Influence of Ecological Factors and Internal Resources on Adolescent Suicidal Ideation: An Empirical Study in Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Family Functionality and Suicidal Ideation

1.2. School Context and Suicidal Ideation: The Protective Role of School Satisfaction

1.3. Religiosity and Suicidal Ideation

1.4. This Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Suicidal Ideation

2.2.2. Family Functionality

2.2.3. Psychological Well-Being

2.2.4. School Satisfaction

2.2.5. Religiosity

2.2.6. Spirituality

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

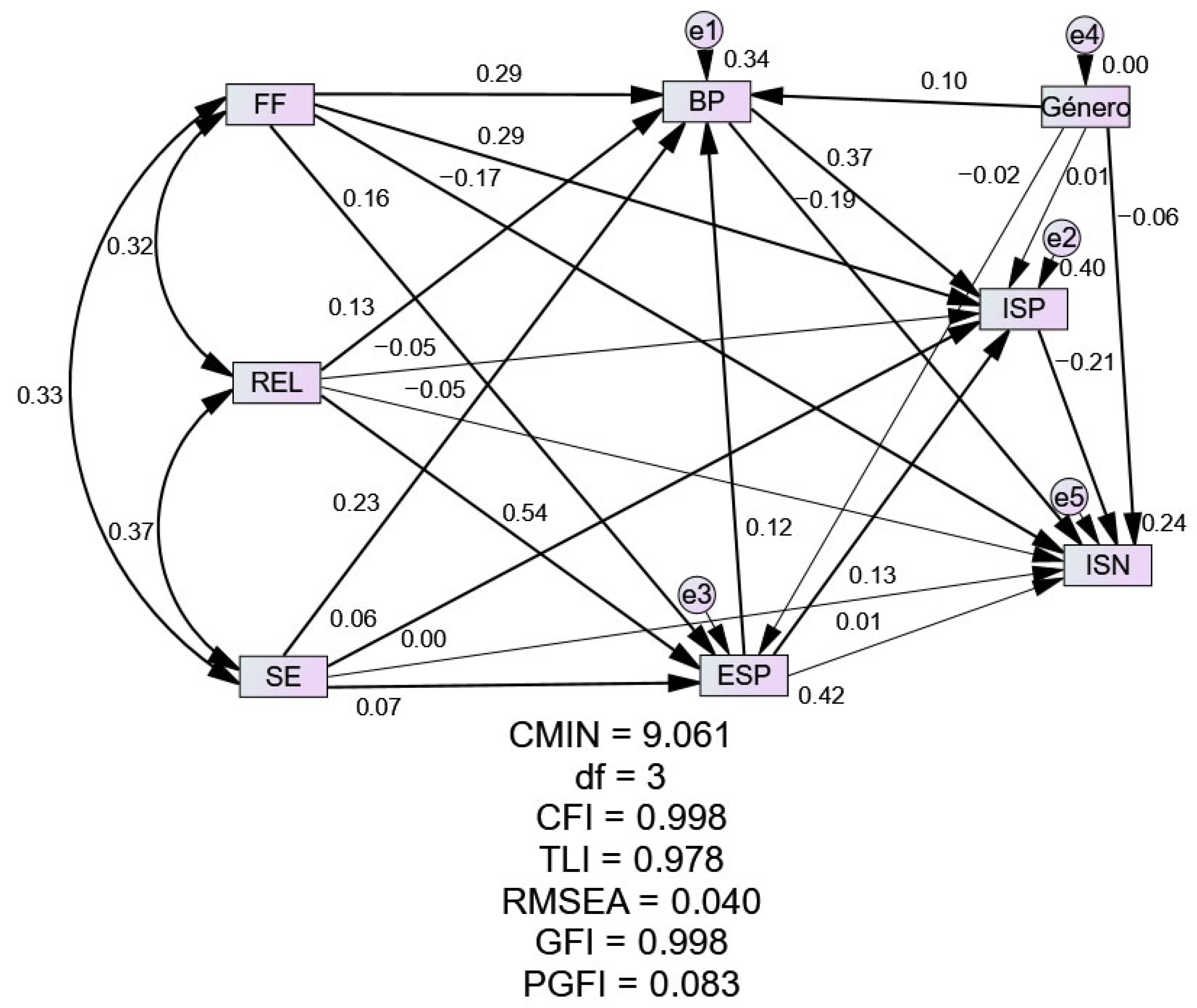

3.1. Structural Model of Relationships Between Ecological Factors, Psychological Well-Being, Spirituality, and Adolescent Suicidal Ideation

3.2. Influences on Psychological Well-Being

3.3. Predictive Factors of Spirituality

3.4. Factors Influencing Positive Suicidal Ideation (PSI)

3.5. Factors Influencing Negative Suicidal Ideation (NSI)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abo-Zena, Mona M.., and Hoda Akef. 2024. (Invisible) foundations: How religion and spirituality influence adolescents and families within cultural contexts. In Global Perspectives on Adolescents and Their Families. Edited by Yueh-Ting Xia, María Rosario T. de Guzman, Rosario Esteinou and Chad S. Hollist. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, pp. 313–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, Jeffrey P., and Liza M. Horowitz, eds. 2022. Youth Suicide Prevention and Intervention: Best Practices and Policy Implications. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Flórez, Diana Carolina, José Jaime Cataño-Castrillón, Sandra Constanza Cañón, Daniel Felipe Marín-Sánchez, Julieth Tatiana Rodríguez-Pabón, Luz Ángela Rosero-Pantoja, Laura Patricia Valenzuela-Díaz, and Jennifer Vélez-Restrepo. 2015. Riesgo suicida y factores asociados en adolescentes de tres colegios de la ciudad de Manizales (Colombia), 2013. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina 63: 419–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Khalid, Amanda Beatson, Megan Campbell, Rizwan Hashmi, Bryan William Keating, Ruth Mulcahy, Anja Riedel, and Shuang Wang. 2023. The impact of gender and age on bullying role, self-harm and suicide: Evidence from a cohort study of Australian children. PLoS ONE 18: e0278446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamón, María José. 2017. Prevención del riesgo suicida en adolescentes: Una propuesta de abordaje desde la Psicología Positiva. In Estudios Actuales en Psicología: Perspectivas en Clínica y Salud. Edited by Maria José Bahamón, Yolanda Alarcón, Luis Albor and Yenny Martínez. Barranquilla: Universidad Simón Bolívar, pp. 54–69. Available online: https://bonga.unisimon.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/340dfd4c-280b-40ae-bc8d-d33c7115828f/content (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Bahamón, María José, and Yolanda Alarcón-Vásquez. 2018. Diseño y validación de una escala para evaluar el riesgo suicida (ERS) en adolescentes colombianos. Universitas Psychologica 17: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamón, María José, Yolanda Alarcón-Vásquez, Ana María Trejos-Herrera, Laura Reyes, Juan Uribe, and Carlos García. 2018. Prácticas parentales como predictoras de la ideación suicida en adolescentes colombianos. Psicogente 21: 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamón, María José, Yolanda Alarcón-Vásquez, Ana María Trejos-Herrera, Sandro Vinaccia, Carlos Alberto Cabezas, and Juan Sepúlveda-Aravena. 2019. Efectos del programa CIPRES sobre el riesgo suicida en adolescentes. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica 24: 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, María, María Mercedes Gutiérrez, María Luisa Sánchez, María Natalia Herrera, Sandra Ángela Gómez, and Rosa Isabel Bouquet. 2010. El suicidio en la juventud: Una mirada desde la teoría de las representaciones sociales. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 39: 522–43. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-74502010000300007&lng=en&tlng=es (accessed on 25 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117: 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavente, María, Felipe Cova, Claudia Pérez-Salas, Jorge Varela, Juan Alfaro, and José Chuecas. 2018. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala breve de bienestar subjetivo en la escuela para adolescentes (BASWBSS) en una muestra de adolescentes chilenos. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación 3: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, Clare L., Yvonne J. Kelly, and Amanda Sacker. 2018. Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10–15 year-olds in the UK. BMC Public Health 18: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, Jean-Jacques, Renée Labelle, Claude Berthiaume, Caroline Royer, Marie St-Georges, Dominique Ricard, Pierre Abadie, Philippe Gérardin, David Cohen, and Jean-Marc Guilé. 2015. Protective factors against depression and suicidal behaviour in adolescence. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 60 Suppl. 1: S5–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1987. La Ecología del Desarrollo Humano. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica, S. A. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1992. Teoría de los Sistemas Ecológicos. London: Editores Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Campo-Arias, Adalberto, and Carlos Caballero-Domínguez. 2020. Análisis factorial confirmatorio del cuestionario de APGAR familiar. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 50: 234–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañón, Sandra Constanza, Carlos Julián Castaño, Luis Alberto Mosquera, Ana Lucía Nieto, Diana Marcela Orozco, and Laura Wendy Giraldo. 2018. Propuesta de intervención educativa para la prevención de la conducta suicida en adolescentes en la ciudad de Manizales (Colombia). Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología 14: 27–40. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=679/67957684003. [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Halty, Marcelo, and Juan Manuel Villegas-Robertson. 2019. El capital psicológico predice el bienestar y desempeño en estudiantes secundarios chilenos. Revista Interamericana de Psicología/Interamerican Journal of Psychology 52: 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, Gabriela Milagros. 2025. Relación Entre Religiosidad, Espiritualidad y Bienestar Psicológico en los Jóvenes de la “Conexión Bíblica Universitaria Internacional”. Bachelor’s thesis, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, San Martín de Porres, Peru. Institutional Repository UPCH. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12866/16779 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Chang, Chia-Jung, Christine M. Ohannessian, Elizabeth S. Krauthamer Ewing, Roger Kobak, Guy S. Diamond, and Joanna Herres. 2020. Attachment and parent-adolescent discrepancies in reports of family functioning among suicidal adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies 29: 227–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, Chia, Yi-Hsuan Chen, and Chin-Chun Yi. 2019. Loneliness in young adulthood: Its intersecting forms and its association with psychological well-being and family characteristics in Northern Taiwan. PLoS ONE 14: e0217777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, Rae A. 2018. The cultural distinctions in whether, when and how people engage in suicidal behavior. Monitor on Psychology 49: 28. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, David J., Jasmine Fardouly, and Ronald M. Rapee. 2022. The Effect of Spirituality on Mood: Mediation by Self-Esteem, Social Support, and Meaning in Life. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 228–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currier, Joseph M., Nicholas Fadoir, Thomas D. Carroll, Sarah Kuhlman, Lauren Marie, Sarah E. Taylor, Tyler Smith, Shannon L. Isaak, and Benjamin M. Sims. 2020. A cross-sectional investigation of divine struggles and suicide risk among men in early recovery from substance use disorders. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 324–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divecha, Darcia, and Marc Brackett. 2020. Rethinking School-Based Bullying Prevention Through the Lens of Social and Emotional Learning: A Bioecological Perspective. International Journal of Bullying Prevention 2: 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Oliván, Isabel, Alejandro Porras-Segovia, María Luisa Barrigón, Laura Jiménez-Muñoz, and E. Enrique Baca-García. 2021. Theoretical models of suicidal behaviour: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. The European Journal of Psychiatry 35: 181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskin, Mehmet, Senel Poyrazli, Mohammad Janghorbani, Saeed Bakhshi, María Grazia Carta, María Francesca Moro, Ulrich S. Tran, Martin Voracek, Abdelwahed Mechri, Khaled Aidoudi, and et al. 2019. The role of religion in suicidal behavior, attitudes and psychological distress among university students: A multinational study. Transcultural Psychiatry 56: 853–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euseche, Mario, and Antonio Muñoz-García. 2022. An Exploration of Spirituality, Religion, and Suicidal Ideation Among Colombian Adolescents. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying 90: 1650–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euseche, Mario, and Antonio Muñoz-García. 2024. Ideación suicida y aspectos sociodemográficos en adolescentes colombianos. Universitas Psychologica 23: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Rachel, and Keith Hawton. 2018. Psychosocial risk factors for suicidality in children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 27: 715–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, Ángela Lucía, Diana Marcela Avendaño, Zuleima Cubillos, Zoraida Duarte, and Adaberto Campo-Arias. 2006. Consistencia interna y análisis de factores de la escala APGAR para evaluar el funcionamiento familiar en estudiantes de básica secundaria. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 35: 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, Paul, Una Kahric, Emily M. Lewis, and Rebecca Theda. 2022. Family, Peer, and Neighborhood Influences on Urban Children’s Subjective Wellbeing. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 41: 427–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, Katherine, Erin Baumler, Elizabeth D. Torres, Ying Lu, Laura Wood, and Jeff R. Temple. 2022. The link between school climate and mental health among an ethnically diverse sample of middle school youth. Current Psychology 42: 18488–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Michelle L., and Allison B. Miller. 2018. Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior in Children and Adolescents: An Ecological Model of Resilience. Adolescent Research Review 3: 123–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vergara, Rodrigo, Paula Silva-Maragaño, and Yasna Castro-Aburto. 2022. Los efectos negativos de la religiosidad-espiritualidad en la salud mental: Una revisión bibliográfica. Revista Costarricense de Psicología 41: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Juan José, Diana Isabel Molina, Elena Kratc, and Gabriel C. Cardona. 2024. Salud mental positiva como factor protector en la prevención del comportamiento suicida: Afianzamiento desde grupos de apoyo. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 53: 480–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moya, Inmaculada, Karin Johansson, Sigrun Ragnarsson, Emma Bergström, and Solveig Petersen. 2019. School experiences in relation to emotional and conduct problems in adolescence: A 3-year follow up study. European Journal of Public Health 29: 436–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, Sandra R., Silvia L. Castro, and Gabriela S. Calderón. 2019. Estructura familiar, ideación suicida y desesperanza en el adolescente. Psicología Desde el Caribe 36: 228–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin-Wasson, Amanda L., Katherine L. Walker, Lauren J. Shin, and Nadine J. Kaslow. 2018. Spiritual well-being and psychological adjustment: Mediated by interpersonal needs? Journal of Religion and Health 57: 1376–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, Robin E., and Dana Alonzo. 2018. Religion and suicide: New findings. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 2478–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, Gabriela. 2007. La espiritualidad: ¿promueve la resiliencia? In Adolescencia y Resiliencia. Edited by María Munist, Nora Suárez, Daniel Krauskopf and Teresa Silber. Barcelona: Editorial Paidós, pp. 139–51. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, Caitlin R., Evan M. Kleiman, Jacob Kellerman, Olivia Pollak, Christine B. Cha, Emily C. Esposito, Amanda C. Porter, Peter A. Wyman, and Allyson E. Boatman. 2020. Annual research review: A meta-analytic review of worldwide suicide rates in adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 61: 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Carrasco, Mónica, Ferrán Casas, Sara Malo, Francisco Viñas, and Tamara Dinisman. 2017. Changes with Age in Subjective Well-Being Through the Adolescent Years: Differences by Gender. Journal of Happiness Studies 18: 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fuentes, María, and Pedro Pablo Andrade. 2016. Escala de Bienestar Psicológico para Adolescentes. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica 2: 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Juan Carlos, Laura Camila Hernández, Fernando Andrés Vega, María Mercedes Rodríguez, Edwin Gamboa, Natalia Rodríguez, Carlos Mario Castrillo, Claudia Patricia Álvarez, and Jorge Andrés Pinzón. 2022. Factores de riesgo psicosociales relacionados con ideación suicida en adolescentes escolarizados, Suba (Bogotá), 2006–2018. Revista de Salud Pública 24: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Laura. 2023. La ideación suicida en adolescentes: Estado de la cuestión [Suicidal ideation in adolescents: State of the art]. Revista Construyendo Paz Latinoamericana 8: 114–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rivera, José Antonio. 2017. Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Religiosidad Personal en una muestra de adultos en Puerto Rico. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala 20: 1386–406. [Google Scholar]

- González-Sancho, Rocío, and María Picado Cortés. 2020. Revisión sistemática de literatura sobre suicidio: Factores de riesgo y protectores en jóvenes latinoamericanos 1995–2017. Actualidades en Psicología 34: 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Tabares, Ana Sofía, Carolina Núñez, María Paula Agudelo-Osorio, and Ana María Grisales-Aguirre. 2020. Riesgo e ideación suicida y su relación con la impulsividad y la depresión en adolescentes escolares. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica 54: 147–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Sam A., Jennifer M. Nelson, Justin P. Moore, and Pamela E. King. 2019. Processes of religious and spiritual influence in adolescence: A systematic review of 30 years of research. Journal of Research on Adolescence 29: 254–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann-Stabile, Carolina, Catherine R. Glenn, and Raksha Kandlur. 2021. Theories of suicidal thoughts and behaviors: What exists and what is needed to advance youth suicide research. In Handbook of Youth Suicide Prevention. Edited by Regina Miranda and Elizabeth Jeglic. Cham: Springer, pp. 9–29. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-82465-5_2 (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Hayre, Rajan S., Carlos Sierra, Natalie Goulter, and Marlene M. Moretti. 2023. Attachment & School Connectedness: Associations with Substance Use, Depression, & Suicidality Among at-Risk Adolescents. Child Youth Care Forum 53: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Bello, Ladini Sunanda, Fernando Pio De la Hoz, and Zuleima Cogollo-Milanés. 2024. Determinantes sociales de la salud: Propuesta explicativa alternativa al enfoque biomédico de la conducta suicida. Revista de Salud Pública 26: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuita-Gutiérrez, Luis Felipe, and Jaiberth Antonio Cardona-Arias. 2016. Predictive Modeling of Quality of Life, Family Dynamics, and School Violence in Adolescent Students from Medellín, Colombia, 2014. School Mental Health 8: 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, Laura, Maria M. Alonso, Nora A. Armendáriz, Karla S. López, Marco V. Gómez, and Javier Álvarez. 2018. El efecto de la espiritualidad y el apoyo social en el bienestar psicológico y social del familiar principal de la persona dependiente del alcohol. Health & Addictions/Salud y Drogas 18: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E. Scott. 1994. Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment 6: 149–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Salud. 2024. Intento de suicidio: Informe de evento 2024. Available online: https://www.ins.gov.co/buscador-eventos/Informesdeevento/INTENTO%20DE%20SUICIDIO%20INFORME%20DE%20EVENTO%202024.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Jacob, Louis, Josep Maria Haro, and Ai Koyanagi. 2019. The association of religiosity with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the United Kingdom. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 139: 164–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiri, Delfina, Gaelle. E. Doucet, Maurizio Pompili, Gabriele Sani, Beatriz Luna, David A. Brent, and Sophia Frangou. 2020. Risk and protective factors for childhood suicidality: A US population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 7: 317–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, Thomas E. 2005. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sangwon, and Giselle B. Esquivel. 2011. Adolescent spirituality and resilience: Theory, research, and educational practices. Psychology in the Schools 48: 755–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Keith A., Alique Topalian, and Rebecca A. Vidourek. 2020. Religiosity and Adolescent Major Depressive Episodes Among 12-17-Year-Olds. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2611–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, Karen, Sharon Sweeney, Cherie Armour, Kathryn Goetzke, Marie Dunne, Mairead Davidson, and Myron Belfer. 2022. Developing hopeful minds: Can teaching hope improve well-being and protective factors in children? Child Care in Practice 28: 504–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, Etienne G., Linda L. Dahlberg, James A. Mercy, Anthony B. Zwi, and Rafael Lozano, eds. 2002. World Report on Violence and Health. Cham: World Health Organization, p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Laboratorio de Economía de la Educación (LEE) de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. 2023. Informe No. 78 Suicidio entre los jóvenes colombianos. Disponible en. Available online: https://www.javeriana.edu.co/recursosdb/5581483/8102914/INF+78-SUICIDIOS-JOVENES-COLOMBIA-LEE.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Lipschitz, Jessica M., Shirley Yen, Lauren M. Weinstock, and Anthony Spirito. 2012. Adolescent and caregiver perception of family functioning: Relation to suicide ideation and attempts. Psychiatry Research 200: 400–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Wang, Jie Mei, Lili Tian, and E. Scott Huebner. 2016. Age and gender differences in the relation between school-related social support and subjective well-being in school among students. Social Indicators Research 125: 1065–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Thomas F., and Michael D. Newcomb. 2004. Adolescent predictors of young adult and adult alcohol involvement and dysphoria in a prospective community sample of women. Prevention Science 5: 151–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño-Muriel, Valeria, and Sandra Constanza Cañón-Buitrago. 2020. Factores de riesgo para conducta suicida en adolescentes escolarizados: Revisión de tema. Archivos de Medicina 20: 472–80. [Google Scholar]

- López-Vega, July Marcela, Marvin Katherine Amaya-Gil, Yenny Salamanca-Camargo, and José Daniel Caro-Castillo. 2020. Relación entre psicopatologías e ideación suicida en adolescentes escolarizados de Colombia. Psicogente 23: 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, Douglas A. 2000. Spirituality: Description, measurement, and relation to the five factor model of personality. Journal of Personality 68: 153–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, Annette, and Annmarie Cano. 2014. Introduction to the special section on religion and spirituality in family life: Pathways between relational spirituality, family relationships and personal well-being. Journal of Family Psychology 28: 735–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, Jussara, and Rosangela Werlang. 2014. Self-destruction and self-exclusion: The suicide in the rural areas of Rio Grande do Sul—Brazil. Pensamiento Americano 7: 123–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mínguez, Almudena. 2020. Children’s Relationships and Happiness: The Role of Family, Friends and the School in Four European Countries. Journal of Happiness Studies 21: 1859–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, Antonio. 2013. Is religion independent of students’ approaches to learning? Studia Psychologica 55: 215–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, Antonio., and María Dolores Villena-Martínez. 2021. Influences of Learning Approaches, Student Engagement, and Satisfaction with Learning on Measures of Sustainable Behavior in a Social Sciences Student Sample. Sustainability 13: 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Ariza, Andryn, Lizeth Reyes-Ruiz, Milgen Sánchez-Villegas, Farid Alejandro Carmona, Johan Acosta-López, and Edwin Moya-De Las Salas. 2020. Ideación suicida y funcionalidad familiar en adolescentes del caribe colombiano. Archivos Venezolanos de Farmacología y Terapéutica 39: 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, Eva, Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, and Bruno D. Zumbo. 2011. Life satisfaction in early adolescence: Personal, neighborhood, school, family, and peer influences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 40: 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, Doug, and David Lukoff. 2018. Mental health, religion, and spirituality. In Why Religion and Spirituality Matter for Public Health: Evidence, Implications, and Resources. Edited by Doug Oman. Cham: Springer, pp. 225–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriol, Xavier, Rafael Miranda, Alberto Amutio, Hedy C. Acosta, Michelle C. Mendoza, and Javier Torres-Vallejos. 2017. Violent relationships at the social-ecological level: A multi-mediation model to predict adolescent victimization by peers, bullying and depression in early and late adolescence. PLoS ONE 12: e0174139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, Augustine, Peter Gutiérrez, Beverly Kopper, Francisco Barrios, and Christine Chiros. 1998. The positive and negative suicide ideation inventory: Development and validation. Psychological Reports 82: 783–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. 2021. Suicide in the Americas: Regional Report 2021. PAHO. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/suicide-americas-regional-report-2021 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Pappas, Stephanie. 2023. More than 20% of teens have seriously considered suicide. Monitor on Psychology 54: 54. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Julie J. Exline, and James W. Jones, eds. 2013. APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol. 1): Context, Theory, and Research. Washington: American Psychological Association, Vol. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peker, Adem, and Serkan Cengiz. 2023. Academic Monitoring and Support from Teachers and School Satisfaction: The Sequential Mediation Effect of Hope and Academic Grit. Child Indicators Research 16: 1553–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plöderl, Martin, Kunrath Sabine, and Fartacek Clemens. 2020. God bless you? The association of religion and spirituality with reduction of suicide ideation and length of hospital stay among psychiatric patients at risk for suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 50: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, Kristopher, and Andrew Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel, Villafaña José, and Samuel Jurado. 2022. Definición de suicidio y de los pensamientos y conductas relacionadas con el mismo: Una revisión. Psicología y Salud 32: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, Cristobal, Juan Pablo Zapata, Mónica Gómez, and Juanita Pérez. 2025. Ideación Suicida Persistente en un Programa de Intervención y Prevención de Conducta Suicida en Medellín, Colombia [Persistent Suicidal Ideation in an Intervention and Prevention Program for Suicidal Behavior in Medellín, Colombia] (Undergraduate thesis). Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.udea.edu.co/bitstreams/4676c543-1451-45aa-af21-9f283b1ca826/download (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Richardson, Rebecca, Tanya Connell, Mandie Foster, Julie Blamires, Smita Keshoor, Chris Moir, and Irene Suilan Zeng. 2024. Risk and protective factors of self-harm and suicidality in adolescents: An umbrella review with meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 53: 1301–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, Mariano, and Karen Watkins-Fassler. 2022. Religious Practice and Life Satisfaction: A Domains-of-Life Approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 23: 2349–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D. 1989. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 1069–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Daniela, Guillermo Alonso Castaño, Gloria Maria Sierra, Nadia Moratto, Carolina Salas, Carolina Buitrago, and Yolanda Torres. 2019. Salud mental de adolescentes y jóvenes víctimas de desplazamiento forzado en Colombia. CES Psicología 12: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seely, Hayley D., Jeremy Gaskins, Patrick Pössel, and Martin Hautzinger. 2023. Comprehensive Prevention: An Evaluation of Peripheral Outcomes of a School-based Prevention Program. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology 51: 921–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembler, Camilo. 2023. Vida individual y sufrimiento social. La pregunta sociológica por el suicidio. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 29: 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Swati, and Kamlesh Singh. 2019. Religion and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Positive Virtues. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 119–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, Gabrielle, Thu Andersen, Larisa T. McLoughlin, Denise Beaudequin, Marcella Parker, Amanda Clacy, Jim Lagopoulos, and Daniel F. Hermens. 2021. Suicidality in 12-Year-Olds: The Interaction Between Social Connectedness and Mental Health. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 52: 619–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkin, Hugo A. 2016. Espiritualidad, Religiosidad y Bienestar Subjetivo y Psicológico en el Marco del Modelo y la Teoría de los Cinco Factores de la Personalidad. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina. SEDICI Repositorio Institucional UNLP. Available online: https://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/52984 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Smilkstein, Gabriel. 1978. The family APGAR: A proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. The Journal of Family Practice 6: 1231–39. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Nicholas David, Shannon Suldo, Brittany Hearon, and John Ferron. 2020. An application of the dual-factor model of mental health in elementary school children: Examining academic engagement and social outcomes. Journal of Positive School Psychology 4: 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sue, Wing, and David Sue. 2012. Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice, 6th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Szcześniak, Małgorzata, and Celina Timoszyk-Tomczak. 2020. Religious Struggle and Life Satisfaction Among Adult Christians: Self-esteem as a Mediator. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2833–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tae, Hyejin, and Jeong-Ho Chae. 2021. Factors Related to Suicide Attempts: The Roles of Childhood Abuse and Spirituality. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 565358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscanelli, Cecilia, Elizabeth Shino, Sarah Robinson, and Amber Gayle Thalmayer. 2022. Religiousness worldwide: Translation of the Duke University Religion Index into 20 languages and validation across 27 nations. Measurement Instruments for the Social Sciences 4: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, Alba, and Carmen Míguez. 2021. La prevención de la conducta suicida en adolescentes en el ámbito escolar: Una revisión sistemática. Terapia Psicológica 39: 145–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, Cornelia Leontine, Marcel Franciscus van der Wal, Pim Cuijpers, and Mai Jeanette Chinapaw. 2021. Sociodemographic Differences in Time Trends of Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents Living in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Crisis 42: 369–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, Frances. 1991. Spiritual issues in psychotherapy. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 23: 105–19. [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos-Galvis, Fredy Hernán. 2010. Validez y fiabilidad del Inventario de Ideación Suicida Positiva y Negativa-PANSI, en estudiantes colombianos. Universitas Psychologica 9: 509–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Froma. 2013. Religion and spirituality: A family systems perspective in clinical practice. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol. 2): An Applied Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Annette Mahoney and Edward P. Shafranske. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waraan, Luxsiya, Johan Siqveland, Ketil Hanssen-Bauer, Nikolai Czjakowski, Brynhildur Axelsdóttir, Lars Mehlum, and Marianne Aalberg. 2023. Family therapy for adolescents with depression and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 28: 831–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, Danuta, Vladimir Carli, Miriam Iosue, Afzal Javed, and Helen Herrman. 2021. Suicide prevention in childhood and adolescence: A narrative review of current knowledge on risk and protective factors and effectiveness of interventions. Asia Pacific Psychiatry 13: e12452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingate, LaRicka, Andrea Burns, Kathryn Gordon, Marisol Perez, Rheeda Walker, Foluso Williams, and Thomas E. Joiner, Jr. 2006. Suicide and positive cognitions: Positive psychology applied to the understanding and treatment of suicidal behavior. In Cognition and Suicide: Theory, Research, and Therapy. Edited by Thomas. E. Ellis. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 261–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2021. Suicide. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Wu, Yi-Jhen., and Michael Becker. 2023. Association between School Contexts and the Development of Subjective Well-Being during Adolescence: A Context-Sensitive Longitudinal Study of Life Satisfaction and School Satisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 52: 1039–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y. S., W. W. Chang, Y. L. Jin, Y. Chen, L. P. He, and L. Zhang. 2014. Life satisfaction, coping, self-esteem and suicide ideation in Chinese adolescents: A school-based study. Child: Care, Health and Development 40: 747–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, Paul, Saman Yousuf, Chee Hon Chan, Tiffany Yung, and Kevin Wu. 2015. The roles of culture and gender in the relationship between divorce and suicide risk: A meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine 128: 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım-Kurtuluş, Hacer, Kadir Meral, Emin Kurtuluş, and Harun Kahveci. 2022. The relationship between spirituality and psychological wellness: A serial multi-mediation analysis. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies 9: 1160–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| b | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family functionality | 0.293 | 11.43 | <0.001 |

| Religiosity | 0.113 | 4.36 | <0.001 |

| School satisfaction | 0.235 | 9.11 | <0.001 |

| Spirituality | 0.120 | 3.95 | <0.001 |

| b | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family functionality | 0.051 | 0.180 | <0.001 |

| Religiosity | 0.092 | 0.028 | <0.001 |

| School satisfaction | 0.032 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| b | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family functionality | 0.159 | 6.71 | <0.001 |

| Religiosity | 0.543 | 22.65 | <0.001 |

| School satisfaction | 0.073 | 3.05 | <0.001 |

| Direct | Indirect 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | p | b | t | p | |

| Family functionality | 0.286 | 11.09 | <0.001 | 0.135 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Religiosity | −0.051 | −1.74 | 0.081 | 0.075 | 2.52 | <0.001 |

| School satisfaction | 0.057 | 2.25 | <0.001 | 0.135 | 0.020 | <0.001 |

| Direct | Indirect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | p | b | t | p | |

| Family functionality | −0.169 | −5.540 | <0.001 | −0.146 1 | 0.022 | <0.001 |

| Psychological well-being | −0.186 | −5.670 | <0.001 | −0.029 2 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Positive suicidal ideation | −0.212 | −6.640 | <0.001 | |||

| Spirituality | 0.010 | 0.294 | 0.769 | −0.051 3 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| School satisfaction | 0.004 | 0.139 | 0.890 | −0.107 | 0.021 | <0.001 |

| Religiosity | −0.050 | −1.510 | 0.130 | −0.027 1 | 0.012 | <0.050 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Euseche, M.; Muñoz-García, A. Influence of Ecological Factors and Internal Resources on Adolescent Suicidal Ideation: An Empirical Study in Colombia. Religions 2025, 16, 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111352

Euseche M, Muñoz-García A. Influence of Ecological Factors and Internal Resources on Adolescent Suicidal Ideation: An Empirical Study in Colombia. Religions. 2025; 16(11):1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111352

Chicago/Turabian StyleEuseche, Mario, and Antonio Muñoz-García. 2025. "Influence of Ecological Factors and Internal Resources on Adolescent Suicidal Ideation: An Empirical Study in Colombia" Religions 16, no. 11: 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111352

APA StyleEuseche, M., & Muñoz-García, A. (2025). Influence of Ecological Factors and Internal Resources on Adolescent Suicidal Ideation: An Empirical Study in Colombia. Religions, 16(11), 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16111352