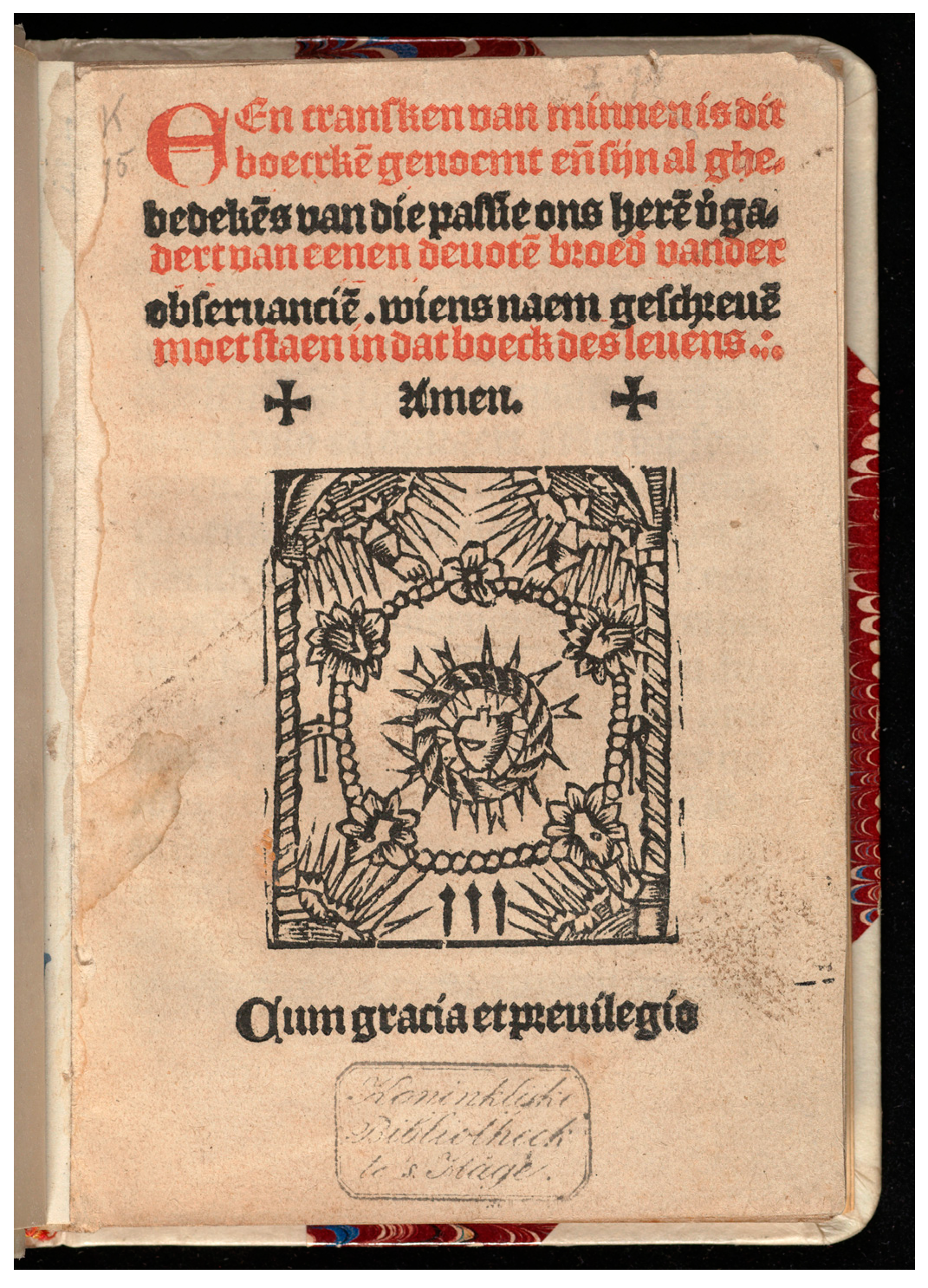

Visualisation in Late-Medieval Franciscan Passion Literature from the Low Countries: Cransken van minnen (Wreath of Love), 1518

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Research Question

Siet hoe uut overvloedich uut storten sijns gebenedide bloets hem zijn menschelike natuerlike cracht ontgaet ende hanct aen den touwen crimpende overmits zijn diepe wonden als een worm van grote onsprekelike pijne.

One can read this verb, phrased in the imperative, as an invitation, or even command, to picture this scene, which is traumatic but also with great power for evoking empathy, in one’s imagination. The account of the changes to Christ’s physical appearance during the Passion was rendered more dramatic by a simile (aligned theologically with the Christian interpretation of Isaiah 53:3) that metamorphosed His figure into the image of a writhing invertebrate. In another passage, devotees were invited to “see” Jesus’ head turning towards Mary during the last moments on the Cross, as if to bid her farewell (Anonymous and Wentsen 1534). Here the reader, presented with Mary’s compassionate focalization, was guided by the text to internalize what she has seen. To paraphrase this situation in terms derived from narratology, Mary acts as an external “focalizer” of the scene (Bal and van Boheemen 2009, pp. 151–52). The effect is to create a multifocal perspective in which Mary, as a main protagonist, becomes a mediator on the level of sensory information about the events being described.See, how through the excessive loss of His blessed blood his human, natural strength abandons Him, as He is left hanging on a rope, shrinking like a worm in inexpressible pain on account of His deep wounds.

3. Cransken van minnen

3.1. Form and Structure

- An apostrophe to God the Father, Christ or Mary;

- A narrative description of the scene from the Gospel which is the subject of the meditation, often addressed in the second person to God, Christ or Mary;

- A meditation on the emotions or reactions of the addressee of the prayer (God, Christ or Mary);

- A petition concerning the spiritual or (less often) the physical needs of the narrator.

3.2. A Program of Meditation

4. Meditation and Visualization in Cransken van minnen: Revealing What Is Hidden

4.1. Visualizing Mary and the Mystery of the Incarnation

4.2. Visualizing Spiritual Processes

4.3. The Anamnesis of the Passion of Christ, Mary and “Virtual Witnessing”

O alder soetste moeder Maria dat swaert doersneet u reyne hart als ghi stont onder den cruys. Ende aensaecht dye vrucht dijns lichaems dijn gebenedide soen Jesum Cristum soe versmadeliken hangen tusschen twe dieuen…

Mary’s mediation between the faithful and God (Christ) is not limited to the traditional area of intercession, but also occurs in relation to her visual (or, more broadly, sensory) experience of the Passion. Mary becomes a witness whose affective reaction (fear, exhaustion and pain) allows the narrator to introduce the theological trope of her pierced heart, which is derived from Simeon’s prophecy (Luke 2:35). Creating this role for Mary, Cransken van minnen is similar to, for instance, Love’s Mirror. Mary’s unique position in this respect also enhances the authenticity and credibility of the scene by creating a multifocal perspective. Along with Mary, the reader enters the scene and becomes a virtual co-witness. By seeing what Mary saw, a devotee praying the prayers from this book can achieve a complete experience of anamnesis, spiritually reliving her special physical and affective experience and thus vicariously assuming the role of a key participant in the Gospel narrative.O sweetest mother Mary, that sword pierced your pure heart when you were standing under the cross. And you saw the fruit of your body, your blessed son Jesus Christ, hanging so despicably between two thieves…

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Translation of Meditation [35–Christ Is Nailed to the Cross] from Cransken van minnen, fols. 34r-34v

References

- Anonymous. 1518. Cransken van minnen. Den Haag, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, 227 G 13. Delft: Cornelis Hendricszoon Lettersnijder. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous, and Matthijs Wentsen. 1534. Fasciculus myrre. Gent, Universiteitsbibliotheek, BHSL.RES.1538/-1. Antwerp: Willem Vorsterman. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, Mieke, and Christine van Boheemen. 2009. Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1991. Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrówka, Andrzej. 2019. Theater and the Sacred in the Middle Ages. Berlin: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Troeyer, Benjamin. 1969. Bio-Bibliographia Franciscana Neerlandica Saeculi XVI. Nieuwkoop: De Graaf, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Depestele, Kaat. 2010. De verspreiding van de devotie van de rozenkrans gekoppeld aan het gebruik van devotionele handboeken in de Nederlanden (1470 tot 1540). Master’s thesis, Universiteit Gent, Gent, Belgium. Available online: https://lib.ugent.be/nl/catalog/rug01:001457775/files/0 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Dlabačová, Anna. 2014. Literatuur en observantie: De Spieghel der volcomenheit van Hendrik Herp en de dynamiek van laatmiddeleeuwse tekstverspreiding. Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburg, Reindert. 2001. The Household of the Soul: Conformity in the Merode Triptych. In Early Netherlandish Painting at the Crossroads. A Critical Look at Current Methodologies. Edited by Marian Wynn Ainsworth. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Symposia, pp. 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Falque, Ingrid. 2019. Devotional Portraiture and Spiritual Experience in Early Netherlandish Painting. Leiden: BRILL. [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan, Koen. 2016. Piety in Practice and Print: Essays on the Late Medieval Religious Landscape. Studies in Dutch Religious History 4. Hilversum: Verloren. [Google Scholar]

- Karnes, Michelle. 2011. Imagination, Meditation, and Cognition in the Middle Ages. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Love, Nicholas. 2004. The Mirror of the Blessed Life of Jesus Christ. A Reading Text. Edited by Michael G. Sargent. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNamer, Sarah. 2010. Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Marcel. 1997. History of the Liturgy: The Major Stages. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peirats, Anna, and Rubén Gregori. 2023. Meditation and Contemplation: Word and Image at the Service of Medieval Spirituality. Religions 14: 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleij, Herman. 2000. Anna Bijns als pamflettiste? Het refrein over de beide Maartens. Spiegel der Letteren 42: 187–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Earl Jeffrey. 2008. Das Gebet ‘Anima Christi’ und die Vorgeschichte seines kanonischen Status: Eine Fallstudie zum kulturellen Gedächtnis. Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch 49: 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Earl Jeffrey. 2016. The prayer Anima Christi and Dominican popular devotion: Late medieval examples of the interface between high ecclesiastical culture and popular piety. In Poverty and Devotion in Mendicant Cultures 1200–1450. Edited by Constant J. Mews and Anna Welch. London: Routledge, pp. 105–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roest, Bert. 2004. Franciscan Literature of Religious Instruction before the Council of Trent. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rudy, Kathryn M. 2016. Rubrics, Images and Indulgences in Late Medieval Netherlandish Manuscripts. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent, Michael G. 2017. Nicholas Love’s Mirror of the Blessed Life of Jesus Christ. In The Wycliffite Bible: Origin, History and Interpretation. Leiden: Brill, pp. 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, Wolfgang. 1936. Het Aandeel der Minderbroeders in onze Middeleeuwse Literatuur. Inleiding tot een Bibliografie der Nederlandse Franciscanen. Nijmegen: Dekker & Van de Vegt. [Google Scholar]

- Shapin, Steven. 1984. Pump and Circumstance: Robert Boyle’s Literary Technology. Social Studies of Science 14: 481–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Laan, Joanka. 2020. Enacting Devotion: Performative Religious Reading in the Low Countries (ca. 1470–1550). Ph.D. thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, Jozef. 1940. Geschiedenis van de letterkunde der Nederlanden. s-Hertogenbosch: Teulings Uitgevers-maatschappij L.C.G. Malmberg, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Viladesau, Richard. 2006. The Beauty of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts from the Catacombs to the Eve of the Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Contents | Foliation |

|---|---|---|

| [1] | Creation of the world and of man, incipit echoing John 1:1–3 | 3r-4r |

| [2] | The Holy Trinity | 4r-5r |

| [3] | God the Father and Christ’s mission to redeem mankind | 5r-6r |

| [4] | The Annunciation | 6r-7r |

| [5] | The Visitation of Elisabeth | 7r-8r |

| [6] | The Nativity | 8r-9r |

| [7] | The Presentation in the Temple | 9r-9v |

| [8] | The Adoration of the Magi | 10r-10v |

| [9] | The Massacre of the Innocents; the Flight into Egypt | 10v-11v |

| [10] | The finding of Christ in the temple | 11v-12r |

| [11] | The beginning of Christ’s public life, baptism, in the desert | 12v-13r |

| [12] | Mary as an intercessor | 13r-14r |

| [13] | Christ’s miracles; Christ as a healer | 14r-15r |

| [14] | Entry into Jerusalem | 15r-16r |

| [15] | The cleansing of the temple; Christ and Mary Magdalene | 16r-17r |

| [16] | Preparation for the Last Supper | 17r-17v |

| [17] | Christ washes the feet of the disciples | 17v-18v |

| [18] | The Last Supper | 18v-19v |

| [19] | In the garden of Gethsemane | 19v-20v |

| [20] | The betrayal of Christ | 20v-21v |

| [21] | Christ before Annas | 21v-22r |

| [22] | Christ betrayed by Peter and abandoned by other disciples | 22r-23r |

| [23] | General meditation on Christ’s suffering | 23r-23v |

| [24] | Christ appears before Caiphas | 24r-24v |

| [25] | Christ appears before Pilate and Herod | 25r-25v |

| [26] | Christ again appears before Pilate | 25v-26v |

| [27] | Christ clad in a purple robe and crowned with thorns | 26v-27v |

| [28] | Ecce homo; Barabbas chosen over Christ | 27v-28r |

| [29] | Christ is condemned by Pilate | 28v-29r |

| [30] | Mary meets Christ | 29v-30r |

| [31] | Christ begins the Way of the Cross | 30r-31r |

| [32] | The sorrow of Mary during the Way of the Cross | 31r-32r |

| [33] | Christ stripped of his garments | 32r-32v |

| [34] | Meditations on the sins of the narrator | 32v-33v |

| [35] | Christ is nailed to the cross | 34r-34v |

| [36] | Christ is crucified between two thieves | 34v-35v |

| [37] | Christ’s suffering on the cross | 35v-36v |

| [38] | Mary under the cross | 36v-37v |

| [39] | Christ speaks to Mary and John, and to the penitent thief | 37v-38v |

| [40] | The last words of Christ on the cross; Christ given vinegar | 38v-39v |

| [41] | Meditation on Christ’s suffering and the redemption of mankind | 39v-40v |

| [42] | First meditation on the death of Christ | 40v-41v |

| [43] | Second meditation on the death of Christ | 41v-42v |

| [44] | Meditation on the redemption of humankind through Christ’s death | 42v-43v |

| [45] | Meditation on the passion and on penitence | 43v-44v |

| [46] | The heart of Christ pierced on the cross; meditation on Christ’s holy blood (with the Anima Christi prayer) 1 | 44v-45v |

| [47] | The sorrows of Mary | 45v-47r |

| [48] | Christ’s descent into hell | 47r-47v |

| [49] | The burial of Christ | 48r-48v |

| [50] | Mary’s sorrow during the burial of Christ | 48v-49v |

| [51] | Resurrection of Christ | 49v-50v |

| [52] | The Eucharist and Pentecost | 50v-52r |

| [53] | Meditation on Mary | 52r-53r |

| [54] | Christ appearing to disciples after the Resurrection; Pentecost | 53r-54v |

| [55] | Assumption of Mary | 54v-55v |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polkowski, M. Visualisation in Late-Medieval Franciscan Passion Literature from the Low Countries: Cransken van minnen (Wreath of Love), 1518. Religions 2023, 14, 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091156

Polkowski M. Visualisation in Late-Medieval Franciscan Passion Literature from the Low Countries: Cransken van minnen (Wreath of Love), 1518. Religions. 2023; 14(9):1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091156

Chicago/Turabian StylePolkowski, Marcin. 2023. "Visualisation in Late-Medieval Franciscan Passion Literature from the Low Countries: Cransken van minnen (Wreath of Love), 1518" Religions 14, no. 9: 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091156

APA StylePolkowski, M. (2023). Visualisation in Late-Medieval Franciscan Passion Literature from the Low Countries: Cransken van minnen (Wreath of Love), 1518. Religions, 14(9), 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091156