Abstract

The establishment of the United Church of Christ in Japan (nihon kirisuto kyōdan 日本基督教団) marked the culmination of the Church Union Movement in Imperial Japan. Although the Church Union Movement can be traced back to the Meiji era, no significant breakthroughs were made until 1939 due to the refusal of some denominations. In this article, I aim to clarify the process and causes behind the formation of the united church, while also attempting to understand the interaction pattern between the State and Christianity under an increasing wartime totalitarian regime. In April 1939, the Diet passed the Religious Organizations Law (syūkyō dantai hō 宗教団体法), a bill aimed at strengthening state control over religions, which required Christian denominations to establish religious organizations. With the war intensifying Japan’s antagonism toward Western countries, Christianity as a foreign religion faced progressive attacks from the nationalist sects. Some denominations, like the Salvation Army, were accused of espionage due to their international connections and were monitored by gendarmerie (kenpeitai 憲兵隊). Facing harsh pressure, Christians sought to project a patriotic image, ultimately leading to the formation of the United Church as a survival strategy amidst a hostile social-political environment.

1. Introduction: Current Research and Issues

The United Church of Christ in Japan (abbr. UCCJ, nihon kirisuto kyōdan 日本基督教団), the largest Protestant denomination in contemporary Japan, was established on 24 June 1941, the eve of the outbreak of the Pacific War. It was formed by merging 33 diverse Protestant denominations into a united church, which became the only legally recognized Protestant organization in Japan at the time. Despite the influence of ecumenism, which led to the creation of the National Christian Council of Japan (abbr. NCCJ, nihon kirisutokyō renmei 日本基督教連盟), a united church had not materialized before that time. This was due to the persistent adherence of various denominations to their own traditional practices and faith exegesis, which had hindered the possibility of them merging. However, in April 1939, the National Diet passed the Religious Organizations Law (syūkyō dantai hō 宗教団体法), which required Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian denominations to establish eligible religious organizations. Meanwhile, as Japanese nationalism reached its peak and society moved toward totalitarianism, the social-political environment for Christianity, as a foreign religion, became increasingly adverse.

The current literature on the Church Union Movement and the establishment of the UCCJ can be categorized into three types. Firstly, the NCCJ and UCCJ compiled and organized corresponding records and documents regarding these events. In 1941, the NCCJ published a book titled the 2600th Year of Imperial Calendar and Church Union, which provided a detailed account of the preparation and proceedings of the previous year’s “All-Christian’s Conference”, where the Christian community announced the establishment of a united church and reported on the progress of the Church Union efforts at the time (Miyakoda 1941). The Christian Yearbook published in the same year also documents the conference’s declaration on the Church Union (Nihon 1994b). The UCCJ published a historical archive of its own institution, with the first volume focusing on the process of its establishment. This volume not only includes records of preparatory meetings for the foundation of the UCCJ, but also contains resolution documents from various denominations regarding their responses to the united church (UCCJ 1997).

Secondly, some researchers consider the Church Union Movement as part of a series of events within the broader history of Christianity during wartime or under the Emperor system (tennōsei 天皇制), rather than conducting an independent analysis of the movement itself. There are two perspectives, specifically, regarding the establishment of the UCCJ: one is the view expressed in the church’s constitution, which states that “evangelical churches of over thirty formerly existing, independent denominations, as well as churches of other traditions in our country, through a unity given in the Holy Spirit under the wondrous providence of God, and having respect for one another’s unique historical characteristics, entered into the fellowship of the holy catholic Church. The Church thus formed is the United Church of Christ in Japan (UCCJ 1994)”; the other perspective sees its establishment as a result of the Religious Organizations Law, which aimed to bring religions under state control (Dohi 2012, pp. 455–58, 468–71; Kainō 2015, pp. 27–52; Toyogawa 2017, pp. 159–83). The latter perspective has gradually become the foundation for academic understanding of the issue of war responsibility concerning Japanese Protestant churches, including the UCCJ (Hara 2005, p. 73). Moreover, scholars who hold this view argue that, to some extent, the establishment of the UCCJ represents a “history of failure” for the Protestant Church. Dohi, for instance, makes the following argument: “Under the Emperor system’s wartime policies, as state power promoted the control and integration of all organizations, functions, and ideologies to achieve its wartime objectives … the church, at times, forced but at other times willingly, aligned itself with the state’s policies and chose the path of Church Union, leading to the formation of UCCJ. In this sense, the history of UCCJ is a ‘history of failure’, as it represented the church’s loss of its foundational identity (Dohi 1975, p. 265)”. However, naturally, the problems of the Protestant churches’ cooperation in the war, as well as their war responsibility, are not the focus of this paper. The Emperor System and Christianity during the Fifteen-Year War, compiled by the Tomisaka Christian Center, extends the timeframe of the war back to 1931 and examines the relationship between various denominations and the state, while the recognition of the Church Union and the Religious Organizations Law emerged as an issue that no denomination could avoid (Tomisaka 2007). In particular, Dohi’s article focuses on the initiatives of NCCJ, exploring how the Christian community responded to the increasingly restricted space for religious activities during the so-called “rush hour of Emperor system” (Dohi 2007, pp. 95–130). Furthermore, Toyogawa articulates that the Church Union Movement was, on the one hand, a response to the construction of the wartime system and, on the other hand, an initiative by the Ministry of Education intended to foster the establishment of “Japanese Christianity” that would be integrated with the Emperor system, thereby promoting the unification of the church and state into a single entity (Toyogawa 2017, pp. 175–81).

Thirdly, other researchers focus on the individual contributions of church leadership at the time in relation to the Church Union Movement. Ochiai analyzes the founding motivations behind the formation of NCCJ, examines the perspectives of its leader, Ebisawa Akira 海老沢亮, on the Church Union Movement, and also explores Ebisawa’s proposals for advancing this movement and the context of UCCJ’s “doctrinal summary (kyōgi no taiyō 教義の大要)” as well as “guidelines for living (seikatu kōryō 生活綱領)” (Ochiai 2013, pp. 1–12; 2017). Endō studies the wartime activities of Tagawa Daikichirō 田川大吉郎, another key leader of NCCJ, shedding light on Tagawa’s initiatives and his role in promoting the Church Union Movement (Endō 2007, pp. 131–61).

This paper seeks to study the establishment of the UCCJ as a critical event to address two key issues: (1) the internal conflicts within Protestant denominations regarding the Church Union Movement and (2), more importantly, to explore the social-political pressures encountered by Christian churches as (ultra)nationalism and totalitarianism intensified in Japanese society around 1940. It investigates the reasons for which these denominations chose to respond to such an environment by forming a united church, and it examines the interaction between the State and Christianity, aiming to uncover the underlying patterns of their relationship.

2. Imperial Japan’s 2600th Anniversary and Christians

1940 was considered to mark the 2600th anniversary of the Empire of Japan,1 based on the emperor-centered historiography (kōkoku shikan 皇国史観), the official chronicle. According to this historical narrative, the first emperor, Jimmu, ascended to the throne in 660BC, establishing the “unbroken imperial line (bansei ikkei 万世一系)” that could trace its origin back to the Amaterasu.

2.1. Imperial Japan at Its Apogee

In retrospect, the celebrations that marked that year can be read as an apocalyptic revelry before the epochal collapse of the Empire in 1945; the Japanese held a series of grandiose celebrations in commemoration of Imperial Japan’s twenty-sixth centennial nationwide, which not only presented the outrageous extent of historical continuity attributed to what was a nation-state but also credited the firm stability of the monarchy for its lengthy continuity and unity (Ruoff 2010, p. 1).

Although Imperial Japan showcased its strength and prosperity through spectacular commemoration, the empire had actually been dragged into the quagmire of the Second Sino-Japanese War for the third year, struggling to extricate itself. Just after the unexpected outbreak of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937, the First Konoe Cabinet launched the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement in September, calling for boosting the national spirit and generating a positive popular attitude toward cooperation in carrying out the war effort, as part of the mobilization of the total war machine. The government promoted three patriotic slogans: “solidarity with the population (kyokoku itchi 挙国一致)”, “loyalty to the emperor and self-sacrifice to the nation (jinchū hōkoku 尽忠報国)”, and “perseverance against hardship (kennin jikyū 堅忍持久)” which soon became prevailing nationwide (Seo 1939, p. 26). With the war could not be swiftly concluded, Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro 近衛文麿 issued his second declaration about the war on 3 November 1938, the birthday of Emperor Meiji, proclaiming establishing a “New Order in East Asia (tōa shin chitujo東亜新秩序)”,2 which proposing the tight cooperation in economics, culture, and defense against communism within Japan, China, and the puppet state of Manchukuo, aiming to justify and glorify the aggressive war (Konoe 1938). In the final years of the 1930s, the terms “National Spiritual Mobilization” and “New Order in East Asia” permeated all aspects of social lives, becoming part of everyday language. Additionally, expressing patriotism became a mandatory expectation.

Amidst the grandiose celebration for the 2600th anniversary, Japan’s situation had become increasingly dire and totalitarian. As the war dragged on, domestic politics stagnated, and the economy depressed. Konoe Fumimaro assembled his second cabinet, and in 1940, Japan entered into the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. He introduced the New Regime Movements (shin taisei undō 新体制運動), undermining particracy and establishing the single-party Imperial Rule Assistance Association (taisei yokusankai 大政翼賛会). Labor unions were dissolved, and the Greater Japan Association for Service to the State through Industry (dai nippon sangyō hōkokukai 大日本産業報国会) was created as a subcontracted agency under government labor administration aiming to promote national mobilization while preventing the infiltration of communism (Dohi 2012, p. 457).

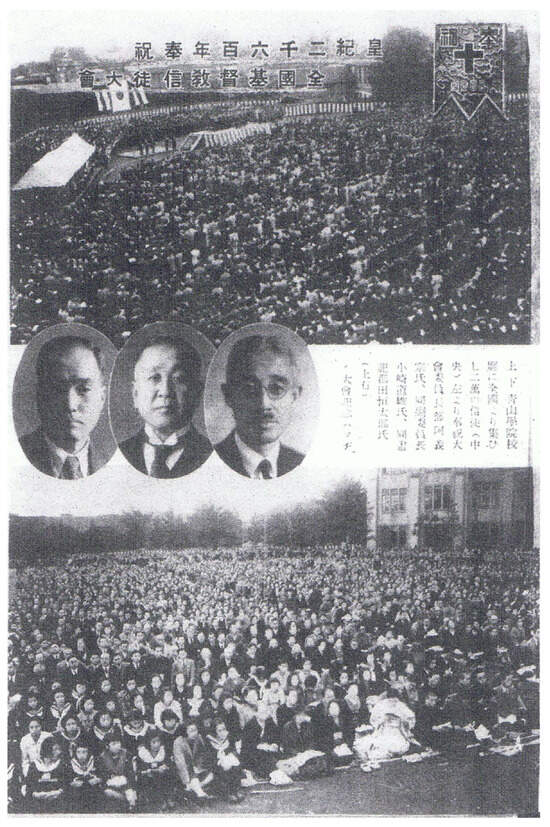

2.2. The All-Christians’ Conference

In addition to grand government-led commemorative ceremonies, various social groups held their own celebrations. On 17 October 1940, during the kannamesai 神嘗祭 (a Shinto festive resurrected after Meiji era), the Christian community in Japan held a “The All-Christians’ Conference, celebrating the 2600th Anniversary of the Founding of the Empire (Figure 1)” at Aoyama Gakuin University. In the initial plan of the conference’s publicity department, the goal was to attract 50,000 people. Not only Christians but also anyone agreeing with the convention’s purpose could participate, with eventually, approximately 20,000 believers and sympathizers from across the empire, colonies, and overseas attending (Miyakoda 1941, p. 29).

Figure 1.

The All-Christians’ Conference, celebrating the 2600th Anniversary of the Founding of the Empire (Miyakoda 1941).

Although it was a Christian convention, many elements of national rituals were incorporated into the agenda, with the opening of the conference presented in a format that blended national and Christian rituals. Firstly, everyone stood to sing the national anthem Kimigayo 君が代, followed by a bow of reverence toward the Imperial Palace (kyūjō yōhai 宮城遥拝), and then a moment of silent prayer was observed (Miyakoda 1941, p. 43). In fact, for a long time, kyūjō yōhai had been viewed as a form of idolatry by the Protestant churches; however, during the late 1930s, as Japan accelerated its path toward (ultra)nationalism and militarism, Christian churches had to knuckle under.3 Since 1967, the UCCJ has designated 11 February, formerly known as kigensetsu 紀元節, which commemorated the ascension of Emperor Jimmu, as “Protect Freedom of Religion Day”, which serves to commemorate the loss of religious freedom due to enforced Emperor worship prewar, as well as to honor the martyrs who gave their lives for this cause (Morishita 2018).

In contrast, the atmosphere of the entire conference was loaded with signs of emperor worship. It was not only exalting the 2600-year chronicle of Imperial Japan as being banpō muhi 万邦無比 (unparalleled by other nations) but also conveying gratitude toward the Emperor and the Empire. The speech of Tomita Mitsuru 富田満, the chairman of NCCJ and the first president of subsequent UCCJ, compared the spirit of Christ’s cross with the “selfless devotion to the nation” spirit advocated in the National Spiritual Mobilization, encouraging Christians to dedicate themselves to the building of the nation (Miyakoda 1941, p. 44). An important way for Christians to contribute to the nation was through the concept of dendō hōkoku 伝道報国 (evangelizing for the nation), which frequently appeared in the Christian press and especially referred to evangelizing in Manchukuo and China. The Japanese Christian community was skillfully combining preaching with patriotism (Kirisutokyōhōsya 1938, p. 1). In a congratulatory message to the conference, Matsuyama Tsunejirō 松山常次郎, a Christian congressman of the Diet, emphasized the fact that evangelizing to the nations of East Asia was a crucial way to support the establishment of New Order in East Asia:

“The construction of the New Order in East Asia and the establishment of peace in the Orient will be achieved through the goodwill cooperation of Japan, Manchukuo, and China. I deeply feel that Christianity is necessary as a spiritual bond in this process. Christians must exert great effort in strengthening domestic evangelism and expanding evangelism throughout East Asia. The 300,000 Christians across the nation must unite their strength and push forward toward this great mission.”(Miyakoda 1941, p. 65)

Furthermore, aside from commemorating the 2600th anniversary, the most important feature of this conference was the proclamation that various Japanese denominations would merge into one united church, which meant that the Church Union Movement was about to see its goal being fulfilled. The conference was centered around Revelation 21:1 “Then I saw ‘a new heaven and a new earth’,” and the vision of “a new heaven and a new earth” repeatedly appeared in various speeches and sermons throughout the conference, symbolizing the new phase filled with hope that would follow the Church Union. In his sermon, Abe Yoshimune 阿部義宗, the former principal of Aoyama Gakuin University and the chairman of this conference committee, asserted that the formation of the Church Union was the manifestation of God’s grace, unique to Japan, and he equaled the event to the revelation of a new heaven and a new earth:

“The mission of Church Union, as the revelation of a new heaven and a new earth for Japanese Christians, is becoming ever more significant. God has raised this new heaven and new earth, but how we realize this Church and how we fulfill the unique mission of the Japanese Church is our responsibility. The mission of the Church, which serves as the spiritual driving force to overcome the critical challenges of fulfilling the destiny of our Japanese people—who, risking the fate of the nation, stand to shoulder the future of East Asia—becomes increasingly crucial.”(Miyakoda 1941, pp. 49–50)

At the conclusion of the conference, “The All-Japan Christian’s Conference’s Proclamation” was reportedly adopted unanimously and read aloud in unison. In addition to praising the perpetual imperial reign and committing to the construction of the New Order in East Asia, the proclamation also declared that all Christians eagerly anticipated the Church Union and the establishment of the united church:

“Faced with a changing world our nation has established a new structure and is pushing forward in building a new order in Greater Eastern Asia. We Christians in instant response, casting aside church and denominational differences and through Church Union and united effort, join in the great task of giving spiritual leadership to the people, in respectfully and loyally assisting the Throne in Government and in rendering service to the nation.We hereby on this Anniversary Day make the following declaration:(a) We pledge ourselves to the task of preaching Christ and fulfilling our mission of saving souls.(b) We pledge ourselves to the achievement of the union of all denominations in one Church.(c) We pledge ourselves to endeavor to raise the level of spiritual living, to lift the standard of morals and to strive for a renewal of the nation’s life.”(NCCJ 1940c, p. 4)

Less than a year after the conference, on 24 June 1941, the United Church of Christ in Japan, which combined 33 denominations, was officially established, marking the culmination of the Church Union Movement. However, the formation of the UCCJ was not an overnight achievement; it involved numerous negotiations, compromises, and practical political considerations, reflecting the long history of the Church Union Movement in Japan.

3. Early Church Union Efforts

After the Perry Expedition, the Catholic Church, led by the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris, was dispatched to Japan in 1859, establishing churches while also engaging in educational, medical, and other philanthropies. Protestant denominations were almost simultaneously transplanted in the latter half of the 19th century, bringing with them their various faith and ritual traditions as they spread into Japan. In the early years, there were understandably few Christian missionaries in Japan, as Christianity remained a prohibited religion until the notices proscribing to Christianity were finally removed in 1873.

3.1. The Ecumenical Movement in Japan

Not having experienced either the Reformation or religious wars, the denominational differences and barriers imported from the West had no significance for the average Japanese Christian (NCCJ 1940b, p. 4). In Hara Makoto’s 原誠 opinion, during the early Meiji era, the primary motivation for converting to Christianity in Japan was often to contribute to the construction of a modern national society through Christianity. Behind this, there was also a desire to assimilate Western culture, driven by a form of cultural intellectualism. In this context, the denomination to which one belonged was not a major concern, and it was rare for someone to consciously convert with full awareness of the specific denomination they were joining (Hara 2005, pp. 74–75). Nevertheless, the Church Union Movement did not develop smoothly.

In fact, during the early years, Protestant missionaries made significant attempts to cooperate with each other to provide a more unified testimony of the Christian faith. “The first Protestant Church in Japan was organized along nondenominational (or transdenominational) lines in 1872 under the leadership of Samuel Robert Brown (Dutch Reformed), James Curtis Hepburn, and James Ballagh (both Presbyterian) (Mullins 1998, p. 13)”. This first Church was named the Church of Christ in Japan (nihon kirisuto kōkai 日本基督公会), deliberately refraining from denominational labels. However, with the abolition of the ban on Christianity and the arrival of a relatively politically liberal climate, missionaries gradually reverted to their original denominational affiliations. “The concern for a united witness through cooperative mission was soon replaced by a focus on establishing Western denominational churches (Mullins 1998, p. 13)”.

Moreover, the Church Union Movement nationwide can be traced back to the Meiji period’s General Fellowship Meeting for All the Protestant Christian of Japan (zenkoku kirisutokyō shinto daishinbokukai 全国基督教信徒大親睦会). The first Meeting was held in Tokyo in 1878, at a time when Protestant churches had already been established across the country for several years, with the purpose of fostering fellowship and exchanging information. Two years later, the second Meeting took place in Osaka, followed by the third and fourth Meetings held in Tokyo and Kyoto, respectively. In this period, the pastors emphasized the “spirit of fellowship” among Christians and the foundation of a common faith. They also highlighted the importance of religious freedom and opposed interference in religious issues, with a clear atmosphere of non-denominationalism (Miyakoda 1941, pp. 6–10). In 1885, during the fourth General Fellowship Meeting in Kyoto, the assembly was reorganized into the Evangelical Alliance (fukuin dōmeikai 福音同盟会) and applied to join the Evangelical Alliance in London, an organization supporting ecumenism. However, at this stage, the idea of establishing a united church could only be found in the minds of a few Christian leaders.

Moving into the 20th century, the Church Union Movement emerged successively across various regions of Asia. In India, the South India United Church was formed in 1908 by Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Reformed Churches, which later aimed for a union with four dioceses of the Anglican Church. In 1924, the United Church of North India was formed, composed of Evangelical Reformed Churches, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, etc. In 1927, several denominations merged with the Church of Christ in China. In 1929, the United Evangelical Church of the Philippines was established. To some extent, these movements inspired pastors in Japan (UCCJ 1997, p. 5).

The influence of the Church Union Movement in Japan, at its outset, was not reflected in the organizational dimension but rather in missionary activities. In June 1910, the World Missionary Conference, regarded as the formal beginning of the modern ecumenical movement, was held in Edinburgh, UK, with three representatives from Japan: Honda Yōitsu 本多庸一, Ibuka Kajinosuke 井深梶之助, and Harada Tasuku 原田助. At this conference, chaired by John R. Mott, the emphasis was placed on the significance of cooperation, contrasted to denominational competition throughout the world. In December of the following year, 1911, the Evangelical Alliance was renamed the Japan Association of Christ Church (nihon kirisutokyōkai dōmei 日本基督教会同盟), with eight denominations engaged (Nihon 1994a, pp. 114–15).

The nationwide cooperative evangelism movement, which began in 1914, was financially supported by the Japan Association of Christ Church, while various denominations were carrying out the movement’s activities. Over the course of three years, 3336 gatherings were held across the nation, attracting approximately 650,000 attendees, with 6735 people committing to Christianity (Suzuki 2017, pp. 211–12).

As Christianity was a foreign and minority religion, more than 90% of the Japanese population had little opportunity to directly encounter missionary work or gospel sermons; therefore, during this period, the cooperative evangelism movement primarily relied on mass media, especially newspapers, and the following four methods were implemented at the time:

- Paying a substantial amount of money for publishing evangelistic passages in newspapers.

- Introducing anecdotes or facts that are favorable to evangelism and Christianity.

- Printing essays and lectures by prominent figures in the Christian community in newspapers.

- Reporting on assemblies and various other evangelistic activities (Saba 1937, pp. 727–39).

3.2. The National Christian Council of Japan

In May 1922, John R. Mott, who by then had become the chairman of the International Missionary Council, visited Japan and summoned the efforts toward reorganizing the previous assemblies of Christian organizations to establish a unified Christian alliance. As a result, in November 1923, shortly after the Great Kantō Earthquake, the National Christian Council of Japan (abbr. NCCJ, nihon kirisutokyō renmei 日本基督教聯盟) was officially formed. It was comprised of 17 denominations and religious organizations, including the Church of Christ in Japan (Presbyterian Church), the Japan Methodist Church, the Japan Congregational Church, the Anglican Church in Japan, the East and West Baptist Conventions, and other mainstream denominations. At its inception, the NCCJ was a relatively loose organization, with most denominations participating by sending representatives rather than joining as unified bodies. In its first resolution, the Council listed 19 denominations it wished to persuade to join, which notably included not only the major Protestant denominations in Japan at the time but also extended an invitation to the Orthodox Church of Japan (NCCJ 1924, p. 3). This reflects the Council’s broad ecumenical approach and efforts to unify a wide range of Christian traditions.

According to the Constitution of the Council, it was recognized as an evangelical Christian association dedicated to fostering cooperation among various Christian denominations in Japan while also promoting engagement in the global ecumenical movement. Due to its strong emphasis on ecumenism, the Council remained a key driving force in the Church Union Movement until 1941 (NCCJ 1924, p. 4). Consequently, the NCCJ soon emerged as the leading catalyst for the coordinated cooperative evangelism movement among churches.

Additionally, the Council sent representatives to participate in the International Missionary Council (abbr. IMC) and became one of its partner organizations, thereby engaging with other countries’ national Christian councils globally. Domestically, when the government implemented religious policies, representatives of various religions were often invited to participate in discussions and were expected to enforce government directives. In these instances, members of the NCCJ were selected as representatives of Protestant Christianity. Consequently, the NCCJ became recognized both domestically and internationally as the representative organization for Protestant Christianity in Japan (Dohi 2007, p. 101). Moreover, the NCCJ increasingly exhibited a submissive stance toward the government, particularly in the late 1930s, as Japan accelerated its shift toward totalitarianism. During this period, the Council demonstrated a growing willingness to align itself with imperial initiatives, including the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement.

The NCCJ maintained a consistent focus on and actively introduced information about the Church Union Movements from abroad. In 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany and initiated the process of “Gleichschaltung”, aimed at establishing state control over all public and private spheres, including Christian organizations. As part of this effort, the German Christians Movement was launched, with the objective of consolidating 28 Germany’s regional church bodies into a single, government-sponsored Church, the German Evangelical Church, also colloquially known as the Reich Church in English (Hockenos 2004, pp. 15–23). The National Christian Council Bulletin, the official newspaper of the NCCJ, published a commentary by a foreign missionary from the Deutsche Ostasienmission residing in Tokyo concerning Nazi Church Policies. The missionary criticized recent reports in Japanese newspapers regarding the alleged persecution of German Protestants, arguing that the information was incomplete and shaped by impressions formed from Anglo-American reports. He asserted that the establishment of the state church not only fulfilled the long-held aspirations of German Protestants but also represented a patriotic revolution welcomed by the people. The reorganization of the previously fragmented Protestant denominations into a united state church was, according to him, truly a revolutionary development (NCCJ 1933b, p. 2). In a later report, the NCCJ believed that “Under the Nazi regime, the German Protestant Church came under complete state control. The church was regulated through the appointment of government-approved bishops, and even previously independent denominations such as the Baptists and Methodists were brought under this control. This situation is somewhat ironic, as it was the Protestant Church’s long history of division and inability to unify on its own that ultimately led the government to impose forced consolidation (NCCJ 1933a, p. 8)”. It seemed to suggest that, in the future, Japan might also establish a united church and accomplish the goals of the Church Union Movement under the leadership of the government.

Despite the fact that the Church Union Movement had been actively promoted by the Council, the aspiration to establish a united church was difficult to achieve, as many denominations strongly resisted the Union. For instance, the Anglican Church in Japan held a relatively conservative stance on the Church Union Movement, with internal divisions regarding participation in a united church. Opponents asserted that the foundation of Anglicanism lies in apostolic succession through episcopal governance, and that a united church would undermine this episcopal structure. They contended that a truly united church should include both the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church to form a “genuinely united Imperial Christendom”, rather than merely a Protestant denomination. The high church faction, which aligns more closely with Catholicism, particularly in terms of episcopal governance and sacraments, saw the creation of a united church as a threat to the preservation of their liturgical practices (Saji 2007, pp. 243–44). Another denomination holding a negative attitude toward the Church Union Movement was the Japan Evangelical Lutheran Church (abbr. JELC), which was introduced to Japan in the 1890s by the United Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in the South. The JELC placed great importance on creeds and sacramental matters. As early as the 1931 denominational conference, it emphasized that “rather than Church Union, which is currently seen as most necessary in Japan, it is more important for each denomination to clearly assert its doctrinal stance and advance by highlighting these distinctions. A vague agreement on creeds alone is by no means a source of powerful evangelism (Tokuzen 2007, p. 398)”. The JELC highly prioritized the Augsburg Confession, particularly Article VII, which states: “There is one holy Christian church, and it is found where the gospel is preached in its truth and purity and the sacraments are administered according to the gospel”. During the preparatory meeting of the UCCJ, JELC representatives repeatedly argued that, in accordance with this Article, the unity of the church should be based on the unity of the gospel and sacraments and that this unity should be affirmed through a shared Confession of Faith. However, their opinions, being in the minority, were rejected, and JELC ultimately joined the UCCJ under duress (Tokuzen 2007, pp. 400–1).

Denominations such as the Salvation Army (abbr. TSA) also expressed resistance to the Church Union, but it was ultimately the shifts in the social-political landscape and the enactment of the Religious Organizations Law in 1939 that facilitated the establishment of the UCCJ.

4. The Religious Organizations Law and Christianity

During the course of modern Japanese state-building, Meiji oligarchs consistently strove to project a secular appearance, rejecting religion as a component of Japan’s national definition, which was ultimately enshrined in the 1889 Imperial Constitution. Both Shinto and Buddhism were deemed insufficient to serve as the center pivot for integrating the nation, as Christianity had been in the West.4 As a corollary, the constitution adopted the principle of religious freedom instead of merely toleration (Maxey 2014, pp. 1, 183). After the promulgation of the Constitution, Imperial Japan embarked on the challenging pursuit of religious legislation, culminating in the enactment of the Religious Organizations Law in 1939, which established comprehensive legal regulations concerning religions.

4.1. The Development of Religious Legislation

The Meiji Constitution affirmed the Emperor’s sovereign authority over Japanese Empire, while the Imperial Rescript on Education (kyōiku chokugo 教育勅語), issued the following year, closely intertwined filial piety (as a family virtue) and loyalty (as a national virtue). Together, they underscored the Emperor’s rule over the Japanese Empire and the subjects’ dual obligations of filial piety and loyalty as the “essence of the kokutai 国体(national polity)”, the official state ideology.5 This combination laid the foundation for a patriarchal state, with the emperor positioned as the head of the vast familial structure that was Imperial Japan (Sueki 2021, pp. 5–8).

Religion was relegated to the private sphere, with Article 28 of the Meiji Constitution stipulating that subjects were granted the right to religious freedom: “Japanese subjects shall, within limits not prejudicial to peace and order, and not antagonistic to their duties as subjects, enjoy the freedom of religious belief (Translated by Ito 2003)”. It is noteworthy that the religious freedom guaranteed by this provision was limited within the boundaries of not contravening the kokutai and neither offending nor defaming the royal household. Violations of these conditions could result in charges of lèse-majesté or disrespect toward the sovereign. The Peace Preservation Law (chian iji hō 治安維持法), enacted in 1925, provided the strongest legal protection for the Emperor system, the kokutai. In the following 1928 amendment, “attempt to alter the kokutai” could result in the death penalty. This law was introduced with the aim of enabling the Special Higher Police (tokubetsu kōtō keisatsu 特別高等警察) to more effectively suppress alleged socialists and communists. By the 1930s, Japan’s leftist movements gradually declined, and the law was increasingly used to crack down on new or perceived new religious movements; several religious groups, including Ōmoto (ōmotokyō 大本教) and Jehovah’s Witnesses, facing repression under this law.

Shortly after the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution, the Japanese bureaucracy sought to establish a law regulating religious issues. In 1899, Japan was preparing to revise its treaties with Western nations, which would allow foreigners to enter the Japanese mainland, referred to as naichi zakkyo 内地雑居, as previously, foreigners had been restricted to coastal settlements. For the first time, Japan submitted a religious law to the Diet aimed at safeguarding the freedom of religion and missionary activities for foreigners while simultaneously strengthening control over religious activities to prevent violations of “public order and peace” and “subjects’ obligations”. However, the Buddhist factions, dissatisfied with the equal treatment of Buddhism and Christianity in the proposed law and fearing that the impending naichi zakkyo would enable Christianity, backed by abundant overseas funding, to expand its missionary activities on a large scale, mounted opposition—including defamatory campaigns against Christianity—that ultimately led to a miscarriage of the bill (Ogawara 2014, pp. 18–20). In 1927, the second religious bill was submitted to the Diet, which not only targeted Sect Shinto, Buddhism, and Christianity but also addressed new religions, regarded as “cult” by the government, as it followed the suppression of the Ōmoto. The bill focused particularly on eliminating the influence of “cults” and emphasized government control over religious issues. However, it encountered widespread opposition from intellectuals and religious communities. One of the reasons for this disapproval was the state’s shift from granting land to religious organizations free of charge to requiring compensation through sales or leases, which infringed upon the property rights of these religious groups. This resistance ultimately led once again to the bill’s failure (Ogawara 2024, pp. 83–115). Just two years later, in 1929, the religious bill was resubmitted again under the new name “Religious Organizations Bill”. This version placed increased focus on utilizing the unique characteristics of religious organizations to “educate” and “guide” the subjects in moral and ideological matters. Nevertheless, due to the Hunggutun incident, which led to the dissolution of the Tanaka Giichi 田中義一 cabinet, the bill was never fully deliberated and was eventually abandoned (Ogawara 2013, pp. 153–56).

In 1934, the investigation and drafting of the religious bill were revived, initially driven by concerns over the detrimental impact of new religions, with the aim of excluding them through legislation. However, with the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the launch of the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement, the focus shifted. In 1939, Education Minister Araki Sadao 荒木貞夫 formally submitted the bill to the Diet, stating that “religions are closely tied to the stimulation and guidance of the national spirit, a fact that needs no elaboration. Especially in the current extraordinary circumstances, religions have a profound influence on people’s mindset and society, making their healthy development crucial. Therefore, this bill has been proposed to promote the growth of religious organizations and to enhance their role in moral education (Kanpō 1939, p. 38)”. The bill was ultimately passed on 7 April 1939, and came into effect on 1 April 1940, under the title of “Religious Organizations Law”. The Japanese government’s four successive legislative efforts reflected two primary attitudes toward religion. On the one hand, there was a clear intent to strengthen the supervision of religious organizations to prevent them from undermining the kokutai and disrupting social order. On the other hand, the government sought to leverage religion to guide subjects’ thoughts in alignment with state policies.

The Religious Organizations Law classified religions into two categories: “recognized religions” (kōnin syūkyō 公認宗教) and “quasi-religions” (ruiji syūkyō 類似宗教). Recognized religions include Sect Shinto, Buddhism, and Christianity, which are eligible to establish religious organizations and be granted legal entity status; however, individual sects or denominations could not directly seek acknowledgment as religious organizations; they must form some level of federation to qualify for incorporation. On the other hand, “quasi-religions”, such as new religions like Ōmoto, were considered by the government to be “cults”, although they could register as “religious associations” (syūkyō kessya 宗教結社), they were not granted corporate status and lacked privileges such as tax exemptions, while also facing stricter regulations (Gakusei 1981).

4.2. The Christian Community’s Response to the Legislation

The NCCJ responded keenly to the government’s move toward religious legislation, and in the early stage of the drafting of the Religious Organizations Law, the Council set up a Special Committee to study the draft and suggest eliminations and revisions to government authorities. The officers of the Council and this Special Committee were, therefore, prepared to become the liaison between the denominations and the government when the necessity arose for repeated negotiations regarding the implementation of the law (NCCJ 1940a, p. 6). Serving as a mediator between the Christian community and the government was a challenging endeavor, as divisions ran deep among the various denominations. Many of these denominations were opposed to the bill and sought amendments. Tomita Mitsuru, a member of the Ministry of Education’s Religious Issues Investigation Committee, believed that the Ministry aimed to protect Christianity but emphasized that the Christian community needed to present a unified stance in order to more effectively advance revisions to the bill. Nevertheless, the majority of petitions that could have been advantageous to the churches were eventually rejected (Dohi 2007, p. 116).

In the NCCJ’s propaganda, the Christian community expressed a welcoming attitude toward the enactment of the Religious Organizations Law. It was noted that, in previous religious affairs, Christianity had not been specifically mentioned but was only categorized as part of “Shinto, Buddhism, and other religions”. However, the new law, which placed Christian denominations alongside Shinto sects and Buddhist schools, signified that Christianity had officially been acknowledged as a “recognized religion” for the first time in Japanese history. For over 80 years since Protestant Christianity had been introduced into Japan, it had been associated with an unfavorable impression as kirishitan 切支丹 dating back to the Tokugawa period. Therefore, this new development was regarded as a “special privilege” for Christianity, potentially raising national awareness that Christianity, too, could contribute to Japanese culture (NCCJ 1939, p. 1). Meanwhile, they believed that the Church Union Movement would have a beneficial impact on the development of religion under the law.

“Therefore, if Christianity is to stand alongside other religions organizations, enhance its value, and play an active role in the religious sphere of our country, now is the time to cast aside the narrow sentiments of denominational division, purse unity, and demonstrate a spirit of solidarity and seriousness. Particularly in conforming to legal requirements that are nearly identical in form, the significance of maintaining separate denominations will largely diminish.”(Kirisutokyō 1940, p. 1)

The NCCJ swiftly convened representatives from various denominations to form a Church Union Preparatory Committee tasked with coordinating communication between the Ministry of Education and the denominations, as well as preparing for the establishment of a united church. On 12 June 1940, the Ministry of Education assembled church representatives to inform them that the official standard for establishing a religious organization was a minimum of 50 Churches and 5000 members. In practice, this meant that only eight big denominations would qualify to form a religious organization (Miyakoda 1941, pp. 116–17).6 The table below presents the statistical data of major denominations as of the end of 1939 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of Churches, Clergy and Believers in Major Denominations in Japan (December 1939) (Nihon 1994b, pp. 328–35).

After the Ministry of Education issued the standards for the recognition of religious organizations, a sentiment of unease spread among small- and medium-sized denominations, as they realized that in order to survive, they would need to merge with larger denominations. Nevertheless, amid the strained social atmosphere of 1940, Christianity faced multiple pressures. Unlike Buddhism, which sought to constitute several religious organizations, the Christian leadership ultimately chose to unite all denominations as much as possible under one single united church.

5. Church Union Under Social-Political Pressure

Christianity, as a foreign religion, has historically encountered a degree of hostility in Japan. As early as 1891, the Uchimura Kanzō’s 内村鑑三 Lèse-majesté Incident sparked widespread public debate over whether Christianity was in conflict with Japanese kokutai, Many Christian denominations still remained financially and organizationally dependent on their foreign parent churches. With the war intensifying Japan’s antagonism toward Western countries during the late 1930s, Christianity increasingly became a target of nationalist criticism, with suspicions that it might serve as a front for foreign espionage or a fifth column. This external social-political pressure significantly accelerated the process of unification. In this section, this paper intends to use The Salvation Army Spy Incident as a case study to examine the social-political landscape that Christians faced at the time, their coping strategies, and the impact of this context on the establishment of UCCJ.

5.1. The Salvation Army and the Spy Incident

The Salvation Army (abbr. TSA) was founded by William Booth and his wife Catherine Booth in 1865 London, in alignment with the Holiness Movement. In contrast to other Protestant denominations, TSA did not call its clergy “pastors” or “missionaries”; rather, it made use of military ranks such as General, Major, Captain, Lieutenant, Cadet, and Soldier, with the organizational structure also similarly mirroring that of the military. Additionally, compared to other denominations, TSA placed great emphasis on social welfare activities, including the abolition of prostitution, labor protection, leprosy relief, temperance, and other social relief work, as well as charitable activities (Sugiyama 1996, pp. 50–65; Kasai 2007, pp. 1205–6). These social service efforts have become one of TSA’s defining characteristics.

In May 1895, TSA’s captain Edward Wright, with a dozen soldiers, arrived in Japan and established the Japan Salvation Army’s headquarters in Kyōbashi, Tokyo. Yamamuro Gunpei 山室軍平, who enlisted in the same year, became the first Japanese commander of the Japan Headquarters in January 1927 and was promoted to Lieutenant General in June 1930. As a paramilitary organization, Salvation Army Japan was also under the leadership of a commander, with the Japan Headquarters being subordinate to the International Headquarters in London (UCCJ 1997, p. 156).

In the 1930s, as Japan’s socio-economic environment deteriorated under the impact of the Great Depression, military tension between China and Japan increased following the Mukden Incident. In response, TSA began advancing initiatives, such as employment guidance for families bereaved by war, childcare services, and troop visitation efforts. Their commitment was encapsulated in the faith of Yamamuro, who held that “a loyal Japanese Salvationist should also be the most loyal Japanese citizen”. However, there remained latent suspicion within and outside the TSA, questioning whether the Japan Salvation Army was merely an outpost of the international headquarters, given that the latter sent commanders, issued directives, provided financial support, and retained authority over personnel appointments (UCCJ 1997, p. 156). With suspicion continuing, a faction of young soldiers among TSA, driven by nationalist sentiments, demanded reforms within the organization. Their requests encompassed the dismissal of foreign commanders, the downsizing of supervisory bodies, the public disclosure of budgets, and, most importantly, a call for the Japan Salvation Army to break away from international headquarters to establish autonomy. However, these demands were rejected by the leadership of the Japan Salvation Army, eventually leading to two infightings in 1936 and 1937. Ultimately, the young soldiers broke away from the organization and founded a separate group (UCCJ 1997, p. 157).

In March 1940, during the session of the Diet, Congressman Imai Shinzō 今井新造 delivered harsh criticism of TSA and called on the authorities to dissolve it. His stance was echoed by certain nationalist groups that gave rise to a broader social movement aimed at denouncing TSA. Their denunciation was based on the following three reasons:

- They argued that the paramilitary system was bearing too much resemblance to the imperial military, which they regarded as a form of desecration.

- They claimed that the Salvation Army was at risk of becoming a tool of the British.

- They delved into the essence of its ideology and faith, pointing out that its teachings harbored underlying elements that were anti-kokutai and lèse-majesté (Naimushō 1940c, p. 66).

At that time, a widely circulated rumor alleged that the international headquarters had issued specific directives, stating that during the Mukden Incident, there had been a secret order to prevent the deployment of Japanese troops and that, under the guise of visiting families bereaved by war, there had been an attempt to gather intelligence about the nation’s situation. Nevertheless, even the Special Higher Police had doubts about these claims, yet they still stirred widespread suspicion of TSA (Naimushō 1940c, p. 66). Subsequently, Yamamuro’s book The People’s Gospel was banned from distribution.

An unexpected incident in June 1940 brought this tense atmosphere to climax. Murakami Masaaki 村上政明, a member of the Japan Salvation Army’s Sapporo branch, was conscripted into the army in 1939. However, his faith was deeply rooted in anti-war principles, which conflicted with his military duties and the education he received, and he chose to take his own life ultimately (Naimushō 1940b, p. 156).

On 31 July 1940, the Tokyo gendarmerie unexpectedly summoned four leaders of TSA: Commander Uemura Masuzō 植村益蔵, Chief Secretary Segawa Yasoo 瀬川八十雄, British financial secretary Victor Rich, and secretary Takahashi Kazutoshi 高橋一俊, additionally demanding to search the Salvation Army headquarters. The gendarmerie had no concrete evidence for their actions; they acted based on rumors that the TSA was engaged in espionage activities and spread anti-war and anti-military propaganda. Nevertheless, this measure was taken as an administrative procedure intended to prevent and suppress any future subversive activities. It also appeared to be designed to pressure the TSA to align with national policies and contribute to various “Continental Policy” through organizational reform. As a result, unless substantial criminal evidence was uncovered, the operation seemed limited to gathering information about the current situation. Those summoned were quickly allowed to return home, and after consultations with the Ministry of Education, orders were issued to reform and restructure the Japan Salvation Army (Naimushō 1940b, p. 157).

Ultimately, TSA succumbed to governmental pressure and underwent comprehensive reforms. The organization was renamed “the Salvation Group” (kyūseidan 救世団), abandoning its military structure, including changes in uniforms and titles, and prohibiting the use of any terminology associated with the Japanese military. All ties with the British headquarters were severed, and the employment of Western individuals in any position was prohibited. The leadership was restructured to be elected internally, with a term limit of five years. While the organization continued its public welfare activities, it was required to emphasize that its purpose was to serve Imperial Japan (Naimushō 1940a, pp. 170–72).

5.2. The Establishment of a United Church

In reality, it was not only TSA that faced attacks from nationalists; Christianity as a whole encountered the same situation. In terms of political pressure, Protestantism was viewed as a religion associated with Anglo-American factions, with the headquarters of various denominations in the West largely advocating pacifist, anti-war, and anti-military ideologies, the influence of which extended to Japanese churches and was regarded as an impediment to the establishment of the New Order in East Asia. On the societal front, The Salvation Army Spy Incident exacerbated nationalist sentiments, rapidly intensifying anti-Christian hostility (Naimushō 1940e, pp. 115–16).

On 21 September of the same year, nationalists convened a Christian Impeachment Conference in Tokyo, asserting that “Christianity constructs an idealistic utopia by espousing false and ostentatious rhetoric such as liberty, equality, and fraternity; however, their true aim is global domination through blind faith in Christ, which is part of a Jewish conspiracy to fundamentally undermine Japan’s kokutai. We must decisively eliminate Japanese Christianity, which serves as a puppet of Jewish ideology and is corrupting the spirit of the Japanese people (Naimushō 1940e, pp. 117–18)”. Conspiracy theories directed against Jews communities had also been frequently observed in the East. Similar anti-Christianity rallies were held by youth nationalist organizations in Fukuoka and other regions. As a result, the social atmosphere of Christianity became increasingly hostile, placing the survival of the Christian community in jeopardy.

Many Christian denominations, particularly smaller sects, faced the issue of overseas dependency, especially in terms of financial reliance on funding from Western churches.8 With the forced severance of ties with foreign counterparts, the formation of a united church to achieve financial independence became nearly their only viable option (Miyakoda 1941, pp. 12, 118). The Ministry of Education also tended to establish a single Protestant organization, which would facilitate the regulation and mobilization of their activities (UCCJ 1997, p. 278). As a highly independent denomination, TSA did not join the NCCJ but chose to join the united church after careful consideration (Naimushō 1941, pp. 42–43).

Meanwhile, the Christian leadership sought to present the image of Christians as patriots to both the government and public. They repeatedly underscored the beneficial role of evangelistic activities in supporting the construction of the New Order in East Asia, with the aim of securing greater space for survival and avoiding dissolution. As a result, they chose to announce the establishment of the UCCJ, a united church, and finalize the Church Union Movement during the grandiose patriotic commemoration of the 2600th Anniversary of the Japanese Empire.

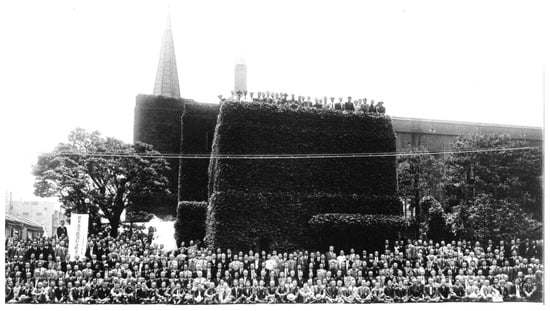

However, regarding the specific form of the united church, two differing opinions emerged: one favored grounding it on a Confession of Faith, while the other proposed postponing discussions on doctrine and creed, focusing instead on forming an organizational union, which was supported by many small-scale denominations. Due to the involvement of multiple denominations, the final decision was to focus on the organization rather than first drafting a unified Confession of Faith. The initiators merely formulated a basic “doctrinal summary” and “guidelines for living” (UCCJ 1997, pp. 279–80). Thus, the United Church of Christ in Japan, consolidating 33 denominations into 11 divisions, was officially established on 24 June 1941 (Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Denominational Affiliations within the United Church of Christ in Japan (UCCJ 1997, p. 315).

Figure 2.

Founding Commemorative General Assembly of the United Church of Christ in Japan, 1941.6.24–25. © UCCJ. 2024.

For those resistant to the Church Union, the first year of the establishment of the UCCJ saw significant autonomy and continuity for each denomination due to the creation of the division system. Each division retained considerable independence, including the composition of personnel, the setting up of offices, the publication of the respective official newspapers, and even the management of their own budgets. In essence, during this period, the UCCJ functioned more as an alliance of denominations rather than as a fully united church. However, the Ministry of Education favored the creation of a completely consolidated church and thus moved to dismantle the division system. By 1942, 97 clergies from the 6th and 9th divisions associated with Holiness denominations had been suppressed on charges of violating the Peace Preservation Law. As a result, the division system became unsustainable. In response to the Ministry of Education’s demands, the General Assembly held on 24–25 November 1942, formally abolished the division system, leading to the complete dissolution of denominational structures and the full consolidation of the UCCJ (Kainō 2015, pp. 35–37).

As previously mentioned, the Anglican Church consistently resisted joining the united church because of its adherence to episcopal governance and sacraments. Negotiations between the Church Union Preparatory Committee and the Anglican Church remained difficult. In fact, the leadership of the Anglican Kyoto Church declared: “if the authorities choose to suppress the church, they are prepared to face martyrdom (Naimushō 1940d, pp. 60–61)”. Ultimately, among Japan’s major denominations at the time, only the Anglican Church did not join the UCCJ as a whole body.

After the Anglican Church decided not to join the united church, it applied to the Ministry of Education for permission to establish an independent religious organization, but this request was denied. As a result, the Anglican Church could only exist as a religious association, causing internal division within the church: one faction supported the Church Union and joined the UCCJ, while another faction, especially the high churches, continued to resist the union. By 1943, approximately 89 churches, roughly one-third of the entire Anglican Church, had broken away and joined the UCCJ. Meanwhile, the leadership of the non-union faction faced varying degrees of government repression. Among them was Bishop Paul Sasaki Shinji パウロ佐々木鎮次, the Primate of the Anglican Church in Japan, who was detained multiple times by the gendarmerie from November 1944 on charges of secret association. Although he was ultimately not prosecuted, he suffered severe mistreatment while in custody. Postwar Sasaki tirelessly worked to rebuild the Anglican Church but passed away in December 1946 (Ōe 2015, pp. 136–43).

6. Conclusions

With the influence of ecumenism since the Meiji era, the Church Union Movement had been an undercurrent within Japanese Christianity, even leading to the formation of the NCCJ, which acted as a flagbearer for the movement. Nevertheless, various denominations brought distinct theological and ritual traditions to Japan, such as the episcopal system of the Anglican Church and Augsburg Confession of the Japan Evangelical Lutheran Church. As a result, efforts to establish a united church solely through internal Christian dynamics faced significant challenges. Additionally, it was not until fundamental changes occurred in the broader external environment that the possibility of creating a united church became more achievable.

Christianity in Imperial Japan had long been challenged by its compatibility (or lack thereof) with Japanese culture and kokutai. It has often been regarded as a foreign and “hostile” religion. This perception intensified in the late 1930s, as Japan’s diplomatic relationship with Western states, particularly Anglo-American countries, deteriorated and as the nation moved toward a wartime totalitarian regime. In this context, we can observe a pattern of interaction between the Christian community and the State: the government sought to strengthen its control over religious groups, while Christianity aimed to eliminate foreign influence by replacing foreign missionaries with Japanese clergies and severing all financial, organizational, and personnel ties with overseas churches, so as to construct a distinctly “Japanese Christianity” which could serve for the wartime regime.

The state pursued these goals through three main avenues: Firstly, following three failed attempts from the late Meiji era, the Religious Organizations Law was eventually enacted in 1939, requiring all religious groups to form religious organizations that would fall under the supervision of the government. Secondly, the administrative guidance from the Ministry of Education played a crucial role in the Church Union Movement. After the implementation of the Religious Organizations Law, the legislation lacked clear provisions regarding the specifics of personnel, institutional structures, or requirements for religious organizations. Key issues such as criteria about the number of members or churches and whether to establish a division system were left to administrative guidance, which could be viewed as both a powerful supplement to the law and a form of soft governance. Lastly, the Special Higher Police and gendarmerie supervised and prosecuted Christian groups under the Peace Preservation Law, as evidenced by incidents such as The Salvation Army Spy case, surveillance that created a real sense of threat among Christian leadership regarding the survival of Christianity, and was also a response to increasingly radical nationalists.

To some extent, the establishment of the UCCJ can be seen as both a success of the longstanding Church Union Movement within the church and a reflection of the failure and compromise of Christian leadership in yielding to external pressures. On the one hand, the Christian community reacted with enthusiasm to the Religious Organizations Law, which marked the first time Christianity’s legal status was explicitly acknowledged; meanwhile, they viewed it as a potential shield against criticism from nationalists. On the other hand, faced with intensifying constrained space for religious freedom, they sought to demonstrate patriotism and align with the government’s measures and guidance in order to preserve the survival of Christianity in Japan. Ultimately, the objective was to absorb as many denominations as possible, cut off foreign churches, and establish a united church under the surveillance of the authorities. Naturally, not every denomination or Christian succumbed to such actions; however, under a progressively harsh atmosphere of religious repression, their ability to survive encountered even greater suppression.

The Japanese narrative is not unique. In several ways, it announces and illustrates several of the issues and crises that East Asian countries have encountered in the management of the relationships between the State and Christianity. Cultural similarities and historical trajectories account for the commonalities one can observe. In this respect, the predicament of Christianity in Imperial Japan reveals trends that would later unfold throughout the region.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | There were two parallel chronological systems in the era of Japanese Empire: firstly, the regnal year chronology based on the reign of current emperor, such as Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa; secondly, the Kōki 皇紀, or imperial calendar, counting years from the legendary enthronement of Emperor Jimmu, while, Christians and Catholics tended to prefer using the Gregorian calendar, especially when it came to church-related activities. |

| 2 | The New Order in East Asia was the rudiment of the notorious pan-Asian project “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” coined in 1940, which expounded that within the realm of the sphere, all peoples and countries would co-exist, co-prosperity, and be free from the suppression of the White race under the aegis of Japan (Swan 1996, p. 139). |

| 3 | Notably, until 1939, there were still voices within the Japanese Christian community opposing the practice of kyūjō yōhai and the veneration of imperial portraits, particularly among foreign missionaries in Japan, which even caused divisions in local churches. In Gifu Prefecture’s Evangelical Church, Mino Mission, American missionary Sadie Lea Weidner, during a Bible study session in December 1938, cited Exodus 20:3–5: “You are to have no other gods but me. You are not to make an image or picture of anything in heaven or on the earth or in the waters under the earth: You may not go down on your faces before them or give them worship: for I, the Lord your God, am a God who will not give his honor to another …” She declared that kyūjō yōhai and venerating the imperial portraits were forms of idolatry. However, some Japanese missionaries within the same church believed that issues concerning the Imperial Family were extremely delicate and should be handled cautiously. One month later, they issued a statement opposing her view, arguing that these actions were not related to religion, but were expressions of respect for the emperor, which they deemed necessary and natural. As a result, six Japanese missionaries who endorsed the statement resigned from the Church (Naimushō 1939, pp. 116–17). |

| 4 | In the eyes of constitutional framers like Itō Hirobumi 伊藤博文, only the imperial household could serve as the center pivot of the Japanese state, fulling a role akin to that of Christianity in European civilization (Yamaguchi 1999, pp. 148–50). The creation of the Shrine Bureau within the Home Ministry in 1900, separating it from the Religious Bureau, along with the growing imposition of mandatory shrine worship, could be seen as the beginning of State Shinto in a narrow sense (Maxey 2014, p. 183). |

| 5 | Kokutai is commonly translated as “national polity” or “national body” more literally, and can be said to designate the national structure, which could trace back to the Edo era but gradually became a significant ideological concept during the mid-Meiji period. Kokutai was at the basis of the emperor’s sovereignty and served as the official ideology of the Japanese Empire, part of which, including the core content of emperor reverence, overlapped with some ideas of State Shinto but also incorporated some Confucianism (Wang 2023, p. 5). |

| 6 | According to other NCCJ records, it was noted that only seven denominations in the table, excluding the Kiyome Church, met the Ministry of Education’s criteria for establishing a religious organization (Miyakoda 1941, p. 117). A possible reason for this discrepancy was that the Kiyome Church and the Japan Holiness Church originally belonged to the same denomination but experienced a division in 1936, an event referred to as hōrinesu-wakyō bunri ホーリネス和協分離. |

| 7 | Below are the corresponding Japanese names of the denominations: nihon kirisuto kyōkai 日本基督教会 (The Church of Christ in Japan); nihon mesodisuto kyōkai 日本メソヂスト教会 (The Japan Methodist Church); nihon kumiai kirisuto kyōkai 日本組合基督教会 (Japan Congregational Church); nihon seikōkai 日本聖公会 (Anglican Church in Japan); nihon seikyōkai 日本聖教会 (Japan Holiness Church); kiyome kyōkai きよめ教会 (Kiyome Church); nihon fukuin rūteru kyōkai 日本福音ルーテル教会 (Japan Evangelical Lutheran Church); nihon baputesuto kyōkai 日本バプテスト教会 (Japan Baptist Church). |

| 8 | The same situation emerged in the Catholic Church. Although the Catholic Church did not face the issue of the Church Union, its dependence on foreign institutions was even more pronounced than that of Protestant churches, as the Holy See held jurisdiction over the Catholic Church in Japan. In May 1941, The Japanese Catholic Religious Body (nippon tensyu kōkyō kyōdan日本天主公教教団) was established, with the Ministry of Education requiring that all its leadership be Japanese. However, concessions were made regarding the organizational relationship with the Vatican. One significant reason for this was that the Catholic Church maintained a staunch anti-communist stance, positioning the Holy See as a potential ally to Japan in countering communism. In 1942, Japan and the Vatican established formal diplomatic relations (Miyoshi 2015, pp. 53–85). |

| 9 | The following are the Japanese names of denominations that are not included in endnote 7: seien kyōkai 聖園教会 (Church of Seien); nihon mifu kyōkai 日本美普教会 (Methodist Protestant Church); nihon kirisuto dōhō kyōkai日本基督同胞教会 (Church of the united Brethren in Christ); nihon fukuin kyoukai日本福音教会 (Evangelical Association); kirisuto yūkai基督友会 (Friends Church); kirisuto kyōkai基督教会 (Christian Church); nihon iesu・kirisuto kyōdan日本イエス・キリスト教団 (Jesus Christ Church in Japan); nihon kyōdō kirisuto kyōkai日本協同基督教会 (Japan Alliance Church); kirisuto dendō kyōkai基督伝道教会(Christ Evangelical Church); nihon dendō tai日本伝道隊 (Japan Evangelistic Band); nihon pentekosute kyōdan日本ペンテコステ教団 (Japan Pentecostal Church); nihon seiketsu kyōkai 日本聖潔教会 (Holiness Church in Japan); jiyū mesojisuto kyōkai 自由メソジスト教会 (Free Methodist Church); nihon nazaren kyōkai tōbubukai 日本ナザレン教会東部部会 [Church of Japan Nazarene (East)]; nihon nazaren kyōkai seibubukai 日本ナザレン教会西部部会 [Church of Japan Nazarene (West)]; nihon dōmei kirisuto kyōkai 日本同盟基督協会 (The Evangelical Alliance Mission); sekai senkyōdan 世界宣教団 (Missionary Band of the World); nihon jiyū kirisuto kyōkai 日本自由基督教会 (Japan Free Christian Church); nihon dokuritsu kirisuto kyōkai dōmeikai 日本独立基督教会同盟会 (Japan Federation of Independent Christian Churches); wesurean mesojisuto kyōkai ウェスレアン・メソジスト教会 (Wesleyan Methodist Church); fukyū fukuin kyōkai 普及福音教会 (Deutsche Ostasienmission); itchi kirisuto kyōdan 一致基督教団 (Japan United Church in Christ); tōkyō kirisuto kyōkai 東京基督教会 (Tokyo Christ Church); nihon seisho kyōkai 日本聖書教会 (Japan Assemblies of God); seirei kyōkai聖霊教会 (Holy Spirit Church); kyūseidan救世団 (The Salvation Group). |

References

- Dohi, Akio 土肥昭夫. 1975. Nihon Purotesutanto Kyōkai no Seiritsu to Tenkai 日本プロテスタント教会の成立と展開 [The Establishment and Development of the Japanese Protestant Church]. Tokyo: Nihon Kirisuto Kyōdan Syuppansya, p. 265. [Google Scholar]

- Dohi, Akio 土肥昭夫. 2007. Tennōsei Kyōhonki wo Ikita Kirisutokyō: Nihon Kirisutokyō Renmei wo Chūshin toshite 天皇制狂奔期を生きたキリスト教:日本基督教連盟を中心として [Christianity during the Period of the Emperor System: Focusing on the National Christian Council of Japan]. In Jūgonen Sensōki no Tennōsei to Kirisutokyō 十五年戦争期の天皇制とキリスト教 [The Emperor System and Christianity During the Fifteen-Year War]. Edited by Tomisaka Kirisutokyō Sentā 富坂キリスト教センター. Tokyo: Shinkyō Syuppansya, pp. 95–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dohi, Akio 土肥昭夫. 2012. Tennō to Kirisuto: Kingendai Tennōsei to Kirisutokyō no Kyōkaishiteki Kōsatsu 天皇とキリスト:近現代天皇制とキリスト教の教会史的考察 [The Emperor and Christ: A Church Historical Study of the Modern Emperor System and Christianity]. Tokyo: Shinkyō Syuppansya, pp. 455–58, 468–71. [Google Scholar]

- Endō, Kōichi 遠藤興一. 2007. Senjika niokeru Kirisutokyō to Tagawa Daikichirō 戦時下におけるキリスト教と田川大吉郎 [Christianity and Daikichirō Tagawa during the Wartime Period]. In Jūgonen Sensōki no Tennōsei to Kirisutokyō 十五年戦争期の天皇制とキリスト教 [The Emperor System and Christianity During the Fifteen-Year War]. Edited by Tomisaka Kirisutokyō Sentā 富坂キリスト教センター. Tokyo: Shinkyō Syuppansya, pp. 131–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gakusei, Hyakunenshi Hensyū Iinkai 学制百年史編集委員会. 1981. Syūkyō Dantaihō (Syō) (Syōwa Jyūyonnen Shigatsu Yōka Hōritsu Dai Nanajyūnanagō) 宗教団体法(抄)(昭和十四年四月八日法律第七十七号) [Religious Organizations Law (Law No. 77, April 8, 1939)]. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/hakusho/html/others/detail/1318168.htm (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Hara, Makoto 原誠. 2005. Kokka wo Koerarenakkata kyōkai: 15 Nen Sensōka no Nihon Purotesutanto Kyōkai 国家を越えられなかった教会:15年戦争下の日本プロテスタント教会 [The Church That Could Not Overcome the State: The Japanese Protestant Church During the Fifteen-Year War]. Tokyo: Nihon Kirisutokyōdan Syuppankyoku, pp. 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hockenos, Matthew D. 2004. A Church Divided: German Protestants Confront the Nazi Past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Miyoji, trans. 2003. The Constitution of the Empire of Japan. National Diet Library. Available online: https://www.ndl.go.jp/constitution/e/etc/c02.html (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Kainō, Nobuo 戒能信生. 2015. Nihon Kirisuto Kyōdan 日本基督教団 [United Church of Christ in Japan]. In Senjika no Kirisutokyō: Syūkyō Dantai Hō wo Megutte 戦時下のキリスト教:宗教団体法をめぐって [Christianity Under Wartime: Concerning the Religious Organizations Law]. Edited by Kirisutokyōshi Gakkai キリスト教史学会. Tokyo: Kyōbunkan, pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kanpō, Gōgai 官報號外. 1939. Kizokuin Giji Sokukiroku Daiyongō 貴族院議事速記録第四號 [House of Peers Proceedings, Record No. 4]. January 25. Available online: https://teikokugikai-i.ndl.go.jp/#/detailPDF?minId=007403242X00419390124&page=6&spkNum=13¤t=59 (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Kasai, Kenta 葛西賢太. 2007. Kyūseigun no Yamamuro Gunpei to Kinsyu Undō: Kindaiteki Jiritsu no Rinen to Jissen 救世軍の山室軍平と禁酒運動:近代的自律の理念と実践 [Gunpei Yamamuro of the Salvation Army and the Temperance Movement: The Concept and Practice of Modern Autonomy]. Syūkyō Kenkyū 宗教研究 [Journal of Religious Studies] 81: 1205–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kirisutokyō, Sekai Sya 基督教世界社. 1940. Syūdanhō no Jisshi wo Keiki toshite 宗団法の実施を契機として [On the Occasion of Implementing the Religious Organizations Law]. Kirisutokyō Sekai 基督教世界 [Christian World], April 4, No. 2922. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kirisutokyōhōsya 基督教報社. 1938. Hōkoku Dendō: Shinken naru Kentō wo Kibōsu 報国伝道:真剣なる検討を希望す [Patriotic Evangelism: A Call for Serious Examination]. Kirisutokyōhō 基督教報 [Christian News], June 17, No. 1124. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Konoe, Fumimaro 近衛文麿. 1938. Statement of the Japanese Government 3 November 1938. From 3 November 1938 to 10 June 1939 Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) Ref. B02030528700. Available online: https://www.jacar.archives.go.jp/das/image/B02030528700 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Maxey, Trent E. 2014. The “Greatest Problem”: Religion and State Formation in Meiji Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 1, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Miyakoda, Tsunetarō 都田恒太郎. 1941. Kōki Nisenroppyakune to Kyōkai gōdō 皇紀二千六百年と教会合同 [The 2600th Year of Imperial Calendar and Church Union]. Tokyo: Kirisutokyō Syuppansya, pp. 6–10, 12, 29, 43–44, 49–50, 65, 116–18. [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi, Chiharu 三好千春. 2015. Katorikku Kyōkai (Nippon Tensyu Kōkyō Kyōdan) カトリック教会(日本天主公教教団) [Catholic Church (The Japanese Catholic Religious Body)]. In Senjika no Kirisutokyō: Syūkyō Dantai Hō wo Megutte 戦時下のキリスト教:宗教団体法をめぐって [Christianity Under Wartime: Concerning the Religious Organizations Law]. Edited by Kirisutokyōshi Gakkai キリスト教史学会. Tokyo: Kyōbunkan, pp. 53–85. [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, kō 森下耕. 2018. 2・11 Messēji 2・11メッセージ. Kyōdan Shinpō 教団新報4876号 [The Kyodan Times No. 4876]. Available online: https://uccj.org/newaccount/28419.html (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Mullins, Mark R. 1998. Christianity Made in Japan: A Study of Indigenous Movements. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Naimushō, Keihokyoku 内務省警保局. 1939. Tokkō Geppō 特高月報 [Special Higher Police Monthly Report], January. 116–17.

- Naimushō, Keihokyoku 内務省警保局. 1940a. Tokkō Geppō 特高月報 [Special Higher Police Monthly Report], August. 170–72.

- Naimushō, Keihokyoku 内務省警保局. 1940b. Tokkō Geppō 特高月報 [Special Higher Police Monthly Report], July. 156–57.

- Naimushō, Keihokyoku 内務省警保局. 1940c. Tokkō Geppō 特高月報 [Special Higher Police Monthly Report], March. 66.

- Naimushō, Keihokyoku 内務省警保局. 1940d. Tokkō Geppō 特高月報 [Special Higher Police Monthly Report], October. 60–61.

- Naimushō, Keihokyoku 内務省警保局. 1940e. Tokkō Geppō 特高月報 [Special Higher Police Monthly Report], September. 115–18.

- Naimushō, Keihokyoku 内務省警保局. 1941. Tokkō Geppō 特高月報 [Special Higher Police Monthly Report], May. 42–43.

- Nihon, Kirisuto Kyōkai Dōmei Nenkaniin 日本基督教会同盟年鑑委員. 1994a. Kirisutokyō Nenkan Dai1kan (Taishō5nen ban) 基督教年鑑 第1巻(大正5年版) [Christian Yearbook, Volume 1 (1916 Edition)]. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, pp. 114–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nihon, Kirisuto Kyōkai Renmei 日本基督教会聯盟. 1994b. Kirisutokyō Nenkan Dai24kan (Shōwa16nen ban) 基督教年鑑第24巻(昭和16年版) [Christian Yearbook, Volume 24 (1941 Edition)]. Tokyo: Nihon Tosho Center, pp. 328–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nihon, Kirisutokyōdan (abbr. UCCJ) 日本基督教団. 1994. The Constitution. Available online: https://uccj.org/constitution (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Nihon, Kirisutokyōdan Senkyō Kenkyūsho Kyōdan Shiryō Hensan Shitsū (abbr. UCCJ) 日本基督教団宣教研究所教団資料編纂室. 1997. Nihon Kirisutokyōdanshi Shiryōsyū Dai 1 Kan: Nihon Kirisutokyōdan no Seiritsu Katei (1930–1941 Nen) 日本基督教団史資料集第1巻:日本基督教団の成立過程 (1930–1941年) [Historical Documents of the United Church of Christ in Japan, Volume 1: The Formation Process of the United Church of Christ in Japan (1930–1941)]. Tokyo: Nihon Kirisutokyōdan Syuppankyoku, pp. 5, 156, 278–80, 315. [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai, Kenji 落合健仁. 2013. Why the National Christian Council of Japan is to be a Carrier of Church Union Movement? Focusing on the Theory of Akira Ebisawa. Kinjō Gakuin Daigaku Ronsyū. Jinbun Kagaku Hen 金城学院大学論集. 人文科学編 [Treatises and Studies by the Faculty of Kinjō Gakuin University: Studies in Humanities] 10: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai, Kenji 落合健仁. 2017. Nihon Purotesutanto Kyōkaishi no Ichidanmen 日本プロテスタント教会史の一断面 [An Aspect of the History of the Japanese Protestant Church]. Tokyo: Nihon Kirisuto Kyōdan Syuppankyoku. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawara, Masamichi 小川原正道. 2013. “Seiji” niyoru “Syūkyō” Riyō・Haijo: Kindai Nihon niokeru Syūkyō Dantai no Hōjinka wo Megutte 「政治」による「宗教」利用・排除:近代日本における宗教団体の法人化をめぐって [Use and Exclusion of Religion by Government: Especially Focusing on the Process of Offering Corporate Body for Religious Groups by Legislation in Modern Japan]. Nenpō Seijigaku 年報政治学 [The annuals of Japanese Political Science Association] 64: 153–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawara, Masamichi 小川原正道. 2014. Nihon no Sensō to Syūkyō 1899–1945 日本の戦争と宗教 1899–1945 [War and Religion in Japan, 1899–1945]. Tokyo: Kodansha, pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawara, Masamichi 小川原正道. 2024. “Shinkyō no Jiyū” no Shisōshi: Meiji Ishin kara Kyū Tōitu Kyōkai Mondai Made 「信教の自由」の思想史:明治維新から旧統一教会問題まで [A History of the Concept of “Freedom of Religion”: From the Meiji Restoration to the Unification Church Issue]. Tokyo: Chikumashobo, pp. 83–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ōe, Mitsuru 大江満. 2015. Seikōkai 聖公会 [Anglican Church]. In Senjika no Kirisutokyō: Syūkyō Dantai Hō wo Megutte 戦時下のキリスト教:宗教団体法をめぐって [Christianity Under Wartime: Concerning the Religious Organizations Law]. Edited by Kirisutokyōshi Gakkai キリスト教史学会. Tokyo: Kyōbunkan, pp. 136–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ruoff, Kenneth James. 2010. Imperial Japan at Its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2600th Anniversary. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, p. 1. [Google Scholar]