Abstract

This essay examines various aspects of how Moses was represented as a Christian in artistic depictions of the Transfiguration produced during Justinian’s reign (527–565), particularly discussing mosaics in the apses of the Church of Sant’Apollinare and St. Catherine’s Monastery. First, this essay demonstrates the existence of an earlier type of the Metamorphosis, the St. Sabina-Brescia Lipsanotheca type. Second, this essay focuses on the exegetical tradition of the Transfiguration, which, until the first half of the fourth century, was relatively mild, but was later aggravated by Christian writers during the Theodosian Dynasty. Ultimately, a new type of Transfiguration was created, of which the central theme was the creation of a Christian Moses. The motivation behind this new type was the contradiction attributable to Maximian, the archbishop of Ravenna, the contradiction between his typological iconography visualized in the sanctuary of the Church of San Vitale and Justinian’s severe persecution against the Jews. This contradiction was dissolved through the creation of an image of a Christian Moses in the Transfiguration mosaics in the apses of Sant’Apollinare.

1. Introduction

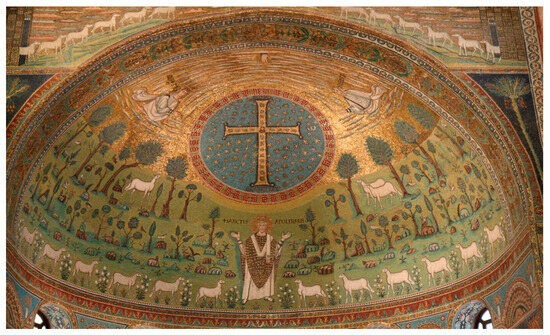

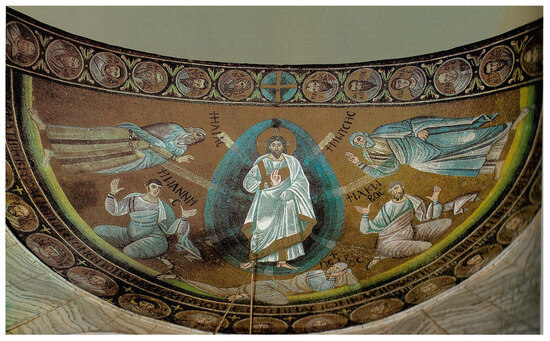

This essay examines how Moses was represented as a Christian in artistic depictions of the Transfiguration produced during Justinian’s reign (527–565). The Justinian’s era witnessed the creation of several apse mosaics of the Transfiguration, with only two of them being extant icons.1 The first icon is an image in the Basilica di Sant’Apollinare in Ravenna-in-Classe, consecrated in 549 and located close to the city of Ravenna (Figure 1).2 The second one is in the church of St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai, built between 548 and 565 (likely closer to 565) (Figure 2).3 Another mosaic was located in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, which was rebuilt in June 550, but destroyed later.4 Andreopoulos suggests that the mosaic was similar to the Transfiguration illumination presented in the Paris Gregory manuscript, which dates to the late ninth century. The argument presented in this article will primarily focus on the Transfiguration apse mosaics located at Classe and Sinai.

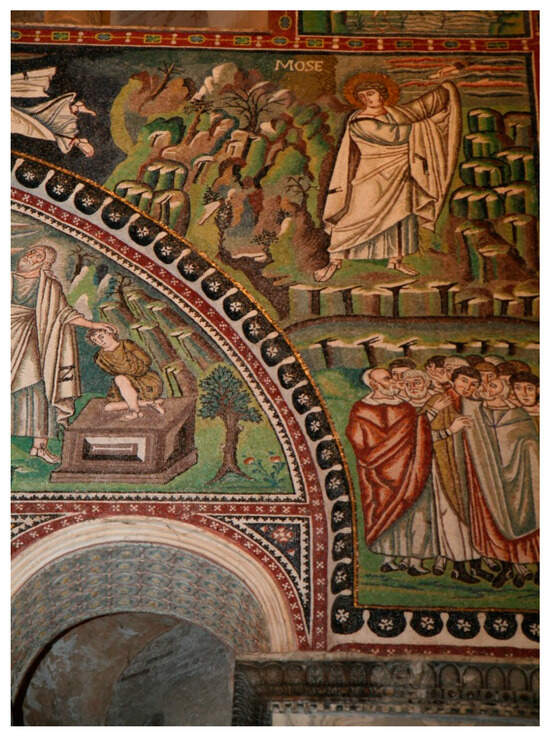

Figure 1.

The Transfiguration, the apse mosaic in the Church of Sant’Apollinare, Ravenna-in-Classe, Italy, 546–549. Photo by the author.

Figure 2.

The Transfiguration, the apse mosaic in St. Catherine’s Monastery, 548–565. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

To date, most studies on these two Justinianic mosaics have been unsatisfactory as they never attempted to analyze the complete program of Transfiguration images depicted on the apses. Andreopoulos’ viewpoint reflects more or less this kind of status quo exaggeration, whereby the apse image at Classe “is not a Transfiguration representation, but rather a composite complex synthesis that includes many elements” (Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 106, 117–25).

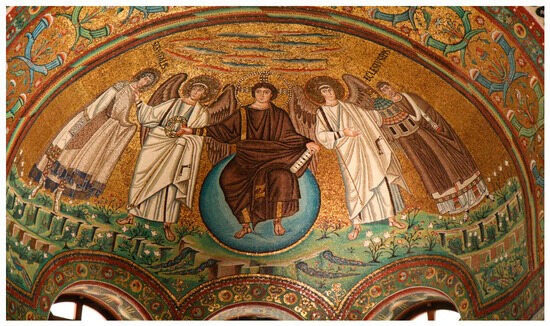

Additionally, previous studies have shown little interest in why the Justinian period needed those Metamorphosis apse images. In the apse image of Sant’Apollinare, Dinkler focuses on the glorified cross centered in the starry universe by emphasizing it as the Parousia or Secundus Adventus, without its specific historical motivation, referring to both the Italian artistic tradition of the luminous cross and the patristic exegetical tradition; moreover, he does not forget to add the meaning of the Adventusliturgie to the Sant’Apollinare apse mosaics.5 Both Deichmann and Müller do not differ much from the hermeneutic position of Dinkler, who sees the main motif of the apse mosaics of Classe as the Wiederkunft Christi (Deichmann 1969, pp. 261–77; Müller 1980, pp. 11–50); in his study, Müller added Christological, soteriological, and apocalyptical meanings. Of course, the Church Fathers already had the exegetical tendency to attribute the Second Advent to the Transfiguration and the luminous cross; however, this kind of earlier exegesis never proves itself to be a decisive clue in explaining why the Metamorphosis apse image appeared in the sixth century and not earlier. Furthermore, as Pincherle pointed out appropriately (Pincherle 1966, p. 518), it is within Dinkler’s orientation that the hand of God, the three disciples, and Moses and Elijah become simple decorative accessories, losing “ogni ragione d’essere” (every reason to exist). As shown in the study by von Simson, it would be more correct to consider that the theme of the Second Epiphany fits the apse mosaic of San Vitale, rather than that of Sant’Apollinare (Von Simson 1948, pp. 33–36); in the apse of San Vitale, the second person of the Trinity, who appears seated upon an awe-inspiring globe, holds a scroll with the seven seals (Rev. 5:5) in his left hand and distributes with his right hand the crown of glory to St. Vitalis, who is presented by an angel (Figure 3). Also, the Eucharistic emphasis of Montanari on the Sant’Apollinare apse is only acceptable in the sense that the liturgical reference is always part of the crucial meaning of the apse; his view, however, does not reveal the historical origin of it (Montanari 1982, pp. 99–127).

Figure 3.

Christ seating on a globe, the apse mosaic in the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, 546–548. Photo by the author.

From a visual perspective, the two representations of the Metamorphosis at Classe and Sinai appear different. However, it can be argued that these apse representations contain, among other things, a common principal theme: the making of a Christian Moses, which is the main focus of the current study. This event comprised three steps. First, I will try to distinguish an earlier style of Transfiguration of the fourth to fifth centuries from the later type of the sixth-century Metamorphosis. In the earlier Transfiguration image, Jesus was depicted as ontologically similar to the two prophets, Moses and Elijah, whereas in the Justinianic Transfiguration icons, the visualization of the ontological pre-eminence of Jesus was the indispensable norm.

In the second step, I examine the exegetical tendencies of Christian writers from the third to fifth centuries regarding this Transfiguration. According to the exegetical tradition until the Constantinian Age, the old promise of theophany was realized through the Metamorphosis, and Moses and Elijah were regarded as Christian figures. Nonetheless, Christian writers of the Theodosian Dynasty developed a new metaphor in which Jesus was asserted as the master and the two prophets were denigrated as servants. However, the new metaphor was not sufficiently effective to create an image similar to the Justinianic Transfiguration.

The final step is destined to elucidate the politico-religious, exegetical, and ecclesiastical origin of the two mosaics of Transfiguration of the sixth century: the visualization of the obedience of the prophets, the depiction of ‘censored’ Peter the apostle and St. Apollinaris as ‘the new prince’ of the apostles, the theme of the Christian Moses visualized in the Ravennate type or the Justinianic type of Transfiguration, and ultimately, the reaction of the emperor Justinian concerning the mosaics of the Sant’Apollinare apse and San Vitale.

2. Two Stylistic Types of the Transfiguration: The St. Sabina-Brescia lipsanotheca Type and the Justinianic Type

André Grabar wrote that the apse mosaic in the basilica at Mount Thabor was an antecedent type to the mosaic at Mount Sinai.6 Without offering any argument, he simply assumed the two mosaics were almost homogeneous. No further reasonable foundation exists for Grabar’s conjecture that the apse mosaic of Mount Sinai connects directly with that of the basilica on Mount Thabor. An archaeological survey by A. Ovadiah provides some information about the basilica of Har Thabor, which dates from the fourth or fifth century and consists of three apses, but nothing is known about its mosaic.7 Grabar presumed that these three apses were individually consecrated to the three figures in memory of the three tabernacles that Peter asked to build.8

Contrary to the assumption of Grabar, the visual representation of the Transfiguration in the basilica on Mount Thabor was not similar to the apse mosaic of Mount Sinai, but resembled both the wooden door panel in the Church of St. Sabina (Figure 4) and the Brescia Casket (Brescia lipsanotheca) (Figure 5), which are concerned with an earlier visual version of the Transfiguration because of their lack of the ontological superiority of the centered Jesus and the symbolism of light in the visual style, as will be demonstrated.

Figure 4.

The Transfiguration, door panel from the Church of St. Sabina, created shortly after 432. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.

The Transfiguration, on the left of the center row, Casket of Brescia (Lipsanotheca Brescia), Italy, fourth to fifth centuries. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

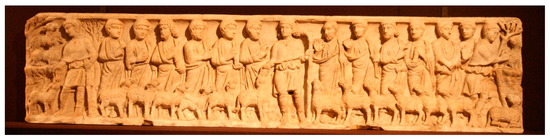

The dating of the wooden door panel is evident, as the Church of St. Sabina was consecrated shortly after 432, and the ivory Brescia Casket dates to approximately the fourth or fifth century.9 The images on the wooden panel and on the ivory casket have been frequently identified as showing the Metamorphosis, even though this opinion is far from consensus.10 To identify their themes, their structure should be compared with that of the traditio legis, as this structural similarity has been the object of scientific discussion.

The traditio legis, which literally means ‘handing over the law’, is an artistic stereotype where Jesus, flanked by two apostles, gives the law to Peter; for this reason, this rendering has also been called ‘Christ the lawgiver’ or ‘Christ and two apostles’ (Figure 6). According to J. Beckwith, a similar mosaic at Santa Constanza (Figure 6) was located in the principal apse of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, built between 319 and 329.11 The first stylistic principle of the traditio legis is Jesus’ centered position; he is always flanked by two apostles. This practice is clearly followed on the St. Sabina wooden panel and also on the Brescia lipsanotheca, which has tempted Delbrueck, Spieser, and Jeremias to consider the door panel to be a form of traditio legis (Delbrueck 1952a, pp. 139–45; Spieser 1991, pp. 63–69; Jeremias 1980, pp. 78–79). However, while there is no doubt that placing Jesus in a centered position is a necessary condition for the expression of the traditio legis, it is questionable whether this alone is sufficient evidence to identify an image as having been inspired by it.

Figure 6.

Traditio Legis, Santa Constanza, Rome, circa. 350. Photo by the author.

A considerable difference between the style of the traditio legis and the door panel should be highlighted: on the panel in the Church of St. Sabina, there is no specific hint of Jesus’ ontological superiority. The absolute supremacy of Jesus is the inevitable norm of the traditio legis, or ‘Christ and two apostles,’ in which his authority is visually expressed in various ways. For example, in Santa Constanza, Christ, encircled by an aureole, dominates the scene. He is facing forward with his right hand raised up and his left hand giving the law, standing on or in paradise, from which four rivers are flowing (Figure 6).

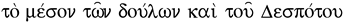

Furthermore, in the niche of the sarcophagus of Iunius Bassus, the enthroned Christ flanked by two apostles is depicted treading on the personified universe (Figure 7); it is doubtless that some observers may consider this a primitive description of Logos Christ or an earlier visual version of the later Pantocrator Christ. The front frieze of a sarcophagus in Arles (Figure 8) enlarges the scene to include the other apostles and has a similar scheme to the previous examples. On a medallion representing Constantine II flanked by his two brothers, the first Augustus is represented with an aureole around his head and he is placed in a higher position (Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Traditio Legis, Iunius Bassus’ sarcophagus, Vatican Museum, 359. Photo by the author.

Figure 8.

Christ and the apostles based on the Traditio Legis, Musée Lapidaire of Arles, France, 375–400. Photo by the author.

Figure 9.

Constantine II and his two brothers, a silver coin (13.45g) minted in Siscia in 338 by Constans. Legend: FELICITAS PERPETVA, BNF Cabinet des Médailles, Paris. Photo by the author.

This kind of imperial coin and the traditio legis were established around the same time, in the first half of the fourth century, which gives another reason as to why the style of the traditio legis was so widespread. In contrast, the sarcophagus at Classe (Figure 10) replaces the direct depiction of Jesus with a Christogram, a symbol that indicates Christ’s victory over death and raising the dead to eternal life or resurrection, which is represented by two flanking peacocks.

Figure 10.

The sarcophagus of Archbishop Theodorus, the Church of Sant’Apollinare, Ravenna-in-Classe, Italy, fifth century. Photo by the author.

Thus, the ontological eminence of Jesus Christ, in terms of paradise (Figure 6 and Figure 8), the personified universe (Figure 7), and Christological symbols (Figure 10), is an indispensable and absolute norm in the plan and visual vocabulary of the traditio legis and of ‘Christ and two apostles.’ No such a thing is found, however, in the image on the St. Sabina door panel.12 Furthermore, on the wooden panel, the aureoles around the head of the two flanking figures implicate their ontological equality to Christ rather than a hierarchy, an equality supported only by Luke in his account, as he states that they ‘appeared in glory’ ( , Luke 9:31).

, Luke 9:31).

, Luke 9:31).

, Luke 9:31).Hence, the current author, in contrast to Delbrueck, Spieser, and Jeremias, is not inclined to consider the image on the door panel to be part of the style of the traditio legis. A more reasonable choice is opened upon seeing an earlier style of the Metamorphosis on the door panel in question.13 If it is accepted that the panel in St. Sabina does not belong to the traditio legis style, but rather represents an earlier version of the Metamorphosis, the scene on the Brescia Casket seems all the more so. To determine whether the Brescia lipsanotheca is an earlier representation of the Transfiguration, let us turn to the symbolism of light in the Justinianic apsidal mosaics, a symbolism that is combined in the plan of the traditio legis.

In the apse mosaics of Justinian’s reign, another stylistic element, a luminous clipeus (central circle) or mandorla, accentuates the magnificence of the transfigured Jesus and implies the inferiority of Moses and Elijah. The clipeus in the Transfiguration of Sant’Apollinare contains a multitude of twinkling stars—99 of them—which symbolize the universe, and a cross covered with jewels shines in their midst (Figure 1).14 The shining cross in the clipeus full of stars refers to the cosmic Logos. This composite, abstract cosmic Logos creates an infinite ontological distance between the glorified Jesus and the two others, Moses and Elijah. The mandorla in the Transfiguration in St. Catherine’s Monastery must be interpreted similarly (Figure 2). Andreopoulos writes that the mandorla originated from the imago clipeata, a Roman tradition of depicting honorable persons in a clipeus of Sol Dominus Imperii Romani, which has often been interpreted as a cosmic symbol.15 J. Miziolek observed that, in Mediterranean art tradition, a clipeus with eight rays, as in the Sinaitic apse, was frequently used to describe helios (the Sun) (Miziolek 1990, pp. 46–47). If such interpretations are accepted, both the shiny mandorla in the Sinaitic mosaic and the brilliant cross in the starry sky within the stylized clipeus in Sant’Apollinare represent the essentially unlimited ontological superiority of the glorified Jesus, with the two prophets subordinate to him.

Indeed, the apse iconography of the Metamorphosis differs in terms of this symbolism from the scene on the Brescia lipsanotheca. As a result of the absence of the symbolism of light in the image on the ivory Brescia Casket, Delbrueck hesitated to identify it as an image of the Transfiguration; he instead identified it as relating to an apparition of the resurrected Jesus on the Sea of Galilee (cf. Mark 14:28, 16:7; Matt 26:32, 28:7; John 21:1) (Delbrueck 1952b, pp. 32–34). In contrast, this fastidious puzzle motivated Grabar to classify it as an unidentified image (Grabar 1968, Figure 337). The failure of Delbrueck and Grabar to identify the casket scene with the Metamorphosis is due to their adhesion to the tradition of the Transfiguration followed in the sixth century, especially in the case of Delbrueck, who regarded the symbolism of light as a steadfast fixture in images of the Transfiguration over centuries. In other words, they did not consider the unexpected earlier representation of the Metamorphosis in the fourth and fifth centuries; why must an earlier image follow a posterior norm?

The scene on the Brescia Casket is a unique, unparalleled representation of the Transfiguration. The wavy line beneath the feet of the three figures represents a cloud.16 The hand shown in the scene is a common method of representing the voice of God (Mark 9:7; Luke 9:35; Matt 17:5). The scene shows Jesus, Moses, and Elijah without aureoles, but almost homogeneously depicted within the cloud that represents the glory of God, a sign of the ontological similarity of the three glorified figures according to Luke’s account. I prefer to classify the scene on the Brescia Casket as another example, besides the St. Sabina panel, of a primitive representation of the Transfiguration.17

In summary, the St. Sabina panel and the Brescia lipsanotheca must be regarded as earlier representations of the Transfiguration. This reasoning helps us to surmise what the lost apse image of the Transfiguration in the basilica on Mount Thabor looked like. In my opinion, that image was doubtless similar to the representations of the Metamorphosis on the St. Sabina panel and the Brescia Casket, but dissimilar to the apse mosaic at Mount Sinai. As a result, it is reasonable to classify two types of images of the Metamorphosis: one, the St. Sabina–Brescia Lipsanotheca type; and the other, the Ravennate or Justinianic type, which is the style used to depict the Transfiguration in the Church of Sant’Apollinare, the apse of St. Catherine’s Monastery.

The profound obscurity of Christ’s superiority in the pre-Ravennate type originated from the uncritical notion of the time when the two prophets were thought to have appeared almost as homogeneously glorified as the transfigured Jesus. For this reason, it is better to keep in mind the discontinuity of the two types, rather than believing in their continuity, or considering an unprecedented leap from the earlier type to the latter. Therefore, in place of Andreopoulos’ confession stating that “trying to determine the iconographic antecedents of the Sinai mosaic is quite a difficult task” (Andreopoulos 2002, p. 32; 2005, p. 139), I suggest that, in the strict sense of the word, there were no visual prototypes of the Justinianic apse mosaics of the Metamorphosis.

3. The Exegetical Tradition of the Metamorphosis

Concluding his analysis in ‘The New Moses’, Allison writes that the Christian exegetical tradition that makes use of Jewish sources “generally serves to exalt Moses, not to denigrate the lawgiver” (Allison 1993, pp. 131–32). Some texts consider Moses inferior to Jesus, but Allison indicates that Moses’ inferiority is inconsistently expressed in comparisons between him and Jesus. However, this is not the case in the Transfiguration. Early Christian writers who commented on the Transfiguration generally considered Moses as inferior to Jesus, and this tendency was further aggravated in the fifth century (McGuckin 1987). This exegetical tendency does not fit well with the pre-Ravennate, an ambiguous type of the Transfiguration that depicts the ontological similarity of Jesus, Moses, and Elijah. This phenomenon may mean that Christian writings describing Moses as a figure inferior to Jesus in the Metamorphosis were ineffective or insufficient to inspire corresponding images to be produced in the fourth and fifth centuries.

Irenaeus of Lyon clarified that the Incarnated Christ was the Word whom Moses wanted to see in Sinai.18 Moses’ desire to see the face of the Word (Exod. 33:20–23) was satisfied after the Incarnation on the top of Mount Thabor, when the glorified Jesus “spoke face-to-face” with him in the presence of Elijah. Thus, an ancient promise of theophany was realized in the scene of the Transfiguration, and in connection with the realization of this promise, Moses is represented as a Christian figure, a denotation suggesting that he was eager to see Jesus.

According to Origen’s exegesis, the Transfiguration scene was not simply designed to fulfill a theophanic promise to Moses and Elijah, but also an occasion to demand their obedience to the Son, thus, a moment when they were asked to become Christian.19 A shining cloud consisting of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit covers the three disciples, the Gospel, and the Law, as well as the prophets. A voice from the cloud, which may be directed at Moses and Elijah, says: “This is my beloved Son in whom I am well pleased. Listen to him.” For Origen, this voice requested the complete obedience of Moses and Elijah to Jesus, and then that of the three disciples. This kind of theophany originated from Moses’ and Elijah’s desire to see and hear the Son of Man. In this commentary, Moses, the greatest figure in ancient Judaism, is evidently presented as Christian, almost equal to Jesus’ disciples.

Origen also connected the disappearance of two prophets in the last scene of the Transfiguration to the fulfillment of the joining of the Law and the prophecy to the Gospel.20 When Jesus touched his disciples who had fallen face-down on the ground, they looked up, but saw no one except Jesus (Matt 17:7–8). For Origen, the disappearance of the two prophets indicates that Moses, the Law, and Elijah, the prophecy, had become one with the Gospel of Jesus; they were no longer three, but One in the glorified Jesus. Thus, the Law and prophecy were destined to be integrated and fused into the Gospel, and Moses and Elijah were presented as Christianized prophets whose roles were only preliminary to and preparative for Jesus.

On the other hand, Eusebius of Caesarea focused on the final Transfiguration, rather than that which occurred on Mount Thabor. On Mount Thabor, only three of the twelve disciples were deemed worthy of seeing the Kingdom of Heaven during the Transfiguration (Luke 9:28–36); however, “on the consummation of this age”, Eusebius continued, “when the Lord will come with the glory of the Father, neither will Moses and Elijah escort him, nor will three disciples be there, but all prophets and patriarchs and the righteous. And the Lord will take up those who are worthy of his divinity, not to the high mountain but into heaven.”21 There is no suggestion here that Eusebius considered Moses or Elijah superior to the three disciples or the righteous; indeed, he implicitly presents Moses and Elijah as equal to them.

Interestingly, Christian writers became harsher toward Moses during the Theodosian Dynasty.22 While they maintained the previous exegetical tradition that the old promise of theophany was realized through the Transfiguration, and although they still regarded Moses as a Christianized or Christian figure, they developed a metaphor of a master and servants. In this metaphor, the two prophets were denigrated as the latter, and the superiority of Jesus was asserted. It was Ambrose of Milan who first advanced this new exegetical tendency. He highlights Peter’s mistake, denigrating Moses and Elijah through the contrast between master and servant.

Since he (Peter) merely estimated the number of tabernacles to be three, he is rebuked by the sovereignty of God the Father saying: “This is my beloved Son, listen to him”, i.e., saying: “Why do you associate your fellow servants with your Lord? It is my son. Neither Moses nor Elijah, but this is my Son”. The apostle realized his error and fell on his face to the ground, frightened by the voice of the Father and the brilliance of the Son.23

Ambrose then interprets this to indicate that the meeting of the Law, the prophecy, and the Gospel does not reflect the equality of Christ with the servants, but a divine mystery that reveals the eternity of the Son of God.24 Ambrose’s hermeneutical tool, the contrasting of a master and servants, became a decisive method for Christian writers in their interpretations of the Transfiguration during the Theodosian Dynasty. For instance, John Chrysostom similarly explained that Jesus took three disciples to the mountain to show them that his relationship to Moses and Elijah is the same as the one of a master to his servants. The Jews considered Jesus to be a reincarnation of John the Baptist, Elijah, Jeremiah, or of other prophets (Matt 16:14); yet, these prophets are only servants compared with the master, Jesus. The Transfiguration was intended to reveal to the three disciples “the difference between the servants and the master” ( ); it also had the additional importance of teaching Moses and Elijah that Jesus had the “power of death and life” (

); it also had the additional importance of teaching Moses and Elijah that Jesus had the “power of death and life” ( ), and speaking to them about the suffering and the cross that he would encounter in Jerusalem (Luke 9:31).25

), and speaking to them about the suffering and the cross that he would encounter in Jerusalem (Luke 9:31).25

); it also had the additional importance of teaching Moses and Elijah that Jesus had the “power of death and life” (

); it also had the additional importance of teaching Moses and Elijah that Jesus had the “power of death and life” ( ), and speaking to them about the suffering and the cross that he would encounter in Jerusalem (Luke 9:31).25

), and speaking to them about the suffering and the cross that he would encounter in Jerusalem (Luke 9:31).25John Chrysostom once again denigrates Moses and Elijah when he rebukes Peter for asking to establish three tabernacles.

“If you wish”, Peter said, “I will make three tabernacles, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah”. Oh, Peter! What do you say? Did not you separate him (Jesus) a little while ago from the slaves [Mark 14:31]? Do you count him again with the slaves? Do you see how exceedingly imperfect they were before the crucifixion?26

This passage vehemently communicates the contrast between a master and servants, and Chrysostom attributes Peter’s words to ‘his confused thought’ ( ), because, according to Mark and Luke, Peter did not know what to say (Mark 9:6; Luke 9:33).27 Jerome also shares the opinion of Ambrose of Milan and John Chrysostom in regard to their rebuking of Peter for asking to set up three tabernacles.

), because, according to Mark and Luke, Peter did not know what to say (Mark 9:6; Luke 9:33).27 Jerome also shares the opinion of Ambrose of Milan and John Chrysostom in regard to their rebuking of Peter for asking to set up three tabernacles.

), because, according to Mark and Luke, Peter did not know what to say (Mark 9:6; Luke 9:33).27 Jerome also shares the opinion of Ambrose of Milan and John Chrysostom in regard to their rebuking of Peter for asking to set up three tabernacles.

), because, according to Mark and Luke, Peter did not know what to say (Mark 9:6; Luke 9:33).27 Jerome also shares the opinion of Ambrose of Milan and John Chrysostom in regard to their rebuking of Peter for asking to set up three tabernacles. You are wrong, Peter, like the other evangelist witness: you do not know what to say. Do not seek three tabernacles, because there is only one tabernacle of the Gospel in which the law and the prophets are to be summarized. But make three tabernacles, rather one for the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, so that their divinity is one and the tabernacle is in your heart.28

Surprisingly, Cyril of Alexandria repeats verbatim some of the opinions of John Chrysostom. Jesus took his disciples to show them the difference between the slave and the master.29 During the Transfiguration, he taught Moses and Elijah that he had the power of death and life, and they spoke of the suffering, the cross, and the resurrection.30 Nevertheless, Cyril of Alexandria adds a new meaning to the Transfiguration: a symbol of the conversion to the Christian faith of the Jews.

After a voice from the cloud said “listen to him,” there was nobody left but Jesus: for these things what does he say, a stiff-necked Jew who is obstinate and disobedient, and has the heart not being warned? Even though Moses was present, God the Father commanded the holy apostles to listen to Jesus. (…) Then Moses and Elijah departed and only Jesus was present. Accordingly God the Father commanded them to listen to him. It is because he is the end of the law and the prophets. That is the reason why he said this to the Jewish people: “If you believed Moses, you would believe me, for he wrote of me (John 5:46)”.31

To Cyril of Alexandria, Moses is a Christian prophet who prepared the way for Christianity before Jesus and, thus, his descendants should embrace the Christian faith. At the same time, this sermon must be considered in the context of Cyril’s severe persecution of Jews and Hypatia’s death in 415.

In approximately 446, Proclus of Constantinople disparaged the two prophets in the most severe manner, blaming Peter in one of his sermons for insulting the divine things with human opinion by considering the master as equal to the slaves when he asked to make three tabernacles.32 Proclus enumerates in detail a list of points of contrast: Moses was not conceived by the Holy Spirit, nor was Elijah born of the Virgin Mary; they had no precursor, but John the Baptist witnessed Christ; the magi did not adore Moses’ or Elijah’s swaddling clothes, nor did Heaven reveal the genealogy of Elijah; the two prophets did not drive out a legion of demons; Moses struck the sea with a rod, but Jesus walked on the sea, making it passable for Peter; Elijah supplicated to increase the amount of flour that a widow had and saved her son from death, but with only some bread Jesus satisfied several thousand people; Jesus went down to Hades, nullified its power, and saved those who were sleeping.33 In this exhaustive manner, Proclus clearly depicts the ontological distance between Jesus and the two prophets. He then severely scolds Peter: “Do not say, Peter, ‘we will make here three tabernacles’, neither ‘it is good for us to be here’. Do not say mundane, profane and earthly things”.34

Finally, for Proclus of Constantinople, the Transfiguration was intended to reveal in advance the glorified human nature in Jesus’ second coming and, for this purpose, Jesus appeared in front of Moses and Elijah, ensuring that he fulfilled the old promise of theophany.35 Surely, the thoughts of Proclus of Constantinople marked the apotheosis of the exegetical movement that denigrated Moses and Elijah.

The exegetical tradition that persisted until the Constantinian era meant that the realization of the old theophanic promise was used to represent Moses and Elijah as Christian figures. Subsequently, several Church Fathers became even more critical of this, in conformity with the anti-Jewish policy of the Theodosian Dynasty,36 primarily depending on the hermeneutical contrast of the master and the servants to elucidate the ontological supremacy of Jesus and constantly rebuking Peter who, in his confusion, considered Christ to be equal to the two prophets. In those processes, the Church Fathers occasionally added new meanings to the Transfiguration, i.e., that it is a symbol of the Jews’ conversion to the Christian faith or Jesus’ second parousia.

Nevertheless, the Ravennate type of Transfiguration did not appear contemporaneously. All Christian images had been produced under the influence of several factors—political, liturgical, cultural, theological, economic, etc.—sometimes independently, often in combination. For example, the popularity of the Christogram, a principal Christian symbol since the fourth century, did not stem directly from Constantine’s victory at the Milvian Bridge, but rather from the imperial propaganda created through the minting of coins that carried the symbol (Figure 11). Using inductive reasoning, one can conclude from Egeria’s report in her journal that the reason the images of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem were popular on sarcophagi in the second half of the fourth century was due to the influence of the Easter liturgy of the Church of Jerusalem, rather than that of the imperial adventus (Figure 12), even though the latter cannot be wholly neglected.37 Regarding the ‘Twelve Apostles’ type of the sarcophagus (Figure 13), by examining the famous edict, cunctos populos, promulgated by Theodosius in 380 (CTh 16.1.2), and by taking into account Theodosius’ constant political and religious policies,38 the advent of this style can be primarily attributed to the rise of the Christian Empire indirectly under the influence of the pagan artistic model of ‘master teaching pupils’. Noteworthy in this light is that, if depictions of the Transfiguration that featured the cosmic Christ did not exist until the beginning of the sixth century, this was likely due to the lack or absence of sufficient motivations, which will be studied in the following step.

Figure 11.

Constans holding a Chi-Rho monogram (labarum), a silver coin (12.38g) minted in Siscia in 342. Legend: TRIUMPATOR GENTIUM BARBARARUM. BNF Cabinet des Médailles, Paris. Photo by the author.

Figure 12.

Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem, sarcophagus, Vatican Museum, circa. 375–400. Photo by the author.

Figure 13.

Christ (Good Shepherd) and the apostles (twelve sheep), sarcophagus, Vatican Museum, circa. 375–400. Photo by the author.

4. The Origin and Effect of a Christian Moses Portrayed in the Two Justinianic Transfiguration Mosaics

Can we find the motivation for the appearance of the Ravennate Transfiguration during the sixth century? Indeed, it is to be attributed to Maximian, the bishop of Ravenna who realized a serious contradiction between a typological iconography visualized by himself in the sanctuary of San Vitale and Justinian’s anti-Jewish policies; he was to dissolve this inconsistency through the theme of a ‘Christian Moses’ commissioned in the apse of Sant’Apollinare in Classe. For the imperial religious propaganda in the sanctuary of San Vitale, Maximian made use of a double typology, i.d., the Christological typology and the Mosaic typology: in our context, the Christological typology means that Moses is depicted as a typus Christi or figura Christi (antitype of Christ), while the Mosaic typology refers to the allusion of emperor Justinian as a New Moses.39 However, his theological and optical analogy was incompatible with Justinian’s persecution against the Jews. This ideological conflict, therefore, led him to advance a ‘Christian Moses’ in the apse of Sant’Apollinare.

4.1. Mosaics of San Vitale and ‘a Christian Moses’ Depicted in the Transfiguration of Sant’Apollinare at Classe

Maximian, who was enthroned October 14, 546 to the see of Ravenna, consecrated the Church of San Vitale May 17, 548, of which the foundation had been laid in 526 by Ecclesius, one of his predecessors.40 At that time, the city of Ravenna was the imperial center of Italy under the controversies over the Three Chapters and the Gothic war, and Maximian, the general director of the mosaics, had to convey, regardless of interpretation, highly politico-religious significances on the mosaics of San Vitale. A survey of the entire mosaic program of San Vitale is beyond the scope of the current study, which will concentrate primarily on mosaics relating to the depiction of Moses’ life.41 The status quo converges generally on a conclusion that Maximian, portraying Moses’ life cycle, relied on the Christological typology and the Mosaic typology, alternatively or both.

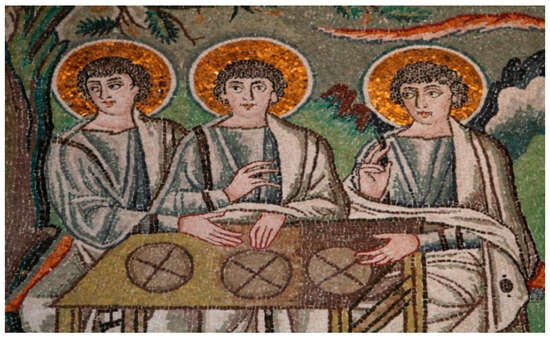

To examine the Christ typology depicted in the sanctuary of San Vitale, one needs to observe the scene depicting the appearance of three angels at Mambre (Gen 18:1–15, Figure 14) and Moses’ facial expression in several scenes summarizing his life (Figure 15). It is remarkable that the three angels have almost identical faces and that Moses’ face is also similarly depicted. Indeed, among the various hermeneutical speculations by the early Christians about the three angels, Maximian chose to interpret that the Trinity appeared to Abraham in the guise of the three angels.42 The faces of the three angels were represented almost identically to express therefore una substantia et tres subsistentiae (one substance and three persons); their identification as the Trinity has been generally accepted, and, according to Grabar’s view, the centered figure’s two-handed gesture represents the normal method of symbolizing the second hypostasis of the Trinity (Figure 14) (Grabar 1968, p. 114).

Figure 14.

Three Angels or the Trinity in Mambre, the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, 546–548. Photo by the author.

Figure 15.

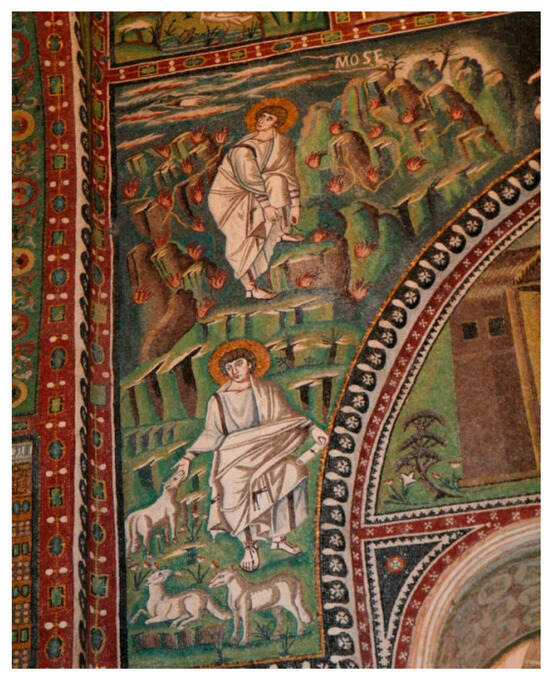

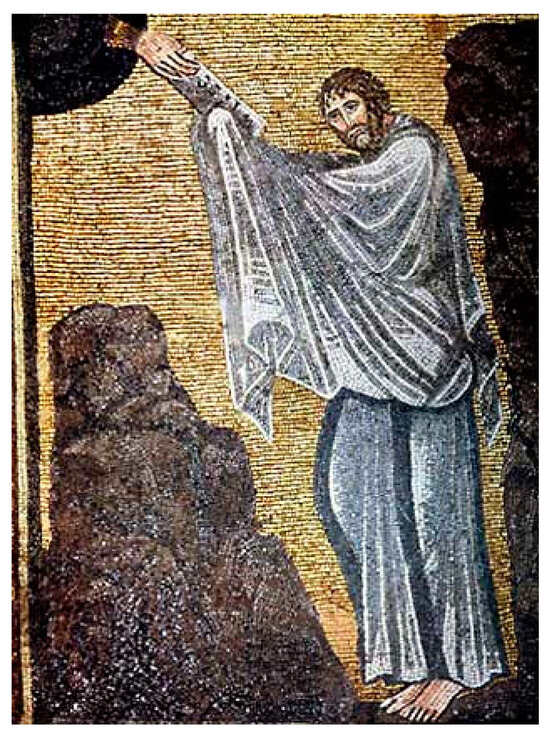

Moses caring for the flock and loosening his sandals in front of the burning bush, the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, 546–548. Photo by the author.

In the next step, the general director had the face of Christ to be borrowed into that of Moses (Figure 15 and Figure 16). Consequently, the face of Moses resembles that of Christ in three sequential scenes: Moses caring for the flock, loosening his sandals in front of the burning bush, and receiving the Law. Furthermore, the first of these series, Moses caring for Jethro’s flock, was designed to remind beholders of the phrase-“I am the Good Shepherd” (John 10:11) and of the Christ–shepherd of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia,43 while the last, representing (the rebellion of) Aaron and the twelve tribes, overlaps with (the betrayal of) the twelve disciples of Christ. In brief, all of these scenes were so intentionally devised that viewers are led to believe that, in the context of the Christological typology, Christ with two other hypostaseis visited Abraham long before Moses, and that the historical Moses prefigured the only begotten Son; consequently, the Mosaic law is only a preliminary step that must be fulfilled by the Gospel of the incarnated Son.

Figure 16.

Moses receiving the Law and (the rebellion of) Aaron and the twelve tribes, the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna, 546–548. Photo by the author.

In addition, Moses’ life series do not exclude political connotations, as per the early Christian literary tradition of describing a Christian emperor as a ‘New Moses’ (Montanari 1995, pp. 641–47). In other words, the iconography of Moses as a shepherd alludes to emperor Justinian, as well as the ‘true Good Shepherd.’ This kind of ambivalence can apply to the mosaic portraying Moses the Lawgiver. The image of Moses, receiving the divine commands, was one of the most favored images found on fourth-century sarcophagi. But Maximian’s variation is to be understood in the context of Justinian’s compilation of the corpus iuris civilis, because the legislation would have been recognized contemporaneously as a restitution of the Mosaic laws; therefore, in this case, the twelve tribes of Israel emerge as a potent symbol of the Christian people of the empire.44

Nevertheless, there is a perhaps evident, although heretofore undiscussed, contradiction in the iconographical typology visualized in Moses’ life series: Maximian’s attempt to cast Moses as the typus of emperor Justinian or intended to render Moses the antitype of the Christ did not go well with the fact that the famous Hebrew prophet’s descendants were persecuted severely under the reign of Justinian.

Justinian’s persecution of the Jews was so harsh and consistent throughout his long reign that it was incomparable with the Theodosian Dynasty’s policies towards the Jews.45 A constitution related to his oppressive policy circulated in 528 (CJ 1.5.17), ordering the destruction of synagogues and the prohibition of their new construction.46 Its application resulted in a revolt in Palestine, which occurred in 529 and was followed by a severe repression; about 20,000 Samaritans were killed and the same number were sold as slaves in Persia and India, while many of them were forced to be converted to the Christian faith or else to flee to Persia, as most synagogues were being destroyed in the region.47 Some years later, Justinian reiterated the conversion of synagogues into churches (Novellae 37).48 According to Procopius, the synagogue of Gerasa, decorated with beautiful mosaics, was converted into a church sometime before 530–531, while the Jewish temple of Boreon in Cyrene, which was claimed to have been erected by Solomon, met the same fate by order of Justinian, and the Jews of the city were forced to convert to Christianity.49 Around 542, the conversion of synagogues into churches was reiterated (Maraval 2016, pp. 261, 319–21).

It is doubtless that Justinian’s antipathy, which was aimed at the descendants of the old Moses, is not compatible with the Maximian’s double typology in Moses’ series of San Vitale. ‘Moses prefiguring Christ’ or the allusion of Justinian to a ‘New Moses’ could only make sense with the anti-Jewish policy of Justinian if Moses, the leader of Jews, were to be rendered as a Christian; under the scenario of Moses becoming Christian, his descendants would follow his example, and the conversion of synagogues into churches and that of Jews into Christian tenets would be theologically right and needed to be as such, and in such case, the emperor, the leader of the Christian world, would deserve to be alluded to a New Moses; on the contrary, if Moses continues to remain Jewish, the comparison of Justinian to a New Moses, strictly speaking, would be absurd since the emperor would be falling into a serious contradiction, that of becoming a New Leader of the Jews whom he himself persecuted.

Maximian was keenly conscious of the conflict between his typological iconography and Justinian’s politico-religious policy. A creative solution was evidently found by the time he consecrated Sant’Apollinare in Classe on May 9, 549, since the Transfiguration mosaic on the apse of Sant’Apollinare, among other things, clearly depicts the creation of a ‘Christian Moses’.

4.2. Obedience of the Prophets Visualized in the Transfiguration Images

The Transfiguration image at Classe is based on Luke’s account on the departing of Moses and Elijah (Figure 1). Other optical elements are found in all of the Synoptic Gospels: their dialogue with the glorified Jesus, represented by their hand gestures (Luke 9:30–31; Matt 17:3; Marc 9:4); the shining cloud covering them, depicted in various colors (Luke 9:34; Matt 17:5a; Marc 9:7a); and the voice of God, represented by the high, centered hand (Luke 9:35; Matt 17:5b; Marc 9:7b). All of these visual elements, along with the luminous clipeus containing the cross, are designed to highlight three stages of Christ’s teaching, the obedience and the conviction of the two prophets, and their departure as obedient and convinced Christians.

In the commentaries on the Transfiguration of Ambrose of Milan and Cyril of Alexandria, the dialogue of Moses and Elijah with the glorified Jesus is not considered a discussion between equal subjects, but as a teaching offered to the two servants by the master on the power of death and life. The luminous clipeus was in fact included to remind the viewers of such teaching, partly because the cross itself in the clipeus is a symbol of resurrection, victory over death, and partly because the composite of the clipeus containing the cosmic Logos–Christ is so overwhelming from the beholder’s position that she or he is inclined to consider the Transfigured Christ as the master teaching the flanking prophets, not an equal partner in the dialogue or colloquy. The bust of Jesus in the medallion placed at the intersection of the cross offers a suggestion of the Crucifixion or the Passion of Christ. The ontological majesties of the glorified Jesus are definitively confirmed by some of the expressions used: the words salus mundi (‘salvation of the world’) located under the vertical axis of the cross; Christ’s earlier symbol,  (

( , Jesus Christ, Son of God, Redeemer) upon it; and an alpha and omega at either side of the horizontal axis.

, Jesus Christ, Son of God, Redeemer) upon it; and an alpha and omega at either side of the horizontal axis.

(

( , Jesus Christ, Son of God, Redeemer) upon it; and an alpha and omega at either side of the horizontal axis.

, Jesus Christ, Son of God, Redeemer) upon it; and an alpha and omega at either side of the horizontal axis.Concerning the voice of God, its depiction as a high, centered hand in the Ravennate mosaic is very peculiar since it is generally nonexistent in later Transfiguration representations.50 Origen interpreted it initially as a demand for the perfect obedience of Moses and Elijah to Jesus, and secondly, that of the disciples. This kind of conception was applied to the apse mosaic in a striking manner. From the viewer’s perspective, the primary audience of the divine voice is not the lambs, but obviously the people. Thus, Moses and Elijah, depicted as busts of human figures, are the primary audience of the voice of God and his order for complete obedience: “This is my beloved Son in whom I am well pleased. Listen to him” (Matt 17:5b; Luke 9:35; Marc 9:7b). In such calculated planning, the two great prophets of old Judaism were requested to be obedient to the Son of God; in other words, to be Christian. Their obedience to the divine teaching and request is impressively portrayed through the gesture of their hands and fingers. Moses, on the left, stretches out his right hand, a gesture which symbolizes the moment of divine teaching from heaven and the glorified One. His three outstretched fingers refer to his obedience and conviction to that teaching, i.e., the divine unity of the Three Persons or Jesus’ resurrection after ‘three days’ of his crucifixion (cf. Luke 9:31, exodos), or alternatively both. Elijah, on the right, indicates the acceptance of the two natures of Christ by two outstretched fingers. The three disciples represented as sheep remain merely a second audience.

It has previously been mentioned that, in the exegetical tradition of the Transfiguration, the disappearance of the two prophets generally refers to the fusion and integration of the Law and the prophecy with the Gospel. The Metamorphosis mosaic at Classe, among all Transfiguration representations created up to the sixteenth century, is the only case in which the departure or the disappearance of the two prophets is depicted. Truly, it is the only artistic representation that depicts the end of the preliminary and preparative role of Moses and Elijah through the realization of the old promise of theophany. In summary, the Transfiguration apse mosaic at Ravenna-in-Classe presents the theophany as converting the prophets to Christianity through three stages: being taught by the glorified One, obeying him and becoming convinced Christians, and disappearing as such.

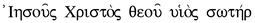

The Metamorphosis image of the Sinai apse illustrates only two out of the three: the teaching of the glorified Jesus and the obedience or the conviction of the prophets (Figure 2). Jesus’ right hand is centered on the breast with three outstretched fingers; this gesture implies the teaching of the doctrine of both the Trinity and the resurrection; the mandorla circling Jesus indicates his divinity, while the depiction of Jesus’ figure as a human being refers to his humanity. Moses on the right and Elijah on the left are showing obedience and conviction to the divine lesson of the two natures of Christ and the Trinity, respectively with the two and three fingers of their lifted right hands. The omission of the hand of God from the Sinai apse does not raise any intriguing issue since the divine teaching through the voice from heaven is replaced here exclusively by the three outstretched fingers of the chest-centered right hand of Jesus.

4.3. The Depiction of Censored Peter in the Two Apses

The Ravennate apse image contains a delicate censor applied to Peter. With conformity to the criticism of Christian writers on Peter, his ‘confused thought’ or ‘earthly speech’ is intentionally omitted from representations on the apse. Thus, in the image at Classe, the three lambs, symbols of the three apostles, Peter on the left side and John and James Major on the right side, are merely gazing up at the luminous cross in the clipeus deprived of the ability to talk (Figure 1). The purpose of this allegorical symbolism is to completely prevent the viewers from alluding to Peter’s foolish statement (Luke 9:33b). At the same time, Maximian, the general director of the Transfiguration image sets Peter in Paradise, lets him observe face-to-face the cosmic glory of the glorified One, makes him confirm the ontological distance between the glorified Jesus and the two prophets, and finally leads him to realize and correct the indiscretion he committed at Mount Thabor. Since Peter, whose name is recalled with the epithet ‘divine’ (divinus Petrus Apostolus) in the first constitution edited in the Justinian Code, was rendered as dispossessed of the ability to talk, there is no problem for the two other apostles, John and James Major, to be represented as lambs under the same form after him.51

For Andreopoulos, who interprets the overall apse image in the context of the last days, the depiction of the three lambs in paradise holds inevitably the synthetic connotation between the Transfiguration and the eschatological vision (Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 119–25, especially, p. 124). Deichmann wants to see the imitatio sacrificii Christi in the symbolism of three lambs, attributing the notion of scapegoat to them (Deichmann 1969, p. 267). Such interpretations are not to be totally excluded, but Andreopoulos and Deichmann should have paid more attention to the fact that the three lambs are depicted without aureole, whereas St. Apollinaris is depicted as a martyr with a haloed head. In other words, I think the three lambs are neither depicted as martyrs, nor represented as witnesses of the eschatological vision. Pincherle takes into consideration why they are not haloed, but leaves it nearly unanswered.52 The crucial key to this enigma must be in our aforementioned perspective of the censored and corrected Peter. Andreopoulos and Deichmann’s views are certainly superficial in the sense that it does not offer any suitable explanation for the reason as to why absent is the talking scene of Peter in the Justinianic Transfigurations, which occupies a considerable importance in the Transfiguration narrative of the three Synoptic Gospels and thus never fails to be visually represented in the later Transfiguration images.

According to Agnellus, chronicler of the Church of Ravenna of the ninth century, Maximian made a copy of the Bible from Genesis to Revelation, emending very cautiously the text according to Augustine and the Gospels which Jerome had sent to Rome.53 In this report, we explain the influence of Jerome on Maximian’s censored Peter. Simultaneously, we cannot completely exclude the influence of Ambrose of Milan, since Maximian was also from the West, and still opened is the possibility of his exposure to some Eastern writers who vigorously criticized Peter and emphasized a metaphor between a master and servants as well as the denigration of Moses and Elijah.

Now, let us turn our attention to the depiction of St. Peter in the Sinai apse. Strikingly, Peter is here depicted sleeping, lying down on the ground, while the two other apostles are awake, kneeling with astonished expressions (Figure 2). This is an abnormal depiction that clearly differs from the biblical texts as, without exception, they all report that Peter asked to build three tabernacles (Matt 17:4; Marc 9:5; Luke 9:33). Such an image of Peter sleeping effects the application of a more severe censor over Peter, depriving him of his consciousness so that his ‘confused thought’ or ‘earthly speech’ that equated Christ to the two prophets could not be uttered. This kind of expurgation gives us a strong hint that the director of this scene was conscious of the critical exegetical tendencies of the fourth and fifth centuries’ Christian writers. According to Procopius, the church of Sinai was erected and dedicated to the Mother of God by Justinian.54 Weitzmann is certain that the Sinai apse mosaic could have been constructed by skilled craftsmen and clerics from the Byzantine capital who were sent for by Justinian (Weitzmann 1965, pp. 11–12 and 16; 1966, p. 405). On the basis of the imperial policy, such indications make our historical orientation more persuasive than Elsner’s mystic view point of interpreting Peter’s ‘unusual’ sleeping depiction as a metaphor for the so-called ‘night of sensitivity’.55 Andreopoulos applies more widely the notion of the mystical ascension to the Sinai apse and to the two panels depicting Moses above the apse (Figure 17) (Andreopoulos 2002, p. 28). Obviously, the views of Elsner and Andreopoulos have difficulties in providing a pertinent answer to why Justinian wished to convey a theme from the negative theology for his own politico-religious propaganda. Andreopoulos gives an ‘additional’ meaning—but in my opinion, it seems to be disoriented—to Peter’s position, which is placed on the vertical axis just under the glorified Christ, a position that is a hint to his confession (Matt. 16:16–17) and his identification with the Rock upon which the Church will be built.56 Nevertheless, Peter’s sleeping scene on the Sinai apse must be nothing but another visual version of the censored Peter at Classe. The elusive, puzzling meaning of Peter’s sleeping scene at Sinai and the symbol of the three lambs at Classe can never be attained pertinently without the context of the ‘censoring’ of the Church Fathers during the Theodosian Dynasty.

Figure 17.

Moses receiving the law, St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, 550–565. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The unusual feature of Peter’s position distinguishes the Sinai apse mosaic from the later general Transfiguration iconography, which never fails to depict Peter talking. This peculiar phenomenon can be due to the lack of understanding of the politico-religious origin of the Sinai Metamorphosis image in the later Transfiguration icons. On this point, the Sinai Transfiguration image is closer to that of Sant’Apollinare than the wrongly labeled ‘the Sinai type’ by Andreopoulos, which prevailed in later periods (Andreopoulos 2002, p. 9). The so-called ‘Sinai type’ generally represents Peter talking and thus must be distinguished from the Sinai apse mosaic itself.

4.4. The Depiction of St. Apollinaris as the ‘New Prince’ of the Apostles in the Apse of Sant’Apollinare

It is noteworthy that the visual criticism to the ‘confused thought’ of Peter aims at another significance. To reveal it, our attention should be turned to the image of St. Apollinaris, martyr, founder, and first bishop of the Church of Ravenna, whose figure is remarkably emphasized in the scene. He stands in paradise with a conspicuous posture of orans (one who is praying with the outreached hands) in a pallium of archbishop, just under the vertical axis of the glorified cross, and between him and the cross is inscribed “+SANCTVS APOLENARIS”. Undoubtedly, the artistic representation of St. Apollinaris refers to some particularity of his presence in the whole apse imagery, because among the prophets and the apostles, he alone is depicted as a figure both as tall as the vertical axis of the cross and with a golden aureole around his head. Moreover, striking is the position of St. Apollinaris, who appears in the midst of the twelve lambs, since the location was normally reserved for the master of the twelve apostles (Figure 13), with whom von Simson identifies the twelve lambs (Von Simson 1948, pp. 51–54). Several types of sarcophagus, on which Christ always stands in the midst of the apostles (cf. Figure 8), are known and labeled ‘Christ and the twelve apostles’ in Arles and the Vatican Museum. As for the peculiar image of St. Apollinaris, von Simson, who interprets it as a martyr–imitator of the suffered and glorified Jesus, wishes to see his elevation into the rank of apostleship.57

In a similar view, Pincherle also writes that St. Apollinaris is depicted worthy to be elevated “in the company of the glorious apostles.” (Pincherle 1966, p. 523). Nevertheless, we must go beyond the inspiration that von Simson and Pincherle have on the emphasized feature of St. Apollinaris, because the optical emphasis on the saint corresponds to a figure superior to all of the apostles, rather than being a simple elevation in the rank of apostleship. In reality, St. Apollinaris is depicted as a thirteenth apostle superior to the twelve apostles, all of whom are represented, flanking the haloed martyr, as a form of lamb, the symbol of the censored Peter. Such elevation of St. Apollinaris, especially through the central location, is surely not the first appearance; the sarcophagus of Constantine the Great was laid, beneath the central dome of the Church of the Holy Apostles, in the middle, surrounded by those of the twelve apostles, and it was thus placed in a way that Constantine was worthy to be called ‘the thirteenth apostle’ who surpassed them;58 such an example of Constantinople inspired Maximian with the idea of the thirteenth apostle. The image of the first bishop of Ravenna eventually encourages the viewers into the following slogan: St. Apollinaris deserves to be recognized as the ‘prince of the apostles’ or summus sacerdos,59 while Peter is not qualified to hold the epithet of divinus. Therefore, the ultimate purpose of the imagery of the twelve apostles flanking St. Apollinaris consists of the elevation of the bishop–martyr on the basis of disparaging St. Peter.

Furthermore, the visual elevation of the pontificate of Ravenna into an ecclesiastical supremacy and the belittlement of the Roman see are related to the theopaschite formula of that period.60 The emperor Justinian aspired to impose it, with a strategy in the Western Church of partly strengthening the authority of the episcopate of Ravenna and more seriously urging the Pope Vigilius to condemn the ‘Three Chapters’. Within this context, it is not completely inappropriate to project some criticism toward the theological inconsistency of the pope Vigilius on the censored representation of Peter due to the latter’s theological disorientation; the pope did not accept the decree of Justinian, including the theopaschite or new-Chalcedonian perspective, and was arrested on December 22, 545, by the imperial troops in Rome to be sent to Constantinople, and eventually issued his consent through Jubilatum (called after his first word of his text) on April 11, 548, in Constantinople.

Thus, the glorified image of the martyr Apollinaris reflects the new assignment given to Maximian, archbishop of Ravenna, by Justinian, in favor of the new Chalcedonian doctrine. Being reconsidered in this context, the visually accentuated image of St. Apollinaris has its ultimate concern in promoting the Church of Ravenna to the Mother Church of the Western world, not simply representing Ravenna’s ambition to rank with the apostolic sees, or displaying its rivalry with Rome according to von Simson (Von Simson 1948, p. 57). The ecclesiastical aspiration of the Church of Ravenna was sanctioned by Justinian himself, because some years later after Maximian’s death in 556, Justinian’s letter that was addressed to the succeeding bishop Agnellus (557–70) ratified the supremacy of the Church of Ravenna and thus, unconsciously recognized the advent of the ‘new prince’ of the apostles.

The holy mother church of Ravenna, the true mother, truly orthodox, for many other churches crossed over to false doctrine because of the fear and terror of princes, but this one held the true and unique holy catholic faith, it never changed, it endured the fluctuations of the times, though tossed by the storm it remained unmovable.61

4.5. The Ravennate Type or the Justinanic Type of Transfiguration

Although their external artistic representation appears different at first glance, the Metamorphosis iconography of the two Justinianic apses converges on some elements. Above all, as mentioned previously, both share the symbolism of light accentuating the ontological eminence of the glorified One, and therefore clearly exclude the two prophets outside the light. In contrast, relying on Origen and Anastasius the Sinaite who comment that the two prophets were also transfigured, Andreopoulos calls it an ‘anomaly’ that Moses and Elijah are not included in the mandorla of the Sinai apse.62 His mention of the term ‘anomaly’ is partly right, only in the sense that the location of Moses and Elijah outside the mandorla of the Sinai apse is contrary to all later Transfiguration images that set them inside it; instead, the location is unquestionably ‘normal’ in our thesis because the infinite ontological distance must be necessarily the first norm of its visualization. This point allows us to distinguish the twelfth–thirteenth centuries’ description of Nicolaos Mesarites and the ninth-century Transfiguration illumination in the Paris Gregory manuscript from the original Transfiguration plan in the Church of the Holy Apostles in the sixth century at Constantinople. In the former, the two prophets are located inside a mandorla, and Peter is unmistakably speaking;63 this is typical in the later Transfiguration type, whereas the two Transfiguration icons of Justinian’s age depict at once the two prophets outside the glorious light and Peter deprived of the opportunity to speak. Furthermore, the original Metamorphosis plan in the church of the Holy Apostles must follow the Justinianic Transfiguration type.

Another convergence of the two Justinianic apse mosaics concerns an omission of the representation of Mount Thabor. While the later Transfiguration iconography contains, without exception, a representation of Mount Thabor, neither the works in Ravenna-in-Classe nor the Sinai mosaics render it.64 In Classe, green is used to symbolize paradise and, similarly, a green strip that resembles the one in the Arian baptistery in Ravenna is applied to the Sinai mosaic (Figure 18). Elsner’s conjecture about the green stripe in Sinai Transfiguration being a minimalist representation of Mount Thabor would be unacceptable because of its similarity to that of the Arian baptistery in Ravenna (Elsner 1997, p. 112).

Figure 18.

Jesus’ Baptism, the Arian Baptistery, Ravenna, 525. Photo by the author.

Unsuitable is also Weitzmann’s suggestion that the absence of Thabor on the Sinai apse is due to the eschatological dimension symbolizing Christ of secundus adventus with Moses and Elijah (Weitzmann 1965, p. 14); Elsner’s and Weitzmann’s propositions cannot be deemed as appropriate solutions to why the depiction of Mount Thabor was omitted only from the two Justinianic Apses while it is illustrated among all of later Transfiguration images. Moreover, Weitzmann’s eschatological view is not compatible with Peter’s sleeping scene because it is unimaginable for Peter to sleep during the Second Coming of Christ.

The doctrinal or Christological approach to the two Justinianic Transfiguration icons has some difficulties in elucidating the primary cause of their historical origin. Weitzmann and Andreopoulos want to read from the Sinai apse an allusion to the dogma of the two natures of Christ formulated by the council of Chalcedon in 451, and Weitzmann even attributes eschatological, liturgical, and typological meanings to it (Weitzmann 1965, pp. 14–15; 1966, pp. 401–2; Andreopoulos 2002, pp. 14–18; 2005, pp. 133–36). The analysis of Abramowski aims to demonstrate the visualized New Chalcedonian Christology in the Metamorphosis image in Classe, which may also apply to the Sinai apse: the theopaschite point of view solemnly vindicated in the fifth ecumenical council of Constantinople in 553 (Abramowski 2001, pp. 301, 308–13). Despite its significance, such doctrinal dimensions unquestionably reveal vulnerable points that never satisfactorily clarify the aforementioned puzzles: the two prophets located outside the clipeus or the mandorla, the depiction of a sleeping Peter in the Sinai apse, Peter depicted as a lamb on the apse of Classe, and finally, the absence of Mount Thabor in both apses.65 Thus, it is logical to conclude that the Christological interpretation in the apse of Sant’Apollinare is of secondary significance in comparison to the making of a Christian Moses and that the latter truly dissolves all enigmas.

4.6. The Reaction of the Emperor Justinian concerning the Mosaics of Maximian

Finally, one wonders how Justinian became conscious of the genuine value of the typological iconography in the sanctuary mosaic of San Vitale. Curiously, five years after the consecration of San Vitale in 548, on February 8, 553, he promulgated the constitution Novellae 146, prescribing in its first lines that the Jews should accept Christological typology for the Old Testament.66 Even though this rescriptum was issued as an answer to a petition by Jews questioning the proper language in which to read the Old Testament, an influence of the sanctuary mosaics of San Vitale, given this first sentence of Novellae 146, cannot be completely excluded.

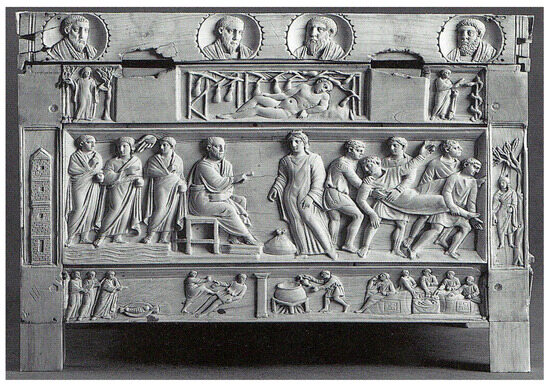

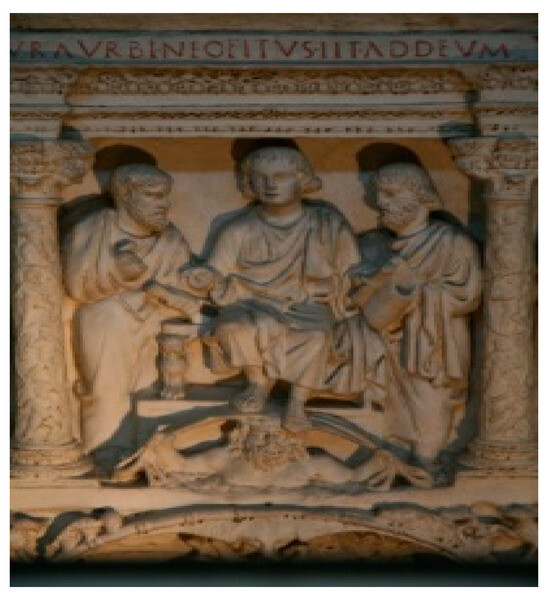

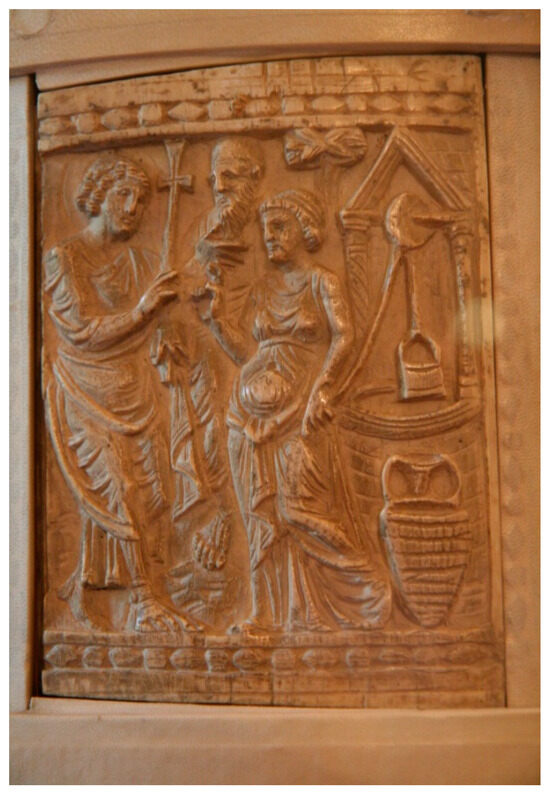

Concerning the making of a Christian Moses, one of the carved ivory panels on the cathedra of Maximian also deserves attention: the ivory panel depicts the meeting of Christ with a Samaritan woman at a well (Figure 19).67 This unique, impressive chair was delivered to Maximian as a gift by Justinian, probably in memory of the consecration of the two almost contemporary churches dedicated to St. Vitalis and St. Apollinaris. Contrary to the opinion of E. Smith, who attributed a simple Eucharistic significance to the ivory panel in question,68 a deeper meaning can be identified by considering Justinian’s policies against the Jews.

Figure 19.

The meeting of Christ with a Samaritan woman at the well, an ivory panel on Maximian’ cathedra, Ravenna, 550–556. Photo by the author.

The distinguishing feature of the scene is the position of the Samaritan woman. The woman, leaving the well and her water jar behind, comes closer to Jesus, stretching forward her right hand to seize the cross held in Jesus’ right hand. Thus, the scene represents Jesus’ declaration of himself as the Messiah (John 4:26) and her conversion to Christianity. A man standing behind the woman is perhaps one of the Samaritan people whom she brought from the city (John 4:28–30), rather than one of Jesus’ disciples. The carving explicitly focuses on the conversion of Samaritans to the Christian faith. However, in the majority of depictions of the scene with the Samaritan woman, such as that found on a mosaic panel in the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, the dialogue between Jesus and the woman, who are both located on opposite sides of the centered well, is represented as still in progress; on the other hand, in the ivory panel on Maximian’s throne, the dialogue has finished. Consequently, this carved ivory panel, whose theme keenly focuses on the conversion of Jews, can be interpreted as Justinian’s ultimate response to Maximian’s creation of a Christian Moses.

5. Conclusions

The approach of the current study challenges the historical scholarship of the Metamorphosis mosaics at Classe and Sinai mainly by: (1) the sharp distinction between the pre-Ravennate type and the Ravennate or Justinianic type through the symbolism of the light, (2) the critical hermeneutic contrast between ‘the master and the servants’ found in the patristic exegetical tradition of the fourth and fifth centuries, (3) the contradiction between Maximian’s double typology of San Vitale and Justinian’s persecution of the Jews, (4) the dissolution of said contradiction by the regeneration of Moses as an obedient and convinced Christian, (5) the emergence of the image of the censored Peter and the omission of Mount Thabor in the visual representation at Classe and at Sinai, (6) the elevation of St. Apollinaris to the ‘new prince’ of the apostles, an elevation that is, beyond the biblical and patristic meanings of the Transfiguration, intelligently attached to the Metamorphosis composition with the contemporary intention of the Kirchenpolitik of the emperor Justinian, and (7) Justinian’s response to the two Maximian mosaics by means of the constitution Novellae 146 and the cathedra of Maximian.

Nevertheless, Justinian is not known to have visited Ravenna. When the hymns comparing him to Moses were sung by the choirs of San Vitale and Sant’Apollinare, the hero of those hymns never made an appearance under the images of the ‘a New Moses’ or the ‘Christian Moses’. One year after the consecration of the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare, Justinian rebuilt the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople (Grierson 1962, pp. 26–29), which was also an imperial ritual center, and, probably at the end of his reign, consecrated the church at Sinai as a symbol of Moses’ cult. The principal apse icons of these churches were related to ‘the Ravennate Transfiguration type,’ i.e., ‘the Justinianic Transfiguration type’—although the apse mosaic of Constantinople was later altered—but they were not related to the type representing Mount Thabor, such as on the door panel of St. Sabina, or on the Brescia lipsanotheca. To Justinian, the Ravennate Metamorphosis type created by Maximian was an effective instrument for deleting the inconsistency between the allusion to a New Moses (or Moses prefiguring Christ) and his hostility to the descendants of the Old Moses, and thus for promoting his politico-religious ambitions.

Funding

This research was supported by the funding of Seoul Hanyoung University.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| CJ | Codex Justinianus |

| CTh | Codex Theodosianus |

| Novellae | Novellae Constitutiones of Justinian |

| SC | Sources Chrétiennes, Paris |

| CCSL | Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina, Turnhout |

| CSEL | Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, Vienna |

| PG | Patrologia Graeca, ed. J.-P. Migne, Paris |

| GCS | Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller der ersten drei Jahrhunderte, Leipzig |

Notes

| 1 | For the first apsidal mosaics of Metamorphosis and its successive development in Eastern and Western images, see (Schiller 1971, pp. 145–52; Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 117–44, 169–77). Bishop John of Naples (535–555) had the apse of the Episcopal Church of St. Stephan in Naples decorated with the Transfiguration. Nothing is known about its form. See (Dinkler 1964, p. 25). |

| 2 | According to Agnellus, the bishop Ursicinus (533–536) began to build the basilica of Sant’Apollinare, but it was consecrated by the archbishop Maximian. See (Agnellus, The Book of Pontiffs of the Church of Ravenna, pp. 190–92; Agnellus, Liber Pontificalis Ecclesiae Ravennatis, pp. 232–33 and 244–46). A marble plate found on the exterior wall of the southern nave of the Church of Sant’Apollinare indicates that its consecration took place on May 9, 549. See (Deichmann 1969, p. 257 and Figure 16). |

| 3 | The basilica of St. Catherine’s Monastery was built between the deaths of Theodora (548) and Justinian (565). See (Weitzmann 1965, p. 11). |

| 4 | But the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople is assumed to have been destroyed during the turmoil of the iconoclasm of the eighth and ninth centuries, rebuilt, then finally devastated by the Turks in 1453. Nikolaos Mesarites described this mosaic in an ekphrasis written sometime between 1198 and 1203. For an original text and its English translation of the description of the Transfiguration of the Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople by Nikolaos Mesarites, see (Downey 1957, pp. 855–924; Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 169–74). |

| 5 | See (Dinkler 1964, pp. 50–71, 77–87, 104–5, 117). Concerning the Rotulus of Ravenna, see (Cabrol 1906, pp. 489–500). |

| 6 | (Grabar 1946, p. 16): “Quant à la mosaïque du Sinaï,…Certes, l’abside est occupé par une Transfiguration,... Cet image a dû être créée pour un sanctuaire du Mont-Thabor.” |

| 7 | (Ovadiah 1970, p. 71, n. 60). For its plan, see (Ovadiah and De Silva 1982, p. 132, n. 17). |

| 8 | For the study of Ovadiah, see (Grabar 1946, p. 195, n. 2): “Saint Jérome développe ces considérations dans un passage où il parle des trois sanctuaires du Mont-Thabor élevés en souvenir des tabernacles projetés par saint Pierre”. |

| 9 | The Church of St. Sabina was consecrated in approximately 432–433. See (Krautheimer 1986, pp. 171–74). The dating of the Brescia Casket is far from consensus, but it is generally said to have been created in the fourth or fifth centuries. See (Delbrueck 1952b, p. 78; Dinkler 1964, p. 34; Tkacz 2002, pp. 19–21). |

| 10 | Delbrueck, Spieser and Jeremias identified the St. Sabina door panel as a traditio legis type, while Dinkler and Andreopoulos interpreted it as the Transfiguration. See (Delbrueck 1952a, pp. 139–45; Spieser 1991, pp. 63–69; Jeremias 1980, pp. 77–80; Dinkler 1964, pp. 32–34; Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 102–6). Concerning the scene of the Brescia lipsanotheca, Schiller, Dinkler and Andreopoulos identified it as the Transfiguration, while A. Grabar left it unidentified and R. Delbrueck considered it to represent a resurrected Jesus’ apparition on the lake of Galilee. See (Kollwitz 1933, p. 29; Schiller 1971, p. 147, n. 9; Dinkler 1964, pp. 32–33; Andreopoulos 2005, pp. 106–8; Grabar 1968, plate 337; Delbrueck 1952b, pp. 32–34). |

| 11 | (Beckwith 1970, pp. 11–12). Andreopoulos and Spieser have the same opinion. See (Andreopoulos 2002, pp. 34–35; Spieser 1991, p. 64, n. 43–44). |

| 12 | Its Jesus-centered position and the object he holds in his left hand, whether it is a pearl, bread from heaven, or something else, may have an indication of his relative importance, but this alone is insufficient to portray Christ as the sole ruler of the universe, which is the fundamental principle of the traditio legis. Delbrueck writes that the pearl that Christ holds between two apostles stands for the word of God. See (Delbrueck 1952a, pp. 141–42). Jeremias considers it to be the bread from heaven mentioned in John 6:32 and Luke 14:15. See (Jeremias 1980, p. 80). |

| 13 | The titulus of the wooden panel above the door may be considered to be a strong allusion to its identification as a Transfiguration icon, as claimed by Dinkler. The titulus in question reads: “[Transfiguratio Domini in Monte] Maiestate sua rutilans sapientia vibrat Discipulisque Deum, si possint cernere, monstrat. (-[The Transfiguration of the Lord on the mountain]/shows his resplendent glory and shines his wisdom on the disciples of God, as they can discern.” (Dinkler 1964, pp. 33–34; Andreopoulos 2005, p. 262, n. 7). |

| 14 | Concerning several meanings of the number 99, see (Deliyannis 2014, p. 267, n. 309). |

| 15 | This refers to the study of Andreopoulos (2002, pp. 19–29), and also Andreopoulos (2005, pp. 145–54). |

| 16 | This opinion was also held by Tkacz (2002, p. 41). |

| 17 | According to Tkacz’s history of interpretations of the scene on the Brescia Casket, more scholars regard this as Jesus and his disciples, not the two prophets, in the scene (Tkacz 2002, pp. 221–22). |

| 18 | Irenaeus of Lyon, Adversus haereses, 4.20.9 (SC 100), pp. 655–57. |

| 19 | Origen, Commentatio In Matthaeum, 12.42 (GCS 40), pp. 166–67. |

| 20 | IDEM, pp. 167–68. |

| 21 | Eusebius of Caesarea, Commentatio In Lucam 9 (PG 24), col. 549 a. |

| 22 | (McGuckin 1987, pp. 167–72). He notes that the Cappadocian Fathers were relatively mild. |

| 23 | Ambrose of Milan, De Fide, 1.13.81 (CSEL 78), p. 35, ll.15–21. |

| 24 | IDEM, p. 36, ll. 24–28. |

| 25 | John Chrysostom, Homilia 56 In Matthaeum 16.28 (PG 58), col. 550 b-551 b. |

| 26 | IDEM, col. 552 g. |

| 27 | IDEM, col. 552 g–553 g. |

| 28 | Jerome, Commentariorum in Matthaeum 3.17.4 (SC 259), p. 30, ll. 54–62. |

| 29 | Cyril of Alexandria, Homiliae Diversae 9 (PG 77), col. 1012 D. |

| 30 | IDEM, col. 1013 A-B. |

| 31 | IDEM, col. 1013 D-1016 B. |

| 32 | Proclus of Constantinople, Orationes 8.2 (PG 65), col. 765 B-C. |

| 33 | IDEM, col. 765 C-D. |

| 34 | IDEM, col. 765 D-768 A. |

| 35 | IDEM, col. 768 B. |

| 36 | Unlike Justinian, the Theodosian Dynasty did not systematically persecute Jews, but its Jewish policy was hardened in comparison with Constantine’s Dynasty. Major anti-Jewish laws enacted by Constantine’s Dynasty include Codex Theodosianus (henceforth CTh) 16.8.1, 16.8.5, 16.8.6, 16.8.7, 16.9.1. For major constitutions against Jews enacted by the Theodosian Dynasty, see CTh 16.8.16, 16.8.19, 16.8.22, 16.8.23, 16.8.24, 16.8.28, 16.9.2, 16.9.3, 16.9.4, 19.9.5. |

| 37 | Egeria, Peregrinatio ad Loca Sancta (SC 296), p. 274, ll. 9–20. |

| 38 | CTh 16.1.2 (SC 497), pp. 114–15. For the political/religious policy of Theodosius, see (Nam 2010, pp. 137–57). |

| 39 | For the double typological iconography of Moses’ life of San Vitale, see (Montanari 1995, pp. 627–47). |

| 40 | Maximian was a native of Nola in Istria, and had been resident in Constantinople as deacon, perhaps protected by the empress Theodora when he was appointed by the emperor Justinian as the new bishop of Ravenna and consecrated in Patras by the pope Vigilius. (Agnellus of Ravenna, Liber Pontificalis Ecclesiae Ravennatis 70, pp. 238–40; Markus 1979, pp. 294–99). |

| 41 | For the general introduction of the mosaics of San Vitale and its significance, see (Von Simson 1948, pp. 23–39; Jäggi 2013, pp. 231–59; Dresken-Weiland 2015, pp. 212–53). |