Does God Comfort You When You Are Sad? Religious Diversity in Children’s Attribution of Positive and Negative Traits to God

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Positive and Negative Views of God in Childhood

1.2. Religious Diversity in Early Concepts of God

1.3. Current Study

2. Results

3. Discussion

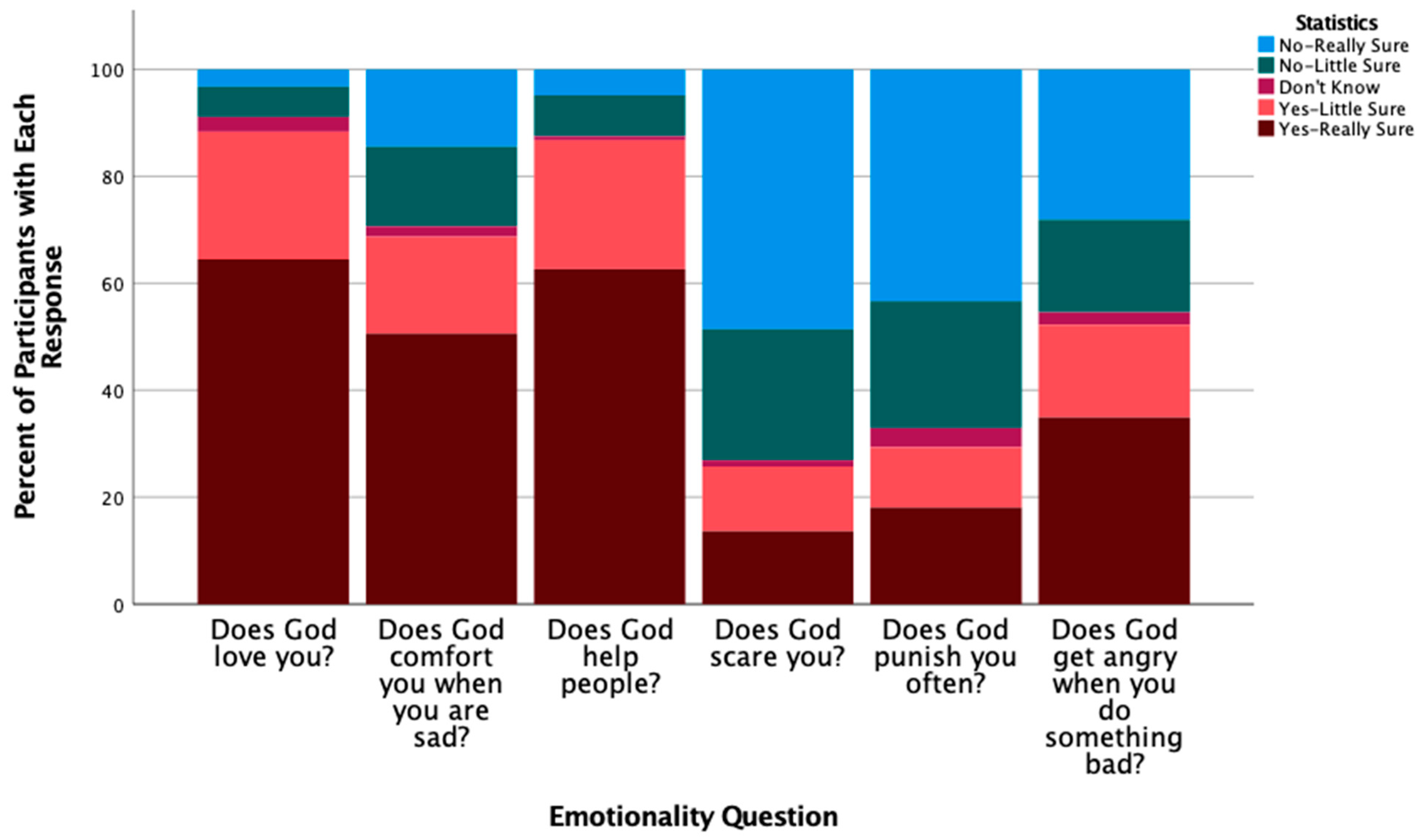

3.1. God as an Emotional and Relational Being

3.2. Age and General Religious Exposure

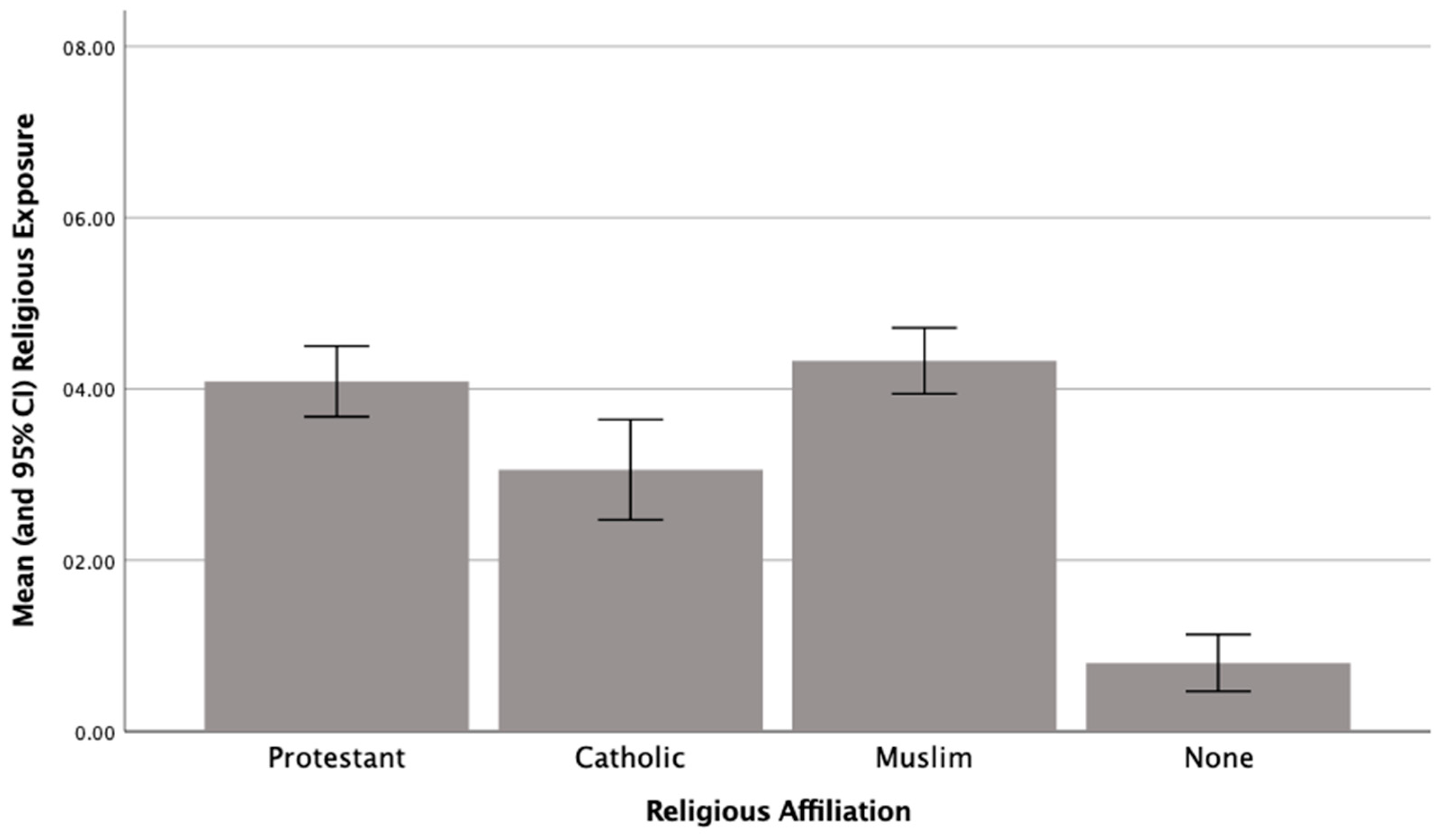

3.3. Religious Affiliation

3.4. Limitations and Future Research

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. God’s Emotional and Relational Properties

4.2.2. Religious Exposure

4.3. Procedure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrett, Justin L., Roxanne M. Newman, and Rebekah A. Richert. 2003. When seeing is not believing: Children’s understanding of humans’ and non-humans’ use of background knowledge in interpreting visual display. Journal of Cognition and Culture 3: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, John. 1973. Attachment and Loss: Separation, Anxiety, and Anger. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, Chris J. 2005. Religious and spiritual development in childhood. In The Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Palotzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 123–43. [Google Scholar]

- Burdett, Emily. 2020. A child developmental perspective: Understanding human supernatural limitation and providence. In Divine and Human Providence: Philosophical, Psychological, and Theological Approaches. Edited by Ignacio Silva and Simon M. Kopf. London: Routledge, pp. 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Burdett, Emily, Justin L. Barrett, and Tyler S. Greenway. 2020. Children’s developing understanding of the cognitive abilities of supernatural and natural minds: Evidence from three cultures. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 14: 124–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, Emily R., and Justin L. Barrett. 2016. A cross-cultural comparison of children’s attribution of life-cycle traits. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 34: 276–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corriveau, Kathleen H., Eva E. Chen, and Paul L. Harris. 2015. Judgments about fact and fiction by children from religious and nonreligious backgrounds. Cognitive Science 39: 353–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Yixin Kelly, Jennifer M. Clegg, Eleanor Fang Yan, Telli Davoodi, Paul L. Harris, and Kathleen H. Corriveau. 2020. Religious testimony in a secular society: Belief in unobservable entities among Chinese parents and their children. Developmental Psychology 56: 117–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, Telli, Maryam Jamshidi-Sianaki, Faezeh Abedi, Ayse Payir, Yixin Kelly Cui, Paul L. Harris, and Kathleen H. Corriveau. 2019. Beliefs about religious and scientific entities among parents and children in Iran. Social Psychological and Personality Science 10: 847–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roos, Simone A. 2006. Young children’s God concepts: Influences of attachment and religious socialization in a family and school context. Religious Education 101: 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Roos, Simone A., Jurjen Iedema, and Siebren Miedema. 2001a. Young children’s descriptions of God: Influences of parents’ and teachers’ God concepts and religious denomination of schools. Journal of Beliefs and Values 22: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roos, Simone A., Jurjen Iedema, and Siebren Miedema. 2004. Influence of maternal denomination, God concepts, and child-rearing practices on young children’s God concepts. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43: 519–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roos, Simone A., Siebren Miedema, and Jurjen Iedema. 2001b. Attachment, working models of self and others, and God concepts in kindergarten. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40: 607–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roos, Simone A., Siebren Miedema, and Jurjen Iedema. 2003. Effects of mothers’ and schools’ religious denomination on preschool children’s God concepts. Journal of Beliefs & Values 24: 165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Denervaud, Solange, Christian Mumenthaler, Edouard Gentaz, and David Sander. 2020. Emotion recognition development: Preliminary evidence for an effect of school pedagogical practices. Learning and Instruction 69: 101353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickie, Jane R., Amy K. Eshlemen, Dawn M. Merasco, Amy Shepard, Michael Vander Wilt, and Melissa Johnson. 1997. Parent-child relationships and children’s images of God. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36: 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doebel, Sabine. 2020. Rethinking executive function and its development. Perspectives on Psychological Science 15: 942–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, Cristopher G., Matt Bradshaw, Kevin J. Flannelly, and Kathleen C. Galek. 2014. Prayer, attachment to God, and symptoms of anxiety-related disorders among US adults. Sociology of Religion 75: 208–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, Ansley T., Melissa M. Brown, and Jillian M. Pierucci. 2015. Relations between fantasy orientation and emotion regulation in preschool. Early Education and Development 26: 920–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Dasí, Martha, Silvia Guerrero, and Paul L. Harris. 2005. Intimations of immortality and omniscience in early childhood. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 2: 285–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, Pehr, and Jane R. Dickie. 2006. Attachment and spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. In The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence. Edited by Euguene C. Roehlkepartain, Pamela E. King, Linda Wagner and Peter L. Benson. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist, Pehr, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2008. Attachment and religious representations and behavior. In The Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Edited by Jude Cassidy and Phillip J. Shaver. New York: The Gilford Press, pp. 906–33. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist, Pehr, Cecilia Ljungdahl, and Jane R. Dickie. 2007. God is nowhere, God is now here: Attachment activation, security of attachment, and God’s perceived closeness among 5–7-year-old children from religious and non-religious homes. Attachment & Human Development 9: 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, Pehr, Mario Mikulincer, and Phillip J. Shaver. 2010. Religion as attachment: Normative processes and individual differences. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Paul L., Melissa A. Koenig, Kathleen H. Corriveau, and Vikram K. Jaswal. 2018. Cognitive foundations of learning from testimony. Annual Review of Psychology 69: 251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiphetz, Larisa, Jonathan D. Lane, Adam Waytz, and Liane L. Young. 2016. How children and adults represent God’s mind. Cognitive Science 40: 121–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, Bradley R., and Michael J. Donahue. 1995. Parental influences on God images among children: Testing Durkheim’s metaphoric parallelism. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34: 186–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebler-Ragger, Michaela, Johanna Falthansl-Scheinecker, Gerhard Birnhuber, Andreas Fink, and Human F. Unterrainer. 2016. Facets of spirituality diminish the positive relationship between insecure attachment and mood pathology in young adults. PLoS ONE 11: e0158069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiessling, Florian, and Josef Perner. 2014. God-mother-baby: What children think they know. Child Development 85: 1601–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Pamela E., and Chris J. Boyatzis. 2015. Religious and spiritual development. In The Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Socioemotional Processes. Edited by Michael E. Lamb and Richard M. Lerner. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 975–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Pamela E., Jenel S. Ramos, and Casey E. Clardy. 2013. Searching for the sacred: Religion, spirituality, and adolescent development. In The APA handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality: Vol. 1. Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and James W. Jones. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 513–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A., and Phillip R. Shaver. 1990. Attachment theory and religion: Childhood attachments, religious beliefs, and conversion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29: 315–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Nicola, Paulo Sousa, Justin L. Barrett, and Scott Atran. 2004. Children’s attributions of beliefs to humans and God: Cross-cultural evidence. Cognitive Science 28: 117–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, Tamar. 2022. Imagination and social cognition in childhood. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 13: e1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Jonathan D., Henry M. Wellman, and E. Margaret Evans. 2010. Children’s understanding of ordinary and extraordinary minds. Child Development 81: 1475–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legare, Cristine H., and Mark Nielsen. 2015. Imitation and innovation: The dual engines of cultural learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 19: 688–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, Annette. 2010. Religion in families, 1999–2009: A relational spirituality framework. Journal of Marriage and Family 72: 805–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, Nikos, and Dimitris Pnevmatikos. 2007. Children’s understanding of human and super-natural mind. Cognitive Development 22: 365–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, Maureen, Bahger Ghobary-Bonah, and Martin Dowson. 2017. Development of a measure of attachment to God for Muslims. Review of Religious Research 59: 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, Hart M., Raymond H. Potvin, and Joseph Shields. 1977. The Religion of Children. Washington, DC: United States Catholic Conference Public Office. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhof, Melanie A., and Carl N. Johnson. 2017. Is God just a big person? Children’s conceptions of God across cultures and religious traditions. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 35: 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirutinsky, Steven, David H. Rosmarin, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2019. Is attachment to God a unique predictor of mental health? Test in a Jewish sample. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richert, Rebekah A., Nicholas J. Shaman, Anondah R. Saide, and Kirsten A. Lesage. 2016. Folding your hands helps God hear you: Prayer and anthropomorphism in parents and children. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion 27: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuto, Ana-Marie. 1979. Birth of the Living God: A Psychoanalytic Study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, Barbara, Leslie C. Moore, Maricela Correa-Chávez, and Amy L. Dexter. 2015. Children develop cultural repertoires through engaging in everyday routines and practices. Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research 2: 472–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ruba, Ashley L., and Seth D. Pollak. 2020. The development of emotion reasoning in infancy and early childhood. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology 2: 503–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saide, Anondah R., and Rebekah A. Richert. 2020. Socio-cognitive and cultural influences on children’s concepts of God. Journal of Cognition and Culture 20: 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saide, Anondah R., and Rebekah A. Richert. 2022. Correspondence in parents’ and children’s concepts of God: Investigating the role of parental values, religious practices and executive functioning. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology 40: 422–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seja, Astrida L., and Sandra W. Russ. 1999. Children’s fantasy play and emotional understanding. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 28: 269–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaman, Nicholas J., Kirsten A. Lesage, and Rebekah A. Richert. 2016. Who cares if I stand on my head when I pray? Ritual inflexibility and mental-state understanding in preschoolers. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion 27: 122–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtulman, Andrew. 2008. Variation in the anthropomorphization of supernatural beings and its implications for cognitive theories of religion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 34: 1123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtulman, Andrew, and Marjaana Lindeman. 2016. Attributes of God: Conceptual foundations of a foundational belief. Cognitive Science 40: 635–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, Paul S., Andrew Downs, and Celestina Barbosa-Leiker. 2016. Does facial expression recognition provide a toehold for the development of emotion understanding? Developmental Psychology 52: 1182–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulp, Henk P., Jurrijn Koelen, Gerrit G. Glas, and Liesbeth Eurelings-Bontekoe. 2021. Validation of the apperception test God representations, an implicit measure to assess God representations. Part 3: Associations between implicit and explicit measures of God representations and self-reported level of personality functioning. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 23: 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau-Nielsen, Rachel B., Danielle Turley, Jason A. DeCaro, Ansley T. Gilpin, and Alexandra F. Nancarrow. 2021. Physiological substrates of imagination in early childhood. Social Development 30: 867–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson-Jones, Rachel E., and Cristine H. Legare. 2016. The social functions of group rituals. Current Directions in Psychological Science 25: 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, Jacqueline D., and Victoria Cox. 2007. Development of beliefs about storybook reality. Developmental Science 10: 681–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, Jacqueline D., Chelsea A. Cornelius, and Walter Lacy. 2011. Developmental changes in the use of supernatural explanations for unusual events. Journal of Cognition and Culture 11: 311–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, Philip David, and Ulrich Müller. 2011. Executive function in typical and atypical development. In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Cognitive Development. Edited by Usha Goswami. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

| Love | Comfort | Help | Scare | Punish | Angry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Love | -- | |||||

| Comfort | 0.441 *** | -- | ||||

| Help | 0.648 *** | 0.526 *** | -- | |||

| Scare | −0.313 ** | −0.037 | −0.239 *** | -- | ||

| Punish | −0.166 ** | −0.038 | −0.121 t | 0.347 *** | -- | |

| Angry | 0.193 ** | 0.279 *** | 0.173 ** | 0.121 t | 0.264 *** | -- |

| Age | Religious Exposure (RE) | Age (Partial Out RE) | Religious Exposure (Partial out Age) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Love | 0.266 ** | 0.178 * | 0.187 ** | 0.214 ** |

| Comfort | 0.201 ** | 0.174 ** | 0.141 * | 0.204 ** |

| Help | 0.197 ** | 0.182 ** | 0.094 | 0.200 ** |

| Scare | −0.346 ** | −0.029 | −0.337 *** | 0.020 |

| Punish | −0.145 * | −0.015 | −0.092 | 0.012 |

| Angry | 0.084 | 0.187 ** | 0.082 | 0.176 ** |

| Protestant | Catholic | Muslim | Non-Affiliated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Love | 1.570 (0.772) a | 1.330 (1.211) | 1.550 (0.830) b | 1.000 (1.268) a,b | 3.887 (0.214) ** |

| Comfort | 0.880 (1.478) a | 0.430 (1.664) b | 1.260 (1.272) b,c | 0.110 (1.618) a,c | 6.769 (0.277) *** |

| Help | 1.510 (0.995) | 1.180 (1.260) | 1.430 (1.035) | 1.000 (1.268) | 2.522 (0.173) |

| Scare | −0.570 (1.601) | −0.780 (1.447) | −1.160 (1.365) | −0.740 (1.421) | 2.125 (0.159) |

| Punish | −0.620 (1.623) | −0.550 (1.553) | −0.740 (1.588) | −0.550 (1.427) | 0.213 (0.051) |

| Angry | 0.060 (1.696) | −0.120 (1.705) | 0.590 (1.703) a | −0.190 (1.541) a | 2.894 (0.185) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.J.; Marin, A.B.; Sun, J.; Richert, R.A. Does God Comfort You When You Are Sad? Religious Diversity in Children’s Attribution of Positive and Negative Traits to God. Religions 2023, 14, 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091181

Lee HJ, Marin AB, Sun J, Richert RA. Does God Comfort You When You Are Sad? Religious Diversity in Children’s Attribution of Positive and Negative Traits to God. Religions. 2023; 14(9):1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091181

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Hea Jung, Ashley B. Marin, Jiayue Sun, and Rebekah A. Richert. 2023. "Does God Comfort You When You Are Sad? Religious Diversity in Children’s Attribution of Positive and Negative Traits to God" Religions 14, no. 9: 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091181

APA StyleLee, H. J., Marin, A. B., Sun, J., & Richert, R. A. (2023). Does God Comfort You When You Are Sad? Religious Diversity in Children’s Attribution of Positive and Negative Traits to God. Religions, 14(9), 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091181