Abstract

Religion is a complex construct that defines not only the historical and social identity of a nation, but also the personal identity of an individual. The attitude towards religion can be conditioned by tradition, political ideology, true faith, education, etc. In our research, we have tried to establish the level of religiousness of the female students of teacher education faculties in Serbia, belonging to the Orthodox Christianity as the dominant confession in Serbia. We examined their attitudes towards some of the moral challenges encountered by believers, including abortion, prostitution, same-sex marriages, the use of cannabis, and euthanasia. Using a snowball non-discriminative online sample of 336 female Orthodox students, we found that the students assessed themselves as above-average religious and that out of three dimensions of religiousness measured in the questionnaire, the lowest scores were recorded for the dimension of the effect of faith on their behavior. The study showed that the level of religiousness is a good predictor of attitudes towards abortion, prostitution, and same-sex marriages, but not towards the use of cannabis. Moreover, religiousness and attitudes towards prostitution are positively correlated, which is directly opposite to religious teachings. This is why a question arises as to whether we can speak about a return to faith or merely a return to the traditional model of manifesting the religious as an antipode to the secular organization in force until 1989. The results of our research point to the latter conclusion.

1. Introduction

The definitions of religiosity and religion are numerous. What they have in common is that in the basis of the religious belief there is a belief in the existence of the supernatural, spiritual, transcendental, or holy being that affects human life, as well as all other happenings in nature and society (Mladenović and Knebl 1999; Šušnjić 1998, p. 56). On the other hand, every religion prescribes, apart from a set of beliefs, certain rituals, and the practice of religion, which constitute a manifestation of every individual’s behavior and religious beliefs. In that respect, religiousness is, and constitutes, the state of spirit “which a believer should have towards the very belief in the being ‘beyond’ and towards the ways of interpreting and defining that being as given by the church organization” (Pavićević 1988, p. 18). Therefore, religion as a human, cultural–historical and social phenomenon, possesses a specific system of ideas, beliefs and practice, representing a specific form of practical attitudes towards the world, nature, society and man (Đorđević 1999). What is more, within the same confession, certain concretizations are established that serve as differentia specifica, e.g., of the nation and the church related to it. Therefore, for example, the Serbian Orthodox Church [SOC] also emphasizes svetosavlje, related to Saint Sava, the founder of the autocephalous SOC, which also serves as an identity feature of the Serbian nation.1

Religious identity is one of the earliest identities, perhaps even the most important acquired identity, within the collective, as well as within the personal identity of each individual. The first religious identity, acquired by children upon birth, is the affiliation to their parents’ confession and thus, the formation of the child’s religious identity proceeds in line with the religion practiced by his/her family.2 Numerous studies point to the connection between parents’ and children’s religiosity, since every form of education starts from the belief that a young person’s conscience and feelings may be affected in a previously determined manner, as well as on the creation and development of certain cognitive, moral, cultural and emotional characteristics of a person (Ljubotina 2004; Matejević and Stojanović 2020), which are primarily developed in the family.

On the other hand, formal education as a socialization factor contributes to the formation and strengthening of religious attitudes and beliefs, most commonly within the religion or confession practiced by the person’s family, which is also confirmed through the “aspiration of religious institutions to achieve the greatest possible influence in formal education” (Bazić 2011, p. 350). In 2001, Serbia’s educational system, from the very first cycle of upbringing and education, introduced the subject Religious Instruction as an optional subject3 (Šuvaković et al. 2023a, p. 3). The link between upbringing and education regarding the formation of the individual’s religious identity is evident in the fact that, at the very beginning of the child’s schooling, the optional subject is chosen not only by the child, but also by the parent(s). At an older age, a child can change the optional subject on his/her own, but those cases are rare.

Furthermore, religion strives to establish norms and criteria in judging different spheres of the life and work of man and given society, not only in the field of upbringing and education, but also of general morality, medical issues,4 as well as various issues opened throughout the history of civilization with the progress of science and technology.5 In fact, religion strives to shape the believers’ determinations6 towards these matters, giving its value framework as a signpost for the formation of the believers’ attitude towards specific matters, including the action component of the attitude (practical acting). Universal questions regarding life, death, and matrimonial union are something that has been long regulated through sacred texts of different confessions, canonized and ritually shaped. On the other hand, modern society legacies and technological progress inevitably impose new dilemmas and challenges, both on believers and on religious communities and leaders. Sometimes the answer to these questions is not easy to give either to believers or religious communities. Some of the moral dilemmas posed to believers in modern society and its legacies are the attitudes towards women’s right to abortion, as well as euthanasia, prostitution, same-sex marriages, and cannabis legalization.

Abortion is a medically assisted termination of pregnancy that can take place based on the pregnant woman’s will or spontaneously. Yugoslavia legalized abortion during the socialist period in 1952 and it was seen as an expression of women’s emancipation, so that this right was also included in the Constitution of the SFR Yugoslavia from 1974 (Article 191). To date, this right of women in Serbia or in other parts of ex-Yugoslavia has not been disputed. This has remained a right guaranteed by the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia from 1990 (Article 27) and the applicable Constitution of the Republic of Serbia from 2006 (Article 63). The attitude of the SOC towards abortion could be divided into three components: we condemn (cognitive component of the attitude), we state that we are against, we appeal against abortion (conative component of the attitude), but we do not actively suggest the prohibition (the absence of the action component of the attitude).

The attitude to this issue differs depending on religious, social, cultural, and political circumstances. Large religious communities mostly oppose this way of terminating pregnancy, stigmatizing it further in language terms. For example, the Seriban Orthodox Church uses the term infanticide for abortion.

It is well-known that some countries, citing different reasons and principles, have legalized euthanasia (Gajić 2012; Grove et al. 2022; Verbakel and Jaspers 2010). According to religious dogmas, both birth and death are God’s will, and any intervening in that process is treated as sinful and heretic. In the context of most religions, and definitely in the context of Orthodox Christianity, euthanasia may be considered a violation of the basic religious dogma about man’s right to life and to the deprivation of life by another man, as well as by the individual (suicide), regardless of the reasons that may lead to it. As such, it has been the focus of research not only in the area of theology, sociology, psychology or ethics, but also in both legal and medical sciences. Euthanasia is mostly defined as the application of a lethal medicine by medical staff, with the prior voluntary consent of the individual (Materstvedt et al. 2003), but it may also be seen as a murder out of mercy or as an assisted death such as the induction of painless death in a patient with an incurable illness (Marić 2001). Modern medicine recognizes the following five forms of euthanasia: giving analgesics in doses that may lead to a fatal outcome; limitation or complete absence of treatment or reanimation; turning off of the artificial life support apparatus; actively assisting the patient to commit suicide; and the injection of a lethal substance (Gajić 2012). Moreover, euthanasia may be voluntary, where there is the patient’s desire and active consent to terminate his own life, and involuntary, where the patient’s consent cannot be obtained, for example, in the cases of patients in comas or children with a major psycho-organic deficit upon birth. In these cases, the request for euthanasia is submitted by parents, relatives, or custodians (Gajić 2012; Kodish 2008). In Serbia, euthanasia is a criminal offence for which a prison sentence from 6 months to 5 years is stipulated (Gajić 2012).

In socialist Yugoslavia, prostitution was criminalized as of 1947 and treated as an offence committed by the “person” who submits to it. The greatest novelty of the socialist legislation is that prostitution is no longer an offence associated solely with a woman but can also be practiced by a man. The amendments to the Law on Public Order and Peace of Serbia from 2016 stipulate punishment for the offence committed not only for the provider of services and for the provision of the space intended for prostitution, but also punishment for the user of prostitution services.

Homosexuality was decriminalized in Serbia as early as 1994, while after 2000, a whole series of acts were enacted, prohibiting discrimination based on sexual or gender orientation. According to the applicable Constitution of the Republic of Serbia from 2006, marriage is supposed to be entered upon by a man and a woman. According to the Family Law of Serbia from 2005, last amended in 2015, marriage is “a legally organized union of the life of a woman and a man”. It is impossible to enter a same-sex marriage in Serbia, in contrast to a rather small number of countries that allow it7. In Serbia, there is definitely a very strong LBGT+ movement demanding it, including Prime Minister Ana Brnabić, who openly expresses being a member of this movement. Debate on this issue involves the entire society, including the academic community, and it was particularly provoked by the Draft Law on the Same-Sex Unions from 2021 (see Antonić 2021; Čović 2021; Šuvaković 2021; Vuković 2021) which, after stirring the whole of Serbian society, was withdrawn from the procedure. Strong but diplomatically shaped resistance to it was expressed by the SOC which, with the support of the Roman Catholic Church in Serbia and the Islamic community, opposed the adoption of such a regulation. According to the Marriage Rules (1994) of the SOC (an Orthodox Christian marriage is defined as “a sacred secret by which two persons of opposite sexes, in the manner prescribed by the Church, enter a union with the life-long spiritual and bodily ties, for the sake of the complete life community, and having and upbringing children”.

Cannabis legalization is yet another open social issue in Serbia. According to Serbia’s legislation, cannabis is considered a psychoactive substance, the cultivation and circulation of which is a criminal act. In Serbia, mere possession of opiate drugs and psychoactive substances “in a smaller quantity”, “for personal use”, is the subject of criminal sanctioning. In the academic community, it is possible to find different views (Radulović 2008; Risimović 2018; Vasiljević Prodanović and Denčić 2021) that state pro et contra arguments regarding this issue, whereas the purpose of legalization is also taken into account, for example, whether it is solely for medical purposes or for “recreational” purposes, as well. To date, the SOC has not expressed an opinion on this issue.

Our research is aimed at establishing whether the level of religiosity and attending religious instruction classes at earlier schooling levels, with other socio-demographic determinants, may be a predictor of the attitudes of Orthodox Christian female students of teacher education faculties in Serbia towards social issues that may also have an Orthodox moral character. This is of particular importance because the respondents will also participate in the process of socialization, in the upbringing and education of new generations, and because religiosity is one of the earliest factors of the personal identity of an individual and group, and is acquired at a very early age, and transferred and shaped due to different socialization agents, including school.

2. Materials and Methods

Virtual, exponential non-discriminative snowball sampling was applied (Parker et al. 2019). The sample included 336 female students of TEFS basic and master studies who self-reported as Christian Orthodox believers, aged 19–40 years (M = 22.4, SD = 4.10). In Serbia, the teaching profession is predominantly female (91% of the total university student population are female students (RZS 2021)). Grammar school was completed by 26.6% of the students and 73.4% completed some of secondary vocational school. Data in relation to the years of studying are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Percentage of the female students in relation to years of study.

The data were collected via a survey that was made available online to the students and the completion of which was voluntary and anonymous. A link to the survey questionnaire was forwarded to the students of TEFS through social networks, student social groups, faculty websites, etc. Several dozen access points for the questionnaire were provided.

The questionnaire used in this research included:

1. socio-demographic questions about the students’ age, year of study, department/majors, previous education, and Religious Instruction attendance;

2. religiosity scale (Ljubotina 2004). In our research, we opted for this approach and in determining the level of the university students’ religiosity we used the scale of religiosity assessment which was constructed and reduced by Ljubotina (2004), based on the theoretical concept of Glock and Stark (1965). The religiosity scale originally had five dimensions of religiosity (belief, ritual, experience, knowledge, consequences) and contained 32 statements. Using the factor analysis, Ljubotina established the presence of three dimensions contained in 24 items. The first dimension is spirituality, which denotes belief and religious experiences of an individual (I sometimes feel the presence of God or a divine being). Religiosity is presented as a personal choice and may be perceived as a primary aspect of religion. In general, in sociopsychological terms, we can see it as intrinsic religiosity in a narrower sense. Of all subscales, spirituality can be considered the most important because it is universal for all religions and is not related to confessional affiliation. It is dominantly permeated by internal motivation and based on the importance of religion in an individual’s life, internalized beliefs, and religious feelings, as well as specific religious experiences. In this specific context, religiosity is mainly considered an individual’s personal choice and a question of the freedom of will. Moreover, it may be assumed that a person who achieves a high score on this dimension will perform religious duties and rites, but that the connection is not necessarily high. This subscale of the religiosity scale is, in motivational terms, of a mixed type, since an individual may be motivated by both internal and external reasons when it comes to familiarity with religious rites and ceremonies and active participation in them, as well as the practice of them. Religious rites may be attended not only for the sake of spirituality and beliefs, but also for other reasons such as meeting the expectations of others in the environment, better social integration, and observance of tradition and customs of the group someone belongs to (e.g., nation, family, school, place of residence etc.). This fact should be kept in mind since, throughout the history of the Serbian nation, the SOC has been the pivot of national gatherings and unity, but also the organizer of school, healthcare, and cultural activities in general. Considering this fact, as well as that the dimension itself is mostly based on the behavioral aspects of an individual’s attitude regarding religiosity, such as knowing, performing, and attending religious rites and practices, does not necessarily point to an (un)integrated believer. This dimension essentially shows the degree in which a person performs rites and rituals prescribed by the religious community to which he belongs (I go to church regularly). The influence of religion on behavior is the third domain, where the adoption of certain rules and dogmas, and their internalization and application constitute one of the aspects of religious behavior. It refers to the degree of application of religious principles in an individual’s everyday life and activities that are not related to religious rituals (I do not approve of marriage to a member of a different religion).

Each sub-scale has eight items, two of which are scored reversely. The result range in the original version of the scale was from 0 to 72, since the respondents answered on the scale from 0—completely false, to 3—completely true. In our research, we used five-degree Likert scale (from 1—I don’t agree at all, to 5—I completely agree). It this manner of assessment, the scores reached on the scale ranged from 24 to 120. The higher result on the scale points to the higher level of religiosity.

The reliability of the religiosity scale in our study, as well as in earlier studies (Matejević and Stojanović 2020), and also Takšić and Kalebić Maglica (2023), resulted in a very high Crombach α = 0.96, amounting to Crombach α = 0.94, while Gojković et al. (2019) obtained the value of Crombach α = 0.91. If we look at the reliability of the subscales, in our study we obtained Crombach α = 0.94 for the spirituality subscale (Ljubotina 2004) Crombach α = 0.94; Bijelić and Macuka (2018) Crombach α = 0.95; Takšić and Kalebić Maglica (2023) Crombach α = 0.96), Crombach α = 0.88 for the rites subscale (Ljubotina (2004) Crombach α = 0.91; Bijelić and Macuka (2018) Crombach α = 0.90; Takšić and Kalebić Maglica (2023) Crombach α = 0.93) and Crombach α = 0.75 for the behavior subscale (Ljubotina (2004) Crombach α = 0.78; Bijelić and Macuka (2018) Crombach α = 0.82; Takšić and Kalebić Maglica (2023) Crombach α = 0.79).

3. attitudes towards issues regarding some of the key religious–moral dilemas:

- (a)

- abortion—A woman should have the right to abortion;

- (b)

- prostitution—Prostitution should be legalized;

- (c)

- same-sex marriages—Same-sex marriage should be legalized;

- (d)

- use of cannabis—Cannabis should be legalized;

- (e)

- euthanasia—Euthanasia should be legalized.

The above-listed attitudes were assessed on the five-degree Likert scale (from 1—I don’t agree at all, to 5—I completely agree).

The independent variables in this study were as follows: year of study, the type of the secondary school completed (grammar school or secondary vocational school), whether the respondents attended religious instruction, the level of the students’ religiosity (the total score, as well as the results achieved on subscales of spirituality, rites and behavior).

The dependent variables were as follows: attitudes towards abortion, prostitution, same-sex marriages, cannabis, and euthanasia.

The data were obtained by SPSS 22, by descriptive statistics, t-test for independent samples, ANOVA, linear regression (model ENTER).

3. Results

Table 2 shows the basic indicators of descriptive statistics for the attitudes towards social issues that may also have an ethic-religious character, and their relation to the measured total score of religiosity, as well as the subscales of religiosity. Since the arithmetic means obtained on the total religiosity score and on all subscales are higher than the theoretical value (M = 2.50), we may conclude that Orthodox Christian female students in Serbia are above-average religious, particularly regarding the spirituality subscale.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the attitudes towards social issues that may also have an ethical–religious character and for the religiosity scale.

It has also been shown that out of five social issues that may have an Orthodox moral character, the Orthodox Christian female students had the most positive attitude towards abortion, and the most negative towards prostitution.

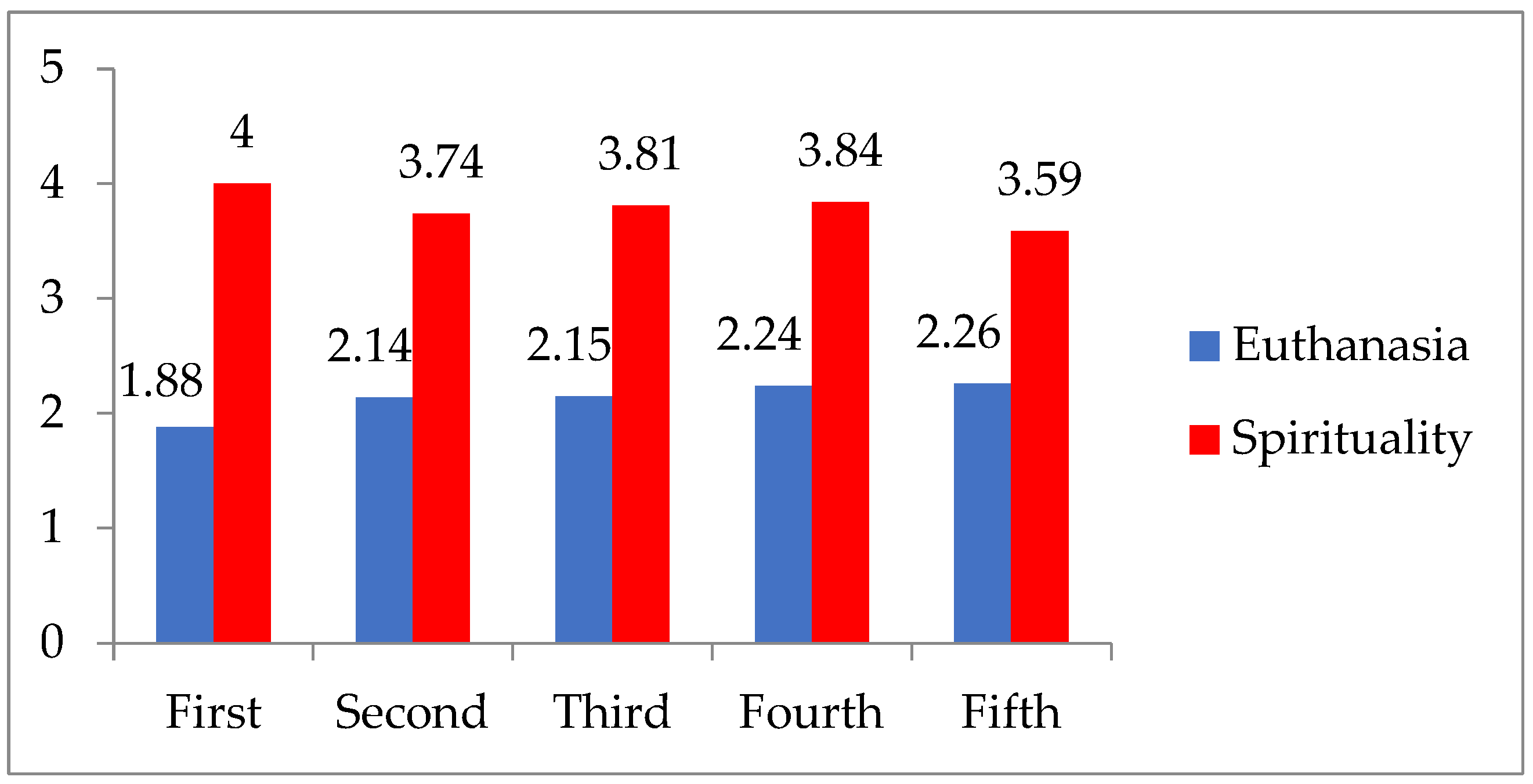

The youngest students opposed euthanasia on the largest scale, while the oldest group supported it (F = 2.216, p < 0.05). The oldest group also achieved the lowest scores on the spirituality scale, while the youngest group had the highest scores (F = 2.595, p < 0.025). These data are graphically presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The relationship between the year of study and the attitudes towards euthanasia and the spirituality dimension.

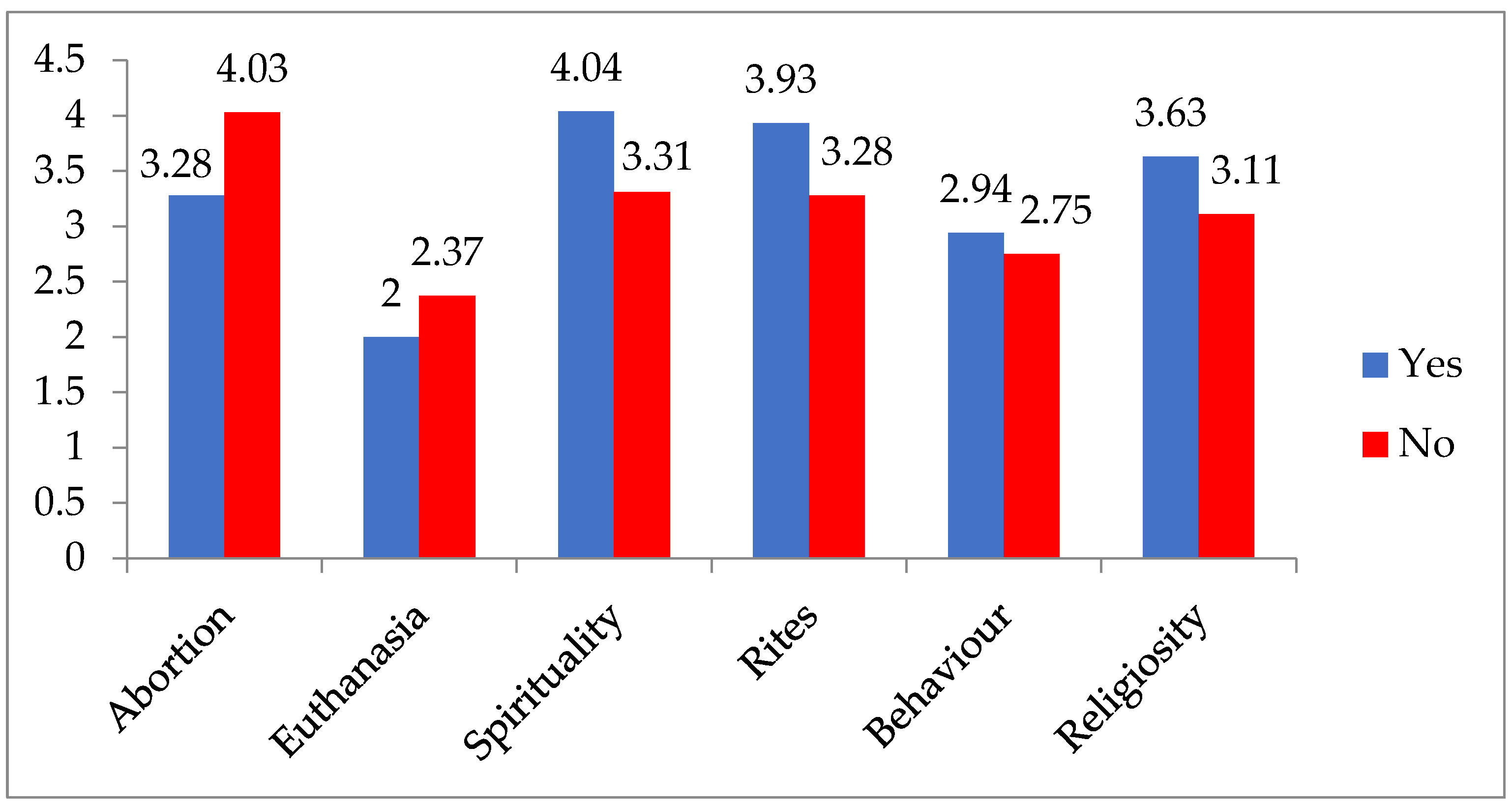

Speaking about the previous religious education, as many as 73% students attended Religious Instruction in previous schooling periods, and there are also statistically significant differences between the students who attended Religious Instruction and those who did not when it comes to the attitudes to abortion (t = −4.703, df = 212.834, p < 0.000) and euthanasia (t = −2.249, df = 174.143, p < 0.026). Differences were also established regarding the total score on the religiosity scale (t = 5.648, df = 169.855, p < 0.000), but also on all the pertaining spirituality subscales: spirituality (t = 5.591, df = 158.989, p < 0.000), rites (t = 5.908, df = 168.353, p < 0.000), behavior (t = 2.368, df = 200.010, p < 0.019), which is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Differences regarding the attitudes towards social issues that may also have a dogmatic, religious character and the religiosity scale of Christian Orthodox female students regarding the religious instruction attendance.

The data obtained by linear regression show that the total score on the Religiosity Scale, as well as on all its subscales, is a significant predictor of the attitudes to different phenomena related to religious morality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of linear regression.

4. Discussion

In our study, we found that the Orthodox Christian female students of the teacher education faculties in Serbia are above-average religious, which is not in line with the results of the previous study (Matejević and Stojanović 2020) conducted among the students of both sexes at different faculties throughout Serbia. Moreover, the obtained data are also in line with those of the RZS (2022) stating that 90.86% citizens declare themselves believers (out of these, 93.55% are Orthodox Christians). On the other hand, a particularly high score regarding the spirituality subscale in our study points to the domination of the internal component of religiosity, which was confirmed, although not as intensely, in the study by Matejević and Stojanović (2020). Some of the studies confirming the obtained results should be sought in the countries formed after the breakup of ex-Yugoslavia, and they show an increased level of religiosity of the generations born after the breakup of socialist Yugoslavia (Dušanić 2007; Marinović Jerolimov 2002; Tešanović 2012). Namely, in ex–Yugoslav countries, the ethnic identity at the same time determines the religious identity and vice versa, so that the changes in the social system, government organization and civil wars from the last decade of the 20th century also had a religious component. War, which is definitely a high-risk life event for the inhabitants of the war-stricken region, causes an extremely high level of stress in an individual and leaves permanent consequences on his life in all its aspects, so that the increasing level of religiosity is not unexpected. Numerous studies have shown that in periods of great life crises and uncertainties, an individual turns to God and religion, seeking help, salvation and comfort (Begović 2020; Bentzen Sinding 2021; Pirutinsky et al. 2020). Moreover, the previous research results also suggest that a person’s sex is a significant factor in predicting religiosity; women are more religious than men (Anić 2008; Bakrač 2016; Đorđević 1984), which may be yet another reason for their above-average religiosity, considering that our sample consisted exclusively of women.

Out of five social issues that may also have an Orthodox-moral character, the Orthodox Christian female students have the most positive attitude towards abortion and the most negative attitude towards prostitution. The Orthodox Christian female students’ positive attitude towards abortion may be interpreted by the emergence of the “abortion culture” (Rašević and Sedlecki 2011), which has been present in Serbian society for many decades. The corroboration of this culture in practice is found in data from the Batut Institute (Batut 2023a) indicating that even today, 70 years after the legalization of abortion, every fifth pregnancy in Serbia is terminated electively8; moreover, this trend neither decreased nor oscillated in the past, despite the fact that different contraceptives became more available to women and that their educational and socio-economic status is far higher than back in the 1950s. On the other hand, it cannot be assumed that a significantly higher number of women opted for abortion to preserve their own life and health, or as the the result of a larger number of fetuses with different genetic predispositions and deformities. Furthermore, it should be kept in mind that girls in Serbia have their first sexual experience on average at the age of 15 (Batut 2023b) and that there is a decreasing tendency in the age of girls’ first sexual experiences9. It should also be taken into account that, since 1981 in Yugoslavia, not only has instrumental abortion been available (in the form of a surgical intervention), but also abortion with the aid of medicament therapies, which are substantially simplified and more comfortable for women (Kampadžija et al. 2010). A possible explanation is that a substantial number of the respondents were directly (they had an abortion) or indirectly faced with abortion (their mothers, sisters, neighbours, friends) and that a different attitude would result in self-accusation or accusation of their close persons. The various forms of advocation and action of the SOC, through epistles and public expression of negative attitudes towards infanticide have not contributed to any decrease in this trend, nor has insisting on church sanctions in the form of suspending the possibility of communion10. The SOC appeals against abortion, manifested in its epistles, mostly address women and, to a smaller extent, men, in certain terms abolishing their responsibility. A different approach to the sexes for the same violation can also be seen in the case of prostitution. However, when it comes to the condemnation of prostitution by our respondents, we believe that two important factors should be taken into account: first, that all the respondents are female and that no woman would generally like her boyfriend or future husband to have sex with prostitutes and, second, that prostitutes are a marginalized and stigmatized social group. In addition, prostitution is legally sanctioned in Serbia.

The result that the youngest group of students opposed euthanasia on the largest scale, while the oldest group of students supported it to a larger extent, can also be connected to the finding that the oldest group of students also achieved the lowest scores on the spirituality scale, while the youngest group of students had the highest scores on this scale. This finding can be explained by the fact that, since 2001, Serbia has had Religious Instruction as an optional subject and that since that moment the impact of religion in the socialization process (not only of the SOC but of other confessions as well) has become far more significant. Life is a supreme value in Christianity in general, God’s gift, about which man is not entitled to decide, and that suicide (euthanasia may also be seen as a form of assisted suicide) is considered a mortal sin. The influence of attending Religious Instruction by a large number of the students (73% respondents attended Religious Instruction at previous levels of schooling) could also contribute to the differences in the attitudes towards abortion and euthanasia. As a matter of fact, the Orthodox Christian female students attending Religious Instruction had a more negative attitude towards abortion and euthanasia compared to those who attended Civic Education as an optional subject.

Furthermore, the Orthodox Christian female students who attended Religious Instruction show a higher level of religiosity in general compared to the students who did not attend Religious Instruction. The difference largely referred to the spirituality scale and the familiarity with church rites, which constitute the elements of internal religiosity, while the difference regarding the impact of religion on behavior was the smallest. It seems that the syllabus and the teaching method applied by Orthodox Christian teachers of Religious Instruction was predominantly directed towards the recovery of spirituality and an individual’s return to God and the basic values of Christianity, as well as with the recovery of a culture familiar with religious customs, and far less towards determining rules by which an individual should act. On the other hand, the SOC is trying to turn the attention of the teachers of Religious Instruction to the importance of catechism, emphasizing that “it is unimaginable that someone may enter the Church without any knowledge or catechization” (Krstić 2012); however, there is an awareness that a large share of believers have no catechization or, in the best case, only an elementary catechization. That is why the teachers of Religious Instruction should pay attention to the fact that these two processes are not mutually exclusive, but must take place concurrently. “Schoolchildren are not completely determined for faith—they should become interested in it, which is not implied by the parish catechism, because a parish should work with people who have not yet made a decision about their faith and who are conscious Christians. In one process, the emphasis is on missionary activity, while in the other the emphasis is on the introduction into the secret of the Church” (Krstić 2012). Previous studies also speak in favour of the thesis that the young attending Religious Instruction, regardless of their confessional affiliation, manifest a higher degree of religiosity (Dušanić 2007; Šuvaković et al. 2023b).

The linear regression results point to several other data:

- Religiosity and its dimensions are not a significant predictor of the attitude towards the legalization of cannabis use;

- The greatest significance in predicting the attitudes towards dogmatic questions was scored on the spirituality scale, while behavior was the weakest predictor;

- There is a certain difference in relation to the attitude towards prostitution legalization over Orthodox moral issues, no matter whether the scale is observed on the whole or in relation to dimensions. Unlike other observed attitudes, the score on the prostitution scale positively correlated with religiosity, i.e., with the higher score on religiosity and its dimensions, the attitude towards prostitution legalization was more positive;

- The only significant predictor of the attitude towards euthanasia legalization was the score on the rites dimension.

The linear regression shows that the total score on the religiosity scale proves to be a statistically significant predictor of attitudes towards abortion, prostitution, same-sex marriages and euthanasia. The obtained results are in line with Sretenović’s (2013) attitudes that religious persons will have a more negative attitude abortion, and with the results obtained by Takšić and Kalebić Maglica (2023), who used a sample of the students in Croatia and determined that more religious students had a more negative attitude towards homosexuals. Previous studies also show that the motives for choosing euthanasia and the reasons for its approval and execution are closely connected to religious principles and beliefs (Sharp 2018), but also with the level of an individual’s religiosity, so that an individual’s higher level of religiosity is directly connected with resistance towards opting for and legalizing euthanasia (Chakraborty et al. 2017; Verbakel and Jaspers 2010). In Serbia no research on the population has been recorded regarding the attitude towards euthanasia, but the data in Catholic countries formed after the break-up of former Yugoslavia, i.e., Croatia and Slovenia, suggest that there is still a number of people advocating for euthanasia legalization—30% in Croatia and as many as 50% in Slovenia (Verbakel and Jaspers 2010). In contrast, Grove et al. (2022) indicate that 84% of the world population declare themselves as believers, out of whom 32% belong to different forms of Christianity, and that the positive attitude towards euthanasia prevails mainly in countries with majority Christian populations.

The attitude towards cannabis is something that is not prescribed by religious dogmas in Orthodox Christianity, although the SOC is declaratively against all the phenomena leading to the decomposition of the Christian family such as addiction diseases. Drug addiction, as one of those diseases, inevitably leads to the destruction not only of the individual—the drug addict—but also harms and destroys the whole family. Accordingly, the SOC has organized addiction treatment centres within several monasteries, where not only do families seek help but also the drug addicts themselves, after having failed at attempts to fight addiction with the aid of conventional medicine. The obtained results about religiosity and its dimensions not being a significant predictor of the attitude towards the legalization of cannabis use is not in compliance with the results of previous studies (Bahr et al. 1998; Gorsuch 1978; Engs and Mullen 1999; Kharari and Harmon 1982) indicating that religiosity is negatively associated with marijuana abuse. Nevertheless, it should be taken into account that these are relatively older studies and that the believers’ consciousness is affected not only by the church teachings, but also by different socialization agents, including today’s omnipresent mass and virtual media, and social system ideology, etc.

On the other hand, the results of studies conducted as early as the 1990s point to the high presence of drug abuse among young people in Serbia. Radulović (2008, p. 125) interprets this phenomenon as an imitation of the Western models of behavior and lifestyle by young people from families that are social elites, considering it a characteristic of all former socialist countries of that time. Milić (2000) refers to the family as one of the main causes of this phenomenon but, on the other side, also the institution that suffers consequences. The destruction of the system of family values begins with the break-up of Yugoslavia and is caused by increased absence of father from the family home (due to wartime events and the social-economic crisis after the introduction of economic sanctions) and basic insecurity of mother, who also assumes the father’s role and additional care for the family. This, in turn, leads to the parents’ conciliatory attitudes regarding the use of various psychoactive substances by their children, where “parents are pleased because their children have a new kind of entertainment” (Milić et al. 1997, p. 40) and where parents do not see the danger of family destruction that is caused by their children’s slow but inevitable fall into drug addiction. The data obtained on the sample of primary and secondary-school students aged 14-16 show that drugs are used more frequently by boys, that there is often a combination of drugs and alcohol, and that information about harmful consequences of drug consumption is mostly obtained through means of public information (Milić 2000, p. 51; Radović et al. 2010, p. 617). Every second respondent says that he/she knows someone who consumes some type of drug, whereas 6.4% (Milić 2000, p. 51) and 7.4% (Radović et al. 2010, p. 618) of the young people admitted having consumed specifically cannabis. This trend did not change either in 2008 or in 2019, when the percentage amounted to 7.3% (Batut 2020, p. 44). According to the Batut research results from 2019 (Batut 2020) regarding secondary school freshmen born in 2003 (which coincides with the age group in our sample), cannabis is the most frequently used drug, while an additionally concerning fact is that 29.5% of these students had an opportunity to try cannabis, although they did not do it, whereas 25.1% believe that they could get cannabis very easily (Batut 2020, pp. 24, 28). Furthermore, this research shows that the use of cannabis is seen as the least harmful (the perception of harmfulness of cannabis use decreased from 77% in 2008 to 64% of the respondents in 2019, p. 47). There are also sex-based differences in the reasons why young people resort to drug use: boys most commonly use drugs due to peer pressure while girls do it out of curiosity. Milić observes two widespread and concerning attitudes: the first one is that young people think that they can stop using drugs of their own free will; the second is the attitude of the parents, who are indifferent and uninterested, although they are directly familiar with the fact that their children use drugs. Milić notes that “the addiction syndrome is a set of physiological, behavioral and cognitive phenomena in which the use of a substance gains greater importance for a person than some other behavior patterns which used to have their value in the past” (Milić 2000, p. 49). In contrast, Radović et al. (2010, p. 618) point out that the family’s material status is a relevant parameter for drug abuse: young people from families with higher earnings are more inclined to consume narcotic drugs (more than 50%), whereas among drug consumers there is no statistically significant difference regarding whether they live in a complete or incomplete family. Mandić Gajić (2008) believes that society’s pathology is most diversely reflected in children and young people of that age, who often grew up in dysfunctional or destroyed families. Moreover, it should be kept in mind that during the 1990s and 2000s there were numerous social circumstances reflected in all the layers of society and that families were destroyed and became dysfunctional not solely through voluntary decisions of the family members (parents in the first place), but also through circumstances, such as wars, sanctions, the failed privatization and restitution processes leading to mass redundancies, that threatened the existence both of individuals and families. On the other hand, young people are characterized by hedonism, desire to experiment and belong to their peer group, are curious, and rebel against authorities and tradition without firmly established value systems and the patterns of a healthy lifestyle. Drugs are seen as a suitable means for showing one’s own maturity, fearlessness or nonconformity, as an initiation into adult company, as well as a means of confirming and strengthening their own affiliation to certain social groups or subcultures (Radulović 2008). That is why young people are the most susceptible subpopulation to all forms of risky behavior and acceptance of new challenges in general (Williams et al. 2008), especially in the situation when the overall system of social values in a group of countries has been destroyed and overturned contrary to those values on which former generations were socialized, which is the process of transition (Šuvaković 2014, pp. 11–26). However, certain traces of the recovery of society, as well as family, should be sought in the information from 2019, according to which 85% young people think that their parents would not allow the consumption of cannabis (Batut 2020, p. 37). The reasons for this change in the parents’ orientation may be parents’ increased awareness and information about the harmful effects of consuming psychoactive substances, examples of destroyed families and the devastation they may have witnessed in the life of an addict in their own environment. It may also be the consolidation of a value system, which is also corroborated by the majority choice of Religious Instruction as an optional subject (73%) made by parents on behalf of their children who declare themselves to belong to Orthodox Christianity.

As for the predictive values of the religiosity subscales in relation to the analyzed attitudes, the greatest predictive significance was recorded on the spirituality subscale, and the lowest on the subscale of behavior impacts. It was found that, according to the score on the spirituality subscale, it was possible to predict the respondents’ attitudes towards abortion, prostitution, and same-sex marriages. According to the score on the rites scale, it is possible to predict the attitudes towards abortion, prostitution, same-sex marriages, and euthanasia. According to the scores on the subscale of the impact of faith on behavior, it is possible to predict the respondents’ attitudes towards abortion, prostitution and same-sex marriages. Therefore, we may conclude that, when it comes to abortion, same-sex marriages and prostitution, there is agreement among all three components of the religiosity dimensions. The students who are religious on a larger scale, with high internal religiosity and pronounced spirituality dominated by unquestionable faith in God, who adhere to Orthodox Christian rites and customs, and who try to harmonize their lives with the rules of religion and to respect religious rules and dogmas not only at the spiritual, or internal, but also at the manifest, external level, through self-regulation of their own behavior and attitudes towards the environment (behavioral component) in line with the rules of religion, have a negative attitude towards abortion and same-sex marriages, but a more positive attitude towards prostitution legalization. In fact, it transpired that there was a certain difference in the respondents’ attitude towards prostitution legalization from their attitude towards other Orthodox moral issues, no matter whether the scale is seen on the whole, or in relation to the dimensions: unlike other Orthodox moral attitudes, the score on the prostitution scale correlated positively with religiosity. This may be associated with Christian mercy and forgiveness, although here it should not be overlooked that in the total score, regarding all posed social issues that may potentially pose a moral dilemma, the students’ attitude towards prostitution was the most negative one. On the other hand, when it comes to abortion, there is a direct prohibition within the SOC, which is manifested in various ways (epistles, church punishments, divorce of the marriage concluded by the SOC rules etc.), but it does not seem to be of great significance to the female students. Homosexuality is given different names by the SOC officials: a disease, plague, fad, the greatest mortal sin, “Sodom and Gomorrah”, and is treated in an accusatory and stigmatizing manner. In fact, in the several past years slightly less sharp qualifications have been recorded, although with the same meaning.

Regarding euthanasia, the only significant predictor of the attitude towards the legalization of euthanasia was the score on the rites dimension. The students’ negative attitude towards euthanasia, with greater importance given to the dimension of the importance of religious rituals and rites, can be explained by three reasons. The first is the tabooization of the process of dying, i.e., the attempt to forget and hide death, the process of dying, and the dying ones, for fear of negating an individual’s own omnipotence (Krstić n.d.). The second reason is the dogmatic Christian question of repentance, while the third refers to an individual’s right to death. In fact, an individual’s “right to death”, or an individual’s decision about how and when to die, is not, in ritual terms, an exclusively individual matter, but also a matter of the community and the individual’s immediate environment. Suffering from a disease and dying, as processes of a certain length confer upon an individual the time and space to redefine the meaning of his/her own life and to see, in retrospect, the turning points and decisions in his/her life (Krstić n.d.). Thus, in line with basic Christian theses, there is also the time intended for repentance, confession, reconciliation with conscience and the opportunity for asking for forgiveness in earthly life, so that the person will be given forgiveness in the otherworldly life. Moreover, one’s own decision about terminating life can be implicitly interpreted as a kind of suicide, which, according to Christianity, is a mortal sin (in Orthodox Christianity, those who commit suicide do not have right to funeral rites) because a man assumes the right to take away something that is not his own but given by the Creator. In the same vein, working actively towards one’s own death excludes the possibility of God’s providence and belief in miracles. In psychological terms, the process of dying may also be seen in the context of the closest people saying goodbye to the dying person, in the function of facilitating the psychological mechanism of grieving and preparation for the departure of a loved family member or a friend, and our opportunity to ask for the dying person’s forgiveness for any injustice done to him/her, and not only the dying person’s opportunity to ask for our forgiveness for his/her own actions (failure to act). Seen from that perspective, the most important events in an individual’s life—birth, marriage, and death—also have a certain dose of stressogenicity for the individual himself, but also a broader significance for his environment and the community to which he belongs. Thus, the rites and rituals related to these events constitute a socially (and religiously) acceptable way of regulating intensive emotions that appear in the individual on those occasions.

Since our study on the topic of religiosity and its relationship towards some Orthodox moral issues among the SOC believers is one of the less frequently conducted studies, it was difficult to compare data with the results of previous research, particularly because, in our research of religiosity, we opted for the quantitative approach. On the other hand, attitudes towards Orthodox moral issues have been researched more frequently, but without connecting them with the religiosity concept. Future research directions might include researching the religiosity of medical staff and measuring their religiosity and attitudes towards some of the research questions in this study or other issues (e.g., sex change, in vitro fertilization, embryo preservation etc.). These issues have already provoked contention in the postmodernist interpretation of religiosity. This may lead medical staff to their own self-examination regarding the attitude towards religion and/or rules of their profession, and even towards choosing between conscience and keeping their jobs. Naturally, it is always possible to replicate research in different age groups for the purpose of comparing the results regarding religiosity and attitudes, as well as on the samples of different confessions in the Serbian population since, although predominant, Orthodox Christianity is not the only religion present in Serbia. It may also be a limitation of this study—it would be useful to see the attitudes of the members of other religious communities in Serbia (which are a substantial minority according to the latest census) towards the legalization of these five social phenomena. In that manner, we would gain a clearer insight, from the believers’ perspectives, into how different religious communities see the trends and dilemmas of contemporary society. On the other hand, each of these phenomena is complex in itself and may be elaborated on in detail individually, with or without relating to the religiosity level, in the sample of Orthodox believers. The issues of limiting the right to abortion regarding the manner of its execution, age limits, legal limitations, age limitations of the fetus and mother, post-abortion psychological support to women, researching the attitudes pro-life and pro-choice in the context of religion, as well as providing psychological support to medical staff assisting in euthanasia, regulating medical practice in the realization of euthanasia, the possibility of donating organs of the people who consented to euthanasia, attitudes towards surrogate motherhood and the adoption of children by same-sex partners, attitudes towards pedophilia, attitudes towards male prostitution, attitudes towards rehabilitation centres for addiction diseases within church communities, might also be included in this study, either in the form of individual attitudes, or in the form of questionnaires and assessment scales. Moreover, the fault of this research is the insight into the cognitive component or religiosity; it would be also interesting to see whether a high degree of religiosity is really accompanied by the high knowledge of the Holy bible and catechesis, or whether Orthodoxy in Serbia is still at the level of “four rites believer” (Đorđević 2009, p. 62) and the individual observance and practice of the customs by one’s free choice, which is also indicated by the SOC. Furthermore, the limitation of the research is in the absence of male respondents and the sample being limited only to those students studying while working simultaneously in schools and kindergartens, or with the youngest ones, no matter how much that profession is in the process of transferring knowledge to future generations.

5. Conclusions

Our research was dedicated to the exploration of the impact of the religiosity level and of attendance of Religious Instruction at previous levels of schooling on the attitudes of schooling Orthodox Christian female students at teacher education faculties in Serbia towards some Orthodox moral issues. Researching this topic is extremely important since the respondents will also participate in the process of institutional socialization of new generations. As a matter of fact, we keep in mind that religiosity, as one of the oldest factors of personal and collective identity, which is acquired quite early, is transferred and shaped thanks to different socialization agents, including school. Religiosity also manifests itself in different habits and attitudes and may lead to religious exclusion, not only towards other confessions, but also towards other social groups, particularly marginalized, stigmatized, and subcultural ones. In that respect, the religiosity level and indoctrination with religious knowledge and beliefs may also have its practical implications at the behavioral level of an individual and groups. It should be taken into account that the motivational orientation of an individual’s religiosity, depending on whether it is of a predominantly internal or external character, may be of great relevance for the formation of religious values and the promotion of attitudes among children, which at an individual’s later age may lead to the promotion of tolerance, altruism and compassion (if the intrinsic component of religiosity is the dominant one), or to the formation of prejudice, conservatism and instrumentalization or abuse (if the extrinsic component of religiosity is the dominant one).

In our research, we have found out that the components of intrinsic religiosity dominate in our respondents’ religious orientation, while the manifest, behavioral characteristics of religiosity are slightly less present both in terms of knowing and observing religious rules and rites inside the church service and community, and in terms of knowing and observing religious rules and rites by believers in practice. It is particularly pronounced regarding the attitudes about women’s right to abortion, where there is a discrepancy of the components of the attitudes: although the respondents consider themselves highly religious and educated in religious terms, as well as familiar with abortion being condemned in Orthodox Christianity, they still to the largest extent advocate keeping the women’s constitutional right to decide on their own about this issue. The negative association of religiosity was obtained regarding the attitude towards the legalization of same-sex marriages, while a positive association was observed between religiosity and the legalization of prostitution. Cannabis legalization is not entirely an Orthodox moral dilemma, although the use of opiates (even for medical purposes) and addiction diseases pose an increasing challenge both to believers and to church officials. That is why the absence of correlation between the attitude towards this social issue and religiosity is not surprising. The attitudes of female students of teacher education faculties towards euthanasia are in the function of their age and can be interpreted by the impact of their attendance of Religious Instruction. In fact, the older respondents, unlike the younger ones, had no opportunity to attend catechism classes regularly, which may have led to their more permissive attitude regarding an individual’s right to decide about the time and manner of their own death.

Our research was dedicated to the exploration of religiosity of Orthodox Christian female students at teacher education faculties in Serbia and the possibility of predicting the attitudes towards some dogmatic issues on the basis of these students’ level of religiosity, their previous religious education, and some socio-demographic variables. Having in mind the trend of returning to religion and strengthening the religious identity taking place in all ex–Yugoslav countries, together with the connection of the religious identity with the national identity and vice versa, we may conclude that Orthodox Christian believers in Serbia have returned to their religion rather than to the church, whereas this finding reached among the student population is not line with the results of the general population studies conducted in the last decade of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, which can be explained by the more than two decades-long impact of Religious Instruction on our respondents. The components of intrinsic religiosity dominate in our respondents’ religious orientation, while the manifest, behavioral characteristics of religiosity are slightly less present both in terms of knowing and observing religious rules and rites inside the church service and community, and in terms of knowing and observing religious rules and rites by believers in practice. It is particularly pronounced regarding the attitudes towards abortion, where there is a discrepancy in the components of the attitudes: although the respondents consider themselves highly religious and educated in religious terms, as well as familiar with abortion being condemned in Orthodox Christianity, they still advocate its legalization to the largest extent. The negative association of religiosity was obtained regarding the attitude towards the legalization of same-sex marriages, while a positive association was observed between religiosity and the legalization of prostitution. Cannabis legalization is not entirely a religious issue, although the use of opiates (even for medical purposes) and addiction diseases pose an increasing challenge both to believers and to church officials, so that the absence of correlation between the attitude towards this social issue and religiosity is not surprising. Euthanasia and the individual’s right to decide about the time and manner of own death is perhaps a burning gestion of Orthodox Christian believers at the moment, since it concerns the matter of redemption and that, given the results, we may say that the fight against infanticide has been lost, there is still the ongoing fight for the hope in resurrection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.P. and U.V.Š.; methodology, J.R.P.; software, J.R.P.; validation, U.V.Š., J.R.P. and I.A.N.; formal analysis, J.R.P.; investigation, I.A.N.; resources, I.A.N.; data curation, I.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.P. and U.V.Š.; writing—review and editing, J.R.P., U.V.Š. and I.A.N.; visualization, J.R.P.; supervision, U.V.Š.; project administration, I.A.N.; funding acquisition, U.V.Š. and I.A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The writing of this text was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation according to the agreement on the transfer of funds for scientific and research work of the teaching staff at accredited higher education institutions in 2024 (Record number: 451-03-65/2024-03/200138).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the survey conducted in the study was voluntary and anonymous, the participants could not be identified when completing the online questionnaire.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available because it was collected solely for the purpose of scientific research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | Together with some other identity features, such as the Serbian language and the Cyrillic script, the Kosovo myth, national unity and solidarity, libertarianism and anti-fascism as identity values. For more information, read about the SOC monasteries in Kosovo and Metohija as identity transmission bearers (Popić 2021, p. 124; Vučković 2022). |

| 2 | That process is not irreversible since conversion takes place even today, although on a much smaller scale than in the past. |

| 3 | The only alternative for this subject is Civic Education, and the student must choose one of the two subjects; our study shows that about 2/3 students opt for Religious Instruction (Šuvaković et al. 2023b, p. 5). |

| 4 | Such as attitudes towards contagious diseases, mental illness causes and treatment, cloning, euthanasia, using contraceptives, abortion, prohibited blood transfusion etc. |

| 5 | e.g., attitudes toward artificial intelligence, use of information-communication technologies for religious perposies etc. |

| 6 | We distinguish determinations from attitudes. Determinations refer to a relatively steady set of predominantly agreed value viewpoints, value and practical orientations and behaviors, while specific attitudes are, as a rule, in line with determinations, but may also be an exemption from them, whereas attitudes are more easily and, accordingly, more commonly changeable (see Šuvaković 2000, pp. 58–59). |

| 7 | In total 35 countries, including Greece in 2024. as the first and so far the only Orthodox Christian country to allow it (Rozzelle et al. 2024). |

| 8 | The researchers pointed to the problem of the under-registration of the number of abortions shown by statistics. By applying Charles Westoff’s model researchers pointing out that the rate of the total induced abortions in Serbia in 2019—before the COVID-19 pandemic—was 2.8. “It means that during her reproductive cycle, a woman has on average about three elective abortions” (Rašević and Sedlecki 2021, p. 44). |

| 9 | According to the 2018 research, the male or female student had the first sexual intercourse: at the age of 11 or earlier—11.9%, at the age of 12—3.0%, at the age of 13—5.2%, at the age of 14—19.3%, at the age of 15—47.2%, and at the age of 16 and later—13.3%. However, only four years later, the trend of the decreasing the age limit for the first sexual intercourse was recorded: at the age of 11 or earlier—22.6%, which shows an almost double share of the youngest ones as compared to 2018; at the age of 12—3.0%, at the age of 13—4.7%, at the age of 14—14.5%, at the age of 15—41.3%, and at the age of 16 or later—14.0% (Batut 2023b). |

| 10 | According to the SOC canons, a woman who undergoes abortion of her own free will is subject to a church punishment in the form of “suspension from communion for a longer period oof time: for life, for ten or minimum seven years” (Jocić and Krstić 2015, p. 155). Moreover, according to the SOC canons, if a woman undergoes abortion against her husband’s will or without his knowledge, he is entitled to initiate divorce proceedings in case the marriage was concluded in the SOC: “Marriage shall be divorced through the fault of a woman who intentionally aborts her foetus or intentionally and permanently prevents her fertilization. Abortion shall not be deemed intentional when it is performed in line with the decision of a panel of doctors for the purpose of preserving mother’s life” (Marriage Rules 1994). |

References

- Anić, Rebeka Jadranka. 2008. Spolne razlike u religioznosti pod vidom obrazovanja [Gender differences in religiousness from the perspective of education]. Bogoslovska Smotra 4: 873–903. [Google Scholar]

- Antonić, Slobodan. 2021. One Theoretical Framework for Understanding Current LGBT Issues in Serbia Today. Sociološki Pregled 3: 671–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, Stephen J., Suzanne L. Maughan, Anastasios C. Marcos, and Bingdao Li. 1998. Family, religiosity, and the risk of adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and the Family 4: 979–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakrač, Vladimir. 2016. Religiosity and gender differences in the example of the young. Facta Univesitatis Series: Philosophy, Sociology, Psychology and History 2: 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Batut. 2020. Evropsko školsko istraživanje o upotrebi psihoaktivnih supstanci među učenicima u Srbiji [ESPAD—The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs]. Belgrade: Institute for Public Health “Milan Jovanović Batut”. Available online: https://www.batut.org.rs/download/izdvajamo/EvropskoSkolskoIstrazianje2019.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Batut. 2023a. Health Statistical Yearbook of Republic of Serbia 2022. Belgrade: Institute for Public Health “Milan Jovanović Batut”. Available online: https://www.batut.org.rs/download/publikacije/pub2022v1.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Batut. 2023b. Istraživanje u vezi sa zdravljem dece školskog uzrastau Republici Srbiji 2022. godine: Rezultati o seksualnom ponašanju [Health behaviour in School–aged Children Survey, HBCS: Results on sexual behavior, Serbia 2022]. Belgrade: Institute for Public Health “Milan Jovanović Batut”. Available online: https://www.batut.org.rs/download/aktuelno/Seksualno%20ponasanje%20hbsc%202023.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Bazić, Jovan. 2011. Nacionalni identitet u procesu političke socijalizacije [National Identity in the Process of Political Socialization]. Srpska politička misao 34: 335–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begović, Nedim. 2020. Restrictions on Religions due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Responses of Religious Communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Journal of Law, Religion and State 2–3: 228–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen Sinding, Jeanet. 2021. In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 192: 541–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelić, Lucija, and Ivanka Macuka. 2018. Smisao života: Uloga religioznosti i stavova prema smrti [Meaning of life: The role of religion and attitudes towards death]. Psihologijske Teme 2: 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, Rajshekhar, Areej R. El-Jawahri, Mark R. Litzow, Karen L. Syrjala, Aric D. Parnes, and Shahrukh K. Hashmi. 2017. A systematic review of religious beliefs about major end-of-life issues in the five major world religions. Palliative and Supportive Care 5: 609–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čović, Ana. 2021. The Influence of Judicial Practice on the Legislation in The Sphere of LGBT Community Rights. Sociološki Pregled 3: 690–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dušanić, Srđan. 2007. Psihološka istraživanja religioznosti [Psychological Research of Religiosity]. Banja Luka: Filozofski fakultet. [Google Scholar]

- Đorđević, Dragoljub B. 1984. Beg od crkve. [Running Away from the Church]. Knjaževac: Nota. [Google Scholar]

- Đorđević, Dragoljub B. 1999. Religija i nauka: Religijsko obrazovanje u školi. [Religion and Science: Religious Instruction at School]. In Mladi, religija, veronauka [Young People, Religion, Religious Education]. Edited by Dragoljub B. Đorđević and Todorović Dragan. Niš: KSS, pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Đorđević, Dragoljub B. 2009. Religiosness of Serbs at the Beginning of the 21st Century: What Is It About? In Revitalization of Religion—Theoretical and Comparative Approaches. Edited by Danijela Gavrilović. Niš: YSSSR, pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Engs, Ruth Clifford, and Kenneth Mullen. 1999. The effect of religion and religiosity on drug use among a selected sample of post-secondary students in Scotland. Addiction Research 7: 149–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gajić, Vladimir. 2012. Eutanazija kroz istoriju i religiju [Euthanasia through history and religion]. Medicinski Pregled 3–4: 173–77. Available online: https://scindeks-clanci.ceon.rs/data/pdf/0025-8105/2012/0025-81051204173G.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Glock, Charlie S., and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. Chicago: Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Gojković, Vesna, Marija Plahuta, and Jelena Dostanić. 2019. Narcizam SD3 i narcizam modela NARC: Sličnosti i razlike [The SD3 measure of narcissism and the narcissism of the NARC model: Differences and similarities]. Zbornik Instituta za Kriminološka i Sociološka Istraživanja 3: 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch, Richard L. 1978. Psychology of religion. Annual Review of Psychology 1: 201–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, Graham, Melanie Lovell, and Megan Best. 2022. Perspectives of Major World Religions regarding Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide: A Comparative Analysis. Journal of Religion and Health 6: 4758–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jocić, Gordana, and Zoran Krstić. 2015. Stavovi Crkve o čedomorstvu (abortusu) u medijima. [The Attitudes of the Church to Infanticide (Abortion) in the Media]. In Srpska pravoslavna crkva u štampanim medijima 2003–13 NIN-Vreme bibliografija tom III [Serbian Ortodox Church in print media 2003–13 NIN—Vreme bibliography Volume III]. Edited by Vukašinović Vladimir. Beograd: Institut za kulturu sakralnog MONS HEMUS, pp. 155–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kampadžija, Alekandra, Jelka Vukelić, Artur Bjelica, and Vesna Kopitović. 2010. Abortus lekovima—Savremena metoda prekida trudnoće [Medical abortion—Modern method for termination of pregnancy]. Medcinski Pregled 1–2: 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharari, Khali Akhtar, and Teresa McRay Harmon. 1982. The relationship between the degree of professed religious belief and use of drugs. International Journal of the Addictions 5: 847–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodish, Eric. 2008. Paediatric ethics: A repudiation of the Groningen protocol. Lancet 371: 892–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krstić, Zoran. 2012. Veronauka u službi vaspitanja za vrdnosti. [Religious Instruction in the Service of Upbringing for Values]. Kragujevac: Eparhija Šumadijska. VERONAUKA U SLUŽBI VASPITANJA ZA VREDNOSTI—Eparhija Šumadijska. Available online: https://eparhija-sumadijska.org.rs/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Krstić, Zoran. n.d. Eutanazija kao društveno, bioetičko i hrišćansko pitanje [Euthanasia as a Social, Bioethical and Christian Matter]. Kragujevac: Eparhija Šumadijska, EUTHANASIA KAO DRUŠTVENO, BIOETIČKO I HRIŠĆANSKO PITANJE—Eparhija Šumadijska. Available online: https://eparhija-sumadijska.org.rs/ (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Ljubotina, Damir. 2004. Razvoj novog instrumenta za mjerenje religioznosti [Development of the new instrument for religiosity measurement]. In Dani psihologije u Zadru [Days of psychology in Zadar]. Edited by Vera Ćubela Adorić, Ilija Manenica and Zvjezdan Penezić. Zadar: Sveučilište u Zadru, pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mandić Gajić, Gordana. 2008. Psihoaktivne supstancije i mladi—Da li smo svesni stvarne opasnosti? [Psychoactive substances and youth—Are we aware of real risk?]. Vojnosanitetski Pregled 6: 421–23. [Google Scholar]

- Marić, Jovan. 2001. Medicinska etika [Medical Ethics]. 11 prerađeno i dopunjeno izdanje [11th Revised and Supplemented Edition]. Beograd: Megraf. [Google Scholar]

- Marinović Jerolimov, Dinka. 2002. Religioznost, nereligioznost i neke vrijednosti mladih [Religiosity, Non-religiosity and Some Values of Youth]. In Mladi uoči trećeg milenija [Youth and Transition in Croatia]. Edited by Vlasta Ilišin and Furio Radin. Zagreb: Institut za društvena istraživanja u Zagrebu i Državni zavod za zaštitu obitelji, materinstva i mladeži, pp. 79–124. [Google Scholar]

- Marriage Rules. 1994. Bračna pravila Srpske pravoslavne crkve: II dopunjeno i ispravljeno izdanje Svetog arhijerejskog sinoda [Marriage Rules of the Serbian Orthodox Church, 2nd supplemented and modified edition of the Holy Synod of Bishops]. Beograd. Available online: https://www.pravoslavnikalendar.rs/latin/load/obicaji/brak.html (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Matejević, Marina, and Svetlana Stojanović. 2020. Vaspitni stil roditelja i religioznost studenata [Parenting style and students’ religiosity]. Godšnjak za Pedagogiju 1: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materstvedt, Lars Johan, David Clark, John Ellershaw, Reidun Førde, Anne-Marie Boeck Gravgaard, H. Christof Müller-Busch, Josep Porta y Sales, Charles-Henri Rapin, and EAPC Ethics Task Force. 2003. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: A view from an EAPC Ethics Task Force. Palliative Medicine 2: 97–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milić, Časlav T. 2000. Karakteristike upotrebe i zloupotrebe psihoaktivnih supstancija [Characteristics of the use and abuse of psychoactive substances]. Vojnosanitetski Pregled 1: 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Milić, Časlav T., Branivoje Timotić, Isidor Jevtović, and Sanja Ristović. 1997. Bolesti zavisnosti među učenicima osnovnih i srednjih škola grada Kragujevca. [Addiction diseases among primary and secondary school students in the City of Kragujevac]. In Zdravstvena zaštita studentske i srednjoškolske omladine u savremenim uslovima života [Health Care of Students and High School Youth in Modern Living Conditions]. Edited by Dragan Ilić. Zlatibor: Zavod za zdravstvenu zaštitu studenata Beograd, p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Mladenović, Uroš V., and Jasna Knebl. 1999. Religioznost, aspekti self-koncepta i anksioznost adolescenata. [Religiosity, aspects of the self-concept and adolescents’ anxiety]. Psihologija 1–2: 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Charlie, Scott Sam, and Geddes Alastair. 2019. Snowball Sampling. In Research Methods Foundation. Edited by Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug and Richard A. Williams. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publication Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Pavićević, Vuko. 1988. Sociologija religije sa elementima filozofije religije [Sociology of Religion with Elements of Philosophy of Religion], 3rd ed. Beograd: BIGZ. [Google Scholar]

- Pirutinsky, Steven, Aaron D. Cherniak, and David H. Rosmarin. 2020. COVID-19, Mental Health, and Religious Coping Among American Orthodox Jews. Journal of Religion and Health 5: 2288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popić, Snežana S. 2021. (De)konstrukcija kolektivnog identiteta na Kosovu i Methiji [(De)construction of the Collective Identity in Kosovo and Metohija]. Ph.D. dissertation, Filozofski fakultet Univerziteta u Nišu, Niš, Serbia. Available online: https://nardus.mpn.gov.rs/handle/123456789/21879 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Radović, Snežana, T. Milić Časlav, and Sanja Kocić. 2010. Opšte karakteristike upotrebe i zloupotrebe psi-hoaktivnih supstancija kod srednjoškolaca. [General characteristics of psychoactive substances consumption and abuse among high school population]. Medicinski Pregled 9–10: 616–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulović, Dragan. 2008. Pristup proučavanju društvene kontrole droga, I—Konstrukcija problema. [Approaching the social control of drugs, I: Construction of the problem]. Sociologija 2: 113–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašević, Mirjana, and Katarina Sedlecki. 2011. Pitanje postojanja abortusne kulture u Srbiji [View of the abortion culture issue in Serbia]. Stanovništvo 1: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašević, Mirjana, and Katarina Sedlecki. 2021. Srbija u suočavanju sa pandemijom COVID-19: Izazovi seksualnom i reproduktivnom zdravlju [Serbia in The Face of Pandemic COVID-19: Challenges in Sexual and Reproductive Health]. In Humana reprodukcija u vrtlogu pandemije COVID-19 [Human Reproduction in the Vortex of the Pandemic of COVID-19]. Edited by Nebojša Radulović. Beograd: Samizdat, pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Republički statistički zavod—RZS. 2021. Visoko obrazovanje 2020/2021. [Higher Education 2020/2021]; Belgrade: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2021/pdf/G20216006.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Republički statistički zavod—RZS. 2022. CENSUS 2022—EXCEL TABLE: Population by Religion, by Municipalities and Cities. Available online: https://popis2022.stat.gov.rs/en-US/popisni-podaci-eksel-tabele (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Risimović, Radoslav. 2018. Da li je opravdana legalizacija medicinske i rekreativne upotrebe kanabisa? [Is the legalization of medical and recreational use of cannabis justified?]. Nauka, Beybednost Policija -NBP 3: 251–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzelle, Josephine, Brianna Navarre, and Megan Trimble. 2024. Same-Sex Marriage Legalization by Country. U.S. News, 15th February. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/countries-where-same-sex-marriage-is-legal (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Sharp, Shane. 2018. Beliefs in and About God and Attitudes Toward Voluntary Euthanasia. Journal of Religion and Health 3: 1020–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sretenović, Ivana. 2013. Večita tema i dilema—Abortus [Eternal topic and dilemma—Abortion]. Zdravstvena Zaštita 6: 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šušnjić, Đuro. 1998. Religija: Concept, struktura, funkcije, I [Religion: Concept, Structure, Function, vol. 1]. Beograd: Čigoja štampa. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvaković, Uroš. 2000. Ispitivanje političkih stavova [Examination of Political Attitudes]. Beograd: Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvaković, Uroš. 2014. Tranzicija: Prilog sociološkom proučavanju društvenih promena [Transition: Contribution to Sociological Study of Social Changes]. Kosovska Mitrovica: Filozofski fakultet Univerziteta u Prištini. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvaković, Uroš. 2021. A Contribution to the Debate about Social Recognition of Marriage-like and Family-like Social Phenomena. Sociološki Pregled 3: 714–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuvaković, Uroš V., Ivko A. Nikolić, and Jelena R. Petrović. 2023a. Verska nastava u Srbiji dve decenije posle uvođenja u školski sistem: Mišljenja studenata i njihovi stavovi po srodnim pitanjima [Religious education in Serbia two decades after its introduction in the school system: Opinions of students and their attitudes on related issues]. Nacionalni Interes 3: 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuvaković, Uroš V., Jelena R. Petrović, and Ivko A. Nikolić. 2023b. Confessional Instruction or Religious Education: Attitudes of Female Students at the Teacher Education Faculties in Serbia. Religions 14: 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takšić, Iva, and Barbara Kalebić Maglica. 2023. Provjera faktorske strukture Upitnika moralnih temelja na uzorku hrvatskih studenata [Validation of the Factor Structure of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire on the Croatian Students Sample]. Psihologijske Teme 3: 615–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tešanović, Jelena. 2012. Socio-psihološki korelati posjećivanja crkve kod adolescenata. [Socio-psychological correlates of church attendance among adolescents]. In II kongres psihologa Bosne i Hercegovine sa međunarodnim učešćem—Zbornik radova. Edited by Jadranka Kolenović-Đapo, Fako Indira, Maida Koso-Drljević and Mirković Biljana. Banja Luka: Društvo psihologa Republike Srpske, pp. 221–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiljević Prodanović, Danica, and Maja Denčić. 2021. Društvena reakcija na upotrebu kanabisa. [Social reaction to cannabis use]. Bezbednost 3: 113–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbakel, Ellen, and Eva Jaspers. 2010. A comparative study on permissiveness toward euthanasia: Religiosity, slippery slope, autonomy, and death with dignity. The Public Opinion Quarterly 1: 109–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučković, Branislava B. 2022. Changing the Carriers of Cultural Memory Through the Prism of Debray’s Mediological Theory. Sociološki Pregled 1: 141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, Ana. 2021. Circulus Vitiosus of the Sex/Gender Dichotomy: Feminist Polemics with Trans Activism. Sociološki Pregled 3: 650–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Julie K., Douglas C. Smith, Nathan Gotman, Bushra Sabri, An Hyonggin, and James A. Hall. 2008. Traumatized youth and substance abuse treatment outcomes: A longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1: 100–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]