1. Introduction

Prof. Dr. Keul is an associate professor of fundamental theology and comparative religious studies at the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg. Her research focuses on two subjects: Christian mysticism, especially as it relates to the poverty movement in the 13th century, and vulnerability as a form of power in migration debates, religious–political violence and the fight against poverty. She currently conducts the research project “Vulnerabilities. A Heterology of Incarnation in the Vulnerability Discourse” at the abovementioned university. She articulates her findings, among other sources, in her books Schöpfung durch Verlust, parts 1 and 2 (

Keul 2021a,

2021b)

1.

It is in reading these that one creative, but disturbing and easily misunderstood, insight comes to the fore, namely: the profane and the sacred have, and share, power that has the possibility to unleash destructive violence or freely share the overflowing gifts of life. Both hinge on sacrifice and are responses to inescapable vulnerability.

Pondering this from the question of the lived reality of abuse and cover-up in the Church helps to clarify one element that tends to be ignored in research and rapports on this topic. It is that of how the Church does or does not respond to the painful reality of covering up abuse and, more profoundly, what it is actually responding to. This paper is an exercise in excavating some possibilities that might increase insight into what a response that is in tune with the whole raison d’être of the Church—the incarnation—might look like.

It explores the proposal that

what the Church and other institutional systems are responding to is, perhaps surprisingly, vulnerability. Not as it is projected on others, but as inherent in all that is human. Keul represents vulnerability, perhaps counter-intuitively, as “…an unprecedented power in personal and political, social and cultural, and not least in religious life. Biological bodies are vulnerable, but so are urban, state, and religious bodies. How human communities deal with this vulnerability is a socially relevant and at the same time precarious topic” (

Keul 2021a, p. 1)

2.

Exploring the meaning of this precarious topic and bringing it into a fiduciary, heterological conversation with other sources will be done through the theoretical model of the Research Group for Safeguarding in the Church (

Vandewiele and Servaas 2024). This model came into being largely because of the work done by Keul. Her heterological approach gave the input and inspiration to build on the four elements that are continually addressed in her thinking: community, spirituality (the sacred), the institutional system and, of course the central piece of her research, vulnerability.

2. Vulnerability, Wounds and a Profane Response to the Sacred

When the word ‘vulnerability’ is dropped, the general, mostly passive and conceptual, assumption is that it pertains to particular groups or communities perceived as having less privilege, a smaller chance at succeeding in life or that are more prone to specific threats. For Keul, vulnerability refers to the ability of all people to receive and inflict wounds. It is not so much a concept or a noun to be applied, but a reality that triggers, mostly unconscious, forceful actions and reactions, beginning, but not coinciding, with wounds. This is an important distinction to make because it demonstrates the link between vulnerance, violence and wounds.

Though wounds are the result of some form of intentional or unintentional violence, nevertheless as soon as they are inflicted, they belong to the past. It is in their effects that they emanate ongoing power. This is what makes them dangerous. They “change the way we look at the future and thus exert a power on the present. They show that and how vulnerable you are as a human being. If you have experienced violence by another person, then you expect to be attacked again and weakened again in the future. It’s intimidating and frightening” (

Keul 2021a, p. 321)

3. Keul’s remark may seem exaggerated, yet it is backed up by trauma studies and recent discoveries in neurobiology. Violence does something to our bodies and brains. It makes us more alert and wary, especially if it cannot be processed in safe and secure places. This can be seen on micro and macro levels. A child, for example, that was stung by a wasp will be wary of all insects for a while. In a similar way, if a Jewish cemetery was vandalized by an extremist, the whole community will close in on itself, etc. The main point Keul is making is that wounds, and being wounded,

through violence cannot be prevented and that when it happens, the tendency is to anticipate the future more negatively. Therefore, the most logical and immediate response is to focus on making our family, group, religion and/or society as invulnerable and thus wound-free as possible. To achieve this, protocols, rules and regulations, an impressive number of insurances, ever-increasing levels of security, and strong boundaries are gathered and imposed. This almost endless and frantic accumulation of protective measures and their organization is what Keul calls the profane. It is what makes the secular world ‘the preferred area of humanity’: one feels safe, protected, because the dangers of life are contained. Therefore, it appears to be easier to live in the secular world (

Keul 2021a, pp. 178–79;

Bataille 1997, p. 33)

4. That Keul, following Bataille, uses the word ‘secular’ does not mean she suggests that there is another, perhaps spiritual, world. The point she is making, as will become clearer below, is that the desire to be wound-free partners with distrust of all that cannot be predicted. It is akin to what Hartmut Rosa identifies as a society that has lost its listening heart, which he interprets as the sense of the transcendent held in the reservoir of religion. It is humanity “desperately searching for an alternative form of relation to the world, of

being-in-the-world” (

Rosa 2024, p. 11). Put differently, Keul does not place the profane or the secular as being the opposite of the sacred or the religious. She interprets it as a human tendency to become wary of the adventure of life itself. The profane is the attempt to bring order. It becomes stifling if it is not matched, questioned or corrected by the sacred.

One of the most defining elements of the profane is that, due to its underlying presumption that wounds can be prevented, it is future-oriented. It cannot be an end in itself, nor can it be

present to the present. This contributes to the strange sense that though accumulating protocols, rules and regulations satisfies, it also creates a general feeling of emptiness, of malaise. It tires us because “[A]ccumulation requires safeguarding enlargement, and that means armor and walls that reinforce demarcation and lock people in the discontinuity of the profane” (

Keul 2021b, p. 268)

5. This understanding of the profane being ultimately stifling runs parallel to Rosa, where he speaks of late modern society as being at a

frenetic standstill. On the one hand, it is accelerating, but on the other, it has become bogged down. Such a society, he states, is “in the mode of dynamic stabilization”. Permanently “forced to grow, accelerate, push things forward, produce innovation after innovation, and more or less strive for disruptive change”. Rosa connects this to the loss of historical momentum and, ultimately, the absence of wisdom that can be found in experiencing the world as meaningful (

Rosa 2024, p. 4).

Where Rosa brings in religion, Keul dives into an analysis of the sacred which, she writes, “contrasts with ‘the world of the profane, where everything is purposeful, where rationality and concern for the future are in charge, where strategies of protection and security preserve possession, this intimacy, the intimate connection with all living things, is lost. But there are moments that fall out of the time when this intimacy of life occurs. They belong to the world of the sacred, where only the present counts” (

Keul 2021b, p. 75)

6. This presence of the sacred is not necessarily related to religion nor is it an alternative to the profane. Keul uses it in the sense of something unfathomable that gives human beings and communities an experience of mystery or wonder. Referring to Georges Bataille, Keul writes: “It can be a religious community experience, but it can also be an imminent birth or falling in love or the super kick in high-risk sports”. At the same time, it can be located “in the transgression of prohibitions, which opens up ‘intimacy’. The sacred has an irresistible but at the same time panic-inducing attraction because it entices with the promise that life in its intimacy opens up here” (

Keul 2021a, p. 198)

7. It is not tame, but related to the tenderness and intensity of life, unpredictable and terrifying, profoundly attractive and ungraspable. Yet, it wanders in and belongs to ordinary experiences. When confronted with it, we cannot but respond. Its ambivalent, potentially explosive, nature belongs to the whole of humanity. Where the profane seeks to bring order and control, the sacred is actually a reminder of life as being overflowing, passionate, awesome and uncontrollable. The experience of the sacred questions our profane attempts at certainty. Therefore, the profane is wary of the sacred and, in a sense, seeks to domesticate it. Here, a first paradoxical element rears its head. Because it is precisely that which human beings consider sacred that the profane seeks to protect, the profane needs it. Concurrently, it resents the sacred because of its capacity to wound. It is, for that reason, a servant of the sacred. Not a comfortable position, but one that shows how the two cannot be separated, but also that—ultimately and analogically—the energy that the sacred exudes will disrupt the profane because the aim of the profane to be invulnerable is utopian. Humanity cannot become wound-free.

Theologian John Henry Newman would most likely reason that the concept of invulnerability belongs to the notional, rather than the real. It may be a good idea with a level of truthfulness to it and even sound reasonable, but if it is not connected to concrete experience (which is in the present and thus connected to the sacred), it cannot stand (

Newman 2005). This is true, especially as the one wound we fear the most cannot be avoided at all: the wound of death. This deepest wound is what humanity fears the most, feeding the desire to reach the furthest point away from it. In his book

The Guide to Gethsemane, Emmanuel Falque puts it succinctly when he writes: “The ordeal of death, from sickness to death, grips humanity, as Emmanuel Levinas says, in an ‘impossibility of retreat.’ There are no exemptions; and if we try to claim exemption, we risk lying to ourselves about the burden of what is purely and simply our humanity” (

Falque 2019, p. xviii). This connects to what Keul writes: “But no matter how much you protect yourself; wounds will not be absent. There is always an end to life, and there lurks the greatest possible wound of all: death, which is certain to occur in every life. This is a paradox, especially in the life of a society that relies more and more on security: the only security in life is death, which is ‘impossible’ from the point of view of the individual” (

Keul 2021a, p. 318)

8.

The profane possesses another paradoxical element, though, one that highlights the precarious relationship with the sacred: they both hinge on sacrifices. “[O]n the one hand, people and their communities show a great willingness in everyday life and in disasters to support each other in the vulnerabilities of life, to stand by each other. On the other hand, however, they often protect themselves and what they consider their own by resorting to safety measures that expose others to vulnerability. It creates a potential for violence that is at work in many places, including in the fields of global biopolitics” (

Keul 2021a, p. 1)

9. The surprising element for the profane is that human beings are not totally committed to being or becoming wound-free. On the contrary, the willingness to suffer wounds and to inflict them on others, is undeniable. One obvious example that Keul uses is that of suicide bombers and how they can be viewed as heroes or even saints. Building walls to keep out asylum seekers is another illustration of the same principle, as is the sudden violence towards previously respected and befriended neighbors because they belong to another ethnic group or religion. Why is this? Or what is it that causes human beings and communities to voluntarily become vulnerable? Keul understands this as being rooted in the aversion of being wounded combined with the desire to hold on to and defend that which is considered to be sacred. This strange combination leads to spirals of violence full of explosive power. She writes: “Becoming vulnerable in order to protect or increase one’s own life resources is always a possibility of being human. But it leads into spirals of violence that cannot be controlled due to their explosive power and can have devastating effects. This is illustrated by the vulnerability paradox, which states that the more security and protection strategies are installed beforehand, the greater the damaging effects in the event of damage. The fact that these damaging effects often hit those hardest who had not previously benefited from the protection strategies raises a problem of justice that reinforces the problem of vulnerability” (

Keul 2021b, p. 194)

10.

What the profane aims at paradoxically shows that the more

invulnerable we attempt to be, the more

vulnerant (causing of wounds) we become; this both towards ourselves, communities, groups and nations and towards others. Becoming vulnerant in order to protect is a form of power and violence. Ute Leimgruber, following Keul, puts it clearly when she says: “While ‘vulnerability’ means a possible injury that may or may not happen and that can possibly be averted, ‘vulnerance’ means the special readiness to use violence in connection with vulnerabilities” (

Leimgruber 2022, p. 256). ‘What they consider their own’ is related to what is experienced or declared to be ‘sacred’. The more ‘sacred’ something is, the more willing people are to make sacrifices even if this means encroaching on the vulnerability of others or themselves. Vice versa: “the more sacrifices, the more what is sacrificed for becomes sacred” (

Keul 2021a, p. 362)

11. Thus, both the sacred and the profane are linked to violence and the pressure, internal and external, to sacrifice.

3. The Roman Catholic Church, Fear and the Desire to Protect

This interaction can be clearly seen in the response to the abuse and, even more so, its cover-up, in the RCC. What was this response of cover-up to? From the perspective of vulnerability and vulnerance, the answer lies in the feared wound and in the desire to protect that which is considered sacred. The RCC did not respond to the lived reality of abuse in se but to what this would cost in terms of loss of symbolic, social and economic power. The wounds caused by those who were abused could, therefore, not be exposed as they would increase the possibility of crushing that which the Church considers to be sacred. Therefore, the whole, often unconscious, tendency was to rush and seek to protect ‘the sacred’—sidestepping the theological question whether the sacred in itself can, or cannot, be destroyed. Vulnerance became active and sacrifices were asked for, hence the willingness to use passive and active violence by way of the sacred.

To understand Keul’s reasoning here, it is important to consider Roman Catholic theology where the term ‘sacrifice’ has its own particular interpretation with respect to Christ. Jesus of Nazareth freely chose to offer his body for the sake of human salvation and redemption. It was, as will be seen later, integrated in his lived commitment to radical vulnerability and total incarnation. Humanity, however, turned him into a victim by imposing suffering and death on him. Where Christ gave himself to bring eternal freedom to humanity, the world and the cosmos, human beings sacrificed (or victimized) him to protect what was sacred to them. Christ could have refused this, but that would have been in conflict with his peaceful and ongoing self-giving even while suffering. Not understanding the subtle but important distinction between sacrifice out of choice and being sacrificed in order to protect what is seen to be sacred contributes to one of the most devastating mechanisms in cover-up and that is the use of vulnerance.

In cover-up, people who were wounded through abuse became victims who were sacrificed (victimized) to protect what was understood to be sacred, to keep, as Rosa would say, the status quo. To enable this, Christian concepts like dying to oneself, suffering for Christ or even the demand to be graceful towards the perpetrator (as this is what Christian forgiveness looks like) were and are carefully applied. It helped, and helps, to maintain a culture of silence. Victimizing all that stands in the way of protecting the sacred was, and is, carried by the conviction that suffering pain—even when due to abuse—is an opportunity to grow in holiness. This is, though, not what Christ did. He did not die to become holy, nor did He glorify suffering. He gave himself in and through the profound love that kept him in total dependency of God whom he called Father, and this brought redemption. He never asked to suffer but accepted it in trust. Sacrificing those who are hurt and demanding of others that they forego the search for truth, transparency, justice and protection can never be considered as good. Yet, in the mechanism of cover-up, it was used this way. Suffering, profoundly misunderstood as being like Christ, became glorified. Here, abuse meets cover-up, and one amplifies the other “dealing immeasurable damage to survivors and non-survivors” (

Keul 2022).

One particularly pungent side of this is that many of those who were victimized or were affected by it indirectly accepted this and went along with the practice of vulnerance. They kept silent because being traumatized, or suffering from secondary traumatic stress, made them feel profoundly ashamed. Alongside this, they had fostered or been formed into believing that following Christ meant surrendering to pain and humiliation which, unconsciously, became confused with humility. The loss of self, the sense of guilt and shame, already destructively present in those who are traumatized, only became stronger. When vulnerance is applied, freedom decreases and salvation is confused with the practice of spiritual bypassing: the hiding behind spiritual beliefs, albeit wrongly formed, in order to avoid the pain and actual suffering that needs to be faced.

An example of where the power of vulnerability and its call for sacrifice is subtly at work can be found in one of the documents connected to the special parliamentary commission that investigated the handling of clergy sexual abuse of minors in the Roman Catholic Church in Belgium (2023/2024). In this, the director of the interdiocesan youth service states: “[y]oung people want to be the engine of the ongoing transition to an open Church. In such a Church, there is no place for pretenders and hypocrites. Those people we will help chase away” (

Van Ussel 2024)

12. These words exemplify the tone of the whole document. The content of this contribution can be critiqued for not reflecting sufficient understanding of the complexity of traumatic experiences and the absence of the aspect of cover-up. Moreover, the document reveals insufficient awareness of the variety of roles human beings can and do play and of the intricate and hybrid relationship of trauma and personal identity. More relevant for Keuls thought, though, is what the words ‘chasing away’ are revealing. At their core lies a desire to prevent potential wounds. In order to do this, a sacrifice is demanded. Some people—hypocrites and pretenders—need to be removed for the sake of protecting the possibility of an open Church. This, alongside the desire of younger people to be involved in change, is where the sacred, and with it vulnerance, enters. The intuitions this document reveals are understandable, especially in a Western context where abuse is seen as a problem to be solved from the perspective of avoiding future wounds and not a lived reality to be approached with wisdom, self-reflection and caution. Yet, they are rooted in a more profane than sacred understanding of safeguarding. Moreover, as shown in the research carried out by Keul, vulnerability does not lie solely with a special group of people who are detested by society (like, in this case, perpetrators of child abuse, hypocrites and pretenders) and on that basis excluded as much as possible. Bataille makes us face ourselves rather sharpy when he says: “We cannot be human until we have perceived in ourselves the possibility for abjection in addition to the possibility for suffering. We are not only possible victims of the executioners; the executioners are our fellow creatures. We must ask ourselves: is there anything in our nature that renders such horror impossible? And we would be correct in answering: no, nothing. A thousand obstacles in us rise against it.... Yet it is not impossible. Our possibility is thus not simply pain, it extends to the rage of the torturer” (

Keul 2021a, p. 224;

Bataille and Rottenberg 2008)

13.

Thus, applying the paradox of vulnerability to the Church’s response as the use of vulnerance becomes clear: fear of an anticipated wound and the desire to escape from vulnerability, combined with a desire to protect what is deemed sacred and thus to sacrifice, actually leads to more vulnerability and the pressure to become vulnerant. “In the end, what was initially intended as self-protection turns out to be self-destruction”, and, “[T]he vulnerance generated in the system became volatile and targeted the system itself” (

Keul 2022). In this way, the power of the appeal of the sacred reveals its destructive side.

There is, though, another way to look at this desire to protect what we hold as sacred, one that can help to connect vulnerability to avoiding not only potential wounds but also shock and loss. We do not only want to avoid wounds that are the result of violence, we are also afraid of losing something we hold dear, experiences that were good and life-giving, ideas that caught our imagination. Put differently, protection is related to holding onto something because it represents experience. It is relational, not objective. Moreover, it can be applied to a whole community. In his book

An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent (

Newman 2005), Newman puts forward an impressive argument for how human beings come to convictions and, ultimately, faith. He relates this to the dynamic movement between, on the one hand, reasoning, and the gathering of intellectual truths (the illative sense), and, on the other, the imagination. It is this latter that is expedient for understanding how this can contribute to the willingness to sacrifice through vulnerance. Newman explains how it is through the imagination that things become real, and thus personal, to us. It is a habit of mind and pre-reflective, closer to feeling than to seeing. When images are presented to our mind—through our senses but not limited to them—they affect us in such a way that we can imagine a place we never visited or construct vivid pictures in our mind of things we are unfamiliar with. The more concrete something we experience is, the more we experience it as real and the bigger the impact it has on us. This evokes a power in us that makes us respond because we care. “The heart is commonly reached, not through reason, but through the imagination, by means of direct impressions, by the testimony of facts and events, by history, by description”, he writes. However, it is not the imagination itself that causes us to act, “but hope and fear, likes and dislikes, appetite, passion, affection, the stirrings of selfishness and self-love. What the imagination does for us is to find a means of stimulating those motive powers and it does so by providing a supply of objects strong enough to stimulate them” (

Newman 2005, pp. 84–85). Newman relates this to the experience of the whole Church where Christ imprinted “the Image or idea of Himself in the minds of his subjects individually; and that Image, apprehended and worshipped in individual minds, becomes a principle of association, and a real bond of those subjects one with another, who are thus united to the body by being united to that Image” Put differently: that which the Church held and continues to hold sacred is also what holds the Church together in a community dedicated to him. Thus, the imagination is a communal form of experiencing what is deemed to be sacred as real or personal.

The imagination, though, is, perhaps surprisingly, conservative for the simple reason that we tend to trust our experience and are wary of new ideas. Because of the imagination, we can actually accept the irrational act of cover-up because to question the Church or to detect the work of vulnerance is too big a shock to the imagination. It is easier to trust the Church we know, the images we cherish—that which we consider to be sacred—and our experience than to face the need for new images, other experiences. It is also what makes us look for images that confirm the ones we have and to avoid the ones that question our experience.

4. The Power and Other Power of the Sacred

One image that has the capacity to reverse the violence of vulnerance and break the imagination open to new ways of sensing and responding is the one moved by an other-power, firmly situated in the wound that “brings to light the reality that life needs death and lives from the expenditure of life. In this respect, the wound falsifies the utopia of invulnerability. It breaks through and shatters the world of the profane, which, with its strategies of protection and defense, builds up the utopia that invulnerability could be achieved, at least approximately, in human life” (

Keul 2021a, p. 326)

14. Here, vulnerability comes in as not only “that unheard-of power at work that sets dangerous safety measures in motion; it is also a life force that releases creativity by taking risks for others and that allows strength to grow from the weakening that every wound signifies” (

Keul 2021b, p. 196)

15 This is when “[S]omething extraordinary happens”: survivors begin to speak and are willing to be wounded again and again by making themselves more vulnerable, risking opposition, stigmatization, exhaustion and isolation—all in the hope of getting their lives back. When they make their voices heard and persevere in this, survivors respond to “a power grab by the perpetrator or perpetrator organization with a surprising ‘counter-conduct’ through a “sovereign act of self-expenditure”. Thus, they grow beyond their “own boundaries and defensive strategies, and finally even beyond herself”. This is the

expenditure paradox. When vulnerance is activated, damage increases. Self-expenditure, however, realizes that the only way to break free from vulnerance is through daring to be wounded in vulnerability. “The power of the sacred”, Keul writes, “can then be turned around and pointed in a completely other—namely life-opening—direction. In this case, risk strengthens resilience”. Resistance to vulnerability through vulnerance is stopped in its tracks and violence is met with the persistent (perhaps, for the profane, pesky) choice not to seek invulnerability as a future-oriented prevention of wounds, but to enter into the intimacy and intensity of life instead and there to discover the other kind of power. When Keul writes that “[B]ecause survivors want to protect themselves, they run the risk of blocking that which could contribute to their healing”, she reflects the challenge this involves (

Keul 2022). Those who have been wounded by abuse and again by cover-up, may very well fear to let go of what they know, even if it is destructive. They may have become used to the power their wounds extend into their lives and have accepted the loss of sovereignty. Pain has become their home and distrust a habit. Besides, the profound sense of shame, that is detectable especially in people who have been abused and deeply wounded in childhood, is one that does not understand that life is for, not against, humanity. The sense of powerlessness and of a loss of sovereignty is strong.

For the expenditure paradox to genuinely work, it needs to be trauma-informed, aware of the particular hindrances for those who were directly impacted by abuse and cover-up. It is here that Keul’s understanding of invulnerability can be supported by the implications of an observation made by Gabrielle Thomas. In her article on vulnerability, Thomas indicates that Gregory of Nyssa considered it to be something humanity had to avoid, while invulnerability should be chased. This may seem to contradict Keul, but on a deeper level, it is the opposite. According to Thomas’ analysis, Gregory of Nissa sees vulnerability as “the means through which antithetical powers, sin, and the passions attack the human soul, drawing it away from, rather than toward, God” (

Thomas 2022). What he responds to, however, seems to be much closer to the practice of vulnerance than to how Keul interprets vulnerability. If this is so, then invulnerability can be related to cultivating an inner attitude and discipline that resists the pull of vulnerance rather than the reality of vulnerability. This is not a precondition for people to be invited into the paradox of expenditure and thus opening up to the other power, but a trauma-informed wisdom that may help guide it to fruition.

What is this other power, though? When looked at from the characteristics Keul assigns to it, it is not something that can be grabbed, it is given. Yet, where is its source? Here, various Christian theological ideas can be named, but the one that encompasses or expresses them perhaps the most accurately is that it is the power that emanates from the excess love of God, the Life of all life, through incarnation—becoming fully human. Ilia Delio expresses it as God’s “self-involving love” and of “an emptying of divine self into another”. She gives the sacred, as Keul uses it, an earthly and transcendent meaning when she says that “[N]ature is entangled with the wild kenotic love of God” (

Delio 2020). This kenotic love—a much treasured, debated and highly held Christian conviction—does not wound, but offers to enter into, and even own, existing wounds. Responding to it begins by voluntarily sacrificing defense mechanisms, identity impoverishment and violence and entering into vulnerability with eyes and ears open. It is an adventure of loss and change that involves making the choice to embrace that there is no room for denying or avoiding the beauty that we have lost. To enter the paradox of expenditure, in other words, means that we anticipate grief and choose it anyway. This is authentic suffering.

5. Authentic Suffering and Bodily Integration

It is here that a comparison with elements of the book

Trauma and the Soul by Donald Kalsched becomes interesting (

Kalsched 2013). Drawing on his expertise as a Jungian psychoanalyst, Kalsched writes that “[T]rauma is about a crushing blow to the generative innocence at the core of the self—and trauma survivors often feel that they have lost their innocence forever”. Many of those among us who have experienced particularly early childhood forms of violence and its traumatic impact will resonate with this. What makes his work of added interest is the way in which he connects the impact of trauma to the active role of the human soul. Active in the sense that the soul mediates the dynamic flow between those which grounds and transcends us, the divine and the human, the internal and external. Incarnated in the body, the soul connects us to our environment, navigates us between innocence and experience and integrates our personality. Trauma in early childhood puts pressure on this because precisely that which ‘animates’ a person is crushed. This is the experience of brokenness and fragmentation trauma survivors experience. This brokenness, though, is not for nothing nor is it irreversible. It has one purpose: to protect the very core of our aliveness in order to eventually journey to, and arrive at, restoration. In the in-between and overwhelmed by the loss of innocence and the profound reality of pain it includes, fullness of life becomes impossible. It is too scary, too confusing, too risky. The only option is to grab and search for the survival kit. Here the human psyche steps in. Tapping carefully into the mytho-poetic and imaginative ability of the self-care system, the psyche seeks to escape a world of violence by attempting to find solace in rituals, stories, dreams and symbols. For a while, this makes suffering tolerable and life bearable. People who are wounded through violence can be soothed by mystical experiences or profound senses of connection with animals, nature and the universe. However, due to the ongoing pressure of disenchantments and disappointments, the constant bodily tension and the hardly felt but deeply present sense of self-alienation (which is identity impoverishment), this cannot be maintained. Our bodies and emotions slowly grind to a hold. The fragmented partial world of protection and coping shakes. Precisely here lies hope, for the soul remains only “temporarily suspended”. It waits until the path towards integration can be re-opened. The seeds for a return towards wholeness, indwelling and integration actually and perhaps surprisingly lie within us. Put metaphorically: a broken heart can return to being fully alive because it has the possibility of becoming a heart that is broken open. For that to happen, however, the willingness for authentic suffering is called for.

How this works is illustrated in the Grimm story The Girl without Hands Kalsched uses. In this classic fairy tale, a daughter was brutally dismembered when her father, claiming that ‘the devil’ made him do it, cut off her hands. He then tries to convince her to stay at home using the excuse that finding a husband, given her imperfections, would be impossible. Besides, the world outside is unsafe. The girl, however, chooses to leave and thus turns away from the false safety of a half-lived life. She begins a journey not knowing or being able to control what might happen. When she comes to a garden, she cannot—hungry as she is—even pick the pears of the trees for nourishment. Faced with total powerlessness, she prays and hopes. Right at that moment of surrender, an angel appears who picks the pears for her, helps her to eat them and continues to do so at regular times. The gardener is intrigued and introduces her to the king to whom the garden belongs. Puzzled by the sight of her receiving food daily from a to him invisible power, he gets to know her. Looking at who she really is, he relates to her wounded innocence and gives her a pair of silver hands. His love along with the prosthesis begins to increase her self-esteem and brings her partial restoration. She feels less lonely, more worthy and less crippled. They get married. The story could end there, but it does not. Her path to wholeness is not yet finished. One day, the king has to go to war, and she is left behind in the intriguing power games of her mother-in-law. Her silver hands are taken away and, through lies sent by her mother-in-law to her husband, they are manipulated into divorce. The woman has to flee and hide in the woods. After a while, the king discovers the truth, seeks and finds her. Looking first from a distance, he wants to return the silver hands to her. But, coming closer, he realizes that she no longer needs them. While living in the forest, through perseverance, learning to love the earth and tapping into her inner strength, her own hands have grown back. The couple remarries: this time as equals.

From the perspective of the power of vulnerability and its distinction from wounds, three observations can be made on the basis of this story. First, spiritual food and therapeutic tools are necessary to prepare and guide through survival towards fullness of life. Yet, they are not sufficient. The move into life itself, and re-creation, comes through the connection between the body and the earth. Ultimately, it is there that “the loss, which is painful and shatters all suddenly becomes creative. Loss, wound, decay—these words point to death; but suddenly they change direction and open up life” (

Keul 2021b, p. 75)

16. Secondly, the woman entrusts herself to the adventure of life both spiritually, physically and relationally. All along the way, she kept making herself vulnerable and refused violence, revenge, or wrongful submission. She does not stay in a role prescribed to her first by her father, then by her mother-in-law and not even by her husband but gains sovereignty and freedom by spending time in a safe place and there to receive from the other power. She ultimately confirms what Gabor and Daniel Maté wrote in

The Myth of Normal: “If we treat trauma as an external event, something that happens to or around us, then it becomes a piece of history that we can never dislodge. If, on the other hand, trauma is what took place inside us as the result of what happened, in the sense of wounding or disconnection, then healing and reconnection become tangible possibilities” (

Maté and Maté 2022, p. 35). Thirdly, Kalsched approaches the mytho-poetic and mystical experiences as mainly belonging in the self-care system. This is, indeed, needed for those who experienced childhood trauma in particular. Yet, in an interesting link with Keul’s work on mysticism, this survival strategy may undergo a genuine metamorphose if embraced by the expenditure paradox. As a survival strategy, it does not need to be victimized, but it can become a sacrifice of self-expenditure. The experience of mysticism, or a mystical experience, can bring about the other power that transforms silence and cover-up into saying what was unspeakable. Keul, reflecting on the work of Michel de Certeau, defines mysticism as “the mystery of that intimacy of life that occurs at the turning point where loss gives rise to creation and a trace of God is revealed” (

Keul 2021b, p. 70)

17. Mysticism is, moreover, a linguistic practice. One that, strangely, starts when people and their communities are touched or wounded so that language breaks down and the unspeakable arrives. Falque, speaking of the incarnation, confirms this observation when he writes: “In the face of suffering and with the experience of existential anxiety, words largely fall silent, precisely in that they take on the body”. He puts it more succinctly when he says: “When words are silent, the flesh speaks and what springs up are ‘infantile shaking or sobbing’, that of the child without-speech” (

Falque 2019, pp. 82, 106). When these wounds, however, or the sobbing child, are either touched by the other power or entered into through authentic suffering, they can unleash the power that pushes the unspeakable towards language It is, as Martin Laird writes in his book on contemplation, what “frees us and helps us move from victim to witness. Growth in inner stability, even in the midst of chaos, deepens our capacity to be aware of what is happening within us

as a happening” (

Laird 2006, p. 105).

This insight resonates with the work of Daniel J. Siegel and Chloe Drulis and their empirical research in the field of Interpersonal Neurobiology (IPNB). Siegel writes: “Given the relational nature of our minds, how we come to sense our connection with other people and the larger natural world in which we live, our sense of belonging, directly shapes our well-being”. Interesting enough, this connection can be experienced, even for people who are mentally suffering, through the simple exercise of being present to ourselves, to our senses, our bodily sensations, our thoughts, our relationship with others and with the world. Their work points to one important observation: when people practice the Wheel of Awareness, a form of mindfulness Siegel developed, there arises—sooner or later and irrespective of their particular background—a sense of being taken up into a profound sense of connection and belonging often defined as love. It is a connection that increases empathy and attunes communication. It augments the ability to focus on the experience of another person, modulates fear and enables compassion (

Siegel and Drulis 2023;

Siegel 2020). Put differently, it is through the body and bodily awareness that a sense of belonging and community is felt, and emotions are regulated. Going beyond superficial connection, it is a way in which the mystical can integrate into daily practice and the other power can be increased. Something akin to this was expressed by a victim who became a witness when she wrote: “I am amazed and sometimes in awe. In the deepest darkness, I have so far experienced lay the seeds of what is now quietly growing: a sense of all-encompassing trust and soft beauty. The fear that I buried in the most hidden places of my being and that had been literally burnt and bred in me through all that suffocated my childhood and teenage years, gradually ebbs away. As it does so, there is no emptiness left behind but space. One I cannot but surrender to in thankfulness and love. None of this came about through will power and not even through brokenness but through the very absent-presence of the Mystery we name God” (Anonymous 2019)

18.

6. Death, Humility and Identity Dependence

The paradox of expenditure, while cultivating invulnerability to vulnerance, does not make anyone invulnerable. It refuses to glorify pain while not avoiding it. Silence is sacrificed, and all forms of violence are submitted to the power of self-expenditure. It waits until the Life of life enters through the cracks of wounds.

What is the expenditure paradox responding to? Though it may initially be triggered by the desire to stop the abuse and thus protect other potential victims, nevertheless, it is a double response. Like vulnerance, it responds to probable wounds that are part of human vulnerability but also to the unpredictable, untamable, self-giving love of the Divine, or the Life of life—the other power. As the same abused person mentioned above wrote: “Unbeknown to myself, I avoided this deep sorrow for a long, long time, using my intelligence to reason about the pain and to look at it as if color blind, dulling its brilliance. As if the pain was a fictional story and not a biological, physiological, psychological and intellectually historical truth. Not to face it now would be like a prison sentence marked by un-lived life” (Anonymous 2019).

These words reflect and accept that

coping with wounds, especially that of death, we all seek to escape is not enough. To be fully human means to look at death and “to enter into its proper finitude” (

Falque 2019, p. 18) because, as Delio mentions, the overflowing, kenotic love that is entangled with nature is there. It is where we can leave an un-lived life behind. While pushing aside “all naïve tenderness to exalt pain or all excessive spiritualization”, Falque points to the radical incarnation of Jesus of Nazareth who, in taking on human flesh, did not only choose to suffer for others. He suffered his own agony and anxiety for death. His humanity was so total that he did not only suffer and die for others, like a secondary experience, but entered into it from his own personal being. It is only there that his humanity became complete (

Falque 2019, pp. 10–21, 82). This thought is deepened by Keul when she writes “The incarnation of God is an act of love and solidarity with human beings in their vulnerability. Therefore, the love of God cannot be had without the love of one’s neighbor. The fact that Jesus is willing to take risks for life and limb for this insoluble connection without being forced to do so distinguishes his actions as a practiced incarnation. He puts his vulnerability at risk to open up life—for himself and for others” (

Keul 2021b, p. 108)

19. In a way, his choice and experience are reminiscent of what the book of Job says: “Even after my skin is destroyed, yet from my flesh I shall see God”.

That the choice Jesus of Nazareth made for vulnerability is profoundly linked to humility is put forward in an interesting way by Kent Dunnington. He argues that Christ did not only show his humility through self-expenditure and self-giving but also through his willing death that had two aspects: a biological and an identity dying. Christ shows us how to ‘die to death’ as the controlling power it has over us”. The humility of Christ consists of the trust that “he need not protect himself from death”. This, Dunnington argues, “is possible only if there is another kind of selfhood, a selfhood that is not finally threatened by poverty and dying…but rather that is sustained by relationality, self-expenditure, and needy receptivity. Far from making his death an afterthought, Christ’s resurrection and exaltation herald precisely this different way of being which does not immunize itself from death but rather enfolds death into the mysterious form of selfhood in which complete self-expenditure is…life” (

Dunnington 2016). Christ embraced radical identity dependency, not as a clinging unto another, but as an intense trust in kenotic love without trying to escape the reality of death. He lived in the growing knowledge and awareness that his life was totally dependent on God and constituted by relationships, but also that to be human is to be finite. He lived what Thich Nhat Hanh describes as “[E]verything relies on everything else in the cosmos” (

Hanh 2017, p. 14). Thus, Christ lived in active resistance against vulnerance through the power of total vulnerability and that is in and through the flesh.

7. Discussion

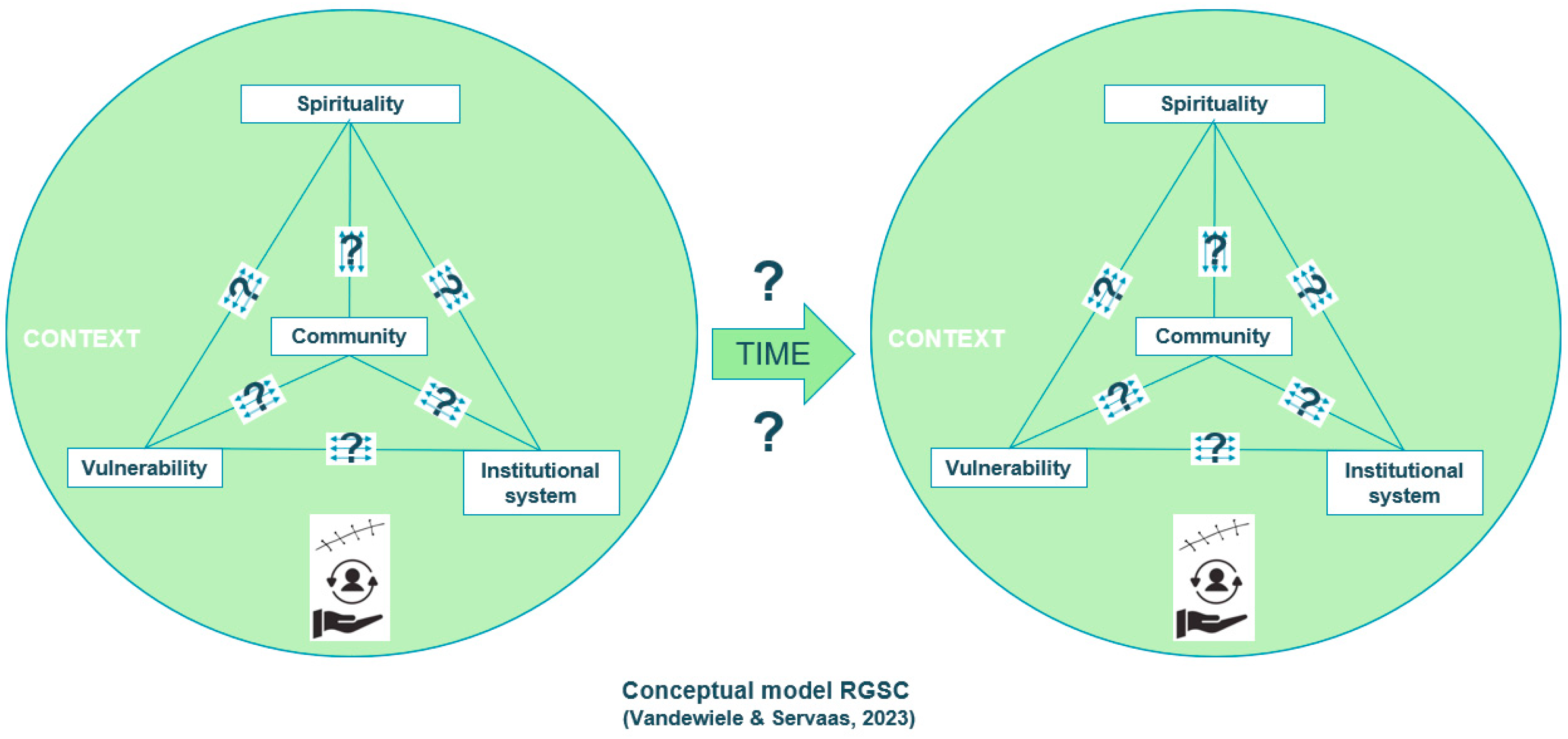

All that was said above builds on the foundational concepts, insights and terminology Keul gives us. Because of its fecundity, the aim was to enrich her research and to begin to reply to the question:

what the Church is responding or not responding to in the area of abuse and its impact. From this, the other question marks, as seen in the theoretical model, can guide into further inquiries. Inquiries that can be picked up by researchers ensuring that growing knowledge into the

what is calling for response raises awareness into

how community, vulnerability, spirituality and the institutional system are choosing to respond. These four elements, their interrelation and how they are affected by time form the dynamic basis of the model below (

Vandewiele and Servaas 2024). At its heart lies the human person and thus, as indicated, the inter-are of being human. Inter-are refers to our interconnectedness and the fact that we belong to the cosmos, the world, nature and one another. Through applying the model from the perspective of vulnerability and vulnerance as Keul understands these, several observations can be made. These are, however, only the beginning of a more, and needed, transdisciplinary inquiry. Keul has paved a way on which we can journey further (

Figure 1).

7.1. Community

In the abuse and cover-up of the Roman Catholic Church, the entire social or religious network is wounded for the simple reason that human beings inter-are. This inter-are includes, and may even be constitutive of, our common vulnerability. It is where the what we respond to is rooted. Yet, because the desire to be as wound-free as possible paradoxically marries the willingness to be wounded in order to protect that which is deeply ingrained in the imagination as sacred, that inter-are is pushed aside. Accumulation of protective measures seeks to replace it, triggering the complicated interrelationship between the profane and the sacred. Knowing how (vulnerance) we respond to the what (vulnerability), in the context of abuse and violence, gives us a fundamental choice. Do we continue the Sisyphus action in the attempt to establish utopia, or do we kneel in the humus of our humanity to grow new hands—like the girl in the fairy tale? The first is a choice for the profane and how it serves the sacred. It accumulates protective measures while simultaneously impoverishing these through the ever-increasing cost of security and the victims that need to be sacrificed. Because the second opens up to the self-involving love of the Life of life, it goes beyond the profane and sacred and discovers the power of expediency that is also costly, but nourishing. The sacrifice asked for here is to let go of everything that seeks to hide vulnerability and the practice of vulnerance. The choice placed before any community is between running away from vulnerability and, in that marathon, be slowly exhausted into death, or entering into vulnerability and there to discover that every death creates possibilities for new life. The latter choice resonates with what Christ did. He chose radical vulnerability even while he was suffering and dying. When a community seeks to follow him, it seeks to live the expenditure paradox, starting with receptive silence and, there, letting go of that which is considered sacred to then allow communal wounds to give us new images and language, flowing from our inter-are.

7.2. Spirituality

Such a communal response reflects the inherent spirituality that comes with the expenditure paradox. But spirituality is also part of the vulnerability paradox, especially where the sacred rears its head.

That and

how we respond to vulnerability reflects our desire to find meaning in and through our relational experiences with our selves, family or the ‘bodies’ we belong to. Here too, we are placed before a choice. Spirituality can be used, like the sacred, as a tool of violence, caused by and causing spiritual harm. If so, it becomes a form of exclusivity that puts safety high on the agenda, flows from a genuine desire to protect from harm, but is also linked to using violent sacrifices in order to hold on to what is deemed sacred. On the other hand, spirituality can follow the path of life with Christ, which is inclusive and open to being wounded. It is where not only those who were abused, but the whole community that is inflicted by it, experiences what Timothy Radcliff writes about the gaze of Jesus. Radcliff says that to be gazed on by Jesus is “not just a vague warm blind benevolence”. Why? Because he “looks at people as they are. To be seen by Jesus is an experience of truth”. This truth also means that “Jesus’ delight in us is not a vacuous affirmation; it is our painful joy of being stripped of pretension, of stepping into the light. In the presence of that face, we discover who we are. The gaze of Jesus peels away the mask that we wear and deconstructs the false faces we show the world” (

Radcliffe 2005, p. 62). It is actually where we, through seeing one another from the gaze of Christ, learn reverence which can, in turn, knead our relationships in and through vulnerability. One of the ways in which this can be expressed is in the words of this wounded person already mentioned above. She says: “You know what I am slowly learning? That to allow and accept all and every pain a special kind of humility is needed. One that perseveres and doesn’t run away from the chilling realization that I was abused and emotionally abandoned by both parents and that, though they broke me, they were suffering from brokenness too. A humble attitude that embraces loss and that sees sharply how before I was a child I was already robbed of being a child. Yet, it is only through this courageous God-given humility that the unbelievable emptiness, the loss of emotional and spiritual nurturing, can be filled with the Breath of our Life. And so, it is beginning to dawn on me how passion for Christ is turned through suffering into the passion of Christ for all people” (Anonymous 2019). This is the kind of spirituality that belongs to the choice for the paradox of expenditure.

7.3. The Institutional System

“Human living is structured by symbols. Therefore, both personal life and institutional systems belong to the symbolic order. Institutes receive their legitimacy in their collecting, ordering and translating of symbols into overarching forms of meaning. These then serve as platforms for ongoing social interaction. Human persons are thus interactively connected to institutional systems. From this follows the inference that just like persons can change in and through the experience of life itself so can institutional systems become transformed” This is how the Research Group for Safeguarding in the Church defines institutional systems (

Vandewiele and Servaas 2024). These words seem to fit neatly in the profane and its tension with the sacred. It is true and also necessary as, from the perspective of abuse and cover-up, organizing and establishing safeguarding policies is needed. The question is, however, whether the institutional system is open to be transformed when it has used its hidden power to contribute towards abuse and cover-up. When the response of the Church in its institutional role is limited to that of writing reports and codes of conduct, establishing safeguarding policies, setting up support groups or engages with secular initiatives,

what is it responding to? Interestingly enough, it can actually be to vulnerability, spiked with vulnerance. There might be fear of digging deeper into theological and spiritual beliefs and symbolic power and what this could mean. It could be anxiety about protecting sacred symbols—profoundly embedded in the communal imagination—that actually contribute to patterns of violence and abuse. Perhaps there is also an underlying fear of facing the fact that violence needs to be admitted and included in the ”normative narrative of the Church about itself” (

Gruber 2024). Such a daring journey into institutional vulnerability and vulnerance might call for sacrificing what is settled in the imagination as real. It is, from this perspective, easier to deal with the wounds by using profane measures to avoid possible loss and change. One way in which this might become visible is in insisting on the need for psychological help for ‘victims’ and also ‘perpetrators’ but keeping this in the realm of interpersonal relationships and therapy. Unconsciously, this fosters a dualistic, almost polarizing, ‘them and us’ mentality: victim versus perpetrator, the wrongdoer versus the one who suffers, the institutionally powerful person versus the individual, etc. It creates room for the ultimately paralyzing sense that roles are the same as identity. ‘I am’ a victim, ‘he is’ a perpetrator or bystander, perpetually undermines the possibility to come to the awareness that ‘I can’ leave victimhood behind and ‘they can’ let go of a wrong, or absent, use of power. Another way in which the institutional system can become stuck in the profane, is in its—so far—lack of attention to the seriousness of vulnerance through cover-up. This is what Hans Zollner referred to in his reflection on the report on abuse in the Catholic Church in Switzerland: “Many in the Church do not realize that distrust of bishops and other Church representatives has an impact on the credibility of their proclamation of the Christian message. It is obvious that the message is less likely to be believed if the messenger is not credible because of his actions. Those who preach well and behave badly gradually destroy the very basis of faith”. At the end of this article, Zollner says that the “offering of apologies, almost as a ritual gesture, is perceived as empty if the apologies are not accompanied by approaches that demonstrate that they are not just words” (

Zollner 2023).

Because institutional systems can become transformed, however, it can also make a choice. It can continue to follow the line of the profane and sacrifice through exclusion or it can participate in the vulnerability of, and in, Christ and there to discover and receive the power of expenditure. This involves consciously choosing to enter into the non-verbal reality of authentic suffering and to balance the power of the expenditure paradox. It is where an institutional system can organize communities that are imaginative beyond what is known into the unknown.