1. Introduction

Nagarjunakonda, situated on the right bank of the Krishna River in the Macherla Mandal of the Guntur District, was a renowned center of commerce and learning in the ancient world. It was called Vijayapurī (the “city of victory”), the ancient capital of the Ikṣvāku Dynasty. There were four Ikṣvāku rulers at the zenith of the dynasty: Mahārājā Caṃtamūla I (r. 223–240 CE), Rājā [Mahārājā] Virāpurisadata (r. 240–265 CE), Rājā Ehuvula Caṃtamūla II (r. 265–275), and Rudra (r. 300–325). They succeeded the Sātavāhanas Dynasty (200 BCE–250 CE) (

Ray 1986;

Raghunath 2001). The Ikṣvāku capital, Vijayapurī, was situated to the west of the Lesser Dhammagiri (Naharallabddu mound) (

Vogel 1933, pp. 22–23;

Shastri 2008). On the eastern and northern sides of Vijayapurī is a plateau called Sri Parvata, where Buddhist establishments burgeon in addition to Brahmanical monuments (

Rao 1956, pp. 1–2;

Murthy 1977;

Rama 1995;

Kim 2011).

This study explores why Buddhist monasteries combined “Buddha mahāstūpas (mahācetiyas) with caityas (cetiyas)” in Nagarjunakonda. A universalization principle to construct monastic quarters emerged with the incorporation of broader intellectual programs, culminating in the combination of a mahācetiya (great stūpa) with two cetiyas (apsidal chapels) including a Buddha image or a stūpa to represent the building arrangement of sacred venues and dramatic events throughout Buddha’s life, from birth to Mahaparinirvana, passing through great departures, meditation, enlightenment, and preaching.

The inclination toward universalization is demonstrated in adopting broader intellectual programs combining a “mahācetiya with cetiyas”, modeled on the law of causality, Pratītyasamutpāda. The expressions cetiya and mahācetiya, stūpa and mahāstūpa, caitya and mahācaitya, are utilized flexibly, varying with the context, specific conditions, and contemporary styles. Mahācetiya, derived from “mahā” (great) combined with “cetiya” (shrine), signifies a “great shrine.“ The term “mahā” has evolved in its application as stūpas, which were initially of modest size, underwent gradual enlargement. The classification of caitya or mahācaitya is not indicative of a structured hierarchy but reflects general consensus. While caityas and mahācaityas are fundamentally similar, there are variations in their size and prominence, with some being larger and potentially more significant (

Skilling 2018).

Universalization, as exhibited by the sacrosanct structures, manifests symbolic, indexical, and iconic functions, underscoring the clear representation of architecture across cultures. It demonstrates continuity in design principles more distinctly when compared with monuments from India, Central Asia, China, Japan, and Korea. In the central precincts of temples, universalization articulates the causation principle through architectural integrations such as the combination of stupas with cetiyas, halls with pagodas, and the juxtaposition of dual cetiyas or pagodas adjacent to a stupa or hall. This principle also serves as a conceptual pivot for a mandala, grounded on transitions from ‘cause to effect’, ‘profane to sacred’, and ‘principle to knower’, and lays the foundational prelude to the three-dimensional realization of mandalas.

Universalization proposes that Buddhist architecture, by linking the Indian and Sinitic cultural spheres through Central Asia, exhibits a cosmopolitan nature. This tangible form in architectural representation preserves the universal reflexivity of historical narratives found in the Buddha’s biographies and even triggers the occurrence of the attainment of well-being and happiness land. Universalization also transcends previous notions of a dominant dynastic style that persisted through history, overcoming the constraints of dynastic periodization by establishing a universalized architectural language that spans epochs in Buddhist temple architecture.

The author posits that the homologous Indian Buddha stūpa/cetiya combinations are both grounded in the complementary pursuit of “merit-making” and “rebirth into the “sukha” for posthumous well-being and happiness.

The historical and cultural interactions between India and China have been pivotal in shaping the transmission and evolution of Buddhist ideas and practices. The use of inscriptions on “ubhaya-loka-hita-sukhāvahathanāya” in the Indian regions of Nagarjunakonda, Kanaganhalli, and Amarāvatī reflects a deeply rooted Buddhist principle centered on promoting well-being (welfare) and happiness in both worlds, ultimately leading to the attainment of nirvāṇa, and bringing well-being and happiness to the entire world. This inscription “ubhaya-loka-hita-sukhāvahathanāya”, commonly engraved on āyaka-pillars at these heritage sites, underscores the importance of fostering well-being and happiness for the benefit of the entire world.

The simple phrases that express wishes for the long life and happiness of all beings can be traced from the aspirations of the Buddha to the inscriptions of King Aśoka, which were spread epigraphically throughout Northwest India and beyond. In fact, the compound term “hita-sukhā” is commonly found in Aśokan inscriptions. King Aśoka was dedicated to promoting the well-being of the entire world, recognizing that the basis for such endeavors rested in the pursuit and realization of objectives. He believed that no deeds were more noble than those aimed at the welfare of all humanity. These historical records underscore the king’s deep commitment to the well-being and happiness of the entire world (

Bloch 1950, pp. 108–10;

Skilling 2018, pp. 61–65).

The early translation of “

sukhāvatī” into Chinese as “

xumoti 須摩提” reflects the initial attempts to render Buddhist concepts into the Chinese linguistic and cultural contexts prior to 220 CE. This Chinese transliteration of

sukhāvatī to

xumoti,

xuhemmti 須呵摩提,

xuati 須阿提, and

xuhemochi 須訶摩持 signify the beginnings of the integration into ancient China in Buddhism (

Xiao 2009, pp. 279–80). Over time, the term evolved, with “

anle 安樂” being used from 220 CE to convey the notions of comfort and happiness. This was eventually replaced by “

jile 極樂” for extreme happiness and “

jingtu 淨土” for pure land, reflecting a deepening understanding and localization of Buddhist teachings (

Fujita 1970;

Yutaka 1978;

Tsukamoto 1986;

Nakamura 1975;

Mizuno and Toshio 1941;

Kim 2021).

From the second century onwards, three primary Pure Land Sutras emphasizing Buddhist well-being and happiness emerged. In the third century, Samghavarman 康僧鎧 translated the

Larger Sukhāvatī vyuha sutra 佛說無量壽經 (Taisho 12, no 360) (

Buddhabhadra n.d.a.), while in the fifth century, Kumarajiva 鳩摩羅什 translated the

Smaller Sukhāvatī vyuha sutra 佛說阿彌陀經 (Taisho 12, no 366) and Jiaangyeshe translated the

Amitayurdhyana sutra 觀無量壽經 (Taisho 12, no 365) (

Kumārajīva n.d.). Interestingly, the

Smaller Sukhāvatī vyuha sutra translated the concept of well-being and happiness as “utmost bliss” using the term “

jile”, while the

Larger Sukhāvatī vyuha sutra used the term “

jingtu” to convey purity and the attachment of nirvāṇa.

The expressions of “

jile” and “

jingtu” can be seen as part of the ancient Chinese efforts to properly understand Buddhist concepts through the Taoist background that originated in ancient China. The term

anle-jingtu or Jile-jingtu must be derived from Tuanlan’s typical Taoist background (

Xiao 2009).

The terms “

jile” and “

jingtu” used in these scriptures are interchangeable and commonly convey the same meaning, encapsulating the aspiration for utmost bliss, happiness, attainment of nirvāṇa, and desire to be reborn in a joyful place free from sorrow. This aligns with the ancient Indian aspiration for the well-being and happiness of all beings across all worlds. Its meaning refers to a place of ideal nirvana and pleasure.

Sukhāvatī means “utmost bliss”, as in Chinese

jile (

Xiao 2009, pp. 279–80). The progression from “

xumoti” (well-being and happiness) and

jīle (utmost bliss) to “

jingtu” (pure and utmost bliss land) illustrates the dynamic adaptation of Buddhism within Chinese culture searching for the more exact interpretations of the

Sukhāvati’s key concepts. The correct transliteration of

sukhāvahathanāya in East Asia signified the well-being and happiness of all beings without any anxiety (

Xiao 2009, pp. 279–80). Ancient India and China, which had a strong autocratic monarchies and slave societies at that time, served as an important background for the continued development of Buddhism through the masses.

Therefore, this study aims to highlight the underlying principle that, based on such ideology, served as a driving force in maintaining sacred Buddhist sites through the arrangement of mahācetiyas with cetiyas, which represent a reenactment of Buddha’s life. It also seeks to emphasize that the same principle of pursuing well-being and happiness has universally persisted as a tool across different Buddhist schools. This connection is established through historiographical texts, including epigraphy and literary evidence, elucidating the ritual life and aims of devotees. The inception of such a universal synthesis establishes a new standard for the narrative law of causation.

2. Research Method and Scope

This study focuses on the original environment of architectural remains during the excavation of derelict ruins from Buddhist sectarian monasteries. These monasteries were constructed under the patronages of Ikṣvāku’s rulers and their families, merchants, and monks, particularly those intimately bound with the Mahīśāsaka school, Mahāsaṅghika (the sub-sectarian schools of Aparamahāvinaseliyas (Aparamahāvinaśaila) and Bahuśrutīya), and Sthaviravāda (Mahāyāna Theravāda) introduced by Xuanzang, a Chinese pilgrim. Three chief expeditions were performed in Nagarjunakonda—by Longhurst between 1927 and 1931, Ramachandra in 1938, and Subrahmanyam in 1954–1960. They discovered mahāstūpas (mahācetiyas), apsidal chapels (cetiyas), and monk monasteries (

Longhurst 1938;

Subrahmanyam 1975;

Ramachandran 1953).

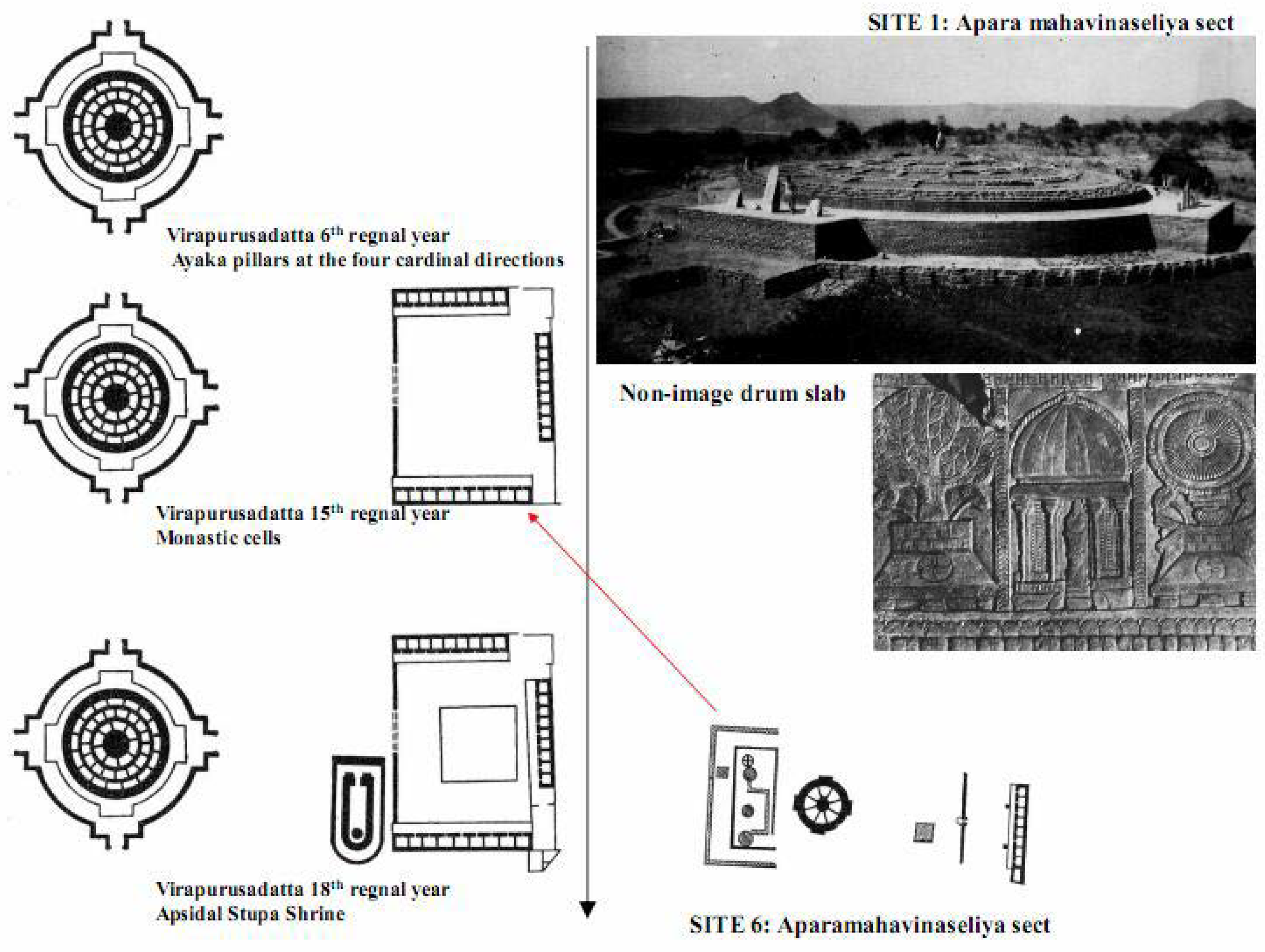

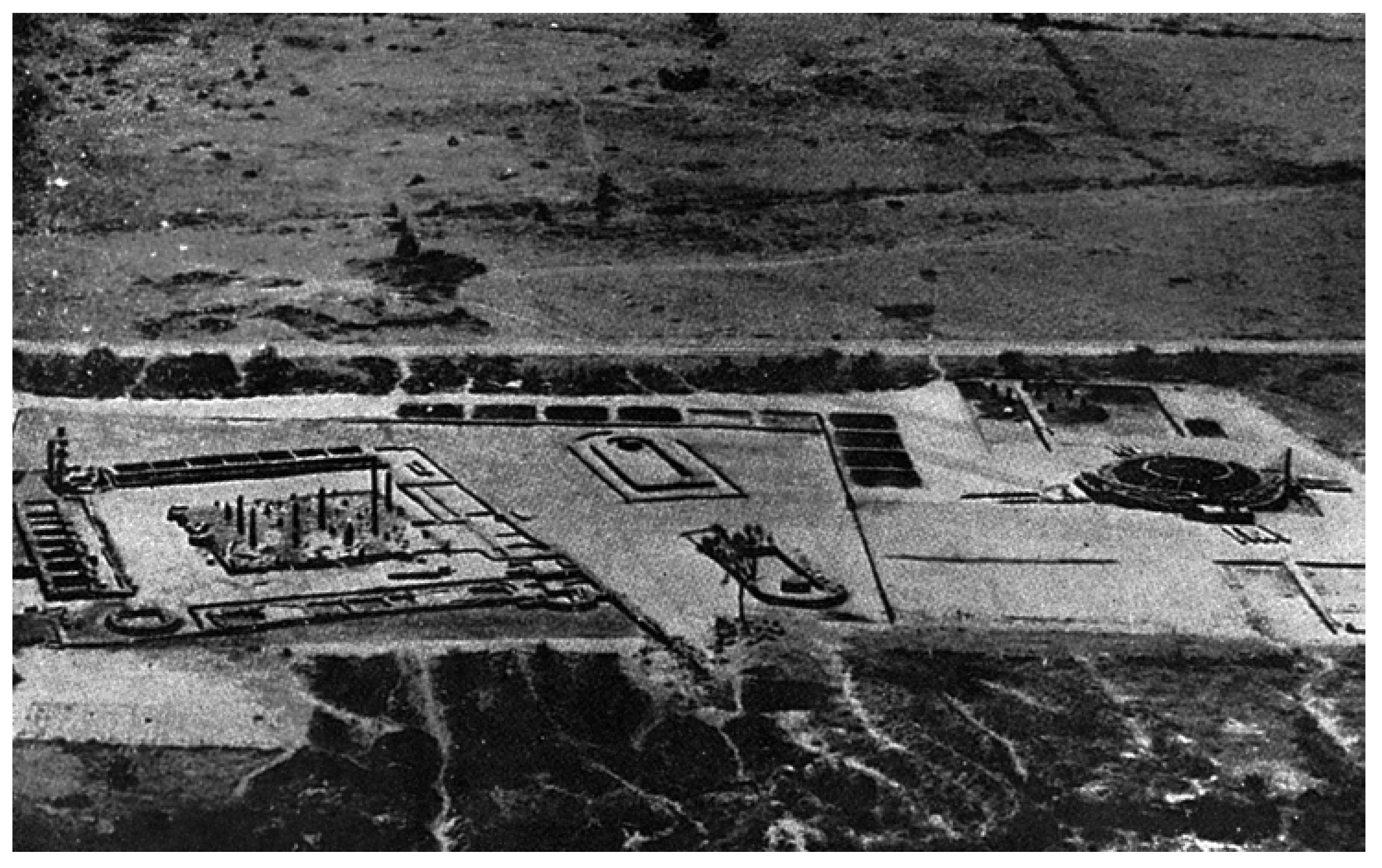

Hence, the three important archaeological works from 1927 to 1960 led to recognizing the significance of Buddhist monuments in the synthesis of one mahācetiya stūpa with cetiya apsidal halls. Seventy inscriptions are provided from the sites; this study elucidates the stūpa with apsidal hall layouts regarding the Mahāsaṅghika sect and its late branches. Examples are Aparamahāvinasaliya (Sites 1, 6, and 9), Sthaviravāda (Sites 38 and 43), and Bahuśrutīya (Site 5), including anonymous sites (Sites 3 and 4) unknown to the Buddhist sects owing to the absence of inscriptions, and monastic sites (Sites 7 and 8) of the Mahīśāsaka sect. This study focuses on Sites 1 and 9. Their ground plans, emphasizing the arrangement of mahācetiyas and cetiyas, essentially reflected the singularities in the exegetical works of the Mahāsaṅghika monuments, although they were subsequently derived from Mahāsaṅghika. Similarly, regarding the site numbering already mentioned, this study uses Sarkar’s numbering system, which was considerably more reasonable than the ones previously adopted by Kuraishi, Longhurst, and Ramachandran. Sarkar’s numbering system focused on monastic compounds, respectively (in the incorporation of mahācetiya, cetiya, and monastic residence), employing parts of existing numbering methods to prevent confusion about future works (

Figure 1). The author reorganized the 70 inscriptions of Nagarjunakonda supplied by Tsukamoto Keisho, who compiled all Indian Buddhist inscriptions translated or arranged by Vogel, Sircar, Sarkar, Narasimha, Rama, Shizutani, and Sadakata in this study (

Vogel 1932,

1933;

Sarkar and Misra 1980;

Sarkar 1966,

1969;

Sircar 1939,

1963a,

1963b,

1966;

Tsukamoto 1986,

1996–1998;

Rao 1967;

Shizutani 1979;

Sadakata 1994).

3. Constructing Buddha’s Life in Mahāstūpas and Cetiya Combination by the Law of Causation as a Universalization Principle

The association of mahāstūpas with Vedic altars is evident in its reference to trees and sacrificial poles. The term “

stup” itself is defined as “to heap up or pile up”, aligning with the meanings of caitya and cetiya, which embody the concept of accumulation (

Irwin 1980). The

Mohesengzhilu 摩訶僧祇律 (

Buddhabhadra n.d.b.), a monastic code of Mahāsaṅghika, clarifies that mahāstūpas, as symbols of the Buddha, need not contain relics. This text differentiates between mahāstūpas (with relics) and cetiyas (without relics) and regards cetiyas as a place or shrine for commemorating holy events deduced from Buddha’s life, with Buddhist shrines always being called cetiyas and a type of stūpa being called mahācetiyas (

Kim 2015).

Nagarjunakonda Mahāsaṅghika monasteries formed the fundamental basis for the construction of mahāstūpas and cetiyas, which were integral components of most Buddhist temples. These sites were meticulously designed and arranged to fulfill specific “intended purposes” as inscribed by the devoted patrons of each location. They serve as repositories of indigenous semantic memories, preserving the sanctity of Buddha’s sacred places. Notably, the functional similarities shared among mahāstūpas and cetiyas ensure the retention of their original concepts and identities as a universalization principle. Additionally, vernacular building types seamlessly merge with the pre-existing notions of the Buddha’s sanctified locales, serving as both shrines and tombs for the Buddha. Simultaneously, the combination of mahāstūpas with cetiyas adheres to the causation principle. This principle traces a profound journey from enlightenment to nirvana, drawing from the narratives of Buddha’s life. These narratives are leveraged to establish a new architectural tradition by seamlessly integrating various building components and cementing them into a cohesive whole.

Mahācetiyas/cetiyas were meaningful emblems of sacred places and marvelous events to memorialize four to eight sites for the life of Buddha from his birth to Mahāparinirvāṇa (the achievement of nirvana). These locations encapsulate significant episodes in the life of Śākyamuni, each marked by marvels or miracles, and each represented by either a mahācetiya or a cetiya (

Skilling 2017, p. 29). In the convergence of mahāstūpas with caityas, Buddha’s biography is reified according to the law of causation, which states that everything arises from the condition of

paticcasamuppada. Completing the holy places through the combination is vital to communicating with monastic intellectuals and lay patronage because the monuments remind devotees of the sacred geography of venues associated with the life of the Buddha as a didactic device. The narrative principle of causation provides a formula to construct a mandala with such physical forms as architecture, painting, and statues; the reasonable groupings of buildings and images help remind us of their intended function in the procedure of rituals and practices.

The reminiscence of the honorific places in the biography of Buddha has provided a tangible dimension to Buddha’s presence in Buddhist architecture. It has also spurred pilgrimage, even where Buddha never lived during his lifetime. The construction of mahāstūpas and cetiyas played a significant role in these pilgrimages, serving as pedagogical instruments based on the concept of dependent origination revealed in the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra. In this sutra, Buddha states, “After I have passed away, monks, those making the pilgrimage to the shrines, honoring the shrines, will come (to places such as the sites of the Buddha’s birth, awakening, first teaching of the dhamma, and final nibbana). They will speak in this way: Here the Blessed One was born, here the Blessed One attained the highest, most excellent awakening.” He explains that constructing shrines at places significant in the Buddha’s biography honors Buddha through pilgrimage.

Synthesizing mahāstūpas with cetiyas within the primary areas of Buddhist compounds can be comprehended within the interdependent framework at each level. The evolution from “simple systems” to “complex systems” in the assemblage of these buildings contributed to the creation of a stable and integrated architectural system. The fundamental form of temple architecture consisted of a compound-based complex comprising numerous individual buildings. The magnitude of this architecture should not simply be considered in terms of each building but as a cohesive and interconnected complex, where each component is intricately linked to the next in a cause-and-effect relationship. These buildings can be seen both as self-contained entities with their unique characteristics and as dependent parts when viewed from a broader perspective. The stūpa and mahācetiyas serve as “metaphoric forms”, symbolizing Sumeru Mountain, the Buddha World, and Dharmakāya (dharma-body) with sariras, while also functioning as intermediate forms that represent various aspects of Buddha’s life story, providing context for the right functionality of the larger whole—the combination of mahāstūpas with cetiyas.

Similarly, the descriptions of worship engraved on the surface of mahāstūpas and cetiyas, relating to sacred places in Buddha’s biography, Jātaka tales, and Avadana stories, impart the Buddhist lesson that all existence is interconnected through causality. These practices and rituals are instrumental in realizing the essential law of causation in Buddhism. The expansion from a Buddha world to multiple Buddha worlds is concurrent with the development from a Buddha to numerous Buddhas (

Cho 1999). Each world system, called

Buddhaksetras (Buddha land), is presided over by a Buddha. According to this rule, the bas-reliefs of an image with a special

mudrā that adorned the platform of the mahāstūpas and cetiyas were converted into signs of pilgrimage and worship toward the sacred places of Buddha’s biography (

Wilhelm 1996, p. 19). Over time, these sacred places have begun to be converted into pure land.

4. Monuments as a Tool for Merit-Transferring and Rebirth in Well-being Paradise

The discoveries of inscriptions at Buddhist sites, including those related to Jainism, elucidate the primary motivations for constructing monuments and conducting religious services. Literary sources, epigraphical references, and material evidence collectively reveal that devout followers built these monuments to cultivate merits and attain rebirth into the pure land, ensuring posthumous well-being. This dual objective reflects a deep-seated religious aspiration in these communities, guiding their spiritual and architectural endeavors.

First, to generate merit through a puja ritual, devotees offer their blessings and goodness to all living beings. This act serves the dual purpose of seeking happiness and wealth in the tangible world and striving for spiritual enlightenment, known as nirvana. This practice involves the transfer of merit, referred to as “huixiang 迴向”. Therefore, devotees are required to construct mahāstūpas/cetiyas within the central precincts of Buddhist temples. The accumulation of merit is enhanced through the construction and integration of mahāstūpas with cetiyas.

Second, those aspiring to secure a posthumous rebirth in the Pure Land—characterized by “welfare and happiness in both the present and future worlds” (referred to as “

ubhaya-loka-hita-sukhāvahathanāya”)—must construct numerous Well-being and Happiness Lands with tangible architectural forms. These Pure Lands serve as symbolic representations of holy pilgrimage sites in the real world (

“Sahāloka” or

“Jambudvīpa”). The transformation of the real world into a pure land suggests that the living Buddha once graced these sacred sites, which subsequently became significant locations for accumulating merit through travel (

Bharati 1963;

Schopen 1988). Pure land architecture encompasses elements such as lotus ponds and bridges, which serve as symbolic connections between the current world of suffering and the future state of ultimate well-being. These architectural representations reflect the devotee’s aspiration for rebirth in paradise. They also make the concept of a paradisiacal environment credible to the devotees by solidifying iconological and ritual programs and incorporating architectural depictions in alignment with the teachings of the Pure Land sutras.

According to most inscriptions discovered in Nagarjunakoda, King Caṃtamūla of the Ikṣvāku dynasty (the first ruler) is credited with performances for the attainment of welfare and happiness, both in the worldly realm and Nirvana (Sites 1, 43, 9, etc.). These performances were occasioned as gifts, including gold, land, cows, oxen, and plows, numbering hundreds and thousands. Thus, land and its cultivation were emphasized, with the kings actively encouraging forest cultivation and agriculture (

Raghunath 2001, p. 7).

The Ikṣvāku inscriptions indicated that Camtasiri, the sister of King Siri Caṃtāmūla and paternal aunt (

pitcha), and later possibly the mother-in-law of King Siri Virāpurisadata, played a pivotal role as the principal donor for the subsidiary structures of the stūpa. The kings were adherent followers of the Brahmanical faith, constructing several shrines for Hindu deities, whereas their queens were responsible for the construction of Buddhist buildings and made liberal donations. The Bodhisiri (Site 43) and Chadasiri (Site 9), both

upasaikas, were primarily responsible for constructing numerous monasteries at Nagarjunakonda, supported by traders and businesspeople who frequented the site for commercial transactions (

Subrahmanyam 1975, p. 105). Most inscriptions mentioned the names of the Kings Caṃtāmūla and Virāpurisadata in the third or fourth century CE. The periods mentioned pertain to the subsidiary structures of the main stūpa, not the stūpa itself—the mahācetiya—which must be assigned to an earlier period.

Similarly, a few inscriptions mentioned the functions of a few buildings. In particular, the mandapa, as indicated by the inscriptions of Sites 3, 32 A, and 32 B, served as a venue for providing free meals. The inscriptions also mentioned the sala as a hall within the Buddhist monastery, suggesting that Chandrasri built a sala in honor of his parents and another for Theras (senior Buddhist monks). This implies that the sala is a monastic cell, known as the Vihāra. However, the Vihāras are no longer called private cells in most monasteries at the Nagarjunakonda Buddhist site. Originally, Vihāra implied the gathering of an original Vihāra as a monk’s cell, initially assigned to a hut. The conceptual range of Vihāra changed more as monastic quarters of monks’ cells separated from mahāstūpas outside the Vihāra when a main stūpa was relocated within the courtyard of monastic quarters.

In most of the Nagarjunakonda inscriptions, a remarkable aspect is that, through the construction of the mahāstūpas and cetiyas, the donor anticipates the accrual of merits from their gifts, which can be transferred (“

parinametunam”) to their relatives and friends (

Rupavataram 2003). A similar desire is evident in the inscription from the Puspabhadraswami Temple, which was established by the king’s wife and son for his long life and victory.

Ruling families and clans established temples, dedicating them to the Brahmanas and Buddha to affirm their sovereignty. As a result, these religious establishments evolved into key centers of cultural assimilation, mirroring the architectural and decorative styles of Brahmanic Hindu temples. Traditionally, historians have interpreted the spread of religion as occurring primarily through acculturation and Sanskritization, suggesting a process of absorbing local traditions and gods (

Ray 2004). Yet, archaeological evidence highlights the complex history and enduring nature of these sacred sites, revealing that their development cannot be fully understood through a simplistic, linear interpretation often derived from textual records alone.

Rather than this perspective of dominance and uniform assimilation, a greater emphasis should be placed on cooperative exchange and consensus to grasp the overall dynamic relationship. This reciprocal engagement stemmed from the shared value placed on religious locations and edifices by the communities that upheld and frequented them, highlighting a multifaceted interaction rather than a one-sided cultural imposition.

Additionally, the fruits are expected by transferring merits to himself, his relatives, and friends, resulting in their happiness in this world and the future pure land (

Kim 2021). To garner the merits through a puja ritual, devotees supported the management and the construction of monasteries. The devotees also believed that merits accumulated through investments in constructing a stūpa, shrine, and mandapa, and those monastic cells should be shared with other devotees (i.e., the transfer of merit,

huixiang). Thus, such activities result in attaining happiness, wealth in the real world, and the bliss of nirvana. Thus, to gain these merits, devotees had to build mahāstūpas and cetiyas in the central territory of the Buddhist temples. The roots of merit can be increased according to the accrued merits through the construction and combination of mahāstūpas and cetiyas.

5. Nagarjunakonda Toponym in the Relationship of Nāgārjuna

The toponym Nagarjunakonda is derived from remembrance through Acharya Nagarjuna, a well-known founder of the Madhyamika School and the first root of the Mahāyāna School, who resided in this region. The term “Konda” in Telugu signifies “a hill” of Nagarjuna (

Vogel 1933, p. 22;

Joshi 1965, pp. 16–17;

Bailey 1951, p. 7;

Lévi 1936, p. 106). Nagarjuna’s existence around Nagarjunakonda is demonstrated through the archaeological findings of the mahācetiyas and apsidal shrines. Nagarjuna composed Ratnāvalī in the neighboring areas of Nagarjunakonda, and the book contained an extensive section instructing the king on charity. Thus, Nagarjuna advises the king to provide the sangha with images of the Buddha, mahāstūpas, and Vihāras, along with the wealth necessary for their upkeep (

Nāgārjuna and Bel-dzek n.d.). Nāgārjuna’s Ratnāvalī instructs the king to recite a ritual formula three times a day in front of an “image of the Buddha” and to construct images of the Buddha “positioned on lotuses” (

Nāgārjuna and Hopkins 1998). Two Chinese monks recognized Nāgārjuna. Faxian法顯 (fourth to fifth centuries CE) confirmed that Bhramara-giri was a mountain where Nāgārjuna spent the latter part of his life, and Xuanzang 玄奘 (seventh century) stated that Nāgārjuna lived at Baluomoluoqili 跋邏末羅耆釐山, a transliteration of Bhramara-giri, although Xuanzang did not mention the monk Nāgārjuna who lived in the region when he visited monasteries in Andhra Pradesh. If Bhramara-giri is identified with Sriparvata, Sriparvata indicates a mountain on which Nāgārjuna lived. The mountain is situated in Nagarjunakonda, including the site of the Culadhammagiri Monastery (

Watters 1905, p. 207;

Xuanzang 2015).

Ratnāvalī’s appearance facilitated the construction and embellishment of the mahācetiyas and the installation of images sitting on lotuses within image shrines. This construction contributed to the reputation of the sites. Clear evidence of a Buddhist settlement is seen at Nagarjunakonda, the capital of Ikṣvāku. During the reign of the Ikṣvāku monarch Virāpurisadata, a mahācetiya, a dhātu Garbha referred to as “Śārīrika cetiya”, containing a physical relic, was erected. The Pūrvaśaila sect gained prominence in places farther east, primarily in Amarāvatī. Flourishing in the Sātavāhanas dominions in Andhra, particularly at Amarāvatī, the Pūrvaśaila sect is cited by Candrakirti in his Madhyamakavatara as “following the Pūrvaśaila.” These verses indicate the influence of Prajnaparamita ideas and have been associated by La Vallee Poussin with the emergence in the south of the dharmadhātugarbha doctrine (

La Vallée Poussin). They also establish circumstantial connections firmly linking Nāgārjuna to the Nagarjunakonda-Amarāvatī region during late Sātavāhanas (or possibly Ikṣvāku) times (

Shimada 2012).

Some Nagarjunakonda monasteries represent the early influence of devotional religion, incorporating mahāstūpas inside Vihāra enclosures (

Sarkar 1966, p. 78). Anthropomorphic images of the Buddha had wide currency around Gandhāra and Mathura as early as the first century. However, for most of the Sātavāhanas Dynasty, Deccan, Nagarjunakonda, and Amarāvatī lacked anthropomorphic representations of Buddha. The independent images sitting on lotus pedestals did not appear in the Ikṣvāku period until the construction of Site 9 in Nagarjunakonda. The anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha in independent sculptures began to emerge at Sites 3, 38, and 4. These were built in the regnal era of King Ehuvula Camtamula, dating back to the third century CE. The spread of independent images has also appeared at other Buddhist sites in southern India. The proof was discovered in the Brahmi script of the fifth century CE on the outer face of the drum of a Buddhist stūpa below the standing figure of Buddha in high relief at Gummididurru. The inscription reads, “For universal beatitude has been set up an image of Bhagavat (Buddha) by Sramana Rahula” (

Ramachandran 1953, p. 29). Therefore, it is plausible to surmise that Nāgārjuna might have lived at least during the late Sātavāhanas period. The use of images at Nagarjunakonda and Amarāvatī, which began in the third century, also suggests this. Additionally, Buddhas depicted on lotus thrones in that region are commonly dated to the third century or later. Moreover, although decisive proof has not been uncovered, extant evidence from archaeological excavations points to the most likely scenario of the existence of Nagarjuna in a Purvasailya, Aparasailya, or Caityaka monastery around Nagarjunakonda, Jaggayyapeta, and Amarāvatī during the time he wrote the Ratnávali. If this is valid, he might have begun his career as a royal protégé during the Sātavāhanas and, subsequently, the Ikṣvāku periods, and it is evident that the toponym Nagarjunakonda Hill of Nāgārjuna, derived from his name, implies he resided in the place. Considering the belief that the monk Nāgārjuna lived in the Nagarjunakonda and Mahāsaṅghika schools, Nagarjunakonda monasteries must have flourished. Similarly, in the third to fifth centuries, there is little doubt that the Mahāyāna school underwent a bifurcation as the main root of the Mahāsaṅghika sect, intertwining with new thoughts of other sects, such as Sarvāstivāda (later on Mūlasarvāstivāda) and Dharmagupta. Nāgārjuna, who likely resided in the Pūrvaśaila, Aparaśaila, and Caityaka monasteries during the time he wrote the

Ratnāvalī (

Walser 2005, pp. 87–88), expressed the goal of achieving the welfare and happiness of all beings, signifying a paradise (pure land). He emphasized transforming into great individuals through a renewed devotion to Buddhist images, mahāstūpas, and shrines (

Kim 2021). In contrast, the Nagarjunacarya inscription discovered beneath a high-relief standing Buddha image at Jaggayyapeta (Krishna, Andhra Pradesh), though not definitively dated earlier than the fifth century, suggests a possible fourth- or fifth-century timeframe for Nāgārjuna. This inference is drawn from a biography of Nāgārjuna attributed to Kumarajiva, which states, “Since Nāgārjuna left the world, more than a hundred years have passed.” Kumarajiva’s statement suggests a late third or early fourth-century context for Nāgārjuna’s activities (

Mabbett 1983,

1998).

From these historical contexts, Nagarjunakonda emerged as a great religious center, promoting both Brahmanical and Buddhist faiths and shaping the early phases of art and architecture affiliated with them. This extensive Buddhist establishment not only nourished several sects of Buddhism but also culminated in a full-fledged Mahāyāna pantheon.

6. Characteristics of Building Placement with Mahāstūpas and Cetiyas on the Monastic Sites

The monastic compounds originated by constructing a mahācetiya and expanded as monasteries by combining monks’ quarters and the mahācetiya. These monastic groups in Nagarjunakonda constitute an intriguing set of architectural remains that attest to the importance of Nagarjunakonda during the age of Ikṣvāku. This coincides with the disappearance of the Sātavāhanas dynasty (ca. 200–250 BCE) in the Deccan (

Kim 2011).

Inscriptions found on āyaka pillars and drum components within the remnants of various sites chronicle the evolutionary expansion and the construction of monuments within Buddhist monastic layouts across different eras. The layout of the monastic quarters and primary structures, including the mahācetiya (great stūpa) and cetiya (apsidal shrine with a smaller stūpa or a Buddha image), along with the detailed study of stone ornamentation at these ruins, was informed by an understanding of how monks and laypeople experienced space during religious ceremonies. This architectural arrangement, which brought together significant structures such as the mahācetiya and cetiya, was designed to mirror the Buddha’s teachings on cause and effect, aiming to enlighten the masses. It sought to create an ideal realm embodying nirvana’s concept of ultimate existence, reflecting the teachings’ objective to guide followers toward enlightenment.

6.1. Investigating the Sites from Excavation Works

6.1.1. Site 1

The mahācetiya (Site 1), with a diameter of 31.3 m, was usually built of solid brick measuring 50 × 25 × 7 cm. The size of the bricks was the same as that used for the apsidal shrines and monastic cells built during the Ikṣvāku period. The drum was raised 1.24 m above ground level, and the total height of the mahāstūpa, excluding the upper portion from the bottom of the harmikā, was expected to be 20 m to 24 m. On top of the drum was a narrow path, 2.1 m wide, extending all around the base of the dome. There were no stairway traces. It was covered with plaster from top to bottom; the dome was decorated with the usual garland ornaments, and a drum with a few simple moldings was also covered with plaster. Stone was not used in this construction; the āyaka pillars reflected a later addition to the mahāstūpa. The mahāstūpa was surrounded by a circumambulation path of 3.9 m in width and enclosed by a wooden railing standing on brick foundations. Thus, the mahācetiya was built on a wheel pattern (8 in the innermost circle and 16 each in the central and outermost circles), comprising a drum encircled by a brick wall and providing enough space for the processional path. The drum had āyaka platforms with āyaka pillars encircled by railings and gateways fenced around the four cardinal sides.

The mahāstūpa received the patronage of the pious lady Chamtasri, the sister of Vasishthiputra Chamtamula, although Reverend Ananda, a monk of the Aparaśaila School, supervised the actual construction. Built in the sixth regnal year of Vīrapuruṣadatta, the wheel-shaped mahāstūpa had a diameter of approximately 27.5 m with platforms with dimensions of 6.7 m in width × 1.5 m in depth, surmounted by

āyaka-pillars at the four cardinal directions. All epigraphs inscribed on the

āyaka-pillars bear an identical date: the 10th day of the 6th rainy season of the 6th regnal year of Vīrapuruṣadatta (

Figure 2).

The mahāstūpa was completed on the first attempt, clarifying that the term “

nava-kamma” in the inscriptions means “new construction”, and Camtisiri built the mahācetiya. It was not reconstructed (

Sarkar 1966, p. 77;

Vogel 1933, p. 30). The Amarāvatī, Ghantasala, and Jaggayyapeta mahāstūpas, based on epigraphical evidence, belong to a period much earlier than the second century CE. They were enlarged, and

āyaka platforms were added to them during the second century CE. If Camtisiri built the mahācetiya, the inscriptions would have informed us how the relics of the teacher were enshrined in the mahāstūpa. According to the

Mahavamsa, “

nithapita” means “completed” (

Vogel 1933, p. 30). Similarly, the

Vinaya Pitaka (Basket of Discipline) defines a “

navakammam” as “a religious edifice” erected by a lay member. If the buildings were intended for the Bhikṣu, a Bhikkhu would be appointed to oversee the construction, ensuring that the structures adhered to the rules of the order regarding their size, form, and intended purpose for the various chambers. Similarly, if the buildings were meant for the Bhikṣuṇī, a Bhikṣuṇī would be appointed to supervise the works with the same considerations (

Vogel 1933, pp. 29–30). The bricks used for the mahācetiya were the same in size as those used for the apsidal temples and monastic cells built during the Ikṣvāku times, such as an apsidal shrine and monastic cells at Site 1, and a monastery with two shrines at Site 3. The relic caskets in the Nagarjunakonda mahāstūpas are similar.

First, only the mahācetiya was built along with the āyaka platforms. The railings on the upper platform of the mahāstūpa were not constructed initially, and the outer railings were made only of wood. Subsequently, the monastery was added to the 15th regnal year for the same king. Later, in the 18th regnal year of the same king, an apsidal stūpa shrine (cetiya) was constructed to support the Aparaśaila sect. Nine years after completing the mahācetiya at Nagarjunakonda, a monastery was immediately built next to it. Three years later, a simple stūpa shrine was added outside the monastic precinct. The entire complex was financed by laypeople, and monks built the entire monastic complex under their patronage. This contributed to the transfer of the giver’s merit to King Vīrapuruṣadatta and the family. This was performed to achieve a posthumous rebirth on well-being and happy lands through rituals.

The deposits of the sariras of the mahāstūpa are denoted by two words in the

āyaka inscriptions. All inscriptions include the sentences, “Supreme Buddha, honored (or absorbed) by the Lord of the gods”, and “the

āyaka pillar has erected this pillar at the Mahācetiya of the Lord” (

Vogel 1933;

Sircar 1966). In these inscriptions, “

dhātuvara parighitasa Mahachetiye” implies that the mahāstūpa is a

Śārīrika (corporeal) stūpa, the Buddh

adhātu “

dhātuvara parighitasa”. The mahācetiya were protected by the corporeal remains of the Buddha. These two inscriptions indicate that the king received a relic of the Buddha and enshrined it in the mahācetiya (

Sastri 1933;

Vogel 1933). This sacred spot gained its significance from its association with the Buddha, a connection fostered through the dissemination of Buddha’s sariras (relics) and the development of Buddhist legends unique to each area.

Regarding the term “

dhātu”, Sircar and Schopen have proposed different definitions. Sircar notes that “

dhātu-vara” essentially refers to the relics of the Buddha. Such mahāstūpas were referred to as “

dhātu-garbha”. However, Schopen, based on Nagarjunakonda inscriptions, argues that the redactor of the inscriptions did not view the

dhātu or relic as a piece or part of the Buddha. Instead, he suggests that the redactor seemed to conceive it as something that contained or enclosed the Buddha himself, something in which the Buddha was wholly present. However, if the Buddha were present in the relic, the relic could not represent a token or reminder of the past and the deceased Buddha, indicating a change in the concept of the Buddha’s nature in Mahāsaṅghika schools (

Schopen 1988). Nagarjunakonda monuments, such as mahācetiyas and cetiyas, indicate incarnations of the living Buddha, a cottage that he lived in during his lifetime, a relic after his death, and a shrine for worshipping him (

Daoshi 668;

Schopen 1988).

6.1.2. Sites 3 and 32 A

Sites 3 and 32 A yielded no datable epigraphs; however, the use of metrical Sanskrit in the epigraph was likely to show that the monastery was not earlier than the 11th regnal year of Ehuvula, which corresponds to the time the inscription of the Sarvadeva Temple was composed (

Longhurst 1938, p. 16). Given that the construction of an image shrine at Site 9 appeared in the 11th regnal year of Ehuvula Caṃtamūla, the period in which the apsidal halls were situated inside the monastery would be much later than the late extension of Site 9. A mahāstūpa at Site 32 A had small

āyaka platforms measuring 1.8 m × 0.35 m, and pillars could not be established on a narrow platform. The layout of the buildings showed a complete complex, such as a refectory, store rooms, and a twofold division of the Vihāra. The dwelling area consists of a four-winged monastery around a central

mandapa with an oblong Buddha shrine located inside it. The remaining part of the monastery is approached through a narrow passage beyond its refectory. Toward the south of the monastery lay a huge open space, though enclosed by walls, which had three chambers, circular externally but square internally, arranged in rows. There was a six-spoked mahāstūpa with

āyaka platforms in the western direction. A six-spoked mahāstūpa was located at Site 30, which was a monastery of only three cells.

Site 3 was as developed in the plan as Site 32 A, with the difference that it had a double cetiya hall, one for a mahāstūpa and the other for an image of Buddha, both located inside the monastery (

Longhurst 1938, pp. 18–20). It also had a refectory, storeroom, and bath. The drain of the bath was connected to an underground soakage pit. The mahāstūpa adopts a typical eight-spoked base. Compared with Site 2, which had the same layout of buildings as Site 3, Site 3 did not have a refectory or bath and a central

mandapa. However, both had two cetiya halls inside the three-winged monastery, overshadowing the main mahāstūpa of the eight-spoked base.

6.1.3. Site 5

In the second regnal year of Ehuvula Caṃtamūla, Site 5 was constructed for the Acharyas of the Bahuśrutīyas sect, an offshoot of Mahāsaṅghika. Mahadevi Bhattideva, wife of Mahārājā Mathariputta siri Virāpurisadata, supported the entire construction of the monastery, which was built by dharma priests of Bahusutiya school. The mahāstūpa had two concentric rings of 8 and 12 spokes, respectively, with a diameter of 7.3 m and 15 m, besides a hub of 1.32 m

2. The core of the mahāstūpa was divided into 20 chambers, 8 inner rings, and 12 outer rings (

Figure 3).

The two cetiya halls do not have Buddha images but enshrine stūpas. The monastic enclosure was one of the largest in Nagarjunakonda, considering the number of cells. The enclosure contained at least 28 cells. Later, at least one square-shaped shrine was built with a decorated pillar in front, simulating a “

dhvaja-stambha”. Four shrines were added within residential quarters for monks in subsequent stages (

Sarkar 1966, p. 78). These chambers might have been meant for acharyas and vinaya teachers, who might have preferred to have separate cells. This was an improvement because the Maha Vihāra at Site 1 did not have chambers.

6.1.4. Sites 7–8

The monastery of the Mahīśāsakas, Site 7–8, situated on a hillock adjacent to Nagarjunakonda hill, was built by Mahadevi Kodabalisiri, the sister of Ehuvula Caṃtamūla and the wife of the Mahārājā of Vanavasaka, in the 11th year of his reign. Kodabalisiri supported the Mahīśāsaka Sect, notionally closer to Sarvāstivāda than the Mahāsaṅghika Sect. It constructed pillars and monasteries for the benefit of the welfare and happiness of all sentient beings in the Mahīśāsaka sect. The inscription mentions who was in charge of the construction. It was performed by the master, the great preacher of the law, and the Thera Dhammaghosa. This monastery has two mahācetiyas without a cetiya hall. One mahāstūpa that produced the relics was lodged in a terracotta casket. In contrast to the new accommodation of the new construction, Sites 7–8 followed the same old style in the form of a hemispherical dome resting on a low drum. The monastery worshipped local images, not Buddha images, as an inscription engraved on the bottom edge of the mithuna (images of men and women) (

Tsukamoto 1996–1998, p. 338).

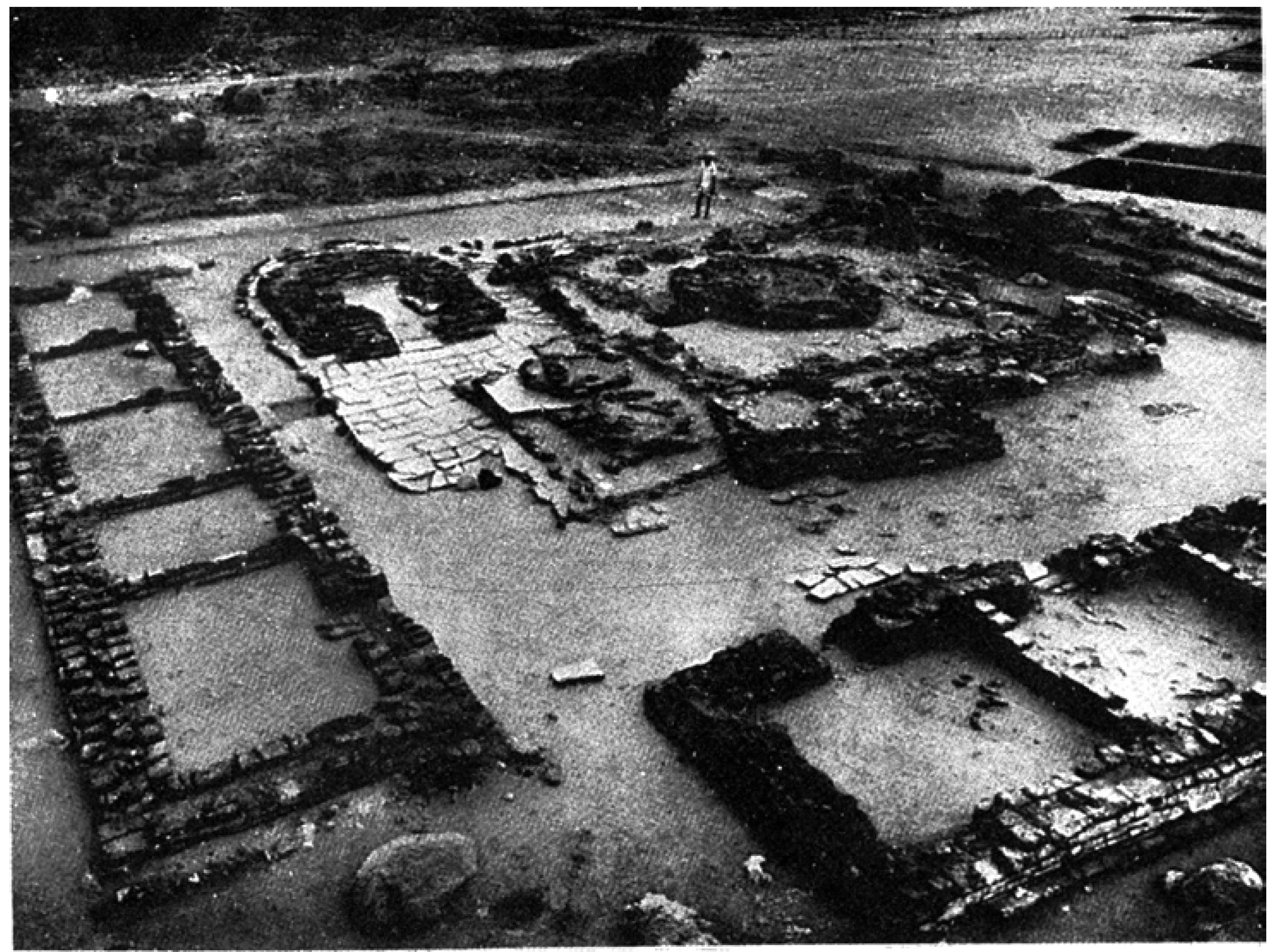

6.1.5. Site 9

Site 9 was completed in the eighth regional year by Ehuvula Chamtamula, the son of Vīrapuruṣadatta (

Sircar 1966, p. 19). If it were true that Site 9 had experienced the same process as Site 1, the monastery would have had four structural phases. While Mahāstūpa Sites 6 and 9 at Nagarjunakonda were decorated with carved marble slabs and coping stones, the mahācetiya at Site 1 seems to have been decorated in a simple style. Sites 9 and 6, successors of Site 1, played crucial roles in the stylistic changes related to the development of the architectural ground plans of the site. The sites began to express profuse decorations on carved panels using the Site 1 ground plan. Site 9 shows a layout in transition toward an ideal ground plan at Nagarjunakonda.

Rubble mahāstūpas belong to the earliest phase, built on earth-fast poles. The mahāstūpa, comparable to the mahāstūpa in Site 5 and Site 1, had two concentric circles with 7.3 m and 12.7 m diameters and 8 and 16 spokes, respectively. There was at least a 30-year time difference between the completion of this monastery and the establishment of the site. The monastic unit as a whole was similar to that at Site 1, except that two small votive stūpas were set up in front of the cetiya shrine, which contained a mahāstūpa. Faced with this, another cetiya shrine that included a standing Buddha image was added in one of the later phases of the construction. This implies that the shrine was constructed to accommodate Buddha’s image. Site 9 did not yield Buddha images in its early stages, as the original sect living at Site 1 did not accept the idea of image worship until the fourth phase. A few figures appeared in the long panels of āyaka platforms: the figures as reliefs of the conversion of the yakṣa Āṭavaka and scenes from Mandhātu Jātaka. The figures of the standing Buddha appeared inside an apsidal shrine in the 11th regnal year of Ehuvula Chamtamula. The second cetiya was constructed to enshrine a standing image, in response to the first cetiya with a smaller stūpa that had probably been built three years ago. This implies that the construction of the two cetiya halls may have been closely related to the occurrence of the Buddha image. Another long panel that portrayed mithuna figures and scenes from Buddha’s life appeared at Site 106 in the 24th regnal year of Ehuvula Caṃtamūla. The Buddha image in Andhra Pradesh appeared in a narrative context at Amarāvatī over a century earlier than the standing Buddha image of Nagarjunakonda. The Buddhist sculptures of Amarāvatī rested on narrative scenes containing figures of Buddha, which influenced the forms of standing Buddhas and independent Buddhas in the āyaka panels at Nagarjunakonda, Jaggayyapeta, and Amarāvatī.

Site 9 inscriptions revealed that the mahāstūpa was dedicated by Chamdisiri, who had transferred several benefits to prominent townships in connection with festivals celebrated in honor of the Buddha, the

dharma, and the

sangha. In return for her donations, Site 9 was constructed with the intention of obtaining nirvana (

Figure 4).

6.1.6. Site 38

The MahaVihāra-vadin, belonging to the Sthavira sect or a Theravadin sect from Ceylon, adopted the practice of building a cetiya hall, as seen in Sites 1 and 6 of Aparaśaila. Site 38 featured both a mahāstūpa and an apsidal shrine situated within a residential enclosure with four wings. The mahāstūpa was made of solid bricks instead of a wheel-shaped pattern with

āyaka platforms. The construction of the main mahāstūpa followed the design principles observed at Site 43, which had a brick without any

āyaka platform or wheel-shaped plan. Similarly, the mahāstūpas at both sites were relatively small in size. Unlike Aparaśaila (Sites 1, 6, and 9), Bahuśrutīya (Sites 5 and 26), or Mahīśāsakas (Sites 7–8), they did not place much emphasis on the main mahāstūpa. Specifically, the Aparaśaila mahāstūpas in the three sites had diameters of 27.7 m, 15.2 m, and 18.3 m, respectively, while the Mahīśāsaka mahāstūpa in Site 7 had a diameter of 12.2 m (

Figure 1,

Figure 5, and

Figure 6).

The style of writing in the Brahmi inscriptions excavated in the monastic quarters was similar to that of the Vīrapuruṣadatta period when compared to the other Brahmi inscriptions. However, based on archaeological findings, the cetiya hall was added inside the monks’ quarters at a later stage. It did not have traces of enshrining a mahāstūpa (

Sarkar 1966, p. 78), and the cetiya hall was built during the regnal era of King Ehuvula Caṃtamūla, dated to the late third century CE. Two votive stūpas emerged around the main mahāstūpa during the third structural phase of the monastery. The existence of a brick mandapa that is apsidal in shape suggests that an image may have been installed in the shrine. Compared to Site 38, Site 43 lacked votive stūpas but featured an apsidal stūpa shrine, positioned between the stūpa and monastic quarters, with four wings. On the other hand, Site 38 had votive stūpas but no apsidal stūpa shrine outside its monastic quarters, unlike Site 43, making their layouts distinct. Determining if the monastery belonged to the Sthavira sect is difficult since neither site’s stūpas had spokes for dividing chambers or

āyaka pillars in the four cardinal directions. However, Ceylonese monks cohabited with monks from other sects, like Aparaśaila or Pūrvaśaila, in Site 43’s monastic compound (

Figure 6).

6.1.7. Site 43

Site 43 comprises a monastery, cetiya hall, and mahāstūpa and is situated on the Chula-Dhamma-giri attributed to the Theravadin monks of Ceylon. In the 14th regnal year of Vīrapuruṣadatta, a female lay worshipper from Govagama, Bodhisri, built a cetiya hall that enshrined a smaller stūpa. The main mahāstūpa at the site had a brick circular rim and a solid rubble core without spokes or

āyaka platforms. As no tiles were found in the debris, the wooden roof over the cells was covered with thatch and identified as a

sala building type with a leaf-thatched roof (

Longhurst 1938). The walls were made of brick and plaster, with traces of a few plain moldings discovered along the plinth of the cells, indicating that the ornamentation was made of plaster. Several small lead coins, dated to approximately the second century CE, were found in one of the cells of this monastery. The monastery did not initially suggest the idea of Buddha worship. However, a small, broken limestone image of a Buddha was discovered at this site. Later, the image was introduced into the monastery when an oblong shrine with a pedestal was added inside a four-winged enclosure (

Longhurst 1938) (

Figure 7).

6.1.8. Others

Site 4 consisted of two apsidal shrines facing each other in the courtyard, a central hall (mandapa), a row of cells, and a mahāstūpa outside the monastic cells. In one of these temples, two broken statues of Buddha were discovered, but nothing was discovered in the other. The images are standing figures, and the larger statue is approximately 2.43 m high. An entrance on the east side led to a second open courtyard containing a long building near the eastern wall. The building was a refectory, and on the opposite side of the entrance was a long stone bench. On the south side were two cells, or storerooms, a kitchen, and a small lavatory in the northern corner of the enclosure wall. All buildings were roofless. The two apsidal temples had barrel-vaulted roofs for brick construction, whereas the remaining buildings had wooden roofs covered with thatches. The pillars of the central hall were made of stone, and its floor was made of the same material (

Longhurst 1938).

Site 24 contains a dated inscription. It was constructed in the 11th regnal year of King Rudra-Purushadatta. Architecturally, an eight-spoked mahāstūpa was constructed on a square platform flanked by two apsidal shrines, one for the mahāstūpa and the other circular externally but oblong internally, for an image. It revealed two new discoveries: the circular image shrine, located within a four-winged monastery, and a memorial pillar placed opposite a stūpa-cetiya raised in honor of the king’s mother.

6.2. Mahāsaṅghika School in Nagarjunakonda

Upon his return from Varanasi (commonly known as Benares or Banaras), Faxian (fifth century CE) discovered a monastery in Pataliputra where the Mahāsaṅghika resided. He then found a copy of the Vinaya, which contained the rules of Mahāsaṅghika, in the monastery. The original copy was handed down to Jetavana Monastery. Faxian confirmed that this copy was the most complete, with the fullest explanations. Additionally, he received a transcript of the rules in six or seven thousand gathas, which were Sarvāstivāda rules. These rules had been transmitted orally from master to master without being committed to writing. The early monastic codes of both schools were observed during the Qin dynasty of the Sixteen Kingdoms (ca. 351–431 CE).

In his seventh-century work “Datang-Xiyuji” (Records of the Western Regions of the Great Tang Dynasty), Xuanzang noted that the Mahāsaṅghika sect was widespread in Udyana, Pataliputra, Dhanakataka, and Andarab (the former territory of Tukhara). Similarly, around 671–695 CE, Yijing observed that the Mahāsaṅghika were primarily located in Magadha, with some presence in Lata and Sindhu (Western India), and scattered throughout northern, eastern, and southern India. In Udyana’s monasteries, monks devoted themselves to studying Mahāyāna teachings, engaging in silent meditation, and proficiently reciting their texts and chants. The monastic community recognized five Vinaya traditions: Dharmaguptaka, Mahīśāsaka, Kasyapiya, Sarvāstivāda, and Mahāsaṅghika.

Datang-Xiyu-Ji discussed the prevalent schools of Buddhism in Dhanakataka and its neighborhood during his visit to Andhra Pradesh. At that time, there were 20 existing monasteries housing monks from the Mahāsaṅghika School. On a hill to the east of Dhanakataka, there was Pūrvaśaila (East Mount) Monastery, and on a hill to the west, there was Aparaśaila Monastery (West Mountain). However, the inscriptions discovered in this locality do not mention the name Mahāsaṅghika (

Tsukamoto 1986, pp. 454–69). The names of the schools suggest that they were local schools, and most of them were classified as branches of the Mahāsaṅghika rather than the Mahīśāsaka. This implies that Mahāsaṅghika School was divided into various sects, probably after the Sātavāhanas Kingdom (

Dutt 1931, pp. 633–53). During the Sātavāhanas period, donors engraved the name Mahāsaṅghika School for their offerings in inscriptions, such as “pavajitāna bhikhuna nikāyasa Mahāsaghiyāna” (Mahāsaṅghika assembly of renunciant monks).

The Mahīśāsaka is a branch of the Sthaviravāda, not of the Mahāsaṅghika. Xuanzang mentioned that the Sthavira School was regarded as one of the sects of the Mahāyāna School. He called the Sthavira School the Mahāyāna Sthavira Schools. Additionally,

Stone (

1994) believed that all sects, except Mahīśāsaka, gradually incorporated both mahāstūpa and image worship into their precincts based on the layout of the monasteries. Conversely, the Mahīśāsaka School worshipped images such as mithunas, who were venerated as bodhisattvas in early Mahāyāna schools and gradually changed into Buddha images (

Myer 1986;

Rhi 1994). Although Buddha’s images have not been excavated, the Mahīśāsakas never objected to image worship. Sarvāstivāda and Mahāsaṅghika

vinayas state that a strict distinction must be maintained between properties and objects that belong to the monastic order and those that belong to the mahāstūpa (

Zhan 2006, pp. 186–88). This shows that there were commonalities between Mahīśāsaka and Mahāsaṅghika, as well as the Sarvāstivāda School.

Thus, all the sects mentioned in these Nagarjunakonda inscriptions are considered branches or sub-branches of Mahāsaṅghika. The basic notions of the Mahāsaṅghikas, including the Mahīśāsaka and Caityaka, must be discussed to understand the construction of the Nagarjunakonda monastic complexes. The Mahāsaṅghika focused on the worship of the mahāstūpa, or caitya, according to the

Mahāvastu. A notable point is that the Aparaśaila and Pūrvaśaila were independent sects because Xuanzang mentioned that the two sects were not different, although the commentary on the

Kathāvatthu states that there were differences of view between the Aparaśaila and Pūrvaśaila with regard to doctrine and psychological analysis (

Table 1).

Mahāsaṅghika school monasteries in Nagarjunakonda were universally composed of a mahācetiya (mahāstūpa), two apsidal

cetiyas (

caityas), and a community hall surrounded by

Vihāras (cells that monks stayed in) in the standard quadrangle arrangement, the last step of the long process of mutation. Inscriptions from other sects, such as the Rajagirikas, Mahāsaṅghika, Mahīśāsakas, and Uttarasailyas, appeared at a later period, making it unlikely for them to have been present during Nagarjuna’s time (

Solomon et al. 1999, pp. 167–69;

Walser 2005, p. 87). The mahāstūpas follow the renowned Andhra Pradesh conventions and consist of a dome resting on a round drum, adding four platforms (

āyaka) on each of the four axes, and standing on the platforms in a row of five pillars referred to as

āyaka skambhaḥ in the inscriptions. This mode of stūpa construction is mentioned in

Mohesengzhilu. It recorded the method of constructing a votive stūpa for the monk Kaśyapa. The Buddha was said to have raised a stūpa for the Kaśyapa Buddha. Its bottom platform was enclosed by railings on four sides; two tiers were raised in a cylindrical form with four square-shaped projections. The top of the dome has a spire with disks. Additionally, it was one

yojana (i.e., several miles) high and half

yojana broad. The railings were made of bronze. It was completed in seven years, seven months, and seven days. The stūpa that King Krki erected for the Buddha had niches on all four sides. Upon it were figures of lions, elephants, and various kinds of paintings (

Buddhabhadra n.d.b.). This comprehensive architectural and cultural narrative of Nagarjunakonda’s Mahāsaṅghika monasteries not only showcases the complex development of Buddhist monastic architecture but also reflects the diverse religious practices and sects that coexisted within these sacred spaces, thereby highlighting the intricate interplay between religion, art, and society in ancient India.

7. Major Characteristics in Architectural Composition

7.1. Combination of Mahācetiya and Two Cetiyas

The monasteries withstood the tide of image worship as a consequence of temple construction, gradually drifting more toward Mahayanic ideals. In the third century CE, an important feature was the construction of double shrines. The provision of double shrines in a single monastery—one enshrining a stūpa and the other a Buddha image—was seen nowhere else in India. The shrines stood adjacent to each other. The worshipper was free to offer worship according to his inclination, either to the stūpa or the image (

Dutt 1962, pp. 126–32). Archaeological evidence shows that in the third century CE, a horizontal attitude toward understanding the Buddha’s life and taking care of rituals, with both forms of worship being recognized and the choice between them, was left to the worshipper. The evidence comes from the Nagarjunakonda monasteries and West Indian cave monasteries. The emergence of the combination of a stūpa and a cetiya hall affected the first change in the traditional setup. It implies fundamental changes into a sacred place or an honorific abode in which the living Buddha resided for pilgrimages and worshipped at a simple tomb for Buddha’s memorialization.

The emergence of Buddhist paintings, statues, and engravings reflected an innovative change. This led to the creation of temples serving as both cetiyas and mahāstūpas. The combination of mahāstūpas with cetiyas was applied to the law of causation, revealing a grave process from enlightenment to nirvana in Buddha’s biographies, which formed a new tradition. These holy places, found in cave temples like Ajanta and Ellora, served as didactic devices reminding devotees of the Buddha’s life. Combining mahāstūpas with Buddha images allowed for integrated worship. The emergence of Buddhist paintings, statues, and engravings reflected an innovative change. This led to the creation of temples serving as both cetiyas and mahāstūpas. The combination of these structures symbolized the journey from enlightenment to nirvana in Buddha’s biographies, forming a new tradition.

Consequently, the construction of mahāstūpas with two cetiyas constituted a significant activity for devotees to accumulate merit and secure posthumous rebirth into the well-being land through accrued benefits. The combination of the two monuments marked a pivotal moment in the historical process of Buddhist monasteries. The fusion of mahācetiya (mahāstūpa) and cetiyas had already manifested in scenes arranging the mahāstūpa, cetiya, tree shrine (railed Caityavṛkṣa), and

harmikā (meaning a chamber for bones) along a straight line, discovered on the bas-reliefs of Kanaganahalli in the first century CE at Amarāvatī, Nagarjunakonda, and Jaggayyapeta in the third century CE (

Huntington 1990,

1992;

Rotman 2009). The mahāstūpas treated votive materials in 4–12-spoked chambers. This implies that the mahāstūpa and apsidal halls subsumed varied meanings, serving as tombs and Buddha shrines for worship, akin to temples. This duality emphasizes their inherent significance as tombs.

7.2. Quadrangles and Wheel-Shaped Structures

Initially, the Nagarjunakonda establishments primarily consisted of mahāstūpas, cetiya shrines (with images or a stūpa), and monastic cells, the so-called Vihāra, of monks. Nagarjunakonda compounds introduced a layout of the quadrangular monastery, square or oblong image-shrine, pillared hall for congregational purposes, miniature stūpas, and a square platform for the mahāstūpa. In the Gandhāra sites in the northwest, such innovations had already occurred prior to Nagarjunakonda’s plans.

A revolutionary change in the mode of mahāstūpa construction was to create a wheel-shaped structure, particularly in the Aparamahāvinasaliya and Bahuśrutīyas sects. The wheel-shaped plan provided a new improvement over earlier building traditions and a successful attempt at transforming an idea to create chambers to deposit bones, sariras, votives, and offerings. Regarding the constructional advantage of wheel-shaped mahāstūpas in small structures where sinking of the foundations and consequent fracture of the masonry are unlikely to occur, earthen packing may be perfectly safe. Conversely, in large domes, any sinking of the wall might cause cracks that admit moisture, when the expansion and contraction of the material are certain to cause the destruction of the dome” (

Sarkar 1966, p. 90). Mahāstūpas with a solid core, particularly in the Mahīśāsaka and Sthavira sects, made of either brick or stone, existed as wheel-shaped ones with spokes varying from 4, 6, 8, and 10. However, Mahīśāsaka simultaneously adopted the techniques of a wheel-shaped structure at Site 7. This implies that the eight-spoked adoption depends on the size of the mahāstūpa, which has a diameter of 9–12 m, comparable to Sites 3, 5, and 9. Moreover, the Aparamahāvinaśaila school, which was the only school in Nagarjunakonda whose stūpas covered with narrative reliefs, was notably focused on narrative depictions. This set apart from other groups cited in the inscriptions at Nagarjunakonda, such as the Theravādins, Mahīśāsakas, and Bahuśrutīyas, who did not share this interest (

Skilling 2017). Aparamahāvinaśaila, which probably played a crucial role in the Buddhist art of ancient Āndhradeśa, was not the only school involved in the creation of reliefs illustrating Buddhist narratives. This school, along with the Kaurukulla school, was also operative in Amaravati, where both were recognized for their contributions to this form of narrative expression of Buddha’s life (

Zin 2010;

Baums et al. 2016).

The wheel-shaped plan is not limited to Andhra Province. This plan has already been implemented in Gandhāra and northern India. The Dharmarajika mahāstūpas at Taxila and Sirkap were irregularly wheel-shaped. Mathurā and Shah-ji-ki-Dheri constructed wheel-shaped mahāstūpas in Peshawar. The mahāstūpas with Taxila and Mathurā were chronologically anterior to the earliest mahāstūpa at Nagarjunakonda, such as those at Sites 1 and 6. The Bhattiprolu mahāstūpa belonged to a wheel-shaped structure, probably under the adoption of the Gandhāra technique or a revival of the constructional device for the base, as seen in Piprahwa and the imitation of the structure of Roman tombs. The Bhattiprolu mahāstūpa does not contain

āyaka platforms. This implies that the

āyaka pillars were later added to mahāstūpas in southern India (

Kuwayama 1998, pp. 506–66) (

Table 2).

7.3. Āyaka Platforms

This notable construction of mahāstūpa architecture involves the use of

āyaka platforms in the four cardinal directions. Each platform was surmounted with either five inscribed or non-inscribed pillars. The

āyaka pillars are established to support the form of Buddhist symbols, four of them featuring

trisula ornaments and the fifth, or center pillar, with a miniature stūpa symbolizing Buddha’s death. Each pillar symbolizes one of the five crucial episodes of Buddha’s life: Birth, Great Renunciation, Enlightenment, First Sermon, and Extinction (Nirvana). These pillars do not bear capital or engraved symbols (

Longhurst 1938, p. 14).

The term “

āyaka” originates from the concept of “respected”.

Āyaka platforms, positioned at the four cardinal directions, featured five

āyaka pillars representing the five Buddhas, and served as sites for prayers (

Agrawala 2003). The Caityakas, responsible for erecting the mahāstūpa (mahācetiya), embraced the notion of the five Buddhas, regarding them as the five pillars, with the central pillar symbolizing the Buddha (

Sarao and Long 2017). Stemming from the Mahāsaṅghika School, the Caityas constructed mahācetiyas for worship. Inscriptions on the

āyaka platforms at the Amarāvatī mahāstūpa mention various sects, including one documenting the offering of a

dharmacakara (wheel of dharma) to support the Nikāya of the Caityakas (

Archeological Survey of India 1918). The presence of

āyaka pillars was associated with the worship of votive stūpas, which were placed atop the pillars. These mahāstūpas and shrines on the pillars symbolize sacred sites linked to the life of the Buddha (

Figure 1).

The absence of

toranas (gates) and railings on the mahāstūpas’ foundation platform of, along with the addition of the four

āyaka platforms at the openings on the four cardinal points, represented new developments. The construction of

āyaka platforms preceded the introduction of Buddha images. Nevertheless, the symbols of the

āyaka pillars persisted at the pinnacle of the pillars even after the introduction of icons, although other symbols were replaced by icons. Thus, this combination of symbols and icons continued to represent sacred sites in the biography of Buddha (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

8. Situating the Well-Being and Happiness Land in Nagarjunakonda

The practices of constructing miniature stūpas, mahāstūpas with spoked bases, and oblong shrines, circular externally but square internally, within a monastic place (e.g., Sites 4, 9, 24, and 106) were also prevalent in the later Ikṣvāku times of King Rudra-purushadatta. However, they were not universally accepted by the monastic communities.

The presence of votive stūpas near larger mahāstūpas and cetiyas at Buddhist sites was a manifestation of the devout hope that passing away in the proximity of the Buddha would facilitate rebirth in a Buddhist paradise, a concept supported by the works of

Schopen (

1997, pp. 124–25),

Casal (

1959, p. 143), and

Hakeda (

1965, p. 60). This phenomenon is evident in the layouts of sacred sites such as Taxila, including Dharmarajika (first century BCE); Jaulian, Sanchi (first century); Bharhut, Bodh Gaya; and Nagarjunakonda (fourth century), where the main mahāstūpa was often encircled by numerous smaller stūpas. Marshall and Schopen observed at the Dharmarajika site that the main mahāstūpa became encircled by smaller stūpas due to their haphazard placement (

Marshall 1975, p. 235), indicating that these miniature stūpas were likely not part of the original design (

Schopen 1997, p. 134). These historical sites, reflecting ancient literary traditions, suggest the belief that the Buddha was physically present at certain locations. The primary structures, such as mahāstūpas and cetiyas, at these sacred sites were seen as containing or symbolizing the living presence of the Buddha, attracting secondary mortuary offerings. This ancient literary tradition also posited that dying in the presence of Buddha led to rebirth in heaven. Thus, the structures symbolized the continued, living presence of Buddha within the Buddhist community (

Schopen 1997, p. 135).

In Jaulian, another site contained smaller stūpas near the central mahāstūpa on an oblong plinth. Contrary to the Dharmarajika site, which was overwhelmed by successive layers of buildings, the smaller stūpas at the Jaulian site spilled down to a lower level when space ran out (

Marshall 1951, pp. 368–38). The Sanchi site included a multitude of stūpas around the Great Mahāstūpa, most of which were swept away during the restoration of 1881–1883 (

Marshall 1918, pp. 87–88). Votive stūpas at other Buddhist sites, such as Bhaja and Kanheri in the Deccan, featured stone votive stūpas. These had been earlier recorded at the Buddhist site of Bhaja in the Deccan, with bricks being known mainly from Kanheri (

Ray 1994, p. 40;

Gokhale 1991, pp. 111–36). At Bodh Gaya, the numerous successive monuments around the Bodh Gaya temple indicate that “the general level of the courtyard was gradually raised and the later stūpas were built over the tops of the earlier ones in successive tiers of different ages” (

Cunningham 1998, pp. 46–49). The votive stūpas at Bodh Gaya were the pinnacles of tall medieval stūpas, and almost all stūpas had no pinnacles or finials, the shapes of which were comparable to the excavations at the site of Ratnagiri in Orissa. They revealed votive stūpas similar to those found in Bodh Gaya. Yijing recorded that monks in India built things like stūpas for the dead, containing his sarira, the so-called

kula. These were small stūpas without a cupola (

Yijing 1896, p. 82). Votive stūpas sometimes had inscribed texts in their smaller chambers (

Mitra 1960, pp. 31–32), and these texts reflected funerary features (

Schopen 1997). Thus, it is possible that the sockets of the stūpas were intended for ash or bone, and later,

dhāraṇī and

gathas (hymns) might have been added if the miniature stūpas had been created for funerary purposes.

In the excavation of the Nagarjunakonda Buddhist site, relics were consistently placed not at the center of the mahāstūpas, but in one of the chambers, typically on the north side as shown at Sites 1, 8, and 3. At Site 1, a tiny bone relic was housed in a small gold reliquary, which was then placed in a second gold reliquary shaped like a miniature stūpa. Similarly, at Mahāstūpa 3, relics in the form of a small round silver casket placed in small earthenware were discovered. At Site 9, another mahāstūpa with no reliquaries or caskets, burnt bones of oxen, deer, and hares were found on the chamber floor, while two red earthenware water pots and two food bowls were placed in an opposite chamber (

Longhurst 1938, pp. 23–24).

Additionally, remains of peafowls, hares, and rats were found at other sites in Nagarjunakonda. These animals may have been regarded as sacred and used in sacrificial rituals before their cremation. The deposition of animal bones at the mahāstūpas may have been relevant to the Nirmāṇakāya (response bodies) of bodhisattvas, as described in the Jātaka stories. This practice of including ashes, bones, and other items in the mahāstūpas reflects a burial tradition wherein individuals wished to be interred near revered figures like the Buddha or esteemed monks. These practices have roots in the megalithic traditions of the pre-Buddhist era, which were prevalent in places like Amarāvatī, Nagarjunakonda, and Guntupalle in Andhra’s Krishna River Valley. Most megaliths did not produce full human remains but contained only a few bones of the deceased. Over time, in the late third century, newer sites like Sites 9, 106, and 38 began incorporating votive stūpas around main mahāstūpas and within courtyards, following the older tradition of chambers within the spoked structure of mahāstūpas.

This resulted in successive waves of mortuary deposits covering a vast area. Graves around the tomb of Kobo Daishi Kukai (ca. 774–835) contained not only complete bodies or ashes but also bones, hair, or even a tooth. The interment of Buddha’s symbol aimed to facilitate rebirth in a well-being paradise, analogous to Sukhāvatī (well-being and happiness) (

Schopen 1997, p. 123;

Casal 1959;

Hakeda 1965). Configurations found in Bodh Gaya, Sanchi, Banaras, and Nagarjunakonda were influenced by these heavenly concepts (

Schopen 1997, p. 125).

9. Conclusions: Embodying Buddha’s Life on the Well-Being and Happiness Land with a Universal Rule

The universalized ideas that embodied Buddha’s life succeeded in early design ideas for constructing Buddhist temples, combining a mahāstūpa with a cetiya (and twin cetiyas), five āyaka pillars, and āyaka platforms adorned with carved ornaments at the four cardinal directions. The symbolic icons serve as reminders of Buddha’s sacred places in his biography and the well-being lands following his death. Sites 1 and 9 exemplify an early representative type of the development of the Nagarjunakonda site layout. The most developed monastic complex among these sites consisted of a mahāstūpa with āyaka pillars and a quadrangular monastery enclosing a pillared hall. The mahāstūpas at these sites included platforms at the four cardinal directions and spokes for chambers within, surmounted on a square platform. The āyaka platforms include long stone beams serving as cornice stones on the ornate platforms. The mahāstūpas at these sites were flanked by two apsidal shrines, one for an image and the other for a stūpa.

The appearance of the combination of a mahāstūpa, two cetiyas, and a monastic quarter in Nagarjunakonda compounds was significant at three points.

First, the amalgamation of mahāstūpas/mahācaityas/mahācetiyas with stupas/caityas/cetiyas represented an embodiment of the Buddha himself, serving as his earthly abode, relics, and shrines, which, in turn, serve as symbolically significant places in Buddha’s biography, representing scenes of meditation, enlightenment, teaching, and nirvana. These combined structures of mahācetiyas with cetiyas were erected by devotees as a universalization principle based on the law of narrative causation to show their deep reverence for the Buddha. Nagarjunakonda, along with other Buddhist sites in India such as Thotlakonda, Bavikonda, and Salihundam, though not directly linked to places in Buddha’s biography (

Ray 2009, pp. 14–19), prominently featured cetiyas/caityas and mahāstūpa/mahācetiyas indicating incarnations of the living Buddha. These structures encompassed the great departure, meditation, enlightenment, a cottage for preaching during his lifetime, a relic representing nirvana after his death, and a shrine for worship, drawing inspiration from the narratives of Buddha’s life (

Schopen 1988). Furthermore, the construction and combination of mahāstūpas with caityas were active endeavors aimed at accumulating merit to achieve rebirth in the well-being and happiness. This illustrates that these structures were viewed as a means to an end. Additionally, they expanded their definition to encompass sacred places for pilgrims, serving as reminders of essential Buddhist activities such as teaching, nirvana, and meditation (

Schopen 1988).

Second, such a combination implies the possibility of simultaneously performing two different forms of worship: the stūpa and image. In Nagarjunakonda, one enshrines a standing Buddha image that reminds us of the sacred places where Buddha worked on positive lines after the Enlightenment, and the other enshrines a mahāstūpa that reminds us of Buddha’s death (parinirvana) and the sacred place of Kushinagara. Nagarjunakonda Site 38, constructed in the late Ikṣvāku era, has a mahāstūpa layout in a central courtyard surrounded by cell rows.

Third, independent Buddha images began to be carved on the drum and āyaka platforms of the mahāstūpas at Site 9, and later at Sites 2 and 3. The independent images of the reliefs and the arrangements of the reliefs along the drum of the mahāstūpa reflect the notion of multiple Buddhas that appeared in the Mahāsaṅghika School. Humanized images that incarnate multiple Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and heavenly deities are regarded as Nirmāṇakāya and Saṃbhogakāya. Mahāsaṅghika and Mahāyāna Buddhists believed that numerous thrice-a-thousand world systems existed simultaneously in other worlds. Thus, they could admit the existence of several simultaneous Buddhas in different “thrice-a-thousand world systems”.

Fourth, the five

āyaka pillars installed on