Interpreting Visuality in the Middle Ages: The Iconographic Paradigm of the Refectory of the Monastery of San Salvador de Oña

Abstract

1. Introduction

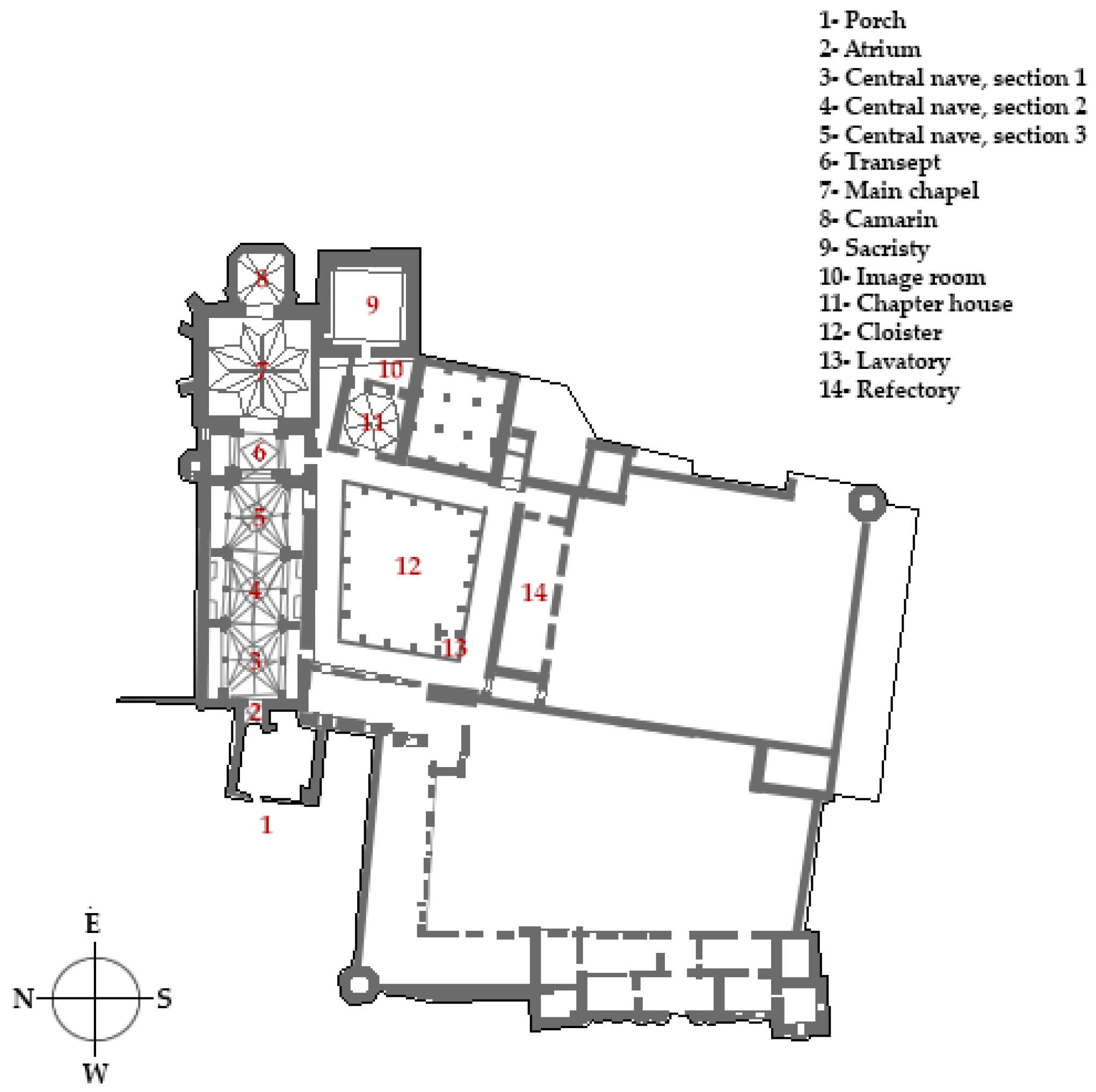

- Phase 1: The period preceding the establishment of the monastery in 1011, during which the site was already in existence. In this period, documentary evidence exists, which pertains to Oña, and is dated 934. This evidence takes the form of a writing by Iby Hayyan, which recounts an assault by Abd-al-Rahman III on the fortifications of this town (Reyes Téllez 2012, p. 37). It can, thus, be postulated that the extant remains of defensive towers are located at the entrance to the church. Of particular note is the tower associated with Samson’s staircase, which served as the access tower and exhibited a distinctive elbow-shaped design characteristic of the Islamic world. This architectural feature afforded the defenders enhanced control over the entrances, thereby providing a strategic advantage against invaders.

- Phase 2: Oñeca Garcés (1011–1014) to St. Trigidia (1014–1030). Oneca Garcés, sister of Count Sancho Garcés and abbess of San Juan de la Hoz, assumed the role of guardian to her niece Tigridia, daughter of the count and abbess of San Salvador de Oña, during the nascent stages of its establishment. In the early years of the enclave, men and women were welcomed under the formula Dei cultores y deo devotas (Reyes Téllez 2012, p. 45), although the exact scope of the profession of both is not specified. During this period, the monastery was established as a duplicate space under the Hispanic rite, with facilities to accommodate this liturgy. Hispanic monasteries were typically composed of two enclosed spaces. The first was an interior, smaller area offering greater protection, which served as the monastic quarters. The second was an exterior space surrounding the garden and orchard. Although there is currently no material evidence from this period, the approaches of architects such as Cambero, in his preliminary studies, can be followed to suggest that the original location of this courtyard and this church would correspond to the cloister and the current church (Cambero Lorenzo 2019, p. 32).

- The third phase of the monastery’s history is characterized by the tenure of Abbot García (1032–1039) and Abbot Pedro Pérez (1259–1271). The reforms of the 12th century are evidenced by documentary sources, which indicate that a portion of the cloister construction was completed around 1141. This indicates that the church and the remainder of the cloister were also completed at this time. The abbot responsible for implementing these reforms was Juan de Castellanos (1137–1160), who, according to the chronicles of the period, was in charge of concluding the construction of the refectory (Zaragoza 1994, p. 562).

- The fourth phase of the monastery’s history is characterized by the tenure of Abbot Pedro García (1272–1287) and Abbot Sancho Díaz (1381–1419). During the period between 1332 and 1360, which corresponds to the reforms of the church, modifications were made to the main chapel. These modifications were carried out by Abbot García (1313–1329) (Zaragoza 1994, p. 564). The walls of the main chapel were widened, thereby enlarging the space and eliminating the Romanesque chancel with three apses. It may be reasonably assumed that the cycle of animalistic capitals of the east transept’s toral closures and the mural of Santa Maria Egipcíaca were also configured during this period. The capitals originally comprised a 360° structure comprising twelve supports, nine of which remain due to the enclosure of the western wall during the mid-10th century. Consequently, it is probable that the work was completed prior to this period, which spans from 1332 to 1360 (Cuesta Sánchez and Pazos-López 2022, p. 60). A traumatic event occurred in the monastery between 1366 and 1367. Troops under the command of the Black Prince, retreating from the civil war between Pedro I and Enrique II, razed the center to the ground and looted a large quantity of items. In order to collect the payment of the debt that Pedro I was unable to pay because of the support of the British troops in the conflict with his half-brother, precious works from the monastery were collected (Herrera Oria 1917, pp. 86–87). During this period, the figure of Abbot Lope Ruiz (1350–1381), who served as royal chaplain to Alfonso XI and Pedro El Justiciero (Pedro I the Cruel), is worthy of particular note. During his tenure, the monastery was sacked by the Black Prince of Wales (Zaragoza 1994, p. 565), after which fortification work commenced with the construction of the wall and Puerta del Cid under Abbot Sancho Díaz (1381–1419).

- Phase 5: the period from Abbot Pedro de Briviesca (1419–1452) to Abbot Juan Manso (1479–1495). This phase encompasses a multitude of remodeling works undertaken between circa 1430 and the conclusion of the century, encompassing both the church and the regular rooms. During the tenure of Pedro de Briviesca and his successor until 1460, the vaults of the central nave, the enclosures of the side chapels, the enclosure of the Santa María Egipcíaca Mural Paintings, and other architectural elements underwent significant modifications. The final phase of decoration of the refectory’s relief involved the painting of the lunettes and repolychroming with the use of gold leaf. This was possibly undertaken in response to the deterioration caused by the sacking of 1367. The period between 1460 and 1470 saw the construction of the doorway and the polychrome atrium or narthex, in addition to the altar choir and the choir loft, the royal and county pantheon, and the access door in walnut and boxwood. This was carried out by Fray Pedro de Loreno in collaboration with Fray Pedro de Valladolid. Additionally, the ribbed vault of the main chapel was constructed, a project undertaken by Fernando Díaz that drew inspiration from Juan de Colonia and his school of thought. It was completed in 1470. As Martín Simón notes, this type of vault is also present in the Cartuja de Miraflores and will serve as an architectural model that will be disseminated throughout the entire peninsular geography during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, as evidenced by buildings such as San Juan. The Royal Chapel of Granada, also known as the Chapel of the Reyes or El Paular, saw significant construction between 1465 and 1470. The most notable documentation from this period pertains to the payment for the works, which was signed by the abbot and the master. Based on these sources, it can be inferred that the vault was completed around 1470 (Martín Martínez De Simón 2012, pp. 639–40).

- Phase 6: from Abbot Andrés Gutiérrez de Cerezo (1495–1503) to Abbot Alonso de Madrid (1506–1512). In 1503, the Romanesque cloister underwent a reformative process with the objective of replacing it with a Gothic cloister designed by Simón de Colonia. This endeavor reached its culmination with the installation of the fountain in 1508 (Martín Martínez De Simón 2012, p. 643). The abbot responsible for initiating this reform was Alonso de Oña y del Castillo (1503–1506), who completed two sections of the cloister, with the remaining two sections completed by Alonso de Madrid (1506–1512). The latter abbot concluded the remodeling process by placing the fountain of Simón de Colonia in front of the refectory (Zaragoza 1994, p. 569).

2. The Space and the Object

2.1. The Refectory

“The piece of the refectory is very old, as it was completed in the year one thousand one hundred and forty-one. It is magnificent and beautiful in a great way, as if made for such a large community; it is forty-eight steps long and thirty-seven feet wide. It has been renovated many times, and today only the walls and a rich and majestic coffered ceiling in the form of an orange vault remain. There is a memory that it was in its beginnings, as it is said that it had a great reputation of having been then one of the most costly and curious works of Castile, truly that the aforementioned coffered ceiling will be understood, because it has a singular and pilgrim assembly and inlay. It is gilded and painted, with interverados and many oil paintings of various saints, and what makes it stand out most is a starry gilded rosette and some large gilded carved pinecones that hang downwards, with the gold as fresh and shiny as if they had just been gilded, being so that they are about seven centuries old. And the memory also says that the seats of the monges were made of very delicate inlaid wood, with their highly polished gilded and painted backs. On the trabiessa table they were more outstanding and of greater refinement, with the abbot’s seat standing out, on the head of which the era in which this work was made was read in an extraordinary way.

IN ERA DECIES CENTENA, BIS QUINQUAGENA SEPTlES DENA, INTER TRINA FACTUM: EST HOC OPUS REGNANTE MPERATORE DOMNO ALDEPHONSO TOLETO, ET PER OMNES HESPERIAS.

Which means: as in the era of one thousand one hundred and seventy-nine this work was made, reigning—in Toledo, and throughout Spain, the emperor Don Alonso; that having reduced the years of Caesar, which are thirty-eight, it was made in the years of Christ our Redeemer, one thousand one hundred and forty-one.

What is certain is that this sumptuous and beautiful piece says what it is and what it has been just by looking at it, as today it appears from the cornice of its famous coffered ceiling on its smooth walls in white Yesso with great capacity, cleanliness and clarity, as it has five arched windows three rods high and about two wide, with their stained glass windows that give it copious light from the south”.

2.2. The Architectural Ensemble as a Key Work of Hispanic Medieval Art

3. Analytical Results and Study Methodology

3.1. Technical and Material Analysis of Calligraphy

3.2. Technical and Material Analyses of the Arches’ Lunettes

4. The Symbolic Transformation of the Refectory: The Transition from the 14th Century to the 15th Century

4.1. The Reign of Pedro I and the Reflection of Islamic Influence: The Imprint on the Artistic Remains of the Onian Refectory

“The chaplain would be one who enjoys ecclesiastical income by reason or title of chaplaincy. [...] would refer to a benefit attributed to a chaplain with specific religious obligations, established in a foundation act that, in general, would not in itself imply a reference to a specific architectural framework -a chapel-, but would make use of pre-existing spaces. In a particular sense, a royal chaplaincy would be characterized by the following parameters:

- -

- -

- -

- -

“However, occasionally in both medieval and modern documentation it is possible to document some references to royal chaplains or chapels that should not be confused with these institutions. In the first place, this denomination must have been applied to certain monks and monasteries linked to the Royal Patronage, in relation to the notion of chapel as “Iglesias de los Monges” [...] Pedro I’s reference to the clerics of the monastery of Oña as “mios capellanes”.

4.2. The Subsequent Adoption of a Dual Iconography: The Last Supper

“I say to you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the Kingdom of God; and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven”.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

| 1 | For those wishing to view detailed, high-quality images of all the rooms and works, the following link will direct you to the relevant information. Monasterio de San Salvador de Oña. Available online: https://www.xn--monasteriodeoa-2nb.com/ (accessed on 16 August 2024). |

| 2 | This difference in level between the original wall construction of the cloister and the later excavation of the reform of 1503 can be seen in the eastern interior wall of the chapter house where the remains of the arcades of the Romanesque cloister are still preserved. |

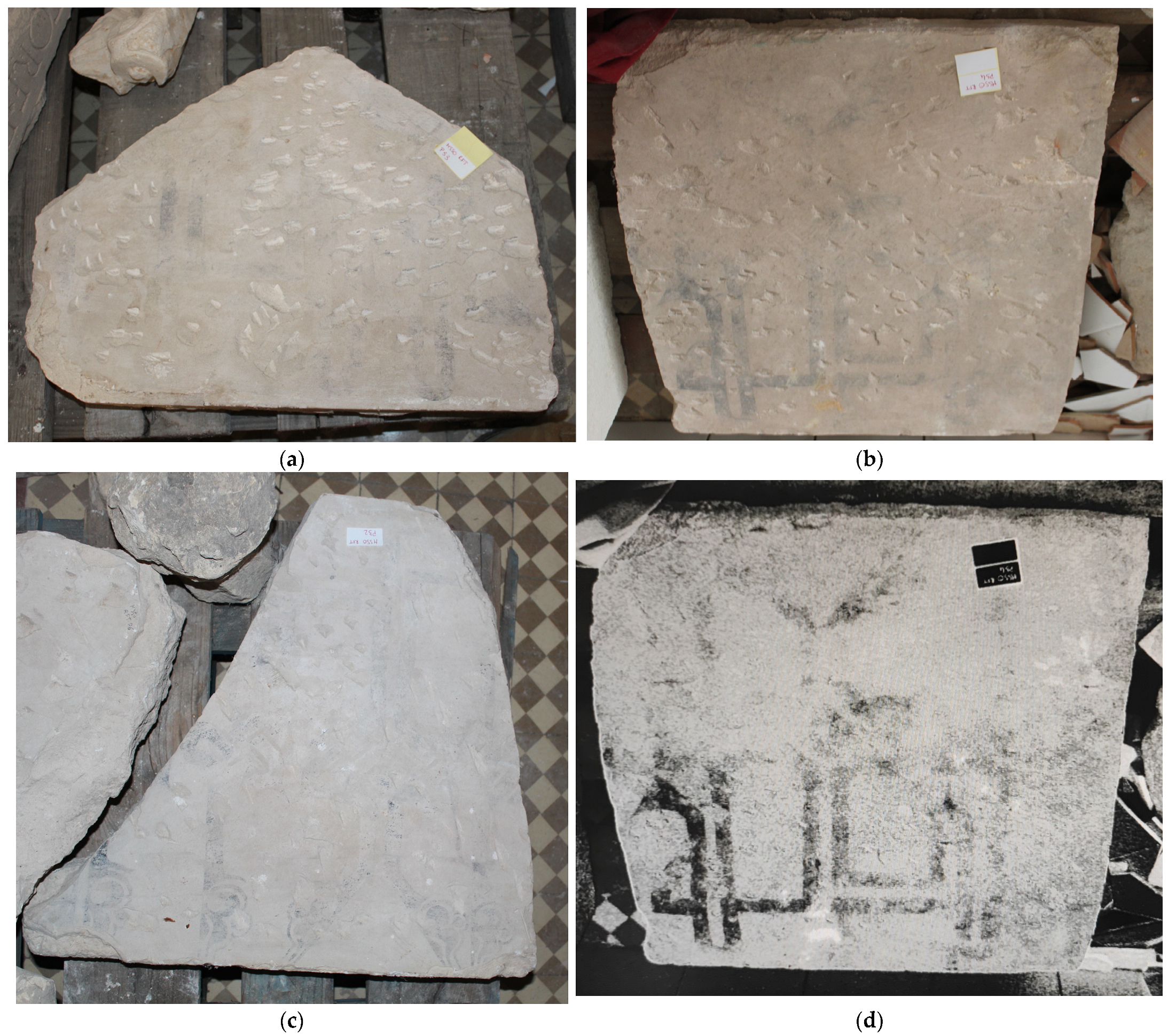

| 3 | The fragment with the carved inscription measures 31.8 cm wide, 9.5 cm high, and 14 cm deep. The plaster plates have a variable structure that remains within 50 cm high and 3 cm thick. They are in a delicate state of conservation, as they show advanced degradation of the black writing lines, as well as damage from vandalism. |

| 4 | The whitewashing of this layer would correspond to the process of walling the piece into the wall. |

| 5 | The lunettes of arches 1, 2, and 5a are smoother and whiter than the lunettes of arches 3, 4, and 5b. We can intuit a polishing, abrasive cleaning or cleaning with unsuitable products on their surface, eliminating a natural or decorative patina that can be seen in the historical photos of the piece in situ. |

| 6 | In their research, Ana García Bueno and her team at the University of Granada identified the use of materials such as copper resinate and tin leafs in the decorative elements of buildings in Granada, including the Palaces of the Alhambra, the Madrasa of Yusuf I, and the Royal Room of Santo Domingo. The application of these materials on wood or plasterwork, following specific techniques or using unique binders typical of the Islamic tradition, has enabled the identification of the characteristic hand of the Nasrid artists in the Royal Alcazars of Seville. For further information on these matters, please refer to the publications by Ana García Bueno and her team on the Reales Alcázares of Seville, the Madrasa of Yusuf I, and the Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo (Granada). |

| 7 | This could be the word alhamdulillah, which translates as “Praise be to Allah”. |

| 8 | The presence in the refectory complex of materials characteristic of the second decorative phase (14th century), including the extensive use of tin or copper resinate, demonstrates a high degree of concordance with the materials and techniques employed in the Nasrid kingdoms of Granada (Cuarto Real de Santo Domingo and Alhambra) and the Reales Alcázares of Seville. This suggests the existence of an artistic connection. |

| 9 | Matthew, 26: 17–26; Mark, 14: 12–22; Luke, 22: 7–14; and John, 23: 21–30. |

| 10 | Artwork 128486. Capital of Notre-Dame de Saint-Basile de Étampes in Essonne, Île-de-France. Available at: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=66C1035D-B37A-4A71-B3D4-AECD3627A5FC (accessed 18 August 2024); Badische Landesbibliothek—Karlsruhe 3378, fol. 56—14th century (center). Available at: https://iconographic.warburg.sas.ac.uk/object-wpc-wid-enug (accessed 18 August 2024). |

| 11 | Psalter. System number: 104789, Ms. M.283 fol. 15r. Morgan Library and Museum. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=B4CF512A-0B60-4AED-AE67-483613C5A879 (accessed on 18 August 2024); Vita Christi. System number: 70125, Ms. M.643, fol.14fol.8r. Morgan Library and Museum. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewImage.action?id=7BB4C18C-7476-4597-9DAD-99DDF0F72851 (accessed on 18 August 2024). |

| 12 | In the Gospel passages of the Last Supper of St. John (23: 21–30) and St. Mark (14: 12–22), the words that Christ indicates to his disciples to discover who will betray him are referenced. In this case, the bread that they will eat is mentioned. In the Gospel of St. John, Christ states, “It is he to whom I give the morsel that I will dip”, while in the Gospel of St. Mark, he says, “dip with me in the dish”. These actions have been reflected in the iconography of the Middle Ages, in which Judas is depicted as focusing on the food, denoting his betrayal, while the rest of the disciples are either attentive to Christ’s words or disturbed by their content. On occasion, Judas has also been depicted with a demon near his head or mouth, representing him as the cause of his action. |

| 13 | Lectionary of Sankt Peter. System number: 76284, Ms.G.44, fol. 80r. Morgan Library. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=B7DE53AD-5CFE-47C1-836C-F91FF28A4AA4 (accessed on 15 August 2024); The Gospel Book of Ivan Alexander. System number: 50741, Ms.Add.39627, fol. 202v. British Library. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=F4600F6D-2542-416E-BBBE-A8DA2EDDB34E (accessed on 15 August 2024). |

| 14 | Sankt Georg de Rhäzüns. System number: 159821. Current location: Graubünden, Switzerland. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=23872D46-088A-4A7D-9121-9FE968914F1C (accessed on 15 August 2024); Speculum Humanae Salvationis. System number: 51205, Ms. 2505, fol. 28v. Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Darmstadt, Hesse, Germany. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=0EBB8893-25B0-4833-BA57-74B3AEC56CCB (accessed on 15 August 2024). |

| 15 | The representation of Judas with a black nimbus is evident in notable works such as the Communion of the Apostles by Fra Angelico in San Marco, Florence, and The Last Supper by the Master of Perea (Masaveu Collection). |

| 16 | Gold is a noble metal that does not oxidize or deteriorate on contact with oxygen or other materials, thereby confirming its durability and stability over time. The only means of weakening the structure of gold and causing its deterioration is to mix it with aqua regia (a mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid in a concentration of 1 to 3 parts by volume), ammonia, or mercury. |

| 17 | Crest of the baldachin of Sant Martí de Tost. Inventory number: MEV 5166. Museu Episcopal de Vic, España. Available on: https://museuartmedieval.cat/es/colleccions/romanico/cresteria-del-baldaquin-de-sant-marti-de-tost-mev-5166 (accessed on 15 August 2024); San Gaggio Altarpiece. System number: 180323. Inventory number: 1108. Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=92D138ED-B505-427C-86B1-A42AEEF7913A (accessed on 15 August 2024); Door of Cathedral of Saint Domnius. System number: 74676. Current location: Split, Croatia. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=937A56EE-458E-45F2-8340-479C746182DB (accessed on 15 August 2024); Portal of Saint-Martin of Bellenaves. System number: 103796. Current location: Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=86BB243A-8CFE-4194-94A4-5D429F778719 (accessed on 15 August 2024). |

| 18 | Huntingfield Psalter. System number: 79575, M.43, fol.22r. Morgan Library and Museum. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=83E807AB-0A56-45AA-8839-EDA2DAA6D7AE (accessed on 15 August 2024); Yolande de Soissons Psalter-Hours. System Number: 1238, M.729, fol. 319v. Morgan Library and Museum. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=7E7F5552-FD25-43ED-8C9D-3C9BD3C39132 (accessed on 15 August 2024); Livre d’images de Madame Marie. System number: 181353, N.Acq.fr.16251, fol. 30v. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=3793561F-0490-4793-823B-89F7998A0A8E (accessed on 15 August 2024); Nuremberg Hours. System number: 56626, Solger 4.4o, fol. 72v. Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=9065E6E2-4CB6-4066-8A31-FC51AC2AEC54 (accessed on 15 August 2024). |

| 19 | Ivory dyptich Last Supper Scenes. System number: 83070. Inventory number: OA 10006. Musée du Louvre. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=43F40064-7433-45FF-9ECD-B16E648B7940 (accessed on 15 August 2024); Ivory diptych with Scenes from the Passion of Christ. System number: hds20240510002. Inventory number: 10360. National Museum of Denmark. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=57C6E298-9520-443C-A5D2-79B5907E40C3 (accessed on 15 August 2024); Diptych with scenes from the Passion of Christ. System number: 184420. Inventory number: 1947.191.199. Ashmolean Museum. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=71F0FFEA-B850-4B1B-B81C-1FCA0CCCBD83 (accessed on 15 August 2024); ivory diptich with Virgin Mary and Christological Scenes. System number: jls20240719004. Inventory number: MK 33. Staatliches Museum Schwerin. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=7F351BCD-1E71-46B1-8533-3AEF03BF7BBD (accessed on 15 August 2024); Ivory diptych. System number: hds20240507001. Inventory number: G54. Thorvaldsens Musuem. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=A5679975-6C37-43F8-9D03-FED6908488B4 (accessed on 15 August 2024); Ivory diptych with Christ Passion Scenes. System number: jls20240109002. Inventory number: ODUT01278. Musée du Petit Palais. Available on: https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=D630C641-D394-4373-98B6-4EE853FA8043 (accessed on 15 August 2024). |

| 20 | An exemplar of this architectural style in Hispanic refectories is the structure located in the monastery of Santa Maria la Real in Palencia. This demonstrates a simplified version of the style, comprising three cantilevered arches inserted in the wall and capitals, without the presence of columns. Available on: https://www.santamarialarealmuseorom.com/es/recorridos/visita-historico-artistica/12#imagenes-1 (Accessed on 20 August 2024). |

| 21 | During the civil war between Pedro I and Enrique II, Pope Urban VI adopted a definitive stance in favor of the Trastamara, thereby elevating his cause to the status of a “crusade” against the infidels of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada and, by extension, against his brother, who was aligned with Muhammad V. |

References

- Almagro Gorbea, Antonio. 2013. Los palacios de Pedro I La arquitectura al servicio del poder. Anales de Historia del Arte 2: 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzalluz, Nemesio. 1950. El Monasterio de Oña: Su Arte y Su Historia. Burgos: Aldecoa. [Google Scholar]

- Cambero Lorenzo, Inés. 2019. Estudio e interpretación arquitectónica: El Monasterio de San Salvador de Oña. Master’s thesis, Valladolid University, Valladolid, Spain. Available online: http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/39149 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Cano Ávila, Pedro, and Aly Tawfik Mohamed Essawi. 2004. Estudio epigráfico-histórico de las inscripciones árabes de las ventanas y portalones del Patio de las Doncellas del Palacio de Pedro I en el Real Alcázar de Sevilla. In Apuntes del Alcázar de Sevilla. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, vol. 5, pp. 53–79. Available online: https://www.alcazarsevilla.org/wp-content/pdfs/APUNTES/apuntes5/estudio.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Cennini, Cennino, Franco Brunello, Licisco Magagnato, and Fernando Olmedo Latorre. 1988. El Libro Del Arte. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani, Settimio. 2000. Pedro. In Diccionario de los Santos, Volumen 2. Edited by Claudio Leonardi, Andrea Riccardi and Gabriella Zarri. Madrid: San Pablo, pp. 1856–64. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Mark. 2001. The Art of All Colours. Mediaeval Recipe Books for Painters and Illuminators. London: Archetype Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Mark. 2011. Mediaeval Painters’ Materials and Techniques. The Montpellier Liber Diversarum Arcium. London: Archetype Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta Sánchez, Ana María, and Ángel Pazos-López. 2022. La taxonomía morfológica en la interpretación iconográfica de los animales fantásticos: el bestiario pétreo de San Salvador de Oña (Burgos). In Las imágenes de los animales fantásticos en la Edad Media. Edited by Ángel Pazos López and Ana María Cuesta Sánchez. Madrid: Trea, pp. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- del Álamo, Juan. 1950. Colección Diplomática de San Salvador de Oña. Madrid: CSIC, vol. 2, pp. 822–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Marcilla, Francisco José. 2020. Clérigos al servicio de las Coronas de León y Castilla. Medievalista 28: 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Martín, Luis Vicente. 2007. Pedro I el Cruel (1350–1369). Gijón: Trea. [Google Scholar]

- Doerner, Max. 1998. Los Materiales de Pintura y Su Empleo en el Arte. Barcelona: Editorial Reverte S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 2008. Las Vías de la Iconografía Cristiana. Madrid: Alianza Forma. [Google Scholar]

- Gumiel Campos, Pablo. 2016. Causas y consecuencias de la maurofilia de Pedro I de Castilla en la arquitectura de los siglos XIV y XV. Anales de Historia del Arte 26: 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Baños, Fernando. 2005. Aportación al Estudio de la Pintura de Estilo Gótico Lineal en Castilla y León: Precisiones Cronológicas y Corpus de Pintura Mural y Sobre Tabla. Madrid: Fundación Universitaria Española, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera Oria, Enrique. 1917. Fray Íñigo de Barreda, Oña y su Real Monasterio. Madrid: Gregorio del Amo. [Google Scholar]

- Illardia Gallego, Magdalena. 2011. Las formas y el mundo románico en el entorno de San Salvador de Oña. In San Salvador de Oña: Mil Años de Historia. Edited by Rafael Sánchez Domingo. Burgos: Fundación Milenario San Salvador de Oña, pp. 538–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kroustallis, Stefanos. 2008a. Diccionario de Materias y Técnicas I. Materias. Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura. Available online: https://www.libreria.cultura.gob.es/libro/diccionario-de-materias-y-tecnicas-i-materias_3134/edicion/ebook-3876/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Kroustallis, Stefanos. 2008b. Diccionario de Materias y Técnicas II. Técnicas. Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura. Available online: https://www.libreria.cultura.gob.es/libro/diccionario-de-materias-y-tecnicas-ii-tecnicas_1890/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Kroustallis, Stefanos. 2012. El color de las palabras: Problemas terminológicos e identificación de los pigmentos artificiales. In Fatto d’Archimia: Los Pigmentos Artificiales en las Técnicas Pictóricas. Edited by Marián del Egido and Stefanos Kroustallis. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deportes, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kroustallis, Stefanos. 2013. The Mappae Clavicula Treatise of the Codex Matritensis 19 and the Transmission of Art Technology in the Middle Ages. In Craft Treatises and Handbooks: The Dissemination of Technical Knowledge in the Middle Ages. Edited by Ricardo Córdoba de la Llave. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de Ayala, Pedro. 1994. Crónica del Rey Don Pedro y del Rey Don Enrique, Su Hermano, Hijos del Rey Don Alfonso Onceno. Edited by Germán Orduña. Buenos Aires: SECRIT, vols. 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- López Martínez, Alba, and Juana Cristina Bernal Navarro. 2020. Revisión hagiográfica del arquetipo iconográfico de la imagen de Judas Iscariote en obras pictóricas de los siglos X al XX. Arché 13–14–15: 129–38. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10251/156580 (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Marquer, Julie. 2011. La figura de Ibn al-Jaṭīb como consejero de Pedro I de Castilla: Entre ficción y realidad. E-Spania: Revue Électronique D’études Hispaniques Médiévales 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquer, Julie. 2012. Epigrafía y poder: El uso de las inscripciones árabes en el proyecto propagandístico de Pedro I de Castilla (1350–1369). E-Spania: Revue Électronique D’études Hispaniques Médiévales 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquer, Julie. 2013. El poder escrito: Problemáticas y significación de las inscripciones árabes de los palacios de Pedro I de Castilla (1350–1369). Anales de Historia del Arte 23: 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martínez De Simón, Elena. 2012. Las reformas del siglo XV en la iglesia del Monasterio de San Salvador de Oña. In Oña. Un Milenio, Actas del Congreso Internacional Sobre el Monasterio de Oña, 1011–2011. Edited by Rafael Sánchez Domingo. Burgos: Fundación Milenario San Salvador de Oña, pp. 634–47. [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield, Mary Philadelphia. 1999. Medieval and Renaissance Treatises on the Arts of Painting. Nueva York: Dover Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Monasterio de San Salvador de Oña. 2024. Available online: https://www.xn--monasteriodeoa-2nb.com/ (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Monzón Pertejo, Elena, and Victoria Bernad López. 2021. La “Última Cena” de Jaume Ferrer como Unción en Betania a partir de los tipos iconográficos y el antagonismo entre Judas y María Magdalena. De Medio Aevo 10: 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales Rincón, David. 2010. La representación religiosa de la monarquía castellano-leonesa: La Capilla Real (1252–1504). Ph.D. thesis, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://docta.ucm.es/bitstreams/f277f0d7-3725-45b9-baac-c12a42fd8065/download (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Oceja Gonzalo, Isabel. 1986. Documentación del Monasterio de San Salvador de Oña (1319–1350). Burgos: Ediciones J.M. Garrido Garrido. [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo Bernal, Santiago. 1987. Una Abadía Castellana en el Siglo XI: San Salvador de Oña (1011–1109). Madrid: Universidad Autónoma. [Google Scholar]

- Pastoureau, Michael. 1996. Couleurs, images, symboles. Études d’histoire et d’anthropologie. Paris: Le Leopard d’Or. [Google Scholar]

- Pastoureau, Michel, and Dominique Simonnet. 2006. Breve Historia de Los Colores. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Camacho, Fray Antonio Manuel. 2012. El proceso constructivo del Monasterio de San Salvador de Oña durante la Edad Moderna y la Contemporánea. In Oña. Un Milenio, Actas del Congreso Internacional Sobre el Monasterio de Oña, 1011–2011. Edited by Rafael Sánchez Domingo. Burgos: Fundación Milenario San Salvador de Oña, pp. 470–95. [Google Scholar]

- Portal, Frédéric, and Francesc Gutiérrez. 1996. El Simbolismo de Los Colores: En La Antigüedad, La Edad Media Y Los Tiempos Modernos. Palma de Mallorca: José J. de Olañeta. [Google Scholar]

- Puerta Vilchez, José Miguel. 2015. Caligramas arquitectónicos e imágenes poéticas en la Alhambra. In Epigrafía Árabe y Arqueología Medieval. Edited by Antonio Malpica Cuello and Bilal Sarr Marroco. Granada: Alhuila S.L., pp. 97–134. [Google Scholar]

- Réau, Louis. 2008. Iconografía del Arte Cristiano. Iconografía de la Biblia. Nuevo Testamento. Barcelona: Ediciones del Serbal. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes Téllez, Francisco. 2012. Los orígenes del Monasterio de San Salvador de Oña. Eremitismo y monasterio dúplica. In Oña. Un milenio, Actas del congreso internacional sobre el Monasterio de Oña, 1011–2011. Edited by Rafael Sánchez Domingo. Burgos: Fundación Milenario San Salvador de Oña, pp. 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz García, Elisa. 1999. El poder de la escritura y la escritura del poder. In Origenes de la monarquía hispánica. Propaganda y leginitmación (CA. 1400–1520). Edited by Juan Manuel Nieto Soria. Madrid: Dykinson, pp. 275–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Souza, Juan Carlos. 2004. Castilla y Al-Ándalus. Arquitecturas aljamiadas y otros grados de asimilación. Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte 16: 17–44. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/1018 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Ruiz Souza, Juan Carlos. 2013. Los espacios palatinos del rey en las cortes de Castilla y Granada. Los mensajes más allá de las formas. Anales de Historia del Arte 23: 305–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, Gertrud. 1972. Iconography of Chistian Art. Vol 2. The Passion of Jesus Christ. Greenwich: New York Graphic Society Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Senra Gabriel y Galán, José Luis. 1992. La irrupción borgoñona en la escultura castellana de mediados del siglo XII. Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte 4: 35–52. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/2740 (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Senra Gabriel y Galán, José Luis. 1995. L’influence clunisienne sur la sculpture castillane du milieu du XIIe siecle: San Salvador de Oña et San Pedro de Cardeña. Bulletin Monumental 153: 267–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senra Gabriel y Galán, José Luis. 2012. Entre la santidad y la epopeya: Rastreando el desaparecido claustro románico del Monasterio de San Salvador de Oña. In Actas del Congreso Internacional Sobre el Monasterio de Oña, 1011–2011. Edited by Rafael Sánchez Domingo. Burgos: Fundación Milenario San Salvador de Oña, pp. 398–421. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Maroto, Pilar. 1974. El Monasterio de Oña en Tiempos de los Reyes Católicos. Madrid: Instituto Diego Velázquez. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Cyril Stanley, and John G. Hawthorne. 1974. Mappae Clavicula: A Little Key to the World of Medieval Techniques. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 64: 1–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teófilo. 1979. On Divers Arts: The Foremost Medieval Treatise on Painting, Glassmaking and Metalwork. Edited by John G. Hawthorne and Cyril Stanley Smith. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tour Turístico Oña. 2016. Available online: https://www.xn--monasteriodeoa-2nb.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Tour_Turistico_monasterio_ona.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Valdeón Baruque, Julio. 2002. Pedro I el Cruel y Enrique II de Trastámara. ¿La primera guerra civil española? Madrid: Aguilar. [Google Scholar]

- Valdeón Baruque, Julio. 2024a. Alfonso XI. DB-e. Real Academia de la Historia. Available online: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/6406/alfonso-xi (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Valdeón Baruque, Julio. 2024b. Enrique II. DB-e. Real Academia de la Historia. Available online: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/6635/enrique-ii (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Yepes, Fray Antonio de. 1960. Crónica General de la Orden de San Benito. Madrid: Atlas, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza, Pascual Ernesto. 1994. Abadología del monasterio de San Salvador de Oña (siglos XI–XIX). Burgense: Collectanea Scientifica 35: 557–94. [Google Scholar]

| Piece | Width (cm) | Height (cm) | Depth (cm) | Outer Archivolt (cm) | Inner Archivolt (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arch 1 | 129.5 | 60 | 27 | 7 | 8 |

| Arch 2 | 117 | 60 | 27 | 7.5 | 8.5 |

| Arch 3 | 70 | 60 | 27 | 6 | 8 |

| Arch 4 | 80 | 60 | 27 | 7 | 9 |

| Arch 5 | 123 | 60 | 27 | 8.5 | 9 |

| TOTALS | 519.5 | 60 | 27 | - | - |

| Set Piece | Code Piece | Width (cm) | Height (cm) | Depth (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT1 | P23 | 45 | 9 | 42.5 |

| CP1 | P24 | 32.5 | 28 | 58 |

| CT2 | P31 | 26.5 | 10 | 24.5 |

| P27 | 42 | 10 | 42 | |

| CP2 | P22 | 32 | 28 | 53.2 |

| CT3 | P25 | 42 | 10 | 58 |

| CP3 | P29 | 32.5 | 27.5 | 53.5 |

| CT4 | P20 | 44,5 | 10 | 42 |

| CP4 | P28 | 32.5 | 28 | 46.5 |

| Layer | Color | Thickness | Pigments/Fillers | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | White | 0–20 | Calcium carbonate, earth pigments (very low proportion), gypsum (very low proportion), bone black (very low proportion) | Remains of a possible whitewashing |

| 2 | Black | 0–10 | Charcoal, bone black (very low proportion) | Hints of a layer of paint |

| 1 | White | 45–60 | Gypsum, silicates (very low proportion) | Possible plastering 1 |

| Layer | Color | Thickness (µm) | Pigments/Fillers | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Black | 0–15 | Charcoal, white lead (low proportion), oropiment (very low proportion) | Paint layer |

| 1 | White | 50–100 | Gypsum | Possible plastering |

| Layer | Color | Thickness (µm) | Pigments/Fillers | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Orange | 0–15 | Earth pigments, charcoal (very low proportion), minium (very low proportion) | Paint layer |

| 1 | White | 25–150 | gypsum, silicates (very low proportion) | Possible plastering |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuesta Sánchez, A.M. Interpreting Visuality in the Middle Ages: The Iconographic Paradigm of the Refectory of the Monastery of San Salvador de Oña. Religions 2024, 15, 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091092

Cuesta Sánchez AM. Interpreting Visuality in the Middle Ages: The Iconographic Paradigm of the Refectory of the Monastery of San Salvador de Oña. Religions. 2024; 15(9):1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091092

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuesta Sánchez, Ana Maria. 2024. "Interpreting Visuality in the Middle Ages: The Iconographic Paradigm of the Refectory of the Monastery of San Salvador de Oña" Religions 15, no. 9: 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091092

APA StyleCuesta Sánchez, A. M. (2024). Interpreting Visuality in the Middle Ages: The Iconographic Paradigm of the Refectory of the Monastery of San Salvador de Oña. Religions, 15(9), 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091092