Abstract

The emotional, physical, and spiritual health of athletes continues to be a concern at all levels of sport. With respect to emotions and health, previous studies have sought to understand the role of normalization of emotion on elite female rowers’ decisions to train regardless of their health. This research demonstrated how athletes may be persuaded to accept that emotions are negative, irrational, and weak, and this may play a significant role in subsequent unhealthy behaviours. In turn, these findings have generated further explorations into a more comprehensive emotion education for all athletes, which have focused on athletes’ emotional awareness and spiritual growth. The present paper provides theoretical, educational, and practical insight into the areas of emotion and spiritual development. In doing so, it presents a conceptual model for sport chaplains, coaches, and/or sport advocates for educating and mentoring the emotional and spiritual formation of athletes.

1. Introduction

The emotional, physical, and spiritual health of athletes continues to be an overriding concern for sport chaplains, sport advocates, coaches, and athletes at all levels of sport (Åkesdotter et al. 2020; Biggin et al. 2017; Howe 2004; Jones et al. 2020; Moseid et al. 2018; Sabato et al. 2016). Researchers have gone so far as to question whether or not elite sport and health present a contradiction in terms (Baker et al. 2014; Safai et al. 2014). In pursuit of a deeper understanding of emotion norms and health in sport, previous research with elite female rowers drew upon Foucault’s (1977) concept of normalization and applied this to emotions. The normalization of emotion (Lee Sinden 2010, 2013) is the process by which sport environments work to regulate, shape, and coerce athletes to conform to certain emotion norms. This previous research with rowers explored how certain emotion norms, or beliefs about emotion, (referred to as ‘technologies of emotion’), were normalized and impacted athletes’ decisions to train irrespective of their health (Lee Sinden 2010, 2013). The results showed that unhealthy beliefs about emotions were socialized through normalizing methods in rowing environments and these beliefs played an influential role in athletes’ decisions to continue training despite their health. In particular, these beliefs persuaded athletes to ignore their thoughts and feelings, and subsequent health issues, because they did not want to appear weak and/or negative. As a consequence, the athletes exacerbated their health problems and suffered adverse health during and after retirement (Lee Sinden 2010).1

This previous research with rowers confirms and adds weight to wider findings with respect to normalization of emotion and health problems (Coker-Cranney et al. 2018; Curry 1993; Hughes and Coakley 1991; Smith 2008; Wacquant 1998; White et al. 1995; Young et al. 1994). Over conformity, for instance, refers to athletes adhering strictly to the norms and values of their sport ethic; beliefs about what it means to be an athlete; and the importance of striving for distinction and striving for excellence (see Hughes and Coakley 1991). Hughes and Coakley (1991) argue that while over conformity can have positive effects such as enhancing performance and dedication, it can also have negative consequences such as burnout and unethical behaviour.

The normalization of emotion and over conformity shed light on the complexities of conforming to the sport ethic and its impact on athlete wellbeing and behaviour, and provide grounds for the construction of a more comprehensive emotion education plan for athletes. In addition, as Christian researchers, we seek to understand the relationship between beliefs about emotion, unhealthy behaviours, and spiritual formation among Christian athletes. Mosley et al. (2015) also examined the role of spirituality in the lives of Christian athletes, and how it influenced their athletic performance and overall wellbeing. They found that spirituality played a significant role in providing athletes with a sense of purpose, motivation, and resilience. It also served as a source of support and guidance in times of adversity. These findings further highlight the importance of considering spiritual formation as a factor in understanding and supporting athletes’ mental and emotional wellbeing.

The past 10 years have witnessed many informal discussions and casual conversations with Christian university athletes about emotions, health, and spiritual formation in sport. Importantly, Swain and King (2022) validate the use of such conversations in research, particularly when added to more formal means of data collection. Through these discussions and conversations, it became evident that unhealthy beliefs about emotion and athletes’ decisions to train despite health issues are common occurrences among Christian university athletes. This initiated a more formal qualitative investigation into understanding the role of normalization of emotion in Christian sport settings and Christian athletes’ disregard of health problems. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with five former Christian university athletes who played soccer, basketball, and volleyball during their tertiary education, and who trained despite injuries and other health problems. While preliminary, the responses from the interviews revealed that unhealthy beliefs about emotion were influential in the respondents’ perceptions and regulation of their emotions, and decisions to train despite adverse health. Additionally, each athlete felt pressure to express and act in ways that were consistent with what they believed to be expectations or virtues of being Christians. For instance, one athlete said, “Christians are supposed to be self-controlled, not anxious or angry”. Another athlete explained, “When I get upset or show my emotions, I feel like others think I am not leaning on the Lord, or trusting Him as I should” (Lee Sinden 2023). These initial responses highlight the need to be aware of the messages being perpetuated among Christian athletes, particularly in conjunction with their spiritual formation, which confirms and adds weight to other research findings on spiritual formation in sport (Bounds 2022; Egli and Hoven 2020; Stevenson 1991). For instance, while it is important to teach, recognize, and model good character and/or virtues (Bounds 2022; Schnitker et al. 2020a, 2020b), spiritual formation requires a deeper examination of the heart (Egli and Hoven 2020; Willard 1988). Further, if we focus mainly on outward behaviours in sport, this increases the likelihood of athletes behaving in socially desirable ways, also referred to as socially desirable responding (Gross et al. 2017). This is another example of normalization that leads to a spiritual performance-based identity, where athletes strive to appear spiritually together yet fail to examine what is really going on in their hearts. Jonathan Edwards asserts that not everything that appears virtuous is true virtue. There is a distinction to be made between some actions and dispositions, which are truly beautiful and virtuous, and others which only seem or appear to be so, through a partial, superficial, and imperfect view of things (Edwards [1791] 2003). True virtue is the beauty of the qualities and exercises of the heart, which only consist in Christ’s love, growing in the Spirit of God (Augustine [1871] 2017; Edwards [1749] 2014, [1791] 2003; English Standard Version [ESV] (ESV 2009, 1 John 4:10)). Thus, without Christ’s love, there is no true virtue and no real spiritual growth. Moreover, Christ’s love is the greatest virtue (ESV 2009, 1 Cor. 13:13); without it we have nothing, we are nothing, and our words are a “noisy gong or a clanging cymbal” (ESV 2009, 1 Cor. 1:1–3).

Rather than coaching athletes to ignore their emotions and/or act in normalized ways, Dabrowski (1964) addresses the heart of athletes in his explanation of the third factor. The third factor (in addition to nature and nurture) is the role that athletes play in their own development, which is fuelled by a heartfelt desire to grow (Jensen 2011). This is not merely about changing and fixing or attaining and achieving; it is the transformation of the heart and mind, which requires the recognition and understanding of one’s emotions. Emotions are not in the way, they are the way to transcending what you would like to be less like you, towards what you would like to be more like you (Dabrowski 1964). As Christians, we are concerned with spiritual transformation, or “the process of being conformed into the image of Jesus Christ” (Mulholland and Barton 2016, p. 7), also referred to as spiritual formation and/or sanctification (ESV 2009, Eph. 4:22–24);

Nouwen (2010) calls this “the way of the heart” while Palmer (2009) captures this spiritual process of living out of your ‘authentic self’ by calling Christians to “live undivided”. This is echoed in Macchia’s (2022) challenge to “practice a preference for God”.… to put off your old self, which belongs to your former manner of life and is corrupt through deceitful desires, and to be renewed in the spirit of your minds, and to put on the new self, created after the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness.

Sport provides a distinctive opportunity for the spiritual formation of athletes through an awareness of their emotions. This is because within the context of sport, it is common for intense emotions to be triggered (Jekauc et al. 2021), revealing what is truly in athletes’ hearts. Thus, a central aim of the present paper is to provide an educational and mentoring approach to athlete spiritual development, such as one-on-one (or group) emotion education sessions to help athletes understand what their emotions are telling them. We realize that this relational approach to coaching is more time-consuming than approaches serving to normalize emotions, thereby adding to the emotional labour (Hochschild 1983; Devall-Martin 2017; Grandey 2000) of those working with athletes. However, we also understand that this journey takes time and requires the development of trusting relationships between athletes and helping professionals (Holm 2009; Jones et al. 2020; Marinese 2016; Paget and McCormack 2006; Parker and Manley 2016; Threlfall-Holmes and Newitt 2011), and the work of the Holy Spirit (ESV 2009, Col. 1:9). This work requires gently speaking into athletes where they are at, or shepherding them (Clemens 2008; Jones et al. 2020; Waller and Cottom 2016), to understand the relationship between their emotions and the condition of their hearts. We believe that educating and walking with athletes in this way helps diminish unhealthy emotion norms, disrupts the development of a performance-based identity, and leads athletes to spiritual growth and overall wellbeing. The following discussion provides an innovative and clinical educational approach that can be used practically in the emotion education and development of athletes.

2. Understanding Emotion

Concisely defining ‘emotion’ is difficult simply because the term makes for misunderstandings and contradictions in theory and research (Izard 2009). Research on emotion has been approached from various theoretical positions. As a result, researchers continue to explore alternative meanings and understandings (Oatley and Jenkins 1992, 1996; Lee Sinden 2014). Nevertheless, for the purpose of understanding the basic components of emotion, we use the following working definition. In short, emotions are “a state of arousal involving facial and bodily changes, brain activation, cognitive appraisals, subjective feelings, and tendencies toward action, all shaped by cultural rules” (Wade et al. 2007, p. 388). This definition recognizes emotions as a state of arousal, occurring when an event is relevant to a person’s goal. Emotions are also cognitively based; our thought processes affect further judgments and cognitive appraisal (Damasio 1994; Frijda 1986; LeDoux 1994). Oatley and Jenkins (1996) explain cognitive appraisal as one of a multitude of ways a person experiencing an emotion evaluates that emotion as pleasant or unpleasant. Furthermore, this definition takes into consideration the complexities of socializing factors and environmental influences on the understanding and conceptualizing of various emotions (Levy 1984). Social science researchers have accounted for worldwide emotional variation and assert that emotions are influenced by forces of culture and language (Daniels 2001; Vygotsky cited in Dunn 1994; Rosaldo 1989; Wittgenstein 1958). Christian researchers recognize that emotions are subjective experiences regarding “what the world is like, who we are, and what God has done for us” (Roberts 2007, pp. 30–31).

3. Clinical Sport Psychology: The Integrated Model of Athletic Performance (IMAP)

Educational sport psychology, also known as traditional sport psychology, has sought to understand emotion with respect to performance and has provided many strategies to address emotions and problems faced by athletes in their sport settings (Crocker et al. 2021; Weinberg and Gould 2018). These strategies largely comprise cognitive and behavioural skills training, such as imagery, self-talk, arousal regulation, and/or goal setting (Weinberg and Gould 2018). While these techniques have demonstrated a degree of usefulness, they have been criticized by clinical sport psychologists as disconnected, falling short of addressing deeper issues, and failing to develop the athlete holistically (Gardner and Moore 2007; Stainback et al. 2007). As a result, sport counselling and clinical interventions have emerged, viewing athlete development as a complex activity that involves a few highly interconnected components that require an Integrated Model for Athletic Performance (IMAP) (Gardner and Moore 2007). The IMAP is made up of four components: (a) instrumental competencies: the specific physical and sensorimotor skills and abilities, such as the ability to shoot a free throw or fitness level; (b) environment and performance demands: the competitive, interpersonal, situational, and organizational circumstances, such as style of coach, training demands, and/or team cohesion/dynamics; (c) dispositional characteristics: intrapersonal variables, such as thought patterns, behaviour, and personality, which influence how an athlete perceives, interprets, and responds to the performance demands; and (d) behavioural self-regulation: cognitive, affective, physiological, and behavioural processes, such as awareness, understanding, and processing of emotions. For the purposes of the present discussion, we focus on two of the four components of this model, namely dispositional characteristics and behavioural self-regulation.

Dispositional characteristics serve as a basis for understanding the world around us, and positively and negatively control our emotional (affective) responses. The main dispositional characteristics in clinical sport psychology are schemas. Schemas are broad, pervasive themes or patterns, usually developed in childhood or adolescence, including memories, bodily sensations, emotions, and cognitions, regarding oneself and one’s relationships with others (Young et al. 2003). Maladaptive schemas are patterns of thinking that inhibit proper ways of viewing the world and behavioural processes. For instance, an ‘unrelenting standards/hypercriticalness’ maladaptive schema leads a person to strive to meet extreme and rigid standards. This maladaptive schema is associated with perfectionism and obsessiveness and is common among athletes, often leading them to feel exhausted, irritated, or anxious. Keeping up with their own internal and unrealistic standards eventually causes intense pressure and harm to their performance and overall health and wellbeing (Young et al. 2003).2 We add the previously developed beliefs about emotion (Lee Sinden 2010, 2013) as another type of dispositional characteristic that can inhibit behavioural self-regulation; disrupting a healthy process of emotion. For example, this was evident in the case of the elite rowers when their beliefs about emotions led them to ignore their concerns about training, and subsequently trained despite their health issues (Lee Sinden 2010, 2013, 2014). The following explains beliefs about emotion and the emotion process in more detail.

4. Beliefs about Emotion

Emotion norms continue to be visible in sport in various ways. For instance, they are embedded in sport slogans, like Just do it, which has been a revered trademark of shoe company Nike since 1988. Interestingly, this slogan was taken from the final words of a violent criminal who murdered two men in cold blood before he was put to death for his crimes (Fairs 2005). While phrases and slogans are meant to inspire a desired ‘toughness’ in sport, they often send a negative message about thinking and feeling. These messages are also misconstrued outside of sporting contexts. For example, ‘Nike Terrorist’ was a name that was coined to describe self-starting terrorists who used unsophisticated methods to carry out deadly acts like the 2013 suicide bombing in Birmingham, UK. These terrorists wore the Nike slogan on their shirts, publicizing the message to not think or feel, and Just do it as their motto when committing acts of terrorism (Coughlin 2012). Such slogans and incidents contextually normalize emotions, leaving little room for alternative thinking.

In order to better understand the role of emotion norms, in the previous research with elite female rowers, a historical analysis was conducted and a theoretical framework was constructed (Lee Sinden 2013). The following five specifically developed beliefs about emotion were created, also referred to as technologies of emotion (see Lee Sinden 2010, 2013): (1) emotions are private; (2) emotions are negative; (3) emotions are feminine; (4) emotions are irrational; and (5) emotions are a sign of weakness.3 Separately, these beliefs have been examined and challenged by sociological theorists who have sought to understand how disciplines and cultural rules have taught us to think about and experience emotion (Boler 1999; Haraway 1991). The research with elite rowers and beliefs about emotion confirms the findings of previous research on emotion norms in sport (Askew and Ross 1988; Coker-Cranney et al. 2018; Curry 1993; Fry 2003; Hughes and Coakley 1991; Messner 1990, 1996; Smith 2008; Wacquant 1998; White et al. 1995; Young et al. 1994), such as ‘boys don’t cry’ and ‘girls don’t get angry’ (Askew and Ross 1988). Messner (1990) explained the relationship between organized sports and the social construction of masculinities, highlighting how organized sports can perpetuate gender hierarchies and exclude individuals who do not conform to traditional masculine norms. While a thorough discussion regarding stereotypes with respect to gender and expression of emotion is beyond the scope of this paper, these studies call attention to the complex interaction between emotion norms and sport. In addition, they underscore the importance of challenging emotion stereotypes and promoting an inclusive and supportive environment that allows athletes to express their emotions authentically.

Research has also examined the correlation between beliefs about emotion, emotion regulation, and health (Coker-Cranney et al. 2018; Curry 1993; Hughes and Coakley 1991; Jones et al. 2002; Lee Sinden 2010; Rimes and Chalder 2010; Smith 2008; Tran and Rimes 2017; Wacquant 1998; White et al. 1995; Winter 2019; Young et al. 1994). For example, Rimes and Chalder (2010) observed how certain beliefs about the unacceptability of experiencing or expressing emotions were present in individuals with a range of health problems, including chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, depression, eating disorders, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and borderline personality disorder. More recent research in sport has found a relationship between certain beliefs about emotion, dysregulation and unhealthy perfectionism, emotional suppression, and depression (Tran and Rimes 2017; Winter 2019). These findings support previous research in sport that has investigated the relationship between injuries, emotional norms, and the ways that athletes understand and express their emotions. According to this research, athletes have been found to believe that it is mentally ‘tough’ to ignore their injuries (Jones et al. 2002; Lee Sinden 2010). A further study explored perceptions of emotional climate among injured athletes and showed how athletes felt more respected when they displayed high pain tolerance and ignored their injuries for the sake of appearing ‘tough’. Unfortunately, this only exacerbated their injuries (Mankad et al. 2009). Other research investigating athletes with depressive symptoms has found that athletes may fake good (Gross et al. 2017). That is, in situations where they must demonstrate a certain persona (such as elite competition), they may engage in impressive management, which is similar to socially desirable responding, in order to be accepted and to show that they are able to cope in high-performance environments.

Emotions are often categorized as either negative or positive (Hanin 2000). This dichotomy has also played a role in normalizing certain beliefs about emotion in sport. Negative emotions are viewed as more unpleasant and generally occur when an event is perceived by a person to have moved them away from a goal. Examples of negative emotions include worry, sadness, anxiety, and/or anger. Positive emotions are viewed as more pleasant and are identified as moving a person towards a goal. Examples of positive emotions in sport include joy, compassion, and/or peace (Ekman 2005; Ekman and Davidson 1994; Hanin 2000). Classifying emotions in this way can exacerbate the stigma of emotion, coercing athletes to ignore or hide emotions they think are negative or bad. In addition, this dichotomy of emotions is misleading because it does not take into consideration the intention behind the emotion or an athlete’s heart. For instance, should we consider the emotion of joy to be positive if athletes experience joy after an opponent gets injured? Likewise, is anxiety negative when athletes are anxious due to concerns about overtraining? In this latter example, anxiety is positive when it leads athletes to take better care of their bodies (Lee Sinden 2014). Further, negative or unpleasant emotions are a genuine and healthy response during stressful or difficult times, such as a life transition, family separation, and/or a significant loss. Charles Spurgeon asserts it is even an act of faith and wisdom to be sad about sad things (Eswine 2014). Therefore, we add the concept of structure and direction (Wolters 2005), as it applies to emotion (Lee Sinden 2014)4 to further understand and explain emotion through a Christian perspective.

5. Structure and Direction of Emotion

From a Christian perspective, God created all things structurally good, which includes emotion. However, because of the fall, sin has corrupted us and our emotions, sometimes leading us into unhealthy and distorted directions. We read of this distorted direction in the Garden of Eden after Adam and Eve disobeyed God and felt shame. Instead of responding to their shame in a healthy way, such as taking responsibility for their actions, they hid from the truth in three ways: (1) from God (behind a tree), (2) from each other (by putting on fig leaves), and (3) from their self-awareness (by blaming each other) (ESV 2009, Genesis 1:3). In turn, athletes need to understand emotions are neither positive or negative in and of themselves. What is more important is the intention behind the emotion and the direction in which the emotion leads them (Lee Sinden 2014). For instance, when an injured athlete is worried about being replaced and trains despite injury, this would be an unhealthy direction of worry. A healthy direction would be to reflect on the underlying reasons for the worry and rest the injury. That said, emotion can also be non-conscious, producing somatic experiences like biological knee-jerk reactions, also referred to as sudden automatic reflex syndrome. Sometimes, these reactions are identified as socially unacceptable somatic responses (Hochschild 1979, p. 554; Devall-Martin 2017), such as when a tennis player throws a racket out of frustration. Nevertheless, all emotional reactions (or triggers) are opportunities for self-awareness and spiritual growth.

6. A Healthy Process of Emotion

In order to help athletes understand a healthy direction of emotion, we draw on the Gestalt theories of the process of emotion (Clarkson 1989). Gestalt psychology centres on the need to realize, explore, and experience emotions to understand oneself authentically. To fully appreciate and learn from emotional experiences, the emotion must go through a healthy direction or processing. We draw on Bolderston’s (2005) adaptation of Clarkson’s (1989) cycle of experience. In Step 1 a person begins to experience a sensation in the brain. If the emotion is not disrupted, the individual moves to Step 2, where the person is aware of the emotion and feels and appraises the emotion as pleasant or unpleasant. If the emotion is allowed to continue, the person will move into Step 3, where action tendencies begin to be displayed. Step 4 is called full contact, where a person experiences all of the associated bodily changes and emotional intensity. If the emotion progresses beyond full contact to Step 5, there will be a sense of satisfaction or release. If a person is given the opportunity to experience the entire process of their emotion, they will reach Step 6, which leads to awareness, acceptance, and behaviour change (Bolderston 2005; Lee Sinden 2014).

While expressing one’s true emotions and feelings through a healthy process is crucial for overall health and wellbeing (Patel and Patel 2019), it is common for the cycle of experience to be disrupted. The following outlines this process of disruption using a sport-related example. Step 1: Desensitization—the athlete ignores the experience. Step 2: Deflection—the athlete avoids, downplays, and/or dismisses feelings. Step 3: Introjection—the athlete resists action, perhaps having a belief system that inhibits the emotion (like emotions are weak). Step 4: Projection—this is where self-doubt, ‘what ifs’, or fears come into play, hindering the experience. Step 5: Retroflection—the feelings are turned back onto the athlete, such as anger towards self or self-harm. Also in Step 5, Egoism or Spectatoring—the athlete continually blocks spontaneity of experience, letting an internal (and often critical or judgmental) commentary about the emotion play in the mind, rather than experiencing it fully. Step 6: Confluence—the athlete over-identifies with an emotion, e.g., “I am an anxious person” (Bolderston 2005; Lee Sinden 2014).5

Disruption of the cycle of experience is considered an unhealthy process or direction of emotion and happens when a person forces control over the emotional experience at any step in the cycle of experience (Birrer et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2009). Educational sport psychology techniques, such as ‘negative thought stopping’, have been criticized for pushing away or suppressing emotion. While it is recognized that sometimes performance situations are not conducive for real-time reflection, clinical sport psychologists explain that forced control of emotions, particularly for the sake of sport performance, is a short-term fix, and it does not give the athlete the performance results they are looking for (Gardner and Moore 2007). For instance, forced control may have a reverse effect leading to explosive reactivity and maladaptive behavioural regulation (Birrer et al. 2012; Lee Sinden 2014). Further, reliance on the concealment of unpleasant emotions and feelings leads to repression (Patel and Patel 2019), emotional exhaustion (Chiang et al. 2021), and apathy, which can inhibit pleasant emotional experiences such as joy, excitement, and/or compassion (Brown 2018; Fahed and Steffens 2021). As Brown (2018, p. 85) argues, “we cannot selectively numb emotion. If we numb the dark, we numb the light. If we take the edge off pain and discomfort, we are, by default, taking the edge off joy, love, belonging, and the other emotions that give meaning to our lives”. In other words, depriving sensation or suppressing uncomfortable or unpleasant emotions will also negatively affect the experience of pleasant emotions.

The cycle of experience can be further understood using the model of behaviour change (McNamara 1998), a theory of transformative learning that demonstrates how change is not always a uniform process. Individuals shift through different stages several times, including relapsing into old behaviour, before achieving sustained change. This process is described as a spiral of human flourishing where individuals participate in ‘recursive reflective discourse’, learning from each relapse (Devall-Martin 2017; McNamara 1998). In addition, the cycle of experience reflects the Mindful Acceptance Commitment (MAC) theory, which promotes a non-judgmental approach to emotions (Gardner and Moore 2007). MAC, originally taken from Acceptance and Commitment Theory, states that in order for individuals to experience emotions in a healthy manner, individuals must experience the entire process of emotion (Hayes and Strosahl 2004). Hayes and Strosahl (2004) explain that reasons for reactions are acknowledged only when there is an awareness of the emotion; if there is a block to the emotional experience, the awareness and subsequent change rarely takes place (see also Hayes et al. 2004). Similarly, other researchers in counselling theory consider a healthy process of emotion as befriending one’s emotions (Schwartz 1995)6. For example, instead of trying to control or disrupt the emotional experience, a person considers why the emotion is present and then determines how to engage, respond, and grow in a healthy direction. For instance, a healthy direction in response to worry for Christian athletes could be to “… cast all their worries and cares on Him” (New Living Translation [NLT] 2015, 1 Pet. 5:7).

In scripture, self-control is one of the ‘Fruits of the Spirit’: the Spirit of God working in a person’s heart (New International Version [NIV] (NIV 2011, Gal. 5:22–23)). This means that self-control grows from awareness, acceptance, and change as a part of increased knowledge and spiritual growth; the process of growing in the image of Christ (Hielema 2010; Roberts 1982; NIV 2011, 2 Pet. 1:5–7). Thus, we confirm research that highlights the importance of including a spiritual component in the development of an athlete (Egli and Hoven 2020; Hemmings et al. 2019), and we add spiritual formation to the Integrated Model of Athletic Performance (IMAP).

7. Spiritual Formation

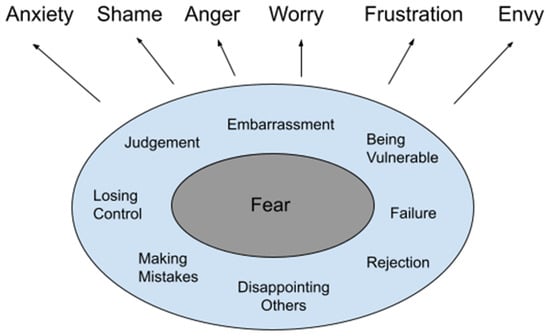

God created humankind as emotional beings (Middleton 2005). Therefore, our emotions are part of our spiritual nature and who we are in God’s image. While it can be difficult to face the truth about our emotions, ignoring, numbing, or suppressing them often leaves us more susceptible to experiencing spiritual stagnation or degradation (Chambers [1924] 1993). Understanding our emotions deepens our awareness of ourselves and our identity in Christ, which, in turn, draws us into more intimate relationships with God and others (Edwards [1746] 2013; Roberts 2007). As previously stated, spiritual formation is the “process of being conformed into the image of Jesus Christ” (Mulholland and Barton 2016, p. 7), a transformation through the Holy Spirit “by the renewing of your mind” (NIV 2011, Romans 12:2). While examining all of the aspects of emotions through the lens of spiritual formation is beyond the scope of the present discussion,7 we provide additional insight into how our emotions reveal underlying distorted fears. The following image can be used to help athletes visualize the relationship between their emotions and underlying fears (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Illustration of emotions and possible underlying fears. Note. Adapted from Lee Sinden (2022).

8. Understanding Fear

Many of the unpleasant emotions athletes feel or demonstrate are caused by underlying fears (Steimer 2002). Sport psychologists have studied the role of fear in stifling athletic performance, particularly in the case of the perfectionist athlete. Some examples include: fear of failure, fear of judgment, fear of embarrassment, fear of making mistakes, fear of losing respect from others, fear of disappointing others, fear of having an uncertain future, and/or fear of not reaching expectations (Goldberg 1991; Sagar and Stoeber 2009). We recommend using Figure 1 as a template with athletes. The athlete can write down (or circle) examples of unpleasant emotions that they experience. Once they have identified these emotions, they can be instructed to write down (or circle) the specific fears that they have. We also suggest providing reflection questions. By way of example: (a) In what ways might fear of injury be at the root of your anxiety or worry? Or, (b) In what ways might fear of disappointing others be at the root of your shame or embarrassment? Or, (c) In what ways might the fear of failure be at the root of your frustration, impatience, or envy? After some reflection, the analysis can go deeper still, considering why the athlete might have these fears. When unpacking fear, it is vital to address the root (Welch 2020). If a person does not understand the fear at its source, it will continue to re-surface throughout a person’s life (Adams 1973; Jones 1999). However, this is often a slow and painful process of deep contemplation of one’s motivations and thoughts, referred to as heart theology, which is a basic understanding of how sanctification works (Welch 2016). Furthermore, being able to identify fears requires strong meta-cognitive skills and self-awareness (Leaf et al. 1998).

From a Biblical perspective, God instructs us, “do not fear, for I am with you” (NIV 2011, Isaiah 41:10). At the same time, He teaches, “the fear of God is the beginning of wisdom” (NIV 2011, Prov. 9:10). This brings us back to structure and direction. We understand fear as structurally good, such as fear in the face of danger and/or the reverent fear of God, which leads to drawing closer to and growth in Him. However, because of sin, fear has been distorted or corrupted, leading to an unhealthy or distorted direction of fear, such as fear related to people, places, or things (Augustine [1871] 2017; Lee Sinden 2014; Wolters 2005). While we acknowledge that a deep analysis of the many reasons for an athlete’s distorted fears is important (e.g., such as harbouring resentment after being treated unjustly), this is beyond the scope of the present discussion—and perhaps beyond the comfort or expertise of those working with athletes.8 Further, while we agree with the importance of understanding the sociological intricacies at play within such scenarios (Jones et al. 2020), we believe that a deep and comprehensive understanding of the spiritual root of emotions, and subsequent behaviours, is essential for the spiritual formation and holistic development of athletes. The following section provides practical suggestions for teaching about the spiritual root or real culprit of one’s distorted emotions and fears, and subsequent destructive behaviours, namely inordinate affections (Augustine [1871] 2017; Powlison 1995; Welch 1997, 2016, 2020).

9. Inordinate Affections

An inordinate affection has been described as an out of balance, excessive, or obsessive affection we might have for a person, place, or thing (Lewis 1960). Inordinate affections develop when the love for a person, place, or thing has become an idol, above our love for God. The word inordinate is used synonymously with ‘evil desire’ in the King James Version [KJV] and NIV of the Bible in Colossians 3:5. Augustine ([1871] 2017) described an inordinate affection as a ‘disordered love’. It is not love in itself, for love, like all things in God’s good creation is a natural affection. Rather, inordinate love is not loving rightly (Augustine [1871] 2017; Lewis 1964). In his understanding of scripture, Augustine considered rightly ordered love as virtue, and inordinate love as vice (Naugle 1993).

… boasting [is not] the fault of human praise, but of the soul that is inordinately fond of the applause of men… Pride too, is not the fault of him who delegates power, for of power itself, but of the soul that is inordinately enamoured of its own power and despises the more just dominion of a higher authority.(Augustine [1871] 2017, pp. 330–31)

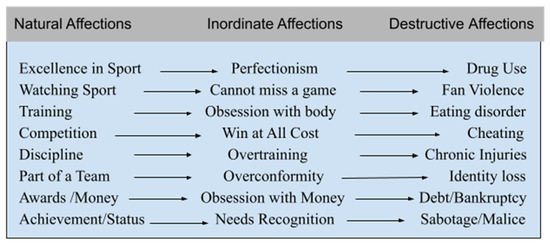

Structurally our natural affections are part of God’s good creation; however, because of the fall our affections have been distorted and lead us into inordinate and sometimes destructive directions. For example, sport in itself is not sinful or bad, nor are the reasons why we may participate in sport. God has given us sport to enjoy. Sport, or the aspects of sport that we love, become inordinate when we make them more important than God. Figure 2 provides an illustration of examples of how natural affections in sport can become inordinate affections and then grow into destructive affections. Excellence, for instance, is a natural affection when pursuing high performance in sport. It is not evil in and of itself but, as outlined in Figure 2, excellence can become inordinate and lead to perfectionism, which can progress into destructive affections, like taking performance enhancing drugs to achieve excellence, such as in the case of Lance Armstrong (Flett and Hewitt 2014). We recommend using Figure 2 (blank or as is) in education and mentoring sessions with athletes.It is helpful to ask athletes to fill out (or circle) the aspects of sport that they enjoy (natural affections), and then guide a reflection to understand the progression from inordinate to destructive affections. Reflecting on the contents of the table can be enlightening for athletes as they realize the connections between each of the affections, particularly if they have been struggling with a destructive affection and are unaware of how it progressed to that point. Some suggestions for further reflection include questions such as (a) How does training become an obsession and then develop into an eating disorder? Or (b) How does being part of a team lead to over conformity and the loss of one’s authentic identity? Here would also be an opportunity to discuss the role of fears and inordinate affections in the development of a performance-based identity.

Figure 2.

Illustration of progression of natural, inordinate, and destructive affections in sport. Note. Adapted from Lee Sinden (2022).

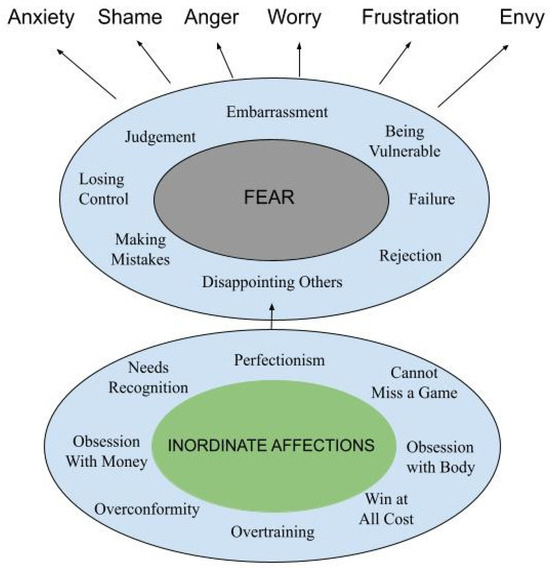

Moving forward, Figure 3 provides an illustration of the relationship between emotions, fears, and inordinate affections. For athletes to make connections they can circle or fill out the Figure. Guided questions can help facilitate this reflection process as well, such as (a) How does a win-at-all-costs philosophy lead to a fear of failure and then worry? and (b) How does over conformity lead to a fear of disappointing others, and then anger?

Figure 3.

Illustration of relationship between emotions, fears and inordinate affections. Note. Adapted from Lee Sinden (2022).

10. Beyond Education: The Work of the Spirit

According to Begg (2000), few people would argue that education is not important, but there is no intellectual road that takes us to heavenly wisdom. Educating athletes about sinful fears and inordinate affections and helping them reflect on their habits and actions within sport may lead them to realize what they value or treasure (Egli and Hoven 2020). “For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also” (Matthew 6:21). However, as Christians, we believe that it is through the work of the Holy Spirit (the Spirit of Christ) Who opens eyes to one’s need for Christ as their merciful Saviour from sins of both heart and behaviour, and then turn to God in humble repentance to receive the fullness of forgiveness and grace. When a person accurately comprehends the interweaving of responsible behaviour, deceptive inner motives, and powerful external forces, then the riches of Christ become immediately relevant: “What was once head knowledge and dry doctrine becomes filled with wisdom, relevancy, appeal, hope, delight, and life” (Powlison 1995, pp. 47–48).

In the Old Testament, King David models heartfelt repentance and His need for Christ in Psalm 51 when he cries out:

Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love. … Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity… Against you, you only, have I sinned. … Behold, you delight in truth in the inward being, and you teach me wisdom in the secret heart.(ESV 2009, Psalm 51, 1–6)

We learn in Psalm 51 that God delights in truth in the inward parts. In humbly accepting the truth in our hearts, we grow in wisdom. Out of His love and protection God instructs us, “you shall have no other gods before me” (ESV 2009, Ex. 20:3), and “mortify inordinate affections” (KJV [1769] 2017, Col. 3:5); put them to death through repentance at the cross of Christ in humble prayer. This process brings the idol back to what is natural, to its rightful order. Specific to sport, God becomes big (our first love), and all of the natural affections related to sport become small, which is the way God intended it at creation (Powlison 1995; Welch 1997). In this place, athletes will experience the sufficiency of God’s grace in their weakness (ESV 2009, 2 Cor. 12:9), and the joy of self-denial (Calvin [1559] 2004).

John Calvin’s ([1559] 2004, p. 96) life-giving words remind us that self-denial is an essential part of any genuine life with God:

Let us therefore not seek our own but that which pleases the Lord, and is helpful to the promotion of His glory. There is a great advantage in almost forgetting ourselves and in surely neglecting all selfish aspects; for then only can we try faithfully to devote our attention to God and his commandments.

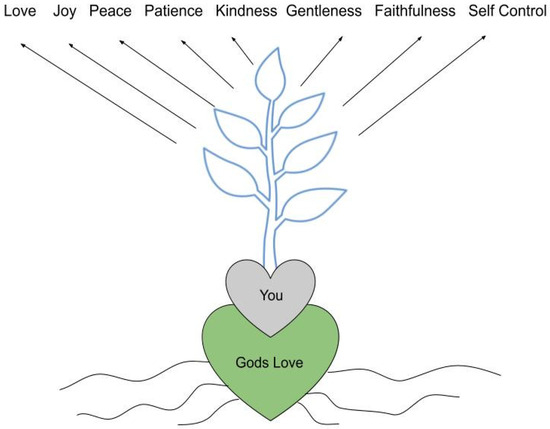

However, the self-denial that Calvin and the Scriptures describe has nothing to do with harming the body like training despite injuries, nor with earning merit through powers of self-control, such as in forced control over emotion. Foster and Smith (1993) illustrate with an image of an athlete entering a training program, appropriate for the development of mind, body, and spirit, to show how self-denial, a regular part of the regimen of the athlete, is also a regular part of every Christian’s training regimen, as we “press on toward the goal for the prize of the heavenly call of God in Christ Jesus” (NIV 2011, Phil. 3:14). God teaches us to “walk by the Spirit, and you will not gratify the desires of the flesh. For the flesh desires what is contrary to the Spirit, and the Spirit what is contrary to the flesh” (NIV 2011, Gal. 5:16–18). When athletes surrender their hearts and make God their first love, they are rooted in His love: where they walk in His Spirit, find their identity in Him, and grow in the Fruit of the Spirit (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Vertical identity: being rooted in God’s love and growing in the fruit of the spirit. Note. Adapted from Lee Sinden (2022).

Identity in Christ and transformation through His Spirit is key to spiritual growth. When athletes are rooted in God’s love, their identity is not in what they accomplish, or what they own, or what people say about them. Their identity is vertical as beloved sons and daughters of the heavenly Father (Nouwen 1992), and their worth is in the grace of God who loves despite failures and imperfections (Winter 2019). “See what great love the Father has lavished on us, that we should be called children of God! And that is what we are” (NIV 2011, 1 John 3:1). In the Beatitudes, the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus provides a description of how to experience the fullness of the Father’s love and grow as a child of God, and He calls each part of the process ‘blessed’ (NIV 2011, Matthew 5:1–12). He teaches us the first step is to go to Him ‘poor in spirit’, humbly knowing our sin and in need of a saviour; “Blessed are those who are poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven”. Jesus proceeds to teach the remaining seven steps in this progression and shows us that true spiritual formation is a blessing; only to be found in Him (NIV 2011, Matthew 5:3–12). So then, let us use the opportunity that God has given us, in and through the gift of sport, to shepherd athletes in the way of the heart (Nouwen 2010) so they turn to Christ and live a beatitude life where they will find comfort, learn to trust God’s promises, and take refuge in a Father who loves them.

11. Conclusions

The aim of this paper has been to address the role of unhealthy beliefs about emotion among athletes and the potential impact on their health and wellbeing. We have provided a summary of the normalization of emotion, highlighting how athletes are persuaded through sociological and normalizing methods to adopt unhealthy beliefs about emotion, and how these beliefs may lead to destructive behaviours. In addition, we have recommended in-depth emotion education for athletes to break down unhealthy emotion norms and improve their overall health and wellbeing. Specifically, we have explained how a healthy process of emotion leads to an awareness of one’s authentic identity and spiritual formation. In this sense, our aim is to disrupt some of the “long-standing attitudes, assumptions and behaviors in sport around performance-based identity” and the negative impact this has on athletes (Jones et al. 2020, p. 10). Consequently, we offer an innovative educational approach that can be used practically by sport chaplains, coaches, and/or sport advocates in relation to the spiritual–emotional development of athletes. Furthermore, we have suggested an educational and mentoring approach for athletes’ emotional and spiritual development to help them understand what their emotions may be revealing at the root, such as underlying fears and inordinate affections. Walking with athletes along their sporting journey in this meaningful way has the potential to help diminish unhealthy beliefs about emotion, open their hearts to experiencing their emotions fully, and lead them to a deeper understanding of their authentic selves in Christ. Our hope is that together, we may coach, teach, and mentor in such a way that athletes are strengthened with power through the Holy Spirit in their inner being, so that Christ may dwell in their hearts through faith, and that they may “grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, … [that they may] know this love that surpasses knowledge, [and] that [they] may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God” (NIV 2011, Eph. 3:17–19).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.S.; software, J.L.S. and L.D.-M.; validation, J.L.S.; formal analysis, J.L.S.; investigation, J.L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.S.; writing—review and editing J.L.S. and L.D.-M.; visualization, J.L.S.; supervision, J.L.S.; project administration, J.L.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Notes

| 1 | For a more thorough theoretical discussion of how Foucault (1977) is used with respect to the ‘normalization of emotion’, as well as a conceptual explanation of the ‘beliefs about emotion’ (technologies of emotion), within the research in elite female rowers, see Lee Sinden (2010, 2013). |

| 2 | For more information about maladaptive schemas and Young’s Schema Questionnaire see Young (1994, 1998). |

| 3 | For a more in-depth discussion of the ‘beliefs about emotion’, see Lee Sinden (2010, 2013). For the purposes of self-assessment and reflection with athletes, we suggest the Beliefs about Emotions scale as a way to initiate awareness and discussion with athletes about their biases and perspectives about emotion (see Rimes and Chalder 2010). |

| 4 | For a more detailed exploration of the concept of structure and direction see Wolters (2005). With respect to structure and direction as it applies to emotion, see Lee Sinden (2014). |

| 5 | For a further examination of each of the components of emotion and the cycle of experience, including disruptions, see Clarkson ([1989] 2014), Gray (2004); Hostrup (2010), Mann (2010), Lee Sinden (2014), Perls et al. ([1951] 1969), and Zinker (1977). |

| 6 | For more information about ‘befriending’ your emotions see Internal Family Systems Theory (IFS) (Schwartz 1995). |

| 7 | For more on spiritual formation and Christianity see Hielema (2010); Mulholland and Barton (2016); Nouwen (2010); Thompson (2014), and Willard (1988). |

| 8 | In circumstances where a safe and supportive exploration of distorted fears is needed, we recommend Internal Family Systems (IFS). Originally designed by Schwartz (1995), Internal Family Systems (IFS) focuses on the normalcy and ‘multiplicity’ in the human mind. Parts of the system take on beliefs, and these beliefs become burdens, which dominate and polarize thinking. The goal of therapy is to unburden parts of extreme thinking and beliefs, so they function non-reactively and in harmony with other parts. IFS recognizes the human ability to think about one’s thinking: to observe, nurture, lead, and establish relationships with various parts of the mind, particularly emotions, without labelling them as positive or negative. (Devall-Martin 2017) Rather, there is an opportunity to acknowledge, engage with, and understand human multiplicity. For Christians, IFS presents the opportunity to consider Jesus’ presence with all parts and burdens of the mind, which is richly explored by Cook and Miller (2018). |

References

- Adams, Jay. 1973. The Christian Counselor’s Manual: He Practice of Nouthetic Counseling. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Åkesdotter, Cecilia, Göran Kenttä, Sandra Eloranta, and Johan Franck. 2020. The prevalence of mental health problems in elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 23: 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askew, Sue, and Carol Ross. 1988. Boys Don’t Cry: Boys and Sexism in Education. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine. 2017. The City of God: Books I–VII. Translated by Marcus Dods. Boston: Digireads.com Publishing. First published 1871. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Joe, Parissa Safai, and Jessica Fraser-Thomas, eds. 2014. Health and Elite Sport: Is High Performance Sport a Healthy Pursuit? 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Begg, Alistair. 2000. Historical Survey of Preaching Part 2. Truth For Life Ministries. Available online: https://www.truthforlife.org (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Biggin, Isobelle J. R., Jan H. Burns, and Mark Uphill. 2017. An investigation of athletes’ and coaches’ perceptions of mental ill-health in elite athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 11: 126–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrer, Daniel, Philipp Röthlin, and Gareth Morgan. 2012. Mindfulness to enhance athletic performance: Theoretical considerations and possible impact mechanisms. Mindfulness 3: 235–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolderston, Helen. 2005. Is Emotional Processing all Negative: A Gestalt Perspective. Available online: https://emotionalprocessingtherapy.org/is-emotional-processing-all-negative/ (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Boler, Megan. 1999. Feeling Power: Emotions and Education. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bounds, Elizabeth. 2022. Virtue Development in Sport. Paper presented at Third Global Congress on Sport and Christianity (3GCSC), Ridley Hall, Cambridge, UK, August 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Brené. 2018. Dare to Lead: Brave Work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts. Chicago: Turabian. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, John. 2004. Golden Booklet of the True Christian Life. Translated by Henry J. Van Andel. Grand Rapids: Baker Books. First published 1559. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Oswald. 1993. My Utmost for His Highest. Grand Rapids: Discovery House Publishers. First published 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Jack Ting-Ju, Xiao-Ping Chen, Haiyang Liu, Satoshi Akutsu, and Zheng Wang. 2021. We have emotions but can’t show them! Authoritarian leadership, emotion suppression climate, and team performance. Human Relations 74: 1082–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, Petruska. 1989. Gestalt Counseling in Action. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, Petruska. 2014. Gestalt Counselling in Action, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. First published 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Clemens, Joseph. 2008. The sports chaplain and the work of youth formation. In Pontificium Consilium pro Laicis, Sport: An Educational and Pastoral Challenge. Edited by Città del Vaticano and Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Vatican City: Vatican, pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Coker-Cranney, Ashley, Jack C. Watson, Malayna Bernstein, Dana K. Voelker, and Jay Coakley. 2018. How far is too far? Understanding identity and over conformity in collegiate wrestlers. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 10: 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Alison, and Kimberly Miller. 2018. Boundaries for the Soul: How to Turn Your Overwhelming thoughts and Feelings into Allies. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin, Con. 2012. Toulouse Shooting: The Rise of the ‘Just Do It’ Terrorists. The Telegraph. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk (accessed on 20 January 2013).

- Crocker, Peter R., Catherine Sabiston, and Megha McDonough. 2021. Sport and Exercise Psychology: A Canadian Perspective, 4th ed. Burlington: Pearson Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, Timothy. 1993. A little pain never hurt anybody: Athletic career socialization and the normalization of sport injury. Symbolic Interaction 16: 273–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski, Kazimierz. 1964. Positive Disintegration. Boston: Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, Antonio R. 1994. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Grosset/Putnam. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, Harry. 2001. Vygotsky and Pedagogy. New York: Routledge/Falmer. [Google Scholar]

- Devall-Martin, Lisa. 2017. School Administrators’ Insight and Self-Reflection: An Exploration of the Influence of Expressive Writing and the Lumina Spark Inventory on Self-Awareness. Ph.D. dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Judy. 1994. Particular culture. In The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. Edited by Paul Ed Ekman and Richard J. Davidson. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 352–55. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Jonathan. 2013. The Works of Jonathan Edwards: Volume II: Religious Affections. Edited by John E. Smith. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. First published 1746. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Jonathan. 2014. Charity and Its Fruit: Christian Love as Manifested in the Heart and Life. Lawton: Trumpet Press. First published 1749. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Jonathan. 2003. The Nature of True Virtue. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers. First published 1791. [Google Scholar]

- Egli, Trevor J., and Matt Hoven. 2020. Integrating faith: Sport psychology for Christian athletes and coaches. In Sport and Christianity: Practices for the Twenty-First Century. Edited by Matt Hovern. London: T &T Clark, pp. 109–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, Paul. 2005. Basic emotions. In Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. Edited by Michael J. Power and Tim Dalgleish. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, Paul Ed, and Richard J. Davidson, eds. 1994. The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 352–55. [Google Scholar]

- ESV. 2009. The Holy Bible: The English Standard Version Bible: Containing the Old and New Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eswine, Zack. 2014. Spurgeon’s Sorrows: Realistic Hope for those who Suffer from Depression. Ross-shire: Christian Focus Publications, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Fahed, Mario, and David C. Steffens. 2021. Apathy: Neurobiology, Assessment and Treatment. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 19: 181–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairs, Marcus. 2005. “Nike’s ‘Just do it’ slogan is based on a murderer’s last words, says Dan Wieden”. Dezeen Magazine. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2015/03/14/nike-just-do-it-slogan (accessed on 5 January 2007).

- Flett, Gordon L., and Paul L. Hewitt. 2014. “The perils of perfectionism in sports” revisited: Toward a broader understanding of the pressure to be perfect and its impact on athletes and dancers. International Journal of Sport Psychology 45: 395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Richard J., and James Bryan Smith. 1993. Devotional Classics: Selected Readings. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, Nico. 1986. The Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, Jeffrey P. 2003. On playing with emotion. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 30: 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Frank L., and Zella E. Moore. 2007. The Psychology of Enhancing Human Performance: The Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment (MAC) Approach. New York: Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Alan D. 1991. Counseling the High School Student-Athlete. The School Counselor 38: 332–40. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, Alicia A. 2000. Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way of conceptualizing emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health and Psychology 5: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Jeremy R. 2004. Integration of emotion and cognitive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science 13: 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, Mike B., Andrew T. Wolanin, Rachel A. Pess, and Eugene S. Hong. 2017. Socially desirable responding by student-athletes in the context of depressive symptom evaluation. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 11: 148–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanin, Yuri L. 2000. Successful and poor performance and emotions. In Emotions in Sport. Champaign: Human Kinetics, pp. 157–87. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Steven C., and Kirk D. Strosahl, eds. 2004. A Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Steven C., Victoria M. Follette, and Marsha Linehan. 2004. Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the Cognitive-Behavioural Tradition. New York: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings, Brian, Nick J. Watson, and Andrew Parker, eds. 2019. Sport, Psychology and Christianity: Welfare, Performance and Consultancy, 1st ed.London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hielema, Sid. 2010. Wide and Long and High and Deep: Biblical Foundations of Faith Formation. Grand Rapids: Faith Alive Christian Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1979. Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology 85: 551–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, Neil. 2009. Towards a Theology of the Ministry of Presence in Chaplaincy. Journal of Christian Education 52: 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostrup, Hanne. 2010. Gestalt Therapy: An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Gestalt Therapy. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, David P. 2004. Sport, Professionalism and Pain. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Robert, and Jay Coakley. 1991. Positive deviance among athletes: The implications of over conformity to the sport ethic. Sociology of Sport Journal 8: 307–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izard, Carroll. 2009. Emotion Theory and Research: Highlights, Unanswered Questions, and Emerging Issues. Annual Review of Psychology 60: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jekauc, Darko, Julian Fritsch, and Alexander T. Latinjak. 2021. Toward a Theory of Emotions in Competitive Sports. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 790423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Peter. 2011. The Third Factor. Toronto: Dundurn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Graham, Sheldon Hanton, and Declan Connaughton. 2002. What is this thing called mental toughness? An investigation of elite sport performers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 14: 205–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Luke, Andrew Parker, and Graham Daniels. 2020. Sports chaplaincy, theology and social theory disrupting performance-based identity in elite sporting contexts. Religions 11: 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Robert D. 1999. Getting to the Heart of Worry. Journal of Biblical Counseling 17: 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- KJV. 2017. The Holy Bible: King James Version. Available online: http://www.biblegateway.com/versions/King-James-Version-KJV-Bible/#booklist (accessed on 15 December 2022). First published 1769.

- Leaf, Caroline, Brenda Louw, and Isabel Uys. 1998. An alternative non-traditional approach to learning: The metacognitive-mapping approach. The South African Journal of Communication Disorders 45: 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeDoux, Joseph E. 1994. Emotional processing, but not emotions, can occur unconsciously. In The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. Edited by Paul Ed Ekman and Richard J. Davidson. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 352–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Sinden, Jane. 2010. The normalization of emotion and the disregard of health problems in elite amateur sport. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 4: 241–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Sinden, Jane. 2013. The sociology of emotion in elite sport: Examining the role of normalization and technologies. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 48: 613–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Sinden, Jane. 2014. The structure and direction of emotion in elite sport: Deconstructing unhealthy paradigms and distorted norms for the body. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 1112–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Sinden, Jane. 2022. The Normalization of Emotion among Christian University Athletes: Practical Suggestions for Emotional and Spiritual Development. Paper presented at Third Global Congress on Sport and Christianity (3GCSC), Ridley Hall, Cambridge, UK, August 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Sinden, Jane. 2023. The Normalization of Emotion and Disregard of Health Problems among Christians University Athletes (Unpublished Research). Ancaster: School of Kinesiology, Redeemer University. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Robert I. 1984. The emotions in comparative perspective. In Approaches to Emotion. Edited by Klaus R. Scherer and Paul Ekman. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Clive Staples. 1960. The Four Loves. London: Geoffrey Bles. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Clive Staples. 1964. Letters to Malcohm: Chiefly on Prayer. London: Geoffrey Bles. [Google Scholar]

- Macchia, Stephen. 2022. The Discerning Life: An Invitation to Notice God in Everything. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Mankad, Aditi, Sandy Gordon, and Karen Wallman. 2009. Perceptions of Emotional Climate among Injured Athletes. Journal of Clinical Sports Psychology 3: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, Dave. 2010. Gestalt Therapy 100 Key Points & Techniques. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marinese, Anthony. 2016. Beyond praying for players: An exploration of the responsibilities and practices of sports chaplains. In Sports Chaplaincy: Trends Issues and Debates. Edited by Andrew Parker, Nick J. Watson and J. White. London: Routledge, pp. 135–45. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, Eddie. 1998. The Theory and Practice of Eliciting Pupil Motivation: Motivational Interviewing: A Form of Teacher’s Manual and Guide for Students, Parents, Psychologists, Health Visitors, and Counselors. Ainsdale Merseyside: Positive behaviour Management. [Google Scholar]

- Messner, Michael. 1990. Boyhood, organized sports, and the construction of masculinities. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 18: 416–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, Michael. 1996. The relationship of friendship networks, sport experiences, and gender to express pain thresholds. Sociology of Sport Journal 13: 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, J. Richard. 2005. The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1. Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Moseid, C. H., G. Myklebust, M. W. Fagerland, B. Clarsen, and R. Bahr. 2018. The prevalence and severity of health problems in youth elite sports: A 6-month prospective cohort study of 320 athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 28: 1412–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, Michael J., Frierson Desiree’J, Yihan Cheng, and Mark W. Aoyagi. 2015. Spirituality & sport: Consulting the Christian athlete. The Sport Psychologist 29: 371–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland, M. Robert, and Ruth Haley Barton. 2016. Invitation to a Journey: A Road Map to Spiritual Formation. Westmont: Intervarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naugle, David K. 1993. St. Augustine’s Concept of Disordered Love and its Contemporary Application. Southwest Commission on Religious Studies, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Group. Available online: https://www3.dbu.edu/naugle/pdf/disordered_love.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- New Living Translation [NLT]. 2015. The Holy Bible: The New Living Translation. Carol Stream: Tyndale House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- NIV. 2011. The Holy Bible: The New International Version. Palmer Lake: Biblica, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Nouwen, Henry. 1992. Being the Beloved. Crystal Cathedral. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v8U4V4aaNWk (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Nouwen, Henry. 2010. Spiritual Formation: Following the Movement of the Spirit. New York: Harper Collins Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Oatley, Keith, and Jennifer M. Jenkins. 1992. Human emotions: Function and dysfunction. Annual Review of Psychology 43: 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oatley, Keith, and Jennifer M. Jenkins. 1996. Understanding Emotions. Cambridge: Blackwell Science. [Google Scholar]

- Paget, Naomi K., and Janet R. McCormack. 2006. The Work of the Chaplain. New York: Valley Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Parker J. 2009. A Hidden Wholeness: The Journey toward an Undivided Life—Welcoming the Soul and Weaving Community in a Wounded World. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Andrew, and Andrew Manley. 2016. Identity. In Studying Football. Edited by Ellis E. Cashmore and Kevin Dixon. London: Routledge, pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, Jainish, and Prittesh Patel. 2019. Consequences of repression of emotion: Physical health, mental health and general wellbeing. International Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 1: 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perls, Fritz, Goodman Hefferline, and Paul Goodman. 1969. Gestalt Therapy. In Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality, 5th ed. New York: Julian Press, Inc. First published 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Powlison, David. 1995. Idols of the Heart and Vanity Fair. Journal of Biblical Counseling 13: 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rimes, Katharine A., and Trudie Chalder. 2010. The Beliefs about Emotions Scale: Validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 68: 285–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Robert. 1982. Spirituality and Human Emotions. Michigan: William B Eerdmans Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Robert. 2007. Human Emotion and Christian Spirituality. Michigan: William B Eerdmans Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rosaldo, Robert. 1989. Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sabato, Todd M., Tanis J. Walch, and Dennis J. Caine. 2016. The elite young athlete: Strategies to ensure physical and emotional health. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine 7: 99–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Safai, Parissa, Jessica Fraser-Thomas, and Joseph Baker. 2014. Sport and Health of the High performance athlete. In Health and Elite Sport: Is High Performance Sport a Healthy Pursuit. Edited by Joe Baker, Parissa Safai and Jessica Fraser-Thomas. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sagar, Sam S., and Joachim Stoeber. 2009. Perfectionism, fear of failure, and affective responses to success and failure: The central role of fear of experiencing shame and embarrassment. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 31: 602–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitker, Sarah A., Benjamin J. Houltberg, Juliette L. Ratchford, and Kenneth T. Wang. 2020b. Dual pathways from religiousness to the virtue of patience versus anxiety among elite athletes. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitker, Sarah A., Madison Kawakami Gilbertson, Benjamin Houltberg, Sam A. Hardy, and Nathaniel Fernandez. 2020a. Transcendent motivations and virtue development in adolescent marathon runners. Journal of Personality 88: 237–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R. 1995. Internal Family Systems Therapy. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. Tyson. 2008. Pain in the act: The meanings of pain among professional wrestlers. Qualitative Sociology 31: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainback, Robert D., James C. Moncier, II, and Robert E. Taylor. 2007. Sport psychology: A clinician’s perspective. In Handbook of sport psychology. Edited by Gershon Tenenbaum and Robert C. Eklund. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 310–31. [Google Scholar]

- Steimer, Thierry. 2002. The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviours. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 4: 231–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, Christopher L. 1991. The Christian-Athlete: An Interactionist-Developmental Analysis. Sociology of Sport Journal 8: 362–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, Jon, and Brendan King. 2022. Using informal conversations in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Marjorie. 2014. Soul Feast: An Invitation to the Christian Life. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Threlfall-Holmes, Miranda, and Mark Newitt. 2011. Being a Chaplain. London: SPCK. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Lisa, and Katharine A. Rimes. 2017. Unhealthy perfectionism, negative beliefs about emotions, emotional suppression, and depression in students: A mediational analysis. Personality and Individual Differences 110: 144–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, Loïc. 1998. A fleshpeddler at work: Power, pain, and profit in the prizefighting economy. Theory and Society 27: 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, Carol, Carol Tavris, Debra Saucier, and Lorin Elias. 2007. Psychology, 2nd ed. Toronto: Pearson Education Canada Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, Steven N., and Harold Cottom. 2016. Reviving the shepherd within in: Pastoral theology and its relevance to sports chaplaincy in the twenty-first century. In Sports Chaplaincy: Trends, Issues and Debates. Edited by Andrew Parker, Nick J. Watson and John B. White. London: Routledge, pp. 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, Robert S., and Daniel Gould. 2018. Foundations of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 7th ed. Champaign: Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Edward T. 1997. When People are Big and God is Small: Overcoming Peer Pressure, Codependency, and the Fear of Man. Phillipsburg: P & R Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Edward T. 2016. Christian Counseling and Education Foundation. Available online: https://www.ccef.org/video/ed-welch-fear/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Welch, Edward T. 2020. Bible Basics for the Fearful and Anxious. Journal of Biblical Counseling 34: 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- White, P. G., K. Young, and W. G. McTeer. 1995. Sport, masculinity and the injured body. In Men’s Health and Illness: Gender, Power, and the Body. Edited by D. Sabo and F. Gordon. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Willard, Dallas. 1988. The Spirit of the Disciplines: Understanding How God Changes Lives. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Lawrence E., John A. Bargh, Christopher C. Nocera, and Jeremy R. Gray. 2009. The unconscious regulation of emotion: Nonconscious reappraisal goals modulate emotional reactivity. Emotion 9: 847–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, Richard. 2019. The pursuit of excellence and the perils of perfectionism: Psychological and theological reflections. In Sport, Psychology and Christianity, 1st ed. London: Routledge, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1958. Philosophical Investigations. New York: MacMillian. [Google Scholar]

- Wolters, Albert. 2005. Creation Regained: Biblical Basics for a Reformational Worldview. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Jeffrey E. 1994. Cognitive Therapy for Personality Disorders: A Schema-Focused Approach, 2nd ed. Sarasota: Professional Resource Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Jeffrey E. 1998. The Young Schema Questionnaire: Short form. APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Jeffrey E., Janet S. Klosko, and Marjorie E. Weishaar. 2003. Schema Therapy. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Kevin, Philip White, and William McTeer. 1994. Body talk: Male athletes reflect on sport, injury and pain. Sociology of Sport Journal 11: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinker, Joseph. 1977. Creative Process in Gestalt Therapy. New York: Vintage books. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).