Community Relations in the Ottoman Balkans of the Suleymanic Age: The Case of Avlonya (1520–1568)

Abstract

1. Introduction

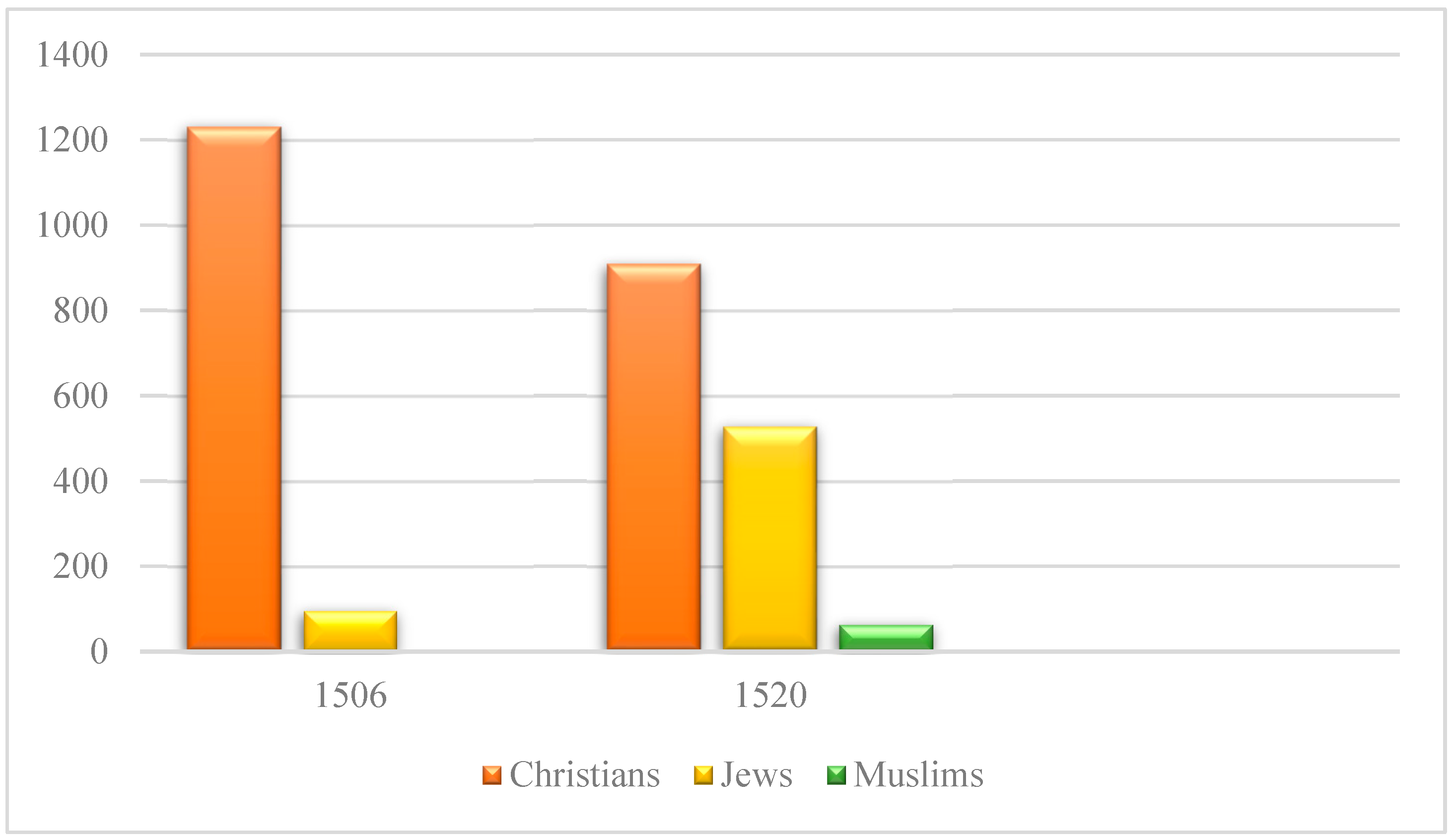

2. Settling in the City: Sephardic Jews in Avlonya

Jewish Population in Avlonya Between 1506 and 1520

3. Being Part of the City: The Economic Activities of Jews and Their Relations with Muslims

4. Becoming Ottoman: Jews of Avlonya as Reliable Subjects of the Sultan

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

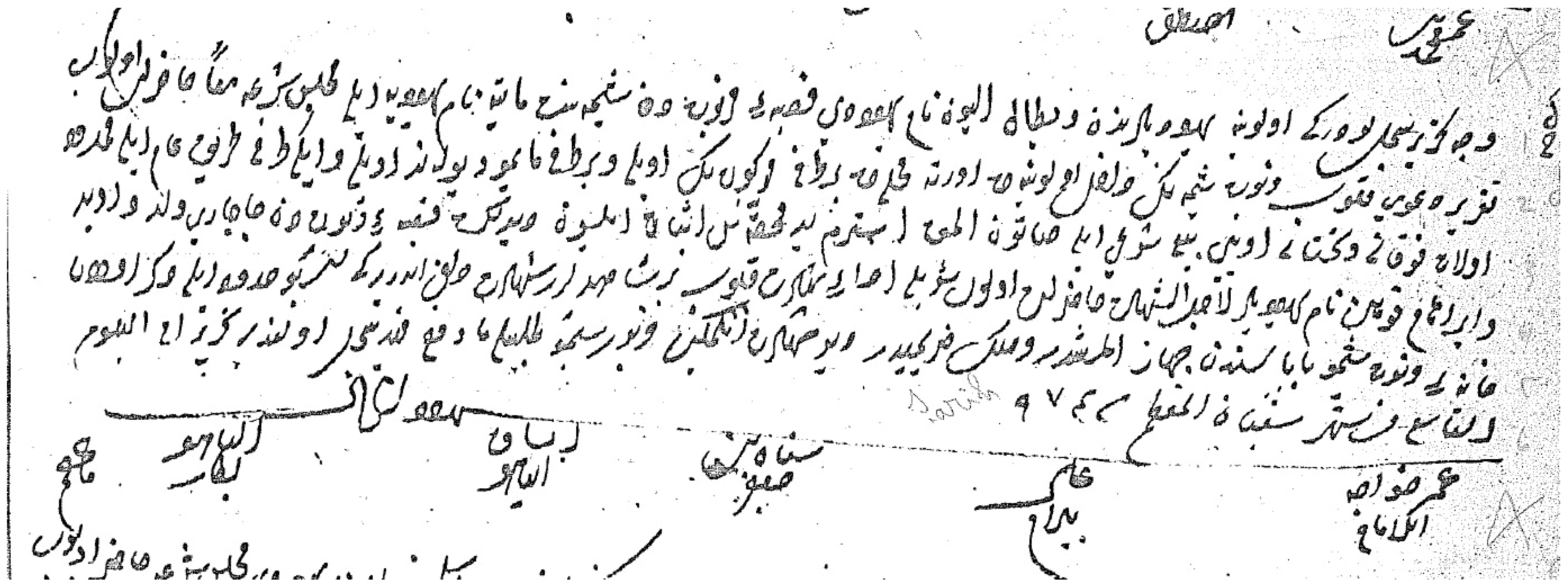

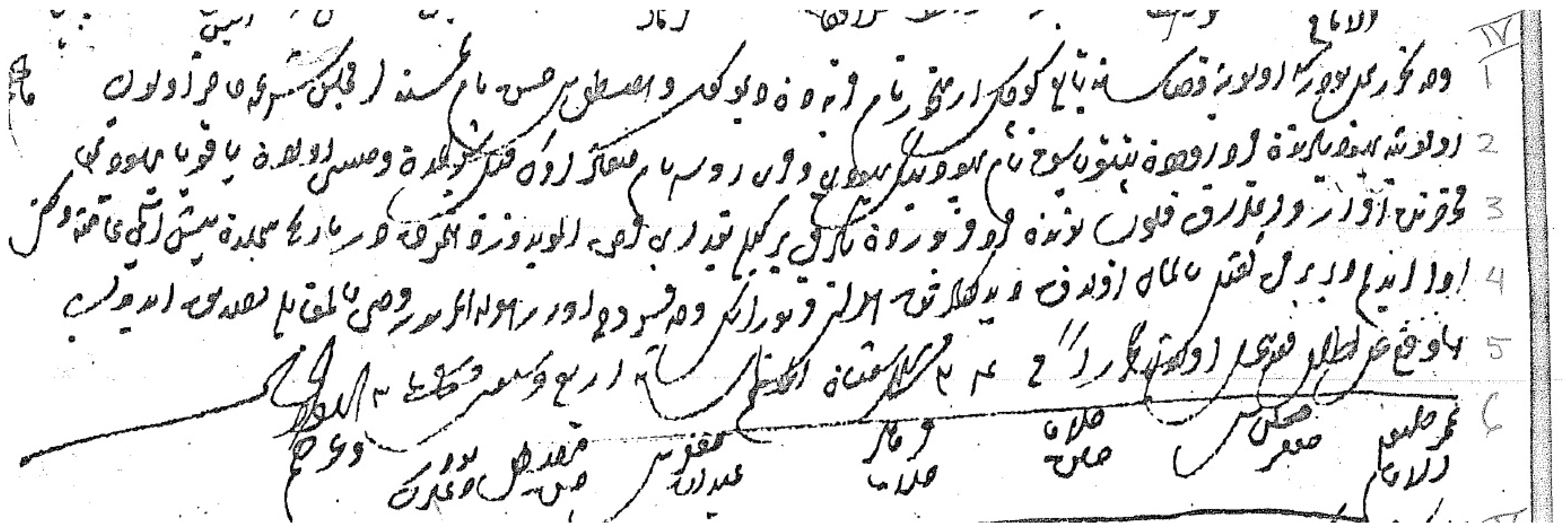

Appendix A

| 1 | The settlement areas of Avlonya’s Jewish communities are expressed in tahrir defters in different two ways: the first is quarter-based and recorded as the names of the quarters where the Jews lived. The second is recorded as an assignation based on the place from which the community had migrated. There is no explanation in the documents as to why the Ottoman administrators made this distinction. However, when comparing the records of Avlonya with those of other cities, it seems that the state customarily recorded large communities with an assignation based on the place they came from. Thus, while in Avlonya, the Jewish community was recorded as coming from Portugal and Otranto, in Thessaloniki and other cities like Edirne and Manisa, they were recorded with assignations such as Toledo, Lorka, German, Catalan, Geruz, etc. (Tokel 2010; BOA, T.T.d. 34. 2–3/3–5. and BOA, T.T.d. 99. 7/11–12, 8–13; Karagedikli 2018). |

| 2 | While the total number of households of Jews living in the neighborhoods is 514 in the table, this figure is recorded as 528 in the tahrir defter. The reason for the difference in the number of households may be that the registrar took a wrong record or miscalculated. Examples similar to this situation are frequently encountered in Ottoman Tahrir documents. The information used in the article is based on 528 households, which is the total number of records in the book. |

| 3 | The term “dhimma” is used to denote an indefinitely renewable type of contract, according to which members of other Abrahamic religions are granted hospitality and protection by the Muslim community, provided they accept the supremacy of Islam. Those who benefit from dhimma are called dhimmis, collectively known as “ahl al-dhimma” or simply dhimmis. |

| 4 | Kadimden berü yeyügelir means to use the income of this timar (benefice) from the past. |

| 5 | Elinde Padişah Beratı means that he was given an edict by the sultan to use the income of this timar (benefice). |

References

Primary Sources

- BOA, T.T.d. 34, 99.BOA, T.T.d. 99, Leaf: 8 Page: 14.BOA, A.{DVNSMHM.d..., Bâb-ı Asafî/Divan-ı Hümayun Sicilleri/Mühimme Defterleri. Yer Bilgisi: 5-1299.BOA, TSMA, No: 4985/1, Yer Bilgisi: 706-22.İSAM, H. 974–975 Tarihli 20 Numaralı Avlonya Kadı Sicili (AKS), p. 49a/4, 57b/6, 85a/1; 85a/2; 85b/3, 26b/4, 127b/2, 32b/4, 49a/5, 51b/5, 2b/4; 7b/5; 9b/5; 11b/1; 20b/5; 21a/3; 26a/3; 31b/5; 34a/3; 39b/4; 45a/1; 49a/5; 51a/2; 51b/5; 134b/3; 139b/2; 158b/2; 168b/2; 127b/2, 7b/6, 8b/4; 26b/4, 32b/4.

Secondary Sources

- Araz, Yahya. 2010. XVI. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Toplumunda Kişiler ve Cemaatler Arası İlişkilerin Dil, Söylem ve Sembolleri. Doğu Batı Dergisi 51: 159–70. [Google Scholar]

- Arbel, Benjamın. 1995. Trading Nations. Jews and Venetians in the Early Modern Eastern Mediterranean. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, Mehmet Akif. 2003. Mahkeme. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. Ankara: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, vol. 27, pp. 341–44. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, Mehmet Akif. 2007. Osmanlılar; Hukuki Adli Yapı. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, vol. 33, pp. 515–21. [Google Scholar]

- Barkey, Karen. 2008. Empire of Difference: The Ottomans in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Basel, Yusuf. 2004. Osmanlı ve Türk Yahudileri. İstanbul: Gözlem Gazetecilik Basın ve Yayın. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Naeh, Yaron. 2008. Jews in the Realm of the Sultans: Ottoman Jewish Society in the Seventeenth Century. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Naeh, Yaron. 2014. Urban Encounters: The Muslim-Jewish Case in the Ottoman Empire. In The Ottoman Middle East: Studies in Honor of Amnon Cohen. Edited by Eyal Ginio and Elie Podeh. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 177–97. [Google Scholar]

- Braude, Benjamin. 1982. Foundation Myths of the Millet System. In The Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire. Edited by Benjamin Braude and Bernard Lewis. New York and London: Homles & Meier Publishers, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Braude, Benjamin. 1991. The Rise and fall of Salonica Woollens, 1500–1650: Technology transfer and western competition. Mediterranean Historical Review 6: 216–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahen, Claude. 1991. Dhimma. In El2. Edited by Bernard Lewis, Charles Pellat and Joseph Schacht. Leiden: Brill, vol. II, pp. 227–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cesarani, David. 2014. Port Jews: Jewish Communities in Cosmopolitan Maritime Trading Centres, 1550–1950. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Julia Phillips. 2014. Becoming Ottomans: Sephardi Jews and Imperial Citizenship in the Modern Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark R. 1994. Under Crescent and Cross the Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duka, Ferit. 2009. Coast and Hinterland in the Albanian lands (16th–18th centuries). In Enthalten in Balcani Occidentali, Adriatico e Venezia fra XIII e XVIII Secolo/Der Westliche Balkan, der Adriaraum und Venedig (13.–18. Jahrhundert). Edited by Gherardo Ortalli and Olıver Jens Schmıtt. Wien: OAW, pp. 261–70. [Google Scholar]

- Emecen, Feridun. 1996. From Selanik to Manisa: Some Information about the Immigration of the Jewish weavers. In The Via Egnatia under Ottoman Rule (1380–1699). Edited by Elizabeth Zachariadou. Rethymnon: Crete University Press, pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Emecen, Feridun. 1997. Unutulmuş Bir Cemaat Manisa Yahudileri. İstanbul: Eren Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- Ercan, Yavuz. 2001. Osmanlı Yönetiminde Gayrimüslimler: Kuruluştan Tanzimat’a Kadar Sosyal, Ekonomik ve Hukukî Durum. Ankara: Turhan Kitabevi. [Google Scholar]

- Ertuğ, Nejdet. 2015. Osmanlıda Kefalet Sistemi ve Esnaf Birlikleri Uygulaması. Türk Kültürü İncelemeleri Dergisi 32: 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Erünsal, İsmail. 2018. Osmanlı Mahkemelerinde Şâhitler: Şuhûdü’l-’udûlden Şuhûdü’l-hâle Geçiş. Osmanlı Araştırmaları 53: 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryılmaz, Bilal. 1992. Osmanlı Devleti’nde Millet Sistemi. İstanbul: Ağaç Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, Malte. 2020. Port Cities of the Eastern Mediterranean: Urban Culture in the Late Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Güner, Yasemin. 2007. Ortaçağ Avrupa’sında Yahudi Göçleri ve Yahudi Kültürü. Master’s thesis, Celal Bayar University, Manisa, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Joseph R. 2017. Jews in the Ottoman Empire (1580–1839). In The Cambridge History of Judaism. Edited by Jonathan Karp and Adam Sutcliffe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 831–63. [Google Scholar]

- İnalcık, Halik. 2002. Foundation of Ottoman Jewish Cooperation. In Jews, Turks, Ottomans: A Shared History, Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Century. Edited by Avigdor Levy. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- İnalcık, Halil. 1987. Hicri 835 Tarihli Suret-i Defter-i Sancak-i Arvanid. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- İnalcık, Halil. 2008. Makaleler II. Ankara: Doğu Batı Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Ronald Carlton. 1993. Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World, 1571–1640. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Ronald Carlton. 2011. Studies on Ottoman Social History in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries: Women, Zimmis and Sharia Courts in Kayseri, Cyprus and Trabzon. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, Filiz. 2007. Pişkeş. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, vol. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Karagedikli, Gürer. 2011. In Search of a Jewısh Communıty in the Early Modern Ottoman Empıre: The Case of Edirne Jews (C. 1686–1750). Master’s thesis, Department of History, İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Karagedikli, Gürer. 2014. Altın Çağ ile Modern Donem Arasında Osmanlı Yahudileri: Edirne Yahudi Cemaati Örneği (1680–1750). Kebikeç 19: 305–36. [Google Scholar]

- Karagedikli, Gürer. 2018. Overlapping Boundaries in the City: Mahalle and Kahal in the Early Modern Ottoman Urban Context. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 61: 650–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyder, Çağlar, Eyüp Özveren, and Donald Quataert. 1993. Port-cities in the Ottoman Empire: Some Theoretical and Historical Perspectives. Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 16: 519–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kiel, Machiel. 1991. Avlonya. In TDV İslam Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, vol. 4, pp. 118–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, Menderes. 2023. Physician and diplomat in Ottoman palace: Solomon Ben Nathan Ashkenazi. Journal of Medical Biography 32: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Bernard. 1996. Cultures in Conflict: Christians, Muslims, and Jews in the Age of Discovery. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loker, Zvi. 1989. Spanis and Portuguese Jews Amongst the Southern Slaves—Their Settlement and Consolidation during the Sixteenth and Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. In Sephardi Heritage. Edited by Richard D. Barnett and William M. Schwab. Grendon: Gibraltar Books, vol. II, pp. 283–313. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, Bruce. 2001. Cristians and Jews in the Ottoman Arab World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mazower, Mark. 2006. Salonica City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews (1430–1950). New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Molho, Rena. 1993. Education in the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki in the Beginning of the Twentieth Century. Balkan Studies 34: 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolay, Nikolas de. 2014. Muhteşem Süleyman’ın İmparatorluğunda. Edited by Marie-Christine Gomez-Geraud and Stefanos Yerasimos. Translated by Şirin Tekeli, and Menekşe Tokyay. İstanbul: Kitap Yayınevi. [Google Scholar]

- Ortaylı, İlber. 2001. Kadı. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi. İstanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, vol. 24, pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Oslon, Robert W. 1977. Jewish in the Ottoman Empire and Their Role in Light of New Documents. Tarih Enstitüsü Dergisi 7–8: 119–44. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, Ahmet. 2019. Yahudilerin Osmanlı İmparatorluğuna Gelişi ile Türkiye Cumhuriyeti’nin İlan Edildiği Tarihsel Sürece Kadar SosyoKültürel ve Ekonomik Durumların Araştırılmasına Yönelik Tarihsel Bir Yaklaşım. Çanakkalae Onsekiz Mart Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 14: 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada, Miguel-Angel Ladero. 1991. Mudéjares and repobladores in the Kingdom of Granada (1485–1501). Mediterranean Historical Review 6: 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozen, Mina. 2011. Osmanlı Yahudileri. In Türkiye Tarihi 1603–1839: Genç Osmanlı İmparatorluğu. Edited by Suraiya Faroqhi. Translated by Fethi Aytuna. İstanbul: Kitap Yayınevi. [Google Scholar]

- Rozen, Minna. 2002. A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul: The Formative Years, 1453–1566. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman, David B. 2010. Early Modern Jewry: A New Cultural History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seferova, Günay. 2022. Osmanlı Döneminde Yahudilerin Altın Çağı. In XVII. Türk Tarih Kogresi. Kongeye Sunulan Bildiriler 1–5 Eylül 2018. Edited by Semiha Nurdan and Muhammed Özler. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları, vol. III, pp. 563–80. [Google Scholar]

- Şeyban, Lütfi. 2010. Mudejares ve Sefarades: Endülüslü Müslüman ve Yahudilerin Osmanlı’ya Göçleri. İstanbul: İz Yayıncılık. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Stanford. 1991. The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and Turkish Republic. London: Macmillian. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Stanford. 1999. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Yahudi Milleti. In Osmanlı Ansiklopedisi/Toplum. Ankara: Yeni Türkiye Yayınları, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Taş, Hülya. 2008. Osmanlı Kadı Mahkemesindeki ‘Şühûdü’l-Hâl’ Nasıl Değerlendirilebilir? Bilig 44: 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tokel, Meliha. 2010. Tarihte ve Günümüzde Edirne Yahudi Cemaati. Master’s thesis, Marmara University, Istanbul, Türkiye. [Google Scholar]

- Veinstein, Gilles. 1987. Une Communaute Ottomane: Les Juifs D’avlonya (Valona) Dans La Deuxieme Moitie Du Xvie Siecle. In Gli Ebrei E Venezia secoli XIV–XVIII (Les Juifs à Venise, xve -xixe siècle). Edited by Gaetano Cozzi. Milan: Edizioni di Comunità, pp. 781–828. [Google Scholar]

- Veinstein, Gilles. 1996. Avlonya (Vlorë), une étape de la voie Egnatia dans la seconde moitié du XVIe siècle? In The Via Egnatia under Ottoman Rule (1380–1699). Edited by Elizabeth Zachariadou. Rethymnon: Crete University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Veinstein, Gilles. 2009. L’établissement des Juifs d’Espagne dans l’Empire ottoman (fin XVe–XVIIe): Une migration. In Le monde de l’itinérance en Méditerranée de l’Antiquité à l’époque moderne: Procédures de contrôle et d’identification. Edited by Claudia Moatti, Wolfgang Kaiser and Christophe Pébarthe. Bordeaux: Ausonius. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariadou, Elizabeth. 1996. The Via Egnatia under Ottoman Rule (1380–1699). Rethymnon: Crete University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Quarters | Households |

| Şeyamcalto | 128 |

| Eski İpsiyonat | 100 |

| Aşçalu | 19 |

| Kalavres | 15 |

| Yahudi İsak | 17 |

| Mayta veled-i Musa | 41 |

| Kazleşet | 9 |

| Mezsimeztik? | 27 |

| İsak veled-i Setrika | 13 |

| Boska veled-i Musa veled-i Selmo | 12 |

| Communities | Households |

| Selmo veled-i Harun ann Cemaat-i Otranto | 56 |

| Cemaat-i Portugale Yahudiyan | 14 |

| Cemaat-i Portugale Yahudiyan | 63 |

| Total | 5282 |

| Craftmanship | |

|---|---|

| Jewish | Muslims |

| Butcher | Butcher |

| Merchant | Merchant |

| Real Estate Buying and Selling | Farrier |

| Saltpeter Master | Culinary |

| Textile Weaving | Saddlemaker |

| Usury | Barber |

| Fishery Management | Candlestick Maker |

| Calligrapher | |

| Clockmaker | |

| Rug Weaver | |

| Cotton Fluffer | |

| Bath Attendant | |

| Stallholder | |

| Shoemaker | |

| Shepherd | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kerim, M.; Aktaş, F.M.; Kurt, M. Community Relations in the Ottoman Balkans of the Suleymanic Age: The Case of Avlonya (1520–1568). Religions 2024, 15, 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121443

Kerim M, Aktaş FM, Kurt M. Community Relations in the Ottoman Balkans of the Suleymanic Age: The Case of Avlonya (1520–1568). Religions. 2024; 15(12):1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121443

Chicago/Turabian StyleKerim, Mehmet, Furkan Mert Aktaş, and Menderes Kurt. 2024. "Community Relations in the Ottoman Balkans of the Suleymanic Age: The Case of Avlonya (1520–1568)" Religions 15, no. 12: 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121443

APA StyleKerim, M., Aktaş, F. M., & Kurt, M. (2024). Community Relations in the Ottoman Balkans of the Suleymanic Age: The Case of Avlonya (1520–1568). Religions, 15(12), 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121443