Biblical Hermeneutics without Interpretation? After Affect, beyond Representation, and Other Minor Apocalypses

Abstract

Expository interjection: “Affect studies”, the editors of The Affect Theory Reader 2 (Seigworth and Pedwell 2023, p. 4) teasingly remark, “continues to evolve and mutate as a rangy and writhing poly-jumble of a creature (with far more than eight tentacles)”. Nevertheless, affect as ordinarily understood in affect theory is emotion, feeling, and/or an infinitely open-ended list of harder-to-name ephemera, insignificant and consequential by turns: diffuse sensations, reflexive reactions, vague apprehensions, shocking encounters, deadening atmospheres, and the like. “Language, representation, and consciousness are … always fringed with and permeated by affective forces”, Seigworth and Pedwell observe (p. 19). Assemblage theory merits its own exposition, and will receive it in due course.

1. The Geography of Non-Representational Theory

Self-deprecatory interjection: Enough of silly apocalypticism. This is already turning out to be yet another end-of-the-scholarly-world-as-we-know-it melodrama. I have crafted more than my share of them over the decades, God knows, beginning when poststructuralism loomed eschatologically on my own hermeneutical horizon. But I do like a good story.

2. The Death of the Interpreter

Confessional interjection: More on that myriad in a moment. First, let me confess, in reflexive reaction to Nealon’s implicit summons, that I personally feel no desire whatsoever to set foot on the first yellow brick of the post-interpretive road, to shrug my own interpretation compulsion aside, to be cured of my chronic interpretosis. In my writing, even in my teaching, interpretation is still what matters most to me. While recognizing that the concept of meaning brims over with post-poststructuralist problems, I still find interpretation to be the most meaning-full aspect of my peculiar existence as a biblical studies professional.

3. The Erosion of Representation

Strange contraptions, you will tell me, these machines of virtuality, these blocks of mutant percepts and affects,14 half-object and half-subject …. They have neither inside nor outside. They are limitless interfaces which secrete interiority and exteriority …. They are becomings …. One gets to know them not through representation but through affective contamination. They start to exist in you, in spite of you. And not only as crude, undifferentiated affects, but as hyper-complex compositions …. But whatever their sophistication, a block of percept and affect …agglomerates in the same transversal flash the subject and object, the self and other, the material and incorporeal …. In short, affect is not a question of representation … but of existence.

4. The Representation Compulsion and the Biblical Scholar

Concessive interjection: Granted, the notion of “lost originals” (of the canonical gospels, say) has fallen on hard times in certain scholarly circles in recent decades.16 Most biblical scholars are also well aware that authorial intentionalism has been stabbed through the heart repeatedly in literary studies since the mid-twentieth century.17 And some of us even take pains to adjust our language accordingly. But the ground rules of the disciplinary discourse in which we are enmeshed were put in place long before the author began to bleed, powerfully predisposing us to speak and write as though we still believed fervently in original, finalized gospel autographs brimming over with ultimately retrievable (even if squirmy and slippery) authorial intentions.18 It is our default modus operandi as biblical scholars, the bedrock of our disciplinary practice, and it would take a seismic shock to dislodge it, disturbances like biblical-critical postmodernism or contextual biblical hermeneutics merely eroding the edges but leaving the core intact. We call it “mainstream biblical scholarship”, but, in reality, it is less a free-flowing stream than a massive instance of what Nigel Thrift would call a “frozen state” (Thrift 2008, p. 5). And it is locked in place by the representation compulsion.

Anecdotal interjection: The present author, now aged, is reminded of a conference in his youth in which, following a plenary address, and trembling a little at his own audacity, he addressed a question to an illustrious figure in the field, one that began, “In your reading of Romans just now …”. The presenter’s response to the question in turn began, “First of all, I do not ‘read’; I exegete”. What the elder me now wishes the junior me had replied: “I’m not sure either of us yet know what it means to ‘read.’ Until we do, neither can we know what it means to ‘exegete.’”

5. Biblical Scholarship Is a Mess

Free-associative interjection: What does strike me, however, is that Law’s initial reflections on how “teach[ing] ourselves to know” our messy world “using methods unusual to or unknown in social science” (Law 2004, p. 2) have affinities with how practitioners of contextual biblical hermeneutics approach their work (once they have substituted the contemporary world, or particular localized corners of it, for the ancient world as their primary world of concern). Perhaps our world needs to be known “through the hungers, tastes, discomforts, or pains of our bodies”, muses Law. “These would be forms of knowing as embodiment” (pp. 2–3). Such embodied knowing thoroughly infuses much contextual biblical scholarship, impelled as it is by intense social “hungers”, pressing social “discomforts”, and intolerable social “pains”.

When I had worked through the numerous [nineteenth-century] lives of Jesus, I found it very difficult to organize them into chapters. After vainly attempting to do this on paper, I piled all the “lives” in one big heap in the middle of my room, selected a place for each of the chapters in a corner or between the pieces of furniture, and then … sorted the volumes into the piles in which they belonged. I pledged myself … to leave each heap undisturbed in its place until the corresponding chapter in the manuscript was finished …. For many months people who visited me had to thread their way across the room along paths that ran between heaps of books.

6. What Happens When I Read My Bible (in an Assemblage)?

Illustrative interjection: I type these words—indeed, to no small degree, I think these words—in symbiotic assemblage with the machine quasi-intelligence I familiarly call “my computer”, while the other human-mimicking, human-surpassing machine I call “my phone” buzzes beguilingly in my pocket, always eager to distract me. But even the worn wooden desk on which the computer sits, and the creaky wooden chair on which I sit, are also intimately in assemblage with me, as are the layers of clothes that equally enable me to function as a “biblical professional” on this chilly winter morning.

Self-interrogatory interjection: When did I last physically enter my university’s library, that sacral scholarly space, for the purpose of literally laying hands on a print book or journal? The computer god would scoff at such a primitive notion, its innumerable, pulsing, infinitely extendable tentacles lighting up with amusement.

Too-much-informational interjection: I once attempted briefly (Moore 2014, pp. 160–62), without much success, to write about the asignifying, non-representational dimension of Bible reading on which we have just been ruminating, of my inordinate sensory attachment to my first-edition New Revised Standard Version and my far older preferred Greek New Testament (so many editions out of date), which accompany me into every classroom, both of them grubby, dog-eared, mercilessly scribbled upon, and essentially falling apart, but intimate symbiotic extensions of the yet more aged body of this “biblical professional”, their moldering pages indelibly marked by the secretions and excretions of his sebaceous and sudoriferous glands, so that he is bonded chemically no less than affectively with them. As Nigel Thrift (2010, p. 293) aptly observes, “The human contains all manner of objects within its envelope”.

7. A Bible Kept in a Box

|

8. Why My Bible Keeps Falling into the Gulf of Non-Resemblance

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | What of the cognate field(s) of theology? Petra Carlsson Redell appears to be the theologian who has engaged most extensively with the non-representational (see esp. Carlsson Redell 2014, 2018). |

| 2 | Ashley Barnwell’s (2020, p. 3) inventory of recent schools of thought that break with the classic poststructuralist preoccupations also includes affect theory, speculative realism, object-oriented ontology, new materialism, actor-network theory, and feminist science studies. |

| 3 | Simpson (2021, pp. 223–24) is disarmingly frank on his book’s belatedness: “This book is probably a decade late. Someone really should have written it before me and before now. I think it probably would have been a much easier task to complete when NRTs [Non-Representational Theories] were easier to bound and less diffuse in their influence and spread …. ‘NRT’ as a singular thing is increasingly hard to see …. This book might … end up being something more like a eulogy for something—a movement, a moment, a feeling, a confluence of energies—that has now passed”. In biblical studies, however, we have a hospitable tradition of welcoming into our midst theories that have been bled dry, even declared dead, in neighboring fields, feeding them fresh primary material, and raising them to new life. |

| 4 | I am, of course, compressing Collins’s detailed analysis of the material in what follows. |

| 5 | I had the privilege of participating in the 2016 conference at the Universität Wien that yielded the volume, Biblical Exegesis without Authorial Intention? (Breu 2019b), and the present article is a further offshoot of the thought-provoking discussions the conference stimulated. A parallel conference collection, exploring a comparable set of concerns, has since appeared: Authorship and the Hebrew Bible (Ammann et al. 2022b). But the present article is also indirectly indebted to far earlier precursors, most of all George Aichele’s poststructuralist explorations in biblical semiotics (Aichele 1997, 2001). |

| 6 | It is not that Collins is uncomfortable with the term “intention”; it recurs in her commentary. Again, let a single example suffice: “The intention of the evangelist comes out even more clearly in the editorial summary given in 1:34 …” (Collins 2007, p. 172). On the persistence of authorial intentionalism in biblical scholarship, see the representative catena of quotations in Dinkler (2019, pp. 74–75). More on this matter below. |

| 7 | Not least in the extensive corpus of work on New Testament and other early Christian bodies that has flowed forth since the mid-1990s. I have reflected elsewhere (Moore 2023, pp. 112–22) on the paradoxical eclipse of the ancient body in such work. |

| 8 | Thrift, not coincidentally, has an essay in The Affect Theory Reader, one that begins on a somewhat jaded note: “The affective moment has passed in that it is no longer enough to observe that affect is important: in that sense at least we are in the moment after the affective moment” (Thrift 2010, p. 289). |

| 9 | Cf. Lorimer (2005, pp. 84–85): “The now well-established critique of ‘representationalism’ … is that it framed, fixed, and rendered inert all that ought to be most lively”. |

| 10 | And the relationship of this project to affect? Deleuze expresses it as follows: “Every mode of thought insofar as it is non-representational will be termed affect” (Deleuze 1978–1981, n.p.). |

| 11 | A single illustrative example from a vast pool of potential examples: W. Randolph Tate (2013), whose standard hermeneutical handbook, Biblical Interpretation: An Integrated Approach, has as its three constitutive parts “The World Behind the Text”, “The World Within the Text”, and “The World in Front of the Text”, understands the relationship between author and text to be one of representation. With considerable nuance, he expresses that understanding as follows: “Textual meaning is the cultural specificity of the author’s original object of consciousness. There is no way to determine definitively just how accurately the text represents the object of intention” (Tate 2013, p. 13, emphasis added). |

| 12 | Clarissa Breu remarks that “biblical studies could make use of much more differentiated views on the author than are predominantly presumed within the discipline. Particularly, exegetical commentaries tend to reconstruct details about the historical person behind the text and hardly ever debate the category of ‘author’ and its role in the process of interpretation” (Breu 2019a, p. 2) |

| 13 | In Deleuzoguattarian parlance, the virtual has (as yet) nothing to do with the digital. Rather, the virtual is the actual’s condition of emergence and vice versa. The actual unfolds continuously from the virtual, but every actualization is itself replete with further virtualities (see esp. Deleuze and Parnet 2007, pp. 148–52, together with Aichele 2011, pp. 1–46). Biblical texts are virtual in this sense (as are all works of literature), in that they are actualized by readers and hearers in interminable variations, each actualization virtually enabling still further actualizations in an exponential spiral (not least, but also not only, when the actualization is academic: a conference paper, an article, a book). Significantly, Brian Massumi, in a retrospective reflection on his 2002 book, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, commonly viewed as a coalescing catalyst for affect theory in the Deleuzian mode, remarks: “While writing the book, I felt affect to be absolutely crucial, but … if pressed to say in one word what the book was about, I would have said ‘the virtual’” (Massumi [2002] 2021, p. xiii). |

| 14 | For Deleuze and Guattari, sensation is “a compound of percepts and affects” (Deleuze and Guattari 1994, p. 164). Percepts are not perceptions: prepersonal, impersonal, they do not entail a distinction between perceiver and perceived, subject and world. “We are not in the world, we become with the world” (p. 169), and the percept is “a perception in becoming” (Deleuze 1997, p. 88). As such, it (logically) precedes perception, just as affect precedes emotion. |

| 15 | A simplifying summation of a more complex process, I realize. I turn to the intricacies of the process below. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Since 1946, it is usually said, the year “The Intentional Fallacy” appeared; but that article begins in media res, Wimsatt and Beardsley (1946) noting that interrogation of authorial intentionalism is already underway (p. 468). |

| 18 | Even in Hebrew Bible/Old Testament studies, the author is far from dead and buried. On the one hand, as Sonja Ammann notes, introducing the collection Authorship and the Hebrew Bible, it is “broadly acknowledged” that the texts that comprise the Hebrew Bible were not the work of single authors “or handed down unchanged” (Ammann 2022, p. 2). The complex literary process that birthed the Pentateuch, for instance, thoroughly upends such notions. Similarly, the hypothesis, classically propounded by Martin Noth, that “an individual author determined the shape of [the Deuteronomistic History] has been abandoned in recent models” (p. 2). In research on the prophets, likewise, scholars have relinquished earlier ideas revolving around “the creative genius” of individual authors (p. 2). On the other hand, however, “many scholars still use the term ‘author’ without further clarification” in exegetical practice, while “others replace the term ‘author’ by concepts with little meaningful distinction from how authorial intentions and motivations were conceptualized in earlier scholarship” (p. 4). In their preface to Authorship and the Hebrew Bible, the editors observe, relatedly, that recent scholarship is characterized by “an increased appreciation of the creativity of redactors, editors, scribes etc.”, and this creativity tends to be treated essentially as authorial intentionality. “Hence, scholars working from historical perspectives, even though they may reject the idea of a creative single individual who holds absolute power and ownership over his text(s), do adhere to (implicit) concepts of authorship, which are rarely discussed or subjected to theoretical evaluation” (Ammann et al. 2022a, pp. v–vi). If anything, this bifurcation is even more pronounced in New Testament studies, a work like Luke-Acts, say, or the Letter to the Galatians, or the book of Revelation (and too many others to name) appearing to invite laser-focused engagement with an individual author to an extent that few works of the Hebrew Bible do. |

| 19 | Law is best known as one of the progenitors of actor-network theory (see esp. Law 1992; Law and Hassard 1999), a field that intersects substantially with both non-representational theory and assemblage theory. |

| 20 | Further on assemblage theory, see esp. DeLanda (2016) and Buchanan (2021); and for biblical applications, see Graybill (2016, pp. 37–39, 121–42); Moore (2017, pp. 41–59; 2023); Jeong (2020); Rawson (2020); McLean (2022, pp. 77–97); and E. C. Smith (2022). |

| 21 | Deleuze and Guattari continue: “Hans is also taken up in an assemblage: his mother’s bed, the paternal element, the house, the café across the street, the nearby warehouse, … the right to go out onto the street …. Is there an as yet unknown assemblage that would be neither Han’s nor the horse’s, but that of the becoming-horse of Hans?” (Deleuze and Guattari [1980] 1987, pp. 257–58). |

| 22 | In effect, because the term “assemblage” makes few explicit appearances in Snaza’s “What Happens When I Read?” But he has earlier signaled (Snaza 2019, p. 166 n. 2) that the Deleuzoguattarian concept of assemblage undergirds his reflections throughout his book on what he terms “the literacy event”. |

| 23 | Ramón Grosfoguel (2007, p. 214) notes, relatedly, how the five-hundred-year progression of overt colonization into covert coloniality extends from sixteenth century Europe and its dehumanizing characterization of the colonized as “people without writing”, to the eighteenth and nineteenth century characterization of them as “people without history”, to the twentieth century Euro-American characterization of their descendants as “people without development”, to the early twenty-first century characterization of them as “people without democracy”. |

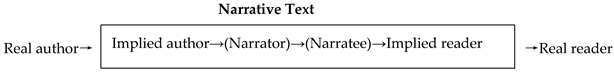

| 24 | The most notable early appearance in New Testament narrative criticism of Chatman’s diagram of narrative communication is in R. Alan Culpepper’s highly influential Anatomy of the Fourth Gospel (Culpepper 1983, p. 6), Culpepper adding further details to Chatman’s model. The diagram shows up in unadulterated form in Elizabeth Struthers Malbon’s widely read “Narrative Criticism: How Does the Story Mean?” (Malbon [1992] 2008, p. 33), and in various other books and articles. For a recent reappearance of the diagram, see James L. Resseguie’s “A Glossary of New Testament Narrative Criticism with Illustrations” (Resseguie 2019, p. 24). Tellingly, Chatman features more prominently in Resseguie’s comprehensive article than any other narrative theorist. |

| 25 | In other words, the “three worlds” model I earlier identified as commonplace in mainstream biblical hermeneutics (the world “behind” the text, the world “within” the text, and the world “in front of” the text) is also implicit in Chatman’s narrative communication model. |

| 26 | Womanist New Testament scholar M. J. Smith (2022, p. 55) responds to the panel as follows: “Mainstream dominant white biblical scholars ask, ‘how do you know when you have crossed the line, gone too far?’ It is the Black interpreter, the interpreter of color, or the woman to whom this question is put. And with that question, we are rendered fungible and Black(ened) because we overtly contextualize our readings, which are replaceable with other darkened bodies and readings that do not transgress the boundaries of whiteness”. |

References

- Ahern, Stephen. 2019a. Introduction: A Feel for the Text. In Affect Theory and Literary Critical Practice: A Feel for the Text. Palgrave Studies in Affect Theory and Literary Criticism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern, Stephen, ed. 2019b. Affect Theory and Literary Critical Practice: A Feel for the Text. Palgrave Studies in Affect Theory and Literary Criticism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aichele, George. 1997. Sign, Text, Scripture: Semiotics and the Bible. Interventions, 1. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aichele, George. 2001. The Control of Biblical Meaning: Canon as Semiotic Mechanism. Harrisburg: Trinity Press International. [Google Scholar]

- Aichele, George. 2011. Simulating Jesus: Reality Effects in the Gospels. BibleWorld. London: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Ammann, Sonja. 2022. What Follows the Death of the Author? Introduction. In Authorship and the Hebrew Bible. Forschungen zum Alten Testament. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ammann, Sonja, Katharina Pyschny, and Julia Rhyder. 2022a. Preface. In Authorship and the Hebrew Bible. Forschungen zum Alten Testament. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. v–vi. [Google Scholar]

- Ammann, Sonja, Katharina Pyschny, and Julia Rhyder, eds. 2022b. Authorship and the Hebrew Bible. Forschungen zum Alten Testament. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Ben. 2014. Encountering Affect: Capacities, Apparatuses, Conditions. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Ben, and Paul Harrison. 2010a. The Promise of Non-Representational Theories. In Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories and Geography. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Ben, and Paul Harrison, eds. 2010b. Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories and Geography. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Barnwell, Ashley. 2020. Critical Affect: The Politics of Method. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1977. The Death of the Author. In His Image, Music, Text. Translated by Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, pp. 142–48. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Fiona C., and Jennifer L. Koosed, eds. 2019. Reading with Feeling: Affect Theory and the Bible. Semeia Studies, 95. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blount, Brian K., Cain Hope Felder, Clarice J. Martin, and Emerson B. Powery, eds. 2007. True to Our Native Land: An African American New Testament Commentary. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breu, Clarissa. 2019a. Introduction: Authors Dead and Resurrected. In Biblical Exegesis without Authorial Intention? Interdisciplinary Approaches to Authorship and Meaning. Biblical Interpretation, 172. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Breu, Clarissa, ed. 2019b. Biblical Exegesis without Authorial Intention? Interdisciplinary Approaches to Authorship and Meaning. Biblical Interpretation, 172. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, Ian. 2021. Assemblage Theory and Method: An Introduction and Guide. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Bultmann, Rudolf. 1960. Is Exegesis without Presuppositions Possible? In Existence and Faith: Shorter Writings of Rudolf Bultmann. Edited and Translated by Schubert M. Ogden. New York: Living Age Books, pp. 289–96. First published 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson Redell, Petra. 2014. Mysticism as Revolt: Foucault, Deleuze, and Theology Beyond Representation. Aurora: The Davies Group. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson Redell, Petra. 2018. Foucault, Art, and Radical Theology: The Mystery of Things. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, Seymour. 1978. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, Seymour. 1990. Coming to Terms: The Rhetoric of Narrative in Fiction and Film. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Adela Yarbro. 2007. Mark: A Commentary. Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Culpepper, R. Alan. 1983. Anatomy of the Fourth Gospel: A Study in Literary Design. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeLanda, Manuel. 2016. Assemblage Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1978–1981. Lecture Transcripts on Spinoza’s Concept of Affect. Translated by Émilie Deleuze, and Julien Deleuze. Available online: https://www.gold.ac.uk/media/images-by-section/departments/research-centres-and-units/research-centres/centre-for-invention-and-social-process/deleuze_spinoza_affect.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1988. Spinoza: Practical Philosophy. Translated by Robert Hurley. San Francisco: City Lights Books. First published 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1990. The Logic of Sense. Translated by Mark Lester, and Charles Stivale. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1992. Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza. Translated by Martin Joughin. New York: Zone Books. First published 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1994. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press. First published 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1995. Negotiations, 1972–1990. Translated by Martin Joughin. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1997. Essays Critical and Clinical. Translated by Daniel W. Smith. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 2000. Proust and Signs: The Complete Text. Translated by Richard Howard. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. First published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 2006. Two Regimes of Madness: Texts and Interviews 1975–1995. Edited by David Lapoujade. Translated by Ames Hodges, and Mike Taormina. New York: Semiotext(e). [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Claire Parnet. 1996. Transcript of L’Abécédaire de Gilles Deleuze, avec Claire Parnet. Directed by Pierre-André Boutang. Edited and Translated by Charles J. Stivale. Available online: https://deleuze.cla.purdue.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/lectures/en/ABCMsRevised-NotesComplete051120_1.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Claire Parnet. 2007. Dialogues II. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson, Barbara Habberjam, Eliot Ross Albert, and Joseph Hughes. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1977. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane. New York: Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1986. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. Translated by Dana Polan. Theory and History of Literature, 30. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1994. What Is Philosophy? Translated by Hugh Tomlinson, and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkler, Michal Beth. 2019. Between Intention and Reception: Textual Meaning-Making in Intersubjective Perspective. In Biblical Exegesis without Authorial Intention? Interdisciplinary Approaches to Authorship and Meaning. Edited by Clarissa Breu. Biblical Interpretation, 172. Leiden: Brill, pp. 72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Doel, Marcus. 2010. Representation and Difference. In Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories and Geography. Edited by Ben Anderson and Paul Harrison. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 117–30. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Scott S. 2011. Reconfiguring Mark’s Jesus: Narrative Criticism After Poststructuralism. The Bible in the Modern World. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epp, Eldon J. 1999. The Multivalence of the Term “Original Text” in New Testament Textual Criticism. Harvard Theological Review 92: 245–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Foucault, Michel. 1998. What Is an Author? In Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Edited by James D. Faubion. Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984. New York: The New Press, vol. 2, pp. 205–22. First published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Graybill, Rhiannon. 2016. Are We Not Men? Unstable Masculinity in the Hebrew Prophets. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Roland. 2010. Literary Criticism? Really? Arcade: The Humanities in the World. September 22. Available online: https://shc.stanford.edu/arcade/interventions/literary-criticism-really (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory J. Seigworth, eds. 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2007. The Epistemic Decolonial Turn: Beyond Political-Economy Paradigms. Cultural Studies 21: 211–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossberg, Lawrence. 2010. Affect’s Future: Rediscovering the Virtual in the Actual. In The Affect Theory Reader. Edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 309–38. [Google Scholar]

- Grusin, Richard, ed. 2015. Introduction. In The Nonhuman Turn. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. vii–xxix. [Google Scholar]

- Guattari, Félix. 1995. Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm. Translated by Paul Bains, and Julian Pefanis. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guattari, Félix. 2011. The Machinic Unconscious: Essays in Schizoanalysis. Translated by Taylor Adkins. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e). First published 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, Deryn, Robert E. Goss, Mona West, and Thomas Bohache, eds. 2006. The Queer Bible Commentary. London: SCM Press, Revised 2nd edition 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna J. 2008. When Species Meet. Posthumanities, 3. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoke, Jimmy. 2021. Feminism, Queerness, Affect, and Romans. Early Christianity and Its Literature. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Dong Hyeon. 2020. Simon the Tanner, Empires, and Assemblages: A New Materialist Asian American Reading of Acts 9:43. The Bible and Critical Theory 16: 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Dong Hyeon. 2023. Embracing the Nonhuman in the Gospel of Mark. Semeia Studies, 102. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keener, Craig S. 2014–2015. Acts: An Exegetical Commentary. 4 vols, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Koosed, Jennifer L., and Stephen D. Moore, eds. 2014. Affect Theory and the Bible. Biblical Interpretation. Leiden: Brill, 22, no. 4 (thematic issue). [Google Scholar]

- Kotrosits, Maia. 2015. Rethinking Early Christian Identity: Affect, Violence, and Belonging. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kotrosits, Maia. 2016. How Things Feel: Biblical Studies, Affect Theory, and the (Im)personal. Brill Research Perspectives in Biblical Studies. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Matthew D. C. 2017. Accidental Publication, Unfinished Texts and the Traditional Goals of New Testament Textual Criticism. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 39: 362–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Matthew D. C. 2018. Gospels before the Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Matthew D. C. 2023. The Publication of the Synoptics and the Problem of Dating. In The Oxford Handbook of the Synoptic Gospels. Edited by Stephen P. Ahearne-Kroll. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 175–203. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Law, John. 1992. Notes on the Theory of the Actor-Network: Ordering, Strategy, and Heterogeneity. Systems Practice 5: 379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, John. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Law, John, and John Hassard, eds. 1999. Actor Network Theory and After. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, Hayden. 2005. Cultural Geography: The Busyness of Being “More-than-Representational”. Progress in Human Geography 29: 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbon, Elizabeth Struthers. 2008. Narrative Criticism: How Does the Story Mean? In Mark and Method: New Approaches in Biblical Studies, 2nd ed. Edited by Janice Capel Anderson and Stephen D. Moore. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 29–58. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Massumi, Brian. 2021. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, 20th Anniversary ed. Post-Contemporary Interventions. Durham: Duke University Press. First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Massumi, Brian. 2002. Introduction. In A Shock to Thought: Expression after Deleuze and Guattari. Edited by Brian Massumi. New York: Routledge, pp. xiii–xxxix. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, Bradley H. 2022. Deleuze, Guattari and the Machine in Early Christianity: Schizoanalysis, Affect and Multiplicity. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Mesters, Carlos. 1983. The Use of the Bible in Christian Communities of the Common People. In The Bible and Liberation: Political and Social Hermeneutics. Edited by Norman K. Gottwald. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, pp. 119–33. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Stephen D. 2014. Untold Tales from the Book of Revelation: Sex and Gender, Empire and Ecology. Resources for Biblical Study, 79. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Stephen D. 2017. Gospel Jesuses and Other Nonhumans: Biblical Criticism Post-Poststructuralism. Semeia Studies, 89. Atlanta: SBL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Stephen D. 2023. The Bible after Deleuze: Affects, Assemblages, Bodies without Organs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Stephen D. 2024. Decolonial Theory and Biblical Unreading: Delinking Biblical Criticism from Coloniality. Brill Research Perspectives in Biblical Studies. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Stephen D., and Yvonne Sherwood. 2011. The Invention of the Biblical Scholar: A Critical Manifesto. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nealon, Jeffrey T. 2012. Post-Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Just-in-Time Capitalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nealon, Jeffrey. 2020. Jeffrey Nealon. In The Rebirth of American Literary Theory and Criticism: Scholars Discuss Intellectual Origins and Turning Points. Edited by H. Aram Veeser. New York: Anthem Press, pp. 221–34. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, Carol A., and Sharon H. Ringe, eds. 1992. Women’s Bible Commentary. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, Revised 3rd edition 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, Nat. 2018. Geographies of Affect. Oxford Bibliographies. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780199874002-0186 (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Parker, David C. 1997. The Living Text of the Gospels. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Puar, Jasbir K. 2007. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Next Wave: New Directions in Women’s Studies. Durham: Duke University Press, 10th Anniversary Edition 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Aníbal. 2000. Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South 1: 533–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, Aníbal. 2007. Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality. Cultural Studies 21: 168–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, A. Paige. 2020. Reading (with) Rhythm for the Sake of the (I-n-)Islands: A Rastafarian Interpretation of Samson as Ambi(val)ent Affective Assemblage. In Religion, Emotion, Sensation: Affect Theories and Theologies. Edited by Karen Bray and Stephen D. Moore. Transdisciplinary Theological Colloquia. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 126–44. [Google Scholar]

- Resseguie, James L. 2019. A Glossary of New Testament Narrative Criticism with Illustrations. Religions 10: 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, Ryan S., ed. 2022. Epistolary Affects. Biblical Interpretation. Leiden: Brill, vol. 30, no. 5 (thematic issue). [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, Albert. 2009. Out of My Life and Thought: An Autobiography, 60th Anniversary ed. Translated by Antje Bultmann Lemke. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. First published 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, Albert. 1968. The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of Its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. Translated by W. Montgomery. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. 2003. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia, Fernando F., and R. S. Sugirtharajah, eds. 2007. A Postcolonial Commentary on the New Testament Writings. The Bible and Postcolonialism, 13. New York: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Seigworth, Gregory J., and Carolyn Pedwell. 2023. Introduction: A Shimmer of Inventories. In The Affect Theory Reader 2: Worldings, Tensions, Futures. Edited by Gregory J. Seigworth and Carolyn Pedwell. Anima: Critical Race Studies Otherwise. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Seigworth, Gregory J., and Melissa Gregg. 2010. An Inventory of Shimmers. In The Affect Theory Reader. Edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Paul. 2021. Non-Representational Theory. Key Ideas in Geography. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Barbara Herrnstein. 2016. What Was “Close Reading”? A Century of Method in Literary Studies. Minnesota Review 87: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Eric C. 2022. The Affordances of bible and the Agency of Material in Assemblage. The Bible and Critical Theory 18: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Mitzi J. 2022. Abolitionist Messiah: A Man Named Jesus Born of a Doulē. In Bitter the Chastening Rod: Africana Biblical Interpretation. Edited by Mitzi J. Smith, Angela N. Parker and Ericka S. Dunbar Hill. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Snaza, Nathan. 2019. Animate Literacies: Literature, Affect, and the Politics of Humanism. Thought in the Act. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spinoza, Baruch. 2002. Ethics. In Spinoza: The Complete Works. Edited by Michael L. Morgan. Translated by Samuel Shirley. Indianapolis: Hackett. First published 1677. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, W. Randolph. 2013. Biblical Interpretation: An Integrated Approach, 3rd ed. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, Nigel. 2000. Afterwords. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 18: 213–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrift, Nigel. 2008. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. International Library of Sociology. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, Nigel. 2010. Understanding the Material Practices of Glamour. In The Affect Theory Reader. Edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Vannini, Phillip. 2015. Non-Representational Research Methodologies: An Introduction. In Non-Representational Methodologies: Re-Envisioning Research. Edited by Phillip Vannini. Routledge Advances in Research Methods. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Veeser, H. Aram, ed. 2020. The Rebirth of American Literary Theory and Criticism: Scholars Discuss Intellectual Origins and Turning Points. New York: Anthem Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Kenneth W. 2020. Kenneth W. Warren. In The Rebirth of American Literary Theory and Criticism: Scholars Discuss Intellectual Origins and Turning Points. Edited by H. Aram Veeser. New York: Anthem Press, pp. 171–82. [Google Scholar]

- West, Gerald O. 2015. Reading the Bible with the Marginalised: The Value/s of Contextual Bible Reading. Stellenbosch Theological Journal 1: 235–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Williams, Nina. 2020. Non-Representational Theory. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed. Edited by Audrey Kobayashi. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 7, pp. 421–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wimsatt, William K., Jr., and Monroe C. Beardsley. 1946. The Intentional Fallacy. The Sewanee Review 54: 468–88. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moore, S.D. Biblical Hermeneutics without Interpretation? After Affect, beyond Representation, and Other Minor Apocalypses. Religions 2024, 15, 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070755

Moore SD. Biblical Hermeneutics without Interpretation? After Affect, beyond Representation, and Other Minor Apocalypses. Religions. 2024; 15(7):755. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070755

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoore, Stephen D. 2024. "Biblical Hermeneutics without Interpretation? After Affect, beyond Representation, and Other Minor Apocalypses" Religions 15, no. 7: 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070755

APA StyleMoore, S. D. (2024). Biblical Hermeneutics without Interpretation? After Affect, beyond Representation, and Other Minor Apocalypses. Religions, 15(7), 755. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070755