1. Introduction

“When there’s a tragic or chaotic situation happening, there are calm waters on the other side, but you’re just in a wave right now. So just wait. And one day you’ll make peace. You’ll be on the other side. It’ll be calm.”

—Anna, research participant

Religion and spirituality (R/S) are profound sites of meaning making, often acting as the existential scaffolding that upholds our sense of stability, coherence, purpose, and connection (

Tedeschi and Calhoun 1996). R/S can emerge as a site for healing trauma, offering a key source of coping, safety, and connection (

Bryant-Davis and Wong 2013). Further complexity enters the conversation as R/S may be the key source of harm, and consideration for the ways in which RS may be deeply interwoven in spiritual and emotional and cognitive wounds is needed. This phenomenon of spiritual wounding can be conceptualized as spiritual struggle or spiritual distress (SD), defined by

Abu-Raiya et al. (

2015) as “tension, strain, and conflict about sacred matters with the supernatural, with other people, and within oneself” (p. 565).

To date, the majority of SD research has employed quantitative methods with white, Christian populations in the United States, evidencing that SD can negatively affect mental health and wellbeing. (

Abu-Raiya et al. 2015;

Ano and Pargament 2012;

Exline et al. 2000;

Noth and Lampe 2020). While many studies have demonstrated the relationship between religion, spirituality, health, and positive mental health outcomes and the posttraumatic recovery process (

Captari et al. 2018;

Harper and Pargament 2015;

Koenig 2015), little research has explored the meaning and experience of SD from the perspective of women of evangelical Christian (EC) backgrounds in a Canadian context.

With the aim of furthering the conversation about SD, resilience, and posttraumatic growth, this paper will highlight the results of an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) study on the lived experience of SD for women of EC backgrounds in a Canadian context. We begin by offering a brief exploration of posttraumatic growth. Subsequently, we expositthe study methods and background information on the population.The study results are then presented, alongside an ocean-themed model which illustrates the participants’process. In closing, the implications of the findings are discussed with links to the facilitation of posttraumatic growth.

Posttraumatic Growth and Spirituality (PTG)

Spirituality can certainly be an essential component of coping following trauma, including SD-related wounds. For example, individuals may receive comfort in religious or spiritual communities, connect with the divine through prayer, and find solace in meditation and ceremony. Scholarship exploring PTG has allowed for conversations on trauma to move beyond its damaging impact, to curiosity about possibilities, development, and resilience factors following traumatic experiences.

Tedeschi and Calhoun (

1996) coined this term, which includes five domains where individuals can experience change and growth, including finding a greater appreciation of life, improved or changed relationships with others, opening oneself to new possibilities in life, recognizing and relying on one’s personal strength, and spiritual change. We argue that each of these areas can be linked to spirituality. Further scholarship exploring PTG and its intersections with numerous lived experiences across the lifespan and in different contexts and populations (

Boynton and Vis 2022) has continued, including individuals living with HIV or experiencing sexual assault (

Frazier et al. 2001).

Spirituality may serve as an avenue for meaning making, both of traumatic events and of life as a whole (

Pargament et al. 2006). As trauma can rupture an individual’s sense of goodness, coherence, and safety, a key grounding task can be making meaning through a spiritual lens.

Vis and Boynton (

2008) coined “transcendent meaning making” (p. 74) as a core spiritual task in the trauma process, which moves beyond the cognitive to incorporate “a deeper intuitive understanding of one’s relationship with themselves and their existence in the world” (p. 74). This process fosters conscious and intentional rumination and an intuitive and spiritual re-orienting movement from places of despair towards places of hope as we search for a new worldview that can hold the full truth of our experiences.

Vis and Boynton (

2008) also delineated three key theoretical frames from the literature through which PTG is understood. Firstly, positive coping may result from an individual’s meaning-making process as they re-orient after worldview disruption. Additionally, having gone through trauma, individuals may have little choice but to develop coping strategies, some of which may prove meaningful and sustaining. Moreover, meaning making in the aftermath of trauma may assist with better understanding one’s experience and their place in the world.

Vis and Boynton (

2008) contended that these areas can be linked with spirituality for many individuals and that it is important for practitioners to consider spirituality as an extension of these frameworks and to engage in a spiritually sensitive approach in trauma practice.

In recent scholarship,

Eames and O’Connor (

2022) found that spirituality was a significant moderator between deliberate rumination and PTG in a study of 96 participants who were predominantly white women aged 19–59 and who had experienced a traumatic event after age 16. They conveyed that engagement in active deliberate rumination requires effort and cognitive processing in integrating trauma information into pre-existing core beliefs and frameworks. However, this is apparent for those whose spirituality, spiritual beliefs and supportive communities appear to be more solid and nurturing. Conversely, when spirituality is interconnected as part of the source of the trauma, the lack of support, connection, and cognitive heuristics involved in the reconstruction processes of a crumbling spiritual worldview and an inability to discuss aspects with a safe community can feel deeply disturbing, isolating, and traumatic for individuals, as discussed by the women in this study. SD and meaning-making capacity appear to be intertwined, furthering the complexity of the issue.

2. Methods

The study employed

Smith et al.’s (

2009) IPA approach to analyze the data for this qualitative inquiry. IPA was selected as an approach as it explores how people make meaning of life experiences while providing insight into the richness and mystery of our lives (

Smith et al. 2009). While the researcher’s interpretation is appreciated and seen as unavoidable at every stage, an IPA approach commits to grounding these interpretations in the participants’ accounts (

Larkin and Thompson 2011). The research was informed by

Yardley’s (

2000) principles for assessing qualitative research: sensitivity to context, commitment and rigor, transparency and coherence, and impact and importance. Ethics was attained by the University of Calgary Research Ethics Board.

Participants were recruited using snowball sampling through contacts from the EC community in a region in Canada (

Creswell and Poth 2016). Purposive criterion sampling was followed, as suggested by

Smith et al. (

2009) for IPA research. Individuals who were interested in participating in an interview contacted the researcher via email or telephone to schedule a screening call. Following the call, interested participants were able to provide informed consent to participate in the interview. Four women of EC backgrounds (see

Table 1) participated in in-depth, 60–90-min, semi-structured interviews that took place over Zoom. All participants identified as women, and provided their preferred pronouns: Eva, she/her; Eliza, she/her; Anna, she/her; and Gwen, they/them.

IPA data analysis encourages researchers to remain immersed in the transcript and to stay close to the lived world described by the participant (

Smith et al. 2009). It is important to maintain the interpretative goal, which differentiates the process from thematic analysis (

Smith et al. 2009). The following steps were followed to complete the analysis: firstly, initial exploratory coding included close attention to each comment and associated body language; and secondly, noting of descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual reflections that arose through this process. Experiential statements were then developed by gradually gathering patterns present in the initial line-by-line exploratory coding. For example, the experiential statement “existential struggle of living with suffering” in Anna’s interview was created by reflecting on the broader concept present in a section of descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual coding. This included descriptive lines such as “disturbing to think that what is currently happening is all there is” and “recognizing that there is nothing else”, as well as the conceptual code “coming to terms with existential responsibility of being here”.

More interpretative, abstract ideas that emerged through dwelling on participants’ words and themes were collapsed and clustered (

Larkin and Thompson 2011). This led to the development of personal experiential themes (PETs) (

Smith and Nizza 2021), a list of overarching themes for a single transcript. To aid the development of PETs, the first author focused on each emergent theme and accompanying key quotations and used a large bulletin board to visually map higher-order themes. The process was repeated with the other participants’ transcripts. Discussion with all authors on emerging themes, connections, tensions, and distinctions aided with analysis.

In keeping with the phenomenological attitude, it was important for the phenomenon to emerge organically from the data. This process resulted in a provisional map of key thematic findings.

Smith et al. (

2009) asserted that analysis is an iterative process and continues as the researcher writes up the findings. Writing the results offered the opportunity to iteratively refine understandings of the phenomenon.

Population Background: Evangelical Christianity

Each person affiliated with EC may define their faith in a unique way. For this contained article, we present information on EC gleaned from the literature. EC is a branch of Protestant Christianity that, as defined by

Bebbington (

2003), places strong emphasis on personal salvation through Jesus, the authority of the Bible, evangelizing to non-believers, and active expression of one’s faith in the world. Evangelical churches generally uphold conservative perspectives on gender and sexuality (

Gallagher 2003). This includes teachings on God-ordained differences between men and women, validation for men’s “headship” in all institutions, and the subsequent doctrine of submission wherein women take a subservient role to men (

Bendroth 1993). Recently, EC subculture and institutions have faced heightened and ongoing cultural critiques regarding racism, homophobia, and sexual abuse (see for example,

Natarajan et al. 2022;

McKinzie and Richards 2022).

In a recent mixed methods study,

Lloyd and Hutchinson (

2022) surveyed 446 self-identified EC participants, inquiring as to how they experienced mental distress in relation to their church community. 293 of the 446 surveyed responded. Most respondents were in the United Kingdom (87%) and female (75%). Through reflexive thematic analysis they revealed the following five themes: (1) Tensions between Faith and Suffering; (2) Cautions about a Reductive Spiritualization; (3) Feeling Othered and Disconnected; (4) Faith as Alleviating Distress; and (5) Inviting an Integrationist Position. They found that mental distress was linked to spiritual deficiency, such as adopting a view of deep moral, spiritual, and personal failure, which was invalidating and dismissive of concerns. They stated that stigma could create problems for help seeking in secular settings.

Lloyd and Hutchinson’s (

2022) recent study, along with our study, demonstrate the significance of spiritual concerns for those of evangelical backgrounds. Clinicians can benefit from an increased understanding of how those from evangelical communities, and those of other faith traditions, experience SD.

3. Results

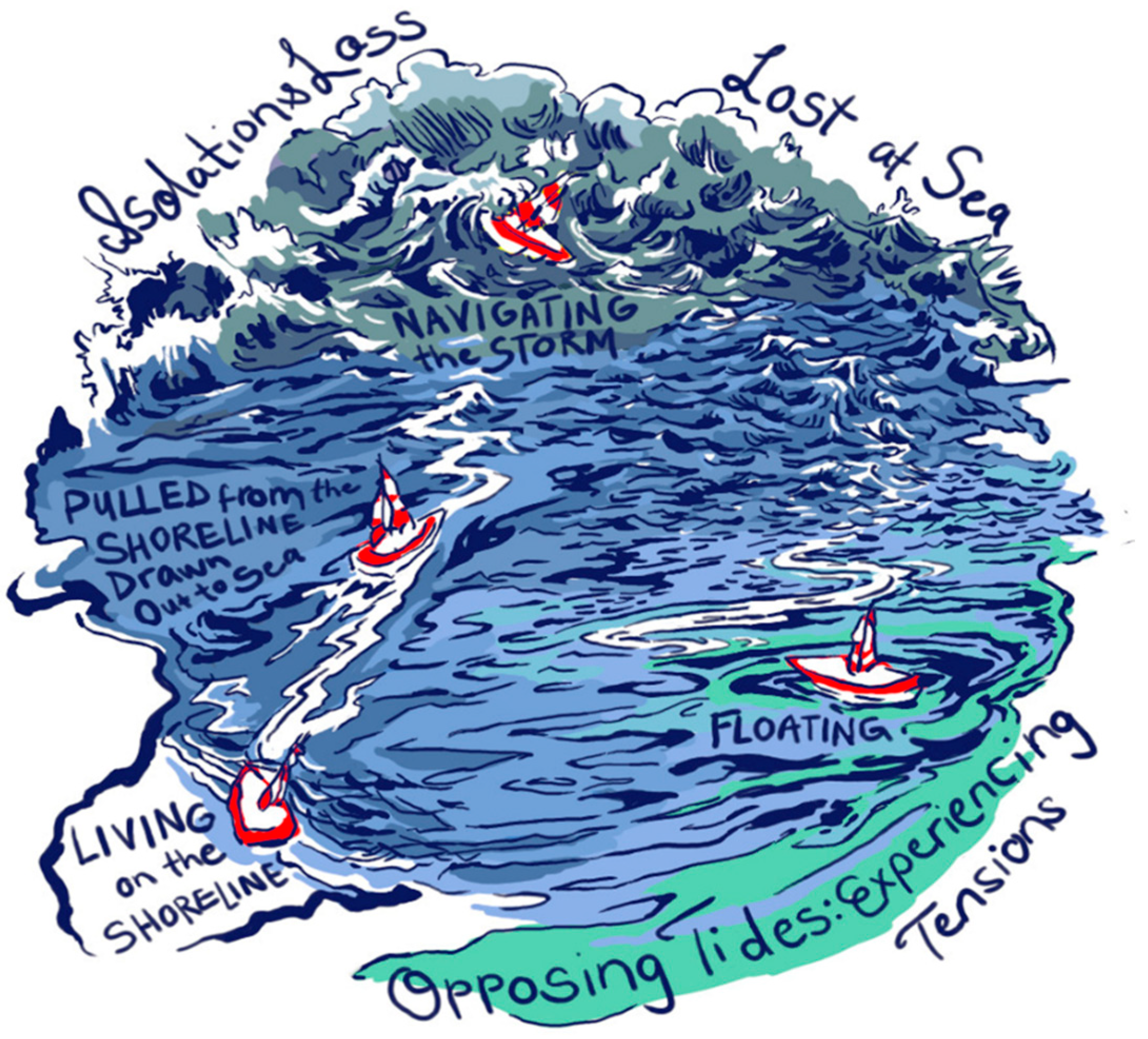

The participants each described their SD journeys as wrought with tensions and paradoxes that they have navigated and continue to navigate in their ongoing processes towards finding a more spacious spirituality in deeper congruence with their values. This IPA study explored the phenomenon of SD and highlighted voices of lived experience in the hope of strengthening understanding. Through semi-structured interviews with four women of EC backgrounds, conducted over Zoom due to the COVID-19 pandemic, narratives of spiritual wrestling unfolded. The women described their SD narratives as a process, depicted through a non-linear, ocean-themed metaphor (

Figure 1). The process included at-times traumatic existential and relational storms, as the women felt pulled from the stability of the familiar EC shoreline into the untethered waves of the unknown. A sense of existential tension, or opposing tides, as well as isolation and loss were identified as ebbing and flowing undercurrents throughout their SD journeys.

Alongside discussions of trauma, each of the women evoked an emerging sense of expansion, curiosity, and self-authorship. They were pulled towards a more “spacious spirituality” that could hold their in-flux worldviews as they tussled with major existential questions. Their journeys involved an ongoing pull towards an inner compass of authenticity and values congruence, even at the expense of social and existential security. This turbulent experience appeared to be in the service of building a more nourishing, spacious spirituality that could contain the complexity of life and align with their integrity. These findings are congruent with much of the literature on resilience, PTG, and R/S.

The above model (

Figure 1) outlines the four phases of the SD journey as conveyed by the participants. Opposing Tides and Isolation and Loss were undercurrents that flowed throughout the experience. The women began on the familiar shoreline of their EC communities but gradually found this too rigid and containing and were pulled from the shoreline towards a more authentic, congruent way of being, although this came with existential tumult. They had to navigate the storm of acute, disorienting spiritual and existential unrest and questioning. This phase will be further exposed in the following section. Finally, the women all reported finding some sense of floating as they gradually made sense of their unfinished, expanding spiritual worldview. This phase will also be considered in our conversation on posttraumatic growth.

3.1. Navigating the Storm: Wounding and Trauma in the SD Journey

“Darkness. It comes…like, you start in this like, light and beautiful and connective place and you just move into loneliness and darkness.”

—Anna

The women described being drawn from the supposed safety and belonging found on the shore of their EC foundation and community into an ocean of uncertainty, unknown depths, and tumultuous storms of SD. They expressed a sense of disorientation as they desperately tried to navigate these uncertain waters while asking themselves: will we ever feel ground again? Simultaneously, they recognized that they could not go back to the shoreline unchanged. This emotional pain was likened to darkness.

Being drawn into the ocean and navigating distress due to spiritual struggles brings inner pain, including a profound sense of existential disorientation, as the containing but organized worldview of the shoreline fades into the distance. As Anna asked, how does one “be” in this new landscape? Anna wrestled with the unfolding loss of her EC worldview, which plunged her into a “meaningless and disorienting” space. She confronted “the garbage that is. What is currently happening”. She goes on: “Part of losing your faith is just like sitting in the shitty world that is around us…that’s like part of it, is determining like, how do you live right now when there’s nothing else than just right now?” Facing the “garbage” of reality without the guidance of an organizing faith appeared deeply anxiety-provoking and spun off further existential quandaries. Anna was plunged into a whirlpool of questions and grasped at sources of comfort and guidance amidst the crashing waves.

Eva shared this angst of disorientation, alongside a longing for spiritual meaning making guidance in the uncertain waters:

And you have to navigate all of those things and everybody’s telling you a different answer and you just, you just want instructions and there aren’t any or there’s too many or they contradict each other, and so you just want to be good, both in like, this moral sense but also like in the sense of like, everything’s okay. And you just can’t.

As she was pulled out to sea, she lost a sense of reliable certainty and struggled to find a place to moor herself amid contradicting perspectives. A sense of her own inner compass was absent, obscured by the tossing waves, as she grasped for some external source of structure to steady her boat. As the solid ground of the well-lit shore was shrouded by dark storm clouds and undulating waves, many of the participants’ relationships which were once nourished by the shoreline shifted, faced challenges, or were lost.

For Gwen, the most burdensome element of their SD was found in the space of relational wounding: “It’s definitely relationships, I think the things that hurt me most right now is still the relationships I’ve lost and the way other Christians see me”. Gwen had always been avidly involved in Christian community, service, and leadership. Gwen was removed from a key component of church leadership because of their evolving beliefs, an experience which had a visceral embodied impact on Gwen—it “broke” their heart: “My heart broke when I wasn’t allowed to pray with the youth anymore. It was such an important part of my life, of their lives, and to be banned from the prayer room…[Laughs]”. Gwen chuckled at their banishment from the “prayer room” because of their shifting worldview. However, the wounding of this cut belonging was disorienting and spun Gwen into their own whirlpool of questions and fears. After moving to a new city, Gwen continued to struggle, feeling that “I was never going to fit into church. And even with other Christians”.

Gwen was distinct in this study for their strong emphasis on relationships, particularly their intimate relationship with God. Their concern about harming this relationship as they drifted from the shoreline catalyzed a sense of fear and disorientation for Gwen. Still, Gwen found that exploring beliefs and practices outside of traditional EC “wouldn’t separate me from God…there’s nothing I can do to separate me from God, I guess”. Gwen’s strong connection with God supported they in places of containment, uncertainty, and isolation that pervade the SD journey. Although Gwen was immersed in the crashing waves of the existential unknown, they had found a lighthouse, some sense of buoyancy within the rising waves. Divine refuge could be found within the tumult.

Although Gwen had found some peace in the uncertainty, they, like Eliza and Eva, continue to make meaning of their SD journey through the language of trauma. When describing their SD experience, Gwen stated: “It’s very traumatic and also very segregating and polarizing…”

From the start of her interview, Eva expressed the traumatizing nature of her SD experience. A particular situation exemplified Eva’s spiritual trauma. Eva shared about attending a family-obligated church event after having taken space from EC environments for some time. This experience brought on a “physical, visceral” response. She described “putting on her armour” before the event—showing off her tattoos and wearing bold lipstick: “this can’t touch me in the same way”. Still, being in a church setting and hearing a sermon plunged her into a distressing (and conceivably dissociative) experience:

Just sitting there and being like, I just have to get through this. I sort of…go completely inward and like, just have, like my toe tapping madly to get through…I’ve blocked the rest of it out, I barely remember going in and going out, any of that, I just really remember sitting there and being completely stuck.

Reflecting on this experience after several years of distance, Eva acknowledged,

Trauma is something that’s like, the thing from the past that is like, drawn into the present…like this thing from a long time ago never actually went away and maybe it never will. That feeling. Like, “oh I’m just stuck in this and I always will be”.

This sense of “stuckness” appears to be part of the sense of containment of the EC tradition conveyed by participants. Even within the vastness and expansion of the wild ocean, stuckness may remain—a seemingly unshakeable tether may bind and continue to limit. Eva described a sense of fear that she will always feel trapped in both the crashing of uncertain waves and the chains of containment.

In exploring what it was like to share this painful memory, Eva described the echo and response of emotional memory:

I can definitely like, feel almost some of the milder versions of that come up, and I know that happens when I tell the story, when I re-enter those spaces, like, the echoes of that are still there…I’m charged up a little bit and I always am when I tell a story like that.

Participants described the need to deconstruct and sort through emotional baggage from their EC upbringings and illuminated a fear of being stuck in the acute storm of SD. Eliza emphasized the significance of “sorting through” and “uncovering” unaddressed pain, a process which in and of itself was overwhelming and isolating. The language of trauma and describing it appeared to allow the participants to make meaning of these disorienting, overwhelming, and distressing emotional and embodied experiences within their SD journeys.

3.2. “You’re Just in a Wave Right Now”: Cultivating Spaciousness

“When there’s a tragic or chaotic situation happening, there are calm waters on the other side, but you’re just in a wave right now. So just wait. And one day you’ll make peace. You’ll be on the other side. It’ll be calm.”

—Anna

Alongside their traumatic experiences, each of the participants expressed the presence of healing and expansion. Sharing about their emergence from the darkness seemed important to the women. As participants learned to ride the waves of SD and calmer waters appeared, they seemed to find lighthouses, anchors, and life buoys, places of steadiness where they could cultivate more congruent and spacious spiritual selves. In the above quote, Anna described the acute intensity of SD as temporary, a wave to be ridden, until calmer, more tenable waters appeared. Her words conveyed a sense of trust in the rise and fall of the waves, a process that must be traversed before calm seas are found. The expansive process the women described from containment to deeper value congruence can be likened to a metamorphosis or rebirthing in what Eva termed “emerging as a person”. The pull from the shoreline into the uncertain seas appeared to be in service of a worthwhile existential task of claiming one’s identity, values, and authenticity on one’s own terms.

Gwen expressed the embodied sense of this process: “I’m expanding, I am definitely expanding and you know, from what I used to be”. Their words demonstrated a gradual shift from a felt sense of containment to one of vaster, spacious expansion. Eliza described her journey leading her to body-based healing modalities, which facilitated a sense that “your whole life is an integrated whole”—body, mind, and spirit.

Eliza’s ongoing commitment to inner growth and the exploration of self and her relationships was emphasized throughout her SD journey. She expressed, “I’m very much in the process of know thyself”. As she processed wounds from childhood and EC, she found she was “defrosting” her connection to self and others. Eliza was also navigating a connection to the divine aligned with her evolving values and fostering wonder, curiosity, and humility about life’s big questions despite the potential judgment of conventional EC doctrine. For her, “as long as I’m content with my walk with God, then that’s the judgment I’ll go for”. She appeared to be exploring a less-contained, nourishing spirituality.

Eva, too, was navigating a connection to sacredness in her own unique way. She was finding ways to engage with various religious traditions “with dignity” while addressing the ways in which religions can be “hugely problematic”.

I think it’s just hopeful to see like, okay, it’s possible. And it doesn’t solve all the problems [of Christianity], it doesn’t make everything go away, but there’s something to faith traditions, even if I don’t want to, or can’t be a part of one in the way that I was growing up, that I can actually respect and still learn from and still have a part of my life. So, it’s a work in progress.

Like Eva, Gwen was releasing confining images of faith and the Divine, and sinking into curiosity and not-knowing as part of their spirituality:

I used to just have…like an image of what God looks like, and it’s always that children’s Bible star in the sky, or like…it was almost like the silhouette of Jesus, like, long hair but it was this bright light, whenever I prayed I just pictured that bright light with a Jesus silhouette and…When I pray, I don’t even try to picture who God is anymore. Because I find that is really confining who God is too. And like, I’m just trying to learn different ways of how God presents you know. Yeah, so I think I’m just on this journey of trying to discover more of like, who God is that, yeah that’s different from the way I always pictured.

Releasing confining images of God and the EC doctrine of proselytization has offered further spaciousness for Gwen’s relationships.

It’s just so cool to just finally like, [sighs] build genuine relationships, without this secret agenda of having to minister to them or something…Just loving them for their beliefs and even learning from them. But not thinking secretly they need Jesus [Laughs].

Gwen’s profound dedication to meaningful relationships with the divine and fellow humans and the re-imagining process seemed to offer a spacious softening into a more congruent way of being.

For each of the participants, this spaciousness breathes in and out, ebbs and flows, like the rhythmic flow of the ocean’s waves, expanding, revitalizing. Still, this reclamation of a nourishing spirituality does not appear to be a simple process, but rather holds undercurrents of tensions and uncertainties that the participants continue to navigate.

Although Gwen cherished their growth and expansion, they also lamented the loss of EC’s simplicity:

There was a simplicity to [EC], like, you just had to believe in Jesus and life is good. But outside of that world it’s like, there are so many complexities and layers to life, which…but this is the real world.

“This is the real world”. Once participants left the shore, they contended with a world that they experienced as more complex but more real. The realizations they faced could not be contained in the framework provided by the EC shoreline. They had to navigate acute inner storms of existential disorientation and relational wounding and then move through a reconstruction process akin to moving out of a dark night of the soul towards a renewed sense of being. They began to re-cultivate a spirituality spacious enough to hold nuances and diversity, yet this cultivation remains ongoing, unfinished, and expanding. Although the women found they were floating in calmer waters, their tethers to the shoreline remained varied and in flux.

4. Discussion and Implications

This study evidences the tender and isolating complexity of the SD experience. For the women, spirituality served both as a cause and perpetuator of trauma and as a vehicle for transcendent meaning making in response to wounding. Ultimately, spirituality is tangled in the women’s distress while also playing a role in their PTG process. This undeniable tension was voiced by participants, illuminated through an embodied sense of “push-pull” or “opposing tides” that permeated their experience. Although the women navigated the SD journey in isolation, PTG was notable in their stories, particularly in the areas of relating to others, authenticity, values congruence, appreciating life, and spiritual spaciousness.

Echoing the extant literature on spiritual struggle and faith disaffiliation (

Rockenbach et al. 2012;

Lee and Gubi 2019), a consistent experience of cognitive dissonance (CD) is woven throughout the women’s SD journeys. CD refers to a state of mental discomfort that occurs when a person holds “beliefs, opinions, values etc., which are inconsistent, or which conflict with an aspect of his or her behaviour” (

Oxford Languages n.d.).

Winell’s (

2006) theorizing about religious trauma syndrome highlighted CD and accompanying identity confusion as central issues provoking religious trauma. In addition,

Lee and Gubi’s (

2019) IPA study with six participants of multiple genders examined conversion from Christianity to atheism and found that a key underlying reason for religious conversion is CD. Their study noted that, for some participants, deconversion can be “unwanted and resisted” (p. 174), not unlike the embodied sense of opposing tides experienced by Anna, Gwen, Eva, and Eliza.

Knight et al. (

2019) articulated that shifting towards disaffiliation, or, in the words of this study, moving away from the shoreline, can help resolve one’s CD.

Along similar lines,

Gillette (

2016) considered the spiritual tensions of seven women who left Protestant fundamentalism, noting that while staying in fundamentalist Christianity was not viable for participants, leaving their faith was also painful. Citing depth psychologist

Jung’s (

[1958] 2002) thinking,

Gillette (

2016) suggested that “growing consciousness of the polarized nature of the self brings with it significant freedom, and also tension” (p. 117). Her participants, like the four women in this study, found themselves torn between pressures or pulled between opposing tides. Recognizing their inner dissonance required them to ask central questions about what they believed and how this informed their way of being in the world. These questions, as

Jung (

[1958] 2002) contended, while liberating, bring tension as individuals acknowledge what they may lose.

Perhaps most evocative in the study results is the participants’ use of the word “trauma” to describe SD’s profound impact on wellbeing. Although there is considerable social work literature that has considered trauma in general (see for example,

Levenson 2017;

Knight et al. 2019), explorations of religious and/or spiritual trauma are limited. This significant descriptor, trauma, is not evidently present in the quantitative body of spiritual struggle studies (see for example,

Abu-Raiya et al. 2015,

2016;

Wilt et al. 2021). It is the growing qualitative literature on spiritual struggle, as well as the grey literature, that continues to affirm the potentially traumatic nature of spiritual challenges.

Gillette (

2016),

Smull (

2000), and

Fazzino (

2014) all presented findings that Christian settings can have traumatizing impacts. The findings of this study are certainly congruent with these studies.

Trauma therapist Brian Peck, co-founder of the online Religious Trauma Institute and creator of the Room to Thrive Instagram account, shared that “religious trauma can result from an event your nervous system experienced as an inescapable attack within a religious context” (

Room to Thrive 2022). The trauma scholarship affirms the impact of feeling “stuck” on one’s nervous system (

Heller and Heller 2004;

Levine 1997;

Rothschild 2000). When escape is experienced as impossible, the body may sense that death is imminent and utilize a “freeze” response (

Rothschild 2000). Inescapable threats to the nervous system could involve being exposed to threatening religious messages in a setting where one felt they could not escape, such as a church service. Experiences or beliefs that felt threatening, but which also were deemed compulsory, could be experienced by the body as an inescapable threat, and be remembered and even re-experienced in the body as traumatic. Eva’s feeling of being “frozen” in a family-obligated church event, for instance, highlights the distress of being in a psychologically unsafe environment. Eva also shared about the need to prepare for sharing her story. Her SD journey could be drawn into the present, just as trauma is stored in the body and may continue to visit long after a threatening event has passed (

Van der Kolk 2014).

A trauma-informed practice (TIP) approach remains attuned to the potential influence of traumatic experiences on a person’s current presentation, and practitioners strive to create safe environments, emphasizing safety, trust, collaboration, choice, and empowerment (

Levenson 2017).

Boynton and Margolin (

2023a,

2023b) argued that current TIP approaches do not include the aspects of trauma that are interconnected with spirituality, love, meaning making, hope, and transcendence, which are central to healing and the integrated nature of mind, body, and spirit. They extended

Carello and Butler’s (

2016) work to embrace the spiritual dimension in their spiritual practice model (

Boynton and Margolin 2023a) as well as in their spiritually informed pedagogy (

Boynton and Margolin 2023b).

Vis and Boynton (

2008) conveyed how trauma is a spiritual experience involving spiritual rumination. They argued that spirituality is a pivotal aspect of coping, re-evaluating, and reconstructing one’s worldview through transcendent meaning making. They contended that posttraumatic growth and attending to spirituality can foster new ways of being post-trauma for individuals, and as such further research was required. This study addresses this call, and these aspects are evident in the women’s stories. Still, the participants navigated the storms in isolation, which speaks to a greater need for advocacy, clinical awareness, and the reduction of stigma. The TIP approach is strengthened through spiritual sensitivity and is necessary in working with those who are navigating the storms of an SD journey.

Canda et al. (

2020) asserted that a spiritually sensitive practice approach includes creating a space with opportunities to share about the spiritual, religious, and cultural elements of one’s lived experience. This includes creating spiritual safety, attunement to spiritual needs, spiritually informed and appropriate interventions, and ongoing evaluation (

Boynton and Margolin 2023a;

Boynton and De Vynck 2022). Practitioners and educators can actively inquire about individuals’ and students’ R/S backgrounds, worldviews, and values and demonstrate efforts to understand. In our agencies, we can advocate for policies and procedures that integrate R/S questions in assessments and treatment, and further training and supervision opportunities in this area of practice.

As psychologist

Fosha (

2021) has upheld, connecting with another can be in service of “undoing aloneness” (p. 1). As SD is often an experience of private suffering, practitioners have an opportunity to gently accompany people on their path and, in so doing, nurture posttraumatic growth. Alongside the wounds we carry, we also have an innate motivation and capacity to grow, heal, and “self-right” (

Fosha 2021, p. 28), and practitioners can attend to and mirror back these glimmers of resilience and PTG within the therapeutic relationship.

The findings call on practitioners to forgo assumptions, reduce stigma, and create safety and space to support those suffering from a posture of presence and humble curiosity. Given the variations in experiences, practitioners can creatively co-create therapeutic paths with each person dependent on the particularities of their SD journey. Reducing stigma and creating awareness of support for SD is needed. Practitioners should heed caution with referrals to spiritual clergy where SD may be reinforced. Referrals to those who can support SD in a non-judgmental manner are required. Social workers are well-positioned to be trained and supportive of those experiencing SD and could facilitate PTG through transcendent meaning making processes and nurturing support.

Practitioners should be aware of the embodied trauma responses of SD and the need for grounding while encouraging individuals in the process of spiritual rumination, transcendent meaning making, and values exploration. They can bear witness as individuals navigate the shoreline, the opposing tides, the isolation, the storms, and the floating and honour the paradoxes of their human experience without offering easy answers. SD is an individual subjective experience, not to be constrained or simplified but rather to be witnessed. Congruent with the contentions of

Vis and Boynton (

2008), we recommend that practitioners raft up alongside people journeying through the ever-evolving transcendent meaning-making process of SD and facilitate posttraumatic growth.

5. Conclusions

This article has outlined the tensions of SD as graciously described by the participants. During their SD journeys, participants faced relational losses and challenges with the divine, family, friends, and community and reconfigured their spiritual relationships. They encountered existential insecurity and wrestled in isolation, reckoning with the call for deeper spaciousness. They struggled with traumatic experiences within EC, the trauma of being pulled from the shore, and ongoing “echoes” of painful memories. These findings have validated a small but emerging body of scholarship on SD and the traumatic impacts of R/S, which have been discussed in popular culture and the grey literature for some time. Still, although wounding, the women’s tumultuous journeys appeared to pull them towards an inner compass of greater congruence and personal strength, authenticity, and expansiveness. This process can be understood through the domains of PTG, which highlights the capacity of individuals experiencing SD to make meaning, integrate painful truths into an expanding worldview, and cultivate spirituality through a trauma experience. Practitioners supporting individuals with SD can uphold a spiritually sensitive, trauma-informed practice approach. They can honor the complexity of each person’s story, offer grounding and connecting anchors in the storm, mirror back glimmers of resilience, growth, space, and hope, and, most importantly, bear compassionate witness to the SD journey from a place of love.