1. Introduction

During Schumpeter’s ‘great gap of blank centuries’, the Muslim world operated its markets and society through a system of regulations rooted in religious ethics (

Guang-Zhen 2008). A central element of this system was the concept of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong

1,’ which was initially a moral obligation for individuals but later institutionalised as the

hisbah2, embedding it within a formal governance structure. This article explores the models for the institution of

hisbah as proposed by medieval Muslim scholars in classical Islamic texts. The key contributors to this debate—Al-Mawardi (d.AD1058), Al-Ghazali (d.AD1111), Ibn Taymiyya (d.AD1328), and Ibn Khaldun (d.AD1406)—were primarily concerned with social justice and establishing the common good through a religious–ethical framework that aimed to promote general welfare for all. With these goals in mind, these scholars each took distinctive approaches to conceptualising the institutionalisation of ethics.

While their works are broadly situated within Schumpeter’s ‘great gap of blank centuries’ (

Islahi 2015, pp. 64–65;

Tag El-Din 2013, pp. 42–44), much of the post-Schumpeter discourse has acknowledged and focused on their normative economic principles, often drawing connections and parallels to other notable figures in the history of economic thought, such as Saint Thomas Aquinas (d.AD1274). The scholars’ arguments are deeply embedded in the religious–ethical system of Islamic thought, grounded in scholastic jurisprudence, and carry significant theological, political, philosophical, and moral implications. This presents a challenge for comparative analysis, as their approach is intertwined with religious doctrine and ethical considerations, making it difficult to deconstruct within a purely economic framework.

The term

hisbah is not explicitly mentioned in the Qur’an. It is derived from the Arabic root

h.s.b, which signifies an arithmetic problem or calculation (

Holland 1992, p. 135). The verb

hisbah is typically translated as “to take into consideration” (

Holland 1992, p. 135). However, there is no historical reference that provides a definitive explanation for the use of this term (

Cahen et al. 2010). Broadly,

hisbah conveys three levels of meaning (

Vikør 2005, p. 197):

- (i)

Within the court of law, it refers to the right of a party who is not directly affected to initiate a case on behalf of the absent or affected parties;

- (ii)

In general terms, it signifies the religious duty of every Muslim to subscribe good and forbid wrong;

- (iii)

Specifically, it refers to an institution and a public office responsible for monitoring the religious perceptions within the market and the endorsement of public morality by performing the duty of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’.

The aim of this article is to deconstruct the works of Ibn Khaldun, Al-Mawardi, Al-Ghazali, and Ibn Taymiyya, highlighting their distinctive approaches to the institutionalisation of ethics. The study critically evaluates the political–social factors that shaped their thought, using comparative analysis to explore the diversity of their ethical approaches. The current literature lacks a comprehensive perspective on the range of views regarding religious ethics in Islamic thought. This study addresses this gap by focusing on these scholars’ examinations of the operation and scope of the institution of hisbah, which is conceptualised in the literature as an Islamic institution rooted in legal positivism. Hisbah plays a key role in upholding market and societal norms based on moral values, monitoring behaviours to ensure that what is morally right is upheld while prohibiting what is considered wrong, as clarified through usul-ul-fiqh (Islamic legal theory).

This study compiles the narratives of these four medieval Muslim scholars and subsequently deconstructs them through a comprehensive narrative analysis. By critically analysing each scholar’s conceptualisation of hisbah, the study models how they classify what is good while exploring the various methods they propose for promoting ethical conduct. Lastly, the paper examines how each thinker constructs their understanding of the value of goodness (value-goodness), with key differences emerging, particularly in their approaches to the debate on the institutionalisation of ethics.

The paper is organised into five parts, as follows: Firstly, it introduces the concept of the institutionalisation of ethics and defines the institution of hisbah. Secondly, the issue of ultimate happiness and human rights is discussed. The third part concentrates on the notion of ‘good’ and the manners in which it can be implemented. The fourth section discusses ‘wrong’ and modes of preventing it. The fifth component considers ‘enjoining what is good and forbidding wrong’ as a principal duty of Islam, which is viewed as a philosophy of life, and considers its standing in economics.

2. The Institutionalisation of Ethics and the Institution of hisbah

The concept of the institutionalisation of ethics in the Islamic literature was defined and promoted by classical authors and philosophers during the early phases of ethical thought and was primarily concerned with markets and business relations. Al-Mawardi, for instance, explored the jurisdiction and scope of

hisbah by focusing on areas overlooked by other institutions. He argued that the institution should address the grey areas not covered by government bodies, magistrates, courts of law, or other public offices (

Al-Mawardi 1996, pp. 260–63). The jurisdiction of

hisbah, according to him, extends beyond the economic sphere to include social morality, alongside spirituality. Al-Mawardi also differentiates between tort law, the courts, and the functions of

hisbah, noting that its scope can overlap, exceed, or fall below that of the courts (

Al-Mawardi 1996, p. 261).

This conceptualisation of

hisbah has evolved over time, and by the Fatimid era (AD909–1160) in Egypt, the

muhtasib (the officer in charge of

hisbah) had become a prominent figure. The role was marked by a ceremonial investiture, distinctive dress, and possessions (

Buckley 1999, p. 9). Under the Mamluks (AD1250–1517), the

muhtasib rose further in political rank, positioned just below the Head of Public Treasury, and ranked fifth in the judicial hierarchy (

Buckley 1999, p. 10). This elevation was likely a necessity; as

Rosenthal (

2009, p. 55) explains, the integrity of the

muhtasib was crucial for maintaining public order and morale. Arguably, the political organisation of the Muslim community was seen as superior to others because the

muhtasib was tasked with ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’.

Al-Mawardi’s

hisbah bears some resemblance to the court of law, as it possesses the authority to address complaints brought by a plaintiff. However, this authority is confined to issues within the marketplace, such as fraud involving incorrect measures and weights, deceptive transactions, contracts or pricing, and delays in the payment of debts (

Khan 1982, pp. 135–51;

Al-Mawardi 1996, p. 261). Unlike the broader jurisdiction of the courts,

hisbah is restricted to handling only those cases that fall within its specified range of activities (

Dogarawa 2013, pp. 51–63;

Al-Mawardi 1996, p. 262). This range is historically determined based on the actions traditionally performed by the institution of

hisbah, thus maintaining the relevance of the court of law within market affairs. Furthermore,

hisbah is bound by its framework of acknowledged claims and cannot hear evidence or administer oaths in disputes characterised by mutual repudiation and denial, which are responsibilities more appropriate for a court of law (

Al-Mawardi 1996, p. 262).

There are two notable aspects where

hisbah surpasses the authority of the court of law. First,

hisbah inherits the religious duty of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ through the

Shari’ah (Islamic Law) itself, which grants it legitimate grounds to investigate, examine, and act without the need for a plaintiff (

Al-Mawardi 1996, p. 262). Second, Al-Mawardi defines

hisbah as holding coercive powers, particularly in religious matters, such as ensuring compliance with religious duties (

Attahiru et al. 2016, pp. 125–32). The scope of

hisbah is similar to tort law in that both aim to protect public welfare and address issues of injustice; although,

hisbah specifically handles matters that fall outside the traditional functions of the court (

Glick 1971, pp. 59–81). Al-Mawardi also notes that

hisbah handles matters below the functional capacity of the court of law (

Buckley 1992, pp. 59–117).

Al-Ghazali (

1982a, pp. 238–63), however, does not emphasise

hisbah as an institution but rather focuses on the moral duty of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’. He expands the scope to include individuals with diminished or no legal capacity, arguing that even they should be encouraged to do good, though they are not bound by divine punishment if they fail (

Cook 2010, pp. 447–48). Al-Ghazali also addresses societal impact, acknowledging that certain actions may affect the broader public, while cautioning against directly confronting rulers for fear of retaliation. His vision of

hisbah would allow intervention in all aspects of life and be supported by moral teachings and religious discourse.

Al-Ghazali further defines the boundaries of

hisbah through ethical guidelines. He introduces three ethical requirements: certainty of wrongdoing,

taqwa (fear of God), and good conduct, emphasising that acting without these qualities would often exceed the limits of

Shari’ah (

Al-Ghazali 1982a, p. 246). However, he does suggest that the duty to command good and forbid wrong should be downgraded to the classification of a voluntary action if there is a threat of harm from retaliation (

Al-Ghazali 1982a, p. 245). Despite this framework, these requirements remain subjective and open to interpretation.

Ibn Khaldun (

1967a, p. 462–63) approaches

hisbah as a non-autonomous religious office, drawing its authority from the Caliph, which contrasts with Al-Mawardi’s view that

hisbah derives its power from the Muslim community. Ibn Khaldun describes historical examples where

hisbah was subordinated to the judiciary, such as in Egypt under Fatimid rule and Andalusia under the Umayyads. Arguably, this shift in authority led to the loss of autonomy for

hisbah, transforming it into a royal office under state control.

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, p. 26) supports using

usul-ul-fiqh as the framework for performing the duties of

hisbah. He further suggests that

hisbah should administer punishments for religious transgressions, with the exception of capital punishment. These punishments, according to Ibn Taymiyya, are those explicitly stated in primary Islamic sources, reflecting his attempt to regulate societal behaviour through divine obligations.

According to the majority of the above positionings, the institution of hisbah can be classified as a ‘quango’ (quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisation) within the modern state infrastructure that acts to secure moral outcomes in the economic domain.

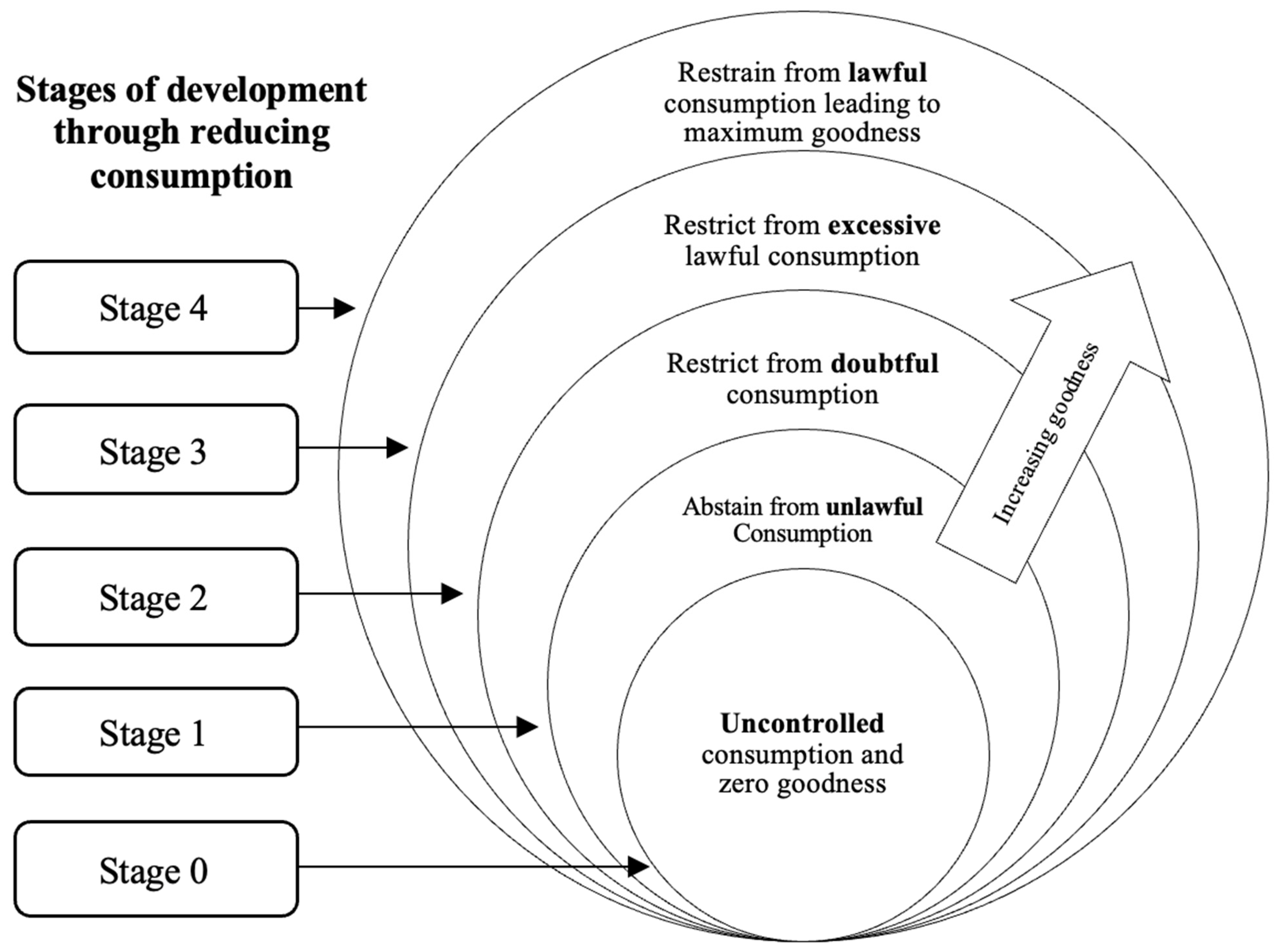

3. Ultimate Happiness and Individual Human Rights

Sa’ada (ultimate happiness) is achieved, according to Al-Ghazali, through complete devotion to God. To progress towards this devotion, he emphasises the importance of reducing consumption in leading to asceticism, which in turn increases value-goodness. Al-Ghazali appears to view goodness and ultimate happiness as outcomes of the same actions. His reasoning suggests that the concepts of ‘good’, ‘lawful’, and ‘undoubtedly lawful’ are categorically different. Moreover, he implies that by giving up something lawful or undoubtedly lawful, one reduces the intrinsic wrong within oneself, thereby increasing one’s aggregate value-goodness.

This perspective implies that the criteria for what is good is not solely determined by

fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) compliance, but rather by acts of devotion towards God. As devotion leads to ultimate happiness, happiness becomes the standard by which one distinguishes between good and wrong. In Al-Ghazali’s worldview, there is no intrinsic good; all forms of good derive their value from the ultimate good of a devotion to God. As such,

Al-Ghazali (

2008, p. 31) argues that human perfection is attained when love for God conquers the heart and predominates over all other affections. Thus, in Al-Ghazali’s view, the value of goodness grows as one progresses toward human perfection, moving beyond juristic restrictions on the unlawful to self-imposed restrictions based on doubt avoidance. Ultimately, this particular journeying is defined by asceticism, which is essential for achieving

falah (salvation).

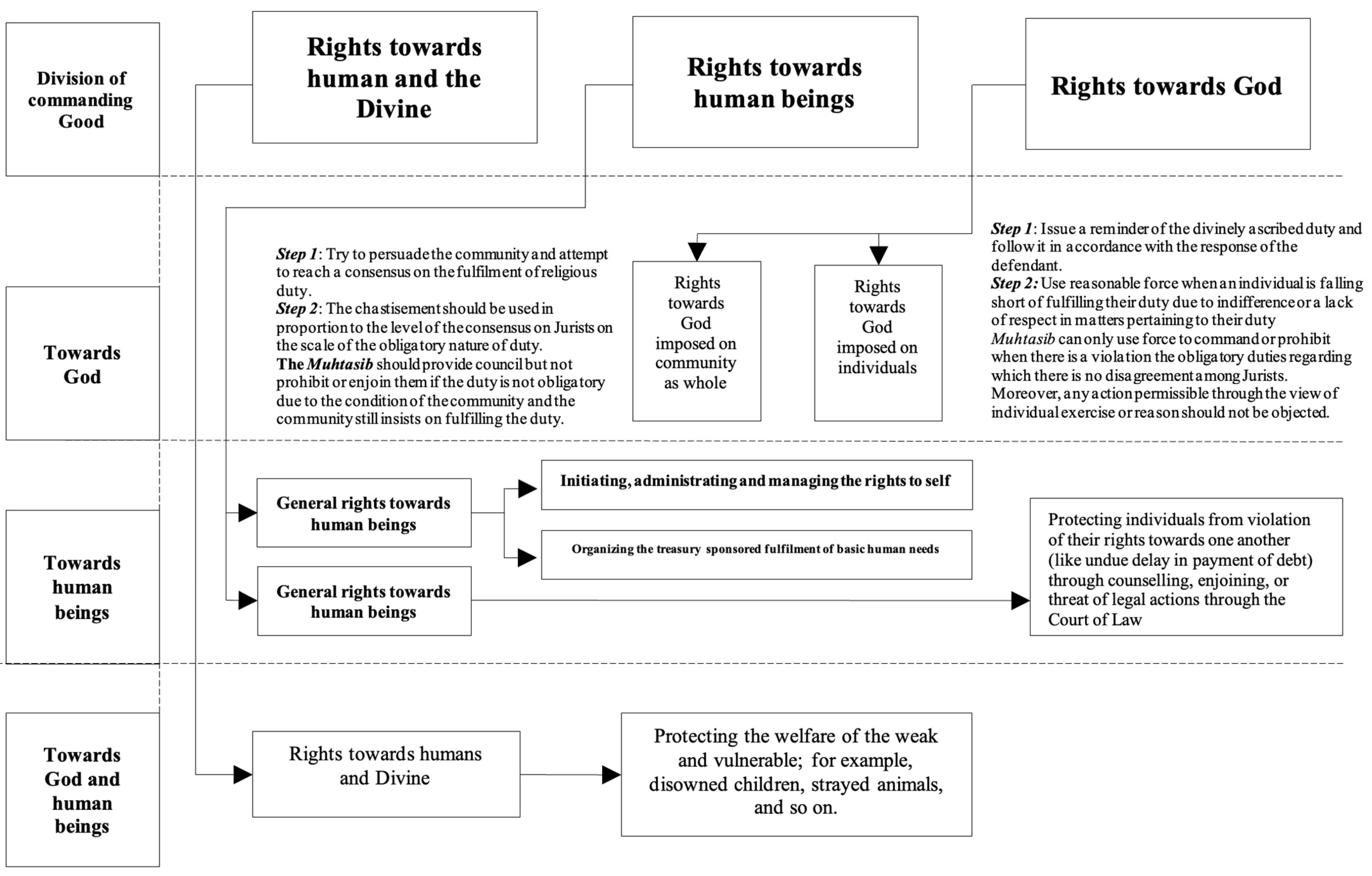

Al-Mawardi (

1996, pp. 263–66) attempts to approach the issue of defining good from the viewpoint of rights, duties, and obligations. He categorises the rights, as shown in

Figure 1, into the following three categories: good originating from the rights of the divine; good emanating from the rights of human beings; and good related to the common rights of the divine and the rights of their fellow human beings. He then suggests that good should be understood within the frame of enjoining what accomplishes these rights (

Attahiru et al. 2016, pp. 125–32).

Al-Mawardi (

1996, pp. 263–66) understood rights in a manner consistent with other Muslim scholars; he viewed them primarily as duties owed to others, rather than as inherent attributes of human beings or divine entitlements. He used the concept of rights as a framework to structure and regulate the implementation of the practice of ‘enjoining good’, while simultaneously placing restrictions upon it (

Khan 2019, p. 177). This approach emphasises the social and moral responsibilities tied to rights, rather than individual entitlements.

As illustrated in

Figure 1,

Al-Mawardi (

1996, pp. 263–66) argues that the foremost duty or right is towards the divine. He further classifies this into the ‘duty of individuals towards God’ and the ‘duty of society towards God.’ Al-Mawardi adheres to a conservative philosophy, describing the ‘right of society towards God’ within the framework of maintaining the acceptability and correctness of traditional sociological perspectives and the mainstream practice of Islam as societal standpoints (

Maróth 2015, pp. 235–44). In terms of policy implementation, Al-Mawardi advocates a lenient approach to ‘enjoining good’, whereby he finds a use for individual reasoning to counterbalance the over-regulation of society in religious affairs.

Al-Mawardi also views the institution of

hisbah as an entity that should preferably work collaboratively with the community, aiming to achieve consensus in fulfilling rights and duties through mutual agreement (

Stilt 2012, pp. 38–72). Similarly, regarding the ‘rights towards human beings’,

Al-Mawardi (

1996, p. 266) suggests that

hisbah officials should encourage the public to exercise their right to self-help and to maintain or improve public welfare provisions in their locality, particularly when state resources are insufficient to fund such projects.

Al-Mawardi (

1986, pp. 203–4) proposes a limited framework with narrow restrictions on the enjoining of good towards individuals, particularly under the concept of ‘duties of individuals toward God’. This stems from the interpretation of primary Islamic texts by Muslim thinkers, jurists, and theologians, which often view individuals as potential impediments to fulfilling duties toward God and society. In contrast, the Muslim community as a whole is seen as the bearer and promoter of ‘good’ while being required to fulfil these duties and rights.

Al-Mawardi (

1996, p. 64) identifies three types of protections for individuals: the right to pray in mosques; protection from being declared an enemy of the state; and the right to a share in the spoils of war. However, these protections are conditional, as individuals must align themselves with the consensus of the community and refrain from theological or philosophical innovations (

Mikhail 1995, p. 4).

As a political scientist, Al-Mawardi’s theories incorporate two key features: creating incentives for individuals to adhere to mainstream societal views and justifying the ruling class’s right to govern. His stipulation, “as long as you stick with us” (1996, p. 64), reflects these objectives by promoting societal conformity and maintaining the religious dominance needed to secure both social harmony and the legitimacy of political authority.

The distrust towards individuals, the endorsement of good as a responsibility of the Muslim community, and the conditions introduced for securing protection from forces that encourage good and forbid wrong can be understood in the context of Al-Mawardi’s social and political environment, as opposed to being strictly derived from the primary Islamic sources. Al-Mawardi (who served as a

qadi (judge) and diplomat), was tasked by the Abbasid Caliph Al-Qadir (r.AD991–1031) with the mission of “restoring Sunnism” (

Crone 2004, pp. 224–26). The condition of ‘stick with us’ for receiving protection from the forces of

hisbah aligns with Al-Mawardi’s broader role of reinforcing the authority of the Sunni methodology under Abbasid’s rule.

4. Good and Modes of Encouraging Good

The major difference between the moral doctrine of utilitarianism and Ibn Taymiyya’s theory—often referred to as theo-utilitarianism (

Hoover 2019)—lies in how the concept of good or happiness is perceived. In Ibn-Taymiyya’s framework, good and happiness are evaluated through the lens of the

Shari’ah, whereas pain and pleasure are used as instruments to measure and compare the balance between ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ versus ‘not enjoining and not forbidding’. In other words,

the Shari’ah determines what is right and wrong, while pain and pleasure serve as tools to assess whether a good should be commended or a wrong be prohibited.

This implies that, in certain situations, pain and pleasure may take precedence over the good as decreed by the

Shari’ah. Moreover, Ibn Taymiyya emphasises the importance of the ijma’ (consensus) of the Muslim community as a criterion for determining what is ultimately good (

Vogel 2000), even though he grounds the legitimacy of

hisbah in Islamic theology.

Al-Ghazali provides an alternative to Ibn Taymiyya’s consequential moral reasoning. Instead, Al-Ghazali uses his hierarchy

of Maqaasid Al-Shari’ah (Objectives of Islamic Law). However,

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, p. 80) counteract this by suggesting the need for an evaluation of the consequences of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’, while also acknowledging that situations arise where right and wrong will be mutually inextricable. In this, Ibn Taymiyya’s line of reasoning (

Ibn Taymiyya 2018, p. 265) inclines towards the moral doctrine of utilitarianism; the basic principle of his doctrine is “man’s love of what is proper and hatred of what is improper … correspond to God’s love, hatred … as expressed in the Law”.

This is contrary to the mainstream theological position of taking good and wrong in the context of pain and pleasure and defining the latter two terms in conjunction with their meaning in this world summed against the explanation of them in the hereafter. The abstraction of a divine concept of justice and the criteria based on duties for salvation in the hereafter—as specified in primary sources of Islam—are used to evaluate the degree of pain and pleasure experienced in the hereafter. Importantly, the sum of the pain and pleasure of this world and of the hereafter can produce different results when compared to only focusing on the pain and pleasure of this world.

Similar to Mill’s greatest happiness principle and Bentham’s pleasure principle,

Ibn Taymiyya (

1988, p. 102) asserts that ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ is a universal public need whereby it provides a criterion for determining what is good or wrong. Moreover,

Bentham (

1988, pp. 99–102) suggests pleasure to be the only good and pain to be the only wrong whilst further adding, “there is no such thing as any sort of motive that is in itself a bad one”. On the other hand,

Ibn Taymiyya (

1988, p. 38) upholds the understanding of earlier scholars that human happiness lies in adhering to the Islamic creed, with public welfare serving as the crucial component and remaining the state’s ultimate responsibility. Al-Farabi (d.AD950) is largely responsible for the Islamic discourse on happiness, having argued that “the truth about divine things and the highest principles of the world, be conducive to virtuous actions, and form part of the equipment necessary for the attainment of ultimate happiness” (

Mahdi 1987, p. 207). However, the jurists understood the

Shari’ah as a criterion that could distinguish and define virtuous actions, providing the necessary equipment for attaining happiness.

Ibn Taymiyya views public welfare as a universal public need, which he includes among divine rights. He argues that actions motivated by ‘enjoining good or forbidding wrong’ do not necessarily lead to an increase in good or a decrease in wrong, emphasising the neutral nature of such motives. This contrasts with the majority of Muslim jurists, who believe that a good motive inherently carries goodness, even if it leads to unintended negative outcomes. In their view, the value of the motive remains intact. However, Ibn Taymiyya contends that within the context of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’, suggesting that motives may not inherently possess goodness, and if the consequences are harmful, the motive and action may lack any goodness.

It could be argued that the underlying reasoning behind Ibn-Taymiyya’s position aligns with Al-Farabi’s argument that “Happiness cannot be achieved without… the achievement of perfection … The distinction between noble and base activities is thus guided by the distinction between what is useful for, and what obstructs perfection and happiness” (

Mahdi 1987, p. 209). In summarising this view, noble activities take precedence over base activities in enjoining good and eventually contribute towards achieving perfection, which ultimately leads to happiness.

It could further be suggested that this may explain why Ibn Taymiyya does not extensively discuss or strengthen principles of equality, universal human rights, or political–social rights, despite scriptural foundations that support such principles. His focus on perfection and happiness may have overshadowed the broader development of these rights in his theoretical framework.

For Bentham, the moral justification for legislating any conduct as a crime is based on the principle of the greatest happiness for the greatest number (

Conklin 1979, p. 67). In contrast, for

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, p. 54), the moral justification for enjoining or forbidding any action is grounded in the concept of universal public need. The practical challenge with Ibn Taymiyya’s approach is that, unlike Bentham’s theory (where the majority decides what constitutes the ‘greatest happiness,’), Ibn Taymiyya’s framework demands that the

Shari’ah determines the public need. In practice, this means that jurists, jurisconsults, or theologians (amongst others) are responsible for interpreting public need, distinguishing between pain and pleasure, and deciding whether a good should be encouraged and a wrong prohibited. In other words, this structure places considerable authority in the hands of state departments, particularly the institution of

hisbah, as they are empowered to define and enforce what is considered good and wrong, based on religious law.

Additionally, this system presents both theological and practical challenges. While one might suggest that the Qur’an

3 provides some philosophical basis for democratic governance, there is no explicit Qur’anic guidance on governance or any corresponding divine response, unlike the clear warnings about polytheism. Without such scriptural backing, constructing a theologically sound model to predict the transcendental consequences of state laws or

hisbah regulations is not feasible. Additionally, the lack of discourse addressing questions like ‘what is good?’, ‘how to measure its benefits?’, and ‘how to assess regulations and policies based on their potential outcomes?’ further weakens the case of Ibn Taymiyya’s theory.

Al-Ghazali’s approach to ethics bears similarities to Kant’s moral philosophy, particularly regarding the role of goodwill. According to

Johnson and Cureton (

2022), Kant asserts that a good person is defined by a will that aligns with moral law. Al-Ghazali’s discourse on

hisbah (

Al-Ghazali 1982a, p. 237) reflects a similar principle: what Kant calls “goodwill”, Al-Ghazali describes as the ‘heart of a believer’, which serves as the criterion for distinguishing between good and wrong. Like Kant, Al-Ghazali delves into how this moral criterion operates, identifying God-consciousness and Islamic wisdom as the essential attributes guiding moral decisions. He derives these attributes from descriptions of the righteous in Islamic scripture, employing the theological framework of reward and punishment in the afterlife to emphasise their importance (

Al-Ghazali 1982a, p. 110).

Al-Ghazali’s perspective is primarily individualistic, focusing on personal conduct rather than institutional or state-level governance. For instance, he argues that humans are unequal in the eyes of the divine, and those who are morally superior have a duty to enjoin good and forbid wrong upon those who are morally inferior (

Al-Ghazali 1982a, p. 231). Al-Ghazali stresses the consequences of neglecting this duty, often invoking divine wrath in relation to forbidding wrong, but notably excluding enjoining good in these warnings. He further suggests a strong connection between the Islamic concept of justice and the duty of enjoining good and prohibiting wrong (

Rouzati 2018, p. 47).

The majority of Al-Ghazali’s work on this topic concentrates on defining, recognising, forbidding, and handling wrong, which is consistent with the overall approach of discourse in the genre. In the context of ‘good’, Al-Ghazali resorts to defining what adds to the value of goodness rather than defining what may constitute ‘good’.

Al-Ghazali links the value of goodness with development, which in his view is the restriction on consumption of goods and services. Expanding this asceticism leads to increased development, which in turn elevates the value-goodness. Al-Ghazali suggests that every prohibited thing is bad, while all the things allowed in

Shari’ah have some value of goodness in them.

Al-Ghazali (

1982b, p. 81) categorises the reducing of consumption within the

Shari’ah into four stages of development (

Figure 2). He proposes that each class acts as a stage of development, and by confining oneself from consumption of things in one class, one can progress onto the next class (

Al-Ghazali 1982b, pp. 81–82); his stance being, this asceticism originates from goodwill, while simultaneously increasing the accumulated goodness in and for that person.

The first stage represents the lowest form of piety, where individuals refrain from consuming goods and services deemed unlawful within the

Shari’ah (

Randeree 2015, pp. 235–44). In the second stage, one avoids anything doubtful, even if classified as lawful by

fiqh. The third stage involves abstaining from goods and services that are lawful but could potentially lead to something unlawful or doubtful. The final stage is mystical, where an individual abstains from lawful things as an act of complete devotion to God, seeking divine pleasure by going beyond legal obligations into piety.

Al-Ghazali (

1982b, p. 81) refers to someone who reaches this stage as a

Siddiq (a person of great truth). Through abstinence, Al-Ghazali argues, a person develops and increases their individual value-goodness thereby enabling themselves to better distinguish overall between good and wrong (

Ghazanfar and Islahi 1990, pp. 381–403).

Meanwhile, Al-Mawardi found himself in the Era of the Abbasids, where the non-secular nature of their political structure as well as their hostility towards reframing anything away from the mainstream religious position could in itself be the reason why the Abbasids held strongly to dominant religious views, as any movement away from this would immediately challenge their sovereignty and legitimacy as rulers. It is also possible that the political position on the prevention of moving away from mainstream thinking may have originated as a result of external influence stemming from Greek civilisations. The “assumption that the private religious rites ... were inextricably connected to aristocratic power” is largely associated with the Greek philosopher Cleisthenes (d.508 BC), who reformed the Athenian constitution. While discussing the methods of establishing the ‘extreme’ form of democracy, Aristotle (d.322 BC) suggests reducing private religious rites to a few public ones and using every means to mix everyone up to the greatest possible degree and loosen the bonds of previous associations (

Kearns 1985, p. 189).

Thus, there is a possibility that Al-Mawardi may have been influenced by Aristotle’s methodology, particularly considering the Abbasids’ focus on integrating diverse cultural and religious groups into a unified Islamic framework (

Heck 2002, p. 15). Aristotle advocated for establishing democracy by reducing private religious rites in favour of publicly accepted ones to create a cohesive society. Similarly, the Abbasids may have used this strategy to forge and maintain a singular Islamic identity under a religiously justified administrative structure. This approach is evident in Al-Mawardi’s historical account, as well as Caliph Al-Qadir’s efforts to restore Sunnism (

Tholib 2002, pp. 257–59). These measures align with Aristotle’s idea of filtering religious practices to establish a unified communal identity.

This context suggests that balancing or restricting the forces of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ through the concept of rights could be a crucial factor in maintaining order. Developing individual rights further would offer stronger protection, helping to determine what is truly good and preventing wrong from being misclassified as right. Without this development, the ability to accurately define and uphold good could be compromised, leading to misjudgements in moral governance.

The concept of ‘rights’ is crucial when determining what can be prescribed as good within Islamic thought, as it helps differentiate between what is legally permissible and what is ethically sound (

Asutay 2007). Muslim scholars have implicitly acknowledged the limitations and risks of using legal theory to enforce moral duties, particularly in the practice of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ (

Asutay 2007;

Chapra 2000;

Naqvi 1981). While they attempted to establish a framework to regulate those performing this duty, the discourse lacks the depth needed to create a legally binding structure. Islamic discourse on this topic fails to lay the groundwork for legislative boundaries that could effectively regulate the actions of those who enforce good and prohibit wrong. Ibn Taymiyya’s utilitarian approach (which promotes a pragmatic use of this duty) does not address the problem of entrusting unelected political authorities with utilitarian decision-making power; hence, gaps are left in accountability and ethical governance. His approach, however, does indirectly highlight the absence of such concepts and their importance in defence of the discourse. Moreover, one could argue that the development of such concepts by jurists, theologians, and political scientists was neither in their interest nor a rational choice given the social constructs of their era. Throughout its history, the institution of

hisbah lacked a clear philosophical and conceptual framework that could create a balance of power and provide the required framework for the institution to exercise its powers.

5. Wrongs and Modes of Preventing Wrong

While Islamic thought lacked a conceptual framework of applied ethics (which would have been extremely beneficial for the institution of hisbah), the abstract concept of ‘wrong’ is widely described and debated within the Islamic literature. This is because the general approach of legal theories is to classify wrong vigorously and postulate whatever is left unlegislated, unrestricted, and unclassified automatically as acceptable and therefore ‘good’.

Al-Ghazali (

1982a, p. 245) outlines three key qualifications for those seeking to prevent wrong: knowledge of the wrong act; God-consciousness; and good conduct. The latter two carry a moral tone, while having knowledge is used by Al-Ghazali to confine the practice of denouncing wrong within the limits of the

Shari’ah, specifically concerning the “place, limit, and order” (

Al-Ghazali 1982a, p. 245) for such actions. His concern about the potential for communal misuse or overzealous religious enforcement leads him to advocate for regulation through the

Shari’ah, particularly given his allowance for vigilantism in social and religious matters (

Ghazanfar and Islahi 1990, pp. 381–403). While Al-Ghazali’s argument is comparable to the modern concept of a citizen’s arrest, his effort to regulate the prevention of wrong through the

Shari’ah is problematic. This is especially true considering the lack of clear consensus on religious involvement in personal matters and the underdeveloped state of Islamic doctrines on privacy and human rights.

Al-Ghazali (

1982a, pp. 245–48) presents a linear view of good and wrong, asserting that the

Shari’ah is the sole means for understanding and distinguishing between them. Wrongs are classified as either

haram (unlawful) or

makruh (detestable), with the understanding of wrongs being impossible without the guidance of the

Shari’ah (

Ozay 1997, p. 1203). In Al-Ghazali’s theory, the role of the

Shari’ah is primarily to define what is wrong, while understanding what is good is linked to the pursuit of human happiness and the progression towards human perfection. This progression is achieved through devotion to God, particularly by embracing asceticism, which increases the value of goodness within an individual. As a person advances through the stages of self-development, their value-goodness will improve, enhancing their ability to distinguish good from wrong in various situations. Al-Ghazali suggests that it is a religious duty for those with an advanced form of goodwill to enjoin what is good and forbid what is wrong.

Ibn Khaldun (

1967a, p. 463) avoids detailed discussions about specific wrongdoings within the context of

hisbah. Instead, he suggests that wrong should be understood as anything that negatively affects public welfare (

Boulakia 1971). In this framework, the institution of

hisbah would monitor the market and society to identify and correct practices that harm the general welfare. Ibn Khaldun’s concept of public welfare is linked to injustice, which he argues leads to the destruction of civilization (

Ibn Khaldun 1967b, pp. 103–7). Citing the five

Maqaasid Al-Shari’ah, he emphasises that divine law aims to prohibit injustices that could cause “destruction and ruin of civilization” and potentially lead to the eradication of humanity. Thus, the wrongs that

hisbah should address, are practices in both the market and society that have the potential to undermine the very fabric of community, society, or civilization. This reasoning implies that

hisbah’s intervention should be limited to situations where the survival or stability of society, community, or civilization is at risk.

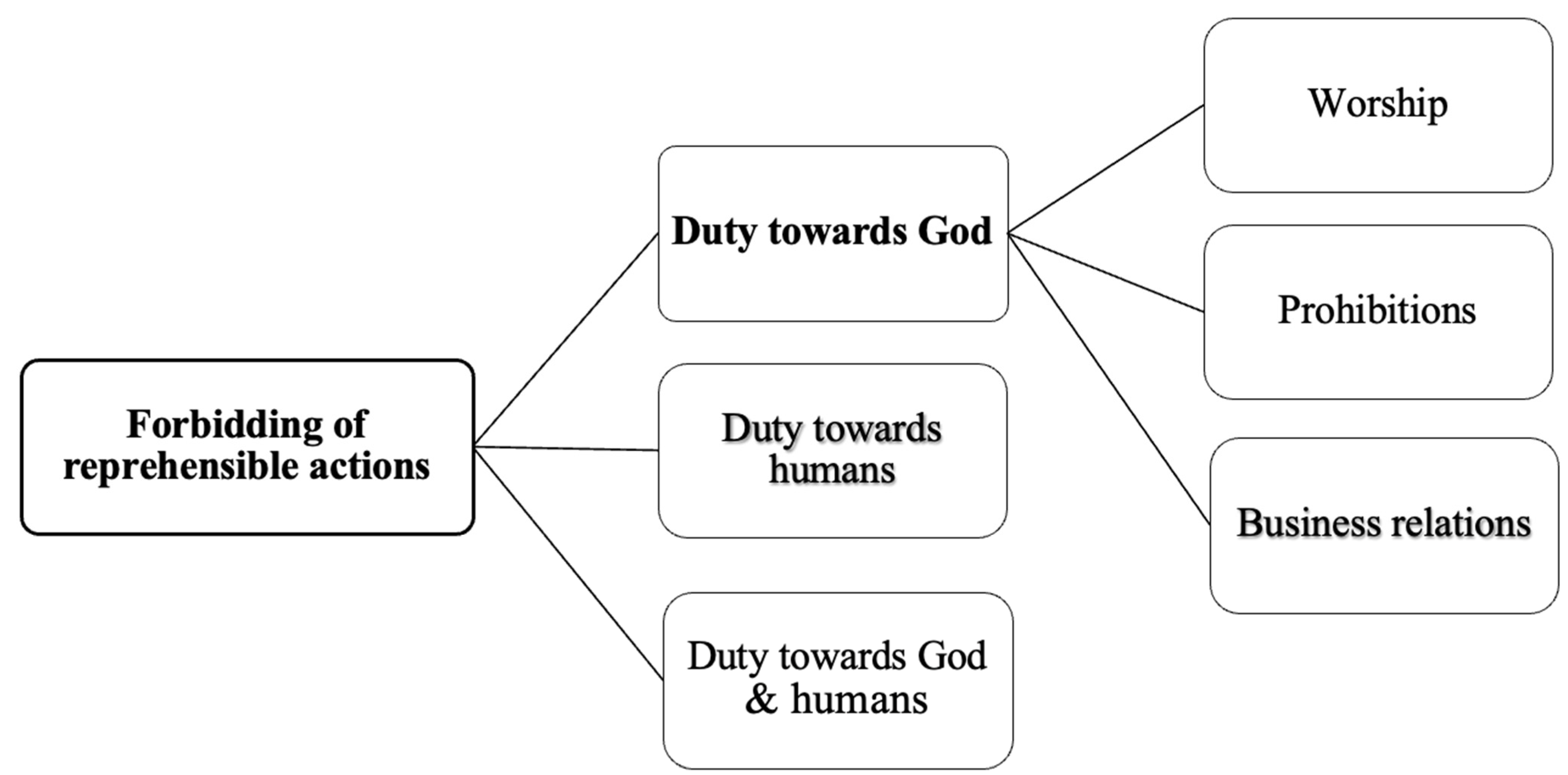

Al-Mawardi (

1996, p. 268) defines wrong in terms of reprehensibility and blameworthiness, exploring it within the framework of individual duties, which is similar to how he approaches good. He identifies three main categories of wrongs that fall under the scope of forbidding reprehensible actions, as shown in

Figure 3. The first category, ‘duties towards God’, is further divided into three branches: rites of worship, prohibition, and business transactions (1996, p. 268). For rites of worship, Al-Mawardi advocates for the establishment of conventional practices and views, enforcing this standard as a form of ‘forbidding wrong’. In the second branch, he calls for the prohibition of ‘dubious situations or blameworthy actions’ and seeks to regulate the institution of

hisbah’s use of suspicion. Under business transactions, Al-Mawardi argues that social or economic dealings that remain illegal under the

Shari’ah should be forbidden, even if all parties involved consent to them.

In the first category of ‘duties toward God’,

Al-Mawardi (

1996, p. 276) advocates for a proactive role of the institution of

hisbah, emphasising its active involvement in enforcing religious obligations. In contrast, for the second category ‘duties toward humans’, he suggests a more reactive approach, addressing wrongs as they arise. Notably, the second and third (‘duties toward humans and God’) categories are closely related in Al-Mawardi’s framework; both focus on forbidding ethically incorrect practices and unjust actions, aiming to protect moral and social order.

Al-Mawardi does not establish a comprehensive framework to protect individuals from excessive enforcement of forbidding wrong. The only limitations he offers are those explicitly outlined in primary sources, such as restricting actions based on suspicion and prohibiting spying to uncover wrongdoings. In line with traditional

hisbah manuals, Al-Mawardi also examines various wrongs specific to different professions and how they should be regulated through ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’. He identifies three main types of marketplace misconduct: negligence, dishonesty, and poor-quality goods. He further categorises market players based on the kinds of wrongs they might commit (

Al-Mawardi 1996, p. 277).

Unlike Al-Mawardi, Ibn Taymiyya adopts a more utilitarian approach to forbidding wrong. While he, like other theologians, adheres to the

Shari’ah’s classification of wrong, he argues that forbidding wrong should also be evaluated in terms of the pain or pleasure it causes within an Islamic context. Ibn Taymiyya’s framework uses the

Shari’ah to identify good and wrong, but pain and pleasure serve as tools for weighing whether to act towards ‘enjoining and forbidding’ or refrain from doing so (

Khaleel and Avdukić 2020, pp. 23–39). He further suggests that if the

Shari’ah deems something wrong, but the consequences imply more harm than good, then the

Shari’ah might need to reassess its stance.

6. Contextualising ‘Enjoining Good and Forbidding Wrong’ Within Economics

Al-Ghazali does not comment on the qualifications of enjoining good, as his focus remains on the necessity of theologically establishing the essential nature of good. One could argue that

Al-Ghazali (

1982a, p. 246) considers good and wrong as the sole options, without considering the possibility of specific actions or deeds combining both. He further advises those who wish to fulfil this duty of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ do so autonomously and privately so as to avoid anti-social behaviour; in other words, keeping the ‘wrong’ committed hidden as a way of preventing others falling into this ‘wrong’.

In hindsight, when reflecting on the problems faced by the institution of

hisbah, the guidelines of Al-Ghazali on autonomy and financial independence could have proved useful. Although, contrary to Al-Mawardi’s approach, Al-Ghazali focused his theory purely on vigilantism. Al-Ghazalian discourse focusses on the “merits of enjoining good” and the “necessary qualifications for one who forbids wrong” (

Al-Ghazali 1982a, pp. 230–32). With regards the former, Al-Ghazali demonstrates the obligatory nature of this stipulation by referencing Qur’anic verses and Prophetic traditions. He elucidates the societal ramifications by recounting an oral tradition from the Prophet (Peace Be Upon Him), who describes a period when the act of prescribing goodwill led to conflicts, as the individual prescribing good may encounter retribution from the individual receiving the good.

From a different perspective,

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, p. 38) considered the duty of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ as an axiom for governance, which ought to be jointly exercised by all state departments. Additionally, he advises that the

muhtasib should perform their duty by taming market forces and administering adherence to religious commandments to the general public (

Islahi 1985, pp. 51–60).

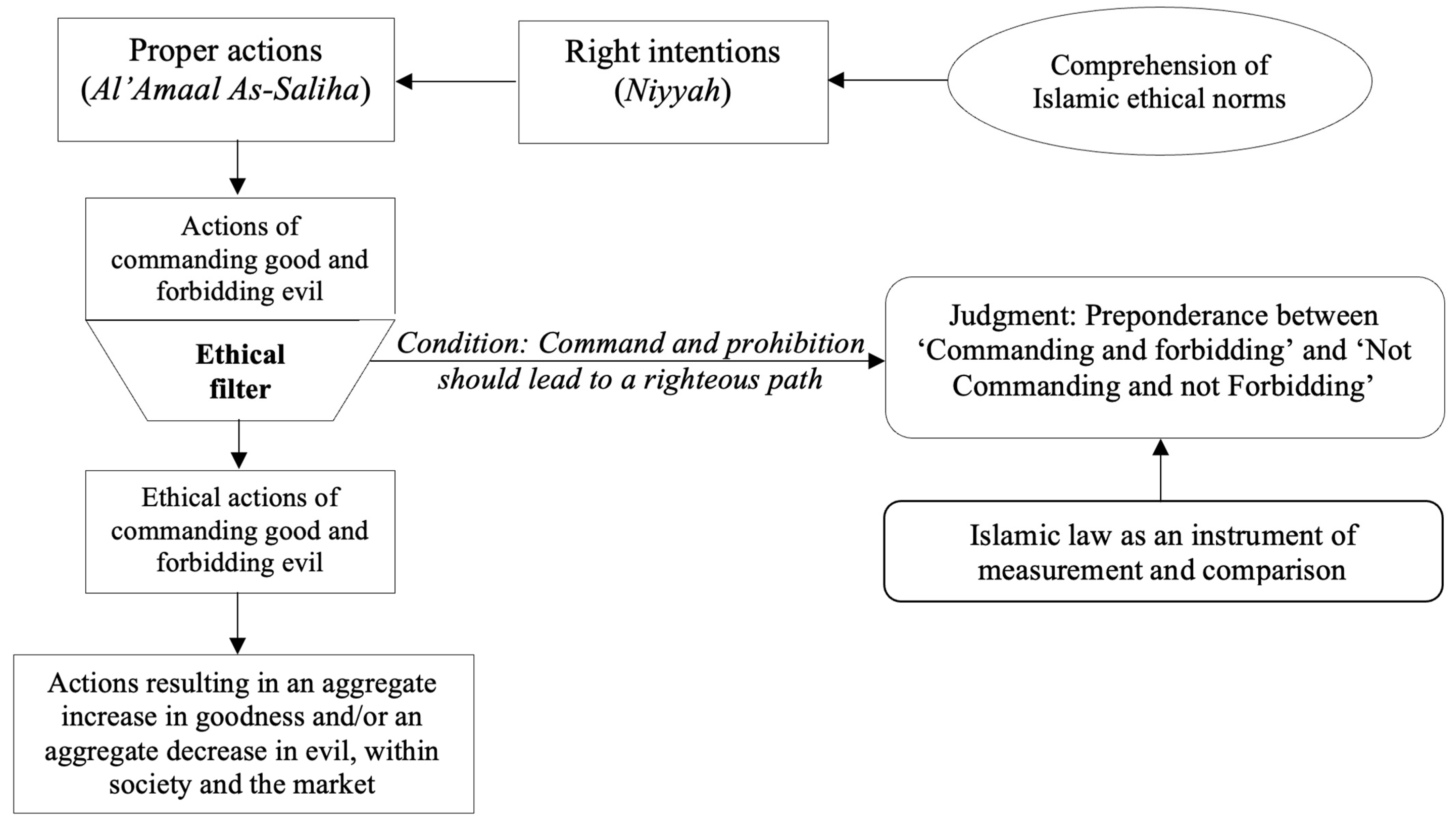

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, p. 26), like other theologians, places the management of mosques, along with the supervision of

imams (leaders of religious congregations in mosques) and other staff members working at mosques or similar religious institutions, under the purview of

hisbah.Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, p. 86) emphasises that knowledge of the

Shari’ah is crucial for understanding what is good or wrong, suggesting that this knowledge shapes correct intentions, which in turn guide proper actions. He applies this reasoning in a

furstenspiegel (manual for statecraft) style to define the scope of

hisbah, arguing that actions of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ must follow this process; otherwise, improper actions will result (

Islahi 1985, pp. 51–60). Further,

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, p. 87) introduces a filter, asserting that even actions based simultaneously on correct intentions and in accordance with the

Shari’ah, must meet certain conditions. The most important condition is that such actions must guide the subject towards the

siraat-al-mustaqeem (the righteous path), as illustrated in

Figure 4. This step-by-step process of implementing ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ ensures that divine rights are fulfilled, particularly those addressing universal public needs.

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, pp. 76–78) employs this framework to limit and regulate the scope of

hisbah in society and the marketplace, permitting both vigilantism and institutionalisation of its functions. He references Prophetic traditions discouraging rebellion against rulers, using these to shield rulers from being subjected to commands of good and forbiddance of wrong (

Ibn Taymiyya et al. 1992, pp. 79–80). Like Al-Mawardi, Ibn Taymiyya acknowledges the communal responsibility of this duty (

Chapra 2000, pp. 19–41). Yet, he emphasises leveraging existing authorities and powers within society to fulfil it. He argues that the responsibility lies with “able individuals”, defined as those possessing the power and authority to perform the duty (

Ibn Taymiyya et al. 1992, p. 23). This reasoning legitimises the authority of pre-existing figures in society and disregards the formation of new civil powers, potentially influencing public perceptions of institutionalised ethics. Ibn Taymiyya’s theory stresses that the institution of

hisbah derives its legitimacy and authority from the divinely mandated duty of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’ to the entire Muslim community.

Moreover, Ibn Taymiyya expands his framework for regulating the scope of

hisbah by stressing the importance of evaluating the consequences of ‘enjoining good or forbidding wrong’. He advocates for assessing whether such actions will increase or decrease overall good or wrong. If an action leads to a reduction in good or an increase in wrong,

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, p. 80) advises against proceeding with it. He states, “If the right is preponderant, it should be commended, even if it entails a lesser wrong. A wrong should not be forbidden if doing so results in the loss of a greater right. Such prohibition falls under obstructing the way of God.” This approach highlights the need to consider the broader impact of moral actions.

In Ibn Taymiyya’s theory, the

Shari’ah serves as a criterion that demarcates what is good and what is not, rather than being an instrument for measuring and comparing the preponderance between ‘enjoining and forbidding’ and ‘not enjoining and not forbidding’. Given the

Shari’ah’s focus on public welfare, it could be argued that Ibn Taymiyya’s theory has a utilitarian dimension. While using the

Shari’ah as a standard, Ibn Taymiyya emphasises the importance of directly applying primary sources to assess actions, rather than relying on analogical deduction or personal judgement (

Malkawi and Sonn 2011, pp. 111–27).

Taking a closer look,

Ibn Taymiyya et al. (

1992, pp. 29–45) proposed a systematic institutionalisation of ethics through a legal framework—notably the institution of

hisbah—in which he legitimised marketplace anti-competitive policy interventions such as price fixing, setting price ceilings, and forcing the sale of goods and justified these actions through the lens of public necessity. He extends this argument to include the unconsented sale of private property if it serves a higher public need. While Ibn Taymiyya introduces the assessment of consequences as a countermeasure to prevent totalitarianism, predicting outcomes remains problematic. His reasoning allows the scope of

hisbah to override individual rights for the greater public good or to fulfil divine obligations. Thus, Islamic religiosity, grounded in legalistic frameworks, allowed the institution of

hisbah to expand its jurisdiction even beyond economic and ethical policies.

After establishing this broad scope, Ibn Taymiyya explored how this extensive authority to enjoin good and forbid wrong can be exercised (

Salim et al. 2015, pp. 201–16). On the downside, he does not address the issue of undefined jurisdiction, instead reaffirming the expansive powers of

hisbah in regulating both the market and society, reflecting the governance structures of his time.

Ibn Al-Ukhuwah (d.AD1329), a contemporary of Ibn Taymiyya, also placed great emphasis on distinguishing between the private and public spheres of life. The regulations within his manual provide protection to individuals’ private lives (

Ibn Al-Ukhuwah 1976). Ibn Al-Ukhuwah shares a philosophical stance with Al-Ghazali on identifying and forbidding wrongdoing; he provides sanctuary to actions committed outside the public domain (

Mottahedeh and Stilt 2003). This also acts as a limit to the jurisdiction of

hisbah and its corresponding counterpart of

muhtasib; however, in reality, these limitations were rarely practiced.

Ibn Khaldun envisioned the formalisation of ethics outside the control of the government and the state, placing it within a private setting similar to craft guilds. This approach created a relative morality that adapts over time, space, and industry and depends on the people collectively shaping it. This concept aligns with futuwwa (Islamic Chivalry), which later evolved into the akhiyya (Guild System) during the Ottoman Empire. Noteworthily, political and religious elites were sceptical of Ibn Khaldun’s approach before the akhiyya system developed, as it would have reduced their control over microeconomic policies and possibly encouraged resistance to centralised macroeconomic strategies.

Similarly, Al-Ghazali’s approach was not implemented because it excluded the political class from policy making and relied solely on the subjective judgments of jurists to shape market and societal ethics.

Throughout most of Islamic history, the institution of hisbah operated in line with Al-Mawardi’s vision, primarily focusing on implementing socio-economic policies that were centrally formalised within the political sphere of the Islamic empire.

The orientations of these four scholars provide the key approaches that shaped the current discourse on the implementation of religious ethics within the marketplace and society. Momentarily, Islamic finance follows Al-Ghazali’s approach (

Henry 2004), which takes an ethical perspective on financial instruments by expanding the

Shari’ah’s objectives, while the Islamic economists

Siddiqi (

2006),

Chapra (

1992),

El-Gamal (

2006),

Naqvi (

1981),

Dusuki and Abozaid (

2007), and

Asutay (

2007) critiques’ concentrate towards favouring Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn Khaldun’s approaches, where they argue for an understanding of ethics based on theo-utilitarianism and public good.

7. Conclusions

Al-Mawardi, Ibn Taymiyya, Ibn Khaldun, and Al-Ghazali, like many theologians and jurists, use the Shari’ah as a criterion for distinguishing between good and wrong. However, their methods for applying this criterion to the institutionalisation of ethics differ significantly.

Al-Mawardi’s work seeks to address key philosophical challenges in operationalising hisbah, acknowledging the difficulties of basing the institution on the virtuous nature of its officials. His framework views rights as duties individuals must fulfil, rather than inherent rights. This limitation makes his proposed institutional framework impractical, offering little in terms of clear boundaries or a functional agenda for ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong.’ Furthermore, Al-Mawardi’s focus is largely on Islamic rituals and relies heavily on the virtue of hisbah officials, making his model more of a guideline for virtuous behaviour than a comprehensive institutional framework.

Al-Ghazali, in contrast, embraces the idea of virtue as the foundation of hisbah. He believes that asceticism leads to the development of goodwill in individuals, empowering them to distinguish between good and wrong. For Al-Ghazali, these virtuous individuals have a duty to guide society through ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong.’ His vision is utopian, focusing on the societal role of virtue, without addressing practical issues in institutionalisation.

Meanwhile, Ibn Khaldun’s stance on hisbah is that it is an autonomous religious office that remains fully supported by the presiding Caliph while proposing the institution of hisbah should identify and correct practices that harm the general welfare. Thus, his theory focuses heavily on preventing injustices by upholding public welfare through hisbah interventions that address issues limited to situations where the harmony of society, community, or civilization is at risk.

Ibn Taymiyya offers a more utilitarian approach, focusing on the distinction between what is good and wrong and whether good should be commended or wrong forbidden. He introduces the dichotomy of pain and pleasure as tools for evaluating these decisions but leaves the power of interpretation to jurists. This model lacks a clear mechanism for decision-making based on the pain–pleasure framework, concentrating authority within juristic circles and ignoring public opinion.

The theological discourses of these scholars present differing views on the purpose and application of ethics, with each scholar prioritising different aims for ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong.’ Their positions have influenced the development of diverse stances within the Muslim world regarding the institutionalisation of religious ethics in society and markets. The frameworks proposed by Ibn Khaldun, Al-Mawardi, Al-Ghazali, and Ibn Taymiyya offer a historical and political–social economic understanding of the variety of ethical approaches to market and societal regulation as seen today in various Muslim communities.