a barrier to developing environments where women are empowered.I think about couples in the church where, if they are a hetero couple, the man is very outgoing and in a lot of leadership roles. I notice a trend in myself that when I see the both of them, I tend to just talk to the husband and see what his needs are and how he’s doing. And the wife, I find, doesn’t say as much. And I haven’t checked in [with her] in six months because I only talk to the husband. So, things like that happen, where I just have to check myself. Making sure I address both of them, or call the wife separately and see how she’s doing…Ask her about her gifts and skills, would she like to be in leadership?

5.5. Persistent Challenges and Microaggressions and Benevolent Sexism

Despite intentional structural, cultural, and relational shifts, participants consistently reported the persistence of gender microaggressions and benevolent sexism within their congregations. Women pastors describe how comments on appearance, subtle undermining of authority, and paternalistic attitudes continued to shape their ministerial experience, even in congregations deeply committed to gender equity. These findings underscore the resilience of patriarchal patterns within religious life and the ongoing need for vigilance, reflection, and cultural change.

Most of the congregations (n = 6) in this study have intentionally worked to create congregational environments where women are empowered. These congregations have addressed structural and theological issues that have disempowered women in Baptist congregations for hundreds of years. Yet, deeply entrenched patriarchy remains, even in some of the most empowering congregations. Participants (n = 7) noted that the influence of patriarchy is felt most acutely through gender microaggressions and benevolent sexism, “even in a place that’s really empowered people so well…, there are these subtle little things that are not as easily noticed,” stated Laura of East Baptist Church. Ellen from Atlantic Baptist Church notes a similar experience,

Several other participants echoed these sentiments, including Janice from Western Baptist Church stating, “I think they think they are very empowering for women…while it can be empowering at times…we still have a lot of work to do.” In fact, Janice and her co-pastor Isabel, took their concerns to their church council by submitting examples of microaggressions they continually face. Isabel explains,Even in a congregation like this, that is wonderful and safe and great. There are still everyday moments of sexism in the way that we’re approached and treated. And if we made a list of them and read them to the congregation, they would be horrified, because they would [say] that’s not us, we don’t do that, and it’s all the time.

And we’ve recently been more explicit about some of things that have been challenges, and really disheartening for us, especially this spring…. actually submitted it in writing and verbally of here are some things that we’re dealing with. These are the types of things that we’re hearing and receiving regularly. And this is how it makes us feel. And the council needs to know that that is the status of how it is. And they were very concerned and caring, and shocked. I do feel like the jury’s still out on whether it will prompt any change or any action so kind of way. But we’ve been very honest with them.

A majority of participants in this study mentioned that congregants comment on their looks. As Quinn, a pastor of Urban Baptist Church commented, “We do as women still get the condescending comments of like, ‘you look cute today.’ ‘I like your skirt.’ ‘I like your outfit.’ ‘You’re so pretty.’ You know? Kind of like, she is like my granddaughter.” Sarah, Urban Baptist Church’s children’s pastor added, “You would never say that to a man…You still have probably been looked at inappropriately, touched inappropriately, had inappropriate comments…we’ve had to process that they coexist”. Laura mentioned how even after having her head shaved for skin cancer treatments, she had people commenting on her appearance stating, “And it never failed. Like all the comments about whether they like it, they don’t like it. What’s under there? You know? It just felt a little violating at time. Where it’s like can we just get over this?”

These persistent comments, often framed as compliments, reveal how women in ministry within Baptist congregations are frequently reduced to their appearance, undermining their professional identity and highlighting the lingering presence of gender microaggressions even in otherwise supportive congregations. Gendered microaggressions not only challenge the professional identity of women in ministry but also raise broader questions about the legitimacy of their ministerial roles, prompting further examination of how their authority is perceived and questioned within the congregational setting. While these congregations have made significant strides toward empowering women, the persistence of subtle gender microaggressions and benevolent sexism underscores the ongoing challenge of fully dismantling patriarchal structures and achieving true equality in Baptist settings.

6. Discussion

Building on Cornwall’s (2016) empowerment spiral and Carr’s (2003) praxis-oriented framing, we propose a Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women (Figure 1) to interpret how Baptist congregations cultivate environments in which women can flourish. Consistent with constructivist grounded theory, this is an interpretive model co-constructed from participants’ accounts and our feminist/theological lens.

Figure 1.

The Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women.

6.1. The Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women

6.1.1. Phase 1: Visibility and Vocation

Congregations begin by making women’s gifts and authority publicly recognizable in the settings that carry the most symbolic weight: preaching, presiding at the table, baptizing, officiating funerals and weddings, moderating meetings, and presenting institutional reports. Repeated, embodied leadership in these spaces catechizes the community; over time, congregants revise their mental picture of who a pastor is and what leadership looks like. This movement aligns with feminist theological claims that Imago Dei and gifting of the Spirit are not gendered.

An intentional focus to who takes on high-visibility roles, like a planned annual calendar, can help at the start. The goal is not to check boxes across a calendar, but to practice sustained intentionality so that shared leadership becomes ordinary. Pairing these visible moments with explicit narration in worship that what we do teaches what we believe helps prevent tokenism and role segmentation that consigns women to back-stage or caregiving tasks. Practical signals also matter. Bulletin layouts, website architecture, staff bios, announcements scripts, and photo order should reflect parity so that communications reinforce what is enacted in worship.

Congregations can monitor progress with a few concrete indicators: the share of Sundays in which women preach, the distribution of high-symbolic roles across a season rather than only on special days, and congregant perceptions of women’s authority gathered through brief surveys or listening sessions. Youth focus groups are especially useful since they often reveal how expectations are changing across generations. If data show concentration in a narrow set of roles or a drop off after an initial push, leaders can recalibrate by returning to the intentionality principle and using the schedule again as a temporary scaffold until habits take hold.

6.1.2. Phase 2: Theological and Liturgical Reframing

As visibility grows, theological and liturgical language must catch up so that the congregation’s speech about God no longer subtly contradicts what it enacts. Inclusive God-language, women-centered lectionaries, and intentional worship choices re-teach the congregation’s theological imagination. Here, belief and practice merge, what the church prays shapes what it believes about God and who may bear public authority. These practices concretize feminist theology in lived congregational life.

Because liturgy habituates doctrine, small changes repeated over time matter more than occasional “special” services. A simple starting point is an inclusive-language audit of prayers, readings, printed and online materials. Teaching series on Imago Dei, calling, gifts, and shared authority provide theological grounding so that practice does not outrun conviction. The real risk is doing surface tweaks or changing a few words up front while leaving the big ideas and images untouched, or fixing the spoken parts but ignoring other places where people learn how a church talks about God, like websites, bulletins, and other printed materials. If we only change the language in worship and do not update these other forms of communication, people still absorb the same old metaphors about God.

6.1.3. Phase 3: Organizational Redesign

Durable change requires translation from worship and liturgy into policy and governance. Organizational redesign incudes equity through collegial leadership norms, co-pastoring, consensus-seeking facilitation, transparent agendas and minutes, inclusive and structured hiring, clear pay bands, non-gendered parental leave, flexible work expectations, and robust misconduct prevention and enforcement. When criteria are known in advance and processes are written down, bias has fewer places to hide; when facilitation distributes voice, informal power brokers face limits. A minimum viable policy set adopted by the congregation and practiced, not filed away, keeps equity from depending on goodwill. Structured interviews tied to job-relevant rubrics, published compensation ranges, and annual reviews that include equity metrics are straight-forward tools. The predictable pitfalls are performative policymaking where policies exist on paper but there are not systems in place to operationalize policies. Congregations can gauge progress with simple indicators: the presence and use of key policies, pay-equity ratios, documentation of shortlists and interview rubrics, the proportion of major decisions taken with consensus protocols, and time-to-resolution and perceived fairness in misconduct cases.

6.1.4. Phase 4: Relational Support and Formation

Policy creates guardrails, but relationships transmit norms. Women clergy need structured peer support that meets regularly and does not rely on them to facilitate their own care. Churches should identify and train lay allies who will step in publicly, so the work of calling out harm is not placed on the women who were hurt. At the same time, children and youth benefit from age-appropriate formation on gender, embodiment, consent, and vocation; this anticipates the church the congregation hopes to be in ten years, not only next Sunday. Evidence of traction includes attendance and reported usefulness of peer groups, incident logs that note ally intervention in real time, and artifacts from the youth curriculum alongside short attitude measures.

6.1.5. Phase 5: Reflection, Repair, and Accountability

Even in communities committed to equity, microaggressions and double standards persist. The difference between drift and growth is whether congregations build ordinary habits of naming harm, repairing trust, and learning in public. Multiple reporting pathways, trained responders who can use in-the-moment language that deescalates and acknowledges harm, and proportionate, transparent follow-through teach the church that accountability is part of discipleship rather than a threat to unity. Periodic culture checks surface patterns that individual stories can conceal, and restorative processes help the congregation move beyond blame toward change.

6.1.6. Consolidation and Witness

As practices stabilize, the congregation begins to tell its story differently. Equity becomes part of identity and public witness, not a project with an end date. Vision statements, testimonies, ordinations, denominational service, and partnerships all signal that women’s authority is assumed and celebrated. External witness feeds back into internal accountability, since telling the story in public makes backsliding harder to rationalize. Congregations can mark consolidation by incorporating milestones into annual reports and annual meetings, budgeting for mentoring and resource-sharing with peer churches, and noting where their policies and practices have been adopted elsewhere.

The spiral clarifies why isolated changes (e.g., a single hire or one season of inclusive liturgy) yield fragile gains, while aligned shifts across theology, worship, structure, and relationships generate compounding effects. It also explains the apparent paradox in our data: strong commitments can coexist with everyday sexism unless feedback and repair are institutionalized.

The findings substantiate a core claim of feminist theology: transforming God-language and symbolic worlds is not ornamental but constitutive of justice in the church (Daly [1968] 1986; Pierce et al. 2021; Ruether 1983). Liturgical and homiletical choices recalibrate who is intelligible as a leader before God’s people. Ecclesiologically, resisting CEO-style pastoralism in favor of collaborative and consensus-based models enacts a shared vision of church, redistributing authority in line with the body’s many gifts. From a lived-religion perspective, the data show how everyday practices like bulletin layouts, staff policies, pronouns in prayer, who speaks and who is interrupted, train a congregation’s moral and theological imagination as surely as formal doctrine.

At the same time, persistent microaggressions and benevolent sexism confirm that structural sin outlives structural reform. Theologically, empowerment appears not as a one-time achievement but as a practice of communal sanctification, repeated acts of truthful speech, repair, and re-commitment that keep the congregation aligned with its stated beliefs.

6.2. Practical Implications for Congregations

For congregations seeking durable culture change, the spiral suggests beginning where belief is most powerfully formed: worship and teaching. An intentional audit of language for God, Scripture, and liturgy. This audit, paired with preaching and formation that center the Imago Dei, call and gifts, recalibrates the theological imagination that underwrites practice. Structural codification should then translate conviction into policy: transparent and gender-blind hiring, equitable and flexible work norms, non-gendered parental leave, clear compensation practices, and robust misconduct prevention and enforcement reduce reliance on discretionary goodwill and make equity less personality-dependent.

At the same time, culture change is relational. Peer networks for women clergy, visible lay allyship, and age-appropriate formation for children and youth around gender, embodiment, and sexuality provide social reinforcement and a future-oriented horizon for the congregation. Finally, institutionalizing feedback and repair, like clear and safe reporting channels, normalized “in-the-moment” response language for microaggressions, periodic culture checks, and public follow-through, keeps the congregation from drifting back to patriarchal default settings. Church council or personnel committee leaders might regularly ask where women’s authority is informally contested; which policies still depend on discretion rather than criteria; how often bias is named in public, not only in private; and what elements of worship and congregational communication are forming (or deforming) the congregation’s imagination toward equity. These moves are mutually reinforcing; progress on several fronts as once is far likelier to consolidate gains than piecemeal action.

6.3. Implications for Theological and Ministerial Training

The congregational empowerment spiral also maps onto ministerial formation. Seminaries and continuing education programs can cultivate theological competence (inclusive God-language; feminist and womanist hermeneutics; ecclesiologies of shared authority), organizational competence (facilitation for consensus, equity-oriented policy design, and change leadership in congregations), and pastoral competences (responses to microaggressions, boundary-setting, ally cultivation, and trauma-informed practice). These capacities are best formed not only through readings and lectures but through praxis: liturgical audits and rewrites, case-based simulations of consensus decision-making, supervised projects that revise personnel manuals and pay structures, and rubric-based evaluation of inclusive preaching and worship planning. Framed this way, the curriculum equips ministers to move congregations through successive turns of the empowerment spiral rather than treating equity as a one-off initiative.

7. Conclusions

This study traced how Baptist congregations cultivate empowering environments for women through shifts in theology, worship, structure, and relationships. Adapting Cornwall’s empowerment spiral and Carr’s praxis-oriented framing, we proposed a Spiral of Congregational Empowerment for Women that explains why visible leadership, inclusive God-language, egalitarian policies, relational supports, and practices of reflection, repair, and accountability practices must align to produce durable change. Even in congregations committed to equity, microaggressions and benevolent sexism persist unless congregations institutionalize ways to name harm, correct course, and rebuild trust. Congregations consolidate change when theological reframing is translated into policy and governance, when networks of allyship are cultivated, and when accountability become ordinary practice. The model also maps onto ministerial formation, calling for integrated development of theological, organizational, and pastoral competencies. Future research should test and refine the spiral across traditions and settings, attend to intersectional dynamics of race, class, sexuality, and disability, and examine diffusion and durability over time. Empowering women in congregational life is not ancillary to ecclesial identity; it is integral to the church’s faithful witness in public and over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.E.D.; Methodology, H.E.D.; Validation, J.W.W.; Formal analysis, J.W.W.; Data curation, H.E.D.; Writing—original draft, H.E.D.; Writing—review and editing, J.W.W. and G.I.Y.; Project administration, H.E.D.; Funding acquisition, H.E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethic Committee of Baylor University (Approval Code: 2156605; Approval Date: 2 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The transcriptions would not be available due to adhering to the participant’s confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ammerman, Nancy Tatom. 2021. Studying Lived Religion: Contexts and Practices. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baptist Women in Ministry. 2022. State of Women in Baptist Life Report. Available online: https://bwim.info/state-of-women-in-baptist-life-report/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Barr, Beth Allison. 2021. The Making of Biblical Womanhood. Ada: Brazos Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Matt. 2019. Flourishing in Ministry: How to Cultivate Clergy Wellbeing. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, E. Summerson. 2003. Rethinking empowerment theory using a feminist lens: The importance of process. Affilia 18: 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, Andrea. 2016. Women’s empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development 28: 342–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custis-James, Carolyn. 2011. Half the Church: Recapturing God’s Global Vision for Women. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Mary. 1986. The Church and the Second Sex. Boston: Beacon Press. First published 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, Elizabeth. 2016. A “true Baptist” theology of women in ministry. Baptist History and Heritage 51: 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lauve-Moon, Katie. 2021. Preacher Woman: A Critical Look at Sexism Without Sexists. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]