Abstract

In medieval bestiaries, knowledge about animals and their behavior is regularly given a Christian moral interpretation. This article explores the use of imagery related to the bestiary tradition in three Hebrew books made around the year 1300, focusing especially on the richly decorated Rothschild Pentateuch (Los Angeles, Getty Museum MS 116). These Hebrew books signal how bestiary knowledge and its visual expression could be adapted to enrich the experience of medieval Jewish reader-viewers, adding to our understanding of Jewish-Christian interactions in medieval Europe.

1. Introduction

On the fifteenth day of the month of Tammuz, in the year five thousand and fifty-six (17 June 1296), the scribe Elijah (https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/109P73), the son of Meshulam, completed a copy of the pentateuch for the patron Joseph Martel, son of Joseph. In this, he was assisted by another Elijah, the son of Yehiel, who provided the vocalization for the text as well as the masorah. (The masorah comprises authoritative comments about the exact form of the biblical text, often with quotations of biblical verses where a particular linguistic form occurred. The longer masorah magna was usually written in miniature script in the upper and lower margins of the page, while the shorter masorah parva was inserted in the outer vertical margins or between text columns (Martin-Contreras 2013; Petzold and Liss 2019)). One of these Elijahs, or more likely a third member of the production team, served as the artist, providing rich decoration on each of the pages marking the beginning of the weekly Sabbath Torah portion, the accompanying reading from the prophets (the haftarah), and the five ‘scrolls’ recited on festivals (megillot = Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). The pentateuch section with the haftarot was owned by Baroness Adelaide de Rothschild, who donated it to Frankfurt’s Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek sometime before 1920 (Swarzenski and Schilling 1929); it is now MS 116 (https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/109NVP) in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The megillot section, which in 1905 was in the possession of the antiquarian bookdealer Karl Hiersemann in Leipzig, belongs to the Luther Memorials Foundation in Saxony-Anhalt (Wittenberg, Ms. 2598). Structurally, the original manuscript corresponds to what David Stern has called a “liturgical” Bible; it also includes the Aramaic translation of the biblical text and the commentary of Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, 1040–1105) in separate columns (Stern 2012; 2017, esp. 63–135).

With approximately 155 pages decorated with gold, silver, and colored pigments, Joseph Martel’s copy is the most extensively decorated extant medieval Hebrew Bible. It has only begun to be studied by scholars, and many aspects, including the identity of the patron and scribes and the place of the book’s production, remain to be addressed and resolved. The Rothschild Pentateuch was certainly made in medieval Ashkenaz (western and central Europe), not Sefarad (the Iberian peninsula and southern France; Sed-Rajna 1994; Kogman-Appel 2004). My preliminary investigations point to stylistic and iconographic connections with the so-called Bar manuscripts—a group of luxuriously decorated service books made for various members of the comital house of Bar in the upper Lorraine; some of which can be connected to Metz and the Lorraine—but this requires further study (Davenport 2017; Stones 2013–2014, part II, v. 1, 32–40, 78–88, 91–98; 2014). In this essay, I take my cue from the appearance of the pentateuch in the Getty Museum’s 2019 exhibition and publication, Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World (Morrison and Grollemond 2019; Eisenberg and Holcomb 2019; Mintz and Morrison 2019). Focusing on those images connected to the bestiary tradition, I explore how they are used in the Rothschild Pentateuch itself and consider similar representations in two contemporaneous Hebrew manuscripts. Doing so offers another perspective on the broad question of the complex relationship between medieval Jewish and Christian culture, which has been described in such terms as “borrowing”, “mimicry”, “inward acculturation”, “entanglement”, and “appropriation”. (For two important contributions, with reviews of the issues and relevant literature, see Baumgarten 2018 and the introduction to Entangled Histories 2017.)

The decorated pages of the Rothschild Pentateuch are filled with a menagerie of real and imaginary animals, hybrids of all sorts, heraldic devices, and architectural frames, all executed in what might be called a “marginal mode” (Sandler 2008; Wirth 2008). Six pages can be connected definitively to representations in the bestiary tradition, and although these represent a small percentage of the book’s images, they point to interpretative strategies for the rest of the volume and have important implications for the consideration of Jewish-Christian relations. I will treat them in the order they appear in the book, and, for the sake of simplicity, I attribute the pictorial decisions to the artist, keeping in mind that we do not know the mechanics of production or the role of the patron or of a theological advisor in shaping the visual content (discussed below).

2. The Lion

The first case is on fol. 32v, marking the opening of the weekly portion of Vayera (corresponding to Gen 18–22) (Figure 1). Enlarged words are written in gold to head each of the three columns (as is fairly standard throughout the book): the closing formula for the previous portion above the right column, which contains Rashi’s commentary, the first word of the biblical text suitably in the center, and the Aramaic translation in the left column. The large rectangular panel in which these golden words appear is dominated by the depiction of a large lion standing over a small, prone one. The image is instantly recognizable as a lion of the sort that begins all standard versions of the medieval bestiary. In those (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast78.htm), the text explains how lion cubs are born dead but, after three days, are revived by the breath or the lick of the lion parent(s). This was just one point developed as part of the Christian allegorization of the lion as Christ and at first glance the creature’s appearance in the Hebrew Bible seems surprising. Indeed, there is nothing in chapters 18 through 22 of Genesis that speaks of lions, but Mintz and Morrison (2019) suggested that a connection could be discerned in the episode of the Binding/Sacrifice of Isaac recounted in chapter 22. This scene was frequently depicted in medieval Hebrew manuscripts, sometimes with subtle alterations to distinguish it from contemporaneous Christian iconography (Gutmann 1987; Shalev-Eyni 2020), but some configuration of Abraham, Isaac, the angel, and the ram was fairly consistent. By turning to the bestiary tradition, however, the artist of the Rothschild Pentateuch seems to be giving expression to a midrashic (homiletic) reading of Genesis 22, in which Abraham actually completed the sacrifice and Isaac spent three years in Paradise (Ginzberg 1947, vol. 1, 231–33; see, in general, Neusner and Peck 2005). The midrashic reading is based on certain textual nuances and amplifies a strong rabbinic interpretive tradition that emphasized both Abraham’s and Isaac’s willingness to complete the sacrifice; it might well be contextualized in light of crusader massacres and Jewish-Christian polemics (Spiegel 1967; Schoenfeld 2013). The Genesis narrative, of course, continues with a living Isaac, and so the midrash must resurrect him after the purported sacrifice, although it does not go into any real explanation of this process. A different midrash glosses verse 22:4, which says that Abraham saw the mountain on “the third day,” with various biblical verses equating three days with life and deliverance (Freedman and Simon 1936, vol. 1, p. 491). In light of these midrashic sources, the bestiary text about a lion reviving his cub after three days would be an apt way to convey a homiletic reading of the sacrifice—and resurrection—of Isaac.

Figure 1.

Los Angeles, Getty Museum, MS 116, fol. 32v: Vayera [Genesis 18:1–22:24]. (Acquired with the generous support of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; reproduction courtesy of The Getty Museum under Creative Commons CCO 1.0 Universal).

Nowhere in the midrash, however, is it suggested that it was Abraham who revived Isaac, and so there may well be a second layer behind the use of this image in the Rothschild Pentateuch. The artist has taken pains not only to restrict his picture to the father and a single cub (as appropriate generally to the Abraham and Isaac analogy) but also to show the cub flat on its back, the two paw-to-paw, and with the father prominently putting his tongue in the cub’s mouth. Among bestiary images of the lion (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beastgallery78.htm), this is rather uncommon; most do not even depict the revival of the cubs, and of those that do, many show the mother, father, or both breathing on one or more cubs (Heck and Cordonnier 2012, which is notable for including material from Hebrew manuscripts in its overview of the subject). One close, but not exact comparison, can be found in an English bestiary from the second quarter of the thirteenth century (Oxford, Bodleian MS Bodl. 764, fol. 2v (https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/e6ad6426-6ff5-4c33-a078-ca518b36ca49/surfaces/5fd6efe8-e1bc-4477-8684-200bc11cbd6b/)), which is affiliated with the so-called Second Family of bestiaries (Clark 2006, esp. 119–22 for the lion; De Hamel 2008; a digital version (https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/e6ad6426-6ff5-4c33-a078-ca518b36ca49/) of the manuscript is available on the Bodleian website). Whatever the particular visual source, the details of this striking image are not clearly motivated by the interaction between Abraham and Isaac. Rather, they call to mind the episode of the prophet Elisha reviving the Shunammite woman’s son, who had fallen dead (2 Kings 4). Reading the climactic verses 31–35 while looking at the Rothschild Pentateuch image demonstrates how vividly the picture suggests the prophet’s actions in reviving the boy:

Gehazi had gone on before them and had placed the staff on the boy’s face, but there was no sound or response. He turned back to meet him and told him, “The boy has not awakened”. Elisha came into the house, and there was the boy, laid out dead on his couch. He went in, shut the door behind the two of them, and prayed to the LORD. Then, he mounted [the bed] and placed himself over the child. He put his mouth on its mouth, his eyes on its eyes, and his hands on its hands, as he bent over it. And the body of the child became warm. He stepped down, walked once up and down the room, then mounted and bent over him. Thereupon, the boy sneezed seven times, and the boy opened his eyes.

In Jewish liturgical tradition, 2 Kings 4 was selected as the weekly prophetic reading appropriate for the Torah portion of Vayera, thematically emphasizing the deliverance of a son in both cases. Admittedly, the version of the haftarah provided at the back of the Rothschild Pentateuch (fols. 501v–502v) comprises only the first half, verses 1–26, cutting off just before the resurrection episode in a kind of cliffhanger, but it is hard to imagine that reading this half would not call to mind the dramatic conclusion of the story. Appearing as it does at the opening of Vayera, which begins with Genesis 18, the image of the lion and its cub is not a direct illustration of the text on the page. Rather, it is meant to stimulate in the reader-viewer a chain of associations that involves knowledge about the nature of lions and their suitability as a metaphor for the deliverance of Isaac in Genesis 22 (refracted through the midrash) and the Shunammite’s son (prompted by the liturgical context).

3. The Unicorn

The second image in the Rothschild Pentateuch certainly connected to the bestiary tradition comes in the weekly reading for the portion of Misphatim (Ex 18–22) (Figure 2). Like the other opening pages, fol. 169r contains the enlarged keywords in gold at the top of each column, amalgamated here in a roughly rectangular painted panel. The upper edge serves as the ground line for a knight, a horned animal, a woman sitting in a tree, and a little dog behind her. In its broad contours, the group corresponds to the common depiction of the unicorn (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast140.htm). In medieval lore, the unicorn could only be tamed and then captured with the help of a virgin, and in the bestiary text, this was allegorized as Christ, made incarnate in Mary, and then captured by the Jews (Williamson 1986; Clark 2006). Representations in the bestiary could vary; some showed the unicorn more or less closely connected to the virgin—who may or may not be near a tree—and attacked more or less violently by a hunter. Versions of the unicorn were also used liberally in books other than the bestiary, as in the Breviary of Renaud de Bar (Verdun, 1302–3; BL, Yates Thompson MS 8, fol. 260r) or the Ormesby Psalter (E. Anglia, ca. 1315; Oxford, Bodleian MS Douce 366, fol. 55v (https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/34a6037b-12e8-4b12-8920-26c33914fe0e/surfaces/b6280014-d5c6-4721-8626-2f82c1858a90/)). The Rothschild Pentateuch scene looks roughly like other unicorn groupings but not exactly like any one of them. The biggest divergence is in the representation of the unicorn, which, upon closer inspection, seems like a poor specimen of this fierce, swift creature. The depicted animal, in fact, is not a unicorn. It is a horned ox, which is the first clue to understanding the suitability of this imagery in the pentateuch. The portion of Mishpatim is filled with legal regulations, especially in torts. Exodus 21:28–32 lays down the law regarding the “goring ox” (a subject that would later provide extensive fodder for the rabbis in Talmud tractate Bava Kama; Finkelstein 1981):

Figure 2.

Los Angeles, Getty Museum, MS 116, fol. 169r: Mishpatim [Exodus 21–24]. (Acquired with the generous support of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; reproduction courtesy of The Getty Museum under Creative Commons CCO 1.0 Universal).

When an ox gores a man or a woman to death, the ox shall be stoned and its flesh shall not be eaten, but the owner of the ox is not to be punished. If, however, that ox has been in the habit of goring and its owner, though warned, has failed to guard it, and it kills a man or a woman—the ox shall be stoned and its owner, too, shall be put to death. If ransom is imposed, the owner must pay whatever is imposed to redeem the owner’s own life. So, too, if it gores a minor, male or female, [its owner] shall be dealt with according to the same rule. But if the ox gores a slave, male or female, [its owner] shall pay thirty shekels of silver to the master, and the ox shall be stoned.

There is a similar textual grounding for the virgin, laws about whom are given in the very next chapter, Exodus 22:15–16:

This alone would be enough to account for the appearance of a virgin, but the subsequent verses 17 and 18 might make the connection even stronger: “You shall not tolerate a sorceress. Whoever lies with a beast shall be put to death.” Images of the phallic unicorn and the quiescent virgin in contemporaneous Christian art have been interpreted through the lenses of gender and sexuality (Sandler 1985; Caviness 1993; Caviness 2001, chap. 3), and it may well be the case that one goal of the Rothschild Pentateuch picture is to cast aspersions on any woman who acts so dubiously. It is tempting to extend this and suggest that the painted image inverts the bestiary allegory to make a polemical argument specifically about Mary as both sorceress and bestial fornicator, but I have not found other overtly anti-Christian messages in the book.If a man seduces a virgin for whom the bride-price has not been paid and lies with her, he must make her his wife by payment of the bride-price. If her father refuses to give her to him, he must still weigh out silver in accordance with the bride-price for virgins.

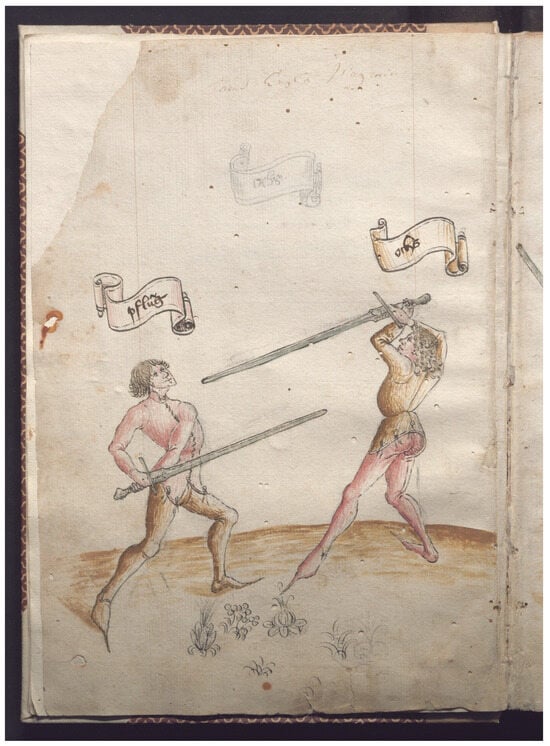

The goring ox in the Jewish tradition and the unicorn in the Christian tradition share the common fate of being killed. In medieval depictions, the hunter of the unicorn is occasionally represented as an armed knight, especially in manuscripts other than bestiaries, and this is the choice made by the Rothschild Pentateuch artist. Unusually, however, this knight is not in the act of spearing or killing the ox-unicorn, even though he is heavily armed and approaching threateningly from behind with his massive sword raised above his head. This stance corresponds to one of the four standard poses for the use of the longsword described in medieval fencing books, an observation I owe to Alexis Minault of the Université de Poitiers. This pose was called the Ox (Ochs); the others are the Plow [Pflug], the Fool [Alber], and From the Roof [Vom Tag]). A depiction of these poses, each clearly labeled, appears in an illustrated manuscript of 1452 (Rome, Bibliotheca dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana Cod. 44 A 8, fol. 1v; Figure 3); an illustrated fencing manual almost contemporaneous with the Rothschild Pentateuch, Leeds, Royal Armouries Museum MS I.33, from c. 1300 and likely made around Würzburg, does not use these terms or provide a precise visual parallel. The upraised position of the knight’s sword, which points forward from the top of the head, demonstrates why this pose was dubbed the Ox, a correspondence that becomes particularly clear in the Rothschild Pentateuch when the swordsman is juxtaposed directly with the horned ox. As Sara Offenberg has shown, medieval European Jews were no strangers to contemporary swordsmanship and its depictions, and they sometimes incorporated such imagery into their own decorated books (Offenberg 2019, 2021a, 2022). Figures wielding the sword and buckler can be found in at least two Hebrew manuscripts: the North French Hebrew Miscellany of 1278–80 (London, British Library Add. MS 11639) and a Hebrew Bible of 1304 made in German Ashkenaz (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS hébr. 9, fols. 104v–105r (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10548441n/f217.item)). In both cases, these figures can be read as common gentile fighting men and negative exemplars of violence, particularly in the shadow of the Rindfleisch riots of 1298. The Rothschild Pentateuch was made at roughly the same time and place as these two manuscripts and is another example of imagery in a Hebrew book that demonstrates an informed awareness of contemporaneous sword culture. In this case, however, the swordsman need not be construed as a negative type; rather, his appearance here is due to his iconographic role in the unicorn-hunt scene, which the artist modified in several ways. Motivated by the text of Exodus 21 and 22, the pentateuch artist cleverly transformed the unicorn into an ox and thereby forged a linguistic-iconographic connection between the ox and the “Ochs” hunter, both of whom are rendered in red and green with repetitive small stipple marks. Whether the clear awareness of the “Ochs” nomenclature can help determine the precise origin of the manuscript in a German- (or Yiddish-)speaking locale remains to be determined.

Figure 3.

Rome, Bibliotheca dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana, Cod 44 A 8, fol. 1v: Ochse [the Ox] and Pflug [the Plow]. (Reproduction courtesy of the Bibliotheca dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana).

4. The Goat

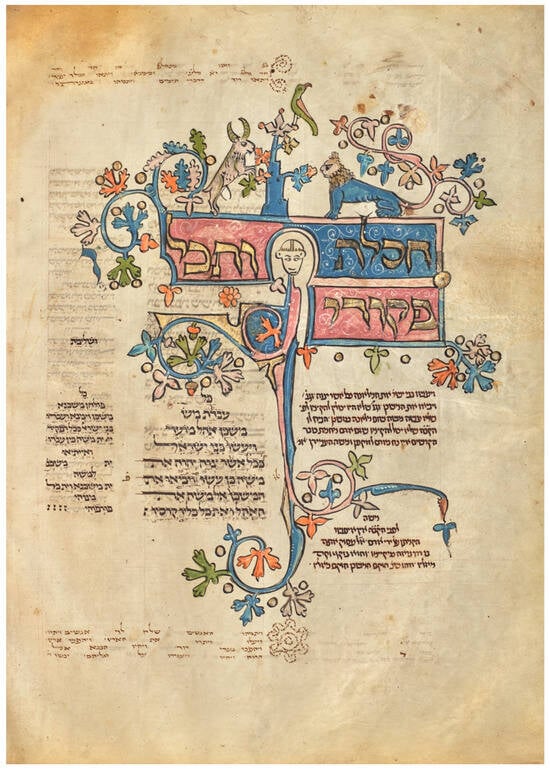

The third example of bestiary-related imagery in the Rothschild Pentateuch also hinges on linguistic wordplay (Figure 4). As in some other Hebrew bibles localized to western and eastern France, this one marks a special reading beginning at Exodus 39:32 (VaTeichal), which recounts the completion of all the work of building the wilderness tabernacle (comparisons are Oxford, Bodleian MS Kennicott 3 (https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/28cb1120-e016-465b-a1c8-95cc6e1b3812/surfaces/679c7e1b-2e20-4e47-ab85-acd865d078d6/), written in 1299 and attributed to Aquitaine (Steimann 2023), and Paris, BnF, MS hébr. 36 written in Poligny in 1300 (Sed-Rajna 1994, 158–65)). Approximately in the center of the decoration on folio 220v is a tree; on the right, a lion peers at a small (canine?) head peeping from behind a leaf; and on the left, a horned animal leans against the tree. The depiction of this last animal is entirely consistent with bestiary images of the goat (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast163.htm). According to the bestiary text, the goat likes to live on high mountains, it has sharp eyesight, and its blood can dissolve diamonds, but none of these facts can be connected to the Exodus text. One possible textual motivation may be the goat hair (עזים) that the women spun to make the tent of the tabernacle (Ex 26:7, 35:26, 36:14). There were many materials used in the tabernacle, however, so this does not fully explain the appearance of the goat here. Another factor could be a play on the Latin word for goat, caper, which can be rendered in Hebrew as כפר. This is the root of כפרת, the covering of the ark at the heart of the tabernacle, which is mentioned in Exodus 39:35 and 40:20. Admittedly, this ark cover, originally described in Exodus 25, was made entirely out of gold, not goat hair, but it seems more than coincidental that the “caper” appears on a page that opens a biblical passage dedicated to the work of the tabernacle. Even so, this interpretation of the goat does not account for all the imagery on the page, and it does not seem as patently clear as the lion and unicorn examples. But like the “Ox” swordsman, the depiction of the “caper” suggests that the artist of the Rothschild Pentateuch was manipulating familiar bestiary imagery with an awareness of linguistic interplay among Latin, German/Yiddish, and Hebrew.

Figure 4.

Los Angeles, Getty Museum, MS 116, fol. 220v: VaTeichal [Exodus 39:32–40:38]. (Acquired with the generous support of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; reproduction courtesy of The Getty Museum under Creative Commons CCO 1.0 Universal).

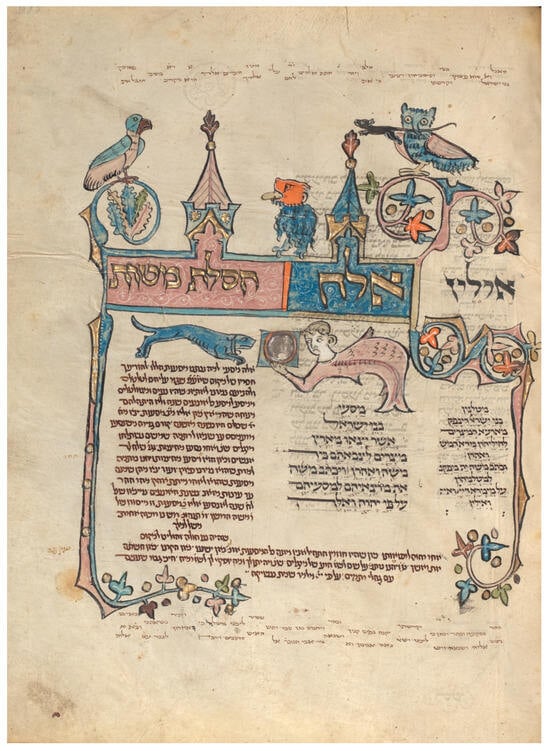

5. The Mermaid; The Owl

The next examples appear 173 folios later, at the opening of the Torah portion Masei (Num 33–36:13) on folio 393r (Figure 5). As in the VaTeichal page just discussed, there are multiple elements assembled here, not all of which can be connected to the bestiary, nor do they seem to cohere into a single, synthetic reading. The element that is most striking is the fish-bodied woman holding a mirror, immediately recognizable as a version of the bestiary’s mermaid (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast283.htm). The mermaid was often confused or conflated with the siren (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast246.htm); here, the figure does not seem to be a siren because she does not appear with others luring sailors to their deaths (sirens are also often represented with the bodies of birds). Still, both mermaids and sirens were frequently depicted holding a mirror, a sign of their vanity and lust. There is nothing overtly sexual in the reading for Masei, although in most years it was combined with the previous portion, Matot (Num 30:2–32), which begins with Moses’s command to the Israelites to wage war against the Midianites. The reason for this command is the episode at Baal-Peor recounted earlier, in Numbers 25, in which the Midianite women tempted the Israelite men into sexual sin. A simple reading of the mermaid-siren on 393r is that she recalls these Midianite women, whose seductive ways would lead to the spiritual destruction of the Israelites. Granted, such a depiction would have made more sense for the reading that includes Numbers 25 (the portion of Balak), or at least for Matot. Perhaps it was meant to serve as a summary image for the book of Numbers, of which Masei is the last portion; or perhaps, as Eva Frojmovic has recently suggested, there is no particular connection to the Torah text at all (Frojmovic 2023).

Figure 5.

Los Angeles, Getty Museum, MS 116, fol. 393r: Masei [Numbers 33–36:13]. (Acquired with the generous support of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; reproduction courtesy of The Getty Museum under Creative Commons CCO 1.0 Universal).

Frojmovic’s proposed reading of the female figure in the Rothschild Pentateuch accounts for multiple, even contradictory, interpretations. On the one hand, the siren could be a sign for the female seductress, and some medieval Jewish commentaries did discuss the possibility of human-siren sexual relations. On the other hand, because the figure’s breasts have been covered and its hair cropped short, it might be read instead as a rejection of the feminine voice in a liturgical book meant for male Jewish ears and eyes. Frojmovic productively sets the Rothschild picture against one in a contemporaneous liturgical pentateuch now in Wrocław (Library of the National Ossoliński Institute of Poland, Ms. Pawl. 141, fol. 397v). In the Wrocław Pentateuch, which is little known and deserves further study, the scene is clearly a long-haired siren, nursing her young and stretching out her hand to tempt the sailors on the nearby ship, a depiction based on the Odyssey and common in bestiaries. Not only is the scene iconographically more expansive than the vignette in the Rothschild Pentateuch but the textual context is also different: it appears with the prophetic haftarah reading comprising 1 Samuel 20:18–42, used for a sabbath on the day before the New Month (Machar Chodesh). The text is about the deep relationship between David and Jonathan, and Frojmovic offers a theoretically rich reflection on the monstrous female siren in light of male desire and liturgical performance. This interpretation is more satisfying for the Wrocław Pentateuch than for Rothschild, but what clearly emerges from the two manuscripts is that some Jewish audiences were familiar with siren lore and its visual manifestations, which were manipulated in different, perhaps overlapping, ways in the two books.

A second element on the Rothschild Pentateuch page can also be connected to the bestiary tradition. At the upper right is an owl, which seems to be grasping a mouse that runs in front of its beak, perhaps escaping. It is quite rare for these two creatures to appear together in the bestiary. One exception is in the above-mentioned Bodley 764, fol. 73r (https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/e6ad6426-6ff5-4c33-a078-ca518b36ca49/surfaces/dface768-4fd5-40b8-8cbc-e6fdc0e9ef53/), although there the owl holds the mouse firmly underfoot, without any of the ambiguity of the pentateuch picture. In the standard bestiary, owls (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast245.htm) are viewed negatively as dirty birds of the night, moralized in the Christian text as the Jews who prefer darkness. The mouse was understood to have various characteristics, such as being conceived through licking, and medical applications, such as mixing mouse ash with honey and oil to cure earaches. Perhaps the mouse dashing away from the owl is an oblique reference to stopping up the ears to escape the siren’s song; perhaps the owl is somehow subverting the negative Christian interpretation of the Jews. Both seem like rather forced readings, and it is difficult to relate the owl and mouse pair to the rest of the images on the page or to the Masei text below.

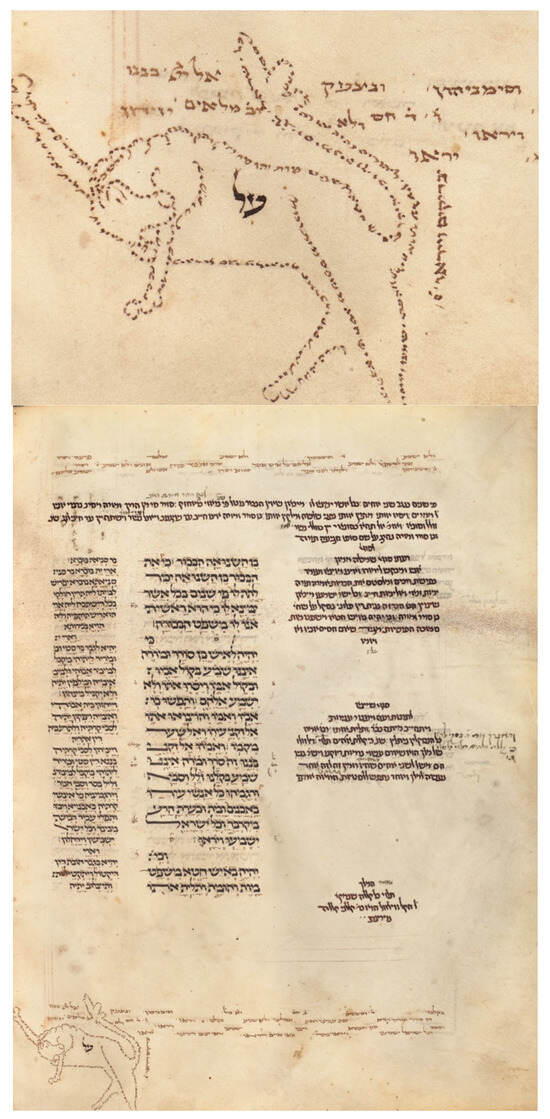

6. The Wolf

The final instance of an image rooted in the bestiary tradition likewise might be related to the biblical text, but only in an allusive way (Figure 6). It is not one of the paintings decorating a weekly reading opening but is among the many occasions in the Rothschild Pentateuch, consistent with practice in medieval Ashkenaz, when parts of the masoretic text are rendered in decorative, sometimes figurative shapes (Sirat and Avrin 1981; Halperin 2013). At the bottom of fol. 457v, a wolf is shown biting its own leg (Mintz and Morrison 2019). According to the bestiary, the wolf (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast180.htm) will sneak into a sheepfold like a tame dog, and if it steps on a branch and makes a noise, it bites its own leg as punishment. This action was commonly depicted in bestiaries; in the text, the wolf was broadly interpreted as the devil, and it may be possible to assign a generally negative meaning in the Rothschild Pentateuch as well. Most of the text on 457v comprises Deuteronomy 21:18–21, the case of the rebellious son (ben sorer u’moreh). According to the biblical text, a stubborn son who will not listen to his parents should be brought before the elders of the city to be punished with death by stoning. The Mishnah, the Talmud, and the medieval commentators explored this subject in great detail, concluding that it was so difficult to fulfill all the necessary legal requirements that there never had been and never would be an actual case of the ben sorer u’moreh (Tractate Sanhedrin 70a–72a). Nonetheless, at least by way of warning, the wayward son is characterized as one who is recalcitrant, a glutton for meat, and a thief. In this light, the micrographic wolf on the page could well be read as a sign for the rebellious son in the text above. Although the specific act of biting the leg does not seem necessary for this interpretation, it would have been useful in identifying the animal specifically as the wolf who steals from the sheepfold.

Figure 6.

Los Angeles, Getty Museum, MS 116, fol. 457v: Ki Teitzei [Deuteronomy 21:10–25:19], with detail. (Acquired with the generous support of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder; reproduction courtesy of The Getty Museum under Creative Commons CCO 1.0 Universal).

Yet there are internal and external reasons for hesitation regarding this proposition. Within the Rothschild Pentateuch itself, there seem to be very few instances in which the micrography has been designed in relation to the biblical text, although further research may reveal more such cases (or, more likely, figurative micrography that responds to the masoretic text itself). In the commentary tradition, there is no evidence that the rebellious son was likened to a wolf or to any other animal. David Shyovitz has explored the rich medieval Jewish literature pertaining to the werewolf, which functioned as a locus for rabbinic meditations about the spectrum of God’s creation and what, exactly, it meant to be human and not animal (Shyovitz 2017, esp. chap. 4). In the Sefer Hasidim, the core text of the German Pietists in the thirteenth century (Baumgarten et al. 2021), there is an account of a baby being born with teeth and a tail—i.e., with the characteristics of a wolf—and people argued that it should be killed before it could eat anyone. The sage ruled that it was enough to remove the teeth and tail to normalize this defective body. There is a certain parallel to the biblical case of the rebellious son, who is also killed before he can act viciously, but Shyovitz calls this text in the Sefer Hasidim “an otherwise obscure exemplum” (Shyovitz 2017, p. 143). For this reason, using it as an interpretive key for the micrographic wolf in the Rothschild Pentateuch would be to cherry-pick a single obscure text from a particular context and juxtapose it to an equally isolated visual example in another (albeit relatively close) one. If there were further evidence in the Rothschild Pentateuch of an affiliation with ideas in Sefer Hasidim and other Pietist texts, like those Sara Offenberg has discerned in the North French Hebrew Miscellany (Offenberg 2013), then that would bolster the argument, but I have not recovered any.

7. Bestiary Images in Three Hebrew Manuscripts

The images in the Rothschild Pentateuch that are related to the pictorial and textual bestiary traditions demonstrate that the source material was used in different ways. In the case of the lion and the unicorn, the artist adhered fairly closely to the bestiary images and their ideological import to express ideas found in a relevant biblical passage. The representations of the wolf, goat, mermaid-siren, owl, and mouse are linked visually to bestiary examples, but their relation to the biblical text is tenuous. This is not surprising, however; the pentateuch’s decorated pages are filled with over five hundred individual iconographic motifs, some of which can be interpreted in light of the pertinent biblical text, whereas many others defy such simple correlations (a subject I plan to explore in a forthcoming study). Even in those cases meaningfully rooted in the bestiary tradition, the artist manipulated the images to fit them more appropriately to the Hebrew biblical context, and the unicorn in particular was transformed innovatively, in part for linguistic reasons (unicorn → ox + ox hunter/swordsman). A second case, the goat, may also have been stimulated by Latin-Hebrew wordplay, even if the animal’s placement in the pentateuch is not necessarily the most logical.

The Rothschild Pentateuch was not the only Hebrew manuscript with images related to the bestiary. The Wrocław Pentateuch has at least one detailed depiction of the siren luring sailors, and there are one to two dozen isolated vignettes in the North French Hebrew Miscellany. This last manuscript is a vast compendium of biblical, liturgical, paraliturgical, legal, grammatical, and poetic texts, totaling an astonishing 740 folios, a great many of them with one or more painted decorations (Schonfield 2003). Here too, the manuscript’s bestiary pictures—which appear as isolated vignettes that mark the beginning of a new text—represent a tiny fraction of the book’s imagery; and they have only been considered briefly by Yael Zirlin in the facsimile’s commentary volume (Zirlin 2003, esp. pp. 130–34). Some, like the fox and the hedgehog, contain specific details that reveal direct derivation from the bestiary; others, like the cock, the crane, or even the pelican, are sufficiently generic to make their precise source less certain. In her overview, Zirlin rehearses how some of these animals were interpreted in the bestiary. The fox depicted on fol. 126r, for example, rolls in the red mud and plays dead in order to snatch the unsuspecting birds who land on it; according to the bestiary (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast179.htm), he represents the devil (cf. Bodley MS 764, fol. 26r). The most characteristic feature of the hedgehog (https://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast217.htm) is the way it shakes vines or trees to get fruits to fall on the ground, then rolls on them with its spikes to take them home to feed the young. But in neither case is there any apparent connection to the miscellany’s texts. The fox marks the prophetic reading for Shabbat HaChodesh, the special sabbath inaugurating the month of Nissan (highlighted by Passover); it comprises Ezekiel 45:18–46:15 and is a prophetic description of the sacrifices brought in the restored Temple. The hedgehog on 187r appears with a text called Pitum HaKetoret, a reading at the end of the prayer book that describes the ingredients of the incense offerings in the Temple (Munk 1961–1963, p. 193, pp. 58–59). Perhaps some rationale for the pairing of the fox and hedgehog with these texts will be uncovered, and the inclusion of other bestiary animals in the miscellany might someday be clear, but at present it would seem that Zirlin was essentially correct in concluding that “the choice of images from the Bestiary was made at random” (Zirlin 2003, p. 134).

Randomness, however, need not be equated with meaninglessness. Zirlin wondered whether the (presumed) Christian artist of the North French Hebrew Miscellany inserted Christological imagery like the pelican to spite the book’s Jewish patron, but then concluded that such imagery was included “simply as decoration”. In light of more recent scholarship that demonstrates the degree to which imagery in the miscellany was targeted to the Jewish reader-viewer, perhaps the scribe himself (named Benjamin), we can conclude that this individual had a high “visual literacy” (Offenberg 2013, 2022; on visual literacy, see Diebold 1992). Even if the specific bestiary images were not selected with regard to particular Hebrew texts, their meaning in the miscellany should be understood to lie somewhere between the opposing poles of active spite and simple decoration. Although she does not consider the miscellany at any length, Frojmovic makes the plausible suggestion that the inclusion of bestiary imagery in Hebrew books made around the year 1300 enabled their owners to demonstrate knowledge of this “scientific” material and even to tame it within the realms of Bible study and liturgical practice (Frojmovic 2023, p. 3). Yet setting the manuscripts side by side reveals important nuances. In the North French Hebrew Miscellany, there seems to be no apparent programmatic deliberation in matching animals to texts, whereas the expansive siren scene in the Wrocław Pentateuch seems quite intentional. The Rothschild Pentateuch boasts a spectrum, from imagery that was deeply considered and manipulated to pictures that may be as random as those in the miscellany. It is important, therefore, to recognize that, even in three medieval Hebrew manuscripts made at roughly the same time and place, there was no single, unified Jewish response to or use of bestiary imagery.

8. Appropriation or Adaptation?

This cluster of pictorial evidence nevertheless expands our understanding of the degree to which some medieval Jews were aware of, conversant with, and desirous of incorporating bestiary knowledge in texts and images. In an examination of the writings of the thirteenth-century German Pietists, David Shyovitz demonstrated parallels and interconnections with contemporary Christian uses of bestiary lore in preaching (Shyovitz 2014). This study is part of an increasingly rich scholarly landscape that explores the intimate, and not always polemical, interactions between Jews and Christians in western medieval Europe (key works, all with further literature, include Berger 2010; Shatzmiller 2013; Baumgarten and Galinsky 2015; Baumgarten et al. 2017; Barzilay et al. 2022). Katrin Kogman-Appel (2000, 2005); Sarit Shalev-Eyni (2005, 2014); and Sara Offenberg (2015, 2021b), have made significant contributions to our understanding of the role that visual imagery played in the multifaceted ways medieval Ashkenazi Jews responded to, rejected, incorporated, and transformed Christian imagery in their own books. Marc Epstein, in particular, has long been at the forefront of investigating the contours of animal lore in Jewish art (Epstein 1997, 2019), a subject recently taken up by Elina Gertsman (2022, 2023). Two decades ago, Epstein began to overturn the notion that the appearance of such motifs as the elephant in Hebrew manuscripts was the result of the desire for “mere decoration” or “borrowing” from the majority Christian culture (Epstein 1994). In his subtitle and throughout that essay, Epstein uses the word adapt to describe the process of how the Jewish makers and users of their books both adopted and transformed source material from contemporaneous Christian culture (see also the essays in Epstein 2015). More recently, Elisheva Baumgarten has argued cogently that this process should be described as an appropriation rather than an absorption or acculturation to account for the fact that the Jews in question were agents who actively took Christian ideas, objects, and practices as their own on an ongoing basis (Baumgarten 2018). There is certainly ample evidence for such processes and for the way that medieval Jewish and Christian lives were “entangled”, another useful term introduced by Baumgarten, Mazo Karras, and Mesler (Baumgarten et al. 2017). I hesitate, though, to describe the evidence of the bestiary material as an appropriation, which can carry the negative valence of taking something that is not one’s own. Did knowledge about the lion or the unicorn “belong” to Christians? Or was it part of a common body of cultural knowledge that different religious groups could deploy as they deemed suitable? Granted, there are many more examples of Christians writing about and illustrating the unicorn than of Jews doing so, but ideas about unicorns were not inherently exclusive to Christians (Epstein 1997, 104 and note 48). And even presuming that the first—or some—examples of Jews using the unicorn did signal an appropriation; does that mean that every subsequent use continued to be such a conscious transformation of a recognizably Christian, “other” cultural product? This was essentially the idea behind Ivan Marcus’s preferred term, inward acculturation (Marcus 1996), which Baumgarten has sought to update.

In the end, no one scholarly term, whether those discussed here or such others as hybridity and transculturation (Safran 2014), can account for the complex interactions between Christians and Jews in medieval Ashkenaz. What the bestiary material in this study suggests, however, is that in some cases, a neutral term like adaptation may be most suitable because it is the least charged and most flexible (Hutcheon 2013; Leitch 2017; Cutchins et al. 2018). When the artist of the Rothschild Pentateuch—who I am presuming for the moment to have been Jewish—executed his images of the lion; unicorn-ox; and goat; he did so with knowledge of the Christian bestiary tradition; which he adapted for use in the Hebrew book. But we do not know the degree to which this knowledge may have been filtered already through an inward acculturation, what his attitude was toward this Christian source, or whether his adaptation was meant consciously as an appropriation—polemical or otherwise. If the pentateuch artist was Christian, then we simply shift the question to the book’s reader-viewer, Joseph ben Joseph Martel, whom we must consider in any event. We cannot say whether Joseph was involved in shaping the decorative program of his book, and it is possible that he really did see the pictures as simply decorative and delightful. From the limited evidence of the pentateuch itself, we cannot yet know whether Joseph considered the unicorn to be a specifically Christian motif suitable for appropriation, whether he himself had ever read a Christian bestiary, or what his general attitude toward his Christian neighbors may have been. But such images as the lion and unicorn-ox presuppose, or at least encourage us to propose, that Joseph’s experience of his pentateuch was enhanced precisely because he had knowledge of their meaning, if not their precise sources and adaptation. Like the patrons of the Wrocław Pentateuch and the North French Hebrew Miscellany, Joseph ben Joseph was a late thirteenth-century Ashkenazi Jew with the means to have a richly decorated book. And in Joseph’s case, at least, it would seem that he was a reader-viewer whose appreciation of the book was enriched by some understanding of the animal referents in it. By adapting and incorporating elements from the bestiary tradition, the artist of the Rothschild Pentateuch, whether Christian or Jewish, sought to stimulate Joseph to think more deeply about the meaning of the sacred text. Even if the mechanics of that process remain murky, we can appreciate the complexity of the pentateuch’s decorative program and be encouraged to continue pondering it further.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data has been contained in the article.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was undertaken with support from The Leverhulme Trust, whom I gratefully acknowledge. I thank the Centre for Jewish Studies and the Institute for Medieval Studies at the University of Leeds for the opportunity to present a version of this material in October 2023. Sylvia (Xin Yue) Wang and Amy Miller were especially helpful in providing research support during the unfortunate period when the British Library was compromised by a cyberattack; unfortunately this has also precluded adding hyperlinks to the library's digitized manuscripts. All other links were accessed on 16 January 2024. Linda Safran, as always, was a valuable reader at every stage of this work, and I thank as well the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the essay. Eva Frojmovic has long been a treasured interlocuter and generously provided an advance copy of her article on the same material. Finally, I am most grateful to Sara Offenberg, whose own work was an important motivation for the current article; her reading of the text enhanced my arguments. I am thankful to all these scholars for their assistance but am solely responsible for the contents of the essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Barzilay, Tzafrir, Eyal Levinson, and Elisheva Baumgarten. 2022. Jewish Everyday Life in Medieval Northern Europe, 1080–1350: A Sourcebook. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva. 2018. Appropriation and Differentiation: Jewish Identity in Medieval Ashkenaz. AJS Review 42: 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva, and Judah Galinsky, eds. 2015. Jews and Christians in Thirteenth-Century France. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva, Elisabeth Hollender, and Ephraim Shoham-Steiner. 2021. Sefer Ḥasidim: Book, Context, and Afterlife. Studies in Honor of Ivan G. Marcus. Jewish History 34: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarten, Elisheva, Ruth Mazo Karras, and Katelyn Mesler, eds. 2017. Entangled Histories: Knowledge, Authority, and Jewish Culture in the Thirteenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, David. 2010. Persecution, Polemic, and Dialogue: Essays in Jewish-Christian Relations. Boston: Academic Studies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caviness, Madeline. 1993. Patron or Matron? A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed. Speculum 68: 333–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviness, Madeline. 2001. Reframing Medieval Art: Difference, Margins, Boundaries. Available online: https://dca.lib.tufts.edu/caviness/ (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Clark, Willene B. 2006. A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-Family Bestiary. Commentary, Art, Text and Translation. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cutchins, Dennis, Katja Krebs, and Eckart Voigts, eds. 2018. The Routledge Companion to Adaptation. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Kay. 2017. The Bar Books: Manuscripts Illuminated for Renaud de Bar, Bishop of Metz (1303–1316). Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- De Hamel, Christopher. 2008. Book of Beasts. A Facsimile of MS Bodley 764. Oxford: Bodleian Library. [Google Scholar]

- Diebold, William. 1992. Verbal, Visual, and Cultural Literacy in Medieval Art: Word and Image in the Psalter of Charles the Bald. Word & Image 8: 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, Elizabeth, and Melanie Holcomb. 2019. Cosmic Creatures: Animals in Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts. In Book of Beasts. Los Angels: J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 231–33. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc Michael. 1994. The Elephant and the Law: The Medieval Jewish Minority Adapts a Christian Motif. Art Bulletin 76: 465–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Marc Michael. 1997. Dreams of Subversion in Medieval Jewish Art and Literature. University Park: Pennsylvania State University. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc Michael, ed. 2015. Skies of Parchment, Seas of Ink: Jewish Illuminated Manuscripts. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc Michael. 2019. Bestial Bodies on the Jewish Margins: Race, Ethnicity and Otherness in Medieval Manuscripts Illuminated for Jews. In Monsters and Monstrosity in Jewish History from the Middle Ages to Modernity. Edited by Iris Idelson-Shein and Christian Wiese. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Jacob J. 1981. The Ox That Gored. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 71: 1–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, trans. 1936. Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. London: Soncino Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frojmovic, Eva. 2023. The Siren’s Seed. Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture 16: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertsman, Elina. 2022. Animal Affinities: Monsters and Marvels in the Ambrosian Tanakh. Gesta 61: 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertsman, Elina. 2023. ‘The Breath of Every Living Thing’: Zoocephali and the Language of Difference on the Medieval Hebrew Page. Art History 46: 714–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzberg, Louis. 1947. The Legends of the Jews, 3rd ed. Translated by Paul Radin. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, Joseph. 1987. The Sacrifice of Isaac in Medieval Jewish Art. Artibus et Historiae 16: 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, Dalia-Ruth. 2013. Illuminating in Micrography: The Catalan Micrography Mahzor; MS Heb 8°6527 in the National Library of Israel. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Heck, Christian, and Rémy Cordonnier. 2012. The Grand Medieval Bestiary: Animals in Illuminated Manuscripts. New York and London: Abbeville Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon, Linda. 2013. A Theory of Adaptation, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2000. Coping with Christian Pictorial Sources: What Did Jewish Miniaturists Not Paint? Speculum 75: 816–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2004. Jewish Book Art between Islam and Christianity: The Decoration of Hebrew Bibles in Medieval Spain. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2005. The Tree of Death and the Tree of Life: The Hanging of Haman in Medieval Jewish Manuscript Painting. In Between the Image and the Word: Essays in Honor of John Plummer. Edited by Colum Hourihane. University Park: Pennsylvania State University, pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Leitch, Thomas, ed. 2017. The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, Ivan. 1996. Rituals of Childhood: Jewish Acculturation in Medieval Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Contreras, Elvira. 2013. Masora and Masoretic Interpretation. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1, pp. 542–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, Sharon Liberman, and Elizabeth Morrison. 2019. Catalogue entry 78: Rothschild Pentateuch. In Book of Beasts. Los Angels: J. Paul Getty Museum, p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Elizabeth, and Larisa Grollemond, eds. 2019. Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Munk, Elie. 1961–1963. The World of Prayer. 2 vols. New York: Feldheim. [Google Scholar]

- Neusner, Jacob, and Alan J. Avery Peck, eds. 2005. Encyclopedia of Midrash: Biblical Interpretation in Formative Judaism. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2013. Illuminated Piety: Pietistic Texts and Images in the North French Hebrew Miscellany. Los Angeles: Cherub Press. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2015. Mirroring Samson the Martyr: Reflections of Jewish-Christian Relations in the North French Hebrew Illuminated Miscellany. In Jews and Christians in Thirteenth-Century France. Edited by Elisheva Baumgarten and Judah D. Galinsky. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 203–16. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2019. Up in Arms: Images of Knights and the Divine Chariot in Esoteric Ashkenazi Manuscripts of the Middle Ages. Los Angeles: Cherub Press. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2021a. Sword and Buckler in Masorah Figurata: Traces of Early Illuminated Fight Books in the Micrography of Bible, BnF, MS héb. 9. Acta Periodica Duellatorum 9: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2021b. Illustrated Secret: Esoteric Traditions in the Micrography Decoration of Erfurt Bible 2 (SBB MS Or. Fol. 1212). In Philology and Aesthetics: Figurative Masorah in Western European Manuscripts. Edited by Hanna Liss and Jonas Leipziger. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2022. Is it a Good Knight or a Bad Knight? Methodologies in the Study of Polemics and Warriors in Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts. Jewish Thought 4: 41–74. [Google Scholar]

- Petzold, Kay Joe, and Hanna Liss. 2019. Masorah. In The Encyclopedia of the Bible and Reception. Berlin: De Gruyter, vol. 17, pp. 1267–80. [Google Scholar]

- Safran, Linda. 2014. The Medieval Salento. Art and Identity in Southern Italy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, Lucy Freeman. 1985. A Bawdy Betrothal in the Ormesby Psalter. In A Tribute to Lotte Brand Philip, Art Historian and Detective. Edited by William Clark, Colin Eisler, William S. Heckscher and Barbara Barbara G. Lane. New York: Abaris, pp. 154–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, Lucy Freeman. 2008. Studies in Manuscript Illumination, 1200–1400. London: Pindar. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, Devorah. 2013. Isaac on Jewish and Christian Altars: Polemic and Exegesis in Rashi and the Glossa Ordinaria. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schonfield, Jeremy, ed. 2003. The North French Hebrew Miscellany (British Library, Add. MS. 11639). London: Facsimile Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Sed-Rajna, Gabrielle. 1994. Les manuscrits hébreux enluminés des bibliothèques de France. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev-Eyni, Sarit. 2005. Iconography of Love: Illustrations of Bride and Bridegroom in Ashkenazi Prayerbooks of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century. Studies in Iconography 26: 27–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev-Eyni, Sarit. 2014. The Mahzor as a Cosmological Calendar: The Zodiac Signs in Medieval Ashkenazi Context. Ars Judaica 10: 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev-Eyni, Sarit. 2020. Isaac’s Sacrifice: Operation of Word and Image in Ashkenazi Religious Ceremonies. Entangled Religions 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatzmiller, Joseph. 2013. Cultural Exchange: Jews, Christians and Art in the Medieval Marketplace. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shyovitz, David. 2014. Beauty and the Bestiary: Animals, Wonder, and Polemic in Medieval Ashkenaz. In The Jewish-Christian Encounter in Medieval Preaching. Edited by Jonathan Adams and Jussi Hanska. New York: Routledge, pp. 215–23. [Google Scholar]

- Shyovitz, David. 2017. A Remembrance of His Wonders: Nature and the Supernatural in Medieval Ashkenaz. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sirat, Colette, and Leila Avrin. 1981. La lettre hébraïque et sa sgnification / Micrography as Art. Paris and Jerusalem: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Israel Museum, Department of Judaica. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, Shalom. 1967. The Last Trial: On the Legends and Lore of the Command to Abraham to Offer Isaac as a Sacrifice: The Akedah. Translated by Judah Goldin. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Steimann, Ilona. 2023. Masoretic Manuscripts from France: The Jonah Pentateuch (BL, Add. MS 21160) Revisited. Corpus Masoreticum Working Paper 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, David. 2012. The Hebrew Bible in Europe in the Middle Ages: A Preliminary Typology. Jewish Studies, an Internet Journal 1: 235–322. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, David. 2017. The Jewish Bible: A Material History. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stones, Alison. 2013–2014. Gothic Manuscripts 1260–1320. 4 vols. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Stones, Alison. 2014. Les manuscrits de Renaud de Bar. In L’écrit et le livre peint en Lorraine, de Saint-Mihiel à Verdun (IXe-XVe siècles): Actes du colloque de Saint-Mihiel (25–26 octobre 2010). Edited by Anne-Orange Poilpré and Marianne Besseyre. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 269–310. [Google Scholar]

- Swarzenski, Georg, and Rosy Schilling. 1929. Die illuminierten Handschriften und Einzelminiaturen des Mittelalters und der Renaissance in Frankfurter Besitz. Frankfurt am Main: J. Baer. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, John. 1986. The Oak King, the Holly King, and the Unicorn: The Myths and Symbolism of the Unicorn Tapestries. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, Jean. 2008. Les Marges à Drôleries des Manuscrits Gothiques (1250–1350). Geneva: Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Zirlin, Yael. 2003. The Decoration of the Miscellany: Its Iconography and Style. In The North French Hebrew Miscellany. London: Facsimile Editions, pp. 75–161. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).