2. Cosmic Change in the Kun–Peng Fable: From Perspectives to Processes

The “perspectivist” interpretation stands on solid ground. It is indisputable that the Kun/Peng story revolves around the issue of perspectives. However, a sole emphasis on this aspect overlooks or diminishes other crucial elements, particularly the theme of transformation or

hua 化, which scholars such as Thomas Michael and James D. Sellman have highlighted as the first great term of philosophical significance to appear in the text (

Sellman 1998, p. 167;

Michael 2005, p. 12). In this sense, the introduction of this concept in relation to the description of Kun and Peng has profound implications. Accordingly, several scholars argue that Kun/Peng should be regarded not only as representatives of a broader perspective in contrast to a narrower one but also and most importantly as embodiments of the process of cosmic transformation, closely in keeping with one of the central themes of the text.

Accordingly, in analyzing the opening passage of the

Xiaoyaoyou chapter, Thomas Michael draws compelling parallels between the Kun–Peng dichotomy and other cosmological narratives prevalent during that period, notably the myths of Fuxi 伏羲 and Nuwa 女媧 and specifically in an effort to examine “the motif of the dragon-tiger pair and its probable position within early Chinese myth” (

Michael 2005, p. 8) and, more specifically, “the mythological imagery that associates dragons, snakes, watery chaos, and generation through the incestuous intercourse of a primordial couple” (

Michael 2005, p. 8). Michael explains that Peng and Kun should be understood as the symbolic equivalents of Fuxi and Nuwa, respectively, insofar as the characterization of Fuxi as a dragon (

long 龍) embodying yang forces and of Nuwa as a phoenix (

feng 鳳) exemplifying yin forces parallels the description of Peng as a bird and Kun as a fish, specifically in that order (

Michael 2005, p. 11). By identifying the Kun/Peng binomial with the Nuwa/Fuxi binomial, Michael establishes a correlation between these two and the yinyang 陰陽 binomial, thus providing various other interesting correlations: “In the traditional attributes of yin-yang, yin is commonly associated with the north, darkness, winter, and water, and yang with the south, brightness, summer, and fire”. (

Michael 2005, p. 11). In this way, Michael invites us to understand the interrelations between Kun and Peng at the light of the five phases theory (

wuxing 五行). He then proceeds to expand these correlations by way of the

Yijing 易經 and Norman Girardot’s

Myth and Meaning in Early Taoism (

Girardot 2009). The resulting picture is the following: Kun relates to Nuwa, yin, female, winter, north, phoenix, horse, snail, frog, water, and the Kun (second)

Yijing hexagram. Peng relates to Fuxi, yang, male, summer, south, dragon, snake, fire, and the Qian (first)

Yijing hexagram. I ponder all of these valences to be correct, and I shall adopt them in my own interpretation of the passage. Michael’s analysis, however, does not end there, as he also stresses the fact that all the interrelations belonging to the Kun/Peng binomial, like those between the yin and the yang, are to be understood as essentially procreative interactions. Specifically, the pattern of interaction of Fuxi and Nuwa, as a primordial couple, replicates the behavior of yang and yin forces in the cosmos, inasmuch as the continuous and fertile interaction of these two forces is seen as forming the metaphysical basis for the workings of the cosmos: “the fish transforms itself into the bird, in the same way that yin changes into yang and yang into yin throughout the course of the annual progression of the seasons”. (

Michael 2005, p. 12). Thus, the Kun–Peng transformation mirrors one of the most fundamental aspects of yin–yang interaction, namely “contradiction and opposition” (

maodun 矛盾). Regarding this, Robin Wang explains the following: “Although yinyang thought may prompt us to think of harmony, interconnection, and wholeness, the basis of any yinyang distinction is difference, opposition, and contradiction. Any two sides are connected and related, but they are also opposed in some way, like light and dark, male and female, forceful and yielding. It is the tension and difference between the two sides that allows for the dynamic energy that comes through their interactions” (

Wang 2012, p. 9)

In this way, as per Michael’s reading, the opening stanza of the

Xiaoyaoyou chapter refers mostly to yin–yang interactions in the form of cosmic correlations and seasonal fluctuations. However, it is important to contextualize Michael’s interpretation by considering other similar readings of the passage in question. As I have shown, Michael chooses to read the passage as allegorically referring to cosmic transformations and correlations. However, Michael’s allegorical approach concerning cosmic transformations and correlations is not entirely original, as Kuang-Ming Wu previously interpreted the same passage in relation to the forces that serve as the metaphysical groundwork for the functioning of the cosmos:

yinyang 陰陽,

qi 氣, and

wuxing 五行. According to Wu, the “North” is a region of the yin, that is, the shaded, the hidden, the pit (k’an, perhaps rhyming with k’un), the water, and the winter. It is where the breaths (ch’i) of weather and things rise and gradually shift to the yang. It is the beginning of the Five Elementary Ways of things that change and interchange in the yin-yang cycle” (

Wu 1990, p. 69). Similarly, for Wu, “P’ung (Peng) implies big and social as can be seen by its synonym, fung, regal phoenix” (parenthesis is mine,

Wu 1990, p. 71), and, in this passage, “the Yang, the south (is) incarnated in the Bird” (parenthesis is mine,

Wu 1990, p. 71). As evident, many of the associations established by Michael were previously developed by Wu. Both scholars identify Kun with yin 陰, water, and winter and Peng with the phoenix and yang. However, Wu’s interpretation slightly expands Kun’s semantic scope by correlating this creature with concepts like the hidden, the shaded, and the pit as well as the image of a place from where things rise and develop—an image of a beginning. Similarly, Kirill Ole Thompson, drawing on Ming’s analysis (

Thompson 1998, p. 17, n. 9), interprets the passage as exemplifying “primal yin and yang qi impulses, movements, formations and distributions (that) shape the world…” (parenthesis is mine,

Thompson 1998, p. 17). Recently, Kim-chong Chong embraced a comparable reading, asserting that the story of Kun and Peng is linked to the “transformation of things” (

Chong 2016, p. 45). In sum, Wu, Michael, Thompson, and Chong have interpreted the Kun–Peng binomial as mirroring the yin–yang binomial and therefore the metaphysical foundations of the cosmos. In my view, these correlations are correct and, in fact, thought-provoking. However, except for these four scholars, the majority of interpreters have tended to interpret the passage not primarily in terms of metaphysical forces and cosmic transformations but rather as an exploration of “skepticism” or “relativism”, as discussed in the previous section. In what follows, I will endeavor to offer a further development of the metaphysical interpretation of the Kun–Peng fable initially developed by Kuang-Ming Wu, specifically in reference to the dragon-like aspects of this tale of cosmic transformation.

3. The Kun–Peng Binomial as a Cosmic Dragon

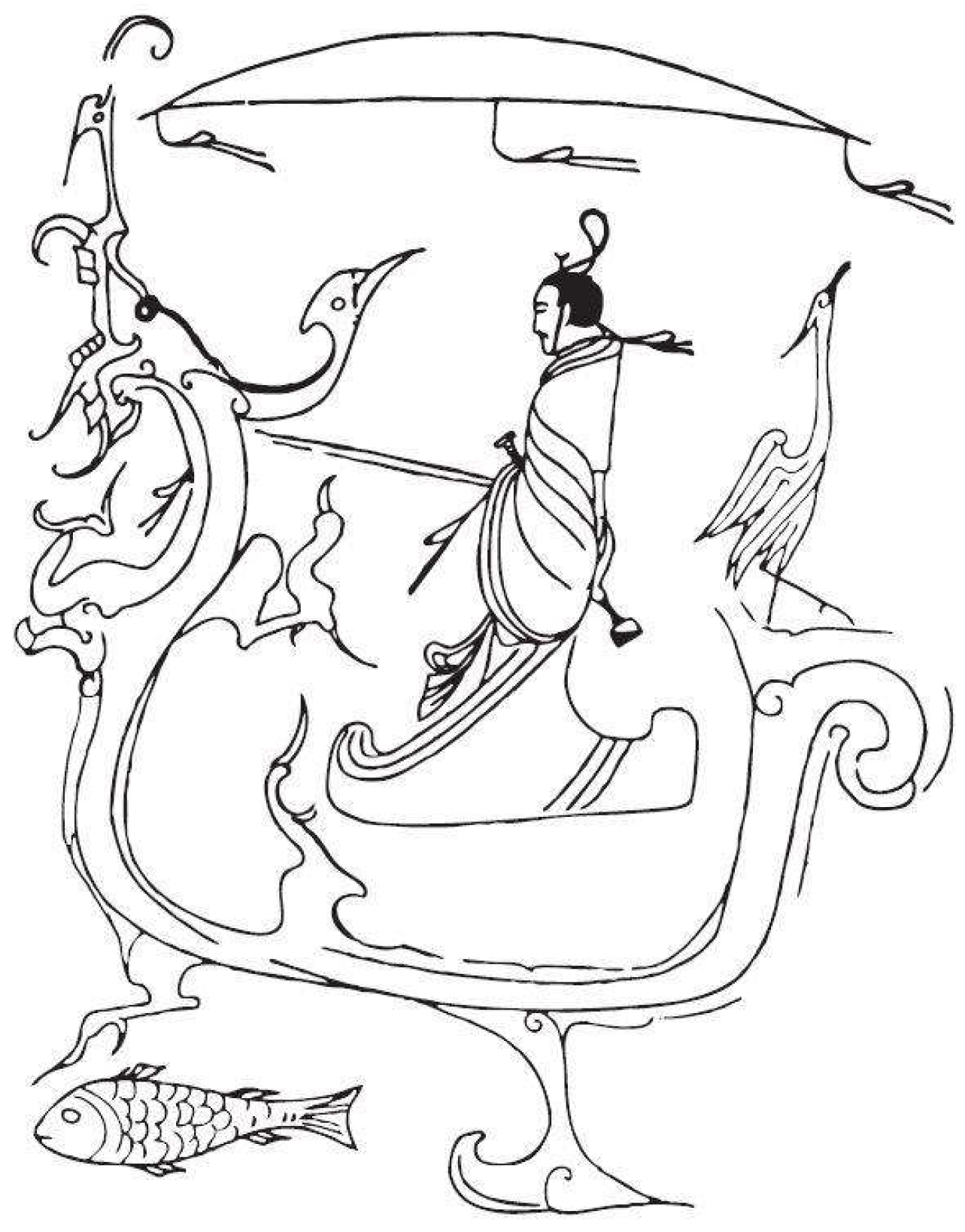

As noted, Michael suggests that the Kun–Peng binomial should be interpreted as representing a phoenix and a dragon, respectively, thus excluding Kun from being associated with this mythological creature. This correlation is, according to Michael, based on the fact that Fuxi and Nuwa traditionally represent a dragon and a phoenix, respectively. However, many graphical depictions of Fuxi and Nuwa represent them both as possessing dragon tails. In this sense, it seems possible to interpret not only Fuxi but also Nuwa as a dragon or dragon-like creature. If this interpretation is correct, then we should understand both Kun and Peng as dragons or dragon-like creatures as well. This understanding of the Kun–Peng fable as symbolizing a dragon is confirmed by the following early Chinese description of this mythical creature, specifically contained in the

Ersanzi wen 二三子問 (The Several Disciples Asked) commentarial section of the Mawangdui 马王堆 version of the

Yijing (168 BC):

龍大矣。龍既能雲變,又能蛇變,又能魚變,飛鳥 蟲,唯所 欲化,而不失本形,神能之至也。

“The dragon is great indeed. While the dragon is able to change into a cloud, it is also able to change into a reptile, and also able to change into a fish, a flying bird, or a slithery reptile. No matter how it wants to transform, that it does not lose its basic form is because it is the epitome of spiritual ability”.

Interestingly enough, this description of the dragon clearly resembles a graphical depiction found in another tomb from around the same period (second century BC, see

Figure 1). According to these sources, in early China, dragons were associated not only with reptiles and clouds but also with fishes and flying birds. The association with these last two creatures clearly echoes the story of Peng and Kun, as these two are indeed a fish and a bird, respectively. Furthermore, not only the aquatic and aerial nature of dragons but also the transformative capacity that this commentary attributes to them powerfully resounds with this story. Transformation, in fact, is what occurs when Kun gives way to Peng. This is the first major philosophical concept that occurs in the text, as Michael and other scholars have rightly noted. I do not regard these correspondences as coincidental. In my view, the fact that both the Mawangdui

Yijing’s description of a dragon and the

Zhuangzi’s Kun–Peng story link the concepts of “fish”, “bird”, and “transformation/change” together clearly points to the dragonesque character of the Kun/Peng binomial. Ultimately, this couple should be read as referring to an ontology of transformation. In fact, the most distinctive characteristic of the dragon, as this Mawangdui passage emphatically conveys, is the capacity to transform, that is, the capacity to fluidly and dynamically change shape, continuously adopting several different countenances. In this regard, Roel Sterckx explains that the Kun–Peng story exemplifies how, for the early Chinese literati, the “spontaneous generative change and transformation in the animal world also provided imagery for the description of cosmological patterns of change” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 168). I find further confirmation of this view in yet another explanation of the cosmological features of the dragon in the Mawangdui

Yijing:

二三子問曰:易屢稱於龍,龍之德何如?孔子曰:龍大矣。龍形遷假,賓于帝,俔神聖之德也。高上齊乎星辰日月而不曜,能陽也;下淪窮深潚之淵而不昧,能陰也。上則風雨奉之,下淪則有天囗囗囗。窮乎深淵則魚蛟先後之,水游之物莫不隨從。陵處則雷電養之,風雨避嚮,鳥獸弗干。

“The two or three disciples asked saying: “The Changes often mention dragons; what is the virtue of the dragon like?” Confucius said: “The dragon is great indeed. The dragon’s form shifts. When it approaches the lord in audience, it manifests the virtue of a spiritual sage; when it rises on high and moves among the stars and planets, the sun and moon, that it is not (sic) visible is because it is able to be yang; when it descends through the depths, that it does not drown is because it is able to be yin. Above, the wind and rain carry it; below, there is heaven’s … Diving into the depths, the fishes and reptiles move before and after it, and of those things that move in the currents, there are none that do not follow it. In the high places, the god of thunder nourishes it, the wind and rain avoid facing it, and the birds and beasts do not disturb it”.

Confucius extols the “virtues” (de 德) of the dragon, citing its frequent mention in the Changes (Yi 易) and comparing it to a “spiritual sage” (shensheng 神聖). Interestingly, his description of the dragon strongly resonates with the story of Kun and Peng. First, the concept of “change” or “shifting” (qian 遷) takes precedence once again, as the dragon’s greatness is attributed to its ability to traverse different realms, akin to its capacity to adopt various forms. Second, the dragon’s unique transformative ability is directly linked to the interplay of yang and yin forces. It is emphasized that the dragon’s capacity to soar through the celestial bodies such as “the stars and planets, the sun and moon” while also navigating “the depths” alongside “fishes and reptiles” without “drowning” allows it to embody both yang and yin aspects, respectively. In this manner, similar to the story of Kun and Peng, a dichotomous situation arises, where the yang realm associated with flight and the skies coexists with the yin realm related to swimming, depth, and aquatic creatures. Once again, this coexistence is made possible through the process of transformation. Notably, the dragon symbolizes both realms simultaneously and remains unaltered despite the changes it undergoes. It is neither wholly yang nor fully yin but embodies both aspects, representing the very essence of the transformative process itself. The dragon’s ability to exist as both without being exclusively identified with either aspect is evident in its submersion into the waters without drowning and its flight into the sky without averting its gaze. This remarkable characteristic seems to signify that the dragon embodies the process of cosmic transformation.

Therefore, the correlations between these two passages and the opening story of the Zhuangzi are remarkable. In both texts, we find the same set of images and correlations, emphasizing the process of transformation/change; the realm of water, depth, and fishes; as well as the domain of the skies, great altitudes, and birds. While the Zhuangzi does not explicitly state the association of these conceptual domains with the dragon and the notions of yin and yang, we can recognize that they are being communicated subtly and implicitly. The striking similarities between these passages, in terms of the presence of a dual cosmological structure and the prominence of a creature with unique transformative capacities, suggest that the Kun–Peng fable and generally the Xiaoyaoyou chapter creatively employ dragonesque imagery to outline a metaphysics of transformation.

In conclusion, I reflect on the simultaneous occurrence of water, clouds, fish, and bird in

Xiaoyaoyou 1–2 as an implicit, perhaps mythologically rooted allusion to a dragon-like figure. As noted, in Early China, dragons were believed to inhabit not only the waters but also the skies. With its dragon-like features, the Kun–Peng story can and arguably should be perceived as a representation of the cosmic transformation process itself. Furthermore, David Pankenier proposes that the dragon’s cosmic dimension also took on astronomical characteristics, notably in the form of the “dragon constellation”, which is probably referred to in the Kun hexagram of the

Yijing and held significant importance in early Chinese astronomy. Pankenier goes as far as defining this field as the “harnessing of dragons” (

Pankenier 2013, pp. 44–61).

2 He concludes that “there was an elite class of priest-astrologers… responsible for maintaining the calendar and managing ritual time. Their esoteric knowledge was materialized in the dragon-shaped bronze from the tomb of one of their own” (

Pankenier 2013, p. 80). Below, I will delve into the implications of this astronomical reference in the Kun–Peng fable and explore the metaphysical aspects of said dragon-looking tomb. However, before doing so, let us return to the issue of perspectivism.

5. A Dead Serious Joke: On the Cosmological Implications of the Shi–Quail Analogy in the Xiaoyaoyou

As noted, in our view, the problem of the perspective (

shi) of the cicada, dove, and quail as well as the specific status of the knowledge associated with it should be reassessed in light of the analogy between said flying creatures and a specific type of person, apparently related to the Warring States state apparatus. This analogy is established in the stanza right after the paragraph quoting a description of Kun and Peng in “Tang’s Questions to Ji” (湯之問棘

tang zhi wen ji), wherein a dove is depicted laughing at the humongous Peng bird and questioning her flying towards the “Southern Oblivion (南冥

nan ming)”. The analogy is established by the assertion that both the dove and the person possess a “perspective” or engage in the activity of “seeing” and “observing”:

故夫知效一官,行比一鄉,德合一君而徵一國者,其自視也亦若此矣。

(Xiaoyaoyou 3)

“And he whose knowledge is sufficient to hold an office, or whose deeds meet the needs of a village, or whose (personal) virtues please a ruler, or who is able to prove himself in a state, sees himself in just the same way”.

The person described in this passage has specific features: he possesses “knowledge” (

zhi 知), “deeds” (

xing 行), and “personal virtues” (

de 德). At the same time, he “sees himself” (

zi shi 自視) in a particular way; that is, he enjoys a specific kind of “self-perception”. In reference to the issues explained in the previous section, I shall focus on the first and the last of these features: “knowledge” and “self-perception”. But in order to clarify the specific nature of these two, I think it is crucial that we first establish who this person is or could have been. First of all, it is important to note that the different persons described here correspond to the different levels of the state administration: the office (

guan 官), the village (

xiang 鄉), and the state (

guo 國). This terminology appears to have been prevalent in early China. For example, the

Wenwang Shizi 文王世子 chapter of the

Liji 禮記 makes use of it as follows:

古者,庶子之官治,而邦國有倫;邦國有倫,而眾鄉方矣。

(Wenwang Shizi 28)

“Anciently, when the duties of the royal offices were well governed, the regions and states had ordered human relations; when the regions and the states had ordered human relations, then the masses and the villages were also in order”.

Although the contents of this stanza differ notably from the

Xiaoyaoyou stanza just quoted, both of them describe basically the same structure of administration. Excluding the mention of “regions” (

bang 邦) and “masses” (

zhong 眾), the passage reiterates the division of the polity in offices, villages, and states. It is significant that these categories are deployed specifically in reference to the act of “good government” (

zhi 治), as it reveals that this terminology refers not solely to territorial demarcations but more generally to the running of the state apparatus, particularly as it was used to administer villages and masses. As the phrasing of the

Xiaoyaoyou suggests, the person at the top of this administrative hierarchy, i.e., the one in charge of the state, was the ruler (

jun 君), so the person who knew how to please him was the same person who knew how to prove himself useful to the state, a person who, moreover, necessarily had to be located in the administrative echelon immediately below the monarch and directly under his authority and was charged with the responsibility of managing either an office or a village. It is plausible to speculate, I believe, that the person in question is none other than a

shi 士, that is, a “scholar-official”, “gentleman”, or “man-of-service”. As Mu-chou Poo 蒲慕州 explains, originally the

shi were “knights” or “warriors” of the Zhou aristocracy, but “with their knowledge of the affairs of the state, they gradually became, in a sense, advisors to the power holders, i.e., rulers, princes, or nobles of different ranks. They became people with knowledge, ‘intellectuals’who participated at every level of the government”. (

Poo 2018, p. 30). This process started in the Spring and Autumn period and culminated in the Warring States period (

Pines 2002), thus being well in place by the time the

Zhuangzi was written. Consequently, according to the historical record, the term

shi refers precisely to an individual who not only pleases the ruler and proves himself useful to the state but also holds office and is in charge of satisfying the needs of a village. In conclusion, the main character of the

Xiaoyaoyou stanza in question appears to embody the characteristics of these

shi.

Now, there is one specific

shi that interests us here: the one that is employed in an office (

guan), as this is the one that the stanza in question describes as possessing

zhi or “knowledge”, more specifically, knowledge that is “sufficient for an office” (

xiao yi guan 效一官). As suggested, the stanza articulates the problem of “knowledge” specifically in reference to the issue of how this knower/official, a

shi, “sees himself” (

zi shi). This is significant, as it reveals that the subject of “perspective” (

shi) is presented specifically in terms of “self-perspective” or what could also be translated as “self-perception” or “self-image”. In other words, the stanza appears to be discussing the problem of “identity”, which, as Hans-Georg Moeller and Paul J. D’Ambrosio explain, is one of the

Zhuangzi’s major concerns (

Moeller and D’Ambrosio 2017). Specifically in this case, the issue of identity is discussed in reference to the status of the

shi as both a knower and an official: The text seems determined to deal with the problem of how those that possess knowledge (or claim to possess it) and hold office see themselves the way they do and to explain why their self-image is problematic. We suggest that a tentative reconstruction of the Zhuangzian critique of the self-identity of the

shi as a knower and an official as well as of its cosmological presuppositions should proceed by way of the following question: What does it mean to compare a

shi with a quail? What does this analogy entail in terms of cosmology?

Several authors have noted the humorous nature of the

Xiaoyaoyou chapter and generally the

Zhuangzi. In reference to the Kun–Peng fable, for instance, Schwitzgebel comments that “Zhuangzi seems to be mocking the texts, histories, and tales of antiquity, as well as the philosophers of other schools who cite them to support their assertions” (

Schwitzgebel 1996, p. 71). I concur with the initial part of this statement, acknowledging the sarcastic tone of the Kun–Peng story. Moreover, I believe this comicality extends to the

shi–quail analogy, making it a form of jest. However, in contrast to Schwitzgebel’s suggestion that the Kun–Peng fable critiques “the philosophers of other schools”, I contend that the primary target of Zhuangzian satire is the “scholar-officials” (

shi) in general. These individuals, as intellectuals of the time, comprised the administrative apparatus of the Warring States, with philosophers or “masters” (

zi 子) forming a specific if not marginal subgroup within their ranks. In this light, I propose that this particular Zhuangzian joke holds significant political and cosmological implications, representing a humorous subversion. To elaborate, Roel Sterckx’s work reveals that early Chinese literati were not keen on comparing themselves to quails. Instead, they preferred to liken themselves to fabulous mythical creatures such as the phoenix and the dragon (

Sterckx 2002, pp. 86–87, 153–58, 181–86). These comparisons, in turn, appear to relate to what Yuri Pines defines as “the lofty self-image of the

shi” (

Pines 2002, p. 116) and specifically to the fact these individuals “succeeded in identifying themselves as “possessors of the Way”, namely, as the intellectual and moral leaders of the society”. (

Pines 2002, p. 116). As Pines mentions, this identification took on different dimensions: ethical, political, and cosmological (

Pines 2002, p. 125). Pines focuses on the ethical and political dimensions, paying rather little attention to the cosmological one. However, I believe the cosmological and metaphysical dimension should be further emphasized: For many

shi, exclusive access to the Way (

dao 道) implied a privileged cosmological and metaphysical status and even exclusive access to the very forces that grounded the operations of the cosmos. In fact, the

shi–mythical animal analogy seems to suggest as much. As noted, the dragon’s ever-shifting form symbolized the process of cosmic transformation itself. Significantly, Sterckx explains that “the discourse on changing animals hence provided a model of intellectual authority that pictured the understanding of change as the highest accomplishment of the sage-ruler” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 177). That is, often times claiming to be a possessor of the Way implies claiming to be a knower of cosmic transformations. Accordingly, “the expression ‘to transform like a dragon’ (

long bian 龍變) also provided an epithet for sagehood, authority, and encompassing virtue” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 179). Yet another Mawangdui text,

Yizhiyi 易之義 (“The Significance of the Changes”), describes the sage in a very similar way:

Confucius said: “The sage is trustworthy indeed. This is said of shading one’s culture (wen) and keeping tranquil, and yet necessarily being seen. If the dragon transforms seventy times and yet is not able to lose its markings (wen), then the markings are trustworthy and reach the virtue of spiritual brightness.”

This text suggests that the cultural shading of the sage parallels the cosmic transformations and spiritual power of the dragon. As Sterckx suggests, this and several other texts play with the semantic ambiguity of the term

wen 文, meaning both “cultural pattern” and “decorative arrangement”, in order to highlight the similarities/parallels between the virtuosity of the sages and the fabulous appearance of dragons (

Sterckx 2002, pp. 156–58, 181–83). In this sense, the sage’s identification with the dragon implies an identification with the numinous forces driving the operations of the cosmos. But such identification was not restricted to the dragon, applying as well to other “numinous animals” (

shen ling 神靈), namely the phoenix/simurgh, the unicorn (

qilin 麒麟), and the turtle. What these “four numinous animals” (

si ling 四靈) had in common was a composite and all-encompassing physical constitution that integrated different body parts from various animals within a “species” into a single body (

Sterckx 2002, p. 178). For example, “a classical description of the unicorn held that it had ‘the body of a deer, the tail of an ox, and a horn on its round crane’.” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 178). Logically, this parallels the abovementioned description of the dragon as a fish–bird hybrid. Overall, these depictions of numinous animals suggest the idea of cosmic totality: The fabulous and bizarre physique of these mythical creatures can or perhaps should be seen as miniature reproductions of the varied components of the cosmos itself. Relatedly, these hybrid bodies imply the capacity to adapt to different circumstances. Through their comparison with these numinous creatures, the sages asserted their ability to embody cosmic totality and unmatched adaptability. They portrayed themselves as possessing the capacity for both universality and adaptivity, submitting that they could harmonize with the ever-changing cosmos and adapt seamlessly to various circumstances. In this sense, Sterckx notes that “if numinous power among animals was identified with the ability to metamorphose, transcend one’s habitat, and respond to changing circumstances, these were precisely the features associated with the human sage”. (

Sterckx 2002, p. 185).

Besides comparing themselves with the dragon’s capacity to constantly change and thus to embody the very process of cosmic transformation, the sages also presented themselves as replicating the privilege status that the dragon and other fabulous animals enjoyed within the hierarchies of the animal kingdom. More precisely, the sages (a lofty self-description which many

shi appear to have been fond of) identified themselves with “a set of four creatures known as the “four numinous animals” (

si ling 四靈), [which] were considered to be the superior members of the species they represented (hairy, feathered, scaly, and armored)” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 153). The

Mengzi 孟子, for example, suggests as much when stating the following:

麒麟之於走獸,鳳凰之於飛鳥,太山之於丘垤,河海之於行潦,類也。聖人之於民,亦類也。出於其類,拔乎其萃,自生民以來,未有盛於孔子也。

(Gong Sun Chou I公孫丑上 2)

“There is the unicorn among quadrupeds, the phoenix among birds, the Tai Mountain among mounds and hills, and rivers and seas among rain-pools. Though different in degree, they are the same in kind. So, the sages among mankind are also the same in kind. But they stand out from their fellows, and rise above the level, and from the birth of mankind till now, there never has been one so complete as Confucius.”

These analogies situated both the sages and the numinous animals (

ling) at the top of a hierarchy: Just as the sages ruled over the commoners, the

ling ruled over their respective “species” (

Sterckx 2002, pp. 153–54). Although this

Mengzi passage compares just two

ling with the sages, other texts mention all four

ling and describe both these and the sages as “essences” (

jing 精) of a particular group of “animals” (

chong 蟲). The following

Dadai Liji 大戴禮記 passage is a case in point:

毛蟲之精者曰麟,羽蟲之精者曰鳳,介蟲之精者曰龜,鱗蟲之精者曰龍,劳蟲之精者曰聖人;龍非風不舉,龜非火不兆,此皆陰陽之際也。玆四者,所以聖人役之也

(Zhengzi Tianyuan 曾子天圓 5)

“The essence of the feathered animals is called the unicorn, the essence of the winged animals is called the phoenix, the essence of the armored animals is called the turtle, the essence of the scaly animals is called the dragon, the essence of the naked animals is called the sage; without wind the dragon cannot fly, without fire the turtle cannot produce omens, all these are at the intersection of the yin and yang. These four, therefore, are the servants of the sages.”

This passage clearly reflects the framework described above: The sage (

shengren 聖人) presides over humans just as the numinous animals preside over regular animals. According to this particular passage, the phoenix rules over winged (

yu 羽) animals, including doves and quails, and the dragon over scaly (

lin 鱗) animals, including fishes and reptiles. It should be noted, however, that not all texts draw such a stark differentiation between numinous animals and the “species” over which they rule. For instance, the

Huainanzi, while explaining the origin of animals, presents an alternative view by stating that the phoenix is born from the Flying Dragon and the Leviathan from the Scaly Dragon (

Sterckx 2002, p. 84). This framework establishes a kinship relationship between numinous birds and dragons, a crucial aspect not mentioned in the abovementioned

Dadai Liji passage. Regardless of the specific nature of the relationship between these

ling creatures and the “species” they oversee, various Warring States and early Han texts consistently position them as rulers over regular animals. Consequently, they are regarded as sharing the same hierarchical standing as the sages, who govern humans or “naked animals” (

luo chong 劳蟲). Furthermore, the passage in question seems to suggest that this consonance entails that the

ling are the “servants” (

yi 役) of the sages. In other words, the sages were responsible for what Sterckx terms “the domestication of the four sacred animals” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 153), a notion that is similarly echoed in the

Liyun 禮運 chapter of the

Liji, which states that “when the sages established rules, they thought it necessary … (to rear) the four sacred animals as their domestic animals” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 153). Given that each

ling ruled over a particular “species”, this act of domestication, in turn, implies the sagely ability to control the entirety of the animal kingdom. Thus, the subsequent part of this same

Liji passage explains how the sage’s ability to tame the numinous animals grants them control over the creatures subject to their rule. It is said, for example, that “if one takes the phoenix as a domestic animal, birds will not fly off in distress” (quoted in

Sterckx 2002, p. 153). However, the sage’s control of animate beings was not merely restricted to the realm of animalia, possessing greater cosmic implications. As Sterckx also explains, the image of sagely control over numinous animals or “hybrids” was repeatedly used as an analogy for the sages’ capacity to effectively control the entirety of the cosmos. In this sense, “hybrids, like their normal animal counterparts, were perceived as part of a spirit geography rather than as members of an autonomous bestiary”. (

Sterckx 2002, p. 156). Moreover, the taxonomy of the five kinds of animals (feathered, winged, armored, scaly, and naked) within which the

si ling categorization was placed was part and parcel of the cosmology of the five phases (

wuxing) that “related the animal world to the phenomena in the cosmos at large” (

Sterckx 2002, pp. 78–79) and which manifested a systematic tendency to categorize animals and, in fact, everything in the cosmos in terms of their broader implications in the realms of the socio-political and moral, thus refusing “to view the animal world as a separate sphere of knowledge” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 79). Logically, according to this rationale, to claim to be able to classify and tame animals is to claim to be able to classify and tame the cosmos. In this sense, the self-description of the sage as a domesticator of animals and particularly as a tamer of dragons was intimately tied to the self-perception of the scholar-official (

shi) as a knower of the cosmos and a controller of its forces and fluxes.

3 That is, these self-accounts pertain to a cosmological framework that assumes the existence of a fundamental “dialectic between officialdom and the maintenance and control of the natural world and its living species” (

Sterckx 2002, p. 54).

The present work employs the concept of “tamable dragons” to describe a fundamental assumption prevalent in both this and other cosmologies of the Warring States period. This assumption posits that the cosmos is entirely knowable, particularly to the scholar-official/sage. Accordingly, we propose that the shi’s belief in their exclusive ability to comprehend and control the cosmos, asserting that dragons can and should be tamed, was a significant source of their inflated self-importance. Simultaneously, we argue that the Zhuangzi’s skepticism should be regarded as a critique of this specific type of knowledge claim, that is, the shi’s claim to absolute knowledge of the cosmos and their self-perception as definitive cosmic knowers. To be more precise, we submit that the Zhuangzian critique of shi knowledge and identity is chiefly conveyed through a series of cosmological subversions. The first of these subversions pertains to the status of the sage within the hierarchical cosmological and zoological equivalences described above. In fact, it is significant to note that, as the reader might have gathered from the above, the Xiaoyaoyou, and particularly its Kun–Peng story, features many of these correlations.

To clarify, the story introduces the phoenix–bird correlation in the form of the dove or quail that sees the humongous Peng bird flying up to the skies.

4 However, this particular story possesses a unique feature: It subverts the inherent hierarchy within said correlation. That is, in this passage, the figure of epistemic authority is not the Peng bird but the pigeon or quail. In fact, this little bird is depicted as claiming to possess knowledge/wisdom: Let us highlight the fact that the first little bird mentioned is not just a dove but a “studying dove” (

xue jiu 學鳩), as noted by Ziporyn (

Ziporyn 2020, p. 4, n. 4). So confident is the little bird of its status as a knower/sage that it even ridicules the Peng bird, laughing at its enormity and questioning its very desire to fly so very high: “What’s all this about ascending ninety thousand miles and heading south?” says the dove; “where does he think he’s going?” asks the quail (

Ziporyn 2020, p. 4). Contrary to the cosmological framework explained above and that, as Sterckx suggests, is also to be found in various other early Chinese texts, here, the center of attention is not the phoenix but the quail/pigeon. In this sense, the story effectively reverses the traditional hierarchy associated with this correlation. But this subversion is double. According to the traditional framework, we should continue flying with Peng and then assist a comparison between this fabulous bird and the lofty scholar-sage. However, the text supplies the exact opposite of that: It compares the scholar-sage not with the lofty Peng but with the lowly pigeon. Once more, this forcefully subverts the structure of authority tied to this correlation. Now the

shi is situated at the bottom of the phoenix–bird hierarchy; he is paired not with the ruler but with the ruled. Logically, this comparison does not seem to sit well with the scholar’s “strong sense of self-respect” (

Pines 2002, p. 121). To the contrary, such an analogy necessarily undermines one of the main sources of the

shi’s high self-regard: the notion that the scholar is capable of knowing and taming the forces of the cosmos and that he should therefore be compared not with a pigeon or a quail but with a dragon or a phoenix. In this sense, by comparing the scholar with a pigeon/quail, the

Zhuangzi has effectively subverted the cosmological standing of the

shi.

But what does this cosmological subversion entail? Besides the undermining of the lofty comparisons with fabulous mythological creatures behind the scholar’s inflated self-esteem, what else could the author(s) of the

Xiaoyaoyou be aiming at? In other words, what else defined the lofty self-perception of the scholar as a knower of the cosmos, and what kind of cosmological knowledge did scholar/officials claim to have? I think an answer to this can be found in the stanzas immediately following the abovementioned description of the

shi:

而宋榮子猶然笑之。且舉世而譽之而不加勸,舉世而非之而不加沮,定乎內外之分,辯乎榮辱之竟,斯已矣。彼其於世,未數數然也。雖然,猶有未樹也。

(Xiaoyaoyou 3)

“Even Song Rongzi would burst out laughing at such a man. If the whole world happened to praise Song Rongzi, he would not be goaded onward; if the whole world condemned him, he would not be deterred. He simply made a sharp and fixed division between the inner and the outer, and clearly discerned where true honor and disgrace reside. He did not involve himself in anxious calculations in his dealings with the world. Nevertheless, there was still a sense in which he was not really firmly planted.”

According to our reading, Song Rongzi’s potential ridicule of the

shi serves to confirm the

Zhuangzi’s mockery of these characters: Not only are men in office comparable to doves, but also they deserve to be laughed at in the same way they themselves laugh at the immense and fabulous Peng bird. Song Rongzi, it is suggested, would do just as much if he were to witness such a pathetic spectacle. In doing so, he would also detach himself from one of the

shi’s major fixations: the search for praise (

yu 譽), which parallels the previous stanza’s reference to “deeds” (

xing 行), “virtues” (de 德), and the desire “to prove oneself” (

zheng 徵). It is further explained that what grounds Rongzi’s detachment is his ability to distinguish between “the inner and the outer” (

neiwai 內外) and “honor and disgrace” (

rongru 榮辱). But it appears Rongzi did not go far enough in his disentanglement from the

shi worldview, as the stanza complains that he is “not really firmly planted” (

weishu 未樹) This criticism seems to be the background of the passage’s subsequent praise of Liezi:

夫列子御風而行,泠然善也,旬有五日而後反。彼於致福者,未數數然也。此雖免乎行,猶有所待者也。

(Xiaoyaoyou 3)

“Now Liezi got around by charioting upon the wind itself and was so good at it that he could go on like that in his cool and breezy way for fifteen days at a time before heading back. He was someone who didn’t involve himself in anxious calculations about bringing the blessings of good fortune upon himself. Nevertheless, although this allowed him to avoid the exertions of walking, there was still something he depended on.”

The stanza seems to suggest that Liezi’s supernatural capacity to “chariot upon the wind” (

yufeng 御風) is proof of a kind of detachment from scholarly preoccupations even greater than Rongzi’s: If Rongzi detaches himself from the search of praise, Liezi frees himself from the very desire to acquire “the blessings of good fortune” (

fu 福). Such is his freedom that he is then able to fly, either actually or metaphorically. And even so, Liezi’s flying is deficient in the sense that it still “depends upon” (

dai 待) something, presumably the wind. Thus, just as Rongzi is “not really firmly planted”, Liezi is still “dependent on” the wind. The passage then proceeds to describe a person that avoids these limitations and achieves true independence.

5 However, before we turn to that description, let us emphasize that, although both these masters, Rong and Lie, are criticized for their shortcomings, they are praised for their ability “not to involve themselves in anxious calculations” (

wei shushu ran ye 未數數然也). Although this intriguing assertion is often overlooked, I believe it holds significant implications for assessing both these masters and those from whom they are distinguished, namely the

shi. In line with the focus of the present work, my attention shall focus particularly on the latter task. To explain, considering that both of these masters are defined in contradistinction to the involvement in “anxious calculations” (

shushu 數數), as suggested by the use of the grammatical particle

wei 未 in the abovementioned expression, I suspect that, for the author(s) of the

Xiaoyaoyou, precisely what defines the

shi is such involvement. In other words, according to this reading, the passage seems to imply that just as the disengagement from “anxious calculations” characterized the masters Rong and Lie, the participation in “anxious calculations” distinguished the scholar/official. The elucidation of this matter will logically ensue from the following question: What could

shushu 數數, rendered by Ziporyn as “anxious calculations”, refer to? And more precisely, what role could this activity have played in the self-perception of the

shi as a cosmologist?

6. Tracing the Contours of a Pun: On the Meaning of Shushu

The term

shushu 數數 does not occur elsewhere in the

Zhuangzi, appearing exclusively in its

Xiaoyaoyou chapter. While the term might seem straightforward, it deviates from its usual meaning in this particular context. Typically,

shu 數 simply denotes “number” or “several”, and it is used in these conventional senses in various other parts of the

Zhuangzi.

6 However, the

Xiaoyaoyou uses the term as both an adverb and a verb, as evident from Ziporyn’s rendition. Richard John Lynn also provides a similar translation, describing Song Rongzi’s behavior as follows: “he was never anxious and calculating in regard to the world” (

Lynn 2022, p. 8). Both translations align with the commentarial tradition and are, to the best of my knowledge, accurate. It is worth noting, however, that most translators opt for different renderings of

shushu, avoiding the terms “calculation” or “calculating”. For instance, A.C. Graham translates it as “too concerned” (

Graham 1989, p. 44), Burton Watson as “fret and worry” (

Watson 2013, p. 3), and Victor Mair as “worldly affairs” (

Mair 1994, p. 5).

7 In this way, many English-speaking specialists prefer to translate the term as denoting something akin to “anxiety”, as in Ziporyn’s and Lynn’s renditions. This emphasis seems to be a reflection of the commentarial tradition, which also places significant importance on this aspect of the expression

shushu. For example, according to Guo Qingfan’s 郭慶藩

Zhuangzi Jishi 莊子集釋, Sima Biao 司馬彪 and Cheng Xuanying 成玄英 concur in rendering the expression as

jiji 汲汲, meaning “anxious”, “avid”, or “eager” (

Guo 1985, p. 18) Relatedly, Guo glosses Cui Zhuan 崔譔 as saying that “[

shu] means ‘to be in a hurry’ [迫促意也]” (

Guo 1985, p. 19). According to Wang Shumin’s 王叔岷

Zhuangzi jiaoquan 莊子校詮, Lu Deming’s 陸德明

Jingdian Shiwen 經典釋文 highlights the latter rendition when stating that “according to Cui [Zhuan] and Xiang [Xiu],

su 速 is written shu. That is, this is proof that

shu and

su are used interchangeably [速,向,崔本作數. 卽數, 速通用之證]” (

Wang 2007, p. 19).

8 The character

su can be translated variously as “quick”, “hasty”, or “in a hurry”. Finally, as per Wang Xianqian’s 王先謙

Zhuangzi Jijie Neipian Buzheng 莊子集解内篇補正,

shushu should be read as

fenfen 分分, meaning “busy” (

Wang 1987, p. 12).

9 In sum, the commentarial tradition establishes three primary meanings for

shushu: “anxious”, “hasty”, and “busy”.

10 As it is apparent, the translations of the term by the abovementioned Anglophone scholars are in keeping with these glosses.

And yet, as suggested, these renditions do not exhaust the meanings of

shu, which can also be rendered as “calculation” or “calculating”. The basis for this reading seems to be based on an often-forgotten commentator, namely Emperor Liang Jianwen 梁簡文帝 (503–551 AD),

11 who, according to Guo Qingfan, glosses that “[

shu] is the phonetic combination of

suo and

yu, meaning to calculate [簡文所喻反, 謂計數]” (

Guo 1985, p. 19). What I, following Ziporyn, translate here as “to calculate” is

jishu 計數. However, the

Hanyu Dacidian 漢語大詞典 suggests that this term can be more specifically rendered as “arithmetical calculation” (

jisuan 計算) or “strategic foresight and political craftsmanship” (

moulue quanshu 謀略權術) (

Luo 1997, p. 6515). Similarly, Christoph Harbsmeier’s TLS translates

jishu as “(statistical) calculations” and as “[to] exercise (statistical) calculations”, in both cases providing a parenthesis that adds “as part of a proper bureaucratic planning exercise”, thus suggesting that this is the specific context in which these calculations take place.

12 In sum, both dictionaries concur in highlighting the bureaucratic and mathematical dimension of the term

jishu. I believe that these references provide invaluable insights into comprehending the term

jishu in Emperor Jianwen’s commentary and, consequently, help clarify the meaning of

shushu in the

Xiaoyaoyou. It becomes apparent that by translating

shushu as

jishu, Jianwen intended to denote not only general calculations but specifically arithmetical and/or statistical calculations relevant to state administration and political maneuvering. This is powerfully suggested by the definition of

jishu as

moulue quanshu. In fact,

moule can also be rendered as “stratagems and schemes”, a concept that highly resonates with the political reality of the Warring States, which implies that the survival of a state was predicated upon its capacity to successfully calculate the outcome of a political and/or military move performed either by itself or a competing state. These, in fact, are the calculations we find in the historiographical accounts of texts like the

Chunqiu Zuozhuan 春秋左轉, the

Guoyu 國語, or the

Zhanguoce 戰國策; furthermore, at the center of these stratagems were situated the scholars/officials of the time. On the other hand, alternatives renditions of

quanshu 權術 are “method for the exercise of authority” or “technique for the use of power”.

13 A less literal translation would be “political craftmanship” or “the arts of politics”, that is, the various skills and strategies involved in the successful practice of politics and governance, including the ability to navigate complex social and governmental structures, make informed decisions, negotiate, and maintain stability within society. These abilities comprehend, of course, the responsibilities of a ruler, a person in charge of leading a state, but also and perhaps most notably the duties of a scholar/official, a regular member of the government apparatus, and a person in charge of ensuring that the finer machinery of the state administration runs smoothly. The survival of this person within the state machinery and his capacity to maneuver through the often dangerous if not deadly intricacies of its operations depend as much or even more than the ruler on the mastery of specific “methods” or “skills” (

shu 術), particularly those relating to the successful performance of different kinds of calculations aimed at ensuring not only the ruler and the state’s survival, but also the scholar-official’s personal survival, primarily by quelling the anxieties deriving from his responsibilities.

On the basis of the above analysis and particularly concerning the far-reaching implications of the various parallelisms between calculations, methods, and strategies that it reveals, I propose the hypothesis that

shushu 數數 should be read as a Zhuangzian pun for

shushu 術數, a term variously translated as “calculations and arts” (

Harper and Kalinowski 2017, pp. 5, 85–86, 95, 108, 273;

Harper 1999, pp. 822–25, 841, 867), “calculations and techniques” (

Lagerwey 2019, p. 47), and “numbers and techniques” (

Michael 2015, p. 123;

Raphals 2013, p. 32;

Lackner et al. 2020, pp. vii–viii, xiii). As Donald Harper explains, this term refers the disciplines of “astrology, hemerology, medicine, and other arts [that] were of immediate consequence in the pattern of daily life [in early China]” (brackets are mine,

Harper 1999, p. 825). Accordingly, Harper labels this corpus as “natural philosophy and occult thought” and notes that “at Warring States courts and among the elite generally, the applied knowledge of the natural experts and occultists was valued as much as the speculations of the masters of philosophy” (

Harper 1999, p. 825). Furthermore, he suggests that “were one to reconstruct the worldview of the Warring States elite based solely on the evidence of the tombs excavated to date, ideas related to natural philosophy and occult thought would occupy a prominent place—more prominent than would result from a reconstruction based on the received record, particularly were that record to be narrowed down to the writings attributed to the masters of philosophy” (

Harper 1999, p. 820). In essence, according to the archeological record, the

shushu corpus held more influence and sway in the courts of the Warring States than the

zishu 子書 corpus. Hence, within the ranks of the state apparatus of the Warring States polity, scholar/officials with roles as astrologers, hemerologists, diviners, and physicians held greater intellectual authority and political prominence than their counterparts in the role of philosophers.

14 This not only confirms the intimate connection between the

shushu and the individuals responsible for managing the state apparatus (i.e., the

shi) but also clarifies the precise role that “calculations and methods” played in the

shi’s self-perception as a knower of the cosmos and its operations. As Donald Harper and Marc Kalinowski have shown, the

shushu were, first and foremost, forms of cosmological and metaphysical knowledge, particularly in the case of astrology and hemerology, but also with regard to medicine and divination (

Harper 1999;

Kalinowski 2004,

2009;

Harper and Kalinowski 2017).

7. Shushu Cosmologies: “Coming and Going in the Service of the King”

To be precise, the

shushu corpus was composed of cosmic boards (

shi 式), day-books (

rishu 日書), divinatory manuals, and a series of similar numerological and arithmetical devices that, by relying on specific astronomical/astrological frameworks, furnished scholars with the means necessary to provide highly precise predictions to and diagnoses of a variety of different situations. We get a glimpse of the use of these calculations and frameworks in passages from received texts, such as the following passage from the

Chunqiu Zuozhuan:

“The king of Zhou asked [his astrologer] Chang Hong: “Among today’s princes, who will have good or ill fortune?” He obtained the following reply: “Ill fortune will strike the prince of Cai. Jupiter is stationed now in the Shiwei mansion which is that of the year [12 years ago] when the present prince, Ban, had the preceding prince killed. Before the cycle is finished, Chu will take possession of Cai and will reach the height of its iniquities. [In two years], when Jupiter crosses the Daliang mansion, Cai will get back his land and Chu, in its turn, will know misfortune”.”

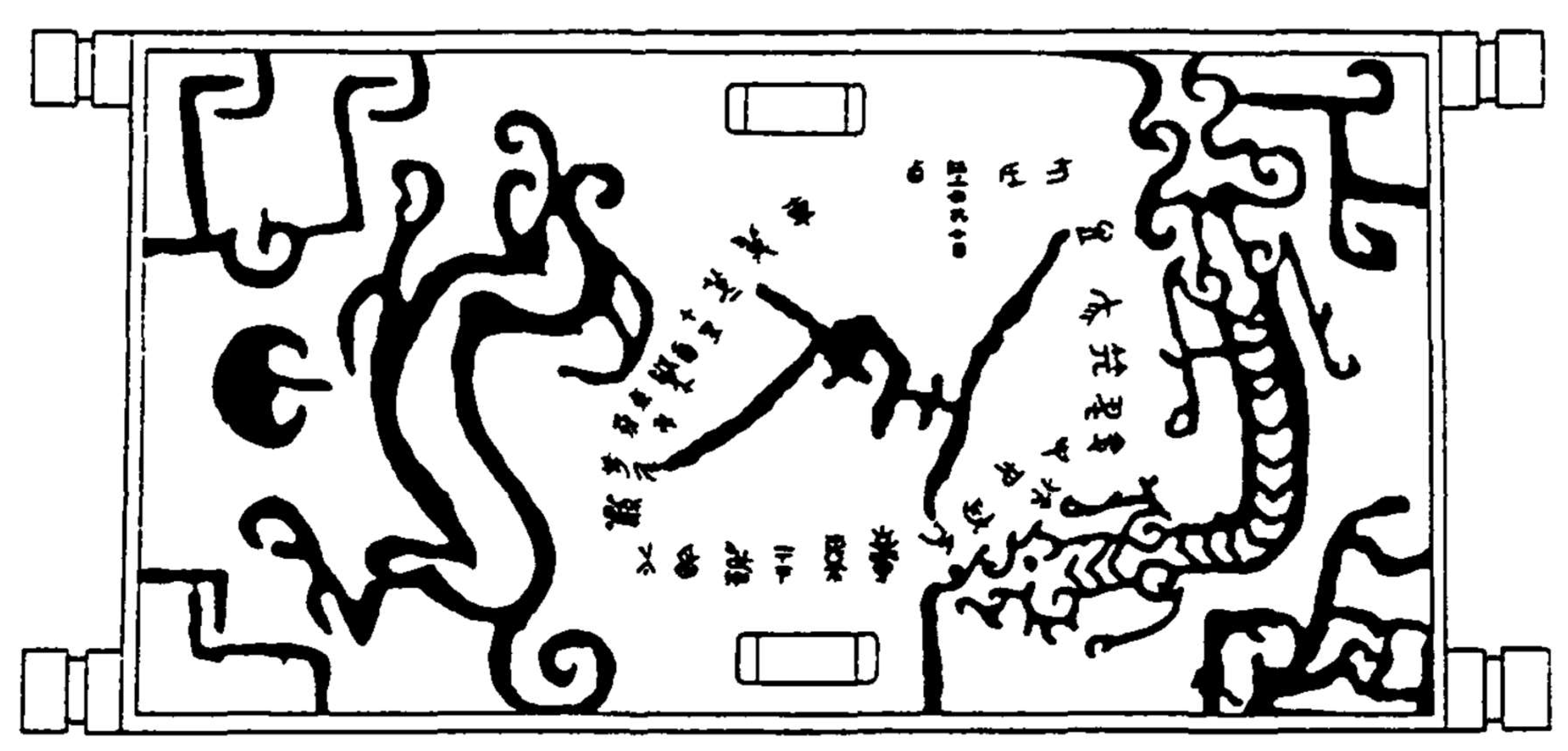

As per this passage, the prediction of good or ill fortune relies on determining the position of a celestial body, namely Jupiter. Harper explains that Jupiter’s location was calculated by using an arithmetical system known as the sexagenary cycle in accordance with an astronomical and astrological framework known as the twelve “earthly branches” (

dizhi 地支), the ten “heavenly stems” (

tiangan 天干), and the “twenty-eight stellar lodges” (

ershiba xiu 二十八宿) (

Harper 1999, pp. 820, 833–36).

15These elements were combined to form the “Day Court” (

riting 日廷) diagram (see

Figure 2), also known as the “cord-hook” (

shenggou 繩鉤) diagram (

Harper 1999, pp. 836–38,

Kalinowski 2017, p. 162). The cosmological nature of this framework and the calculations it furnishes need not to be stated. But three aspects are worth mentioning. First, it is a framework built upon the assumption that the structure and flow of the cosmos can be established with almost absolute precision. In fact, it not only specifies lunar and solar cycles (according to branches and stations, respectively), but it also stipulates years, months, days, hours of the day, and cardinal directions (Harper 836). Second, it is a framework that is applied primarily to political and administrative matters. In this particular case, the preoccupation of both the king and the diviner is not simply good or ill fortune but specifically good or ill fortune “among today’s princes”. Accordingly, the divination rapidly turns into political commentary and interstate strategizing. The cosmological calculations, i.e., omens, serve the intricacies of statecraft, assigning both astronomical and geopolitical significance to events like Cai’s misfortune, Chu’s conquest of Cai, and Cai’s counterattack against Chu 楚. Third, the inquiry made by the Zhou king to his diviner at court carries a certain element of anxiety, and it appears that the divination was specifically designed to ease this unease or worry. Before we continue to analyze these aspects, it should be noted that, as suggested by Harper, the received record is largely silent with respect to the astro-cosmological described above (

Harper 1999, pp. 818–19). The

Zuozhuan, in fact, provides only occasional evidence of it. This would appear to confirm Yuri Pines’ hypothesis that, according to said text, the courts of the Spring and Autumn period granted increasingly less importance to the advice of astronomers and diviners (

Pines 2002). However, as Harper also indicates, the archeological record of the Warring States period seems to offer a rather different picture, one wherein the abovementioned framework occupies a central position in the state administration. A good example of that is the case lid of the lacquer clothes case of Marquis Yi of Zeng’s 曾侯乙 (d. ca. 433 BCE) tomb, which details the twenty-eight stellar lodges (

Harper 1999, pp. 833–34).

The drawing on this lid directly connects said astro-cosmological scheme with a very important element of a particularly sumptuous tomb of a high-ranking official of the Warring States period (see

Figure 3). But specifically in reference to the Warring States period, an even more veritable body of evidence for the pervasiveness of

shushu cosmology is found in a series of excavated manuscripts known as “daybooks” (

rishu) or “daybook related manuscripts”. It is through these hemerological and divinatory manuscripts that we are able to acquire a more precise understanding of the specific way in which this astro-cosmological framework determined the management of state affairs. In this vein, Kalinowski comments that “the excavated documentation fills a gap and permits us to situate

shushu traditions in a cultural context that is…. more socially representative” (

Kalinowski 2004, p. 228). This relates to the fact that, as Liu Lexian notes, daybooks are “focused on maximizing positive outcomes in everyday life and shows little interest in large-scale political and military affairs” (

Liu 2017, p. 65). Although uninterested in major politico-military matters, daybooks and related hemerological texts are still very much related to administrative issues, detailing the manner in which astro-cosmological systems like the sexagenary cycle were used to predict and handle the minutia of the daily lives of the scholar-officials of the time, that is, of the individuals in charge of running the existing state apparatus.

16 In this respect, the manuscripts excavated in various tombs of the Chu kingdom are highly relevant. Unfortunately, the deteriorated condition of most of these manuscripts does not allow for a detailed reconstruction of the cosmological beliefs of the time. We find, however, a notable exception in the Baoshan 包山 bamboo manuscript, which, as Kalinowski notes, “is the most interesting, for it is the only one which has been restored with a good degree of certainty to its original state” (

Kalinowski 2009, p. 375). This daybook-related manuscript is labeled as a “divination and offering record” (

Harper 2017, p. 106). It registers a series of divinations performed on behalf of Shao Tuo 邵陀 (356?–316 BC),

17 a member of the Chu royal family that held the position of “minister of the left” (

zuoyin 左尹) and served as “a high magistrate in charge of penal affairs” (

Kalinowski 2009, p. 375). Lisa Raphals distinguishes between two kinds of divinations in the Baoshan corpus: “year divinations” and “illness divinations” (

Raphals 2013, pp. 409–10). She defines the formulaic structure of the former as follows:

“自 X 之月以庚 X 之月,出入事王, 盡卒歲,盡集歲躬身尚毋又(有)咎”。

“From month X [this year] to month X of next year, for the whole of the year, coming and going [lit. exiting and entering] in service to the king, for the entire year, may his [physical] person de without calamity.”

It is interesting to note that the divinatory consultations regarding Shao Tuo’s ability to avoid “calamity” (

jiu 咎) were made specifically in reference to his “coming and going in the service of the king” (

churu shiwang 出入事王). According to the specialized literature, the divinatory record mentions three such year divinations, detailing the names of eleven different diviners, the particular divination method (turtle or yarrow), and the specific day in which the divination was performed according to the sexagenary cycle (

Kalinowski 2009, pp. 376–77). However, this formulaic structure accounts for just the first portion of an annual consultation, the second one being reserved for a description of the sacrificial offerings to be performed in order to quell the concerns of the consultant. The annual divination for the year 318 is as a good example:

宋客盛公邊聘於楚之歲,刑夷之月,乙未之日,石被裳以訓黽為左尹佗貞:自刑夷之月以適刑夷之月,盡卒歲,躬身尙毋有咎?占之,恒貞吉,少外有憂,志事少遲得。以其古敓之。翌禱於邵王,戬牛,饋之。翌禱文坪夜君、邵公子春、司馬子之音、蔡公子家,各戬豢,酒食。翌禱於夫人,戩腊。志事速得,皆速賽之。占之:吉,享月、夏夕有喜。

“During the year when the Song guest, Sheng Gong Bian, paid an official visit to Chu, on the month Xingyi [first month of the year], the day Yiwei [32nd day of the sexagenary cycle], Shi Beishang prognosticated for zuoyin [minister of the left] Tuo using the xunmin [docile turtle] method: From Xingyi month up to the next Xingyi month, by the end of the year, has his person not incurred any (spiritual) blame? (Shi Beishang) divined about it: the long term prognosis is auspicious, yet it seems that (his affairs) outside are in trouble and what he aimed to accomplish has been slow to come about. (Shi Beishang) performed an exorcism to get at its source. (Shi) performed secondary prayers to King Zhao with a black water buffalo and set it out as a food offering. (Shi) performed secondary prayers to the Accomplished Lord Pingye, Chun of the Sire Wu line, Yin of the Sima line, Jia of the Sire Cai line with a black gelded pig for each and with wine and food. (Shi) performed secondary prayers to (Shao’s father’s) wife with [sacrificial] dried meat from a black pig. If (Shao’s) intended matters are quickly achieved, all (sacrifices) will be quickly repaid. (Shi) divined about it (saying): ‘Auspicious. During a Xiangyue [third] or a Xiaxi [forth] (month), there will be happiness.‘”

This record testifies to the fact that Shao Tuo seeks the services of a diviner (in this case, Shi Beishang 石被裳) because “(his affairs) outside are in trouble and what he aimed to accomplish has been slow to come about” (少外有憂,志事少遲得). What Cook translates as “in trouble” is

you 憂, which can also be translated as “worry”. Thus, the first part of this stanza could be rendered as “outside there are worries”. In this sentence, as Cook suggests,

wai 外 seems to refer to the “outside world”, that is, Tuo’s outside world. More precisely, Tuo’s worries are centered around “what he aimed to accomplish” (

zhishi 志事), or his “intended affairs”, which have been “slow to come about” (

chide 遲得). In essence, Tuo is troubled by the lack of progress in his affairs and seeks the diviner’s help in resolving these issues. The diviner’s response is highly technical, prescribing a specific number of rites and sacrifices that are said to ensure that the outcome is “auspicious” (

ji 吉) and that “blame” or “calamity” (

jiu) is avoided. According to Kalinowski, these sacrifices were intended for Tuo’s ancestors, including the former King Zhao of Chu. Although the divination does not explicitly state the particular matter troubling Tuo, it is likely related to his duties as a magistrate. As previously mentioned, the Baoshan manuscripts explicitly address Tuo’s health concerns in certain divinations, earning them the designation of “illness divinations” by Raphals. One of these divinations commences as follows:

傍腹疾,以少氣,尚毋又(有)咎。占之,貞吉,少未已,以其古(故)祝之。 薦於野地主 豭,宮地主 豭,賽於行 白犬、酒食,占之曰:吉,刑尸 且見王。

“There is an illness near the abdomen with shortness of breath; may there be no calamity. He prognosticated about it: the prognostication is auspicious; it is slight but it has not stopped; get rid of it according to its cause. He made offerings: one billy goat to the Lord of the Wild Lands, one billy goat to the Lord of the Grave. He performed sai [repayment] sacrifice to the Lord of the Path [Xing] with one white dog and wine oblations. He prognosticated about it: it is auspicious. In the month xingyi he [Shao Tuo] will have an audience with the king.”

Once again, the diviner’s response to Tuo’s concern involves performing divinatory prognostications and sacrifices. As in the previous divinatory record, the presages are said to be “auspicious” (

ji), but unlike those records, the sacrificial offerings are directed not to ancestors but to territorial gods: The Lords of the Wild lands, the Grave, and the Path. Additionally, it is mentioned that Tuo will have an audience with the king, a seemingly unrelated matter to the issue of illness. However, Constance A. Cook explains that these two aspects could be interconnected, as “Shao Tuo’s spiritual blame likely occurred through his administrative duties to the Chu king. He often had to try criminal cases and may have been responsible for the capital punishment of innocent victims. As a minister of state, he… was concerned with wiping out blame for human death. His job… probably involved a great deal of travel, and in the course of dealing with local cases, he may also have offended nature deities. The Chu divination text recorded the sacrifices to a number of deities [like the Lords of the Wild lands, the Grave and the Path], all of whom may have cursed a passerby” (brackets are mine,

Cook 2006, p. 82). Thus, Tuo’s constant “comings and goings in the service of the king” might have been the cause of his anxieties, particularly as fulfilling his duties as a magistrate most likely entailed becoming the target of hatred from those he inspected or prosecuted. In early China, as these sources suggest, such hatred could take the form of supernatural forces (

Yan 2017).

Accordingly, the illness divination, just like the year divination mentioned earlier, seems designed to effectively alleviate these anxieties not only by providing highly precise sacrificial instructions but also and perhaps most importantly by offering auspicious prognostications. In this regard, Kalinowski comments that the final predictions of the Baoshan divinatory records are “rather encouraging and always positive… [and in general] the narrative structure of these records is… not only very brief but also extremely stereotyped and common to all existing records…” (bracket is mine,

Kalinowski 2009, p. 381). In other words, the Baoshan turtle and yarrow oracles “function within a complex religious system in which the cult of the ancestors and gods

guarantees the consultant an auspicious future in accordance with his hopes. The aim of the divination is not so much to predict the future as

to define and control the ritual protocols of prayer and exorcism which accompany the consultants’ requests” (cursives are mine,

Kalinowski 2009, p. 381). That is, these divinations rest upon a worldview where the future, along with the functioning of both human and non-human forces, is almost entirely predictable and controllable. The role of the mantic specialist is merely to offer the appropriate ritual practices that uphold this notion, ensuring that the cosmic order remains in harmony and that the consultant’s desired auspicious future is secured.

In summary, similar to the case of the aforementioned

Zuozhuan divination, the cosmology of the Baoshan oracles is grounded on the premise that the ebb and flow of the cosmos can be ascertained with near-perfect precision. Drawing on the analogy mentioned earlier, it is a cosmology based on the belief that dragons are fundamentally tamable. This belief finds even greater expression in daybooks, “which detail the auspicious or inauspicious nature of daily actions depending on the calendrical signs for each day and the agent or element influencing that day. In these books, while the cause of illness is still a curse, the prognosis is affected by the agent, which influences the days of the illness. In this system a ritualist could calculate the appropriate action for a king or officer according to this complex correlative calendar rather than relying solely on divination methods” (

Cook 2006, p. 86). Notwithstanding, it is important to note that daybook prognoses encompass a wide array of affairs ranging from births and well-digging to marshalling troops. Presented below are selected entries from the Shuihudi 睡虎地 daybooks, focusing on political and administrative matters to align with our current line of inquiry:

陽日,百事順成。邦郡得年,小夫四成。以祭,上下群神饗之, 乃盈志。

“Yang day [no. 2]: All affairs succeed without obstacle. Country and prefecture achieve yearly harvests; ordinary people successful in every way. For sacrifice, above and below all the spirits will be nourished and they will be satisfied.”

陰日,利以家室。祭祀、家子、 娶婦、入材,大吉。以見君上, 數達,無咎。

“Yin day [no. 5]: Beneficial for family matters. Ancestral sacrifice, marrying daughters, taking a wife, bringing in materials: greatly auspicious. For an audience with a superior, many successes and no harm.”

達日,利以行師出征,見人。 以祭,上下皆吉。生子,男吉,女 必出於邦。

“Da day [no. 6]: Beneficial for marshalling troops, marching out the army, audiences with others. For sacrifice: above and below, all auspicious. If a son is born: auspicious, if a daughter, she will be sure to depart from the country.”

The precision of this hemerological framework is assumed to be absolute. There is no doubt as to what constitutes a lucky or unlucky day: The tamability of dragons is not up to question. Indeed, just like in the case of the Baoshan oracles, the predictions furnished by Shuihudi hemerology were calculated by using the sexagenary cycle according to the twenty-eight lunar lodges and the twelve earthly branches (

Raphals 2013, p. 412). In this way, the assumed accuracy of the hemerological predictions was directly based on exact astro-cosmological knowledge or more precisely on the assumption that it was possible to know with absolute precision how the cosmos operated and how these cosmic operations affected the daily lives of individuals, including government officials, as suggested by the mention of “affairs” (

shi 事) like the yearly harvests of countries and prefectures, the audience with superiors, and the marching out of armies. But if these entries mention politico-administrative matters in passing, others make them their main focus of attention. The following entry is a case in point:

凡是有爲也必先計月中閒日苟毋直赤帝臨日它日雖有不 吉之名毋所大害

“Whenever there is something (for you) to do: (You) must first calculate (your) free days during the month. So long as it does not coincide with Red Emperor inspection days, even though the other days are identified as not auspicious, there is not great harm.”

As Harper notes, this hemerological prediction’s “presumptive reader was a man serving in the local administration with government-granted free days (

xianri 閒日) for personal use each month who needed to determine what he could expect to do on these days” (

Harper 2017, p. 117). According to this daybook, the avoidance of “harm” (

hai 害) relied solely on the avoidance of the so-called “Red Emperor inspection days” (

chidi linri 赤帝臨日).

19 There was absolutely no doubt, therefore, as to what was the way to ensure that a scholar-official enjoyed good fortune on his off days. All he needed to do was “calculate” (

ji 計) these days to ensure they did not coincide with an inauspicious day. Once again, the level of cosmological precision that these mantic predictions assumed is truly astonishing. Moreover, this remarkable accuracy was intimately connected to the practice of “calculations”.

9. Coda: Reassessing the Nature of Zhuangzian Skepticism: On the Metaphysical Implications of the Dubiousness of Calculations and the Achievement of Independence

In light of the above, it appears that the Zhuangzi’s skeptical questioning of the possibility of knowledge is specifically directed at the epistemological presuppositions of the cosmological knowledge characteristic of the shushu mantic and astronomical/astrological tradition. If, as several authors have noted, the different perspectives introduced in the Kun–Peng story allegorically refer to the issue of skepticism, then it is reasonable to conjecture that this skepticism targets specific forms of knowledge prevalent in the Warring States period. In this sense, the author of this chapter does not have a problem with knowledge per se but with a particular type of knowledge, namely literary and scholarly knowledge.

Returning to the issue of perspectives, the specific problem with this type of knowledge lies in its lack of awareness of its limitations, its size, and scope. It claims to know more than it actually knows. As demonstrated above, this is suggested by the fact that the main target of criticism in

Xiaoyaoyou 1–3 is the

shi’s presumptuous form of knowledge and identity. In this way, these three

Xiaoyaoyou passages seem determined to accomplish two main tasks: subverting the lofty self-image of the

shi by humorously comparing them with rather unlofty creatures and undermining the forms of cosmological knowledge associated with “scholar-officials” by showing that their “calculations and methods” are, at best, dubious. This interpretation may also shed light on the last stanza of

Xiaoyaoyou 3:

此雖免乎行,猶有所待者也。若夫乘天地之正,而御六氣之辯,以遊無窮者,彼且惡乎待哉!故曰:至人無己,神人無功,聖人無名。

“But suppose you were to chariot upon what is true both to Heaven and to Earth, riding atop the back-and-forth of the six atmospheric breaths, so that your wandering could nowhere be brought to a halt. Then what would you be depending on? Thus I say, the Utmost Person has no definite identity, the Spiritlike Person has no particular merit, the Sage has no one name.”

The cosmological implications of this passage are quite evident: The individual being praised here (variously named as zhiren 至人, shenren 神人, or shengren 聖人) is depicted as riding with Heaven and Earth and mounting the six “atmospheric breaths” (qi 氣), echoing a sense of dragon-like attributes. However, what truly stands out is the remarkable quality of this person, highlighted by the fact that he/she does not “depend on” (dai) anything. As noted above, the persistence of “dependency” was the only hindrance for masters Song and Lie in their departure from the “anxious calculations” of the shi, and it somewhat tainted the text’s celebration of them. In this sense, if dependency implies insufficient disengagement from calculations and their limitations, the achievement of independency is defined by paramount cosmic efficacy and, crucially, the disappearance of defining features of scholar-officials: “definitive identity” (ji 己), “particular merit” (gong 功), and “name” (ming 名). From this portrayal of the Zhuangzian sage, several implications can be inferred regarding the distinct metaphysico-cosmological and epistemological viewpoints that characterize the philosophy of the Zhuangzi, particularly as elucidated in the initial passages of the Xiaoyaoyou chapter.

Regarding the epistemology encompassing Xiaoyaoyou 1–3, it is captivating to note that the concluding stanza of this sequence abstains from delving into the realm of knowledge (zhi). In actuality, the possession of zhi does not feature among the defining attributes of the Zhuangzian sage. Moreover, the diverse array of concepts employed to portray this foundational figure—charioting, riding, and wandering—seemingly lack overt epistemological implications. Simultaneously, notions akin to those connected with knowledge in prior stanzas are explicitly disassociated from the Daoist sage: “dependency”, “identity”, “merit”, and “name”—echoing the ideas of “deed” and “virtue” in the opening stanza of Xiaoyaoyou 3—are aspects the sage forsakes. As proposed, this appears to relate to the dismissal of anything associated with scholar-officials, encompassing their knowledge paradigms. In this context, this stanza seemingly reinforces our conjecture that the chapter scrutinizes “knowledge” with a critical lens, lending credence to the validity of the skeptical interpretation of its content. Nonetheless, as intimated, this skepticism seems to have been directed toward a specific kind of knowledge, namely the astro-cosmological knowledge of the shushu tradition. If this is indeed the case, as it appears to be, then it is plausible to infer that the chapter does not universally reject knowledge but rather specific forms thereof.

In this context, as noted by an anonymous reviewer of this paper, the chapter appears to entertain the possibility that alternative forms of knowledge might hold merit or even be commendable. Under this interpretation, non-

shushu knowledge (or potentially pre-

shushu knowledge) could align with the “greater knowledge” that the chapter notably distinguishes from “lesser knowledge”, which would equate to

shushu knowledge.

Xiaoyaoyou 1 seems to allude to this when it states: “What do these two little insects know? Lesser knowledge cannot keep up with greater knowledge; short duration cannot keep up with long duration [之二蟲又何知!小知不及大知,小年不及大年]” (translation modified,

Ziporyn 2020). This stanza notably implies that the “little insects” or “little animals” (

er chong 二蟲), humorously referring to the cicada and dove from the previous stanza, possess “lesser knowledge” (

xiao zhi 小知). As scholars have underscored, given that the text proceeds to outline a sequence of comparisons between small and large creatures, it strongly hints that large creatures, including the legendary Peng bird, hold “great knowledge”. Presumably, this is the type of knowledge the text endorses. Our analysis appears to support such a conclusion. In fact, considering our previous explanation that the “little animals” correspond to scholar-officials, their knowledge (i.e.,

shushu knowledge) should epitomize “lesser knowledge”. Simultaneously, this suggests that the sage should be likened to the mythical Peng bird, embodying “great knowledge”. However, it is crucial to underscore that, as mentioned at the outset of this paragraph, the text does not explicitly establish this correlation. Strikingly, despite the logical progression such a comparison would entail, the author of

Xiaoyaoyou 1–3 opts not to liken the Zhuangzian sage to Peng or to explicitly reference “great knowledge” as a distinguishing trait. This decision appears to reinforce our hypothesis that this chapter primarily centers on cosmological and metaphysical considerations rather than epistemological or skeptical ones. While acknowledging this, we do not intend to dismiss the fact that in other chapters of the

Zhuangzi, such as the

Qiwulun 齊物論, the possession of exceptional epistemic capabilities is a defining trait of the sage. Our intent is merely to underscore that, in the specific context of

Xiaoyaoyou 1–3, this notion does not hold true.

As indicated, it is noteworthy that the distinguishing traits of the Zhuangzian sage are not presented in terms of epistemology. Instead, these capabilities appear to form a “regime of activity”, to borrow from Jean-Francois Billeter’s expression (