Interpretation of Funerary Spaces in Roman Times: Insights from a Nucleus of Braga, NW Iberian Peninsula

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Archeological Setting: Bracara Augusta, Necropolises, Religious Buildings, and Sanctuaries

3. The Main Phases of the Necropolis Occupation

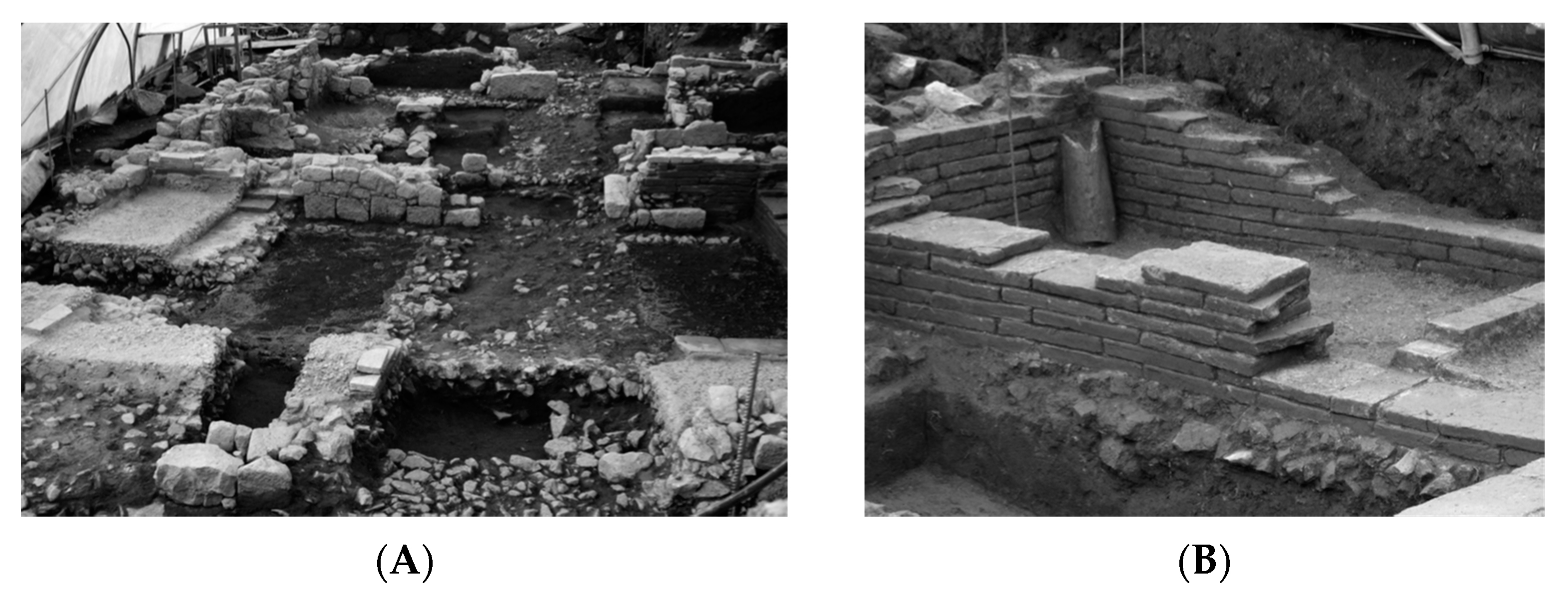

4. The Constructive Process of the N.A.2 in the Necropolis

4.1. The Main Phases of Occupation

4.1.1. Phase I

4.1.2. Phase II

4.1.3. Phase III

4.2. Description of the Building (Architecture and Materials)

4.3. The Function of N.A.2

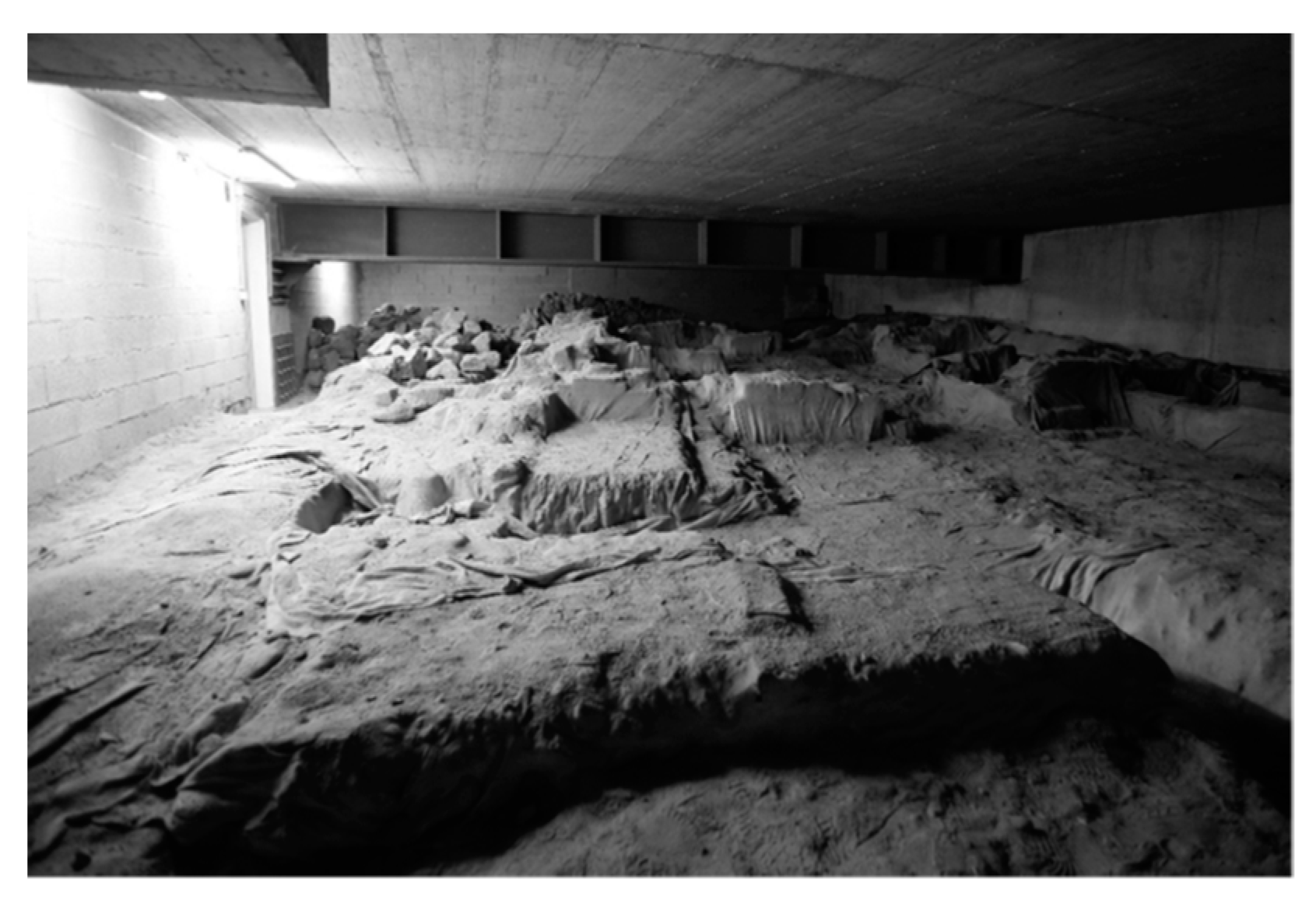

4.4. The Musealization Project of the N.A.2

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Braga, Cristina. 2018. Morte, Memória e Identidade: Uma Análise das práticas Funerárias de Bracara Augusta (Death, Memory and Identity: Analyses of Funerary Practices in Bracara Augusta). Ph.D. thesis, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1822/59044 (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Braga, Cristina, and Manuela Martins. 2015. Bracara Augusta: Rituais e espaços funerários (Bracara Augusta: Rituals and funerary spaces). Férvedes 8: 301–10. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Helena, José de Encarnação, Manuela Martins, and Armandino Cunha. 2006. Altar romano encontrado em Braga (Roman altar found in Braga). Forum 40: 31–41. Available online: http://hdl.handle.netI1822/9250 (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- de Sande Lemos, Francisco. 2002. Bracara Augusta—A grande plataforma viária do Noroeste da Hispania. Forum 31: 95–127. Available online: https://revistas.uminho.pt/index.php/forum/article/view/2240/2388 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- do Carmo Ribeiro, Maria. 2008. Braga Entre a época Romana e a Idade Moderna. Uma Metodologia de Análise para a Leitura da Evolução do Espaço Urbano (Braga between Roman Times and Modern Age. An Analysis Methodology for Reading the Evolution of Urban Landscape). Ph.D. thesis, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1822/8113 (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Fragata, Ana, Carla Candeias, Jorge Ribeiro, Cristina Braga, Luis Fontes, Ana Velosa, and Fernando Rocha. 2021. Archaeological and Chemical Investigation on Mortars and Bricks from a Necropolis in Braga, Northwest of Portugal, Braga, Portugal. Materials 14: 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido Elena, Ana, Ricardo Mar, and Manuela Martins. 2008. A Fonte do Ídolo: Análise, interpretação e reconstituição do santuário. In Bracara Augusta—Escavaçoes Arqueologicas 4. Braga: Unidade de Arqueologia da Universidade do Minho. 73p. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, Patrick. 1994. Bracara Augusta: Ville latine (Bracara Augusta: Latin city). Trabalhos de Antropologia e Etnologia 34: 229–41. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Manuela. 2014. Projeto de Bracara Augusta: 38 Anos de Descoberta e Estudo de Uma Cidade Romana. Ciências e Técnicas do Património XIII: 159–69. Available online: https://ler.letras.up.pt/uploads/ficheiros/12988.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Martins, Manuela, and Helena Carvalho. 2010. Bracara Augusta and the changing rural landscape. In Changing Landscapes: The impact of Roman towns in the Western Mediterranean. Paper presented at the International Colloquium, Castelo de Vide—Marvão, Portugal, 15–17 May 2008. Edited by Cristina Corsi and Frank Vermeulen. Bologna: Ante Quem, pp. 281–98. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Manuela, and Helena Carvalho. 2017. Roman city of Bracara Augusta (Hispania Citerior Tarraconensis): Urbanism and territory occupation. Agri Centuriati: An International Journal of Landscape Archaeology 14: 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Manuela, and Manuela Delgado. 1989–1990. As necrópoles de Bracara Augusta. Cadernos de Arqueologia série II 6–7: 41–187. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Manuela, and Maria do Carmo Ribeiro. 2012. Gestão e uso da água em Bracara Augusta: Uma abordagem preliminar. In Caminhos da Água, Paisagens e usos na longa duração. Edited by Manuela Martins, Isabel Vaz de Freitas and Maria Isabel Del Val Valdivieso. Porto: CITCEM, pp. 9–52. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Manuela, Cristina Braga, Fernanda Magalhães, and Jorge Ribeiro. 2020. Constructing identities within the periphery of the Roman Empire: North-west Hispania. In Rome and Barbaricum. Contributions to the I Colóquio Internacional Evolução da Paisagem Urbana: Economia e Sociedade, Braga, Portugal, Archaeology and History of Interaction in European Protohistory. Edited by Roxana-Gabriela Curcă, Alexander Rubel, Robin Symonds and Hans-Ulrich Voß. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 135–54. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Manuela, Jorge Ribeiro, Fernanda Magalhães, and Cristina Braga. 2012a. Urbanismo e arquitetura de Bracara Augusta. Sociedade, economia e lazer. In Evolução da paisagem Urbana. Sociedade e Economia. Paper presented at I Colóquio Internacional Evolução da Paisagem Urbana: Economia e Sociedade, Braga, Portugal, May 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Manuela, José Meireles, Maria do Carmo Ribeiro, Fernanda Magalhães, and Cristina Braga. 2012b. The water in the city of Braga from Roman Times to the Modern Age. In Water shapes. Strategie di valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale legato all’acqua. Edited by Heleni Porfyriou and Laura Genovese. Roma: Palombi Editori, pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Manuela, Luís Fontes, Cristina Braga, José Braga, Fernanda Magalhães, and José Sendas. 2010. Salvamento de Bracara Augusta. Quarteirão dos CTT (BRA 08–09 CTT). Final Report, Archaeological works of U.A.U.M./Memórias, N.° 1. p. 1313. Available online: https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/handle/1822/10141 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Morais, Rui. 2009. Self-Sufficiency and Trade in Bracara Augusta during the Early Empire. A Contribution to the Economic Study of the City. Oxford: BAR Publishing, p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, Rui. 2009–2010. Uma mulher singular em Bracara Augusta. Forum 44–45: 121–33. Available online: https://revistas.uminho.pt/index.php/forum/article/download/1909/2073/2298 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Morais, Rui. 2010. Bracara Augusta. Braga: Edição da Câmara Municipal de Braga, p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, Rui, Adolfo Fernández Fernández, and Cristina Braga. 2013a. Contextos cerámicos de la transición de Era y de la primera mitad del s. I provenientes de la necrópolis de la Vía XVII de Bracara Augusta (Braga, Portugal). Paper presented at Congrès International de D’Amiens—SFECAG, Amiens, France, May 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, Rui, Miguel Bandeira, and Eliana Pinho. 2013b. Itineraria Sacra. Bracara Augusta Fidelis et Antica. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, Jorge. 2013. Arquitectura romana em Bracara Augusta. Uma análise das técnicas edilícias. Porto: Afrontamento, p. 684. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, Jorge. 2018. Reflexões em torno da monumentalidade de Bracara Augusta a partir de um conjunto de elementos arquitetónicos de grande dimensão. In Usos do espaço no mundo antigo. Edited by Gilvan Ventura Silva, Érica Cristhyane Morais da Silva and Belchior Monteiro Lima Neto. Vitória: GM Editora, pp. 130–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Colmenero, Antonio. 1996. Integración administrativa del Noroeste peninsular en las estructuras romanas. In Lucus Augusti I. El amanhecer de uma ciudad. Edited by Antonio Rodríguez Colmenero. A Coruña: Fundación Pedro Barrié de la Maza, pp. 301–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tranoy, Alain. 1981. La Galice Romaine—Recherches sur le nord-ouest de la péninsule ibérique dans l’Antiquité. Paris: Diffusion de Boccard, p. 601. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz, Filipe, Cristina Braga, João Tereso, Cláudia Oliveira, Lara Gonzalez Carretero, Cleia Detry, Bruno Marcos, Luis Fontes, and Manuela Martins. 2021. Food for the dead, fuel for the pyre: Symbolism and function of plant remains in provincial Roman cremation rituals in the necropolis of Bracara Augusta (NW Iberia). Quaternary International 593–94: 372–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villedary y Mariñas, Ana Maria, and Verónica Gómez Fernández. 2010. Captación y uso del agua en contextos funerarios y rituales. Estructuras hidráulicas en la necrópolis de Cádiz (siglos III a.C.—I d.C.). In Aqvam perdvcendam curavit: Captación, uso y administración del agua en las ciudades de la Bética y el Occidente romano. Edited by Lázaro Lagóstena Barrios, José Luis Cañizar Palacios and Lluís Pons Pujol. Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz, pp. 511–32. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1449580/Captaci%C3%B3n_y_uso_del_agua_en_contextos_funerarios_y_rituales._Estructuras_hidr%C3%A1ulicas_en_la_necr%C3%B3polis_de_C%C3%A1diz_2010_ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Braga, C.; Ribeiro, J.; Fontes, L.; Fragata, A. Interpretation of Funerary Spaces in Roman Times: Insights from a Nucleus of Braga, NW Iberian Peninsula. Religions 2023, 14, 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091185

Braga C, Ribeiro J, Fontes L, Fragata A. Interpretation of Funerary Spaces in Roman Times: Insights from a Nucleus of Braga, NW Iberian Peninsula. Religions. 2023; 14(9):1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091185

Chicago/Turabian StyleBraga, Cristina, Jorge Ribeiro, Luis Fontes, and Ana Fragata. 2023. "Interpretation of Funerary Spaces in Roman Times: Insights from a Nucleus of Braga, NW Iberian Peninsula" Religions 14, no. 9: 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091185

APA StyleBraga, C., Ribeiro, J., Fontes, L., & Fragata, A. (2023). Interpretation of Funerary Spaces in Roman Times: Insights from a Nucleus of Braga, NW Iberian Peninsula. Religions, 14(9), 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091185