Public Funds as a Source of Financing Revalorization of Sacral Historical Monuments: The Example of Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Review

- (a)

- places where religious practices are held;

- (b)

- prayer;

- (c)

- meditation (Moon and Somers 2023);

- (d)

- pilgrimage;

- (e)

- healing.

“Is God indeed to dwell on earth? If the heavens and the highest heavens cannot contain you, how much less this house which I have built! Regard kindly the prayer and petition of your servant, LORD, my God, and listen to the cry of supplication which I, your servant, utter before you this day. May your eyes be open night and day toward this house, the place of which you said, My name shall be there; listen to the prayer your servant makes toward this place. Listen to the petition of your servant and of your people Israel which they offer toward this place. Listen, from the place of your enthronement, heaven, listen and forgive. If someone sins in some way against a neighbor and is required to take an oath sanctioned by a curse, and comes and takes the oath before your altar in this house, listen in heaven; act and judge your servants. Condemn the wicked, requiting their ways; acquit the just, rewarding their justice. When your people Israel are defeated by an enemy because they sinned against you, and then they return to you, praise your name, pray to you, and entreat you in this house, listen in heaven and forgive the sin of your people Israel, and bring them back to the land you gave their ancestors”.1 Kgs, 8: 27–34 (The New American Bible 2012)

- the preparation of technical and conservation expertise;

- the preparation of conservation documentation;

- the execution of a construction project in accordance with the provisions of the construction law;

- safeguarding and preserving the substance of the monument;

- the structural stabilization of the components of the monument or their reconstruction to the extent necessary for the preservation of the monument;

- the revitalization or completion of architectural plasters and cladding or their complete reconstruction, taking into account the characteristic colours of the monument;

- the revalorization or complete reconstruction of windows, including door frames and shutters, exterior doors, roof trusses, roofing, gutters and drain pipes;

- the modernization of electrical installations in wooden monuments or monuments that have original wooden components and accessories;

- the purchase of conservation and construction materials, necessary for the execution of works and works on the monument entered in the register.

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Sacral Historical Monuments in Poland—A Statistical Approach

4.2. Potential Public Sources of Financing for the Revalorization of Sacral Monuments in Poland

- (1)

- constitute a resource of cultural goods registered in the register of monuments, which have significant (due to their historical, scientific or artistic value) significance for the heritage and cultural development of a given nation (Article 6(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland creates conditions for the dissemination and equal access to cultural goods, which are the source of the identity of the Polish nation, its survival and development), and their care and protection is:

- (a)

- the task of the State (Article 73 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland—everyone is guaranteed freedom of artistic creation, scientific research and the publication of its results, freedom of teaching, as well as freedom to use cultural goods),

- (b)

- the tasks of local government units at individual levels (Act 1990, Art. 7(1)(9); Act 1998a, Art. 4(1)(7); Act 1998b, Art. 14(1)(3)),

- (2)

- perform important functions—from the point of view of the development of the individual, society, territory and economy,

- (1)

- at the central level:

- (a)

- collected in the state budget,

- (b)

- remaining in the special purpose funds account:

- National Fund for the Protection of Monuments;

- Church Fund.

- (2)

- at the local government level—collected in the budgets of municipalities, powiats and voivodships.

- (a)

- the voivodship conservator of monuments (with regard to funds from the state budget in the part of which the voivodship is in charge).

4.3. Public Funds Earmarked for the Revalorization of Sacral Historical Monuments in Poland in the Years 2017–2022

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Act. 1950. Ustawa z dnia 20 marca 1950 r. o przejęciu przez Państwo dóbr martwej ręki, poręczeniu proboszczom posiadania gospodarstw rolnych i utworzeniu Funduszu Kościelnego (Dz. U. Nr 9, poz. 87 z późn. zm.). Dziennik Ustaw, March 20. [Google Scholar]

- Act. 1962. Ustawa z dnia 15 lutego 1962 r. o ochronie dóbr kultury (Dz. U. z 1999 r. poz. 98 z późn. zm.). Dziennik Ustaw, November 12. [Google Scholar]

- Act. 1990. Ustawa z dnia 8 marca 1990 r. o samorządzie gminnym (Dz. U. z 2023 r. poz. 40). Dziennik Ustaw, March 8. [Google Scholar]

- Act. 1998a. Ustawa z dnia 5 czerwca 1998 r. o samorządzie powiatowym (Dz. U. z 2022 r. poz. 1526). Dziennik Ustaw, June 9. [Google Scholar]

- Act. 1998b. Ustawa z dnia 5 czerwca 1998 r. o samorządzie województwa (Dz. U. z 2022 r. poz. 2094). Dziennik Ustaw, June 5. [Google Scholar]

- Act. 2003. Ustawa z dnia 23 lipca 2003 r. o ochronie zabytków i opiece nad zabytkami (Dz.U. z 2022 r. poz. 840 ze zm.). Dziennik Ustaw, July 23. [Google Scholar]

- Act. 2020. Ustawa z dnia 31 marca 2020 r. o zmianie ustawy o szczególnych rozwiązaniach związanych z zapobieganiem, przeciwdziałaniem i zwalczaniem COVID-19, innych chorób zakaźnych oraz wywołanych nimi sytuacji kryzysowych oraz niektórych innych ustaw (Dz. U. z 2023 r. poz. 1327). Dziennik Ustaw, March 31. [Google Scholar]

- Akın, Ahmet. 2016. Tarihi süreç içinde cami ve fonksiyonları üzerine bir deneme. Hitit Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 15: 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Baesler, E. James. 2002. Prayer and Relationship with God II: Replication and Extension of the Relational Prayer Model. Review of Religious Research 44: 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barełkowski, Robert. 2014. Funkcja jako nośnik continuum w zabytku architektury. In Wartość funkcji w obiektach zabytkowych. Edited by Bogusław Szmygin. Warszawa: Polski Komitet Narodowy ICOMOS, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Politechnika Lubelska, pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Battaino, Claudia. 2020. The hidden truth in architecture. In Defining the Architectural Space. Edited by Wacław Celadyn. Wydawca: Oficyna Wydawnicza ATUT—Wrocławskie Wydawnictwo Oświatowe, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, Hans Dieter. 1997. Jesus and the Purity of the Temple (Mark 11:15–18): A Comparative Religion Approach. Journal of Biblical Literature 116: 455–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijak, Paweł. 2019. Zabytki sakralne w systemie prawnym Polski—uwagi de lege ferenda. Cywilizacja i Polityka 17: 257–70. [Google Scholar]

- Boselli, Goffredo. 2014. The Spiritual Meaning of the Liturgy. School of Prayer, Source of Life. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Concordat. 1925. Konkordat pomiędzy Stolicą Apostolską a Rzeczpospolita Polską, podpisany w Rzymie dn. 10 lutego 1925 r. (Dz. U. R. P. z 1925 r. Nr 47, poz. 324). Dziennik Ustaw, April 23. [Google Scholar]

- Concordat. 1993. Konkordat między Stolicą Apostolską i Rzecząpospolitą Polską, podpisany w Warszawie dnia 28 lipca 1993 r. (Dz. U. z 1998 r. Nr 51, poz. 318). Dziennik Ustaw, February 23. [Google Scholar]

- Constitution of the Republic of Poland. 1997. Konstytucja Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej z dnia 2 kwietnia 1997 (Dz. U. z 1997 r. Nr 78, poz. 483). Dziennik Ustaw, April 2. [Google Scholar]

- Convention. 1954. Konwencja o ochronie dóbr kultury w razie konfliktu zbrojnego wraz z regulaminem wykonawczym do tej konwencji oraz protokół o ochronie dóbr kultury w razie konfliktu zbrojnego, Haga 1954 (Dz.U. z 2012 r. poz. 248). Dziennik Ustaw, November 17. [Google Scholar]

- Convention. 1972. Konwencja w sprawie ochrony światowego dziedzictwa kulturalnego i naturalnego, przyjęta w Paryżu dnia 16 listopada 1972 r. przez Konferencję Generalną Organizacji Narodów Zjednoczonych dla Wychowania, Nauki i Kultury na jej siedemnastej sesji (Dz. U. z 1976 r. Nr 32, poz. 190). Dziennik Ustaw, May 6. [Google Scholar]

- Decree. 1933. Rozporządzenie Prezesa Rady Ministrów i Ministrów: Spraw Wewnętrznych, Spraw Wojskowych, Skarbu, Sprawiedliwości, Wyznań Religijnych i Oświecenia Publicznego oraz Rolnictwa i Reform Rolnych z dnia 25 marca 1933 r. w sprawie wykonania postanowień Konkordatu, zawartego pomiędzy Stolicą Apostolską a Rzecząpospolitą Polską. (Dz. U. z 1933 r. Nr 24, poz. 197). Dziennik Ustaw, March 25. [Google Scholar]

- de Wildt, Kim, Martin Radermacher, Volkhard Krech, Beate Löffler, and Wolfgang Sonne. 2019. Transformations of ‘Sacredness in Stone’: Religious Architecture in Urban Space in 21st Century Germany—New Perspectives in the Study of Religious Architecture. Religions 10: 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deibl, Jakob Helmut. 2020. Sacred Architecture and Public Space under the Conditions of a New Visibility of Religion. Religions 11: 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmock, Matthew, and Andrew Hadfield, eds. 2008. The Religions of the Book: Christian Perceptions. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1400–660. [Google Scholar]

- Doroz-Turek, Małgorzata. 2014. Współczesna utilitas w sakralnych obiektach zabytkowych na przykładach klasztorów i synagog. In Wartość funkcji w obiektach zabytkowych. Edited by Bogusław Szmygin. Warszawa: Polski Komitet Narodowy ICOMOS, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Politechnika Lubelska, pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Durydiwka, Małgorzata. 2015. Przestrzenie sakralne i sposoby ich wykorzystania we współczesnej turystyce. In Geografia na przestrzeni wieków. Tradycja i współczesność. Edited by Elżbieta Bilska-Wodecka and Izabela Sołjan. Kraków: Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, pp. 431–44. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Report of the Ministry of Finance. 2022. Sprawozdania finansowe Ministra Finansów z realizacji budżetu. Available online: www.mf.gov.pl (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Flisek, Aneta, and Wioletta Żelazowska, eds. 2014. Kodeks Prawa Kanonicznego. Warszawa: C. H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Gerecka-Żołyńska, Anna. 2007. Realizacja międzynarodowych standardów ochrony dziedzictwa kulturalnego w polskiej ustawie o ochronie zabytków i opiece nad zabytkami. Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny 4: 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Gary, and Alan F. Segal. 1995. The Hebrew Bible: Role in Judaism. In The Routledge Encyclopedia of Theology. Edited by Peter Byrne and Leslie Houlden. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist, Roberta. 2020. Sacred Heritage. Monastic Archaeology, Identities, Beliefs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guerzoni, Guido. 1997. Cultural Heritage and Preservation Policies: Notes on the History of the Italian Case. In Economic Perspectives on Cultural Heritage. Edited by Michael Hutter and Ilde Rizzo. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 107–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halemba, Agnieszka. 2023. Church Building as a Secular Endeavour: Three Cases from Eastern Germany. Religions 14: 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcombe, Randall G. 1997. A Theory of the Theory of Public Goods. Review of Austrian Economics 10: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkei, Peter. 2019. Public Funding of Culture in Europe 2004–2017. The Budapest Observatory, March 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juja, Tadeusz, ed. 2011. Finanse publiczne. Poznań: Wyd. Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Poznaniu. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, Jacek, Andrzej Stasiak, and Bogdan Włodarczyk. 2002. Produkt turystyczny albo jak organizować poznawanie świata. Łódź: Wydawnictwo UŁ. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. 2004. Krytyka władzy sądzenia, tłum. J. Gałecki. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, John. S. 1969. Herbert Read on Education through Art. Journal of Aesthetic Education 3: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamer, Arjo. 2004. Cultural goods are good for more than their economic value. In Culture and Public Action. Edited by Vijayendra Rao and Michael Walton. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, pp. 138–62. [Google Scholar]

- Klamer, Arjo, Lyudmila Petrova, and Anna Mignosa. 2013. Cultural policies: A comparative perspective. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage. Edited by Ilde Rizzo and Anna A. Mignosa. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kulik, Małgorzata Maria, Halina Rutyna, Małgorzata Steć, and Anna Wendołowska. 2022. Aesthetic and Educational Aspects of Contact with Contemporary Religious Architecture. Religions 13: 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Local Data Bank. 2023. Bank Danych Lokalnych Głównego Urzędu Statystycznego. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/dane/podgrup/temat (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Marshall, David, and Lucinda Mosher, eds. 2013. Prayer: Christian and Muslim Perspectives. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCain, Roger. 2006. Defining cultural and artistic goods. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. Edited by Victor A. Ginsburgh and David Throsby. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 1, pp. 147–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquida, Peri, and Kellin Cristina Melchior Inocêncio. 2016. Art and Education or Education through Art: Educating through Image. Creative Education 7: 1214–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molski, Piotr. 2014. Funkcja—Atrybutem wartości i ochrony zabytku. In Wartość funkcji w obiektach zabytkowych. Edited by Bogusław Szmygin. Warszawa: Polski Komitet Narodowy ICOMOS, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Politechnika Lubelska, pp. 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Hyungong, and Brian D. Somers. 2023. The Current Status and Challenges of Templestay Programs in Korean Buddhism. Religions 14: 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, Janusz. 2011. Sakralna przestrzeń—Charakterystyka oraz wybrane treści ideowe i symboliczne. Seminare t 29: 269–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniszczuk, Jerzy, ed. 2011. Współczesne państwo w teorii i praktyce. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH. [Google Scholar]

- Ossowski, Stanisław. 1958. U Podstaw Estetyki. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson, Magnus. 1978. Hêkāl [Temple]. In Theological Dictionary o f the Old Testament. Edited by G. Johannes Botterweck and Helmer Ringgren. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, vol. 3, pp. 382–88. [Google Scholar]

- Owsiak, Stanisław. 2005. Finanse publiczne. Teoria i praktyka. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, Alan T. 1994. Welfare Economics and Public Subsidies to the Arts. Journal of Cultural Economics 18: 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podemski, Maciej. 2006. W Unii Europejskiej. Wsparcie Europejskiego Obszaru Gospodarczego. Przegląd Geologiczny 54: 830–31. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylska, Lucyna. 2005. Pojęcie przestrzeni sakralnej. In Geografia i sacrum: Profesorowi Antoniemu Jackowskiemu w 70. rocznicę urodzin. Tom 2. Edited by Bolesław Domański and Stefan Skiba. Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński. Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej, pp. 381–87. [Google Scholar]

- Raport Najwyższej Izbę Kontroli z kontroli wykonania budżetu państwa w 2022 roku. 2023. Available online: www.nik.gov.pl (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Register of Archaeological Monuments. 2023. Rejestr zabytków archeologicznych. Available online: https://dane.gov.pl/pl/dataset/94,zestawienie-danych-statystycznych-z-rejestru-zabytkow-zabytki-archeologiczne/resource/51888,zestawienie-danych-statystycznych-z-rejestru-zabytkow-zabytki-archeologiczne/table?page=1&per_page=20&q=&sort= (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Register of Immovable Monuments. 2023. Rejestr zabytków nieruchomych. Available online: https://dane.gov.pl/pl/dataset/154,zestawienie-danych-statystycznych-z-rejestru-zabytkow-zabytki-nieruchome/resource/51889,zestawienie-danych-statystycznych-z-rejestru-zabytkow-zabytki-nieruchome/table?page=1&per_page=20&q=&sort= (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Register of Movable Monuments. 2023. Rejestr zabytków ruchomych. Available online: https://dane.gov.pl/pl/dataset/223,zestawienie-danych-statystycznych-z-rejestru-zabytkow-zabytki-ruchome/resource/49589,zestawienie-danych-statystycznych-z-rejestru-zabytkow-zabytki-ruchome/table?page=1&per_page=20&q=&sort= (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Rizzo, Ilana, and David Throsby. 2006. Cultural heritage: Economic analysis and public policy. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. Edited by Victor A. Ginsburgh and David Throsby. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 1, pp. 983–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytel, Grzegorz. 2014. Etyczne uwarunkowania zmiany funkcji w zabytkowych mauzoleach, w: Bogusław Szmygin. Warszawa: Polski Komitet Narodowy ICOMOS, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Politechnika Lubelska, pp. 265–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sienkiewicz, Tomasz. 2013. Administracyjnoprawne warunki ingerencji administracji publicznej w sposób korzystania z obiektów sakralnych Kościoła katolickiego wpisanych do rejestru zabytków. Studia z Prawa Wyznaniowego. Lublin: Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski Jana Pawła II, tom, vol. 16, pp. 301–33. [Google Scholar]

- Snowball, Jen D. 2013. The economic, social and cultural impact of cultural heritage: Methods and examples. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage. Edited by Ilde Rizzo and Anna A. Mignosa. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 438–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sołkiewicz-Kos, Nina, Nina V. Kazhar, and Mariusz Zadworny. 2022. Project of Revalorization and Extension of the Historic Monastery Complex of St Sigismund’s Parish in Częstochowa (Poland)—A Case Study. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Arts 12: 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot-Radziszewska, Elżbieta. 2014. Zmiana funkcji pierwotnej w obiektach zabytkowych w Muzeach na Wolnym Powietrzu. Szanse i zagrożenia. In Wartość funkcji w obiektach zabytkowych. Edited by Bogusław Szmygin. Warszawa: Polski Komitet Narodowy ICOMOS, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Politechnika Lubelska, pp. 289–98. [Google Scholar]

- The New American Bible. 2012. Revised Edition. The Leading Catholic Resource for Understanding Holy Scripture. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, David. 2001. Economics and Culture. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, David. 2006. Introduction and Overview. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture. Edited by Victor A. Ginsburgh and David Throsby. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 1, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, Bonnie Bowman. 2009. For God Alone. A Primer on Prayer. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tkaczyński, Jan Wiktor, Rafał Willa, and Marek Świstak. 2008. Fundusze Unii Europejskiej 2007–2013. Cel-Działania-Środki. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski, Andrzej. 2000. Dziedzictwo i zarządzanie. In Problemy zarządzania dziedzictwem. Edited by Krystyna Gutowska. Warszawa: Res Publica Multiethnica, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Traynor (JCL), Scott. 2013. The Parish as a School of Prayer: Foundations for the New Evangelization. Omaha: The Institute for Priestly Formation. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, Frederick. 2006. The Making of Cultural Policy: A European Perspective. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, 1st ed. Edited by Victor A. Ginsburgh and David Throsby. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 1, chp. 34. pp. 1183–221. [Google Scholar]

- Wischmeyer, Oda. 2015. Prayer and Emotion in Mark 14: 32–42 and Related Texts. In Ancient Jewish Prayers and Emotions: Emotions Associated with Jewish Prayer in and around the Second Temple Period. Edited by Stefan C. Reif and Renate Egger-Wenzel. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 335–50. [Google Scholar]

- Witwicki, Michał Tadeusz. 2007. Kryteria oceny wartości zabytkowej obiektów architektury jako podstawa wpisu do rejestru zabytków. Ochrona Zabytków 1: 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Włodarczyk, Małgorzata. 2014. Wartość zabytku—pamięć, teraźniejszość i nowa funkcja, a ekonomia wobec architektury powojennego modernizmu czasu PRL-u. In Wartość funkcji w obiektach zabytkowych. Edited by Bogusław Szmygin. Warszawa: Polski Komitet Narodowy ICOMOS, Muzeum Pałac w Wilanowie, Politechnika Lubelska, pp. 315–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zalasińska, Katarzyna. 2010. Prawna ochrona zabytków nieruchomych w Polsce. Warszawa: Oficyna Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Zalasińska, Katarzyna. 2020. Ustawa i ochronie zabytków i opiece nad zabytkami. Komentarz, Warszawa. Art. 3 pkt 1. Available online: https://sip-1legalis-1pl-1o6tok7bp2692.buhan.kul.pl/document-view.seam?documentId=mjxw62zogi3damrwg44dcny&refSource=search#tabs-metrical-info (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Zeidler, Kamil. 2007. Prawo ochrony dziedzictwa kultury. Warszawa: Wolters Kluwer Polska. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler, Kamil. 2017. Zabytki. Prawo i praktyka. Gdańsk and Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Eric. 1989. Buddhism and Education in Tang Times. In Neo-Confucian Education: The Formative Stage. Edited by Wm Theodor De Bary and John W. Chaffee. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 19–56. [Google Scholar]

| Voivodship/Region | Residential | Military | Civilian | Sacral | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 3976 | 192 | 1671 | 1672 | 1465 | 8976 |

| Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 1218 | 182 | 866 | 606 | 765 | 3637 |

| Lubelskie | 1258 | 297 | 654 | 1060 | 1120 | 4389 |

| Lubuskie | 2851 | 152 | 557 | 635 | 489 | 4684 |

| Łódzkie | 1168 | 75 | 469 | 611 | 641 | 2964 |

| Małopolskie | 2727 | 425 | 881 | 1046 | 1332 | 6411 |

| Mazowieckie | 3149 | 374 | 1389 | 1312 | 1855 | 8079 |

| Opolskie | 1615 | 124 | 483 | 578 | 567 | 3367 |

| Podkarpackie | 1945 | 385 | 752 | 1216 | 1004 | 5302 |

| Podlaskie | 785 | 239 | 396 | 718 | 313 | 2451 |

| Pomorskie | 1502 | 198 | 813 | 597 | 658 | 3768 |

| Śląskie | 2432 | 131 | 848 | 626 | 671 | 4708 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 537 | 162 | 275 | 561 | 431 | 1966 |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 3034 | 301 | 1069 | 1084 | 985 | 6473 |

| Wielkopolskie | 2888 | 186 | 1676 | 1510 | 1684 | 7944 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 954 | 75 | 768 | 1259 | 1357 | 4413 |

| Total | 32,039 | 3498 | 13,567 | 15,091 | 15,337 | 79,532 |

| Year | Executed Expenditure from the State Budget | Share of Expenditure on Subsidies and Grants in Chapter 92120 | Expenditure from Voivodship Budgets on Subventions and Subsidies in Chapter 92120 (PLN Thousands) | Joint Pool of RESOURCES from the Central Level for Subventions and Subsidies in Chapter 92120 (PLN Thousands) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 921—In Total (PLN Thousands) | Section 921—Subventions and Subsidies (PLN Thousands) | Chapter 92120—Subventions and Subsidies (PLN Thousands) | In joint Expenditure in Section 921 (%) | In Expenditure in Section 921 on Subventions and Subsidies (%) | |||

| 2017 | 3,331,937 | 2,615,830 | 115,195 | 3.46 | 4.40 | 32,685 | 147,880 |

| 2018 | 1,885,191 | 1,434,056 | 139,908 | 7.42 | 9.76 | 66,548 | 206,456 |

| 2019 | 2,542,976 | 1,766,198 | 142,160 | 5.59 | 8.05 | 57,352 | 199,512 |

| 2020 | 4,559,883 | 2,729,079 | 141,395 | 3.10 | 5.18 | 51,724 | 193,119 |

| 2021 | 4,691,419 | 2,854,563 | 169,808 | 3.62 | 5.95 | 55,231 | 225,039 |

| 2022 | 5,144,206 | 2,958,667 | 107,000 | 2.08 | 3.62 | 77,892 | 184,892 |

| Voivodship (Region) | Expenditure from Chapter 92120 (PLN Thousands) | Share of the Conservationists of Monuments Expenditure in the Joint Pool of Expenditures by Conservation Officers Spent on the Protection and Care of Historical Monuments (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 8894.7 | 11.42 |

| Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 1497.0 | 1.92 |

| Lubelskie | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Lubuskie | 769.6 | 0.99 |

| Łódzkie | 1493.9 | 1.92 |

| Małopolskie | 9997.2 | 12.83 |

| Mazowieckie | 18,938.8 | 24.31 |

| Opolskie | 9262.3 | 11.89 |

| Podkarpackie | 9837.4 | 12.69 |

| Podlaskie | 7366.0 | 9.46 |

| Pomorskie | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Śląskie | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 2109.8 | 2.71 |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 4440.0 | 5.70 |

| Wielkopolskie | 2259.2 | 2.90 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 1026.5 | 1.32 |

| Total | 77,892.4 | 100.00 |

| Year | National Fund for the Protection of Heritage Monuments | Church Fund | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment Subsidies (PLN Thousands) | Subsidies from the State Budget (PLN Thousands) | Expenditure on the Conservation and Revalorization of Sacral Historical Monuments (PLN Thousands) | Share in the Expenditure on the Conservation and Revalorization of Sacral Historical Monuments in Subsidies Allocated from the State Budget (w %) | ||

| Plan | Execution | ||||

| 2017 | 0 | 0 | 158,750.00 | 10,636.40 | 6.70 |

| 2018 | 2321 | 0 | 179,747.00 | 29,713.00 | 16.53 |

| 2019 | 389 | 0 | 170,560.00 | 10,161.17 | 5.96 |

| 2020 | 0 | 0 | 181,818.00 | 10,463.53 | 5.75 |

| 2021 | 290 | 273 | 193,664.00 | 10,710.50 | 5.53 |

| 2022 | 88,700 | 83,064 | 192,800.00 | 10,509.00 | 5.45 |

| Year | Communes without Towns with Powiat Rights | Towns with Powiat Rights * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expenditure in Chapter 92120 (PLN Thousands) | Share of Expenditure in Section 921 in the Total Expenditure (%) | Expenditure in Chapter 92120 (PLN Thousands) | Share of Expenditure in Section 921 in the Total Expenditure (%) | |

| 2017 | 158,922.24 | 3.0 | 153,551.24 | 3.2 |

| 2018 | 308,699.72 | 3.5 | 213,119.99 | 3.4 |

| 2019 | 279,008.96 | 3.3 | 212,956.80 | 3.2 |

| 2020 | 239,974.74 | 2.9 | 168,466.19 | 3.0 |

| 2021 | 244,768.70 | 2.9 | 184,172.04 | 2.9 |

| 2022 | 256,847.97 | 3.0 | 248,876.29 | 2.9 |

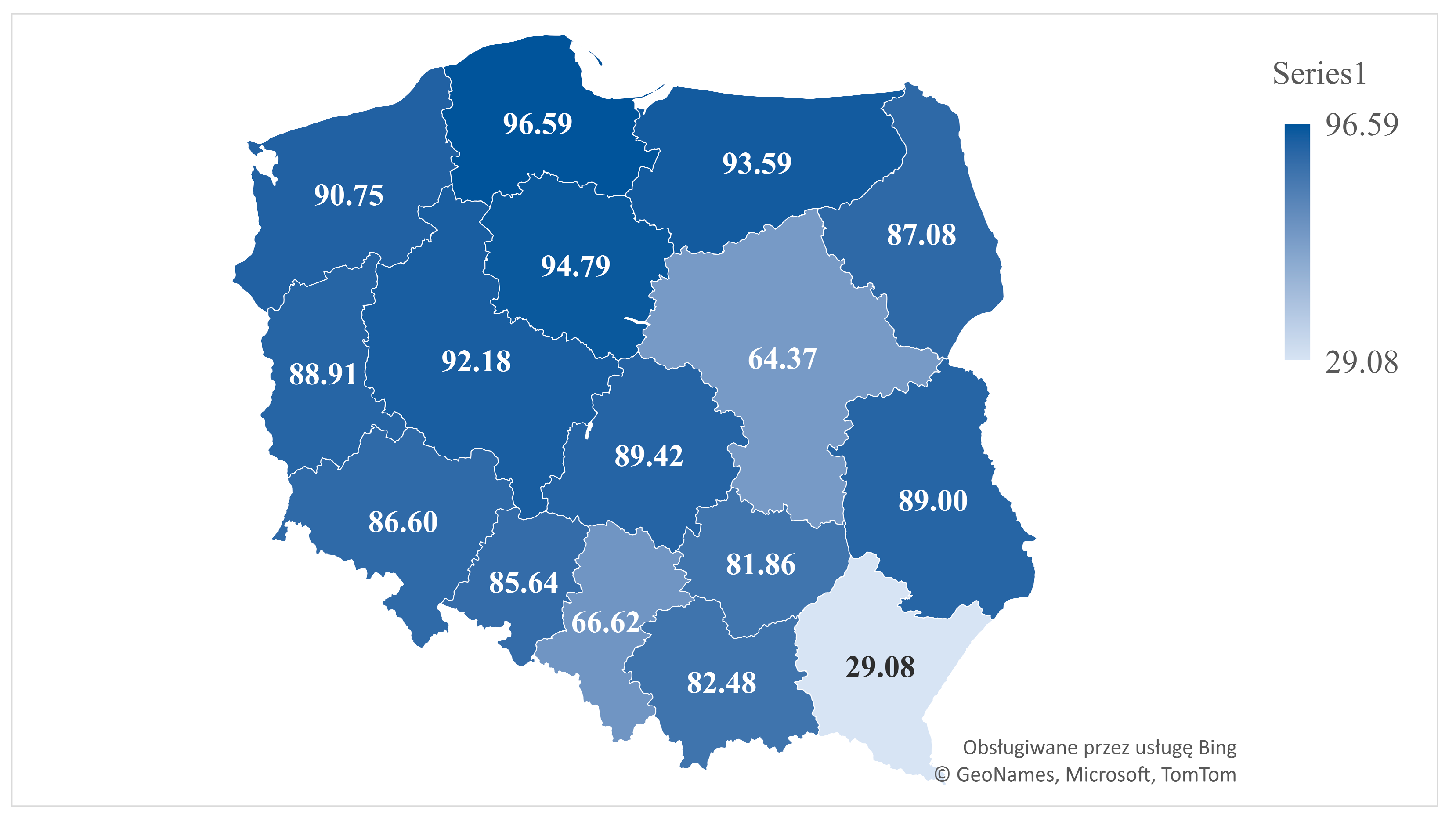

| Voivodship (Region) | Expenditure in Chapter 92120— The Protection and Care of Historical Monuments (PLN Thousands) | Expenditure on the Protection and Care of Historical Monuments in the Budgets of Municipalities and Towns with Powiat Rights in Poland in 2022 (in %) |

|---|---|---|

| Dolnośląskie | 88,857.92 | 17.57 |

| Kujawsko-Pomorskie | 21,562.56 | 4.26 |

| Lubelskie | 39,389.60 | 7.79 |

| Lubuskie | 13,468.54 | 2.66 |

| Łódzkie | 17,614.03 | 3.48 |

| Małopolskie | 56,568.18 | 11.19 |

| Mazowieckie | 58,068.42 | 11.48 |

| Opolskie | 10,553.42 | 2.09 |

| Podkarpackie | 24,652.87 | 4.87 |

| Podlaskie | 10,825.63 | 2.14 |

| Pomorskie | 24,990.23 | 4.94 |

| Śląskie | 53,508.19 | 10.58 |

| Świętokrzyskie | 6810.36 | 1.35 |

| Warmińsko-Mazurskie | 16,706.79 | 3.30 |

| Wielkopolskie | 30,127.08 | 5.96 |

| Zachodniopomorskie | 32,020.44 | 6.33 |

| Total | 505,724.27 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kotlińska, J.B.; Kuśpit, J.; Machniak, M. Public Funds as a Source of Financing Revalorization of Sacral Historical Monuments: The Example of Poland. Religions 2024, 15, 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050567

Kotlińska JB, Kuśpit J, Machniak M. Public Funds as a Source of Financing Revalorization of Sacral Historical Monuments: The Example of Poland. Religions. 2024; 15(5):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050567

Chicago/Turabian StyleKotlińska, Janina Beata, Jarosław Kuśpit, and Mateusz Machniak. 2024. "Public Funds as a Source of Financing Revalorization of Sacral Historical Monuments: The Example of Poland" Religions 15, no. 5: 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050567

APA StyleKotlińska, J. B., Kuśpit, J., & Machniak, M. (2024). Public Funds as a Source of Financing Revalorization of Sacral Historical Monuments: The Example of Poland. Religions, 15(5), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15050567