The Necessity of an Incarnate Prophet

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Nature of the Abrahamic Religions

|

|

|

|

1.2. Reasons for the Christian Position

| God would send a divine prophet in order to share in human suffering, provide a means of atonement and theological and moral instruction. |

| On the basis of the nature of God and the human condition, we should expect (with a level of certainty) that God will send a divine and atoning prophet into the world in order to realise his ultimate aim for creation: flourishment. |

|

|

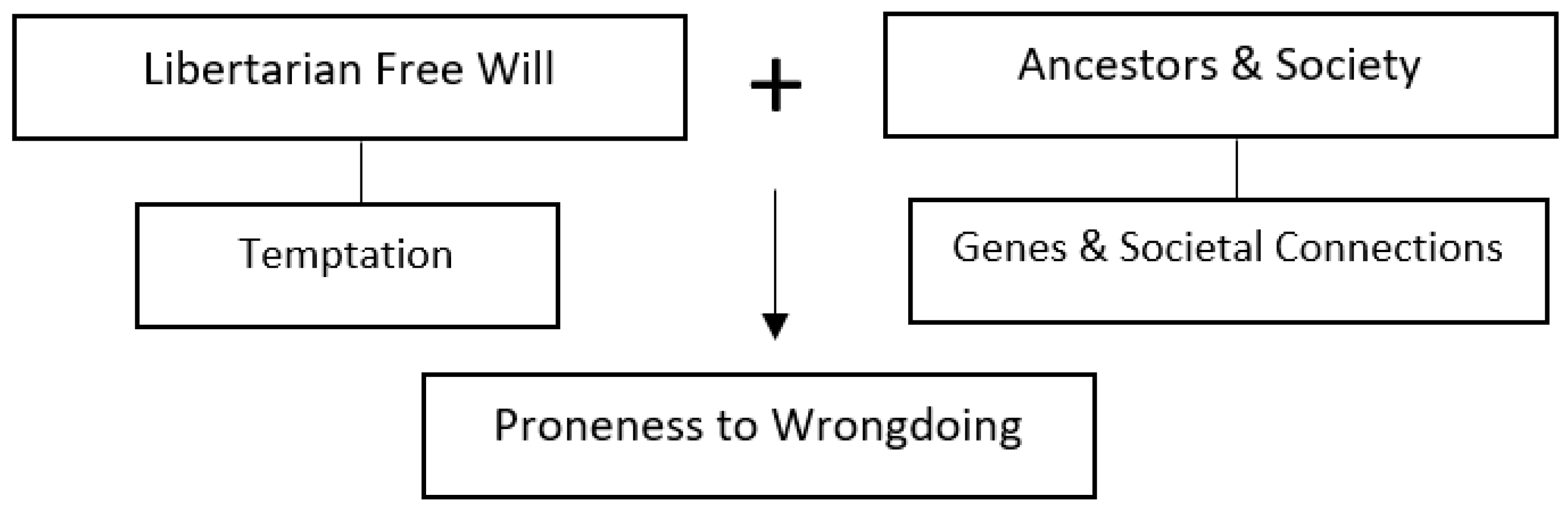

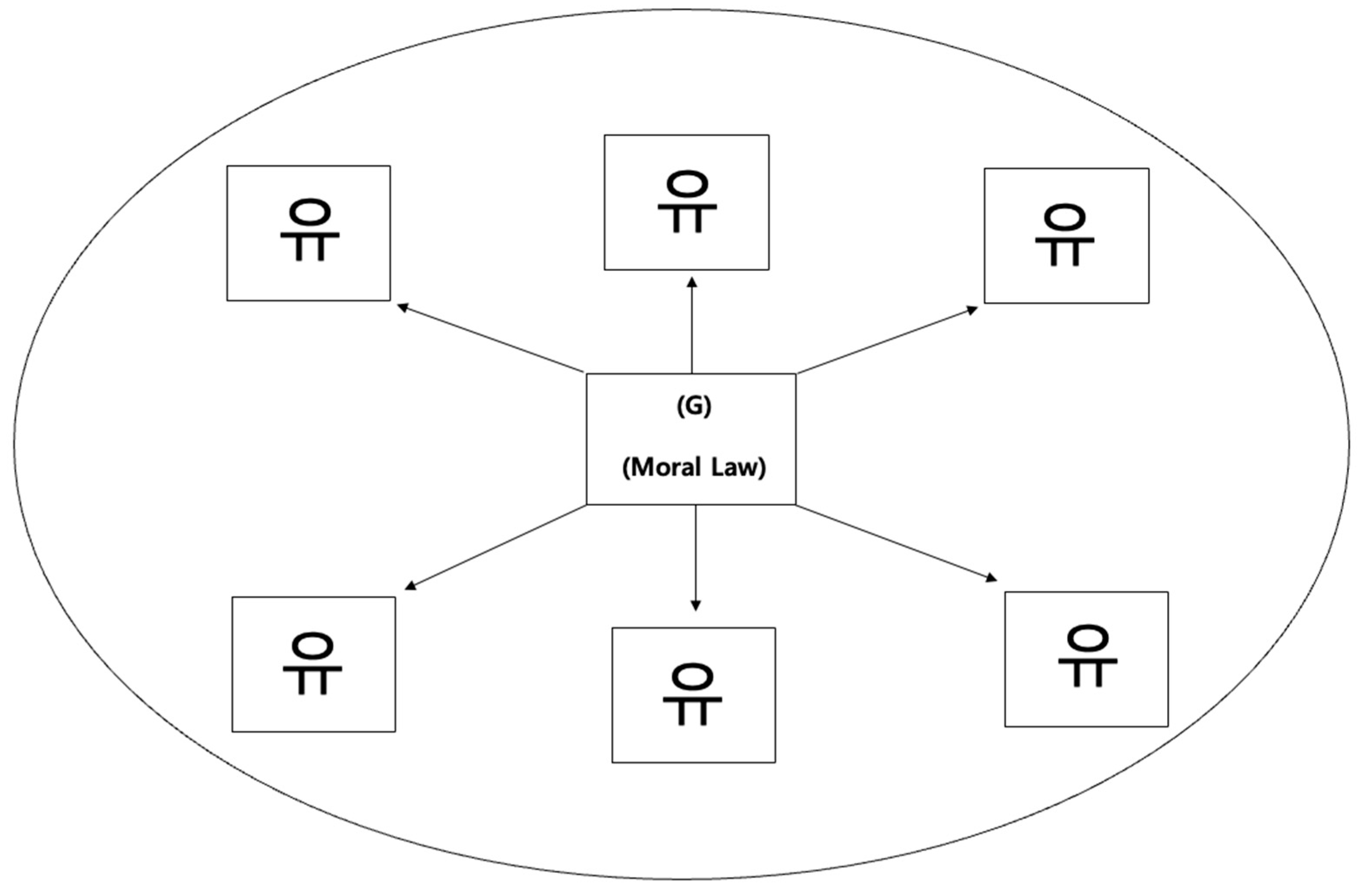

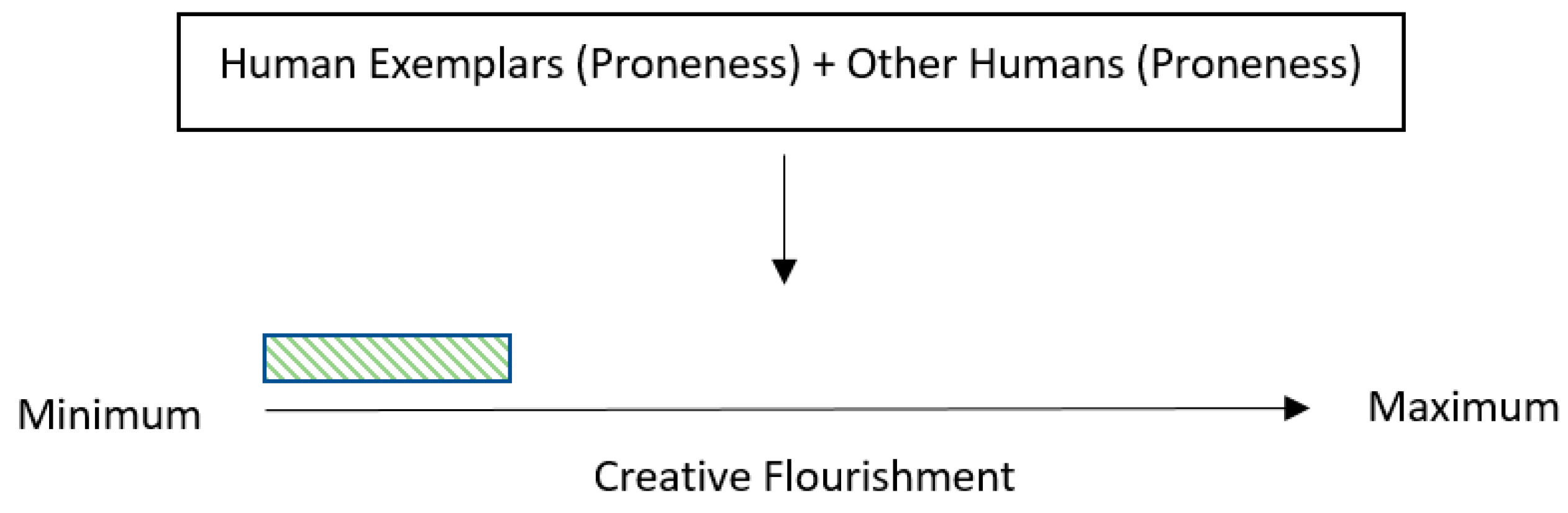

| The condition of humanity is such that each individual human with libertarian free will has genetically and socially inherited a proneness to wrongdoing. |

Even if the society’s moral teaching is correct and so regarded by some man, it may be treated with such casualness and levity that the desire to imitate other men which would otherwise reinforce pursuit of the good now acts in a contrary direction, making it easier to yield to temptation. Conversely the power of good example is of course enormous.

2. Personal Flourishment: The Necessity of the Prophet

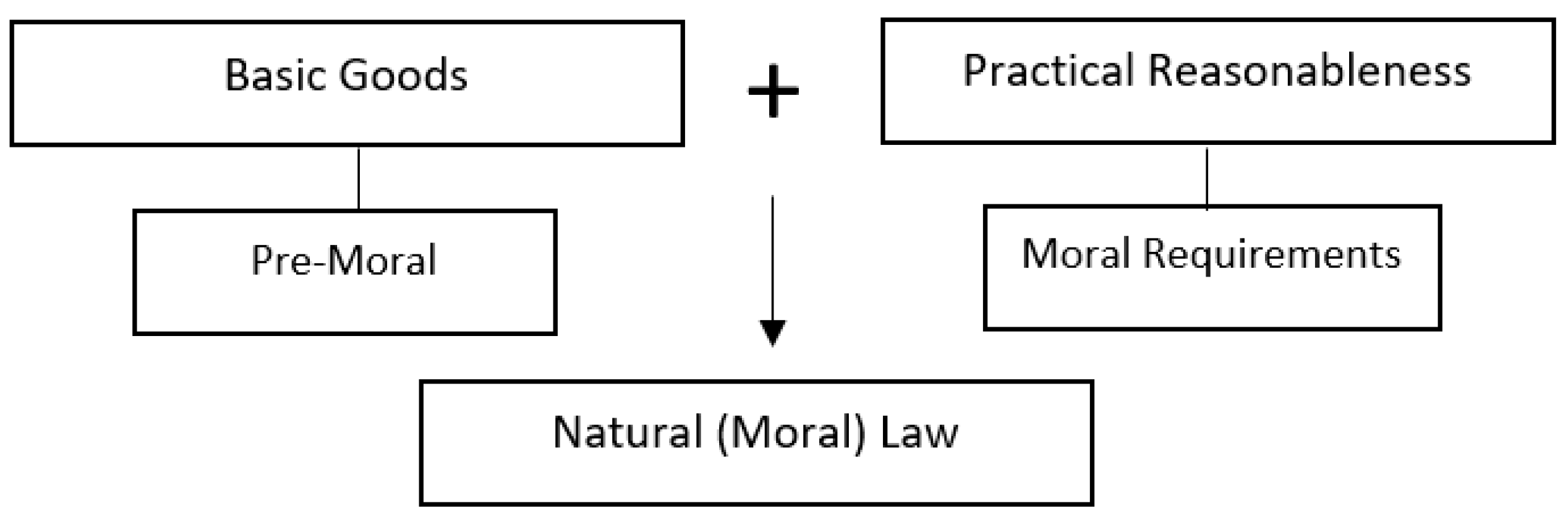

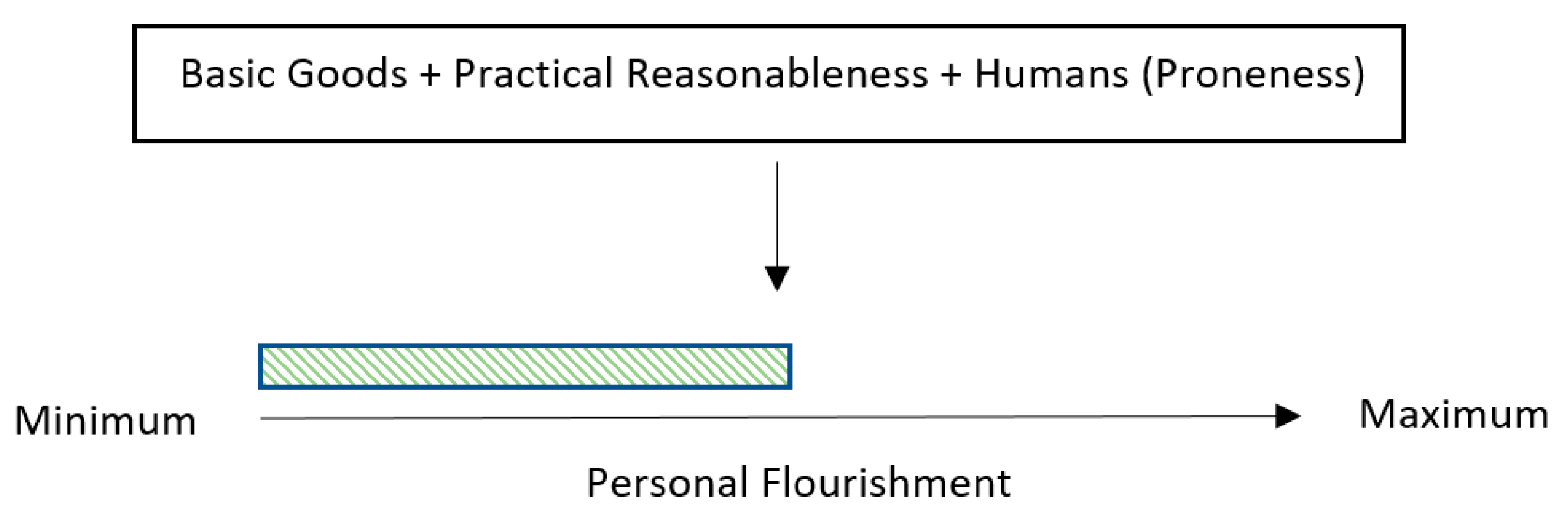

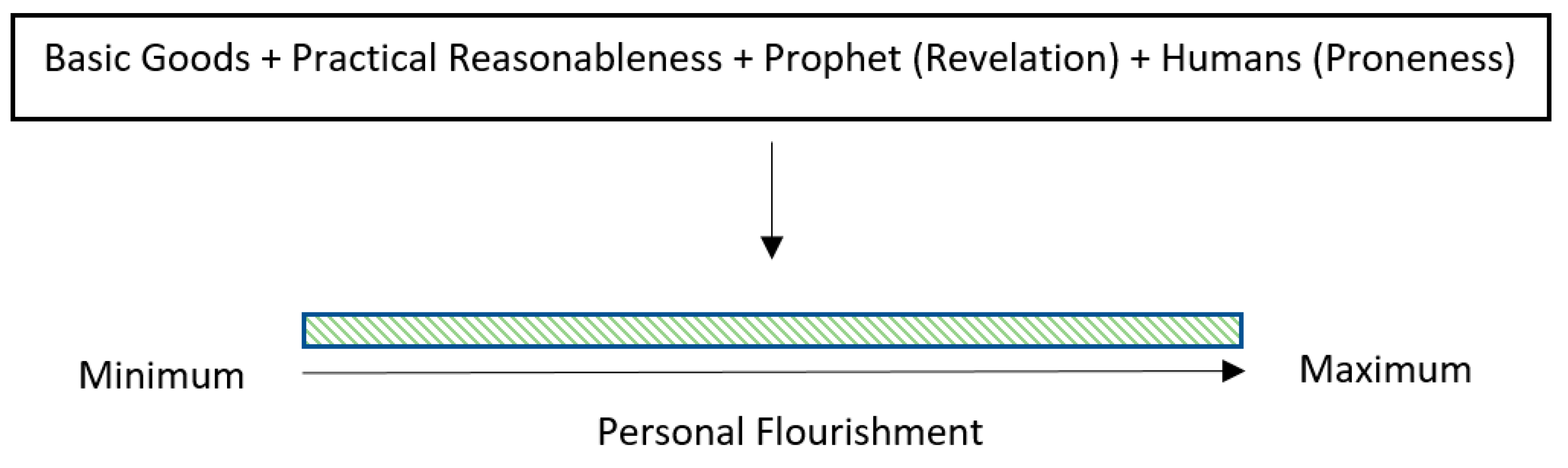

| God aims for humans to flourish personally, to the maximum level, by participating in the basic goods, in line with the requirements of practical reasonableness. |

2.1. The Nature of Natural Law: Basic Goods and Practical Reasonableness

|

|

2.2. Fulfilment of Personal Aim: Natural Law and a Prophet

encourage their children to do good actions by providing subsidiary motives for so doing, making it easier for their children to do good while they are young. Parents offer rewards for well-doing—both rewards of a crude material kind and the reward of their approval—and they threaten punishments—both of a crude material kind and the punishment of their disapproval.

the doctrine of creation might be expressed on the presupposition that the world was as described by the then current science, for instance, as a flat Earth, covered by a dome, above which was Heaven—“God made the Heaven and the Earth”. On the presupposition that the world came into existence 4000 years earlier, it would teach that it was then that God caused it to be. It would teach that God had made atonement for our sins, using the analogies of sacrifice and law familiar to those in the culture. It would teach the moral truths which those living in that culture needed to know (e.g., those concerned with whether people ought to pay taxes to the Roman emperor, or to obey the Jewish food laws); but it would contain no guidance on the morality of artificial insemination by donor, or medical research on embryos. It would offer the hope of Heaven to those who lived the right life. And it would express this hope using a presupposition of the culture that Heaven was situated spatially above the Earth.

New cultures always raise new questions of interpretation, and the consequences of unreformed old sentences for their concerns become unclear. Yet, sentences of a human language only have meaning to the extent to which its speakers can grasp that meaning; and as (being only human) they cannot conceive of all the possible concerns of future cultures, they cannot have sentences whose consequences for the concerns of those cultures are always clear.

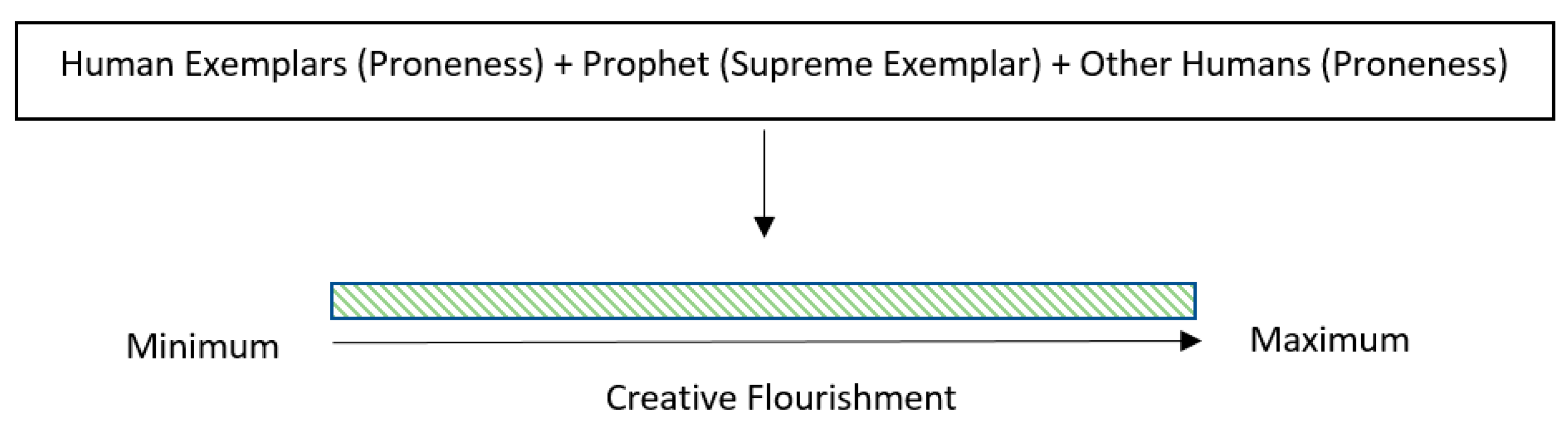

3. Creative Flourishment: The Divinity of the Prophet

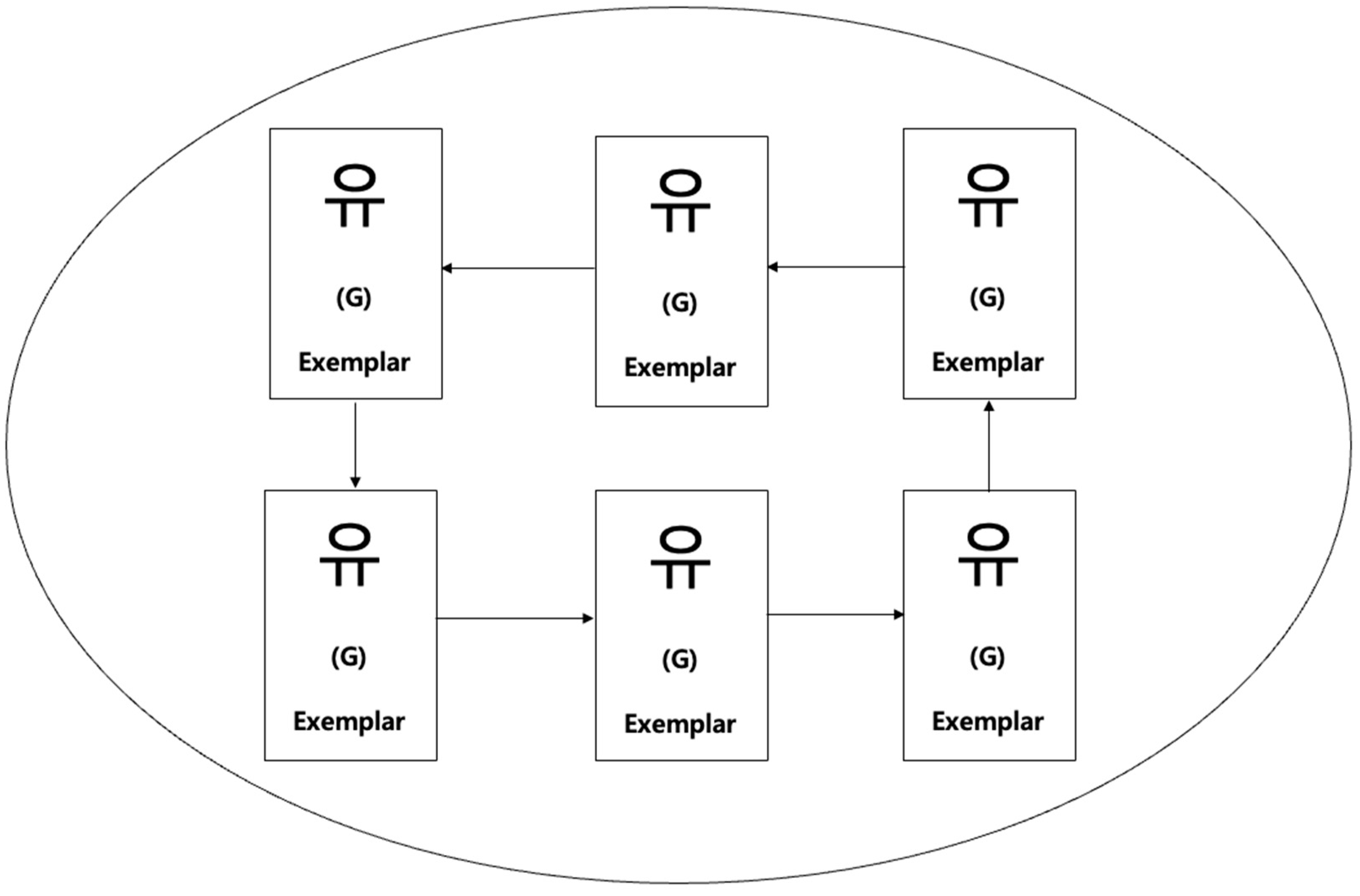

| God aims for humans to flourish creatively, to the maximum level, by participating as a ground of morality and sharer of goodness in the role of an exemplar. |

3.1. The Nature of Exemplarism

|

|

water cannot be ‘colorless, odorless liquid in the lakes and streams and falling from the sky,’ or any other description that we use in ordinary discourse to pick out water. That is because we can imagine that something other than water looked like water and fell from the sky and ran in the streams.

|

|

3.2. Fulfilment of Creative Aim: Exemplarism and a Divine Prophet

|

|

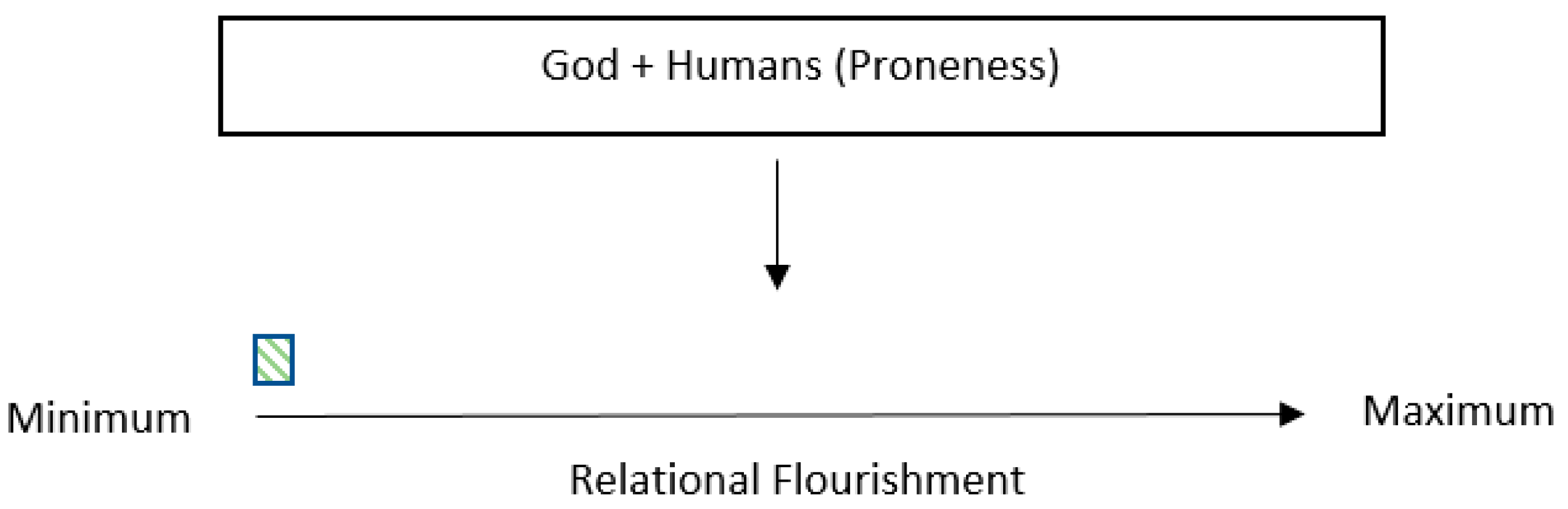

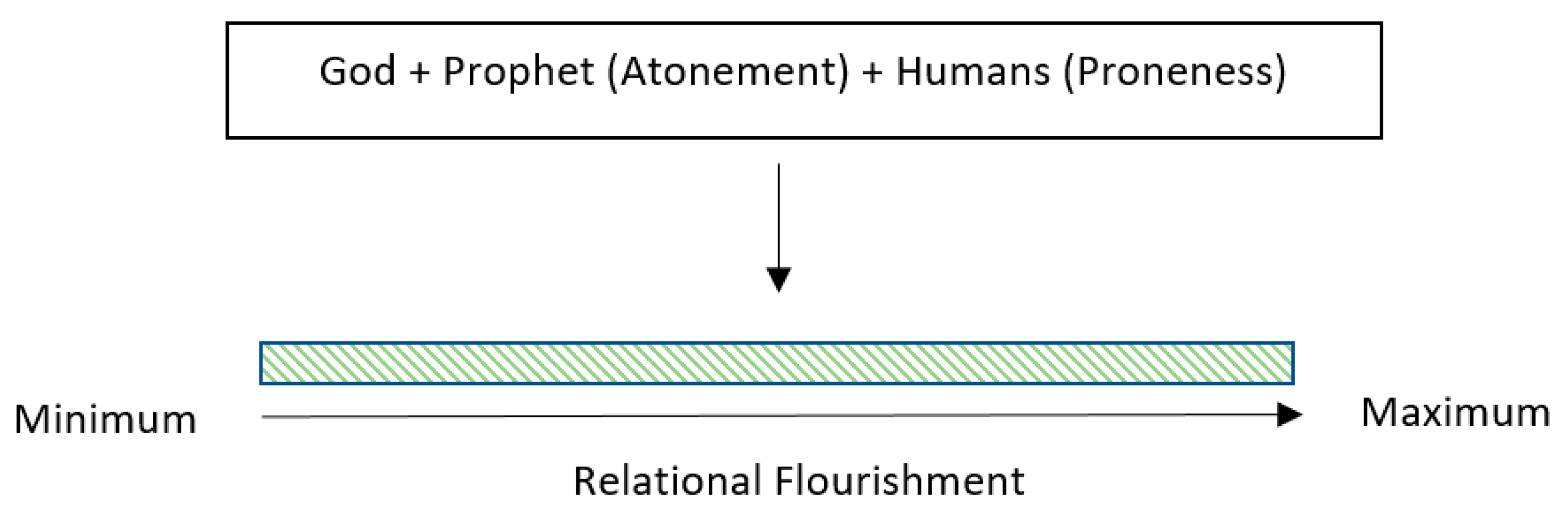

4. Relational Flourishment: The Atonement of the Prophet

| God aims for humans to flourish relationally, to the maximum level, by participating in an agápēic relationship with him. |

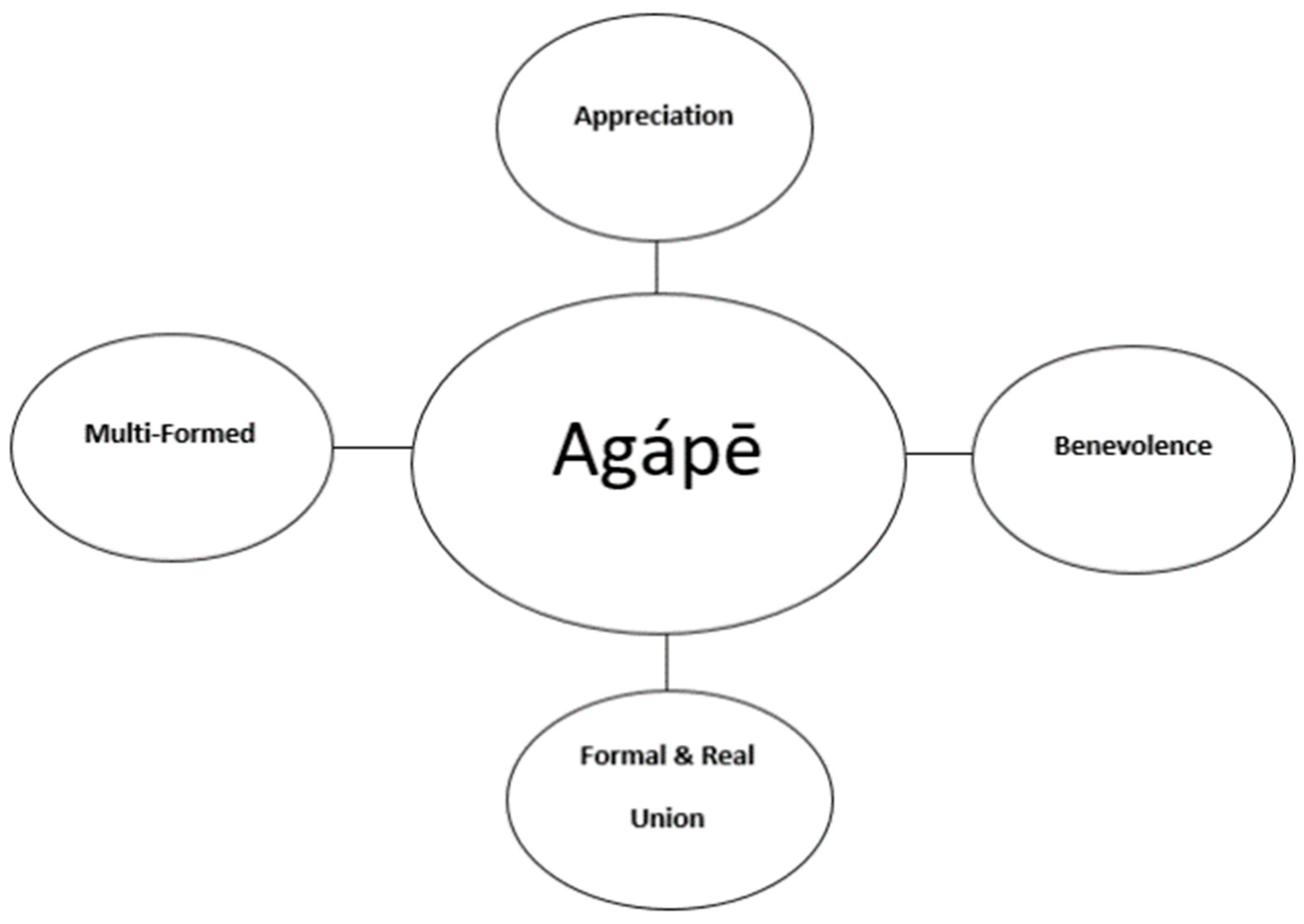

4.1. The Nature of Love: Multi-Formed Agápē

|

|

4.2. Fulfilment of Relational Aim: Agápē and Human Flourishment

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The other prominent Abrahamic religions are the Baháʼí Faith, Druze, Samaritanism and Rastafarianism. Despite these religions being included within the umbrella of Abrahamic religions, these religions will not be focused on in this article. |

| 2 | Though some Jews, and all Christians, would affirm the fact of the message of these prophets being for individuals of all nations. |

| 3 | I take the word ‘God’ here and throughout this article to refer to the one divine person: ‘the Father’, who is conceived of as the sole fundamental divine person. The usage of the term in this way, however, does not negate the possibility of there being other divine persons as well—such as that of the ‘Son’ (Christ). Nevertheless, the argument of this article, though not dependent upon any account of the doctrine of the Trinity, is best formulated within a Monarchical Trinitarian framework. For an explication of this view, see (Sijuwade 2021a). |

| 4 | These would be passages such as Romans 1:4 and 10:9. |

| 5 | As can be seen clearly in Islamic teaching in Surah An-Nisa 157. |

| 6 | Swinburne’s argument is focused on the ‘incarnation of God’, rather than the ‘sending of a divine prophet’. However, the difference between the position defended by his argument and that of this article is purely semantic. Nonetheless, the latter phrasing is to be preferred due to its helpfulness in emphasising the importance of the notion and role of a prophet in the Abrahamic religious framework—where, within the Christian framework, this notion being of such great importance that even Christ refers to himself in through this language in Mark 6:4. |

| 7 | One could ask the question of how something like the incarnation could be an act of essence—which would require the incarnation to be a necessary act that has always been the case—given the fact that the Son does not everlastingly assume a human nature but instead does so at a certain point in time (such as 4BCE)? Well, one can deal with this issue by assuming the classical conception of God’s relationship to time—that of divine timelessness, which allows one to affirm the fact of the Son having always been ‘incarnate’—as there is no temporal sequence in the life of a timeless being (i.e., all events that occur within its life are simultaneous); yet, the effects, or the completion, of these actions can still be present, and extended through time. A way to better understand this point has been put forward by Brian Leftow (2002, p. 297), where he utilises the notion of timelessness and ‘scattered temporal locations’, which helps to further clarify this point and deserves to be quoted in full:

Thus, in assuming this specific approach one can see how the incarnation could indeed be ae taken to be an act of essence. Thus, in taking this all into account, one can indeed affirm the reality of the incarnation (and atonement)—and the overall action of God sending a divine and atoning prophet into the world, as will be detailed below—as being a ‘timeless’ act of essence, even though the completion of these actions will take place over an extended period of time. |

| 8 | More on the nature of omnisubjectivity below. |

| 9 | These ‘strands’ (and aspects of his concept of divine revelation) will be utilised in various areas of the argument that is to be formulated in this article. |

| 10 | That is, the Flourishment Argument that will be formulated and presented throughout the rest of this article in an informal, rather than formal manner. |

| 11 | Specifically, God is an omnipotence-trope. For an explanation of this, see (Sijuwade 2021b). |

| 12 | Where, at a general level, to ‘flourish’ is to ‘develop successfully’, ‘to the fullest’ or to ‘thrive’. |

| 13 | This is not to say that there are not any altruistic desires; however, these types of desires operate alongside the selfish desires and are often weak. |

| 14 | Yet, as Swinburne (1989, p. 114) notes, the fact of moral belief is good as it ‘simply serves as the trigger which turns desires of certain sorts into a proneness to wrongdoing’. |

| 15 | It is important to note that there are indeed criticisms that can be (and have been) raised against each of the philosophical positions utilised in developing the Flourishment Argument—namely, that of Swinburne’s conception of free will (and the human condition), Finnis’ natural law, Zagzebski’s Exemplarism and Pruss’ conception of agápē (i.e., love). However, given that it will take us too far afield in detailing these criticisms, showing how one can deal with them, and how the aforementioned philosophers have also sought to do so, we can thus, again, assume a conditional position in this article of: if the conception of the human condition assumed here, the ethical theories of natural law and Exemplarism, and the notion agápē are cogent, then there is a successful argument in support of the Christian Position. Though it is important to note, as will be further detailed below, that the argument itself is not wholly wedded to these theories and notions and thus can indeed be re-cast within a different framework if one has issues with these them, and does not want to assume the conditional position put forward here. |

| 16 | Thus, even though the argument of this section will be detailed within the framework of natural law—due to its rigour and philosophical clarity—the central thesis of it—namely, that God will want humans to personally flourish by participating in basic goods—is not wholly tied to this theory and hence can be further developed within another ethical framework. Thus, if one takes issue with the theory of natural law, the argument of this section can still stand and be re-stated within another philosophical context. Furthermore, it is important to understand that even though the term ‘natural law’ theory is usually associated with that of ‘classical natural law’ theory, found in the work of St. Thomas Aquinas. The specific version of the natural law theory that is under focus here is that of what has been termed the ‘new natural law’ theory. However, for ease of writing, I will continue to simply refer to it as the natural law theory. |

| 17 | Which thus includes answers that do not necessarily involve a deity. |

| 18 | |

| 19 | These requirements are taken here to be basic and self-evident in the same way that the basic goods are. |

| 20 | With an intimate relationship with God being the needed sufficient condition that will be detailed below. |

| 21 | This, however, does not mean that this information has to be stated in the more philosophically precise way that Finnis did; thus, one should expect a statement concerning the goods and requirements of practical reason to be stated in the language, and conceptual structure, of the society that the revelation was provided within. More on the nature of a ‘culture-dependent’ revelation below. |

| 22 | And are in a relationship with God—this, however, is entailed by one fully participating in the basic good of religion. |

| 23 | For example, by one knowing that God is necessarily related to other ontologically equal divine persons, rather than him being an ontologically unique, solitary being, one would know that it is permissible to offer up worship to God through one of those divine persons. |

| 24 | The latter statement is found in (Swinburne 2016, p. 130). |

| 25 | Thus, again, even though the argument of this section will be detailed within the framework of Exemplarism—due to its rigour and philosophical clarity—the central thesis of it—namely, that God will want humans to participate in his creative activity of grounding morality and spreading goodness through living moral lives—is not wholly tied to this theory and hence can be further developed within another ethical framework. Thus, if one takes issue with the theory of Exemplarism, the argument of this section can still stand and be re-stated within another philosophical context. |

| 26 | Furthermore, according to Zagzebski (2017, p. 11), we can succeed in referring to water even if we associate the wrong descriptions with ‘water’, as what makes water ‘water’ is that it is H2O. However, the meaning of ‘water’ cannot be ‘H2O’ since people did not even have the concept of H2O, much less use it in explaining the meaning of “water”, until recent centuries. |

| 27 | Zagzebski finds the following model of emulation in the work of David Velleman (2007). |

| 28 | Zagzebski sources the general iteration of the simulation model from the work of Alvin Goldman (2008) and others. |

| 29 | Further detailing the relationship between these two theories will be the focus of future work. However, if one has issues in affirming both of these theories, then one can privilege that of Exemplarism, over the theory of natural law, as the holding of this theory (which requires sending a prophet as a supreme exemplar) will thus also entail the fact of God sending a prophet (i.e., an authoritative representative), though this prophet might not be tasked with the role of communicating a propositional revelation. Moreover, for a further explanation of the a posteriori necessity of morality within an Exemplarist framework, see (Zagzebski 2017). |

| 30 | Among the myriad other entities that God would see that is good to create as well. |

| 31 | I say ‘solely’ here to keep open the possibility of God providing a ‘partial’ moral code (e.g., the 10 Commandments) in addition to moral exemplars. |

| 32 | With a reminder that one does not have to make this assumption for the argument to hold. Moreover, I will regularly refer to the ontological perfect emulation of the prophet with God as that of him sharing his nature. |

| 33 | As well as those that are acquired in the face of difficulty, for this, see (Zagzebski 2017, pp. 30–40). |

| 34 | The modal term ‘might’ is emphasised here to highlight the fact that the possibility of this occurring is all that is needed for scepticism to rear its head, rather than that of it actually being the case that this occurs for this to happen. |

| 35 | Even though the prophet would not be able to perform a wrong action, his psychological state might be as such as to lead him to feel as though he could. In addition, though he would not have any proneness to wrongdoing, he indeed would be able to have a proneness to not perform any supererogatory actions or the best action (or equal best action), and thus would indeed face certain temptations not to as well (Swinburne 2008). |

| 36 | One could ask the question of whether the prophet argued for in the previous section has to be the same person as the divine person who is sent to fulfil the role of being a supreme exemplar? Yes, it is highly plausible that if God will inevitably send a prophet to accompany his propositional revelation and exercise an authoritative role in doing this, it is plausible that this specific individual would also be given the task of fulfilling the role of being the supreme exemplar that is the ground of morality, and provides the standard that enables other individuals to themselves to become exemplary. This is so because if God were to send the prophet to exercise an authoritative role over the communities formed by the propositional revelation that he has communicated, and the divine person sent by God were also to function as a supreme exemplar over all existing communities—and thus have a level of authority in them—then there could be a clash of authorities. Hence, it is plausibly the case that the prophet inevitably sent by God to communicate God’s propositional revelation is identical to the divine person inevitably sent by God to provide the standard of morality. |

| 37 | Though there has been a use of the notion of exemplarism here, this is not to be confused with the notion of exemplarism that is utilised by theologians to form the ‘Moral Exemplar Theory of Atonement’. As the notion of atonement that will be utilised in the next section does not rely on the prophet’s atoning act simply being that of him being a moral exemplar; rather, as will be shown, the atonement is taken to have an ontological effect. Nevertheless, for a helpful detailing of the Exemplar Theory of Atonement, see (Quinn 1993). |

| 38 | Thus, again, even though the argument of this section will be detailed within an agápēic framework—due to its clarity and theological plausibility—the central thesis of it—namely, that God will want humans to be in an everlasting relationship of love with him—is not wholly tied to this framework and hence can be further developed within another theoretical framework. Thus, if one takes issue with the concept of agapē, the argument of this section can still stand and be re-stated within another philosophical context. |

| 39 | Despite love being such as to include a determination of the will that involves appreciation, goodwill and union, it is important to note that love is not experienced as these features, but is a single thing (Pruss 2013, p. 24). |

| 40 | Therefore, if one of these aspects is missing in a relationship, then it is not an agápēic (love) relationship. |

| 41 | The first two aspects of love will not vary drastically between the different forms of love—one can appreciate the same good of an individual in a romantic, filial and fraternal context, and the very same goods can also be willed within these contexts as well. |

| 42 | More on this notion below. |

| 43 | In this section, I will be interchanging between the term ‘agapē’ and ‘love’ throughout without any change in meaning. |

| 44 | For a further detailing of the nature of omnisubjectivity, see (Zagzebski 2013b). |

| 45 | For a further detailing of the nature of omniscience, see (Swinburne 2016). |

| 46 | The following is a brief explication of elements of the Agápēic Theory of Atonement that features in (Sijuwade Forthcoming). At a general level, the Atonement is the authoritative and definitive teaching of Christianity, and thus, on this basis, some positions concerning the nature and work of Christ (i.e., the prophet) that deny the veracity of this teaching—that is, that deny the fact that Christ’s life, death and resurrection saves humans from sin and reconciles them to God—are to be ruled out as ‘unorthodox’. Yet, as there is no authoritative and definitive stance on how to best interpret this teaching, it is possible for there to be a number of different interpretations that can each be classed as ‘orthodox’ interpretations of the doctrine. More specifically, in the field of contemporary ‘analytic theology’, certain individuals have sought to propose particular ‘theories’ of the Atonement that provide an explanation of how Christ’s life, death and resurrection saves humans from sin and reconciles them to God. These have ranged from Anselmian approaches, as expressed by Swinburne (1994), through Eastern Orthodox approaches, as expressed by Robin Collins (2011), to Thomistic approaches, as expressed by Eleonore Stump (2018). At a specific level, the Agápēic Theory of Atonement draws from these three types of approaches and seeks to show how Christ’s life, death and resurrection saves humans from sin and reconciles them to God, within a specific theoretical framework that takes God to have the desire for humans to flourish to the maximum level by partaking in an everlasting relationship of love (agápē) with him. Yet, given the ‘human condition’, all humans face a problem that stops them from entering this relationship with God. Hence, the atoning work of Christ provides the necessary means for dealing with this problem and enabling all humans to enter into an ‘agápēic relationship’ with God, and thus truly flourish to the maximum level. |

| 47 | More on this in the next section. |

| 48 | This assumes the ‘Barthian’ idea that the prophet (‘the Son’) was pre-temporally elected by God to fulfill his role—and thus is the ‘Elected One’ and was thus also deemed pre-temporally the ‘Rejected One’ in anticipation of the sins that he would take on during his death. |

| 49 | The distinction between dimensions was introduced in earlier sections of this article. I leave the metaphysics of this ‘spiritual’ death open. |

| 50 | Stump (2018) refers to this as the ‘Holy Spirit’; however, to ward off the requirement to establish the veracity of the doctrine of the Trinity and to promote some of neutrality between the ARs, I will refer to this entity as ‘God’s spirit’, without any assumption that this is a personal entity. Moreover, even though words such as ‘justification’ and ‘sanctification’ have been used here, these terms are not necessarily to be itnerpreted in a Christian manner—and thus I use the terms, again, in a theologically neutral manner. |

| 51 | Though terms like ‘grace’, ‘justification’ and ‘sanctification’ have been used here this does not mean, however, that one should interpret them in a Christian manner, given the a priori nature of the argument that has been proposed in this article. |

References

- Collins, Robin. 2000. Girard and Atonement: An Incarnational Theory of Mimetic Participation. In Violence Renounced: Rene Girard, Biblical Studies and Peacemaking. Edited by Willard Swartley. Telford: Cascadia Publishing House, pp. 132–53. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Robin. 2011. An Incarnational Theory of Atonement. Available online: https://home.messiah.edu/~rcollins/Philosophical%20Theology/Atonement/Incarnational%20Theory%20of%20Atonement%2010-2-09%20version.doc (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Finnis, John. 2011. Natural Law and Natural Rights, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Alvin I. 2008. Simulating Minds: The Philosophy, Psychology, and Neuroscience of Mind-Reading. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kripke, Saul. 1980. Naming and Necessity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Leftow, Brian. 2002. A Timeless God Incarnate. In The Incarnation. Edited by Stephen T. Davis, Daniel Kendall and Gerald O’Collins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 273–99. [Google Scholar]

- Pruss, Alexander. 2008. One Body: Reflections on Christian Sexual Ethics. Available online: http://alexanderpruss.com/papers/OneBody-talk.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Pruss, Alexander. 2013. One Body: An Essay in Christian Ethics. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Hilary. 1975. The meaning of “meaning”. In Language, Mind and Knowledge: Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Edited by Keith Gunderson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Phillip. 1993. Abelard on Atonement: Nothing Unintelligible, Arbitrary, Illogical, or Immoral about It. In Reasoned Faith. Edited by Eleonore Stump. New York: Cornell University Press, pp. 290–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sijuwade, Joshua R. 2021a. Building the monarchy of the Father. Religious Studies 58: 436–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijuwade, Joshua R. 2021b. Divine Simplicity: The Aspectival Account. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion 14: 143–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sijuwade, Joshua R. Forthcoming. Atonement: The Agápēic Theory. Theophron.

- Stump, Eleonore. 2012. Providence and the Problem of Evil. In The Oxford Handbook of Aquinas. Edited by Brian Davies and Eleonore Stump. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 401–17. [Google Scholar]

- Stump, Eleonore. 2013. Omnipresence, Indwelling, and the Second-Personal. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion 5: 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stump, Eleonore. 2017. The Problem of Evil and Atonement. In Being, Freedom, and Method: Themes from the Philosophy of Peter van Inwagen. Edited by John A. Keller. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 186–208. [Google Scholar]

- Stump, Eleonore. 2018. Atonement. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 1989. Responsibility and Atonement. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 1994. The Christian God. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 1997. Providence and the Problem of Evil. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2003. The Resurrection of God Incarnate. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2004. The Existence of God, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2007. Revelation, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2008. Was Jesus God? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2010. Is There a God? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2016. The Coherence of Theism, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Velleman, J. David. 2007. Motivation by Ideal. In Philosophy of Education: An Anthology. Edited by Randall Curren. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 517–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2004. Divine Motivation Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2010. Exemplarist Virtue Theory. Metaphilosophy 41: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2013a. Moral exemplars in theory and practice. Theory and Research in Education 11: 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2013b. Omnisubjectivity: A Defense of a Divine Attribute. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2015. Exemplarism and admiration. In Character: New Directions from Philosophy, Psychology, and Theology. Edited by Christian B. Miller, R. Michael Furr, Angela Knobel and William Fleeson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 251–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2016. Divine Motivation Theory and Exemplarism. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion 8: 109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2017. Exemplarist Moral Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2022. God, Knowledge and the Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zagzebski, Linda. n.d. God as Supreme Exemplar. In The Moral Argument for the Existence of God. Edited by John Hare and David Baggett. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sijuwade, J.R. The Necessity of an Incarnate Prophet. Religions 2023, 14, 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14080961

Sijuwade JR. The Necessity of an Incarnate Prophet. Religions. 2023; 14(8):961. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14080961

Chicago/Turabian StyleSijuwade, Joshua R. 2023. "The Necessity of an Incarnate Prophet" Religions 14, no. 8: 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14080961

APA StyleSijuwade, J. R. (2023). The Necessity of an Incarnate Prophet. Religions, 14(8), 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14080961