3. The Ars Notoria’s Translations into Hebrew

It is unequivocally established that around the late fourteenth century, likely circa 1390, the

Ars Notoria was translated into Hebrew. This translation is attributed to Shlomo ben Natan Orgueiri in Aix-en-Provence, as mentioned in Hebrew manuscripts dating from the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries.

9 Assuming that Shlomo ben Natan was indeed responsible for the translation, he chose the relatively straightforward title

Melekhet Muskelet, translating to “the intellectual art”. Approximately a century after this translation process—a fact fully acknowledged in the incipit of one manuscript—the Italian Kabbalist Yohanan Alemanno referred to

Melekhet Muskelet in his curriculum,

10 and, as Leicht has observed, Alemanno cites from the orations (e.g., §10).

11From the three extant manuscripts of this Hebrew translation, all of which were mentioned by scholars such as Steinschneider, Moshe Idel, and Reimund Leicht, we are now able to determine their relationship to the Latin text.

12 These are:

(MS 1) Budapest, Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, MS. Kaufmann A 246, 3–17 (Italy, 16th century).

(MS 2) Ramat Gan, Bar-Ilan University Library, MS. 286, 83r–92v (Italy, 16th century).

(MS 3) St. Petersburg, The Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, MS. B 247, 90r–94v (Lithuania(?), 1780).

13

Upon comparing these manuscripts, it is readily apparent that while they are closely related, they are not identical copies. MS 2 and MS 3, for instance, have their orations numbered, a feature not found in MS 1. MS 3 uniquely contains the beginning of this Hebrew translation, including an acknowledgment of the translator. It starts with a few additional lines before commencing with §2 of the Ars Notoria in line 9 (“והנה אני אפולינוס חכם”). MS 1 and MS 2, on the other hand, are acephalous, likely due to the loss of folios. MS 1 begins with two unique paragraphs not found in the other manuscripts and only starts with §2 (“אמר: והנה אני אפולוניאוש חכם”) at line 15. MS 2 starts in the middle of a sentence that corresponds with §3 (“בקריאה לבדה תהיה נהפך”). Interestingly, a later hand added a reference on the upper margin of MS 2 to Alemanno’s mention of this book in his Shir Hamma’alot LiShlomo. Distinctly, MS 3 concludes right after the thirteenth prayer (§62).

Several elements underscore the independent nature of these manuscripts, suggesting the circulation of additional manuscripts between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Notably, the scribe of MS1 appears to have consulted more than one Hebrew exemplar. This is evidenced by occasional references to alternative texts (נוסח אחר), indicating comparison with other versions or variations of the text.

14 In contrast, the author of MS 2 exercised a form of censorship over the orations, particularly the lists of angelic names. This is evident from the notation stating that “the orations (דבורים) were not copied, since they have to be received from a wise man”.

15 This decision reflects a specific attitude towards the transmission of the angelic names, emphasizing the need for direct, personal instruction from a knowledgeable individual. The author of MS 3 incorporated many additions, some of which appear to be the scribe’s own contributions (as detailed below). However, others seem to indicate the use of a Hebrew exemplar distinct from MS 1 and MS 2, suggesting a more elaborated version. Intriguingly, both MS 2 and MS 3 number the orations as totaling thirteen, even though MS 2 (89r) extends to the oration of §69 (

oratione cognoscuntur generalia et specialia), similar to MS 1 (13). While a thorough comparison of these manuscripts is outside the scope of this paper, these noted differences are among the most significant.

Hence, we should be careful when referring to these texts as “translations”. These manuscripts are not “translations” of the

Ars Notoria in the strict sense. Instead, they are reworkings, sometimes significantly so,

16 of the older Version A, incorporating comments and interpretations absent in any of the Latin versions, indicative of substantial adaptation and original input. Several comments in these manuscripts are clearly derived from Jewish sources, such as the one found just before the (reworked) translation of §62 (MS 1, 12; MS 2, 88r). This particular section is missing in MS 3, due to the scribe of the exemplar omitting several passages between the twelfth and thirteenth orations.

17 I argue that this section likely originates from common discussions on letter combinations and permutations, most probably related to

Sefer Yetzirah:

And it is said that the revolution (גלגול) is a rotary motion. If it is around a [fixed] single center [i.e., axis], it always preserves the [motion] around the same place [i.e., the axis]. And if it is a revolution movement [i.e., around an external axis], it will not preserve a single center. And the conjunction is a linear movement, from one edge to another edge. And by way of elucidation, if you had a name like ארק, you could revolve it around itself and its center, and thus sometimes you will say ארק and sometimes אקר and sometimes קרא and other revolutions […]. And by that he implied to what is known from the books of the Jews concerning the taking of some of the things that are written in their books and join them to other letters. And these are also written in their books, as they received from their elders and prophets, until the angels who received these secrets were perplexed.

18

Binding together movements typical of celestial bodies with the revolutions of written letters, thus treating letters as stars

de facto, is highly indicative of a source that was acquainted with one of the astrological interpretations of

Sefer Yetzirah.

19 This theme is not isolated to a single passage but recurs frequently. For instance, in a brief comment, the scribes speculate, “perhaps this is implied by the Jews when they correspond letters and forms to the planets”.

20 This recurring motif reflects a consistent interest in linking astrological concepts with linguistic elements within the text. This recurring motif might shed light on the unique case where the term ‘astronomy’ (§19) is translated differently across manuscripts: as ‘Gematria’ in MS 1, 6 (חכמת הגימטריא), as both ‘geometry’ and ‘Gematria’ in MS 2, 84v (בחכמת התשבורת והגימטרי[א]), and seemingly as just ‘geometry’ in MS 3, 92v (בחכמת היאומיטרוא”ה). However, these translations might have other explanations, such as the possibility that ‘geometry’ replaced ‘astronomy’ in an original Latin text. This variety in translation could reflect differing interpretations or textual traditions among the scribes.

While the concept of letters as celestial bodies is present in various commentaries on

Sefer Yetzirah, most notably in the early fourteenth-century commentary by Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi,

21 there are several reasons to suggest that the passage in question is also a translation. The language of this passage not only mirrors the style and linguistic forms of the text that is true of Latin origin, but it also includes an explicit reference to “the books of the Jews”. This phrase echoes a context in the

Ars Notoria, where scribes refer to certain passages as being derived from “very ancient books of the Hebrews” (

ex antiquissimis hebreorum libris extracta, §3). Our translation, “the books of the Jews” pertains to texts detailing methods for letter combinations. The passage asserts that the knowledge in these books surpasses even that of angels, potentially indicating a subtle polemical stance towards other forms of knowledge associated with angels. This suggests a deliberate intertwining of different traditions and views on this practice in the text.

22Readers who examine the extant Hebrew manuscripts of the

Ars Notoria may be disappointed to discover that they do not contain any of the famous

notae. It is worth noting that a single Hebrew manuscript that does include such

notae is not a translation of the

Ars Notoria, but rather another work attributed to King Solomon, known as The

Clavicula Salomonis.

23 In this instance, the

notae appears to function more as decorative elements, even though they may possess amuletic qualities, rather than serving as the proper

notae that accompany the ritual of the

Ars Notoria. It could be speculated that such

notae may not have been as appealing to Jewish practitioners, who might have placed greater emphasis on the verbal components and been less interested in visual appendices that often featured Christian elements. However, upon closer examination of the texts, it becomes necessary to explore whether the absence of one of the most renowned features of the

Ars Notoria affects the utility of the text for Jewish readers.

24As we previously mentioned, the

Ars Notoria contains numerous prayers with lengthy lists of angels. It is reasonable to assume that even these prayers alone can provide some benefits, as supported by textual evidence. The

Ars Notoria itself, in several instances that deviate from its central theme, acknowledges the power of certain prayers. For instance, one of the prayers (

verba) that should be recited during the ritual is described as (§34): “to be said [when] in danger of fire, earth, and beasts”, without any direct connection to acquiring knowledge. These micro-deviations in the text invite practitioners who are interested to use these prayers independently of the Ars, without the need for a

nota. These deviations fragment the text, allowing practitioners to select and use specific elements as desired. Therefore, it is not surprising to encounter formulas from the

Ars Notoria in different treatises, such as the

Liber Iuratus Honorii and Berengar Ganell’s

Summa Sacre Magice, detached from any

notae and employed for various purposes.

25When a text undergoes even the slightest break, it opens the door for changes. Scribes often come across specific passages that resonate with them, incorporating them into their own unique compositions. The scribes of the Hebrew versions of the

Ars Notoria are no exception to this practice. This is evident in the case of the Ashkenazi scribe of MS 3, who suggests the use of the eighth prayer (§43 in the

Ars Notoria) to adjure the king of demons (93v). He proceeds to outline the procedure, which involves adjuring the well-known Arabic demon king Shamhurish (

شمهورش) to send one of his servants, essentially a familiar, in the form of a dog. In the Latin version A, this prayer is specifically intended for theology (

et est specialiter ad theologiam). Consequently, a Latin prayer designed to acquire knowledge related to Christian theology was later employed by a Jewish scribe, in Hebrew, to adjure a demon from Arabic tradition. This vivid and colorful scenario is typical of what scholars commonly refer to as “Solomonic magic”.

26 While the scribe of MS 3 added a demonic element to the text, the scribe of MS 2, perhaps unintentionally, infused it with a Kabbalistic flavor. This occurred when the scribe used the word ספירות (sefirot, 86r) in place of סברות, which is found in MS 1 (8) and MS 3 (94r) and corresponds to the Latin

intellectum (§47). In the same passage in the Latin text, we encounter “

Deus Pater, Fili Deus, Spiritus Sancte”, which is absent from the Hebrew manuscripts for obvious theological reasons.

The fact that the orations of the

Ars Notoria may have been perceived as valuable by the Hebrew scribes, even outside the context of the

Ars Notoria ritual, could explain the absence of

notae and the need to number them, a practice often found in recipe books. However, another explanation arises when we observe the inconsistent translation of the word “

notae” into Hebrew. In the case of MS 1 and MS 2, they sometimes use the term הערות, which translates to “notes” (MS 1, 13; MS 2, 89v), and at other times use הקדמות or התחלות, meaning “beginnings”. This latter choice may have resulted from a misreading of “

notae” as “initia”. This inconsistency suggests that the authors occasionally confuse one word with another, but in one instance, they seem indifferent to the specific term used. When describing the

notae of dialectic (referred to as חכמת ההגיון, logic), both MS 1 and MS 2 state: “… therefore it is imperative that it have two הקדמות, that is, התחלות or הערות, call them whatever you want”.

27 As a result, the scribes of MS 1 and MS 2 omitted passages that specifically addressed the inspection of the

notae: from §77, they skip to §90. In the process of acquiring knowledge, these practitioners do not require

notae but only the books they intend to learn from in this magically accelerated learning process, as instructed in §77. Their primary task is to recite the relevant orations (MS 1, 15; MS 2, 90a-v).

While MS 1 and MS 2 omitted

notae, which were likely considered useless, the case of MS 3 presents a more intricate and complex picture. Although this is a concise treatise that concludes at §62, its author abruptly describes a form of

notae at the very beginning of the treatise, in the middle of §2 (90r). Given its significance, I will quote the entire passage here:

And everyone who is involved in this art should know the vocalization [נקוד] of the orations, their meaning [הגיונם], and the manner of their (?) [(בואיהם)]. And he should write in a beautiful square script around each of the orations, facing each other, so that in a single moment, you will see them all. [And he should] dedicate his study efforts and thoughts to them and accustom himself to [seeing] them, being diligent with great diligence…

28

The author of this passage emphasizes the significance of gazing or contemplating the orations as a crucial step toward achieving the ultimate goal of this art. However, unlike the original

Ars Notoria’s combination of geometric figures and textual orations, in this case, the focus of contemplation is solely on the text itself. The text should be written in a way that allows it to be captured in a single glance. It should also be executed with style, reflecting the honorable value of these orations (akin to the way Torah scrolls are written), or perhaps echoing the

notae’s beautiful past (

Figure 1). In contrast to the visual elements, the text has survived as the primary object of contemplation. While a preference for the verbal over the visual is a common feature in the Hebrew manuscripts discussed, a recent discovery highlights a case in the opposite direction.

4. The Notae as The Ten Sefirot

In the early fourteenth century, no later than 1313, a Jewish scholar, likely from Castile, by the name of Avraham ben Meir de Sequeira (אברהם בן מאיר מאסקירה), authored a Kabbalistic treatise titled

Yesod ‘Olam ([The] Foundation of the World).

29 Unfortunately, this treatise survived in only one manuscript that was completed on July 18th, 1555 and is currently held in Moscow at The Russian State Library, Guenzburg MS. 607 (hereafter referred to as MS.607). The manuscript exhibits several codicological breaks, such as folios 66 and 74 being switched, likely due to later, somewhat careless, bookbinding. It is evident that during the seventeenth century, the manuscript circulated in Italy and eventually found its way into the library of a certain Avraham Sagari. After Sagari’s passing, the manuscript came into the possession of a young Rabbi named Reuven Joseph from Mondovi, who left a brief ownership note in elegant cursive Italian script on the first folio. In this note, Reuven mentions that Sagari had lived in his house for three years before his death. Interestingly, Reuven named this treatise “ספרא דרימונה”, which translates to “the book of the pomegranate”. This name likely stems from

Yesod ‘Olam’s labeling of its various sections as “pomegranates” (רימונים). The treatise is divided into an introductory part with thirty sections (referred to as פעמונים, bells), a first part with 65 “pomegranates” (24 in its first section and 41 in its second), a second part with 267 (164 in its first section and 103 in its second), and a third part with 175 (80 in its first section and 95 in its second). It is evident that at least two scribes worked on this manuscript, each with a different level of care and style.

As its title implies,

Yesod ‘Olam is a treatise that seeks to describe the cosmos and the divine worlds. Thus, it is not surprising that the author heavily relies on

Sefer Yetzirah and some of its commentaries, including the commentary by Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi.

30 While

Yesod ‘Olam primarily deals with the creation and structure of the world, it is not a purely descriptive technical treatise or a purely cosmological one. Its author drew upon numerous sources to support his statements and to illustrate the implications of the theories discussed. Avraham’s proficiency in various languages allowed him to access sources of various kinds of knowledge and incorporate them into his treatise, often without explicitly citing them.

31A case in point is the

Liber Lunae (the book of the moon), a medieval astral magic treatise attributed to Hermes and Apollonius of Tyana (which was based on the Arabic

مصحف القمر). This text was already in circulation in Europe during the thirteenth century and was known to Hebrew readers as

Sefer HaLevanah.

32 As Idel has observed, Avraham cites several passages from

Liber Lunae in his

Yesod ‘Olam.

33 He incorporated these passages into his work after discussing the cosmic spheres and the zodiac. Partly drawing from

Sefer Yetzirah, he explained that the twelve astrological houses can perform “unusual operations” (פעולות משונות) in the lower world, which refers to the physical world. He noted that this idea was testified by “the sages of the nations” (חכמי האומות).

34 To exemplify his statement, he then quotes from

Liber Lunae, citing Hermes (ארמש).

While Avraham’s use of

Liber Lunae was already observed by scholars, the possibility that he was familiar with and used the

Ars Notoria in

Yesod ‘Olam is unknown. In the second part of

Yesod ‘Olam, the author discusses the creation of the world (המצאת המציאות).

35 Apart from extensive use of pseudo-Empedocles’

Sefer Ḥameshet Ha’atzamim (the book of five substances), Avraham also incorporates, for obvious reasons,

Sefer Yetzirah.

Sefer Yetzirah is a short treatise that narrates God’s creative work, assigning to each of the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet a central role in the creation of different macro- and micro-cosmic objects. The ten sefirot, which are probably the ten numbers, also play a role in this process. Together with the letters,

Sefer Yetzirah refers to them as the “thirty-two wondrous paths of wisdom”.

36 As Idel noted, Avraham was well aware of the magical use of

Sefer Yetzirah, as he mentions in this second part of

Yesod ‘Olam: “In France there was someone who was acquainted with this and he was engraving the form of a cow on a wall, and it changed into a cow […]”.

37 In fact, Avraham viewed the magical use of

Sefer Yetzirah as a form of sorcery (כשוף) that is permitted even initially (מותר לכתחילה).

38Avraham then goes on to explain the “thirty-two wondrous paths of wisdom”, citing extensively from different sources within what Scholem considered the “‘Iyyun circle” (חוג העיון).

39 The term “‘Iyyun circle” is a scholarly convention for what was previously considered a cohesive collection of texts, primarily concerned with contemplation and speculation (‘

Iyyun) on the divine realm.

40 Avraham considered all thirty-two paths to be letters, including the first ten paths that are identified as the ten (Kabbalistic) sefirot.

41 According to him, the ten sefirot emanated in the same process as the twenty-two letters of the alphabet.

42 Eventually, after describing each of these first ten sefirot, Avraham will refer to them as “spiritual letters” (אותיות רוחניות).

43 I will not delve into the intricacies of Avraham’s Kabbalistic doctrine, as it is clearly complex due to his attempt to synthesize sources that do not always align with each other.

The first ten paths (נתיבים) are described by Avraham as the initial emanations, originating from the hidden, incomprehensible, and infinite path known as the “ancient air” (האויר הקדמון), the ultimate source.

44 Indeed, it is challenging to conceptualize a first path as infinite, a matter that Avraham promptly addressed in a typical description of the emanation process.

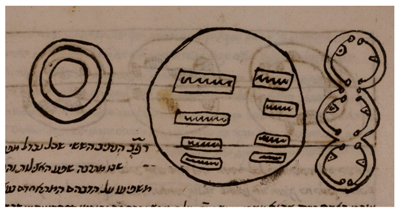

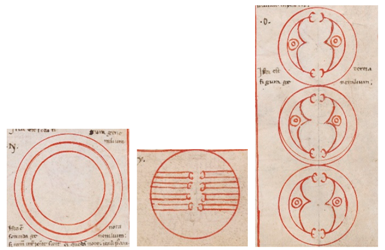

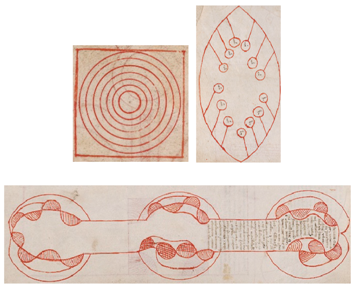

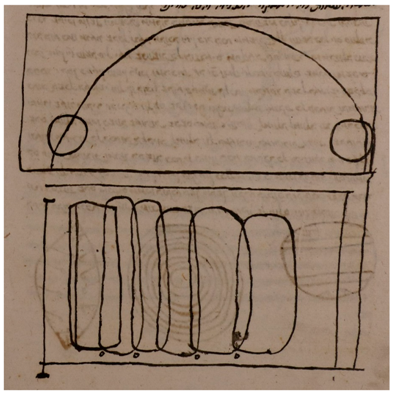

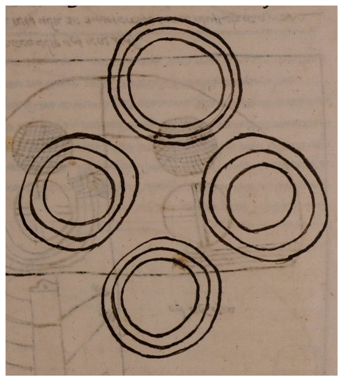

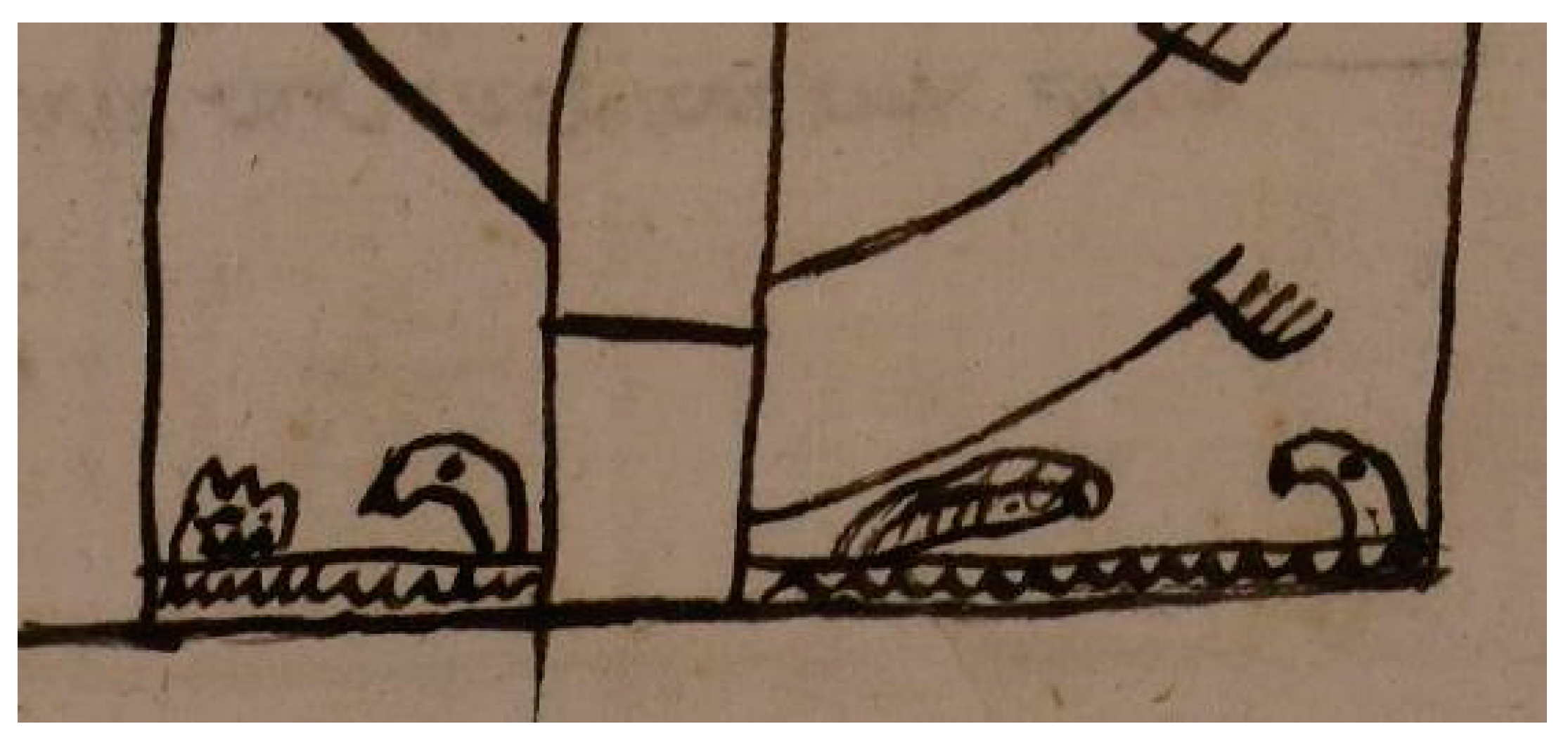

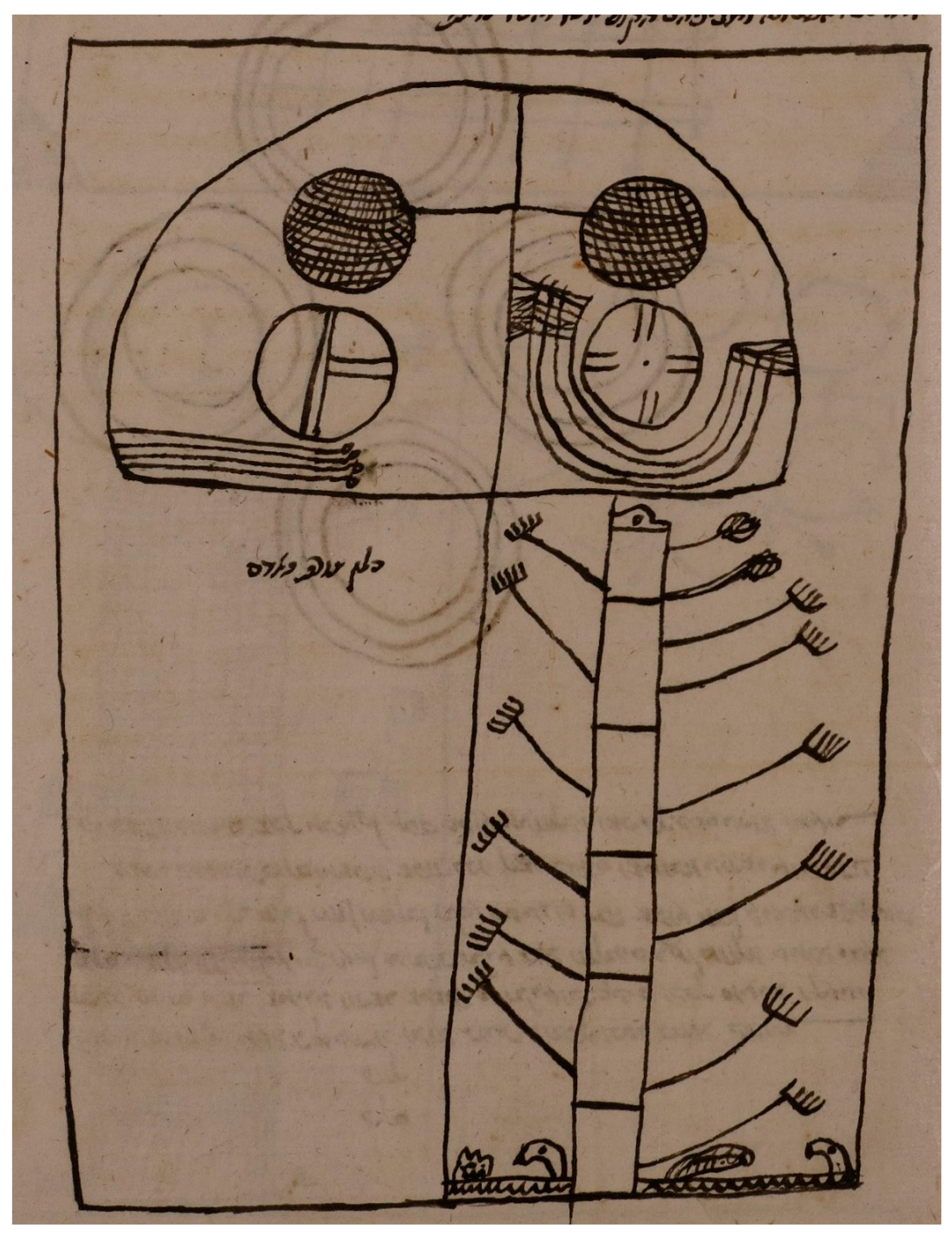

45 Avraham goes on to clarify that each of the first ten paths has ten names. At the conclusion of the discussion regarding the first path, he appends the phrase “and this is the first path” along with a diagram. Subsequently, another diagram is included, labeled “servants” (משרתים). The initial diagram (

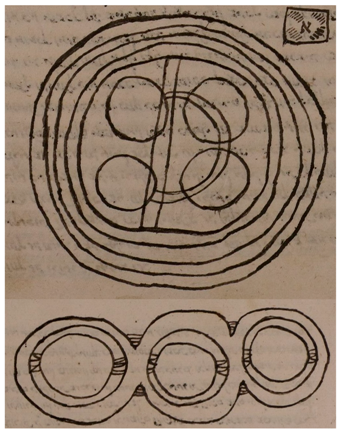

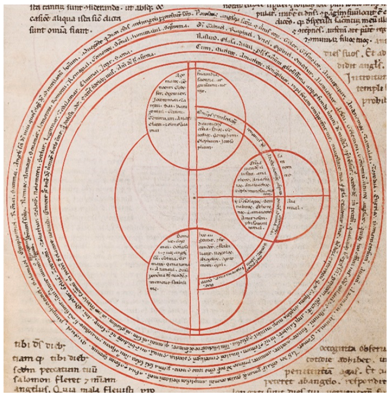

Figure 2) appears to illustrate these ten paths in a circular arrangement of ten concentric circles, which is a typical representation of the ten sefirot.

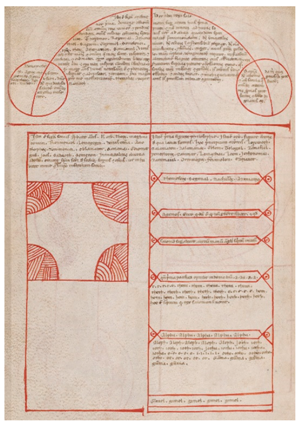

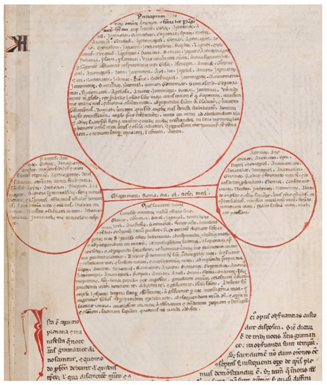

46 The text at the center of the diagram, which reads “incomprehensible air” (אויר שאינו נתפס), supports this assumption: we are facing a depiction of the ten sefirot. There is no apparent reason to suspect that it is related to the first

nota of grammar (

Figure 3), which is also the first

nota described in the

Ars Notoria. Only after examining the figures that Avraham attached to each path, it becomes evident that these are, in fact, the

notae of the

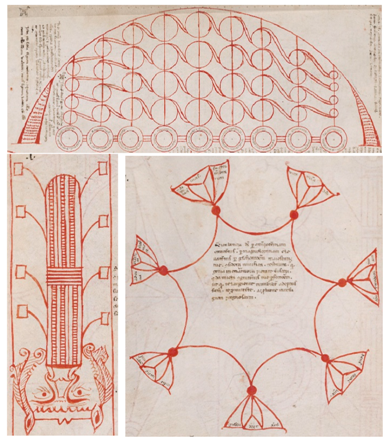

Ars Notoria. The second figure, labeled as “servants”, likely corresponds to the third

nota of philosophy (

Figure 4). Several questions immediately arise: why did this figure receive the label “servants”? Why were these specific

notae incorporated as the figures for this particular path? Is there a rule or underlying concept governing the correspondence between the paths and the

notae? I cannot provide definitive answers to these questions at this stage, but I will explore some possible avenues below.

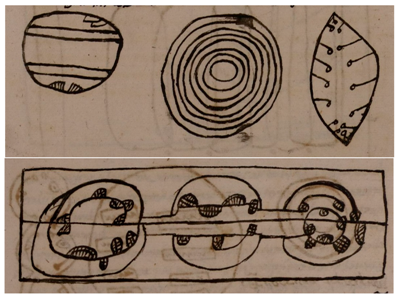

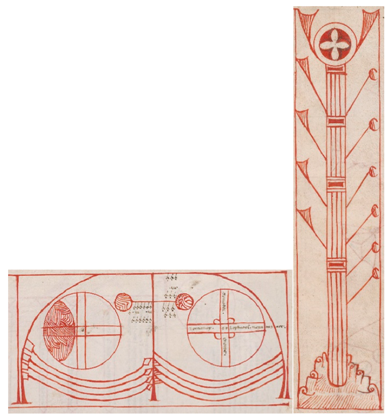

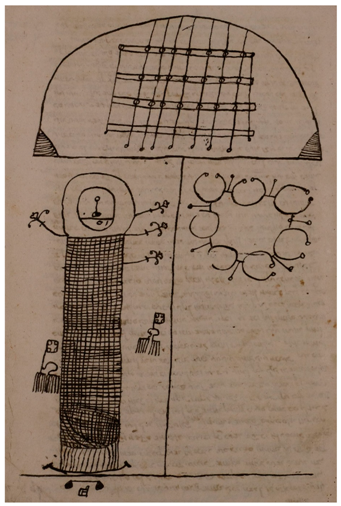

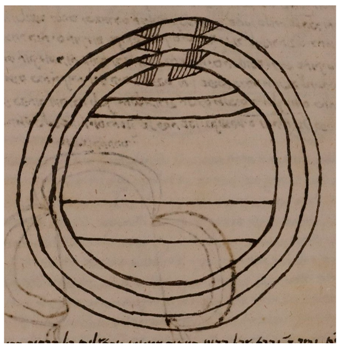

After describing the first path, Avraham proceeds to the second path, providing details about its emanation. In this case, he introduces the first

nota of dialectic (

Figure 5, which has been modified to include four similar interlocking inner circles instead of the usual three with another, larger, circle (

Figure 6). The choice to incorporate the

nota of dialectic as the figure for the second path may be related to Avraham’s description of the two parts of the world in this path as “voice and wind” (קול ורוח). However, this interpretation is speculative, and it is important not to impose a Kabbalistic interpretation that is not explicitly present in the text. Like the first path, the second path also features a figure, likely of the same origin (

Figure 7). While it is challenging to identify the figure of the third path, likely due to the naïve (and possibly careless) style of the copyists, the figure of the fourth path (

Figure 8), which Avraham associated with the seven water springs flowing to the seven climates (שבעה אקלימי עולם), is undoubtedly the second

nota of dialectic (

Figure 9). A comprehensive comparison between the figures of the ten paths and

Ars Notoria’s

notae is included below in

Appendix A.

The copyists of

Yesod ‘Olam were not particularly cautious. They not only made numerous errors in the text itself (some of which even raise questions about their language proficiency) but also seemed less careful when reproducing the figures of the paths. Consequently, it is not always straightforward to identify the corresponding

nota. In a single instance, the eighth figure, which combines elements from the first

nota of geometry and the second

nota of philosophy, along with components from other

notae (including the serpent-like heads at the bottom of the figure—see

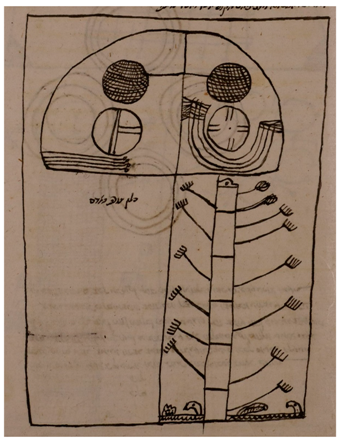

Figure 10), they left an empty space with the note “they are all in human form” (כלן צורת האדם), likely indicating the replacement of a diagram with a textual description (

Figure 11).

It is now imperative to address two fundamental questions: Firstly, the means by which Avraham gained familiarity with the

Ars Notoria, and secondly, the rationale behind its relevance to his treatise. These are complex and important questions that I would like only to reflect on and suggest directions for further study. But first, let me stress that I assume these figures are not a late incorporation of the copyists. This is partially because Avraham tends to use sources of different types, as in the case of

Liber Lunae. There is no reason to assume that these specific figures are late interpolations, especially since we know that

Liber Lunae and the

Ars Notoria sometimes circulated at the same time and place. For example, both are mentioned in a list of books that appears in the

Lucidator (1310) of the Italian philosopher and astrologer Pietro d’Abano (c. 1250–1316), thus attesting to the circulation of both in Italy during the late thirteenth century.

47 They both might have also been known to Michael Scot, who seems to refer to them in his

Liber introductorius, already during the first half of the thirteenth century (Ibid, pp. 107–11). However, the fact that both sources were known to Scot and Pietro d’Abano during the thirteenth century in Italy does not explain the manner in which they arrived at the Castilian Kabbalist. The legends about the

Ars Notoria being “the art of Toledo” also do not contribute to our historical examination (Ibid, pp. 117–28). Therefore, considering that the only extant manuscript of

Yesod ‘Olam dates back two hundred years after the original composition, the possibility of it being a later interpolation cannot be entirely dismissed.

The epistle attributed to Roger Bacon may provide revealing insights into the Jewish acquaintance with the

Ars Notoria.

48 Roger Bacon, a thirteenth-century Franciscan scholar, was not only aware of the

Ars Notoria but also explicitly condemned it. His critique extended over several years and was articulated in four texts, although there is some debate about their exact chronology and authorship. In the epistle that was written between 1257 and 1263, the author expressed skepticism regarding the effectiveness of the

Ars Notoria and raised concerns about the accuracy of its transliterated names. He suggested that a poorly translated or corrupted Hebrew original might have been the source of the Latin version. Bacon’s condemnation of the

Ars Notoria appears in his other writings, including the

Tractatus brevis (1267–1268) and the

Opus tertium, where he characterized it as deceptive and influenced by demonic forces.

49In the epistle, the author drew connections between a Hebrew treatise he had heard of (and of which he only possessed a part) called

Liber Semamphoras (the book of the ineffable name) and the

Ars Notoria. Véronèse rightly noted that

Liber Semamphoras echoes one of the volumes of the Castilian

Liber Razielis, a work commissioned by Alfonso X.

50 Following this, I suggest that while there is no reason to assume a Hebrew original of the

Ars Notoria (as the epistle implies), there is good reason to believe that the notion of such an origin was common and that even some authors attempted to establish such connections.

51 It is possible, thus, that the connection made by the author of the epistle between the

Liber Semamphoras and the

Ars Notoria was actually seeded already in the

Ars Notoria when the authors referred to a

Liber Vite (“the book of life”) as their source of angelic names (§43). While there is no reason to suggest that this

Liber Vite is associated with

Liber Razielis, those familiar with

Liber Razielis might have thought of

Liber Vite as another name for

Liber Semamphoras. Evidently, such identification is known at least from the first half of the fourteenth century, when the Catalan magician Berengar Ganell referred to

Liber Semamphoras (of the Alfonsine

Liber Razielis) as

Liber Vite.

52 Is it possible that the name

Liber Vite already circulated as the name of

Liber Semamphoras at the very early stages of the reception of

Liber Razielis? If so, it is only reasonable for the author of the epistle to draw this connection between the

Liber Semamphoras and the

Ars Notoria. However, this is yet another question that cannot be definitively answered at this time.

However, we can speculate that the idea of a Hebrew origin for the

Ars Notoria and its connection to the Alfonsine

Liber Razielis may have also sparked Latin interest in

Sefer Yetzirah, which eventually led to Shlomo ben Natan’s translation of the text.

53 If I am correct, and further evidence is needed, then the section of the Hebrew translations of the

Ars Notoria that echoes

Sefer Yetzirah may be reminiscent of an earlier stage of Jewish-Christian encounter regarding the

Ars Notoria. This interaction likely occurred before Shlomo ben Natan completed his translation, that is, before 1390. This raises the possibility that Avraham ben Meir de Sequeira, who used the

notae of the

Ars Notoria to depict objects from

Sefer Yetzirah, may have been involved in such an encounter.

Although Avraham’s familiarity with the

Ars Notoria is established, it does not inherently elucidate his rationale for integrating its

notae into his own composition. A more substantive explanation for this decision may be discerned within his treatise, wherein Avraham’s engagement with relevant issues becomes evident. In essence,

Yesod ‘Olam is a treatise written with the primary goal of preserving secrets about the world and, through the acquisition of this knowledge, attaining divine wisdom.

54 It becomes evident right from the initial sections of the manuscript, where Avraham explicitly outlines his objective: to elucidate the conditions and methods required to attain this wisdom.

55 Therefore, it appears plausible that Avraham saw the

notae of the

Ars Notoria as “paths” to access divine wisdom, much like their function in the ritual of the

Ars Notoria. In his view, these

notae represented the ten highest emanations, the initial ten “spiritual letters”, and the primary paths to attain divine wisdom and rectification (תיקון). According to Avraham, each

nota in his work embodied the form or figure (צורה) of one of these spiritual letters. Furthermore, just as the

Ars Notoria is considered to hold the significance of a sacrament and is connected to one’s salvation,

56 the pursuit of divine wisdom in

Yesod ‘Olam represented a step toward self-rectification and the rectification of the entire world.

57More significantly, Avraham was aware of what we might consider a closely related practice: Kavanah (כוונה). Although not necessarily directly connected, his terminology suggests a potential link. He stated, “YʾʾYHHDYWNʾHHYY, Blessed [is His] Name, Whose glorious kingdom is forever and ever. For the contemplation of this figure should be depicted only at the time of prayer”.

58 During prayer, the practitioner is instructed to mentally depict the name YʾʾYHHDYWNʾHHYY, which is a combination of the names יהוה, אהיה, and אדני. Interestingly, this name is referred to as a form or figure (צורה) rather than a conventional “name”. Given that this צורה serves as an object of contemplation (עיון), it is reasonable to assume that Avraham viewed the

notae, which he considered as the צורה of the spiritual letters representing the ten highest sefirot, as objects of contemplation. This notion aligns with the practice of the

Ars Notoria, in which practitioners also contemplate

notae. Furthermore, Avraham’s strong influence from texts associated with “the ‘Iyyun circle” supports this interpretation.

Interestingly, a codex from the early fourteenth century contains several texts associated with “the ‘Iyyun circle”, including a short treatise on the practice of Kavanah. This treatise, titled “Chapter on The Kavanah by The Ancient Kabbalists”, has been described in detail by Scholem and dated to the years 1280–1300.

59 The anonymous author of this treatise provides instructions to the practitioner on how to approach prayer. One of the key directives is for the individual to “imagine that you are light and that everything around you is light, light from every direction and every side […]” (See ibid). The practitioner is advised to focus on various forms of light during prayer, including brilliant light (אור נגה), shining light (אור הבהיר), and radiant light (אור מזהיר), which are terms that align with Avraham’s descriptions of the tenth, ninth, and sixth paths in

Yesod ‘Olam, respectively. While it may be tempting to draw a direct connection between Avraham’s description of the thirty-two paths and the

notae, suggesting that he saw these

notae as objects of contemplation influenced by his awareness of such practices from different sources, further research is needed to establish a definitive link. Nonetheless, considering the sources available to Avraham, such a connection appears reasonable.

Another interesting point that may have prompted the Kabbalist to draw a comparison between the

notae and the paths is a surprising one—a scribal error. In the earliest known manuscript of the

Ars Notoria, dated to the first half of the thirteenth century (New Haven, Yale University Library, Mellon MS 1),

60 a scribe lists the number of

notae as thirty-two. However, as previously noted by Véronèse, the scribe mistakeably omitted some

notae from the list, despite their presence in the manuscript (Ibid, p. 69). It is, however, quite intriguing: If this scribal error circulated, either in text or through oral transmission, it could have captured the imagination of a reader who is well-versed in

Sefer Yetzirah. However, it still does not fully account for why the

notae were specifically applied to the first ten paths. Nevertheless, the visual similarity between the figures of the ten paths and the

notae of the

Ars Notoria is undeniable.

The significance of this discovery goes beyond just highlighting early Jewish interest in the Ars Notoria, which predates Orgueiri’s translation and adaptation of the Ars (without the notae!) by approximately a century. It also underscores the need for a comparative study that takes into account local and temporal aspects while remaining open to flexible linguistic boundaries. If we are indeed dealing with an attempt from the late thirteenth or early fourteenth centuries to incorporate materials from the Ars Notoria into a Kabbalistic treatise focused on acquiring divine wisdom, and which discusses Kavanah practice and the depiction of the sefirot in an unusual manner, it becomes crucial to reevaluate the influence of Latin magical works on Hebrew Kabbalistic works of the same era and vice versa.

3rd Path

3rd Path