Abstract

The archetypal symbols of Mazu’s statues and pictorial art are the mapping of a religious concept, a way of belief, and some programmed behaviours and rituals. They are also emotional imagery used to arouse the cultural awareness of international Chinese, inspire them to help and trust each other, to encourage and to comfort each other, to share weal and woe, and to always forge ahead. From the perspectives of historical memory, visual signs, and cultural identity, this paper explores the construction of archetypal symbols for the statues and images of Mazu. In addition, this paper generalizes the foundation and methods of this construction by analyzing the artistic forms and characteristics of the surviving Mazu images and statues and comparing the rules and regulations for making statues of other religions. Moreover, we consider the function of artistic signs that refer to and symbolize broader religious concepts and beliefs. The purpose of this work is to make the image of Mazu more visually present and strengthen cultural identity.

1. Introduction

Mazu (“Honourable Mother”) is a goddess of the sea whose ritual tradition can be traced to Meizhou Island off the coast of Putian district, sixty miles south of Fuzhou (Dean 1993). She is a goddess who protects seafarers, who grew in popularity from at least the tenth century. In addition to her characteristics of protecting boats, fishermen, and sailors, she also has universal mother goddess representations (especially of concern to women and children). Eventually (during the Qing), she achieved the imperial status of “Empress of Heaven” and her cult rivals other major goddesses, such as the Guanyin. Mazu’s artistic images become archetypal for a variety of sea and mother goddesses with whom she became associated over the course of her cult’s development and spread. Her scriptures can be found in the Daoist Cannon, local ritual manuals, temple gazetteers, historical records, scripts, and novels during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and she became an important part of the official imperial cult during the Qing (Dean 1993). She appeared as an important representation among regional folk traditions, Buddhists, Daoists, and Neo-Confucians, and, at a certain point in her history, became an international goddess for populations throughout Asia and around the world, especially where peoples from Fujian and nearby areas travelled and settled. As a deity commonly venerated in Fujian, Taiwan, coastal areas of the mainland, and throughout Southeast Asia, Mazu can now be said to have spread among most of the world’s Chinese populations. There are approximately 5000 Mazu temples in 27 countries or regions worldwide (see Table 1) and around 200 million worshipers, according to the preface of Volume 1 of Mazu Temples Worldwide (Shijie Mazu daquan). In addition, there are numerous images and statues of Mazu worshiped both officially and in people’s everyday lives.

Table 1.

Countries and areas where Mazu temples have been built.

Beliefs and practices focusing on Mazu can be traced to at least the Song Dynasty (960–1271 CE) and have continued for more than a thousand years. The forms of Mazu statues and images developed throughout this period. Some of these images follow a pattern common to other Chinese folk deities. Others represent more formal models and forms that were influenced by a variety of different dynasties, regional styles, or themes in Buddhist or Daoist artistic conventions. Because of the wide spread of her traditions, Mazu penetrated different cultures and eras. During this period, the cult and its images integrated and developed a variety of local forms.

Since artisans had multiple interpretations of Mazu as a deity, they used different methods to create changeable and diverse Mazu images and statues. Although the deity Mazu and her life story are so familiar that they have been worshipped by people from all social classes—fishermen, farmers, or merchants—the believers visualize her in diverse forms. Commonly, when people distinguish Mazu from other deities, they mostly base their judgments on the sacrifices and animals associated with Mazu, rather than in response to artistic representations of Mazu’s physical features. The ambiguity of Mazu’s specific image has led to general confusion in the impressions and perceptions of the believers. This paper analyzes and summarizes the forms and characteristics of the surviving images and statues of Mazu and discusses the construction of archetypal symbols for these statues and images. The aim is to help understand and describe the visual presence of Mazu, to preserve her images and statues as objects of tangible cultural heritage, and to safeguard Mazu belief and customs as intangible components of cultural heritage. Some religious traditions—such as those of Confucius, Buddha, or the Daoists—developed specific artistic guides for constructing artistic images. There is not a universal or authoritative artistic guide for constructing Mazu statues or making artistic representations of her.

2. Mazu’s Representations

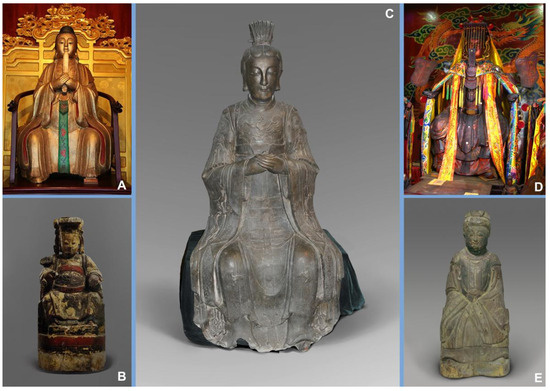

Starting from the Song Dynasty, the belief in Mazu has witnessed substantial development during the Yuan (1271–1368), Ming (1368–1644), and Qing (1636–1912) Dynasties up to modern times, and has gradually become an important cultural image in coastal China and international Chinese communities. During its thousand-year evolution, Mazu’s image has varied from time to time and place to place (Figure 1). According to the historical records of the Song and Qing Dynasties, Mazu had multiple identities and images.

Figure 1.

The image of Mazu in different places since the Ming and Qing Dynasties ((A). Bronze Statue of Mazu in Xianying Palace, Temple Island. (B). The painted wooden statue of Mazu in the early Qing Dynasty in the Tianhou Palace, Lukang, Taiwan. (C). The bronze statue of Mazu in the Ming Dynasty collected by Nantong Museum. (D). Hard-bodied Mazu statue at Kaiji Tianhou Temple, Tainan City, Taiwan. (E). Carved wooden statue of Mazu in Zhenlan Temple, Dajia, Taiwan). Source: Photographed by the authors.

Earliest references to Mazu describe her as a young woman from a fishing village. The historical records of the Song Dynasty state that during her lifetime, Mazu was a young woman who could foretell fortune and misfortune and had some superhuman powers. In this context she is referred to as a shaman or sorceress. Legendary accounts describe her healing the sick, exorcizing demons, averting disasters, and summoning rain.1 Other legendary accounts connect her with Buddhist and Daoist traditions. For example, in some places she is said to have been a worshipper of Guanyin. In others, she meets Daoist immortals and Buddhist monks or Bodhisattvas. For example, an essay titled The Reconstruction of Shengdun Temple (Shengdun zumiao chongjian shunjimiaoji)—included in The Pedigree of Li Clan in Baitang (Baitang lishi zupu) and revised in the 16th year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign (1721)—is regarded by many scholars as the earliest literature about the origins of the belief in Mazu. The essay was written by Liao Pengfei (date unknown) in 1150 in the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279), in the text, the Zhongbu: “there was a goddess named Lin from Meizhou island who is mighty with superhuman power. She served as a sorceress who could foretell fortune and misfortune for people, and people living on the island built a temple for her after she died” (Jiang 1990a). “Goddess Lin from Meizhou [island] was born with superhuman power and could tell people’s good or ill luck, and the people built temples for her after she died,” wrote Li Junfu (the Southern Song Dynasty) in Volume 7 (titled Guibing zuoguo shennv hushi) of Historical Records of Puyang (Puyang bishi) (Ruan 1988). Other historical materials in the Song Dynasty, including Shunji Goddess Temple (Shunji shengfeimiaoji), Madame Linghui Temple (Linhuifei miaoji), A Poet on Baihu Temple (Baihumiaoshi), and The Temple for Three Goddesses (Sanfeimiao) (Volume 3 of Xianxi Annals (Xianxizhi)), not only recorded the birthplace of Mazu but also depicted her as a shaman with the power of fortunetelling.

As Mazu’s fame and influence grew, some historical sources referred to her as the daughter of a prominent local family. This represents the second “image” or representation of Mazu that comes to influence attitudes about her and images depicting her. Historically speaking, connecting her to a family of high social status is a conventional development, wherein a variety of folk heroes and legendary characters are associated with families of higher social status. The historical materials in the Yuan Dynasty mention Mazu’s family, especially her parents. This pattern continues with the Ming and Qing Dynasties. They describe Mazu’s miraculous birth and mention the social status of her family, through statements such as “the sixth daughter of Lin Yuan (date unknown), the head of patrol division for the fifth generation of the King of Min” (Zhang 1981), “the little daughter of Lin, the head of patrol division in Putian” (Yan 1993), and “her father is Lin Yuan and she is the sixth daughter” (Jiang 1990b). The pedigree of the Jiumu Lin clan (Jiumu is an important branch of the family name Lin) in Putian was lost before the Ming Dynasty. In the revised version of the pedigree composed by the later generations, Mazu was the granddaughter of the 22nd generation of Lin Lu (274–357), the King of Jin’an County, and in the genealogy of the Lin clan, Mazu was listed as the granddaughter of the sixth generation of Lord Yun, the sixth branch of Lord Pi of Jiumu Lin clan, and the daughter of Lord Weique. Mazu was affectionately called “Ma from the sixth branch of the family” (Liufangma) by the descendants of her family.

The Historical Records of Puyang included the stories of Lin Zao (the first successful candidate in the highest imperial examination from the Jiumu Lin clan) and Lin Yun (a loyal and upright official from the Jiumu Lin clan); according to these authors, Mazu came from a prestigious family. Despite this being an important part of her narratives and representations, some scholars doubted the connections between the Lin family and Mazu. Zhou Ying (1430–1518) from the Ming Dynasty argued that “although she is considered Lin Yuan’s daughter, it might be not true” (Zhou and Huang 2007). Some historical officials additionally doubted whether the post of the “head of the patrol division” existed in the Song Dynasty. Some scholars hold that in the early period of the Northern Song Dynasty, the coastal area of Putian did not have such a post, as Cai Xiang (1012–1067) in the Northern Song Dynasty wrote in an imperial memorial titled To Strengthen the Defense in Coastal Areas Against Pirates that “since the patrols of the Xinghua Army is in the mountains dozens of kilometers away, there are no patrols left for the coastal areas” (Cai and Xu 1996). Being said to come from a prominent family is not unique to Mazu. It is traditional among the scholars of the various dynasties to believe that regional or imperial officials are superior to normal people. In a kind of reverse of this reasoning, famous and legendary individuals are often connected to prominent families but often with no or little evidence. It is at least more likely that these kinds of associations become a standard fixture for legendary figures regardless of their broader narratives and lore. In Mazu’s case, her humble beginning is very neatly connected with her legendary characteristics: a fisher-village woman associated with the safety of fishermen. Whether she was from a prominent family or not is not certain, even though it has come to be a basic part of her legends and representations in many later circumstances. In this regard, most Chinese folk legends about Mazu say that she is a fisherwoman, good at swimming, and familiar with astronomical phenomena, as well as loving and benevolent. Since the sea is unpredictable and dangerous, it is difficult for fishermen to associate a soft and delicate lady from an official’s family with rescue on a stormy sea and heroic undertakings of averting dangers.

We are presented here with a skilled and powerful young woman who was a fortuneteller. Beginning with this basic characterization, two ideas or images emerge in the tradition of Mazu. In addition to her being a skilled fortuneteller, she was considered by some to be a descendant of a prominent official family or, in the other case, she was thought to be the daughter of a fishing family. In either case, the legends continue by depicting much the same story (with many minor variations) that lead up to her becoming deified as a goddess protector.

While the earlier two representations of Mazu developed based on legends of her life and deeds, the third image is that of a goddess who saves and protects people and groups of people from various dangers, especially at sea and on ships. As her representations develop more fully toward a sea goddess, Mazu receives (or is conferred with) several official titles usually of the following style: Lady of Numinous Grace, Princess of Heaven/Celestial Spouse, Holy Heavenly Mother, or the especially impressive, “Protector of the country and defender of the people whose miraculous power manifestly answers (prayers) and whose vast benevolence saves universally”, among others (Duyvendak 1938, p. 344). There are many accounts of Mazu being recognized as a goddess by the imperial court after her death (recorded in the Ming and Qing Dynasties). In these cases, she receives several titles that are variations of “Linghui”—such as Lady of Numinous Grace (Linghui Furen) or Princess of Numinous Grace (Linghui Fei). For example, on Lu Yundi’s (date unknown) diplomatic mission to Korea in the Xuanhe Period of the Song Dynasty (1119–1125), Mazu saved him from danger, so the imperial court awarded the temple name Shunji (”Smooth Crossing”) to Mazu (Ruitenbeek 1999, p. 283). Mazu was awarded the name Linghui during the Chunxi Period (1174–1189), with titles such as Madame Linghui Zhaoying Furen and Madame Linghui, which was conferred on her later due to her deeds of defending against invaders and helping people overcome disasters. These and similar titles refer to her ability to save people through supernatural grace or power.

In the Yuan Dynasty, her title was elevated to a goddess as she blessed the grain transport and maritime safety. During this era, there is a rise of rituals associated with the worship of Mazu, and these rituals gained the social status of national ceremonies. In the early Ming Dynasty, she was awarded the title of Madame Linghui and later the title of Holy Princess. During Zheng He’s (1371–1433) voyages to the Western Ocean, Mazu constantly safeguarded the voyages and fought the invaders, so she was later referred to as a goddess (Tianfei: Princess of Heaven). In the Qing Dynasty, she was awarded the supreme title Tianhou (Empress of Heaven) for assisting Zheng Chenggong (1624–1662) to combat the Netherlands, striking the Ming Zheng Dynasty, and facilitating the recapture of Taiwan.

In the historical records and popular novels of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the names fei, Tianfei, and Tianhou were widely used to refer to Mazu, such as in The Book of Tianfei Making Her Presence and The Book of Tianhou Making Her Presence. The Book of Tianfei Making Her Presence listed many divine and sacred signs of Mazu during her lifetime and after her death, detailing how her superhuman powers were exhibited by her blessing of sea transportation, praying for good fortune, and warding off disease in the Song Dynasty. It was because of the efforts of successive dynasties and the importance attached to maritime trade from the Song Dynasty onwards that Mazu was transformed from a local shaman or sorceress into a nationwide deity. Ultimately, she became one of the most common deities worshipped by international Chinese populations as the migrants from Fujian and Guangdong settled in other countries and regions around the world.

According to the historical records from the Song through the Qing Dynasties, the image of Mazu shifted from being a human being to a shaman, and from there to being a goddess. Li Bozhong notes that through this transformation Mazu becomes “extremely prominent in the development of traditional Chinese beliefs where the relationships between gods and humans are clearly utilitarian” (Li 1997). From the historical archetype of an ordinary fisherman’s daughter in the Song Dynasty, and as a cultural carrier of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, the image of Mazu has continued to evolve through the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties and has been shaped and reshaped following a trajectory that relies on the archetype and transcends the realistic appearance. The image of Mazu is intricately linked to certain political systems and cultural traditions of separate times and places, and is a symbol of faith with continued vitality that meets the needs of the ruling regimes, responds to the demands of society, and is widely accepted by the people, which is one of the reasons for the diversity of Mazu’s statues today.

In this way, Mazu is an especially prominent representative of a traditional Chinese religious phenomena: the deification of prominent people. In a fluid system of promotions that mimicked the Chinese governing and social structures, human beings might change their social status after they died. This process could develop in positive or negative directions. A beneficent legendary figure could evolve as a treasured ancestor, to a kind of family-wide ancestor, then to a sponsor or protector of a village or larger region. This kind of spiritual or mythical promotion could ultimately result in the person being viewed as a goddess or god. In Mazu’s case, she climbs up this celestial bureaucratic ladder to its greatest heights, Celestial Empress, or Goddess of Heaven. This change of state after death could also turn humans into ghosts and demons. In either case, these transformations combined folk and local traditions (for good or ill) with various forms of official recognition and ritual observance. Ancestors (patrons, deities) were remembered with sacred reverence, whereas ghosts (demons, monsters) were feared, exorcised, or avoided. The development of Mazu as a Celestial Goddess is a representative example of this combination of folk and elite religious transformation.

3. Mazu Expressed as an Artistic Archetype of Mazu

In 2009, when the Chinese government submitted a nomination proposal for Mazu to be considered for inclusion on the UNESCO World Intangible Cultural Heritage List, the government used Mazu as the standardized name for the deity, indicating that it is a non-ideological name for a folk deity, which is different from the specific official titles used in different dynasties, and that it is more acceptable worldwide because it is in line with contemporary values. The epoch-making inclusion of Mazu belief and customs in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity shows that “Mazu beliefs and customs” have become the standard name for Mazu rituals and related cultural activities and the folk belief originating in Fujian, China. Moreover, it signifies that its related grassroots customs that are popular with the masses and have been passed down for generations have officially become a piece of the intangible cultural heritage shared by all of humanity. It is a significant milestone for the symbols of traditional Chinese culture to spread globally and be recognized worldwide. It is our intention to explore this process by which Mazu, a regional folk figure or local deity, was slowly transformed into a national (and even international) subject of worship and cultural heritage, and to express how her artistic representations changed and developed throughout this process.

Artistic Archetypes and Mazu: What Is Her Ideal Form?

The word “archetype” (from the Greek term “archetypes”, with “arche” meaning first or origin, and “typos” meaning form) literally means the original form or first model. In a subsection entitled “Mythical Phase: Symbol as Archetype”, Canadian scholar Northrop Frye (1912–1991) defined “archetype” as a typical or recurring image (Frye [1957] 1971). In various fields (psychology, literary studies, religious studies, and art history) the term is typically used today to refer to a generalized type that provides a universal or essential example of shared cultural, religious, or artistic norms, such as Mazu expresses the archetype of the “mother goddess” (like Egyptian Isis or Greek Demeter) and of a universal protector goddess (like Indic Durga or Sumerian Inanna). The archetype refers to a typical pattern that repeatedly occurs over time as things develop, a mental response that emerges countless times through the same type of experience, and the basic archetypal imagery of the unconscious collective that is passed down from generation to generation.

For religious folk art such as Mazu paintings and statues, as the Swiss scholar C. G. Jung (1875–1961) argues, the creative process of art “consists in the unconscious activation of an archetypal image, and in elaborating and shaping this image into the finished work. By giving it shape, the artist translates it into the language of the present, and so makes it possible for us to find our way back to the deepest springs of life. Therein lies the social significance of art: it is constantly at work educating the spirit of the age, conjuring up the forms in which the age is most lacking. The unsatisfied yearning of the artist reaches back to the primordial image in the unconscious which is best fitted to compensate the inadequacy and one-sidedness of the present. The artist seizes on this image, and in raising it from deepest unconsciousness he brings it into relation with conscious values, thereby transforming it until it can be accepted by the minds of his contemporaries according to their powers” (Jung 1978).

Artisans create statues of Mazu by narrating, pondering, and imagining the myths and legends of the goddess. They consider her customs and the spirit of her in rituals, and the models of her statues in different forms of worship, through the experiences in their minds inherited from their ancestors. In addition, the artisans draw on broadly shared religious, spiritual, and mythological symbols and experiences to transform the collective imagery of believers into concrete images and statues of gods and goddesses. The worshipers can understand Mazu’s image qualities through the stereoscopic statue of Mazu and the two-dimensional plane images of Mazu. The worshipers describe and hypothesize about the characteristics of the Mazu goddess through the miracles of Mazu in stories, folk customs, and sacrificial ceremonies as expressed in the relationship between Mazu and their local region or country. Mazu’s images are adaptable and dynamic because of the various sites of worship, worship groups, belief regions, statue-producing technology, and mainstream goddess statue aesthetics, which have proliferated with Mazu culture in China and coastal regions around the world. The construction of Mazu’s archetypal symbols is the distillation of the typical image among numerous paintings and statues, and the presentation of visual symbols to convey the essence of Mazu culture and to realize the cultural identity of the coastal Chinese, in addition to Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan compatriots, as well as others where Mazu’s traditions have spread.

4. The Construction of Mazu’s Archetypal Artistic Symbols: From “Overseas Diffusion by International Chinese” to “Cultural Identity”

In the pre-modern era, maritime merchants and overseas Chinese often placed their hopes for safe arrival on Mazu when sailing; they had a Mazu shrine in their sea vessels when they went to sea, and they held certain worship rituals before going to sea and after arrival. In his article on Chinese trade to Batavia during the days of the V.O.C, Leorard Blusse described how a Dutch sailor, Stavorinus, took a three-masted sailing ship from Fujian, China, on his way to Makassar in 1775 and saw an altar for a deity in the center of the steering station located among several small cabins at the stern of the ship (Blussé 1979, p. 199). On an auspicious day for starting the voyage, “seafarers took the statue of Ma-tsu, the goddess of the sea, from the shrine on the ship and parade to the temple to pray for a safe voyage. The pilgrimage to the temple is often accompanied by a theatrical performance, while all the seafarers share wine and offerings such as meat, fish, and other dishes. After the ritual, the statue was brought back, and the ship set sail amid the sound of gongs and firecrackers…. In this way, Chinese seafarers kept connected with their goddess during the voyage, trying to subdue the forces of nature” (Blussé 1979, p. 201).

According to Singaporean literature, the seafarers on the first ship from Xiangzhi Township in Jinjiang, Quanzhou, immediately took the Mazu statues from the ship and set up a shrine on land upon their arrival at Telok Ayer in the south of Singapore in 1821. They burned incense and worshipped the goddess to express gratitude for her protection during their safe voyage. Chinese people who migrated overseas via seagoing vessels in southern China spread the belief in Mazu from their homeland to other countries by building Mazu temples in places where they had taken root or by setting up shrines in their overseas homes. For example, Zheng Zhilong (1604–1661), the father of Zheng Chenggong (1624–1662), a native of Nan’an, Fujian Province, went to Pinghu at the age of 20, and was a businessman engaged in marine trade.

There is a camphorwood Mazu statue that was carved in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) with a height of 28 cm, with the accompanying immortals Clairvoyance and Clairaudience both with a height of 19 cm, in Zheng Chenggong Memorial Hall, Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. It is said that they were a group of statues originally placed on the marine trade ship. Afterwards, Zheng Zhilong transported them to an ancestral hall built on the back mountain of Pinghu for worshipping. Considering the severe damage, the National Treasure Repair Institute of Kyoto Academy of Fine Arts maintained and repaired them in December 1990 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ming Dynasty Mazu statue in the Zheng Chenggong Memorial Museum in Japan. Source: Author’s photograph.

Compared with the Wuguan Mazu statue worshipped in Luermen Notre Dame Temple in Taiwan Province, the Mazu statue shows a similar body shape in appearance. It is said that the Martial Arts Mazu statue worshipped in Luermen Notre Dame Temple in Taiwan Province was one of the three statues of Mazu (later generations calls them Kaiji Mazu (开基妈祖), Wenguan Mazu (文馆妈祖), and Wuguan Mazu (武馆妈祖)) that accompanied Zheng Chenggong’s attack on Taiwan. Therefore, people pray to Mazu not only for protection when navigating at sea, but also for assistance in defeating enemies.

In the early Qing Dynasty (1644–1735), especially in Taiwan, to maintain state unity and island-wide stability, the Qing government repeatedly assigned the coastal naval officers and soldiers of Fujian and Zhejiang, so the myth of Mazu’s manifestation and assistance became necessary for rallying the troops and boosting morale. The body and appearance of the two Mazu statues look much the same, except that the former has a slightly higher crowned head and a knee covering (Bixi 蔽) hanging in front of the abdomen. The arms of the two Mazu statues separately rest on both sides of the round-backed armchairs. In the right hand, it is assumed that Mazu is holding a Ruyi (a traditional Chinese ceremonial wand, scepter, or talisman) based on the gesture of holding something upright. As for the left hand, that of the former Mazu is naturally hanging down, while that of the latter Mazu touches the jade belt around the waist, a rare gesture that is suspected of having been adapted and designed by the artisans when considering Mazu’s military background.

These Mazu statues, whether they are large ones enshrined in temples or small ones worshipped at home, or whether they were made by immigrants from southern China after they had established roots in Japan or were brought to foreign lands from their hometowns, all retain the typical features of China’s native Mazu in the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties (1600–1644). These features include a diadem headpiece with decorations at the temples, a robe with large sleeves and a round collar, a silk shawl hanging down around both the arms behind the shoulders, smooth draping patterns, a round and plump belly, an exquisite round-backed armchair for Mazu to lean against, and two lower legs slightly splayed.

4.1. Assimilation, Change, Syncretism, and the Spread of Mazu Worship Internationally

Mazu culture has spread widely overseas through the medium of the overseas Chinese, but the process of spreading it has not been easy, with both active integration and rejection. Firstly, with the change in the psychological setting and due to the evolving spiritual needs of the international Chinese populations, the people’s understanding of Mazu had become increasingly diversified. According to the traditional religious consciousness of Chinese folk believers, deities that initially had multiple roles and were worshipped in separate places were called “the local spirits of the local land (当方土地当方灵)”. When immigrants settled overseas, the spiritual power of Mazu to protect the safety of maritime navigation became weaker and weaker. These immigrants began to hope that they could find a safe, stable, and harmonious power in the strange and disorderly new living environment to shelter them in peace, prosperity, and happiness. Therefore, the motivation of the international Chinese to worship Mazu has become increasingly diversified. Moreover, other aspects of Mazu’s roles were emerging and increasing, such as seeing Mazu as a deity of business protection, wealth, benevolence, and filial piety, or similar concerns of settled immigrant communities.

Secondly, Mazu was accepted by other religions, co-worshipped with other deities, and even appeared in syncretic images, which continued to grow and spread, gradually penetrating the local ethnic and folk communities. During the global spread of Mazu, there were not only cases of co-worship with other local Chinese deities such as Guanyin (a Buddhist bodhisattva) and Qingshui Zushi (a Daoist deity) in international Chinese temples, but also the phenomenon of forming a common deity with foreign deities. For example, in the Chao Phor Seua Shrine, also known as the Tiger God Shrine, located on Tanao Road, Bangkok, Thailand, Lord Zhenwu (a Daoist deity) and Mazu worshipped by the Chinese, and the Tiger God believed in by the Thais, are worshipped in the same temple, which is visited by Chinese and Thai people from all over the world every day (Duan 1996).

In other places, the worship of Mazu has faced opposition. In a different social strategy, the Indonesian government once used political power to carry out a policy of total assimilation, suppressing Chinese culture and outlawing many Chinese ethnic traditions and activities. Despite these obstacles, Indonesian folk religious beliefs such as the worship of Mazu have been preserved through affiliation with Buddhism, and the Chinese have been united by Mazu temples, ancestral halls, other religious activities, and Buddhist associations (Tan 1991).

When the Philippines was still under Spanish colonial rule (1565–1898), the Spanish colonizers set the policy of Hispanicizing the ethnic Chinese in the Philippines to reduce the threat of the ethnic Chinese to their rule. They not only forced the ethnic Chinese to cut their hair and convert to Catholicism, but also deported 2070 overseas Chinese who refused to change their religion (Zeng 1998). Some international Chinese, although forced to change their religion to survive, persisted in worshipping Mazu in many ways, because deep in their hearts, they maintained the belief in Mazu from their homeland in Fujian and Guangdong, and their longing and emotional attachment to their motherland. It is evident that the Mazu beliefs in East Asia and Southeast Asia have been influenced by many factors. The worship rituals and ceremonies of Mazu are confined to the local international Chinese and Chinese business-people’s guild halls, and Chinese worship methods have been maintained.

In contrast to some of these other approaches, the spread of Mazu representations, rituals, and beliefs in Japan showed two distinct trends. The first trend fuses her imagery with a variety of local sea goddesses revered at Shinto shrines. The second trend, discussed subsequently, is the tradition in which Mazu imagery is fused with that of Funadama (a Shinto deity, protector of seafarers, who was worshiped in different locations throughout Japan (Ng 2020, p. 228). The first trend is the significant regional transformation of Mazu as represented in Chinese Buddhist, Daoist, or folk traditions into specific local Shinto deities (often associated with ships or the sea), which Ng (2020) refers to as Shintoization, especially in the Mito Domain and Satsuma Domain during the Tokugawa period (1603–1867). The Mazu beliefs were introduced to the Mito Domain at the end of the 17th century. The second daimyo of the Mito Domain, Tokugawa Mitsukuni 德川光圀 (1628–1701), not only entertained Chinese Zen monks but also built the Isohama Tenpi Jinja 矶浜天妃神社 (also called the Tenpisan Maso Gongensha 天妃山妈祖権现社) on the shore of Iwaichō 祝町 (now Ōarai) and attended the Tenpi Maso Daigongen (天妃妈祖大権现) festival (Ng 2021, p. 130). The worship of Mazu in Japanese shrines contributed to the Shintoization of the Mazu belief in the Mito Domain, where people regarded Ototachibanahime (the local goddess of the sea in Japanese Shinto) as Mazu, calling her “天妃さん”, and changed the date and form of Mazu worship to a localized Shinto and Japanese shrine ritual (Ng 2021, p. 131).

A 35 cm high statue of Mazu (Figure 3), formerly enshrined in the old Tiansheng Temple, is now a nationally designated Important Cultural Property of Omitama-shi in the south-central part of Ibaraki Prefecture in Japan. It is said to be one of the three copies of Mazu statues brought by Master Donggao Xinyue (东皋心越) when he was invited by Tokugawa Mitsukuni to visit Mito in 1682. The other two are enshrined at the Mazu Shrine in Isohara, and Master Donggao Xinyu presided over the consecration ceremony (Ng 2021, p. 132). The local replica of this Mazu statue markedly differs from the original one that was brought by Master Donggao Xinyue and placed in Gion Temple (祇园寺) by Tokugawa Mitsukuni in 1691, in terms of dress, posture, and appearance. This replica is said to be made by Japanese craftsmen based on the image of a goddess in the Japanese Shinto system. The reinterpreting of Mazu via the local Shinto deities, otherwise referred to as the localization of Mazu images, in Japan, is also reflected in a Mazu portrait from the Edo period (1603–1867) in the collection of the Ei Museum of History and Folklore in Japan. In this portrait, Mazu’s crown, hairstyle, face, and costume such as the silk shawl are all in the Japanese style in terms of color, shape, and pattern, which is a precious example of the localization of Mazu images in the latter half of the Edo period (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

The statue of Mazu in the old Tiansheng Temple. Source: Author’s photograph.

Figure 4.

A Mazu portrait from the Edo period in the collection of the Ei Museum of History and Folklore in Japan. Source: Author’s photograph.

In addition to the Mito Domain, the belief in Mazu spread to Kasasadake 笠沙岳 (after worshipping Mazu on the top of the mountain, it was renamed Nomadake 野间岳) in the Satsuma Domain and was also Shintoized. Noma is located at the eastern end of the Satsuma Peninsula, a small island extending into the East China Sea, which is home to Nomadake. Chinese merchant ships heading east via the Ryukyu Islands often used Nomadake as a navigation mark. On the top of Nomadake is the Nomad Shrine, divided into two shrines, the eastern and western shrines. The western shrine is dedicated to Mazu and several deities from Japanese mythology, such as Honosusori no Mikoto (火阑降命), Hikohohotemi no Mikoto (彦火火出见命), and Honoakari no Mikoto (火明命) (Ng 2020, vol. 47, p. 232). The Mazu statues left at Nomadake’s western shrine were brought by the Lin family when fleeing to Japan in the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties. After settling in Satsuma, not only did the Lin family become a major local family by making a fortune in trading, but the area also became a prosperous trading port between Ryukyu and southern China. Mazu was worshipped as a Shinto deity at Nomadake, and Mazu rituals at Satsuma Noma Shrine were grander than those in any place outside of China. However, due to hurricanes, repeated fires, and the decline in seaborne trade, the statues of Mazu were no longer seen at Nomadake.

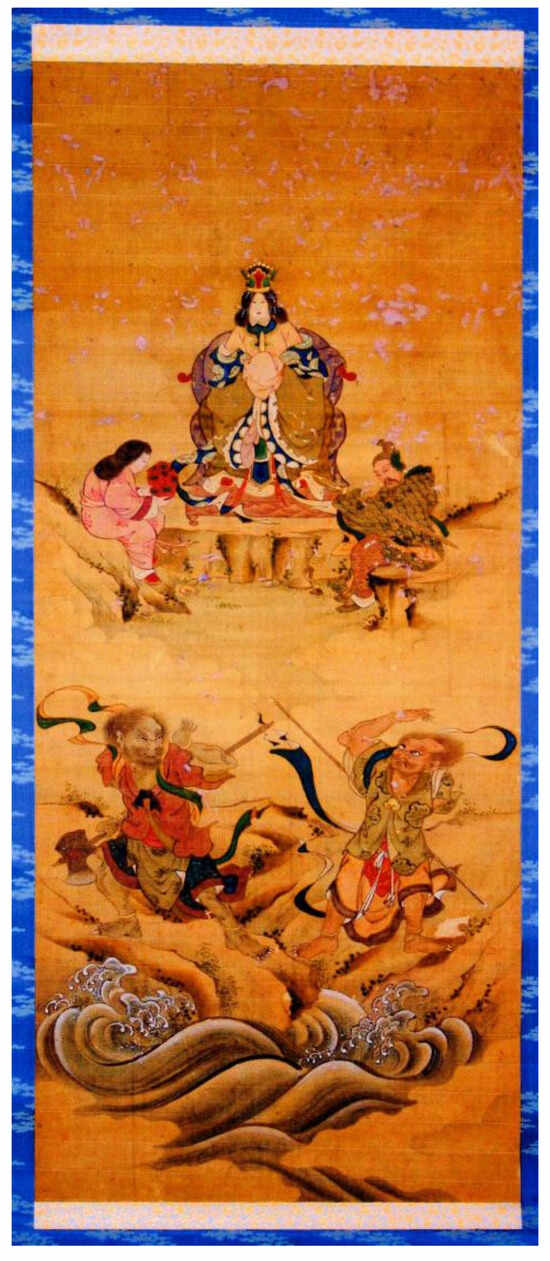

The second trend in the fusing of Mazu imagery with local traditions is the habitual association of Mazu and the Japanese deity Funadama (this “ship kami” is a spirit or class of spirits who ensure a good catch for fishermen, and who protects ships and seafarers throughout Japan). In contrast to Ototachibanahime, who appears in Shinto literary tradition of the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, Funadama (also Funadamagū 船玉宫 and Funadama Myōjin 船玉明神) refers to a collection of rituals and beliefs about protection of ships, seafarers, and fishermen (Ng 2020, vol. 47, pp. 228–29). Funadama has been recorded in texts from as early as the eighth century. However, different Funadama rituals and traditions are officiated in distinct parts of Japan, so there are different names, rituals, and expressions that are all gathered and collectively referred to as the worship of Funadama (which over time referred to multiple ship kami and ship bodhisattvas). In the Tokugawa period, Japanese people regarded Mazu as Funadama, and with this fusion the deity “Funadama” artistic representations begin to be become increasingly feminine, and to especially have the characteristics of Chinese Mazu reimagined in Japanese styles. Tosa Hidenobu (date unknown), in the Supplementary Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images (增补诸宗佛像图汇), depicted Mazu as a goddess in a diadem headpiece and a robe with large sleeves, holding a tablet (Hu 笏). The inscription in the picture reads: “According to tradition, at the time of Emperor Taizong 太宗 (939–997) of the Song, a fisherman’s daughter ascended to heaven on the ninth day of the ninth month in the fourth year of Yongxi 雍熙 (987). There was a voice from the cloud, saying, I am the manifestation of Guanyin, and now I am ascending to heaven. I will safeguard maritime transport and will be worshipped as Funadama” (Ng 2020, vol. 47, p. 230).

Because of this fusing of Mazu with Funadama, artistic representations of Funadama begin to prominently feature Mazu imagery. For example, a copy of a hanging scroll named Funadama (the goddess of ships) from the Echi-zen Shokaiji Temple (越前性海寺), dated 1851, is in the current collection at the Kyoto City University of Arts, Japan. The Morita family ordered this scroll from the Buddhist painting workshop via the Shokaiji Temple. The text in the middle of the scroll states the origin of the goddess, and along with the text, it is clear from the appearance and dressing of Mazu depicted in the painting, the appearance of her maids, and the style of the hand-held long fan, that the goddess image is based on Mazu from the Lin family in Xinghua, Fujian Province in the Song Dynasty and is influenced by the Chinese belief, with Japanese characteristics. In his article on Mazu worship in East Asia and Funadama worship in Japan, Fujita Akiyoshi quoted the whole passage on the origin of the goddess in the painting, analyzing fourteen Japanese papers from 1700 to 1800 that touched upon Mazu’s introduction to Japan as a Chinese goddess of ships, and compared Mazu with the Japanese goddess of ships (Fujita 2021). In an article on Mazu’s connection to Japanese Funadama Myojin, Fujita Akiyoshi mentions that, in Japan, many of Funadama Myōjin’s hanging scrolls from the second half of the 18th century onward are painted in imitation of Mazu (Fujita 2008).

The belief in Mazu was gradually incorporated into the local religious system in Japan during the Tokugawa period. Mazu is no longer a folk deity from China but has become a Japanese Shinto deity. Her roles extend from being the guardian deity of maritime navigation to being the guardian deity of the local area of Japan. The folk beliefs of Mazu, which originated in Fujian, China, were widely accepted by the Japanese people and were successfully incorporated with Japanese Shinto to form a localized belief system. Describing and discussing Mazu as an archetypal symbol depends on this fundamental pattern where other populations and cultures imagined or discovered “Mazu” as present in their own cultural symbols. What had been separate local Shinto Kami, or generalized rituals to Funadama, fused with Mazu. Artistically, it was Mazu who dominated this fusion; the local images took on her shape and forms or were directly inspired by them.

4.2. Mazu and the Christian Madonna

As a visual symbol, Mazu images and statues are the physical carriers of Mazu’s beliefs and customs. They are also an important link and emotional support for the Chinese and overseas Chinese to maintain national cohesion, centripetal force, and a sense of national identity, which can penetrate language barriers and geographical boundaries and inspire the deepest native emotions in people’s hearts. In international settings, the Mazu cult brought by the ethnic Chinese interacts and interfaces with the religious beliefs of the host country. Although Mazu belief was initially rejected in the Philippines, it was slowly accepted over time by the religion practiced by the state. Particularly during the Great Age of Sail after the 16th century, representations of Mazu and of the Christian Madonna began to artistically reflect and merge with each other, with some of the Madonna statues being seen by the Chinese as an alter ego of Mazu.

The Roman Catholics Christians believe in Jesus Christ. According to Catholic tradition, Jesus’ mother was a virgin named Mary. The Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus, was the first person who realized Jesus was the son of God, and the world’s first to witness the signs of Jesus. The faithful believe that she became pregnant through the spiritual intercession of the Holy Spirit, and that she remained a virgin perpetually. For Roman Catholics, Mary is in some ways the first and most important saint of the tradition. Based on these Christian traditions, artistic representation of the “Virgin and her child” has long been a common theme for Western artists.

Two versions of the Madonna, Our Lady of Caysaysay and Our Lady of Antipolo, are worshipped as protectors of the sea and journeys. According to local traditions, in these forms the Madonna has manifested many times, and as such they are the deities that local fishers in the Philippines pray to when they go to sea. Their divine office is the same as that of Mazu. In the province of Rizal, east of Manila, people see Mazu and Our Lady of Antipolo as one (Dy 2014). According to The History of Catholic Temples written by a Catholic priest in 1611, the following is recorded: In 1603, a Filipino fisherman named Juan Maningcad found a wooden statue of the Madonna resembling Mazu in the Pansipit River in Barangay Caysasay in Taal, Batangas. Subsequently, the local tradition reports repeated paranormal phenomena where the statue repeatedly disappeared but then later reappeared and returned to its original place. The local Chinese community built a small temple on the river to worship it. This kind of story is common in Catholic traditions of representation of Mary, and here it is explicitly fused with Mazu artistic representations.

According to The Record of Meizhou Mazu (Meizhou Mazu Zhi 湄洲妈祖志), the temple was the first Mazu temple built in Taal town by the overseas Chinese in the Philippines. Although Filipinos worship it as the Catholic statue of Our Lady of Caysaysay, the Chinese worship her as Mazu (Hong 1990). A golden statue of the goddess that has a blend of Chinese and Western styles, is enshrined in a Catholic church in Batangas Province, located in the southeastern part of Luzon, Philippines. The statue is clad in a magnificent Catholic costume decorated with patterns of the sun, moon, and stars. She wears long and wavy hair and an exquisite crown, with a cross on the top. The crown is surrounded by a ring of stars, like the shape of a halo. The main body of the crown is the same as the one used by Napoleon to crown Queen Josephine in the famous painting “The Coronation of Napoleon,” which is a standard crown style in the West. Over the years, a customary ritual has been performed in the area: every Thursday afternoon, the statue of Mazu is taken from the Taal Cathedral to the small temple of Mazu in Barangay Caysasay. On Saturday afternoon, it is brought back to the cathedral from the small temple of Mazu. This happens week after week, without interruption.

Every year, in the small temple of Mazu in Barangay Caysasay, a five-day Christmas extravaganza takes place during Thanksgiving weekend. The practice of holding a three-day celebration in the original hometown of Meizhou from the 23rd to the 25th of March in the lunar calendar is also continued in the Chinese community. The two events mentioned above were held to honor Mazu’s birthday (Note: According to the legend of the Mazu celebration held in November, people may regard the day of the discovery of the statue of Mazu in Batangas Province, the day of welcoming back to Batangas Province, or the day of the construction of the temple, as the birthday of Mazu.). The festival celebrated in November is more elaborate. In addition to burning joss paper and incense, performing Chinese opera, offering sacrifices, and burning incense and candles to honor Mazu, it also invites Catholic priests to preside over a variety of religious and cultural rituals, including the Mass. In 1954, during the Marian Congress in the Philippines, Pope Pius XII designated Mazu as one of the seven manifestations of the Virgin Mary and grandly crowned Mazu (Z. Lin 1989). This statue of the goddess, which combines the religious beliefs of the East and the West, is worshipped by both Chinese living in the Philippines and Filipinos of the Catholic faith.

Similar phenomena are found in other countries in Southeast Asia and areas such as Macau and Taiwan. At the beginning of the 16th century, Macau was the main supply port for maritime trade between Portugal and China. When the Portuguese seafarers first arrived at the port, they landed at the Mazu Pavilion in Macau, and, since then, the name “Macau” has been added to the Western language. As soon as they entered Macau, they began to build St. Paul’s Cathedral, and Catholicism spread and developed in Macau. At that time, Portuguese Catholicism and traditional Chinese religion coexisted in Macao, with the Portuguese residing in Macao likening the Mazu worshipped by Chinese believers to the venerable Virgin Mary, and Chinese people there likening the Virgin Mary to Mazu, also known as the goddess of the sea and goddess of heaven. The Chinese and Portuguese navigators not only regarded Mazu and the Virgin Mary as deities for the protection of their voyages, but they also viewed each other’s maritime protectors through the eyes of their own traditional cultures, a typical collision and convergence of Chinese and Portuguese folk religious beliefs and worship. The Francisco Church on Macau’s Coloane Island houses not only a statue of the Virgin holding her son, but also a painting named “the Madonna Mazu,” depicting a Chinese woman in Chinese costume holding a child in her arms. This work is a traditional Chinese ink and wash painting instead of a Western oil painting (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Inside Francisco Church, Macau: a painting of the Madonna Mazu and a statue of the Virgin holding her son. Source: Author’s photograph.

The Portuguese not only acknowledged Mazu worship in Macao but also Westernized the goddess of the sea in the spiritual world venerated by them, with Mazu statues enshrined in Catholic churches. Coincidentally, there are also some statues of Mazu in Taiwan that are depicted in a Western style, resembling the likeness of the Virgin Mary. For example, The Second and Third Times of the Envoys of the Dutch East India Company to the Qing Empire by Olfert Dapper (1636–1689) includes a painting using Western copperplate techniques depicting the statue of Mazu as seen by the Dutch in the Mazu Temple in Taiwan. In Taiwan, the common name for Mazu, Holy Heavenly Mother, is also used for the Virgin Mary. There is even a statue of the Holy Heavenly Mother and Saint Mary at the Ordo Sancti Benedicti headquarters in Chiayi City. It can be seen from the Mazu statue dressed in a unique style, a painting of Mazu holding a baby, and the portmanteau of “the Madonna Mazu” that the Mazu belief is transformative, cohesive, and powerful. Although the artistic representations of Mazu statues differ across the globe, the belief in Mazu, as a symbol of faith and culture, is a product of the long-standing interchange and integration of Chinese, other Asian cultures, and Western cultures, both in terms of their artistic representation and the local practice of worship and festival. Mazu’s multi-faceted expansion under different faiths and cultures and the deity’s localized continuation in new environments expresses the power of her two-way cultural interaction and exchange.

The archetypal symbols of Mazu’s statues and pictorial art are the mapping of a religious concept, a way of belief, and some programmed behaviours and rituals. It is also an emotional imagery used to arouse the cultural awareness of international Chinese, inspire them to help and trust each other, to encourage and to comfort each other, to share weal and woe, and to always forge ahead. At a time when images and statues of Mazu are taking on many different forms, the construction of the archetypal symbols of Mazu’s statues and images not only allows people to see what Mazu looks like, but also serves as a symbol of Chinese people living in different countries missing their hometown and a bridge between them and their motherland. Because it is closely based on Chinese maritime culture and conveys the spiritual connotation of freedom and peace, and of equal exchange and interconnection, the archetypal symbol of Mazu has become a unique sign of the fusion of farming culture and maritime culture in different fields, borders, and ethnic groups today. Moreover, it has become a visual carrier for the dissemination of ideas, religion, and culture. It is also a cultural bridge for all peoples of the world to achieve communication. In this way, Mazu’s symbolic representation is meant to create harmony and meaning between and among diverse populations.

In this context, we can see that the human origins of Mazu and Mary are only partly related to the development of their cults as saints or goddesses. Mary, in the Christian tradition, is the mother of Jesus (and the text additionally refers to her having other children when Jesus was an adult); however, she remained, through a form of supernatural agency, a perpetual virgin, a saint, and the Mother of God (in Christian tradition). Mazu, based on a young woman who never had children, becomes Protector Deity and Mother Goddess. In either case, we see how nurture, protection, and security are generalized in “mother” and “grandmother” archetypes. The case of their actual nature as mothers (or not) is not the fundamental symbol or concept in this case. Their universal appeal as mother-protectors is what is exemplified and modeled in the mother-with-child artistic representations. This is the direction of Mazu’s historical development as an archetypal image. Thinking comparatively, an artistic tradition of representation need not necessarily develop this way. In comparison, Durgā (Mahā Devī) in the Indian Hindu tradition, is referred to as Ma (mother) and is a protector, but she is usually depicted as youthful, wielding an array of weapons, and riding a lion or tiger. Durgā has her own stories, scriptures, development, and associations, and so her representations follow their own history. The point of this comparison is that the archetype of mother protector develops artistically in its historical contexts. Being a mother and a protector is not enough—on its own—to develop a coherent image. In Mazu’s case, the close association with the Madonna in Catholic contexts or separately with Funadama (the goddess image is based on Mazu from the Lin family in Xinghua, Fujian Province in the Song Dynasty and is influenced by the Chinese belief) in the Japanese context guides the historical emergence of the new symbols and representations.

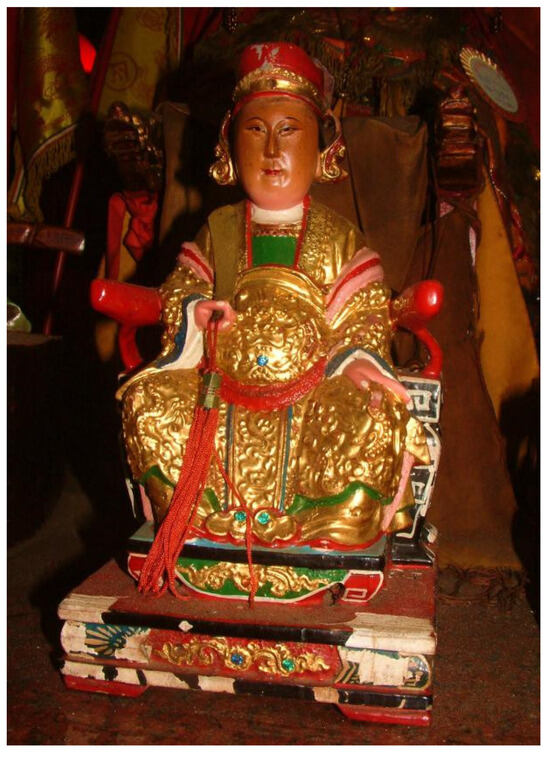

5. The Foundation for the Construction of the Archetypal Symbol of Mazu Art: Representations and Metaphors of Goddess Worship

Mazu was revered as a female deity in the minds of the Fujianese. This reverence is closely related to the ancient Fujian goddess worship. First, it is reflected in the change in the honorific title of Mazu. In his article on origin of the name “Mazu,” Mr. Jiang Weitan pointed out that the gradual change in the name of the goddess Mazu in folklore proceeded as follows: from “Goddess” (Shennü 神女, 1150AD), she became known as “Spiritual Lady” (Lingnü 灵女, 1444AD), then “Niangma” (娘妈, 1561AD), and finally “Mazu” (1644–1735AD). Goddess is the common name for Mazu, which describes her transformation from a human fortuneteller to a goddess; the name “Spiritual Lady” corresponds to the first identification of the Lin family with Mazu; the name Niangma is related to a folk custom of a Fujian Xinghua folk woman who misses her mother’s family; and Mazu is an abbreviation or acronym for “maternal ancestor.” The name “Mazu” was changed from “Niangma” on Taiwan island in the early Qing Dynasty (1644–1735) (Jiang 1990c). This statement is supported by an ethnologist Lin Meirong, who argues that in Taiwan, the name for Mazu was changed in turn to niang (娘), ma (妈), zu (祖), po (婆), and shengmu (圣母): “Mazu was known as Moniang (默娘) when she was alive. She became a goddess after she died, unmarried, so she was then called Niangma. After she became a goddess, she was called Mazu as her age grew, then Mazupo, with the character po indicating that she was even older. In Taiwan, Mazu is an image of a mature and steady woman rather than a fair-faced young lady, which is all reflected in how she is called by people” (M. Lin 2008).

Secondly, in the world of ancient Chinese folk deities, there existed many female deities, such as Wangmu Niangniang 王母娘娘 (Mother Goddess), Bixia Yuanjun 碧霞元君 (Lady of Blue Clouds), and Xi Wangmu 西王母 (Queen Mother of the West). According to Mr. Xu Xiaowang, “the northern deity system, represented by the Central Plains culture, is full of masculine beauty. Most of those who have the power to dominate the world are male deities. On the other hand, the southern witch culture, represented by Fujian, created many female deities” (Xu 1993). Deities such as Gutian’s Lady Linshui (临水夫人), Quanzhou’s Liu Gumma (刘姑妈), Hetang’s Ma Xiangu (马仙姑), Nanjing’s Yin Xiangu (鄞仙姑), and Mingxi County’s Xin Qiniang (莘七娘) are all independent goddesses who do not need to be dependent on male deities in their respective fields of faith and can dominate everything. They can not only help women in childbirth, but also have the functions of traditional male deities such as driving away enemies, eliminating ghosts, subduing demons, praying for rain, and fighting drought. In ancient times, Fujian women were subjected to significant pressures of life. To seek spiritual support and emotional appeal, they worshipped all the ghosts and gods that could help them eliminate disasters.

Mazu is the product of the psychological refraction of the goddess worship of the Fujianese, but there is no universal or singular artistic representation of Mazu in people’s actual lives. After Mazu was transformed into a goddess, the image of Mazu in paintings and statues inevitably needed to be derived from the form of the human female while at the same time reflecting the solemn and compassionate spirit of the deity. Thus, folk artisans are required to thoroughly understand and correctly master the rules and regulations for making statues of the deities. They can enable the believers to have a respectful, joyful, and lucid mind upon seeing the statues through direct visual understanding and symbolic signs, generating an inexplicable spiritual force under the religiously infectious power of the “superhuman” statue. The image of Mazu cannot be identical to the appearance of a mortal; otherwise, it would be difficult to express her divinity beyond the ordinary. Although Buddhist art has special rules of expression, namely the 32 major characteristics and 80 minor characteristics of a Buddha, Mazu statues belong to folk religious art, which focuses on integrating a national, secular, local, and living atmosphere with a religious one. As such, the rules and regulations exist to make statues silently permeate the culture. Among the characteristics of Chinese Buddhist art, there are “standing or sitting upright” and “full and round shoulders”, among others. Statues of Mazu, in general, reflect worldly female kindness. Specifically, in addition to a full and smooth face, the skin between the chin and neck has slight double chin-like wrinkles due to plumpness; the upright and well-proportioned posture displays a solemn poise and sacred spirituality; the comely appearance glows with a gentle, respectful, and amiable air; and the round shoulders reveal the goddess-like love and greatness in the same artistic fashion as in Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism.

In some cultures, ears are a symbol of good fortune, and round and thick ears embody profound fortune and longevity. There is a common saying that “big ears are blessed”. The “stretched ears and long lobes” of the art of Buddha statues are an exaggerated representation of the large ears of the Buddha, which are pierced for earrings. The existing Mazu statues, from the one in Wenfeng palace in Putian and the one in the Mazu Palace in Putian’s Meizhou Island, which is the ancestral temple of thousands of other Mazu temples, to ones preserved in the Putian Museum, have long ears and lobes full of piercings. Mazu’s eyes are slightly open, looking down, like the eyes of the Buddha. This position of the eyes is meant to imply that a person should focus more on his or her own words and deeds instead of others’ mistakes. This gesture also expresses benevolence and care.

In ancient Chinese philosophy, although there is a clear distinction between the physical appearance of mortals and that of the deities, a certain connection exists between the human eyes and ears and those of the deities. Xie Zongrong, a researcher of traditional Taiwanese art, argues that most of the pink-faced Mazu worshipped in Taiwan present a feminine and motherly appearance, with kind faces and drooping eyes that display Mazu’s care for the believers (Xie 2008). Mazu’s eyes are not closed, indicating that she is looking at all beings with the cool wisdom of an honest and upright perspective. These open eyes artistically demonstrate Mazu’s openness and connection with her human worshipers. The eye contact between Mazu and the worshipers provides insight into the worshipers’ need to show compassion, pity, and mercy. These types of artistic styles are thought to be soothing and comforting to their minds and souls, and are thought to make them mentally strong. Believers always feel that they are watched and observed by Mazu, no matter where they are and how they move in places such as temples and ancestral halls. This is, in fact, a top-down mental correction of a visually distorted human face that the human psychological mechanism unconsciously makes. In other words, the eyes of Mazu statues are fixed on the worshipers because the latter have restored the distorted perspective. The characteristics of Mazu statues, such as the distinctive eyes and brows, long ears, and round shoulders, not only draw on the basic rules of Buddhist art, but also incorporate the features of ordinary women’s appearance, which is a projection of Fujian people’s goddess worship (Figure 6). It is the combination of ordinary human emotions and the goddess’ generous divine power that lays a solid foundation and serves as the source for the construction of Mazu’s archetypal symbols.

Figure 6.

A statue of Mazu enshrined in Nanfang’ao Mazu Temple in Yilan, Taiwan. Source: Author’s photograph.

6. The Method of Constructing the Archetypal Symbol of Mazu Art: The Imagery and Form of Mazu Beliefs

The archetypal symbols include not only the initial imagery of Mazu in the believers’ mind, but also a figurative art form in folk religious art, in which there are some conventional symbols. The body, head, and foot apparel of Mazu are symbols of the signifying characteristics of the statue and image of Mazu, with clear symbolic meanings. These are not only ornaments and coverings for the body of Mazu, but have also evolved into a form of communication, a symbolic language through which people could express their thoughts and wishes to the gods. Mazu’s costume has changed over time to show the status and divine office of different historical periods. The divine costume of Mazu is composed of both secular women’s costumes and empress costumes of different dynasties. In the existing statues, prints, and paintings of Mazu of the Song Dynasty, her costume is based on that of a woman from a noble family or concubine, including a crown or a high bun, a large-sleeved robe with a long skirt, pointed shoes partly covered by the long hem, a belt around the waist, a silk shawl, and cloud shoulder.

In most statues and images, Mazu faces the viewers. In particular, the giant clay statues in the main halls of temples and the small ones in the niches wear brightly colored crowns and oversized cloaks and hoods, and the believers always kneel right in front of the statues to worship them. Therefore, it is not easy to see the back of the statues or their hair buns. Taking the seated soft-bodied Mazu statue in Wenfeng palace as an example, the hair bun stretches out from the top of the head, pointed and high. Jizong (髻鬃), the traditional hair bun of the Hakka people in southern Fujian Province, is still in use today, with the styles of Liangba (两把) and Sanba (三把) for unmarried and married women, respectively. Liangba and Sanba, respectively, mean that the hair is parted into two or three sections, with each section curled and folded into a 15-centimetre knot at the back of the head. The bun on the head of this Mazu is also like the shape of the top of the sail-shaped hairdo (船帆头, also called a Mazu bun) combed on the back of a woman’s head in present-day Fujian. In Meizhou, Fujian, there is a folk legend about this hairstyle: when Mazu was 18 years old, her parents made plans for her marriage. Mazu is said to have spent three days and nights in her boudoir coiling and pulling her hair to resemble a sail-shaped bun, because she was determined to help fishermen and to never marry (He and Zheng 2014). The Mazu bun has been imitated and passed down by Meizhou women because it is considered to be a symbol of good luck and peace. As can be seen from the back of the statue in Figure 7, the artisans did not make the Jizong at the back of Mazu’s head very prominent, and it is, instead, relatively flat, given that the crown and head were carved as one piece. The strands of hair that cannot be covered by the crown were also carved.

Figure 7.

Brick carving of a Mazu statue (collected by the Taiwan folklore researcher Lee Yi-hing). Source: Author’s photograph.

The silk shawl on the shoulders of Mazu, with a silk ribbon that ends slightly below the shoulders, and cloud-shaped shoulder decorations (cloud shoulder) at the hem of the garment that covers the front, back, and shoulders, can be seen in the statues of Mañjuśrī Bodhisattva, Avalokiteśvara Boddhisattva, and other goddesses before the Song Dynasty. In addition to the decorative function, the cloud shoulders are used to highlight the special status of the wearer in the celestial world and in folk religions.

Mazu’s footwear is not as clearly represented as the primary costume; only the toe part of the shoe is exposed. People now are more likely to believe that, firstly, Mazu’s pointed and upturned shoes embody boats on the sea, and secondly, Mazu’s feet are the so-called “three-inch golden lotuses (三寸金莲)” influenced by the custom of foot-binding in the Song Dynasty. As Mazu’s followers, such as those at the Nanzi Palace and Shuangci Temple, believe that Mazu’s shoes have the spirituality and energy of the statue, Mazu’s shoes are preserved in many temples. “The notion that a man may be bewitched by means of the clippings of his hair, the parings of his nails, or any other severed portion of his person is almost world-wide... the general idea on which the superstition rests is that of the sympathetic connexion supposed to persist between a person and everything that has once been part of his body or in any way closely related to him,” noted British scholar Fraser (1854–1941) in Chapter 21 “Tabooed Things” of The Golden Bough (Frazer 2006). The clothes, headscarves, and Mazu shoes that are replaced from the Mazu statue are considered by the believers to be carriers of the Mazu Holy Spirit after the invocation ceremony. They regard them as guardian objects for their families and themselves.

Foot-binding in the Five Dynasties (907–960) and Song Dynasty first began among the court dancers and was initially only associated with dance. In this context, the tradition was followed by a small number of dancers of the department in charge of dancing and music for the enjoyment of men. Most Northern Song (960–1127) women were mainly natural-footed, and foot-binding was typically rare in this period. For example, the shoe tips revealed under the skirts of the maids carved in the Song tomb in Luxian County have a sharp and upturned shape. This outwardly curved tip is a mere decoration or style of the shoe, and the feet do not extend into the curved part, so it cannot be inferred that the women’s feet had been wrapped to be slender. Based on this, the archetypal symbol for Mazu’s shoes in the early times can be presumed to be in the pointed and upturned style.

The magic weapon held by Mazu is a conventional symbol, symbolizing a magical power and status of the deity. Gui, a jade tablet, is a ritual instrument used in ancient times for secular rituals and oaths, and is also a symbol of hierarchy when meeting the emperor. Tablets of varied sizes were used to reflect the hierarchical identities of dukes or princes under the emperor, while various names were used to highlight the power given to ones holding the tablets, with different shapes and patterns demonstrating other symbolic meanings. During the Song Dynasty, the gesture of Mazu’s statue when holding Gui must have been the arching of the hands in front of the chest, covered by a scarf, which also constitutes the symbolic gesture of the archetypal Mazu. Other items held by Mazu were added after she had more responsibilities. For example, Ruyi (scepter and talisman) originally served as both a “scratching stick” and hu, a tablet held by ministers when meeting the emperor, and later, it embodied good fortune and protection from evil spirits, carrying a wish for happiness and peace. In addition, it was also a symbol of power and wealth. In the statues from the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Mazu is commonly seen holding a Ruyi or tablet with one hand (usually the right hand), with her arms separately rested on both sides of the round-backed armchair instead of being put together in front of her chest.

7. Conclusions

In the history of religious and cultural representations, Mazu is an interesting case because she exemplifies certain important aspects of Chinese cultural traditions. Mazu provides the opportunity to consider and analyze the pattern of human folk heroes or otherwise important local people being remembered, memorialized, and ultimately deified. In her case, this process of deification continues until she becomes a kind of universal Mother Goddess. While this pattern of the deification of mortals may be well known within the study of Chinese and East Asian cultural traditions, it provides an alternative model and example for the study of goddesses globally and in general. This helps us to understand and to think through the meaning of goddesses as representations. In other cultural traditions, there may be no goddesses of this type; goddess might instead be cosmic, celestial, or transcendental in ways that seem far removed from the daily life of mortals. Mazu is a figure who develops directly out of secular and local traditions. Her development toward the international and universal was a complex historical process. She also offers an example of the variety of human expressions in religious traditions that connect the divine to the mortal in personified form, such as the avatāra traditions in Hinduism, Bodhisattva doctrines in Buddhism, or the incarnation theology of Christianity. That religious and cultural traditions come to regard some humans as special and ultimately divine does not follow a single style of historical development. Mazu is also an interesting case in her own right as a deity whose representations survive syncretism and other processes in which she becomes fused with, combined with, or identified as another cosmic or entity. Even in these cases—as with Funadama and Mary—Mazu tends to keep her identity intact.

The visual elements of the artistic archetypal symbols of Mazu statues and images do not possess concepts and connotations in and of themselves. However, when they are incorporated into the spatial structure of Mazu art, the expressive techniques and forms of the statues and images have become permeated with the collective aesthetic imagery, subjective concepts, and emotional investments of the artisans and believers, and thus become artistic symbols in their inner world that are full of specific meanings. This artistic symbol is an expressive form that has survived thousands of years and has been distilled from the oral narratives of the public, history and culture, and the accumulated national mentality, and “all it can do is objectify or formalise experience so that it can be grasped by rational perception or intuition” (Langer 2006).

In folk beliefs, the archetypal symbol of Mazu statues and pictorial art is not a form of visual representation in the simple sense of the word, nor is it merely a tool to engage the people and the deity in communication. It carries the faithful’s’ search for the meaning of life, their hope for a better life, and the enrichment of their spiritual world. As the material carrier of Mazu culture, the correct construction, modern presentation, and rational dissemination of the archetypal artistic symbols of Mazu images and statues are necessary for the effective transmission and protection of the intangible cultural heritage of Mazu beliefs and customs.

The cultural and symbolic implications of the Mazu archetypal art symbols go far beyond the figurative and morphological Mazu statues and images themselves. These symbols can not only enhance the visual recognition of Mazu’s image, but also penetrate the barriers of language and geographical boundaries, evoke the memory of overseas Chinese of their hometown, become their spiritual and emotional bond, and promote friendly exchanges between people from all over the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Z.; Funding acquisition, B.Z. and X.S.; Project administration, B.Z.; Resources, H.L.; Supervision, X.S.; Writing—original draft, B.Z. and H.L.; Writing—review and editing, B.Z. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 14CG131; 20BG119; 21BG106.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | For the many powers and legend attributed to her, see Clark (2006); Boltz (2008); Yuan (2006). |

References

- Blussé, Léonard. 1979. Chinese Trade to Batavia during the Days of the VOC. Archipel 18: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltz, Judith Magee. 2008. “Mazu”, in The Encyclopaedia of Taoism. Edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. Abingdon: Routledge, vol. II, pp. 741–44. ISBN 9781135796341. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Xiang, and Huobo Xu. 1996. Cai Xiang ji. Collated by Yining Wu. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House, vol. 21, p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Hugh. 2006. The religious culture of southern Fujian, 750–1450: Preliminary reflections on contacts across a maritime frontier. Asia Major 19: 211–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, Kenneth. 1993. Taoist Ritual and Popular Cults of South-East China. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Lisheng. 1996. Chinese Temples in Thailand. Bangkok: Thailand Datong Press Co., Ltd., p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Duyvendak, Jan Julius Lodewijk. 1938. The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century. T’oung Pao 34: 341–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dy, Aristotle C. 2014. The Virgin Mary as Mazu or Guanyin: The syncretic nature of Chinese religion in the Philippines. Philippine Sociological Review 62: 41–63. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, James George. 2006. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Translated by Peiji Wang, Yuxin Xu, and Zeshi Zhang. Beijing: New World Press, p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, Northrop H. 1971. Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 99. First published 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Akiyoshi. 2008. From Chinese Mazu to Japanese Funadama Myojin. Historical Review of Transport and Communications 66: 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, Akiyoshi. 2021. Mazu Worship in East Asia and Funadama Worship in Japan. Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History 223: 97–148. [Google Scholar]

- He, Liyong, and Dian Zheng. 2014. Investigation on Cultural Heritage Resources of Traditional Costumes and Customs in Fujian and Taiwan. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Yuhua. 1990. The Fusion of Religions—Mazu and KAY-SASAY in Batangas. Edited by the Federation of Filipino-Chinese Youth. Manila: Federation of Filipino-Chinese Youth, p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Weitan. 1990a. Mazu Bibliography. Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Weitan. 1990b. Mazu Cultural Resources. Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House, p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Weitan. 1990c. The Origin of the Name “Mazu”. Fujian Academic Journal 3: 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustav. 1978. Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 15: Spirit in Man, Art, and Literature. Edited by Gerhard Adler and Richard Francis Carrington Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, Susanne K. 2006. Problems of Art. Translated by Shouyao Teng. Nanjing: Nanjing Press, p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Bozhong. 1997. “God of Countryside”, “God of Public Affairs” and “God of Maritime Merchants”—On the Evolution of Mazu’s Image. Journal of Chinese Social and Economic History 2: 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Meirong. 2008. The Explicit and Concealed Image of Mazu in Taiwan. Taiwan Mazu Culture Exhibition. Taipei: Feiyan Printing Co., Ltd., pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Zuliang. 1989. Mazu. Fuzhou: Fujian Education Press, p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Mazu Temples Worldwide Editorial Department. 2005. Mazu Temples Worldwide. Macao: International Yanhuang Culture Press, Preface, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, Wai-ming. 2020. The Shintoization of Mazu in Tokugawa Japan. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 47: 225–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Wai-ming. 2021. Chinese Gods with Japanese Soul: Localization of Chinese Folk Religion in Tokugawa Japan. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Yuan. 1988. Puyang Bishi. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House, p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Ruitenbeek, Klaas. 1999. Mazu, the patroness of sailors, in Chinese pictorial art. Artibus Asiae 58: 281–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Mely G. 1991. The social and cultural dimensions of the role of ethnic Chinese in Indonesian society. In Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 113–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xie, Zongrong. 2008. The Divinity and Art of Statue and Image of Mazu. Bulletin of National Museum of History 176: 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Xiaowang. 1993. The Origin of Folk Beliefs in Fujian. Fuzhou: Fujian Education Press, p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Congjian. 1993. Shuyu zhouzi lu. Collated by Sili Yu. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 8, p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Haiwang. 2006. Mazu, Mother Goddess of the Sea. In The Magic Lotus Lantern and Other Tales from the Han Chinese. World Folklore Series; Westport: Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 9781591582946. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Shaocong. 1998. Emigrants on the Eastern Ocean Route: A Comparative Study of Taiwan and the Philippines in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Nanchang: Jiangxi University Press, p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xie. 1981. Investigation of the Eastern and Western Oceans. Collated by Fang Xie. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 9, p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Ying, and Zhongzhao Huang. 2007. Chong Kan Xinghua Fu Zhi. Collated by Jinyao Cai. Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House, vol. 25, p. 665. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |