2. Defining “Wisdom Homiletics”

It is argued here that preaching through the lens of wisdom serves best to communicate a homiletical theology that is steeped in hope. As defined by David Schnasa Jacobsen, “preaching is not about consuming theology, but a place where theology is ‘done,’ or produced” (

Jacobsen 2015, p. 3). And as I have elaborated elsewhere, “the theological operation of preaching is recast from a cognitive dissemination of propositions to a constructive dialogue of kerygmatic proclamation. Rather than continue the proliferation of compartmentalized theological conversations lodged in disjointed and disconnected loci, preaching rooted in homiletic theology seeks to bring all the conversations to the same table in an interdisciplinary construction of formative faith and practice” (

O’Lynn 2022, pp. 220–21). In the locus of homiletical theology, the focus of the sermon shifts from the study and pulpit to the “sanctuary” of the congregation—wherever that may be located—as theology is constructed in conversation between preacher and active participant (or, disciple).

1 In its very essence, homiletical theology envisions preaching—in fact, Christian discipleship itself—as an ongoing conversation “about all these things that had happened” that leads believers to the exultant affirmation that “the Lord has risen indeed” (Luke 24:14, 34)!

2 Preaching in the vein of hope engages its task purposefully with the intent of sparking the eschatological imagination that advocates, demonstrates, and anticipates the culmination of God’s missional work throughout history. It is not beholden to visions of a “sweet by and by” but to visions of active engagement consecrated by liturgical and spiritual disciplines that manifests itself in “ethical thought and practice to which the gospel invites us” (

Miles 2021, p. 139). Preaching embraces a more conversational model as all of the faithful—and even the not-yet-faithful—gather to confront our shortcomings and construct a path toward spiritual maturity. Preaching in hope grounds itself in the teaching and practices of Jesus, who was himself grounded in scripture and practiced the mission of God—that of seeking

shalom. In doing so, empathy is encouraged, hope is assured,

3 and ethical action is cultivated among those who give ear to the sermon and believe its message.

As will be seen below, part of the reason for this is the practical nature of wisdom, the generally lived experience of the community that develops into a curriculum for ethical and spiritual development. Another part of this is the recasting of the role of the preacher from theological authority to fellow traveler on the road, which will also be discussed below. Wisdom homiletics, then, is not only a model for preaching from the wisdom texts of the Bible. It is a method, a paradigm, for understanding the nature and functioning of preaching, which is the very goal of homiletical theology.

Alyce McKenzie has been the trailblazing pioneer in this field. In her 2009 keynote address at the Conference on Preaching at Lipscomb University, McKenzie noted that wisdom is defined through two foundational principles (

McKenzie 2010, pp. 145–46). First, wisdom is part of the character of God. Second, wisdom is the curriculum through which a way of life, the path of discipleship, is communicated. Preaching in the vein of wisdom, then, seeks to answer the question of how we shall live by accomplishing three tasks: first, introducing the participant to the God who graciously and freely gives wisdom; second, introducing the participant to the collection of writings that communicates this divine wisdom; and, finally, guiding participants to imagine how they may live wisely. This is achieved not through offering the pithy platitudes of self-help pseudo-psychology, but through the casting of a vision of what it means to be wise against what it means to be foolish, for folly is a path that can be chosen just as easily as wisdom (more so, perhaps). This vision is based on three pillars of wisdom teaching: fearing God is having a healthy respect for God as Creator and Sustainer of life; wisdom is a path for living that must be intentionally chosen; and wisdom, ultimately, is a gift from God (

McKenzie 1996, pp. 36–38). Wisdom homiletics is defined by reverence, discernment, discipline, and moral courage. “In your preaching, try starting with folly’s answer for a change, so that its shallow, destructive face shows up in high definition. Then, offer people 3D glasses through which to view the way of wisdom: displaying its scenic beauty, using vivid language, imagery, and themes of the sages, Jesus included. Preaching this way may make our own steps along the way more confident. Additionally, if we close our eyes and listen, we just might hear the sound of new footsteps joining the wisdom journey” (

McKenzie 2010, p. 155). In short, preaching in the wisdom tradition generates faith in and for the next generation of believers. Hooke has recently argued that McKenzie’s model of wisdom homiletics can take preaching beyond the pulpit and into the public square, where the sages initially operated, to preach the fullness of God’s mission (

Hooke 2021, pp. 12–14). Additionally, Allen has argued that wisdom homiletics provides the preacher with an effective voice in an ever-growing postmodern context where authority for a metanarrative is losing cohesion (

Allen 2021, pp. 42–43).

3. Use of Didactic Rhetoric in Hebrew Wisdom Literature

Perhaps the place to begin as we transition to discussing the potential influence of Hebrew wisdom literature on the practice of homiletics is to ask simply, “What is wisdom?” Most, when thinking about this question, likely call to mind the opening words from the book of Proverbs: “The fear of the

Lord is the beginning of knowledge; fools despise wisdom and instruction” (1:7). As Bland notes, this passage is considered the “

leitmotif of proverbial wisdom” (

Bland 2002, p. 53). This recurring theme of fearing

Yhwh refers to “revering a particular deity” and was a common expression in ancient Near Eastern writings (

Clifford 1999, p. 35; cf. Deut 6:24; 10:12; 14:23; 17:19; 31:13; Pss 19:10; 34:11; 111:10; Prov 1:7; 9:10; 15:33).

4 As such, the concept of wisdom is presented in general terms. Wisdom can be considered a psychological mindset or attitude, a virtue that provides guidance, a physical manifestation (i.e., a collection of writings), or a community of experience. In the Hebrew scriptures, wisdom is wrapped up in the word

hokmah, which Hill and Walton say, “originally denoted some kind of technical skill, aptitude, or ability like that necessary for crafting wood and metal, artistic design and architecture, sea navigation, and even politics” (

Hill and Walton 2000, p. 319).

Hokmah can also denote intelligence (1 Kgs 4:29–34; 2 Sam 13), experience (Job 32:7) or insight (Prov 3:5). In short, wisdom, at least as understood by the Hebrew people in antiquity, was understood sociologically, as something that was inherent to a good and just society. In light of that understanding, scholars have worked to categorize the social world that wisdom fosters. Most relevant to this project is Blenkinsopp’s classic paradigm of “sage”, “priest”, and “prophet” (

Blenkinsopp 1995, pp. 1–2). The “sage” (

hakam) was the intellectual who provided instruction and wise counsel to the people of Israel. The “priest” (

kohen) was understood as a religious leader who presided over both liturgical practices and judicial or legislative functions. Finally, the “prophet” (

nabi) was understood as one who spoke for

Yhwh and whose functions included teaching, preaching, social criticism, political dissent, and charismatic expression.

This is a helpful starting place; however, Blenkinsopp’s model runs the risk of presenting ancient Israel as a class or caste system, limiting the sociological significance of

hokmah. Roland Murphy’s original sociological model, upon which Blenkinsopp appears to be drawing, proposed streams of development in the wisdom tradition (

Murphy 1981, pp. 6–9). Wisdom was generated organically in Hebrew society through several vectors, including clan or tribe elders, the government officials such as scribes, and the lay scholars who began collecting wisdom during the united and divided kingdom years and then later blending

hokmah with

torah during the exile years. As useful as Murphy’s model is, there are some significant concerns that have been raised over the years. Gottwald offers the clearest summary of these concerns (

Gottwald 1985, pp. 567–71). First, Murphy’s model assumes that each stream ended when the next stream emerged rather than continuing. Second, Murphy’s model forgets that what would become known as the wisdom corpus was an open and evolving collection, which, by its very nature, was systemically problematic. Third, it fails to consider the contrast between the external court context and internal familial context, especially post-exile, which would account for the mashup of content seen in Proverbs. Finally, it fails to consider that wisdom is not only a literary form or intellectual practice, but also an ethical-social construct that may have been understood and practiced differently in the various areas of Hebrew society.

Mark Sneed’s social archetype paradigm may be the best solution. Sneed argues that “While any Israelites could have lived a wise lifestyle, not all Israelites would have been considered sages” (

Sneed 2015, p. 20). Israelite society was made up of both professional and amateur sages who worked interdependently, often times in ad hoc ways, to form the wisdom tradition of Hebrew society. Examples of groups include parents (Prov 1:8; 31:1–9; Eccl 12:12), elders (Job 15:10, 17–18; Ezek 7:26), judges (Deut 1:9–18), kings (1 Kings 3; Prov 25:1), courtiers (1 Chr 27:32–33; Eccl 8:2–4), mantic sages/magicians (Dan 2:2; 11:33), and scribes (Jer 8:8–9; Prov 22:17). This model seems most appropriate for what is reflected historically in the Hebrew scriptures. Additionally, as McKenzie has noted (

McKenzie 2002, pp. 169–226), the wisdom tradition had a significant influence on Jesus’ ministry (e.g., in the beatitudes in Matt 5:3–12 and the “I am” sayings in the Fourth Gospel) and the mission work of the early Christians, as there is an inherent conversational and communal nature involved. As Gottwald notes, wisdom’s function was “to accommodate one’s life to the fundamental orderliness of the world, or what to do when the anticipated order fails” (

Gottwald 1985, p. 564). It is important to remember that the pursuit of wisdom has been honored in traditions throughout the biblical canon, beginning with the moment Adam and Eve first eyed that low-hanging fruit in Eden (Gen 3:6). In biblical traditions, this pursuit of wisdom is inherently theological; as Samuel Balentine notes, “Eve’s education takes place in God’s garden, however, not in Plato’s academy” (

Balentine 2018, p. 3). Thus, at this point, we are working under two basic assumptions regarding wisdom, as proposed by Bruce Birch et al. (

Birch et al. 1999, p. 373): first, “what happens socially, politically, economically, and militarily is the real stuff of life and the real agenda of faith. Israel knows that it lives in the real world”, and second, “Yahweh, the God of Israel, is decisively at work in the historical processes of the world”.

How should contemporary readers understand and communicate what is occurring in the wisdom texts? Here, we turn to rhetorical criticism, as it has the more relevant connection to the practice of preaching. When he proposed rhetorical criticism as a valid approach to hermeneutics in 1968, James Muilenburg had two foci (

Muilenburg 1969, pp. 8–10): first, rhetorical criticism would describe the structure and boundaries of a literary unit; and second, rhetorical criticism would describe the devices which provide shape and emphasis to the text. Muilenburg believed “that there is [a complex] relationship between form and content in the study of any biblical text” (

Dozeman 1992, p. 713). He insisted that the form of the text dictated the content of the text. The author’s intent is in

how they say something, not

what they say. Only in deciphering the form of the text can we decipher “the writer’s thought, not only what it is that he thinks, but as he thinks it” (

Muilenburg 1969, p. 7). Although the study of rhetoric is the study of the spoken word, it is important to remember that the written word is just as influential. Hayes and Holladay remind us that “biblical writings are ‘purposeful’ literature” and that the “Bible seeks to persuade the reader about certain truths, positions, and courses of action” (

Hayes and Holladay 2007, p. 92). The purpose of rhetoric, then, is “to persuade the audience to accept an argument … or adopt some course of action” (

Hayes and Holladay 2007, p. 92). In short, rhetorical criticism seeks to answer: “What is this text doing?”

Rhetoric does its work through a series of appeals that, when connected, persuade the audience to accept the rightness of the argument presented and to take appropriate action. The persuasiveness of these appeals involves the perceived ethical quality of the speaker (

ethos), the validity of the message (

logos), and the ability of the speaker to connect emotionally to the audience (

pathos).

5 The content of the argument is then arranged based on the intent or motive of the speaker.

Judicial rhetoric appeals to the court and seeks to defend or condemn another so that the judge will rule in the speaker’s favor (e.g., YHWH functions in an accusatory role in Job 38:4–7).

Deliberative rhetoric appeals to the legislature and seeks to persuade an audience to adopt a particular course of action, such as sanctioning a bill or supporting an election (e.g., Psalm 13).

Epideictic rhetoric appeals to the community and seeks to praise or blame an idea in order to challenge or reinforce that culturally held position (e.g., Prov 9:1–6). Sneed notes that some biblical scholars ignore the importance of rhetoric, especially

ethos, in studying the wisdom literature due to an assumed lack of scriptural authority given to this corpus. Sneed’s response is that this fails to understand that “the appeal to divine inspiration” is a form of rhetoric and fails to understand wisdom writing as a type of inspired writing (

Sneed 2015, pp. 253–54). However, as Dominick Hernandez has astutely noted, it is in the application of rhetoric that we are able to read scripture well (

Hernandez 2023, p. 33).

Finally, we consider the purpose of rhetoric as seen in the Hebrew wisdom literature. Gottwald is likely correct in his possible corrective to Murphy’s “streams” concept discussed above, where Murphy argued that wisdom developed in stages. Gottwald argues, rather, that wisdom (

hokmah) evolved as a social construct rather than as a type of literature, beginning with the clan and then moving to the state before finally being compiled by the religious leaders (

Gottwald 1985, pp. 568–71). This allows for Sneed’s social archetype paradigm while also providing room for Blenkinsopp’s theory to remain cogent to the discussion. Blenkinsopp points to the establishment of the scribes in 1 Kings 4:1–6 as the advent of what Gottwald labeled as state wisdom. The scribes (here,

soper rather than

mazkir, as they were initially referred to in 2 Sam 8:16) were instructed to write and catalogue everything, which Blenkinsopp argues is the beginning of the connection between

torah and

hokmah (

Blenkinsopp 1995, pp. 28–32). Thus, as Birch et al. note, we see the development of the following ethical paradigm in Hebrew life (

Birch et al. 1999, pp. 374–76). First, wisdom focuses on lived experience. Second, wisdom insists on the ethical significance of actions. Third, wisdom functions as a speech activity that reflects on and interprets experience. Fourth, wisdom functions as an intellectual endeavor, seeking to add to the corpus of learning. Finally, wisdom also functions as theological literature, not so much doctrinal but relational.

4. The Role of the “Sage” in Homiletic Discourse

This, then, leads us to the heart of the issue for this essay: how can the Hebrew role of “sage” (i.e., the wise teacher) be applied to the practice of preaching? If yes, how can this be accomplished? The second question will be the focus of the final section, where I offer a sermon sketch from a core Wisdom passage. First, we focus on homiletic models that have sought to apply the role of “sage” to homiletic practice, whether drawing from the ancient Hebrew concept or from a contemporary understanding. We turn now to the work of Robert Stephen Reid, Lisa Washington Lamb, and Alyce McKenzie.

In his work on the sage, Reid offers something of a paradigm shift in how the nature and function of preaching—specifically, the preacher—is understood. In his book

The Four Voices of Preaching (2006), Reid offers a response to Thomas Long’s highly influential

The Witness of Preaching (1989). Long, whose book remains one of a handful of core introductions to preaching, proposes four roles that preachers take—three that in his view are inferior and one that is superior. The inferior models (pastor, storyteller, and herald) favor function and performance over focus and content, opting for cultural relevance in presentation rather than gospel proclamation. Long argues that only the role of witness is appropriate for gospel proclamation, as the witness grounds itself in what has been “seen and heard” (Acts 4:20) rather than embracing the performative models of narrative or the bully pulpit. Reid’s argument is that all preaching that is offered with integrity of voice is witnessing to the gospel (

Reid 2006, pp. 10–11). If a rhetorical corrective is being offered by Reid, it is in form (i.e., the identity of the preacher demonstrated through an ethical practice of preaching) rather than function (i.e., the pomp and circumstance of flash and style now commonly associated with rhetoric). This concern has been aptly addressed by

Neal (

2020, pp. 32–57), and is being actively being countered by grassroots organizations such as the Dangerous Speech Project

6. For Reid, rhetoric involves voice, identity, and practice, not only the type of speech that is being performed. Thus, he argues for a spectrum of homiletic voices that witness to the gospel (

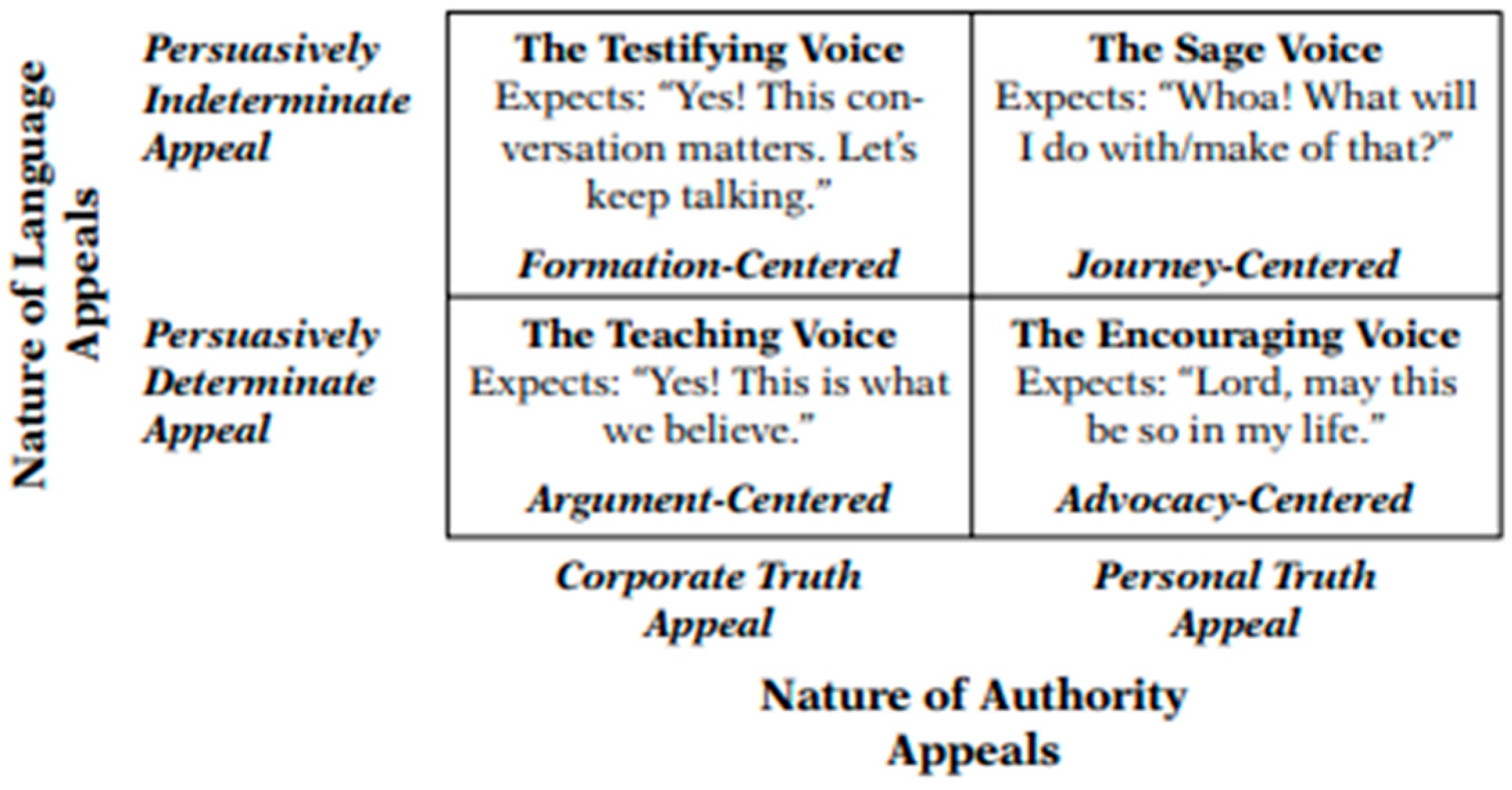

Reid 2006, pp. 20–22). From this position, Reid develops his “Matrix of Contemporary Christian Voices” (see

Figure 1), a model that is more integrative than exclusionary (

Reid 2006, p. 24).

Reid argues that although the preacher can embody each of these voices depending on the text and occasion, the preacher will likely come to embody one voice consistently, based on their place on the spiritual journey and application of preaching at that time. The Sage Voice is “journey-centered”, meaning that it invites the congregation “to

explore possibilities of meaning by offering critical reflection or

analysis with the intention that listeners would respond, ‘Whoa! What will I do with (or make of) that?’” (

Reid 2006, p. 25, emphasis original). Here, Reid’s position is congruent with that of Long, as Long also imagines the sermon process as a journey that the preacher invites the congregation on (

Long 1989, pp. 55–56). For Reid, the sage adopts an “interpretivist orientation” to the preaching act, functioning more like an anthropological or sociological linguist than an answer guide (

Reid 2006, p. 123). This preacher realizes that Christianity is no longer the only dominant conversational partner on the global stage of religious discourse. It is into this situation that the preacher enters to proclaim the Word of God. In the words of Brueggemann, we find ourselves in a state of spiritual “disorientation” (

Brueggemann 1985, pp. 20–21). However, preaching helps to reorient the world to the reality that God offers. As Thomas Troeger writes, “The task of preaching is to return us to a true assessment of our actual place in creation... Aware that our very existence is grace, gift from God, we no longer struggle with the illusion that we are the masters of life in control of our fate. Instead, gratitude, wonder, and worship become the defining characteristic of our life” (

Troeger 2004, p. 124). When we preach in the Sage Voice, we enter into the co-creator role with God, serving as the vessel through which God’s Word reshapes our culture and those who are present within that culture.

Lamb, in her work on the sage, presents a paradigm of active metaphors for preaching that are intended to guide preachers in seeing the act of preaching as a meaningful expression of discipleship—both theirs and those who give ear to sermons (

Lamb 2022, pp. xx–xxi). Using the image of the verb, Lamb argues that “preaching is a dynamic speech act” that “asserts a lively God who is active in the world and the heart of every listener” (

Lamb 2022, p. xviii). Pushing back against the critique that preaching has lost its relevance, Lamb argues that, like a symphony, preaching sounds different notes over the course of a minister’s tenure with a congregation. The preacher may be envisioned as a kind of pastoral conductor who seeks to strike resonance between the congregation and God through an authentic revelation of the homiletical self. It is through the sermon that the minister draws the congregation together and centers them before the text, offering a word from God through the power of the Spirit. Through the weekly work of pastoral proclamation, bonds are formed and relationships are built. God works in these moments, Lamb argues. How this occurs is through a multiplicity of sermonic offerings. The intentions of the preacher vary depending on text and occasion in order to bring about homiletic and theological resonance. Connection requires and manifests creativity in preaching; thus, several active metaphors are offered (e.g., preacher as host, proclaimer, priest, and catalyst). One of these active metaphors is the sage. However, Lamb dispenses with the Gandalf-like image of long beards, pithy remarks and a penchant for isolation. The sage, to Lamb, is the metaphor for seeking wisdom along the spiritual journey. Lamb encourages the preacher to “preach deep and practical wisdom, in part by growing wiser yourself” (

Lamb 2022, p. 42). Participants need to hear wisdom delivered from the pulpit because they seek a deeper understanding of spiritual practice, something that preaching as wise counsel can offer to participants. Here, the preacher speaks in the language of “we”, seeking not to speak to the congregation by dispensing content disguised as wisdom, but joining with the congregation in order to cultivate shared space “where the Holy Spirit may be doing unseen work” (

Lamb 2022, p. 43). Preaching becomes more conversational as the preacher accepts that they are not the source of wisdom, only a guide pointing the way to the true source of wisdom. Discernment, rather than sectarian adherence to fundamentalist positions, rules the day in interpretive practice and spiritual failure is welcomed at the table. Ultimately, preaching in the sage metaphor is an exercise in virtue—where justice, prudence, temperance, and fortitude are encouraged alongside faith, hope, and love. However, in order to grow in this type of practical wisdom, we who align ourselves with Christ must commit ourselves to the community of faith to which we belong so that “we grow wise by cultivating our love for what is life-giving and our repulsion from what is death-dealing” (

Lamb 2022, p. 46). To do this, the sage preacher engages in action such as defining wisdom, naming the paradoxes presented, demonstrating the ideal environment in which wisdom can grow, recognizing that wisdom produces fruit over time, and naming our internal resistance and external challenges.

McKenzie, in her work on the sage, offers the most complete and complex perspective related to our conversation. McKenzie’s perspective is one that has been crafted and cultivated over a period of nearly three decades, beginning with her first book

Preaching Proverbs: Wisdom for the Pulpit (1996) and continuing through books such as

Preaching Biblical Wisdom in a Self-Help Society (2002),

Hear and Be Wise: Becoming a Teacher and Preacher of Wisdom (2004), and

Wise Up! Four Biblical Virtues for Navigating Life (

McKenzie 2018), with a number of articles and essays published during that time. In

Preaching Proverbs, McKenzie first launched her argument that preaching needs to drink deeply from the well of biblical wisdom and that preachers should adopt the role of sage in their homiletical task (

McKenzie 1996, pp. xi–xiii). We are surrounded by proverbial wisdom, meaning our culture is seeking something deeper than sound bites in its quest for meaning. However, when those seeking wisdom turned to the church in the twentieth century, they were not finding what they were looking for, namely, wise counsel for the journey. Instead, McKenzie argues, they found hollow platitudes and doctrinal propositions, with the first leaving a saccharine taste in the soul and the other assuming a connection that was becoming more and more fragile amid the burgeoning of postmodernism. Given the generality and vividness of proverbial literature, McKenzie argued that late-twentieth and early twenty-first century preachers would do well to recover the rhetorical orality of the proverb and take up the mantle of the sage, as seen in the poets of the Hebrew scriptures as well as in Jesus’ preaching (

McKenzie 1996, pp. xvii–xxii). Through this more inductive model to preaching (à la Fred Craddock’s influence), preaching would meet participants where they are on the spiritual journey and provide them with the sought-after wisdom that would help them grow as disciples, what she refers to as “steering (

tahbulot)” (

McKenzie 2002, p. 21). In order to accomplish this, McKenzie argues, the preacher must “glean in [biblical and cultural] fields alongside our people”, searching for God’s gift of wisdom together in hopes of “bringing them to life” (

McKenzie 2002, p. 25). This gift is a resource for life, not a set of principles; it is found out at the margins of existence. Thus, the sagely sermonizer engages in a dialogical conversation with their participants, leveling the ecclesiastical playing field through the practiced disciplines of observation, empowerment, and community. Rather than only interpreting scripture, we allow scripture to interpret us as we seek to discover what the kingdom of God is like and how we will live as citizens of this kingdom (

McKenzie 2007, pp. 1–3).

More recently, McKenzie has revisited her initial argument for seeing preachers as sages as part of the generative conversation regarding homiletical theology. McKenzie returns to her initial concern that contemporary preachers are neglecting wisdom in favor of spiritual platitudes and propositional statements, despite the advancements that have been made in more inductive and conversational forms of preaching (

McKenzie 2015, pp. 90–91). Thus, the contemporary preacher needs the sage: “The sage is one who is both growing in wisdom and using that growing wisdom to adjudicate the use of existing insights” (

McKenzie 2015, p. 91). Here, we see a new development in McKenzie’s thought—the very growth in wisdom that she promotes. Whereas her earlier thought focused on demonstrating wisdom for the purpose of maturing the community, we now see a new outcome—demonstrating wisdom for the purpose of bringing

shalom to the community through “discovery and its ongoing contextualization” (

McKenzie 2015, p. 92). Method for homiletical theology emerges, something McKenzie labels a “sapiential hermeneutic” (

McKenzie 2015, p. 92). It is here that McKenzie offers the interpretive lens through which homiletical theology will do its work of fostering hope. Theology must not remain untethered in the existential ether; it must be given life and substance, lest the wisdom germinating in theological exploration withers on the vine. As a discipline of practical theology, preaching is where theological understanding is cultivated and communicated. Wisdom becomes wisdom when thoughtful reflection leads to contemplative action, what

Aristotle (

2004) termed

phronesis. This activity, McKenzie argues, compels us to remain open to the broad experience of others. Preachers as sages do not simply dispense theological content, but engage in theological exploration, guiding participants to discern God’s wisdom for their lives within the guidance of the Spirit. The “sapiential hermeneutic”, then, is a communal activity that embraces complexity, ambiguity, humility, diversity, attentiveness, courage, and adaptability (

McKenzie 2015, pp. 98–99). In the end, the preacher who engages the homiletical task through this method will see the beautiful work of transformation occur within their very souls and before their very eyes.

Each perspective of how to understand the sage homiletically offered here is unique in its own way. Robert Stephen Reid works with a paradigm for preaching identity, Lisa Washington Lamb offers a paradigm for preaching activity, and Alyce McKenzie presents a paradigm for preaching function. However, there are three threads that draw these seemingly disparate conversations together into a unified image of what we have termed “wise preaching”, a homiletical theology stance rooted firmly in the wisdom tradition. First, there is a focus on the preaching moment as a journey, specifically one that the preacher shares with the congregation. This goes beyond the crafting of the sermon, often noted as a journey “from text to sermon”. No, here the journey is not one that ceases with the altar call, but continues through the week and courses through the lives of the congregation. In wise preaching, what comes after the sermon is of more theological and practical significance than what had been offered in the pulpit, as the teaching of the sermon is worked out by the congregation in moments of pastoral care and pastoral administration. Rather than simply note this unique use of the Greek in Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians or that foundational application of scripture in Barth’s theology, we walk alongside the congregation in the practice of sharing the life of faith together. Second, in all three models there is a focus on the interpretive stance taken by the preacher and, thusly worked out through a more conversational approach to the preaching event, the congregation. There is an intentional ambiguity present in wisdom literature which prevents sectarian interpretation. There is an inherent fluidity to this material, even seen in Jesus’ parables, riddles, and didactic speeches. As such, care must be taken when preaching in this vein—especially if one adopts more of McKenzie’s argument for the sage as the paradigm for the preaching function. We engage in conversation and reflection, asking ourselves what is happening in the text and why it matters to us today. In discovering the answer, we discover a new transformative moment. Finally, there is a focus in each of these models on practical application. Wisdom is only wisdom through living out the teaching, discovering its contours and limits. We can engage in all the conversations we wish and still never discover hokmah (or sophia, if you wish) until we pursue shalom in the community. The sage is outward-focused and forward-thinking, pursuing hope with each step. Preaching may not provide the answer, yet it should provide a response—even if that response is an “I do not know”. After all, wisdom reminds us that there is “a time to keep silent and a time to speak” (Eccl 3:7b).

5. Sermon Sketch (Ecclesiastes 12:1–8)

The final move of this essay will be to offer an application of all that has been discussed through the crafting of a sermon précis from a core wisdom text. The text selected for homiletical consideration is Ecclesiastes 12:1–8, the conclusion to Qohelet’s rhetorical and philosophical exploration.

7 This text has been selected because of its connection to Proverbs 1:7, as “Remember your creator“ in Ecclesiastes 12:1 correlates to fearing

Yhwh. Wisdom is understood in Ecclesiastes as comprehending the purpose of

hevel (here understood as “breath”); thus, one should learn to live in the mystery and embrace the good that is given. The sermon will follow the author’s own “transformative” model of instruction (What does the text say?), reflection (What does the text mean?), application (What does the text do?), and transformation (To what extent is this true in my life?), which manifests itself through spiritual maturity (

O’Lynn 2018, pp. 103–108). It is believed that participants will engage in transformative discipleship as the result of this method of preaching, as they are confronted with the teaching of scripture, engaged in conversation as to its meaning, and then challenged to implement the teaching of scripture in their lives. Furthermore, this model appropriately reflects the goals of the “wise preaching” of wisdom homiletics.

Introduction: How do we define the measure of human existence? Anecdotally, we refer to this as one’s “dash”, that line on the tombstone that connects one’s birthday with one’s day of death. Imagine the last funeral that you attended. What was said about the deceased? Did the words paint a picture of someone who lived a rich, full life? Or were they words that lamented a poor, foolish life? I do not intend these thoughts to focus on the heavy burden of death, for death, at least for a person of faith, should be a celebration of crossing over to what C. S. Lewis called “that true country” where we long to rest in God’s presence (

Lewis 2000, p. 137). Instead, my intention is to ask us how we are living. Are we living wisely or foolishly?

Instruction: The book of Ecclesiastes speaks well to this theological concern, for the book—like my question—can be misunderstood. It is often assumed that Ecclesiastes is pessimistic, dark, and brooding, more Eeyore than Winnie the Pooh. However, when read as it is written, we see that this is not the case. The book begins with a poem, offered by a narrator—the actual author of Ecclesiastes—who presents the words of Qohelet, the Teacher. This unnamed poet offers words that are summative, words scribbled by someone who is taking stock of the life that he has lived up to that moment. As Qohelet looks back over his life, he is discouraged. The word here in Ecclesiastes 1:2 is hevel, which is often translated as “vanity”. However, “transience, vapor, insubstantiality” would be a better way of understanding this word. Life is simply a breath, a moment in the passing of time. Additionally, Qohelet is not sure that his life has measured up to much.

The poet presents Qohelet and his meditation for the reader’s consideration. Qohelet is presented as a royal individual who has stepped away from his palace duties to pursue worldly pleasure in order to test his training in wisdom, ethics, politics, and psychology. We are then invited to follow along as Qohelet recounts his adventures to determine whether life is really just a vapor. Qohelet reports that he applied himself intently to his experiment, enjoying wine, women, and wisdom. He rides the tides of life, saying “all is vanity” (Eccl 1:14) on one hand, yet also exhorting his audience to “enjoy life” (Eccl 9:8), on the other. Additionally, as we turn to today’s text, we would not be faulted for seeing Qohelet as tired and weary, an exhausted professor falling into his chair following the end of a grueling semester as he contemplates retirement.

And yet, what he says in today’s text is vitally important to understanding the message of Ecclesiastes and, I might argue, the entirety of scripture. Looking back on all that he has experienced, Qohelet looks to the eager student who has come seeking guidance from the tired professor and says, “Remember your creator in the days of your youth, before the days of trouble come and the years draw near when you will say, ‘I have no pleasure in them’” (Eccl 12:1). There is a glint in his eye, an uptick in the timbre of his voice. Qohelet remembers the innocence of youth and longs for those days once again. In what is an unbroken single sentence in Hebrew, vv. 1–7 leave the reader out of breath, much like the breathlessness the student will experience as she ages. Thus, Qohelet’s admonition is not trite or clichéd, but the summarized fullness of life itself: remember who God is, that life is beyond our control and remains an unknowable mystery; thus, we should enjoy the life that God has blessed us with in a way that honors God.

Reflection: What exactly does this mean? Ecclesiastes is, after all, part of the Hebrew wisdom collection. However, it offers a perspective different from that of Proverbs, which presents a beautiful, hope-oriented meditation on wisdom. Proverbs is certainly the Winnie the Pooh of these scriptures, if that beloved bear be taken to represent warm, positive advice for living a happy life. Winnie the Pooh pursues a simplicity of life that is guided by common sense and peacefulness (

Milne 2023). This is not to say that Ecclesiastes is the pessimistic Eeyore. Ecclesiastes is more like Rabbit in the Hundred Acre Wood—one who takes quiet pleasure in the care of his work yet falls to existential pieces when the unruly Tigger bounces through his garden. As we reflect on the life that he has lived, you can see Qohelet pushing toil and trouble out his door. “Out! Out! I have a life to live!”

Which brings us back to our opening question about defining the measure of human existence. Ecclesiastes does present a differing perspective on life than that of Proverbs, although it is not necessarily a pessimistic perspective. It is a meditation on how to live a good life, one that honors God. Honestly, this is difficult to see in Ecclesiastes because we have been socialized to understand hevel as “meaninglessness” or “vanity”. However, in the meaning of this word—“breath”—we find the meaning of human life itself. We are only given one life to live. The question is how we will live that life well.

Perhaps an illustration will help. Think of a bottle filled with perfume, like the bottle that sat on your mother’s counter. Spray the liquid and notice how long it hangs in the air. Yes, it disappears quickly. However, a pleasing scent is left behind. Additionally, this is what we are to think with the word hevel. We are here for only a moment in the grand scheme of history. However, if we live well, we can leave behind a pleasing aroma.

Application: Given all this, how should we live? When it comes to defining wisdom, there are many options. However, wisdom as lived experience is most akin to the biblical concept. In short, it is the difference between knowing how to change the oil in your car (which I do) and actually doing it (which I do not). When it comes to living wisely, do we honor God in how we live? Do we cause others to remember God when they see us? As a challenge, compose your own eulogy. I know, death again. However, seriously, what would people say about you at your funeral? Would you be considered one who has honored God, who has lived wisely? If so, what can you point to that you can share with others? If not, what wise changes do you need to make? Ultimately, as Qohelet reminds us, life is beyond our control. What we can control, however, is the moment in life that we have been granted. Will we live foolishly, or will we live wisely?