Abstract

Muslims living in non-Muslim countries may experience marginality, which has associations with exclusion, poor socio-emotional health, higher rates of family violence, and poor quality of life. Faith-based strategies have the potential to bridge the gaps and improve the outcomes for these communities. We undertook a reflective evaluation of the individual and group interventions of a Muslim start-up NGO, Community Development, Education and Social Support Inc. (CDESSA) (Adelaide, SA, Australia). Qualitative data were generated via dialogue, storytelling, and making connections with meaning based on observations of the lived experiences of the narrators. The analysis involved revisiting, reordering, refining, and redefining the dialogue, and conscious framing around a theoretical model of community cultural wealth. The results showed the growth of family and community engagement in CDESSA’s support and intervention activities, commencing with a small religious following in 2021 and growing to more than 300 Muslims regularly joining together for faith, health, welfare, and social wellbeing activities. Reflections on the dimensions of aspirational, navigational, social, familial, ethnoreligious, and resilient forms of community cultural wealth showed that the range of individual and group interventions, involving religious leaders, contributed to improving health and wellbeing, thereby growing community capital as a mechanism for strengthening families in this community.

1. Introduction

Muslims living in non-Muslim countries tend to experience difficulties accessing health, welfare, and social support due to mainstream indifference to their cultural and ethnoreligious needs (McLaren et al. 2022). Indifference leads to marginality, and marginality leads to inequity in health and welfare knowledge, service access, and the availability of suitable support (Riggs et al. 2015; Shahin et al. 2021). When such barriers exist, the outcomes for members of Muslim and other minority groups may be low levels of health literacy (Hamiduzzaman et al. 2022), poor socio-emotional health and wellbeing (Abood et al. 2021; McLaren et al. 2022), higher rates of family violence (Chen et al. 2022), diminished quality of life (McLaren et al. 2023; Patmisari et al. 2022), and silencing (McLaren 2016; Nawaz and McLaren 2016). Researchers have shown that implementation science incorporating faith-based strategies has the potential to bridge the gaps and improve the outcomes, achieving harmony in non-Muslim communities (Abu Khait and Lazenby 2021; Komariah et al. 2020). This is reflected in the United Nations’ religion and development agendas (The United Nations Population Fund 2016) and the World Health Organisation’s Faith Network (World Health Organization 2022), both of which recognise and bring into focus the benefits of building a community of collaborative sharing that includes faith leaders in program interventions. This study provides the latest evidence on the integration of religiosity in ongoing advocacy and awareness efforts.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care highlighted the importance of partnering with consumers in the planning, design, and delivery of services (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2023). The interventions may include community education, social and political welfare, and strategies to resolve conflict between couples, their families, members of their Muslim community, or even the broader community (Al-Krenawi 2016). Patmisari et al. (2022) investigated how different factors in the Muslim Quality of Life Index (MQLI) impacted aspects of personal wellbeing among a multicultural Muslim community in South Australia. Their findings highlighted spiritual fulfillment—a crucial aspect of the community’s ethnoreligious capital—as a key determinant of enhanced wellbeing outcomes and a significant element in mitigating anxiety. This emphasised the critical need to recognise and support the ethnoreligious attributes and resilience of multicultural communities to improve their overall quality of life. In a recent review of the health and social care needs of Muslims living in Anglophone countries, Australia, Canada, the UK and the USA, we identified 20 studies of mosque- and/or community-based Muslim health and social support interventions (McLaren et al. 2021). The review of these studies showed that Muslims wanted the integration of cultural and ethnoreligious aspects into services and programs. They desired the presence, guidance, and approval of religious leaders, and the provision of Islamic messages during interventions, as well as program scheduling that respected prayer times (McLaren et al. 2021). Our second review considered 21 studies reporting the outcomes of faith integration in health, welfare, and social care interventions with Muslim minorities (McLaren et al. 2022). The review of these studies showed that participatory approaches involving facilitators, researchers, and religious leaders collaborating in the delivery of services resulted in greater acceptance of the interventions, higher engagement in the interventions, and increased awareness of health, social care, and wellbeing (McLaren et al. 2022). The research widely supports greater engagement in program inventions and promotion of change using participatory approaches with those who have relevant living experience (Fleming et al. 2023; Widianingsih et al. 2018). Fostering the enhanced engagement of the Muslim community through working with religious leaders and integrating religiosity into interventions, such as by involving collaborative partnerships between services, families, and communities, is essential for health, social care, and wellbeing.

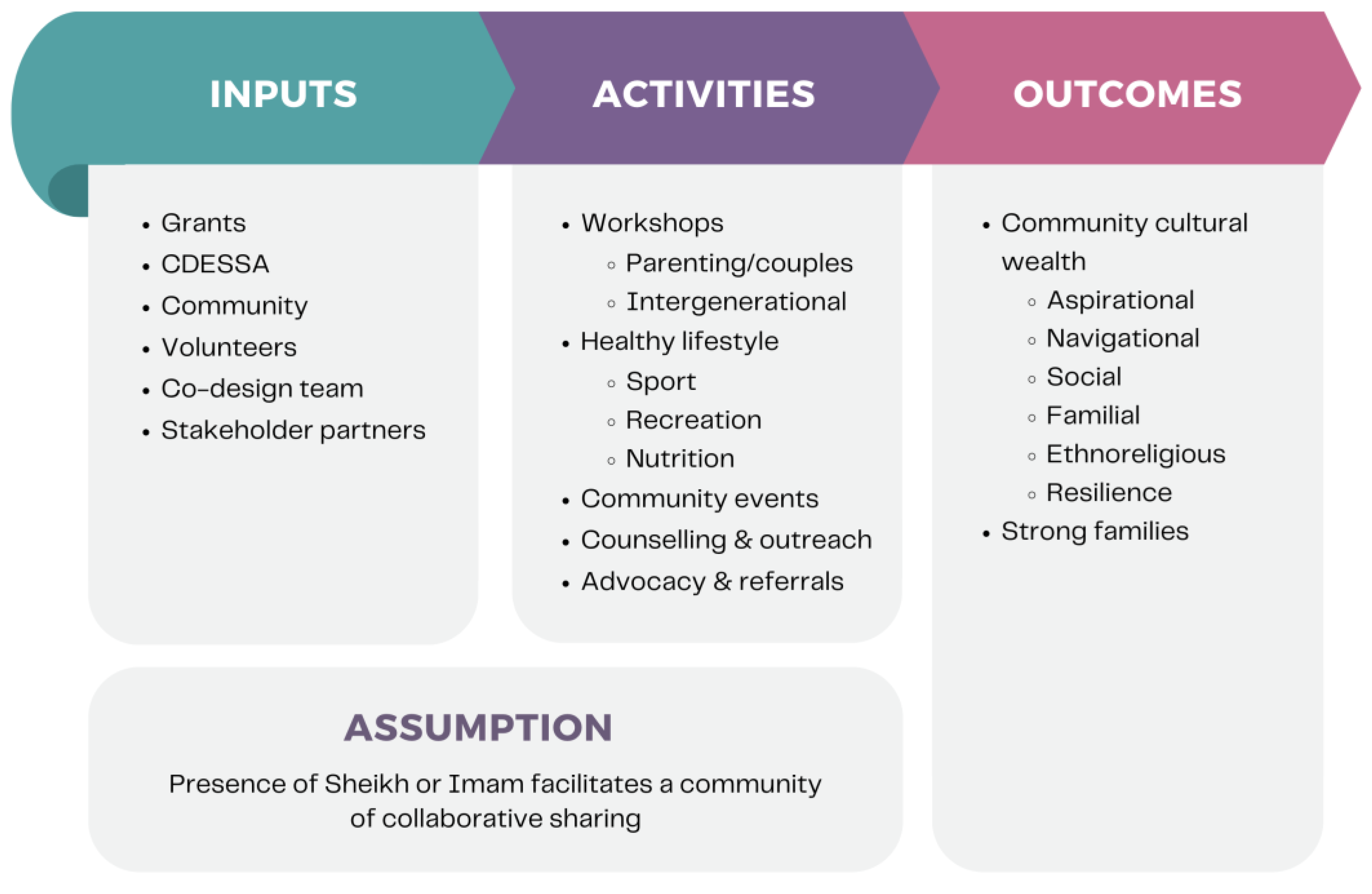

In this paper, we report on our reflective evaluation of a relatively new Muslim community service in South Australia, known as Community Development, Education and Support Services Australia Inc. (CDESSA). Members of this incorporated, not-for-profit body developed a series of strategies, novel programs and interventions designed to build relationships, connection, understanding, and trust among multicultural Muslims and non-Muslims from the broader community. The objectives were to collaborate in achieving culturally responsive intervention planning, implementation and delivery of family and community interventions to a multicultural South Australian Muslim community, delivered through a series of evidence- and religiously informed educational and social support strategies. The interventions supported multicultural Muslim families in fostering respectful, strong, and resilient relationships with each other and more broadly. This was achieved through parenting, couples, and intergenerational relationship programs, healthy lifestyle interventions, intercultural understanding and general social wellbeing strategies. The interventions were participatory and variously involved collaboration between religious leaders, health, welfare and education professionals, members of the justice system, and the university sector.

In our reflections, we draw on the idea of community cultural wealth, as originally conceptualised by Oliver and Shapiro (1995), emphasising the value of knowledge, practices, and relationships in shaping the outcomes for people in various socio-cultural or religious contexts. Further adapted by Yosso (2005), the concept recognises that different communities have multiple resources and strengths that include aspirational, navigational, social, linguistic, familial and resistant forms of cultural wealth. In applying a framework informed by community cultural wealth in our reflective evaluation, our adaptation of the model considers cultural dimensions of aspirational, navigational, social, familial, ethnoreligious and resilient forms. We offer invaluable insights into the work and dedication of CDESSA that draw upon diverse forms of capital generated from both multicultural Muslims and non-Muslims working together.

By exploring, reflecting, and discussing how cultural wealth operates, we show the mechanisms that drive the transmission, accumulation, and mobilisation of cultural assets among members of on of South Australia’s multicultural Muslim communities, and the ways of navigating and challenging societal norms, power structures, and institutional barriers to better enable health and social service access and engagement.

2. Materials and Methods

We employed a qualitative method involving dialogue between members of CDESSA and the program evaluation team in the planning of strategies, development of the theory of change, and reflection on the outcomes. In capturing the multifaceted nature of community engagement and development, traditional methodologies have often fallen short of addressing the complex interplay of cultural, social, and religious dynamics within ethnoreligious communities (Brunton et al. 2017). Recognising these gaps, we have adopted a novel methodological approach that is both reflective and participatory in nature. We have chosen to combine spoken and written authorship drawn from our conversational analysis undertaken as a form of reflective evaluation; an emerging approach when researching, evaluating, authoring, and offering new insights together with people who have lived experience—as the lead author has done in previous work (Fleming et al. 2023).

Our tailored approach used a reflective evaluation involving storytelling, as it celebrated the multiple resources and strengths of CDESSA and a Muslim community in South Australia, as observed by the narrators. This method was chosen due to limited success of survey and data collection with this community. The storytelling method connected strongly with collaborative meaning making. As Oliver (1998) proposed, people assign meaning ‘through the stories they tell’; hence, the use of methods that connect meaning with the life experience of members of CDESSA and a multicultural Muslim community, through conversation with researchers and others, makes the results of our reflective evaluation rich, nuanced, and reliable. The process of debriefing involved revisiting, reordering, refining, and redefining dialogue, and framing it around an adaptation of the community cultural wealth model, inviting the reader into our reflective dialogue.

Following the methodological approach of SueSee et al. (2022), we depart from traditional qualitative data collection and inductive thematic analysis to adopt a more conscious framing of our reflective evaluation. While SueSee et al. (2022) focused on the learning styles in educational settings, the underlying principle of adaptability is highly relevant to conducting research in hard-to-reach communities. This principle resonates with Oliver (1998), who suggested that the methods used to collect and analyse narratives should also be flexible, accommodating the unique contexts and experiences. Using an adaptation of the community cultural wealth model of Yosso (2005), we tailored our approach to reflect on and deeply examine the community’s unique resources. In so doing, we brought to life the work of CDESSA with the South Australian Muslim community they support and the broader community where they are located.

2.1. Story Collection

Adopting the methodologies of SueSee et al. (2022) and Oliver (1998), our study engaged in narrative analysis through a reflective dialogue. Helen, the lead researcher, has been intimately involved with CDESSA throughout the co-design project, providing a foundation of knowledge and methodological expertise. Renee, selected for her deep involvement in CDESSA’s activities and her role as a community leader, offered invaluable perspectives on the community dynamics and the impact of the activities. This strategic selection ensured a comprehensive understanding of the programs’ implementation and outcomes, enriching our data with firsthand experiences and reflections. Helen reached out to Renee, who agreed to a meeting at her convenience, ensuring a conducive setting. Prior to their dialogue, Helen provided Renee with a consent form detailing the intent to publish and ensuring informed consent. Their conversation was audio-recorded and accurately transcribed, allowing for a detailed analysis of their dialogue. Project approval was obtained from the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee, Project ID. 5703.

2.2. Narrative Analysis

Guided by Oliver’s (1998) approach, we conducted the narrative analysis by systematically reviewing and interpreting the dialogue between Renee and Helen. The transcriptions were shortened to enable the dimensions of aspirational, navigational, social, familial, ethnoreligious, and resilient forms of cultural wealth to be discussed. The short transcript, presented as the results, is a representative narrative of the Muslim community cultural wealth outcomes of CDESSA’s interventions. A reflexive approach involving ongoing discussion and checking of the narrative was framed by the broader research team according to the dimensions of aspirational, navigational, social, familial, ethnoreligious, and resilient forms of cultural wealth, and it is a representation of the Muslim community cultural wealth outcomes of CDESSA’s activities. This ensured trustworthiness and transparency in framing and discussing the data. The narrative configuration of the results offers explanation, meaning, and insight to the reader through stating the narrators, setting the scene, and the storyline (Oliver 1998).

3. Results

3.1. Narrators

Renee Taylor, a member of CDESSA’s executive committee, a Muslim community leader in South Australia, and the spokesperson for religious advisor and Islamic leader Sheikh Helmi Bakhour.

Helen McLaren, a researcher and evaluator at Flinders University with expertise in anti-oppressive evaluation designs intended to dismantle cultural and ethnoreligious boundaries.

3.2. Setting the Scene

CDESSA is a start-up NGO less than five years old. Commencing with less than 50 community members, over the last two years Muslim and non-Muslim engagement has increased exponentially. For example, an Islamic youth wellbeing forum was attended by more than 80 people, and both a community lunch and a multicultural Muslim Australia Day gathering by more than 200. The women’s group, involving art, sport, and nature walks, has regular attendance of more than 60, and the men’s group activities and sports of more than 40. Many of these are attended by Muslims and non-Muslim guests from the broader community.

Specific to the program and intervention funding, the stronger family workshops were attended by approximately 150 people. As well, CDESSA has provided individualised health, wellbeing, and social support to more than 100 people. These activities involved the provision of religiously informed community and individual interventions based on identified needs. They included spiritual counselling by the Sheikh or a social worker, and hard referrals (attending agencies with the person) as appropriate. As well, members of this Muslim community received ongoing encouragement to engage in their community, and the broader community, and to take on challenges. Members of CDESSA also undertook outreach home visits, provided form-filling paperwork assistance, supported the making of safe and well-informed decisions, and accompanied community members at case conferences. CDESSA welcomed participation in social and emotional wellbeing and healing activities. Through Sheikh Helmi, CDESSA also offered cultural (Islamic) understanding and sensitivity training/workshops to over 200 people from agencies including the South Australia Police, Australian Federal Police, Department of Prosecutions, etc. This helped to build a stronger community through cultural understanding. The CDESSA team has helped community members stay connected with family and each other during tough times. Most of all, CDESSA developed community cultural wealth through the Islamic virtues of sisterhood and brotherhood.

At a quiet café, Renee and Helen met to discuss CDESSA’s progress and interventions, reflecting on the organisation’s dynamic community engagement. The café offered a serene setting for Renee and Helen to engage in meaningful dialogue, far removed from CDESSA’s day-to-day activities yet intimately linked through the impactful stories they aimed to discuss. This choice of location facilitated a thorough discussion of the organisation’s achievements and the intricate process of fostering community cohesion and understanding, underscoring the value of a neutral space for reflective evaluation and strategic planning.

3.3. Storyline—Cultural Gaps and Approaches

3.3.1. Strategic Initiatives and Community Engagement

Helen: Renee, given CDESSA’s commitment to the South Australian Muslim community, what challenges do you see within the community that CDESSA aims to address?

Renee: CDESSA was funded by Multicultural Affairs, Department of the Premier and Cabinet, Government of South Australia, under the Stronger Together Grants scheme, for services aimed at strengthening ‘family’ and ‘community’ relationships with multicultural South Australian Muslims. Overseen by Sheikh Helmi Bakhour and Muslim community leaders, this was on the understanding that Muslim communities do not tend to get help or support because of the cultural gap. Without the Sheikh and Muslim leaders, the majority of their Muslim faith-based community would miss out.

Helen: What were your objectives, your assumptions, and your theory of change?

Renee: We wanted to develop a culturally responsive plan, implementation, and delivery of various strategies that could improve family relationships and resilience, for example, through parenting, couples, and intergenerational interventions. We wanted our community members to have cohesive families and to feel safe within their community and wider society. It was also important to us to strengthen family relationships through sound research and established educational strategies, and to encourage various government and non-government services to collaborate with us and co-deliver some educational and service strategies. We hoped for CDESSA to achieve this through delivering various educational wellbeing workshops and experiences that could teach our multicultural Muslim community and provide the tools to foster respectful, strong, and resilient relationships. We assumed that workshops would enable families to identify and address issues impacting their health, welfare, and social wellbeing, and then to have the confidence to access more specific support within the multicultural Muslim community or other services outside with the guidance of the Sheikh, Muslim leaders, and other relevant professionals involved in the workshops.

3.3.2. Collaborative Design and the Model Execution

Helen: How did you make that happen?

Renee: We consulted the members of the South Australian multicultural Muslim community to understand their needs, and we consulted religious and cultural advisors, university academics, educators, social workers, mental health workers from government and non-government organisations.

Renee: At the workshops and community events, we had several presenters, which included the Sheikh, education and mental health specialists, academics with expertise in family wellbeing, and guest speakers from government agencies, including the local and Australian police services. These were delivered in team settings. The presence of the Sheikh or other religious leaders enabled the multicultural Muslim community to see the synergies between local laws and practices and Islamic teachings, and to feel confident. Engagement in workshops and community events led some Muslim community members to seek individual or couples support, which was provided by CDESSA’s social worker whenever needed, with hard referrals involving being accompanied to outside specialist services. This helped to break down fears, be heard, and build confidence to access support, services, and other activities in the general community.

Helen: We came together as a co-design team involving CDESSA members, Muslim community members, and researchers. There were eight of us who mapped the inputs, activities, and outcomes, and we also formulated an assumption of what would work. We embedded it into a logic model, which was further refined during the program development and implementation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Community cultural wealth logic model.

Renee: Indeed, the refinement process was iterative and deeply reflective. We held regular meetings to discuss the feedback from the community workshops and events. The logic model served as a communication tool. It helped us articulate the project’s scope and objectives to all the stakeholders clearly and concisely.

Helen: It is fascinating to see how a dynamic, iterative process like this can lead to more impactful results.

Renee: Another key aspect was the continuous engagement with our stakeholders throughout the project. This was not just about gathering initial input but maintaining an open dialogue to ensure the program remained relevant and effective. It was through this sustained collaboration that we were able to navigate challenges and seize opportunities as they arose.

Helen: Yes, that is an excellent point, and the critical role of reflective evaluation cannot be overstated. It is what allowed us to adapt and refine our strategies in a way that was both meaningful and impactful.

3.4. Storyline—Bridging the Gaps with Cultural Wealth

3.4.1. Flexible and Responsive Approach

Helen: Then we engaged in our reflective evaluation. Since both of us have engaged in CDESSA-funded services and activities, both you and me, this formed the foundation for the reflective evaluation narrative. Let us talk about the outcomes, the cultural wealth of your community.

Renee: Yes, let us do that.

Helen: What you, the Sheikh, and other members of CDESSA have done is amazing. From just a small amount of people engaging with you and in a short period of two years you have this large, cohesive Muslim community that supports each other and that is connected with services. At the beginning, your community was quite closed, but at community events, I now see a range of Muslim and non-Muslim people coming together. This enhances communities, builds capacity, confidence, resilience, and it has an eye on the wellbeing of individuals, couples, families, and their children, in harmonious ways.

Renee: We were funded to do this, and to be very flexible. It was all about being non-threatening and inclusive to multicultural Muslim families and their needs. Some of the things we originally proposed were implemented a bit differently. We also did a lot of work with organisations, such as the South Australia Police and Australian Federal Police, providing cultural sensitivity training and understanding workshops.

Helen: So, you have done some of it as proposed and some you may not have, but it does not matter because you have moved according to the needs of your community.

Renee: Yes, moving with community needs and being responsive to them has been integral to building capacity; that support of each other, that collectivism, and that wealth that comes with the religious and the cultural identity.

Helen: Bringing people together with respect for each other.

3.4.2. Engagement with Broader Mainstream Society

Renee: We had community guests, the South Australia Police and Federal Police, the Department for Child Protection, Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, and many other government agencies. This has supported bridging a gap between government organisations that work with multicultural Muslims and the wider community. Sheikh Helmi Bakhour has given them cultural sensitivity training for working with Muslims, and we were then able to build a professional collaboration and bring representatives from these agencies to our Muslim community workshops and events.

Helen: These are agencies that people in your community might be afraid of, so you were bridging the gap.

Renee: Yes, they did not know much about us. They may not have known shaking the opposite gender’s hand, or something like that, was culturally inappropriate. So, just having that explanation for them through training, so they have that knowledge when they come and work with us or other Muslims, that is a step in the right direction in terms of cultural safety for the Muslim community.

Helen: I know, I have heard non-Muslim Australians say ‘Helen, I’m scared, what do I do?’ when asked to engage with Muslim communities. It is about breaking that down, then bringing the community together so there are interconnections and engagement with broader mainstream society. By Sheikh Helmi and members of CDESSA going out and bringing non-Muslim people back into your community, you are modelling safe engagement.

Renee: Yes, modelling, but our work is also about just being there. For example, to answer phone calls, whether they be from the community or from the police. Members of our community will say, ‘I have to fast1 and cannot attend a required appointment’ or something similar. We can support the non-Muslim community in understanding what that means and possibly working around it, so that they feel they are doing the right thing.

Helen: It is that process of generating Muslim and non-Muslim understanding, so that members of your community can be a part of civil society.

Renee: Yes, but then you have also got the cultural aspect. Through these processes, you are building this wealth of knowledge within your community as well as outside your community. Teaching people to be more accommodating and encouraging multicultural social cohesion. That is the whole thing about CDESSA. Even with family and parenting events, the Department for Child Protection, we go out and speak on behalf of the multicultural Muslim community. We did a learning workshop at a parenting event where Sheikh Helmi and two Child Protection workers presented on what is acceptable in Australian society and shared parental strategies. The members of our community asked questions, ‘What do you do if this happens?’ or ‘How can you deal with teenagers?’. It really started a lot of conversations. People who attended felt confident to then give advice to their wider group of friends, or to people they felt needed to hear it.

Helen: The learning was endorsed by the Sheikh, who had the knowledge of Islam. He was able to show that the virtues underpinning Islam have many similarities to local laws. It helps people to see that and live in accordance with both Islam and local laws.

Renee: There is a level of respect and knowledge that is there already. If you have got that level of Islamic status through knowledge and experience, it is easier to bring multicultural Muslim people together, with each other and with the broader community. New students and new migrants, when they come, they are a little bit reluctant to mix with the unknown.

3.4.3. Safe and Inclusive Spaces

Helen: In Australia, we are in a multicultural country, and some are not used to it. But it brings so much more to our community because people get to interact with each other and learn from each other.

Renee: We believe we have had such success because the multicultural Muslims that come to our events and programs feel so welcome and relaxed. Embracing the multiculturalism within Muslims is critical to feeling safe and connected. As well, it is interesting about the connections between parenting and families, in that people in our community do not necessarily have extended relatives. They might go home and visit from time to time. But when they need help, or when they are struggling, they fall into problems. That is where the relationships with the CDESSA team and community are so important.

Helen: They do not have extended family members to pull them aside when they are doing wrong, and to reorient them.

Renee: Guiding them, having this multicultural Muslim community in Australia and having trust is critical. Something simple such as not having any family here, so therefore not having someone else to drop the kids off or pick them up from school, can cause huge problems for a family. Perhaps they do not drive? Within the CDESSA community, we can locate someone close to pick up the kids. If we have a problem in the family, the friendships and support are strong and people do not have a problem saying, ‘Hey, did you know that there’s a different way to do it?’ We can give culturally appropriate advice.

Helen: It is like calling an uncle and saying, ‘I can’t deal with my son’s behaviour.’ The activities of CDESSA are about building a community where relationships are formed and support is available, and there is confidence and trust. That is where the community cultural wealth comes in. It is the ability to open up and say, ‘You know, when you do that with your children…’ People learn from each other. And when you bring in non-Muslim outsiders, it works both ways.

Renee: You know, we are all learning from each other at the same time. And then you have got people who have not been in Australia as long, who are more isolated from the society. The program of workshops and activities has stopped their isolation because they have got someone to talk to. In some cases, they have made close friends so they will come to our events or programs, meet someone, and then they realise they are living in the same suburb. They see each other, and then they continue coming to workshops and events, they support each other, learn together and offer advice to each other.

Helen: The great friendship is in the background. They get to trust members of CDESSA, the Muslim community members, and non-Muslim service providers who come to workshops and events.

Renee: Yes. They know they can call for support. They will call me for issues like domestic violence or similar. When they are experiencing something bad, they need that extra support and advice to engage with services in the broader community. The CDESSA workshops, activities, and programs, and the outcome of community cultural wealth, enable our people to be confident and resilient when accessing the support they need.

3.5. Community Cultural Wealth in Researchers’ Reflection

Upon reflection on community cultural wealth, the researchers observed the dynamic interplay of Yosso’s (2005) dimensions among the Muslim community in South Australia, particularly those engaged with CDESSA. While the dialogue between Helen and Renee was rich in illustrating the community’s cultural wealth, it did not explicitly categorise their experiences under Yosso’s (2005) six dimensions of cultural wealth. Helen allowed the conversation to flow naturally without steering Renee’s responses to fit predetermined categories, aiming for authenticity in capturing the community’s experiences and perspectives. This approach ensured the narrative remained genuine and reflective of the community’s actual dynamics and challenges.

3.5.1. Aspirational Capital

Aspirational capital reflects the community’s hopes and dreams for stronger family bonds and safer, more inclusive societal integration. As in Renee’s reflection above, she said:

We wanted our community members to have cohesive families and to feel safe within their community and wider society.

It represents a vision where family ties are strengthened and recognised as the cornerstone of a robust community fabric. In this envisioned scenario, every individual, irrespective of their background, feels valued, safe, and included, both within the microcosm of their community and in the broader societal context.

3.5.2. Navigational Capital

The strategy to engage community members and professionals across sectors demonstrates navigational capital. As Renee said, the community’s ability to manoeuvre through social institutions and barriers to access necessary resources is necessary for community improvement.

Navigational capital is about the art of negotiation, advocacy, and adaptation in environments that are often not designed to facilitate easy access for marginalised or underserved communities.We consulted the members of the South Australian multicultural Muslim community to understand their needs.

3.5.3. Social Capital

Social capital underscores the profound importance of networks, relationships, and connections, both within a community and extending outward, as vital resources for achieving collective aims. The approach to building and nurturing social capital, Renee explained, was exemplified through the efforts to engage a wide array of stakeholders in community initiatives:

We had community guests, South Australia Police and Federal Police, the Department for Child Protection, Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, and many other government agencies.

3.5.4. Familial Capital

The observation by Helen points to familial capital, where the emphasis on family and community events helps to strengthen ties and foster a sense of belonging among community members.

At the beginning your community was quite closed, but at community events I now see a range of Muslim and non-Muslim people coming together.

Renee’s insights further illuminated the intricate relationship between familial capital and the multicultural dimensions within Muslim communities.

Embracing the multiculturalism within Muslims is critical to feeling safe and connected. As well, it is interesting about connections between parenting and families.

Familial capital, therefore, is about leveraging the strength of family bonds and the richness of cultural diversity to build a community that is united, supportive, and inclusive.

3.5.5. Ethnoreligious Capital

The involvement of Sheikh Helmi Bakhour in providing cultural sensitivity training underscores the ethnoreligious capital of the community. Renee noted the integration of religious teachings and leadership in enhancing the community’s capacity to engage with broader societal systems.

Sheikh Helmi Bakhour has given them cultural sensitivity training for working with Muslims.

In essence, ethnoreligious capital embodies the synergy between religious faith and cultural heritage, offering a powerful resource for communities to navigate the complexities of societal integration.

3.5.6. Resilient Capital

Renee’s reflections on the community’s adaptability and collective support illustrate resilience, showcasing the community’s ability to withstand and recover from challenges through internal strength and solidarity.

Moving with community needs and being responsive to them has been integral to building capacity; that support of each other, that collectivism, and that wealth that comes with the religious and the cultural identity.The program of workshops and activities has stopped their isolation because they have got someone to talk to.

The emphasis on support for each other and the value of collectivism that Renee mentions is central to the concept of resilient capital. It is through this collective support system that the community can pool its resources, share burdens, and extend help to where it is most needed.

4. Discussion

This article updates the evidence on the integration of cultural and ethnoreligious aspects into health, wellbeing, and social support programs and interventions for the Muslim communities living in South Australia. It highlights the mechanisms that drive the systems and dimensions of community cultural wealth, which is instrumental in supporting resilience and strong families. The process involved health promotion initiatives, community events, counselling, advocacy, and referrals, cultural understanding and response training, and the outcomes were community members’ interconnections, increased support services, and engagement with the services. In 2021, there were 813,392 Muslims in Australia, constituted 3.2% of the country’s total population, and many of them lived in areas of higher deprivation, with a greater burden of diseases and a poorer quality of life and with inadequate social and economic opportunities (Australian Bureau Statistics 2022). A lack of integration of cultural and ethnoreligious aspects was stated as one of the leading causes of inadequate access to and utilisation of health, wellbeing, and social supports by the Muslim communities.

Our study extends the understanding of the mechanisms for building a community of collaborative sharing and the ways in which the programs and intervention work for Muslims within a non-Muslim country. One way of ensuring ethnoreligious relevance in programs and interventions is by breaking through institutional barriers, internalised biases, and the fear of the ‘Other’. It is these aspects that are potentially responsible for thwarting the fuller participation of Muslim minority groups in health, welfare, and social support initiatives. Developing services and support through community-based activities for Muslims, which bring Muslims and non-Muslims together while being respectful of religiosity, leads to greater engagement, appreciation of each other, shared resources, social capital, and cultural wealth (Saxena et al. 2020; Zaal 2009). This is important considering that services and interventions in non-Muslim, Anglophone, countries are known to generally involve discriminatory trends towards Muslim and multicultural ‘Others’ (Monani 2018). They are also often rooted in discursive fantasies that non-dominant ‘Others’ are less deserving than Christians or Whites (Chen et al. 2022; Fleming et al. 2023; McLaren 2009). According to Housel (2020), cross-cultural, ethnic, and religious collaborations build understanding, promote trust, and enhance empathy through working together and learning about each other. When communities come together, irrespective of differences, this can feed into the aspirational, navigational, social, familial, ethnoreligious, and resilient dimensions of cultural wealth. The approaches, activities, and intervention outcomes of CDESSA’s interventions provide a sound representation of community cultural wealth that is critically important for ensuring strong and resilient families, couples, and communities.

In consideration of the dimensions of community cultural wealth, e.g., aspirational, navigational, social, familial, ethnoreligious, and resilient forms, the narrators of our reflective evaluation of CDESSA’s interventions alluded to these various aspects. They highlighted the role of community connections in supporting parenting capacity, especially for the members of this Muslim community who mostly have estranged family connections due to immigration. They discussed the significance of bringing Muslim and non-Muslim others together, promoting understanding, cohesion, and enhancement of the community’s capacity through religious and cultural identity. Exposed in setting the scene, and in the storyline, are efforts to bridge the gaps between the Muslim community, wider communities, and government agencies. Mentioned is the need for cultural sensitivity training, which is necessary to address fears, misunderstandings, and to facilitate interactions between members of the Muslim community and outsiders. One could suggest that the facilitation of training to enable harmony between Muslims and non-Muslims constitutes a resilient dimension, as an aspect of community cultural wealth. The storyline emphasises the importance of modelling culturally safe community practices and interventions in order to break down perceived barriers and to thrive as a Muslim community.

Additionally, they discussed parenting sessions and family gatherings in their communities as foundations for building cultural and ethnoreligious knowledge and social cohesion. Our study reiterates the World Health Organization’s guidance (World Health Organization 2022) on the involvement of the Sheikh and religious leaders in the planning, design, and delivery of the services. Involving those with expertise in Islam was mentioned as an endorsement when explaining the alignment of Islamic values with local laws, which has likewise been acknowledged among Australian scholars on Islamic jurisprudence (Esmaeili et al. 2022). The reflective conversation showed the welcoming environment of the community, in which newcomers felt safe, comfortable, and integrated. In so doing, three levels of integration were suggested by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2023), including individual, service and organisational.

The narration revolved around the aspirational, navigational, social, familial, ethnoreligious, and resilient dimensions of cultural wealth, but it did not directly address them. In terms of the aspirational dimensions, this community has shown the capacity to maintain hope in the face of the poor health, socio-emotional outcomes, and wellbeing often experienced by religious, cultural or racial others, as established in other research (Abood et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2022; Hamiduzzaman et al. 2022; McLaren et al. 2022; Monani 2018). Prior research on the quality of life of a South Australian Muslim community in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic likewise showed aspirational capital (McLaren et al. 2023; Patmisari et al. 2022) and potential associations with community cultural wealth.

The storyline touched on the positive impacts of multicultural interactions on members of the Muslim community, specifically the formation of close friendships. They mentioned the importance of providing each other with support, especially where support from extended family networks was not available. The roles of trust, community connections, and shared experiences are noted as critical in the provision of guidance, advice, and assistance in various situations, including domestic violence issues and parenting challenges, and more formalised help to access support. The navigational capital, here, refers to the increased ability of this community to navigate social institutions, and to empowerment that is necessary to manoeuvre in environments that can be culturally or ethnoreligiously unsafe. The navigational capital associated with the interventions of religious leaders or others with ethnoreligious intelligence, to make Muslim and non-Muslim engagements safe, has likewise been shown in other studies revealing that religiosity in interventions with Muslim minority groups has associations with improved health and wellbeing outcomes (Hamiduzzaman et al. 2022; McLaren et al. 2021; McLaren et al. 2022). The narrators highlighted the presence of cultural wealth that developed in the South Australian Muslim community through religiously appropriate activities, including gender-segregated lifestyle groups, collective support, intercultural interactions, and strong relationships. Researchers have shown that the integration of Muslim religiosity in health, welfare, and social interventions plays a significant role in bridging these gaps (Abu Khait and Lazenby 2021; Komariah et al. 2020). The ethnoreligious capital of CDESSA’s Muslim community enabled its members’ ability to come together, embrace diversity, and assist one another. This has contributed to its overall community cultural wealth.

Despite the methodological rigor applied to the reflective narrative evaluation of the work of CDESSA, the current study is not without limitations. Our intention was to survey as many community members as possible to understand their experiences and outcomes of the education and community development activities; however, the response rates were poor at this stage. We tailored our research methods to overcome these challenges, utilising storytelling through a dialogue between researchers and community representatives. This storytelling approach, while valuable for building rapport and understanding, may not have been sufficiently expansive to capture the full range of community experiences and outcomes related to the community development activities facilitated by CDESSA. As the partnership and trust between CDESSA and the researchers continue to grow, additional research to further understand the mechanisms leading to growth in the community cultural wealth of this South Australian Muslim community will provide insights that will be beneficial to other ethnoreligious minority groups. This underscores the need for ongoing methodological refinement to navigate the complexities of researching within hard-to-reach communities effectively. The unique challenges presented by such contexts—ranging from establishing initial contact and building trust to ensuring meaningful participation and accurately capturing the nuances of community experiences—demand innovative, flexible, and culturally sensitive research strategies.

5. Conclusions

This reflective evaluation of the workshops, interventions and events facilitated by CDESSA in a multicultural South Australian Muslim community highlighted a range of dimensions important to the development of community cultural wealth among ethnoreligious minority groups. In considering that wealth equates to the accumulation of resources, we showed that the growth of community capacity, connections, access to support services, and wellbeing has relationships with the aspirational, navigational, social, familial, ethnoreligious, and resilient dimensions of community cultural wealth. CDESSA has contributed to the enrichment of the community’s cultural wealth, fostering an environment where aspirations are nurtured, challenges navigated, connections strengthened, familial bonds celebrated, cultural identities respected, and resilience built.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M., R.T., M.J.; methodology, H.M.; validation, formal analysis, H.M., E.P., C.M.; investigation, H.M., R.T., E.P.; resources, H.M., R.T., M.H.; data curation, H.M., R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M., R.T., C.M.; writing—review and editing, M.J., M.H.; project administration, E.P.; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research/evaluation was funded by Multicultural Affairs Stronger Together Grants, Department of the Premier and Cabinet, South Australia Government, Adelaide, 5000 SA, Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (project ID 5703, approval date: 21 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to the dual-identity participant authors.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. Author Renee Taylor is the organizational representative of, and volunteer with, the incorporated entity Community Development, Education and Social Support Australia Inc. (CDESSA). Authors Helen McLaren and Michelle Jones received subcontract funding via CDESSA consistent with core funding arrangements. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Referring to ‘sawm’ fasting during the month of Ramadan, which is an obligation for Muslims. |

References

- Abood, Julianne, Kerry Woodward, Michael Polonsky, Julie Green, Zulfan Tadjoeddin, and Andre Renzaho. 2021. Understanding immigrant settlement services literacy in the context of settlement service utilisation, settlement outcomes and wellbeing among new migrants: A mixed methods systematic review. Wellbeing, Space and Society 2: 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Khait, Abdallah, and Mark Lazenby. 2021. Psychosocial-spiritual interventions among Muslims undergoing treatment for cancer: An integrative review. BMC Palliative Care 20: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Krenawi, Alean. 2016. The role of the mosque and its relevance to social work. International Social Work 59: 359–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau Statistics. 2022. 2021 Census Shows Changes in Australia’s Religious Diversity: Media Release. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/2021-census-shows-changes-australias-religious-diversity (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2023. National Safety and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standard. In Partnering with Consumers Standard; Sydney: ACSQHC. [Google Scholar]

- Brunton, Ginny, James Thomas, Alison O’Mara-Eves, Farah Jamal, Sandy Oliver, and Josephine Kavanagh. 2017. Narratives of community engagement: A systematic review-derived conceptual framework for public health interventions. BMC Public Health 17: 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Jinwen, Helen McLaren, Michelle Jones, and Lida Shams. 2022. The Aging Experiences of LGBTQ Ethnic Minority Older Adults: A Systematic Review. The Gerontologist 62: e162–e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, Hossein, Jenny Richards, Marinella Marmo, and Lana Zannettino. 2022. Transformation from the inside out: Community engagement and the role of Islamic law in addressing family violence within afghan refugee and migrant communities in South Australia. The Adelaide Law Review 43: 301–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, Charmayne, Shirley Young, Joanne Else, Libby Hammond, and Helen McLaren. 2023. A Yarn among social workers: Knowing, being, and doing social work learning, expertise, and practice. Australian Social Work, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiduzzaman, Mohammad, Noore Siddiquee, Helen McLaren, and Md Ismail Tareque. 2022. The COVID-19 risk perceptions, health precautions, and emergency preparedness in older CALD adults in South Australia: A cross-sectional study. Infection, Disease & Health 27: 149–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housel, David A. 2020. Supporting the Engagement and Participation of Multicultural, Multilingual Immigrant Families in Public Education in the United States: Some Practical Strategies. School Community Journal 30: 185–209. [Google Scholar]

- Komariah, Maria, Urai Hatthakit, and Nongnut Boonyoung. 2020. Impact of Islam-Based Caring Intervention on Spiritual Well-Being in Muslim Women with Breast Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy. Religions 11: 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, Helen. 2009. Using ‘Foucault’s toolbox’: The challenge with feminist post-structuralist discourse analysis. Paper presented at the ‘Foucault: 25 Years on’ Conference, Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, June 25. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, Helen. 2016. Silence as a Power. Social Alternatives 35: 3. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, Helen, Emi Patmisari, Mohammad Hamiduzzaman, Michelle Jones, and Renee Taylor. 2021. Respect for religiosity: Review of faith integration in health and wellbeing interventions with Muslim minorities. Religions 12: 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, Helen, Michelle Jones, and Emi Patmisari. 2023. Multicultural Quality of Life: Experiences of a South Australian Muslim community amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies 13: 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, Helen, Mohammad Hamiduzzaman, Emi Patmisari, Michelle Jones, and Renae Taylor. 2022. Health and Social Care Outcomes in the Community: Review of Religious Considerations in Interventions with Muslim-Minorities in Australia, Canada, UK, and the USA. Journal of Religion and Health. Published online October 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monani, Devaki. 2018. At cross roads: White social work in Australia and the discourse on Australian multiculturalism. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 10: 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, Faraha, and Helen McLaren. 2016. Silencing the hardship: Bangladeshi women, microfinance and reproductive work. Social Alternatives 35: 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, Kimberly L. 1998. A journey into narrative analysis: A methodology for discovering meaning. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 17: 244–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, Melvin, and Thomas Shapiro. 1995. Black wealth/White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Patmisari, Emi, Helen McLaren, and Michelle Jones. 2022. Multicultural quality of life predictive effects on wellbeing: A cross-sectional study of a Muslim community in South Australia. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 41: 384–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, Elisha, Lisa Gibbs, Nicky Kilpatrick, Mark Gussy, Caroline van Gemert, Saher Ali, and Elizabeth Waters. 2015. Breaking down the barriers: A qualitative study to understand child oral health in refugee and migrant communities in Australia. Ethnicity & Health 20: 241–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, Gunjan, Mohammad Masrurul Mowla, and Sultanul Chowdhury. 2020. Spiritual capital (Adhyatmik Shompatti)—a key driver of community well-being and sustainable tourism in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 28: 1576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, Wejdan, Ieva Stupans, and Gerard Kennedy. 2021. Health beliefs and chronic illnesses of refugees: A systematic review. Ethnicity & Health 26: 756–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SueSee, Brendan, Shane Pill, Michael Davies, and John Williams. 2022. “Getting the Tip of the Pen on the Paper”: How the Spectrum of Teaching Styles Narrows the Gap Between the Hope and the Happening. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 41: 640–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations Population Fund. 2016. Realizing the Faith Dividend: Religion, Gender, Peace and Security Agenda 2030. New York: UNFPA. [Google Scholar]

- Widianingsih, Ida, Helen McLaren, and Janet McIntyre-Mills. 2018. Decentralization, Participatory Planning, and the Anthropocene in Indonesia, with a Case Example of the Berugak Dese, Lombok, Indonesia. In Balancing Individualism and Collectivism: Social and Environmental Justice. Edited by Janet McIntyre-Mills, Norma Romm and Yvonne Corcoran-Nantes. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 271–84. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2022. WHO Faith Network. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/who-faith-network (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Yosso, Tara J. 2005. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education 8: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaal, Mayida. 2009. Neglected in Their Transitions: Second Generation Muslim Youth Search for Support in a Context of Islamaphobia. New York: City University of New York. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).