Religion and Strategic Disaster Risk Management in the Better Normal: The Case of the Pagoda sa Wawa Fluvial Festival in Bocaue, Bulacan, Philippines

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Vulnerable Philippines

1.2. Objectives

1.3. Significance of the Study

2. Methodology

3. Review of Related Literature

3.1. Disaster and Catastrophe

3.2. Spanish Colonial Churches as Evacuation Centers

3.3. Spanish Colonial Belfries as Watchtowers

3.4. Typhoon Yolanda, Taal Volcano Eruption and the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.5. Risk Reduction Management in the Philippines

4. Context

4.1. The Philippines as a Place of Happiness

4.2. Fluvial Festivals in the Philippines

4.3. Incidents Related to Religious Festivities in the New Normal

4.4. Holy Week Tragedy 2023

4.5. Collective Spiritual Longings

4.6. Religious Rituals, Safety Awareness and Disaster Preparedness

5. Content

5.1. Sanctity of Life and Human Dignity

5.2. Application of the Consistent Ethic of Life Principle

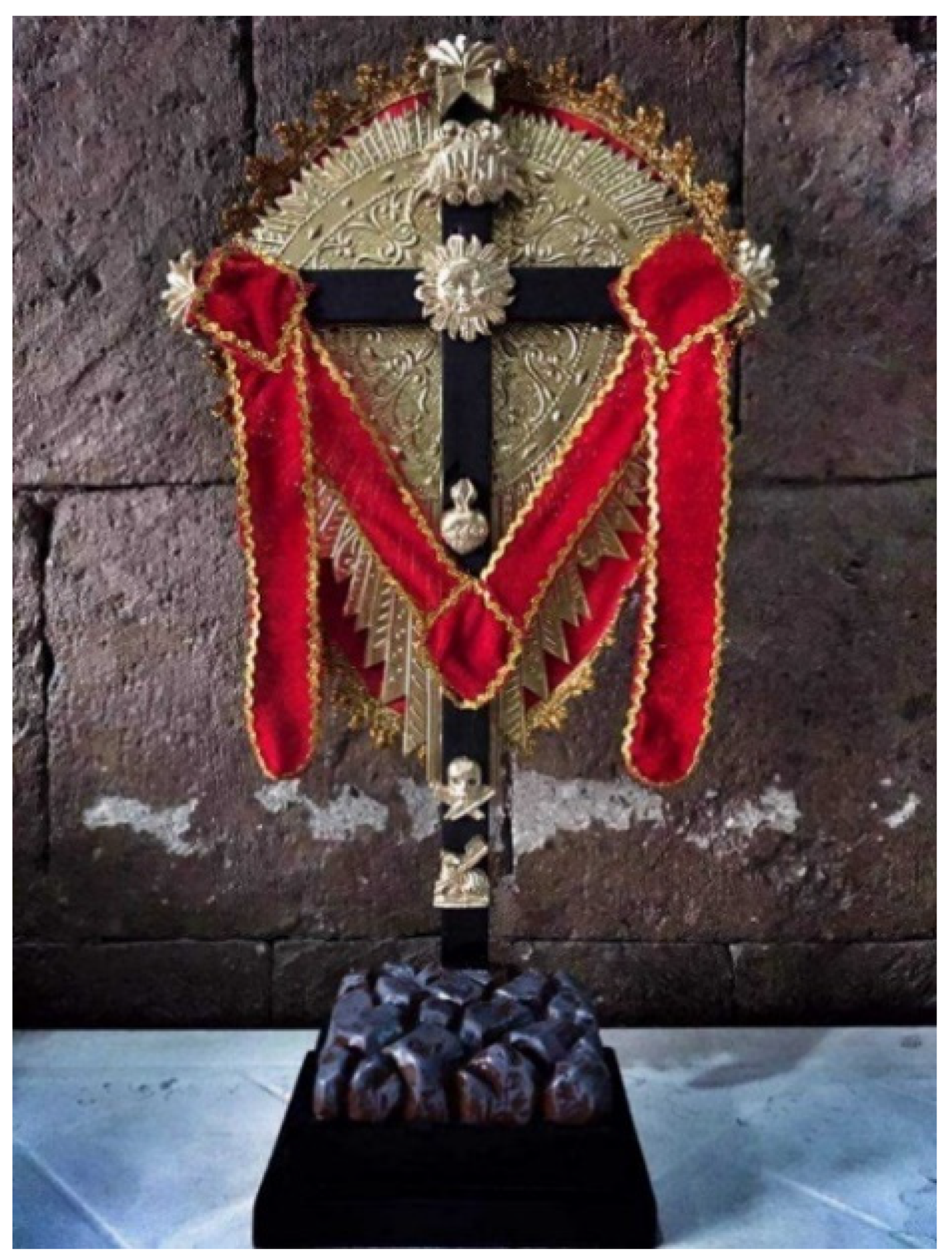

5.3. Pagoda sa Wawa Fluvial Festival in Bocaue, Bulacan

5.4. Navigating Lessons While Crossing the River Styx

5.5. Resiliency and Resurrection

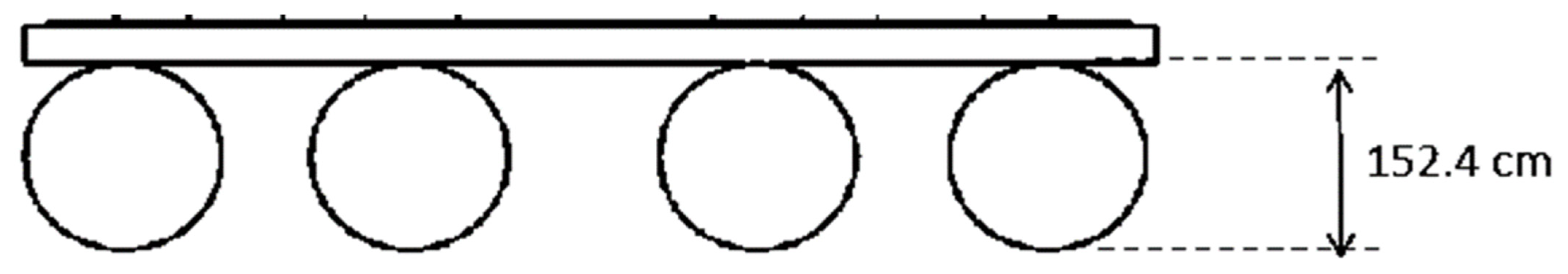

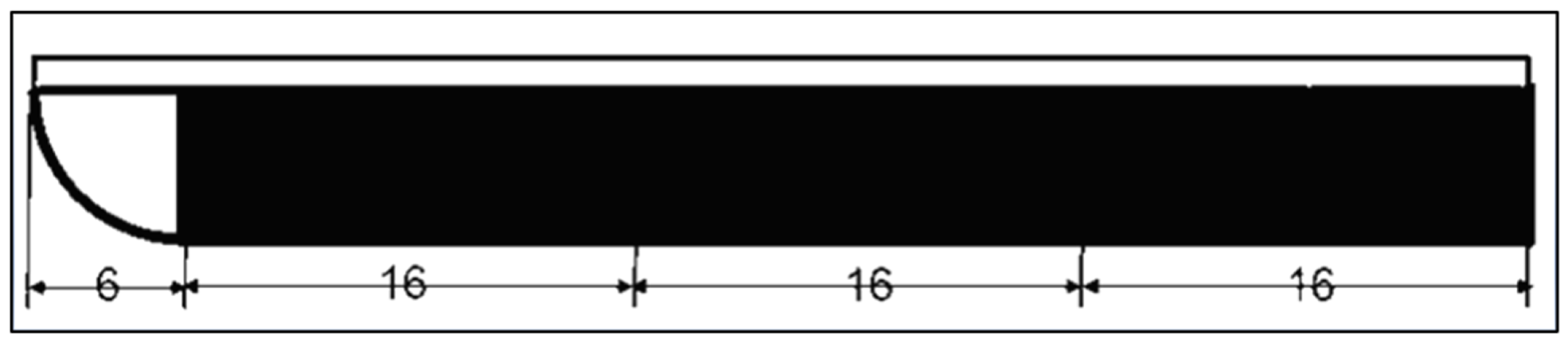

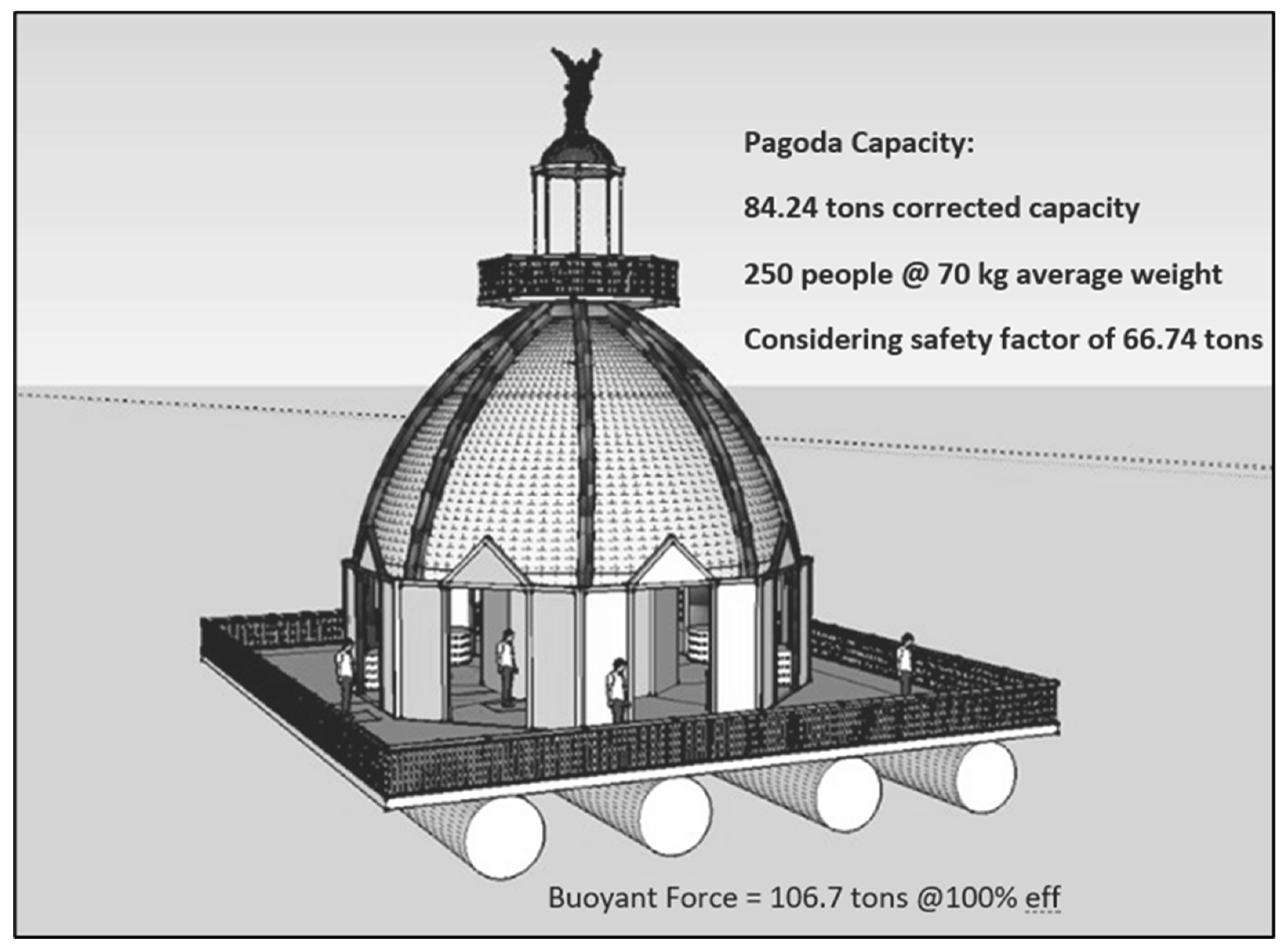

5.6. Pagoda sa Wawa’s Elements of Risk-Reduction Management and Disaster Preparedness in the New Normal

6. Challenges

6.1. Demystifying the Myth

6.2. From Reactive to Proactive Church

6.3. Cultivating a Culture of Safety in the Philippines

6.4. Continue the Save Bocaue River Program

7. (Re)commendations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ACAPS. 2014. Secondary Data Review, Philippines Typhoon Yolanda. Assessment Capacities Project. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/philippines/secondary-data-review-philippines-typhoon-yolanda-january-2014 (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Agence France-Presse. 2023. 72 Dead from Drowning after Holy Week Season: Police. Philstar. Available online: https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/04/10/2257839/72-dead-drowning-after-holy-week-season-police (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Bankoff, Gregory. 2007. Living with Risk; Coping with Disasters Hazard as a Frequent Life Experience in the Philippines. Education about Asia 12: 26–29. Available online: https://www.asianstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/living-with-risk-coping-with-disasters-hazard-as-a-frequent-life-experience-in-the-philippines.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Bankoff, Gregory. 2012. Storm over San Isidro: “Civic Community” and Disaster Risk Reduction in the Nineteenth Century Philippines. Journal of Historical Sociology 25: 331–51. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/9969659/Storm_over_San_Isidro_Civic_Community_and_Disaster_Risk_Reduction_in_the_Nineteenth_Century_Philippines (accessed on 27 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Basa-Iñigo, Liezle. 2022. Death Toll in Pampanga River Parade Accident Climbs to Three. Manila Bulletin. Available online: https://mb.com.ph/2022/06/29/death-toll-in-pampanga-river-parade-accident-climbs-to-three-nine-others-injured/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Bernardin, Joseph Cardinal. 1989. Deciding for Life. Message for Respect Life Sunday. Available online: https://boatagainstthecurrent.blogspot.com/2012/02/quote-of-day-cardinal-bernardin-on.html (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Berto. 2023. Apung Iru Fluvial Festival. The Philippines Today, Yesterday, and Tomorrow. Available online: https://thephilippinestoday.com/apung-iru-fluvial-festival/#google_vignette (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Bocaue. n.d. Encyclopedia, Science News & Research Reviews. Available online: https://academic-accelerator.com/encyclopedia/bocaue (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Bollettino, Vincenzo, Tilly Alcayna, Krish Enriquez, and Patrick Vinck. 2018. Perceptions of Disaster Resilience and Preparedness in the Philippines. Harvard Humanitarian Initiative. Available online: https://hhi.harvard.edu/publications/perceptions-disaster-resilience-and-preparedness-philippines (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Catechism of the Catholic Church. n.d. Available online: http://www.scborromeo.org/ccc/p3s2c2a5.htm (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Catholic Social Teaching. n.d. Office for Social Justice of St. Paul and Minneapolis. Available online: http://www.osjspm.org/major_themes.aspx (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Col, Jeanne-Marie. 2007. Managing disasters: The Role of Local Government. Public Administration Review 67: 114–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church. n.d. Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/justpeace/documents/rc_pc_justpeace_doc_20060526_compendio-dott-soc_en.html (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Eballo, Arvin. 2018. Contextualizing Laudato Si’ through People’s Organization Engagement: A Kalawakan Experience. Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics 8: 1–29. Available online: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/solidarity/vol8/iss1/2/ (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Eballo, Arvin. 2020. From Devotion to Action: Practicing Holiness amidst the COVID-19 Crisis in the Philippines. The Antoninus Journal, 1–3. Available online: https://theantoninus.com.ph/archives/37/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Eballo, Arvin. 2022. A Word from the Guest Editor. Politics and Religion Journal 16: 172–74. Available online: https://www.politicsandreligionjournal.com/index.php/prj/article/view/6 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Gabriel, Arphie. 2014. Pagoda in Bocaue: Sailing over Lessons in the River of Styx. The Pragmatic Notion. Available online: https://arphiegabriel.weebly.com/news-feature-blogs/pagoda-in-bocaue-sailing-over-lessons-in-the-river-of-styx (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Guha-Sapir, Debarati, Regina Below, and Pasacline Hoyois. 2015. EM-DAT: International Disaster Database. Brussels: Universitécatholique de Louvain—CRED. Available online: http://www.emdat.be/ (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Malabanan, James. 2017. The Resilient Devotion and Tradition of the Holy Cross of Wawa. Pintakasi: Chronicles on Filipino Popular Piety and Ecclesiastical History. Available online: https://pintakasi1521.blogspot.com/2017/09/the-resilient-devotion-and-tradition-of.html (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Malabonga, Royce Lyssah. 2018. Peñafrancia, the 300-year-old Fluvial Procession Festival in the Philippines. ICHCAP e-Newsletter. Available online: https://www.unesco-ichcap.org/penafrancia-the-300-year-old-fluvial-procession-festival-in-the-philippines/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Mocon-Ciriaco, Claudeth. 2017. Taguig City Celebrates Annual Fluvial Festival. Business Mirror. Available online: https://businessmirror.com.ph/2017/07/26/taguig-city-celebrates-annual-fluvial-festival/ (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 1999. Enhancing the Quality and Credibility of Qualitative Analysis. HSR: Health Services Research 34, Pt 2: 1189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, William. 2016. Places for Happiness: Community, Self, and Performance in the Philippines. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Philatlas.com. n.d. Available online: https://www.philatlas.com/luzon/r03/bulacan/bocaue.html (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Pope John Paul II. 1995. Evangelium Vitae. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_25031995_evangelium-vitae.html (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Ranada, Pia. 2015. When Taal Volcano Erupted for 6 Months. Rappler. Available online: https://www.rappler.com/environment/disasters/93809-taal-volcano-1754-eruption/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Reyes-Estrope, Carmela. 2016. 23 Years after Pagoda Tragedy, Catholics Rediscover Faith. Available online: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/792997/23-years-after-pagoda-tragedy-catholics-rediscover-faith (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Reyes-Estrope, Carmela. 2019. Bocaue Folk to Revive Dying River as They Recall Pagoda Tragedy. Available online: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1137531/bocaue-folk-to-revive-dying-river-as-they-recall-pagoda-tragedy (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Reyes-Estrope, Carmela. 2023. Safety First: Bulacan Town Revisits ‘Painful’ Lessons from Pagoda Tragedy. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Available online: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1797398/bulacan-town-revisits-painful-lessons-from-pagoda-tragedy (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Samuels, Fiona, Rena Geibel, and Fiona Perry. 2010. Collaboration between Faith-Based Communities and Humanitarian Actors When Responding to HIV in Emergencies. ODI Project Briefing 41. London: Overseas Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- UNISDR. 2015. Making Development Sustainable: The Future of Disaster Risk Management. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-assessment-report-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-gar15-making-development?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiA1rSsBhDHARIsANB4EJatClf9lcz3nt9uDbhrcr3kZj0LWHg9HfDteMrJbpoxlQSMi8kHIrsaAiUOEALw_wcB (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Women’s Quill. 2013. Available online: https://womensquill.wordpress.com/2013/09/07/the-pagoda-tragedy-of-bocaue-bulacan/ (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Woolcock, Michael, and Deepa Narayan. 2000. Social Capital: Implications for Development Theory. Research, and Policy. World Bank Research Observer 15: 225–49. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/961231468336675195/pdf/766490JRN0WBRO00Box374385B00PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2023). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eballo, A.D.; Eballo, M.B. Religion and Strategic Disaster Risk Management in the Better Normal: The Case of the Pagoda sa Wawa Fluvial Festival in Bocaue, Bulacan, Philippines. Religions 2024, 15, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020223

Eballo AD, Eballo MB. Religion and Strategic Disaster Risk Management in the Better Normal: The Case of the Pagoda sa Wawa Fluvial Festival in Bocaue, Bulacan, Philippines. Religions. 2024; 15(2):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020223

Chicago/Turabian StyleEballo, Arvin Dineros, and Mia Borromeo Eballo. 2024. "Religion and Strategic Disaster Risk Management in the Better Normal: The Case of the Pagoda sa Wawa Fluvial Festival in Bocaue, Bulacan, Philippines" Religions 15, no. 2: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020223

APA StyleEballo, A. D., & Eballo, M. B. (2024). Religion and Strategic Disaster Risk Management in the Better Normal: The Case of the Pagoda sa Wawa Fluvial Festival in Bocaue, Bulacan, Philippines. Religions, 15(2), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020223