Engaging with Climate Grief, Guilt, and Anger in Religious Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

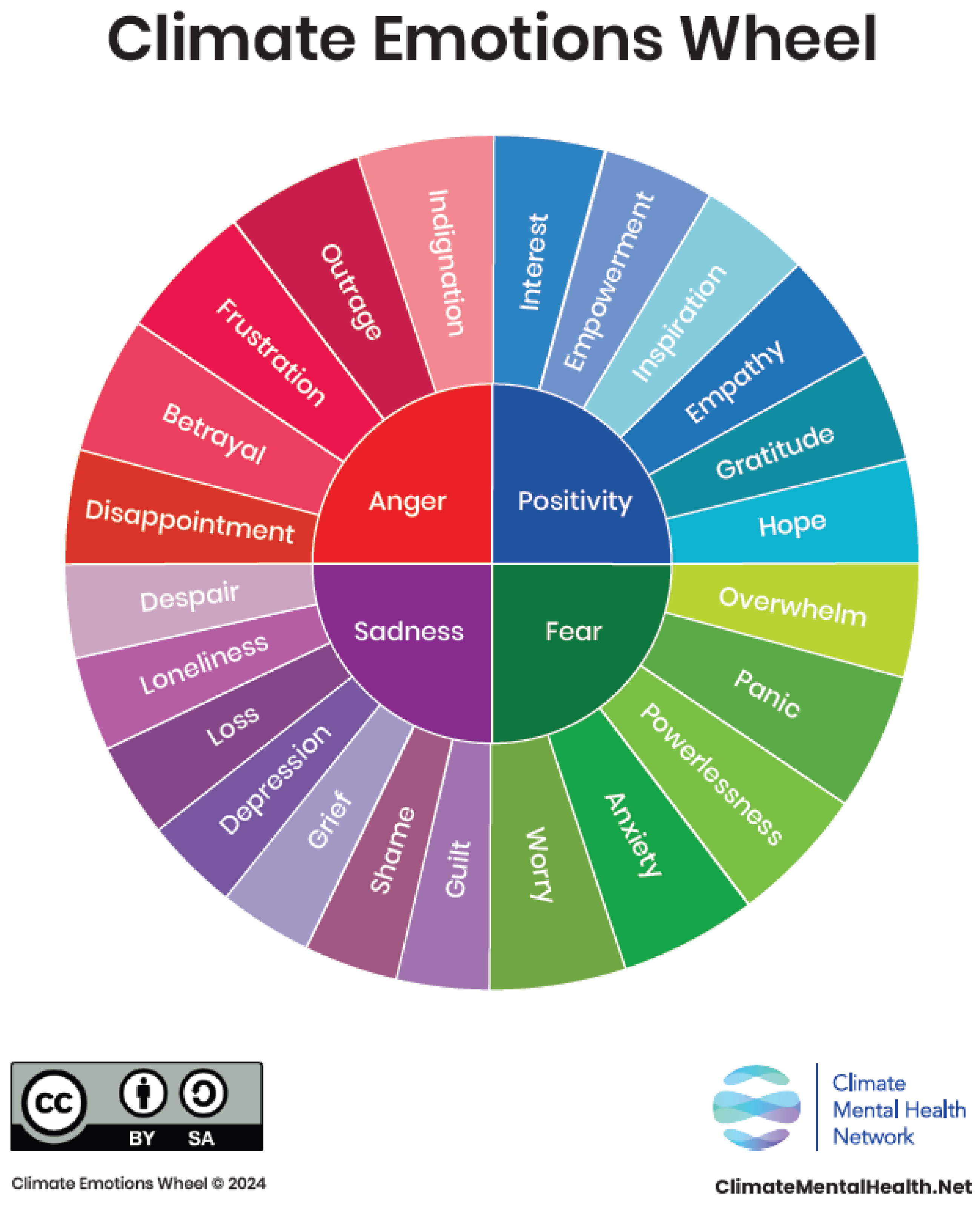

2. Dynamics of Climate Emotions

2.1. Guilt

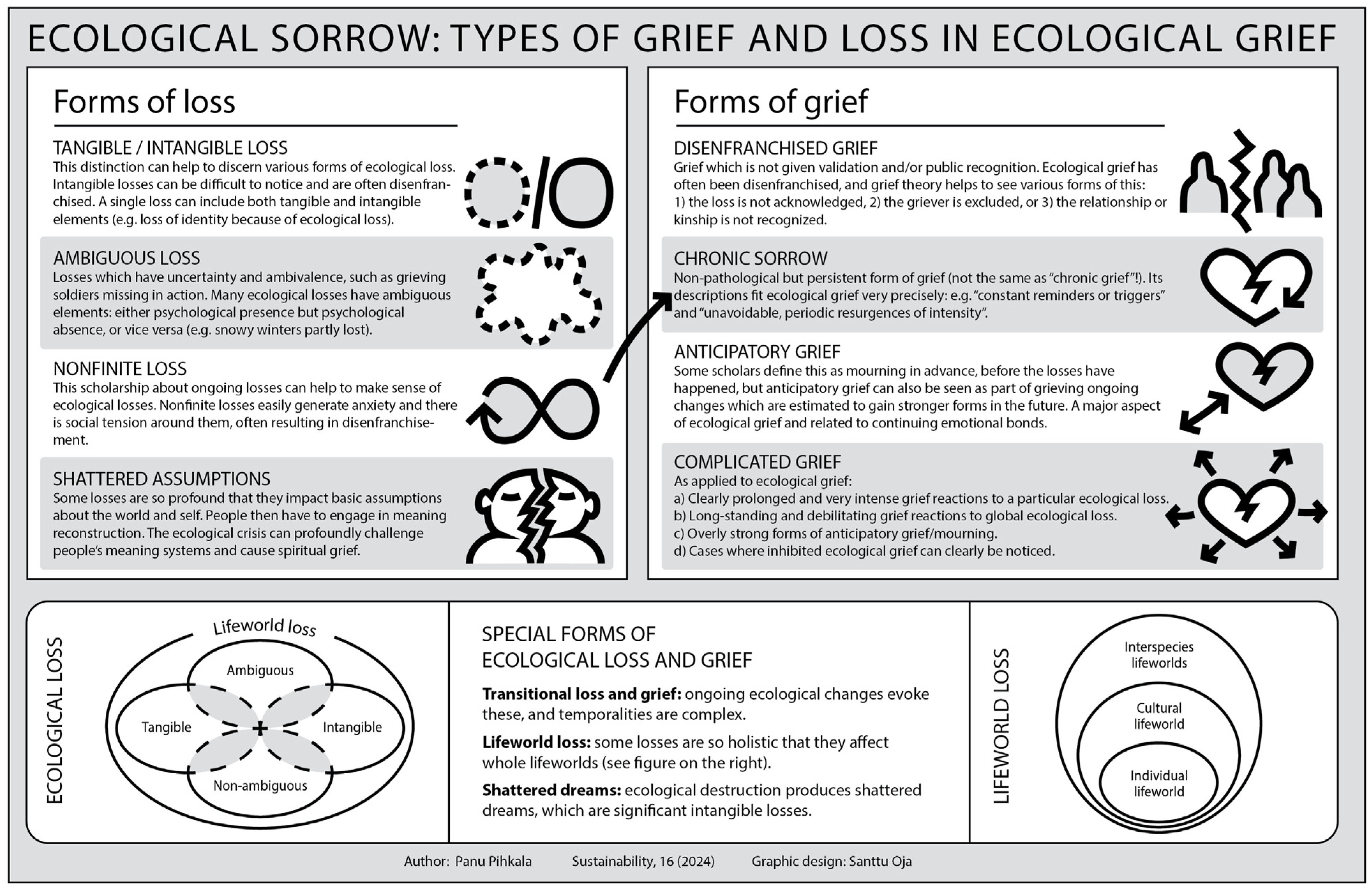

2.2. Grief

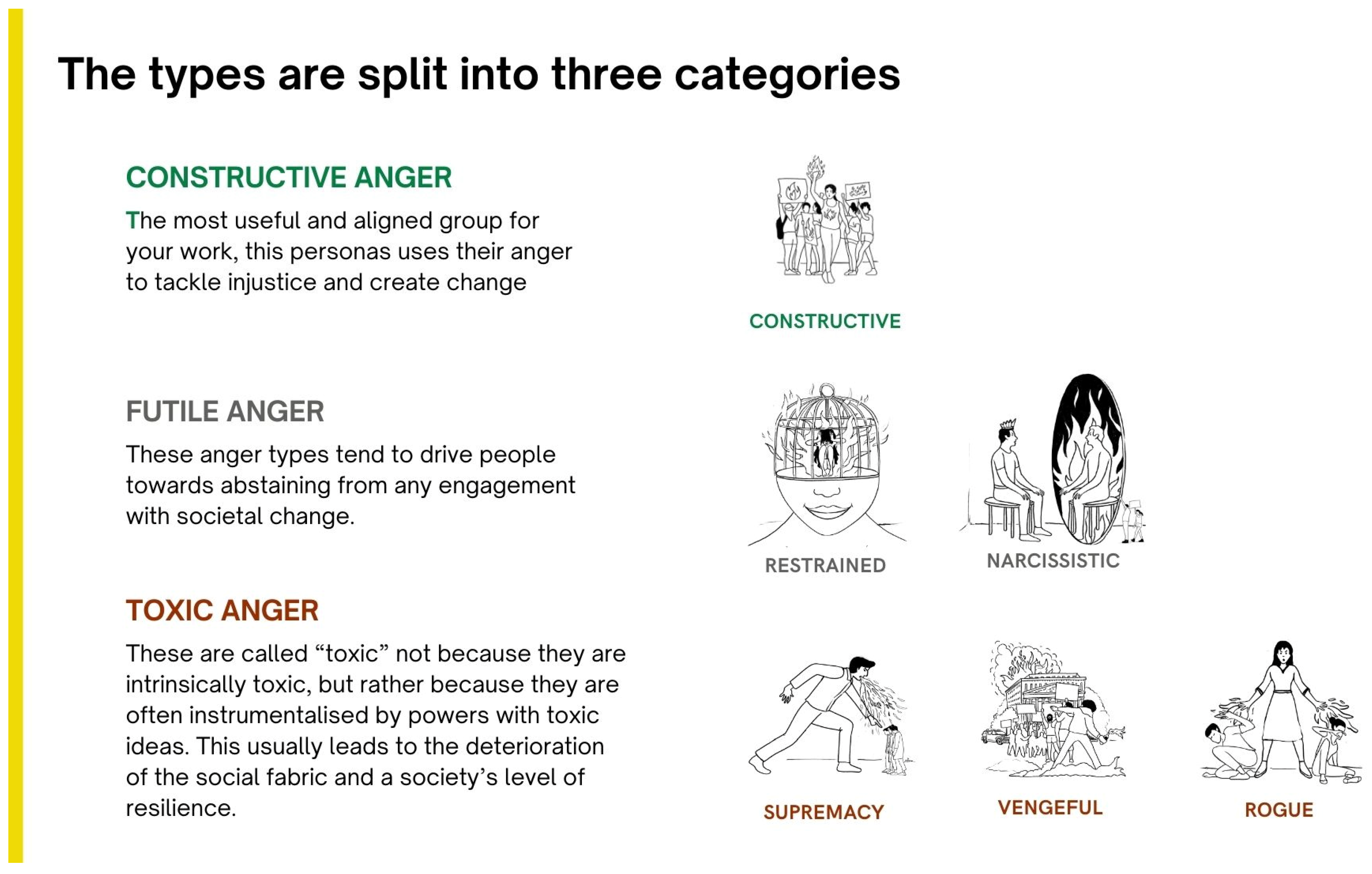

2.3. Anger

2.4. Empathy and Care

3. Paradigm for Engaging with Climate Emotions

- Climate emotions can be linked with the well-being of members of the (religious) community. This is greatly impacted by the socio-ecological context. Some people already face much more dire consequences of the climate crisis.

- Climate emotions are related to ethical imperatives around climate issues. For example, guilt, anger, and sadness are all connected with issues related to responsibility and the losses that have already taken place.

3.1. Working with One’s Own Emotions

- What climate emotions do I recognize feeling? When and why?

- Are there bodily sensations that I find difficult to link with certain emotions? Who and what could help me in developing my skills of recognition and somatic methods?

- What kinds of attitudes do I have in relation to various emotions and climate emotions? Do I think that certain emotions are better than others? If so, which ones, and why? What could an emotion-positive attitude (Greenspan 2004) look like for me?

3.2. Exploring the Various Forms and Dynamics of Climate Emotions

- What climate emotions are often closely connected in my experiences? How do these emotions affect each other?

- When I think of people close to me, what about the same dynamics?

- Do I notice trajectories of climate emotions? Moving from a primary emotion to a secondary reactive one? Or just common cycles of emotions?

- When I or people close to me think of a certain climate emotion, what kind of intensity do they basically have in mind? Is there room for various levels of intensities?

3.3. Contextualizing Climate Emotions in the Community

- What kinds of factors impact the climate emotions of people I work or live with?

- What kinds of issues of climate (in)justice are present? Is there injustice about climate emotions themselves? (For the latter point, “emotional injustice” related to the climate crisis, see Verlie 2024).

- How have people’s experiences and their socio-economic status influenced the ways in which they experience climate emotions and react to them? (e.g., Crandon et al. 2022) Have they experienced direct impacts of climate change, including natural disasters intensified by global warming? (see Swain 2020; Ramsay and Manderson 2011; Chen et al. 2020).

3.4. Supporting Constructive Engagement with Climate Emotions Via Various Methods (e.g., Action, Rituals, Spiritual Practices)

- What do I think about “way of action” and “way of non-action” as possibilities for engaging with climate emotions? Does my spiritual community participate in both, or only one of these? What would be the possibilities?

- Are there current practices in my spiritual community that are helpful for engaging with climate emotions?

- How could existing practices be modified or adapted into new ones so that various climate emotions could be better engaged with?

4. Climate Guilt and Religious Communities

4.1. Challenges and Dynamics of Climate Guilt (and Shame)

Sergio buys a new phone and feels glad, but at the same time he remembers the carbon cost of the production of the phone and feels slightly guilty. He starts downloading new apps and suppresses the guilt.

Maria takes a flight after a while. On the plane, she feels both excitement about the travel and guilt for the climate emissions. She also remembers global inequity, and her flight guilt mingles with her guilt of being a part of the more affluent population who can travel. She makes a decision to pay more carbon offsets.

Lee and Huang watch a nature documentary about a coral reef, which is being destroyed by climate change. They feel shame about being part of a human race who has not been able to change its ways of life. Huang, a committed Christian, wonders whether God will forgive humanity for its ecological sins.

4.2. Tasks and Skills of Engaging with Climate Guilt and Shame

4.2.1. Working with One’s Own Climate Guilt and Shame

- How do I personally evaluate climate guilt? Do I think that it is useful? Are there differences between the usefulness of it in various situations? Are some forms of climate guilt more constructive than others?

- What about climate shame and these same questions?

- Do I personally feel ecological guilt and/or climate guilt? If so, when and in what forms?

- How do I react to ecological guilt and/or climate guilt? And how do I react to guilt-provoking situations in general?

- What coping methods do I personally prefer in relation to climate guilt and shame? How do my preferences for these methods affect my views about how others should respond to climate guilt and/or shame?

4.2.2. Exploring the Various Forms of Climate Guilt and Shame

- What kinds of issues evoke climate guilt and/or shame in the members of my community? And what levels of intensities do these various feelings have? How do people generally react to them?

- Are there people in my community who do not feel any climate guilt even if they should? Are there people who practice climate disavowal or even denial, and what could be the relation of dynamics of guilt and shame to that?

- Are there people in my community who are feeling overly strong burdens of eco-guilt or shame? How much do these people over-individualize structural problems? What are the psychological and spiritual needs generated by this?

4.2.3. Contextualizing Climate Guilt and Shame

- What kinds of factors impact the various forms of climate guilt and shame in the community and people’s reactions to these feelings? For example, how are different backgrounds and professions related to this?

- When analyzed from the point of view of ethics and socio-political analysis, how much climate guilt and/or shame is relevant to be felt by the various members of my community?

- What needs do people have behind their climate emotions, and how could these be engaged with?

4.2.4. Supporting Constructive Engagement with Climate Guilt and Shame

- Speaking about the complexities of climate guilt, culpability, and responsibility (for guidelines, see Bryan 2024; Oziewicz 2024). Simply speaking from the heart about this complexity and implicity can help (see the reflections in Ward 2020). Naturally, in the long run, actions of reparation are needed too. Talking directly about psychosocial phenomena such as “the double bind of sustainable consumption,” “the hippie-hypocrite paradox,” and “scapegoat ecology” can help people to react to them more constructively.

- Providing opportunities for confessing climate guilt (cf. “ecological sins”), but avoiding problematic uses of the word “we” (Oziewicz 2024; Mihai and Thaler 2023). Religious communities often use a very universalizing “we” in ecological confessions: a typical example is “we have laid waste the good earth you have made” (The Anglican Church of Australia n.d.). Who exactly is this “we” when it is known that 71 percent of the climate emissions since 1988 have been produced by only 100 companies? (Riley 2017) Confessions should use language that recognizes culpability but also situates it in the global context (Malcolm 2020b).

- Using symbolic, material objects to help people engage with climate guilt and shame. Powell (Powell 2019) has analyzed an interesting example of this. The California-based Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries employs ecological shame and climate shame creatively in its spiritual practice and leadership. The leaders of this organization make these feelings manifest materially: for example, they have used as an altar a burned tree stump from wildfires made more intense by climate change. They also explicitly link climate shame with the whole collective, including the leaders. Powell argues that these kinds of methods help the members of the community both to encounter difficult emotions and to increase their moral motivation for ecological action.

- Bringing out the connections between climate grief and guilt (see also Prade-Weiss 2021); talking about how guilt and shame can prevent grieving; pointing out that ecological confessions can include both guilt and grief—grieving the wrongdoings; and discussing the reasons for moral outrage in climate matters, in addition to guilt and grief.

- Many of the things above are, to use terms from Greenspan, “ways of non-action.” Ecological guilt and shame can be engaged with by various kinds of action, either implicitly or explicitly. The motivation to engage in public witness can be linked with counteremotions of climate guilt and shame: pointing out that it is honorable to do our part.

5. Climate Grief and Religious Communities

5.1. Principles of Environmental Commemoration

5.2. Tasks and Skills of Engaging with Climate Grief

5.2.1. Working with One’s Own Climate Grief

- What is my general attitude towards grief and sadness?

- Have I experienced sadness or grief in relation to environmental changes? If so, what kind?

- Am I using coping methods in relation to climate grief or sadness? If so, what kind? Are there benefits and challenges in the usage of these methods?

5.2.2. Exploring the Various Forms of Climate Sadness and Grief

- What kinds of climate change-related loss and grief do people in my religious community experience?

- What forms of loss and grief are difficult for me to encounter and why? Do I have some special strengths in encountering some of them?

- Are there spiritual losses interconnected with ecological losses?

5.2.3. Contextualizing Climate Grief and Sadness

- What are the wider stories behind climate grief and sadness of the members of the community?

- What kinds of factors shape people’s feelings and their reactions to these feelings?

5.2.4. Supporting Constructive Engagement with Climate Sadness and Grief

- Helping the religious community to develop a grief-positive attitude (Greenspan 2004): understanding the important functions of grief and being aware of possible depression and “complicated grief” (Pihkala 2024d; Comtesse et al. 2021).

- Framing climate grief as a religious issue (e.g., Malcolm 2020a) and understanding its spiritual dimensions (e.g., Weller 2015).

- Providing help in naming and recognizing various forms of climate grief and sadness.

- Exploring various terms that might help people of different ages to engage with climate loss and grief. For example, older people may find concepts such as “climate grief” unfamiliar, even when they feel related loss (Dennis and Stock 2023).

- Helping people to observe dynamics of their loss and grief experiences and providing information about how to engage with these dynamics. For example, observing possible dynamics of ambiguous loss and engaging with counseling literature about how to deal with ambiguous loss (e.g., Boss 2022).

- Providing psychoeducation about the need for grieving, rest, and action in the context of climate grief (see the process model offered by Pihkala 2022b). If action is the only channel for grieving, there is a significant risk for complications in the long run (e.g., Hickman 2023).

- Engaging with both past and anticipated losses with spiritual practices such as liturgy, laments, prayers, and memorials (e.g., Hessel-Robinson 2012; Lambelet 2020; Bauman 2014). Furthermore, it would be marvelous if transitional losses (Pihkala 2024d; Rosemary Randall 2009) could also be engaged with.

- Exploring possible rituals for climate grief with “ritual creativity” (for the idea, see Grimes 2013; for applying it to ecological grief, see Weller 2015; T. Johnson 2017).

- In rituals: paying tribute to what has been, perhaps by letting go of something, and orienting towards something new. The frameworks of re-learning the world (Attig 2015) and meaning reconstruction (Neimeyer 2019; Neimeyer and Burke 2015; Neimeyer 2016, 2022) offer insights for this.

- Offering at least information about peer groups and facilitated sessions where climate grief and sadness can be safely discussed, such as The Good Grief Network (Schmidt 2023; Good Grief Network 2021) and The Work that Reconnects (Macy and Brown 2014; Work That Reconnects Network 2024). Consider organizing “Climate Cafés,” “Climate circles,” or other safe spaces for this (Broad 2024).

- Way of action: channeling climate grief into climate action with the help of climate anger or determination (Salamon 2020; Kelsey 2020). Please note, however, that it may not be safe to be vulnerable with climate grief in a public space, and safe spaces for climate mourning are needed in addition to integrations of grief and action (for discussion, see Skrimshire 2019; Brewster 2020; de Massol de Rebetz 2020).

6. Climate Anger and Religious Communities

6.1. Varieties of Climate Anger

- Lisa watches in astonishment as the prime minister of her country disavows climate change in his speech. She is filled with moral outrage and enrolls in an Extinction Rebellion street blockade next week.

- Max is a member at a church council meeting where energy options are discussed. He feels growing annoyance and anger when listening to another member who speaks on behalf of continuing to use coal instead of investing in renewables. Max almost lashes out at the man in his own speech but manages to practice mindfulness and tones his message into non-violent communication, searching for ways to make a better decision together. His anger keeps burning in the form of determination inside him.

6.2. Tasks and Skills of Engaging with Climate Anger

6.2.1. Working with One’s Own Climate Anger

- How do I evaluate anger and rage in general? Do I think of them mainly as vices, or do I see some virtue in them?

- How do my own personal history and my temperament affect my views about anger and its varieties?

- Have I personally felt moral outrage in relation to climate change? If so, when? Where did these feelings lead me?

- How do I react to various forms of eco-anger or climate rage among people I encounter?

- How does my religious and cultural background affect my attitude towards (climate) anger?

6.2.2. Exploring the Various Forms of Climate Anger

- Which kinds of eco-anger or climate rage exist in my community? What are the objects and intensities? You can consult the MindWorks anger guide (Flothmann 2023) (Figure 3) for quick reference. Are there people who suffer from restricted anger?

- How do people in my community usually react to (climate) anger? Do they differentiate between various kinds of anger and anger responses? Are there people who react to climate issues with problematic or even toxic forms of anger?

- How do I react to the various kinds of anger and anger reactions that people express, and why? What could be constructive ways forward?

6.2.3. Contextualizing Climate Anger

6.2.4. Supporting Constructive Engagement with Climate Anger

- Providing a religious framing of anger as a virtue and not just a vice, while warning about the unethical potentials in anger: in other words, raising up the importance of constructive anger or “Lordean rage” (Bergman 2023; Cherry 2021). There are resources in various religions for these interpretations. For example, in a Christian context, Chase (Chase 2011a, 2011b) connects the story of Jesus getting angry in the temple with the need for moral outrage in relation to environmental issues (for Buddhist resources, see McRae 2018).

- Practicing lament, which can include both grief, guilt, and/or moral outrage. Many ancient laments speak on behalf of the oppressed, asking how long they have to suffer. Climate lament offers powerful possibilities to engage with many climate emotions at the same time (e.g., Brocker 2016; Malcolm 2020b).

- The simplest way to provide events that help channel climate anger is the way of action. This connection can and perhaps should be voiced: working for structural change and against injustices is a way of manifesting constructive climate anger (e.g., Moe-Lobeda 2013; A. E. Johnson and Wilkinson 2020). For example, demonstrations offer possibilities to vent anger out somatically (e.g., Landmann and Naumann 2024). As regards the way of non-action and rituals, it is worth asking the following: Could there be ritualistic, symbolic events that help in engaging constructively with anger? It is easy to think of such events and practices for guilt and grief, but what could they be like for anger? (For discussion, see Rebecca Randall 2023).

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | There is growing recognition in both research and public discussion that the affective dimensions of climate crisis need more attention (e.g., Brosch and Sauter 2023; Cunsolo et al. 2020; Voşki et al. 2023). However, there is still great variation about the levels of this recognition in different contexts and discourses, and there are often social disputes about climate emotions. That was to be expected, because both the topics of (a) emotions in culture and (b) the climate crisis are so loaded. Feeling rules and emotion norms are a major part in power dynamics related to the climate crisis (e.g., Neckel and Hasenfratz 2021; González-Hidalgo and Zografos 2020). Some feelings and emotions have been suppressed or repressed by powerful social actors, and other feelings have been endorsed as normatively correct responses to the crisis (for normativity of climate emotions, see Mosquera and Jylhä 2022). For example, it is typical that climate grief has been suppressed or disenfranchised (Pihkala 2024d). Scholarship in affect theory and cultural politics of emotion has rightly criticized the normative uses of power in relation to “climate affect” (e.g., Verlie 2022). |

| 2 | There are also religious communities that distance themselves from any engagement with environmental and/or climate issues, and these are not discussed here, except for mentioning the possibility that such distancing can also be a negative coping method in relation to climate guilt and anxiety (Pihkala 2024e). |

| 3 | A methodological note about concepts: The choice of which concepts to use is a challenging one in relation to climate emotions/affect/feelings. In this article, the choice is made to use the concept “emotion” as a general term, reflecting common tendencies in related research (for discussion, see Pihkala 2022c; Hamilton 2020). However, it should be noted that sadness, guilt, and anger include manifestations that are well captured by affect theories (Gregg and Seigworth 2010) and by the use of the concept of feeling: there are both conscious and unconscious instances of them, and temporally both short and long manifestations of them. In scholarship, often the wording “climate emotions” is used as a general term for the whole field that others call “climate affect” or “climate feelings” (Pihkala 2022c; Hamilton 2020, 2022). There are important questions to be addressed in relation to theories and uses of concepts, but for the purpose of this article, the most significant fact is that there are indeed various kinds of manifestations of these emotions. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Various concepts and theories can be utilized to understand interconnections between emotions. Emotion philosopher Rinofner-Kreidl (Rinofner-Kreidl 2016) uses the concept of “interlaced emotions” to point out that emotions may be intimately interconnected (see also McLaren 2010). The context of her discussion is, relevantly to this article, grief. For trajectories between emotions, an approach called Emotion-Focused Therapy (Elliott and Greenberg 2021) often utilizes a distinction between primary emotions and secondary emotions. Primary emotions are the first reactions to a situation, and secondary reactive emotions may be generated in response to that situation or to the primary emotion (Elliott and Greenberg 2021, pp. 35–36). For example, a person may first feel anger, but because of social conditioning, she may feel that she should not be angry and ends up feeling shame because of her anger. For example in Finland, women have often been socialized into being ashamed of their anger, and this has impacted people’s climate emotions (for a case example, see Leukumaavaara 2019). There may be various kinds of primary and secondary emotion dynamics in relation to climate matters, and it is important to try to observe these. |

| 6 | The RAIN method was originally named by Michele McDonald, but it has been made famous by another Buddhist meditation teacher: psychologist and author Tara Brach. Originally, the last phase, “N,” stood for “non-identification,” but Brach wanted to give more emphasis on compassion and remove confusion about what non-identification actually meant (Brach 2019, pp. 246–47). The RAIN method has become rather well-known, and it has been proposed to be used for climate emotions by several authors (Ray 2020; Salamon 2020). Psychotherapist and author Miriam Greenspan wrote an influential book about “dark emotions” in 2004, already then discussing how environmental issues cause distress and various emotions (Greenspan 2004). Currently, her work is much less known than Brach’s and RAIN, but it has influenced contemporary eco-emotion research (e.g., Pihkala 2018). |

| 7 | The highly nuanced model of various valences developed by scholars Bellocchi and Turner (Bellocchi and Turner 2019) is very useful in this regard, for it helps in realizing the many ways in which valence can be attributed. Possible grounds for evaluating valences include, for example, ethical views, pleasure or displeasure when feeling the emotion, the role of the emotion in relation to reaching some practical goal, and the social consequences related to either avoidance or manifestation of the emotion. Awareness of these kinds of factors aids in understanding the dynamics of people’s emotional responses and their attitudes about those. For example, there are people who valence climate guilt as very valuable and people who valence it as something unjust, and many psychosocial, cultural, and political dynamics influence these evaluations (Aaltola 2021; Fredericks 2021). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | Measures of religious coping, such as the RCOPE (e.g., Pargament et al. 2000), can be used to explore variations in reactions to climate guilt, but as Pihkala (Pihkala 2024e) argues, these measures need critical adaptation when applied to eco-emotions. |

| 10 | Fredericks (2021) engages in an in-depth discussion of when and how it would be ethical to evoke environmental guilt and/or shame (see also Jacquet 2015; Aaltola 2021). She also provides useful distinctions about individual and collective types of ecological guilt and shame, since these can be felt in various forms: individuals about themselves, individuals about other individuals in their group or about the group as a whole, or the group about the whole group (see esp. chapter 3 and tables 3.5. and 3.6 in her book). |

References

- Aaltola, Elisa. 2021. Defensive over Climate Change? Climate Shame as a Method of Moral Cultivation. Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics 34: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Jennifer L. 2020. Environmental Hospice and Memorial as Redemption: Public Rituals for Renewal. Western Journal of Communication 84: 586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Amoak, Daniel, Benjamin Kwao, Temitope Oluwaseyi Ishola, and Kamaldeen Mohammed. 2023. Climate Change Induced Ecological Grief among Smallholder Farmers in Semi-Arid Ghana. SN Social Sciences 3: 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthamohan, Archuna. 2020. The Wrath of God. In Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church. Edited by Hannah Malcolm. London: SCM Press, pp. 180–84. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Judith, Tree Staunton, Jenny O’Gorman, and Caroline Hickman, eds. 2024. Being a Therapist in a Time of Climate Breakdown. Oxon and New York: Routledge and CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antadze, Nino. 2020. Moral Outrage as the Emotional Response to Climate Injustice. Environmental Justice 13: 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Jennifer, and Sarah Jaquette Ray, eds. 2024. The Existential Toolkit for Climate Justice Educators: How to Teach in a Burning World, 1st ed. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Attig, Thomas. 2015. Seeking Wisdom about Mortality, Dying, and Bereavement. In Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices. Edited by Thomas Attig and Judith M. Stillion. New York: Springer Publishing Company, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ágoston, Csilla, Benedek Csaba, Bence Nagy, Zoltán Kőváry, Andrea Dúll, József Rácz, and Zsolt Demetrovics. 2022a. Identifying Types of Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Coping in a Climate-Sensitive Population: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ágoston, Csilla, Róbert Urbán, Bence Nagy, Benedek Csaba, Zoltán Kőváry, Kristóf Kovács, Attila Varga, Ferenc M’onus, Carrie A. Shaw, and Zsolt Demetrovics. 2022b. The Psychological Consequences of the Ecological Crisis: Three New Questionnaires to Assess Eco-Anxiety, Eco-Guilt, and Ecological Grief. Climate Risk Management 37: 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Joshua Trey. 2021. Vigilant Mourning and the Future of Earthly Coexistence. In Communicating in the Anthropocene: Intimate Relations. Edited by Alexa M. Dare and C. Vail Fletcher. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 13–33. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/45053987/Vigilant_Mourning_and_the_Future_of_Earthly_Coexistence (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Barnett, Joshua Trey. 2022. Mourning in the Anthropocene: Ecological Grief and Earthly Coexistence. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Lisa Feldman, Michael Lewis, and Jeannette Haviland-Jones, eds. 2016. Handbook of Emotions, 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Whitney. 2014. South Florida as Matrix for Developing a Planetary Ethic: A Call for Ethical Per/Versions and Environmental Hospice. Journal of Florida Studies 1: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchi, Alberto, and Jonathan H. Turner. 2019. Conceptualising Valences in Emotion Theories: A Sociological Approach. In Emotions in Late Modernity. Edited by Roger Patulny, Alberto Bellocchi, Rebecca E. Olson, Sukhmani Khorana, Jordan McKenzie and Michelle Peterie. London: Routledge, pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benham, Claudia, and Doortje Hoerst. 2024. What Role Do Social-Ecological Factors Play in Ecological Grief?: Insights from a Global Scoping Review. Journal of Environmental Psychology 93: 102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, Laelia, Isaiah Thomas, and Andrés Martin. 2022. Review: Ecological Awareness, Anxiety, and Actions among Youth and Their Parents—A Qualitative Study of Newspaper Narratives. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 27: 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, Ondřej. 2024. Ecological Grief Observed from a Distance. Philosophies 9: 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, Kristoffer. 2019. There Is No Alternative: A Symbolic Interactionist Account of Swedish Climate Activists. Lund University, Department of Sociology. Available online: http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/8990902/file/8990903.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Bergman, Harriët. 2023. Anger in Response to Climate Breakdown. Zeitschrift Für Ethik Und Moralphilosophie 6: 269–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blower, David Benjamin. 2020. The Knotted Conscience of Privilege. In Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church. Edited by Hannah Malcolm. London: SCM Press, pp. 151–54. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, Pauline. 2022. The Myth of Closure: Ambiguous Loss in a Time of Pandemic and Change, 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company New York. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma-Prediger, Steven C. 1995. The Greening of Theology: The Ecological Models of Rosemary Radford Ruether, Joseph Sittler, and Juergen Moltmann. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Andrew. 2023. I Want a Better Catastrophe: Navigating the Climate Crisis with Grief, Hope, and Gallows Humor. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Brach, Tara. 2019. Radical Compassion: Learning to Love Yourself and Your World with the Practice of RAIN. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, Shelby. 2020. Remembrance Day for Lost Species: Toward an Ethics of Witnessing Extinction. Performance Research 25: 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridewell, Will B., and Edward C. Chang. 1997. Distinguishing between Anxiety, Depression, and Hostility: Relations to Anger-in, Anger-out, and Anger Control. Personality and Individual Differences 22: 587–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad, Gillian. 2024. ‘Ways of Being’ When Facing Difficult Truths: Exploring the Contribution of Climate Cafes to Climate Crisis Awareness. In Being a Therapist in a Time of Climate Breakdown. Edited by Judith Anderson, Tree Staunton, Jenny O’Gorman and Caroline Hickman. Oxon and New York: Routledge and CRC Press, pp. 229–36. [Google Scholar]

- Brocker, Mark S. 2016. Coming Home to Earth. Eugene: Cascade Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks Pribac, Teya. 2021. Enter the Animal: Cross-Species Perspectives on Grief and Spirituality, 1st ed. Sydney: Sydney University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, Tobias, and Disa Sauter. 2023. Emotions and the Climate Crisis: A Research Agenda for an Affective Sustainability Science. Emotion Review 15: 253–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, Tobias, and Linda Steg. 2021. Leveraging Emotion for Sustainable Action. One Earth 4: 1693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Brené. 2021. Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. Color illustrations Vols. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Audrey. 2024. The Social Ecology of Responsibility: Navigating the Epistemic and Affective Dimensions of the Climate Crisis. In The Existential Toolkit for Climate Justice Educators: How to Teach in a Burning World, 1st ed. Edited by Jennifer Atkinson and Sarah Jaquette Ray. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 201–9. [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Christie, Douglas. 2011. The Gift of Tears: Loss, Mourning and the Work of Ecological Restoration. Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology 15: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 2003. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, Ed, Jared Kenworthy, Andrea Campbell, and Miles Hewstone. 2006. The Role of In-Group Identification, Religious Group Membership and Intergroup Conflict in Moderating in-Group and out-Group Affect. British Journal of Social Psychology 45: 701–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, Daniel, Brian Lickel, and Ezra M. Markowitz. 2017. Reassessing Emotion in Climate Change Communication. Nature Clim Change 7: 850–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, Steven. 2011a. A Field Guide to Nature as Spiritual Practice. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, Steven. 2011b. Nature as Spiritual Practice. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shuquan, Rohini Bagrodia, Charlotte C. Pfeffer, Laura Meli, and George A. Bonanno. 2020. Anxiety and Resilience in the Face of Natural Disasters Associated with Climate Change: A Review and Methodological Critique. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 76: 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, Myisha. 2021. The Case for Rage: Why Anger Is Essential to Anti-Racist Struggle. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, Myisha, and Owen Flanagan, eds. 2018. Moral Psychology of Anger. Moral Psychology of the Emotions Volume 4. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Jordan Blum. 2016. Moving Through Grief and Water: How Jewish Ritual Can Help Us Process Environmental Loss. Bachelor’s thesis, Middlebury College, Middlebury, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Comtesse, Hannah, Verena Ertl, Sophie M. C. Hengst, Rita Rosner, and Geert E. Smid. 2021. Ecological Grief as a Response to Environmental Change: A Mental Health Risk or Functional Response? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conniff, Richard. 2008. Carbon Offsets: The Indispensable Indulgence. Yale Environment 360. September 29. Available online: https://e360.yale.edu/features/carbon_offsets_the_indispensable_indulgence (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Conradie, Ernst. 2010. Confessing Guilt in the Context of Climate Change: Some South African Perspectives. Scriptura: Journal for Contextual Hermeneutics in Southern Africa 103: 134–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, Isabel, and Panu Pihkala. 2023. Complex Dynamics of Climate Emotions among Environmentally Active Finnish and American Young People. Frontiers in Political Science 4: 1063741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozort, Daniel. 1995. ‘Cutting the Roots of Virtue’: Tsongkhapa on the Results of Anger. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 2: 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Crandon, Tara J., James G. Scott, Fiona J. Charlson, and Hannah J. Thomas. 2022. A Social–Ecological Perspective on Climate Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Nature Climate Change 12: 123–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, Ashlee, and Karen Landman, eds. 2017. Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cunsolo, Ashlee, and Neville R. Ellis. 2018. Ecological Grief as a Mental Health Response to Climate Change-Related Loss. Nature Climate Change 8: 275–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, Ashlee, Sherilee L. Harper, Kelton Minor, Katie Hayes, Kimberly G. Williams, and Courtney Howard. 2020. Ecological Grief and Anxiety: The Start of a Healthy Response to Climate Change? The Lancet.Planetary Health 4: e261–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Debra J., and Maik Kecinski. 2022. Emotional Pathways to Climate Change Responses. WIREs Climate Change 13: e751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Massol de Rebetz, Clara. 2020. Remembrance Day for Lost Species: Remembering and Mourning Extinction in the Anthropocene. Memory Studies 13: 875–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMello, Margo. 2016. Mourning Animals: Rituals and Practices Surrounding Animal Death. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, Mary Kate, and Paul Stock. 2023. ‘You’re Asking Me to Put into Words Something That I Don’t Put into Words.’: Climate Grief and Older Adult Environmental Activists. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschênes, Sonya S., Michel J. Dugas, Katie Fracalanza, and Naomi Koerner. 2012. The Role of Anger in Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 41: 261–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffey, James, Sacha Wright, Jennifer Olachi Uchendu, Shelot Masithi, Ayomide Olude, Damian Omari Juma, Lekwa Hope Anya, Temilade Salami, Pranav Reddy Mogathala, Hrithik Agarwal, and et al. 2022. ‘Not about Us without Us’—the Feelings and Hopes of Climate-Concerned Young People around the World. International Review of Psychiatry 34: 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, Joseph. 2011. Psychoanalysis and Ecology at the Edge of Chaos: Complexity Theory, Deleuze/Guattari and Psychoanalysis for a Climate in Crisis. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Doka, Kenneth. 2020. Disenfranchised Grief and Non-Death Losses. In Non-Death Loss and Grief: Context and Clinical Implications. Edited by Darcy L. Harris. New York: Routledge, pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas-Huriwai, Christopher. 2020. Ko Au Te Whenua, Ko Te Whenua Ko Au: I a the Land and the Land Is Me. In Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church. Edited by Hannah Malcolm. London: SCM Press, pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bray, Margaret, Amber Wutich, Kelli L. Larson, Dave D. White, and Alexandra Brewis. 2019. Anger and Sadness: Gendered Emotional Responses to Climate Threats in Four Island Nations. Cross-Cultural Research 53: 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, Robert, and Leslie Greenberg. 2021. Emotion-Focused Counselling in Action. Counselling in Action. Los Angeles: Sage Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Flothmann, Stefan. 2023. Anger Types. MindWorks Lab. Available online: https://mindworkslab.org/angermonitor/datahub/anger-types/ (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Francis, Pope. 2015. Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ of the Holy Father Francis: On Care for Our Common Home; Vatican. Available online: http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Fredericks, Sarah E. 2014. Online Confessions of Eco-Guilt. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 8: 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, Sarah E. 2021. Environmental Guilt and Shame: Signals of Individual and Collective Responsibility and the Need for Ritual Responses. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gelderman, Gabrielle. 2022. To Be Alive in the World Right Now: Climate Grief in Young Climate Organizers. Master’s thesis, St. Stephen’s College, Edmonton, AB, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, Robert, Karine Lacroix, and Angel Chen. 2018. Understanding Responses to Climate Change: Psychological Barriers to Mitigation and a New Theory of Behavioral Choice. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses. Edited by Susan D. Clayton and Christie M. Manning. Amsterdam: Academic Press, pp. 161–83. [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning, Chellis. 1994. My Name Is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization. Gabriola Island: New Catalyst Books. [Google Scholar]

- González-Hidalgo, Marien, and Christos Zografos. 2020. Emotions, Power, and Environmental Conflict: Expanding the ‘Emotional Turn’ in Political Ecology. Progress in Human Geography 44: 235–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good Grief Network. 2021. Available online: https://www.goodgriefnetwork.org/ (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Greenspan, Miriam. 2004. Healing Through the Dark Emotions: The Wisdom of Grief, Fear, and Despair. Boulder: Shambhala. [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen, Thea, Gisle Andersen, and Endre Tvinnereim. 2023. The Strength and Content of Climate Anger. Global Environmental Change 82: 102738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory J. Seigworth, eds. 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 2013. The Craft of Ritual Studies. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, Sami. 2021. We’re All Climate Hypocrites Now: How Embracing Our Limitations Can Unlock the Power of a Movement. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Jo. 2020. Emotional Methodologies for Climate Change Engagement: Towards an Understanding of Emotion in Civil Society Organisation (CSO)-Public Engagements in the UK. Ph.D. thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK. Available online: http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/95647/3/23861657_Hamilton_Thesis_Redacted.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Hamilton, Jo. 2022. ‘Alchemizing Sorrow Into Deep Determination’: Emotional Reflexivity and Climate Change Engagement. Frontiers in Climate 4: 786631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Experimental Futures. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hattam, Robert, and Michalinos Zembylas. 2010. What’s Anger Got to Do with It? Towards a Post-Indignation Pedagogy for Communities in Conflict. Social Identities 16: 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel-Robinson, Timothy. 2012. ‘The Fish of the Sea Perish’: Lamenting Ecological Ruin. Liturgy 27: 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, Caroline. 2020. We Need to (Find a Way to) Talk about … Eco-Anxiety. Journal of Social Work Practice 34: 411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, Caroline. 2023. Feeling Okay with Not Feeling Okay: Helping Children and Young People Make Meaning from Their Experience of Climate Emergency. In Holding the Hope: Reviving Psychological And Spiritual Agency in the Face Of Climate Change. Edited by Linda Aspey, Catherine Jackson and Diane Parker. Monmouth: PCCS Books, pp. 183–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, Caroline. 2024a. Climate Aware Therapy with Children and Young People to Navigate the Climate and Ecological Crisis. In Being a Therapist in a Time of Climate Breakdown. Edited by Judith Anderson, Tree Staunton, Jenny O’Gorman and Caroline Hickman. Oxon and New York: Routledge and CRC Press, pp. 111–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, Caroline. 2024b. Eco-Anxiety in Children and Young People – A Rational Response, Irreconcilable Despair, or Both? The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 77: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, Caroline, Elizabeth Marks, and Panu Pihkala. 2021. Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. Lancet Planetary Health 5: E863–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggett, Paul, and Rosemary Randall. 2018. Engaging with Climate Change: Comparing the Cultures of Science and Activism. Environmental Values 27: 223–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggett, Paul, ed. 2019. Climate Psychology: On Indifference to Disaster. Studies in the Psychosocial. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, Allan V., and Jerome C. Wakefield. 2007. The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow into Depressive Disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet, Jennifer. 2015. Is Shame Necessary? New Uses for an Old Tool. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jafry, Tahseen, ed. 2019. Routledge Handbook of Climate Justice. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Jamail, Dahr. 2019. End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Willis. 2013. The Future of Ethics: Sustainability, Social Justice, and Religious Creativity. Washington: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Tim. 2019. Ecologies of Guilt in Environmental Rhetorics. Palgrave Studies in Media and Environmental Communication. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Ayana Elizabeth, and Katharine K. Wilkinson, eds. 2020. All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis. New York: One World. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Trebbe. 2017. 101 Ways to Make Guerrilla Beauty. Grapevine: Radjoy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Trebbe. 2018. Radical Joy for Hard Times: Finding Meaning and Making Beauty in Earth’s Broken Places. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Hugh. 2020. Climate Grief—Climate Guilt. In Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church. Edited by Hannah Malcolm. London: SCM Press, pp. 126–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Owain, Kate Rigby, and Linda Williams. 2020. Everyday Ecocide, Toxic Dwelling, and the Inability to Mourn: A Response to Geographies of Extinction. Environmental Humanities 12: 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, Elin. 2020. Hope Matters: Why Changing the Way We Think Is Critical to Solving the Environmental Crisis. Vancouver and Berkeley: Greystone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kevorkian, Kristine A. 2004. Environmental Grief: Hope and Healing. Ph.D. thesis, Union Institute & University, Cincinnati, OH, USA. Available online: http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&res_dat=xri:pqdiss&rft_dat=xri:pqdiss:3134215 (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Kleres, Jochen, and Åsa Wettergren. 2017. Fear, Hope, Anger, and Guilt in Climate Activism. Social Movement Studies 16: 507–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knops, Louise. 2021. Stuck between the Modern and the Terrestrial: The Indignation of the Youth for Climate Movement. Political Research Exchange 3: 1868946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Køster, Allan, and Ester Holte Kofod, eds. 2022. Cultural, Existential and Phenomenological Dimensions of Grief Experience. Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, Charlie, and Panu Pihkala. 2022. Eco-Anxiety: What It Is and Why It Matters. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 981814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambelet, Kyle B. T. 2020. My Grandma’s Oil Well. In Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church. Edited by Hannah Malcolm. London: SCM Press, pp. 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- LaMothe, Ryan. 2016. This Changes Everything: The Sixth Extinction and Its Implications for Pastoral Theology. Journal of Pastoral Theology 26: 178–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMothe, Ryan. 2019. Giving Counsel in a Neoliberal-Anthropocene Age. Pastoral Psychology 68: 421–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMothe, Ryan. 2021. A Radical Pastoral Theology for the Anthropocene Era: Thinking and Being Otherwise. Journal of Pastoral Theology 31: 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMothe, Ryan. 2022. Pastoral Care in the Anthropocene Age: Facing a Dire Future Now. Emerging Perspectives in Pastoral Theology and Care. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- LaMothe, Ryan. 2024. Experiences of Beauty and Eco-Sorrow: Truths of the Anthropocene and the Possibility of Inoperative Care. Pastoral Psychology 73: 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmann, Helen, and Jascha Naumann. 2024. Being Positively Moved by Climate Protest Predicts Peaceful Collective Action. Global Environmental Psychology 2: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertzman, Renée Aron. 2015. Environmental Melancholia: Psychoanalytic Dimensions of Engagement. Hove and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Leukumaavaara, Jenni. 2019. Suomi on lukossa—miksi teeskentelemme, ettei tunteilla ole politiikassa ja elämässä väliä? Vihreä Lanka. Available online: https://www.vihrealanka.fi/juttu/suomi-on-lukossa-%E2%80%93-miksi-teeskentelemme-ettei-tunteilla-ole-politiikassa-ja-el%C3%A4m%C3%A4ss%C3%A4-v%C3%A4li%C3%A4.html (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Levine, Megan. 2017. It’s Ok That You’re Not Ok: Meeting Grief and Loss in a Culture That Doesn’t Understand. Boulder: Sounds True. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Michael. 2016. Self-Conscious Emotions: Embarrassment, Pride, Shame, Guilt, and Hubris. In Handbook of Emotions, 4th ed. Edited by Lisa Feldman Barrett, Michael Lewis and Jeannette Haviland-Jones. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 792–814. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jie, Magaret Stroebe, Cecilia L. W. Chan, and Amy Y. M. Chow. 2017. The Bereavement Guilt Scale: Development and Preliminary Validation. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying 75: 166–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jie, Margaret Stroebe, Cecilia L. W. Chan, and Amy Y. M. Chow. 2014. Guilt in Bereavement: A Review and Conceptual Framework. Death Studies 38: 165–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lifton, Robert Jay. 2017. The Climate Swerve: Reflections on Mind, Hope, and Survival. New York and London: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lomas, Tim. 2016. The Positive Power of Negative Emotions: How Harnessing Your Darker Feelings Can Help You See a Brighter Dawn. London: Piatkus. [Google Scholar]

- Macy, Joanna, and Molly Young Brown. 2014. Coming Back to Life: The Updated Guide to the Work That Reconnects. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, Hannah. 2020a. Grieving the Earth as Prayer. The Ecumenical Review 72: 581–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, Hannah. 2023. The Signifcance of Things: A Theological Account of Sorrow Over Anthropogenic Loss. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Theology and Religion, Durham University, Durham, NC, USA. Available online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/15237/ (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Malcolm, Hannah, ed. 2020b. Words for a Dying World: Stories of Grief and Courage from the Global Church. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, Michalina, Małgorzata Wierzba, Dominika Zaremba, Maria Kulesza, Jan Szczypiński, Bartosz Kossowski, Magdalena Budziszewska, Jarosław Michałowski, Christian Andreas Klöckner, and Artur Marchewka. 2023. Beyond Climate Anxiety: Development and Validation of the Inventory of Climate Emotions (ICE): A Measure of Multiple Emotions Experienced in Relation to Climate Change. Global Environmental Change 83: 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, Andrew, and Amanda Di Battista. 2017. Making Loss the Centre: Podcasting Our Environmental Grief. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief. Edited by Ashlee Cunsolo Willox and Karen Landman. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, pp. 227–57. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Elizabeth, and Caroline Hickman. 2023. Eco-Distress Is Not a Pathology, but It Still Hurts. Nature Mental Health 1: 379–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, Mari, Stephen Axon, Benjamin K. Sovacool, Siddharth Sareen, Dylan Furszyfer Del Rio, and Kayleigh Axon. 2020. Contextualizing Climate Justice Activism: Knowledge, Emotions, Motivations, and Actions among Climate Strikers in Six Cities. Global Environmental Change 65: 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, Pamela R. 2022. Embodying Theology: Trauma Theory, Climate Change, Pastoral and Practical Theology. Religions 13: 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, Karla. 2010. The Language of Emotions: What Your Feelings Are Trying to Tell You. Boulder: Sounds True. [Google Scholar]

- McNish, Jill L. 2010. Shame and Guilt. In Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. Edited by David A. Leeming, Kathryn Madden and Stanton Marlan. Springer Reference. New York: Springer, pp. 874–75. [Google Scholar]

- McRae, Emily. 2018. Anger and the Oppressed: Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Perspectives. In Moral Psychology of Anger. Edited by Myisha Cherry and Owen Flanagan. Moral Psychology of the Emotions Volume 4. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 105–21. [Google Scholar]

- Meloche, Katherine. 2018. Mourning Landscapes and Homelands: Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Peoples’ Ecological Griefs. Canadian Mountain Network Website. August 30. Available online: https://www.canadianmountainnetwork.ca/blog/indigenous-and-non-indigenous-peoples-ecological-griefs (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Menning, Nancy. 2017. Environmental Mourning and the Religious Imagination. In Mourning Nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss & Grief. Edited by Ashlee Cunsolo Willox and Karen Landman. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mihai, Mihaela. 2024. Representing Ecological Grief. Polity 56: 359–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, Mihaela, and Mathias Thaler. 2023. Environmental Commemoration: Guiding Principles and Real-World Cases. Memory Studies, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Andy. 2023. Climate Crisis as Emotion Crisis: Emotion Validation Coaching for Parents of the World. In Holding the Hope: Reviving Psychological And Spiritual Agency in the Face Of Climate Change. Edited by Linda Aspey, Catherine Jackson and Diane Parker. Monmouth: PCCS Books, pp. 213–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mkono, Mucha, Karen Hughes, and Stella Echentille. 2020. Hero or Villain? Responses to Greta Thunberg’s Activism and the Implications for Travel and Tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 28: 2081–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe-Lobeda, Cynthia D. 2013. Resisting Structural Evil: Love as Ecological-Economic Vocation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, Julia, and Kirsti M. Jylhä. 2022. How to Feel About Climate Change? An Analysis of the Normativity of Climate Emotions. International Journal of Philosophical Studies 30: 357–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, Karen. 2019. Learning from Young People Engaged in Climate Activism: The Potential of Collectivizing Despair and Hope. Young 27: 435–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckel, Sighard, and Martina Hasenfratz. 2021. Climate Emotions and Emotional Climates: The Emotional Map of Ecological Crises and the Blind Spots on Our Sociological Landscapes. Social Science Information 60: 253–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, Robert A. 2019. Meaning Reconstruction in Bereavement: Development of a Research Program. Death Studies 43: 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, Robert A., and Laurie A. Burke. 2015. Loss, Grief, and Spiritual Struggle: The Quest for Meaning in Bereavement. Religion, Brain & Behavior 5: 131–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, Robert A., ed. 2016. Techniques of Grief Therapy: Assessment and Intervention. Series in Death, Dying, and Bereavement; New York: Routledge and Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer, Robert A., ed. 2022. New Techniques of Grief Therapy: Bereavement and Beyond. Death, Dying, and Bereavement. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholsen, Shierry Weber. 2002. The Love of Nature and the End of the World: The Unspoken Dimensions of Environmental Concern. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Rikke Sigmer, Christian Gamborg, and Thomas Bøker Lund. 2024. Eco-Guilt and Eco-Shame in Everyday Life: An Exploratory Study of the Experiences, Triggers, and Reactions. Frontiers in Sustainability 5: 1357656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, Magdalena, and Steven Vertovec. 2014. Comparing Convivialities: Dreams and Realities of Living-with-Difference. European Journal of Cultural Studies 17: 341–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dell-Chaib, Courtney. 2019. Desiring Devastated Landscapes: Love After Ecological Collapse. Syracuse University. Available online: https://surface.syr.edu/etd/1045/ (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Ojala, Maria, Ashlee Cunsolo, Charles A. Ogunbode, and Jacqueline Middleton. 2021. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46: 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oziewicz, Marek. 2024. Beyound the Accountability Paradox: Climate Guilt and the Systemic Drivers of Climate Change. In The Existential Toolkit for Climate Justice Educators: How to Teach in a Burning World, 1st ed. Edited by Jennifer Atkinson and Sarah Jaquette Ray. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 210–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth, Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa M. Perez. 2000. The Many Methods of Religious Coping: Development and Initial Validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 519–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., ed. 2013. APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. APA Handbooks in Psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, Sarah. 2021. ‘You Are Stealing Our Future in Front of Our Very Eyes.’ The Representation of Climate Change, Emotions and the Mobilisation of Young Environmental Activists in Britain. E-Rea. Revue Électronique d’études Sur Le Monde Anglophone 18: 11774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2016. The Pastoral Challenge of the Eco-Reformation: Environmental Anxiety and Lutheran ‘Eco-Reformation’. Dialog: A Journal of Theology 55: 131–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2018. Eco-anxiety, Tragedy, and Hope: Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions of Climate Change. Zygon 53: 545–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2020a. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability 12: 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2020b. Eco-Anxiety and Environmental Education. Sustainability 12: 10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2022a. Eco-Anxiety and Pastoral Care: Theoretical Considerations and Practical Suggestions. Religions 13: 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2022b. The Process of Eco-Anxiety and Ecological Grief: A Narrative Review and a New Proposal. Sustainability 14: 16628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2022c. Toward a Taxonomy of Climate Emotions. Frontiers in Climate 3: 738154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2024a. Climate Anxiety, Maturational Loss and Adversarial Growth. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 77: 369–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2024b. Climate Sorrow: Discerning Various Forms of Climate Grief and Responding to Them as a Therapist. In Being a Therapist in a Time of Climate Breakdown. Edited by Judith Anderson, Tree Staunton, Jenny O’Gorman and Caroline Hickman. Oxon and New York: Routledge and CRC Press, pp. 157–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2024c. Definitions and Conceptualizations of Climate Distress: An International Perspective. In Climate Change and Youth Mental Health: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Elizabeth Haase and Kelsey Hudson. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2024d. Ecological Sorrow: Types of Grief and Loss in Ecological Grief. Sustainability 16: 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2024e. Ecological Grief, Religious Coping, and Spiritual Crises: Exploring Eco-Spiritual Grief. Pastoral Psychology, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, Panu. 2024f. Working with Ecological Emotions: Mind Map and Spectrum Line. In The Existential Toolkit for Climate Justice Educators: How to Teach in a Burning World, 1st ed. Edited by Jennifer Atkinson and Sarah Jaquette Ray. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 123–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, Sarah M. 2016. Mourning Nature: The Work of Grief in Radical Environmentalism. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 10: 419–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Russell C. 2019. Shame, Moral Motivation, and Climate Change. Worldviews 23: 230–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prade-Weiss, Juliane. 2021. For Want of a Respondent: Climate Guilt, Solastalgia, and Responsiveness. The Germanic Review 96: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigerson, Holly G., M. Katherine Shear, and Charles F. Reynolds. 2022. Prolonged Grief Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—Helping Those With Maladaptive Grief Responses. JAMA Psychiatry 79: 277–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomska, Marietta. 2023. Ecologies of Death, Ecologies of Mourning: A Biophilosophy of Non/Living Arts. Research in Arts and Education 2: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, Tamasin, and Lenore Manderson. 2011. Resilience, Spirituality and Posttraumatic Growth: Reshaping the Effects of Climate Change. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities. Edited by Inka Weissbecker. International and Cultural Psychology. New York: Springer, pp. 165–84. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, Rebecca. 2023. Do ‘Forest Funerals’—and Other Rituals—Help Climate Anxiety? Sojourners. Available online: https://sojo.net/articles/do-forest-funerals-and-other-rituals-help-climate-anxiety (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Randall, Rosemary. 2009. Loss and Climate Change: The Cost of Parallel Narratives. Ecopsychology 1: 118–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, Matthew. 2022. Grief Worlds: A Study of Emotional Experience. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Sarah Jacquette. 2020. A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, Tess. 2017. Just 100 Companies Responsible for 71% of Global Emissions, Study Says. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2017/jul/10/100-fossil-fuel-companies-investors-responsible-71-global-emissions-cdp-study-climate-change (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Rinofner-Kreidl, Sonja. 2016. On Grief’s Ambiguous Nature. Quaestiones Disputatae 7: 178–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, Margaret Klein. 2020. Facing the Climate Emergency: How to Transform Yourself with Climate Truth. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sangervo, Julia, Kirsti M. Jylhä, and Panu Pihkala. 2022. Climate Anxiety: Conceptual Considerations, and Connections with Climate Hope and Action. Global Environmental Change 76: 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santmire, H. Paul. 1985. The Travail of Nature: The Ambiguous Ecological Promise of Christian Theology. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sasser, Jade S. 2023. At the Intersection of Climate Justice and Reproductive Justice. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Climate Change 15: e860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Laura. 2023. How to Live in a Chaotic Climate 10 Steps to Reconnect with Ourselves, Our Communities, and Our Planet. New York: Shambhala New York. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Casey R. 2019. Scapegoat Ecology: Blame, Exoneration, and an Emergent Genre in Environmentalist Discourse. Environmental Communication 13: 152–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrell, Daniel. 2021. Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of the World. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Wonchul. 2020. Reimagining Anger in Christian Traditions: Anger as a Moral Virtue for the Flourishing of the Oppressed in Political Resistance. Religions 11: 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotwell, Alexis. 2016. Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skrimshire, Stefan. 2019. Extinction Rebellion and the New Visibility of Religious Protest. Open Democracy. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/transformation/extinction-rebellion-and-new-visibility-religious-protest/ (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Smith, Laura. 2014. On the ‘Emotionality’of Environmental Restoration: Narratives of Guilt, Restitution, Redemption and Hope. Ethics, Policy & Environment 17: 286–307. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Robert C. 2004. On Grief and Gratitude. In In Defense of Sentimentality. Edited by Robert C. Solomon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 75–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Robert C., and Lori D. Stone. 2002. On ‘Positive’ and ‘Negative’ Emotions. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 32: 417–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, Amia. 2018. The Aptness of Anger. The Journal of Political Philosophy 26: 123–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Samantha, Zoe Leviston, Teaghan Hogg, and Iain Walker. 2023. Anger about Climate Inaction: The Content of Eco-Anger Shapes Emotional and Behavioral Engagement with Climate Change. Preprint. June. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, Storm. 2020. Climate Change and Pastoral Theology. In T&T Clark Handbook of Christian Theology and Climate Change. Edited by Ernst M. Conradie and Hilda P. Koster. London: T&T Clark, pp. 615–26. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Bron Raymond. 2016. The Greening of Religion Hypothesis (Part One): From Lynn White, Jr. and Claims That Religions Can Promote Environmentally Destructive Attitudes and Behaviors to Assertions They Are Becoming Environmentally Friendly. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 10: 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Bron Raymond, Jeffrey Kaplan, Laura Hobgood-Oster, Adrian J. Ivakhiv, and Michael York, eds. 2005. The Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Sarah McFarland. 2019. Ecopiety: Green Media and the Dilemma of Environmental Virtue. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Anglican Church of Australia. n.d. Environmental Degradation and Pollution Prayer. The Anglican Church of Australia Website. Available online: https://acen.anglicancommunion.org/media/61498/Environmental-degradation-and-pollution-prayer.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Tschakert, Petra, Neville R. Ellis, C. Anderson, A. Kelly, and J. Obeng. 2019. One Thousand Ways to Experience Loss: A Systematic Analysis of Climate-Related Intangible Harm from around the World. Global Environmental Change 55: 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, Tori. 2023. It’s Not Just You: How to Navigate Eco-Anxiety and the Climate Crisis. London: Gallery Books UK London. [Google Scholar]

- Varutti, Marzia. 2023. Claiming Ecological Grief: Why Are We Not Mourning (More and More Publicly) for Ecological Destruction? Ambio 53: 552–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verlie, Blanche. 2022. Learning to Live with Climate Change: From Anxiety to Transformation. Routledge Focus. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Verlie, Blanche. 2024. A pedagogy for emotional climate justice. In The Existential Toolkit for Climate Justice Educators: How to Teach in a Burning World, 1st ed. Edited by Jennifer Atkinson and Sarah Jaquette Ray. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Voşki, Anaïs, Gabrielle Wong-Parodi, and Nicole M. Ardoin. 2023. A New Planetary Affective Science Framework for Eco-Emotions: Findings on Eco-Anger, Eco-Grief, and Eco-Anxiety. Global Environmental Psychology 1: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Frances. 2020. Like There’s No Tomorrow: Climate Crisis, Eco-Anxiety and God. Durham: Sacristy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wardell, Susan. 2020. Naming and Framing Ecological Distress. Medicine Anthropology Theory 7: 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Jack Adam. 2020. Climate Cure: Heal Yourself to Heal the Planet. Woodbury: Llewellyn Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Weintrobe, Sally. 2021. Psychological Roots of the Climate Crisis: Neoliberal Exceptionalism and the Culture of Uncare. New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, Francis. 2015. The Wild Edge of Sorrow: Rituals of Renewal and the Sacred Work of Grief. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh, Lorraine, Lois Player, Angelica Jiongco, Melissa James, Marc Williams, Elizabeth Marks, and Patrick Kennedy-Williams. 2022. Climate Anxiety: What Predicts It and How Is It Related to Climate Action? Journal of Environmental Psychology 83: 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, Kyle Powys. 2017. Is It Colonial Déjà vu? Indigenous Peoples and Climate Injustice. In Humanities for the Environment: Integrating Knowledge, Forging New Constellations of Practice. Edited by Joni Adamson and Michael Davis. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 88–104. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315642659-15/colonial-d%C3%A9j%C3%A0-vu-indigenous-peoples-climate-injustice-kyle-powys-whyte (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Willox, Ashlee Cunsolo. 2012. Climate Change as the Work of Mourning. Ethics & the Environment 17: 137–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman, John. 2021. Hope and Courage in the Climate Crisis: Wisdom and Action in the Long Emergency. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan Cham. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, J. William. 2018. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner, 5th ed. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Work That Reconnects Network. 2024. Available online: https://workthatreconnects.org/ (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Wray, Britt. 2022. Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Crisis. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Emily (Em). 2024. Building Somatic Awareness to Respond to Climate-Related Trauma. In The Existential Toolkit for Climate Justice Educators: How to Teach in a Burning World, 1st ed. Edited by Jennifer Atkinson and Sarah Jaquette Ray. Oakland: University of California Press, pp. 133–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wullenkord, Marlis, Josephine Tröger, Karen Hamann, Laura Loy, and Gerhard Reese. 2021. Anxiety and Climate Change: A Validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale in a German-Speaking Quota Sample and an Investigation of Psychological Correlates. Climatic Change 168: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, Michalinos. 2007. Mobilizing Anger for Social Justice: The Politicization of the Emotions in Education. Teaching Education 18: 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, Michalinos. 2021. Encouraging Moral Outrage in Education: A Pedagogical Goal for Social Justice or Not? Ethics and Education 16: 424–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillman, Dolf. 1996. Sequential Dependencies in Emotional Experience and Behavior. In Emotion: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Robert D. Kavanaugh, Betty Zimmerberg and Steven Fein. Mahwah: L. Erlbaum Associates, pp. 243–72. [Google Scholar]

| RAIN (Brach 2019) | Seven Steps of Emotional Alchemy (Greenspan 2004) |

|---|---|

| Recognize | 1. Intention: Focusing your spiritual will |

| Allow | 2. Affirmation: Developing an emotion-positive attitude |

| Investigate | 3. Bodily sensation: Sensing, soothing, and naming emotions |

| Nurture | 4. Contextualization: Telling a wider story |

| 5. The way of non-action: Befriending what hurts | |

| 6. The way of action: Social action and spiritual service | |

| 7. Transformation: The way of surrender (flow) |

| Task |

|---|

| 1. Working with one’s own emotions 2. Exploring the various forms and dynamics of climate emotions 3. Contextualizing climate emotions in the community 4. Supporting constructive engagement with climate emotions via various methods (e.g., action, rituals, spiritual practices) |

| Multispecies Justice |

| Responsibility |

| Pluralism |

| Dynamism |

| Anticlosure |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pihkala, P. Engaging with Climate Grief, Guilt, and Anger in Religious Communities. Religions 2024, 15, 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091052

Pihkala P. Engaging with Climate Grief, Guilt, and Anger in Religious Communities. Religions. 2024; 15(9):1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091052

Chicago/Turabian StylePihkala, Panu. 2024. "Engaging with Climate Grief, Guilt, and Anger in Religious Communities" Religions 15, no. 9: 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091052

APA StylePihkala, P. (2024). Engaging with Climate Grief, Guilt, and Anger in Religious Communities. Religions, 15(9), 1052. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091052