2. The Concept of Authority from Selected Literature on the Subject

When trying to examine how the category of authority is understood today, one can come across statements that it refers to someone: “someone who delights with his or her personality”, “is able to captivate with his or her interests”, “amazes”, “attracts”, and thus “one wants to imitate him or her”. Therefore, in this keyword, one can distinguish three meaningful parts: subject, object and field. The idea here is that an authority is some person (subject) for someone else (object) in some area of activity, or action (domain) (

Bochenski 1993). Thus, this formulation points to a person possessing a peculiar and inbred set of personality traits, manifested in particular competences, through which he influences and shapes attitudes and beliefs in other individuals or groups (

Chlewiński and Majdański 1973). Such a subjective-personal authority, however, should be distinguished from a subjective-institutional one created as a result of a broad socio-institutional interaction, often linked to some sacred book or set of truths or legal acts, “which this institutional authority subjects to appropriate reinterpretations and revisions” (

Goćkowski 1998). This could be, for example, the Bible or a set of legal codes in the case of an official.

The most common use of the term authority is to refer to some particular person who is:

- (a)

a guide who is usually a teacher, lecturer or trainer;

- (b)

an expert (professional)—these used to be shamans, and in modern times engineers, technologists;

- (c)

a discoverer of truth who reveals it in a prophetic, philosophical or ethical space;

- (d)

a classicist or avant-gardist, pointing out paths hitherto pursued or setting new trends;

- (e)

a superior, where the relationship of subordination of others to him is due to his charisma or his recognition as a leader or superior;

- (f)

a wise man who deserves the name by virtue of knowing life and its realities perfectly well, together with its various problems of existence.

In the above examples, individuals have authority by virtue of their qualities, by virtue of who they are and how they manifest their existence in ways that are not only theoretical but also in their practical actions towards others.

The institutional dimension of authority, in turn, arises immanently from its official character. From it alone, it follows that a given administrative, legal or governmental unit is acceptable to its external environment. It is worth noting, however, that the emerging prestige of these entities is something ‘innate’. This is in contrast to the situation where true “authority is not an immanent characteristic of its bearer, but something that is bestowed on or taken away from him in the process of social interaction” (

Szacki 1980).

The phenomenon of authority has been known since the Middle Ages. Originally, it involved the recognition of the seriousness of some group or institution, e.g., cultural customs, the opinion of elders, the faith of fathers, etc. This approach changed with the emergence and development of science. It was then that two trends emerged: the rhetorical-philosophical and the legal-social (

Wroczyński 2000). In the first, the views and writings of well-known authors with significant social impact were recognised. In this current, all kinds of personal testimonies, accepted as expressions of truth, were also recognised. Particularly important were the truths of faith taken as the highest revelation of God (Christianity) (“Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation” (

Second Vatican Council 1968)). In this context, there were times when the views of pagan scholars who did not refer to Revelation in their statements were questioned. However, a sizable body of Christian thinkers accepted their writings by pointing to the so-called authority of natural reason, which was supposed to be a participation in divine authority (St Augustine).

The Middle Ages revealed a continuation of this approach to scientific knowledge, after all, acknowledging the primacy of faith over reason (

Fides quaerens intellectum—Faith seeking understanding St Anselm of Canterbury (

Anselm of Canterbury 1992)). Consequently, recourse was made to the authority of ancient writers (especially Aristotle (

Reale 1996)) to underpin theological rationale (St Thomas Aquinas (

Hienzmann 1999)). The growing fideistic current at the end of scholasticism (W. Ockham, J. Gerson (

Kamiński 1985–1986)), however, denied this approach fearing too much influence of speculative reason in theology.

Modernity rejected the previous approach to authority, introducing in its place the historical-philological method, in which the study of sources was important and even the personal opinions of recognised scholars were accepted. A place for authority remained only in the translation of Scripture and the explanation of the views of the Church Fathers (Erasmus of Rotterdam (

Swieżawski 2002)). Such activities were particularly evident in the subjectivist as well as fideistic attitudes of the Reformation, but also in anti-rationalism or philosophical scepticism (R. Descartes (

Gilson 1967)). Later also in extreme empiricism (I. Kant (

Comte 1961)), positivism (

Comte 1961) or atheism (

Marx et al. 1984). Unfortunately, the rejection of authority was often illusory, for the views and attitudes of the excluded individuals were often replaced by other new ones. Contemporary ideologies (Marxism, fascism) played a significant role in this demagogic activity.

The aforementioned legal and social current used authority not so much in the aspect of knowing the truth in order to duly conduct deliberations and argue its statements, but above all it was applied in practical actions. This was particularly evident in the context of invoking the authority of government and the judiciary. The legal nature of authority was already evident in the Roman Senate interpreting statutes and judgements, and later in Christianity, it was treated in a similar way in the Bible, where God was portrayed as the Supreme Ruler (

Nikodem 2020).

In the Middle Ages, the above ideas were reflected in the feudal system, where the authority of the secular power (the Emperor) was separated from that of the Church (the Pope). In modern times, the authority of the Church was largely undermined especially in aspects of social and political life. The secularisation of natural law (H. Grotius (

Grotius 2005)) led to the transfer of supreme divine authority to a secular sovereign, who, as a result of the social contract (T. Hobbes (

Hobbes 2005)), would have almost unlimited power on earth. (The well-known maxim is then:

Auctoritas non veritas facit legum—Authority and not truth determines the law (

Kaczorowski 2019)). This would ultimately lead to the foundation of absolute monarchies in the 18th and 19th centuries. The authority of an unlimited ruler completely replaced the earlier authority of God. These tendencies were so strongly promoted that even in the developing pedagogical sciences of the period it was thought that authority in education should be rejected, as it is detrimental to education. It destroys the freedom of the learners and, moreover, makes them submissive, dependent and dependent (

Rousseau 1956). Nowadays these tendencies are no longer so radical, but the dominant liberal ideas do not serve to raise the profile of authority in socio-cultural life.

Bearing in mind the historical conditions of authority, as well as the contemporary rather negative attitude towards it (

Witkowski 2011), one can notice a twofold approach to the analysed phenomenon. Thus, the media studies literature points to actual authority and ascribed or created authority. In the first case, there is a person whose prestige and authority are based on actual achievements or individual qualities. These may include officially awarded and well-known academic titles, achievements in knowledge or technical undertakings, but also championships in sports or prestigious competitions. In this way, such a person does not require any significant advertising campaign or public recommendation. The public is interested in him or her will recognise him or her very well and will be familiar with his or her achievements. Thanks to his or her commitment, knowledge or abilities, such a person has the real possibility of possessing real authority, which can be felt and admired by his or her followers; often even his or her opponents must recognise and respect this. At the same time, it is worth noting that the importance of such persons derives not only from the fact of significant achievements in the professional, cultural or religious field but very often also from their lifestyle, which can serve as a model for other individuals wishing to emulate their ideal (e.g., John Paul II (

Drożdż 2016), Mahatma Gandhi (

Wojtaszek 2006), Mother Teresa of Calcutta (

Allegri and Teresa 2011) etc.).

The second type is ascribed or created authority. This occurs when a person is portrayed as significant, important and exemplary to other individuals, in order to convince them that such a person may be a desirable authority for them. Media publicity makes someone recognisable, and it is this fact that makes him or her a created specialist or expert. In other words: “he is known for being known”, and this proves that he can be an authority. This frightening fact, unfortunately, supposes a real failure of the rank of authorities in public life, as well as their decline and a spreading lack of trust (

Kolenda-Zaleska 2010). This leads to a paradox. On the one hand, the public needs experts to guide people through the meanderings of the myriad information coming from all over the world, explaining and clarifying it; on the other hand, it turns out that those individuals who do so are not necessarily experts in the relevant information space at all. This causes even more frustration among viewers, which consequently leads to a questioning of every potential authority appearing in the media, and ultimately to informational degeneration and extreme distrust of everything that is publicly proclaimed (‘TV lies’).

Authorities appear in various areas of human life. Certainly, those with the greatest significance, but also reference, appear in science. Their division can be referred both to the formation of the human personality structure and to the understanding and explanation of the world. Thus, three fundamental characters will appear (

Goćkowski 1977):

- (a)

The luminary—the coryphaeus—is the person who paves new paths for others and points out distant horizons of behaviour; moreover, to the cognitive activity, he adds at the same time considerable methodological guidance.

- (b)

The leader-captain is already pointing others in the right direction and organising both the materials needed and the groups of people to achieve the goal.

- (c)

The master-teacher, in turn, has a didactic and educational function, teaching at the same time how to properly (according to rules and norms) carry out the tasks undertaken.

To an important extent, a kind of religious authority is linked to the above categories. Due to its complex nature as well as its historical turbulence, it is worth drawing attention to it and distinguishing it from many other types. Basically, this type of authority has similar elements to other authorities in its foundations, so here we will point out its authentic life attitude, its openness (tolerance) to other people, as well as its deeply formed and clearly expressed ethical stance. These qualities are related to certain characteristic manifestations of life, such as a specific personal culture, formed both in the family environment and through many years of life experience. Associated with this will be a positive attitude to people, which could be directly described as a “love of man”. It is here that the elements of religious authority—although in a broader perspective, they should be called personalistic—will gradually begin to emerge. What emerges here is a kind of faith in the other person, in his or her abilities and skills, as well as the trust placed in others. This attitude towards others requires the authority to be open to others, to their life problems and existential pains. He or she must be able to listen patiently, which requires a considerable amount of time, and when speaking, he or she must do so in a way that is prudent and to the point. He must do so with sensitivity and sensitivity to the welfare of the other person, in whom he not only recognises his personal, innate dignity but is also able to affirm it. In this way—and this is often the sine qua non of a proper human existence—everyone must be made aware that it is this dignity which constitutes the unique and inimitable statute of every human being. For everyone is

alteri incommunicabilis—an inaccessible, incommunicable, unique individual (

Wojtyła 1986). From a Christian perspective, faith is both an act of trust and reliance (“I believe in”) and an acceptance of affirmed truths or promises (“I believe that”). Faith is thus a relationship with God (“I believe in”), enabling the formulation of specific content (“I believe that”). Faith involves growing into the measure of the greatness of Jesus Christ and becoming more like Him.

However, religious authority has in its essence another quite significant element, which makes it impossible to treat it in the same way as others. It is a kind of divine stamp. In order to clarify this problem, it is first necessary to draw attention to the previously presented division of authority into subjective-personal and subjective-institutional. The religious dimension of authority can manifest itself in both cases. It is worth noting here that the personal character will appear when a person is chosen by another. It is not possible to impose authority on anyone or force someone to recognise it (and even if such a situation occurred, the person would not be a real, actual authority, but a kind of guardian, manager, or administrator enforcing the desired behaviour in another person). It is slightly different in the case of the authority of an institution. Here, there is its prestige, respect or seriousness, due to the public activities undertaken or the socio-political powers held, but here, too, the final recognition of this authority depends on the individual who comes into contact with it. (It is, after all, common to fail to recognise the policing actions of the police, to question court judgements, or to ignore the findings of local government). Similar reactions are aroused by religious authority as understood, e.g., in the form of a given church—this is particularly evident in Polish conditions in the context of the activities of the Catholic Church. One may even notice a contemporary sharp decline in the seriousness of this authority and far-reaching polemics with it or even its questioning.

This situation is unfortunately quite complex due to historical and social circumstances. In 1870, Vatican Council I proclaimed the dogma of papal infallibility later transmitted in the dogmatic constitution Pastor Aeternus (

Gloria.tv 2014). It speaks of a kind of papal authority but emphasises his statements ex-cathedra—i.e., containing doctrinal teaching—rather than any, a fact that is often ignored in modern times. In other words, papal authority derives from its very bestowal by divine power and is therefore irrevocable. By virtue of their participation in the authority of the Church, the splendour of this authority also flows down to bishops and priests. They, too, are anointed with holy oil and, by virtue of the sacrament, empowered to proclaim and explain God’s Word to their faithful.

Hence, personal religious authority is of a somewhat different nature than secular authority. In addition to the individual qualities mentioned above, resulting from wisdom, an unusual personality or exceptional talent, there is also a divine charisma, conferred, as it were, ex officio by the Holy Spirit. It must be remembered, however, that this essentially concerns matters of faith and morals and does not encompass every possible sphere of human activity. Hence, a situation may arise where an individual, while rejecting personal authority, nevertheless retains institutional authority—precisely because of its religious character. In other words, religious authority is valid because it finds its foundation in the very majesty of God. The concept of authority, like many descriptions associated with Church teachings, became part of media content as a consequence of the emergence of mass communication. Traditional media tools, including publishing market products, enabled the dissemination of religious content. Initially, such content was meticulously controlled for accuracy in dissemination and interpretation. This was achieved through Church-supervised publications and careful distribution of issued materials. The pluralism of media, especially the development of new media tools, has enabled almost unlimited interpretations of religious texts, often diverging significantly from their accurate citation. The commercialization of religion has been directed toward profit-making rather than the dissemination of values crucial to the proper structure of society.

The concept of authority in the media has accompanied media transmissions since their inception, particularly during periods when they were associated with specific social groups targeted by communication. This was especially evident in periodicals serving political purposes. The authority of leaders strengthened the integration of individuals united by a specific idea and the figure of a politician. To this day, the media comment in diverse, often controversial ways, on the behavior of political, religious, or other influential figures whose authority and ethical stance are meant to be benchmarks for civilizational development, human rights, or role models in fields such as sports, science, or business. Media transmissions can bring down long-held authorities by journalists’ detailed analyses of their lives and mistakes. Authorities are devalued by the differing interests of their opponents and frequent manipulations on social platforms. Authorities are undermined by the media for economic and political interests. Religious authorities, in particular, are devalued by entities for whom the Church and its religion are obstacles to achieving their own goals based on greed and the desire to control people.

The concept of religious authority in media transmissions, despite its societal value and necessity in social life, is primarily present in Catholic media, especially those driven by the Church institution. General media transmissions mainly focus on crisis phenomena within the Church, where the concept of authority in the Church hierarchy is becoming increasingly ambivalent. In the context of the pursuit of sensationalism, traditional understandings of authority are rarely featured. They are mainly found in specialised, academic texts disseminated via media. The Church’s crises, fueled by biased media transmissions and the Church’s inability to manage crisis situations effectively, increasingly lead to a turning away of believers—not so much from faith itself but mainly from the Church as an institution. This phenomenon is compounded by the influence of affluence, which contrasts with communities in poorer countries where the number of Catholics is growing. Mature media transmissions identifiable in specialist contexts, however, do not permeate the mass audience. It is essential to note the presence of transmissions influenced by Catholic influencers and the way they negotiate the idea of religious authority in contemporary society. Influential religious influencers have primarily used a relatable, friendly, and informal appearance to negotiate visual authority, contrasting with the rigid, more distant approach of traditional religious figures (

Febrian 2024). Given that religion is a crucial factor influencing how American consumers spend time and money, American researchers analyzed 20,068 Facebook posts, 20,517 tweets, and 13,857 Instagram posts to determine their impact on engagement. “In multiple studies, key findings indicate that religious signals increase engagement, while promotional signals decrease it across various platforms. The impact of social media cues, such as hashtags and mentions, varies by platform” (

Myers et al. 2023). An interesting study explored how individuals using online and social media disrupt the Roman Catholic Church’s (Church) exercise of universal moral authority in a globalised world (

Hine 2023). The analysis showed why the use of modern technologies has become a crucial element for maintaining power and the ability to exercise universal moral authority. It demonstrated how, over centuries, the Church accessed technologies that enabled the effective transmission of Church teachings through a hierarchical, centralised, one-way communication process worldwide. In early online religion studies, the issue of authority became a focus, particularly in how traditional religious authorities can be challenged by online religious activity (

Campbell 2010). Researchers of religion and the Internet, initially focusing on descriptive issues, identifying, and defining online religious practices (

Campbell 2011), are expanding their research scope. They point out the existence of relational aspects of authority, where digital media authority is created and maintained through dynamic interaction (

Lövheim and Lundmark 2019). A key aspect of this form of authority, therefore, is the enactment of certain values that generate trust, respect, and confidence among a specific audience. The referenced authors also identify the presence of interpretative authority based on consensus, shaped in public discourse on religious topics among the participating audience (

Clark 2012).

In light of these examples, the article’s authors attempted to identify the concept of authority among young Poles. The researchers were aware that Generation Z navigates the media technology landscape proficiently, spending many hours daily on social media and being influenced by the content they encounter. In this context, as social media becomes a global communication platform, Church leaders and members cannot remain passive regarding the need to study the significant issues of influence. The advantages and disadvantages of social media and their capacity for interpersonal communication must be assessed (

Lam 2023).

3. Authority in the Light of Own Research

The research process carried out was preceded by an analysis of selected literature to illuminate the theoretical underpinnings of the issue. The adopted research method was interviews, using survey techniques with an electronic questionnaire as a tool. The chosen research method was quantitative. A minimum of 500 survey responses was set as the goal, considered optimal for regional studies and studies in selected respondent segments involving specific social groups. The primary research question was: What characteristics should an authority figure possess? These characteristics should align with the common understanding of ethics. The study’s interpretation of its results referred to the understanding of authority as defined by Church teachings. To what extent has the traditional understanding of authority among Generation Z remained relevant in the face of the influences exerted on this social group by media tools, especially new media? This last topic was particularly intriguing, as Generation Z is often regarded as a generation where traditional values fade under the influence of media transmissions. It is essential to view the results with the awareness that the Church influences its community by building its messages on traditional values. The study results show that while Polish society, including Generation Z, stands out among European countries with a high percentage of people engaging in religious practices, observed trends and the dominance of attitudes contrary to Church teachings, such as the permissibility of abortion, euthanasia, divorce, contraceptive use, and other behaviors inconsistent with Catholic teachings, are on the rise (

Polok and Szromek 2024).

The survey method adopted by the researchers allowed data to be obtained by asking questions. For this purpose, a specially prepared questionnaire, an electronic survey, was developed and addressed to university students. This group was chosen because of the complexity of how their views are influenced and shaped by content formed and transmitted via the Internet. Indeed, without the influence of parents and teachers shaping young people’s views to date, and consequently without their influence on attitudes that build social relationships. More than 500 completed questionnaires were obtained, selected results of which will be presented below. A total of 91.4 percent were responses from full-time students and 8.6 percent were responses from part-time students. A total of 91.9 percent were first-degree students surveyed, 7.9 percent were second-degree students and 0.2 were doctoral students. 56.3 percent were female and 43.7 were male. Among the respondents, 91.2 percent were aged between 18–23 years, 5.8 percent were aged 24–29 years and 0.7 percent were aged 30–34 years or older. The universities from which the respondents were recruited were dominated by the University of Economics and the University of Silesia in Katowice, followed by Jagiellonian University in Kraków, UKSW in Warsaw and others.

The following thematic categories were noted as a result of the analysis of the surveys, taking into account the keywords that were most prominent:

Person as authority—answers that mention a particular person or type of person as an authority. This could be publicly known people, authorities in science, culture etc.

Role model—responses focusing on the idea of an authority figure as a role model, a person who sets standards or values that others want to emulate.

Traits and principles—responses that describe authority in terms of specific character traits, and ethical or moral principles that make a person considered an authority.

Influence and relevance—responses relating to the impact that authority has on others, its ability to guide, inspire or influence the decisions and behaviour of others.

Relationships and interactions—responses that talk about authority in the context of human relationships, interactions and how people respond to authority.

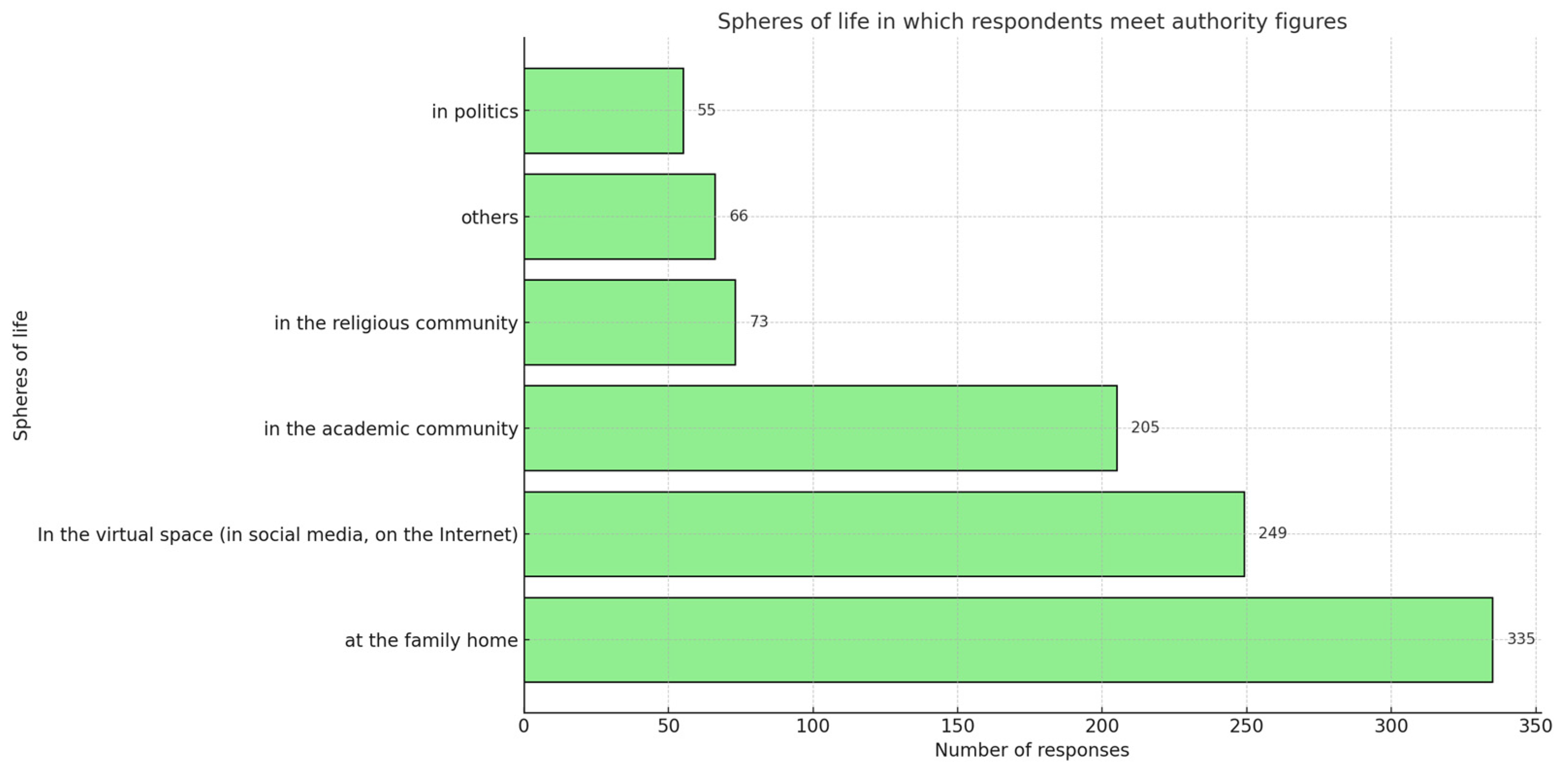

When asked in which spheres of life the respondents meet authorities, the dominant number of answers indicated the family home (355 answers), followed by the media space (249 answers), then the academic environment (105 answers), and the religious community (23 answers). Other areas were indicated by 66 respondents and authorities related to the political environment by 55. The distribution of responses is presented in

Figure 1.

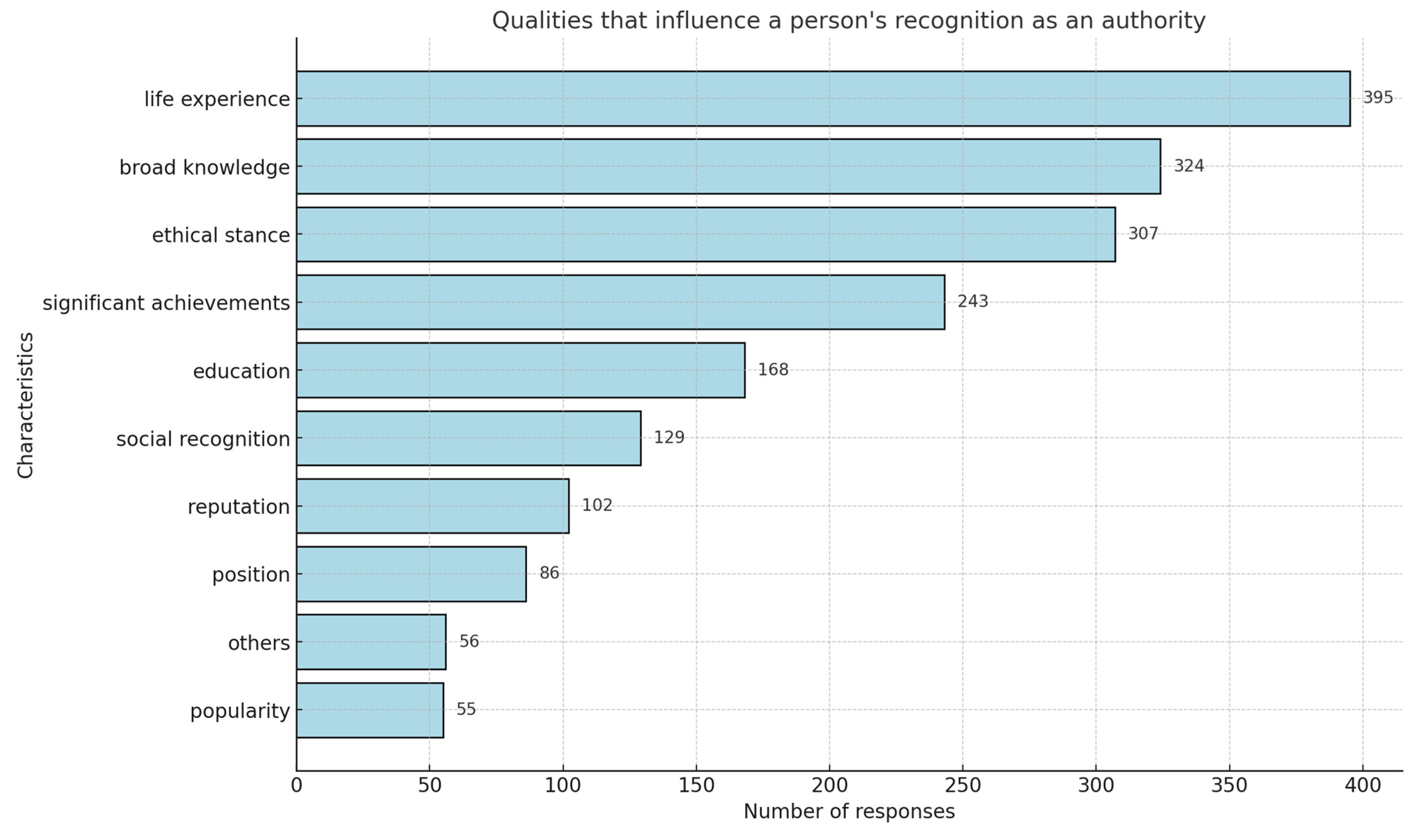

The identification of the areas in which respondents meet authority figures was complemented by the identification of the basic issue contained in the answer to the question: what set of characteristics causes a person to be recognised as an authority? (

Figure 2). The dominant response was that as many as 395 respondents indicated that they should be equipped with life experience. Consistent with this perception is the mention by respondents of the attribute of extensive knowledge (324 indications). An important observation is the indication from 307 responses that authority is the ethical attitude of the person who holds it. A total of 243 people singled out significant achievements and, in order, 183 linked authority with education. A total of 129 people identify it with social recognition and 102 with a good name. Only 86 people indicated a position held and 55 people indicated popularity.

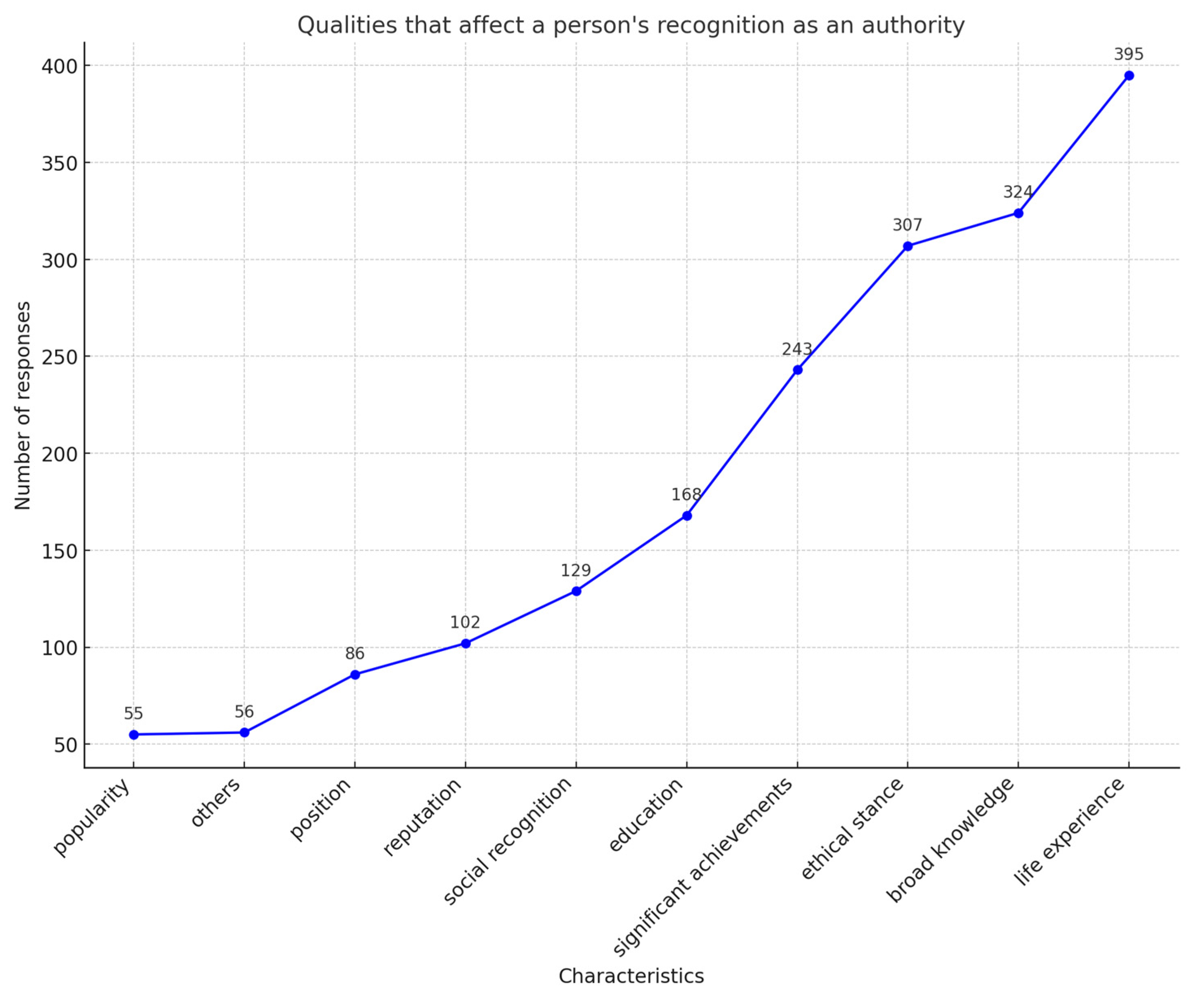

Respondents to the survey were asked to identify the most important qualities they should be equipped with (

Figure 3). Among these, they listed qualities such as honesty, knowledge, intelligence, wisdom or empathy, courage, perseverance, and diligence (

Figure 4).

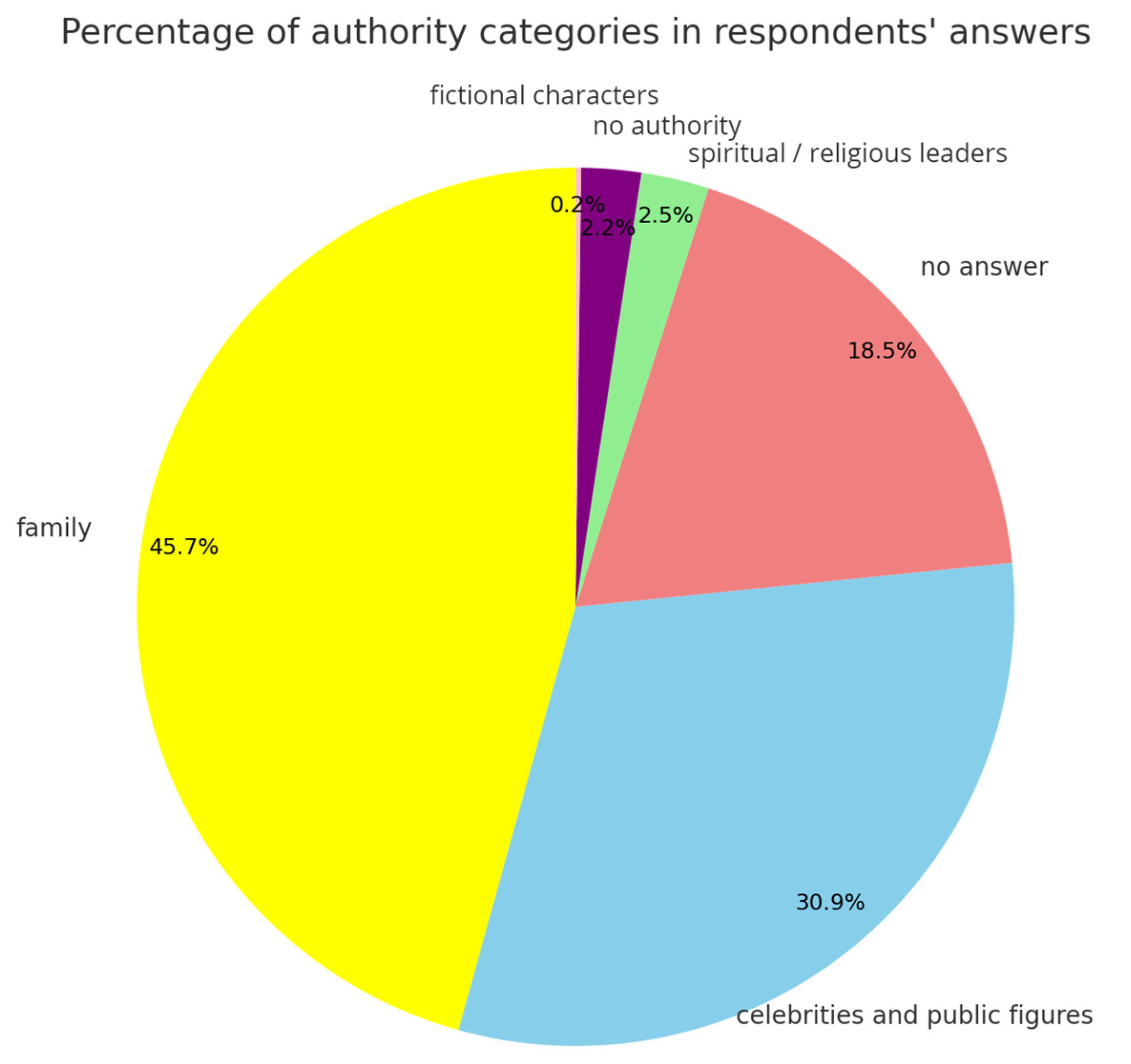

The dominant group recognised as having authority qualities, which should be considered a valuable indication for upbringing processes and building social relations, is the family. Despite many indications from ongoing discussions, this factor is, among others, social networks, are an arena for disseminating the image of celebrities (

Figure 5). The family was indicated by as many as 47.5 percent of the respondents and celebrities by 30.9 percent, which confirms the influence of this social group on the subsequent behaviour of young people. An important indication diagnosing the issue of authority shaping young people’s attitudes is the slight influence of clerical/religious leaders (2.5 percent of responses). This should lead to reflection on the causes of this phenomenon, not only in clerical circles.

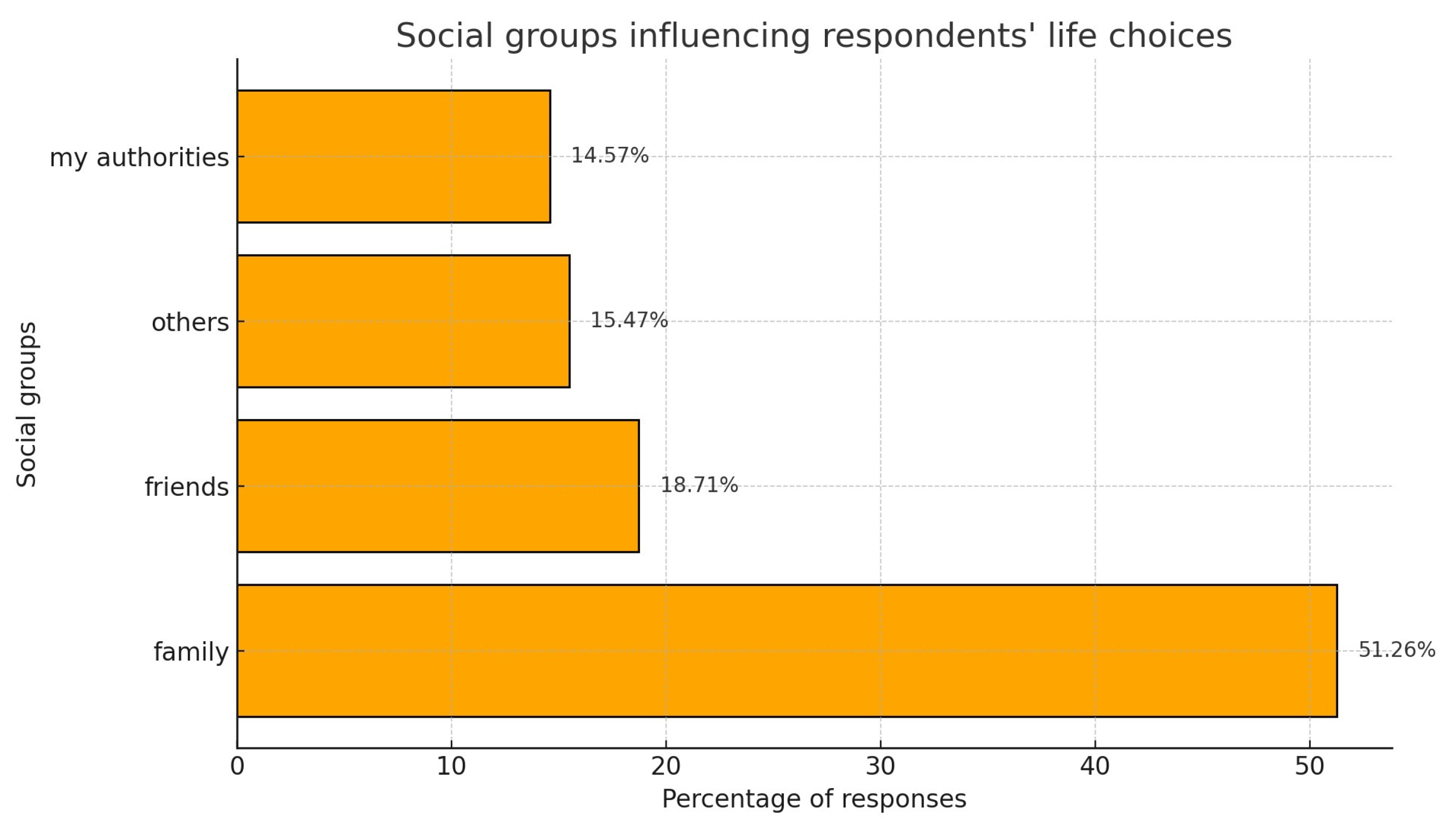

Respondents were also asked to indicate which social groups influence their life choices. Their responses were consistent with the identification of family as the group with the characteristics of authority. Family emerged as the key centre of influence (51.2 percent of responses), followed by friends 18.7 of percent respondents.

The above-quoted conclusions from the questions asked were considered by the authors to be the most important for the purpose of this article (

Figure 6). The analysis of the quoted results indicates that the family plays a key role in young people’s perception of authority. The priority characteristics with which someone considered an authority figure should be equipped are experience, broad knowledge and an ethical attitude. The perception of authority thus follows the traditional description of this concept. It seems that the mediatisation, (according to the respondents’ declarations), to which the young generation is subjected, does not result in changes in their attitudes, despite the fact that the media are the space in which the respondents encounter authorities. An important indication is the respondents’ opinion that authorities are identified by them in the academic environment. An interesting aspect, in relation to the theoretical quotations, is the fact of the low evaluation of persons from the group of religious denominations, despite the fact that as many as 404 persons declared that they are religious persons.

The conducted research among Generation Z students sought to determine the level of trust this generation (students from various Polish universities) places in individual representatives of the Catholic Church, (the Church as an institution). Broader analyses of the research results indicate who, among the institutional representatives of the Church, is seen as trustworthy or in some way authoritative by Generation Z. These research findings, which will be the subject of another publication, indicate a significant level of trust in the Pope, a slightly lower level of trust in parish priests, and a very low level of trust in bishops and the Catholic Church as an institution. The vast majority of those who observe religious rituals and declare adherence to moral principles aligned with Church teachings maintain greater trust in the Church as an institution.