1. Introduction: Developing a Post-Holocaust Perspective on the Byzantine Liturgy

Many areas of Christian theology underwent an inevitable transformation after the Second World War, to the extent that one sometimes speaks of a post-Holocaust theology (

Palfi 2017). Of course, not all areas of theology need to be rethought in this new light, but some areas simply cannot avoid confronting content written many centuries ago with new historical, political, and social contexts. My attention in this paper is particularly directed towards liturgical texts, with a special focus on the image of the Jews in these writings and how they are used today in the Byzantine rite. Unlike the Byzantine rite in use in the Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church identifies itself with the Byzantine rite, being the only rite used in local Orthodox churches, with tiny exceptions. While in the Catholic Church, there have been several councils in recent centuries that have discussed how to adapt biblical and liturgical texts to the new concrete contexts of Christian life, in Orthodoxy, there have been no such discussions, but unique and courageous voices recently emerged (

Seppälä 2019, p. 197). The Second Vatican Council of 1962–65 is the most relevant event for our discussion from a Catholic point of view because it was a crucial moment in changing the Catholic Church’s hostile attitude towards the image of the Jews in its liturgical texts. At that time, the majority of Orthodox countries of Eastern Europe were under communism and unable to discuss such topics (

Ioniță 2017). The post-communist period delayed and complicated things such that, today, the topic has become a very delicate one, which instigates countless rumours and misunderstandings between Orthodox theologians and representatives of Orthodox churches.

The fact that the topic of anti-Judaism in Orthodox liturgy and theology is not a recent innovation imposed by some “foreign agenda” of Orthodoxy—as some Orthodox theologians often react—is proved by the fact that since the 1960s, in parallel with the work of the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), Orthodox theologians raised the issue of anti-Jewish texts in Orthodox worship (

Alivizatos 1960). Then, a decade later, from the first dialogue sessions between representatives of Judaism and Orthodox Christianity, the issue of anti-Jewish invective was recurrent, up to explicitly expressed disappointments on the part of Jews in the Jewish–Christian dialogue (

Pătru 2010;

Poirot 2019). These disappointments and, ultimately, the declining interest in dialogue that followed between Judaism and Orthodox Christianity are currently being revisited. In Orthodox churches, expressions like “murderous Jewish people” and other invectives against Judaism and the Jewish people

as a whole are sung, to the extent that these anti-Jewish liturgical texts have been considered a “stumbling stone” of the Jewish–Orthodox Christian dialogue (

Ioniță 2019).

Despite these difficulties and bottlenecks, the last five years have seen a revival of interest in the Jewish–Christian dialogue from an Orthodox perspective, especially in this sensitive issue of liturgical anti-Judaism. The most concrete proof of this can be seen in the emerging groups of scholars who have devoted themselves to these topics and published volumes indispensable to our theme. The oldest one is the Jewish–Orthodox Christian dialogue group in Great Britain, led by Prof. Rabbi Nicholas de Lange at the Faculty of Divinity, Cambridge, in which some of the most influential Orthodox theologians have participated annually. This group included, for example, Kallistos Ware, Andrew Louth, Sergey Hackel, Elena Narinskaya, Elisabeth Theokritoff, Michael Azar, and others, whose contributions have only this year seen the light of print, although they have been collected for over two decades (

De Lange et al. 2023a,

2023b). Another very recent research group, more visible and very promising, is moderated by Rev. Dr. Ready Geoffrey at the Orthodox Theological Society in America (OTSA) and is called “Orthodox Christians in Dialogue with Jews”

1. A similar group operates in the French-speaking area called “Chrétiens orthodoxes en dialogue avec les juifs”

2, led by Dr. Sandrine Caneri, who recently proposed a redefinition of the conditions for dialogue between Orthodox Christians and Jews (

Caneri 2019). Last but not least, I should mention the research project on the

Jewish–Orthodox Christian Dialogue in Sibiu, Romania, which issued some important publications and, in 2019, organised the first international conference dedicated to the image of the Jews in the Byzantine liturgy (

Byzantine Liturgy and the Jews) and managed to bring together many of the researchers mentioned above, thus contributing substantially to advancing discussions on this topic (

Sabău 2019).

With this revival of interest in the topic of Orthodox liturgical anti-Judaism, it is only in the last decade that the consistent discourse on this topic in the Orthodox context has made itself felt. Although somewhat belated and fragile, sensitivity to the relationship between Orthodox theology and Judaism has taken important steps. In addition, more and more Jewish theologians and rabbis have shown increasing interest, some even making concrete proposals for how these medieval Christian texts might be approached today.

A very well-articulated suggestion from the Jewish scholar Amy-Jill Levine offers the following solutions to the anti-Jewish elements in the Byzantine liturgy: “1. Excision, 2. Retranslate, 3. Romanticise, 4. Allegorise, 5. Historicise, 6. Admit the problem and deal with it.” (

Levine 2012). For this list, I would simply add the resistance to any such discussion, as recently a doctoral dissertation written by an Orthodox theologian simply ignores the subject and finds the discussion unconvincing (

Damaschin 2022, p. 381). Another viewpoint from the Orthodox camp in favour of removing anti-Jewish elements from Byzantine liturgy comes from positions expressed by Kallistos Ware, Andrew Louth, and Sandrine Caneri. According to them, the dialogue of Christian Orthodoxy with Judaism, the Pauline text of Romans 9–11, and the discussion of liturgical anti-Judaism are pressing and fundamental and do not necessarily need a Pan-Orthodox Synod to endorse them (

Caneri 2019, pp. 160, 163).

2. Methodology, Limits, and Aim of This Study

The truth is that none of Amy-Jill Levine’s proposals present anything very new and innovative, and they are all objectionable to the Orthodox environment. All of them have already been mentioned in various publications, but the merit of her article is in systematising them, presenting them briefly, and grouping them together. Each method of approach can refer to dozens of liturgical hymns, but all these methods have their place and purpose. The problem is mainly one of

systematisation, since the corpus of Byzantine liturgical texts is immense, and the

criteria for identifying and dealing with anti-Jewish elements are not yet formulated. In addition, there are still no critical editions of Byzantine liturgical books, and the hymns contained in printed liturgical books do not include all the existing hymnographical creations (

Tucker 2023;

Olkinuora 2015). Therefore, I thought it appropriate at this stage of the debate to situate this study in Levine’s sixth category: “admit the problem and deal with it.” (

Levine 2012)

Here, I must emphasise the two verbs

admit and

deal because many Orthodox theologians who are against this discussion of liturgical anti-Judaism simply

do not admit that there is a problem with these hymns and

do not intend to address such topics. As an orthodox author very recently stated in his dissertation on Holy Week, there are yet not enough reasons for engaging in this discussion “lest, out of misunderstood pacifism, doctrinal compromises or betrayals of the vision of the Church Fathers be made at odds with the Church’s balanced but firm biblically based vision of the actors and perpetrators of the Crucifixion.” (

Damaschin 2022, p. 359, n. 1158). A more balanced opinion, but still inclined to keep hymns with violent language against the Jews, is that of the Orthodox theologian Alexandru Mihăilă, who pleads for justifying them from the perspective of the Byzantine discourse related to identity. They are not meant for a Jewish audience but addressed to a Christian audience, in the Church, and their purpose is to reinforce the audience’s collective sense of identity (

Mihăilă 2019, p. 252).

So, if we admit and wish to address these anti-Jewish elements, it seems that the most necessary questions now are as follows: (1) What texts are we talking about? (2) Which are, precisely, the texts in question? (3) How many texts are problematic, compared to the Byzantine liturgical corpus? None of these fundamental questions have been asked, and therefore no answer has been given. Most of the publications that have already appeared mention texts deemed by each author to be problematic. Texts, especially from Passion Week, have been discussed, but no one has placed them within the broader picture of the liturgical context.

The present study involves no more than simply counting the Triodion’s total number of hymns and the hymns that contain the term

the Jews, and then I flag those I consider problematic and worthy of discussion. To approach this in the limits of an article, I have chosen to focus on the period of the Triodion, which is the liturgical season most relevant to our discussion. Most of the existing publications mention texts from the Triodion and less from other periods of the liturgical year. At the same time, the period of the Triodion overlaps and encompasses the fasting or pre-Easter period in the Byzantine tradition, culminating in Holy Week. It is important for this stage of the discussion to graphically and quantitatively visualise how much the Triodion period represents compared to the Pentecostarion and Octoechos periods of a church year (

Figure 1). The numbers in the adjacent graph show that, around the main feast of the church year, Pascha, or Resurrection, the Triodion precedes it by 10 weeks, the Pentecostarion follows it with 7 weeks, and the rest of the year is covered by the Octoechos, lasting around 35 weeks. We should not lose sight of the fact that the period of the Triodion is so called because of the liturgical book of the same name, which comes from the hymnographic composition of three odes. This liturgical book, like the Pentecostarion and the Octoechos, contains thousands of poetic stanzas called troparia, mainly organised in hymnographic canons, each with three or more odes (

Nikolakopoulos 1999, p. 69). They are the melodic accompaniment and poetic meditation on the biblical texts that are read in the liturgy and are of major importance to us because they are the most accessible biblical commentary to the faithful, the most listened to, and the most known in the history of the Orthodox Church. In addition to the biblical text itself, read partly in the liturgical setting through the biblical lectionary, the rich Byzantine liturgical hymnography offered the hearer the already “chewed” nourishment of a particular understanding of the biblical text heard in the liturgical setting (

Rapp and Külzer 2019;

Pentiuc 2021).

One more methodological clarification must be made here: I use the term Jews, corresponding to the Greek oi ioudaioi, written in italics and without quotation marks, referring not to the Jews of today, or those of two millennia ago, but to the image that will be woven through countless occupations and interpretations in the Christian context, beginning with the Gospel of John and culminating in the obsessive repetition of this term during the Passion Week of the Triodion. Of course, the same approach is worth applying to other Byzantine liturgical periods or books, but that means at least a separate study of each.

3. Mapping the Jews of the Triodion

The liturgical book Triodion is very relevant to our discussion, and I begin my quantitative analysis precisely with the Triodion not only because this liturgical book contains the services preceding the Easter feasts and Passion Week but also because this liturgical period is the most frequented by the Orthodox faithful. The texts of the Triodion are generally more familiar to those who attend liturgical services than those of the Pentecostarion or the Octoechos. This observation adds an important dimension to the liturgical texts, namely the performative dimension. It is a well-known fact that of the many liturgical texts provided for a particular liturgical day, not all are read, and not all are heard by the faithful; some are chanted, some are not chanted, and all these differences in the way the texts are performed are of considerable relevance but can only be partially addressed in this study.

For the time being, it is very relevant for us to perceive the information about the number of hymns or troparia that could be discussed in the whole Triodion and the relationship between their number and the total number of hymns contained in this liturgical book. But just counting the hymns is not a simple process either, since we do not have a critical reference edition in academic circles for this liturgical book. In the absence of a critical edition, we are left to deal with the textus receptus, as it has been in print since the 16th century.

3 In addition, the existing Greek editions are slightly different from Slavonic ones, in the sense that the Slavonic tradition has functioned mainly through the accumulation and collection of new texts, while the Greek tradition, especially in the last two centuries, has resorted to minimal retouching, renunciations, and adaptations to the older manuscript tradition. Thus, in the Slavonic tradition, we often find a few more hymns or an extra hymnographic canon on a particular feast, while these are today missing from the Greek version of the Triodion. Despite these minor differences between the traditions mentioned, the Triodion contains, in any variant or tradition, more than five thousand troparia

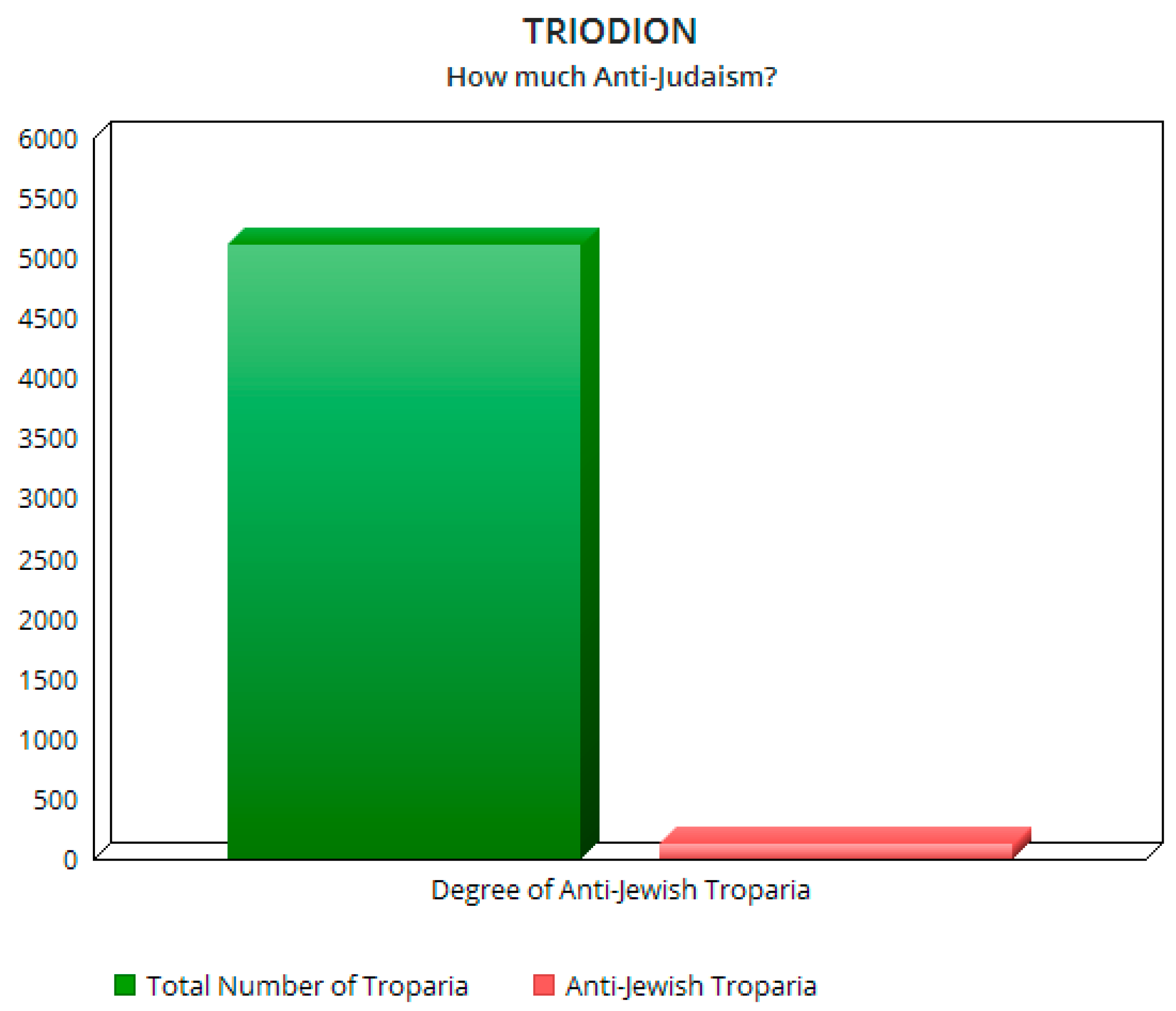

4, of which no more than two hundred can be suspected of anti-Judaism (

Figure 2). This does not mean that all these hymns can be proposed for “excision”—to use Levine’s terminology—but simply that only 4% of the Triodion hymns are questionable. We shall see later on that, out of this 4%, only a part is even in a situation where the hymns can be proposed for

exclusion from the liturgical corpus altogether, while others can be easily

modified by translation or even simply

explained to the faithful without any modification. Which hymns fall under the “excision” category and which are in the “transforming by translating”

5 category can only be precisely determined after some clarification regarding the

criteria for selecting and sorting out hymns. For now, these numbers should be enough to make us aware that Byzantine hymnography, or Orthodox liturgy for that matter,

cannot be labelled as anti-Jewish and that the texts I discuss represent a

very small part of the liturgical corpus standardised by the printing of liturgical books in the post-Byzantine period.

The reluctance of many Orthodox theologians to the charge of anti-Judaism is, however, largely justified, since some accusers see nothing else but anti-Judaism in the Byzantine liturgy, or in the writings of the “Holy Fathers”. While some are irritated that a venerable tradition, such as the Byzantine patristic tradition, can contain anti-Jewish elements, others are deeply attached to their own tradition and can neither receive the accusations nor discuss them. Some Orthodox authors have even approached the complexity of these situations (

Seppälä 2019), or rather emphasised the rich Jewish heritage in Byzantine services (

Moga 2019). But from this quantitative perspective on hymns and looking at the anti-Jewish percentage, we can approach this discussion much more impartially and objectively if we realise that the “bone of contention” constitutes a small fraction of the hymnography compared to the entire Byzantine liturgical heritage.

In what follows, I will trace the weight of these hymns throughout the Triodion and how and when the anti-Jewish voice makes itself heard in the liturgical setting, because liturgical moments are very important from the perspective of the reception of these texts, too.

3.1. Pre-Lenten Period of the Triodion

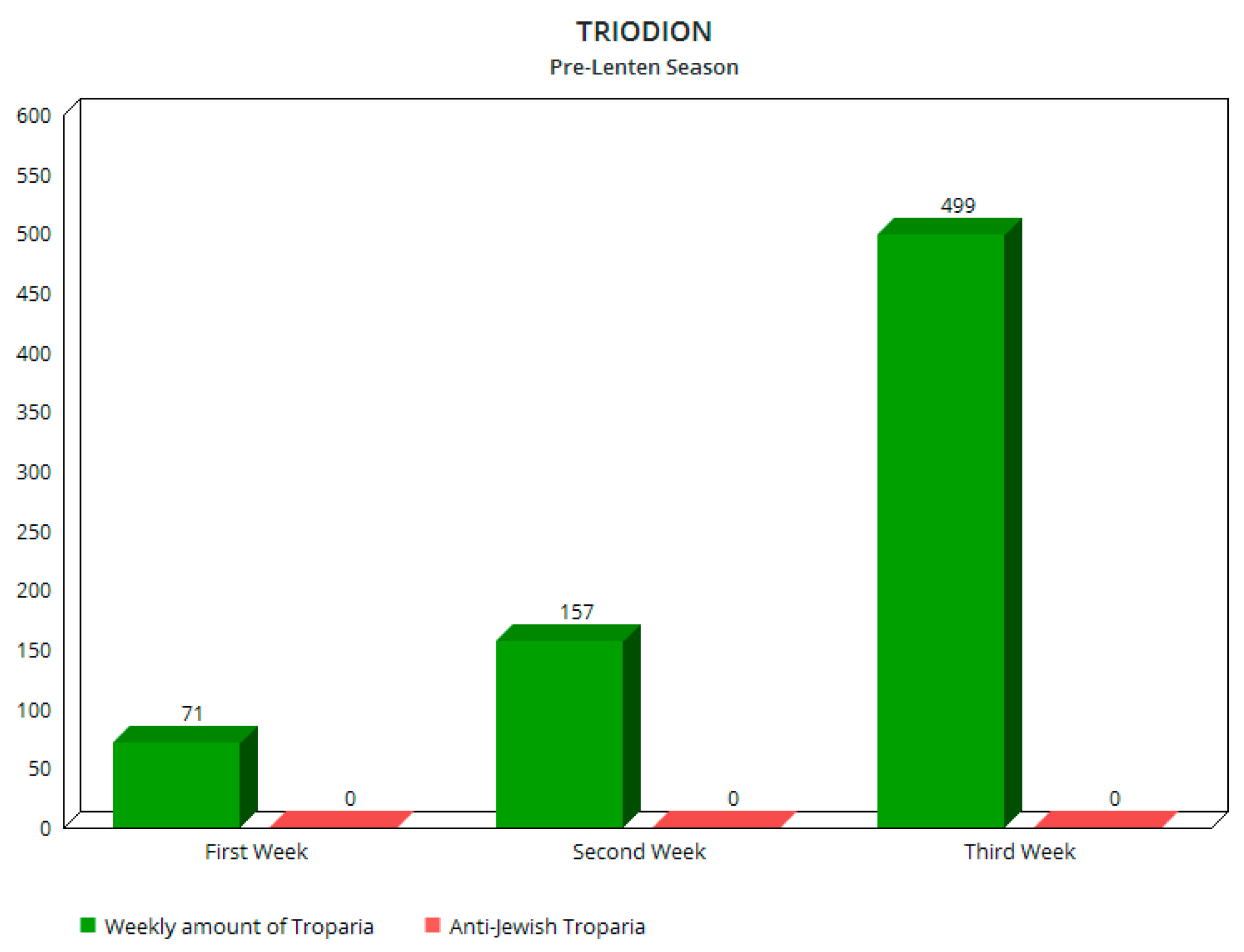

The season of the Triodion, itself a preparation for the great feast of the Resurrection of Christ, also has a period of initiation, which gradually introduces believers to the proper Lenten period. This three-week pre-Lenten period is characterised by the invitation to gradually give up eating meat and dairy products, in effect replacing material food with spiritual food. From the graph in

Figure 3, it can be seen how the number of troparia increases significantly during this period, suggesting to Christians that the place of material food should be taken by spiritual food, through biblical readings and liturgical hymnody. The fact that Byzantine hymnody is not a programmed anti-Jewish creation can also be seen from the fact that in this period, which calls for repentance and humility, we find no concern for the vehicle of any anti-Jewish invective. The atmosphere becomes increasingly sober, and the focus is on inwardness and self-inquiry. The table clearly shows how many hymns are present during this period and how many are questionable from our point of view (

Figure 3). The green columns show that the number of weekly troparia gradually increases to five hundred, demonstrating the gradual intensification of liturgical life as we approach the season of fasting. But throughout this time, we find no anti-Judaic elements, although emotions play an important role in the poetic rhetoric composed especially for these days (

Mellas 2020). Also products of strong emotions (

Lash 2006), hymns with anti-Jewish content do not pervade liturgical hymnody but are reserved for certain periods, being “triggered” by particular historical–theological themes, such as accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion, or statements about the Old Testament Law and its relation to the New Testament.

3.2. The Lenten Period of the Triodion

The Lenten period is the most intense and rich liturgical period of the church year both in terms of the number of liturgical services and hymns and in terms of the quality of the musical compositions, the theology of the hymns, and the experiences to which the participants in liturgical worship are invited (

Mellas 2020, p. 9). An overview of the Lenten period shows that the average number of troparia performed in a liturgical week is about five hundred, except for the first and fifth weeks, when the number exceeds seven hundred (

Figure 4). The reason for this crowding of troparia in these two weeks of Lent is that the Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete, an exceptional hymnographic composition that alone exceeds two hundred and fifty stanzas, is performed then. An adjacent but relevant observation for us at this point is that the whole of this poetic composition of St. Andrew makes unexpectedly great use of the Old Testament and exemplary characters from the Jewish Scriptures, without touching any anti-Jewish themes (

Prelipcean 2017;

Macaire 2018;

Leśniewski 2022). The author shows an astonishing knowledge of the Jewish Scriptures and interprets them typologically but without falling into the temptation of gratuitous invective against

the Jews, although elsewhere he does that, both in hymnographic and homiletical compositions (

Cunningham 1997). The Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete is par excellence oriented to the believer’s self, not towards

the other, neither to

the Jews nor to the heretics, since it is “a multimodal self-communicative text”, as a very recent analysis characterises it (

Van Boom and Olteanu 2023).

It is also during this period of Lent that most of the Old Testament is read, the Psalter is read twice as intensely as at the other time of the year, and some fundamental biblical passages are present only during this period in the Christian liturgical framework (

Magdalino and Nelson 2010;

Pentiuc 2021). It is known that the whole period of Lent was originally an intense introduction to the mysteries of the Scriptures (Old Testament), and not surprisingly, it is precisely during this period that we find the most numerous references to Jewish biblical texts and characters from the Jewish tradition. But problematic expressions from our point of view are unexpectedly few compared to the number of harmless or even positive hymns concerning

the Jews in a week. Nine troparia out of seven hundred and ninety-nine (1.13%), or five out of seven hundred and forty-seven (0.67%) are telling numbers by themselves (

Figure 4). It is only in the last week, before Passion Week, that the number of anti-Jewish troparia increases, or rather doubles, compared to the average of the previous weeks.

3.3. Holy Week

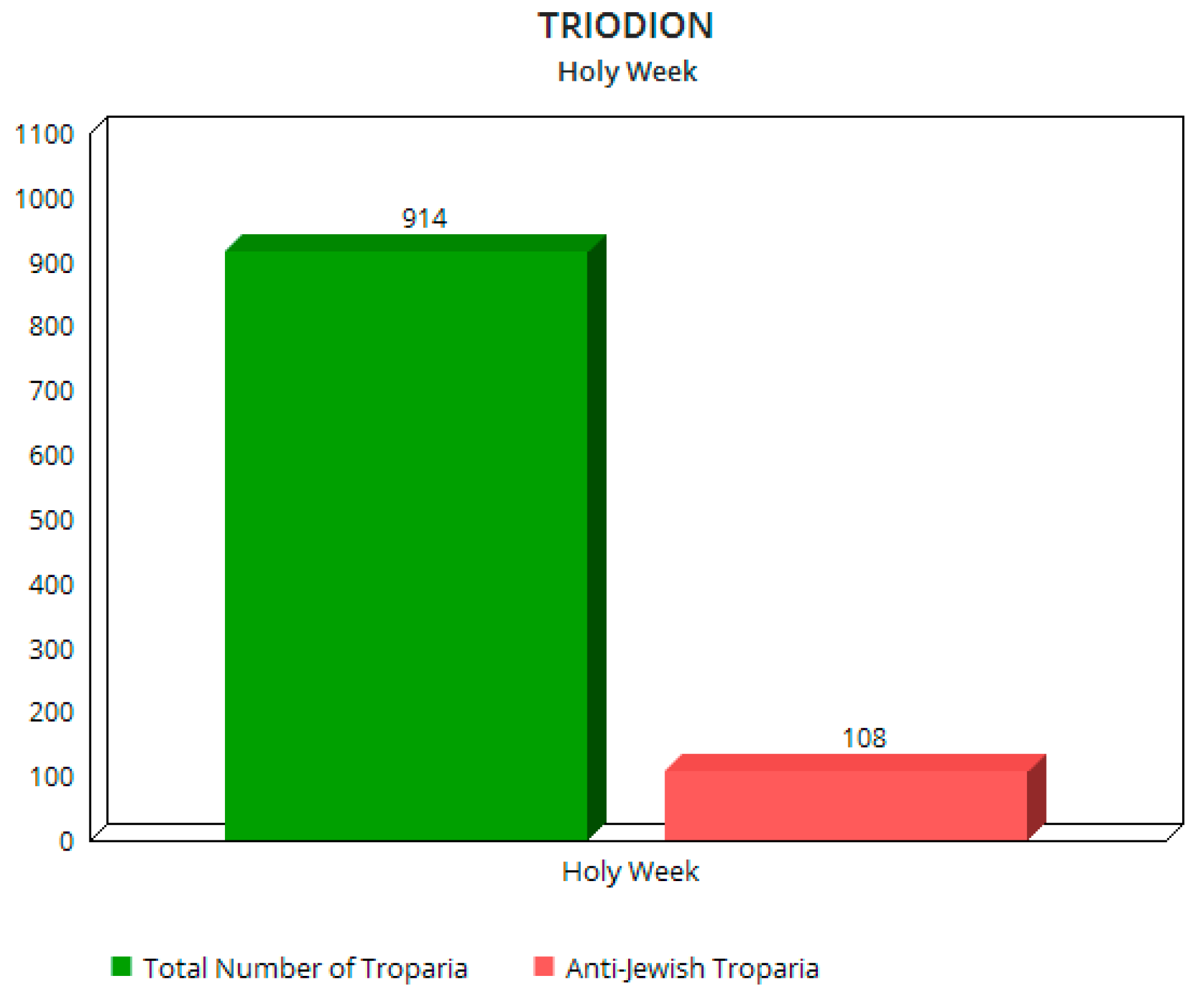

As expected, most of the harsh invective and the most problematic anti-Jewish elements are found in the last pages of the Triodion, which contain Passion Week services. But even here, it can be seen that not always and not everywhere is the voice of anti-Judaism heard. Nor is it a dominant voice in Passion Week, the number of occurrences of the term

Jews increasing especially in the last days, which commemorate the Crucifixion and Death on the Cross of the Saviour. An overview of the whole week shows that the fraction of texts with anti-Jewish content exceeds 10% of the total number of troparia, indicating that the number almost doubles during this week (

Figure 5). One could say that with the double number of troparia during Passion Week (914 troparia compared to the average of 500 in the previous weeks), it would almost have been inevitable that the number of anti-Jewish elements would have doubled (from 4% to 10%). But let us not forget that these anti-Jewish elements are not evenly distributed over a liturgical period but are overrepresented at certain key points, especially in the last three days of Holy Week. Here, the perspective of liturgical performance must also be added to the discussion, since the multitude of these hymns are, in fact, rarely performed fully. All these rites and numerous troparia are intended for services in a monastic context. In the Byzantine rite, unfortunately, there is no different liturgical ordinance for parishes. So, parishes in towns or villages simply

do not celebrate as many of the services provided in the Triodion (nor do all monasteries celebrate at absolutely all the liturgical hours, for example, or the Compline). This means that much of the Triodion hymnody is not heard in church by the faithful at all. The most attended services by a large mass of Orthodox faithful during Passion Week remain Thursday and Friday evenings—in liturgical rhythm, in fact, it is Good Friday and Holy Saturday. This significant difference between the monastic services of Holy Week—not celebrated in parishes—and the two services on Thursday and Friday evenings is also reflected in the way worship books are heavily worn: the pages containing the liturgical hours or the Compline or the first liturgical days of Holy Week are rarely opened or just leafed through, while the pages containing the last days of the week are very used, showing that they have been and are heavily employed every liturgical year.

3.4. Holy Friday and Saturday—Ta Enkomia

Without going into details too technical for the limits of this article, I would like to illustrate the concrete situation of the liturgical texts on Friday evenings (Holy Saturday Matins), in which one of the most beloved Orthodox Christian services is celebrated, namely the Lamentations at the Grave, or

ta Enkomia. The

Enkomia is a song of praise and at the same time of mourning at the tomb of our Lord Jesus Christ. A poetic creation whose origins are still unclear, but it appears in the Triodion manuscripts only in the 14th century. It will remain an integral part of the Triodion with the inclusion of these stanzas in the first printed edition of the Triodion of Venice 1522 (

Cernătescu and Barbu-Bucur 2021, p. 35). The

Enkomia contains 185 stanzas divided into three

stasis/chapters, interspersed with verses from Psalm 118 LXX, an older element in the Great Saturday service, present, in fact, in every funeral service in the Byzantine rite. Each stanza of the

Enkomia has a very simple and catchy rhythm, pleasant and easy to chant with the whole congregation. The melody changes at each of the three parts, but it should be noted that these liturgical moments are the ones in which faithful people participate most actively in congregational chanting in a liturgical year. I speak here of the impact on the listeners/participants of the service because the

Enkomia have metaphorical and emotional language that invites the listener to participate in the drama of lamentation of Mary, the Theotokos, and the close disciples at the burial of Jesus.

6The

Enkomia contains some of the harshest invective against the Jews and, as usual, the anti-Jewish stanzas appear towards the end of each

stasis. The reality of the 20th century, especially after the Second World War, has led to significant changes in this embarrassing situation: Many editions of the

Enkomia translated into languages other than the original Greek avoid the harshest stanzas against

the Jews. There are two reasons that have led to this excision, and both are mutually supportive. The first is simply the length of this service and the need to shorten it in a parochial context, especially in the diaspora, and the second is the growing sensitivity to the theme of anti-Judaism since the second half of the 20th century. To demonstrate this, I compared the standard Greek edition of the

Enkomia with a pre-World War II Romanian translation

7 and then compared these versions with a Greek version in use in the US, and the older Romanian version with the newer 1970 version of the Triodion and a more recent version of a Greek Catholic context

8.

The lived reality of Byzantine worship is that, in the old translations, the version of the Enkomia attempts to render the text of the Enkomia verbatim, sometimes making the translation musically impossible. With the passing of time, attempts to adapt the text to the rousing melody of the Enkomia are observed, until the 1970s, when the Romanian version discards some of the overly violent stanzas against the Jews and slightly transforms others during the translation process.

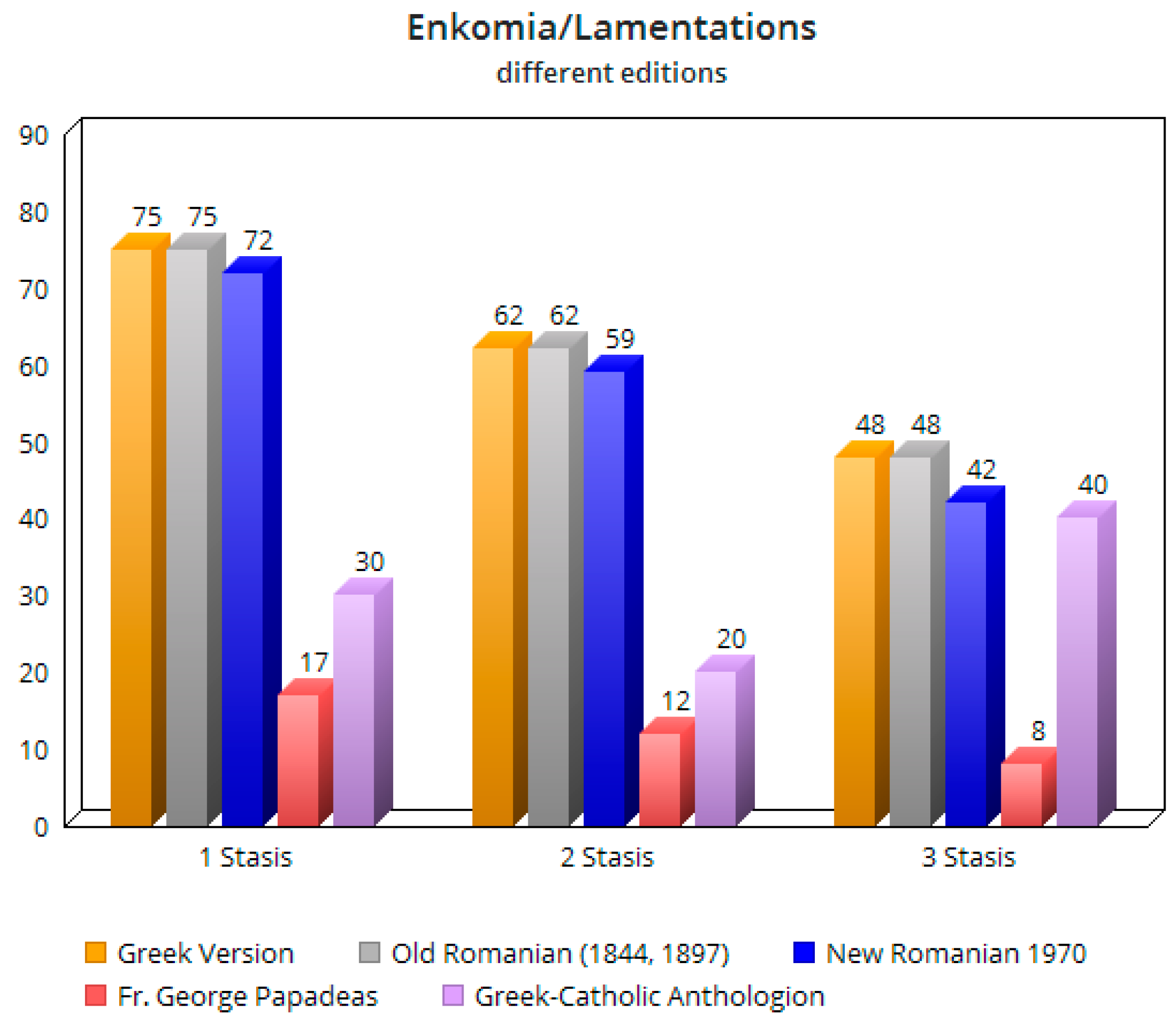

The result is that the 1970 version of the

Enkomia is three stanzas short in the first and second states, and six stanzas are missing from the third state, not counting the slightly altered ones (

Figure 6). The fact that the most violent stanzas are missing shows that the main reason for this absence in the 1970 version is precisely the sensitivity to these anti-Jewish texts and not necessarily the length of the service, leading some to speak of a certain “tacit reform” (

Ioniță 2014, p. 160). The author uses the term “tacit” because the absence of those stanzas and the modification of others through translation was nowhere officially announced, nor even mentioned in the preface to that edition of the Triodion, which later led to dissatisfaction and, of course, a return to the “correct” and “complete” version of the

Enkomia after the communist period, while some theologians consider the shortened version of the

Enkomia still appropriate for liturgical practice, although they admit that it would have been better to have been announced by the Church authorities at that time (

Mihăilă 2019, p. 253)

9.

In the case of modern Greek editions, such as that of Papadeas in the US and the case of the practice reflected in the Greek Catholic

Anthologion, it seems that the reason for the necessity of shortening the service is prevalent. Out of 75 stanzas in Papadeas, only 17, or 12, remain in the first two chapters of the

Enkomia, and out of the last chapter of 48 stanzas, only 8 stanzas remain. In the

Anthologhion, we have 30 stanzas and 20, respectively, from the first two parts of the

Enkomia and, unexpectedly, many in the third stasis, i.e., 40 out of 48 (

Figure 6). But in all these cases, the problematic anti-Jewish stanzas are missing, which shows that in addition to the shortening of the service, an important reason for the missing of those stanzas was the need to overshadow the anti-Jewish texts.

4. Analysis

While I have looked at these hymns from a quantitative point of view and have not gone into their content, I will now analyse the content of some suggestive examples from the liturgical period of the Triodion. Having seen how many hymns enter the discussion of Byzantine liturgical anti-Judaism, I now want to answer the following question: What are these hymns saying?

A pertinent observation already pointed out by several authors is that the Jews are condemned in a general way, as a whole people, together with Judea and the Synagogue, without any distinction—as present in the canonical Gospels—between the religious authorities who were in constant conflict with Jesus, and the people, who the evangelists often say loved Jesus or considered him a prophet. This imperative repetition of the name of the Jews, obsessively placed in parallel with Judas, especially on Maundy Thursday (46 occurrences), makes the Jews the sole actors responsible for the whole misfortune described in the Gospels.

The most used adjective for

the Jews is “the lawless ones”—in Greek

paránomos (παράνομος). And not only

the Jews, but the whole people (Λαός) are

paránomos, the Sanhedrin is

paránomos, Judah is

paránomos, all Jewish men are

paránomos, and the Synagogue is

paránomos, so much so that this term draws a red thread running through almost all references to

Jews. Of course,

the Jews are often called “unbelieving and adulterous”, and even if

paránomos is not a particularly harsh invective, the fact that this term links Judah,

the Jews, the Jewish people, the Sanhedrin, and the Synagogue and makes all realities one, repeating it insistently, certainly had and continues to have a negative impact on the understanding of the biblical texts and hijacks the original meaning of these texts to a biased anti-Jewish one (

Roddy 2010). In addition, I must stress that the role of the Romans, or rather all humanity, in the crucifixion of the Saviour is silenced.

4.1. Supersessionism

A recurring and problematic theme, yet undiscussed, new, and challenging for the Orthodox theological context is the replacement theology, or supersessionism. The liturgical texts of the Triodion, especially in Passion Week, express very clearly the idea that the Church was replacing Israel, that the Church has been called to take its place, and that Israel no longer has any reason to exist. And the Church, called in the hymnography “the new Israel” (νέος Ισραήλ), is the Church among the Gentiles, not some Judeo-Christian community:

“Christ has established the Church, that he has redeemed from among the nations.”

10 “Let us also come today, all the

new Israel, the Church of the Gentiles, and let us cry with the Prophet Zechariah: Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion…”

11

The New Israel, which is necessarily the Church among the Gentiles, is not only new but also the beloved Israel. In biblical and prophetic terms of the relationship between bridegroom and bride, this new and beloved Israel is taken in marriage by the Lord, while the Synagogue is repudiated and condemned:

“He has found out every righteous way and given it to

Israel His beloved.”

12 “…O

unbelieving and adulterous generation of the Jews, draw near and look on Him whom Isaiah saw: He is come for our sakes in the flesh. See how He weds the New Zion, for she is chaste, and

rejects the Synagogue that is condemned…”

13

The repudiation of the Synagogue and condemnation of the Jews is a common motif in patristic literature, and several voices of contemporary Orthodox theologians have already spoken out against this attitude, calling for the texts to be corrected, although they are aware that this will not happen very quickly and that it requires a lengthy process and intense theological discussions, which have only just begun (

Seppälä 2019, p. 197).

4.2. Invectives

But beyond the theology of substitution or the adjectives insistently repeated by hymnographers against the Jews, the most problematic liturgical texts remain the harsh invective of Passion Week and beyond. A few brief examples speak for themselves:

“O bloodthirsty people, jealous and vengeful! May the very grave-clothes and the napkin put you to shame at Christ’s Resurrection.”

14 “What is the madness that seized you, O ye Jews? Why do ye disbelieve? How long will you wander in falsehood? Ye see the dead man leap up when Christ calls him, and do ye still disbelieve in Christ? Truly ye are all children of darkness.”

15

Above all these words, the accusation of deicide, which appears quite often in hymnography, must be mentioned. The Jewish people, as a whole, are described as “murderers of God” (θεοκτόνος

16), and the Jews all together are “murderers”, as we usually sing in the

Enkomia. For this, the hymnographers do not shy away from announcing the destruction of the “Hebrew people”—this time—as a reward for Christ’s crucifixion on the cross:

“Seeing Thee crucified, O Christ, the whole creation trembled. … For when Thou was raised up today, the

people of the Hebrews was destroyed.”

17

The clearest position from an Orthodox theologian on such hymns is that of Andrew Louth, but it must be stressed that it is not part of a deeper and more complex concern with the subject, but rather a marginal note. However, from our perspective, his words are very valuable:

“We need to recover the deep affinity that exists between Christianity and Judaism, and perhaps also have courage to revise some of our texts that are blatantly supersessionist and anti-Judaic, especially during Great and Holy Week.”

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

A quantitative overview of the hymnographic texts in the Triodion can effectively help establish a concrete and reliable basis for the continuation of this delicate discussion of Byzantine liturgical anti-Judaism in the context of the Jewish–Christian dialogue. The upshot is—perhaps surprisingly to most readers—that, in fact, Byzantine liturgical hymnody cannot be labelled as anti-Jewish. The graphs presented in this article show that anti-Jewish elements can be found in about 4% of the total troparia included in the Triodion. This percentage gradually increases to double the amount as we approach the liturgical moments related to the Passion, Crucifixion, and Death on the Cross of Jesus. Despite these figures, most liturgical hymns are not touched by any anti-Jewish rhetoric, and indeed it can be said that hymnography and the Byzantine liturgy in general carry a considerable Jewish heritage, as some Orthodox authors mentioned here have recently pointed out. For us, it is relevant that the same Byzantine hymnographer, such as St. Andrew of Crete, for example, may use harsh accusations of deicide at times in some troparia, but in his remarkable composition called the Great Canon, specific to the Lenten period, he leaves no room for such expressions against the Jews. On the contrary, as a connoisseur of the Jewish Scriptures, he makes exemplary use of many personalities from the Jewish tradition to serve as models for his Christian audience.

Another important observation is that anti-Jewish troparia, or anti-Jewish elements in some troparia, always appear towards the end of a liturgical chapter. Whether a part of the Enkomia, an ode of a canon, or a group of stichera, the anti-Jewish voice is not the one that predominates, nor the one that is heard first. However, the fact that most of the harsh and unacceptable words against the Jews are concentrated on liturgical days that are highly frequented by the faithful, such as Holy Friday and Saturday, is troubling and problematic, because it is on those days that the more tainted texts will be heard by the majority of the faithful. If we add the performance perspective here, it is worth bearing in mind that, of the few anti-Jewish texts that exist in the Triodion compared to the entire hymnographic corpus, some serious accusations remain simply written but never read and others eventually read but never sung. How these texts are performed is extremely important and relevant, and studies of this phenomenon have yet to be written.

With these objective data on the small percentage of questionable texts from the point of view of the Jewish–Orthodox Christian dialogue, we can offer a positive conclusion considering each community. For Christians, we can show that there are very few texts that need to be modified or excluded. If those texts were indeed excluded or modified, Orthodox services would lose none of their richness and beauty. Indeed, they might even be freed from some of the discordant notes of invective totally inappropriate to the content and purpose of the liturgical services around the great Feast of Resurrection. The liturgical practice of recent decades has already shown that this can be done informally, without official decisions. What is worth doing is rediscovering this biblical treasure and our “affinities” to the Jewish tradition, as Andrew Louth rightly suggests.

For the Jews involved in the dialogue, we can argue that the anti-Jewish texts are so few compared to the total number of liturgical texts that it cannot be said that the Byzantine or Orthodox liturgy is inherently anti-Jewish. Recent changes in parishes and even in liturgical books show that Orthodox Christian believers are willing and eager to avoid such hymns in the concretely lived liturgy. At the official level, the Orthodox Church is not only reluctant and resistant to this topic, but also in general, the Orthodox Church has difficulty finding a common denominator in decisions involving all local churches, and the proposal to defer such a decision to a Pan-Orthodox Synod is utopian. Comparing the Orthodox Church with the Catholic Church and the progress made in the Catholic environment since Nostra aetate is an unproductive approach to this dialogue.

More practically, related to the content of these texts discussed here, we see that the quantitative survey and analysis of the texts crystallised at least three categories, which could be an important step towards the establishment of criteria for distinguishing liturgical texts. The first category revolves around the name Jews, with various epithets and adjectives, a name that describes a collective and compact reality, directly related to Judah, the Synagogue, Judea, the Sanhedrin, and the Jewish people. The Jews become in Byzantine hymnography the otherness par excellence, and the liturgical texts here certainly go a step further than the biblical texts, pushing the interpretation, and inevitably the reception, towards the idea that the entire Jewish people are guilty and damned for the crucifixion of Jesus.

The second category of liturgical texts has at its core the powerful idea of the replacement of Israel by the Church, and more specifically by the “Church among the Gentiles”. We have seen from the examples selected above that the hymnographers do not stop at the Jew–Gentile polarity, which is present throughout the text of Scriptures but go further by triumphantly proclaiming the victory of the Gentiles over the Synagogue, wishing to “repudiate” it, and reserving the title of “beloved Israel” only for the Church among the Gentiles. The third category of hymns, under the label of invective, clearly announces the “destruction of the Jewish people”, calling the people as a whole “murderers”, “unbelievers”, “adulterers”, and “bloodthirsty”.

My proposal is that at least the last category of texts can be excluded from the Triodion, while the hymns of the second and first categories can possibly be modified by translation. The concrete reality in the liturgical practice of the Byzantine rite in Europe and the US—as I have exemplified with the help of the Enkomia—shows that there is already a sensitivity to this situation, and some reform has already occurred, either in the case of the revised Triodion of 1970 Romania or in the fact that Orthodox parishes in Eastern Europe or other regions have chosen to use shorter versions of the Enkomia, precisely omitting the problematic stanzas or transforming them by translating them into modern languages.

All this shows that, within the various Orthodox communities, there is already an awareness of the subject, but the deep and justified attachment to one’s own tradition, the reluctance to discuss such topics, and the fact that someone might be concerned about changing the liturgical corpus—almost canonised by its unchanged use for centuries—make this topic a difficult but an extremely necessary one. The need to continue this discussion stems from the need to look historically, critically, and contextually at Byzantine liturgical texts, which have not been discussed in recent centuries as society has transformed considerably. In addition, enough Orthodox voices have risen in recent years and stressed the need to address these issues, which shows an internal readiness for change. Of course, the small changes suggested here to liturgical texts are the responsibility of the Church’s forums, whereas the academic world is the space for the discussion and debate necessary prior to such a decision. Ideally, the two worlds, academic and ecclesiastical, should take each other into account and work together.