A 19th-Century Representation of Identity: An Evaluation of the Architectural Design of the Yüksek Kaldırım Ashkenazi Synagogue (Austrian Temple) in Istanbul

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. An Overview of Orientalist Tendencies in Synagogue Architecture After Emancipation

3. Ashkenazi Jews in the Ottoman Empire and Their Architectural Practices

4. Architectural Analysis of the Yüksek Kaldırım Ashkenazi Synagogue in Istanbul

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

| 1 | Additionally, Turkey is not mentioned in Carol Herselle Krinsky’s standard work Synagogues of Europe (1985), and this study contributes a new perspective by placing Istanbul within a European context. |

| 2 | The term Convivencia was introduced by Américo Castro to describe the period in Spanish history from the Umayyad conquest of Spain until the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. Carrying meanings such as “living together,” “coexistence,” and “communal life,” the concept was later taken up by 19th-century thinkers, who regarded it as an idealized model of social coexistence in the modern age. For further details, see (Wolf 2009, pp. 72–85; Nirenberg 2024, pp. 1255–77). |

| 3 | Various publications have criticized the expression “Golden Age” for presenting a one-dimensional and idealized perspective, arguing that it oversimplifies a complex period with both positive and negative aspects. These texts often point out that political oppression, social restrictions, and episodes of violence during that time tend to be overlooked. Although Jews were granted protection of life and property under Islamic law as dhimmis (non-Muslims under protection), they were not afforded social or political equality. Thus, the period’s negative dimensions must also be taken into account. On the other hand, it has also been noted that Jews in this era enjoyed greater religious and cultural opportunities compared to their counterparts in Christian Europe. The use of Arabic as a shared language in science and philosophy encouraged the development of Jewish intellectuals. Additionally, the fact that Jews were not the only minority in the pluralistic Islamic society reduced the risk of being targeted. These factors are cited as positive aspects of the period (see Ben-Sasson 2004, pp. 123–37; Cohen 2008, pp. 28–38). |

| 4 | In her doctoral dissertation, Jeanne-Marie Musto drew attention to the impact of the synagogue’s design on the shaping of synagogues belonging to Jewish communities in Bavaria and beyond (see Musto 2007, p. 374). |

| 5 | It is known that one of the first synagogues built in Paris after Jewish emancipation was vacated by its congregation due to the actions of the property owner, while the other was demolished in the 1850s due to the threat of collapse. Therefore, definitive information regarding the architectural styles of the synagogues constructed during the early phase of legitimization in Paris is lacking (see Jarrassé 2004, p. 44). |

| 6 | The first use of the term Rundbogenstil can be found in Heinrich Hübsch’s article (Hübsch 1828). The “Rundbogenstil,” or “round-arch style,” which he defined as a German nationalist architectural style, lacks a clear explanation regarding what exactly it entails and its boundaries. This ambiguity has at times led to the assertion that the style belongs to either the Neo-Romanesque or the Neo-Byzantine traditions, depending on its compositional substyles. (For example, while Kathleen Curran titled her book Romanesque Revival, she discussed the development of Rundbogenstil within it and stated that she used the terms “Romanesque” and Rundbogenstil interchangeably. See Curran (2003, pp. XXV–XXVI)). For an explanation of the source of this confusion, see Walther (2004, p. 18). On the other hand, some scholars have pointed out distinctions between Rundbogenstil and these attributed styles (Bullen 2003; 2004, pp. 146–47). However, these writings do not provide clear information on the diversity of substyles and their modes of application. |

| 7 | All theoretical and physical analyses leading to this observation can be found in the doctoral dissertation prepared by the author. See Akın Ertek 2025 (See also Dénes 1984, pp. 155–57; Klein 2017, pp. 111–12). |

| 8 | For example, in Pierre Genée’s book and Sergej R. Kravtsov’s article, synagogue examples that we classify under Rundbogenstil are attributed to Romantic Historicism (see Genée 1992, p. 56; Kravtsov 2010, pp. 81–100). Detailed information about Rundbogenstil and synagogue examples constructed in this style is provided in the doctoral dissertation prepared by the author. See Akın Ertek 2025. |

| 9 | In addition, it is observed that building permits were issued for the establishment of schools in various regions of the Ottoman Empire, as recorded in the Presidential Ottoman Archives. See For the town of Tripoli (Trablusgarb), COA, ŞD., 2338, 11. |

| 10 | In his article, Aşkın Koyuncu emphasizes that it would be incorrect to claim that these restrictions stemming from Islamic law were strictly enforced across all regions under Ottoman rule. He draws attention to the fact that variations in implementation could occur depending on how a region came under Ottoman control, its population and demographic structure, geographical position, as well as its social, economic, commercial, and political expectations (see Koyuncu 2014, p. 37). |

| 11 | Instead of obtaining fatwas from the Shaykh al-Islam’s office, petitions for construction began to be submitted to the Fetvahane (see Koyuncu 2014, p. 54). |

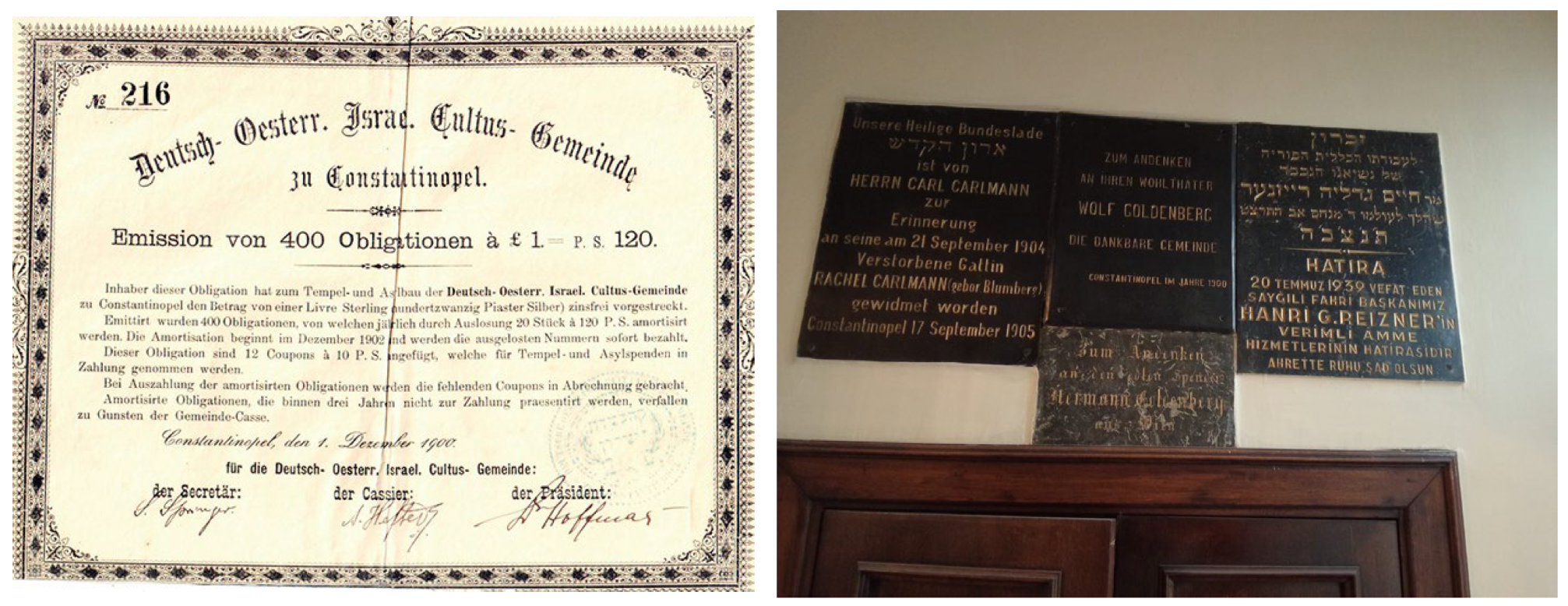

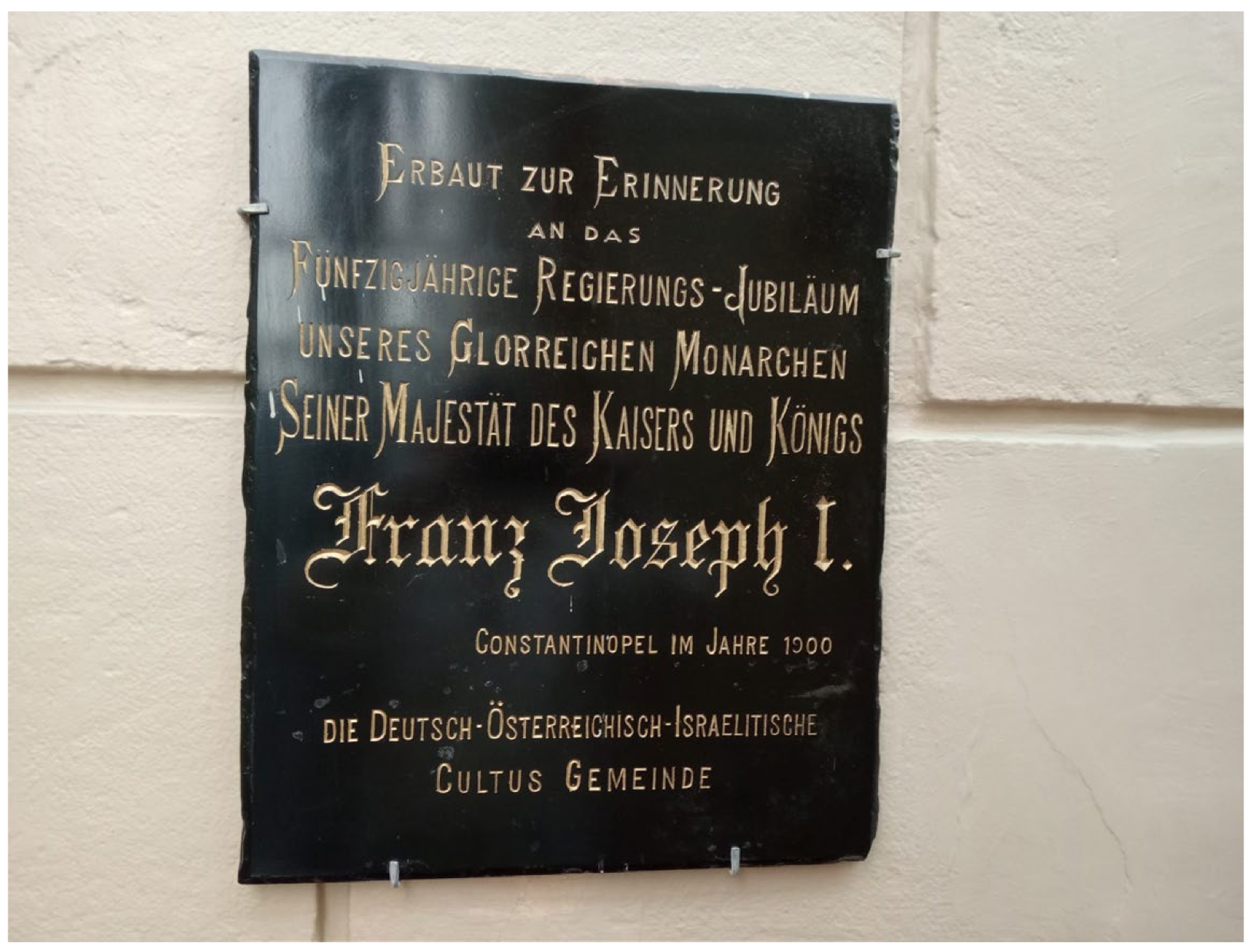

| 12 | It is not known whether this informational plaque in the synagogue was added in recognition of Franz Joseph I’s support during the construction of the sanctuary (see Schild n.d.; Güleryüz 2018, pp. 183–84). |

| 13 | In various sources, the Italian architect Gabriel Tedeschi is mentioned as the designer of the building (see Sezer and Özyalçıner 2010; Kırıcı Tekeli 2020, p. 757). In this context, the ambiguity surrounding the architect of the building remains unresolved due to the lack of documentary evidence. However, the presence of the name of architect G. J. Cornaro on a plaque within the synagogue, along with statements made by synagogue officials, provides grounds for attributing the building to him. It is known that Gabriel Tedeschi constructed buildings for the Camondo family (see Sönmez 2006, pp. 298–99). Nevertheless, there is no available evidence indicating that he was the architect of the Ashkenazi Synagogue. As for G. J. Cornaro—about whom we know nothing apart from his Venetian origin—his name appears on another example of civil architecture in Neoclassical style located on Meşrutiyet Street (see Arpacı 2020, pp. 165–68). |

| 14 | For various perspectives on the origins of horseshoe arches, see Holland (1918, pp. 378–98). |

| 15 | These columns represent a type that was characteristically used in the architecture of the last Islamic dynasty that ruled al-Andalus between 1238 and 1492. The form—sometimes referred to by the name of this dynasty—consists of two distinct sections: a rounded lower part and a rectangular upper part. For further details, see Sánchez (1999, pp. 177–29). For comprehensive studies on Maghrebi column capitals, see Maldonado (n.d.a), http://www.basiliopavonmaldonado.es/Documentos/Capiteles.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024); Maldonado (n.d.b), http://www.basiliopavonmaldonado.es/Documentos/Capiteles2.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024). |

| 16 | Sánchez The capitals of the columns at the portal of the Griechenkirche zur Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit are articulated in two tiers: the lower tier is animated with a row of protruding triangular forms, evocative of muqarnas-filled Islamic capitals. Numerous examples of such muqarnas-filled capitals can be traced across a wide array of structures within the Turkish and broader Islamic architectural geographies. The second tier incorporates compartmentalized sections created by extending the archivolts of the door arches, within which figurative elements are placed. This design recalls the figurative capital compositions commonly observed in early medieval European architecture. The portal columns of the Christuskirche present a variation in the lower-tier triangular projections—resembling muqarnas—that are also seen on the Griechenkirche’s capitals, though here applied as a single-layer motif. The columns of the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, in both shaft and capital composition, represent further variants of the column designs employed by the architect in his other works, blending classical form with orientalist and medieval stylistic influences. |

| 17 | Given the territorial scope of the Ottoman Empire—particularly including North Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries—it is not surprising that design elements such as horseshoe arches or ornamental motifs, which would later define Orientalist architecture, were already familiar. However, what is being emphasized here is that such features were not typically employed in the architectural traditions that evolved in Anatolia during the Classical Ottoman period. For detailed studies on Ottoman architecture, see Aslanapa (2004) and Kuban (2021). |

| 18 | For detailed information on the transmission of Orientalism to the Ottoman Empire and relevant architectural examples, see Germaner and İnankur (1989); Saner (1998); Batur (2001, pp. 42–43); Çelik (2005); Özkan Altınöz (2014, pp. 837–52; 2017, pp. 155–58). |

References

Archival and Figure References

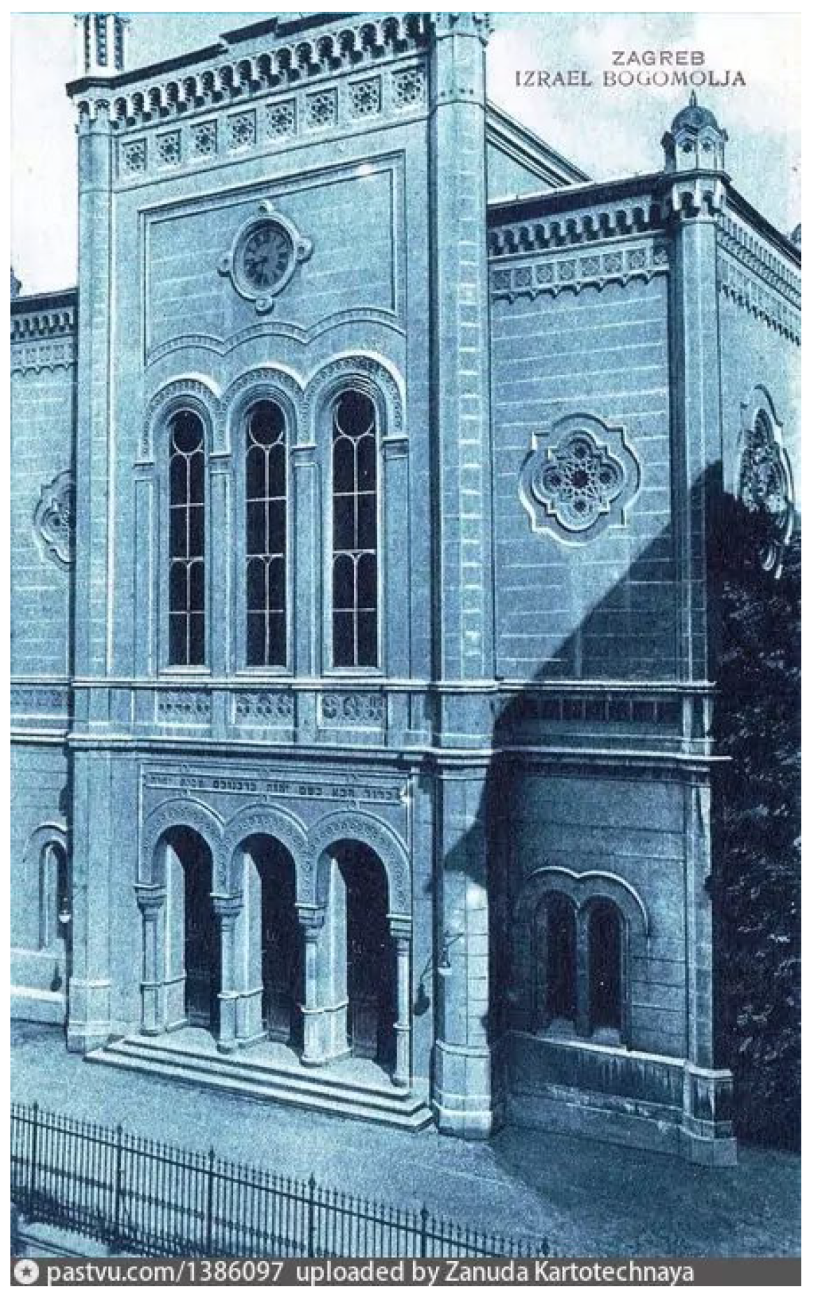

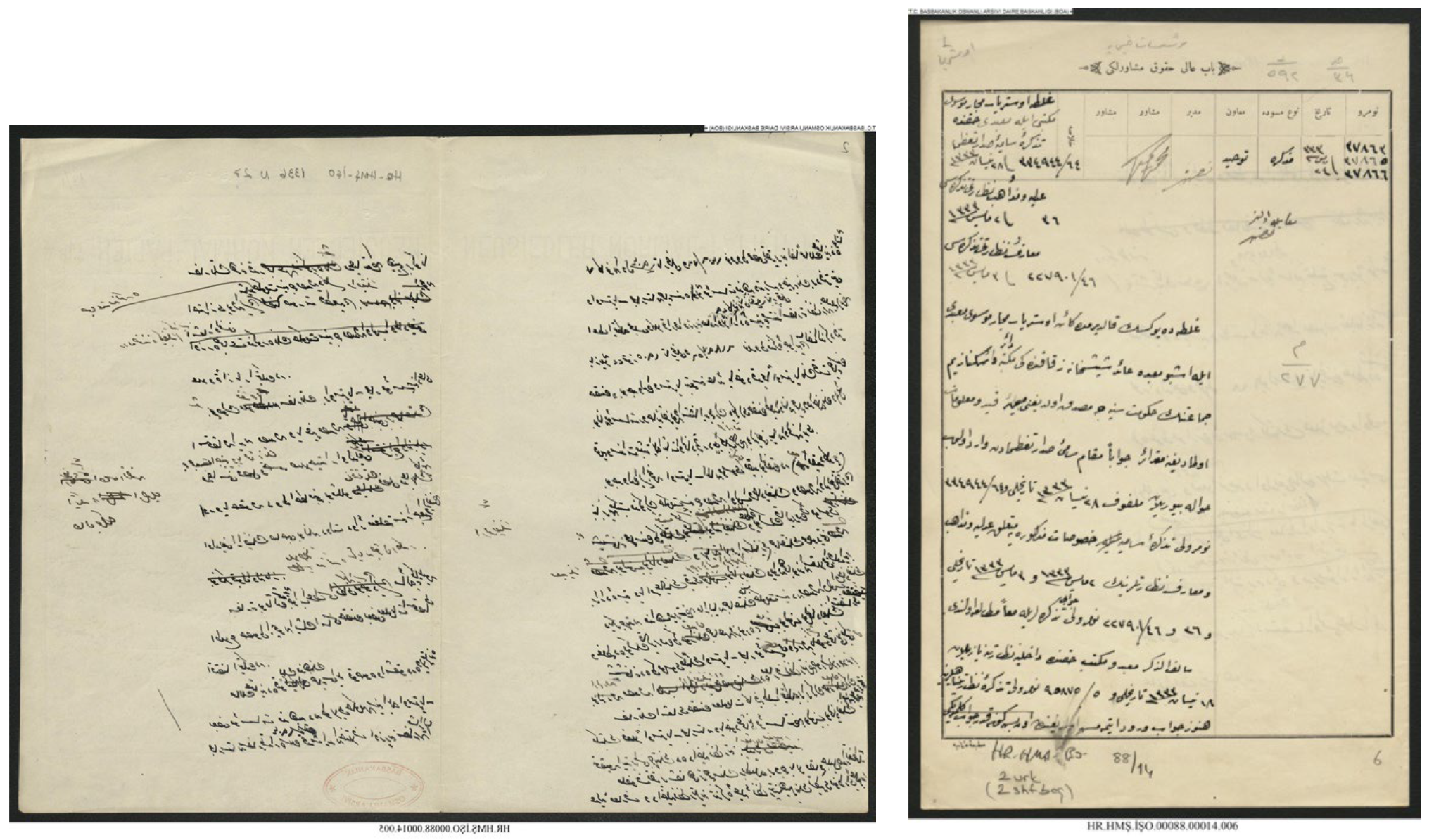

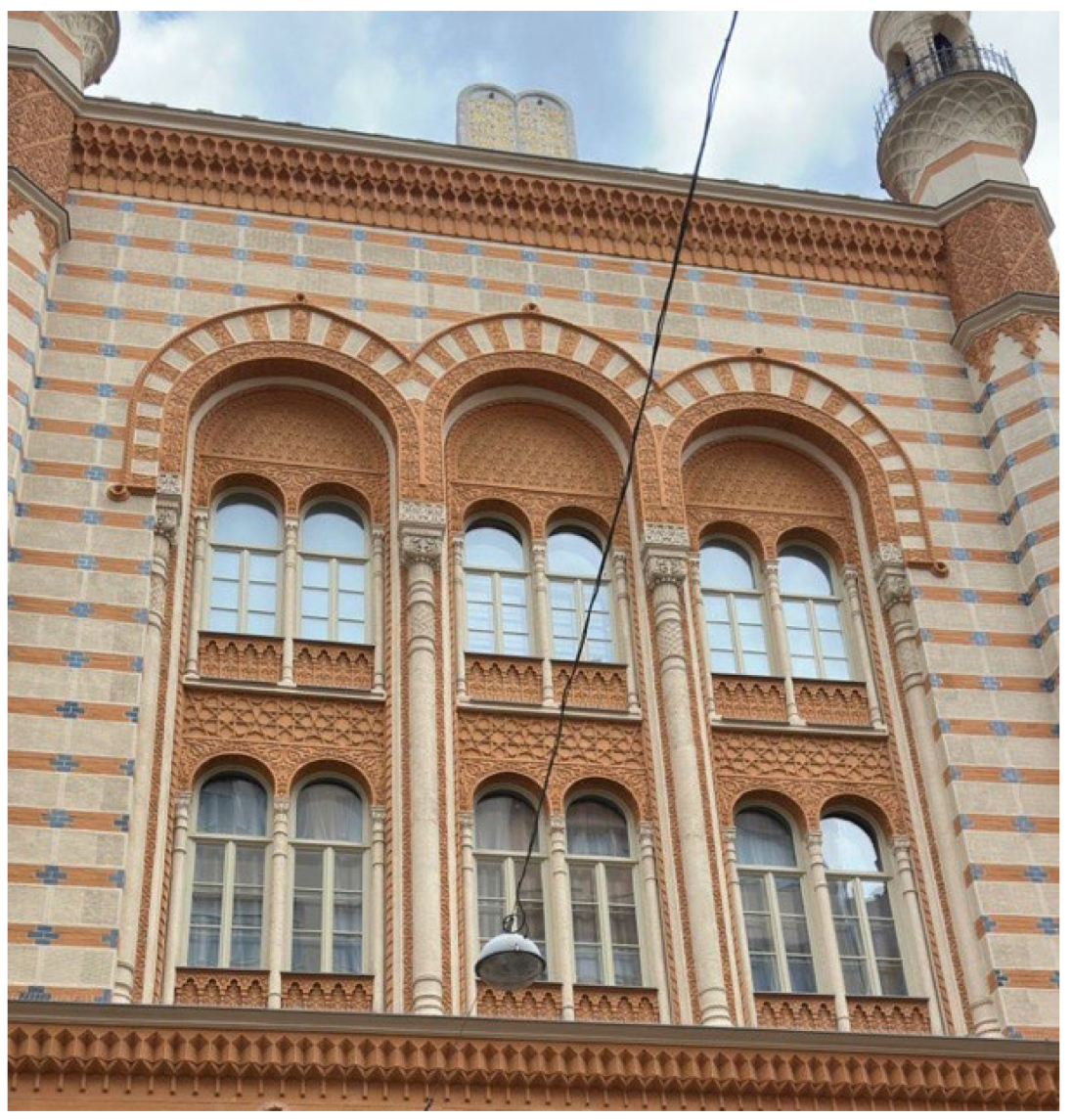

COA, BEO, 4466,334944.COA, HR.HMS.ISO., 88–13.COA, HR.HMS.ISO., 88–14COA, HR.SYS., 1776, 1.COA, ŞD., 2338, 11.COA, Y. PRK.AZN., 1–8.Figure 1. see (von Orelli-Messerli 2018).Figure 2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leipzig_Synagogue#/media/File:Große_Gemeindesynagoge_Leipzig.jpg (accessed on 16 June 2025).Figure 3. https://www.mahj.org/en/decouvrir-collections-betsalel/temple-israelite-rue-notre-dame-de-nazareth-coupe-tranversale-25649 (accessed on 16 June 2025), https://www.mahj.org/en/decouvrir-collections-betsalel/temple-israelite-rue-notre-dame-de-nazareth-paris-facade-25642?page=0 (accessed on 16 June 2025).Figure 4. The image was provided by FLLL. This content is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License Version 1.2. The image was retrieved from [Wikimedia] (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f9/Syna_Nazareth.JPG (accessed on 16 June 2025)). No modifications have been made to the image.Figure 5. The image was provided by Toksave. This content is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License Version 1.2. The image was retrieved from [Wikimedia] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Synagogue_of_Florence#/media/File:Synagogue_Florence_Italy.JPG (accessed on 16 June 2025)). No modifications have been made to the image.Figure 6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semper_Synagogue#/media/File:Louis_Thümling_nach_Hermann_Krone_-_Alte_Synagoge_in_Dresden_(1850-70)_cropped.png (accessed on 16 June 2025).Figure 7. https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Leopoldstädter_Tempel#/media/Datei:WStLA_M_Abt_236_A16_EZ_2141_Adaptierung_1905_Fassade_Oskar_Marmorek.jpg (accessed on 16 June 2025).Figure 10. https://pastvu.com/p/1386097 (accessed on 16 June 2025).Figure 11. COA, BEO, 4466,334944; COA, HR.SYS., 1776, 1; COA, HR.HMS.ISO., 88–13; COA, HR.HMS.ISO., 88–14.Figure 13. https://www.salom.com.tr/arsiv/haber/99835/1900-tarihli-askenaz-sinagogu-cemaati-tahvili (accessed on 18 June 2025); From the Personal Archive of Nisya Isman Allovi.Figure 14. From the personal archive of Nisya Isman Allovi.Figure 15. From the personal archive of Nisya Isman Allovi.Figure 16. COA, DH.MKT, 2415, 125.Figure 17. COA, BEO, 4466,334944; COA, HR.SYS., 1776, 1.Figure 18. https://www.haberturk.com/balat-tan-galata-ya-yahudi-mirasi-2613410-amp (accessed on 8 September 2025); From the personal archive of Nisya Isman Allovi.Figure 19. https://kulturenvanteri.com/yer/yildiz-sarayi-hamidiye-cesmesi/#17.1/41.049652/29.011455 (accessed on 8 September 2025); (Urfalıoğlu 2015).Figure 21. (Saner 1998).Figure 23. The image was provided by Velvet. This content is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. The image was retrieved from [Wikimedia] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lille_Synagogue#/media/File:Lille_synagogue_ter.jpg (accessed on 18 August 2025)). No modifications have been made to the image.Figure 24. The image was provided by David Dixon. This content is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. The image was retrieved from [Wikimedia] (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchester_Jewish_Museum#/media/File:Manchester_Jewish_Museum_(geograph_4749574).jpg (accessed on 18 August 2025)). No modifications have been made to the image.Figure 28. (https://www.google.com/maps/place/İstanbul+Aşkenaz+Sinagogu/ (accessed on 16 June 2025)); https://kenancruzcilli.wordpress.com/2019/11/11/shining-new-light-on-istanbuls-ashkenazi-heritage/ (accessed on 18 August 2025).Published References

- Akın Ertek, Gülferi. 2025. Rundbogenstil ve Doğu Avrupa’ya Yansımaları. Ph.D. thesis, Ordu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Ordu, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Arpacı, Kubilay. 2020. İstanbul Mimarisinde Sanatkâr İmzaları (1800–1923). Master’s thesis, Marmara Üniversitesi Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü, İstanbul, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Aslanapa, Oktay. 2004. Osmanlı Devri Mimarisi. İstanbul: İnkılap Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, Mehmet. 2002. İstanbul’un Fethinden Önce ve Sonra İstanbul’daki Yahudi Cemaatleri. Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 14: 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Batur, Afife. 2001. “Milli” Olarak Adlandırılan Mimari Eğilimler İstanbul ve Ankara Örnekleri Üzerine Gözlem ve Düşünceler. Mimarlık Dergisi 298: 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, Menahem. 2004. Al-Andalus: The So-Called “Golden Age” of Spanish Jewry- a Critical View. In The Jews of Medieval Europe: Sefarad and Ashkenaz. Brepols: Turnhout, pp. 123–37. [Google Scholar]

- Biçen, Gürkan, and Hüseyin Erkan Bedirhanoğlu. 2022. The Mass Migration of Jews from Palestine to Andalus and the Life of the Jews in Andalus. İçtimaiyat Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi Göç ve Mültecilik Özel Sayısı, 107–21. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/2244918 (accessed on 18 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, Gülnihal. 1993. Yahudi İlişkilerine Genel Bir Bakış. Belleten 57: 539–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullen, J. B. 2003. Byzantium Rediscovered. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, J. B. 2004. The Romanesque Revival in Britain: 1800–1840: William Gunn, William Whewell and Edmund Sharpe. Architectural History 47: 139–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Jean-Paul, and Mark Koyama. 2016. Jewish emancipation and schism: Economic development and religions change. Journal of Comparative Economics 44: 562–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyhan, Muhammed. 2020. Osmanlı Devleti’nde Ruhsatsız Olarak İnşa Edileb Kilise, Manastır, Havra ve Mektepler. Turkish Studies 15: 157–76. [Google Scholar]

- Coenen Snyder, Saskia. 2013. Building a Public Judaism: Synagogues and Jewish Identity in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark R. 2008. The “Golden Age” of Jewish-Muslim Relations: Myth and Reality. In Under Crescent and Chross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, Kathleen. 2003. The Romanesque Revival, Religion, Politics and Transnational Exchange. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, Zeynep. 2005. Şark’ın Sergilenişi. Translated by Nurettin Elhüseyni. İstanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Çolak, Filiz. 2020. Osmanlı Devleti’nin Dış Ticaretinde Avusturya-Macaristan’ın Yeri ve Önemi (1908–1918). Akademik Tarih ve Düşünce Dergisi 7: 1611–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dénes, Komárik. 1984. A “Félköríves” Romantıka Építészete Magyarországon. In Építés- Építészettudomány. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, volume XVI, pp. 139–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dow, Helen J. 1957. The Rose-Window. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 20: 248–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elibol, Numan. 2003. XVIII. Yüzyılda Osmanlı-Avusturya Ticareti. Ph.D. thesis, Marmara Üniversitesi, İstanbul, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Elibol, Numan. 2004. XVIII. Yüzyılda Avusturya Topraklarında Faaliyet Gösteren Osmanlı Tüccarları. Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi 15: 59–112. [Google Scholar]

- Erdim, Ümit. 2019. İstanbul’daki Musevi Okulları ve Koruma Sorunları, Ortaköy Etz Ahayim Sinagogu Musevi Mektebi Örneği. Master’s thesis, İstanbul Kültür Üniversitesi Lisansüstü Eğitim Enstitüsü, İstanbul, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Evcim, Seçkin. 2010. Bilecik-Osmaneli’de Bir Osmanlı Dönemi Rum Kilisesi: Hagios Georgios. Paper presented at the XIII. Ortaçağ ve Türk Dönemi Kazıları ve Sanat Tarihi Araştırmaları Sempozyum Bildirileri, Denizli, Turkey, 14–16 October 2009; pp. 259–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fayda, Mustafa. 2013. Zimmî. TDV İslam Ansiklopedisi 44: 428–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Robert, and Philip Spencer. 2017. Antisemitism and the Left on the Return of the Jewish Question. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Förster, Ludwig. 1859. Das israelitische Bethaus. Allgemeine Bauzeitung 24: 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Moise. 1897. Essai sur L‘Histoire des Israélites de L’empire Ottoman Depuis Les Origines Jusqu’a nos Jours. Paris: Librairie a Durlacher. [Google Scholar]

- Frayman, Erdal. 2000. Osmanlı’da Aşkenazlar. In Yüksekkaldırım’da Yüz Yıllık Bir Sinagog Aşkenazlar. Edited by Erdal Frayman, Moşe Grosman and Robert Schild. İstanbul: Galata Aşkenaz Kültür Derneği, pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Frübis, Hildegard. 2018. Die Neue Synagoge in Berlin (1866) und die Alhambra. Die Adaption maurischer Stilelemente und die Re-Orientalisierungdes europäischen Judentums. In The Power of Symbols: The Alhambra in a Global Perspective. Edited by Francine Giese-Vögeli and Ariane Varela Braga. Bern: Peter Lang AG, pp. 153–63. [Google Scholar]

- Galante, Avram. 1986. Histoire des Juifs de Turquie 2. Istanbul: Editions Isis. [Google Scholar]

- Genée, Pierre. 1987. Wiener Synagogen, 1825–1938. Wien: Löcker Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Genée, Pierre. 1992. Synagogen in Österreich. Wien: Löcker Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Germaner, Semra, and Zeynep İnankur. 1989. Orientalism and Turkey. İstanbul: Turkish Cultural Service Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Gharipour, Mohammad. 2017. Architecture of Synagogues in the Islamic World: History and the Dilemma of Identity. In Synagogues in the Islamic World Architecture, Design and Identity. Edited by Mohammad Gharipour. Edinburg: Edinburg University Press, pp. 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Güleryüz, Naim A. 2018. Trakya ve Anadolu’da Yahudi Yerleşim Yerleri I İstanbul. İstanbul: Gözlem Yayınevi, pp. 182–83. [Google Scholar]

- Güçhan, Ayşegül. 2015. Interwoven Ottoman and British Cultural Policies in the case of the Crimea Memorial Church. International Journal of Cultural Policy 21: 577–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer-Schenk, Harold. 1981. Synagogen in Deutschland: Geschichte einer Baugattung im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert (1780–1933). Hamburg: Hans Christians Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, Leicester B. 1918. The Origin of the Horseshoe Arch in Northern Spain. American Journal of Archaeology 22: 378–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübsch, Heinrich. 1828. In Welchem Style Sollen Wir Bauen? Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/huebsch1828 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- İlhan, Sinan. 2009. Fetihten Murâbıtlar Dönemine Kadar (711–1091) Endülüs Sosyal Hayatında Yahudiler. İSTEM 7/14: 239–59. [Google Scholar]

- İnalcık, Halil. 1964. Sened-, İttifak ve Gülhane Hatt-ı Hümayunu. Belleten 28: 603–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrassé, Dominique. 2001. Synagogues: Architecture and Jewish Identity. Paris: Vilo Intl. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrassé, Dominique. 2004. La synagogue de la rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth, lieu de construction d ‘une culture juive parisienne et d ‘un regard sur les Juifs. Romantisme 125: 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadish, Sharman. 2003. Manchester Synagogues and Their Architects 1740–1940. Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society 47: 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmar, Ivan Davidson. 2000. The Origins of the “Spanish Synagogue” of Prague. Judaica Bohemiae XXXV: 158–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmar, Ivan Davidson. 2001. Moorish Style: Orientalism, the Jews and Synagogue Architecture. Jewish Social Studies 7: 68–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmar, Ivan Davidson. 2013. The Israelite Temple of Florence: Anthropological Perspectives. In Religious Architecture Anthropological Perspectives. Edited by Oskar Verkaaik. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 171–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kırıcı Tekeli, Ezgi. 2020. İstanbul Sinagogları: Yahudi Kültür Mirası. In Anadolu’da İnanç Turizmi Fenomenler, Efsaneler, Kişiler ve Mekanlar. Edited by Özlem Güzel. Ankara: Nobel Yayıncılık, pp. 742–61. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Rudolf. 2006. Oriental-Style Synagogues in Austria-Hungary: Philosophy and Historical Significance. Ars Judaica 2: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Rudolf. 2010. Nineteenth-century synagogue typology in historic Hungary. In Jewish Architecture in Europe. Edited by Aliza Cohen-Mushlin and Harmen H. Thies. Petersberg: M. Imhof, pp. 109–22. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Rudolf. 2014. How to Create a Building Typology? Typological matrix for mapping 19th century synagogues. Journal of Faculty of Civil Engineering 24: 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Rudolf. 2017. Synagogues in Hungary, 1782–1918 Genealogy, Typology and Architectural Significance. Budapest: Terc Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Knežević, Snješka. 1999. Zagrebačka sinagogaç. Radovi Instituta za Povijest Umjetnosti 23: 121–48. [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncu, Aşkın. 2014. Osmanlı Devleti’nde Kilise ve Havra Politikasına Yeni Bir Bakış: Çanakkale Örneği. Çanakkale Araştırmaları Türk Yıllığı 12: 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravtsov, Sergey R. 2010. Jewish Identities in Synagogue Architecture of Galicia and Bukovina. Ars Judaica: The Bar-Ilan Journal of Jewish Art 6: 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky, Carol Herselle. 1996. Synagogues of Europe: Architecture, History, Meaning. New York: Dover Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kuban, Doğan. 2021. Osmanlı Mimarisi. İstanbul: YEM Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Küçük, Mehmet Alparslan. 2013. İnanç Turizmi Açısından Türkiye’de Dini Mekanlar (Yahudilik-Hristiyanlık Örneği). Ankara: Berikan Yayınevi. [Google Scholar]

- Künzl, Hannelore. 1984. Islamische Stilelemente im Synagogenbau des 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, Basilio Pavón. n.d.a. Capiteles, Basas, y Cimacios en la Arquitectua Arabe Occidental. Primera Parte. Available online: http://www.basiliopavonmaldonado.es/Documentos/Capiteles.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Maldonado, Basilio Pavón. n.d.b. Capiteles, Basas, y Cimacios en la Arquitectua Arabe Occidental. Segunda Parte. Available online: http://www.basiliopavonmaldonado.es/Documentos/Capiteles2.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Meek, Harold Alan. 1995. The Synagogue. London: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Garrido, Daniel. 2017. The Prevalence of Islamic Art amongst Jews of Christian Iberia: Two Fourteenth-century Castilian Synagogues in Andalusian Attire. In Synagogues in the Islamic World Architecture, Design and Identity. Edited by Mohammad Gharipour. Edinburg: Edinburg University Press, pp. 127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Musto, Jeanne-Marie. 2007. Byzantium in Bavaria: Art, Architecture and History Between Empiricism and Invention in the Post-Nepoleonic Era. Ph.D. thesis, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg, David. 2024. Convivencia vs. Race: On the Dangers of Extracting Morality from History. In Religious and Intellectual Diversity in the Islamicate Wold and Beyond Volume II. Edited by Omer Michaelis and Sabine Schmidtke. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1255–77. [Google Scholar]

- Öner, Çiğdem. 2022. Anadolu’da Yahudi İzleri ve Sinagog Yapıları. In Genç Akademisyenlerin Kaleminden Sosyal Bilimler. Edited by Ziya Polat, Ayşe Çekiç, Sabri Mengirkaon and Aysel Fedai. Ankara: İlahiyat Yayınları, pp. 496–99. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan Altınöz, Meltem. 2014. 19. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Mimarisi’ndeki Oryantalizmin Endülüs Kaynağı ve Sirkeci Garı’nın Değerlendirilmesi. Turkish Studies 9: 837–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan Altınöz, Meltem. 2015. The Tofre Begadim Synagogue and the Non-Muslim Policy of the Late Ottoman Empire. In Sacred Precincts The Religious Architecture of Non-Muslim Communities across the Islamic World. Edited by Mohammad Gharipour. Leiden: Brill, pp. 334–52. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan Altınöz, Meltem. 2017. The Ottoman Jews of Nineteenth-century Istanbul and the Socio-cultural Foundations of the Yüksek Kaldırım Ashkenazi Synagogue. In Synagogues in the Islamic World Architecture, Design and Identity. Edited by Mohammad Gharipour. Edinburg: Edinburg University Press, pp. 145–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut, Rudy. 2021. La synagogue de Lille et les deux guerres mondiales. Tsafon 81: 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saner, Turgut. 1998. 19. Yüzyıl İstanbul Mimarlığında “Oryantalizm”. İstanbul: Pera Turizm ve Ticaret A.Ş. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Mrineio. 1999. El capitel almohade: Importancia y consecuencias. BIBLID 48: 177–229. [Google Scholar]

- Schild, Robert. 2017. Zwischen Österreichischen Tempel und Schneiderschul. In Österreich in Istanbul II. Edited by Elman Samsinger. Wien: LIT Verlag, pp. 99–131. [Google Scholar]

- Schild, Robert. n.d. der “Österreichische Tempel” in Istanbul. Available online: http://davidkultur.at/artikel/der-oesterreichische-tempel-in-istanbul (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Sezer, Sennur, and Adnan Özyalçıner. 2014. Öyküleriyle İstanbul Anıtları-II Saray’dan Liman’a. İstanbul: Evrensel Basım Yayım. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Stanford J. Shaw. 1991. The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez, Zeki. 2006. Türk-İtalyan Siyaset ve Sanat İlişkileri. İstanbul: Bağlam Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Şarlak, Evangelia. 2010. İstanbul’un 100 Kilisesi. İstanbul’un Yüzleri Serisi 18; İstanbul: İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür A.Ş. Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Şarlak, Evangelia. 2011. Yüzyılda İstanbul’un Fiziksel Çehresinin Değişmesine Rol Oynayan Kubbeli Rum Ortodoks Kiliseleri. In Batılılaşan İstanbul’un Rum Mimarları. Edited by Hasan Kuruyazıcı and Evangelia Şarlak. İstanbul: Zoğrafyon Lisesi Mezunlar Derneği, pp. 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, Önder. 2022. II. Abdülhamid Han Dönemi Mobilyalarının Tasarım, Konstrüksiyon Özelliklerinin ve Günümüzde Üretilebilirliğinin Araştırılması. Ph.D. thesis, Gazi Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Ankara, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, Önder. 2023. Marangoz Padişah II. Abdülhamid ve Ürettiği Eserler. Eskişehir: Dorlion Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Türkoğlu, İnci. 2001. Antikçağ’dan Günümüze Türkiye’de Sinagog Mimarisi. Master’s thesis, Ege Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, İzmir, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Türkoğlu, İnci. 2004. Haliç’in İki Yakasındaki Sinagoglar Üzerine Gözlemler. In Dünü ve Bugünü ile Haliç Sempozyumu (22–23 Mayıs 2003). İstanbul: Kadir Has Üniversitesi Yayınları, pp. 479–98. [Google Scholar]

- Urfalıoğlu, Nur. 2015. İstanbul’un Çeşme ve Sebilleri. In Antik Çağ’dan XXI. Yüzyıla Büyük İstanbul Tarihi Cilt 8 Mimari. Edited by Halil İbrahim Düzenli. İstanbul: İBB Kültür AŞ, pp. 468–81. [Google Scholar]

- von Orelli-Messerli, Barbara. 2018. Gottfried Semper’s Dresden Synagogue Revised: An Echo of the Alhambra? In The Power of Symbols the Alhambra in a Global Perspective. Edited by Francine Giese and Ariane Varela Braga. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 157–71. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, Silke. 2004. “In welchem Style sollen wir bauen?”—Studien zu den Schriften und Bauten des Architekten Heinrich Hübsch (1795–1863). Ph.D. thesis, Universitaet Stuttgart Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultaet, Stuttgart, Deutschland. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, Carsten L. 2021. Building the Great Synagogue of Pest: Moorish Revival Architecture and the European-Ottoman Alliance in the Crimean War. Jewish Quarterly Review 111: 444–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischnitzer, Rachel. 1964. The Architecture of the European Synagogue. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Kenneth Baxter. 2009. Convivencia in Medieval Spain: A Brief History of an Idea. Religion Compass 3: 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, Ayşe Ersay. 2007. Osmanlı Sultanı II. Abdülhamid’in Sanatçı Kişiliği. Ph.D. thesis, Ankara Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Ankara, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akın Ertek, G. A 19th-Century Representation of Identity: An Evaluation of the Architectural Design of the Yüksek Kaldırım Ashkenazi Synagogue (Austrian Temple) in Istanbul. Religions 2025, 16, 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111354

Akın Ertek G. A 19th-Century Representation of Identity: An Evaluation of the Architectural Design of the Yüksek Kaldırım Ashkenazi Synagogue (Austrian Temple) in Istanbul. Religions. 2025; 16(11):1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111354

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkın Ertek, Gülferi. 2025. "A 19th-Century Representation of Identity: An Evaluation of the Architectural Design of the Yüksek Kaldırım Ashkenazi Synagogue (Austrian Temple) in Istanbul" Religions 16, no. 11: 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111354

APA StyleAkın Ertek, G. (2025). A 19th-Century Representation of Identity: An Evaluation of the Architectural Design of the Yüksek Kaldırım Ashkenazi Synagogue (Austrian Temple) in Istanbul. Religions, 16(11), 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111354