1. Introduction

In the Ottoman Empire, after the conquest of Istanbul by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, the claim to be the protector of Muslims became apparent. Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror established the Sahn Madrasah and invited scholars from the Timurid region to Istanbul, where there was political chaos. Ulema from the region under Timur’s rule, especially from Harāt, accepted Fatih’s invitation (

Giv 2002). In addition to the knowledge transmitted through migration, the Ottoman ulema class was formed with the students who began to grow up in the newly established Sahn Madrasah (

Lekesiz 1991).

The transfer of knowledge to Anatolia began under the Seljuks and Beyliks and continued under the Ottomans. Although the Fatih period was the most prominent, this transfer continued during the sultanates that followed. In addition to the transplanted sciences, renowned names in medicine, astronomy and mathematics migrated to the Ottoman lands for various reasons (

Fazlıoğlu 2014). Another factor contributing to the Ottoman scholarly accumulation was the scholars who travelled to the Timurid state in the Transoxiana region between 1370 and 1507 and to the areas under Mamluk rule in Egypt and Syria between 1250 and 1517. There were many names of people who travelled from the Ottoman lands in order to improve themselves and returned after studying science (

Alan 2003). The scholars who arrived in Istanbul were appointed mudarris and doctors and received high salaries. In addition to the spiritual climate created for Muslims by the conquest of Istanbul, the scientific structure that was to be established could be realised through these migrations (

Ṭāshkubry zādah 2019).

This policy of the state ensured the formation of the ulema class in the regions under its control and created centres of knowledge. The transfer of knowledge and scholars played an important role in the establishment of a centralised structure for the activities carried out. In the period before Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, similar efforts were made in different regions. The fact that the founder of the state, Timur (who established the empire between 1370 and his death in 1405), and especially his grandson Ulugh Beg (who reigned from 1447 to 1449), turned the regions under his rule, especially Samarkand and Herat, into centres of science is also within this scope (

Hodgson 1974). The sultans, sometimes through pressure and sometimes through encouragement and invitation, wanted the ulema to make the cities prosperous (

Yüksel 2017).

With these migrations, the ulema class carried the scientific understanding of the regions in which they lived to the new cities from which they came. Depending on the attitude of the ruler and their own scholarly career, they gained a position within the scholarly caste. These migrations ensured the education of the people in the regions under the sovereignty of the state (

Atcil 2019). In addition to the scholars who emigrated to the city, another important transfer was the arrival of works or copies of works in the city of origin to Istanbul. For example, Musannifak was one of the names with different scholarly personalities who came to Istanbul for various reasons during the reign of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror. Musannifak came to Istanbul at the invitation of Mahmud Pasha, the Vizier of Fatih from 1456 to 1466 and from 1472 to 1474, and brought many of his works to the Ottoman Empire, including the commentary of

al-Masābīh (al-Baghawī’s famous collection of ḥadīth) he had written before (

Çelik 2022).

The examples of scholars who migrated from one region to another and the accumulation of scholarship they brought with them from the past to the present cannot be counted. This study analyses one work that can be used as an example of the intensive migrations during the Fatih period and the scholarly atmosphere in Istanbul. The author Ibrāhīm b. ‘Ali al-Shirwānī, who travelled from Shirwān, dedicated his concise ḥadīth methodology work titled Qawāʻid al-usūl fī ‘ilm ḥādīth al-Rasūl to Sultan Fatih. This book, which has survived as a manuscript, appears to be the first book on ḥadīth methodology written in the Ottoman Empire. There has been no study of the work and its author. This study analyses the originality, characteristics and content of the book.

One of the main questions of research is whether this manuscript book of Shirwānī is an original work or not. This is because, as will be discussed later, Shirwānī prepared his book largely with information taken from the book of

al-Qāyinī (

2018, d. 838/1434-35). However, al-Qāyinī also wrote his book largely on the basis of the information he had taken from al-Ṭībī’s ḥadīth methodology titled

al-Khulāṣah. Therefore, the similarities and differences between the three works will be discussed and the originality of Shirwānī’s book, which was handed down to the Ottomans, will be emphasised. Another question to be answered in this article is whether this book and its author were valued by the Ottoman court and ulema circles, depending on Fatih’s policy of protecting the ulema. Taking into account the Ottoman accumulation of religious sciences and the works written, the impact of this work on the ulema class and the books written will be examined.

First, Shirwānī and his work are introduced and information about the manuscript is given. Then, we will discuss why and where Shirwānī wrote his work. In this way, the effect of migration and the impact of knowledge and scholars on other countries will be determined. Whether the work is original or not will also be determined by the titles, which reveal the content of Shirwānī’s book and the methodology he followed. In order to determine whether a book or a scholar has an impact on the region to which he migrated, the position of Shirwānī and his work will be discussed taking into account the development of the science of ḥadīth in the Ottoman period.

2. Ibrāhīm b. ‘Ali al-Shirwānī and His Book Titled Qawāʻid al-usūl fī ‘ilm ḥādīth al-Rasūl

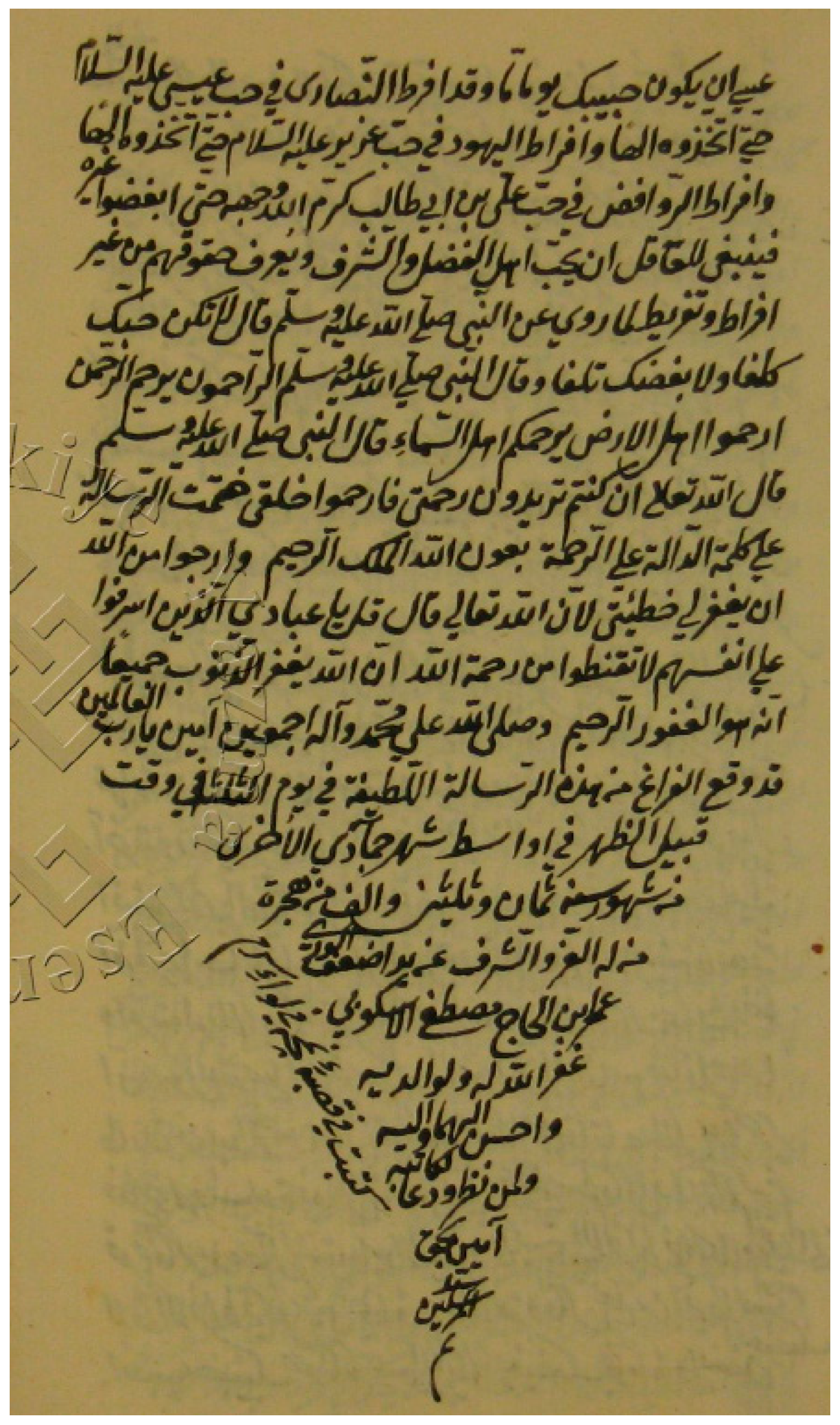

The eighth treatise in a collection of 14 small risalas (24a–229b) in the Bayazıt Collection (no 88) of the Amasya Beyazıt Library is the short Arabic book on the ḥadīth methodology. The other treatises consist of small works of exegesis (tafsīr), theology (ʻaqāʼid), history (tabaqāt) and preaching (mawʻiḍah). At the end of the copy, which is written in taʻlīq calligraphy in 23 lines, measures 208 × 148–165 × 85 mm, and has a brown oak-covered cardboard binding with a small cover (miḳleb) that can be inserted between the pages, with a sun-shaped ornamental motif (şemse). In the manuscript, important topics are entered as headings in the form of maṭlab, and explanatory information in the form of Minhāwāt and notes from other sources are added in the margins.

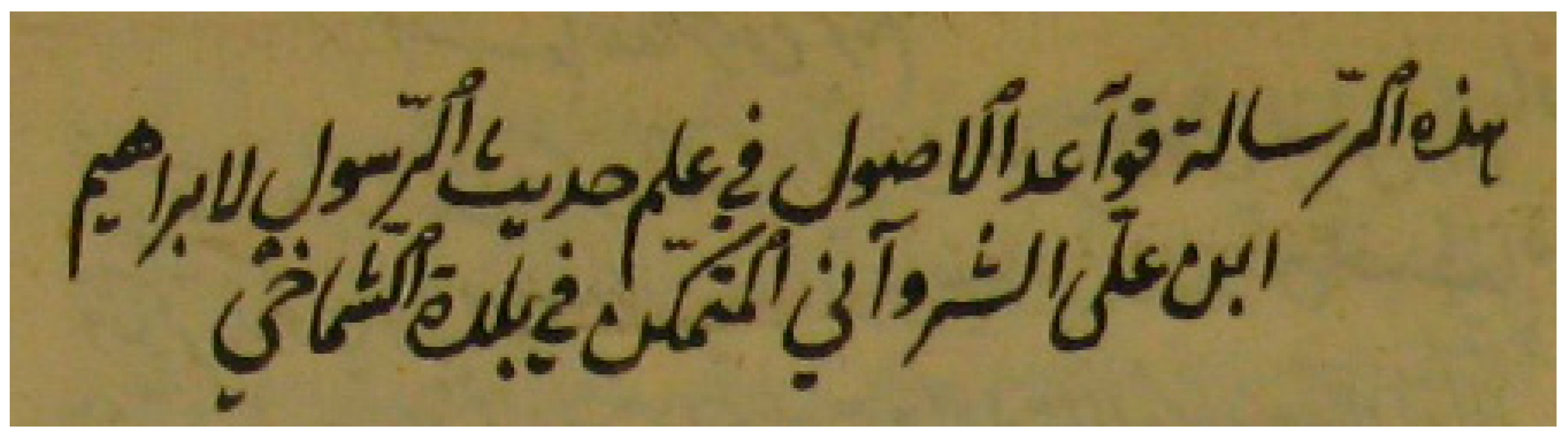

This work of Ibrāhīm b. ʿAlī al-Shirwānī, about whose life we have no information, is recorded in the manuscript with the note (See

Figure 1) ‘This risalah is the work of Ibrāhīm b. ʿAlī al-Shirwānī, who lived in Shemah, titled

Qawāʻid al-usūl fī ‘ilm ḥādīth al-Rasūl (

Shirwānī n.d., 104a) (See

Figure 2). Shemah was one of the important cities of the Shirwānshahs at the time of the author’s migration to the Ottoman Empire. The Shirwānshahs ruled Shirwān (in present-day Azerbaijan) from 861 to 1538, one of the most enduring dynasties in the Islamic world. From 1500, the region came under the rule of Shah Ismail. Fatḥ Allāh al-Shirwānī (d. 891/1486), a contemporary of the author from the same city and town, is credited with introducing the teaching of mathematics, astronomy and geography in Anatolia (

Akpınar 1995). It is known that many names made similar journeys to the Anatolian interior during the period when the author migrated to Istanbul (

Giv 2002). There is a record that it was written by ‘Umar ibn al-Ḥāj Mustafa al-Uskūbī in the town of Nemja in Serm sanjak in the middle of the month of Jumaz al-Ḥājaluhra in the year 1033 AH (121b) (See

Figure 3).

In order to gain a deeper understanding of a particular work, it is essential to consider a number of factors, including the author’s scholarly personality, their affiliation with a particular scholarly milieu, the madhhab they espoused and their other published works. By taking these factors into account, it is possible to gain a more accurate understanding of the work in question. However, there is no available information about Shirwānī other than his hometown and his journey. Nevertheless, the similarity of the work with al-Ṭībī’s al-Khulāṣah and al-Qāyinī’s book, which is based on this work, provides an opportunity to evaluate the work within the framework of these two works and the personalities of their authors. Therefore, this study will examine Qawāʻid al-usūl and then reveal its similarities and differences with the aforementioned works.

3. Place and Reason for Writing

Following the ḥamdalah and ṣalwalah, the author provided his name as it appears on the cover and proceeded to state that the path to eternal happiness is through following the Prophet. He also asserted that the most virtuous of the sciences is ḥadīth. Subsequently, he collated a number of accounts emphasising the significance of narrating ḥadīth. Shirwānī asserts that scholars of his era were preoccupied with superfluous pursuits, thereby divesting themselves of the research and teaching of ḥadīth. For this reason, he intended to collate the regulations pertaining to the science of ḥadīth in a manner that would be comprehensive enough to serve the needs of all students of Islamic sciences. The author states that he benefited from al-Nawawī’s

Riyād al-Sālihīn,

al-Irshād,

al-Taqrīb wa’t-Tayṣīr,

Sharḥ Sahih Muslim and other works (

Shirwānī n.d., pp. 104b–105b). Since he compiled the information that he considered important from the books he mentioned and created a separate classification, we can say at first glance that the present work is a work in the genre of talkhīṣ (abbreviation, summarising the book) (

Durmuş 2020).

In his work Qawāʻid al-usūl fī ‘ilm ḥādīth al-Rasūl, the author dedicates it to Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror and indicates that it was written upon reaching Istanbul, which had been subdued through military means. In this section, the author pays tribute to Sultan Mehmet with prayers and laudatory remarks, characterising him as a just ruler of the Muslim community (105a–105b). Based on these statements, it can be inferred that the author arrived in Anatolia between 1453 and 1481, following the conquest and during the lifetime of Sultan Mehmet. Nevertheless, it is uncertain whether Shirwānī was a favoured figure at the court or whether he was appointed to any position, despite the dedication of the work. While numerous individuals from the Shirwān region are documented as having emigrated during this period, Ibrāhīm b. ʿAlī is conspicuous because of his absence from these accounts.

The assertion that the ulema exhibited a lack of interest in the science of ḥadīth, which is cited as the rationale behind the composition of the work, is also evident in Qutb al-Din al-Iznīqī’s

Talfīqāt al-Masābīh, which is regarded as the inaugural ḥadīth work to be produced during the Ottoman era. Iznīqī notes that scholars of his era exhibited a paucity of interest in both ḥadīth and tafsīr and asserts that a dearth of literature on the science of ḥadīth existed (

Akbaş 2022a).

4. Methodology

Shirwānī structured his work into six principal sections: an introduction (muqaddima), four main parts and a conclusion (khātima). Within the chapters, he addressed a range of topics and engaged in discourse on a variety of subheadings and issues. This approach to the work is not unique to him. This approach is reminiscent of the brief ḥadīth methodology presented by Ibn al-Athir in the introduction to

Jāmi al-Usūl and the treatment of issues by al-Ṭībī in

al-Khulāṣah. Ibn al-Athir divides the text into three sections: mabādī (introduction), maqāṣid (principles) and khātāma (conclusion). In contrast, al-Ṭībī classifies them as muqaddīma (introduction), maqāṣid (objectives) and khātāma (conclusion) (

Demirci 2017). Shirwānī’s book has similarities to al-Ṭībī’s work beyond its methodology, as will be discussed later.

In the introduction, the initial ḥadīths included in the books of ḥadīth are examined, along with the conditions of narrating ḥadīth, the judgement of attributing a lie to the Prophet, the judgement and etiquette of writing ḥadīths, the number of ḥadīths and the etiquette of the ḥadīth meeting. In this section, he also provides information about the scholars who first wrote the ḥadīths, the necessity of offering salāt (prayers of blessing) when the Prophet’s name is mentioned and the prohibition of writing salāt with abbreviations (105b–108a).

The first part deals with the text and related issues (108a–111b). The author analyses ḥadīth by dividing it into three types (authentic ḥadīth–agreeable ḥadīth–weak ḥadīth), and after defining each of them, he explains the concepts of supported ḥadīth; uninterrupted ḥadīth; isnad containing the word “from”; suspended ḥadīth; isolated ḥadīth; interpolated material into ḥadīth; well-known ḥadīth; loose ḥadīth; discontinued ḥadīth; cut-off ḥadīth; interrupted, problematic ḥadīth; anomalous ḥadīth; objectionable, defective ḥadīth; deceitful ḥadīth; disordered (muḍṭarib) ḥadīth; inverted ḥadīth; and fabricated ḥadīth. In this section, he also touches upon the issues of additions of reliable transmititters, text-related appendage, diverse ḥadīth, abrogating and abrogated ḥadīth.

In the second part of his book, which can be considered short, Shirwānī touches upon the issues related to the chain and narrator. The concepts of integrity and accuracy and their defects, ascending chain of transmission, adding to chain, deceit, peers transmitting from one another, the ornate ḥadīth and isnad containing the word “from” are discussed in this section (111b–112b). In the third part of the work, which deals with the ways of conveying and receiving of ḥadīth, the issues of the competence to convey ḥadīth, the ways of conveying ḥadīth, the writing of ḥadīths, the quality of ḥadīth narration and the etiquette of the narrator are discussed (112b–115a).

The last part of the book is devoted to the names of the narrators and the classes of the scholars. Companions; the followers; classes of narrators; names and tags; nicknames; concordant and discordant; non-Arab converts; ambiguous, trustworthy and weak narrators; the homelands of the narrators and the dates of their deaths; the authors of the books of authentic ḥadīth; and the seven retentive scholars who are the owners of the later useful classifications are among the issues covered in this section (115b–117a).

In conclusion, Shirwānī presents a comprehensive overview of the principles that guide the relationship between subjects and their rulers. He emphasises the importance of obedience insofar as it is not forbidden or sinful and outlines the virtues associated with jihad, the pursuit of knowledge, the merits of spending in the pursuit of knowledge, the etiquette of scholarly debate, the role of the qāḍī (judge) and the etiquette associated with this role and the honouring of virtuous individuals (117a–121b). It is noteworthy that in this section, the author makes extensive use of two key sources: Abu Layth al-Samarqandī’s Bustan al-‘ārifīn and Yūsuf b. Ibrāhīm al-Ardabīlī’s al-Anwāru al-Amāl al-Abrār.

The author presents the terms in a systematic structure and provides fundamental explanations without delving excessively into the controversies surrounding them. To illustrate, the author defines the term “objectionable” as “the omission of a narrator who is not reliable or accurate”. In addition to defining the various concepts, the author provides detailed information about the specific types of each concept. He elucidates the concept of interpolated material in ḥadīth as follows: ‘the first form is the inclusion of the words of the narrators, which subsequent narrators adopt as the text of the ḥadīth; the second is when the narrator possesses two distinct texts with two disparate chains of transmission, or alternatively, is aware of a word of the ḥadīth within another chain but narrates both texts with a single chain. The third case is when the narrator hears the ḥadīth from a community with disparate chains and texts and narrates it without addressing the discrepancies between them. All three cases are regarded as equivalent and are therefore prohibited.’ (109b).

In addition to al-Nawawī’s books mentioned in the introduction, he also cites al-Khatīb al-Baghdādī, al-Khattābī, Ibn al-Jawzī, Ibn al-Salāh, Ibn al-Jazarī and others. However, Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad al-Qāyinī, who lived in close contemporaneity with the author, and his work titled Ishrāqāt al-usūl fī ʿilm ḥadīth al-Rasūl, and Shirwānī’s book are almost identical except for the introduction and conclusion.

5. Content

Given the similarities between Shirwānī’s book and al-Qāyinī’s work, it is necessary to consider both works in the analysis of its content. Nevertheless, al-Qāyinī also drew upon al-Ṭībī’s al-Khulāṣah in the preparation of his own work. Accordingly, the pertinent details will be collated, and a comparative analysis of all three works will be conducted.

Al-Qāyinī served as the most famous preacher of his son Shah Rukh, who turned Herat into a centre of knowledge after Timur (

Yüksel 2009). The information found in the analysis of the extant copy of this work written by al-Qāyinī, who was a student of Ibn al-Jazarī, who was with Timur, shows that this work is not original enough and that it was largely prepared by using al-Ṭībī’s

al-Khulāṣah as a source.

Al-Qāyinī states that he compiled this book, which contains the basic topics of ḥadīth that every student of knowledge should know, when he arrived in Nishabur. He states that he benefited from al-Tirmidhi’s

al-Jāmi’i and

al-Ilāl; the ḥadīth books of Hakim al-Nisābūri, al-Khatīb al-Baghdādi, Ibn al-Salāh and Ibn Jāma’a; and various works of al-Nawawī, especially

al-Irshād, al-Ṭībī’s

al-Hulāsa and his teacher Ibn al-Jazarī’s

al-Bidāye. al-Qāyinī clearly states that all but a few of the phrases in his work belong to the scholars (

al-Qāyinī 2018). As can be seen, al-Qāyinī points to a wide range of literature. However, among these works, al-Ṭībī’s book constitutes the backbone of the work. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the author states that the information in the work is mostly compiled from these sources and that he has only a few statements of his own.

We will try to evaluate the content of Shirwānī’s work, which presents a rich content, by showing it together with the works of al-Qāyinī and al-Ṭībī. The subject headings and order in the works are as follows (See

Table 1):

As we can see, the content of the three works is so similar that reading one of them does not make it necessary to read the others. The differences are concentrated in the introduction, the second part and the conclusion. It can be seen that al-Qāyinī and Shirwānī make use of different works in the introduction, especially al-Nawawī’s commentary on Muslim. Both authors compiled the information in the second part of their books under the title of ‘issues related to the chain’ from Ibn Jalma’a’s al-Manhal. The rules of caution mentioned by al-Ṭībī in the conclusion are discussed by al-Qāyinī and Shirwānī in the third part.

A notable divergence between al-Qāyinī and Shirwānī is evident in the concluding sections of the text. In this section, al-Qāyinī presents the significance of studying ḥadīth and provides valuable insights. In contrast, Shirwānī collates information that can be accepted in the aforementioned areas of jurisprudence and advice. The rationale behind the inclusion of these chapters at the end of the book on the methodology of ḥadīth remains unclear, despite the fact that they have been compiled by referencing the works of Abu Layth al-Samarqandī and Yūsuf b. Ibrāhīm al-Ardabīlī. The chapters based on ḥadīths on ruling with justice, obedience to rulers and jihad may be interpreted as evidence that the author was attempting to gain prestige in the court. However, this remains a conjecture, and it is not possible to confirm this hypothesis at this stage.

Upon examination of the texts, it becomes evident that al-Ṭībī addresses both the disputes and the core issues. While al-Qāyinī reproduces al-Ṭībī’s content in a limited number of chapters, he largely avoids addressing secondary issues. In contrast, Shirwānī presents an abridged version of al-Ṭībī’s information in the majority of the work. In comparison to al-Qāyinī, Shirwānī’s more concise treatment of the issues typically excludes information about books written on related concepts or issues. To illustrate, the work of Shirwānī omits information about books on topics such as ambiguous narrators, reliable or weak narrators and brother narrators (116b).

Al-Ṭībī references the well-known definition of authentic ḥadīth as outlined by Ibn al-Salāh, providing a comprehensive analysis of its constituent elements. Subsequently, he addresses the initial works to compile authentic ḥadīths and the number of ḥadīths included in these works. Al-Ṭībī incorporates Ibn al-Salāh’s classification of the most authentic ḥadīths and assesses the veracity of the ḥadīths included in al-Bukhari’s work. In contrast, al-Qāyinī and Shirwānī do not provide any elaboration on the opinions but instead present a concise definition of Ibn al-Salāh, the initial books written by him, the total number of ḥadīths and the classification of the most authentic ḥadīths (

al-Ṭībī 2009;

al-Qāyinī 2018;

Shirwānī n.d.).

Al-Ṭībī presents the concept of agreeable ḥadīth and offers a critical analysis of the various perspectives held by scholars on this matter, highlighting the discrepancies and nuances in their opinions. al-Qāyinī and Shirwānī provide a concise definition of the term “agreeable ḥadīth” and discuss its validity, as well as the manner in which al-Baghawī and al-Tirmidhī employ this term. In this section, al-Qāyinī presents a narrative from his teacher Ibn al-Jazarī, accompanied by the remark, “We heard it from our teacher”. Shirwānī, in contrast, offers a direct quotation from Ibn al-Jazarī, omitting any reference to the source of the information (

al-Ṭībī 2009;

al-Qāyinī 2018;

Shirwānī n.d.).

One example of similar content presented by al-Ṭībī and al-Qāyinī is the definition of inverted ḥadīth (maqlūb). While al-Ṭībī and al-Qāyinī include the account of al-Bukhārī being queried about a hundred ḥadīths with a mixed chain and text upon his arrival in Baghdad, Shirwānī does not reference this information (

al-Ṭībī 2009;

al-Qāyinī 2018;

Shirwānī n.d.).

6. The Book of Shirwānī: An Original or Plagiarised Work?

In light of the sources, methodology and content of Shirwānī’s work, it is challenging to view it as an original contribution to the field. The author may therefore be accused of plagiarism. This is because the work is largely composed of information derived from al-Qāyinī’s book, rather than the sources referenced by the author in the introduction. The author does not present a unique methodology or a content-specific approach to the reader. It would be appropriate to evaluate this issue by taking into account the conditions of the period in question and the method followed by Muslims in composing books.

In the history of ḥadīth, it is a common practice to adopt the information or method presented in a given work or a small number of works and apply it in one’s own work. It may not be necessary to cite a source when a work is merely influencing one’s methodology. Indeed, al-Bukhārī’s system of classifying chapters and books had a significant impact on subsequent sources (

Demirci 2017). The method of directly working on a project without being influenced by external factors is not a practice exemplified by al-Bukhārī. In terms of content, the issue can be readily resolved by the author clearly stating the sources he intends to utilise. Otherwise, it is unethical to make minor alterations to the content of a work and to present the new book as entirely original by omitting certain sections (

al-Sakhāwī 1999). The most illustrative example of this phenomenon is Ibn Abi al-Dam’s book, which he created by transferring material from Ibn al-Salāh’s work without citing his name (

Acar 2022).

It is essential to examine the circumstances surrounding al-Qāyinī, from whom al-Shirwānī significantly drew inspiration, in order to reach a well-founded conclusion on the matter. al-Qāyinī explicitly asserts that only a small proportion of the information presented in the work is original, while the remainder has been collated from the sources he cites. In this regard, it can be stated that his actions were in accordance with the prevailing norms of the time. Furthermore, among the sources he cites is al-Ṭībī’s

al-Ḥulāsa (

al-Qāyinī 2018). However, the fact that the work is largely composed of al-Ṭībī’s work can be considered to be inconsistent with his promise in the introduction.

In conclusion, al-Qāyinī states that he has granted permission for the transmission of this book to all Muslims (

al-Qāyinī 2018). From this perspective, it is unsurprising that Shirwānī draws upon his work. However, it can be considered a problematic approach that Shirwānī focuses on al-Qāyinī’s book instead of the various works he mentions in the introduction. Furthermore, Shirwānī made use of al-Qāyinī’s work without mentioning his name, which is a breach of academic integrity. Al-Qāyinī speaks favourably of his teacher Ibn al-Jazarī in various parts of his work (

al-Qāyinī 2018). However, Shirwānī directly quotes Ibn al-Jazarī’s information, which al-Qāyinī included in his work by samāʻ (audition) from his teacher (

al-Qāyinī 2018;

Shirwānī n.d.). It seems plausible to suggest that Shirwānī was a student of Ibn al-Jazarī and may have received the same information from his teacher. Nevertheless, the absence of any reference to endurance in his work renders this hypothesis implausible.

Had Shirwānī complied with the conditions he set forth in the introduction, his work could have been accepted as a concise methodology for ḥadīth within the framework of talkhīṣ. However, the aforementioned issues pertaining to originality, the transmission of information and the utilisation of sources preclude the possibility of categorising the work as an original contribution by Shirwānī. This raises the question of whether it is possible to classify this work as plagiarism. At this juncture, while the extant evidence permits such an interpretation, additional data regarding other copies of the work and the relationship between Shirwānī and al-Qāyinī are required. It is possible that some situations not found in the copy under consideration may be inferred from other sources. It is possible that Shirwānī was one of al-Qāyinī’s students and that he wrote a copy of Al-Qāyinī’s work and dedicated it to the Padishah upon his arrival in Istanbul. It is similarly conceivable that in the copies that have thus far eluded identification, he asserted that he had created his work with the benefit of al-Qāyinī’s oeuvre, in addition to the aforementioned works. The number of potential scenarios is, in fact, limitless. Nevertheless, irrespective of the aforementioned considerations, these scenarios may ultimately give rise to the emergence of further copies.

In any case, the manuscript under examination displays the hallmarks of a succinct ḥadīth methodology that made its way to Istanbul during the early Ottoman era. It would be beneficial to investigate the influence of this work on Ottoman scholarly life and the status of Shirwānī’s book, as well as the roles of al-Qāyinī and al-Ṭībī, the primary sources for this book, in Ottoman madrasahs.

7. The Impact of the Book on Ottoman Scholarly Life

During the period of Ottoman conquest and the subsequent establishment of madrasahs, an emphasis on the study of fiqh (Islamic law) and kalām (Islamic theology) as a core aspect of education became prominent. The analysis revealed that only seven of the 234 works produced by scholars affiliated with Sahn madrasahs between 1470 and 1730 pertain to ḥadīth. Of these, six are commentaries on ḥadīth (

Unan 2003). Consequently, there is a paucity of substantial works on hadith sciences during the period when Shirwānī came to Istanbul and the subsequent period. The fact that Bukhārī and al-Baghawī’s compilations of ḥadīth were studied in the 15th-century madrasahs also corroborates this assessment (

Baltacı 1976).

When it comes to the Ottoman Empire and especially Istanbul, the scholars who emigrated from different regions and the scholars who travelled to various countries, especially Egypt, and returned to the Ottoman Empire should be mentioned. During the period of Shirwānī’s migration, scholars from a multitude of countries, particularly those hailing from Herat, made their way to Istanbul. Notwithstanding these peregrinations, with regard to the science of ḥadīth, we may speak of the accumulation of scholarship and of books transported as a consequence of journeys to Damascus, Hejaz and Egypt undertaken from the 17th century onwards (

Ayaz 2016).

Prior to the advent of Shirwānī, no known instance of a ḥadīth methodology book had reached the Ottoman Empire through independent composition or transmission. It is thought that Shihāb al-Dīn Sivāsī’s (d. 860/1455) work

Riyādu’l-Azhār, which provides a summary of Ibn al-Salāh’s

Muqaddima and frequently cites al-Khatīb al-Baghdādī’s

al-Jāmi’, represents the first instance of a hadith methodology being compiled in Anatolia (

Ayaz 2014). It can be reasonably argued that, with the exception of this work, which was composed during the Beyliks period and region, Shirwānī is the first author of the first ḥadīth methodology work to reach the Ottoman Empire. After him, in the 16th century, two more ḥadīth methodology works reached Istanbul. Qwam al-Dīn Yusuf b. Hasan al-Husaynī al-Shirāzī (d. 922/1516) from Baghdad and Ibrāhīm b. Muhammad b. Ibrāhīm b. Muhammad al-Khalebī (d. 956/1549) from Egypt came to Istanbul (

Ayaz 2014).

It is of interest to enquire whether Shirwānī’s ḥadīth methodology book, which was compiled in the early period, was received favourably in the madrasah and ulema circles despite its status as the first of its kind. As previously stated, it can be reasonably assumed that this work did not receive a favourable response, particularly in light of the prevailing scientific understanding and orientations during the period of conquest. There is no evidence to suggest that Ottoman madrasahs engaged with the hadith methodology or had any familiarity with the ḥadīth sciences during the 14th to 16th centuries (

Ayaz 2016).

The existence of a copy of Shirwānī’s work in Istanbul is of significant importance for the transmission of knowledge. Nevertheless, the extant evidence indicates that this work had no discernible impact on the study of ḥadīth methodology during the Ottoman period. It is possible to posit that the copy that reached the palace remained there for a period before being transferred to the libraries. Alternatively, it could be argued that the understanding of the period’s ḥadīth science, and in particular the understanding of the writing-teaching follow-up, rendered such a procedural work unnecessary. Furthermore, in the 16th century and subsequent periods, works centred on Ibn al-Salah, particularly within the framework of ḥadīth methodology, are of note. However, the summary (ikhtiṣār) or rearrangement (tehzīb) of his work around Damascus and Cairo are of particular interest. Although Ottoman scholars benefited from al-Ṭībī’s commentary on

al-Mishkāt and his gloss on

al-Kashshāf, they did not make much use of his

al-Khulāṣah. Here, the fact that al-Ṭībī’s work was put at the beginning of his commentary on

al-Mishkāt and al-Jurjānī’s revision of this work under the name of

Mukhtaṣar also had an effect. In addition, we can also mention the effect of al-Ṭībī’s living in Tabriz, which can be considered as a periphery, instead of Damascus–Cairo regions, which are considered as centres in terms of ḥadīth science (

Demirci 2017).

It is evident that the Herat region exerted a considerable influence on the Ottoman humanities, particularly in the fields of mathematics, astronomy and medicine. However, the situation with regard to the science of ḥadīth is worthy of further discussion. It would be erroneous to assume that the corpus of ḥadīth produced in the Ottoman Empire was entirely derived from the Damascus–Qahira region. Indeed, the commentaries on al-Baghawī’s

al-Masābīh, which was extensively commented on by scholars of the Khorasan region during the 7th and 8th centuries, were predominantly composed in Anatolia from the 9th century onwards (

Akbaş 2022b). Consequently, it can be posited that an interest in the methodology of ḥadīth within the Ottoman Empire emerged at a later period, with a particular focus on works originating from Damascus and Cairo.

In examining the impact of the copy that reached Istanbul on the Ottoman Empire, it is notable that there is currently a paucity of information available regarding the activities of Shirwānī and his work. The majority of the sources contain information pertaining to the ulema belonging to the upper echelons of society. While it cannot be definitively stated that Shirwānī was not included in this class at the time, the lack of a biography of him in the sources and the absence of records of his work can be considered evidence that he was not sufficiently appreciated. To this end, it is essential to identify other copies of the work and to evaluate the data on the relationship between al-Ṭībī, al-Qāyinī and Shirwānī in these copies, should any exist. Furthermore, it is essential to locate documentation pertaining to the fate of the work that Shirwānī dedicated to the Sultan and to ascertain whether it was received favourably by the ulema and the palace community. It seems plausible to suggest that the primary reason for these uncertainties is the possibility that the author did not remain in Istanbul but instead migrated elsewhere and did not assume any position. For the time being, our analysis will focus on the copy and the characteristics of the work. As new findings about the book and the author emerge, we will be able to reach a final conclusion about these possibilities.

8. Conclusions

The transfer of knowledge and ulema to the Ottoman Empire was achieved through a combination of migration from disparate regions and the existing accumulation in the lands under its sovereignty. Over time, this transfer of knowledge placed Istanbul in a central position, where ulema were patronised, science was valued, and books were transferred to libraries and madrasas. Consequently, Istanbul, with its structured madrasah system, offered a platform for the cultivation of the ulema class that the Ottoman Empire required, as well as the nurturing of qualified individuals who would contribute to the bureaucracy.

During the reign of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, a considerable number of scholars, possessing a high level of expertise in a range of scientific disciplines, relocated to Istanbul from the Herat–Shirwān region. In addition to their expertise in religious sciences, these individuals were also esteemed for their knowledge of human sciences, particularly in the domains of mathematics, astronomy and medicine. One of the individuals who migrated was Ibrāhīm b. ‘Ali al-Shirwānī. His work, Qawāʻid al-usūl fī ‘ilm ḥādīth al-Rasūl, which he dedicated to Sultan Fatih in Istanbul, where he arrived after the conquest, represents the inaugural ḥadīth methodology work in the Ottoman lands, according to our analysis. It would appear that Shirwānī’s book, which deals with basic issues in a concise manner and does not include discussions, did not attract sufficient interest within the Ottoman scholarly circle, according to the information available. The principal reason for this may be that there was no existing scholarly requirement for a book of this nature at that time.

Shirwānī’s book represents a summary of al-Qāyinī’s work, with the exception of the introduction and conclusion. The former lived in the same period as the latter. In the absence of clarity regarding the scholarly relationship between Shirwānī and al-Qāyinī, it would be premature to conclude that this book constitutes plagiarism. The original of Shirwānī’s book, al-Qāyinī’s work, is also largely based on al-Ṭībī’s al-Khulāṣah, which presents the methodology of ḥadīth. However, in the introduction to his work, al-Qāyinī explicitly references al-Ṭībī and acknowledges the influence of his methodology. In contrast, Shirwānī does not cite al-Qāyinī by name in this enumeration, although he asserts that his own work will draw upon a range of sources.

It is our hope that the findings presented in this analysis, based on the single extant manuscript, will be enhanced with the discovery of additional manuscripts. Nevertheless, this work, which serves as a significant case study in the transfer of knowledge to the early Ottoman period, is valuable in demonstrating the transfer of a book from the Herat and Shirwān region, irrespective of whether it was plagiarised or not. Additionally, it represents a pioneering contribution to the field of ḥadīth methodology.