1. Introduction

In 1654, Yinyuan Longqi 隱元隆琦 (Jp. Ingen Ryūki, 1592–1673), the revered Chinese Chan master, embarked on a journey to Japan at the age of sixty-two, leaving behind Manchu-occupied China for an unfamiliar world. Unbeknownst to him, this journey would lead to the establishment of Ōbaku Zen in Tokugawa Japan (1603–1867), the last of the three major Chan (Jp. Zen) lineages transmitted from China to Japan, following the earlier introductions of the Rinzai and Sōtō schools during the medieval period. Accompanying Yinyuan to the east were several prominent painters, including Yang Daozhen 楊道真 (active ca. 1656–1657 and ca. 1663), who brought with them Chinese Ming dynasty painting techniques and a vast collection of Chan portraits and other artworks. These contributions laid the groundwork for the flourishing of Ōbaku art in Japan, which, from its inception, was deeply intertwined with the religious context that nurtured it. During the formation and development of Ōbaku Zen, Ōbaku portraiture played a significant role and became essential embodiments and representations of Ōbaku Zen. Yinyuan’s monastic community was markedly different from Japan’s contemporary Rinzai lineages due to its pronounced “Chineseness”, which is “perhaps best preserved in the numerous portraits of Ōbaku abbots made in the first fifty years of the community in Japan” (

Sharf 2004, p. 290).

Among the more than 250 surviving portraits from the mid-seventeenth to early eighteenth century, the majority “feature prominent Ōbaku abbots and their spiritual predecessors”, and these Ming-style paintings significantly influenced later Japanese painters who depicted Buddhist subjects (

Sharf 2004, p. 292). Despite the inseparable religious imprint of these works, current scholarship on Ōbaku portraiture, as Elizabeth Horton Sharf highlights, often emphasizes technical and stylistic aspects, such as the incorporation of European painting techniques, while neglecting the religious context—doctrinal dimensions, institutional practices, and ritual uses—that is essential to fully appreciate “the internal stylistic evolution of Ōbaku portraiture” (ibid., p. 328). Focusing solely on artistic aspects risks reducing these works to aesthetic objects, leading to ahistorical and decontextualized interpretations.

Sharf seeks to bridge art historical and religious studies approaches by calling for more attention to the “meaning and function” of these portraits beyond their aesthetic and technical qualities (ibid., p. 295). She situates Ōbaku portraiture within the long-standing Chinese tradition of “ancestral portraiture” and the context of Chan/Zen monasticism, emphasizing their primary function “as proxy in the abbot’s own funeral and death anniversary rites” (ibid., p. 327). Scholars have shown that Chan portraiture from the medieval period was seen as a representation of “living Buddhas” and had various ritual and ceremonial functions (

Foulk and Sharf 1993, pp. 191–95). In this light, Sharf aligns Ōbaku portraiture with the Chan portraiture tradition, noting its stylistic and iconographic continuity (

Sharf 2004, p. 327).

While Sharf’s focus is on the functional aspect of Ōbaku portraiture, it is also important to further explore its meaning. Though the ritual function of Ōbaku portraits may not differ much from their Chan/Zen predecessors, their meaning must be interpreted within a different temporal and cultural context, highlighting the uniqueness of Ōbaku portraiture. This paper aims to historicize the meaning of Ōbaku portraiture by examining its connection to Ōbaku doctrine. Specifically, through the analysis of the painting Triptych of Three Zen Masters: Linji, Bodhidharma, and Deshan, this study contends that Ōbaku portraiture, as exemplified by this work, serves as a visual medium for articulating Ōbaku doctrine, marked by a distinct Ming Chan style adapted to Tokugawa Japan, as well as the religious aspirations of the Chinese founders of Ōbaku Zen.

Given the absence of specific studies focused on this triptych, this paper takes the initiative to explore it, contributing to our understanding of similar works within the Ōbaku portraiture tradition. Additionally, the study introduces a crucial interpretative approach that integrates images, inscriptions, and seals. To fully grasp the meaning of Ōbaku portraiture, it is crucial to view the image, inscription, and seal as an inseparable pictorial trinity. Art historians often focus primarily on the image while treating the inscription and seals as supplementary elements. However, in the Chan/Zen tradition of portraiture, the three elements—poetry, painting, and calligraphy—are inseparably intertwined, forming a unified literary genre known as

zan 讚 (eulogy). During the Song period, the

zan genre was included as a distinct category within the defining Chan literary form, Chan

yulu 語錄 (recorded sayings). The

zan genre refers to concise verse commentaries composed by Buddhist clerics for accompanying images, often inscribed directly onto the portraits in the handwriting of esteemed clerics. In

yulu texts, portrait eulogies are referred to as

zhenzan 真贊 or

xiangzan像/相贊 (

Zhang 2024, p. 244). Therefore, the inscribed eulogy is not merely decorative but associated directly with those senior monks’ thoughts and teachings, serving as a vital textual element for understanding the underlying meaning of the portrait. Moreover, the seal on a painting warrants careful consideration, as it is an integral element of Chinese painting and calligraphy, used since the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) for various purposes. Beyond indicating authorship or ownership and enhancing aesthetic appeal, seals convey meanings that reflect the artist’s personality, emotions, thoughts, and political or religious views. Thus, examining the seal provides an additional avenue for understanding an artwork’s significance.

2. Image, Eulogy, and Seal

The subject of my paper is the

Triptych of Three Zen Masters: Linji, Bodhidharma, and Deshan, a set of three hanging scrolls preserved in the University of Michigan Museum of Art (

Figure 1). The triptych was composed by Yiran Xingrong 逸然性融 (Jp. Itsunen Shōyū, 1601–1668), a disciple of Yinyuan and a pioneering figure of the Ōbaku art. Yiran depicted three revered Chan patriarchs, Linji Yixuan 臨濟義玄 (?–867), Bodhidharma, and Deshan Xuanjian 德山宣鑒 (782–865). Bodhidharma, recorded as the first patriarch of Chinese Chan Buddhism who introduced Indian

dhyāna to China in the fifth century, holds the central position in the triptych. He appears calm and lighthearted, facing the viewers straightly in a meditative pose. Linji and Deshan are seated to his left and right, with their bodies slightly tilted toward Bodhidharma in the center. Deshan is holding a stick, which epitomizes his Chan style, beating disciples with the stick to break their obsession with words, thoughts, and all external constraints. In Chan literature, as well-known as Deshan’s stick is Linji’s shout, another protagonist in this triptych. Since Linji’s shout is challenging to visualize through images, the portrait depicts his fierceness and sharpness with tightly furrowed eyebrows and a protruding skull.

Notably, the triptych of these three figures is an unprecedented and unconventional composition in the medieval Chan/Zen portraiture. However, this trio became a common subject in Ōbaku portraiture. In 1661, Yiran composed another triptych featuring the exact figures, now housed at Zuiryuji in Osaka. It can be assumed that this combination was so prominent in Ōbaku art that it also influenced Japanese painters of the time. For instance, the renowned Edo-period painter Kanō Tan’yū 狩野探幽 (1602–1674) created a similar triptych of the three masters, with an inscription in Yinyuan’s own handwriting, now preserved at Manpuku-ji in Kyoto. Thus, this grouping was not a random or accidental arrangement by the painter but rather a deliberate choice reflecting the unique teachings of Ōbaku Zen, which will be further explored in the next section.

At the top of the images are three eulogies dedicated to the three masters, handwritten in 1658 by Mu’an Xingtao 木菴性瑫 (Jp. Mokuan Shōtō, 1611–1684), one of Yinyuan’s two most illustrious disciples, the second patriarch and co-founder of the Ōbaku sect. The three eulogies are translated as follows:

- For Bodhidharma

- This foreign monk with piercing green eyes has much to say,

- His teeth glisten in the wind, and his pride is boundless.

- He agitated the Liang Emperor while his own heart remained empty,

- Undisturbed, he sits in the cool, beneath twin trees by the river.

- For Deshan

- A single hair in the infinite emptiness, a little drop of water in an unfathomable gully,

- He burned up the scriptures upon enlightenment’s arrival.

- With his stick, he guides both wise and simple,

- In the realm of karma, he is the genuine Buddha.

- For Linji

- With a voice like thunder, his shout awakened,

- The inner spirits of his fellow monks.

- A thousand years of wisdom yet never dull,

- He taught the three mysteries, uninterested in Buddha’s pull.

Mu’an’s eulogies are imbued with profound meaning, as each relates to the most enduring and emblematic episodes of the three masters in Chan literature. In the eulogy for Bodhidharma, Mu’an referred to the famous meeting between Bodhidharma and Emperor Wu of Liang梁武帝 (464–549). During the meeting, Bodhidharma realized that the emperor was not his dharma vessel, meaning he was not suitable to spread Bodhidharma’s new practice. As a result, Bodhidharma crossed the Yangzi River on a reed and settled in a cavern on Mt. Song 嵩山, where he practiced sitting meditation for nine years. The eulogy for Deshan also highlights his stick and alludes to his most repeated legend, as depicted in his hagiography. After experiencing mysterious enlightenment, Deshan piled his commentaries on the

Diamond Sutra before the dharma hall. Holding a torch, he declared, “Exhausting all profound debates is like placing a single hair in the infinite void. Unraveling all the world’s mysteries is like dropping a single drop into an unfathomable gulf”. He then set them on fire.

1 Regarding Linji, Mu’an dedicated his eulogy to the efficacy of Linji’s shouting and representative teaching, the “three mysteries and three essentials”. Mu’an’s description of Linji’s attitude toward Buddha’s words is highly compatible with Linji’s persona in Chan literature, who claimed that “when you encounter a Buddha, kill the Buddha; when you encounter a patriarch, kill the patriarch”. With encapsulated descriptions and flowing powerful calligraphy, Mu’an captured the essence of the most memorialized words and deeds of these three masters as recorded in Chan literature, which allowed their images to be better understood, adding to the overall significance of the triptych.

Another significant aspect of Ōbaku portraiture is the seal. One notable seal appears on the images of both Linji and Deshan, featuring the four Chinese characters “

hufa dongchuan 護法東傳” (Protecting the dharma and transmitting it eastward). This seal designates Linji and Deshan as protectors of the dharma, aiding in the transmission of the profound teaching of the Buddha, which Bodhidharma inherited and subsequently spread from India to China. Furthermore, the seal signifies that the Zen teaching represented and safeguarded by Linji and Deshan aligns with the authentic teaching of Bodhidharma, which Yinyuan and other immigrant monks continued to transmit eastward to Japan. This seal bears similar significance to another seal, “

Linji zhengzong 臨濟正宗” (Authentic heirs of the Linji lineage), which is prominently featured in Ōbaku portraiture and art, as exemplified in one of Mu’an’s calligraphies depicting Bodhidharma, to be explored later. Both seals connote a self-designation of authenticity, and the latter is a controversial designation that unavoidably aroused the discontent of the Japanese Rinzai sect. It is noteworthy that the seal of

Linji zhengzong originated in a Chinese context, with no intention of challenging the authenticity and authority of Rinzai. However, the fact that the Chinese immigrant monks used this designation after arriving in Japan, knowing that the Rinzai sect also claimed to be the orthodox Linji lineage, is intriguing and indicative. Moreover, Ōbaku monks have utilized this label in consecutive generations, which is still used to identify Ōbaku today (

Baroni 2000, p. 23).

The integration of images, eulogies, and seals serves as a key to contextualizing the triptych within its Chinese origins and later reception during the Tokugawa period in Japan. By examining these elements in tandem, we can better understand the symbolic and doctrinal messages conveyed through the artwork, shedding light on its role within the religious and cultural landscapes of both China and Japan.

3. Linji, Deshan, and Authentic Heirs of the Linji Lineage

It should be noted that the number of eulogies dedicated to Linji and Deshan in the yulu texts of the Song-Yuan period is rather small, suggesting that their images were not frequently featured or held a prominent place in Chan portraiture during that era. Moreover, based on the extant Chan portraiture from the Song-Yuan period, there are no depictions in which the images of these two figures appear together as a pair. This raises significant questions about the intentionality behind the Ōbaku monks’ decision to feature these figures in their portraiture. While it is essential to connect Ōbaku portraiture to the earlier medieval Chan portraiture tradition, the deliberate selection of Linji and Deshan’s images demands further scrutiny. These choices are far from incidental; rather, they signal an effort to establish new iconographic and doctrinal representations that align with the evolving identity of Chan Buddhism in Ming China. By foregrounding Linji and Deshan, these Chinese immigrant monks asserted a specific lineage and style that not only connected to earlier Chan traditions but also more directly embodied the Ming-era Chan practices shaped by the Chinese socioreligious and intellectual currents of the time.

Before arriving in Japan, Yinyuan was already a highly esteemed and accomplished monk in China, recognized for his leadership and deep spiritual practice. He served as the abbot of Wanfu monastery 萬福寺 in Fujian 福建 for nearly two decades, a position that affirmed his authority and status within the Chinese monastic community. Yinyuan’s spiritual formation was profoundly shaped by two eminent masters of the Linji school: his grandmaster, Miyun Yuanwu 密雲圓悟 (1566–1642), and his master, Feiyin Tongrong 費隱通容 (1593–1661). Jiang Wu convincingly illustrates Miyun’s pivotal role in the Ming-era revival of Chan Buddhism, crediting him with reintroducing ancient teachings and practices into actual monastic life. Miyun’s use of beating and shouting as training methods has been well documented. One account describes a visit by a patron while Miyun was staying at the private retreat of his acquaintance, the renowned literatus Tao Wangling 陶望齡 (1562–1609). During the visit, Miyun was reading the

Analects and

Mencius. The patron asked, “What are you reading?” In response, Miyun raised the texts. The patron then remarked, “This isn’t your daily fare”. Without hesitation, Miyun slapped him. The patron became furious, but at that moment, Tao Wangling arrived and explained, “The master is engaging you through the Dharma—why respond with anger?” Humbled, the patron apologized and left.

2 Another account of Miyun’s encounter with Feiyin reveals a similarly violent exchange. When Feiyin first met Miyun, he immediately asked, “How do you present face to face?” Miyun responded by striking him. Feiyin said, “Wrong”. Miyun struck him again. Feiyin gave a powerful shout, but Miyun kept hitting him. Feiyin continued shouting, and after the seventh blow, his head nearly split. At that moment, all his skills and understanding dissolved completely. He said to Miyun, “I recognize you as a true descendant of Linji. Please sit”. Miyun sat down, and Feiyin, in turn, flipped over and struck Miyun three times with his staff, saying, “So this is what your Buddha dharma is all about!” Then, holding his staff, he started to walk away. Miyun called out, “Come back, come back!” but Feiyin did not look back. Miyun followed and snatched the staff, hitting him once. Feiyin said, “I’ve seen through it now”. He then returned to his quarters that night.

3 Through the reinvention of these ancient practices, previously preserved only in antique Chan literature, by seventeenth-century Linji masters”, beating and shouting—violent expressions of enlightenment—were performed live in front of the assembly” (

Wu 2008, p. 12) and “were widely accepted as the hallmark of Chan practice” (Ibid., p. 109).

It was this Ming-style Chan, reinvented and transmitted through Yinyuan’s lineage, that shaped his practice, and later, he introduced it to Tokugawa Japan, ultimately forming the doctrinal foundation of Ōbaku Zen. Consequently, it is not surprising that the images of Deshan, the originator of beating, and Linji, the innovator of shouting, are included in the pair in Ōbaku portraiture. Positioned on either side of Bodhidharma, they are depicted as protectors of the dharma lineage that traces back to Bodhidharma and as representatives of orthodox Chan Buddhism in seventeenth-century China. The monk painter Yiran, who created this triptych, skillfully visualized the teachings and practices of Ming-style Chan. Through these images, Yiran not only honors the lineage but also reinforces the essential principles of Chan that Yinyuan brought to Japan, thereby solidifying the connection between the two traditions and highlighting the enduring influence of the Ming-era Linji Chan in shaping Ōbaku Zen.

Yinyuan’s recorded sayings corroborate the prominence of Linji and Deshan. Yinyuan alone dedicated nine and five portrait eulogies, respectively, to the portraits of Linji and Deshan, emphasizing their antinomian beating and shouting: “Through the door a cudgel greets, a boorish act indeed! Yet it roars and thunders with unyielding force, a might that cannot be denied” (

Akira 1979, p. 2473). “At the threshold, a fierce shout, sharp as a sword! Cutting straight to the point, without fanfare or affectation” (ibid., p. 2471). Despite receiving only a few portrait eulogies from the eleventh- and twelfth-century Chan masters, Linji and Deshan were prominently featured in the texts of seventeenth-century Linji masters. This was not due to Yinyuan’s preference but rather a result of the doctrine and practice he propagated in China and introduced to Japan. As such, the significance of the images of Linji and Deshan in this triptych associated closely with the Ōbaku teaching cannot be overlooked.

In addition to the images, the seal,

Authentic Heirs of the Linji Lineage, the most striking seal in Ōbaku artworks, also stemmed from the Chinese context, and this phrase can be traced back to the twelfth-century Linji school (

Wu 2008, p. 356). The Ming Linji monks reinvented this phrase as a solid assertion to reestablish the connection with the lost Chan traditions of ancient times and emphasize the legitimacy of dharma transmission “in its strictest sense” (ibid., p. 12). This focus on authenticity and the authoritative transmission of teachings became another defining characteristic of seventeenth-century Chan Buddhism, and in this period, “the authenticity of dharma transmission had to be verified through examining the evidence of transmission” (ibid., p. 10). In this light, both the seals “

Protecting the Dharma and Transmitting It Eastward” and “

Authentic Heirs of the Linji Lineage” could be seen as symbolic evidence of transmission, and the continuous use of the seals by Chinese founders of Ōbaku Zen represented their insistence on the Ming legacy of pursuing the authenticity and authority of their lineage. Furthermore, examining the metaphor of the “mind seal” within the Chan context reveals more profound implications. As Copp aptly argues, as an integral part of “mind-to-mind transmission,” it embodies the concepts of “filiation, kinship, and affinity” within that transmission, “effected and marked by the seal, in which one takes a position within an imagined spiritual bloodline anchored in ‘ancestors’” (

Copp 2018, p. 22). In this way, the seal signifies legitimacy and continuity and connects the practitioners to a rich historical and spiritual heritage.

On the other hand, the self-designation of the Chinese monks as “authentic heirs of the Linji lineage” in their artworks after arriving in Japan was not only a continuation of the Chinese Linji doctrine regarding dharma transmission but also a response to their new Japanese audience. The triptych dates back to 1658, before the Chinese monks had established themselves in Japan. The use of seals, which highlight connotations of orthodoxy, could be seen as a pictorial declaration of the newcomers’ legitimacy in a new environment, where the priority for the Chinese immigrant monks was to find patronage to survive. As Nam-lin Hur demonstrates, the Tokugawa Buddhist world was prosperous yet highly competitive. Temples survived and thrived due to the

danka system contrived by the

bakufu, which required all Japanese families to register at a Buddhist temple and for everyone to be given a Buddhist funeral after their demise. Thus, the Buddhist temples in the Tokugawa period were sustained by “the economy of death” (

Hur 2007, pp. 12–13). Inevitably, the newly arrived Chinese monks were disadvantaged in this economic model as they were invited by the Chinese merchant community, particularly of Fujian origin in Nagasaki. Thus, their source of patronage was quite limited. Moreover, Yinyuan’s monastic community was not immediately accepted in Japan. Arriving during a time when both Rinzai and Sōtō monks were already supported by Japan’s elite, the Chinese monks, though linked to the mainland Linji lineage, had no close ties to either the Rinzai or Sōtō lines in Japan and were not entirely welcomed by the Japanese clergy (

Sharf 2004, p. 292). Thus, it behooved the Chinese immigrant monks to connect with higher circles to secure powerful, dependable, and long-term patronage from the shōgun, leading members of the

bakufu, the imperial family, and Japanese intellectuals.

At that time, the Tokugawa

bakufu had an anti-Christian policy that banned trading with all countries except a few, including Ming China and the Dutch. Thus, the sea trade route became a cultural channel exclusively open to China. Moreover, after nearly four hundred years of isolation from the continent, the powerful and elite in Japan were eager to import the latest Chinese production and find someone representing China’s authentic and latest religious and cultural model. Therefore, authenticity became a crucial asset for the Chinese immigrant monks, and their continuous use of the seals was an unambiguous assertion of authenticity. Yinyuan spoke for the authentic Linji Chan certified through legitimate dharma transmission, and his mastery of Chinese poetry and calligraphy, admired by Japanese intellectual circles, represented the ideal Ming Chinese literati culture (

Wu 2015, p. 176).

Furthermore, the emphasis on authenticity among Chinese immigrant monks can be understood within the broader historical context of the Ming-Qing transition and a pan-Asian “authenticity crisis” (ibid., p. 243). Jiang Wu’s research on Yinyuan effectively highlights the complexities of this pivotal period, providing crucial context for understanding the significance of these monks’ artistic and literary compositions. With the Ming dynasty overthrown by the Manchu and replaced by the “barbarian” Qing, East Asia faced what Wu terms an “authenticity crisis,” raising doubts about where the true center of “civilization” lay. In this newly fragmented world, Japan began to imagine alternative world orders where they assumed the central role. It was during this period of shifting identities and quests for legitimacy that Yinyuan’s authenticity became particularly appealing to the Tokugawa bakufu. The Ming–Qing transition, therefore, positioned Yinyuan as a symbol of comprehensive authenticity—religious, cultural, and political—that aligned with the Tokugawa bakufu’s aspirations (ibid., p. 7). Thus, the immigrant monks’ emphasis on authenticity was not merely a continuation of Ming-style Chan but a response to the unique circumstances of Tokugawa Japan.

On the other hand, the seal used by the Chinese monks after their arrival in Japan can be understood in relation to their rivals, the Rinzai lineage, which was the Japanese equivalent of the Chinese Linji school and one of the two long-standing and influential Zen traditions in Japan. It is likely that the claim of being the “authentic heirs of the Linji lineage” would have offended and provoked the Japanese Rinzai monks. Nevertheless, the Chinese immigrant monks did not intend to avoid the possible conflicts that this phrase might cause, and they continued to use the seal and the term. Their persistent emphasis on authenticity and orthodoxy can also be interpreted as a response to the reformist desires of the Tokugawa Buddhist world, particularly those of the Rinzai lineage. As Baroni points out, many monks from the Rinzai and Sōtō Zen sects of the Tokugawa period demanded reform within their respective monasteries and religious orders. As they had traditionally done in history, Japanese monks sought renewal for Buddhist teaching and practice from China. At Myōshin-ji 妙心寺, which was one of the most prominent Rinzai monasteries of the day where a reform movement was underway, some monks, such as Ryōkei Shosen 龍渓性潜 (1602–1670) and Jikuin Somon 竺印祖門 (1611–1677), saw Yinyuan as a potential asset to revitalize Rinzai Zen at Myōshin-ji (

Baroni 2000, pp. 42–44). Ryōkei, the former abbot of the Myoshin-ji, who later became the most steadfast Japanese follower of Yinyuan, firmly believed that Yinyuan embodied the authentic teachings of Zen and that his arrival would bring about a significant change in Japanese Buddhism (

Wu 2015, p. 176). In this light, the Chinese immigrant monks’ continued use of the seal might be seen as a reaffirmation of authenticity, speaking to the reformist monks within the Tokugawa Buddhist community.

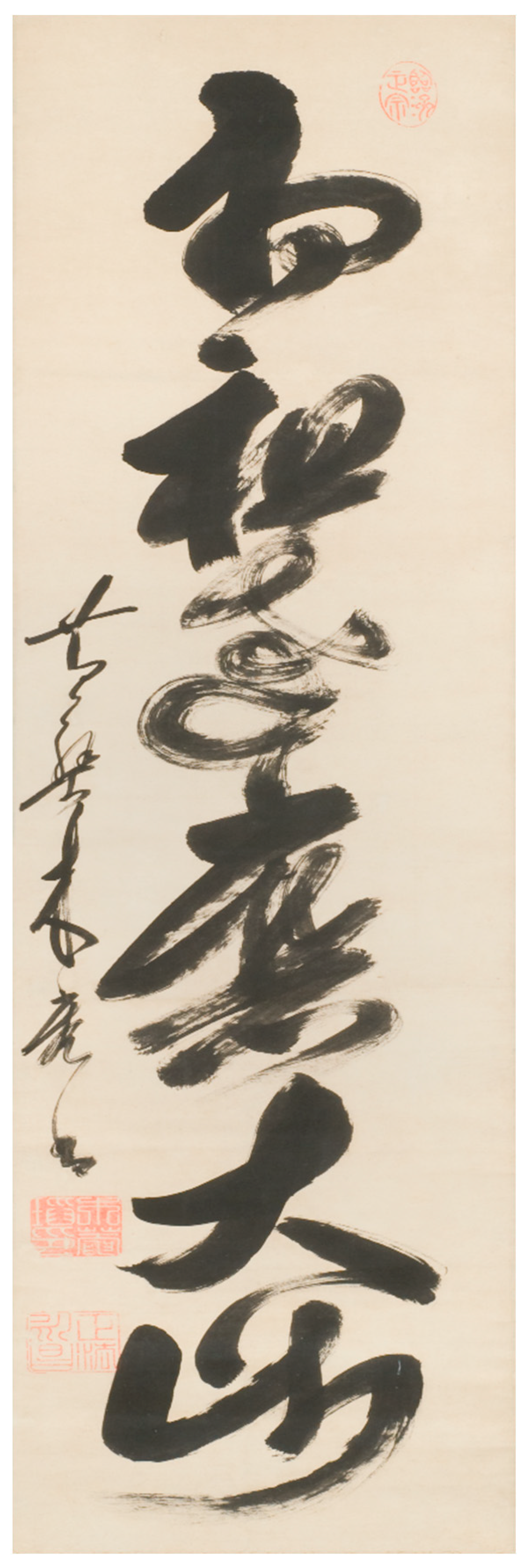

4. Centrality of Bodhidharma

The triptych is notable not only for the portrayal of Linji, Deshan, and the seals but also for the prominent position given to Bodhidharma, a recurring theme in Ōbaku art. The depiction of Bodhidharma in a central position in Ōbaku portraits is a departure from the earlier Chan portraiture tradition, where he was not accorded such a significant role. The Chinese founders of Ōbaku Zen created calligraphic works in honor of Bodhidharma upon their arrival in Japan. Yinyuan, in particular, composed as many as twenty portrait eulogies for Bodhidharma, which was rare in the Chan portrait tradition. Mu’an’s calligraphy for Bodhidharma, which reads, “First patriarch, Great Master Bodhidharma 初祖達磨大師,” is also significant as it was an appellation invented by the Chinese founders of Ōbaku Zen, not previously seen in earlier Chan literature (

Figure 2). Additionally, the seal of

Linji zhengzong appears in this artwork, affirming that Ōbaku Zen teachings align with those of the First Patriarch, thus underscoring their authenticity. The poetry of the Chinese immigrant monks further emphasizes the importance of Bodhidharma in Ōbaku Zen, with imagery such as “crossing the river on a reed,” “coming from the west,” and “meeting with the Liang emperor” repeatedly borrowed and presented. From a religiopolitical perspective, the centrality of Bodhidharma in the triptych and Ōbaku art indicates the religious aspirations of these Chinese immigrant monks in Tokugawa, Japan.

Firstly, the creation of the appellation “First patriarch, Great Master Bodhidharma,” the repeated use of the term

kaishan 開山 (to establish a mountain, or to found a sect), and the consistent borrowing of imagery depicting “the patriarch coming from the west,” all suggest that the Chinese immigrant monks were comparing themselves to Bodhidharma and aspired to follow his example in spreading the dharma and expanding the territory of their sect. One of Yinyuan’s portrait eulogies for Bodhidharma serves as an eloquent testimony to this sentiment and aspiration, which I describe as a “Bodhidharma complex”:

- A Portrait Eulogy for Bodhidharma

- From the West, you come, and to the East, I depart,

- We reveal directly, offering no two roads to start.

- You never blind others, and I shall not disappoint you,

- All day, we meet, yet we do not recognize each other,

- Thus, may we be the founding patriarchs of Zen,

- In our encounter, the Way’s essence we comprehend.

Yinyuan’s eulogy for Bodhidharma is replete with admiration and memorial. As he faced Bodhidharma’s portrait, Yinyuan infused his writing with an ambition akin to that of Bodhidharma: propagating the dharma in an unfamiliar land. This sentiment echoes a timeless mission and commitment spanning thousands of years—to become a founding patriarch of Chan/Zen in a new frontier. It is noteworthy that he had already revealed this ambition on the first leg of his journey out of China to Nagasaki, during which he rendered a poem:

- The meaning of a reed coming from the west, drifting alone in silence,

- Eyes amused by the emerald water, neck craned towards the blue sky.

- Teaching the Dharma, fish and dragons leap, radiance outshines the sun and moon,

- Displaying supernatural powers, all are revealed,

- Yet, arriving at the shore, I forget the reed.

Drawing upon Bodhidharma’s legendary imagery, Yinyuan alluded to his new dharma journey. Although many Chan masters had previously used these same images, none had imbued them with the double meaning in Yinyuan’s poetry. For him, Bodhidharma and himself became intertwined—Bodhidharma served as his inspiration and spiritual pillar, supporting him as he journeyed across the vast ocean at the age of sixty-two and ventured into the unknown world to spread his teachings. Yinyuan’s use of Bodhidharma’s coming from the West was consistent throughout. On his deathbed in 1673, he composed a poem, still having a touch of Bodhidharma in it:

- The Zen Stick from the West shakes with heroic wind,

- Creating the Ōbaku Mountain without any achievement.

- Today, body and mind are both set free,

- Suddenly surpassing the Dharma realm into one true void.

(ibid., p. 5055)

Yinyuan’s heart was filled with joy in the final moments of his life—a joy that stemmed from realizing the infinite emptiness of dharma and completing his mission to come from the West, establish the ancestral temple, and found the Ōbaku sect in Japan. The “Bodhidharma complex” is most evident in Yinyuan’s works, but it can also be observed in those of other Chinese founders of the Ōbaku sect. Like the triptych with Bodhidharma at its center, these Chinese immigrant monks, particularly Yin Yuan, were at the center of establishing a new sect. They viewed Bodhidharma from the past as their contemporary; in the image of Bodhidharma, they carried their grand religious ambitions.

On the other hand, the Chinese immigrant monks’ utilization of Bodhidharma’s image and legends could be seen as a strategic move to appeal to the shōgun and other prominent members of the bakufu. Mu’an, in his eulogy for Bodhidharma in the triptych, recounted the legendary meeting between Bodhidharma and the Liang emperor, a story that the Chinese immigrant monks also repeated. Beyond illustrating Bodhidharma’s deep comprehension of the dharma, this story may have been deliberately retold to the secular authorities to strengthen the ties between monastic leaders and secular elites. By emphasizing the superior position of Chan masters as spiritual guides to those in worldly power, Mu’an could have been conveying their desire to find a suitable dharma vessel to help spread the true dharma to the Japanese people.

The triptych supports this hypothesis as it was composed in 1658, a challenging yet significant year for the Chinese immigrant monks who were still struggling to find sustainable patronage from the high circle and uncertain whether to leave or stay. In 1657, Ryōkei Shosen made two attempts to secure the Shogunate’s support for Yinyuan’s community and to discourage him from returning to China. However, he was unsuccessful in acquiring a purple robe for Yinyuan during his first trip to Edo. Yinyuan was finally summoned to Edo and met Tokugawa Ietsuna 徳川家綱 (1641–1680), the fourth shōgun, and other leading members of the

bakufu at the end of 1658, where he impressed them and secured their patronage. This meeting led to the establishment of Mampuku-ji, the founding temple of the Ōbaku sect, and convinced Yinyuan to stay in Japan (

Baroni 2000, pp. 50–51). Four years after arriving in Japan, the Chinese immigrant monks finally gained a foothold. The success of the Ōbaku sect was only possible with the support of the shōgun and other leading members of the

bakufu. In this challenging endeavor, painting, poetry, and calligraphy played a significant role in expressing the Chinese monks’ religious appeal and connecting themselves with the most potent circle in Tokugawa Japan. On his deathbed, Yinyuan also brushed a farewell poem for Tokugawa Ietsuna:

- From the west, thousands of miles, to the ancient mulberry gate,

- Bestowed land to establish a sect, grateful for the country’s grace.

- Today, with accomplishment complete, humbly giving thanks,

- The river and mountains will always be revered and will last forever.

Yinyuan expressed his gratitude and well-wishes in a poem that marked the end of his years-long partnership with the Shogun. Like Bodhidharma, he shared a deep religious ambition but was fortunate enough to find a reliable ally who helped him achieve his mission.

Lastly, highlighting Bodhidharma in Ōbaku art might also be related to the early modern Edo culture. Using Bodhidharma as a symbol during this period might be particularly significant in linking the Chan pantheon to early modern Japanese society. As Bernard Faure points out, Bodhidharma evolved from the founding patriarch of the Chan/Zen tradition to a “fashionable god”, known as Daruma in Japan. Daruma was widely popular in Tokugawa Japan and was empowered with many protective and fortune-related functions. Moreover, the Daruma cult was a “sudden emergence” right after the end of the medieval period (

Faure 2011, p. 67). It could be conceived that the Daruma cult might have played a significant role in centralizing Bodhidharma’s iconography in Ōbaku art, in which Bodhidharma was often depicted as a foreign monk with robust facial features and exotic nature. Given the Japanese fascination with exotic cultures during the Tokugawa period, Bodhidharma might have been the best candidate for the newly arrived Chinese monks to reach out to Japanese society.