Shared Memory and History: The Abrahamic Legacy in Medieval Judaeo-Arabic Poetry from the Cairo Genizah

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Genizah’s Arabic Poetry and Jewish–Islamic Interculturality

3. Celebrating Abrahamic Legacy in Judaeo-Arabic Poetry from the Cairo Genizah

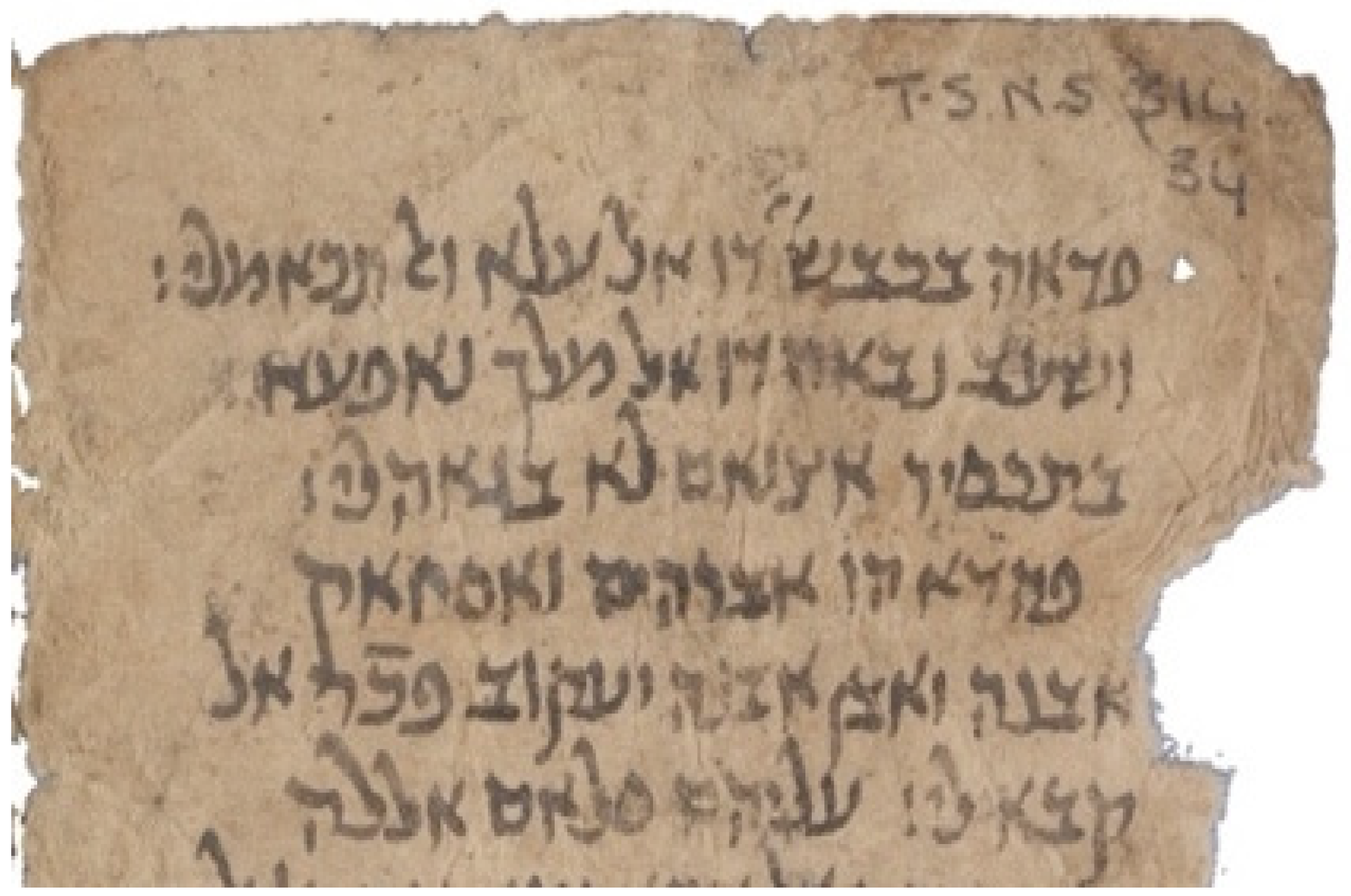

On the recto (Figure 1), it continues celebrating Abraham’s legacy and reads:ונחן בני אסראיל ואלסיד אלדי (ونحن بني اسرايل والسيد الدي )“We are Israelites (nation of Israel), and the master whom”

| Arabic Transcript فداه بكبش دو العلا والتكاملي: وشعب نباه دو الملك نافعا بتكسير اصنام لا بجاهلي: فهدا هو إبراهيم واسحاق ابنه وابن ابنه يعقوب فخر الـ قبالي: عليهم سلام الله | Judaeo-Arabic Script פדאה בכבש דו אל עלא ואל תכאמלי : ושעב נבאה דו אלמלך נאפעא בתכסיר אצנאם לא בגאהלי: פהדא הו אבראהים ואסחאק אבנה ואבן אבנה יעקוב פכֿר אל קבאלי:עליהם סלאם אללה |

| Translation: He, Almighty and excelled, sacrificed a sheep for him: And we are the nation whom the Lord elevated for the good by destroying idols, not through idolatry. This is Abraham (Ibrāhīm) and Isaac, His son (Son of Abraham), and his grandson Jacob, the pride of the Tribes: God’s/Allah’s Peace be upon them | |

| أَبُنَيَّ إِنّي نَذَرتُكَ لِلَّهِ شَحيطاً ، فَاِصبِر فِدىً لَكَ حالي

أَجابَ الغُلامُ أَن قالَ فيهِ، كُلُّ شَيٍ لِلَّهِ غَيرُ اِنتِحالِ أَبُتي إِنَّني جَزَيتُكَ بِالَّلهِ تَقيّاً، بِهِ عَلى كُلِ حالِ فَاِقضِ ما قَد نَذَرتَ لِلَّهِ وَاَكفُف، عَن دَمي أَن يَمَسُّهُ سِربالي وَاِشدُد الصَفدَ لا أَحيدَ عَن، السِكّينِ حَيدَ الأَسيرِ ذي الأَغلالِ إِنَّني آلَمُ المَحَزَّ وَإِنّي، لا أَمَسُّ الأَذقانَ ذاتَ السِبالِ وَلَهُ مُديَةٌ تُخايَلُ في اللَحمِ، حَذامٌ حَنِيَّةٌ كالهِلالِ جَعَلَ اللَهُ جيدَهُ مِن نُحاسٍ، إِذ رَآهُ زَولاً مِنَ الأَزوالِ بَينَما يَخلَعُ السَرابيلَ عَنهُ، فَكَّهُ رَبُّهُ بِكَبشٍ جُلالِ | .14 .15 .16 .17 .18 .19 .20 .21 .22 |

| (Ibn Abī al-Ṣalt 2024, pp. 14–22). | |

| Translation: | |

| |

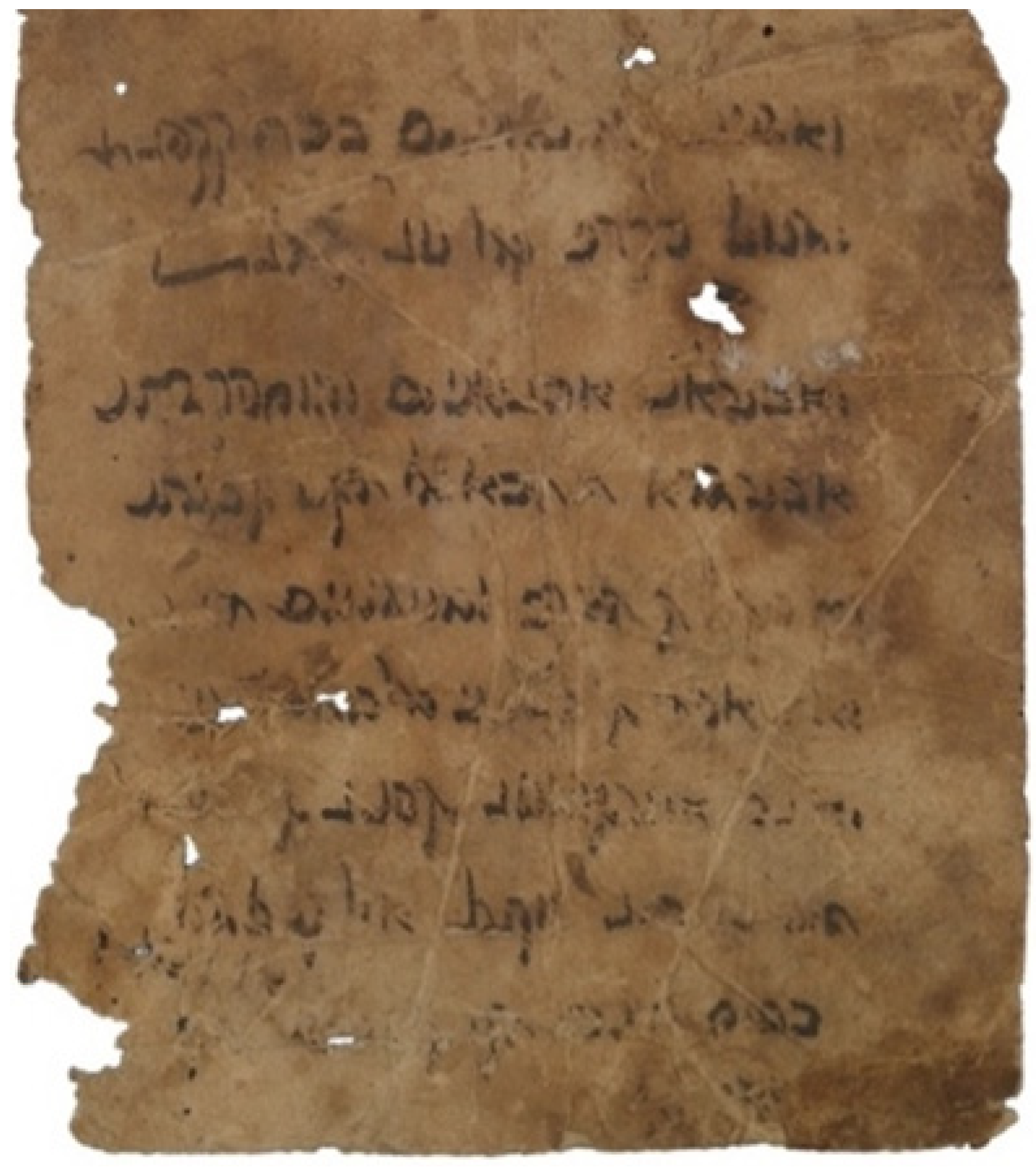

| Arabic Transcript والله شرفهم بما لم عليه لمخبر في العاجل وال اجلي: الا لعقبهم الدي يحبهم وفداهم بفضايل ونوايلي : انصت لفخر يترك القلب مولها وينشب نارا في الضلوع الـ دواخلي: | Judaeo-Arabic Script ואללה שרפהם במא לם עליה למכבר פי אל עאגל ואל אגלי: אלא לעקבהם אלדי יחבהם ופדאהם בפצֹאיל ונואילי: אנצת לפכר יתרך אלקלב מולהא וינשב נארא פי אלצֹלוע אל דואכלי |

| Translation: and Allah [God] honored them with what was never given to a messenger in early or later times (in all times) except only for those who succeeded them, who love them and who sacrificed them with virtues and generous bestowal (of God): You should listen to the glory/pride that leaves the heart ardently in love and causes a burning Fire inside the chest: | |

| Arabic Transcript ايا علي شاطيه عدد الـ […] مخايلي : الم يوكز الـ قبطي موسی بوزخه فغاص كمو تورن هوا | Judaeo-Arabic Script איא עלי שאטיה עדד אל[…] מכאילי : אלם יוכז אל קבטי מוסי בוזכֿהﹰ פגֿאץ כמו תורן הוא |

| Translation […] on its shore [the Nile], the number of signs. Did not Moses torment the Copt (Egyptian) so he (the Copt) fell like a bull, … | |

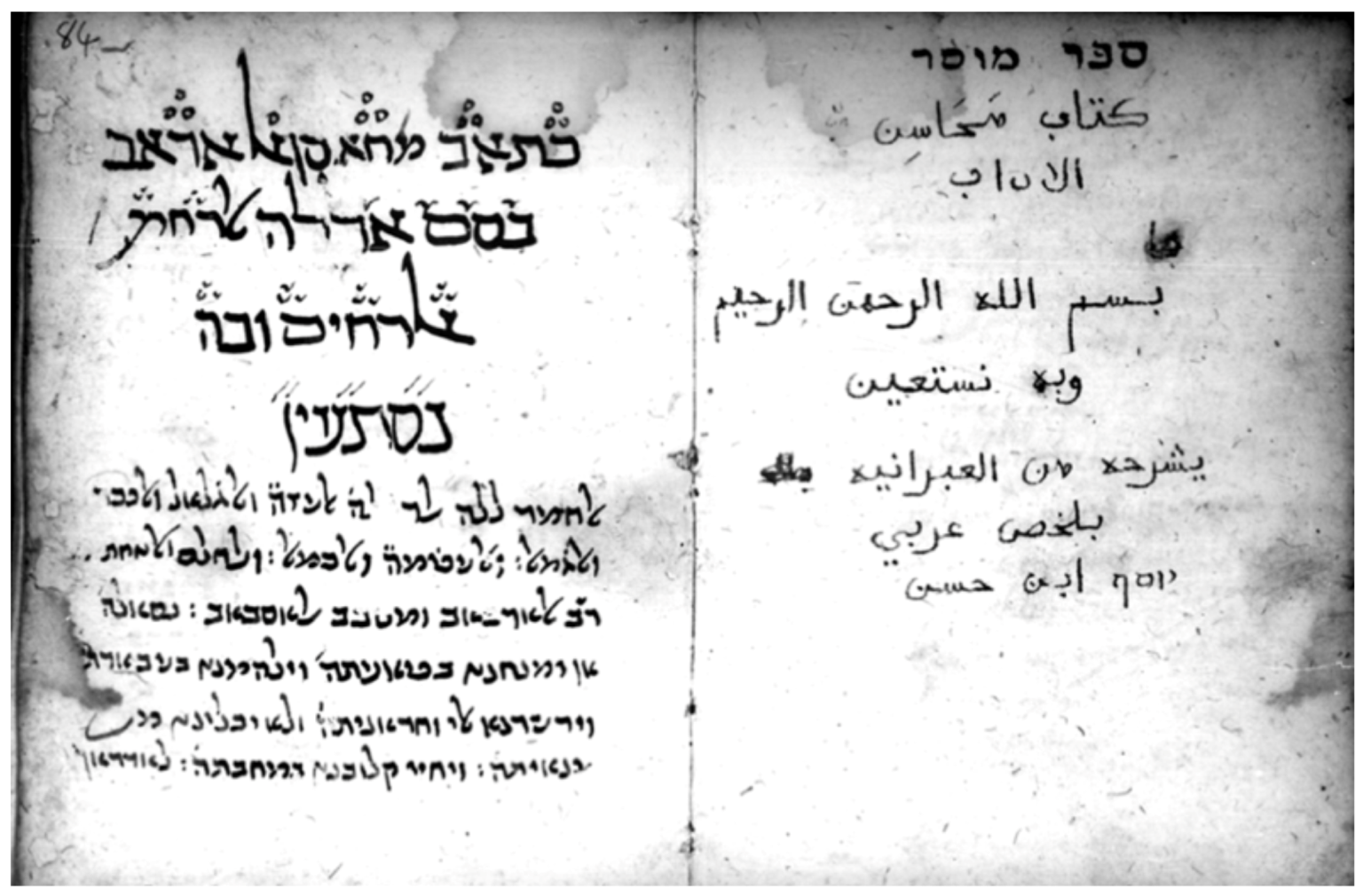

| Arabic Transcript [……………..] بسيط عربي علي ال שיר […]יר זולתך אין לי קצין או גביר يا رب انت الواحد الفرد الصمد [………………..] وا[…] العالم ومحصيهم عدد اختصنا شعبا من صالح الكتير واختار إبراهيم وهو طفل صغير يصحق (اسحاق)خلصه من حد العدا واضحـ[ه] [ملاك هالوهـ]ـيم كبش للفدا | Judaeo-Arabic Script [………………..] בסיט ערבי עלי אל שיר […]יר זולתך אין לי קצין או גביר יא רב אנת אלואחד אלפרד אלצמד [………………..] וא[…] אלעאלם ומחציהם עדד אכתצנא שעבא מן צאלח אלכתיר ואכתאר אבראהים והו טפל צגי יצחק כלאה מן חד אלעדא ואצח[ה] [מלאך האלוה]ים כבש ללפדא |

| Translation A simple (basīṭ) Arabic on the […] A poem [on the model of?] ‘Without you, I have no prince or hero’ Oh Lord/God, you are the Everlasting One, [……….] And the One who [….] the world and makes them numerous (?). He (God) favored us as a nation is to the advantage of many (in the interest of many) And He chose Ibrāhim (Abraham) while he was a young child Isaac, He saved him from the dangerous knife (lit. ‘knife of aggression’) And the Angel of God [provided] a sheep for sacrifice. | |

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | He was born in Middle Egypt in 882 and migrated to Palestine in 915, where he studied under the guidance of Jewish theologian Abu Kathir Yaḥya al-Katib in Tiberias before settling permanently in Abbasid Iraq in 926. In Babylonia, he became a prominent figure in Hebrew literature and the first to write in Arabic extensively. Saadya excelled in Hebrew linguistics, Jewish law, and Jewish philosophy, adhering to the “Jewish Kalam” philosophical school (Stroumsa 2003, pp. 71–90; Scheindlin 1998, pp. 78–80; Cohen 2009, p. 61). |

| 2 | Judah al-Ḥarīzī was born in Toledo in 1165 and translated several Judaeo-Arabic works for Provençal Jewish communities. In 1215, he embarked on a journey to the Islamic East, visiting over 50 Jewish communities in cities such as Jerusalem, Damascus, and Baghdad. He wrote about his travels in Hebrew and Judaeo-Arabic and died in Aleppo in 1225 (Yeshaya 2010a, pp. 1–7). |

| 3 | I express my gratitude to David Torollo, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, for sharing this Manuscript with me, during our APCG project conference at Trinity College Dublin on 19–20 June 2023. |

References

Fragments and Manuscripts

Cambridge University Library, T-S AS 153.44Cambridge University Library, T-S NS 314.34Cambridge University Library, T-S AS 151.91Cambridge University Library, T-S NS 289.5bBodleian Library-University of Oxford, MS. Hunt. 488. Kitāb mahāsin al-ʼādāb, f 84–160.Secondary Sources

- Adler, Elkan, ed. and trans. 1987. Jewish Travellers in the Middle Ages. 19 Firsthand Accounts. New York: Dover Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sakhāwī, Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān. 1937. Al-Ḍawʾ al-Lāmiʿ li-Ahl al-Qarn al-Tāsiʿ. Cairo: Maktabat al-Quds, vol. 1, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sakhāwī, Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān. 2002. Kitāb al-Tibr al-Masbūk fī Dhayl al-Sulūk. Edited by Najwá Muṣṭafā. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣrīyah, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman-Lieberman, Phillip. 2014. The Business of Identity: Jews, Muslims, and Economic Life in Medieval Egypt. Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, Rachel. 2010. The Authority of Pirqe De-Rabbi Eliezer. In The Return of the Repressed. Leiden: Brill, pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Mohamed A. H. 2018. An Initial Survey of Arabic Poetry in the Cairo Genizah. Al-Masaq 30: 212–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almbladh, Karin. 2010. The Basmala in medieval letters in Arabic written by Jews and Christians. Orientalia Suecana LIX: 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Stephen J. 1990. Abraham. In Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Edited by Mills Watson and Roger Bullard. Macon: Mercer University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Colin F., and Meira Polliack. 2001. Arabic and Judaeo-Arabic Manuscripts in the Cambridge Genizah Collections: Arabic Old Series (T-S Ar. 1a-54). Cambridge University Library Genizah Series 12; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baning, Jelle. 2018. The Rise of a Capital: Al-Fusṭāṭ and Its Hinterland, 18/639–132/750. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bareket, Elinoar. 2017. Eli Ben Amram and His Companions: Jewish Leadership in the Eleventh-Century Mediterranean Basin. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beeri, Tova. 2012. Piyyuṭ. In The Cambridge History of Judaism. Edited by Phillip I. Lieberman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 5, pp. 780–95. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, Louis A. 1997. The Akedah: The Binding of Isaac. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, Michael, and Elizabeth Fentress. 2017. The Fatimid Empir. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, Heribert. 1998. Islam, Judaism, and Christianity: Theological and Historical Affiliations. Princeton: Wiener Markus. [Google Scholar]

- Cachia, Pierre. 1977. The Egyptian Mawwāl: Its Ancestry, Its Development and Its Present Forms. Journal of Arabic Literature 8: 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Mark R. 1980. Jewish Self-Government in Medieval Egypt: The Origins of the Office of Head of the Jews, ca. 1065–1126. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark R. 1999. What Was the Pact of ‘Umar? A Literary-Historical Study. Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 23: 100–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark R. 2006. Geniza for Islamicists, Islamic Geniza and the ‘New Cairo Geniza’. Harvard Middle Eastern and Islamic Review 7: 129–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark R. 2009. The ‘Convivencia’ of Jews and Muslims in the High Middle Ages. In The Meeting of Civilizations: Muslim, Christian, and Jewish. Edited by Moshe Ma‘oz. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Israel. 1970. Thesaurus of Mediaeval Hebrew Poetry, with the assistance of Jefim Schirmann, 1904–1981. New York: Ktav Pub. House. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Israel. 2017. Thesaurus of Mediaeval Hebrew Poetry. 4 vols. Reprinted and introduced by Michael Rand. Kiraz Jewish Studies Archive. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, Carol. 2017. The Seeds of Kinship Theory in the Abrahamic Religions. In New Directions in Spiritual Kinship: Sacred Ties Across the Abrahamic Religions. Edited by In Todne Thomas, Asiya Malik and Rose Wellman. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 245–62. [Google Scholar]

- Drory, Rina. 2000. Models and Contacts: Arabic Literature and Its Impact on Medieval Jewish Culture. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2023. Copt. Encyclopedia Britannica. October 2. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Copt (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Firestone, Reuven. 1990. Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Godsell, Sarah. 2019. Poetry as Method in The History Classroom: Decolonising Possibilities. Yesterday and Today, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, Shelomo D. 1949. On Jewish-Arab Symbiosis. Molad 2: 259–66. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, Shelomo D. 1955. The Cairo Geniza as a Source for the History of Muslim Civilisation. Studia Islamica 3: 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goitein, Shelomo D. 1967–1993. Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. 6 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, Shelomo D. 2005. Jews and Arabs: A Concise History of Their Social and Cultural Relations, 4th ed. Mineola: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, Shelomo D., and Mordechai Friedman. 2007. India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, Sami A. 1967. The Mawwāl in Egyptian Folklore. The Journal of American Folklore 80: 182–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkamp, Alfred. 2004. The Jews of Europe in the Middle Ages: By Way of Introduction. In The Jews of Europe in the Middle Ages (Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries). Edited by Christoph Cluse. Cultural Encounters in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages 4. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Hendel, Ronald. 2005. Remembering Abraham: Culture, Memory, and History in the Hebrew Bible. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, Hartwig. 1903. The Arabic Portion of the Cairo Genizah at Cambridge. The Jewish Quarterly Review 15: 167–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, Hartwig. 1905. The Arabic Portion of the Cairo Genizah at Cambridge: A Poem Attributed to Al Samau’al. The Jewish Quarterly Review 17: 431–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Aaron. 2012. Abrahamic Religions: On the Uses and Abuses of History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥusayn, Ṭāhā. 1927. Fī al-adab al-Jāhilī. Miṣr. Cairo: Maṭbaʻat al-Iʻtimād. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Abī al-Ṣalt. 2024. Iṣbir al-Nafsī ʿinda Kull Malamm. Aldiwan.net. Available online: https://www.aldiwan.net/poem36167.html (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Ibn ʿĀdiyā, Al-Samawʾal. 2024. Āla ʾayyuhā al-Ḍayfu alladhī ʿāba Sādatī. Aldiwan.net. Available online: https://www.aldiwan.net/poem1202.html (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Jefferson, Rebecca. 2022. The Cairo Genizah and the Age of Discovery in Egypt. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Robin M. 1993. The Binding or Sacrifice of Isaac: How Jews and Christians See Differently. Bible Review 9: 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Keeler, Annabel. 2005. Moses from a Muslim perspective. In Abraham’s Children: Jews, Christians and Muslims in Conversation. Edited by Norman Solomon, Richard Harries and Timothy Winter. London and New York: T&T Clark, pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Geoffrey. 2016. Judeo-Arabic. In Handbook of Jewish Languages. Edited by Lily Kahn and Aaron D. Rubin. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 22–63. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Geoffrey. 2007. Judaeo-Arabic. In Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 526–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kolta, Kamal Sabri. 1985. Christentum im Land der Pharaonen: Geschichte und Gegenwart der Kopten in Ägypten. München: J. Pfeiffer, pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Geoffrey. 1993. Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents in the Cambridge Genizah Collections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuschel, Kari-Josef. 1995. Abraham: A Symbol of Hope for Jews, Christians and Muslims. London: SCM. [Google Scholar]

- Langermann, Y. Tzvi. 1996. Arabic Writings in Hebrew Manuscripts: A Preliminary Relisting. Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 6: 137–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavee, Moshe. 2013. Literary Canonization at Work: The Authority of Aggadic Midrash and the Evolution of Havdalah Poetry in the Genizah. AJS Review 37: 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus-Yafeh, Hava. 1992. Intertwined Worlds: Medieval Islam and Bible Criticism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, Jon D. 2012. Inheriting Abraham: The Legacy of the Patriarch in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Bernard. 1984. The Jews of Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, Laura S. 2013. Piyyut (Jewish liturgical and secular poetry). In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Edited by Roger S. Bagnall, Kai Brodersen, Craige B. Champion, Andrew Erskine and Sabine R. Huebner. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, vol. 28, pp. 5341–43. [Google Scholar]

- Luṭf, ‘Umar Muṣṭafā. 2019. Al-Ḥayāt al-Taʻlīmiyah li-Yahūdu Miṣr fī al-ʻaṣr al-Islāmī. Cairo: Al-Hayʼah al-ʻĀmmah al-Miṣrīyah. [Google Scholar]

- Mikhail, Maged S. A. 2021. Historical definitions and synonyms for “Copt” and “Coptic”. Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 13: 11–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimonides, Moses. 2002. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated from the Original Arabic by M. Friedländer. Illinois: Varda Books. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, Donald. 2007. Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed: Silence and Salvation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Udovitch, Abraham. 1970. Partnership and Profit in Medieval Islam. Princeton Studies on the Near East. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perlmann, Moshe. 1964. Samauʿal al-Maghribī, Ifḥam al-Yahūd Silencing the Jews. Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 32: 5–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Francis. 2018. The Children of Abraham: Judaism, Christianity, Islam, 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qāsim, Qāsim ʻAbdu. 1993. Al-Yahūd fī Miṣr. Cairo: Dar al-Shurūq. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, Michael. 2013. Paytanic Hebrew. In Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. Edited by Geoffrey Khan. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, Stefan C. 2002. The Cairo Genizah: A Medieval Mediterranean Deposit and a Modern Cambridge Archive. Libraries & the Cultural Record 37: 123–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sasser, Tyler. 2017. The Binding of Isaac: Jewish and Christian Appropriations of the Akedah (Genesis 22) in Contemporary Picture Books. Children’s Literature 45: 138–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheindlin, Raymond P. 1998. A Short History of the Jewish People: From Legendary Times to Modern Statehood. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer, Menahem. 1997. The Contribution of the Genizah to the Study of Liturgy and Poetry. Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 63: 163–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, Peter. 2010. Al-Fustat and the Making of Old Cairo. In Babylon of Egypt: The Archaeology of Old Cairo and the Origins of the City. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, Adam J., and Guy G. Stroumsa, eds. 2015. The Oxford Handbook of the Abrahamic Religions. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Simonson, Harold P. 1970. Writing through Literature. College Composition and Communication 21: 139–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Norman, Richard Harries, and Tim Winter, eds. 2005. Abraham in Jewish, Christian and Muslim Thought. In Abraham’s Children: Jews, Christians and Muslims in Conversation. London and New York: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Steinschneider, Moritz. 1900. An Introduction to the Arabic Literature of the Jews. The Jewish Quarterly Review 12: 602–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillman, Norman A. 2018. The Jews of the Medieval Islamic West: Acculturation and Its Limitations. The Journal of the Middle East and Africa 9: 294–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillman, Yedida K. 1976. The Importance of the Cairo Geniza Manuscripts for the History of Medieval Female Attire. International Journal of Middle East Studies 7: 579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroumsa, Sarah. 2003. Saadya and Jewish Kalam. In The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Jewish Philosophy. Edited by Daniel Frank and Oliver Leaman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Stroumsa, Sarah. 1995. On Jewish Intellectuals Who Converted in the Early Middle Ages. In The Jews of Medieval Islam. Edited by Daniel Frank. Études sur le judaïsme médiéval. Leiden: Brill, vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Tobi, Yosef. 2010. Between Hebrew and Arabic Poetry. Studies in Spanish Medieval Hebrew Poetry. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Esther-Miriam. 2010. Linguistic Variety of Judaeo-Arabic in Letters from the Cairo Genizah. Etudes sur le Judaisme Medieval 41. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1953. Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yadgar, Liran. 2016. All the Kings of Arabia Are Seeking Your Counsel and Advice: Intellectual and Cultural Exchange Between Jews and Muslims in the Later Middle Islamic Period. Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Yeshaya, Joachim. 2010a. Medieval Hebrew Poetry in Muslim Egypt: The Secular Poetry of the Karaite Poet Moses Ben Abraham Dar’i. Karaite Texts and Studies 3. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Yeshaya, Joachim. 2010b. Your Poems Are Like Rotten Figs: Judah al-Ḥarīzī on Poets and Poetry in the Muslim East. In Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk Eras VI. Edited by Urbain Vermeulen and Kristof d’Hulster. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 143–52. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sheir, A.M. Shared Memory and History: The Abrahamic Legacy in Medieval Judaeo-Arabic Poetry from the Cairo Genizah. Religions 2024, 15, 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121431

Sheir AM. Shared Memory and History: The Abrahamic Legacy in Medieval Judaeo-Arabic Poetry from the Cairo Genizah. Religions. 2024; 15(12):1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121431

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheir, Ahmed Mohamed. 2024. "Shared Memory and History: The Abrahamic Legacy in Medieval Judaeo-Arabic Poetry from the Cairo Genizah" Religions 15, no. 12: 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121431

APA StyleSheir, A. M. (2024). Shared Memory and History: The Abrahamic Legacy in Medieval Judaeo-Arabic Poetry from the Cairo Genizah. Religions, 15(12), 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121431