Cao’an in the Ancestral World: Contemporary Manichaeism-Related Belief and Familial Ethics in Southeastern China

Abstract

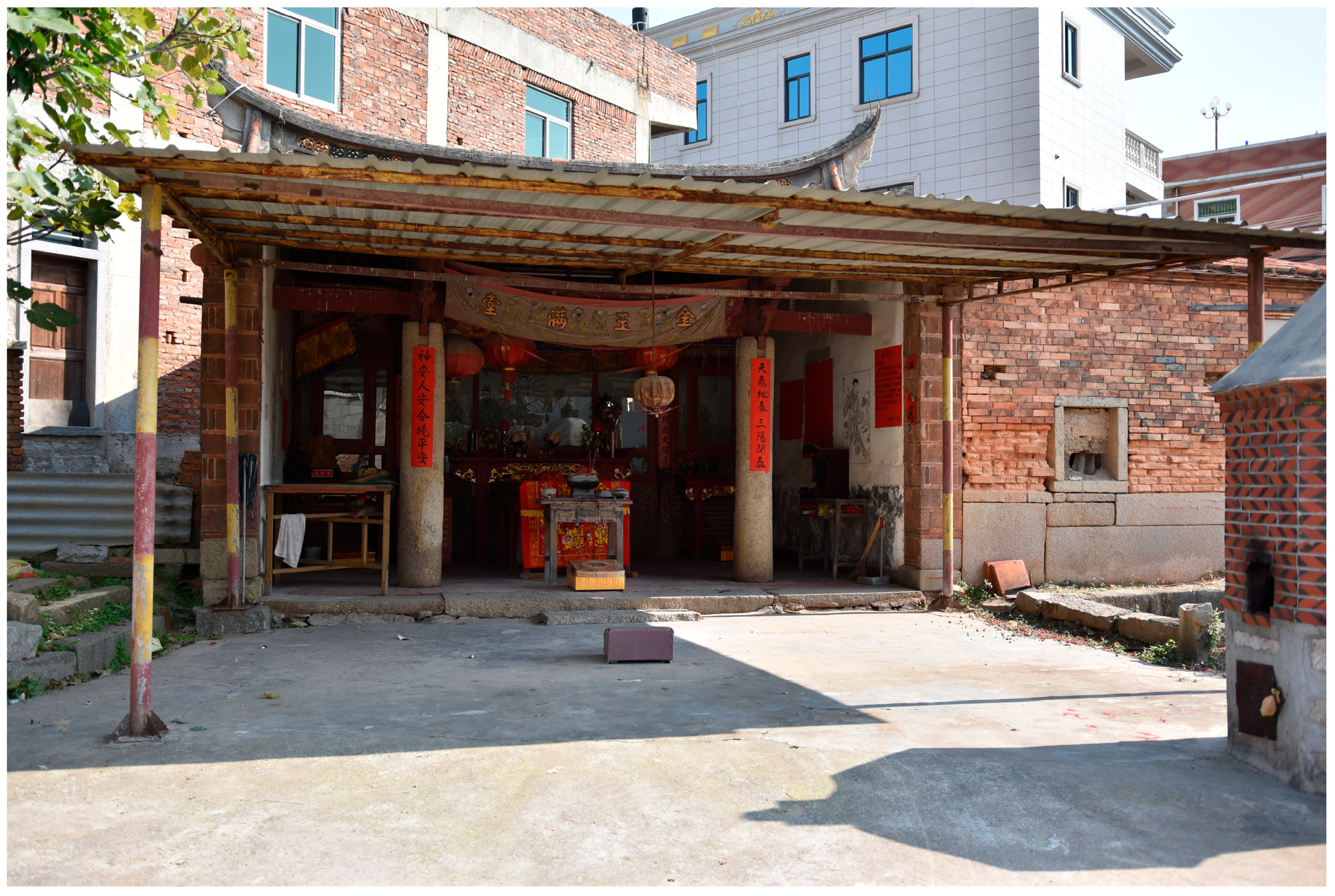

1. Manichaeism-Related Beliefs in Sunei Village: History and Reality

2. Generation of Manichaeism Stories: Genealogy, Narratives, and Inscriptions

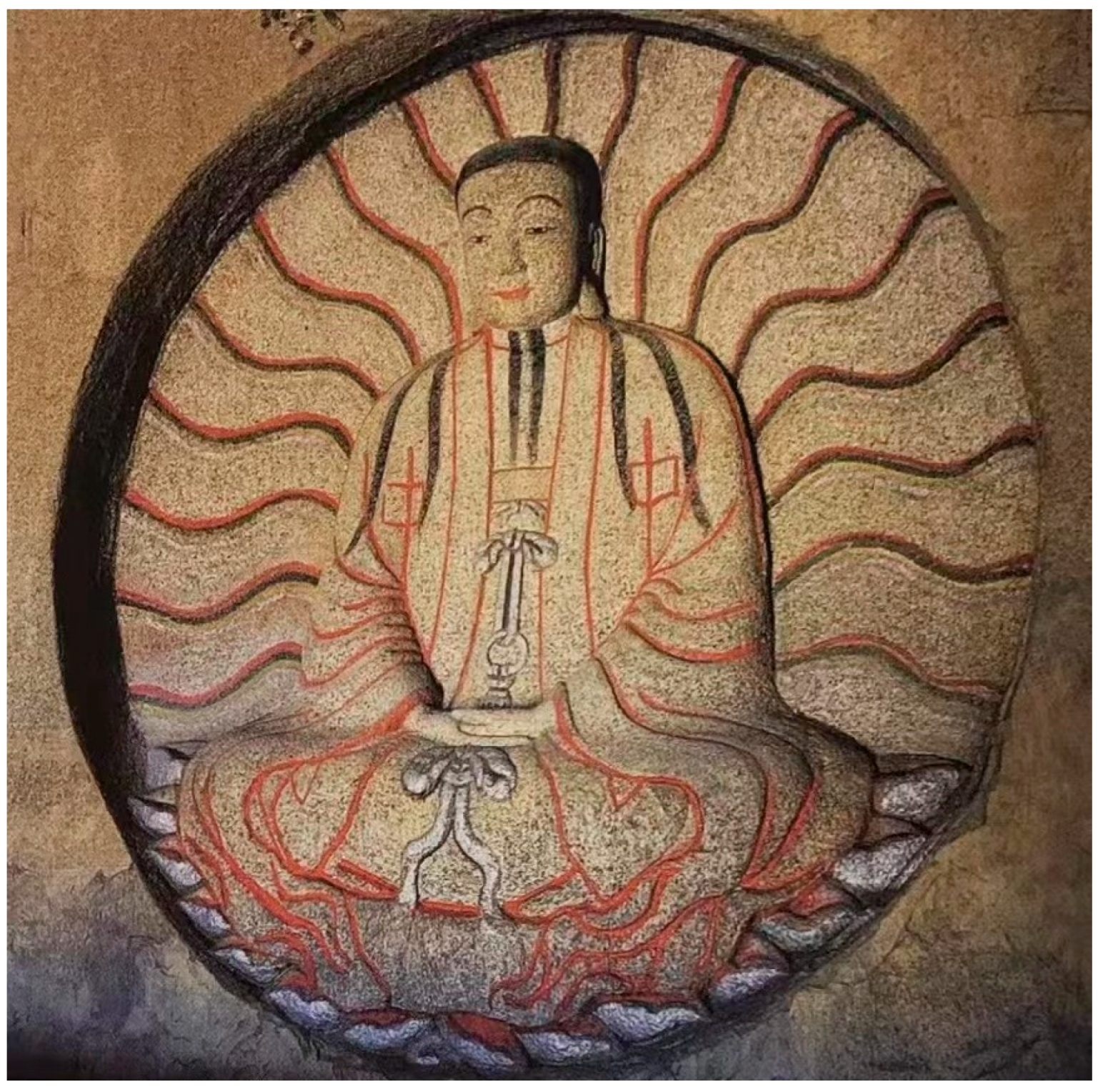

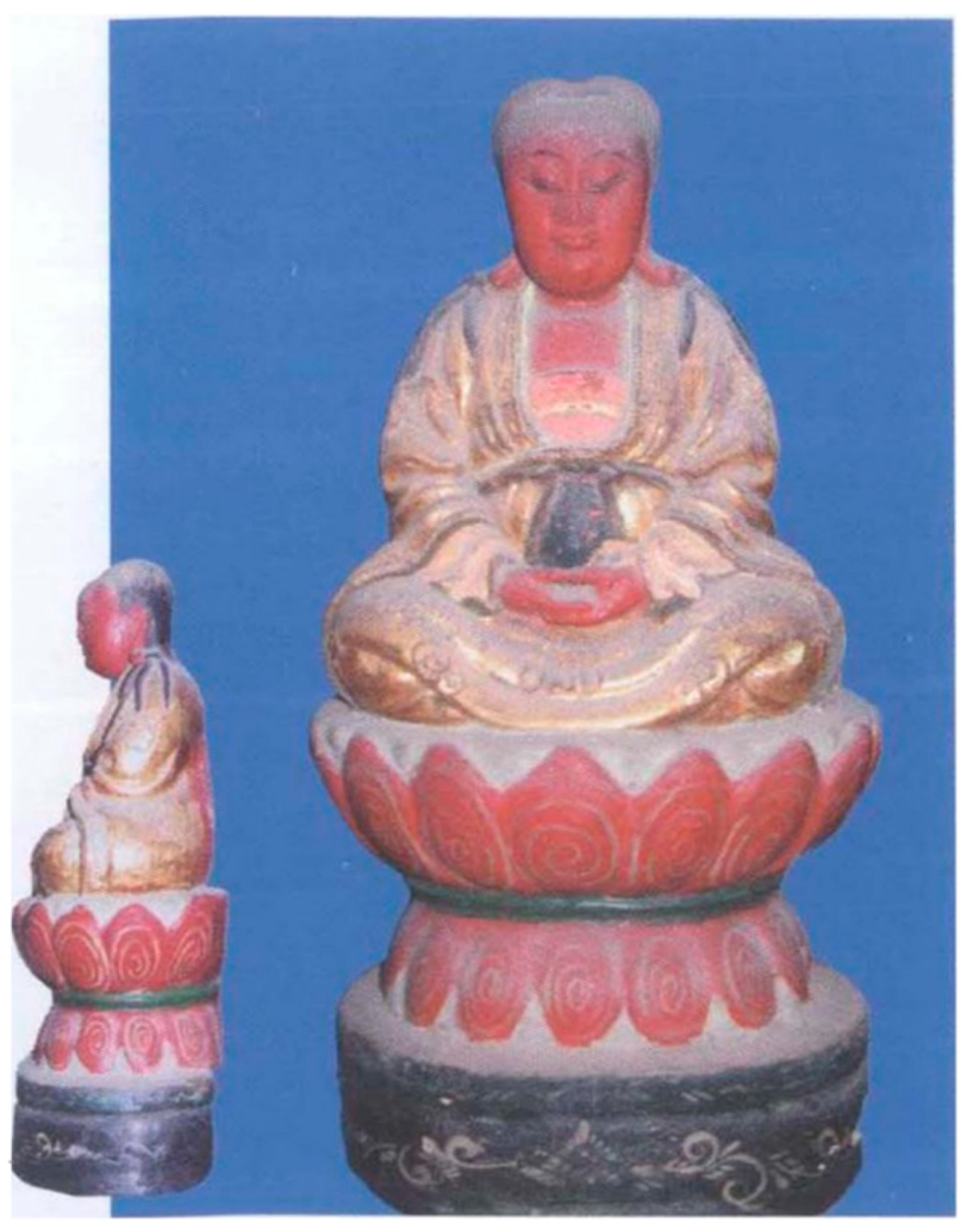

2.1. Origin Stories of the “Mani the Buddha of Light” Statue

2.2. Settlement Story of the Zeng Clan Ancestors

2.3. Stories of Ancestors as Manichaean Followers

3. Manichaeism-Related Narratives and Family Ethics

3.1. Ancestors as Manichaean Followers, Memory, and Family Ethics

3.2. Mani Buddha Worship and Familial Ethics

- Adoption Contract

- Adopted Parties: Chen Qi, married to Zeng E from An Village, Hongzhai, Jinjiang, Quanzhou. On the 24th day of the 10th lunar month in 2018, a son named Chen Wen was born. The couple has decided to give their beloved son to Mani Buddha of Light as a foster child.

- We pray for the support of his foundation, disaster-free years, celebrations in all seasons, well-being during the eight solar terms, and growing up healthy and strong. Upon reaching adulthood, he shall offer fruits, flowers, and money as tokens of gratitude to the deity. Fearing that words alone are not substantial; this written contract is hereby made as proof.

| Adopted Parties: Chen Qi; Zeng E |

| Respectfully established on the 3rd day of the 12th lunar month in 2021. |

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For an overview of Manichaean canonical literature, history, doctrines, and important studies, see: Lieu (1985, 1998, pp. 1–58), Lin (1987, pp. 1–11), Gardner and Lieu (2004, pp. 1–45), Tardieu (2008), Baker-Brian (2011), and Yao et al. (2011, pp. 161–305). For a retrospective review of the history of Chinese Manichaeism studies, see: Wang (1992, pp. 2–58). |

| 2 | On the activities and findings of the expeditions which discovered these documents in the early 20th century, see: Lieu (1998, pp. 2–12). For a brief summary of the studies based on them, see: Gardner and Lieu (2004, pp. 25–35), and Wang (2012, pp. 1–14). |

| 3 | Lin Wushu distinguishes between “Mingjiao sites” (fixed religious structures left by Mingjiao adherents, like Cao’an), “Mingjiao artifacts” (religious and daily items of Mingjiao followers), and “Mingjiao traces” (physical and non-physical items with Mingjiao elements). See, Lin (2014, pp. 337–41). |

| 4 | The inscriptions read: “Yao Xingzu of Luoshan Jing, Xinghua Lu, devoutly constructed a stone chamber. Prayers for his father Yao Rujian Sanshisan Yan, his mother Guo Wujiu Tairu, stepmother Huang Shisanniang, and brother Yao Yuejian Sixue, and hopes that they could live in Buddha’s realm generation after generation. (興化路羅山境姚興祖,奉捨石室一完。祈薦先君正卿姚汝堅三十三宴,妣郭氏五九太孺,繼母黃十三娘,先兄姚月澗四學世生界者). Chen Zhenze Lisi, a Xiedian Shi believer, joyfully donated the sacred statue of the Master, praying for the rebirth of his parents in Buddha’s realm”. (謝店市信士陳真澤立寺,喜捨本師聖像,祈薦考妣早生佛地者. Wu 2005, p. 443) |

| 5 | Lieu (2012b, p. 72). The same paper also collectes a serires other photos of Cao’an and Manichaeism-related remains of Sunei village. |

| 6 | For the story of Wu Wenliang’s discovery of Cao’an, see: Lieu (2012a, pp. 15–17). Goodrich first reported this discovery to the West in 1947 (Goodrich 1957, p. 64). Bryder’s personal visit to Cao’an in 1986 and his corresponding papers became the first major study of Cao’an in the English-speaking world (Bryder 1988). |

| 7 | However, during my fieldwork, I found no evidence of local people knowing or using this incantation. |

| 8 | In the 1980s, when Jinjiang was still a remote area, it was linked with the “international” community. The local government consciously utilized Cao’an as a cultural capital, taking advantage of the “traditional culture” and “Silk Road” trends to promote Manichaeism and Cao’an. Cao’an has been positioned as Jinjiang’s “shining business card”, attracting substantial economic resources. In 1987, the first International Manichaeism Symposium used the Cao’an Mani statue as its symbol. In 1991, a scientific mission of the UNESCO silk roads programme visited Cao’an. In 1996, Cao’an was upgraded to a national cultural preservation site. In 2008, its management was transferred from Sunei village to Jinjiang City. In 2010, the Jinjiang City government developed the “Cao’an Park Project”, aiming to turn Cao’an into a 3A tourist attraction and a patriotic education base. For this purpose, Sunei village underwent a major demolition to create the “Cao’an Cultural and Tourism District”. |

| 9 | The names of the villagers today (i.e., Zeng Kang, Chen Qi, Zeng E, Chen Wen, Mrs. Li, Zeng Zhang, and Zeng Xi) are aliases. |

| 10 | Translated by Lieu (2015, p. 137), adapted. |

| 11 | Wang Yuanyuan doubts the credibility of this record, arguing that the inscription on the Cao’an statue confirms its construction during the Yuan Dynasty (Wang 2009, p. 108). |

| 12 |

References

- Assmann, Jan. 1992. Das kulturelle Gedächtnis: Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in Frühen Hochkulturen. München : Verlag C. H. Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Brian, Nicholas J. 2011. Manichaeism: An Ancient Faith Rediscovered. London and New York: T&T Clark International. [Google Scholar]

- Bryder, Peter. 1988. … Where the Faint Traces of Manichaeism Disappear. Altorientalische Forschungen 15: 201–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryder, Peter. 1991. 草庵Revisited. In Manichaica Selecta: Studies Presented to Professor Julien Ries on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday. Edited by Alois van Tongerloo and Søren Giversen. Manichaean Studies I. Louvain: IAMS–BCMS–CHR, pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Hongsheng 蔡鸿生. 1994. Tang-Song shidai moni jiao zai binhai diqu de bianyi 唐宋时代摩尼教在滨海地区的变异 (Variation of Manichaeism in the Coastal Region during the Period of Tang and Song Dynasties). Journal of Sun Yatsen University (Social Science Edition) 6: 113–7. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, Janet, and Stephen Hugh-Jones. 1995. About the House: Lévi-Strauss and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chavannes, Édouard, and Paul Pelliot. 1911. Un traité manichéen retrouvé en Chine. Journal Asiatique (dixième série) 18: 499–617. [Google Scholar]

- Chavannes, Édouard, and Paul Pelliot. 1913. Un traité manichéen retrouvé en Chine. Journal Asiatique (onziéme série) 1: 99–199, 261–394. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shoushi 陈守实. 1980. Nongmin yundong yu zongjiao 农民运动与宗教 (Peasant Movements and Religion). In Zhongguo nongmin zhanzhengshi luncong (di er ji) 中国农民战争史论丛 第二辑 (Chinese Peasant War History Studies). Zhengzhou: Henan People’s Publishing House, vol. 2, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yuan 陳垣. 1923. Moni jiao ru Zhongguo kao 摩尼教入中國考 (History of Manichaeism in China). Guoxue jikan國學季刊 (Journal of Sinological Studies) 1: 203–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Ding 方鼎. 1968. Jinjiang xianzhi晋江縣志(Jinjiang County Annals). Taipei: Cheng Wen Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Feuchtwang, Stephan. 1991. The Imperial Metaphor: Popular Religion in China. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Franzmann, Majella Maria, Iain Gardner, and Sam Lieu. 2005. A Living Mani Cult in the Twenty-first Century. Rivista di Storia e Letteratura Religiosa 5: vii–xi. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Iain, and Samuel NC Lieu. 2004. Manichaean Texts from the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, L. Carrington. 1957. Recent Discoveries at Zayton. Journal of the American Oriental Society 77: 161–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulácsi, Zsuzsanna. 2009. A Manichaean ‘Portrait of the Budda Jesus’: Identifying a Twelfth- or Thirteenth-century Chinese Painting from the Collection of Seiun-ji Zen Temple. Artibus Asiae 69: 91–145. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On Collective Memory. Translated by Lewis Coser. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Pengyu 何鵬毓. 1951. Beisong mo fangla de nongmin da qiyi 北宋末方臘的農民大起義 (The peasant uprising in Fangla during the late Northern Song Dynasty). Journal of Historical Science 史學月刊 8: 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- He, Qiaoyuan 何喬遠. 1994. Minshu 閩書 (Book of Fujian). Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- History Department Kaifeng Normal College 开封师范学院历史系. 1976. Zhongguo nongmin qiyi lingxiu xiaozhuan 中国农民起义领袖小传 (Biographies of Chinese Peasant Uprising Leaders: Fang La). Beijing: Beijing People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shichun 黄世春. 1985. Fujian Jinjiang Cao’an faxian ‘Mingjiao hui’ heiyou wuan 福建晋江草庵发现“明教会”黑釉碗(Mingjiao black-glazed bowls founded in Cao’an, Jinjiang, Fujian). Maritime History Studies 海交史研究 1: 73. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Jun. 1996. The Temple of Memories: History, Power and Morality in a Chinese Village. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kauz, Ralph. 2000. Der ‘Mo-ni-gong’ (摩尼宮)–ein zweiter erhaltener manichäischer Tempel in Fujian? In Studia Manichaica. IV. Internationaler Kongress zum Manichäismus, Berlin, Germany, 14–18 July 1997. Edited by Ronald Emmerick, Werner Sundermann and Peter Zieme. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, pp. 334–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kauz, Ralph. 2019. A Survey of Manichaean Temples in China’s Southeast. Orientierungen 31: 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kósa, Gábor. 2021. Mānī on the Margins: A Brief History of Manichaeism in Southeastern China. Locus: Revista de História 27: 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1963. Do Dual Organization Exist? In Structural Anthropology. Translated by Jacobson Claire, and Schoepf Brooke Grundfest. New York: Basic Books, pp. 132–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1982. The Way of the Masks. Translated by Modelski Sylvia. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1987. Anthropology and Myth: Lectures 1951–1982. Translated by Willis Roy. Oxford and New York: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Bincheng 李斌城. 1988. Zhongguo nongmin zhanzheng shi: Sui-Tang wudai shiguo juan 中国农民战争史: 隋唐五代十国卷 (Chinese Peasant War History: From Sui and Tang Dynasties to Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period). Beijing: People’ Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. 1985. Manichaeism in the Later Roman Empire and Medieval China: A Historical Survey. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. 1998. Manichaeism in Central Asia and China. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. 2012a. Wu Wenliang 吳文良 and the Discovery of Christian and Manichaean remains in Quanzhou. In Medieval Christian and Manichaean Remains from Quanzhou (Zayton). Edited by Samuel N. C. Lieu, Lance Eccles, Majella Franzmann, Iain Gardner and Ken Parry. Corpus Fontium Manichaeorum: Series Archaeologica et Iconographica II. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. 2012b. Manichaean Remains in Jinjiang 晋江. In Medieval Christian and Manichaean Remains from Quanzhou (Zayton). Edited by Samuel N. C. Lieu, Lance Eccles, Majella Franzmann, Iain Gardner and Ken Parry. Corpus Fontium Manichaeorum: Series Archaeologica et Iconographica II. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. 2013. Where the Faint Trances Grow Less Faint …—Recent Research on the Manichaean Shrine (Cao’an) in Fujian (S. China). In Gnostica et Manichaica: Restschrift für Aloïs van Tongerloo. Edited by Michael Knüppel and Luigi Cirillo. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lieu, Samuel N. C. 2015. The Diffusion, Persecution and Transformation of Manichaeism in Late Antiquity and pre-Modern China. In Conversion in Late Antiquity: Christianity, Islam, and Beyond. Edited by Arietta Papaconstantinou, Neil Mclynn and Daniel Schwartz. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 123–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu 林悟殊. 1987. Moni jiao jiqi dongjian 摩尼教及其東漸 (Manichaeism and Its Spread in the East). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu 林悟殊. 2005. Zhonggu san yijiao bianzheng 中古三夷教辨證 (Debate and Research on the Three Persian Religions: Manichaeism, Nestorianism, and Zoroastrianism in Mediaeval Times). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu 林悟殊. 2008. Quanzhou Jinjiang xin faxian moni jiao yiji bianxi 泉州晋江新发现摩尼教遗迹辨析 (Examinations on the Newly Discovered Manichaean Relics in Jinjiang, Quanzhou). In Jinjiang Cao’an yanjiu 晋江草庵研究 (A Study of Cao’an, Jinjiang). Nian, Liangtu 粘良图. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, pp. 165–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu 林悟殊. 2014. Moni jiao huahua bushuo摩尼教華化補說 (An Expanded Discussion of the Sinicization of Manichaeism). Lanzhou: Lanzhou University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Yunfeng 卢云峰. 2010. Bianqian shehui zhong de zongjiao zengzhang 变迁社会中的宗教增长 (Social Transition and Religious Growth). Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sceinces) 北京大学学报(哲学社会科学版) 47: 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Xiaohe 馬小鶴. 2014. Xiapu wenshu yanjiu霞浦文書研究 (A Study of Xiapu Manuscript). Lanzhou: Lanzhou University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Xiaohe. 2015. Remains of the Religion of Light in Xiapu (霞浦) County, Fujian Province. In Mani in Dublin: Selected Papers form the Seventh International Conference of the International Association of Manichaean Studies in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, 8–12 September 2009. Edited by Richter Siegfried, Horton Charles and Ohlhafer Klaus. Leiden: Brill, pp. 228–58. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1960. A Scientific Theory of Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montesquieu, Baron de. 2012. The Spirit of Laws. Edited by Shen Lin 申林. Beijing: Beijing Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, Runsun 牟潤孫. 1938. Songdai moni jiao 宋代摩尼教 (Manichaeism in the Song Dynasty). Fujen Sinological Journal 輔仁學志 7: 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, Zhongjian 牟钟鉴, and Jian Zhang 张践. 2000. Zhongguo zongjiao tongshi 中国宗教通史 (The History of Chinese Religion). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nian, Liangtu 粘良图. 2008. Jinjiang Cao’an yanjiu 晋江草庵研究 (A Study of Cao’an, Jinjiang). Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pelliot, Paul. 1923. Les traditions manichéennes au Fou-kien. T’oung Pao 22: 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardieu, Michel. 2008. Manichaeism. Translated by M. B. Debevoise. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Heming 王鹤鸣. 2011. Zhongguo jiapu tonglun 中国家谱通论 (Introduction to Chinese Genealogy). Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Bood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jianchuan 王見川. 1992. Cong moni jiao dao mingjiao 從摩尼教到明教 (From Manichaeism to Mingjiao). Taipei: Shin Wen Feng Print Co. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Mingming 王铭铭. 2018. Citong cheng: Binhai Zhongguo de difang yu shijie 刺桐城—滨海中国的地方与世界(Zayton: Local and World of Coastal China). Beijing: Joint Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yuanyuan 王媛媛. 2009. Bianjing busi yu moni jiao shenxiang ru min 汴京卜肆与摩尼教神像入闽 (Divination Shops in Bianjing and the Introduction of Manichean Images of Deities into Fujian). Palace Museum Journal 3: 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yuanyuan 王媛媛. 2012. Cong Bosi dao Zhongguo: Moni jiao zai zhongya he Zhongguo de chuanbo 從波斯到中國: 摩尼教在中亞和中國的傳播 (From Persia to China: The Spread of Manichaeism in Central Asia and China). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yuanyuan, and Wushu Lin. 2015. The Last Remains of Manichaeism in Villages of Jinjiang County, China. In Mani in Dublin: Selected Papers from the Seventh International Conference of the International Association of Manichaean Studies in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, 8–12 September 2009. Edited by Siegfried Richter, Charles Horton and Klaus Ohlhafer. Leiden: Brill, pp. 371–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhongluo 王仲荦. 1988. Sui-Tang Wudai shi 隋唐五代史 (The History of Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties). Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wearring, Andrew. 2006. Manichaen Studies in the 21st Century. In Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on the Sacred. Edited by F. D. Lauro. Sydney: Sydney University Press, pp. 249–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Han 吳晗. 1956. Mingjiao yu Daming diguo 明教與大明帝國 (Mingjiao and the Great Ming Empire). In Dushi zhaji讀史札記 (Essays of History Study). Beijing: Joint publishing, pp. 235–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Wenliang 吳文良. 1957. Quanzhou zongjiao shike 泉州宗教石刻 (Religious stone inscriptions in Quanzhou). Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Wenliang 吴文良. 2005. Quanzhou zongjiao shike (zengding ben) 泉州宗教石刻 (增订本) (Religious stone inscriptions in Quanzhou, expanded edition). Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Xuan 徐鉉. 1996. Jishen lu 稽神錄 (An Investigation of Gods). Edited by Bai Huawen 白化文點校. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ching Kun. 1961. Religion in Chinese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Chunlei 杨春雷. 2015. Lühen xunzong: Jinjiang duoyuan wenhua lansheng 履痕寻踪——晋江多元文化揽胜 (Seeking the Trace: A Bird’s Eye View of Jinjiang’s Multiculture). Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fenggang 杨凤岗. 2012. Dangdai Zhongguo de zongjiao fuxing yu zongjiao duanque 当代中国的宗教复兴与宗教短缺 (The Revival and Shortage of Religion in Contemporary China). Cultural Review 文化纵横 1: 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fuxue 杨富学. 2020. Xiapu moni jiao yanjiu 霞浦摩尼教研究 (A Study of Manichaeism in Xiapu). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Chongxin 姚崇新, Wang Yuanyuan 王媛媛, and Chen Huaiyu 陈怀宇. 2011. Dunhuang san yijiao yu zhonggu shehui 敦煌三夷教与中古社会(Three Dunhuang Foreign Religions and Mediaeval Society). Lanzhou: Gansu Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xuezeng 周學曾. 1990. Jinjiang Xianzhi 晋江縣志 (Jinjiang County Annals). Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Weiji 莊爲璣. 1956. Tan zuijin faxian de Quanzhou zhongwai jiaotong de shiji 談最近發現的泉州中外交通的史蹟 (On the Recently Discovered Historical Sites of Sino-Western Communication in Quanzhou). Kaogu tongxun考古通訊 (Archaeological Communication) 3: 43–48. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y. Cao’an in the Ancestral World: Contemporary Manichaeism-Related Belief and Familial Ethics in Southeastern China. Religions 2024, 15, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020185

Wang Y. Cao’an in the Ancestral World: Contemporary Manichaeism-Related Belief and Familial Ethics in Southeastern China. Religions. 2024; 15(2):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020185

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yanbin. 2024. "Cao’an in the Ancestral World: Contemporary Manichaeism-Related Belief and Familial Ethics in Southeastern China" Religions 15, no. 2: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020185

APA StyleWang, Y. (2024). Cao’an in the Ancestral World: Contemporary Manichaeism-Related Belief and Familial Ethics in Southeastern China. Religions, 15(2), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15020185