Abstract

The relationship between popular vernacular Catholicism and the more official liturgical variety has varied over centuries. Following the subjugation of Ireland by the late 17th century, and the institution of anti-Catholic proscriptions, the number of priests available became more restricted. Religious observation subsequently centered on holy days and local sacred sites including healing wells, many of them dedicated to saints. Always central figures in death rituals, women who mourned the dead—“keening women”—were so called because they lamented the dead through a combination of voice and song. We will show how the songs relate to a deep liminal spirituality that existed semi-independently of official Church norms, and how the voice served to establish their position. In the Catholic revival of the late nineteenth century, such forms were ousted by European modes of worship, but persisted at the margins, allowing us insight into their previous vigor.

In an expansive, inclusive view of both music and religion in Ireland, one can imagine not just the devout followers and the emphatically direct “sacred music” of the holy site and its male leaders, but also the atheists, the women, and the silences. One might also take note of the figure who exists between the orthodox and vernacular approaches to Catholicism: the older Irish woman whose voice, in the context of mourning the dead, hovers between singing and wailing. In this article, we explore the territory of the Irish death ritual, especially the “wake”, and the role of the female professional mourner in facilitating the process of that ritual.

Ireland’s relationship with the Catholic Church has been one of ebbs and flows as the power of the Church waxed and waned before, during, and after its suppression through English colonialism. At a time when 18th-century penal laws against Catholicism resulted in a distinct scarcity of priests along with the existence of a vernacular figure, the bean chaointe1 or keening woman—both representing and maintaining community Catholicism—was important in the role of the female professional mourner who performed ritualized laments. Bourke’s description is apposite here (Bourke 2002, p. 1365):

…by convention the bean chaointe was a woman crazed with grief whose appearance and behaviour expressed disorder and a loss of control. In fact, however, her performance, like that of a tragic actor, required considerable intellectual stamina, as well as great reserves of emotion.

As a liminal figure who was simultaneously Catholic and not-quite Catholic—who also represented a distinctly alternative spirituality—the professional mourner brought stability, an effective ritual, and a role of power for older women into times of crisis in local communities. This article examines the role of the female professional mourner as she served as a stalwart bastion of suppressed Catholicism, even as she drew liberally from older customs of celebrating, mourning, and serving both the community’s dead and the community’s survivors.

The relationship between popular vernacular Catholicism and the more official liturgical variety has varied over centuries. Once dubbed Insula Sanctorum et Doctorum, the island of Saints and Scholars, Ireland’s religious fortunes waxed and waned according to the dictates of colonialism and the rise and fall of the Catholic Church. Following the subjugation of Ireland by the late 17th century, and the institution of anti-Catholic proscriptions by (Anglican) England, the number of priests available became severely restricted (Bishop 2018, p. 19). The end of the Jacobite threat and the accession of George III in 1760 saw an easement in the application of Catholic proscriptions. From the late 1600s until 1795, with the establishment of Maynooth as a seminary, priests trained in continental Europe. Until the mid-18th century, they practiced in secret under Protestant colonial rule. Throughout the 18th century, due to the shortage of clergy, Irish religious observation centered on holy days and local sacred sites, including healing wells dedicated to saints. Vernacular specialists with religious knowledge and skill in popular religious rituals flourished in Ireland during the 18th century and into the 19th century.2 Included among them were men and women who had memorized the catechism, and who taught its question-and-answer format to younger community members.

Always a central figure in death rituals, women who mourned the dead—“keening women” or mná caointe —were so called because they lamented the dead through the voice. From at least the 8th century, the public performance of lamenting by older women has been viewed as a central feature of the Irish death ritual (Lysaght 1997, pp. 65–66). These women—often past the age of childbearing, and with more freedom in the community—could often also be midwives and healers who used herbs and other substances to effect cures. Women, professional mourners among them, were also the possessors of a rich body of religious song. Some of these popular hymns approximated the keening dirge and were held to have been sung by the Virgin herself for Christ both during and after his crucifixion. Keening women used this narrative as a justification for their lamentations arguing that if Mary had lamented over Christ’s body, it was necessary for them to uphold the custom she had established (Lysaght 1997, p. 66). We will examine one of these hymns and relate them to another sung genre specifically identified with women: secular mourning songs. In doing so, we will demonstrate the ways in which they relate to a deep feminine spirituality that existed semi-independently of official Church norms and served the purpose of spanning the gap between vernacular and liturgical traditions.

Descriptions and discussions of keening—improvised, vocalized mourning, sometimes with verse texts—in Ireland are well known; see, for example, Angela Bourke’s “The Irish Traditional Lament and the Grieving Process” (Bourke 1988, pp. 287–91) and Anne Ridge’s Death Customs in Rural Ireland (Ridge 2009, pp. 56–58). Less common are descriptions of the music of keening, although the pioneering work of Breandán Ó Madagáin remains a resource (Ó Madagáin 1981, 2005). Described variously as sounding like a dirge or a lullaby (see, for example, Sullivan 1873, pp. 324–25),3 the music of keening is therefore of intense interest to scholars of music and religions alike. Music and song—especially song—suffused every aspect of pre-modern Irish life, as documented by many travelers; Ó Madagáin cites numerous sources showing the ubiquity of song in pre-famine Ireland (Ó Madagáin 1985, pp. 130–31). Birth, marriage, and death—the three great rites of passage in human lives—included their share of song and music.

Here, we focus on the music of the keen to accompany death rituals as a religious act through the presentation of two examples. We confine ourselves to the presentation and contextualized discussion of one keen and one sacred hymn, both to show how these two examples relate to each other and more importantly, how they exemplify the range of spiritual expression as embodied by women. We contextualize the performance in terms of the expressive culture of the time, by linking pilgrimage to holy wells with similar activities occurring at wakes and death rituals. In so doing, we attempt to grasp the engaged, embodied, and deeply performative nature of vernacular Irish religion prior to the ultramontane reforms instituted and reinforced by the Irish Catholic Church from the time of Cardinal Paul Cullen (1803–1878) to the present. By examining these, we show the range and extent of keening melody and expression.

We hold that keening could have a varied musical form, capable of being changed at will within its limits by skilled practitioners according to the context, which varied according to the deceased individual. Before we present these examples, we feel that it is necessary to contextualize them within a framework of other once-widespread death customs that nowadays have become rare or nonexistent in modern Western societies. While we present these examples as an authentic representation, we are also careful not to overextend our claim. We are therefore necessarily tentative in our exploration as our inquiry is far from exhaustive.

1. Wakes

The context of the wake as a central element of the Irish death ritual has been documented for centuries (Ó Muirithe 1978, p. 20). It is an ancient practice not limited to Ireland. Following ritual custom—which Arnold Van Gennep describes as among the ways in which people celebrate the transition from one state to another (Van Gennep 2019, p. 3)—was an important way of exercising control over a frightening experience, and to do so in a locally appropriate way (Ridge 2009, p. 11). A wake could extend over three days and nights, but this was often a contentious matter, with clergy trying to exercise control over their congregations, to prevent what they perceived as the profane excess of these affairs (McLaughlin 2019, p. 3). One measure instituted was the removal of the remains to the local church after one night at home so that games and other forms of entertainment were effectively curtailed. Since the 1960s the wake consists mostly of a single night at home followed by removal to the church. Nowadays, funeral homes conduct the viewing of the corpse, and strict hours are often observed. Previously, as a normal feature of the event, the corpse lay in repose in the front room of a home. Relatives and friends would gather to mourn, sometimes with professional (i.e., paid) individuals calling out the name of the deceased, addressing the person directly (asking why they died, how could they leave, etc.), thus celebrating their good qualities in community with other mourners. Paid mourners were almost invariably women, and a rare, striking description of a late 18th-century professional male mourner, Nicholas Walsh, serves to underline the gendered nature of this vocation:

This Nicholas was an extraordinary man for his prowess at keening. He was a living chronicle of all the family pedigrees in the adjoining districts [Kilkenny, Waterford and Tipperary], throughout which…he was universally recognized as a professional keener…On his arriving at the wakehouse there was a great stir and excitement among the people. He respectfully uncovered [his head] on entering, said a prayer or the Latin psalm for the dead, and then took his seat among the female mourners who surrounded the corpse and who in the dresses of the period had an imposing appearance amid the profusion of lights. Strangers…invariably mistook Nicholas’s voice for that of a woman of great oreal [oral] powers so mellifluous and pathetic was it in all the modulations of the song of sorrow—especially in leading the loud wail, in which the females at either side took part at the concluding words of each stanza.(Ó hÓgáin 1980, p. 20)4

Even this short excerpt captures the dramatic and performative aspects of the keening ritual and the exceptional phenomenon of a male professional mourner, perhaps once a trainee priest who had not taken final orders. It also notes the religious nature of the keener, even if the ritual was not so perceived by officialdom. After the specific time allotted for the wake, the corpse would be carried in a procession to the burial place with the mourners present and vocal as the earth was thrown onto the coffin in the grave.

The wake also featured the use of storytelling, singing, dancing, and the conspicuous consumption of food, tobacco, and alcohol. This license, although a constant feature of liminal ritual festivity, may seem at the very least strange to modern, urban dwellers in western European and North American societies, where death is now usually subjected to strict avoidance. The avoidance of the word “death” in English, in preference for the words “passed away” or other such euphemisms, has become a normative feature of modern Western culture. In Ireland, viewing the remains is still an important event, though it has become more and more circumscribed. The inability to process death is connected to a wish to deny death in the modern world, in direct contrast to Irish contexts of the 18th and 19th centuries, where death was a common, everyday occurrence regardless of the age of the deceased (Toolis 2017, pp. 49–51). This immediacy of the possibility of death meant that the conclusion of a long life, well-lived, was a reason for joy.

The two key elements of the wake—lamenting and revelry—correspond to the universal features of the funeral rites of traditional cultures identified in Van Gennep’s analysis of passage ritual, namely public mourning and a “period of license” (Van Gennep 2019, p. 148). If it was a tragic death, wakes would be solemn and quite reserved; if it were an older person who had lived a full life, it was not as big a tragedy as if it had happened to a young person (Ó Súilleabháin 1967, p. 28).

Consistent with the contemporary description above, Breandán Ó Madagáin describes the gol or communal wail (the third stage of a round of keening) as a largely non-lexical element by professional mourners that might include the name of the deceased followed by a non-lexical refrain. “No words were used, only vocables such as “och ochone” or “ululoo,” so that the community gave poignant expression to their emotion in purely musical terms, using their voices as a musical instrument, just as in the instrumental lament played on the pipes or the harp” (Ó Madagáin 2005, p. 84). Well before the time that the Catholic Church came back into power by the mid-19th century, keening was a focus of Church suppression (Ó Súilleabháin 1967, p. 138).

Synodal meetings of bishops from the seventeenth to the twentieth century issued regulations on a fairly regular basis in an attempt to stamp out this and other funeral practices considered to be unchristian, unseemly, and a danger to public and private morality (Lysaght 1997, p. 66). By declaring as early as 1748 that all public lamenting be banished under threat of excommunication (Ó Súilleabháin 1967, p. 139), the Catholic Church’s stance on keening was made abundantly clear. Yet the practices persisted in spite of the hierarchy.

2. Wells

It is helpful here to amplify the festive celebratory spirit of religious observance in the period by drawing attention to other common aspects of it. Ireland contains upward of 3000 holy wells, and many are still visited today using the same rituals as were used in their heyday of the 18th century. Supplicants seeking aid with various illnesses approach the well in humility. They follow the prescribed routine, rounding various stations and reciting the prescribed prayers (Ó Giolláin 1998, pp. 201–21; Rackard and O’Callaghan 2001; Ray 2014, pp. 93–110). They take water from the well and leave a token—such as a photograph, prayer, or rosary beads, or traditionally by tying a rag to an adjacent bush—that may symbolize the reason for their visit. In the 18th century, secular revelry and even fights formed a very central part of visits to the well, especially during the Patron (or “pattern”) days in honor of the local saint (Ó Giolláin 1998, pp. 203–6; MacMahon 2013). With the reorganization of the Catholic Church after 1760, the clergy exercised increasing control over these festivities, with the intention of proscribing them. In most cases, they were successful.

The well in Ireland stands at the liminal point not just between the upper world and the underworld—with the opening as the joining point of the two—but also between the sacred and the profane. Observers frequently noted the touching piety of pilgrims while recoiling from the apparent drunkenness and disorder that characterized many of the other attendees. Such juxtapositions proved incomprehensible and repugnant to metropolitan travelers unaccustomed to them. They disapprovingly regarded both practice and practitioners as “savage”.

Although strictly not central to the religious observance of holy wells, entertainment practiced at the wells was integral to the celebration of recovery and release. When pilgrims had completed their rounds (the turas), they were deemed to be free of guilt. The festive period provided a license whereby new guilt could not be acquired until after departure from the sacred precincts and the return to everyday life. The grace given by the sincere observance of rituals at the well provided a period of liberty that ended only with the return to everyday existence after the holy day was over.

The link between pilgrimages seeking healing and death rituals is clear, revealing the supposedly profane entertainment as an integral part of their expression.5 Wakes were also accompanied by games and merriment. These games provided young people with opportunities for courtship. Only the young usually stayed up all night at wakes. Guarding their good name and respectability, married women would visit the wake-house during the day when things were quieter so that the nighttime activities were almost exclusively reserved for young people. The games could be quite risqué and lewd, with strong sexual undercurrents, as was natural for courting couples. Again, the Church proscribed these entertainments, even reducing the wake—customarily three nights—to two, and finally to one night at home, ensuring that the corpse left the house after the first night and was brought to the Church to prevent further indulgence.

3. The Performative Element

The keening person undergoes a transformation over the course of the event, from someone who has been hired specifically to perform a public form of grieving on behalf of the family and the community to someone who appears to step outside of their normal personality in the extremes of the ritual. Angela Bourke describes the performance of the keen as that of “a woman crazed with grief” (Bourke 2002, p. 1365). As Kevin Toolis has noted, “Death for sure is not a whisper on the island [of Achill]” (Toolis 2017, p. 53).

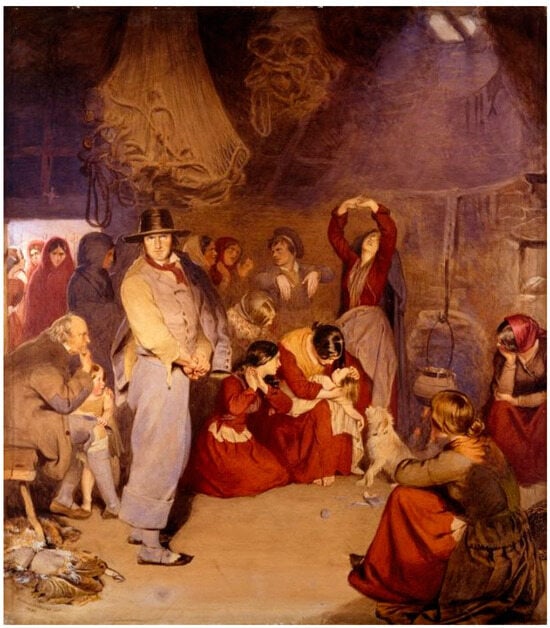

In the well-known painting, The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child (1841), painter Frederic William Burton (1816–1900) depicts the wake of a child; the figure at the front, looking away from the child towards the viewer, is likely the father (See Figure 1). In the center, the female relatives clasp the child, while the keening women gesture with their hands and bodies in the background. This painting, in which Burton took considerable care with the composition, making 50 preparatory drawings (Clancy 2021), conveys visually what we have been describing verbally. It clearly depicts the concentrated emotionality of embodied movement and gesture, adding another dimension to our understanding of the registers deployed by women in their attempt to move onlookers emotionally to share in the grief of the chief mourners. In this worldview, religious experience is not something cool, detached, and intellectually discrete. Rather it is an embodied, verbal, and musical rhetoric of emotional expression, ecstatic and transformative in delivery (see also Bourke 1980, pp. 25–37).

Figure 1.

Aran Fisherman’s Dead Child (1841, by Frederic William Burton)6.

Keening occurred at appropriate times of the wake. When a new relative entered, it would spur an added surge of emotion. John Connaughton, quoted in Death Customs in Rural Ireland, reported the scene at his grandfather’s wake: “The corpse was left out in the room. And they’d raise this cry when any of the friends would come into the room where the corpse was. They’d keen over the corpse. Any friend (i.e., relative) that was after coming a bit of a distance at all, they’d raise this cry, when she’d come into the corpse room and the woman that would come in would join in with them” (Ridge 2009, p. 57). The rising and falling of the volume corresponded to the presence and absence of friends and relatives, matching the height of grief as each person came to pay their respects.

4. The Keening Woman

The woman herself who performed the keen could be a professional mourner.

…the keening woman, the bean chaointe, is the agent of the transition to the next life of the individual whose corpse lies at the heart of the wake assembly, and whose passing is ritually mourned all the way to grave in the highly charged performance of the female practitioners of the caoin.(Ó Crualaoich 1999, p. 192)

In addition to the role of the woman as the “agent of transition”, Breandán Ó Madagáin has also noted that the primary role of the keen itself is to “transfer the spirit of the deceased from this world to that of the spirits” (Ó Madagáin 2005, p. 81). The keening woman’s intermediary status, and the position of the vocalization itself, are central to the success of the wake. The body language of the keening woman—both in real life and as depicted in paintings and drawings—generally features her raised arms at the height of her performance. When an 18th-century woman raised her arms either above her head or outstretched to her sides, she expressed a physical and emotional vulnerability that was not generally found in other contexts.

Professional mourners were usually older women and/or widows; women who were still fertile were vulnerable to the censuring power of gossip. In addition, solo older women needed an income, and being a professional mourner was a way to make ends meet. The most famous keening woman of all—Eileen O’Connell—was a young pregnant widow. As Connaughton mentions above, bereaved relatives of any age could join the keening, adding their own praise to that of the professional mourners; such contributions did not always come from older women. Pregnant women are not normally expected to attend wakes, which makes the fact of no longer being fertile an essential feature of the keening woman. Her postmenopausal status is assumed, and it places her in a position of power since she is no longer vulnerable to pregnancy. It also locates her as someone to be feared. This postmenopausal power is not limited to rural Ireland: the three Fates of ancient Greece (Lichtenauer et al. 2020), the practitioners of Voodoo in West Africa (Alidou and Verpoorten 2019), the women who serve as the “host” of the performance stage in Java (Williams 1998), and so many others are objects of fascination and fear. While in some cases the fear is symbolized by—for example—the scissors held by Atropos in ancient Greece, who can cut one’s life thread, it can also appear in the form of folkloric accounts of “hags” and “witches”. The simultaneous assumptions of vulnerability and childbearing are entirely absent once a woman has moved into her postmenopausal years.

A parallel figure in traditional Irish belief is the death messenger known as the bean sidhe (“banshee”); she is generally said to follow specific Gaelic families.7 Patricia Lysaght’s study shows how the traditions of the banshee varied in different parts of the island (Lysaght 1986). One of the strongest connotations of the banshee was as a sovereignty goddess identified with wild nature and the land itself, and that she cried for those who had been dispossessed from their original lands. Counties Laois and Offaly were traditionally most closely associated with the banshee; the counties were planted (settled by the English) in the 16th century, and the banshee would come and cry at the original houses of the dispossessed Irish.

The banshee is associated with a morning shout—an scread mhaidine—that served as a cursing scream in some ways. It is also associated with the bean chaointe (the mourning woman), and it would generally occur at or after midnight, when the mourning had reached a fevered pitch. The banshee’s popular appearance was believed to be gaunt, clad in black, and with long grey hair. That her appearance, demeanor, and wailing cry are essentially the same as the bean chaointe is no coincidence; it offers an accepted forum for the near-supernatural power of the keening woman in Irish society, outside the realms of mainstream Catholicism and sometimes relegated to “mere superstition”.

5. The Keen Itself

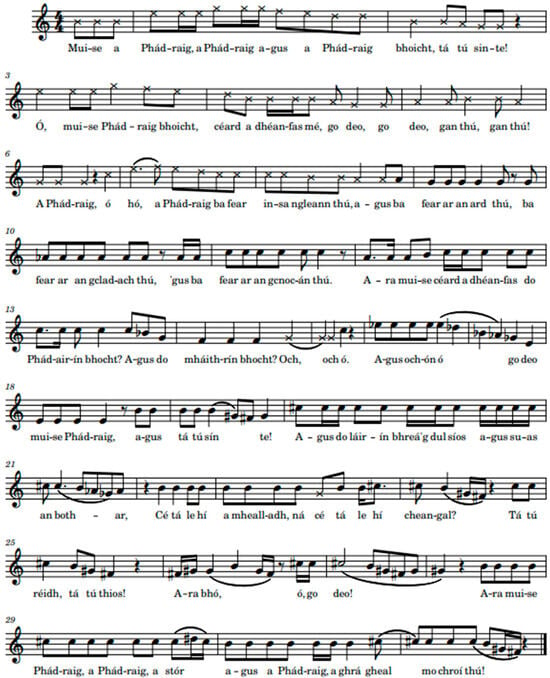

The keen formed a part of these rituals and was performed at specific times. As already mentioned, the scread mhaidine (the morning scream), for example, also refers to the first keening after midnight and was used as an everyday curse, expressing anger. Other times included the arrival of new mourners, the closing of the coffin, and other such emotionally charged moments. In the following example of a keen (see Figure 2), we examine a recording by Seán Ó Conghaile (Cois Fharraige, Galway), who enacted a lament from his memory of a neighbor woman lamenting her husband. Séamus Ennis recorded this piece for the Irish Folklore Commission in 1946, and he reputedly laid himself out in the attitude of a corpse, in order to provide an appropriate context for the performance. This example is of special interest as it shows an intensifying modality of expression as Ó Conghaile shifts from heightened, rhythmic speech (from the beginning through measure 8) to expressive sung performance. In the transcription, heightened speech is represented with the symbol x. It does not precisely follow pitches because it is not yet being sung. For those who do not read music, this example is available online in note 8. In this way, we can actually hear the rising of the emotional range from heightened speech to fully realized melody, thus adding further detail to the consistency of the picture we have drawn.

Figure 2.

“Caoineadh Os Cionn Coirp: Lament Over a Corpse”. Recited by Seán Ó Conghaile, Cois Fhairrge, County Galway (1946). Musical transcription by Sean Williams; textual transcript by Patricia Lysaght (1995).8

- Muise a Phádraig, a Phádraig,Agus a Phádraig bhoicht, tá tú sínte! Ó muise a Phádraig bhoicht,Ceard a dhéanfas mé? Go deo na ndeor gan thú, gan thú!{Pádraig, Pádraig and poor Pádraig, you are stretched!Oh, poor Pádraig, what will I do? Forever and ever without you, without you!)

- A Phádraig, ó hó, a Phádraig!Ba fear insa ngleann thú, agus ba fear ar an ard thú,Ba fear ar an gcladach thú, agus ba fear ar an gcnocán thú.Ara muise, ceard a dhéanfas do Pheadairin bhocht?Agus do mháithrín bhocht?Och, och, ó; a, muise, ochón ó go deo!(Pádraig, oh, Pádraig!You were a man in the valley, you were a man on the hillock.You were a man on the seashore, and you were a man on the hill.

- And what will your poor little Peadar do?And your poor mother?Alas, alas, oh! Alas, alas, oh, forever!)Muise a Phádraig, agus tá tú sínte!Agus do láirín bhreá ag dul síos agus suas an bóthar.Ce tá le hí a mhealladh? Nó ce tá le hí cheangal?Tá tú réidh, tá tú thios! Ara bhó ó go deo!(Pádraig you are stretched!And your fine little mare going up and down the road.Who is there to coax her? Or who is there to tie her up?You are done, you are down! Ah, oh, forever!)

- Ara muise a Phádraig, a Phádraig,A stór agus a Phádraig, a ghrá gheal mo chroí thú!(Pádraig, Pádraig,My love, and Pádraig! Bright love of my heart!)9

Ó Conghaile performed this version of the keen after a couple of pints of beer for the folklorist Séamus Ennis, whom he considered a friend. In an autobiographical work, he stated,

I put a snatch of the caoineadh [lament] on tape and the two pints helped me a great deal to do it. I never thought that there was much basis or sense in the keening that was performed over the dead person, in my opinion. When I was a young man, I often saw the keening woman putting their throats out with their wailing over the corpse. It was how they frightened me. When I grew to be a young man, and when I looked at the keeners, I saw that there were very few tears coming from their eyes”.(Ó Conghaile 1993, p. 49)10

These remarks show the dichotomy felt by those with a more modern outlook regarding the keening women; judging by his performance, Ó Conghaile well understood the emotional range accessed by the lament, succeeding convincingly himself because he had consumed some alcohol, which helped him overcome his intellectual reservations. His rational reaction, however, was one of discomfort because he perceived the wailing and gesticulations as insincere and excessively theatrical.

6. Vernacular Hymns

As well as the more risqué courtship games, storytelling and singing were central to attempts to pass the time during a full-night wake. Any of the songs might be normally sung at ordinary events, but certain women specialized in sacred songs, and these were often favored items at wakes. Wake entertainments tended to follow a general order: courtship games, storytelling, singing, vernacular hymns, and the keening itself. The saying “Sing a song at a wake, and shed a tear when an Irish child is born” points directly to the featuring of songs at wakes, whether as part of the general merriment or as just another form of vocalization (Ó Súilleabháin 1967, p. 28).

Marian songs dealing with Christ’s Passion were also sung at wakes together with other sacred songs. Even though these hymns are not associated with performative grieving, nor are they a shouted cry, they are nonetheless part of the mourning tradition. Among the most favorite hymns were those dedicated to, or spoken in the person of, Mary. It was believed that Mary, as a primary example of a woman mourning her son’s death, would understand the grief of mourning humans. As well as being sung at wakes, these were recited during Lent, the period before Easter, especially on Fridays, and were certainly recited on Good Friday (the anniversary of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ) (Partridge [Bourke] 1983, p. 131). As Angela Bourke has noted in her groundbreaking study of this genre,

Poetic texts exist in Gaelic oral tradition, some short, some long, which describe the Passion of Christ and of the Virgin Mary’s grief on Good Friday…. The term ‘caoineadh’ (keening) is often used to refer to them…These texts comprise one expression of a theme worked by artists and writers for a thousand years: the theme of the Passion.(Partridge [Bourke] 1983, p. 4; translation from Irish by Lillis Ó Laoire)

Patrick Pearse—Ireland’s famous revolutionary/poet/teacher—wrote down the text of one of the hymns of the Passion from a singer named Máire Nic Fhlannchadha bean Uí Chéidigh, Mary Clancy, Mrs. Keady. This performance occurred at a feis (a cultural event with competitions for singing, storytelling, and other traditional arts, made popular by activists during the Gaelic revival in the decades before independence in Ireland) in Moycullen, County Galway, at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

I heard “The Keening of Mary” from a woman of Moycullen. […] I have heard nothing more exquisite than her low sobbing recitative, instinct with a profoundly felt emotion. There was a great horror in her voice at “’S an é sin an casúr” [“and is that the hammer?” (that goes into the coffin)] etc., and with the next stanza the chant rose into a wail. She cried pitifully and struck her breast several times during the recitation.(Pearse 1911, p. 47)

Pearse’s description clearly reveals how, depending on the intensity of the performance, a hymn could transform from a religious song to a lament. It shows the close connection between keening and the singing of sacred hymns also called “caoineadh”, emphasizing the inter-related nature of the genres. He indicates that it was the intensity of the emotional experience of the performer that dictated which modality was the uppermost. The description also reveals a gradual increase in intensity through the performance, as the singer worked her way into the deep well of emotion at the heart of the tradition. Pearse’s description focuses on the mounting horror of the singer as she details the torture endured by Christ as he is being affixed to the cross. Clearly, the singer’s devotion and her own personal pain expressed through her singing affected him greatly, as it confirmed his romantic instincts about the greater emotional range of expression found among Irish speakers in the west of Ireland.

In comparison to the drab self-contained expression of Anglicized, urban modern Ireland, this represented a sought-after ideal for Pearse’s vision of the reborn nation, contrasting strongly with Ó Conghaile’s reading of similar expression. The keen was improvised, and the sacred laments were relatively fixed texts that resembled the keen in their sorrowful attitude, their repetition of the lament vocables—“ochón”—and in their focus on the cruel death of Jesus. This separation of genres helps us to understand that, despite their differences, an emotional register operated among the performers that dictated the relative levels that were appropriate to a particular moment. It would not usually be appropriate to begin a sacred hymn in a distraught state; as one proceeded through the text, one moved into it, with the music helping to release inhibition and aiding the singer to feel the text through the expressiveness of the music. In Mrs. Keady’s mounting ecstasy, described by Pearse, the link between the visual representation by the painter Burton (Aran Fisherman’s Dead Child, above) and his account is abundantly clear.

Thus, these hymns resembled keening with, however, a more formal melodic structure such as the well-known “Amhrán na Páise,” made famous by the Irish sean-nós—old style, Gaelic—singer Joe Heaney (Seosamh Ó hÉanaí).11 Heaney himself took great pride in these songs and his reclamation of them, explaining that they had been neglected and ignored by the clergy. In their zeal to Romanize Irish Catholicism in the wake of the so-called Devotional Revolution, the reforms instituted by Cardinal Paul Cullen from the second half of the 19th century on other devotional items with the advent of printed prayers, mainly in English, became the order of the day (Larkin 1972, pp. 625–52). Bourke and Lysaght claim: Throughout Ireland, vernacular patterns of spirituality gradually gave way to those imported from continental Europe (Bourke and Lysaght 2002, p. 1399).

The pride that Heaney felt came from his own performance, a successful attempt to make these traditional pieces relevant and acceptable again, which led to their renaissance as popular items in the religious repertoire in the west of Ireland (Williams and Ó Laoire 2011, pp. 89–109). Three laments that might be performed during wakes could include the Marian lament, “Caoineadh na dTrí Muire”, (The Lament of the Three Marys), together with “Dán Oíche Nollag” and “Amhrán na Páise”, (“The Poem of Christmas Eve” and “The Song of the Passion”, respectively). Two religious laments portray the death and crucifixion of Christ, while the Christmas hymn focuses on his birth with the foreknowledge of his death. Religious laments were used by the singer Joe Heaney to publicly symbolize a spirituality that was older and closer to localized vernacular folk religious tradition. After the Irish Catholic Church underwent its reorganization, following the increase in Mass attendance from 1850 to 1870 and on, the pre-existing forms of spirituality began to be seen as superstitious aberrations, in spite of the fact that they had previously been widespread. From the perspective of a theologically minded clergy of the time, drawn largely from the more affluent Anglicized strong-farmer class (Bourke and Lysaght 2002, p. 1399), they seemed inaccurate and ignorant. For enthusiasts of Gaelic cultural traditions, however, the religious songs confirm the importance and central prominence of an independent, local, and vernacular Catholicism. Joe Heaney’s championing of the non-liturgical oral sacred dimension was an attempt to reclaim space for this aspect of the Irish religious experience.

The song—“Caoineadh na dTrí Muire” also known as “Caoineadh na Páise” (The Lament of the Three Marys or The Lament for the Passion)— similar to the text Pearse recorded, can represent a stage between devotional song and lamentation over a corpse (see Figure 3). The character of the Virgin Mary plays a pivotal role in religious laments; even as Mary is a central figure in Catholic liturgy, she is also a central figure in vernacular tradition (Ní Riain 1993, p. 203). Because the religious lament features the central image of Mary mourning the death of her son, her lament is mirrored in the lamenting of the women mourning the corpse of a neighbor or family member.

Figure 3.

One verse of “Caoineadh na dTrí Muire” as sung by Joe Heaney. Musical transcription by Sean Williams; textual translation by Lillis Ó Laoire.

A Pheadair a aspail, an bhfaca thú mo ghrá bán? (Ochón, is ochón ó)Chonaic mé ar ball é dhá chéasadh ag an ngarda (Ochón, is ochón ó)Cé hé an fear breá sin ar Chrann na Páise?An é nach n-aithníonn tú do Mhac, a Mháithrín?An é sin an Maicín a d’iompair mé trí ráithe?An é sin an Maicín a rugadh in sa stábla?An é sin an Maicín a hoileadh in ucht Mháire?A mhicín mhuirneach, tá do bhéal ‘s do shróinín gearrtha.Is cuireadh calla rúin ar le spídiúlacht óna námhaidIs cuireadh an coróin spíonta ar a mhullach álainnCrochadh suas é ar ghuaillí ardaIs buaileadh anuas é faoi leacrachaí na sráideCuireadh go Cnoc Chailbhearaí é ag méadú ar a PháiseBhí sé ag iompar na Croiche agus Simon lena shálaBuailigí mé féin ach ná bainidh le mo mháithrínMarómuid thú féín agus buailfimid do mháithrínCuireadh tairní maola thrí throithe a chosa agus a lámhaCuireadh an tsleá trína bhrollach álainn.Éist a mháthair, is ná bí cráiteTá mná mo caointe le breith fós a mháthairín.

Oh Peter, apostle, did you see my loved one?I saw him some time ago, tormented by his enemiesWho is that fine man on the Cross of Passion?Don’t you recognize your own son, mother?Is that the son I carried for three trimesters?Is that the son that was born in the stable?Is that the son that I nursed at my breast?My dearest little son, your mouth and nose are bleeding.They dressed him in hair mantle with insults from his enemiesThey put a crown of thorns on his beautiful forehead.They lifted him up high on their shouldersAnd threw him down on the flagstones of the street.He was taken to Calvary Hill to increase his sufferingHe carried the cross and Simon following himYou may beat me, but do not touch my motherWe’ll kill yourself and we’ll beat your motherThere were blunt nails put through his hands and feetThere was a spear put through his beautiful chest.Listen, Mother, and don’t be grievingThe women who’ll weep for me have yet to be born.

Heaney’s text is quite close to that sung by Mary Clancy for Pearse in the early twentieth century. His neighbor, Máire Uí Cheannabháin (Mary Canavan), sang this for Angela Bourke [Partridge] in 1975, and broke down during her recitation saying, “I have gone as far as I can… for you’ll understand every mother’s story, for won’t every mother be the same way with her own son? Caoineadh na Páise [The singer’s title for this hymn] distresses me a great deal” (Partridge [Bourke] 1983, p. 168). Mrs. Canavan’s distress echoes that described by Pearse over seventy years previously, showing that the attitude of lament, and the worldview it encompassed, linked these hymns to the more spontaneous free-form keening over the dead corpse.

Although we have included contextual information about women’s performances here, both the example of a keen (by Seán Ó Conghaile) and the example of a vernacular hymn (by Joe Heaney) are based on recordings performed by men. Keening was popularly believed to precipitate death and was thus surrounded by prohibitions and taboos. In common with some other cultures (see, for example, Gilman and Fenn 2019, p. 189), Irish women were less inclined to perform for male spectators outside of the ritual context. The culture of keening being in decline allowed males to perform. Both men, in this case, performed the keening as a response to a request. As noted, notwithstanding the exceptional case of Nicholas Walsh, keening was primarily a woman’s domain, especially where professional mourners were concerned. These two examples, from opposite ends of a continuum of lamenting verses related to mourning rituals, were recovered from men. Ó Conghaile’s familiarity with and suspicion of the emotional register of mourning is relevant here, while Heaney’s championing of the hymns shows a more appreciative attitude conditioned by his status as a performing artist whose “authenticity” mattered both to him and to his listeners. Keening texts were primarily recovered from women, but as tradition changed and the rituals associated with these sung texts have been modified or forgotten, it is no longer easy to answer some of our questions about 18th-century rituals. However, despite the great loss of much of this devotional practice, some of it remained:

The oral tradition of spiritual practice and religious teaching of which women were the chief practitioners became largely unheard of in English-speaking areas, but continued in the Gaeltacht.(Bourke and Lysaght 2002, p. 1399)

Therefore, these two selections allow for at least partial insight into keening and its related spiritual field from a popular vernacular Catholic perspective. The keen itself contains few if any Christian references and remains a paean of praise and personal loss. The hymn or, more properly, the sacred song, is much more considered. Although it draws from the tradition of keening and emphasizes physical suffering, the last lines contain a kind of stoic acknowledgment of the eternity and recurrence of these themes in human experience.

7. Conclusions

The past role of the keening woman in rural Ireland represents that of a powerful spiritual intermediary located in the vernacular and often at odds with official Catholicism. She is also symbolically and liminally located between the living and the dead, between present and past, between male and female because of her postmenopausal status, and between singing and wailing. Her role is one of guidance through a transition, and her presence is essential to each stage of the death ritual. Her performativity was key to popular vernacular Irish spiritual practice, which was increasingly censured in the 19th and 20th centuries so that keening no longer exists; nor does the kind of engaged physical performativity that once characterized it. But her intermediary position at one of the most important life-cycle rituals was crucial in maintaining balance and order in the community at a time of dire upheaval.

Author Contributions

All work, from conception to completion, has been accomplished by both authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Bean (“ban”) chaointe (“khweentjeh”) means “mourning woman”. |

| 2 | See, for example, Cara Delay’s work in Irish Women and the Creation of Modern Catholicism, 1850–1950 (Delay 2019). |

| 3 | “I once heard in West Muskerry, in the county of Cork, a dirge of this kind, excellent in point of both music and words, improvised over the body of a man who had been killed by a fall from a horse, by a young man, the brother of the deceased. He first recounted his genealogy, eulogised the spotless honour of his family, described in the tones of a sweet lullaby his childhood and boyhood, then changing the air suddenly, he spoke of his wrestling and hurling, his skill at ploughing, his horsemanship, his prowess at a fight in a fair, his wooing and marriage, and ended by suddenly bursting into a loud piercing, but exquisitely beautiful wail, which was again and again taken up by the bystanders” (Sullivan 1873, pp. 324–25). |

| 4 | Duanaire Osraíoch, where this passage is quoted in full (in English), is an edited volume of Gaelic song from the district of Ossory in southeast Ireland. The materials upon which the book is based were collected mostly by John Dunne, (Seán Ó Duinn), James Brennan (Séamas Ó Braonáin) at the behest of John G. A. Prim (1821–75) an antiquarian and newspaper owner, from 1864–7. These manuscripts form part of the National Folklore Collection at University College Dublin. |

| 5 | See, for example, the profane merriment of New Orleans Mardi Gras celebrations (Guglielmi 2020). |

| 6 | Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TheAranFishermansChild.jpg (accessed on 27 May 2024). |

| 7 | This was not strictly the case; she is said to have followed some of the old English families in Ireland as well. |

| 8 | This track, “Caoineadh” by Seán Ó Conghaile, is available for listening on the UNESCO recording Ireland: Traditional Musics of Today, track 103; it is also available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uZIibDWULkg (accessed on 4 June 2024). |

| 9 | Patricia Lysaght (1997), ‘Caoineadh os cionn coirp: The Lament for the Dead in Ireland’, Folklore 108 (1997): 65–82. Appendix 1, 78. Compare Henigan (2016), Orality and Literacy, 73, where she reproduces this text without any stanzaic breaks. |

| 10 | In Irish: “Chuir mé siolla den chaoineadh ar téip agus bam haith a chuidigh an dá phionta liom le é sin a dhéanamh. Cheap mé riamh nach raibh mórán bunúis ná céille leis na nósanna a bhain le hadhlacadh na marbh. Mar shampla, ní raibh ciall ar bith leis an gcaoineadh a bhítí ag déanamh os cionn an mharbháin, de réir mo thuarimse. Nuair a bhí mé im’ ghasúr óg is minic a chonaic mé na mná caointe ag cur a sceadamán amach agus olagón acu os cionn coirp. Ba é an chaoi a scanraíodh said mé. Nuair a d’fhás mé suas im’ scorach, thug mé faoi deara, agus mé ag breathnú ar na caointeoirí, nach mbíodh mórán deora ar bith ag teacht óna súile”. |

| 11 | Sean-nós (“old style”) is a fairly new term used to describe unaccompanied songs in the Irish language. Most of the songs are either love songs, laments, or lullabies. Joe Heaney (1919–1984) was widely considered one of the top singers in this style. |

References

- Alidou, Sahawal, and Marijke Verpoorten. 2019. Only Women Can Whisper to Gods: Voodoo, Menopause, and Women’s Autonomy. World Development 119: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Hilary Joyce. 2018. Memory and Legend: Recollections of Penal Times in Irish Folklore. Folklore 129: 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, Angela. 1980. Wild Men and Wailing Women. Éigse 18: 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, Angela. 1988. The Irish Traditional Lament and the Grieving Process. Women’s Studies International Forum 11: 287–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourke, Angela. 2002. Lamenting the Dead. In The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing: Volume IV, Irish Women’s Writing and Traditions. Cork: Cork University Press, pp. 1365–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, Angela, and Patricia Lysaght. 2002. Spirituality and Religion in Oral Tradition. In The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing: Volume IV, Irish Women’s Writing and Traditions. Cork: Cork University Press in Association with Field Day, pp. 1399–420. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, Liam. 2021. ‘The Aran Fisherman’s Drowned Child’ by Frederic William Burton. Available online: https://www.farmersjournal.ie/life/features/the-aran-fisherman-s-drowned-child-by-frederic-william-burton-634434 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Delay, Cara. 2019. Irish Women and the Creation of Modern Catholicism, 1850–1950. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, Lisa, and John Fenn. 2019. Handbook for Folklore and Ethnomusicology Fieldwork. Blooming: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi, Luc. 2020. Finding the Sacred in the Profane: The Mardi Gras in Basile, Louisiana. Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 7. Available online: http://journaldialogue.org/issues/v7-issue-1/finding-the-sacred-in-the-profane/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Henigan, Julie. 2016. Literacy and Orality in Eighteenth-Century Irish Song. London: Pickering & Chatto. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, Emmet. 1972. The Devotional Revolution in Ireland, 1850–1875. The American Historical Review 77: 625–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenauer, Michael, Anne-Katrin Altwein, Kristen Kopp, and Hermann Salmhofer. 2020. Uncoupling Fate: Klotho—Goddess of Fate and Regulator of Life and Ageing. Australasian Journal on Ageing 39: 161–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lysaght, Patricia. 1986. The Banshee: The Irish Supernatural Death Messenger. Dublin: Glendale Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lysaght, Patricia. 1997. Caoineadh os Cionn Coirp: The lament for the dead in Ireland. Folklore 108: 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon, Bryan. 2013. A Pattern from the Past. The Irish Times. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/a-pattern-from-the-past-1.1510978 (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- McLaughlin, Mary. 2019. Keening the Dead: Ancient History or a Ritual for Today? Religions 10: 235. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332089663_Keening_the_Dead_Ancient_History_or_a_Ritual_for_Today (accessed on 15 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ní Riain, Nóirín. 1993. The Nature and Classification of Traditional Religious Songs, with a Survey of Printed and Oral Sources. In Music and the Church. Edited by Gerard Gillen and Harry White. Kildare: Irish Academic Press, pp. 190–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Conghaile, Seán. 1993. Saol Scolóige. Indreabhán: Cló Iar-Chonnacht. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Crualaoich, Gearóid. 1999. The ‘Merry Wake’. In Irish Popular Culture 1650–1850. Edited by J. S. Donnelly, Jr. and Kerby A. Miller. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Giolláin, Diarmuid. 1998. The Pattern. In Irish Popular Culture 1650–1850. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, pp. 201–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. 1980. Duanaire Osraíoch. Dublin: An Clóchomhar. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Madagáin, Breandán. 1981. Irish Vocal Music of Lament and Syllabic Verse. In The Celtic Consciousness. Edited by Robert O’Driscoll. Portlaoise: Dolmen, pp. 311–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Madagáin, Breandán. 1985. Functions of Irish Folk Song in the Nineteenth Century. Béaloideas 53: 130–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Madagáin, Breandán. 2005. Caointe agus Seancheolta Eile: Keening and Other Old Irish Musics. Galway: Cló Iar-Chonnachta. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Muirithe, Diarmaid. 1978. An Chaointeoireacht in Éirinn—Tuairiscí na dTaistealaithe. In Gnéithe den Chaointeoireacht. Edited by Breandán Ó Madagáin. Dublin: An Clóchomhar. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Súilleabháin, Seán. 1967. Irish Wake Amusements. Cork: Mercier Press. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge [Bourke], Angela. 1983. Caoineadh na dTrí Muire: Téama na Páise i bhFilíocht Bhéil na Gaeilge. Dublin: An Clóchomhar. [Google Scholar]

- Pearse, Pádraic H. 1911. Sliocht Duanaire Gaedhilge/Specimens from an Irish Anthology. The Irish Review 1: 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rackard, Anna, and Liam O’Callaghan. 2001. Fish Stone Water: Holy Wells of Ireland. Introduction by Angela Bourke. Cork: Atrium. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Celeste. 2014. The Origins of Ireland’s Holy Wells. Oxford: Archaeo Press, Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Ridge, Anne. 2009. Death Customs in Rural Ireland: Traditional Funerary Rites in the Irish Midlands. Galway: Arlen House. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, W. K., ed. 1873. Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish: A series of Lectures delivered by the late Eugene O’Curry M.R.I.A, Vol. 1. London: Williams and Norgate. [Google Scholar]

- Toolis, Kevin. 2017. My Father’s Wake: How the Irish Teach Us to Live, Love, and Die. New York: DaCapo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gennep, Arnold. 2019. The Rites of Passage, 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Sean. 1998. Constructing Gender in Sundanese Music. Yearbook for Traditional Music 30: 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Sean, and Lillis Ó Laoire. 2011. Bright Star of the West: Joe Heaney, Irish Song-Man. New York: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).