The Dynamics of Islam in Kazakhstan from an Educational Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the significant historical events that have impacted the development of Islamic education in Kazakhstan?

- (2)

- What is the current state of Islamic education in Kazakhstan, including its institutional structures and educational methodologies?

- (3)

- What are the primary challenges affecting Islamic education in Kazakhstan, and what strategies are being used to address them?

- We conducted comprehensive research on the inception and evolution of Islamic education in Kazakhstan, from its initial emergence to the present day. Using the PRISMA methodology, we performed a systematic review of the literature in this field.

- We organized a historical analysis of Islamic education in Kazakhstan and provided an in-depth examination of the relationship between Islam and education, highlighting its significant impact on the development of Islamic education in Kazakhstan.

- We heuristically investigated the essence and substantiated the axiological significance of madrasas and Islamic universities within the context of Islamic education practices. We analyzed the current state of Islamic education, highlighting the specific characteristics of Islamic education in Kazakhstan and its prospects for development as an integral part of the Islamic culture of the Kazakh people.

- We defined and systematized the fundamental value attitudes in Islamic education. Additionally, we developed a methodological framework for examining the teaching methods used in Islamic educational institutions in Kazakhstan. This framework allows us to assess the integration of modern approaches into traditional religious education.

- We formulated practical recommendations for government institutions, which are designed to enhance the quality and effectiveness of Islamic education in the Republic of Kazakhstan; this is a crucial endeavor that demands an integrated approach.

- We created 12 infographics using methods of analysis and synthesis, which include an analytical examination of Islamic education in Kazakhstan.

2. Research Methodology

3. Related Work

4. Islamic Education in Kazakhstan

4.1. Historical Overview of Islamic Education in Kazakhstan

4.1.1. Early Period

4.1.2. Golden Horde

- -

- 13–15th Centuries: In the early 13th century, the spread of Islam in Central Asia and Kazakhstan was slowed by the Mongol conquest, which led to the migration of new ethnic groups, including various Turkic and Mongol tribes adhering to traditional religions. The Mongol invasion led to the destruction of many cities, scientific and cultural centers, as well as mosques and madrasas, which caused significant damage to the trade routes of the Great Silk Road.

4.1.3. Kazakh Khanate

- -

- The 15–18th centuries: During the Kazakh Khanate period, Islamic education continued to evolve. The establishment of madrasas became increasingly common; these institutions educated not only future religious leaders but also representatives of the secular elite. The foundation of a state on the land that is now Kazakhstan was significantly influenced by Islam over a period spanning from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

4.1.4. Russian Empire

- -

- The 19th Century: During the Russian colonization of Kazakhstan, Islamic education faced pressure as Tsarist authorities sought to integrate the region into the secular framework of the empire. Many madrasas were closed or restricted in their activities (Alpyspaeva and Abdykarimova 2022).

4.1.5. Soviet Period

- -

- The 20th Century: With the advent of Soviet rule, Islamic education was severely secularized. Religious schools were closed and religious practice was restricted. However, at the end of the Soviet period, a process of revitalizing religious life began (Bigozhin 2022). This period was characterized by the atheistic policy of the state. In the period 1917–1929, as the author (Arapov 2011) showed, there was relative freedom in the attitude of the Soviet leadership toward Islam. From 1917 to 1923 in Russia, there was an active process of displacement of Christianity, within which militant atheism began to occupy an important place in religious policy. In (Ahmadullin 2022), French researchers Bennigsen and Lemercier-Lelkege (1981) noted that after a civil war characterized by aggressive actions against religious institutions, the Soviet government adopted a policy of relative tolerance toward Islamic institutions, avoiding confrontations for several decades.

4.1.6. Independent Kazakhstan

- -

- From 1991 onward: After Kazakhstan gained independence, an active restoration of Islamic education began (Podoprigora 2020). New madrassas and Islamic universities were opened, and active construction of mosques began.

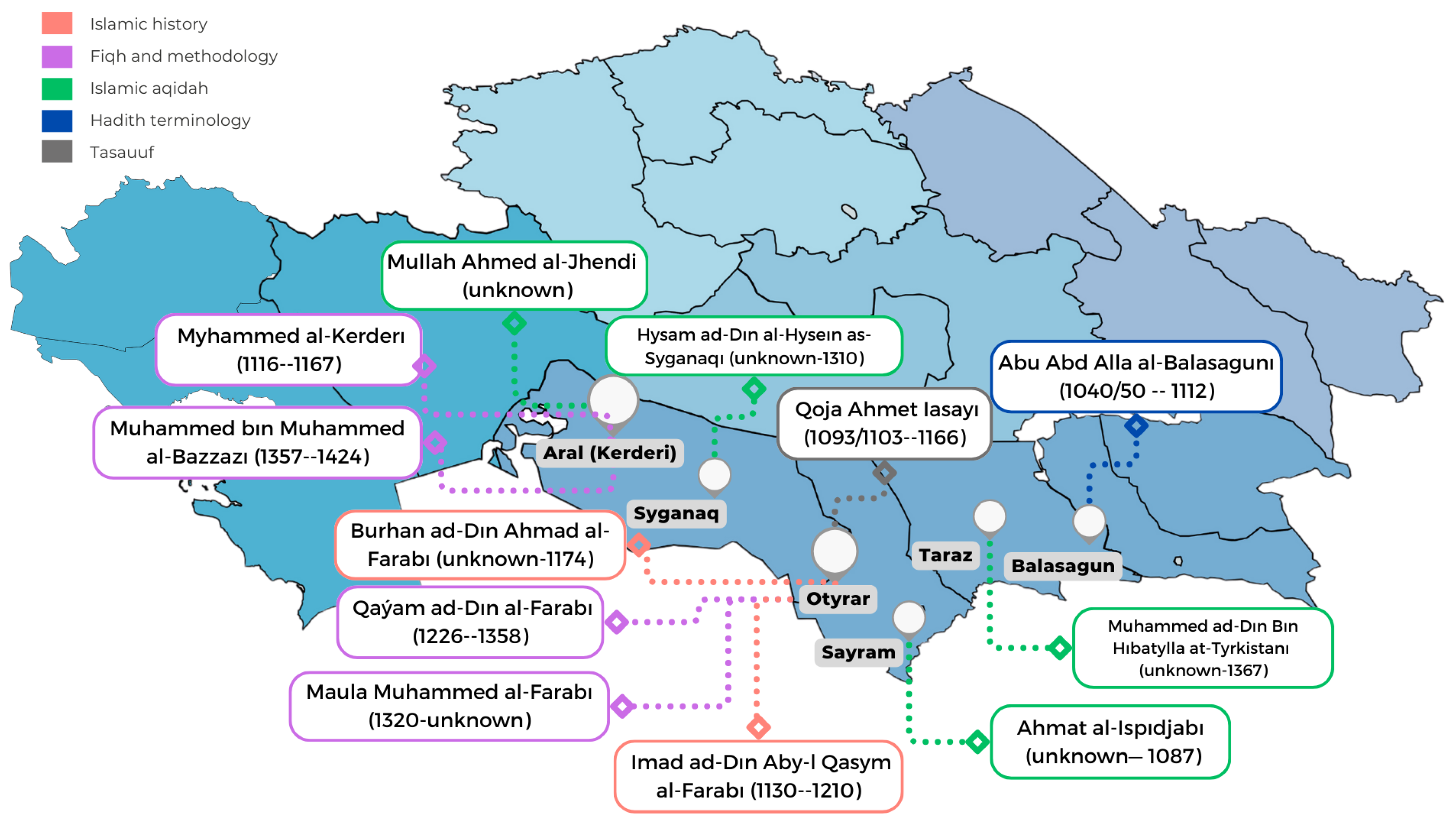

4.2. Scholar Theologians of Central Asia and Kazakhstan

- Ahmad al-’Attabi (d. 586/1190);

- Fakhr al-Din Qadihan al-Uzgandi (d. 592/1196);

- Abu ’Ali ibn Sina (d. 427/1037);

- Abu’l-Barakat al-Nasafi (d. 710/1310–1311);

- Shams al-A’imma al-Khalwani (d. 448/1056–1057);

- Abu Zayd al-Dabusi (d. 430/1038–1039);

- Sadr ash-Shari’a (d. 747/1346);

- Fakhr al-Islam al-Pazdawi (d. 482/1089);

- Burhan al-Din al-Marginani (d. 593/1197);

- al-Sadr al-Shahid (d. 536/1141);

- ’Umar al-Habbazi al-Hujandi (d. 691/1292);

- ’Abd al-’Aziz al-Bukhari (d. 730/1330);

- Abu’l-Fadl al-Kirmani (d. 543/1148–1149);

- Shams al-A’imma al-Sarakhsi (d. 481/1087–1088);

- Abu’l-’Ala’ al-Zahid al-Bukhari (d. 546/1151);

- al-Burhan al-Nasafi (d. 787/1386);

- Radi al-Din al-Sarakhsi (d. 544/1149–1150);

- Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (d. 333/944–945);

- Abu’l-Yusr al-Pazdawi (d. 493/1100);

- Husam al-Din al-Ahsikati (d. 644/1247);

- Jarallah al-Zamakhshari (d. 538/1144);

- ’Ali al-Isbijabi (d. 480/1087–1088);

- Siraj al-Din al-Saqqaqi (d. 626/1229);

- Husam al-Din al-Signaki al-Yasawi (d. between 1311–1315);

- Amir Katib al-Itqani al-Farabi (d. 758/1357);

- Mansur al-Qa’ani (d. 775/1373–1374).

- Abu ’Ali ibn Sina (Avicenna)—one of the most famous and influential scholar-philosophers of the Middle Ages, whose works had a tremendous impact on European and world medicine;

- Abu Mansur al-Maturidi—the founder of the Maturidite school in Sunni Islam, which played a key role in shaping the theological foundations of faith.

- Jarallah al-Zamakhshari—a renowned Islamic scholar who wrote many works on grammar, theology, and the interpretation of the Qur’an.

- Burhan al-Din al-Marginani—author of Hidayah, one of the most important and influential works in Islamic law by the Hanafi school.

- Abu’l-Barakat al-Nasafi and al-Burhan al-Nasafi—both made significant contributions to Islamic jurisprudence and theology.

- Shams al-A’imma al-Sarakhsi—known for his works on Islamic law, especially in the field of commercial and criminal law.

- Skillful use and dissemination of the traditions of the Egyptian school of the Hanafi madhhab;

- Expansion of provisions on civil relations (mu’amalat) and trade transactions (buyu’), achieved by reducing the section of the work on “Ritual” (’ibadat);

- Capturing and preserving the many aspects of local economic, social, and cultural life for historical record;

- Introducing and developing a comparative examination of the provisions of the Hanafi and Shafi’ite theological and legal schools.

- Burhan al-Din Ahmad al-Farabi (unknown–1174);

- Imad ad-Din Abu-l Qasim al-Farabi (1130–1210).

- Kauam ad-Din al-Farabi (1226–1358);

- abd al-Fafur al Kerderi (unknown–1166)/Muhammad al-Kerderi (1116–1167);

- Hafiz ad-Din al-Kerderi (-)/Muhammad bin Muhammad al-Bazzazi (1357–1424);

- Maula Muhammed al-Farabi (1320–unknown).

- Molla Ahmet al-Zhendi (-);

- Husam ad-Din al-Hussein as-Syghanaqi (unknown–1310);

- Akhmat al-Ispijabi (unknown– 1087);

- Muhammad ad-Din Bin Hibatullah at-Turkistani (unknown–1367).

- russianӘbu ’Abd Allah əl-Balasaguni (1040/50–1112);

- Kozha Ahmet Yasawi (1093–1103–1166).

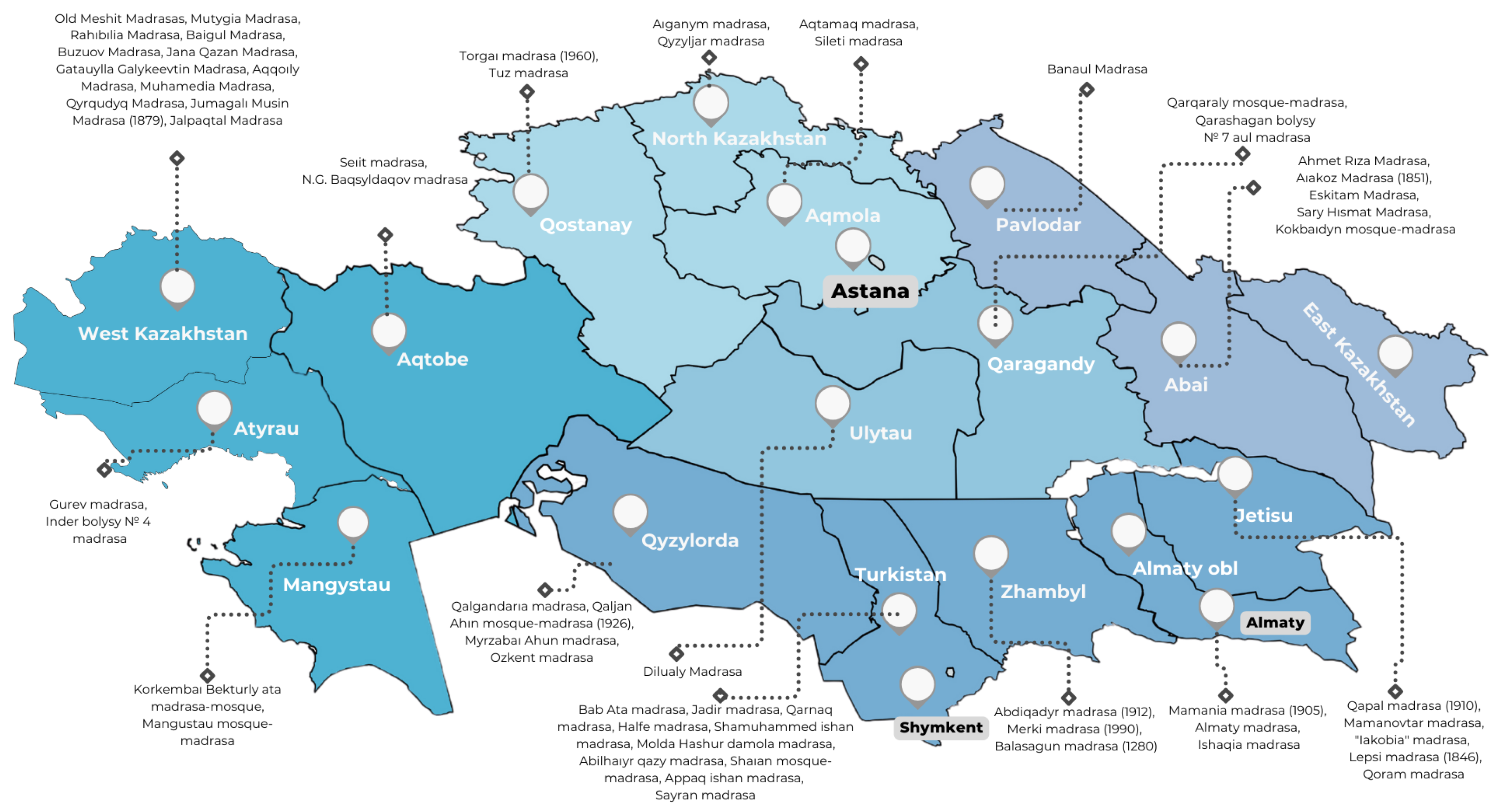

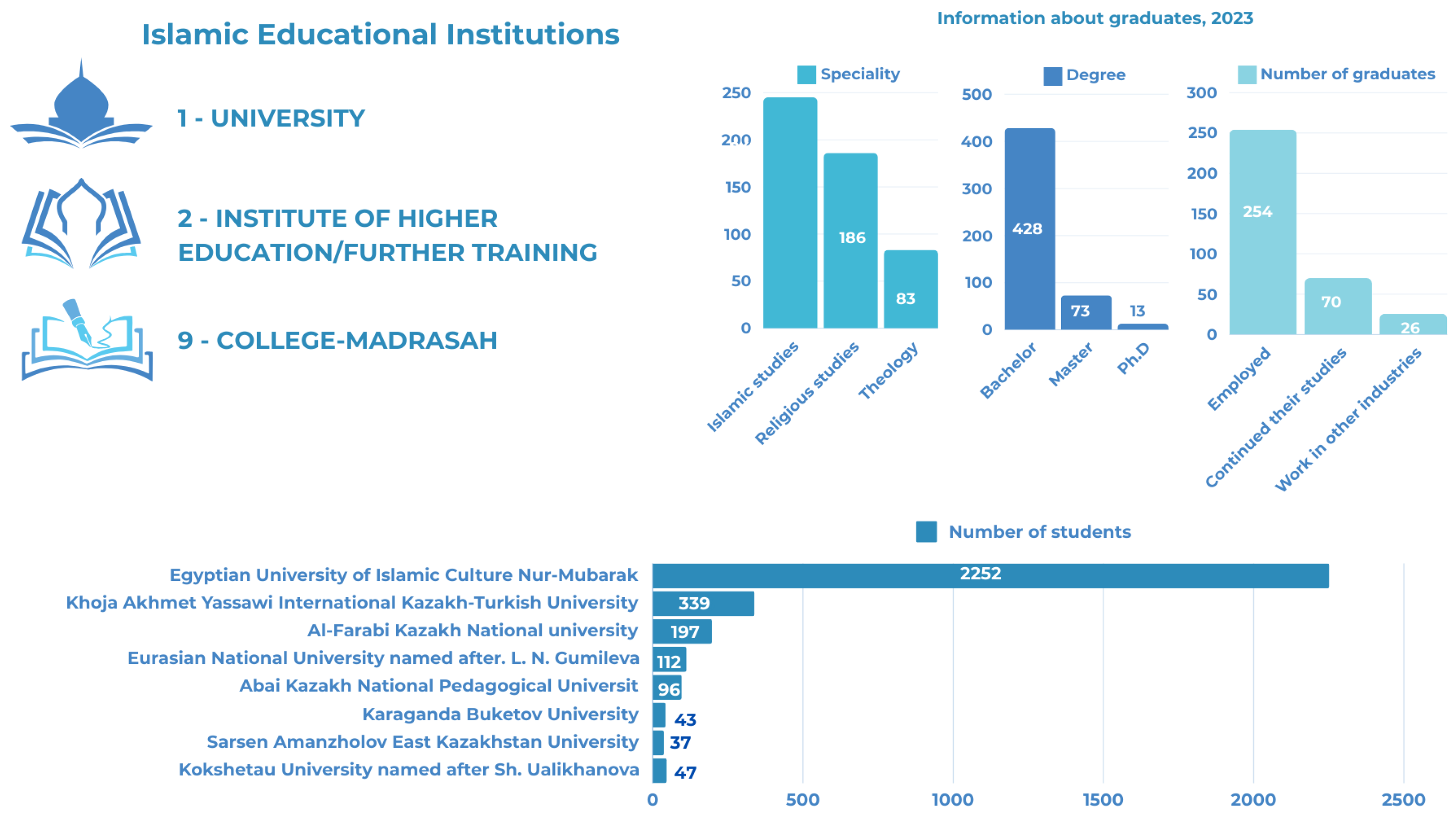

4.3. Current Status of Islamic Education in Kazakhstan

- -

- Courses in religious literacy and memorization of Quranic Suras at mosques;

- -

- Preparatory courses designed by applicants to religious educational institutions;

- -

- Charitable institutions providing religious education;

- -

- Training centers for elders that teach the recitation of Suras of the Qur’an on a professional level;

- -

- Madrasas (colleges);

- -

- Higher education institutions and educational institutions providing religious education after higher education;

- -

- An institute for improving the knowledge and qualifications of imams.

- -

- Emancipation of religious consciousness, which led to the revival of traditional culture and strengthening of moral values.

- -

- Increased activity of religious associations, reflecting the growth of religious identity, especially among young people.

- -

- Influence of illegal religious groups, causing a response from authorities in the form of increased religious education.

- -

- Politicization of religious activity, expanding the influence of religion on politics, culture, and education.

- -

- Changes in ideological and spiritual values, contributing to the growth of religious values consciousness in society (Nadirova et al. 2016).

- -

- Despite the significant number of graduates, there is a shortage of specialists, especially in the field of Islamic studies and theology.

- -

- Staff shortages vary from one region to another due to factors such as staff turnover, a concentration of educational institutions in southern Kazakhstan, and other social factors.

- -

- The staffing issue is particularly acute in regions such as Astana, Almaty, Atyrau, Aktobe, Zhambyl, Mangistau, and Turkestan.

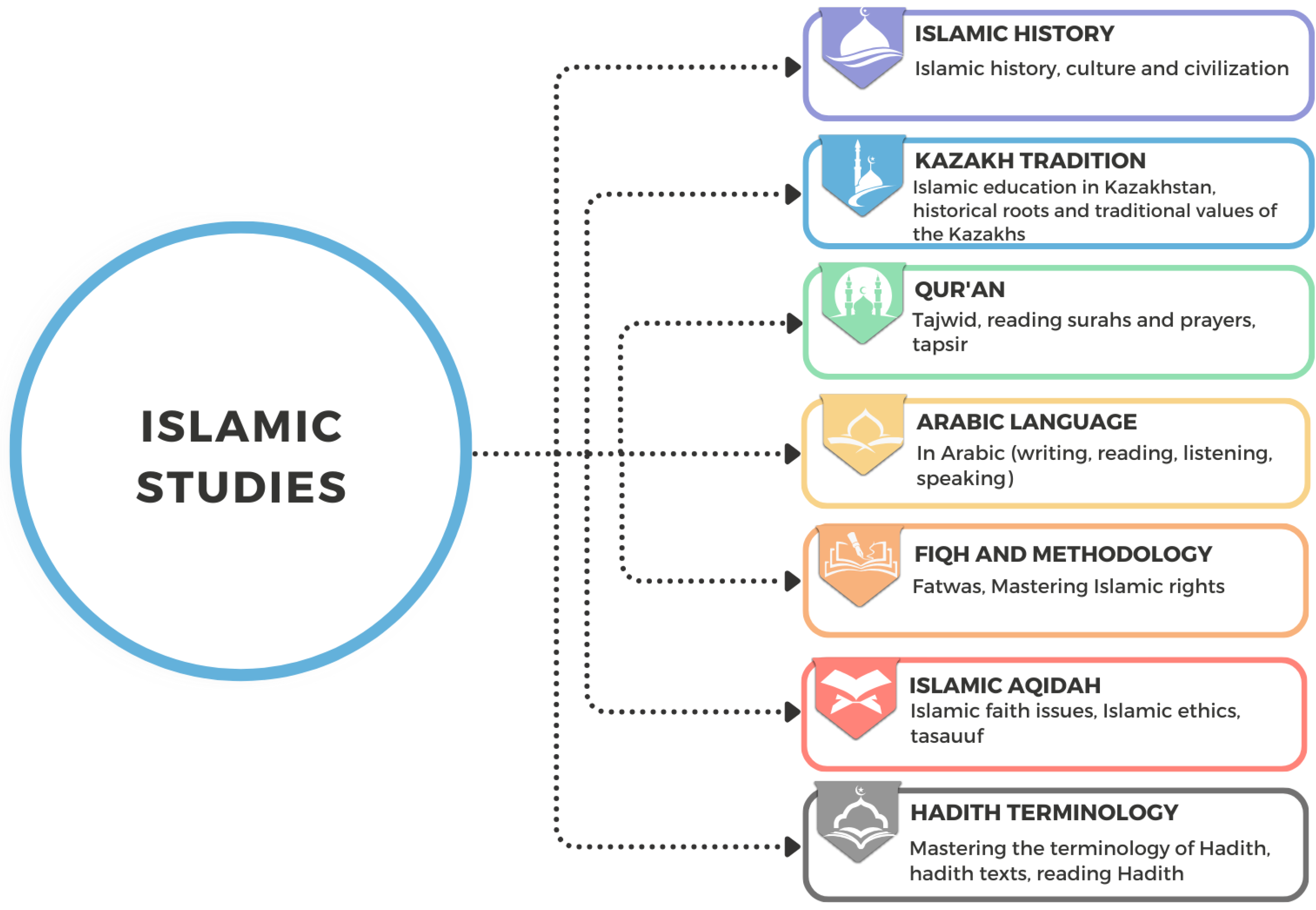

4.4. Pedagogical System of Education in Islam in the Territory of Kazakhstan

- Islamic history: This section covers the history, culture, and civilizational aspects of Islam.

- Kazakh tradition: This refers to Islamic education in Kazakhstan as well as the historical foundations and customs of the Kazakh people.

- Tajwid: This involves the art of correctly reading the Quran, along with the recitation of Suras and prayers. Tafsir, the interpretation of the Quran, is also covered in this section of the religious text.

- Arabic language: This section covers Arabic language abilities such as reading, writing, listening, and speaking in Arabic.

- Fiqh and Methodology: This course examines Islamic jurisprudence and covers a variety of issues, including fatwas and the application of Islamic rights.

- In the sixth section, known as Islamic Aqeedah, topics such as Islamic faith, ethics, and tasawwuf (Sufism) are discussed.

- Hadith terminology is the seventh section, and its primary objective is to teach students how to read hadith, comprehend hadith texts, and learn hadith terminology. The fact that each of these domains is connected to the others demonstrates that, when taken as a whole, they contribute to the understanding of Islamic knowledge.

4.5. Perspectives on Islamic Education and Specific Recommendations to Improve the Islamic Education System in Kazakhstan

- -

- The modern Islamic education system in Kazakhstan is confronted with obstacles that have a negative impact on both its current state and its potential for future growth. Additionally, there are considerable chances for its improvement and incorporation into the larger educational and cultural environment of the country. These prospects are simultaneously available. Integrating Islamic education with modern educational standards in Kazakhstan requires a comprehensive approach that includes updating curricula, using new technologies, and strengthening the links between Islamic educational institutions and the wider educational system.

- -

- The SAMK and the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan should conduct an audit of all Islamic educational institutions of different levels operating in the Republic of Kazakhstan to determine their place in the unified system of Islamic religious education for their licensing, to adopt appropriate regulatory and legal acts.

- -

- The SAMK and members of the Council of Ulema, with the involvement of employees of the Ministry of Education as consultants, should build a hierarchical system of Islamic education and adopt unified educational standards, where it is necessary to disclose the norms and values of traditional Islam in religious disciplines.

- -

- Develop scientific and methodological concepts of traditional Islam as a means to preserve internal public integrity, stability, secular principles, and religious identity while preventing and resolving religious contradictions. This is achieved through a comprehensive study of Islamic values, shaped by the spiritual experiences throughout the history of Kazakhstan.

- -

- Establish clear criteria and standards for courses and programs in Islamic educational institutions, ensuring alignment with national educational standards. Accredit Islamic educational programs at the national level to ensure their recognition and validity.

- -

- Integrate traditional Islamic education with modern educational standards and technologies. This includes updating curricula, introducing new teaching methods, and using digital technologies.

- -

- In Islamic educational institutions, implement electronic textbooks, educational applications, and online courses that can supplement traditional learning are being considered.

- -

- Implement courses that span multiple disciplines. Develop education programs that combine Islamic studies with other areas of study, such as Islamic economics or Islam and international relations (examples of possible integration). It is necessary to intensify the attraction of applicants to madrasa colleges by including them in the curriculum disciplines aimed at the broad intellectual development of students, in addition to teaching the fundamentals of Islam.

- -

- Maintaining high-quality education and training in Islamic educational institutions presents a key challenge. It is important to attract qualified teachers, provide access to quality teaching materials, and support research facilities. Increasing the number of teachers with scientific degrees would not only enhance the quality of education but also strengthen the teaching staff, thereby boosting the reputation of these institutions among prospective students.

- -

- Host ongoing training sessions for educators working in Islamic educational institutions; focus on contemporary instructional strategies and integrating technologies into the classroom.

- -

- Develop the infrastructure of educational institutions and improve materials and technical support.

- -

- Strengthening research activities in Islamic educational institutions can contribute to the development of new knowledge and approaches in the field of Islamic sciences. Expand the methodological basis of the general scientific and conceptual apparatuses.

- -

- Provide grants and funding for research projects in Islamic sciences that can contribute to the integration of Islamic and modern knowledge.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAMK | Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kazakhstan |

| USSR | Union of Soviet Socialist Republics |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

References

- Abdugulova, Baglan, Aizhan Kapaeva, and Gabit Kenzhebaev. 2012. Stories on the History of Kazakhstan. Almaty: Almatykitap Baspasy, p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Abuov, Aidar. 1997. The Worldview of Khoja Akhmet Yasawi. Almaty: Institute of Philosophy MN-AS RK. [Google Scholar]

- Achilov, Dilshod. 2012. Islamic Education in Central Asia: Evidence from Kazakhstan. Asia Policy 1: 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilov, Dilshod. 2015. Islamic Revival and Civil Society in Kazakhstan. In Civil Society and Politics in Central Asia. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, pp. 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadullin, Vyacheslav. 2022. Some Aspects of Foreign Historiography of State-Muslim Relations in the USSR. Islam in the Modern World 2022: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseev, Aleksei. 2008. Special Model of the Functioning of Administrative and Legal Institutions of the Khanates of Transoxiana. In Rakhmat-Name: Sat. Articles to 2008. pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Alpyspaeva, Galya A., and Gulmira Zhuman. 2022. Islamic Discourse in the State Confessional Policy of the Soviet Government in Kazakhstan in the 1920–1930s. Bulletin of the L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University Historical Sciences Philosophy Religion Series 138: 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpyspaeva, Galya A., and Sholpan Abdykarimova. 2022. Muslim Educational Institutions in Kazakhstan under the Anti-Religious Policy of the Soviet State in the 1920s. European Journal of Contemporary Education 11: 314–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alsabekov, Muhammad. 2013. Khoja Ahmed Yassawi and the Spread of the Sufi Branch of Islam in Kazakhstan. Bulletin of the Academy 3: 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Aminov, Takhir M. 2022. Islamic Pedagogical Renaissance: Formation and Substantiation of the Phenomenon. Perspectives of Science & Education 59: 506–17. [Google Scholar]

- Arapov, Dmitry. 2011. State Regulation of Islam in the Russian Empire. Pax Islamica 2: 68. [Google Scholar]

- Ayagan, Yerkin S., Sara K. Mediyeva, and Jannur B. Asetova. 2014. Muslim Schools and Madrasahs in New Tendency on the Basis of Islam Culture in Bukey Horde Re-Formed by Zhanghir Khan. Life Science Journal 11: 255–58. [Google Scholar]

- Badagulova, Zhansaya. 2017. Religious Institutions and Religious Education in Kazakhstan. Master’s thesis, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Sakarya Üniversitesi, Fatih, Istanbul. [Google Scholar]

- Baitenova, Nagima. 2012. Akhmet Yasawi Is the Founder of the Turkic Branch of Sufism. Bulletin of KazNU. Philosophy, Cultural and Political Science Series 39: 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Balapanova, Alya, and Abdirakhym Asan. 2012. Islam in Kazakhstan: Modern Trends and Stages of Development. Bulletin of KazNU. Philosophy, Cultural and Political Science Series 38: 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bartold, Vasily. 1963. Turkestan in the Era of the Mongol Invasion. Moskva: Vostochnaya literatura, vol. 1, p. 763. [Google Scholar]

- Baygaraev, Nurlan. 2016. XIX Asyrdyn Sony–XX Asyrdy Bas Kezndeg Kazak Dalasyndagy Musylmandyk Bilim Take Tarikhynan. Bulletin of KazNU Historical Series 81: 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bektenova, Madina K. 2017. Problematization of the Issue of Islamic Education in the Post-Secular World. European Journal of Science and Theology 12: 135–48. [Google Scholar]

- Beloglazov, Albert. 2013. The Influence of Islam on Political Processes in Central Asia. Kazan: Kazanski Universitet, p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- Bigozhin, Ulan. 2022. Becoming Muslim in Soviet and Post-Soviet Kazakhstan. Ketmen 1: 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bobrovnikov, Vladimir. 2007. Identity, and Politics in the Post-Soviet Space. East Afro-Asian Societies History and Modernity 1: 207–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of National Statistics. n.d. Bureau of National Statistics of the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan; Astana: Bureau of National Statistics. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Committee on Religious Affairs of the Ministry of Culture and Information of the Republic of Kazakhstan. n.d. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/din/documents/details/643128?lang=en (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Dadin, Aqilbek. 2021. The History of the Development of Traditional Islam in Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Science Education 1: 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Doolotkeldieva, Asel. 2020. Madrasa-Based Religious Learning: Between Secular State and Competing Fellowships in Kyrgyzstan. Central Asian Affairs 7: 211–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duishembieva, Jipar. 2020. ‘The Kara Kirghiz Must Develop Separately’: Ishenaaly Arabaev (1881–1933) and His Project of the Kyrgyz Nation. In Creating Culture in (Post) Socialist Central Asia. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- Erpay, Ilyas, Hazret Tursyn, and Zikriya Jandarbek. 2014. Religious Education in the Religion-State Relations after Independence of Kazakhstan. Asian Social Science 10: 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgendorf, Eric. 2003. Islamic Education: History and Tendency. Peabody Journal of Education 78: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilesbekov, Bizhan, Kerim Shamshadin, Azamat Zhamashev, and Ergali Alpysbaev. 2020. Ahmad Al-Isfijabi—As a Representative of the Hanafi Mazhab in the Turkestan Region. Bulletin of Shakarim University Engineering Science Series 3: 373–78. [Google Scholar]

- Imanjusip, Raushan, and Zhanerke Rystan. 2019. Religious Issues in the Scientific Works of Shokan Ualikhanov. Bulletin of the Eurasian National University Named after LN Gumilyov Series: Historical Sciences Philosophy Religious Studies 3: 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Isakhan, Mukhan, and Akmaral Satybaldieva. 2021. Kazakhstani Islam Tarikhs. Muftiyat Baspasy: Nur-Sultan. [Google Scholar]

- Iskhakov, Damir M. 2019. About the Book by Yulai Shamiloglu ‘Tribal Politics and Social Structure in the Golden Horde’. Turkic Studies 2: 146–50. [Google Scholar]

- Islam in Kazakhstan. n.d. Қазақстандағы Ислам. Available online: https://kazislam.kz (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Izmailov, Iskander L. 2012. Adoption of Islam in the Ulus of Jochi: Causes and Stages of Islamization. Social Natural History XXXVI: 26–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, Irina. 2017. Religious studies education in Kyrgyzstan: Origin, development, prospects. In History of Religious Studies. Bishkek. pp. 177–82. [Google Scholar]

- Janguzhiyev, Maksot, and Gulfairus Kabdulovna Zhapekova. 2022. Interaction of Kazakh and Tatar Cultures: Historical and Sociocultural Analysis. Journal of History 107: 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyrov, Kutlug-Bek B. 2020. From Philosophy to Educational Thought in the Study of Aspects of Islamic Culture. BBK 1 E91. p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Kairbekov, Nurlan. 2015. The Heritage of Domestic Theologies in the Light of the Study of Traditional Islam. Alatoo Academic Studies 3: 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Karimov, Naim. 2021. From the History of Islamization of the Turks of Central Asia. Otan Tarihi-Domesti History 3: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kartabayeva, Yerke, Bakytkul Soltyeva, and Ainura Beisegulova. 2015. Teaching Religious Studies as an Academic Discipline in Higher Education Institutions of Kazakhstan. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences 214: 290–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, Michael, Raoul Motika, and Stefan Reichmuth. 2010. Islamic Education in the Soviet Union and Its Successor States. London and New York: Routledge, p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, Adeeb. 2021. Islam in Central Asia 30 Years after Independence: Debates, Controversies and the Critique of a Critique. Central Asian Survey 40: 539–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasanov, Nodirkhon, Torali Kydyr, and Khamidulla Tadzhiyev. 2022. The End of the 19th and the Beginning of the 20th Century an Overview Turkistanian Religious and Enlightenment Literature (Saryami, Muhayyir, Hazini Example). Turk Kulturu ve Haci Bektas Veli-Arastirma Dergisi 101: 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Khatiev, Anuar. 2023. Improving the Mechanism of Interaction Between Government Bodies and Religious Associations. Master’s thesis, Academy of Public Administration under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Astana, Kazakhstan; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Knysh, Alexander, Nagima Baitenova, Azamat Nurshanov, and Dias Pardabekov. 2019. The Role of Religious Literacy in Counteracting New Islamist Movements in Kazakhstan. Central Asia & the Caucasus 20: 88. [Google Scholar]

- Kramarovsky, Mark. 2016. Crimea and Rum in the XIII-XIV Centuries (Anatolian Diaspora and Urban Culture of Solkhat). Golden Horde Review 1: 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kylychev, Akylbek. 2016. On the History of the Karakhanid State. International Journal of Experimental Education 10: 206–10. [Google Scholar]

- Makdisi, George. 1979. The Significance of the Sunni Schools of Law in Islamic Religious History. International Journal of Middle East Studies 10: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and The PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 151: 264–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, Alexander. 2014. Teaching the Islamic History of the Qazaqs in Kazakhstan. In Islamovedenie v Kazakhstane: Sostoyanie, Problemy, Perspektivy. Astana: ENU, pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Muminov, Ashirbek. 2018a. Sufi Groups in Contemporary Kazakhstan: Competition and Connections with Kazakh Islamic Society. Sufism in Central Asia, July 9, pp. 284–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muminov, Ashirbek. 2018b. Traditional Islam in Kazakhstan: Historical Data on the Continuity of Traditions. Bulletin of the L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University 1: 107–13. [Google Scholar]

- Muratkhan, Makhmet, Yerzhan Kalmakhan, Imamumadi Tussufkhan, Akimkhanov Askar, and Okan Samet. 2021. The Importance of Religious Education in Consolidating Kazakh Identity in China: An Historical Approach. Religious Education 116: 521–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzakhodzhayev, Kuanysh, and Zhuldyz Tulibayeva. 2018. On Certain Questions Concerning Education in Jadidist Schools in the Kazakh Steppe (the Late 19th-the Beginning of the 20th Centuries). Bygone Years 50: 1684–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafayeva, Anar, Yktiyar Paltore, Meruyert Pernekulova, and Issakhanova Meirim. 2023. Islamic Higher Education as a Part of Kazakhs’ Cultural Revival. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies 10: 103–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafina, Raushan. 2010. From the History of the Spread of Islam Among the Kazakhs (XIV–XVIII Centuries). Vestnik L. N. Gumilev Named after ENU 3: 276–80. [Google Scholar]

- Muzykina, Yelena V. 2022. Islamic Religious Education in Kazakhstan: Applying Futures Studies to Skyrocket the Reform. World Futures Review 14: 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadirova, Gulnar, Shynar Kaliyeva, Anar Mustafayeva, Dariga Kokeyeva, Maiya Arzayeva, and Yktiyar Paltore. 2016. Religious Education in a Comparative Perspective: Kazakhstan’s Searching. Anthropologist 26: 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurtazina, Nazira. 2011. Satuk Bogra Khan and the Spread of Islam in the Karakhanid State. Bulletin of KAZNU Historical Series 3: 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nurtazina, Nazira. 2021. Islam in the History of Kazakhstan: New Approaches and Results of Studying the Problem over the 30th Anniversary of Independence (1991–2021). Bulletin of KazNU. Historical Series 102: 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oblokulov, Abdurashid, Shuxrat Urakov, Dilnoza Kosimova, and Anna Pondina. 2020. Abu Ali Ibn Sina: Pages of the Life of a Great Scientist. A New Day in Medicine 4: 563–64. [Google Scholar]

- Peshkova, Svetlana. 2014. Teaching Islam at a Home School: Muslim Women and Critical Thinking in Uzbekistan. Central Asian Survey 33: 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikov, Dmitry. 2020. Central Asia in the Context of World Politics. Permian: Permian State National Research University, p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Podoprigora, Roman. 2020. Legal Framework for Religious Activity in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan: From Liberal to Prohibitive Approaches. Oxford Journal of Law and Religion 9: 105–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysbekova, Shamshiya, Ainura Kurmanaliyeva, and Karlygash Borbassova. 2018. Educating for Tolerance in Kazakhstan. CLCWeb Comparative Literature and Culture 20: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabyrgaliyeva, Nazgul. 2022. Kazakhstan Batys Ondegi Dasturli Islam Okilderinin Rukhaniagartushylyk Kyzmeti (XIX Y. Ekinshi Zhartysy—XX G. Bass). Almaty: Al-Farabi atyndagy Kazakh University. [Google Scholar]

- Sadvokassov, Shakhkarim, and Rymbek Zhumashev. 2023. Islamic Revival in Kazakhstan from the Historical Perspective (1991–2020). Journal of Al-Tamaddun 18: 263–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagdiev, Khabib. 2015. Sincere Attitude to the Ruler in Islam. Sociosphere 2: 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sarsembayev, Marat. 2015. The Kazakh Khanate as a Sovereign State of the Medieval Era. Astana: Institute of Legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan, p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- Seidmukhammed, Abdunaim, Absattar Derbisali, Omirzhanov Yesbol, and Daulet Kozhambek. 2015. Political, Legal, Religious Reforms of the Altyn Orda in Its Early Years. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6: 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitakhmetova, Natalya, Daurenbek Kussainov, Zaure Ayupova, Gulsaya Kuttybekkyzy, and Marhabat Nurov. 2020. The Essence and Content of Islamic Education in the Republic of Kazakhstan: Theoretical and Methodological Foundations. The Bulletin 5: 270–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitakhmetova, Nataliya L., and Madina K. Bektenova. 2018. To the Problematization of the Dialogue of Religions as a Dialogue of Civilizations. Study of Religion 4: 100–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serikbay, Khazhy Oraz. 2018. Islam of the Great Steppe. Astana: Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kazakhstan, p. 280. Available online: https://www.muftyat.kz/static/libs/pdfjs/web/viewer.html?file=/media/muftyat/book_6350.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Shagirbayev, Almasbek, Kerim Shamsheddin, Alay Adilbayev, and Bakhitzhan Satershinov. 2015. Islam and Modernism in Kazakhstan Mashkur Zhusup’s Religious Views. European Journal of Science and Theology 11: 189–97. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikemelev, Mukhtarbek. 2010. Cultural and Civilizational Aspects of Kazakh Identity. Current Issues in the Humanities and Sciences 10: 139–45. [Google Scholar]

- Shapoval, Yulia, and Madina Bekmaganbetova. 2021. Hijra to ‘Islamic State’ through the Female Narratives: The Case of Kazakhstan. State Religion and Church in Russia and Worldwide 3: 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, Yulia, and Tatyana Lipina. 2023. Islam in Kazakhstan in the Conditions of Coronavirus Pandemic: Testing with Mediatization. Adam Lemi 95: 142–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagulov, Murat, Tansholpan Zholmukhan, Kairat Kurmanbayev, and Rashid Mukhitdinov. 2023. Some Trends in Islamic Education, Shaping the Spiritual and Cultural Values of Youth under the Influence of COVID-19 (Experience of Madrasa Colleges in the Republic of Kazakhstan). European Journal of Contemporary Education 12: 1410–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sectoral Qualifications Framework for Religious Studies. n.d. Available online: https://career.enbek.kz/storage/ork/docs/1715327582%D0%9E%D0%A0%D0%9A.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- The Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kazakhstan. 2020. The Hearth of the Muslims of Kazakhstan 30th Anniversary of Spiritual Administration. Nur-Sultan: Muftiyat Publishing House, p. 308. Available online: https://www.muftyat.kz/kk/book/36023/ (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Tarasova, Natalia, Irina Pastukhova, and Svetlana Chigrina. 2022. Electronic Educational Resources as a Didactic Tool for Digital Transformation of General Education: Problems of Use. Perspektivy Nauki i Obrazovaniya—Perspectives of Science and Education 59: 518–32. [Google Scholar]

- Utkelbayeva, Zulfiya. 2019. Features of the Imam Abu Hanifa Methodology. Journal of Philosophy, Culture and Political Science 67: 109–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utyusheva, Larisa. 2022. History, Culture, and Traditions of the Kazakh People. Monograph: Litres. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bruinessen, Martin 2012. Indonesian Muslims and Their Place in the Larger World of Islam. In Indonesia Rising: The Repositioning of Asia’s Third Giant. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 117–40.

- Waghid, Yusef. 2014. Islamic Education and Cosmopolitanism: A Philosophical Interlude. Studies in Philosophy and Education 33: 329–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarlykapov, Akhmet. 2008. Islam Among the Steppe Nogais. Moscow: Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology named after Miklouho-Maclay RAS. [Google Scholar]

- Yemelianova, Galina M. 2017. How ‘Muslim’ Are Central Asian Muslims? A Historical and Comparative Enquiry. Central Asian Affairs 4: 243–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerkin, Ayagan, Botakoz Abdrakhmanovna Zhekibayeva, Sayat Kurimbayev, Amanay Myrzabayev, and Issatay Utebayev. 2018. The Teaching Policy of Imperial Russia Directed to ‘Foreign’ People Including the Kazakh. Astra Salvensis 20: 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yunusova, Ayslu. 2017. Autonomy of Bashkir Islam: To the 100th Anniversary of the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Bashkortostan. Bulletin of the Ufa Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences 4: 105–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zakhay, Arnagul, Kenshilik Tyshkhan, and Saira Shamakhay. 2022. The Problem of the Traditional View of Islam in Kazakhstan. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 26: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinkub, Abdolhossein. 2004. Islamic Civilization. In Andalus. Tehran: Sokhan Press, p. 237. [Google Scholar]

- Zengin, Mahmut, and Zhansaya Badagulova. 2017. Religion and Religious Education in Kazakhstan. Karaelmas Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi 5: 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhapekova, Gulfairus, Zhuldyz Kabidenova, Shamshiya Rysbekova, Aliya Ramazanova, and Kenzhegul Biyazdykova. 2018. Peculiarities of Religious Identity Formation in the History of Kazakhstan. European Journal of Science 14: 109–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhitenev, Timofey Evgenievich. 2010. Islam in Russia: Milestones of History. Tolyatti: Vestnik Volzhskogo Universitet Named after VN Tatishchev, vol. 4, pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zholmukhan, Tangsholpan, Murat Smagulov, Nurlan Kairbekov, and Roza Sydykova. 2024. Conceptual Approach to Understanding the Social Aspects of the Educational Potential of the Islamic Studies. Pharos Journal of Theology 105: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beisenbayev, B.; Almukhametov, A.; Mukhametshin, R. The Dynamics of Islam in Kazakhstan from an Educational Perspective. Religions 2024, 15, 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15101243

Beisenbayev B, Almukhametov A, Mukhametshin R. The Dynamics of Islam in Kazakhstan from an Educational Perspective. Religions. 2024; 15(10):1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15101243

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeisenbayev, Baktybay, Aliy Almukhametov, and Rafik Mukhametshin. 2024. "The Dynamics of Islam in Kazakhstan from an Educational Perspective" Religions 15, no. 10: 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15101243

APA StyleBeisenbayev, B., Almukhametov, A., & Mukhametshin, R. (2024). The Dynamics of Islam in Kazakhstan from an Educational Perspective. Religions, 15(10), 1243. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15101243