Abstract

The present study aims to test the importance of belonging to religious communities to the frequency of using religious strategies for coping with stress, taking into account the moderating role of identity status and gender. This study used Polish adaptations of two questionnaires: The Religious Coping Questionnaire and the Dimensions of Identity Development Scale. Participants in this study were adolescent and young adult Polish Catholic girls and boys, belonging and not belonging to religious communities. The survey was carried out using the pencil–paper method on a sample of 407 young people with varying degrees of involvement in religious practice. A multivariate analysis of variance showed that the frequency of using positive religious coping strategies differs significantly between groups of people belonging to and not belonging to a religious community. As a result of the study, the interaction of the variable belonging to a religious community and the variable identity status in deciding on the frequency of using positive religious strategies for coping with stress was recognized (F = 2.448; p = 0.033). However, the interaction of these variables with gender did not reach the level of statistical significance (F = 0.655; p = 0.658). Multiple regression analysis indicates that the identity dimension Identification with Commitment explains 14.7% of the frequency of using the Cooperation with God strategy. Belonging to religious communities is significant for the frequency of use of selected religious coping strategies and the intensity of all dimensions of identity development. The results of the statistical analysis showed that identity status is a moderator of the relationship between belonging to religious communities and the intensity of positive religious coping strategies. It was found that the frequency of use of religious coping strategies and the intensity of identity dimensions differed between Polish Catholic girls and boys.

1. Introduction

In the era of postmodernity, there is an increasing tendency to isolate oneself from the social environment (Bauman 1996). The high religiosity of Poles after the death of John Paul II (Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej 2015) is waning, and this also applies to religious practice and membership in Catholic religious communities (such as liturgical services or prayer groups). These changes have further intensified after the pandemic (Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej 2022). For a long time, the number of religious communities have been increasing, also aiming to build a more complete and increasingly satisfied audience (Główny Urząd Statystyczny 2010). Catholic youth groups were very popular in Poland when John Paul II was Pope. Belonging to them—just like belonging to other peer groups—may provide some young people with a sense of security, facilitate orientation in the world of values and norms and their internalization, as well as the choice of life tasks and social roles, provide personal models, and thus is an important factor in the process identity formation. The sense of belonging to a peer group such as a religious community may be particularly important for young people who do not find role models in their immediate family or school environment. Being a member of a group (including a group of a religious community) can also exacerbate identity conflicts among their members (Cohen-Malayev et al. 2009), as well as conflicts with people belonging to other peer groups. Being in relationships with others—as already emphasized above—satisfies many basic human needs and enables one to find a place in the world (Aronson et al. 2012; Oleszkowicz 2006; Czyżowska 2005). The need to belong to a group, identify with it and create interpersonal bonds in the generation of young people is still strong, although in the works of some researchers, there is concern about the threat of disintegration of close interpersonal bonds, and above all, family bonds (Bauman 1994, 2006).

As a consequence of dynamic changes in the socio-cultural context and the progress of civilization, an increasing number of young people may experience frustration due to difficulties in coping with social expectations and requirements. By looking for guidance and support, many young people can become involved in the life of a religious community. Functioning in a peer group (formal or informal) enables the fulfillment of this very important need, but requires acceptance of the group’s values and norms. Otherwise, it may result in ostracism of the group toward a member who does not respect its expectations (Ren et al. 2017), and as a further consequence, the individual internalizes the group’s norms or searches for a new social group and changes the trajectory of developmental changes.

The historical perspective and cultural and geographical setting constitute a chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner and Morris 2006) which is constantly transforming (Białecka-Pikul et al. 2020; Liberska and Suwalska-Barancewicz 2020) and in which group identity and a collective life plan are created—characteristic of social groups’ functioning in a given space–time. When the integrated, internal identity structures developed by an individual are consistent with the group identity to which the individual belongs, this activity may stabilize the development of his or her identity (Liberska 2007). The literature indicates that identity—the “skeleton” of which is the system of values and norms (Brzezińska 2000)—is therefore important for worldview and can be a predictor of religious orientation (Afzal et al. 2020), and may manifest itself in an extrinsic (religion is a tool for achieving goals) and intrinsic (religion is a goal in itself) religious orientation. Religious orientation is important for the development of religious coping strategies (Cruz et al. 2015), but there are still very few reports on this subject, especially in relation to gender.

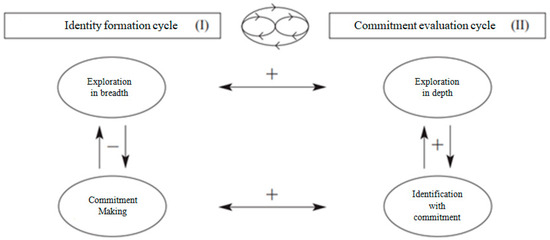

Identity development is a key area of development during adolescence (Erikson 1950, 1968; Liberska 2007). Contemporary research on identity formation in adolescence, accepting its processual nature, is based mainly on the description of identity statuses by J. E. Marcia (1966). He believed that at the end of adolescence, a young person achieves a relatively structured hierarchy of needs and goals, as well as formed views on the issues that interest them. Marcia’s theory was based on Erikson’s (1950, 1968) views on identity formation. According to the concept of psychosocial development, the life cycle follows the principle of epigenesis, in which—in accordance with a specific sequence of phases—specific developmental dilemmas dominate. A positive solution to a given normative crisis contributes to the realization (and expansion) of an individual’s development potential and has a positive impact on solving subsequent development crises. Thus, during adolescence, an individual faces a dilemma: identity vs. role uncertainty (Erikson 1950, 1968). Well-resolved identity problems result in a strong sense of self, the ability to deeply engage in values and ideals and undertake tasks, and the ability to enter into intimate relationships. Avoiding resolving the identity crisis may involve adopting an identity from the immediate environment, from other people, or may result in a significant delay in achieving it. Marcia (1966) developed the identity status theory, which posits the sequential occurrence of two processes. The first of them is “exploration of the social and physical environment, i.e., trialing various social roles, experimenting with available lifestyles, testing one’s own and other people’s limits. The second is making decisions, making choices and assuming related obligations in the areas specified in the exploration process and engaging in their implementation” (Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2009, p. 2). Analyses conducted by Luyckx et al. (2006) show that exploration and commitment in the context of identity development are complex, multi-stage and very dynamic processes that condition and interpenetrate each other. The authors emphasize that both exploration and commitment are two processes that characterize not only adolescence or the phase of emerging adulthood but may become active in further periods of adulthood. The Dual-Cycle Model of Identity Formation assumes connections between the commitment formation cycle and the commitment evaluation cycle and their characteristic identity processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Dual-Cycle Model of Identity Formation. Source: own study based on (Luyckx et al. 2006; Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2010).

In cycle (I), a commitment is formed, in which Exploration in Breadth (i.e., the individual’s search for various alternatives to achieve their goals, values and beliefs) co-occurs with Commitment Making, which indicates making choices and commitments from among the explored alternatives. Cycle (II) shows the evaluation of the commitment, when Exploration in Depth (i.e., an in-depth assessment of the choices made) leads to Identification with Commitment, the essence of which is the internalization of values, norms and roles and a sense of confidence in the decisions made. The authors show that there is a negative correlation between Exploration in Breadth and Commitment Making. The remaining dimensions of identity development, presented in the diagram, are characterized by a positive correlation. In the context of experienced problems that are important for identity development, the process of ruminative exploration may be initiated (Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2010). The formation of identity is the result of solving the crisis related to testing one’s resources and the resources of the living environment, including the social one, which precedes making choices and making decisions obliging one to function in accordance with the internalized system of values, ideology or a specific role. In some circumstances, the proper development of a young person’s identity may fail. An identity that is not adapted to the social environment may develop, which in turn may hinder the individual’s further individual development, but may also hinder the implementation of tasks and roles culturally assigned to a specific stage of life (Erikson 2004). The literature indicates four types of identity: achieved, foreclosure, diffusion and moratorium (Marcia 1980; Bee 1998). An achieved identity is said to happen when an individual has already experienced exploration and is involved in the implementation of values, norms, ideologies and social roles (including family and professional roles). People with foreclosure identity pursue goals, tasks and social roles, but have not explored them before, relying on trust in people significant to them, authorities or their experience. Diffusion identity occurs among people who not only did not engage but also often did not undertake exploration or interrupted it for various reasons. We talk about a moratorium identity when there is no commitment, but individuals actively explore and experiment with their development potential and recognize their capabilities and resources. Socio-demographic changes or traumatic experiences (e.g., death of a loved one) may contribute to the extension of the moratorium, which results in postponing important life decisions regarding choosing an ideology, starting a family or taking up paid work, and thus delaying entry into adulthood (Liberska 2004; Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2009). An excessively long moratorium may result in feelings of distress or discomfort and require support from other people and the use of special coping strategies. Although the literature indicates differences in shaping the identity of young women and men (Gandhi et al. 2015; Morsunbul et al. 2016), according to Erikson’s concept, constructing identity is a developmental challenge that all adolescents must cope with—regardless of gender. Many young people experience difficulties in implementing it and therefore look for different ways to cope with stress.

One of the forms of coping with stress is the turn toward religious strategy (Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Juczyński 2001). Some studies indicate differences between women and men in the frequency of using stress coping strategies related to seeking emotional or instrumental support or emotional venting (Malooly et al. 2017). However, little is known about these differences in religious coping strategies. The concept of religious coping with stress was created by K.I. Pargament, a professor at Bowling Green University, by adapting the interactive approach to stress by Lazarus and Folkman for the needs of the psychology of religion. Coping, in a general sense, is defined as constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to overcome external and/or internal demands that are perceived by the individual as difficult or beyond his or her resources (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). The modification of the known concept of stress and coping with it made it possible to create a new model, i.e., religious coping with stress. Both Lazarus and Folkman’s approach and Pargament’s model fit into the phenomenological–cognitive trend and are characterized by a subjective assessment of the situation and one’s resources, as well as the choice of a coping strategy (Pargament 1997; Talik 2013; McIntosh 1995). Pargament defines coping strategies in relation to the sacred. He understands religious coping with stress as “a constantly changing process by which an individual tries to understand and meet significant personal or situational demands in his or her life” (Talik and Szewczyk 2008, p. 516). Religion can play both positive and negative functions in a person’s life. The literature on the subject indicates that it is a source of meanings (Allport 1988; Park 2005), a source of the value system (Prężyna 2011; Chlewiński 1982), a source of personal development (Jung 1970; Chlewiński 1982; Nielsen 1986; Allport 1988; Furrow et al. 2004; Grzymała-Moszczyńska 2004), performs social (Prężyna 2011; Chlewiński 1982) and auto psychotherapeutic (Kozielecki 1991) functions, and finally performs regulatory (Pargament et al. 2000) and protective functions toward depressive episodes in adolescents (Topalian et al. 2019). On the other hand, there are situations when religion may influence an individual negatively, becoming a source of stress and psychopathology (Grzymała-Moszczyńska 2004). For example, involving religion or excessively referring to its instructions or even to the Person of God in everyday life or attributing to it responsibility for one’s own mistakes may cause an individual to perceive its influence on one’s life as destructive (Pargament 1997). All extreme manifestations of religiosity and spirituality, as well as their denial, may contribute to the creation of threatening situations that may significantly affect the functioning of the individual (Pargament and Zinnbauer 2005). Religion, as well as religious practices, may often play a role in maintaining a neurotic experience of the world (Bartoś 2007). Based on the above division and analysis of the applied processes of giving meaning, as well as coping with difficulties, positive and negative strategies for religious coping with stress have been distinguished (Pargament 1997; Pietkiewicz 2010; Talik 2013).

The religious involvement of community members strengthens the community as a social group and thus makes it easier to find oneself in a relationship with God and the social world. Belonging to a social group, including a religious community, as emphasized above, affects the system of values, norms and goals that constitute the center of the identity of young women and men. Being in a religious community, understood as a socialization environment, is important for the internalization of norms, models and patterns of behavior in various situations, including difficult ones, and strategies for coping with difficulties by young women and men.

The above considerations focused our research interests on the relationship between belonging to a religious community, the construction of the identity of young women and men, as well as ways of coping with difficulties, with particular attention to the strategies of religious coping with difficulties. It is difficult to find studies in the literature on the subject that cover all of the above-mentioned variables—so our research is exploratory. It should be added that due to the gender factor, the designed research is comparative. The reported research project aimed to obtain answers to three research questions regarding the following: (1) differences in the frequency of using religious strategies for coping with stress and the intensity of identity processes in young women and men depending on membership in religious communities, (2) the relationship between the dimensions of identity and religious coping with stress and (3) the importance of identity status and gender for the relationship between belonging to religious communities and religious coping in a group of young Catholics in Poland. Understanding the relationship between community membership, identity dimensions and religious coping strategies of young people may provide the basis for a more complete explanation of the complexity of the conditions for the functioning of contemporary young women and men. It can be assumed that remaining in the exploratory phase will constitute a kind of crisis that may involve a more intensive use of religious coping. The analyses presented here make it possible, to some extent, to verify this assumption.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used the RCOPE Questionnaire (the Religious Coping Questionnaire) and the DIDS (Dimensions of Identity Development Scale). RCOPE (the Religious Coping Questionnaire) by K.I. Pargamenta, in the Polish adaptation by Talik and Szewczyk (2008), was used to identify the frequency of using religious strategies for coping with stress. Religious coping strategies include both positive and negative subscales. The Polish version of the RCOPE questionnaire consists of 105 statements, which, as a result of factor analysis, allowed for the identification of 16 scales for measuring various strategies: 9 positive (Life Transformation, Active Religious Surrender, Seeking Support from Priests/Members, Religious Focus, Collaborative Religious Coping, Pleading for Direct Intercession, Spiritual Support, Religious Practices and Benevolent Religious Reappraisal) and 7 negative (Punishing God Reappraisal, Self-Directing Religious Coping, Demonic Reappraisal, Passive Religious Deferral, Spiritual Discontent, Reappraisal of God’s Power and Religious Discontent). To determine the reliability of the Polish version of the RCOPE questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient was used. For items referring to positive strategies of religious coping with stress, the reliability is higher (α = 0.91) than for items referring to negative strategies of religious coping with stress (α = 0.71) (Talik 2008).

The DIDS (Dimensions of Identity Development Scale) by Luyckx et al. (2008), adapted into Polish by Brzezińska and Piotrowski (2009), was used to measure the intensity of the dimensions of identity development and to determine the identity statuses of the surveyed people. The tool consists of 25 statements that create 5 scales (Exploration in Breadth, Exploration in Depth, Ruminative Exploration, Commitment Making and Identifying with a Commitment). Based on cluster analysis, it is possible to distinguish the following identity statuses: achieved, foreclosure, ruminative moratorium, scattered dispersion, carefree dispersion and undifferentiated (Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2010). All DIDSs have satisfactory reliability (α from 0.70 to 0.85) (Luyckx et al. 2008). The Polish adaptation of the tool (Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2010) should be considered reliable for examining the dimensions of identity development in adolescence, emerging adulthood and early adulthood.

2.1. Study Group

The sampling criterion was the Roman Catholic denomination. All respondents declared themselves believers in God; some of them belonged to religious community structures and some did not. The respondents were classified as belonging to religious Christian communities of the Roman Catholic denomination, creating prayer communities, church music groups and liturgical services—or to a comparison group consisting of young people not involved in the community’s activities. The criterion for inclusion in the study group was also the age of the respondents, including adolescence and the first phase of early adulthood.

The study group consisted of 177 people belonging to religious communities (53.7% girls and women and 46.3% boys and men), and the comparison group included 230 people not belonging to religious communities (66.5% girls and women and 33.5% boys and men) (comparison group). People who were members of religious communities devoted no less than five hours a week to religious practice, unlike people who did not declare their belonging to a community (comparison group) (Z = 9647; p < 0.001). The study participants were aged from 13 to 28, i.e., they were in the period of adolescence, emerging adulthood and the first phase of early adulthood. The average age of the respondents belonging to a religious community was M = 17 years and 11 months, with a standard deviation SD = 2.75, and in the group of people not belonging to a religious community, M = 17 years and 5 months, with a standard deviation SD = 2.09, which indicates that the results are not very dispersed. The median value in the group of people belonging to religious communities was Me = 18, while in the group of people not belonging to religious communities, Me = 17. The study used a purposive sampling procedure. Catholics completed questionnaires during community meetings and in school conditions. The study was comparative; it was conducted among people belonging and not belonging to religious communities (i.e., prayer formation, musical groups and liturgical service), ensuring anonymity and confidentiality of data using the paper-and-pencil method.

2.2. Study Procedure

The subjects were informed about the purpose of the study, and its implementation could only take place after obtaining the consent of the subject or, in the case of minors, after obtaining the written consent of the parent or legal guardian. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The survey was anonymous and voluntary, and consent to participate in the study could be withdrawn at any time. The purpose of the study was purely scientific and the data collected were used in scientific work, including the development of scientific publications. A total of 17 respondents did not answer all questions, so incomplete packs were discarded from further analysis.

2.3. Analysis of Results

The study used moderation analysis, which makes it possible to indicate the variable whose value determines the direction or strength of the main relationship. The presence of a significant moderator was checked using MANOVA analysis (Stanisz 2006). Additionally, a regression model was built. The model was fitted to the data and the variance of the explained variable was explained using multiple regression. In the statistical analysis, the significance level was p ≤ 0.05. All calculations were performed using Statistica 10.0 (Watała 2002).

2.4. Results

1. Shown here are the results of a statistical analysis aimed at answering the question about gender differences in the frequency of using religious strategies for coping with stress and the dimensions of identity development depending on belonging to religious communities.

Firstly, the differential importance of gender for the use of religious coping strategies with stress was recognized. The results showed that gender differences are visible within the three RCOPE strategies in the entire group of respondents; however, belonging to communities significantly modified gender differences in this respect (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differences in the mean results regarding the frequency of using religious strategies for coping with stress in the group of women and men (Mann–Whitney U test, n = 404).

There were statistically significant differences between women and men regarding the following strategies: Life Transformation, Pleading for Direct Intercession and Spiritual Support (all of these strategies were used more often by women than men). In the group of people belonging to communities, there was also a greater use of other positive religious strategies for coping with stress among women. Women most often used the following strategies: Religious Practices, Pleading for Direct Intercession and Collaborative Religious Coping. The strategies used least often by women were Spiritual Discontent, Demonic Reappraisal and Passive Religious Deferral. The surveyed men most often used the following strategies: Religious Practices, Pleading for Direct Intercession and Collaborative Religious Coping. The strategies used least often by men were Reappraisal of God’s Power, Spiritual Discontent and Passive Religious Deferral.

Secondly, gender differences in the intensity of dimensions of identity development were checked. Here, many more differences were noted (Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences in the intensity of dimensions of identity development in women and men (Mann–Whitney U test).

Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between women and men occur in all dimensions of identity development (Table 2). A higher level of intensity of the dimensions of Commitment Making and Identification with Commitment was recorded in the group of men, and of the dimensions of Exploration in Breadth, Exploration in Depth and Ruminative Exploration in the group of women. In the group belonging to a religious community, statistically significant differences were noted between women and men regarding three dimensions: Commitment Making, Identification with Commitment and Ruminative Exploration (p < 0.05). In the group of respondents not belonging to a religious community, statistically significant differences were revealed in all dimensions of exploration: Exploration in Breadth, Exploration in Depth and Rumination Exploration.

2. Shown here are the results of statistical analysis aimed at identifying the relationship between dimensions of identity development and strategies for coping with stress.

It was checked whether there were any correlations between the studied variables. The results showed that all dimensions related to exploration correlate with positive strategies for coping with stress, and Ruminative Exploration additionally correlates with negative strategies for religious coping with stress (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations between the intensity of identity development dimensions and the frequency of using religious coping strategies in the entire group of respondents (Spearman’s R correlation coefficient).

It was then decided to distinguish identity statuses based on the results within the dimensions of identity development. Cluster analysis allowed us to recognize the identity statuses of the respondents, which were selected from the five-dimensional model. Ultimately, six clusters were obtained and treated as qualitatively separate identity statuses (Brzezińska and Piotrowski 2010). In the entire group of respondents, the most common identity status was undifferentiated (25.8%), and the least common was the diffused identity status (11.5%). Among those belonging to a religious community, the most common identity status was undifferentiated (21.5%) and achieved (19.2%), and the least common was the status of diffusion (9.0%). Among those not belonging to a religious community, the most common identity statuses were undifferentiated (29.1%) and carefree diffusion (17.0%), and the least common were the ruminative moratorium statuses (12.2%).

3. Shown here are the results of statistical analysis regarding the importance of identity status for the relationship between belonging to religious communities and religious strategies for coping with stress in a group of Polish Catholics.

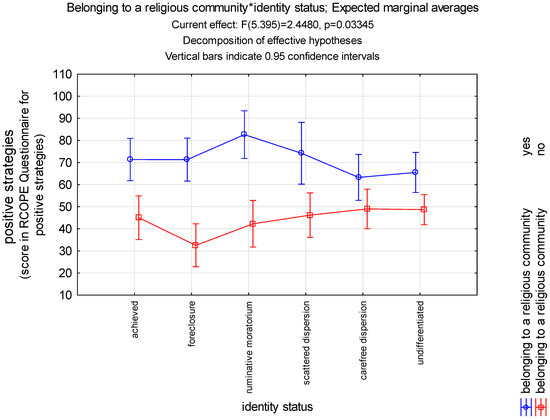

In the next step, relationships between the studied variables were identified using a multivariate analysis of variance. Through the research model, an answer was sought to the question of whether identity statuses moderate the relationship between belonging to religious communities and positive and negative strategies for coping with stress. The multivariate analysis of variance showed that the frequency of using positive religious coping strategies differs significantly between groups of people belonging to and not belonging to a religious community. However, this difference was not noted in groups distinguished according to identity status (Table 4, Figure 2). The statistical analysis showed the significance of the interaction of the variables “belonging to a religious community” and “identity status” with the frequency of using positive religious strategies for coping with stress (p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Results of multivariate analysis of variance of the variable religious coping strategies concerning religious community membership and identity status (MANOVA).

Figure 2.

Chart of the results of a multivariate analysis of variance of the variable positive religious strategies for coping with stress due to belonging to a religious community and identity status. Note: blue indicates the intensity of the use of positive religious strategies for coping with stress among people belonging to religious communities (values marked with a circle), and red—those who do not belong (values marked with a square). Current effect: F(5, 395) = 2.4480, p = 0.03345. Vertical bars indicate 0.95 confidence intervals.

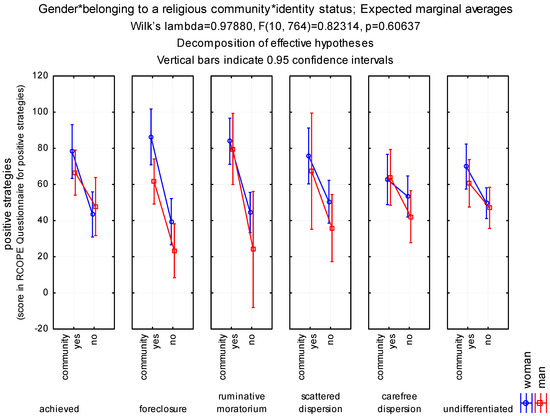

The results of the multivariate analysis of variance showed that the frequency of using positive strategies differs significantly in the gender and religious community groups (p < 0.05), but no differences were found in the identity status groups (p > 0.05). The interaction of the variables “gender”, “belonging to a religious community” and “identity status” with the frequency of using positive religious strategies for coping with stress was observed to be insignificant (p > 0.05). The purpose of the last analyses was to provide information on the importance of gender in relation to religious coping strategy, taking into account its interaction with variables such as “religious community membership” and “identity status”. However, the interaction between “belonging to a religious community” and “identity status” turned out to be significant (p < 0.05) (Table 5, Figure 3).

Table 5.

Results of multivariate analysis of variance of the variable strategies for coping with stress in relation to gender, belonging to a religious community and identity status (MANOVA).

Figure 3.

Chart of the results of a multivariate analysis of variance of the variable positive religious strategies for coping with stress in relation to gender, belonging to a religious community and identity status. Note: blue indicates the intensity of the use of positive religious strategies for coping with stress in women (values marked with a circle), and red, that in men (values marked with a square). Wilks’ Lambda = 0.97880, F(10, 764) = 0.82314, and p = 0.60637. Vertical bars indicate 0.95 confidence intervals.

In addition, to enrich and detail the analyses so far, it was decided to present a regression analysis, but treating both sexes together. The statistical analysis carried out indicated significant correlations between the explanatory variable, which is belonging to a religious community, and the explained variable—a positive strategy of religious coping with stress called Collaborative Religious Coping—and between the explanatory variable, which is the dimension of identity development Identification with Commitment and the above variables (Table 6). Therefore, an attempt was made to build a regression model illustrating the impact of the above-mentioned explanatory variables on the explained variable in the indicated range. A regression analysis was performed on relationships in which statistical significance was noted. Its results confirmed the significance of the assumed regression model (p < 0.001). As a result of the regression analysis, a statistically significant model (1) was obtained, including one significant predictor (the Identification with Commitment dimension) and explaining 14.7% of the variance of the Collaborative Religious Coping variable [R2 = 0,154; F(3, 403) = 24.506; p < 0.001].

Table 6.

Results of multiple regression analyses for the dependent variable: Collaborative Religious Coping.

3. Discussion

This study aims to test the importance of belonging to religious communities to the frequency of using religious strategies for coping with stress (Pargament 1997), taking into account the moderating role of identity status (Luyckx et al. 2006) and gender. The literature indicates differences between women and men in religious practice, coping and the development of identity (Gandhi et al. 2015; Kalka and Karcz 2016; Morsunbul et al. 2016). The research results show that women and men differ in their choice of religious coping strategies and the dimensions of identity development. This should be understood through the prism of various conditions. Women’s more frequent use of positive RCOPE strategies may be associated with a tendency to confide in other women, especially close ones, and to focus on emotions and social relationships (Wojciszke 2002, 2012). This may manifest itself in taking on the role of confidante, caregiver and mother. Being in an emotionally strong relationship with God, expecting spiritual support, intervention and changes, may be an expression of a deeper experience of contact with the Absolute, but also of treating God as the one who can do more because God has greater power and agency than a woman. Polish research shows that the choice of negative religious coping strategies is associated with less personal strength in girls and less perseverance in boys (Talik 2013). It should be emphasized that girls and boys carry out religious practices to different extents, have different characteristics and take on different social roles in different areas of activity, and also show differences in the process of giving meaning in difficult situations (Spencer et al. 2003). Women and men also differ in the intensity of their religious attitudes. Sensory sensitivity and the strength of the inhibition process in the group of women correlate positively with religious attitudes, which is not observed in the group of men (Marcysiak 2009).

What is also interesting is the different functioning of women and men in the context of identity status. Gender differentiates all results within the dimensions of identity development. Men achieve higher scores in the dimensions of Making Commitments and Identification with Commitments, while women and girls achieve higher scores in all areas of exploration: Exploration in Breadth, Exploration in Depth and Rumination Exploration. On the above basis, it cannot be ruled out that men begin exploration earlier or that it reaches a higher intensity earlier than in women (according to K. Luyckx’s theory), which in turn may result in men making commitments and identifying with them earlier compared to women. These differences can be associated with gender stereotypes, which include greater decisiveness, self-confidence, speed of decision making and focus on the chosen action and goal in men, and greater reflection, attentiveness in action, agreeableness and submissiveness in women. It is worth adding that one of the conditions for the above changes may not only be biological or rely on genetic differences between the sexes but may also be related to upbringing in the family home or broadly understood socialization. This requires further research because the literature on the subject often indicates a certain shift in the time of developmental changes in many areas for women and girls compared to men and adolescent boys (Obuchowska 1996)—with opposite characteristics to those identified in the reported studies. We cannot reject the assumption that these differences indicate that men were taking over their identity earlier—or prematurely. However, this may be the result of the different socialization of girls and boys, and above all, greater social permission for boys to experiment in various roles, in various spheres of activity and at an earlier age. Women and girls who do not belong to communities similarly score higher on the exploration dimensions compared to those who belong to communities. Women and girls from communities achieve higher results than those not belonging to communities in the dimension of identity development, which is Ruminative Exploration. However, a slightly different tendency is observed in the group of men belonging to religious communities, namely that they achieve higher results in the dimensions of Making Commitments and Identification with Commitments than men who do not belong to communities. This may indicate a higher level of anxiety in the group of women belonging to communities, which may consequently be associated with reluctance to make commitments and identify with them. Based on the research results, it may be possible to consider the possibility of a lower level of fear or anxiety among men from communities compared to men who do not belong to communities. The above confirms the different impact of belonging to a community on the psychological condition of women and men.

The obtained research results indicate a correlation between positive religious coping strategies with stress and the dimensions of exploration within identity construction. This means that the search for oneself is accompanied by finding one’s relationship with God, which is confirmed by a statistically significant result in the positive strategies of religious coping with stress. Ruminative Exploration additionally correlates with negative religious coping strategies, which confirms the anxious nature of both of these mechanisms. The interaction of the variable belonging to a religious community and the variable identity status in making decisions about the frequency of using positive religious strategies for coping with stress was recognized. This interaction is not observed in the case of negative religious coping strategies, nor when taking into account age group or gender. This finding seems to be very important from the point of view of practical research implications. By supporting the development of central mental structures, such as identity, one can stimulate young Catholics to develop positive religious strategies for coping with stress. It may also be important for the postmodern religious identity of young Poles (Pankalla and Wieradzka 2014), which is directly related to the development of personal identity. It is also an important field for cooperation between theology and psychology aimed at shaping positive strategies for dealing with difficulties through the mature construction of one’s own identity and group identity.

The identity dimension Identification with Commitment turned out to be a significant predictor of the frequency of using one positive strategy of religious coping with stress, which is Collaborative Religious Coping. This may indicate an internalized belief in living in harmony with God, in trust and identification with the role of a child of God, and even in the certainty that what happens to a person, even crises and other difficult experiences, is part of God’s plan. Such understanding can be considered an indicator of full integration of the individual’s psychological structure and may refer to authentic religiosity (Walesa 2005). In such circumstances of identity development, confrontation with crises should not be reflected in doubt in God but rather should involve trusting in God, and even if doubt appears, in undertaking a new exploration, remaining nevertheless convinced that what happens is God’s will and maintaining one’s ability to seek solutions in cooperation with God. Religiosity and the consequences that it involves may be important for the development of identity, including sexual identity (Shilo et al. 2016; Lauricella et al. 2017; Kumpasoğlu et al. 2020), but this topic was not included in the described examination. Nevertheless, what seems interesting is how the religious coping strategies used may influence the development of identity, which is worth analyzing in future research. To sum up, it is worth emphasizing that belonging to a religious community and identification with its group’s values may stabilize the development of an individual’s identity and thus may result in the intensification of the use of positive religious coping strategies with stress.

4. Conclusions

The analyses performed provided the basis for formulating the following conclusions:

- (1)

- There are differences between young women and men in the frequency of using religious strategies for coping with stress (girls are more likely to count on life transformation, intervention or spiritual support) and in the intensity of identity processes (boys are more likely to engage in and identify with it, girls are more likely to explore)—depending on membership in a religious community.

- (2)

- There is a relationship between identity dimensions and religious coping with stress, which was observed only in exploration processes.

- (3)

- Although women and men differ in their choice of religious coping strategies and the intensity of their identity dimensions, identity status, not gender, moderates the relationship between membership in a religious community and religious coping with stress.

Limitations of this Study

The majority of Poles declare Roman Catholic denomination (Główny Urząd Statystyczny 2015), but the significance of affiliation with religious communities was not examined for religious communities in other denominations. In future research, it would be worth taking into account other religions and making cross-cultural comparisons, as well as examining connections with psychological variables other than those included in the cited study. Moreover, increasing the size of the research group would help increase the credibility of the presented results. Including people in different developmental periods could provide the basis for drawing conclusions about developmental changes in the explored area. The cross-sectional nature of this study limits the interpretation of the results, showing only areas for further verification, and consequently, the conclusions cannot go beyond the current socio-cultural context. The issue of stereotypes and the need for social acceptance also seems to be very important in connection with the research procedure (Aronson et al. 2012). Further research could find other psychological variables that are important for religious coping because support from a religious group translates into religious coping in quite a direct, perhaps even obvious, way. The completed survey, apart from the limitations indicated, is a source of valuable information about the mental health of young Catholics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P. and H.L.; methodology, N.P. and H.L.; formal analysis, N.P.; data curation, N.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.P. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, N.P. and H.L.; supervision, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The survey was anonymous and voluntary and consent to participate in the study could be withdrawn at any time. The purpose of this study was purely scientific and the data collected were used in scientific work, including the development of scientific publications. This study was verified and received the approval of the Rector of the Seminary of the Diocese of Bydgoszcz (10 March 2015), apart from the priests from the various parishes or group supervisors who were introduced to the study concept and gave their consent to the study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. In the case of minors, such consent was also given by parents or legal guardians.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available at the Open Science Frame-work (https://osf.io/c7rjm/ (accessed on 8 July 2022)).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Afzal, Anila, Najma Iqbal Malik, and Mohsin Atta. 2020. Impact of Identity Styles on Religious Orientations in Adolescents. Pakistan Journal of Psychology 51: 35. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon. 1988. Osobowość i Religia. Warszawa: PAX. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, Elliot, Timothy D. Wilson, and Robin M. Akert. 2012. Psychologia Społeczna. Serce i Umysł. Poznań: Zysk i S-ka. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoś, Tadeusz. 2007. Wolność, Równość, Katolicyzm. Warszawa: W.A.B. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 1994. Dwa Szkice o Moralności Ponowoczesnej. Belarus: Instytut Kultury. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 1996. Etyka Ponowoczesna. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2006. Płynna Nowoczesność. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Bee, Helen. 1998. Psychologia Rozwoju Człowieka. Poznań: Zysk i S-ka. [Google Scholar]

- Białecka-Pikul, Marta, Arkadiusz Białek, and Martyna Jackiewicz-Kawka. 2020. Środowiskowe Uwarunkowania Rozwoju I Wychowania W Okresie Dzieciństwa. In Psychologia Wychowania: Wybrane Problemy. Edited by Hanna Liberska and Janusz Trempała. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, pp. 241–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie, and Pamela A. Morris. 2006. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed. Edited by William Damon and Richard M. Lerner. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 1, pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezińska, Anna. 2000. Społeczna Psychologia Rozwoju. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezińska, Anna, and Konrad Piotrowski. 2009. Diagnoza statusów tożsamości w okresie adolescencji, wyłaniającej się dorosłości i wczesnej dorosłości za pomocą Skali Wymiarów Rozwoju Tożsamości (DIDS). Studia Psychologiczne 47: 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Brzezińska, Anna, and Konrad Piotrowski. 2010. Polska adaptacja Skali Wymiarów Rozwoju Tożsamości (DIDS). Polskie Forum Psychologiczne 15: 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. 2015. Zmiany w Zakresie Podstawowych Wskaźników Religijności Polaków po Śmierci Jana Pawła II. Warszawa: Fundacja CBOS. [Google Scholar]

- Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. 2022. Zmiany Religijności Polaków po Pandemii. Warszawa: Fundacja CBOS. [Google Scholar]

- Chlewiński, Zdzisław. 1982. Psychologia Religii. Lublin: KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Malayev, Maya, Avi Assor, and Avi Kaplan. 2009. Religious Exploration in a Modern World: The Case of Modern-Orthodox Jews in Israel. Identity 9: 233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, Ortega, Daniel Gutierrez Luis G., and Dennis Waite. 2015. Religious Orientation and Ethnic Identity as Predictors of Religious Coping Among Bereaved Individuals. Counseling & Values 60: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżowska, Dorota. 2005. Grupa. In Słownik Psychologii. Edited by Jerzy Siuta. Warszawa: Zielona Sowa. 96p. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Erik. 1950. Childhood and Society. Montgomery: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Erik. 1968. Identity, Youth, and Crisis. Montgomery: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Erik. 2004. Tożsamość a Cykl Życia. Poznań: Zysk i Ska. [Google Scholar]

- Furrow, James L., Pamela Ebstyne King, and Krystal White. 2004. Religion and Positive Youth Development: Identity, Meaning, and Prosocial Concerns. Applied Developmental Science 8: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, Amarendra, Shubhada Maitra, Koen Luyckx, and Laurence Claes. 2015. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Identity Distress in Flemish Adolescents: Exploring Gender Differences and Mediational Pathways. Personality & Individual Differences 82: 215–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2010. Stowarzyszenia, Fundacje i Społeczne Podmioty Wyznaniowe w 2008 r. Studia i Analizy Statystyczne. Warszawa: Departament Badań Społecznych. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 2015. Wartości i Zaufanie Społeczne w Polsce w 2015 Roku; Warszawa: Departament Badań Społecznych. Available online: http://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5486/21/1/1/wartosc.i_i_zaufanie_spoleczne_w_polsce_w_2015r_.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Grzymała-Moszczyńska, Helena. 2004. RELIGIA a Kultura. Wybrane Zagadnienia z Kulturowej Psychologii Religii. Kraków: UJ. [Google Scholar]

- Juczyński, Zygfryd. 2001. Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Carl Gustaw. 1970. Psychologia A Religia. Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza. [Google Scholar]

- Kalka, Dorota, and Bartosz Karcz. 2016. Identity Dimensions versus Proactive Coping in Late Adolescence While Taking into Account Biological Sex and Psychological Gender. Polish Psychological Bulletin 47: 300–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kozielecki, Jerzy. 1991. Z Bogiem Albo bez Boga. Psychologia Religii: Nowe Spojrzenie. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpasoğlu, Güler Beril, Dilara Hasdemir, and Deniz Canel-Çınarbaş. 2020. Between Two Worlds: Turkish Religious LGBTs Relationships with Islam and Coping Strategies. Psychology & Sexuality 13: 302–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauricella, Shauna, Russell Phillips, and Eric Dubow. 2017. Religious Coping with Sexual Stigma in Young Adults with Same-Sex Attractions. Journal of Religion & Health 56: 1436–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard, and Susanne Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Liberska, Hanna. 2004. Perspektywy Temporalne Młodzieży. Wybrane Uwarunkowania. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM. [Google Scholar]

- Liberska, Hanna. 2007. Specyfika Kształtowania się Tożsamości Współczesnej Młodzieży. In Z Zagadnień Rozwoju Psychologii Człowieka. Edited by Elżbieta Rydz and Dagmara Musiał. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego im. Jana Pawła II, pp. 143–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liberska, Hanna, and Dorota Suwalska-Barancewicz. 2020. Środowiska Rozwoju i Wychowania: Od Dzieciństwa do Dorosłości. In Psychologia Wychowania. Wybrane Problemy. Edited by Hanna Liberska and Janusz Trempała. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, pp. 253–80. [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx, Koen, Luc Goossens, and Bart Soenens. 2006. A Developmental Contextual Perspective on Identity Construction in Emerging Adulthood: Change Dynamics in Commitment Formation and Commitment Evaluation. Developmental Psychology 42: 366–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, Koen, Michael D. Berzonsky, Seth J. Schwartz, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Bart Soenens, Ilse Smits, and Luc Goossens. 2008. Capturing Ruminative Exploration: Extending the Four-Dimensional Model of Identity Formation in Late Adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality 42: 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malooly, Ashley M., Kaitlin M. Flannery, and Christine McCauley Ohannessian. 2017. Coping Mediates the Association between Gender and Depressive Symptomatology in Adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development 41: 185–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, James E. 1966. Development and Validation of Ego-Identity Status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 3: 551–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, James E. 1980. Identity in Adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Edited by Joseph Adelson. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 159–87. [Google Scholar]

- Marcysiak, Irena. 2009. Temperament A Religijność. In Osobowość i Religia. Edited by Henryk Gasiul and Emilia Wrocławska-Warchala. Warszawa: ADAM, pp. 239–52. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, Daniel N. 1995. Religion-as-Schema, With Implications for the Relation Between Religion and Coping. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsunbul, Umit, Figen Cok, Elisabetta Crocetti, and Wim Meeus. 2016. Identity Statuses and Psychosocial Functioning in Turkish Youth: A Person-Centered Approach. Journal of Adolescence 47: 145–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Michael E. 1986. Religia, Psychoterapia i Opieka Duszpasterska. Religia i Psychoterapia. In Psychologia Religii. Wybór Tekstów. Edited by Halina Grzymała-Moszczyńska. Kraków: Instytut Religioznawstwa UJ, pp. 162–85. [Google Scholar]

- Obuchowska, Irena. 1996. Drogi Dorastania. Psychologia Rozwojowa Okresu Dorastania dla Rodziców i Wychowawców. Warszawa: WSiP. [Google Scholar]

- Oleszkowicz, Anna. 2006. Bunt Młodzieńczy. Uwarunkowania. Formy. Skutki. Warszawa: Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- Pankalla, Andrzej, and Anna Wieradzka. 2014. Ponowoczesna tożsamość religijna młodych Polaków z perspektywy koncepcji Jamesa Marcii i Koena Luyckxa. Annales Universitatis Paedagogicae Cracoviensis, Studia Sociologica 6: 163–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping. Theory, Research, Practice. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., and Brain J. Zinnbauer. 2005. Religiousness and Spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa M. Perez. 2000. The Many Methods of Religious Coping: Development and Initial Validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 519–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2005. Religion as a Meaning-Making Framework in Coping with Life Stress. Journal of Social Issues 61: 707–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietkiewicz, Igor. 2010. Strategie copingu religijnego w sytuacji utraty—Implikacje do terapii. Czasopismo Psychologiczne 2: 289–99. [Google Scholar]

- Prężyna, Władysław. 2011. Genotypiczny i Fenotypiczny Wymiar Religijności. In Psychologiczny Pomiar Religijności. Edited by Marek Jarosz. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL, pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Duarte, Andrew H. Hales, and Kaye Williams. 2017. Ostracism: Being Ignored and Excluded. In Ostracism, Exclusion, and Rejection. Edited by Kipling D. Williams and Steve A. Nida. New York: Routlege Taylor Francis Group, pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shilo, Guy, Ifat Yossef, and Riki Savaya. 2016. Religious Coping Strategies and Mental Health Among Religious Jewish Gay and Bisexual Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior 45: 1551–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, Margaret B., Suzanne G. Fegley, and Vinay Harpalani. 2003. A Theoretical and Empirical Examination of Identity as Coping: Linking Coping Resources to the Self Processes of African American Youth. Applied Developmental Science 7: 181–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisz, Andrzej. 2006. Przystępny Kurs Statystyki z Zastosowaniem STATISTICA PL na Przykładach z Medycyny. Kraków: StatSoft Polska Sp. z o. o. [Google Scholar]

- Talik, Elżbieta. 2008. Religijne i poza-religijne strategie radzenia sobie ze stresem a poczucie kontrolowalności sytuacji stresowej u młodzieży. Doctoral dissertation, Wydział Nauk Społecznych, Uniwersytet Szczeciński, Szczecin, Poland. [Google Scholar]

- Talik, Elżbieta. 2013. Jak Trwoga, To Do Boga? Psychologiczna Analiza Religijnego Radzenia Sobie ze Stresem u Młodzieży w Okresie Dorastania. Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne. [Google Scholar]

- Talik, Elżbieta, and Leszek Szewczyk. 2008. Ocena równoważności kulturowej religijnych strategii radzenia sobie ze stresem na podstawie adaptacji kwestionariusza RCOPE—Kennetha I. Pargamenta. Przegląd Psychologiczny 4: 513–38. [Google Scholar]

- Topalian, Alique, Keith A. King, and Rebecca A. Vidourek. 2019. Religiosity and Depression among a National Sample of Adolescents. American Journal of Health Studies 34: 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walesa, Czesław. 2005. Rozwój Religijności Człowieka: Dziecko. Lublin: KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Watała, Cezary. 2002. Biostatystyka—Wykorzystanie Metod Statystycznych w Pracy Badawczej w Naukach Biomedycznych. Bielsko-Biała: Alfa Medica Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke, Bogdan. 2002. Kobiety i Mężczyźni: Odmienne Spojrzenia na Różnice. Gdańsk: GWP. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke, Bogdan. 2012. Psychologiczne różnice płci. Wszechświat 113: 13–18. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).