Abstract

This study explores the representation of radical and anti-radical ideologies among German Islamic TikTok creators, analyzing 2983 videos from 43 accounts through qualitative content analysis. The results reveal two main content clusters: religious practice involving social/lifestyle issues and political activism around Muslim grievances. Victimization, found in 150 videos, was the most common indicator associated with radicalization and emerged as a source of political activism and subversive discourse. Overall, indicators of radicalism were scarce, suggesting that visible mainstream Islamic creators do not exhibit high levels of radical ideology. However, this also reflects a selection bias in the design of this study, which systematically overlooks fringe actors. In addition, religious advocacy was the most common topic (1144 videos), serving as a source of guidance and motivation, but was occasionally linked to sectarianism and rigid religious interpretations. Male creators posted more religious/theological videos; female creators posted more lifestyle videos. However, gender distinctions are limited due to the low representation of female creators (6). Some topics, such as the hijab, served as an intersection between religious practice and politicized narratives. This study highlights TikTok’s role in promoting diverse ideological views and shaping community engagement, knowledge sharing, and political mobilization within Germany’s Muslim digital landscape.

1. Introduction

At a time when digital platforms are shaping social discourse, TikTok has emerged as a prominent platform, attracting ubiquitous audiences to its fold. TikTok’s sharp rise in popularity in recent years not only highlights its attractive design and entertaining nature but also underscores the way in which users find representation and a sense of belonging within the platform’s communities (Bhandari and Bimo 2022; Hiebert and Kortes-Miller 2023; Schellewald 2023). Marginalized groups in particular use TikTok to build virtual communities and exchange insights about their identities and experiences, addressing their marginalization and injustices (Hiebert and Kortes-Miller 2023; Cervi and Divon 2023; Eriksson Krutrök and Åkerlund 2023; Delmonaco et al. 2024; Vizcaíno-Verdú and Aguaded 2022). This dynamic is particularly visible for minorities within majority contexts. One such minority group is German Muslims. As an intersectionally marginalized group—affected by factors such as religion, gender, and ethnicity and race due to the migration background of many members—German Muslims experience widespread discrimination and social exclusion (Di Stasio et al. 2021; Fernández-Reino et al. 2023; Lewicki and Shooman 2020). In addition, public discourses render German Muslims highly visible and associate them with various emotions, including fear (Schiffauer 2006; Wigger 2019). These dynamics add layers of complexity to the challenges faced by German Muslims as they navigate their multiple identities and search for belonging. As a minority, they have to manage daily life in an environment where their cultural and religious practices are alienated and problematized. Moreover, they find themselves under constant scrutiny—visible but often ignored, with their needs, grievances, and the complexities of their lives largely unrecognized.

This situation is not unique to German Muslims. Many Western Muslims, particularly in Europe and North America, find themselves in a similar juxtaposition of hypervisibility and marginalization (Pratt and Woodlock 2016). This has created a need for spaces where they can explore and navigate their identities. Since the advent of the Internet, Western Muslims—including German Muslims—have turned to online spaces for entertainment and lifestyle purposes similar to their peers, as well as to engage with their hybrid identities and experiences, creating and organizing communities that reflect their cultural and religious idiosyncrasies (Piela 2012; Rozehnal 2022). This makes studies on Muslim representation online particularly intriguing, as they reflect inherent trends and logics of social media, such as entertainment and lifestyle content, while incorporating unique aspects of religion and identity specific to Muslim communities.

The demographic profile of social media platforms, particularly TikTok, whose user base includes a significant number of young people (Bestvater 2024; Koch 2023, p. 3), aligns well with the predominantly young demographic of German Muslims; 43% of German Muslims are 24 and younger (Pfündel et al. 2021, p. 4). This means that a significant proportion of German Muslims belong to the age groups typical of digital natives, primarily Generation Z and Generation Alpha. This demographic alignment underscores the high potential for social and political mobilization of German Muslims through these platforms. Furthermore, it indicates that German Muslim youth are particularly well positioned to use TikTok for a variety of purposes, ranging from cultural–religious expression to socio-political advocacy.

Despite the prominent presence and active participation of Muslim content creators on social media, and the wide range of topics they cover—from presenting modest fashion to negotiating Islamic identity in Western contexts (Duffy and Hund 2015; Hasan 2022; Zaid et al. 2022; Echchaibi and Hoover 2023; Wheeler 2014)—there is a noticeable gap in systematic academic research focusing on this group in the context of TikTok and Germany.

However, there is growing interest and literature about TikTok as a hub for extremist content and a facilitator of radicalism. In fact, TikTok has not been immune to the emergence of radical actors. Various research has identified extremist content on TikTok from various ideological backgrounds, including political and religious extremism (O’Connor 2021; Little and Richards 2021). As digital landscapes become the new frontier for ideological struggles, TikTok has also become a channel for radical German actors seeking new audiences (Hartwig and Hänig 2022). These actors skillfully navigate digital currents to disseminate content designed to convince their audiences of their worldview and prescriptions, i.e., to radicalize them. Exposure to extremism through well-targeted communication is fundamental to the radicalization process and lays the groundwork for the spread of radical ideologies. Arguably, equally important is the interplay of factors such as demography, individual psychosocial make-up, and the wider socio-political context, each of which plays a significant role in an individual’s susceptibility to extremist ideas (Kruglanski et al. 2014; McGilloway et al. 2015; Booth et al. 2024). This creates a multifaceted matrix that is often, but not always, observed in those who become radicalized (Campelo et al. 2018). What is essential, however, is the compelling and persuasive nature of radical ideologies communicated by extremist actors, which ultimately convinces and ensnares individuals to adopt extremist thinking (Vergani et al. 2020; Awan 2017).

As part of the “pull factors” within radicalization, radical communication often appeals to individuals by addressing their deep-seated psychological needs, such as meaning, social recognition, identity, belonging, closure, and purpose (Pfundmair et al. 2024). The potency of their propaganda lies in the capitalization on vulnerability, offering a sense of clarity and community to those struggling with societal or personal grievances. Radical groups seek to captivate individuals, in part, through narratives that are congruent with the private histories or perceived injustices of their target audiences. Just as some Muslims use TikTok to find representation and process issues specific to their experiences in Germany, such as discrimination or the search for religious guidance appropriate to their lived realities, content creators have emerged who resonate with these needs and grievances. These creators are producing videos on these issues, and some are also positioning themselves as authorities on religious guidance (Hartwig et al. 2023). However, a fraction of German Islamic content creators often uses these interactions to offer objectionable solutions and advice, targeting the platform’s predominantly young user base.

Despite its relevance, there is a notable gap in academic research on radical communication on TikTok, particularly in the German context and in relation to Muslim audiences. Currently, existing academic research on religious extremism on TikTok in Germany can generally be divided into two approaches: monitoring projects that provide overviews of the activities of various actors (e.g., Hartwig and Hänig 2022), and in-depth, mostly qualitative analyses of specific actors (e.g., Ali et al. 2023). Both approaches often, but not exclusively, focus on content creators who have previously gained notoriety on other social media platforms. Comprehensive and comparative research on online content creation by Muslim creators in Germany, especially studies that combine both of these approaches and focus specifically on TikTok, remains limited. However, given TikTok’s unique technical capabilities and affordances, it is important to further explore the platform and tailor research designs to these characteristics. In the case of online radicalization through exposure to extremist material, TikTok has some interesting characteristics that merit attention for research.

TikTok, like other platforms, recommends content based on a user’s presumed interests. However, TikTok’s approach to content curation, as evidenced by its “For You” page, differs from the norm in that it does not prioritize followers as much (Zhang and Yigun 2021). The visibility of accounts on TikTok depends less on the number of followers they have and more on the popularity, engagement, and relevance of their content. Liking and following certain users significantly influence the content suggested by TikTok’s algorithm (Boeker and Urman 2022). However, unlike Instagram or YouTube, the For You page interface on TikTok is not designed to show a feed of posts in chronological order by followed accounts. This results in a user experience that is inherently less continuous, coherent, or chronological in terms of content from followed accounts. As a result, it can be argued that viewers contextualize videos not in a strict sequence of posts from followed accounts, but as a collection of individual pieces that, while recognizably patterned, are experienced in a seemingly non-linear rather than sequential order. Given that current research often comes with extensive prior knowledge of specific actors, there is a tendency to interpret content with a depth of context that the average viewer may not share, as their experience on the platform is less actor-focused and perhaps less in-depth. This suggests that each TikTok video may be more effectively analyzed as an individual entity, rather than as part of a collective narrative tied to the creator.

Most importantly, the prevalence of anti-radical content—material that constitutes the exact opposite of extremist narratives and potentially has a preventive, rather than radicalizing, effect—receives little to no attention in the current literature on online radicalization. To thoroughly assess the potential for radicalization on TikTok from the creator’s perspective, one must consider the contrast—the presence of messages that could have a countering or preventive narrative. An oversimplification can obscure the complexities of engagement with radical content, including the potential for anti-radical messages to help prevent radicalization, or instances where known radical actors may also disseminate positive messages. The latter is crucial, as extremist recruitment could use inherently positive messages as an entry point into more radical ideologies. Understanding radicalism in this context requires contrasting analysis with anti-radical narratives that address the same themes or issues from opposite perspectives, highlighting the range of framing possibilities for certain phenomena.

In light of this existing research gap, this study aims to improve the understanding of (anti-)radical content within the German Muslim TikTok community. More specifically, the focus is on German Muslim content creators who produce Islamic content, as opposed to those who identify as Muslim but do not produce religious content at all. It is guided by two research questions:

- What are the different radical and anti-radical contents presented in the videos of German Islamic TikTok creators?

- What topics are frequently associated with radical or anti-radical content within this community, and how do these associations shape the narratives of German Islamic TikTok videos?

This research offers a new systematic categorization of (anti-)radical content, applying a multidimensional approach to radicalism. By conducting an analysis of individual videos, our study focuses on their apparent meaning as standalone units, rather than attributing meaning by extrapolating from other content. This approach aims to replicate the perspective of an average TikTok user encountering and interpreting each video independently on their ForYouPage for their apparent content. Such an approach contrasts with analyses that interpret videos as reflective of a creator’s overall ideology, often seeking more subtle and subliminal patterns. Arguably, this approach is more restrictive because it avoids assuming associations between videos, which may in fact occur. However, we argue that this analytical strategy allows for a closer approximation of how content is perceived, given the affordances of the ForYouPage. Additionally, this study focuses on popular accounts with significant followings. This brings an ambivalence to this study; for one, it definitely causes a selection bias that given content moderation the fringes of problematic content could be overlooked, but at the same time, it allows us to analyze the content produced in the German Islamic TikTok mainstream, which we argue is more representative of the experience of this user demographic.

Furthermore, this study identifies the topics presented in these videos. Identifying topics not only provides an overview of the discourses prevalent among content creators but also allows for the reconstruction of the associations between (anti-)radical content and the topics typically addressed with them. The identification of both topics and (anti-)radical content is achieved through the qualitative coding of 2983 videos from 43 accounts, which is subsequently quantified to determine the prevalence of coded elements and their combinations. We also collected the metadata on each video, such as likes, views, shares, comments, and the use of hashtags and video descriptions. These data help to contextualize our sampled videos within the broader performance metrics on TikTok, offering insights into the impact of actors and videos.

To present the central findings of our research, we structure this paper as follows: Initially, we present our methodology, detailing the sampling and coding strategies employed. Our findings are then discussed in four subsections. The first, “Victimization, Grievances, and Political Action”, focuses on content that portrays Muslims as victims or recipients of grievances, analyzing narratives of victimhood and the associated political positions. The second subsection, “Religious Advocacy, Everyday Life, and Guidance”, explores the discourse on religious guidance and ideological differences within Muslim communities. Given the centrality of the headscarf debate in the qualitative findings of the first and second subsections, a distinct third subsection providing a qualitative summary of the headscarf debate in our data is designated (“The Headscarf Debate: A Spectrum of Reactions”). The fourth subsection, “Topics, Popularity, and Gender”, examines how different topics are approached by various genders and their effectiveness in generating reach. Both the first and second subsections will be presented using both summaries and examples. These will include analyses of the co-occurrence of (anti-)radical content and various topics, as well as qualitative examples.

Our paper concludes with a discussion that synthesizes our approach and findings, offers implications for future research, and highlights the socio-political relevance of this study. In doing so, we contribute to the scholarly discourse on online radicalism, content creation, and digital Muslims and Islamic studies. By providing a nuanced and comprehensive approach, we offer insights into how different religious and political ideas are presented through short-form video content. Through this endeavor, this study fills a crucial gap in the limited systematic data available on Muslim users on TikTok. Not only does it provide valuable insights into the existence, diversity, and framing of political and religious content, but it also offers a foundation for future research to explore this field further. Additionally, the findings are relevant from a socio-political standpoint, helping to guide actionable approaches based on the data presented.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Strategy

The data for this study consist of a retrospective collection of all videos from 2022 from the sampled accounts. The sampling process, which began in early 2023, was designed to identify Muslim TikTok accounts that produce content explicitly referencing the Islamic religion or religious themes. This focus narrows the research to concentrate on religious ideologies and identities associated with Islam or being Muslim, rather than encompassing all the values and beliefs held by self-identifying Muslims, even when there is no reference to their Muslim identity or Islamic heritage. The initial phase involved querying TikTok videos using search terms that combined “Islam” or “Muslim” with “Deutsch” or “German”. We then included the accounts that posted videos related to Islam or being Muslim in a German context. Videos and accounts suggested by TikTok’s search options are typically those that are trending or popular for a given term, aligning with our intent to focus on the mainstream and prominent actors of Muslim TikTok in Germany. This served as a proxy for what is commonly consumed within that digital domain.

This strategy was a precursor to a snowball sampling approach, which was integral to expanding the sample. Reviewing each account led to the utilization of TikTok’s suggestion feature, which recommends similar users—usually three—providing a pathway to additional accounts for potential inclusion. This cumulative process continued until new accounts no longer significantly contributed to the diversity or relevance of the sample. Moreover, the sample was enhanced by including accounts labeled in prior research as radical or extremist (see Hartwig and Hänig 2022; Hartwig et al. 2023). The inclusion of these accounts was necessary to capture central figures in the German discourse on religious extremism, maintaining a comprehensive sample for this study. Initially, the sampling procedure yielded around 150 accounts. To ensure that the resulting data are practical for analysis, we limited the timeline of videos for each account to 2022. Limiting the data to that year allowed us to establish a timeframe that ensured overlap in content creation between the accounts. As online content creators, including Muslims, frequently engage with and comment on current events relevant to their identities (Ali et al. 2023), this approach enabled the inclusion of multiple perspectives on the same trends or events. To ensure inclusion of accounts actively producing content in 2022, we established a criterion requiring at least four videos posted within the year.

Our snowball sampling naturally yielded German-speaking accounts, and those where German was not the primary language were excluded. This decision was made to focus on content specifically catered to a German-speaking audience, acknowledging that this may have excluded some German actors producing content in other languages. Additionally, a few accounts based in Austria or Switzerland, as indicated by the profile or self-identification in the content, were removed to maintain this study’s focus on the German national context. However, since nationality was not systematically measured, this process is not entirely free of potential error. Nonetheless, when qualitatively coding all videos from 2022, no Austrian or Swiss context emerged from any account that did not explicitly mention being based in Germany. This process, combined with the substantive criterion that accounts must regularly produce Islamic or Muslim content, defined as content that includes Islam as a religion, religious doctrines, or being Muslim from accounts that self-identify as Muslim, our strategy refined the sample to 43 accounts (see Table 1 and Table A1). In this context, “regularly” refers to accounts that engage with Islamic topics or discussions on multiple occasions throughout their active period, rather than in isolated or singular instances. These accounts were subsequently used for data collection and underwent a qualitative analysis of their video postings from the year 2022.

Table 1.

Sample description.

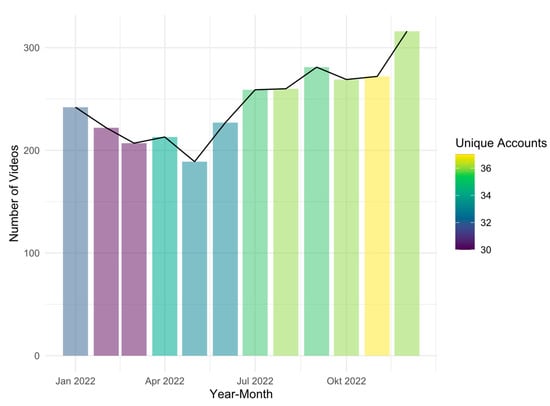

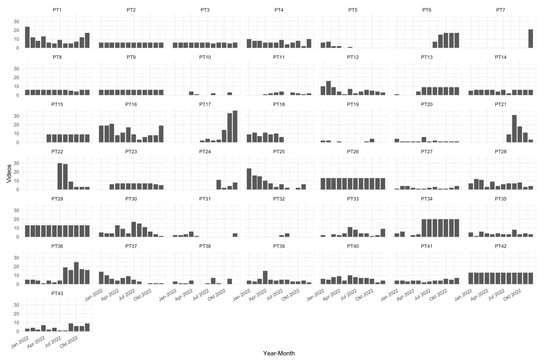

As might be expected, our study faced several limitations, in addition to the selection bias caused by purposefully selecting popular accounts given our substantive interest. Firstly, there was a considerable variance in the volume of videos across the sampled accounts, leading to unequal representation. Secondly, the feasibility of qualitative analysis was challenged by accounts with an extensive number of videos, some reaching into the hundreds or thousands in 2022. For those accounts, we employed a random sampling strategy, selecting an equal number of videos each month during their active periods. This approach capped the total number of videos at no more than 160 per account. Lastly, the temporal activity of the accounts was not uniform, causing disparities in the representation of time-sensitive events or factors. This irregularity in account activity posed constraints on drawing evenly distributed conclusions across different time frames (see Figure A1 and Figure A2). The total number of videos from our 2022 sample amounted to 2983.

2.2. Data Collection

The data collection for this study was structured in two sequential phases, involving web scraping and professional transcription services. In the first phase, web scraping was employed to extract data from all 2983 videos posted in 2022 across the 43 TikTok accounts. This process involved collecting metrics such as video URLs, titles, posting dates, durations, and engagement statistics such as views, likes, comments, and shares, along with audio file titles, hashtags, and video descriptions. After completing the web scraping, we proceeded to the second phase: each video posted in 2022 was systematically downloaded and submitted for a verbatim transcription via “abtipper.de”. The service involved a detailed transcription of both the audio and visual elements of the videos. Audio content was transcribed verbatim, while visual elements such as on-screen text, gestures, facial expressions, and relevant background imagery were described in detail. Focusing on transcribing both auditory and visual content was crucial, as these transcriptions provided the primary foundation for subsequent data analysis, guaranteeing that no potential message or communication was overlooked. The transcribed material was carefully matched with the scraped data using the unique video ID from each TikTok link.

2.3. Analysis and Coding

In the qualitative analysis of the collected data, a hybrid coding procedure integrating deductive and inductive techniques was employed. The deductive component drew upon theoretical frameworks in areas such as radicalism, radicalization, extremism, (religious) fundamentalism and dogmatism, and theories around closed-mindedness, value complexity, and closure. After reviewing the relevant literature, a list of indicators for radicalism was deduced (see Table A2), which includes indicators on the following:

- Behavioral extremism and radicalization: this encompasses the choice of means to achieve ideological goals, ranging from violence or jihadism to non-extremist actions like legal political activism (Peels 2023, p. 3; Cassam 2021, p. 61 ff; Moskalenko and McCauley 2009; Moghaddam 2005, p. 165; Hegghammer 2014; Wibisono et al. 2019; McCauley and Moskalenko 2017, p. 212);

- Cognitive extremism and radicalization: this relates to the beliefs, attitudes, and values adopted, such as religious monism, authoritarian or violent theology, sectarianism or takfirism, dichotomization (“us-them”), dehumanization, and delegitimizing the present socio-political status quo or system (Moghaddam 2005, pp. 163–65; Peels 2023, pp. 3, 5–6; McCauley and Moskalenko 2017, pp. 211–12; Cassam 2021, p. 39 ff; Hegghammer 2014; Wibisono et al. 2019; Kruglanski 2004);

- Conative extremism and radicalization: this pertains to the specific aspirations of actors, for example, re-establishing past governments and dynasties, like the Ottoman Empire, or overthrowing the current government (Hegghammer 2014; Wibisono et al. 2019).

Indicators of anti-radicalism, such as videos that exemplify phenomena opposing those associated with radicalism and are therefore linked to countering or preventing it, are based on the exact same factors. The list of radicalism indicators includes “victimization”, which refers to narratives of victimization involving Muslims or Muslim nations. While this indicator is not inherently indicative of radicalism or extremism, it is included here as a potential facilitator. Existing research suggests that perceived in-group injustice and discrimination have an effect on radicalization, or at least are more prevalent among those with radical ideologies (Emmelkamp et al. 2020). However, it is important to note that discussions of victimhood are also a part of regular public discourse and political debate, particularly for marginalized groups. In general, many of these codes alone do not constitute unambiguous radicalism; rather, in combination, they form a specific message that could be classified as such.

We are adopting dominant scholarly debates here that may fall within the lens of a state-security perspective, focusing on violent, illegal, or anti-constitutional behavior, or structural definitions that emphasize socially relevant elements of extremism, generally or specifically for one religion. However, some elements reflect a discourse that arbitrarily targets Muslims. Monism—an understanding of religion that denies pluralism and promotes a monolithic view of faith—is, to some extent, inherent to religion itself, as many religions claim a singular way of understanding the world. In our case, we have coded this from the perspective of Islamic faith, noting that when mainstream Islamic belief includes a plurality of valid opinions, it may get reduced to a singular perspective. This, in itself, is not problematic unless combined with other factors that enable extremism. Similarly, “delegitimization” is often part of various political discourses aimed at societal improvement. Again, context matters here, and these are the contexts we intend to explore. Similarly, “dichotomization” is conceptually fuzzy because, while friend–foe divisions can be problematic given their severity, generally separating the world into “us” and “them” is integral to the formation of any organized group; particularly when social exclusion is involved. We adopt this diverse analytical approach not as a sign of conceptual agreement but to broaden our analytical lens and observe, given these assumptions, what can be identified on TikTok.

While radicalism indicators were coded for the ideological message of the videos, topics were coded for the topical content or setting. Concurrently, inductive coding was applied to the identification of topics directly from the video transcriptions. This process used an iterative approach to topic discovery and refinement. Initial coding rounds identified preliminary topics, which were then systematically reviewed and consolidated. Subsequent rounds of coding allowed for the emergence of new topics and the refinement of existing ones. This iterative process continued until theoretical saturation was reached, where no new significant topics emerged, and the existing categories adequately captured the diversity of content in the data. The topics identified through this process are listed in Table A3. Similar to the indicators, multiple topics were coded per video, ultimately not exceeding 4 topics per video. Nearly 2000 of the 2983 videos had Islamic or Muslim content, based on the coded topics.

For the coding of radicalism indicators, a method analogous to coding opposing political or party positions was adopted (Kriesi et al. 2012, p. 44 ff): each indicator was coded with a “+1” when present in a video (radicalism) and a “−1” when its opposite was observed (anti-radicalism). This a priori approach allowed for the representation of each indicator and its contraindication, offering a contrasting view of the presence and nature of radicalism indicators within the videos. Up to three indicators were coded per video, allowing for overlap or co-occurrence. The coding instructions focused on clear, apparent meaning, so highly ambiguous or unclear messages were generally not coded, reflecting the restrictive nature of the coding process.

The coding procedure was initiated by two professional coders with backgrounds in Middle Eastern and Islamic studies, respectively. After a thorough training period by the two authors of this paper, that included collaborative coding and evaluation of the same examples, the coders completed their work under the authors’ supervision. The coders were instructed to evaluate each video based solely on its apparent content, without inferring additional information from other videos by the same creator. Once this initial coding was completed, two student assistants with backgrounds in political science and economics were trained in the coding process. They conducted the first set of corrections to the initial coding, which was then reviewed and finalized by the two authors of this paper. Given that the student assistants are in their late teens to early twenties, their involvement brought perspectives from age groups more aligned with TikTok’s young user base, providing valuable contrasts to the assessments made by the initial coders. This approach resulted in a coding process that underwent rigorous reviews and control loops by a total of six coders from different age groups and various academic backgrounds, ensuring a robust and diverse analytical framework.

3. Findings

3.1. Victimization, Grievances, and Political Action

3.1.1. Summary

In the discourse of German Islamic content creators on TikTok, narratives of victimhood are a salient feature, evidenced by “victimization” being the most frequently coded indicator (150 videos). This indicator acts as a key point, shaping distinct directions in political expression and action. The data on co-occurrence with the “victimization” indicator delineate a spectrum of responses that range from constructive engagement to subversive reactions (see Table 2). On one end, instances of “activism” (9), “interfaith harmony” (5), “emancipation” (2), and “anti dehumanization” (1) represent a positive response to victimhood. These indicators suggest content that is geared toward fostering legal political activism, such as protests and advocacy, which are vital to healthy political discourse. “Interfaith harmony” narratives promote dialogue and cooperation across religious lines, while “emancipation” discussions, often centered around the rights and empowerment of women and children, contribute to a more equitable society. The stance against dehumanization (“anti dehumanization”) highlights a commitment to uphold the dignity of all individuals. The “Middle East” remains a constant source of grievance due to the ongoing Israel–Palestine conflict, which resonates deeply among Muslims. The portrayal of Muslims in “media” (30) often triggers discussions about misrepresentation.

Table 2.

Co-occurrences of Radicalism Indicators and Topics with “victimization”.

Conversely, “delegitimization” (6), “dichotomization” (2), “revisionism” (2), “dehumanization” (1), and “monism” (1) reflect a more radical approach to victim narratives. These indicators refer to content that challenges the legitimacy of present democratic institutions (“delegitimization”), promotes binary us-versus-them thinking (“dichotomization”), calls for a return to past Islamic governance structures like the Ottoman Empire (“revisionism”), and engages in dehumanizing rhetoric (“dehumanization”). Both types of approaches are rooted in the same societal issues. Content creators on TikTok navigate this dichotomy, with some leveraging the persuasive power of victim narratives to galvanize positive change, while others may exploit these grievances, leading their audience down a more divisive path.

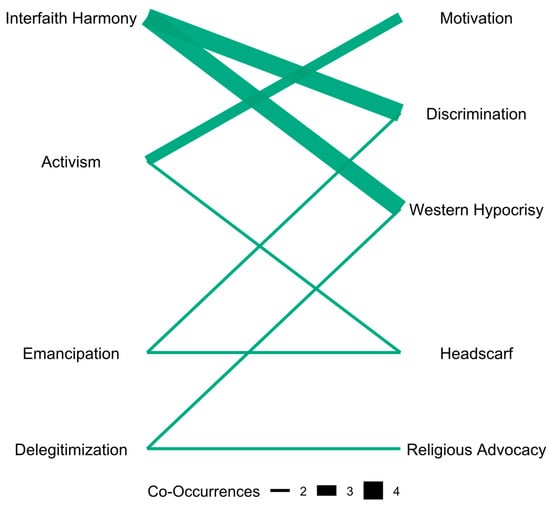

The topics that typically orbit the “victimization” narrative and incite political action are telling of the community’s concerns. A look at Figure 1 reveals the relationships of indicators and topics that relate to victimhood. “Western hypocrisy”, with its focus on the perceived double standards of Western societies towards Muslims, is a frequent touchstone for both positive activism and radical discourse. This is evidenced by its co-occurrence with “delegitimization” (2) on one hand and “interfaith harmony” (4) on the other. Debates surrounding the “headscarf” encapsulate the struggle for religious expression and the associated rights. Interestingly, the headscarf debate is tied to emancipatory content (“emancipation”, 2) and promotes legal activism addressing struggles faced by veiled Muslim women (“activism”, 2). Lastly, “discrimination”, encompassing racism, is a pervasive issue that can either unite communities in a search for justice or be used to exacerbate tensions. The high co-occurrence with “interfaith harmony” (4) and “emancipation” (2) displays a desire for equality in relation to other faith groups and mitigation of their differential treatment. Additionally, a prominent streamline to promote the delegitimization of the socio-political system at hand seems to be tied to religious advocacy (“advocacy”, 2). The fact that this is under the general theme of victimization suggests that certain actors use victimhood to create the necessity for political change, as it portrays Western political systems as failing Muslims or perpetrating their grievances and delegitimizing them through supposed religious doctrines that underline the illegitimacy of those systems.

Figure 1.

Bipartite network of co-occurring topics and indicators within “victimization”. Single co-occurrences omitted. Radicalism indicators on the left side; topics on the right side.

In summary, how Islamic content creators on TikTok respond to the narrative of victimhood—whether through activism, interfaith dialogue, and emancipatory content or via delegitimization, dichotomy, and dehumanizing rhetoric—is indicative of their approach to political action. These responses, while rooted in the same foundational issues, take different trajectories, shaping the contours of radical and anti-radical political expression within the German Muslim community.

3.1.2. Examples

Looking at “Creator PT36, Video 1”, this video offers a critical examination of the German media’s portrayal of the 1992 Rostock-Lichtenhagen riots, with a particular focus on the tabloid newspaper BILD. The content creator contends that BILD has failed to learn from its historical errors and continues to foment animosity towards refugees and Muslims. The creator charges the newspaper with hypocrisy and double standards, positing that BILD’s reportage played a role in exacerbating the riots.

The prevailing narrative within this video is one of victimization, depicting Muslims as subjects of unjust treatment and biased media representation. The content creator’s objectives appear dual: firstly, to unveil the purported hypocrisy and Islamophobic agenda of the German media, especially BILD; and secondly, to heighten awareness within the Muslim community regarding the perceived injustices they endure. By underscoring the media’s role in perpetuating negative stereotypes and inciting hatred, the creator aims to cultivate a sense of shared grievance and collective identity among Muslims. The alternative proposed in this video is a call to action, urging the Muslim community (referred to as “Ummah”) to recognize and expose the “deception” orchestrated by the media. This implies a form of activism intended to counteract the perceived bias and discrimination through heightened awareness and solidarity within the Muslim community.

These observations are congruent with the article’s discussion of victim narratives, which elucidates how content related to themes such as “media”, “discrimination”, and “western hypocrisy” frequently portrays Muslims as victims of injustice and marginalization. The video’s critique of BILD’s coverage and its alleged contribution to anti-Muslim sentiment echoes the article’s assertion that such narratives can engender either constructive activism or more radical stances. The exhortation to expose the media’s “deception” and mobilize the Muslim community can be construed as a form of anti-radical activism, aligning with one of the potential responses to victim narratives delineated in the article. Nevertheless, the video’s emphasis on the collective identity of the “Ummah” and its opposition to the German media could also be interpreted as fostering an “us vs. them” mentality.

In another example, “Creator PT12, Video 1”, a more abstract approach is pursued. This video delves into the portrayal of Muslims in films and television series, highlighting the prevalent stereotypes and negative representations that have shaped public perceptions over time aligning with our findings on the “media” topic and its role in perpetuating biases and misrepresentations of the Muslim community. The creator first presents a list of common tropes associated with Muslim characters in media, such as being depicted as villains, terrorists, aggressive individuals, oppressors of women, or backward and ignorant people. These stereotypes, the creator argues, have been repeatedly reinforced through the film industry, leading to the formation of prejudices among the general public. This critique of media representation resonates with our observations on how Islamic content creators on TikTok often challenge and deconstruct dominant narratives that marginalize or misrepresent their community.

In fact, the video’s emphasis on the long-term impact of these negative portrayals suggests that the creator’s intention is to raise awareness about the insidious nature of anti-Muslim propaganda in popular media. By highlighting how these stereotypes have been perpetuated over years, the creator encourages the audience to critically examine the media they consume while at the same time confirming a possible existing feeling of rejection and discrimination. The video’s assertion that anti-Muslim propaganda operates on multiple levels, including the negative portrayal of Islam in public discourse, further underscores the systemic nature of the issue. This broader critique of societal biases against Muslims resonates with our findings on the “western hypocrisy” code, which captures the perceived double standards and discrimination faced by Muslims in Western contexts.

In previous examples, the target groups are provided with “proof” of hypocrisy in Germany, while other instances emphasize the international context. It appears, however, that critiques on an international level are often intertwined with local realities and vice versa, effectively internationalizing the struggle against perceived Islamophobia and injustice, which is seen as pervasive. This approach aligns with the Islamic narrative of an international community, the Ummah. An example for this is “Creator PT18, Video 1”, which focuses on the international context, critiquing the perceived double standards and hypocrisy of Western countries in their reactions to the Russian invasion of Ukraine compared to other conflicts involving Muslim countries. The creator argues that the wave of solidarity with Ukraine and the hatred against Russia is exaggerated and hypocritical, as similar reactions were not seen when Russia attacked Syria or Libya. He calls the current situation a “fascist Russian hunt”, with sanctions targeting Russian oligarchs, banks, and politicians like Gerhard Schröder for being pro-Putin. The creator compares this to the lack of consequences for the U.S. after the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, which he considers illegal and part of the colonial powers’ actions over the past 200–300 years.

Furthermore, the creator criticizes the differential treatment in Germany of Ukrainian refugees compared to Syrian, Iraqi, and other Muslim refugees, citing media reports that emphasize the “whiteness” and “Europeanness” of Ukrainian refugees, clearly highlighting the perceived double standards and hypocrisy of Western countries in their reactions to conflicts involving Muslim countries versus Ukraine. While also addressing the hypocrisy towards Muslims, the speaker in this instance diverges from previous examples by appearing to accept it. He argues that it is normal and understandable for Westerners to prioritize “their own people”, asserting that Muslims should similarly prioritize their own community.

A notable distinction lies in the proposed call to action. Unlike previous speakers who merely suggested the need to address hypocrisy, this speaker is unequivocal. The call for the establishment of an Islamic caliphate, coupled with the delegitimization of existing Muslim countries, represents a radical position within the spectrum of victim narratives. Nonetheless, this perspective is relatively uncommon.

3.2. Religious Advocacy, Everyday Life, and Guidance

3.2.1. Summary

Religious advocacy (“advocacy”), with 1144 videos, is by far the most coded topic, a part of which can be traced back to our selection of accounts with religious content. However, it marks the relevance that religious teachings, reminders, discussions, and jurisprudence have for these creators. This topic often intersects with elements of “lifestyle” (103), resonating with a wider audience by linking doctrinal teachings to the practicalities of modern life (see Table 3). This engagement with lifestyle topics underscores a discourse that is not merely about religious edicts but about the contextual application of faith in the everyday life—negotiating the “permissibility” (24) of practices and the distinctions between halal and haram within daily routines.

Table 3.

Co-occurrences of radicalism indicators and topics with “advocacy”.

The pronounced overlap between religious guidance on lifestyle matters and the halal–haram discourse reveals a community seeking to reconcile their faith with the complexities of contemporary life. Yet, this quest for religious clarity is deeply entwined with the broader ideological spectrum ranging from rigid and harsh (“merciless theology”, 5) to its antithesis: compassionate and so on (“anti merciless theology”, 64).

The presence of “monism” (9) suggests a subset of content that endorses an uncompromising view of religious interpretation, potentially fostering a uniformity at odds with the diverse realities of Muslim life in Germany. Conversely, “anti monism” (9) reflects a countervailing narrative that embraces multiple interpretations, resonating with a community that values diverse expressions of faith. Similarly, the mention of “sectarianism” (4) within the context of “advocacy” points to the enduring challenges of intra-faith dialogue, where the potential for exclusivity can be countered by a pluralistic ethos (“anti sectarianism”, 1). This dynamic indicates that while religious advocacy on TikTok can be a source of guidance and communal solidarity, it also navigates the delicate lines between unity and division, between the dogmatic and the pluralistic.

In essence, the discourse on religious advocacy, as captured on TikTok, is a reflection of a community in dialogue with itself about the nature of religious observance. The content spans the spectrum from advocating for a prescribed religious lifestyle to challenging the boundaries of traditional interpretations. This diversity is not simply a reflection of individual preferences but a mirror to the entrenched divide between radical and anti-radical religious thoughts, where the clerical guidance provided by content creators is imbued with their ideological leanings on issues like “merciless theology”, “monism”, and “sectarianism”.

In conclusion, the discourse of “advocacy” on TikTok, with its intersection of lifestyle and religious legality, serves as a microcosm of the broader debate on religious life in the digital age. It showcases how the quest for personal religious guidance on lifestyle matters is linked to the ideological divide of religious thought within the Muslim community. The cleavages delineated in these findings reveal the nuanced and multifaceted nature of religious advocacy, highlighting the critical role of content creators in reinforcing various interpretations of faith. The existence of these videos, addressing rulings on haram and halal and transmitting religious knowledge that pertains to lifestyle issues, goes beyond the mere need for religious knowledge. In fact, this content indicates the inherent need of Muslims for guidance on their lives as a minority in a non-Muslim society, where these matters are not socially institutionalized. Moreover, the trend toward societal individualization adds to the need for German Muslims to seek guidance in a cultural landscape where their specific customs, values, and practices cannot be assumed or taken for granted. It could be further argued that these videos are indicative of a need to be integrated into society, fulfilling the basic necessity of navigating within it, showing that they harmonize the realities of both being German citizens and being Muslim. Islamic content creators are on the supply side of this demand, finding diverging ideological ways to meet these needs.

The data further delineate a dichotomy within the Islamic dialogue on TikTok, distinguishing between content with a propensity toward religious discourse and politically charged content. This distinction is particularly salient when contrasted with the findings related to the “victimization” narrative, where political subjects are more prevalent. Here, “advocacy” aligns more frequently with topics of religious permissibility (“permissibility”, 24), morals and ethics (“morality”, 43), and discussions on the afterlife (“afterlife”, 41), indicating a community more engaged with purely theological concerns. This begs the question of how “religious” the politically radical content is of Islamic content creators and vice versa.

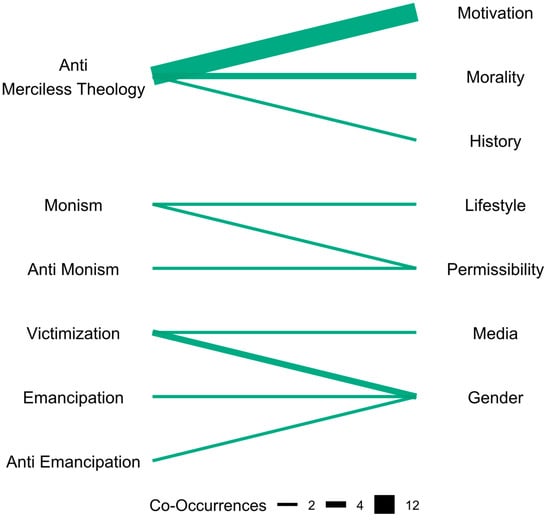

Visiting Figure 2 unveils additional insights. Both “monism” and “anti monism” demonstrate a notable connection to the notion of religious lawfulness (“permissibility”, both 2). This suggests how religious advocacy on the permissibility of various actions is directly linked to jurisprudence, communicated based on monistic or anti-monistic interpretations, which either recognize ambiguities or strictly delineate between haram (forbidden) and halal (permitted).

Figure 2.

Bipartite network of co-occurring topics and indicators within “advocacy”. Single co-occurrences omitted. Radicalism indicators on the left side; topics on the right side.

Another notable co-occurrence intersecting the religious advocacy topic are “victimization” and “gender” (4). This is evidence of a dual framing regarding Muslim women. It illustrates how Muslim women are portrayed by content creators, with one frame being political (“victimization”) and the other religious (“advocacy”), with the three intersecting in this case. This type of content works as a religious advice to Muslim women enduring victimization due to their intersectional identity. “Victimization” and “headscarf” also converge under “advocacy” once, highlighting this intersection of framings.

Lastly, the combination of “anti merciless theology” and “motivation” (12) serves as a message to German Muslims, who are probably young given the TikTok demographics, who may struggle with feelings of guilt, perceived moral deficiencies on their part, or uncertainty about their religious practices and their sufficiency. The prevalent message here is hope and mercy, functioning as pastoral care and dawah (spiritual outreach or religious propagation) simultaneously. This narrative motivates and addresses the realities of temptation and despair, reinforcing a pastoral and encouraging presence within religious discussions.

3.2.2. Examples

Examples for motivational religious advocacy can be found in many cases in our dataset. For example, in “Creator PT1, Video 1”. The content directly addresses Muslims who have committed sins and are feeling remorseful or desperate. The creator reassures the audience of Allah’s forgiveness, emphasizing that no sin is too great to be forgiven. This aligns with the “hope and mercy” message mentioned in the introduction, providing pastoral care by encouraging repentance and reinforcing the belief in Allah’s mercy. In “Creator PT28, Video 1”, a hadith (narration of the Prophet Muhammad) is shared, offering a supplication for times of worry and distress. By providing this practical spiritual tool, the content creator delivers both pastoral care and religious instruction, aiding viewers in coping with anxiety through Islamic practices. This guidance is particularly valuable given the uncertainty arising from the plethora of seemingly contradictory “legal rulings” on TikTok regarding what is “haram” (forbidden) and what is “halal” (permissible). Another short but representative one is “Creator PT20, Video 1” that reinforces the theme of Allah’s boundless mercy, encouraging viewers not to doubt Allah’s forgiveness. It addresses the potential self-doubt and guilt that young Muslims might experience, offering reassurance and hope.

These examples demonstrate how TikTok is being used as a platform for religious advocacy and pastoral care within the German Muslim community. They address common spiritual and emotional challenges faced by young Muslims, offering encouragement, hope, and practical religious solutions. The application of mercy and compassion as a central element of their religious advocacy may fulfill several interconnection functions for these content creators. By addressing common emotional and spiritual struggles among young Muslims, they foster empathy and reduce feelings of isolation. Simultaneously, these videos reinforce core Islamic teachings about Allah’s mercy and forgiveness, making theological concepts accessible and relatable to a young audience. This dual approach not only enhances religious understanding but also strengthens viewers’ spiritual practices.

The creators also foster community building by discussing shared experiences, creating a virtual community space that is especially significant for young Muslims in predominantly non-Muslim environments like Germany. This sense of community may help viewers to feel connected to a larger Muslim group. In addition to serving as a form of dawah, these videos present Islam as a religion of mercy and hope to both Muslims and non-Muslims, potentially countering negative stereotypes and broadening the religion’s appeal. They also provide practical spiritual tools for coping with daily emotional challenges, integrating faith into everyday struggles and affirming the Muslim identity of young German Muslims by bridging their religious identity with their experiences in German society. Lastly, these videos implicitly counter radical ideologies by emphasizing Allah’s mercy and forgiveness, promoting a message of hope and divine acceptance that may protect viewers from more extreme interpretations of Islam. Hence, this would classify as anti-radical religious narratives. Overall, these TikTok videos could contribute to the spiritual and community support, education, and resilience of young Muslims, helping them navigate their identities and integrate more positively into society.

Expanding upon the themes of pastoral care, religious education, and community building, “Creator PT1, Video 2” critiques the behavior of Muslims who focus on exposing others’ faults, addressing a common issue within religious communities: the tendency to judge others while lacking self-reflection. This approach not only fosters personal spiritual growth but also serves as religious education by referencing Islamic teachings that discourage backbiting and urge the protection of fellow Muslims’ dignity. The creator makes these concepts accessible by relating them to everyday scenarios, thus contributing to community cohesion by discouraging divisive behaviors. The video also connects traditional religious teachings with contemporary social issues, particularly how social media behaviors like fault-finding can harm community dynamics. Unlike previous content that provided reassurance, this video adopts a corrective tone, specifically addressing the damaging impact of such behaviors.

Moreover, this critique often intersects with gendered issues, especially in the scrutiny of women’s dress and behavior within the Muslim community. This reflects broader multi-discrimination challenges faced by Muslim women, who endure Islamophobic attitudes in broader society and heightened judgement within their own communities. For example, another creator criticizes women for wearing form-fitting clothing despite wearing a hijab, viewing it as seeking societal approval:

[Video Text (translation)] “They cover their hair but emphasize their body all the more. Because somehow you have to `please` society. They put on body-hugging clothes and call it modern. Dear Ukhti [engl.: Sister], is it really worth it to you? Just for the attention of people. You have taken a big step and covered yourself, but then also take these steps towards Allah and not Shaytan”(Creator PT32, Video 1)

In general, women are often held to higher standards of modesty and behavior, with their choices scrutinized and judged more harshly than those of their male counterparts. Connecting this to the previous analysis, we can see how the criticism of fault-finding behavior within the community, as discussed in “Creator PT1, Video 2”, takes on a gendered dimension. While the original content creator advocated for self-reflection and empathy, the reality is that much of the criticism and fault-finding within the community seems to be disproportionately directed at women.

3.3. The Headscarf Debate: A Spectrum of Reactions

The discourse surrounding the “headscarf” serves as a microcosm of the broader struggle for religious expression and associated rights. As mentioned before, the headscarf finds its discursive place in both religious and political contexts. In Figure 1, the headscarf debate is closely linked to emancipatory content (“emancipation”, 2) and promotes legal activism aimed at addressing the challenges faced by veiled Muslim women (“activism”, 2). This section will delve into qualitative examples that further illustrate the spectrum of responses to these struggles.

Some transcripts reveal a nuanced perspective on the hijab, portraying it not merely as a religious garment but as a potent symbol of identity and resistance. For instance, the statement “Der Hijab ist unsere Krone” (engl.: “The hijab is our crown”) from “Creator PT17, Video 1” transforms the hijab from a mere head covering into a symbol of pride and empowerment. The creator seeks to reframe the narrative surrounding the hijab, challenging negative perceptions and stereotypes. By employing the metaphor of a crown, they aim to instill a sense of dignity and strength among hijab-wearing Muslim women. This framing aligns with the paper’s findings on how Islamic content creators often use TikTok to challenge dominant narratives and assert their identity. In many other cases, male and female content creators alike call upon hijab-wearing women to wear it with pride. These kinds of responses resonate with our findings regarding non-violent answers to victimhood as they can be seen as forms of activism and emancipation while affirming the identity of the target group.

Responses as such can be seen as ways to rationalize or make the practice more bearable. The rationalization of the hijab among Muslim women in Western societies emerges as a complex response to discrimination and perceived injustice. In our findings, it manifests in various forms, such as (1) practical benefits like sun protection and modesty, argued from a more pragmatic than religious standpoint, (2) social and cultural benefits emphasizing identity and community belonging, and (3) religious justifications that view challenges as divine tests and integral to religious practice. These rationalizations, while varied, share a common goal: to help Muslim women justify their choice to wear the hijab amidst societal pressures or discrimination. These justifications serve as a coping mechanism, enabling them to uphold their religious and cultural practices in Western societies.

In “Creator PT12, Video 2”, the creator presents a pragmatic and non-religious argument for wearing the hijab—as an act of liberation from societal beauty standards, challenging the narrative that it symbolizes oppression. They argue that the choice involves either submitting to divine will by wearing the hijab or succumbing to society’s unrealistic beauty pressures, highlighted by statistics on young children’s body image issues and the negative impact of social media on mental health. Furthermore, they discuss the role of the entertainment industry in perpetuating these beauty standards, noting that the societal pressure to conform is more oppressive than wearing the hijab. Acknowledging the challenges posed by an Islamophobic atmosphere in Western societies, the creator calls for community support to combat these negative perceptions and ease the practice of wearing the hijab.

In the TikTok video “Creator PT4, Video 1” titled “Sense & Advantage of the Islamic covering [veiling]”, the content creator uses both religious and pragmatic arguments to rationalize wearing the hijab. The video features a social experiment comparing reactions to a woman in conventional attire versus Islamic covering, illustrating how the hijab protects against unwanted attention and harassment. The creator combines pragmatic benefits, such as protection from environmental factors and social issues, with religious justifications from chapter An-Nur (The Light) of the Quran, emphasizing modesty for both genders. This dual approach aligns with broader Islamic discourse that presents religious practices as solutions to modern social issues, making them more relatable and acceptable to a wider audience. However, the argument oversimplifies complex social issues by implying that women’s clothing choices can prevent harassment, rather than addressing the broader negative societal attitudes and behaviors towards (veiled) Muslim women, which include discrimination on multiple aspects of life.

An example of the latter is “Creator PT16, Video 1”. As a German woman with a hijab and a foreign-sounding surname, she shares her experience of perceived discrimination during a housing search. She recounts how an acquaintance stressed to a potential landlord that she is German, despite her foreign name. The content creator uses this incident to highlight the persistent discrimination in German society against individuals with foreign-sounding names or visible Muslim identity markers. By describing the experience as “traurig” (sad), she expresses disappointment in the continued relevance of national origin or religion in everyday interactions.

In the video “Creator PT42, Video 1”, the content creator addresses a hijab ban in the workplace, expressing frustration and calling for a boycott of businesses that enforce such policies. This highlights not only the discrimination against hijab-wearing Muslim women but also criticizes the perceived hypocrisy in Western claims of tolerance and acceptance. The creator aims to raise awareness, challenge narratives of tolerance, mobilize the Muslim community and allies through economic actions like boycotts, and empower Muslims by underscoring their collective consumer power. The call for a boycott is an example of legal political activism.

The discourse on the hijab and the discrimination experienced by Muslim women in Western societies, as depicted in our analysis, provides essential context for understanding the landscape of religious advocacy in the German Islamic TikTok community. Although the chapter on religious advocacy has already been discussed, it is important to reiterate how the individual stories of discrimination and the justification of religious practices inform broader ideological debates.

Content creators often navigate the fine line between emancipatory discourse and potentially extreme rhetoric, a tension that enriches our understanding of religious advocacy. These dynamics reveal how personal experiences and attempts to rationalize religious practices like wearing the hijab are translated into broader religious discourse on TikTok. This discussion extends into how religious principles are applied to lifestyle and everyday life issues, resonating with prior observations that frame the hijab as a practical response to social challenges. Furthermore, the presence of contrasting indicators like “monism” and “anti monism”, along with “sectarianism” and “anti sectarianism” in the religious advocacy discourse, highlights a community actively engaged in complex debates over religious interpretation and practice within a diverse, secular society. This engagement also showcases efforts to weave religious advocacy into discussions on lifestyle topics.

3.4. Topics, Popularity, and Gender

In examining the landscape of Muslim content creation on TikTok in Germany, a notable distinction emerges in the thematic choices and engagement patterns among male and female creators (see Table 4). This differentiation becomes evident when analyzing data encompassing various topics ranging from lifestyle and personal relationships to religious jurisprudence and societal issues. However, it is important to note that this analysis is based on a limited sample, including only six female accounts, and should be taken with caution. The findings primarily offer preliminary insights, serving as a foundation for further elaboration and research.

Table 4.

Video metrics by topic (descending by avg. views).

Female content creators predominantly engage in topics such as “lifestyle” (39.6%) and “kinship” (12.6%), which encompass daily life elements like clothing, food, travel, and family relationships. This inclination suggests a proclivity towards sharing and consuming content related to personal experiences and everyday life matters. On the other hand, male creators show a penchant for religious or theological topics like religious advocacy (“advocacy”, 30.1% male versus 8.1% female). Another indication for this demarcation is the topic “permissibility” (7.9% male versus 1.1% female), which involves discussions on Islamic jurisprudence, particularly the delineation of permissible (halal) and forbidden (haram) actions within Islam. Such a trend indicates a male-oriented content focus on doctrinal and legalistic aspects of the faith. The analysis of user engagement metrics further illuminates these patterns. For instance, the comedy genre, characterized by humorous and light-hearted content, though moderately represented by female creators (5%) and to a lesser extent by males (0.4%), exhibits high viewer engagement with an average of 552,373 views and 17,150 likes. The brevity of these videos, averaging 20 s, aligns with a general audience preference for concise and entertaining content.

Conversely, topics like conversion, involving narratives and discussions about converting to Islam, despite having less representation and longer average durations (79 s), maintain a substantial viewership. This may indicate a dedicated audience segment interested in in-depth explorations of personal faith journeys and the complexities of religious identity. The engagement trends also hint at varying audience preferences, where shorter, entertaining pieces are more widely viewed and liked, while longer, more contemplative content may find resonance with a more dedicated viewership. This divergence in content consumption underscores the diverse interests of the audience, ranging from seeking quick entertainment to engaging with detailed, thought-provoking discussions. Generally speaking, more serious or analytical videos, like those on topics such as “shirk”, “middle east”, or “history”, tend to be longer on average, likely because the necessary transfer of knowledge demands more time than more casual topics like “comedy” and “lifestyle” require.

In a nutshell, the data suggest distinct gender-based preferences in thematic focus. Female creators tend to gravitate toward topics centered around personal and lifestyle narratives, while male creators are more inclined toward religious and legal discussions. The variation in audience engagement across different video lengths and subjects further suggests a multifaceted audience base with diverse interests. These insights not only shed light on the content strategies of these creators but also might provide an understanding of the audience’s engagement patterns within the specific socio-cultural context of the German Muslim community. Ultimately, this illustrates how the entertaining nature of TikTok and its prevalent attention economy inform Islamic content creators’ practices. We argue that, in part, these creators become members of the overarching TikTok culture and its inherent logic of marketability, making them similar to other creators on the platform, who likewise address lifestyle-related issues and employ comedy. However, they also engage with specific topics and issues that resonate with their German Muslim identity, distinguishing them as a unique demographic simultaneously.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to contribute to the understanding of (anti-)radical content within the German Islamic TikTok community, specifically focusing on content creators who produce Islamic content or content pertaining to the Muslim identity. It employed a systematic categorization of (anti-)radical content and topics amongst this population. For that purpose, a qualitative coding of 2983 videos from 43 accounts was conducted to identify both the topics and the nature of the content (radical or anti-radical). Metadata such as likes, views, shares, and comments were also collected to contextualize the impact of these videos within the TikTok ecosystem. The findings were then presented by providing both quantitative and qualitative arguments, to answer the following questions: What types of radical and anti-radical content appear in videos by German Islamic TikTok creators, and what topics are commonly linked with these contents? How do these associations shape the narratives of these videos?

In summary, the representation of indicators commonly associated with radicalism and extremism in the literature is limited among the prominent German Islamic content creators in our sample (see Table A2). Narratives of victimhood are prevalent within the community, with “victimization” being a frequently coded indicator that leads to diverse political responses. Some creators leverage these narratives to facilitate discussions on their personal experiences and perceived injustices, advocating for equality, legal activism, and interfaith harmony. Conversely, others adopt more radical stances, profoundly questioning the legitimacy of the existing political order and partly endorsing divisive or revisionist ideologies. Issues surrounding victim narratives often involve significant societal concerns such as discrimination, the portrayal of Muslims in media, and double standards in Western societies. Exploring the specific videos highlights how content creators address these topics. They critique media representations and societal biases, with some advocating for activism and solidarity within the Muslim community as a means of addressing these issues. Others, however, argue that the existing political system is fundamentally illegitimate and propose the re-establishment of an Islamic Caliphate, but one shaped by their specific ideological vision, as the only viable alternative. Both forms of political advocacy are often portrayed as a necessary response to perceived injustices, with content creators using their platforms to challenge and possibly reshape the narrative around Muslim identity and belonging in Western contexts.

The discourse on the hijab within the German Islamic TikTok community illustrates its role as both a symbol of religious expression and a focal point for broader socio-political debates. The hijab is portrayed not just as a garment but as a symbol of identity and resistance, with statements elevating it to a symbol of pride and empowerment. These narratives challenge prevalent stereotypes and asserts the dignity of hijab-wearing Muslim women. Additionally, rationalizations for wearing the hijab are brought forward. They vary from practical benefits, argued not necessarily from a religious standpoint, such as protection and modesty, to deeper religious and cultural significance that align with religious and community identities. Such justifications often function as coping mechanisms to make the practice more bearable amid societal pressures and discrimination. For example, one creator presents the hijab as an act of liberation from societal beauty standards, suggesting a choice between conforming to divine will or societal expectations.

Moreover, the discussion extends into the practical challenges of wearing the hijab, such as workplace bans, underscoring ongoing discrimination and emphasizing the need for activism and community support. These complications surrounding hijab wearing highlight its complex role within society. This complexity is brought into the TikTok arena to foster exchange, raise awareness, and build solidarity on the matter. TikTok thus functions as a third space for many, serving as a platform where these critical issues are openly discussed and contested.

Religious advocacy (“advocacy”), with 1144 videos, emerges as the most dominant topic among German Islamic TikTok content creators, frequently intersecting with lifestyle topics. This reveals a community deeply engaged in linking doctrinal teachings to everyday practicalities, navigating the nuances of “permissibility” and the halal–haram dichotomy. Such content not only addresses religious edicts but also applies faith contextually to daily life, reflecting a community endeavoring to harmonize their religious beliefs with the complexities of living in today’s Germany.

Additionally, discussions extend into issues of religious interpretation, showcased by the presence of both “monism” and “anti-monism”, indicating a spectrum from rigid doctrinal adherence to more pluralistic approaches. Overall, the discourse on religious advocacy within TikTok serves as a reflection of broader religious life debates, illustrating how digital platforms have become central in guiding personal religious practice and addressing or reaffirming the ideological divides within the Muslim community. These discussions are crucial for understanding how religious content on TikTok helps navigate personal identity and community dynamics within a non-Muslim societal framework, fostering a sense of belonging and guidance for German Muslims.

By examining the topical distributions and the significant reach that some of these videos achieve, it becomes evident that Islamic content creators, much like other creators on TikTok, follow similar logics of marketability. This positions them within the broader TikTok culture, where lifestyle topics and performativity play a central role, even for creators of Islamic content, while still reflecting distinct aspects of their religious and cultural identities.

In summary, this study represents a novel approach adding to the limited literature on the Muslim ideological landscape on TikTok, specifically within Germany. It integrated the technical affordances of TikTok into its methodology, addressing the complexities of radicalism from a multidimensional perspective. This research is just one of many efforts needed to deepen our understanding of the role TikTok plays for marginalized groups, including Muslims, and how its technical and social workings may foster or mitigate radicalization.

On that note, we urge future research to explore this nexus further. Essential areas for further investigation include determining the prevalence of (anti-)radical material through large-scale studies to assess how wide-spread certain narratives actually are. Also, shifting the focus from the supply side (content creators) to the demand side (consumers) by assessing, possibly through experimental frameworks, the actual effects of TikTok consumption and its typical engagement patterns on religious and political radicalization is also crucial. Including the role and impact of anti-radical content to reliably measure how the usual consumption of both types of content ultimately influences the adoption of certain ideologies is important as well. Moreover, it is essential, contrary to the alarmism often associated with social media and political debates, to outline the positive, emancipatory, and empowering aspects of social media platforms like TikTok, especially for marginalized communities. Given the significance of gender in defining thematic demarcations and the role of the headscarf debate, further research should elaborate on gendered perspectives, which appear highly relevant in the online discourse of Muslims and broader society.

With the growing public and political attention on issues adjacent to radicalization, such as hate speech and violence online, developing research with nuanced and diverse analytical approaches is increasingly important. This includes a thorough understanding of the affordances and practices on specific social media platforms and adapting to the rapid pace of trends on these platforms to minimize the lag in obtaining evidence.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.H. and R.A.; Methodology, N.H. and R.A.; Software, N.H. and R.A.; Validation, N.H. and R.A.; Formal analysis, N.H. and R.A.; Investigation, N.H. and R.A.; Resources, N.H. and R.A.; Data curation, N.H. and R.A.; Writing—original draft, N.H. and R.A.; Writing—review & editing, N.H. and R.A.; Visualization, N.H. and R.A.; Supervision, N.H. and R.A.; Project administration, N.H. and R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Ministry for Education and Research (Project ID 01UG2035, “German Islam”). The article processing charge was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—491192747 and the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. This work was supported by the University of Mannheim’s Graduate School of Economic and Social Sciences and received additional funding through its Young Scholar Award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable, as the data were sourced exclusively from public TikTok accounts and were pseudonymized.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sampled accounts and account data.

Table A1.

Sampled accounts and account data.

| Pseudonym | Prior Research * | Account Status ** | Gender | Videos | First Video | Last Video |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT1 | Identified | Not Available | male | 123 | 01.01.2022 | 28.12.2022 |

| PT2 | Not Identified | Available | female | 72 | 02.01.2022 | 23.12.2022 |

| PT3 | Not Identified | Available | male | 70 | 02.01.2022 | 29.12.2022 |

| PT4 | Not Identified | Available | male | 83 | 02.01.2022 | 27.12.2022 |

| PT5 | Not Identified | Available | male | 18 | 01.01.2022 | 07.06.2022 |

| PT6 | Identified | Available | male | 73 | 17.08.2022 | 30.12.2022 |

| PT7 | Not Identified | Not Available | female | 21 | 22.12.2022 | 31.12.2022 |

| PT8 | Not Identified | Available | male | 69 | 02.01.2022 | 31.12.2022 |

| PT9 | Identified | Available | male | 72 | 17.01.2022 | 28.12.2022 |

| PT10 | Not Identified | Available | male | 10 | 03.04.2022 | 04.11.2022 |

| PT11 | Identified | Not Available | male | 18 | 29.04.2022 | 12.12.2022 |

| PT12 | Identified | Available | male | 71 | 25.01.2022 | 26.12.2022 |

| PT13 | Not Identified | New Account | male | 68 | 12.01.2022 | 25.12.2022 |

| PT14 | Not Identified | Renamed | male | 65 | 01.01.2022 | 26.12.2022 |

| PT15 | Not Identified | Available | couple | 72 | 07.05.2022 | 27.12.2022 |

| PT16 | Not Identified | Available | female | 148 | 01.01.2022 | 31.12.2022 |

| PT17 | Not Identified | Not Available | female | 105 | 10.06.2022 | 30.12.2022 |

| PT18 | Identified | Available | male | 63 | 01.01.2022 | 13.07.2022 |

| PT19 | Not Identified | Not Available | female | 10 | 22.01.2022 | 13.10.2022 |

| PT20 | Not Identified | Available | male | 21 | 02.01.2022 | 28.12.2022 |

| PT21 | Identified | Available | male | 72 | 27.08.2022 | 07.12.2022 |

| PT22 | Not Identified | Available | male | 80 | 05.07.2022 | 24.12.2022 |

| PT23 | Not Identified | Not Available | male | 66 | 01.03.2022 | 27.12.2022 |

| PT24 | Not Identified | Renamed | unknown | 25 | 08.09.2022 | 18.12.2022 |

| PT25 | Not Identified | Available | male | 91 | 03.01.2022 | 19.11.2022 |