Abstract

The longevity of popular religions in China is primarily attributed to their strong adaptability. This study uses online ethnography to examine the Pageant on Immortals event in Changle, which became a popular topic on the Chinese Internet in February 2024, to explore the identity transformation of popular religious inheritors and innovations in religious rituals. This study contributes to the research on the diversity of Chinese religious cultures by addressing the question of what emotions young people in an atheistic society hold toward deities like “Prince Zhao,” and how are these emotions generated? Here the Pageant on Immortals event, the “Deities,” who traditionally held a subsidiary position to the main god, due to changes in statue-making styles and gaps in mythological narratives, resonates with the “daily superstition” practices of contemporary Chinese youth. This shift has led participants to treat the deities as idols, and the organizers have transitioned from traditional roles of religious merchants or ritual specialists to seeing themselves as the “dolls’ masters.” However, these changes and innovations present challenges for the transmission of faith.

1. Introduction

The Pageant on Immortals (游神) is a Chinese folk belief activity that mimics a parade of deities, typically occurring in villages and towns along China’s southeastern coast, with Fujian and Guangdong being the most popular regions. The Pageant on Immortal Events is usually held during significant traditional festivals such as the New Year or the deity’s birthday. These days, people invite deity statues into a portable shrine, which is then carried and paraded by trained villagers, allowing the statues to directly receive incentives from believers on the streets. The symbolism behind this activity is inviting the deity to descend to the mortal realm, tour the territory, and bestow blessings of peace and safety on the local people (Liu et al. 2024).

In February 2024, Changle District in Fuzhou, China, held a pageant at an immortal event. Unlike previous events that were mainly confined to villages and attracted little outside attention, this event garnered significant attention on the Chinese Internet. Videos documenting the event frequently appeared on the homepage recommendations of Douyin (TikTok in China) and Xiaohongshu (a social media and e-commerce platform often described as ‘Chinese Instagram’) throughout February and March, accumulating billions of views (Xu 2024). Even the authoritative Chinese newspaper, People’s Daily, published reports on this event. Deities such as “Prince Zhao”(赵世子) and “the Great Prince Huaguang” (华光大世子), who participated in the event, particularly captured the interest of young Chinese people. Many young Chinese traveled from various parts of China, and even abroad, to see deity statues in person and participate in the Pageant on Immortals event (Ratings and Reviews 2024).

As a long-standing Chinese folk belief, the origins of the Pageant on Immortals can be traced back to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 AD) and the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 AD), giving it a history spanning several centuries (Hu and Huang 2012). In the 21st century, communities in Fujian and Guangdong as well as Chinese diasporic communities in Malaysia and Singapore have continued the tradition of regularly holding the Pageant on Immortals. To date, thousands of such events have occurred, yet none have garnered as much attention as the Changle Pageant on Immortals in February 2024.

Compared to similar events in Malaysia, Singapore, and Taiwan, Changle’s Pageant on Immortals distinguishes itself in three key ways. First, it strategically utilizes the visual and algorithmic features of localized platforms, such as Xiaohongshu and Douyin, because they align with Chinese youth popular culture. This digital mediation transformed the event into a widely circulated network spectacle through short videos and aestheticized posts. Second, the event saw an “idolized” reimagining of deity imagery. Some divine figures were visually reconfigured to appear younger, cuter, and more individualized—echoing the visual logic of fan culture. While Taiwan’s Electric-Techno Neon Gods involve cartoonization (Liu et al. 2024), they focus on performativity and symbolic clarity. Changle’s version foregrounds emotional appeal and pop-cultural charisma, offering an affective re-encoding of sacredness. Third, the pageant attracted extensive non-belief participation from secular youth—tourists, content creators, and casual viewers—who engaged with the event as a social spectacle rather than a religious ritual. This shift redefined the function of the pageant, embedding it within a fluid, performative, and secularized cultural space rarely seen in traditional religious processions.

Current research on the Pageant on Immortals in China primarily focuses on the history and cultural transmission of the Pageant on Immortals (Guo and Yang 2017; Yuan 2023), as well as the craftsmanship involved in making deity statues (Lin and Zheng 2023). In recent years, with the widespread use of the Internet, studies have begun to explore how digital technology (Liu et al. 2024) and short videos (Lin and Li 2023) impact the dissemination of the Pageant on Immortals. While some research mentions the Pageant on Immortals in Changle, it is typically treated as a regular case without analyzing its distinct characteristics or delving into the deep emotions Chinese youth have toward the pageant’s events.

To fill this research gap, this study employed digital ethnography and online participant observation. The observation period spanned from February to June 2024. The primary platforms observed included Douyin, Xiaohongshu, and Sina Weibo (China’s largest social media site, equivalent to X). These platforms were chosen for their popularity among Chinese youth and their extensive use by Changle villagers participating in the Pageant on Immortals. The analysis of content on these platforms revealed key themes and trends related to the Changle Pageant on Immortals. This included how participants and observers interacted with the event digitally, expressed their beliefs and cultural values, and reflected broader shifts in the modernization of popular religion in China. The findings highlight the role of social media in shaping contemporary religious practices and belief mechanisms among Chinese youth, offering insights into the evolving landscape of popular religion in the digital age.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Pageant on Immortals in Changle: Legitimate Religious Activity in Ritual Terroir

As a vast, resource-rich country, China has a diverse range of religious traditions. It is important to note that deity worship in China is not evenly distributed but shows clear regional tendencies. Some areas, such as the southeastern coastal regions where Fujian and Guangdong are located, exhibit higher religious activity, continuity, and prevalence than other areas, such as the northern regions where Beijing and Tianjin are situated. Chau (2021, pp. 25–30) refers to these places with vibrant religious life as “ritual terroir.” The concept of “ritual terroir” borrows its meaning from the original usage of “terroir” in agricultural and viticultural contexts, emphasizing how distinct natural and cultural conditions of a given locality provide the fertile “soil” necessary for the development and endurance of ritual life. In this sense, the vitality of a ritual terroir is derived from local resources—geographical specificity, community structures, and embedded ritual traditions—that allow religious practices to take root and evolve. Without such a foundation, religious practices often struggle to sustain themselves over time.

The formation of ritual terroirs relies on the transmission of religious traditions. According to Chau (2021, pp. 1–4), an active and innovative religious tradition must meet the following three conditions: first, important components of the tradition, such as religious symbols, methods of transmission, texts, and ritual implementations, must be accessible and applicable in practice; second, individuals must be interested in using these religious elements and willing to engage in religious activities; and third, the political and socioeconomic environment of the area must be conducive to the development of religious practices. In other words, in addition to the accessibility of religious elements and efforts of local believers, support from local governments and merchants is necessary.

This is relatively rare in the Chinese context because, following the restrictions on religious diversity during the Republican period (1912–1949) (Zhe 2015) and the suppression of “feudal superstitions” after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the country, now Marxist atheist as the core of its ideological propaganda, has become one of the countries with the lowest proportion of religious believers globally. According to a survey published by WIN-Gallup International in 2015, 61 percent of people in China identified themselves as atheists and 29 percent as non-religious (Wingia 2015). Apart from Buddhism, Catholicism, Islam, Protestantism, and Taoism, the five major religions recognized by the Chinese government, the survival space for other religions is relatively narrow. The sacred sites of the five major religions are typical examples of ritual terroir. For instance, the four famous Taoist mountains in China—Mount Wudang in Hubei, Mount Longhu in Jiangxi, Mount Qiyun in Anhui, and Mount Qingcheng in Sichuan— hold temple fairs and religious ceremonies annually.

However, this does not imply that the activity of Chinese popular religion—sometimes referred to as the “diffused” religion or the “lay” religion (Shahar and Weller 1996, p. 1)—has diminished in academic research. In contrast, after understanding the policies of the authorities, popular religion demonstrated even greater vitality than the five major official religions. Chau (2021, p. 6) categorized the legalization strategies of the Chinese religion into two types. The first is “getting into the official fold,” which involves obtaining the status of belonging to one of the five officially recognized religions. In practice, it can be proven that the deity being worshiped has some connection with traditional Chinese religions, such as Taoism or Buddhism and has obtained local government approval to legally hold religious activities. For instance, when reporting on deities like Mazu and Emperor Huaguang, which often appear in the Pageant on Immortals events, Chinese official media describe them as “deities with Taoist elements” rather than “Taoist deities” (NetEase 2024). The second strategy is “creative dissimulation,” which is to disguise one’s religious activities as something else that is more palatable in official eyes (Chau 2021, p. 6). For example, the official promotion of the Changle Pageant on Immortals event describes it as a “folk activity inheriting Chinese intangible culture” rather than a religious ritual. In addition to employing these two strategies on a macro level, the Changle Pageant on Immortals event in February 2024 also practiced two critical elements on a micro level: the master of dolls and idolized deity dolls. These elements ultimately contributed to the immense success of the Changle Pageant on Immortals in February 2024.

2.2. The Master in the Changle Pageant on Immortals: Master of the Dolls

Based on the observations and statements collected from Changle villagers participating in the Pageant on Immortals on platforms such as Douyin, Xiaohongshu, and Sina Weibo, the key points of their preparations can be summarized as follows: On one hand, although the Pageant on Immortals is held annually, before each event, a divination ritual called “Wenbei” (问杯) is conducted to seek the deity’s guidance. This involves considering whether the deity agrees with the event by throwing moon blocks (two specially crafted wooden pieces used as religious tools for communicating with deities). If one block lands face up and the other faces down, it signifies the deity’s consent. If both blocks land face up, it means that the deity is undecided and needs to be consulted again. If both blocks land face down, it indicates the deity’s disapproval. On the other hand, the believers who finance the creation of the deity statues are referred to as “masters” (东家). They were not only the worshippers and caretakers of the statues, but also the main financiers of each Pageant on Immortals. Although the overall costs of the Pageant on Immortals are primarily covered through fundraising by the organizing villages or towns, the masters still bear the expense of moving the statues. Therefore, the masters play a crucial role in the entire Pageant of the Immortal event.

To some extent, the master takes on the role of “secular entrepreneurs” commonly found in traditional religious studies. Secular entrepreneurs typically have a background in a secular business venture. They bring business skills and entrepreneurial abilities to religious projects. Generally, secular entrepreneurs not only participate in donations, but also take charge of investing in and managing local religious activities. For example, they may create parks, gardens, hotels, and other secular spaces around temples to attract more visitors, thereby helping religion to integrate into broader cultural and social landscapes. They maintain good relationships with local government officials to ensure the legality of their religious activities (Chan and Lang 2011). However, unlike secular entrepreneurs who are “not primarily motivated by religious goals,” the masters, as worshippers, at least outwardly demonstrate sincere faith and loyalty to the deities. They also possess professional religious knowledge that secular entrepreneurs typically lack. For instance, the master of the Great Prince Huaguang responded in detail to questions from netizens on Douyin, such as “Is it permissible to attend the Pageant on Immortals during menstruation?” and “Is the Great Prince the main god?” Therefore, from this perspective, the master also fulfills the role of a ritual specialist, possessing specific knowledge and skills to ensure that religious ceremonies are conducted according to tradition and norms (Chau 2020).

Interestingly, the masters participating in this Changle Pageant on Immortals did not intentionally highlight their identities as “secular entrepreneurs” or “ritual specialists” on the Internet. They even showed clear resistance to the former role. For instance, “Yanxi,” the master of the Great Prince Huaguang, responded to a netizen’s question about whether there was money to be made from the Pageant on Immortals and if masters could earn a lot from it. She stated, “These are comments from people who do not understand. For each Pageant on Immortals, we have to pay each specialized Bearer of the Pagoda Bone (塔骨)1 (workers who help move the deity statues during the ceremony) 300 RMB. Each statue requires four people to carry it. Meals were also provided. Additionally, we donate 3000–5000 RMB for each event during village fundraising (the average donation per household is 1000 RMB). The candies given to visitors in the name of the deity are also purchased by us” (Excerpt from Douyin, account: Yanxi).

This indirectly indicates that placing economic interests above religious faith was not welcomed by the Pageant on Immortal activities. Both believers and visitors generally consider religious ceremonies a vital means of communicating with deities and expressing faith and respect. Showing too much concern for economic benefits would be viewed as an insult to the sanctions on the event. Therefore, masters refuse to identify themselves as secular entrepreneurs and emphasize their selfless contributions. Given the strict scrutiny of religious information in China’s media environment, the religious knowledge shared online by these masters is relatively limited. This limitation prevents them from becoming typical ritual specialists.

However, compared to the relatively resisted identity of “secular entrepreneurs” and their non-typical role as “ritual specialists,” the masters involved in the Changle Pageant on Immortals uniformly emphasized their ownership of the deity statues. Yanxi, the master of the Great Prince Huaguang, stated, “The Great Prince Huaguang was crafted by my husband and me; we are forever his masters.” Similarly, Prince Zhao’s master, another deity that garnered significant attention in the Changle Pageant on Immortals February 2024, responded directly to a netizen’s question about when Prince Zhao would next tour the mortal realm.

“It depends on my mood; my mood represents his (Prince Zhao’s) mood.”“I will arrange the tour as you wish, but if there is another instance of online bullying toward my sister, I will not arrange for Prince Zhao to appear after this year’s New Year’s celebrations.”.(Excerpt from Douyin; account: Lin Laoliu from Xinglongshe)

In art anthropology, deity statues in temples are considered as media for gods, providing a temporary body for the deity. Consequently, people, especially believers, are expected to treat these statutes with respect and reverence (Gell 1998, p. 7). Scholars studying Vietnamese deity statues have documented numerous accounts from fieldwork, where believers reported retributions for acts of disrespect toward temple statues. One notable act of disrespect is the “privatization of deity statues.” This encompasses both the financial privatization of trying to sell statues and the power privatization of prohibiting statues from being shown to the public. Such actions treat deity statues as personal possessions that contradict religious rituals. Even if a deity statue is placed in a private temple, the temple should clearly distinguish between ritual and family spaces (Kendall et al. 2010).

If the claim of “eternal master” made by the master of the Great Prince Huaguang can be seen as a relatively mild expression of deity statue ownership, primarily emphasizing their role in the transmission of the deity’s legacy, then the master of Prince Zhao exhibits a more intense personal sentiment and desire for control. This master even implies that “his (human devotee’s) authority in the entire Pageant on Immortals ritual is superior to that of Prince Zhao (as the divine medium).” Such highly personalized control is extremely rare in traditional religious contexts, as it blurs the boundaries between the sacred and the secular.

However, if sacred deity statues are replaced by secular dolls, the attitudes and actions of the master will become understandable and more acceptable. Deity statues are material embodiments of the divine; disrespect toward them is considered disrespect toward the deity itself and can have serious religious repercussions. By contrast, dolls are merely ordinary material products. The masters’ willingness to publicly assert their ownership of deity statues in ways that contradict conventional religious contexts is due to their abandonment of the roles of secular entrepreneurs and ritual specialists. Instead, they emphasize their identity as “owners of dolls.” This privatization of statues bears notable similarities to the New Age movement that emerged in the West during the 1970s. A defining feature of the New Age movement is the pursuit of individualized spirituality, allowing individuals to construct their own spiritual practices according to personal preferences rather than adhering to established religious traditions. The shifting identity of the masters reflects this trend: they introduce personal and secular elements into their religious experience, forging new connections between daily life and religious belief (Hanegraaff 2000).

However, when New Age teachings entered China in the 1980s through overseas returnees, they were not circulated in their original form. Instead, they were rebranded during the process of localization as “Body–Mind–Spirit” (shen xin ling). This concept refers to an emerging spiritual milieu constructed by networks of self-cultivators who organize and participate in workshops and seminars. These practitioners integrate Euro-American New Age spirituality with elements of “traditional Chinese culture,” including the Traditional Chinese Medicine view of qi and meridians, Daoist practices of cultivating harmony between body and mind, and Confucian ethics emphasizing the integration of personal morality and social responsibility. In addition, Western spiritual concepts undergo processes of “retranslation,” such as rendering “God” as xianxiang (phenomenon) and “spiritual energy” as nengliang—a term used in physics to denote energy. This deliberate “de-religionizing” and “scientizing” of spiritual discourse allows the shen xin ling movement to maintain its appeal while aligning itself with the ideological requirements of China’s core socialist values (Iskra 2022).

It is within this political and cultural environment that patrons’ practices of privatizing deity statues reflect a similar adaptative logic. By incorporating divine images into domestic worship, personal petitions, and even individual emotional experiences, they not only challenge the conventional norm that deity statues should be collectively owned by temples or communities but also transform sacred space into a form of spiritual resource within the private sphere. This practice does not represent a rejection of communal belief systems. Instead, it reveals an individual’s active reconstruction of religious meaning and emotional comfort in the face of modern social uncertainties. As long as it remains within the bounds of political acceptability, this personalized appropriation of divine images effectively redistributes religious authority, allowing ordinary believers greater agency and symbolic capital within the “sacred economy.”

It should be noted that this mode of thought is influenced not only by state ideology and the localization of global spiritual resources but is also deeply embedded in the logic of deity identity construction and the concrete practices of image-making in the Pageant on Immortals in Changle. Within this ritual system, the deity is treated less as an immutable sacred presence and more as a “doll”—a malleable figure to be dressed up and reimagined.

2.3. Changle’s Pageant on Immortals: The Construction of Divine Identity and Statue Crafting—Deities as Dressed Dolls

Although the customs of the Pageant on Immortals vary regionally, a relatively standardized order has been established. Typically, the procession centers around the main deity, who is usually positioned at the rear of the pageant procession, seated in a palanquin. The subordinate deities—often regarded as descendants or attendants of the main god—such as the Great Prince Huaguang, Prince Zhao, and the prominently featured female deity, the Five Plague God’s Grand Princess, walk ahead of the main deity. These subordinate gods are manifested through the ritual practice of “wearing the pagoda bones,” whereby devotees physically carry or don symbolic structures representing these divine figures, thereby “opening the way” for the main god’s procession. For example, one of the main gods, Mazu, was originally an ordinary fisherwoman from a small fishing village in Fujian Province during the Northern Song Dynasty. She learned magical arts from a young age, and after helping unfortunate fishermen, ascended to become a deity. Another frequently featured main god, Emperor Huaguang, was originally a frame of the Buddha, and after being enlightened, became a disciple of the Buddha. However, in violation of the rules, he was demoted to the mortal realm, where he underwent several reincarnations before attaining divinity. By contrast, subordinates often lack independent stories or specific secondary origins.

In the devotees’ accounts, the Great Prince Huaguang is described as the son of Emperor Huaguang. However, in the literature related to Emperor Huaguang, such as The Grand View of Chinese Deities (Ma 2005) and A Journey to the South (Yu 2001), there is no mention of a figure named the Great Prince Huaguang. The descriptions of Emperor Huaguang’s family only state that “Emperor Huaguang, in his quest to rescue his mother, not only fought with the deities in the heavenly court but also ventured into hell to find her. During this quest, he met Princess Iron Fan and married her” (Yu 2001), with no mention of him having a son. The folklore surrounding the Great Prince Huaguang is also extremely vague, with the only available description being that “the Great Prince Huaguang inherited his father’s three eyes and is said to possess abilities to traverse space and control time” (Sohu 2024). Questions such as who his mother is, how he uses his abilities, and whether he has ever descended into the moral realm for training remain unaddressed. In 2024, Changle’s Pageant on Immortals, the most notable Pagoda Bone statue, Prince Zhao, could not be categorized into any specific main god faction. Neither the master of Prince Zhao provided relevant background information nor did the event organizer introduce his origins. Several theories currently circulating on the Chinese Internet include: 1. Prince Zhao is a modern martyr; 2. Prince Zhao was inspired by the other belief systems. For example, residents of the Thirteenth Township of Nantai, Fuzhou, reverse Marshal Wen, and Marshal Kang were the main gods while also worshiping their subordinates and sons in the temple. Prince Zhao’s origin is thought to stem from a belief system prevalent along the southeastern coast of China that involves creating offspring or subordinate deities for the main gods. 3. Prince Zhao is believed to be the youthful form of Wufu Emperor Zhao Gongming, who sacrificed his life to protect people from the plague (Ling and Zhao 2024). The same applies to the Five Plague God’s Grand Princess, a female deity who has attracted considerable attention in the Changle Pageant on Immortals. She is described as the daughter of Zhang Yuanbo, one of the Five Plague Gods who governs the plague of spring, and is believed to possess divine powers that ensure favorable weather and the peace and prosperity of the nation. However, despite various interpretations and local legends, none of the figures—including Great Prince Huaguang, Prince Zhao, and the Five Plague God’s Grand Princess—have a fully developed, cohesive mythological narrative.

In the study of religion, myths and legends serve as crucial media for understanding the lives and deeds of the deities and establishing faith. They act as evidence of the deities’ past existence and manifestations, thereby sustaining the vitality of beliefs (Mullen 1971). Christianity’s prosperity owes much to the widespread dissemination of biblical stories. Of course, myths and legends about deities are not static; as Chinese scholar Yang (2014). has proposed with the concept of “new mythologism,” contemporary society continuously ascribes new functions and meanings to myths based on cultural needs and aesthetic changes. However, despite variations in the way divine stories are told and detailed, the core foundation that establishes the divine status remains unchanged. For example, the character of Sun Wukong, who is frequently adapted to contemporary Chinese cultural products, can be portrayed in various ways: as a vengeful deity in the film Wukong (2017), as a weakened and exhausted demon in the animated movie Monkey King: Hero Is Back (2019), or as an innocent young man in a romantic relationship with a woman in the Hong Kong film A Chinese Odyssey Part I—Pandora’s Box (1995). Despite these variations, all adaptations invariably highlight Sun Wukong’s non-human nature and behavior, thereby alluding to his monkey demon background.

If a deity has never possessed a complete story, not only is faith difficult to transmit but its sanctity is also challenging to establish. Deities such as the Great Prince Huaguang, Prince Zhao and the Five Plague God’s Grand Princess in the Changle Pageant on Immortals are in this awkward situation, with all aspects of their divinity, powers, and authority remaining unclear. In the Chinese religious system, which tends to emulate secular frameworks and emphasize the personalization of deities (Xu 2024), this is an exceedingly rare phenomenon. Compared to deities, their status is more akin to that of dolls. Much like the fashion doll “Barbie,” these “descendants of deities” are endowed with names and beautiful appearances but lack a recognized and transmissible classic text that nurtures faith. All the interpretive authorities reside with the owner of the doll.

In addition to having the authority to explain the deities’ origins, stories, and genealogies, the master also has the power to alter the appearance of the deity. As previously mentioned, due to the absence of authoritative textual references for these deities’ descendants, the masters who finance the statue-making process enjoy significant autonomy in determining the statues’ physical characteristics according to their own preferences. In other words, the lack of canonical texts on these deities has, paradoxically, created an ideal environment for the dissemination and practice of Body–Mind–Spirit thought. This allows the masters to become both the creators and interpreters of the statues, integrating their own secular concerns into religious practice. In traditional religious contexts, the appearance of statues tends to remain relatively stable to preserve their authority as sacred mediums. If a statue’s appearance were to undergo continuous changes, this fluidity would undermine its stability and uniqueness as a vessel for the divine, ultimately reducing it to an ordinary commodity indistinguishable from dolls. However, based on some online statements from masters, their primary motivation for altering the statues’ appearances is not merely personal belief but rather the desire to attract greater attention and further expand the ritual economy (Chau 2011).

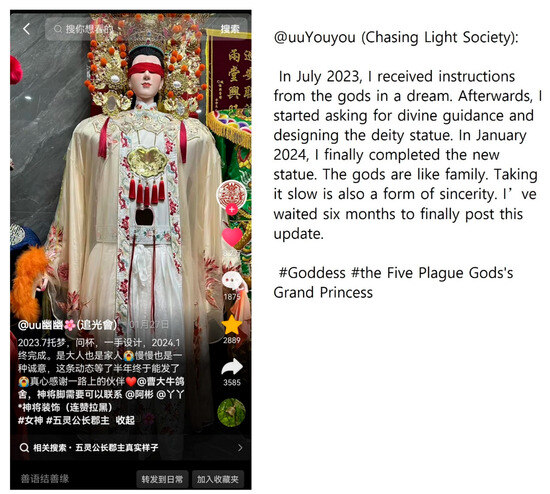

Given the potential controversies surrounding arbitrary modifications to the statues’ appearances, most masters justify these changes by invoking the notion that “a deity will reveal himself or herself in dreams” (Lin 2008). For instance, uuYouyou (Chasing Light Society), the master of the Five Plague God’s Grand Princess, used this rationale to explain their decision to alter the appearance of the Five Plague God’s Grand Princess (Figure 1). This is a common pattern in the creation of a deity status. Devotees believe that dreams serve as a bridge between the divine realm and the mundane world (Abusaidi 2013), and that the information received in dreams comes from divine indications rather than one’s subconscious thoughts. Through this justification, the masters adeptly frame their unilateral decisions to alter the appearance of dolls as a response to divine guidance and adherence to prophecy, thereby integrating personal desires with divine authority and leading devotees to accept and endorse changes.

Figure 1.

uuYouyou (Chasing Light Society) explaining the process of re-sculpting the Five Plague God’s Grand Princess deity statue on Douyin (image: uuYouyou (Chasing Light Society) Douyin account).

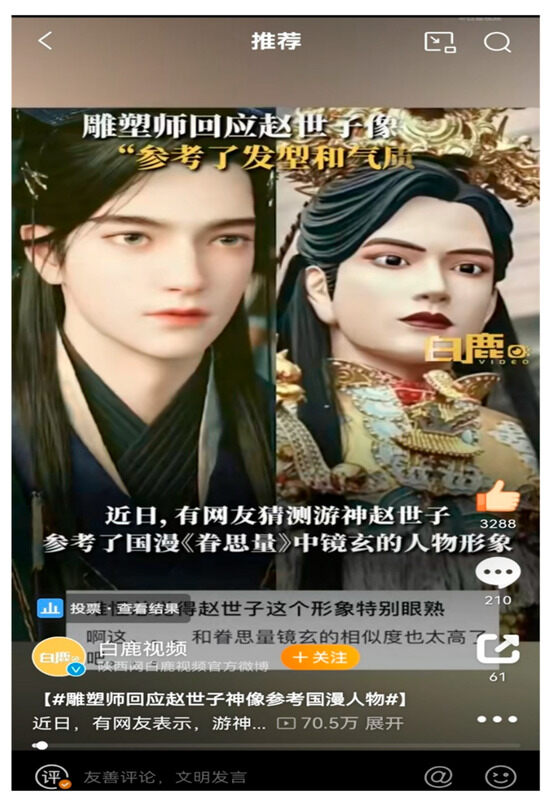

However, some masters have skipped this process. For instance, Prince Zhao’s master explicitly mentioned that the statue of Prince Zhao for the 2024 Changle Pageant on Immortals was inspired by the hairstyle and demeanor of the Chinese animated character “Jing Xuan” (Figure 2). This candor largely explains the changes in the style of the Pagoda Bone deity statue. In the past, masters who were identified as devout worshippers followed traditional practices when sculpting deities, prioritizing the statue’s ancient appearance, or highlighting its divine features that were distinct from those of humans. In contrast, younger masters, who see themselves as “doll’s owners” doll owners, prioritize their own aesthetic preferences and needs. Consequently, the Pagoda Bone deity statues of Changle’s Pageant on Immortals (February 2024), were crafted to resemble beautiful idols popular in contemporary Chinese pop culture, creating a striking contrast with traditional deity statues (see Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Comparison between the statue of Prince Zhao (right) and the Chinese animated character “Jing Xuan” (left) (image: White Deer Video (2024)).

Figure 3.

Comparison between the statue of Prince Zhao (left) and the traditional Pagoda Bone statue style (right) (image: “Do you eat chili?” Douyin account).

It should be emphasized that beyond the role of the masters who fund the statues, the devotees responsible for sculpting and the specialized “Bearers of the Pagoda Bone” also play a crucial role in the construction of new mythologies surrounding these “divine descendants.” First, they invest significant effort and manpower in crafting the statues and smoothly executing the Pageant on Immortals ceremonies, ensuring not only the statues’ mobility and visual impact on a technical level but also continually enriching the ritual’s performative aspects in practice. Second, through their involvement in the creation and circulation of the statues, they actively or passively contribute to the reinterpretation and reconfiguration of the deities’ visual iconography and familial lineages, thereby enabling the development of more individualized and localized narratives of “divine descendants” within contemporary belief systems. For example, in the 2024 Changle Pageant on Immortals, the artisan responsible for crafting the statue of the Five Plague God’s Grand Princess was a woman. Even before receiving the commission, she dreamed that she “would soon sculpt a deity.” When she was consulted through the “casting divination” ritual about whether the Grand Princess approved her undertaking, the ritual yielded an immediate affirmative “holy cup,” signaling the deity’s clear consent and acceptance. Notably, the patron funding the Grand Princess’s statue was also female. The active involvement of these women in the processes of statue patronage and ritual performance not only enhances the visibility of female agency in religious practice but also reflects a continuation and reaffirmation of women’s roles in the broader context of Chinese religious traditions.

When Buddhism was first introduced to China—during the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE)—Guanyin Bodhisattva originally appeared in a male form. However, as local religious systems evolved—especially under the heavy constraints of feudal military power, clan order, and patriarchal structures—women, who had limited opportunities for expression, participation, and self-realization in society, gradually turned to religion as an alternative avenue for spiritual sustenance and social engagement. Against this backdrop, Guanyin’s image was feminized over time, eventually becoming the compassionate “female Guanyin” who protects all beings (Jiao 2015; Valussi 2020). This transformation reflects the psychological needs of female devotees and demonstrates the cultural capacity of the Han Chinese religious system to reconstruct gender roles (C. Liu 2015).

Similarly, although the Grand Princess in the contemporary Pageant on Immortals in Changle did not undergo a gender transformation, the construction of her divine identity and visual representation nonetheless supports local women’s aspirations for “sacred femininity.” Through the joint involvement of a female sponsor and a female artisan, the deity has been imbued with stronger connections to contemporary life and gendered meaning. Since the Chinese government initiated its Reform and Opening-Up policy in 1978, Chinese scholars, influenced by Western feminist thought, have begun developing indigenous feminist theories and critical practices, questioning earlier portrayals and realities of women in mainstream Chinese culture and society (Wu and Cheng 2024). Entering the twenty-first century, the rapid development of the internet has further amplified Chinese women’s capacity and willingness to speak out on gender issues, overcoming prior spatial fragmentation and fostering greater discursive cohesion and solidarity (Huang and Li 2021). For example, during the transnational #MeToo movement, Chinese women exhibited strong mutual support and collective consciousness, actively enacting the “girls help girls” ethos through practices of solidarity (Lin and Liu 2019). A similar gendered dynamic is evident in Changle’s Pageant on Immortals, where the collaborative production of the Grand Princess’s image—between a female patron and a female artisan—constitutes a ritualized form of feminine alliance. This alliance, embodied in religious iconography and local practice, not only reframes the reproduction of sacred authority through a gendered lens but also positions vernacular religion as a site of engagement with contemporary gender discourse.

Thus, unlike the main gods in traditional Chinese religion, which remain in temples or in palanquins during the Pageant on Immortals, thereby maintaining a distance from worshippers, the “descendants of gods” have taken on two distinctive features of dolls: the ability to change their appearance or attire at will and a close relationship with the audience. However, they still superficially fulfill the role of “divine vessels.” This differentiates them from ordinary collectible dolls, such as Barbie-style dolls, making them unique sacred dolls. From the dissemination effect of the Pageant on Immortals in Chang Le, this “deity as doll” religious strategy has indeed made the gods feel more relatable to young Chinese people, allowing them to interact with the deities in a manner akin to their treatment of idols.

2.4. The New Generation of Followers in Changle’s Pageant on Immortals: Chinese Youth and the Practice of Daily Superstition

Despite the establishment of Marxist atheism as the core of China’s religious policy since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 (Barrett 2022), many Chinese youths who grew up under this atheistic education system often identified themselves as non-believers (Bullivant et al. 2019). However, a lack of religious belief or identification with any particular religion does not imply disinterest in nonscientific or irrational phenomena. In contrast, according to research by the Chinese scholar H. Liu (2020), many young Chinese people believe in concepts such as astrology and the law of conservation of luck. Liu refers to the Chinese youth’s obsession with these concepts as “daily superstition.” He argues that even in modern Chinese society with abundant resources and comprehensive social services, people still experience value differentiation and uncertainty because of social stratification and the unknown risks of scientific rationality. Faced with these challenges, combined with the complexity of the new media environment, Chinese youth are drawn to using social media to irrationally explore and interpret their relationships with the external world. This process includes entertaining attributions of individual aspirations and achievement conditions. It is important to note that Liu’s concept of daily superstition differs from the term superstition in the Chinese religious context. The latter carries a pejorative connotation, often used to delegitimize religious beliefs, whereas daily superstition refers more to irrational belief practices embedded in everyday life. From this perspective, Liu’s definition of daily superstition aligns more closely with the concept of “Xuan Xue” (玄学) in Chinese internet discourse. The term “Xuan Xue” originates from the philosophical movement of the Wei and Jin dynasties, deriving its name from the final line of the first chapter of Laozi’s Dao De Jing: “玄之又玄, 众妙之门” (“Profound and ever more profound, it is the gateway to all wonders”). In contemporary Chinese online discourse, Xuan Xue has been broadly reinterpreted by internet users to refer to mysterious phenomena that defy scientific explanation, commonly encompassing practices such as divination, feng shui, fortune-telling, and folk beliefs. Liu also acknowledges this phenomenon in his study. However, given that the concept of Xuan Xue only began to gain traction in online discourse around 2014–2015 and its meaning and scope continue to evolve, it has yet to solidify into a stable, rigorous academic concept. As a result, Liu opts for the more universally comprehensible term daily superstition in his research, a choice that this study will also adopt.

The development of daily superstition among China’s younger generation has evolved alongside the growth of the Chinese internet, progressing through three stages. The first stage occurred between 2000 and 2008. During this period, when the Chinese Internet became widespread, Chinese netizens began to believe in the “law of conservation of personal virtue,” which posited that a person’s virtues, such as kindness and honesty, would bring them good luck, whereas negative behavior would result in bad outcomes. The second stage, from 2009 to 2018, is marked by the launch of Sina Weibo. During this period, the “daily superstition” of Chinese youth began to exhibit clear group characteristics and stratification. They grew tired of the highly conceptual “law of conservation of personal virtue” and instead developed a strong interest in astrology, which offered more concrete explanations of personal fate and a well-developed theoretical system. Simultaneously, they began to place their hopes in tangible objects such as “Koi fish,” creating large-scale online prayer activities like “sharing this picture of a Koi fish online will bring you good luck” (H. Liu 2020). The third stage began in 2020 and continues to the present day. After the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), a personality type-theory model based on psychological theories created by American writer Isabel Briggs Myers and her mother Katharine Cook Briggs, was introduced in China, Chinese youth endowed it with social and entertainment attributes. They began using this model to interpret their personalities and choices, finding a sense of belonging and identity within groups of people who shared their MBTI types. However, despite the MBTI’s roots in psychological theory, the model itself, which originated in the 1940s, has many issues, such as overly absolute type classifications, low reliability and validity of the tests, and outdated questions (You and Zhao 2024). Thus, fundamentally, the MBTI presents the appearance of being scientific in form but unscientific in outcome, making it a part of daily superstition.

The primary distinction between daily superstition and traditional religious systems lies in the latter’s structured doctrines, rituals, and organizational frameworks, which require adherents to follow explicit beliefs and behavioral norms. Hanegraaff (2000) defines religion as a symbolic system that functions as a “carrier of meaning.” For example, when a Christian attends church on a Sunday, they enter a space filled with objects, words, images, sounds, and actions that together form a meaningful whole. Their traditional religious education enables them to understand this whole, its individual components, and their significance. Beyond private religious practice, they may also encounter symbols they immediately recognize as “belonging to their own” religion, alongside others that belonging to an “other.” In contrast, daily superstition lacks fixed doctrines and organizational structures, relying instead on personal or communal experiences and cultural habits. The objects of belief and modes of practice in daily superstition are fluid, changing over time, and characterized by greater flexibility and entertainment value. Moreover, it does not reject the blending or borrowing of elements from different religious traditions. As a result, in China, daily superstition enjoys a more relaxed and unrestricted space for survival and dissemination.

To some extent, daily superstition can be categorized under the broader framework of popular religiosity. First, both are strongly practice-oriented, emphasizing the attainment of practical outcomes through specific actions rather than purely theological reflection or doctrinal inquiry. Adherents focus on how supernatural forces influence real-life affairs, often with explicit aims such as seeking wealth, ensuring safety, or praying for good fortune. Second, both emphasize personal experience and direct perception rather than strictly adhering to religious scriptures or authoritative institutional interpretations. In popular religiosity, believers often acquire their faith through personal experiences, local traditions, or oral transmission, rather than relying on formal theological teachings. Similarly, daily superstition tends to be individually interpreted and applied. For example, people may follow certain folk beliefs due to familial or community influence, or they may adopt new superstitious practices based on social media trends. Both are highly inclusive and adaptable, capable of evolving within different cultural contexts. While popular religiosity integrates with local customs and social practices, daily superstition absorbs elements from modern psychology, popular culture, and even social media, making its practices more aligned with contemporary needs. Third, both serve similar social functions, providing emotional comfort, social cohesion, and psychological reassurance for individuals facing uncertainty or stress.

However, it is important to note that while popular religiosity often possesses a degree of historical continuity, daily superstition is typically transient and fluid, easily shifting under the influence of new media trends. In this sense, daily superstition can be seen as an adaptive variant of popular religiosity in the digital era. Built upon the fusion of religious and secular elements, it is further embedded within social media’s sharing mechanisms and the logic of the attention economy. This transformation is steering religious practices toward what Reinis and Laughlin (2025) term algorithmic spirituality—a form of belief shaped by digital platforms, personalized recommendation systems, and the dynamic interplay between technology and spirituality.

First, daily superstitions emphasize its everyday nature. Daily superstition can grow relatively freely within China’s cultural environment and continually cultivate new generations of audiences because of its close connection with the daily lives of Chinese youth. The “daily” aspect of daily superstition can be divided into two main facets. Although the media objects it relies on contain irrational elements, these characteristics are concealed. For example, while horoscope predictions and MBTI tests fundamentally lack a scientific basis, the former uses astronomical terms like “planetary movements” and “retrograde motion” for explanations, and the latter’s model is based on the personality theory of the renowned Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung. The use of these scientific terms places horoscopes and the MBTI on the delicate boundary between science and superstition, preventing them from evolving into feudal superstitions rooted in fantasy that negatively impact the liberation of people’s minds (Overmyer 2001). Similarly, the Changle Pageant on Immortals has successfully rebranded itself from a traditional religious activity to a cultural event promoting Chinese civilization by packaging itself as “intangible cultural heritage,” making it easily accepted by Chinese youth.

However, the everyday nature of the Changle Pageant on Immortals lies in its provision of various opportunities for Chinese youth to integrate into daily experiences. The lack of classic texts for princely deities, such as the Great Prince Huaguang and Prince Zhao, stimulates the desire of Chinese youth to fill in the gaps. Educated in a socialist system that emphasizes “upholding people’s democratic rule,” Chinese youth are more inclined toward cultural products or activities that allow them to fully exercise their subjective initiative. In Changle Pageant on Immortals, their greatest pleasure is seeking historical records related to the prince deities’ legends or inferring personalities based on their appearances and behaviors. For instance, because Great Prince Huaguang wears a string of candies around his chest (which the master later confirmed was meant to be distributed to believers), newcomers to the pageant culture mistakenly believed that Great Prince Huaguang liked candies, prompting them to offer sweetness to the deity during the event (Baidu 2024). Additionally, they have created paratexts that personify deities, such as “Prince Zhao dislikes going out to meet people.” By crafting these anecdotes, Chinese youth temporarily experience what it feels like to be a “doll owner”: at this moment, they are the creators above the deities, freely writing the deities’ stories.

Additionally, the shift in the style of statue creation has brought a sense of media familiarity to Chinese youth. To align with the aesthetic preferences of the masters and the general public, the style of the statues of “the descendants of gods” in the Changle Pageant on Immortals has leaned toward a realistic and romanticized portrayal similar to real-life idols. This has led Chinese youth to unconsciously treat these deities in the same way as they treat real-life idols.

Popular culture studies often suggest a close connection between idols and dolls. Hiroshi Aoyagi posits that the term “idol” may be a combination of “I” and “doll” (Aoyagi 2020). In the cultural consumption market, idols such as dolls are meticulously crafted commodities controlled by producers and audiences (Black 2008). This mirrors the situation of the Changle Pageant on Immortals. Although Chinese youth may have limited religious knowledge, many have experienced idol worship. According to data from the Chinese state media in 2019, the fan base in China exceeded 500 million, with 50.82% of the post-95 generations being fans of some idols (Guo 2019). Thus, when faced with “descendants of gods” who are strikingly similar to idols—beautiful in appearance, with a thin background (lacking legendary stories), and having significant room for growth (previously only popular in Fujian and Guangdong)—Chinese youth instinctively apply their familiar idol worship practices. They engage in actions such as performing the “Wenbei” ritual to ask if they can marry the deity, which would traditionally be considered disrespectful in a religious context. They also have mobilized online opinions to defend the interests of the deity. In one instance during a Pageant on Immortals event, a male Internet celebrity cosplayed as “Prince Zhao” and walked at the front of the deity parade. Young Chinese netizens perceived this act as an encroachment on Prince Zhao’s spiritual offerings. Before the local government or master responded, outraged young netizens bombarded the celebrity’s social media accounts with insults, ultimately compelling him to apologize and delete all videos related to the Pageant on Immortals. These young people even directly questioned or challenged the master’s status as the true “doll owner.” For example, when they discovered that Prince Zhao’s master had made a gesture such as affectionately touching the deity’s cheek during a live stream, they angrily accused the master of being a profiteer exploiting the deity’s name rather than a devout believer.

To some extent, these behaviors of Chinese youth can be understood as a localized practice of patchwork spirituality (Ferlan 2015), where individuals mix different religious elements and incorporate personal experiences to express their emotions and cultural identity. However, rather than patching together religious experiences, they are assembling media experiences. As a result, the practice of patchwork spirituality in China fundamentally overturns the traditional religious relationship of “deities protecting mortals.” Instead, within the realm of daily superstition, a new dynamic emerges—one in which “mortals protect deities.” Rather than viewing the young participants of the 2024 Changle Wandering Gods festival as a new generation of religious devotees, it may be more accurate to see them as the gods’ fans. Their emotional connection to the deities is not characterized by the reverence and awe typical of traditional religious believers but is instead infused with a complex mix of admiration, affection, and devotion—much like a fan’s relationship with an idol.

Second, daily superstition relies heavily on the Internet. Grieve highlighted that the connectivity and integration of digital media has given rise to specific technological ideologies, providing a workaround for modern living conditions (Grieve 2013, p. 4). Miczek (2013) also believes that the proliferation of the Internet offers religious users the opportunity to showcase personal religious beliefs and engage in proselytizing. While China’s daily superstition does not entirely align with the concept of “digital religion” as defined in Western religious studies, which suggests that online spaces help people ascertain religious meaning, reshape religious culture, social power, and religious identity (Siuda 2021), both phenomena leverage the multimedia nature of the Internet. They use text, images, videos, and other forms to enhance content appeal and dissemination, while granting audiences the right to interpret and accept the content as they see fit. Audiences can select parts they find relevant and even innovate and reinterpret them, rather than accepting them uncritically, as traditional religious believers do. This approach is particularly suited to young people living in a “liquid modern life” (Campbell and Connelly 2020). Numerous scholars have explored the impact of the internet on religion in China—most notably Stefania Travagnin (2016), who edited Religion and Media in China: Insights and Case Studies from the Mainland, Taiwan and Hong Kong. However, the literature has largely focused on the dissemination and practice of religion on three major digital platforms: Sina Weibo (Y. Zhang 2017), WeChat (Han 2022), and Tencent QQ (Xu and Campbell 2018). Emerging platforms, such as Xiaohongshu and Douyin, which have been gaining considerable influence among China’s younger demographics in recent years, have yet to receive systematic academic attention.

Compared to traditional digital platforms such as Sina Weibo, Xiaohongshu and Douyin offer distinct advantages through their visually driven interfaces and algorithmic recommendation systems. By prioritizing short videos and images as primary modes of content dissemination, these platforms rapidly capture viewers’ attention and also use personalized recommendation algorithms to push religion-related content into the feeds of users who are not traditional believers. Thus, they expand the boundaries of religious dissemination. Specifically, Xiaohongshu emphasizes lifestyle construction and emotional sharing. Religious content on this platform often appears under softer and more secularized tags such as “spiritual healing,” “everyday faith,” or “ritual aesthetics.” These framings help navigate China’s content censorship mechanisms as well as resonate with the cultural tastes and emotional needs of Xiaohongshu’s core demographic—young women. Douyin, meanwhile, amplifies the performative and rhythmic aspects of religious activity. Using special effects, background music, and dynamic editing, otherwise static or repetitive rituals are transformed into entertaining and visually appealing “consumable video content” (Z. Zhang 2021). It is through algorithm-driven short video dissemination and emotionally oriented visual storytelling that the Pageant on Immortals in Changle has entered the cultural context of contemporary youth in a visualized, fragmented, and highly shareable form. This process enables a once highly localized religious practice to acquire new modes of imagination and interpretation within the social media space.

Finally, daily superstition is characterized by topicality. Young Chinese people’s enthusiasm for astrology and the MBTI primarily stems from their desire to find common topics in social interactions and to deepen mutual understanding. Changle’s Pageant on Immortals followed a similar pattern. Its popularity on platforms such as Sina Weibo and Xiaohongshu made it a popular topic on the Chinese Internet in February 2024, providing an entry point for building and maintaining interpersonal relationships. Even those who are not particularly interested in the religious ceremony itself may learn about Changle’s Pageant on Immortals to fit into social groups and find a sense of belonging online by treating daily supervision as a social tool.

However, hot topics on social media typically spread and fade quickly as user interests and time change, and Changle’s Pageant on Immortals is no exception. After the event concluded, the interest among young Chinese people gradually declined. For instance, videos posted by Prince Zhao’s master on Douyin received over 2000 likes each in February and March, but the number dropped to a few hundred in May and June. Moreover, the topic-driven nature of daily superstition sets it apart from traditional popular beliefs or folk beliefs. In any religious context, the formation and maintenance of faith typically rely on stable ritual cycles, ensuring that believers engage in repeated practices at fixed intervals to reinforce continuity and a sense of belonging. In contrast, daily superstition, which thrives on generating constant new topics to sustain public attention, aligns more closely with the logic of fast-consumption culture in the modern media environment rather than a stable system of belief.

3. Conclusions

By analyzing the Pageant on Immortals event in Changle in February 2024, this study explores the innovative strategies, impacts, and transformations of popular religion in the context of social media. The findings indicate that in recent years, religious organizers have sought a balance between faith expression and commercial operations, emphasizing both devotion and market-oriented strategies in ritual practices. For instance, the believers (masters) who oversee the Pageant on Immortals navigate between preserving the orthodoxy of traditional religious rituals and adapting to contemporary societal demands. At the same time, they take on the role of managers responsible for the creation, preservation, and veneration of deity statues. This dual identity not only influences the organizational structure of religious practices but also, to some extent, shapes the modern form of deity worship.

The sculptural style of deity statues also reflects a trend toward contemporary aesthetics. Compared to strictly traditional designs, statues that incorporate modern elements in a moderate way tend to attract greater interest from younger audiences. Additionally, the intentional ambiguity in deity narratives enhances audience engagement, making religious expression more open and diverse. At the same time, promotional strategies for religious rituals are adapting to the media habits of younger generations, with short videos and fragmented dissemination expanding the visibility of religious events on social media and, to some extent, reshaping the practices of deity worship.

In the long term, the viral dissemination of content on the 2024 Pageant on Immortals in Changle reveals multiple transformational trends in Chinese popular religion in the digital age. First, the intervention of social media platforms has rendered religious practice increasingly platform-dependent and visually oriented, with religious content reshaped into “visible” and “consumable” cultural products. Second, the idolization of deity imagery has facilitated a shift from sacredness to emotional resonance and personification, turning deities into charismatic and interactive figures of identification. Moreover, the widespread participation of non-believers has transformed religious practice into a type of “participatory social event” rather than a traditional, strictly religious act. The reconstruction of religious narratives by diverse actors—such as female patrons and online users—has also disrupted the authority of temple systems and clerical hierarchies, contributing significantly to the decentralization of religious power relations.

However, alongside these transformations, several concerns emerge that warrant critical attention. First, the increasing entertainment-oriented nature of religious practice risks diluting the symbolic significance of rituals, as their value is often overshadowed by the emphasis on performativity and cultural commodification. Second, the ongoing pursuit of “modernization” and “innovation” may marginalize traditional religious symbols, rituals, and value systems, gradually detaching religious practices from their historical and cultural contexts. Moreover, varying degrees of acceptance across different groups—particularly among devotees committed to traditional rites—can lead to generational tensions and internal fragmentation within religious communities.

Notably, the dissemination and evolution of the Changle Pageant on Immortals reveal a subtle and yet significant shift in the focus of deity worship. In recent years, public attention has increasingly shifted toward the “subsidiary figures” or “marginal roles” of deities, while interest in the primary gods has comparatively declined. This trend alters the visual center of religious rituals and may also give rise to new forms of worship lacking grounding in classical texts. Going forward, such forms of “mediated religious practice” may become a critical lens through which the modern transformation of religion in China can be understood, particularly for how they negotiate the tensions among state governance, secular culture, and collective identity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | “Pagoda Bone” refers to a unique method for creating deity status. First, bamboo strips were used to construct the framework of the deity, and then a wooden head of the deity was mounted on top. The entire Pagoda Bone structure is hollow, which allows a person to wear and operate it from within. During deity parade activities, Pagoda Bone statues typically represent the attendants or subordinates of the main deity, often with a relatively lower status. |

References

- Abusaidi, M. Saleh. 2013. Dreams as the Gateway to the Deity: (Based on Thousands of the Author’s Own Dreams). Bloomington: iUniverse. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi, Hiroshi. 2020. Islands of Eight Million Smiles: Idol Performance and Symbolic Production in Contemporary Japan. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Baidu. 2024. The Great Prince Huaguang Accepted the QQ Candy I Gave. Available online: https://mbd.baidu.com/newspage/data/dtlandingsuper?nid=dt_5342744287039126391 (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Barrett, Tim. H. 2022. A revolutionary afterlife: The construction of a history of Chinese atheism. In Studies of China and Chineseness Since the Cultural Revolution. Reinterpreting Ideologies and Ideological Reinterpretations. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, vol. 1, pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Daniel. 2008. The virtual ideal: Virtual idols, cute technology and unclean biology. Continuum 22: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullivant, Stephen, Miguel Farias, Jonathan Lanman, and Lois Lee. 2019. Understanding Unbelief: Atheists and Agnostics Around the World. Available online: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/78815/ (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Louise Connelly. 2020. Religion and digital media: Studying materiality in digital religion. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Religion and Materiality. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 471–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Selina Ching, and Graeme Lang. 2011. Temples as enterprises. In Religion in Contemporary China: Revitalization and Innovation. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 133–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, Adam Yuet. 2011. Introduction: Revitalizing and innovating religious traditions in contemporary China. In Religion in Contemporary China. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, Adam Yuet. 2020. Religion and social change in reform-era China. In Routledge Handbook of Chinese Culture and Society. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 411–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, Adam Yuet. 2021. Ritual Terroir. The generation of site-specific vitality. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 193: 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlan, Claudio. 2015. La «Patchwork Religion» in prospettiva storica. Wovoka e la «Ghost Dance» del 1890. Annali di Studi Religiosi 16: 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. London: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve, Gregory Price. 2013. Religion. In Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Edited by Heidi A. Campbell. London: Routledge, pp. 104–18. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Ming, and Yan Yang. 2017. Expansion of public space: Unexpected consequences of conducting folk traditional rituals—An analysis of the “Pageant on Immortals” practice in Fugang Village. Qinghai Journal of Ethnology 28: 202–6. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Panpan. 2019. How to Mobilize the 500 Million+ Fan Army? Available online: https://www.inewsweek.cn/observe/2019-07-19/6416.shtml (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Han, Xiao. 2022. Digital merit: A case study of a Chinese Buddhist meditation group on WeChat during the early outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Journal of Media and Religion 21: 175–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 2000. New age religion and secularization. Numen 47: 288–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Xiulei, and Xiaojian Huang. 2012. The inheritance and development of the Parade Culture: An analysis based on Johor Bahru and Chaoshan Areas. Overseas Chinese Journal of Bagui 4: 34, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Luo, and Mingde Li. 2021. Representation, inter-construction, and production: Feminist theory and practice in Chinese urban cinema. Modern Communication Journal of Communication University of China 43: 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Iskra, Anna. 2022. Navigating the Owl’s gaze: The Chinese body-mind-spirit milieu and circulations of New Age teachings in the Sinosphere. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 25: 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Jie. 2015. Gender Factors: An Examination of the Feminization of Guanyin in Central Tang Dynasty China. Journal of Guangdong University of Technology 36: 1–8+81. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Laurel, Vũ Thị Thanh Tâm, and Nguyễn Thị Thu Hu’o’ng. 2010. Beautiful and efficacious statues: Magic, commodities, agency and the production of sacred objects in popular religion in Viet Nam. Material Religion 6: 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Feng, and Yulin Zheng. 2023. Handmade craft of the “Heavenly Holy Generals” under the cultural ecology of the wandering god ceremony—Taking the handmade technique of “Pagoda Bone”, large hollow bamboo bone statues, of Fuzhou. Journal of Inner Mongolia Arts University 20: 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Weiping. 2008. Conceptualizing gods through statues: A Study of personification and localization in Taiwan. Comparative Studies in Society and History 50: 454–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, Yating, and Yun Li. 2023. ‘Presence’ and ‘going viral’: The reproduction of folk activities on short video platforms—A case study of the ‘Pageant on Immortals’ in Southern Fujian. Western Radio and Television 44: 93–95. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Lin, Zhongxuan, and Yang Liu. 2019. Individual and collective empowerment: Women’s voices in the #MeToo movement in China. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 25: 117–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Chun Jun, and Prince Zhao. 2024. Available online: https://weibo.com/6342535678/O1DdtgoQ7?pagetype=profilefeed (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Liu, Chunguang. 2015. The Spiritual Role in Guanyin’s Image: A Brief Discussion on the Reasons Guanyin as a Female Deity Took Root in China. Modern Communication 8: 49. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Guoliang, Xinyi Huang, and Yinghan Li. 2024. Modernization and inheritance of folk beliefs in the digital age: A case study in the southeastern coastal areas of China. Religions 15: 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Hanbo. 2020. Symbolic empowerment, anxiety consumption, and cultural shaping: Daily superstition as a youth subculture. Chinese Youth Studies 1: 105–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Shudian. 2005. The Grand View of Chinese Deities. Taipei: National Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Miczek, Nadja. 2013. ‘Go online! Said my Guardian angel’ the Internet as platform of religious negotiation. In Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Edited by Heidi A. Campbell. London: Routledge, pp. 215–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, Patrick B. 1971. The relationship of legend and folk belief. The Journal of American Folklore 84: 406–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NetEase. 2024. Unveiling the Origins of Fujian’s Pageant on Immortals and the Images of the Immortal Generals: A Sensory Spectacle That Will Astonish You! Available online: https://www.163.com/dy/article/IPK1MS400553A1ZO.html (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Overmyer, Daniel L. 2001. From “Feudal Superstition” to “popular beliefs”: New directions in mainland Chinese studies of Chinese popular religion. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 12: 103–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratings and Reviews. 2024. Why Is Fujian’s Pageant on Immortals so Popular, and What Exactly Are the Younger Generation Supporting When They “Support the Immortal Generals”? Available online: https://hot.dzwww.com/w_qUYT?ipage=3 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Reinis, Sara, and Corrina Laughlin. 2025. “GOD IS MY SPONSORED AD!! MY ALGORITHM!”: The spiritual algorithmic imaginary and Christian TikTok. New Media & Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, Meir, and Robert P. Weller. 1996. Introduction: Gods and society in China. In Unruly Gods. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Siuda, Piotr. 2021. Mapping digital religion: Exploring the need for new typologies. Religions 12: 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohu. 2024. Fujian’s Pageant on Immortals Has Gone Through the Roof, with Five Major Princes Going Viral—Who Are These Five Princes? Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/759881214_120172967 (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Stefania Travagnin, Stefania, ed. 2016. Religion and Media in China: Insights and Case Studies from the Mainland, Taiwan and Hong Kong. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Valussi, Elena. 2020. Men built religion, and women made it superstitious: Gender and superstition. Republican China Journal of Chinese Religions 48: 87–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Deer Video. 2024. Sculptor Responds: The Zhao Prince Statue Draws Inspiration from Chinese Animated Characters. Available online: https://weibo.com/7575030448/O1VojuAJb?pagetype=like (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Wingia. 2015. Losing Our Religion? Two-Thirds of People Still Claim to be Religious. Available online: https://www.afternic.com/forsale/wingia.com?utm_source=TDFS_DASLNC&utm_medium=parkedpages&utm_campaign=x_corp_tdfs-daslnc_base&traffic_type=TDFS_DASLNC&traffic_id=daslnc (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Wu, Jun, and Bo Cheng. 2024. Socialist feminism: The new development of contemporary Chinese feminist film criticism. Journal of Shanghai University Social Sciences Edition 41: 52–63. Available online: https://www.jsus.shu.edu.cn/EN/Y2024/V41/I5/52 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Xu, Aymeric. 2024. Typologies of secularism in China: Religion, superstition, and secularization. Comparative Studies in Society and History 66: 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Shengju, and Heidi A. Campbell. 2018. Surveying digital religion in China: Characteristics of religion on the Internet in Mainland China. The Communication Review 21: 253–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Lihui. 2014. Mythicism in contemporary Chinese electronic media. Journal of Yunnan Normal University Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition 46: 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- You, Zhichun, and Yueying Zhao. 2024. Introverts or extroverts?: Analysis and reflection on the youth ‘MBTI Craze’ phenomenon. Chinese Youth Studies 7: 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Xiangdou. 2001. A Journey to the South. Haikou: Hainan Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Yelu. 2023. Soundscape construction of urban folk belief rituals: A case study of the “Pageant on Immortals” in Fuzhou. Journal of Jishou University Social Sciences Edition 44: 142–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yanshuang. 2017. Digital religion in China: A comparative perspective on Buddhism and Christianity’s online publics in Sina Weibo. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 6: 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Zongyi. 2021. Infrastructuralization of Tik Tok: Transformation, power relationships, and platformization of video entertainment in China. Media, Culture & Society 43: 219–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, Ji. 2015. Secularization without secularism: The political-religious configuration of post-1989 China. In Atheist Secularism and Its Discontents: A Comparative Study of Religion and Communism in Eurasia. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 92–111. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).