Understanding the Political and Religious Implications of Turkish Civil Religion in The Netherlands: A Critical Discourse Analysis of ISN Friday Sermons

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Varieties of Civil Religion

2.1.1. Type-Case 1: Continued Undifferentiation

Church-Sponsored Civil Religion

State-Sponsored Civil Religion

2.1.2. Type-Case II

Secular Nationalism

2.1.3. Type-Case III

Differentiated

3. Contextual Framework

3.1. Turkish Context: From Atatürk to Erdoğan

3.2. Current Stiation in The Netherlands

the vast majority of mosques in the Netherlands were affiliated with the Turkish government organization Diyanet, the Presidency of Religious Affairs. […] The chairmanship of the board of the foundation usually lies with the Attaché for Religious Affairs at the Turkish Embassy in The Hague (but people from the local communities play a big role both in the financing and the management of the various mosques). This diplomat, like the imams of the Diyanet mosques, is appointed by the Presidency of Religious Affairs in Ankara, which, after the military, is the largest government agency in the republic with over 100,000 employees. Religion is a state matter in Turkey, as in other predominantly Muslim countries. After the abolition of the caliphate and the position of Sheikh ul-Islam (the highest religious authority) in 1924, the republic took over the responsibility for the religious needs of the population (which is 98% Muslim). Diyanet is the instrument for this.

In response to criticisms of the Islamic Foundation of the Netherlands (ISN) adopting Ankara’s political line, Murat Türkmen, the ISN Secretary, has refuted the claim. He emphasizes that the ISN is an independent foundation that operates in compliance with Dutch law. Additionally, Türkmen argues that Turkey is viewed as the mother figure (ana) and the Netherlands as the father figure (baba), while the ISN shows equal reverence and esteem for both of these senior.[…] Diyanet offers a very broad range of services, such as funerals and the organization of the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, but ideological influence, if it occurs at all, is primarily through the Friday sermon in the mosque and through religious advice (fatwas).

The ISN has built or purchased all of its mosques with donations from Turkish Muslims residing in the Netherlands. Additionally, the organization is highly accessible and welcomes Muslims of all backgrounds to attend prayer services undisturbed, as per the statutes. ISN is a religious organization that does not involve itself in politics. It, along with its affiliated mosques, is subject to Dutch laws and regulations, and operates transparently in all aspects.6

4. Methodology

5. Analyses and Results

5.1. Construction of ‘Us’

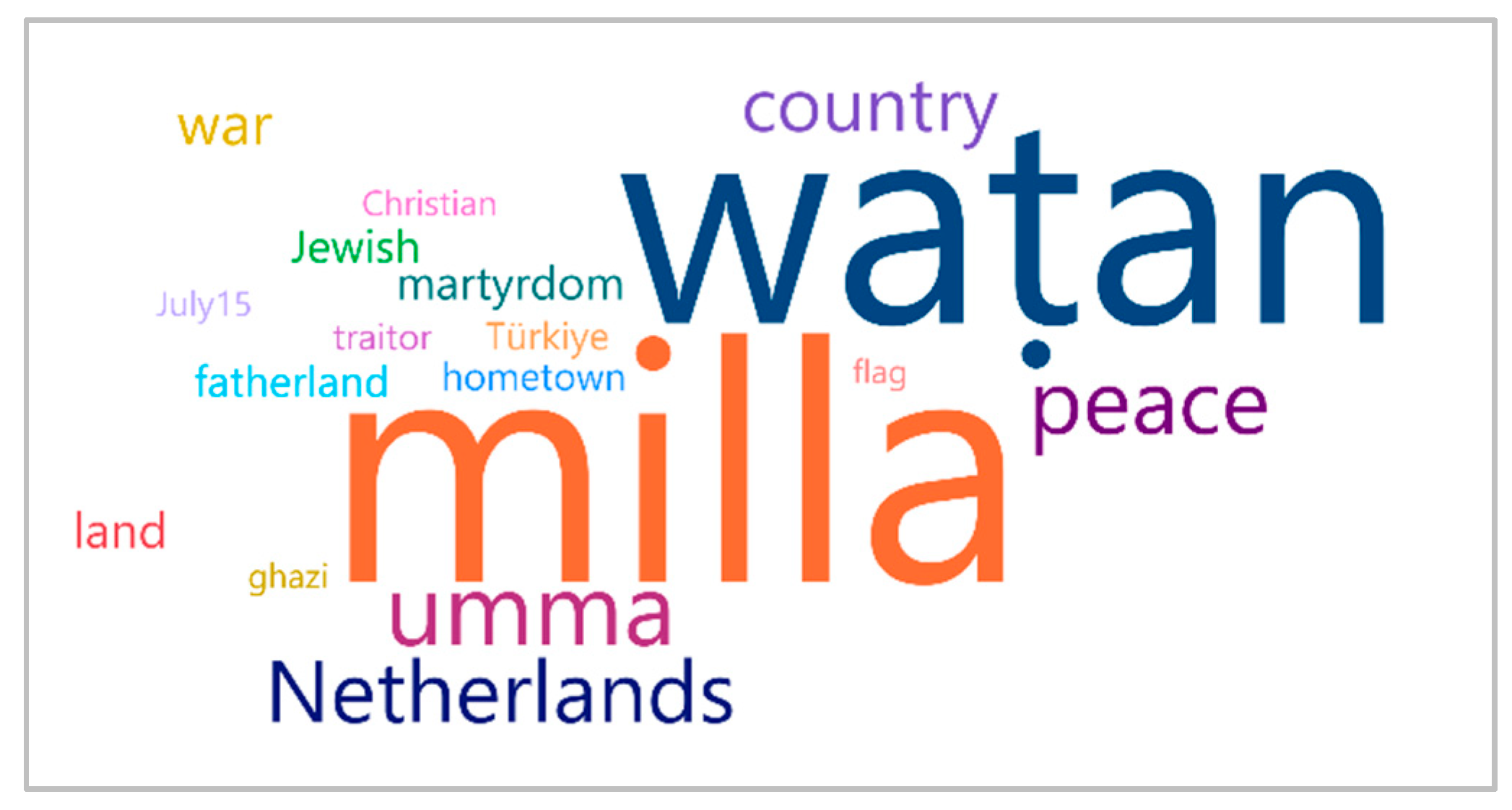

5.1.1. Milla

Assimilation will result from the loss of the language, according to the prepared Turkish text16 of the same sermon:National identity encompasses not only culture, but also language. […] language is necessary to understand yourself and the world. The disappearance of a language is therefore disastrous.(Language and identity; 5 July 2019)15

Another sermon follows emphasizes nationalist loyalty as a prerequisite for development into an ideal Muslim:…there are many people who lost their language and melted into other cultures.(Language and identity; 5 July 2019)

A young believer is one who is loyal to his national and spiritual values, has high morals and loves his country (waṭan) and people (milla).(Our youth are our future; 29 October 2021)

5.1.2. Waṭan

The idea of homeland (waṭan)17 is an important aspect of the nation-state paradigm. While providing physical space for the nation-state, the homeland also maintains a national identity by generating symbolic acts about the territory through a geographical imagination (Aslan 2015; Özkan 2012).In modern times, a new word entered the political vocabulary and is now almost universal […] It is the Arabic term waṭan, with its phonetic variations and equivalents in the other languages of Islam. In classical usage, waṭan means ‘one’s place of birth or residence’ […] The new meaning dates from the last years of the eighteenth century, and can be traced to foreign influence.

Following the victory over the ‘internal enemy’, the term waṭan is mentioned in another sermon:The Operation Peace Spring18 launched by our country against terrorist organizations in recent days is being protested by supporters of the terrorist organization in some cities of The Netherlands […] May Allah help our security forces. May he protect our homeland and our nation from all kinds of danger.(The construction and use of Mosques; 18 October 2019)19

In the quotations below, the word homeland is used in the following ways:We learned a lot from the terrible coup attempt on ‘15 July’ in our nation. I wish God’s mercy on our martyrs, to whom we owe the salvation of the homeland.(Religion is sincerity; 13 July 2018)

It is our greatest responsibility to leave a beautiful generation that takes the Messenger of Allah as an example and is loyal to its homeland and nation.(Mosque and religious education; 13 November 2020)

In one of the 2022 sermons entitled “Love of Homeland”, a new and more inclusive meaning was given to the word homeland, suggesting that we should also accept Holland, “the land we live in”, as our homeland.Self-sacrifice [fedakârlık] for our national and moral values is to take responsibility for religion, for the homeland, for the flag, for honour and for our future when appropriate.(The morality of cooperation; 5 December 2019)

The Prophet Muhammad did not lose any of his love and affection for his homeland and birthplace, Mecca. In accordance with human honor and dignity, he also chose Medina as his homeland and country. […] We should also be filled with this emotion and thought towards our homeland and the land we live in.(Love of Homeland; 18 March 2022)

In another sermon:We were sent to this world, which is the place of testing, in order to deserve God’s love and affection and to return to our original waṭan [homeland], Paradise.(We can earn our hereafter only in this world; 24 May 2019)

Everything is not just this world. One day we will say goodbye to this world. Let’s have faith and deeds that will make us smile when we go to the original waṭan [homeland].(The three holy months and the Regāib night; 24 March 2017)

5.1.3. Umma

Being a member of the Islamic umma, the believer closely observes what a large family they belong to during the pilgrimage:Our Lord describes Muslims as an exemplary community for humanity, an umma representing beauty, justice, and all human values.(Islam and Muslims in Europe; 31 March 2017)

What an honour it is to be from the umma of Muhammad! But being the members of the best umma chosen from among the human family also requires responsibility.(The most beautiful trait, good morals; 9 Augustus 2019)

5.2. Construction of the ‘Other’

Let us look at the examples given in a sermon titled, ‘The harms of substance abuse’:About 400,000 loaves of bread are thrown away every day in The Netherlands. Huge piles of garbage are created with the waste of 170 million kilograms of fruit and vegetables a year.(Let’s avoid waste; 22 June 2018)

In another sermon:According to studies, unfortunately, the age of smokers in The Netherlands has decreased to twelve. […] It was determined that one out of every five people in The Netherlands smoked cigarettes. Every year, 19,500 people die in The Netherlands due to the harms of smoking.(Substance abuse and its harms; 20 July 2018)

According to statistics, there are 1.1 million diabetics in The Netherlands, the country we live in.(Fasting and health; 26 April 2019)

Dear Muslims! Next Sunday, 5 May 2019, is the Dutch liberation day. On this occasion, we respectfully commemorate the people who fought and lost their lives for the liberation of The Netherlands in World War II. May our Lord grant eternal peace, tranquility, and happiness to the society we live in. Amine.

Deception (taqiyyah) is a spiritual ailment that we must steer clear of. It involves portraying oneself as different for the sake of worldly gain and using dishonest tactics to harm Islam from within. Those who engage in this practice view betrayal and hypocrisy as a religious obligation to achieve their goals. This behavior is detrimental not only to those who partake in it but also to society as a whole. The failed coup attempts in Turkey on 15 July 2016, provide clear evidence of the harm caused by such actions.

Approximately 70,000 individuals of Kurdish descent, hailing from the Kurdish regions of Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, reside in the Netherlands. In this particular sermon, the ISN classified all Kurds participating in these protests as “supporters of a terrorist organization”.The Peace Spring Operation launched by our country against terrorist organizations in recent days is being protested by supporters of the terrorist organization in some cities of The Netherlands […](The construction and use of Mosques; 18 October 2019)

5.3. Conclusions

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | More recent publications also indicate that there is a growing interest in the application of discourse analysis to the study of religion (see Hjelm 2014; Johnston and von Stuckrad 2021; Wijsen 2021; Wijsen and von Stuckrad 2016). |

| 2 | Non-formal education here can be defined as the organized educational activity outside the established formal system—whether operating separately or as an important feature of some broader activity—that is intended to serve identifiable learning clienteles and learning objectives. The distinction between formal and informal education is largely administrative. Formal education is linked with schools and training institutions; non-formal is linked with community groups and other organizations; and informal covers what is left, e.g., interactions with friends, family, and work colleagues (Schweitzer et al. 2019). |

| 3 | In some ways, he intended it to be independent of the church when he called it “civil”, and he similarly intended it to be independent of the ruling government when he called it “religion” (Bellah and Hammond 1980). |

| 4 | According to Wuthnow, both civil religion and nationalism serve as belief systems that give the collective identity, meaning, and purpose. Both explain how the group views itself as well as its illustrative past and desired future. The key definition of “who belongs to the nation and who does not” is presented in both attempts to arouse feelings of community belonging and civic loyalty (Wuthnow 1994, p. 131). |

| 5 | When a particular religious organization controls civil religion in a nation, it leads to three main problems. Firstly, it creates challenges for the civil and religious liberties of minorities in the country, as demonstrated by the persecution of Protestants in Spain and Christians in Ceylon. Secondly, it raises questions about the national loyalties of religious minorities and puts undue pressure on them. For instance, in medieval Europe, Jews were often considered disloyal citizens, as were Protestants in France before the revolution and Catholics in post-Elizabethan England. |

| 6 | See for the further critics from the parliament and responses of the ISN’s president Murat Türkmen: Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry into undesired influence on social and religious organizations in the Netherlands (POCOB) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mR9J341M51U (accessed on: 19 May 2021). |

| 7 | To see the arguments of the debates between the Netherlands and Turkey (see NRC 2022). |

| 8 | A few days before Friday, the sermons are shared as four differen versions—Turkish, Dutch, Dutch summary, and (since 2022) Arabic—on the ISN’s website. The sermons are first written in Turkish and then translated into Dutch (by Ahmed Bulut (specialist in religious translations at the ISN)) and Arabic. However, these translations are sometimes not in the form of one-to-one translations (please see 16th note). Mostly, the sermons are read aloud by the imams in Turkish. In cases where the imam knows Dutch at a certain level, a short summary in Dutch is read aloud at the end of the sermon (Gürlesin 2019). For the sermons published since the beginning of 2017, see: https://diyanet.nl/cuma-hutbeleri/ (accessed on: 3 October 2021). |

| 9 | CDA does not claim to be able to adopt an objective, socially neutral analytical position, in contrast to other forms of discourse and conversation analysis. CDA practitioners do in fact argue that such apparent political indifference eventually contributes to preserving an unjust status quo. The emancipatory, socially critical method of CDA aligns itself with individuals who experience political and social injustice (Wodak et al. 2009). |

| 10 | Considering that there are 52 weeks in a year, this number should have been 312 in 6 years. Since the mosques are closed within the framework of the COVID-19 measures, the sermon broadcast was paused for a period of 2 weeks (between 20 March 2020 – 27 April 2020). |

| 11 | For information about mosques affiliated with the ISN, see: https://diyanet.nl/hizmetlerimiz/subelerimiz/sube-cami-adresleri/ (accessed on 6 May 2021). |

| 12 | For the sermons published since the beginning of 2017, see: https://diyanet.nl/cuma-hutbeleri/ (accessed on 5 April 2021). |

| 13 | Differences between the Turkish and Dutch versions of the sermons are evident, and this analysis will attempt to highlight them in subsequent sections. Given that the primary language of the sermons is Turkish, the focus of this discourse analysis will be on that language. |

| 14 | In mosques where Turkish is the predominant language, the inclusion of Arabic parts in the Friday sermons is significant in fostering a sense of unity (umma) with other Muslim ethnic groups who do not speak Turkish. |

| 15 | The author of this article personally translated all excerpts from the ISN sermons into English. |

| 16 | As previously mentioned, there are significant differences between the Turkish text and its Dutch translation. The Dutch translation of the aforementioned passage reads as follows: “In de loop van de geschiedenis zijn sommige talen verloren gegaan en dat is erg jammer” (In the course of history, some languages have been lost, and that is very unfortunate). The emphasis on assimilation seems to have been removed in the Dutch translation. |

| 17 | Waṭan—which, in Arabic, means the place of one’s birth—can be translated as “homeland” in English. But this translation does not entirely reflect the implied meaning of the word in the Turkish language. In English, “homeland” refers to the territory of the nation-state, but in Turkish, waṭan occupies a unique predominating status in political discourse. It refers not only to the national territory but also to major political and legal concepts derived from the word waṭan, including citizen (vatandaş), patriotism (vatanseverlik), heimatlos (vatansız), high treason (vatana ihanet), and traitor to homeland (vatan haini) (Özkan 2012). |

| 18 | The 2019 Turkish offensive into northeastern Syria, codenamed Operation Peace Spring (Turkish: Barış Pınarı Harekâtı) by Turkey, was a cross-border military operation conducted by the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) and the Syrian National Army (SNA) against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and later Syrian Arab Army (SAA) in northern Syria. |

| 19 | This part of the sermon is only in the Turkish text; it is not included in the Dutch translation. |

| 20 | In the sermons analyzed in this study, the term “Nederlands” (Hollanda) appears 378 times. However, it was found that in the majority of these instances (specifically 306 times), the term is mentioned at the end of the sermon to indicate that it was prepared by the ISN in the form of “Hollanda Diyanet Vakfı”. Since this portion is not recited during the sermonzengin, it was excluded from the analysis conducted in this study. |

| 21 | The July 15th coup attempt in Turkey and its commemoration has become integrated into the new calendric method in both Turkey and the Netherlands. This phenomenon is not new, as Zengin (2008) found in his study of Friday sermons during the Second Constitutional Monarchy period of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1920) that the content of sermons was strongly influenced by the Islamic calendar, with important seasons, months, days, and nights shaping the subjects addressed. This tradition continued throughout the 20th century and into the present day, with the calendric method remaining a significant factor in determining the content of sermons. |

| 22 | In the aftermath of the coup attempt of 15 July 2016, President Erdoğan launched a purge against Fethullah Gülen’s followers. The government declared a state of emergency and dismissed or suspended more than 130,000 civil servants from their jobs, arrested or imprisoned more than 80.000 citizens, and closed more than 1.500 non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for alleged ties to Gülen and his movement. As part of this operation, the Gülen movement was designated by the Turkish government as the ‘Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation’ (‘FETO’). |

| 23 | The sermon titles for the week of July 15 in the last six years of the PRA were selected as follows: 2022, “Victory of Unity and Togetherness”; 2021, “We Witness Loyalty, Courage and Martyrdom Against Betrayal”; 2020, “July 15 and Spirit of Unity”; 2019, “Commemoration of July 15 and Understanding the Betrayal”; 2018, “Rebirth of a Nation”; and 2017, “Resistance Witnessed by the Sala: July 15”. To access the sermons from the past five years in various languages, please visit the PRA’s sermon archive at https://dinhizmetleri.diyanet.gov.tr/kategoriler/yayinlarimiz/hutbeler/hutbe-ar%C5%9Fivi (accessed on: 21 May 2021). |

| 24 | Taḳiyya is a practice in Islam whereby one conceals their religious beliefs and refrains from performing their regular religious duties when faced with a threat of harm or death. This practice can be employed to protect either an individual or a community, and its usage and interpretation may vary across different Islamic sects. For further insight, refer to the work of Strothmann and Djebli (2012) on this topic. |

| 25 | The nation’s failure to uphold its ideals can be criticized using civil religion. Martin Luther King Jr., for instance, used the language of civil religion to urge the United States to improve and become a more racially equal society. |

| 26 | It would be advantageous for religious scholars who study multiple identities or diverse allegiances in multicultural cultures to link CDA and dialogical self theory (DST) (see Wijsen 2021). |

References

- Almási, Zsolt, and Bulcsu Bognar. 2014. Transfigurations of the European Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, Ednan. 2015. Citizenship Education and Islam. In Islam and Citizenship Education. Edited by Ednan Aslan and Marcia Hermansen. Wien: Springer, pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N. 1967. Civil Religion in America. Daedalus 96: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N., and Phillip E. Hammond. 1980. Varieties of Civil Religion. Oregon: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Boender, Welmoet. 2012. Teaching Integration in the Netherlands: Islam, Imams and the Secular Governments. In Perceptions of Islam In Europe/Culture, Identity and the Muslim ‘Other’. Edited by Hakan Yılmaz and Çagla E. Aykaç. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, pp. 145–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bora, Tanıl. 2003. Nationalist Discourses in Turkey. The South Atlantic Quarterly 102: 433–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Halil İbrahim. 2012. Ümmet. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, vol. 42, pp. 308–9. [Google Scholar]

- Çağrıcı, Mustafa. 2012. Vatan. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, vol. 42, pp. 563–64. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Antony. 2021. Imagining E Pluribus Unum: Narrating the Nation through Mediated American Civil Religion. Chicago: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Carol, Sarah, and Lukas Hofheinz. 2022. A Content Analysis of the Friday Sermons of the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs in Germany (DİTİB). Politics and Religion 15: 649–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaymaz, Burcu. 2019. The construction and re-construction of the civil religion around the cult of Atatürk. Middle Eastern Studies 55: 945–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2020. Religie in Nederland [Webpagina]. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. December 17. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/longread/statistische-trends/2020/religie-in-nederland (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Çitak, Zana. 2010. Between ‘Turkish Islam’and ‘French Islam’: The role of the diyanet in the conseil Français du culte musulman. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36: 619–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James A. 1970. Civil Religion. Sociological Analysis 31: 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristi, Marcela. 2001. From Civil to Political Religion: The Intersection of Culture, Religion and Politics. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cristi, Marcela. 2009. Durkheim’s Political Sociology. Civil Religion, Nationalism and Globalisation. In Holy Nations and Global Identities: Civil Religion, Nationalism, and Globalisation. Edited by Annika M. Hvithamar, Margit Warburg and Brian Jacobsen. Boston: BRILL. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2001. Global Civil Religion: A European Perspective. Sociology of Religion 62: 455–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1961. Moral Education: A Study in the Theory and Application of the Sociology of Education. New York: Free Press. First published 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1961. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Joseph Ward Swain. New York: Collier Books. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1964. The Division of Labour in Society. Translated by G. Simpson. New York: Free Press. First published 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1973. Individualism and the Intellectuals. In Emile Durkheim: On Morality and Society. Edited by Robert N. Bellah. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 43–57. First published 1898. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1992. Civic Morals. In Professional Ethics and Civic Morals. Translated by Cornelia Brookfield. London: Routledge. First published 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Durmuş, Zeki. 2009. Bilgi Edin(dir)me Aracı Olarak Hutbe [Khutbah as a Means of Knowledge Acquisition]. Ankara: Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı Yayınları, pp. 839–52. [Google Scholar]

- Es, Murat. 2012. Turkish-Dutch Mosques and the Construction of Transnational Spaces in Europe. Ph.D. thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, December. [Google Scholar]

- Essabane, Kamel, Paul Vermeer, and Carl Sterkens. 2022. Islamic Religious Education and Citizenship Education: Their Relationship According to Practitioners of Primary Islamic Religious Education in The Netherlands. Religions 13: 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman. 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman, and Ruth Wodak. 1997. Critical Discourse Analysis. In Discourse as Social Interaction. Edited by Teun A. Van Dijk. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi: Wiley, pp. 258–84. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, Mike. 1990. Global Culture: An Introduction. In Global Culture Nationalism, Globalisation and Modernity. Edited by Mike Featherstone. London: Sage, pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, Stefen, and Michael. D. Yaffe, eds. 2020. Civil Religion in Modern Political Philosophy. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig, Glenn. 1981. The American civil religion debate: A source for theory construction. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 20: 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gering, Zoe. 2015. Content analysis and/or discourse analysis. A mixed methods approach in textual analysis. Paper presented at 12th Conference of the European Sociological Association 2015, Prague, Czech Republic, August 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon, John. 2008. God is great, God is good: Teaching god concepts in Turkish Islamic sermons. Poetics 36: 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsberts, Mérove, and Jeanet Dagevos. 2009. At Home in the Netherlands? Trends in Integration of Non-Western Migrants. Den Haag: The Netherlands Institute for Social Research|SCP. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, Charles Y., and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. Chicago: Rand McNally and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, Philip. 2011. Barack Obama and Civil Religion. Rethinking Obama 22: 179–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, Philip. 2019. American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, Philip. 2021. 1. The Past and Future of the American Civil Religion. In Civil Religion Today. New York: New York University Press, pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gülsah Çapan, Zeynep, and Ayşe Zarakol. 2019. Turkey’s ambivalent self: Ontological insecurity in ‘Kemalism’ versus ‘Erdoğanism’. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32: 263–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlesin, Ömer F. 2018. Elite and popular religiosity among Dutch-Turkish Muslims in the Netherlands. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gürlesin, Ömer F. 2019. Major Socio–Political Factors that Impact on the Changing Role, Perception and Image of Imams among Dutch–Turkish Muslims. Education Sciences 9: 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlesin, Ömer F. 2020. Transformation of Friday sermons in an era of nationalism: Functionalization of religion in Turkey and the Netherlands, now and in a challenged future. In Religious Education on the Move—Challenging the Unknown Future of RE. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 223–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, Andrew. 2017. Salafi thought in Turkish public discourse since 1980. International Journal of Middle East Studies 49: 417–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashas, Mohammed. 2018. The European imam: A nationalized religious authority. In Imams in Western Europe Developments, Transformations, and Institutional Challenge. Edited by Mohammed Hashas, Jan Jaap de Ruiter, Niels Valdemar Vinding and K. Hajji. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm, Titus. 2014. Religion, Discourse and Power: A Contribution towards a Critical Sociology of Religion. Critical Sociology 40: 855–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdert, Milena, and Andreas Kouwenhoven. 2018. Geheime Lijsten Financiering Moskeeën Onthuld. April 23. Available online: https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2228686-geheime-lijsten-financiering-moskeeen-onthuld (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Holdert, Milena, and Andreas Kouwenhoven. 2019. Grote Zorgen Tweede Kamer na Onderzoek Salafistische Moskeescholen. September 10. Available online: https://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/artikel/2301159-grote-zorgen-tweede-kamer-na-onderzoek-salafistische-moskeescholen (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Hvithamar, Annika, Margit Warburg, and Brian Jacobsen. 2009. Holy Nations and Global Identities: Civil Religion, Nationalism, and Globalisation. Boston: BRILL, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Jeffrey, and Kocku von Stuckrad, eds. 2021. Discourse Research and Religion Disciplinary Use and Interdisciplinary Dialogues. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kahla, Elina. 2014. Civil Religion in Russia: A Choice for Russian Modernization? Baltic Worlds: Scholarly Journal: News Magazin, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Karakuş, Gülbeyaz. 2018. Cumhuriyet’in Politik Teolojisi: Türkiye’de Kurucu Ideolojinin Sivil Din Ihdâsı [Political Theology of the Republic: The Creation of Civil Religion as the Founding Ideology in Turkey]. Ankara: Cedit Neşriyat. [Google Scholar]

- Kokosalakis, Nicos. 1985. Legitimation Power and Religion in Modern Society. Sociological Analysis 46: 367–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükcan, Talip. 2010. Sacralization of the state and secular nationalism: Foundations of civil religion in Turkey. George Washington International Law Review 41: 963–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Bernard. 1988. The political language of Islam. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lienesch, Michael. 2018. Contesting Civil Religion: Religious Responses to American Patriotic Nationalism, 1919–1929. Religion and American Culture 28: 92–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiavelli, Niccolò. 1985. The Prince. Translated by Harvey C. Mansfield. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Machiavelli, Niccolò. 1996. Discourses on Livy. Translated by Harvey C. Mansfield, and Nathan Tarcov. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Madanat, Philip O. 2019. Framing the Friday Sermon to Shape Opinion: The Case of Jordan. London: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mandacı, Nazif. 2022. The Momentary Glory of Banal Ottomanism. In Critical Readings of Turkey’s Foreign Policy. Edited by Birsen Erdoğan and Fulya Hisarlıoğlu. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 149–69. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Ruth A. 2005. Legislating Authority: Sin and Crime in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. Edited by Ruth A. Miller. Great Britain: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties. 2020. AIVD Annual Report 2020: Growing Breeding Ground for Extremism—News Item—AIVD [Nieuwsbericht]; Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties. Available online: https://english.aivd.nl/latest/news/2021/04/05/aivd-annual-report-2020 (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Moberg, Marcus. 2022. Religion, Discourse, and Society: Towards a Discursive Sociology of Religion. Abingdon: Oxon. [Google Scholar]

- Mutluer, Nil. 2018. Diyanet’s Role in Building the ’Yeni (New) Milli’ in the AKP Era. European Journal of Turkish Studies 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmabadi, Afsaneh. 1997. The Erotic Vaṭan [Homeland] as Beloved and Mother: To Love, To Possess, and To Protect. Comparative Studies in Society and History 39: 442–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskali, Emine Gürsoy. 2017. Cuma hutbeleri ve toplumun talepleri [Friday sermons and demands of society]. In Hutbe Kitabı. Edited by Emine Gürsoy Naskali. Istanbul: Kitabevi Yayınları, pp. 343–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Jørgen S. 2015. Citizenship Education in Multicultural Societies. In Islam and Citizenship Education. Edited by Ednan Aslan and Marcia Hermansen. Vienna: Springer, pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant (NRC). 2022. Diplomatieke crisis Turkije-Nederland. Available online: https://www.nrc.nl/dossier/diplomatieke-crisis-turkije-nederland/ (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Okumuş, Ejder. 2005. Dinin Meşrulaştırma Gücü. Istanbul: Ark Kitapları. [Google Scholar]

- Ongur, Hakan Övünç. 2020. Performing through Friday khutbas: Re-instrumentalization of religion in the new Turkey. Third World Quarterly 41: 434–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, Ezgi. 2016. Reflection of political restructuring on urban symbols: The case of presidential palace in Ankara, Turkey. Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 40: 206–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdalga, Elisabeth. 2021. Pulpit, Mosque and Nation: Turkish Friday Sermons as Text and Ritual. Great Britain: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, Behlül. 2012. From the Abode of Islam to the Turkish Vatan: The Making of a National Homeland in Turkey. London and New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi. 2016. Turkey’s Diyanet under AKP rule: From protector to imposer of state ideology? Journal of Southeast European and Black Sea 16: 619–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi. 2018. Transformation of the Turkish Diyanet both at Home and Abroad: Three Stages. European Journal of Turkish Studies 27: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi, and Bahar Baser. 2022. The transnational politics of religion: Turkey’s Diyanet, Islamic communities and beyond. Turkish Studies 23: 701–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi, and Semiha Sözeri. 2018. Diyanet as a Turkish Foreign Policy Tool: Evidence from the Netherlands and Bulgaria. Politics and Religion 11: 624–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padela, Aasim I., Sana Malik, and Nadia Ahmed. 2018. Acceptability of Friday Sermons as a Modality for Health Promotion and Education. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 20: 1075–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalet, Karen, Gülseli Baysu, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2010. Political mobilization of Dutch Muslims: Religious identity salience, goal framing, and normative constraints. Journal of Social Issues 66: 759–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, Karoly. 2014. The Potential Role of Civil Religion in Shaping the Identity of Citizens: The United States vs. Europe. Civil Szemle 11: 153–72. [Google Scholar]

- Polititeacademie. 2008. NCTV and Dutch Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations, Salafisme in Nederland: Een Voorbijgaand Fenomeen of een Blijvende Factor van Belang? [Salafism in the Netherlands: A Passing Phenomenon or a Lasting Factor of Importance?]. Available online: https://www.politieacademie.nl/kennisenonderzoek/kennis/mediatheek/PDF/68871.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Quinn, T. S. 2020. Machiavelli, Christianity, and Civil Religion. In Civil Religion in Modern Political Philosophy. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reddig, Melanie. 2011. Power struggle in the religious field of Islam: Modernization, globalization and the rise of salafism. In The Sociology of Islam/Secularism, Economy and Politics. Edited by Tugrul Keskin. Berkshire: Ithaca Press, pp. 153–76. [Google Scholar]

- Roose, Eric. 2009. The Architectural Representation of Islam: Muslim-Commissioned Mosque Design in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rouner, Leroy S. 1986. Civil Religion and Political Theology. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1913. Discourse on the Arts and Sciences. Translated by G. D. H. Cole. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1979. Emile, or On Education. Translated by Allan Bloom. Minnesota: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. 1994. Discourse on Political Economy and, The Social Contract. Translated by C. Betts. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saçan, Patrycja H. 2022. Civil Religion in Turkey: The Unifying and Divisive Potential of Material Symbols. The Jugaad Project. Available online: https://www.thejugaadproject.pub/home/civil-religion-turkey (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Santiago, Jose. 2009. From ‘Civil Religion’ to Nationalism as the Religion of Modern Times: Rethinking a Complex Relationship. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbai, Youssef. 2019. Islamic Friday Sermon in Italy: Leaders, Adaptations, and Perspectives. Religions 10: 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, Friedrich, Wolfgang Ilg, and Peter Schreiner. 2019. Researching Non-Formal Religious Education in Europe. Münster/New York: Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Şentürk, Recep. 2005. Millet. In Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, vol. 30, pp. 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shimazono, Susumu. 2005. State Shinto and the Religious Structure of Modern Japan. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 73: 1077–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoop, Kelly S. 2005. If you are a good Christian you have no business voting for this candidate: Church sponsored political activity in federal elections. Wash. ULQ 83: 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Sözeri, Semiha, Hülya Altinyelken, and Monique Volman. 2021. Pedagogies of Turkish Mosque Education in the Netherlands: An Ethno-case Study of Mosque Classes at Milli Görüş and Diyanet. Journal of Muslims in Europe 10: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sözeri, Semiha, Hülya Kosar Altinyelken, and Monique Volman. 2022. Turkish-Dutch Mosque Students Negotiating Identities and Belonging in The Netherlands. Religions 13: 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjernholm, Simon. 2020. Muslim Preaching in the Middle East and Beyond: Historical and Contemporary Case Studies. Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckl, Kristina. 2020. Russian orthodoxy and secularism. Brill Research Perspectives in Religion and Politics 1: 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strothmann, Rolf, and Moktar Djebli. 2012. Taḳiyya. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, p. X:134b. Available online: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com:443/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/takiyya-SIM_7341 (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Sunier, Thijl. 2005. Constructing Islam: Places of worship and the politics of space in the Netherlands. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 13: 317–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunier, Thijl. 2010. Islam in the Netherlands: A nation despite religious communities? In Religious Newcomers and the Nation State: Political Culture and Organized Religion in France and the Netherlands. Edited by J. T. Sunier and Erik Sengers. Delft: Eburon, pp. 115–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sunier, Thijl. 2018. The making of Islamic authority in Europe. In Imams in Western Europe Developments, Transformations, and Institutional Challenge. Edited by Mohammed Hashas, Jan Jaap De Ruiter and Niels Valdemar Vinding. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sunier, Thijl, and Nico Landman. 2014. Transnational Turkish Islam. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- Sunier, Thijl, Heleen van der Linden, and Ellen van de Bovenkamp. 2016. The long arm of the state? Transnationalism, Islam, and nation-building: The case of Turkey and Morocco. Contemporary Islam 10: 401–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Avest, Ina, Cok Bakker, and Leni Franken. 2021a. Islamic Religious Education in the Netherlands. In Islamic religious Education in Europe: A Comparative Study. Edited by Leni Franken and Bill Gent. New York: Routledge, pp. 179–95. [Google Scholar]

- ter Avest, Ina, Ibrahim Kurt, Ömer F. Gürlesin, and Alper Alasag. 2021b. Normative Citizenship Education in Plural Societies: A Dialogical Approach to Possible Tensions Between Religious Identity and Citizenship. In Religion, Citizenship and Democracy. Edited by Alexander Unser. Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Bryan. S. 2013. The Religious and the Political: A Comparative Sociology of Religion. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, Chris R., and Sarah S. Kamhawi. 2015. Friday sermons, family planning and gender equity attitudes and actions: Evidence from Jordan. Journal of Public Health 37: 641–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursinus, Michael O. H. 2012. Millet. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by Peri Bearman, Thierry Bianquis, Clifford E. Bosworth, Emeri van Donzel and Wolfhart P. Heinrichs. Leiden: Brill, p. VII:61b. Available online: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com:443/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/millet-COM_0741 (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- van Bruinessen, Martin. 2011. Producing Islamic knowledge in Western Europe: Discipline, authority, and personal quest. In Producing Islamic Knowledge/Transmissions and dissemination in Western Europe. Edited by M. V. Bruinessen and S. Allievi. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- van Bruinessen, Martin. 2018. The Governance of Islam in Two Secular Polities: Turkey’s Diyanet and Indonesia’s Ministry of Religious Affairs. European Journal of Turkish Studies 27: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, Teun A. 1993. Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society 4: 249–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vegter, Annemarie, Andrew R. Lewis, and Christopher J. Bolin. 2023. Which civil religion? Partisanship, Christian nationalism, and the dimensions of civil religion in the United States. Politics and Religion 16: 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, Maykel, and Ali Aslan Yildiz. 2009. Muslim immigrants and religious group feelings: Self-identification and attitudes among Sunni and Alevi Turkish-Dutch. Ethnic and Racial Studies 32: 1121–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, Maykel, and Ali Aslan Yildiz. 2010. Religious identity consolidation and mobilization among Turkish Dutch Muslims. European Journal of Social Psychology 40: 436–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welten, Liselotte, and Tahir Abbas. 2021. Critical Perspectives on Salafism in the Netherlands; Research Paper. International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT). Available online: https://www.icct.nl/index.php/publication/critical-perspectives-salafism-netherlands (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Wielzen, Ronnie, and Ina ter Avest, eds. 2017. Interfaith Education for All Theoretical Perspectives and Best Practices for Transformative Action, 1st ed. Rotterdam: SensePublishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wijsen, Frans. 2021. Whose Voice Is This? The Multicultural Drama from CDA and DST Perspectives. In Discourse Research and Religion: Disciplinary Use and Interdisciplinary Dialogues. Edited by Kocku von Stuckrad and Jay Johnston. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wijsen, Frans, and Kocku von Stuckrad, eds. 2016. Making Religion: Theory and Practice in the Discursive Study of Religion. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Rhys H. 2020. Civil Religion. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Adam Possamai and Anthony J. Blasi. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 138–40. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Rhys H. 2021. Civil Religion Today: Religion and the American Nation in the Twenty-First Century. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth, Rudolf de Cillia, Martin Reisigl, Richard Rodger, and Karin Liebhart. 2009. The Discursive Construction of National Identity, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow, Robert. 1994. Producing the Sacred: An Essay on Public Religion. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yanaşmayan, Zeynep. 2010. Role of Turkish Islamic organizations in Belgium: The strategies of Diyanet and Milli Görüş. Insight Turkey 12: 139–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, İhsan, and İsmail Albayrak. 2022. Populist and Pro-Violence State Religion: The Diyanet’s Construction of Erdoğanist Islam in Turkey. Singapore: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Zengin, Salih. 2008. Osmanlılar Döneminde Yaygın Din Eğitimi Faaliyeti Olarak Hutbeler [Sermons as an Informal Religious Education in the Ottoman Period]. Çukurova Ü. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 17: 379–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik Jan. 2020. Position Paper E. Zürcher t.b.v. Openbaar Verhoor Parlementaire Ondervragingscommissie Ongewenste Beïnvloeding uit Onvrije Landen d.d. 20 Februari 2020 [Text]. Available online: https://www.tweedekamer.nl/kamerstukken/detail?id=2020Z04239&did=2020D08799 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

| Is the Civil Religion Independent of the Church? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Is the civil religion independent of the state? | Yes | Differentiated | Continued undifferentiation |

| No | Secular nationalism | ||

| Is the Civil Religion Independent of the Religious Authority? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Is the civil religion independent of the state? | Yes | Differentiated (liberal Islam) | |

| No | Secular nationalism (Kemalism) | Continued undifferentiation (political Islam) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gürlesin, Ö.F. Understanding the Political and Religious Implications of Turkish Civil Religion in The Netherlands: A Critical Discourse Analysis of ISN Friday Sermons. Religions 2023, 14, 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14080990

Gürlesin ÖF. Understanding the Political and Religious Implications of Turkish Civil Religion in The Netherlands: A Critical Discourse Analysis of ISN Friday Sermons. Religions. 2023; 14(8):990. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14080990

Chicago/Turabian StyleGürlesin, Ömer F. 2023. "Understanding the Political and Religious Implications of Turkish Civil Religion in The Netherlands: A Critical Discourse Analysis of ISN Friday Sermons" Religions 14, no. 8: 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14080990

APA StyleGürlesin, Ö. F. (2023). Understanding the Political and Religious Implications of Turkish Civil Religion in The Netherlands: A Critical Discourse Analysis of ISN Friday Sermons. Religions, 14(8), 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14080990