4. Transcendent Feelings

Positive cognitive feelings also arise, in the context of everyday life, that underlie positive human emotions. These include feelings of pride, freedom, togetherness, belonging, vitality, pride, success, winning, closeness (in social relations), contentment, love, solidarity, and unity. These positive feelings are associated with positive language, such as that of virtues, for example, security, respect, empathy, and empowerment. When these positive feelings arise against the background of negative feelings, they take on a transcendent character of rising above the pain and suffering in the world. It is here that we can speak of spirituality in the context of LBTC (

Alexander et al. 2021;

Van Cappellen et al. 2013).

Consider the case of a person who has been beaten down by a streak of misfortune. Due to economic forces beyond their control, they have lost their job, which created familial stress leading to the dissolution of his marriage. Sitting in solitude, such a person may feel good reason to see the world as a horrible place, thus damning the universe. The person may contemplate ending it all as an escape from the situation; they catapult into the worst thing that could conceivably have happened to them. There is, they think, little left to live for. They are alone, dissolute, and aimless in life. But they have saved enough money to live modestly without being cast out into the streets. The person thinks a moment about this small fact. Then, they recall seeing a homeless person drenched in excrement on the streets, coughing up blood from what is likely the tuberculosis that will end his suffering. They think about themselves in relation to this man. They then think about how much more sensitive they have now become to this poor man’s suffering, whereas before they were simply repulsed by the very thought of this man, whom they had formerly considered vermin and scum. Then, they realize how their powers of empathy and understanding have expanded because of their own suffering. They begin to think about how fortunate they have been, to have lived productively and of the good times they have had in their life. Suddenly, they feel lifted above the present vicissitudes of life and, feeling revitalized, decide to become a social worker with the goal of helping those who are oppressed, impoverished, and cast out of society like filth and garbage. This person is excited by these new revelations and begins to plan for their new career.

Friedrich

Nietzsche (

1954) remarked that suffering ennobles, and it is such a philosophical perspective that has brought this man new meanings in life. It is this feeling of transcendence over the suffering of the vicissitudes of life that has the flavor of a spiritual experience. The feeling is a product of philosophy that resonates with the person, which adds renewed hope and vitality to what was previously perceived through bleak cognitive lenses. Without the darkness, the light would not have been so illuminating and radiant. Indeed, it would not have even been possible. Such transcendence goes to the heart of our most profound spiritual experiences, and it can be exhilarating.

When the resonant philosophy is God-centered, transcendence beyond the mundane suffering of earthly existence takes on a religious character. The Neoplatonist, Plotinus, talked about an ecstatic unity with God achieved through a process of purification of the soul. According to Plotinus, one who beholds God is “overwhelmed with love; with ardor desiring to unite himself with Him, entranced with ecstasy” (

Plotinus 1918, Ennead 1, Book 6). However, not just anyone can gain this experience. One must first rid the soul of bodily cravings and desires (for example, sexual desires) which, in Augustine’s terms, “weigh down the mind,” distracting it from the truly blissful goal of attaining unity with God. The latter is, instead, attained through cultivating the virtues of wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance.

However, one does not need to accept Plotinus’ religious philosophical perspective to accept his profoundly important point about the connection between working on becoming virtuous and the experience that transcends one’s irrational tendencies. In LBTC, the experience of such transcendence is an indication that one has found an uplifting philosophical perspective that can, with hard (cognitive–behavioral) work, lead to the cultivation of virtue. However, one need not already be virtuous to see the light of virtue, and thus resolve to become such. Indeed, it can be the transcendent experience itself that motivates one to become virtuous in the first place. Thus, the man in the previous example, still has miles to go before the journey toward virtue is on firm soil, but it is in the journey that virtue manifests itself and grows stronger. In what follows, I will describe the six-step LBTC process that supports such transcendent experience in the attainment of virtue.

5. Attaining Transcendent Experience: The Six-Step Process

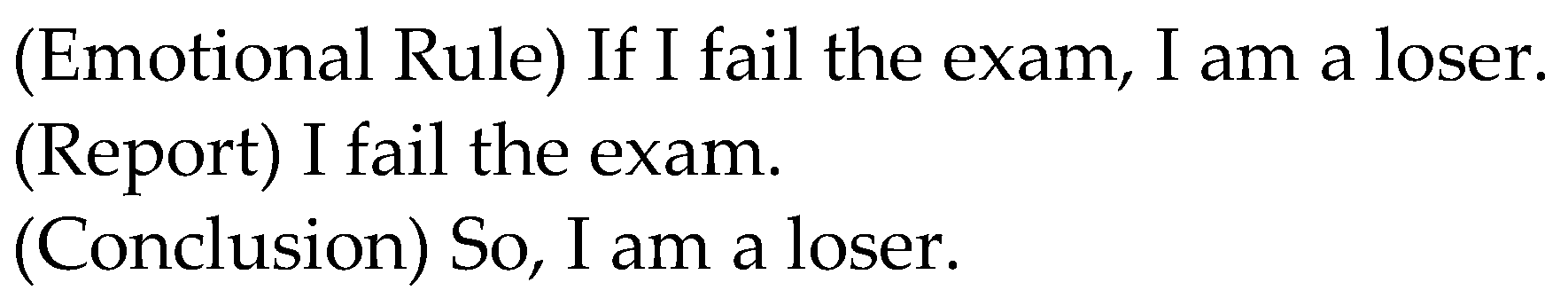

Step 1 in LBTC is to help the client formulate their emotional reasoning, such as in the above example about failing an exam. This is achieved by keying into the client’s intentional object (what the client’s emotion is

about) and their rating of it (how bad it is on a scale of 1–10) (

Cohen 2016). In the previous example, the intentional object is the possibility of the client’s failing the exam, and its rating is that of the client themself being a “loser,” a 9 or 10, let’s say, on the rating scale (where the higher the number, the more negative the rating is). Once these elements are identified, they can be substituted for O and R (object and rating, respectively) in the below modus ponens form to get the primary emotional reasoning exhibited in

Figure 1.

(Emotional Rule) If O then R

(Report) O

(Conclusion) So, R

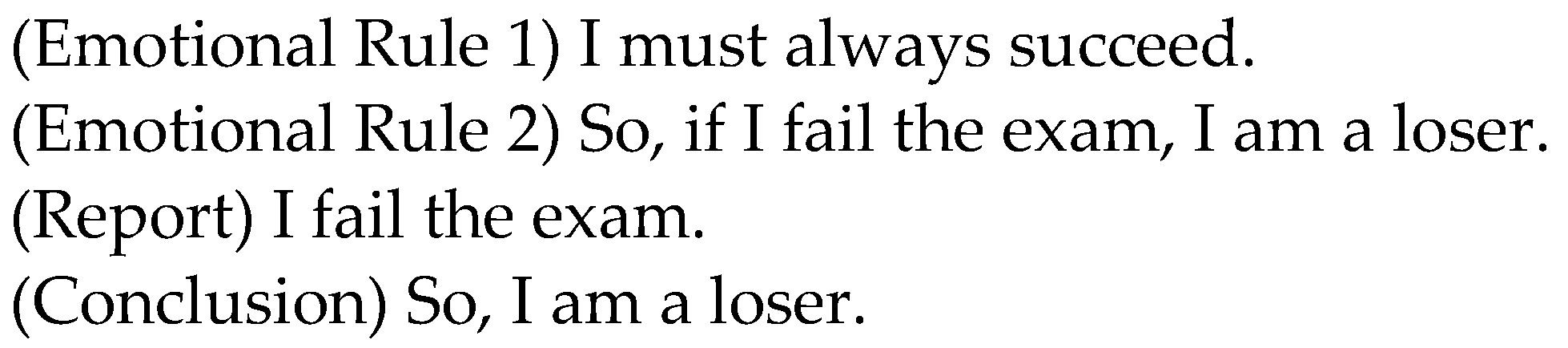

The therapist can then probe for the basis of the Emotional Rule, as identified in

Figure 2.

Step 2, then, involves identifying the fallacies in the premises. LBTC provides a list of key fallacies it calls “cardinal fallacies.” They are “cardinal” because they tend to be at the root of all or the most serious behavioral and emotional problems. There are eleven categories of these fallacies as follows: demanding perfection, catastrophizing, jumping on the bandwagon, the-world-revolves-around-me thinking, damnation (of the self, others, or the world), can’t-stipation (emotional, behavioral, and volitional), dutiful worrying, manipulation, oversimplifying reality, distorting probabilities, and blind conjecture (

Cohen 2016). In the present example, the client deduces self-damnation (“I am a loser”) from demanding perfection (“I must always succeed”).

Step 3 is to refute the fallacious premises by showing that they are irrational (

Cohen 2003). For example, the client may be asked to identify something they have not succeeded at in the past. Then, the client may be challenged to explain how, if succeeding were truly necessary (an ontological “must”), how they, like other imperfect human beings, have sometimes not succeeded.

Step 4 proceeds by identifying a “guiding virtue” for each of the fallacies identified, which counteracts or overcomes the fallacy. Each of the eleven cardinal fallacies has at least one such guiding virtue (

Cohen 2016). For example, a guiding virtue of demanding perfection is metaphysical security. The latter virtue is that of feeling secure in an imperfect world. It is the most general of all the virtues, that of feeling secure about reality itself. Inasmuch as there are different types of imperfections in reality, for example, the inability to control everything, the lack of certainty about the future, the inability to know all, and human fallibility, metaphysical security includes all the other virtues. Thus, the courageous person is secure about taking (reasonable) risks, and the self-respecting person is secure about their own human imperfections or flaws.

Step 5 is for the client to identify and adopt at least one philosophical perspective that interprets at least one of their guiding virtues. A key characteristic of guiding virtues is that they can be viewed through the lenses of diverse philosophical perspectives (

Cohen 2007). Consider courage, which, Aristotle says, is the rational control of fear lying in the middle between excess and deficiency, that of rashness, on the one hand, and cowardice, on the other (

Aristotle 1941). Notice that this definition does not, itself, prescribe what a person should be afraid of, just that the fear needs to avoid the extremes. Similarly, one can express authenticity in many ways according to many different lifestyles and values; one can respect oneself according to different standards of respectability, and one can be prudent (make rational practical decisions) in pursuit of diverse life goals.

Being virtuous does not tell you what to be afraid of, what lifestyles and values to embrace, what is respectable, and what one’s life goals should be. Such things are, instead, the province of one’s

philosophical perspectives. Thus, for the deeply religious person, courage may be manifested in devotion to God without permitting fear of material loss to distract oneself. This is, according to Kierkegaard, the courage that Abraham showed in his willingness to sacrifice Issac out of devotion to God. It is, as he says, “the courage of faith” (

Kierkegaard 1941, problemata).

On the other hand, for the secular yet spiritual person, courage may be manifested in amassing power over the challenges of everyday life. According to Friedrich

Nietzsche (

1954), the courageous person applies “his inventive faculty and dissembling power [spirit] … to develop into subtlety and daring under long oppression and compulsion, and his Will to Life … increased to the unconditioned Will to Power” (p. 429). Likewise, authenticity for the religious person may be freely cultivating and expressing one’s love of God, while, for the secular person, authenticity may lie in cultivating one’s individuality by freely engaging in “experiments of living” (

Mill 2011, chp. 3).

Or consider the virtue of self-respect. A philosophical view of oneself as a child of God, in St. Thomas’ words, “an imprint of the Divine light” (

Aquinas 2006,

Treatise on Law, quest. 91), may work as an interpretation of what it means to have self-respect for a religious person. On the other hand, Kant’s idea of a person as an “end in itself,” that is, as a being whose value is intrinsic and does not depend on whether it is useful for this or that purpose, may be a secular way to arrive at a viable interpretation of the meaning of self-respect (

Kant 1964, p. 95).

Kant (

1964) speaks, in this regard, of all human beings as members of a “kingdom [community] of ends,” not as mere conduits (p. 100).

LBTC, therefore, does not tell clients what philosophies to embrace in the pursuit of their guiding virtues. If it did, clients would mechanically go through the motions of trying to overcome their irrational thinking through development of their virtues. Such force feeding of philosophy is more likely to destroy authenticity, self-respect, and other virtues than to promote them. It is also likely, therewith, to destroy the prospects for attaining the transcendent spiritual experiences that are the hallmark of philosophical resonance.

In my clinical experience, such transcendent experiences have repeatedly been attained when interoceptive imagery is used by the client to determine if a potential philosophical antidote truly resonates with the client. First, I use interoceptive imagery to help the client experience the underlying feelings that are expressed by the major premise rules (for example, an ontological feeling of necessity) and the deduced conclusion (for example, a feeling of self-loathing) (

Cohen 2021a). Consider the earlier example of the client who experiences anxiety over the possibility of failing an exam:

Therapist: “Okay, so what I want you to do is to imagine yourself taking the exam and get yourself to feel like you are failing it. When you are there, let me know. (Momentary pause)

Client: I’m there.

Therapist: Tell me what you are experiencing.

Client: Very depressed.

Therapist: When you focus on your failing the test, does this feel like something that you would prefer not happen, or is it something stronger than a preference, maybe like something that just can’t happen?

Client: It feels stronger than a preference.

Therapist: Like “Oh no how can this really be happening!”

Client: Yes, exactly.

Therapist: You feel a need that it not happen?

Client: Yes, that’s right.

Therapist: But it is happening.

Client: Yes.

Therapist: So, it is happening, but it can’t happen?

Client: Yes!

Therapist: So, you feel this contradiction, that what can’t be happening is happening?

Client: Yes, I feel this way, and I feel really bad about myself.

Therapist: Like you are doing what you must not be doing?

Client: Yes, like such a loser!

Once the client is at this stage, the next step is to check to see if the philosophy the client has adopted truly resonates:

Therapist: I want you now to shift your focus to the philosophy we discussed earlier, that of Kant’s idea that you are a person and not some object whose worth and dignity depends on your use for this or that purpose, or how well you perform. Let yourself get absorbed in this philosophy and let yourself feel it. Let me know when you are there. (Momentary pause)

Client: I am there.

Therapist: What are you feeling?

Client: I feel this sense of relief. I feel like a heavy weight has been lifted from my shoulders.

Therapist: Tell me more about this feeling.

Client: I feel free.

Therapist: Free from what?

Client: From being hurt by this exam, even if I fail it.

Therapist: Your worth still would remain intact?

Client: Yes, because I am still a member of this community of human beings who have this worth, no matter what.

Therapist: Like you are beyond being negatively affected by this world of ups and downs that come and go?

Client: Yes, exactly. I feel free from this.

Here, the client resonates with the philosophy of Kant and has the experience of “relief” from a “heavy weight”, “free” from the contingent universe of transitory space–time events. The client’s worth and dignity remains intact as a member of a “community of ends.” Hence, this experience is transcendent: the client is lifted above the everyday earthly concerns, such as whether he will fail the exam. This is not, as such, a religious experience in the sense that it involves a communion of sorts with God. But there is, nevertheless, a sense of otherworldliness in that it transcends the usual feelings arising from the contingencies of earthy existence.

Such transcendency is empowering. It lifts the spirits and there is a renewed sense that one can confront the vicissitudes of life with new vitality. It is remarkable how abstract philosophical ideas, such as that of Kant’s “Categorical Imperative”, can have this empowering effect on a person’s outlook on life.

However, not all clients will resonate with Kant. I have, in fact, seen two cases in which clients who were philosophers being trained in LBTC, who considered themselves to be devote Kantians, discovered, through an LBTC session with me, that their acceptance of Kant’s philosophy was what was creating their, respective, presenting problems. In one case, the client suffered from chronic guilt because he

demanded that he always treat others as ends in themselves and that, therefore, he was a bad person when he failed to do so. In this case, the client discovered that an existential approach, such as Jean-Paul Sartre’s idea that “Existence precedes essence” (

Sartre 2007, pp. 20–21), liberated him from the essentialism of Kant’s philosophy. So, the client entered the philosophical counseling room as a frustrated, guilt-ridden Kantian and left as a (potentially) liberated existentialist!

Further, some clients resonate with lyrics of songs, movie themes, or literature that contain uplifting, abstract ideas (

Hsu 2015). Indeed, not all clients are partial to the intricacies of a complex philosophical idea, but most clients can resonate with the profundity found in lyrics and the rhythms and harmonies that accompany them, or with a plot that drives home an important way to cope with reality. Philosophical ideas that lead to transcendent experiences are, therefore, not the exclusive domain of the philosopher or those who are especially philosophically inclined. While no philosophical modality can claim to be accessible to everyone, LBTC is quite versatile in the way it can make philosophy palatable for many diverse populations of clients.

Philosophical resonance is, hence, individualistic and appears, superficially, to be subjective. There is no intersubjectivity where clients ultimately are guided to accept the one true philosophy. From a religious perspective, this is significant. Is there one unifying, extra-subjective reality that is revealed through the transcendent experiences generated by diverse philosophies during the interoceptive imagery of the LBTC process?

My experience as a clinician suggests that, while there is no one philosophical frame that provides the door to such uplifting, empowering, transcendent experiences, there is a common theme of freedom and relief from the mundane problems of earthly existence. Is this the individual’s way of experiencing God? Is it the analog of Plotinus’ ecstatic experience, only widened to include the experiences of nonbelievers as well as believers? This is not a question I can answer through my clinical experience. Still, I marvel at the similarities of the experience arrived at through sundry and distinct philosophies. Whether it is Buddhism, Kantianism, Existentialism, Stoicism, or other philosophical frameworks with which the client resonates, there is this constant sense of escape, relief, freedom, or lightness that characterizes the experience.

Herein lies the core of metaphysical security, that of feeling secure about reality itself. It is this generic feeling that goes to the heart of spirituality. Through the spiritual experience, one looks down upon the imperfections and gaps in being, and from this transcendent vista, says yes to them. One sees that things are as they are, imperfect and immeasurably incomplete or lacking in some potentially desirable aspect, but still feels a deep sense of security about this lack of being. It may be the fact that one cannot always succeed; that there are things beyond human control; that human reality is flawed; that the future is not fully in our grasp; that, as the future passes into the past, it cannot be undone; that the world includes pain and suffering; that there are indelible gaps in human knowledge.

It is the resonating philosophical perspective, through which one perceives these imperfections and gaps in being, that brings peace of mind. The Buddhist teaches that material reality is transitory, so clinging to it brings great suffering, and letting go brings serenity. The Stoic teaches that there are things beyond one’s control, namely the thoughts, acts, and feelings of other people, as well as external events, so trying to control them leaves one destitute of happiness. The Hindu teaches that by observing sense perceptions without reacting to them, one can gain the state of an illuminated mind, free from suffering. The atheistic existentialist teaches that we have the freedom to choose and are not saddled by some sort of cosmic necessity, so imperfections can be reconceived as opportunities. The Kantian teaches that we are, in the end, all human beings with the same intrinsic, inalienable worth and dignity, thus creating a sense of unity with other human beings, who may not necessarily share our own values or perspectives. The Platonist teaches that there are ideals in a heaven of ideals, but that it is futile to demand the same perfection in the world perceived through our senses. Within these, among other generic philosophical camps, are diverse variations and combinations of uplifting ideas that can infuse the experience of imperfection with creative, new meanings, and values. This energizes and motivates the individual to view life on earth with renewed, revitalized enthusiasm and, thereby, to make constructive changes in the way one lives.

Step 6, the final step in the LBTC process, accordingly, involves applying the uplifting philosophy by developing a plan of action. This is where the philosophy is operationalized as a set of behaviors. For example, the Kantian philosophy says to treat oneself and others as ends in themselves. This entails not referring to oneself (as well as others) as a “loser” or other degrading terms. Within such parameters of self-respect, the plan of action is open to interpretation by the client. Perhaps the client has shied away from engaging in risk-taking activities because he was afraid of failing. As such, this might include a set of behavioral assignments that involve building greater self-confidence and respect. In this way, guided by the transcendent experience as a model, the client seeks to become freer and less encumbered in dealing with the practical vicissitudes of life.

This is not unlike the Platonic construct in which the Form of the Good provides the model of individual things that participate in it. The transcendent philosophical experience of freedom and relief becomes the guiding light in which the individual actions in the client’s behavioral plan “participate.” Thus, like a religious experience of communion with God, the transcendent philosophical experience sets the standard of mundane living, except that the experience need not be explicitly related to such a religious experience, but may similarly lift and guide the spirit of secular recipients.

Among religious and nonreligious spirituality, there is a common denominator. It is the philosophical infusion of the mind with the power to make constructive change. For the religious person, this means doing God’s work, such as spreading love and kindness, thus preparing for the hereafter, or getting closer to God here on earth. To the secular person, it means focusing on making life on Earth better, such as getting along better with others, trying out new experiments in living, or finding a partner. The agnostic leaves it open whether this has any divine payoff, while the atheist perceives the here and now on Earth to be the final destination. In any event, the result is the cultivation of virtues, such as courage, empathy, authenticity, prudence, and self-control, among other guiding virtues.

The idea of the power of philosophy to lift the soul from the suffering of everyday life has ancient roots and is not simply the hypothesis of LBTC. Indeed, in his

Consolation of Philosophy,

Boethius (

2009) gives voice to philosophy, which then speaks to its followers:

Thus has it followed that you, like others, have fallen somewhat away from your calm peace of mind. But it is time now for you to make trial of some gentle and pleasant draught, which by reaching your inmost parts shall prepare the way for yet stronger healing draughts. Try therefore the assuring influence of gentle argument which keeps its straight path only when it holds fast to my instructions.

(bk. 2, prose 1)

It is such “gentle argument” of philosophy that builds consoling syllogistics, counteracting irrational emotional reasoning and calming the mind.

6. Conclusions

Logic-Based Therapy and Consultation can, in this manner, be a highly spiritual form of philosophical counseling. It focuses on building metaphysical security, the core of spirituality, by employing an abundance of philosophical perspectives to resonate with individuals from diverse social and/or religious backgrounds and perspectives. It utilizes such resonance in the systematic production of transcendent, uplifting experiences that revitalize the human spirit, infusing it with new meanings in place of stagnant and self-defeating cardinal fallacies. Accordingly, it builds guiding virtues that lead to constructive change, cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally.

Spirituality is, therefore, not something that arises willy nilly. Rather, it is a product of heightened perception, arising from working to overcome the irrational thinking that blocks the road to transcendence. It is the fruit of this labor, with philosophical roots that are anchored to human flourishing.

Spirituality also arises in the context of irrational feelings, much as darkness provides the context through which the radiance of the good stands out. Indeed, without suffering, the value of relief from pain would be null. From an Eastern perspective,

Lao-Tzu (

1988) remarked, “True perfection seems imperfect, yet it is perfectly itself…” (p. 45), thus calling attention to the idea that there is no reason without unreason, no “true perfection” without the imperfections of irrationality that rationality seeks to correct. Hence, the transcendental experience of LBTC does not assume the perfect conquest of irrationality as its precondition.

Further, it would be misleading to say that the feelings arising in the context of the transcendent experience are rational or irrational. Feelings are nonrational, that is, neither rational nor irrational. The latter constructs apply to thinking or reasoning. Feelings may arise because of irrational or rational thinking, but, phenomenologically, the feeling itself is neither. Hence, while the philosophical reframing that helps to generate the spiritual experience can appropriately be called rational, this is not the case with respect to the feeling so arising. If it is claimed that spiritual experiences have an irrational dimension, it may also be that there is no rational explanation at least for them for some (one cannot explain their genesis, for example), but the feeling itself is not irrational, for that would be a category error, that is, trying to apply a concept to something to which it simply does not apply.

I do not profess that this transcendent experience has foundations beyond the stimulation of neurons in the complex neural interactions between somatosensory, limbic, and neocortical regions of the brain. Still, as a philosophical practitioner, I have been awed by the commonality of the experience of a sense of lightness and release from suffering that is invariably reported by clients who report their experience during imagery sessions. In this respect, it has an intersubjective flavor attained through variable subjective states. There are many different philosophical routes to arrive at this end, however the destination is invariably the same.