Abstract

One of the most important areas of tension for diaconia in the Western European, German-speaking context is the demands of an interreligious and plural society. The social challenges to churches with their congregations and parishes, diaconal organizations, and the state with its social institutions are complex. This article deals with religious layers of social transformations that shape helping actions. It focuses on innovative projects in the field of spiritual care and diaconia that created new spaces of diaconal practice in the last ten years in the Canton of Zurich and Switzerland. Specifically, the process of accrediting the first imam at the University Hospital in Zurich, the employment of chaplains of Muslim and Jewish faith in the Swiss Army, and the training of Muslim chaplains in the Canton of Zurich are presented. On the one hand, the aim is to adequately define the relationship between diaconia and spiritual care in a pluralistic society. On the other hand, interreligious cooperation is analyzed as a process of intercultural communication and transcultural practice. From this, theses for prospective, innovative, and well-founded interreligious cooperation in diaconia can be gained, which can be further developed and discussed in other European and global contexts.

1. Introduction1

People in distress want to be accompanied and supported in mind, body, and spirit. If psychological, physical, and spiritual distress arises in the individual, it is often triggered or shaped by stress in family situations, social hotspots, traumatic experiences that arose in the experience with others, or the consequences of social crises such as pandemics, war, and poverty. In the 21st century, spiritual care for the individual can no longer occur without extending to social constellations, institutional organizations, and social transformations. Helping always happens in social spaces. Diaconal practice, as help interpreted in Christian terms, rediscovers itself as an agent of public theology and public diaconia in social settings (Eurich 2020, pp. 117–34; Moos 2023, pp. 165–80).2 According to Rüegger and Sigrist (2011, p. 38): “Helping can be defined in a very general formal way as intervention by one actor in favor of another—to achieve a goal represented by the latter. In the social sphere, such an intervention usually takes place as a contribution to the elimination of a problem situation or to the satisfaction of a basic need that cannot be satisfied without outside help” (Rüegger and Sigrist 2011, p. 38).

Concern for individual souls and the collective need of whole groups of people are increasingly resonating with each other in recent decades. Different forms of diaconal spiritual care are emerging in the 21st century (Götzelmann et al. 2006). The term “diaconal spiritual care” was taught by the resistance fighter, theologian, and pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer in his “ashram” in Finkenwalde, in his brotherhood with aspiring pastors and theologians in Nazi Germany, in order to locate social and spiritual help, proclamation, education, and community life in the social context (Zimmermann-Wolf 1991; Rüegger 1993; Bobert-Stützel 1995).

Society today in the Western European context has become plural, multi-religious, and diverse. Spiritual care, as well as religiously based help practice, such as diaconal practice, is not only, but to a great extent, sensitive to the religious needs of people in need. Such needs often occur at biographical thresholds, existential questions, or psychological stress. Due to the change in social as well as family structures, an increasing demand for professional offers of specifically Muslim spiritual care and religious accompaniment becomes visible in Europe and Muslim countries (Ucak-Ekinci 2019). This need is also expanding to other religious and ideological imprints. Diaconal spiritual care as professional help is to be increasingly if not already fundamentally, trained in interreligious cooperation. Professional assistance is understood to mean: Trained chaplains work in institutional contexts with clients entrusted to their care.

In Switzerland, spiritual care and diaconal services are provided by churches, diaconal ministries, and organizations in the local social sphere, in cantons, and throughout Switzerland, as well as on a global scale. In public and state institutions, the responsibility for spiritual care lies with the cantonally3 recognized churches and religious communities. In Switzerland, diaconal services are primarily seen in the form of community work in interaction with others involved (Dietz and Sigrist 2022). Spiritual care services, which are mostly provided by the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches of the cantons, are open not only to Christians but also to people of other religions if they so desire. Due to the ever-increasing number of requests for specifically Muslim religious accompaniment in crises, death, or rituals, Christian chaplains are reaching their limits. In order to provide a minimum service, hospitals, and prisons, including the army, began to compile lists of contacts with Muslim and Jewish communities, rabbis, and imams. Such lists are hardly known by patients and inmates. In recent years, steps have been taken to fundamentally design and introduce the offer of qualified spiritual care in interreligious cooperation with various cantons and public institutions (Schmid et al. 2018).

Since diaconia, with special regard to its subcategory diaconal spiritual care, has a particular affinity to religious needs and forms of accompaniment of people in need, the question arises about how interreligious cooperation is to be designed currently and in the future with the specific Swiss challenges posed by the federalist culture with the complex relationship between cantons and the federal government. It is typical for Switzerland that the relationship between church and state is regulated differently in each canton. As a rule, the institutional bodies under public law called national churches, are responsible for spiritual care in homes, hospitals, prisons, and asylum centers. Responsible means that they hire and pay professional chaplains. In certain cantons, the state can assign this task to the church by means of compensation and an agreed service contract (e.g., in the Canton of Zurich).

The article contributes to the interface of diaconal and spiritual dimensions in public life, focused from an interreligious perspective and observations from practice. It analyzes three projects on diaconal spiritual care realized in the canton of Zurich and Switzerland from the perspective of interreligious cooperation. The article begins with a description of some cultural aspects of helping. This is followed by a discussion of the case studies. Finally, practical experiences are summarized with regard to interreligious cooperation in the context of diaconal practice.

2. Theoretical Approach

2.1. Religious Landscape of Switzerland

Interreligious cooperation is fundamental for helping society as a diaconal practice because social coexistence has simply become plural, interreligious, and multicultural. The religious landscape of Switzerland has changed massively in the last 50 years.4

In 1970, a good 4.5 million people lived permanently in Switzerland aged 15 and over. Of these people, 48.8% were members of the Protestant Reformed Church and 46.7% were members of the Roman Catholic Church. Other Christian churches and faith communities with Jewish and Muslim backgrounds or people with no religious background were recorded in the low-digit percentage range of 0.1–2.0%.

In 2021, a good 7.2 million people aged 15 and over lived in Switzerland as permanent residents. While the members of the Evangelical Reformed Church made up the majority of the population in 1970, the majority are now people without religious affiliation, with 32.3%, corresponding to just under 2.1 million people. The Evangelical Reformed Church has become a minority, with 21.1% of all people comprising its membership, which is a good 1.6 million people. The Roman Catholic Church is also not much larger, with 32.9% members. This corresponds to just under 2.5 million people. Members of Islamic communities accounted for 5.7% of the total, corresponding to just under 400,000 people in Switzerland. Members of Jewish religious communities accounted for 0.2% of the total population or just under 17,000 people. Members of other religious communities accounted for a total of 1.3%. This includes a good 37,000 people from Buddhist associations and just under 40,000 people from Hindu associations.

In 2021, a good 15,000 people with other religions lived in Switzerland, corresponding to 1.3% of the population. 5.6% of the population were members of other Christian denominations: just under 35,000 people count themselves among the (neo)pietist and evangelical groups. A good 26,500 people belong to the Pentecostal movement and other charismatic congregations. A good 26,000 people were members of end-time churches, and a good 18,000 people belonged to apostolic churches. A good 81,000 people were members of other churches dating back to the Reformation. A good 185,000 people were members of the Christian Old Oriental and Christian Orthodox churches. The Christian Catholic Church had a good 8,200 members and the religious affiliation of almost 82,000 people was unknown.

Within 50 years, a dramatic cultural transformation occurred in the religious landscape of Switzerland. Although Christian affiliation still makes up a slight majority of the population, there is a shift away from the two large, denominational church carpets with scraps of fabric lying around that were hardly noticed to a colorful patchwork carpet with fabrics of exclusively religious minorities.5 Swiss society became a diverse culture, shaped and challenged by a conglomerate of religious subcultures. Christian spiritual care and diaconal practice are thus themselves drawn into challenging transformation processes. The question that arises is to what extent this religious patchwork affects the offers of spiritual care and diaconia.

2.2. Cultural Coherence of Helping Actions

The decrease in denominational attachment of religious or spiritual needs, often fuzzily felt and diffusely described, to the institution of the church is part of religious pluralism. Christian faith articulates itself to take up the image of the patchwork quilt, weaving dogmatic, traditional threads with charismatic, innovative fabrics into new patterns of beliefs, rites, and ethical convictions. In this way, a culture of faith emerges that is open to the foreign and, at the same time, shapes new forms of its own identity. Ever since the beginning of Christianity, new forms of faith have repeatedly combined with traditional ideas of cultural memory. This process of merging different ideas and images into new structures and interpretations is attempted to be grasped in practical theology with the term “cultural coherence” (Jörns 2007). Diaconal science uses this term to describe helping as diaconal practice in a deconfessionalized context. It is about discovering diaconia in a plural society’s colorful, cultural network of lifeworlds as fabric on which it embroiders together with threads of differently culturally tuned and differently religiously motivated practices (Sigrist 2020, pp. 90–92). This also means that Christianity and the Christian faith, like diaconia, have developed in these cultural contexts. A specifically Christian justification of helping action as diaconia can, of course, also be made under this aspect.

Cultural coherence of helping practices has always been a consequence of religious pluralism. However, there has never been a “pure”, understood, exclusively “Christian”-based, diaconal practice. Every form of diaconia has always been linked to the cultural context of its time in such a way that more or less formative interpretations of diaconal practice emerged from it. From the earliest Christian times to the present day, Christians have woven coherent and concise patterns from different materials to help cultures. This has resulted in art, as it were, of continually redesigning diaconal practice inwardly in Christian culture and outwardly in a pluralistic society.

In a few strokes, the current artwork of diaconal practice will be sketched. “Caring and helping are universally human phenomena; indeed, they originate in human biology” (Weiss 2005b, p. 19). First, diaconal practice is, generally, a helping action. Constitutively, not exclusively, this general human action becomes Christian practice, in which not the helping person but the person in need comes into view. This corresponds to the creation-technological approach as Rüegger and Sigrist have designed it (e.g., in Rüegger and Sigrist 2011, pp. 115–86). It is the gaze of the other, “the gaze of the needy, that constitutes the identity of the helper” (Morgenthaler 2005, p. 45). In this context, the narrative biblical story stream serves as a pattern for interpretive and inspirational sketches with Christian connotations. In today’s pluralistic and multi-religious social context, Christian reasoning contents (such as christological, mission-theological, pneumatological, eschatological, and ecclesiological justifications6) for helping are coming under increasing pressure; they are hardly understood anymore, and are less and less transmitted. In addition: “Christians do not have a patent on mercy”. Caritas has emigrated from the church as “cura” and has become a therapeutic cure in its thousand different modern forms” (Morgenthaler 2005, p. 49). From this follows, according to Morgenthaler: “Always new necessary (…) is the reflection of the contextual context of the helping action” (Morgenthaler 2005, p. 50).

The contextual context of helping action leads to an interesting dynamic in the 21st century. For the “secret guiding type of helping” postulated, or rather assumed, by Morgenthaler, which is based on “Western European, middle-class oriented Christianity” (Morgenthaler 2005, p. 50), has been properly shaken by the transformations in the religious landscape. Cultural coherence in helping is confronted with two challenges: on one hand, religious and social needs increasingly flow into each other, and the boundaries between spiritual care and diaconal practice are becoming more and more permeable within the different professions and more complex professional activity; on the other hand, interreligious cooperation itself is undergoing exciting transformations.

2.3. Diaconal Spiritual Care

The term “diaconal spiritual care” has been used by diaconal scholars in recent years in an attempt to describe the phenomenon of the fluid boundaries between spiritual care and diaconia (Götzelmann 2006, pp. 18–50). Spiritual care as a one-on-one conversation in the form of confession, repentance, and accompaniment in crises, as religious life and faith counseling, has always been an important, constitutive part of the Christian and church self-understanding. Diaconia, as Christian-based and motivated social work in the community, parishes, and social institutions, is one of the fundamental fields of action of being a church. How can both forms of expression of Christian existence and church life be assigned to each other? The diaconal scholar Arnd Götzelmann distinguishes between four models of classification and prioritizes spiritual care and diaconia as overlapping and equally different dimensions. In doing so, Götzelmann emphasizes the close connection between diaconal forms of spiritual care and spiritual forms of diaconia. Both are congruent, and both complement each other with respect to a holistic anthropology, in which the Christian attention to the neighbor allows questions of meaning and spirituality, like the concerns for life and survival, to flow into each other. Diaconia cannot be fixed on social needs and spirituality, not only on narrowly defined spiritual needs. Body care, care, and spiritual care are three aspects of the one (Götzelmann 2006, pp. 48–49).

The pastoral-spiritual dimensions of diaconal practice are highly compatible with interreligious cooperation. According to Helmut Weiss, spiritual care can be understood as a “helping conversation on questions of life”. Weiss mentions that questions of life always have religious dimensions in their existential meaningfulness. He also understands religion as helping people to cope with life issues. According to Weiss, spiritual care cannot detach itself from spiritual and religious implications. Therefore, for Christian spiritual care workers, it is a professional attitude in their work in which statements of the counterpart are to be interpreted as trust in God or as an interpretation of life. Spiritual care cannot be separated from the spiritual dimension (Weiss 2005a, pp. 245–46). The terms “religious” and “spiritual” overlap in everyday language. This spiritual dimension, for its part, is now increasingly resonating through the transformation of the religious landscape with its different religious communities and their explicitly religious life in Switzerland. In particular, it resonates with the nearly 400,000 members of Islamic communities. This is because accompanying and helping people in need is a religious duty in Islamic culture, based on the teachings of the Koran and the work of the Prophet Muhammad (Tittus-Düzcan 2018). Christian members of the free church, evangelical, and charismatic congregations in Switzerland also increasingly link social duty and religious practice, not least through their strong socialization programs (Stolz et al. 2014, pp. 54–56). In addition, spiritual dimensions are increasingly coming into view in health care (Peng-Keller 2019, pp. 13–72).

In the pluralistic society of Western Europe, trained employees in diaconal spiritual care cannot close their minds to interreligious cooperation because of their professionalism. The question that now arises is the quality of such cooperation.

2.4. From Intercultural Communication to Transcultural Practice

Looking at interreligious cooperation in Muslim spiritual care, the Catholic theologian and director of the Swiss Center for Islam and Society (SZIG) at the University of Fribourg, Hansjörg Schmid, and his research team observed a process away from intercultural communication towards transcultural practice (Lang et al. 2019). What is at stake? Culture and interculturality are dynamic processes, not static positionings. Philosopher Wolfgang Welsch talks about “transcultural societies” (Welsch 2005). The Swiss ethnomusicologist Max Peter Baumann sums up this change in perspective, which focuses less on communication between “cultures” and more on the changes in the individual cultural spheres themselves: “Transculture in this sense is transverse to space and time; it is a culture of mixing and transforming (…). In the ‘global village’ of today, the processes of intercultural and transnational permeability are based on the effects of accelerated globalization and its homogenizing, at the same time also fragmenting and hybridizing moments” (Baumann 2019, p. 64). Such hybridizing moments of transculture do not level all cultural differences into a uniform mush, but on the contrary, expose experiences of difference in cultural and religious spheres. Experiences of difference prevent one from speaking of “Islam” or “Judaism” in a generalized way, thus avoiding the traps of politically instrumentalizing or publicly proclaiming collective cultural ascriptions. Andrea Lang, Hansjörg Schmid, and Amir Sheikhzadegan state that the public dispute about collective identities is dominated by intercultural dialogue with Islam. They also state a tendency in recent times that in functional subsystems, Muslims concretely activate their dialogue in order to practice aspects of a successful life. This practice also includes interreligious communication in spiritual care (cf. Lang et al. 2019, p. 369).

Pragmatic solutions can become indicators of a transcultural practice as they represent an attempt to enter into dialogue with people in need, with their transculturality full of holistic needs of body, mind, and spirit. Diaconia, especially in its specific form of diaconal spiritual care, transforms itself towards a transcultural practice that fundamentally builds a new architecture of interreligious and intercultural cooperation. This transcultural practice has an impact on diaconia as a helping activity in the way that different cultural instruments of help in the area of supporting, accompanying, and explicitly religious practices flow into each other. This results in new cooperation between spiritual care workers with different religious orientations.

3. First Practical Experience

3.1. First Imam as Chaplain at Zurich University Hospital

The first case study points to a specific Zurich feature of interreligious cooperation, which has its challenges. The initiative to construct a new architecture of professional chaplaincy in public hospitals with Muslim chaplaincy did not come from the established churches or religious communities but from the state itself. In particular, Cantonal Councilor Jacqueline Fehr, head of the Directorate of Justice and Home Affairs, is the driving force behind the seven guiding principles launched in 2017 by the Zurich Cantonal Council to serve as a basis for public, societal discussion about the relationship between the state and religion.

For Jacqueline Fehr, the starting point is the transformation of the religious landscape in the canton of Zurich. For her, as the government councilor, a transparent and regulated relationship with all religious communities is important. Not only the Christian churches with their Protestant Reformed, Roman Catholic, and Christian Catholic denominations, but all religious communities have become minorities. In December 2017, the government council published seven guiding principles in this regard. These sentences describe the social significance of religious communities, the future relationship between the state and religion, and possible ways of including unrecognized religious communities (Kt. Zürich 2022).

In the publication of 2017 (Kt. Zürich 2017), the government under Jacqueline Fehr summarizes the work priorities under the following seven guiding principles:

1. Religious beliefs are part of the foundation of society.

2. Religious communities contribute to public peace.

3. Religious symbols visible in the public sphere are subject to the state’s legal system.

4. The state legal system applies to all religious communities.

5. The state legal order of Switzerland and the Canton of Zurich is determined by a democratic-liberal culture.

6. The recognition under public law of the Protestant Reformed Church, the Roman Catholic Church of the Canton of Zurich, the Christian Catholic Church, and the two Jewish communities has been established.

From my point of view, four aspects of this political initiative are worth highlighting for interreligious cooperation. The initiative proceeds from pragmatic solutions.7. Clear foundations must be created with regard to the religious communities that are not recognized under constitutional law.7

Firstly, Jacqueline Fehr comments that such an initiative is based on pragmatic solutions that reflect the liberal and democratic culture of social life in the Canton of Zurich. This pragmatic basic attitude enables steps for inclusive coexistence (Kt. Zürich 2022).

Secondly, religion is a decisive orientation factor in social coexistence. For the Government Council under Jacqueline Fehr, religious communities, as well as religious sentiment, represent a great resource in the social context. This great interest is to be appreciated because the strong changes in the religious landscape, namely in the dramatically increasing number of people without religious affiliation, force politics and the state to adapt to this transformation towards pluralistic religiosity. This is also why politicians, churches, and religious communities have increasingly met for constructive discussions (Kt. Zürich 2022).

Thirdly, historical reasons shape this political process. Since the Reformation, the connection between the Protestant Reformed Church and the state has been close. From the beginning, the political leadership of the time was also substantially involved in religious and ecclesiastical issues. The instrument of such participation lay in the so-called disputations (since 1523), a vessel in which clerical and noble citizens discussed with each other Zwingli’s new way of understanding the church. More pointedly: What was right and good in Zwingli’s teaching was decided by political power. Conversely, Zwingli strongly influenced the political changes. In other words, the reformation of the church was the transformation of society (Kt. Zürich 2022).

Fourthly, a breakthrough in interfaith cooperation in the canton of Zurich occurred in 2017 with the accreditation of the first imam as a chaplain at the University Hospital in Zurich. Spiritual care is spreading out of the narrow ecclesiastical framework into the social environment. In 2017, the association Quality Assurance of Muslim Spiritual Care in Public Institutions (German: Muslimische Seelsorge Zürich; acronym: QuaMS) was founded. The sponsorship of the association sits in the representation of the Directorate of Justice and Interior of the Canton of Zurich. Uniquely, the policy works strategically and operationally together with the representatives of the Muslim experts (cf. Kt. Zürich 2022).

Muris Begovic is the first Iman accredited at the University Hospital Zurich since 2017. He is a stroke of luck for interreligious cooperation in diaconal spiritual care and, at the same time, a living example of biographical transculturality:

“It (diversity, add. CS) is an opportunity for every citizen because everyone is given the chance to participate in society. So, it is also for me, with all my backgrounds that I bring and that make me a personality, a recognition. Muslim, Imam, chaplain, Swiss, Bosnian, Toggenburg, Zurich, son, grandson, uncle, husband, father, friend, and now army chaplain. Behind each of these designations, there is always a human being. Because only the human being manages to be so many things in one person”(Begovic 2022)

With this biography, Begovic represents the approximately 500,000 Muslim women in Switzerland. He shows possibilities for how participation in society becomes possible for Muslims. This possibility of participation means a lot to Begovic as a Swiss Muslim and Imam (Begovic 2022).

In this personal statement, which Begovic made in connection with the training for army chaplaincy, he points to an extremely important aspect of transcultural practice in diaconal chaplaincy: transcultural practice leads to the experience of recognition and participation in society for those who help as well as for those who receive help. More precisely: participation and inclusion have become constitutive, transcultural resonance spaces of diaconal practice in a plural society. In Switzerland, participation and inclusion have been discussed controversially and diversely in different votes (headscarf debate and minaret initiative8) in society until today. In the future, the political question of how migration should succeed in Switzerland will continue to be a matter of concern. To participate on an equal footing with others in the development of spiritual care in social institutions, prisons, and diaconal works—with the statements of Muris Begovic, we have come to a first thread of future interreligious cooperation in diaconal work: Diaconia and interfaith cooperation leads to the participation of pastors and diaconal workers of different religions.

In Switzerland, for example, corresponding projects have been initiated in various cantons over the past five years, not only in Zurich but also the cantonal hospital of St. Gallen has a group of Muslim chaplains present on Friday afternoons in a pilot project. In the canton of Vaud, the Muslim Association (UVAM) is seeking public recognition. As a consequence, access to institutionalized spiritual care would be possible (Hehli 2018). Again, it should be emphasized: in Zurich, it is the state that, in cooperation with the corresponding Muslim association, has made possible the access of imams to institutionalized spiritual care.

3.2. Muslim Spiritual Care in Asylum Centers in Switzerland

The second case study is the Muslim asylum chaplaincy in the Federal Asylum Centers in Switzerland (BAZ). The State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) conducted an initial pilot project at the Juch Federal Asylum Center in Zurich with three Muslim chaplains with a total staffing level of 70% (Lang et al. 2019). The positive assessment encouraged the SEM to initiate another pilot project, now nationwide, in eight federal asylum centers in the asylum regions of western Switzerland, Zurich, and eastern Switzerland in 2021 for two years. Five Muslim chaplains were employed on a part-time basis (sharing an employment level of a total of 230%). The evaluation of this project showed a very high appreciation of the Muslim chaplains on the part of the staff of the BAZ, the Christian chaplains, and the affected applicants (Schmid et al. 2022). This, in turn, led to the SEM’s decision in January 2023 to definitively introduce Muslim asylum chaplaincy in the BAZ in Switzerland. Two in-depth project evaluations stated that the project has largely proven itself. Interestingly for our question about interreligious cooperation in the diaconate, focused on diaconal spiritual care, are the SEM’s findings (SEM 2023):

- Muslim spiritual care is a “supplement” to the spiritual care offered by the national churches.

- Muslim chaplains are a valuable resource: their services are gladly used by asylum seekers; the staff appreciates their religious, cultural, and linguistic competencies; the Christian chaplains welcome their presence.

- The cooperation with Christian chaplains is positive.

- The costs of CHF 450,000/year will be included in the proposal for the revision of the Asylum Law.

By this economic estimation of CHF 450,000 per year, which leads to a voting proposal on the revision of the asylum law in Switzerland, interreligious cooperation in the field of migration in an important state organization will be secured for years to come. What does this mean from a quantitative and qualitative perspective for Muslim chaplaincy not only in BAZ but also in hospitals, psychiatric clinics, and prisons?

First to the quantitative analysis: in the meeting of 7 July 2021, the government council of the canton of Zurich dealt with the continuation of Muslim chaplaincy in the canton of Zurich. In this context, it summarizes the development and the status of the process:

“Meanwhile, the Muslim chaplaincy in the canton of Zurich is available to public institutions with a team of 17 chaplains 365 days during 24 h. The number of spiritual care missions in various Zurich institutions has been growing steadily since the founding of the association. In 2020, despite numerous corona-related restrictions, a total of 216 such missions were carried out. Since the corona crisis, the association has offered internet and telephone spiritual care. In 2020, for the first time, 25 spiritual care conversations were conducted via e-mail and 80 spiritual care conversations via telephone. Within the framework of asylum spiritual care, a total of 1202 spiritual care conversations took place in 2020”(Regierungsrat des Kantons Zürich 2021, p. 3)

The trend is upward. The annual report of the association QuaMS published the figures for 2021. A team of 17 volunteer Muslim chaplains was always available for outreach within public institutions (hospitals, clinics, blue light organizations, retirement and nursing homes, etc.). In 2021 they were called upon for a total of 319 missions in various institutions (QuaMS 2021, p. 4). According to the association, the increase in numbers and outreach is a result of networking efforts in the canton of Zurich: “Of great importance for strengthening the presence of Muslim chaplaincy within institutions is interfaith and interprofessional collaboration with Reformed and Catholic chaplaincy teams and staff within public institutions” (QuaMS 2021, p. 9).

With regard to the qualitative analysis, the diversity of topics in spiritual care, the bridging function of spiritual care workers, and the importance of continuing education are of particular importance.

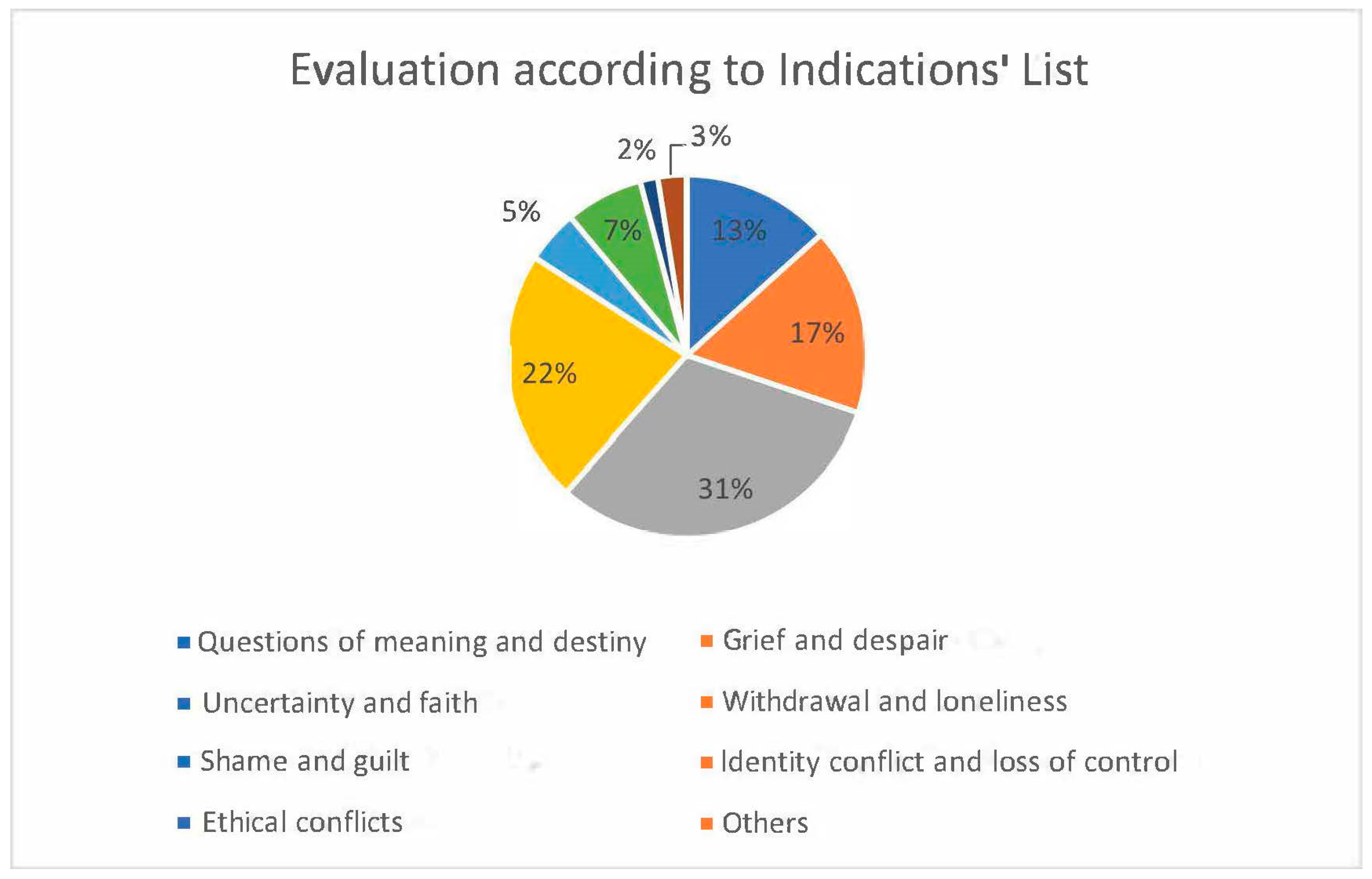

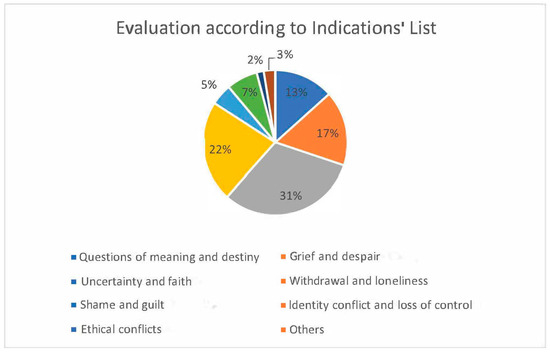

First, the diversity of spiritual care topics. The association QuaMS noted the diversity of topics for the year 2021 in the various institutions. Topics were: uncertainty and faith, grief and despair, and questions of meaning and destiny. With regard to nursing homes and psychiatric institutions, the topics were: withdrawal and loneliness, identity conflict and loss of control, and feelings of shame and guilt. The proportions of the topics can be seen in Figure 1 (QuaMS 2021, p. 8).

Figure 1.

Evaluation according to indications’ list (QuaMS 2021, p. 5).

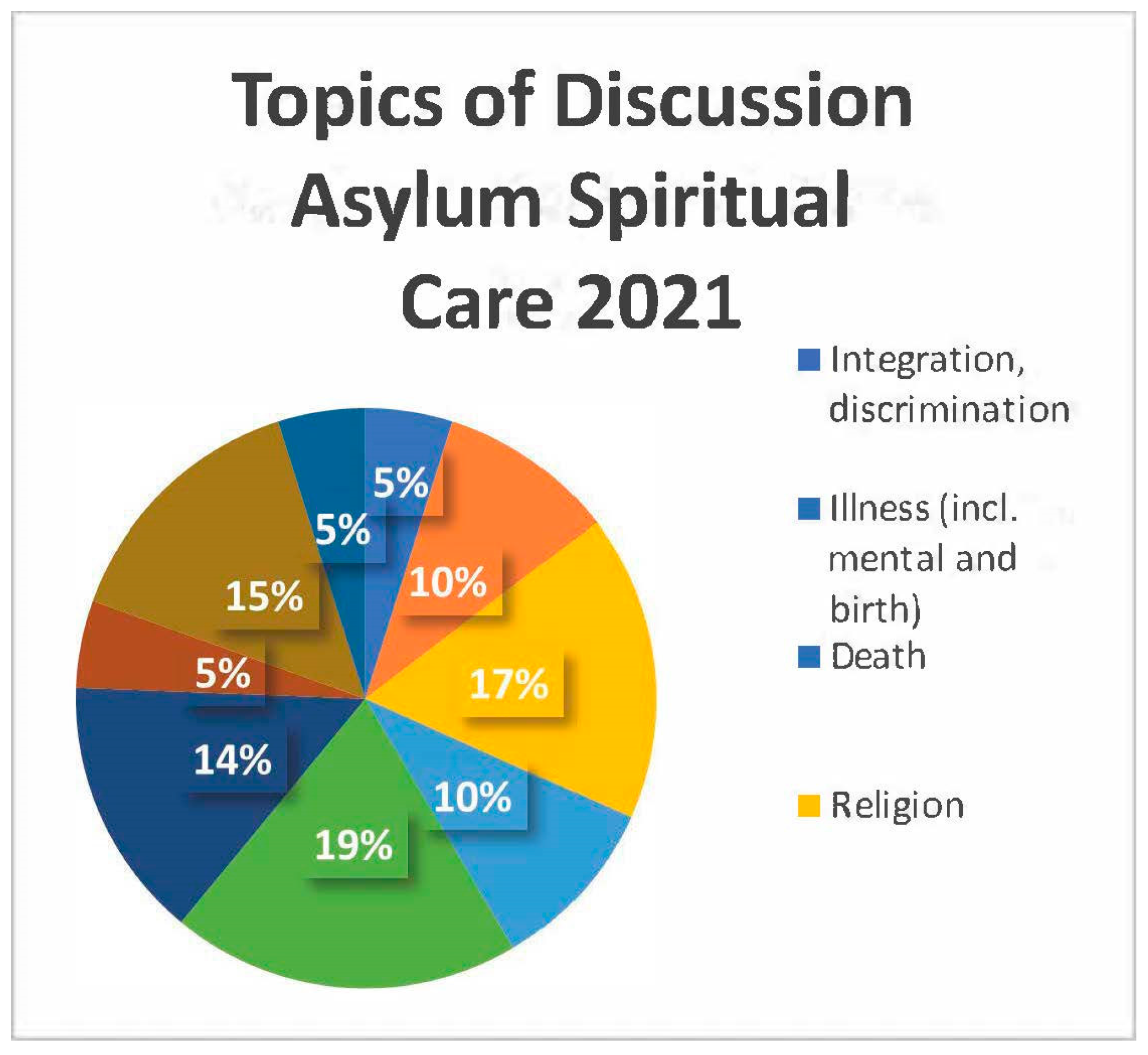

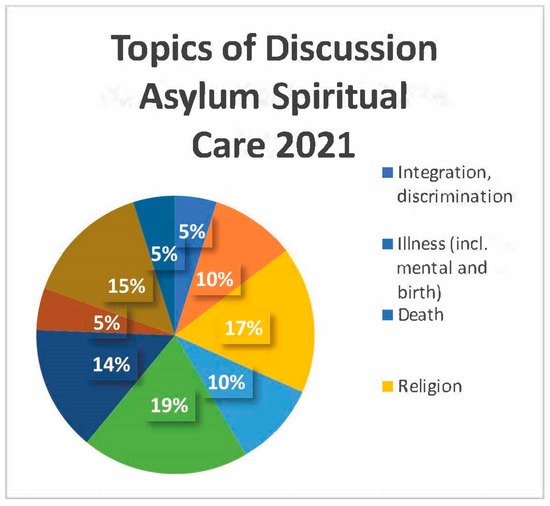

Topics of conversation at the BAZ in Zurich in 2021 can be seen in Figure 2. These are illness (including mental illness and births), organizational matters, asylum procedures, conflict, family problems, fears, sadness, flight experience, biography, traumas, religious integration, discrimination getting to know each other, going for a walk, death, corona (QuaMS 2021, p. 13).

Figure 2.

Topics of conversation: asylum spiritual care (QuaMS 2021, p. 9).

The consideration of social issues, institutional contexts, and social conditions as a prerequisite of diaconal spiritual care stands out in such compilations. Spiritual care as an offer of conversation in emergency situations proves to be diverse in social institutions insofar as complex thematic fields flow into one another and come to the fore situationally. In prisons, hospitals, and asylum centers, accelerated globalization (Baumann 2019) is reflected in the intimate four-eye conversation in a density of hybrid and fragmented moments, unavailable and fluid. That is, the biographically complex existence of the other person is reflected in the surprising set pieces of religious and cultural narratives that are written into and over each other. To be able to read these narratives in real-time is a great challenge in one-on-one conversations.

Such pastoral moments challenge spiritual caregivers. In the analysis of the first project steps of Muslim spiritual care in federal centers, the research team around Hansjörg Schmid of the Swiss Center for Islam and Society at the University of Fribourg (SZIG) establishes an interesting aspect of this challenge. On the one hand, the hybrid identity of many chaplains, as exemplified by Muris Begovic, places a high quality on their professionalism.

The researchers Lang, Schmid, and Sheikhzadegan are convinced that this quality is enormously important because some applicants in asylum centers and homes can reflect on their one-sided image of European culture and life practice in depth with the spiritual care workers. Since the spiritual care workers are often able to combine the language, culture, and religion of the applicants as well as of their own life world in their hybrid biography, they introduce the counterpart to the Swiss context more credibly than a Swiss-born spiritual care worker could do. This process can be described as a transcultural perception of bridging functions, in which the spiritual caregivers make possible interpretations of Islam related to the Swiss context and forms of Muslim existence that are capable of dialogue. In this way, spiritual care can have a stabilizing, comforting, healing, conflict-preventing, and integrative effect (cf. Lang et al. 2019, p. 371).

This bridging function as conflict prevention has a direct impact on interreligious cooperation. Muslim and Christian spiritual care workers work together in their professionalism in such a way that they can learn from each other and engage in peaceful coexistence. The joint celebration of Christmas, Ramadan, or the Islamic Feast of Sacrifice is an expression of this (cf. Lang et al. 2019, p. 371).

In this observation, a second thread of future interfaith collaboration in diaconia becomes visible: diaconia and interreligious cooperation lead to the bridging function of pastoral and diaconal workers and are thus part of peacebuilding and conflict prevention. The impact of peacebuilding cannot be described holistically enough; aspects of cultural, religious, political, power-political, and socio-political dimensions flow into one another.

Not least from the qualitative results of Muslim spiritual care in social institutions, the further training of Muslim spiritual care workers is of great importance. In the first implementation of a continuing educational course in 2018, six men and six women participated, all of whom are based in the Canton of Zurich and completed a basic course or a bachelor’s or master’s degree in Islamic studies abroad (Lang et al. 2019, pp. 372–73). Further, continuing education courses are planned, some with special competence development in the area of an Islamic-theological accompaniment of Muslim spiritual care. The continuing education courses are based on a discursive understanding of theology that allows for different attributions of meaning and alternative options for action. The different experiences of spiritual care workers are a great resource (QuaMS 2021, p. 22).

In various workshops, the phenomenon of denominationality is placed in the interreligious framework. Under denominationality, the different approaches in the religious tradition (Sunite/Shiite) are considered, as well as the different imprints of the cultural contexts. Thereby questions about the identity of Muslim spiritual care are not suppressed at the cost of possible appropriation of others (QuaMS 2021, p. 22).

These continuing educational courses attest to a strong intertwining of theory and practice, as set as a premise in diaconal studies (Sigrist 2020, pp. 24–25).9 (Diaconia and interreligious cooperation, which is a third thread, has resulted in a changed professional self-understanding of pastoral and diaconal workers).

3.3. Multifaith Spiritual Care in the Swiss Armed Forces

As of 1 January 2023, Imam Muris Begovic and Jonathan Schoppig, who is employed in the area of education and prevention at the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities (SIG) and also a lecturer at the Swiss Distance Learning University, will officially work in the Swiss Army alongside their Christian colleagues. “Swiss Army Chaplaincy on the Way to a Multifaith Future” (Reber 2020, pp. 65–82) is set in resonance with the changing religious landscape in Switzerland because it is a militia army. “Switzerland’s army is a reflection of society because of its militia organization.” (Reber 2020, p. 65). In connection with the training of army chaplains with Jewish and Muslims in the spring of 2022, the Defense of the Armed Forces communication in December 2022 states that army spiritual care has adapted to social developments over the centuries since its inception. The principle is that army spiritual care workers are there for all members of the army. It is obvious that the army has opened up the function of army spiritual care in recent years. In the spring of 2022, the first army spiritual care workers of Jewish and Muslim backgrounds were appointed. As service insignia, the army has chosen a Christian cross, a Muslim crescent, and Jewish tablets of the law (Marquis 2022).

The new regulation has also been positively received by the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities (SIG). Secretary-General Jonathan Kreutner explains, “It is very pleasing that the recognition of Jewish members of the army can be underlined with their own functional badge.” Muris Begovic of the Federation of Islamic Umbrella Organizations Switzerland (FIDS), responsible for the area of spiritual care and himself one of the new army chaplains, in turn, says: “With my task, I have the openness to accompany all army members pastorally, with the function badge the specific competence and background are emphasized. It reflects the unity in diversity of the Swiss Army” (Marquis 2022).

This growing religious diversity is not only a challenge for the Swiss Army. Army chaplains in the Netherlands, Canada, France, Great Britain, Austria, and Norway are looking for new ways to deal with religious communities and cultural diversity (Inniger 2019, p. 88). Army chaplain Matthias Inniger defines five principles for this interreligious-oriented army chaplaincy: (1) commitment to interfaith dialogue; (2) the unifying commonalities of all members of the Armed Forces in their different religions; (3) respect for personal religious attitudes; (4) encouragement to stand by one’s personal beliefs; and (5) acting as a bridge between members of the Armed Forces of all churches and religions (Inniger 2019, p. 91).

According to Inniger, this outline, referred to as the “Multifaith Army Chaplain Model,” aims to “provide appropriate care to all members of the Armed Forces while promoting religious peace” (Inniger 2019, p. 92). With regard to the army chaplains themselves, he states that army spiritual care workers can take a stand on all general pastoral care issues. According to Inniger, spiritual care workers, regardless of their faith, are generalists. With a view to the parable of the Good Samaritan, they perceive the purely humanitarian dimension of helping those affected. Inniger calls this a service from person to person, which has an important personal resource in one’s own faith (Inniger 2019, pp. 92–93). In this approach of Inniger’s, the focus is fully directed to the image of the bridge builder. Diaconia and interreligious cooperation take place in the form of bridge-building between Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, or even humanist spiritual care workers with their troops (Inniger 2019, p. 94).

Muris Begovic describes this spirit of interfaith cooperation this way, “With my service, I also want to give something back to society, and I want to contribute to religious peace, mutual understanding, dialogue, and unity in diversity” (Begovic 2022). This implicitly thematized bridging function of chaplains, which already appeared in the Muslim chaplaincy in asylum centers, obtains a special coloration through the federalist cantonal structure in Switzerland. Begovic, as a member of a Muslim community, is not a member of a religious community recognized under public law in the canton of Zurich.10

The Swiss Armed Forces thus become a research laboratory for diaconal spiritual care in interreligious cooperation in that they cannot per se exclude members of certain denominations and religious communities from spiritual care in the Armed Forces, whether on the part of the army chaplains or the part of the applicants. In practice, imams, rabbis, and pastors are responsible for the emergency situation of the applicants regardless of their religion and denomination: an imam can help a Reformed soldier in his personal relationship crisis, or a Reformed pastor can support a Muslim soldier in the execution of his religious Ramadan obligation. Therefore, since March 2020, new rules and objectives have been in force in the armed forces to address these challenges. These new rules of the game and goals are oriented to the transformation of the religious map in the armed forces. They value and respect the peculiarities of the respective members of the armed forces and direct attention to values that are shaped by Switzerland’s Christian tradition, such as justice, freedom, equal treatment, solidarity, tolerance, and diversity (Schweizer Armee 2022, p. 3).11

Who can be recruited for this service? According to Article 11 of the directives, these are men and women who complete the required basic training in the army, have appropriate theological and pastoral training, and can present a letter of recommendation from the religious community or churches. In addition, they must share the principles of army spiritual care. (Schweizer Armee 2022, p. 5). The current technical course for training in army chaplaincy includes 29 participants, one of whom has a Muslim background and two of whom have a Jewish background (Schmid 2020). Samuel Schmid, Chief Army Chaplain, states with regard to the interreligious cooperation of the army chaplains: “Our cooperation is very comradely, respectful, and appreciative. It is open to each other’s opinions, but at the same time committed to our shared values and mission for the benefit of the armed forces” (Schmid 2020).

In this volume, essential aspects of diaconal science bundles under “cultural coherence” appear (2.2.): openness towards the foreign is combined with the shaping of one’s own identity into common values in the diaconal pastoral mission towards the other. Diaconia and interreligious cooperation, whicha fourth thread in its cultural coherence, generates common values in its diaconal mission, such as tolerance, respect, openness, self-esteem, etc.

4. Four Diaconal Threads of Interreligious Cooperation

From the theoretical reflections and the practice analyses from three federally different structures in Switzerland, four important threads have been spun for the question of interreligious cooperation in diaconia. Thus, the image of the religious landscape of Switzerland as a patchwork of exclusively religious minorities has been transferred to diaconal-pastoral practice. This fourfold twisted thread, to remain in the image, will in the future embroider the pattern of the diaconal mission of the churches in interaction with actors of different religious affiliations.

Diaconia is understood as the Christian-motivated, interpreted, and justified diaconic practice as a form of general helping action, which is institutionalized by the church or organized in diaconic enterprises. On the one hand, this diaconal practice considers the addressees and applicants with their cultural and religious imprints, which have become plural and diverse. On the other hand, the diaconal mission can only be fulfilled in cooperation with members of other denominations and religions because social institutions and organizations are a reflection of a society that has become plural.

Finally, in order to further expand the picture of a plural society as a colorful patchwork of religious minorities, 50 years ago, it was sufficient to weave the fabric of spiritual care and diaconia with the two threads of the Protestant Church and the Roman Catholic Church; today these two threads are joined together to form the ecumenical, Christian strand of helping action, in order to be twisted together by other religious communities to form a colorful thread of interreligious cooperation.

In addition, the two materials of spiritual care as a helping one-on-one conversation on existential questions of life and of diaconia as a church- or diaconically organized social work in the community overlap more and more. The Muslim patient wants to die at home, just as the outgoing Catholic old woman wants to be cared for at home. It is precisely in this shift away from inpatient to outpatient care that the socio-spatial embedding and the close social space are once again becoming the focus of professional help (Sigrist 2020, pp. 71–79).

Social space, first, has become plural in the Western European context. Interreligious cooperation is part of the fabric of professional assistance. Second, the social space has become fluid in the interaction of welfare pluralism. Different actors from the state, the economy, and the neighborhood can launch initiatives in social hot spots. Thirdly, this social space has become a carpet in which Christian and other religious pastors and social workers weave the fabric of charity and humanity with their fourfold twisted thread. This thread consists of the following four sub-threads:

- Diaconia and interfaith cooperation lead due to the intercultural transformations to the participation of pastoral and diaconal workers of different religions.

- Diaconia and interreligious cooperation leads to the bridging function of pastors and diaconal workers and is thus part of peacebuilding and conflict prevention.

- Diaconia and interreligious cooperation results in a changed professional self-understanding of pastoral and diaconal workers.

- Diaconia and inter-religious cooperation, in its cultural coherence, generate common values in its diaconal mission.

What prevents us from taking this thread in our hands and, for God’s sake, from bravely and courageously beginning to weave and embroider again and again?

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I thank my research assistant, Ph.D. student Isabelle Knobel, for editing in translating the text. |

| 2 | All quotes in this article were translated from German into English by the author. |

| 3 | Switzerland is divided into different regions called Cantons. The churches are organized within these Cantons. |

| 4 | Available online: www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/sprachen-religionen/religionen.html (accessed on 19 February 2023). And bfs.admin.ch. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/sprachen-religionen/religionen.assetdetail.23985049.html (accessed on 16 February 2023). |

| 5 | If one takes a look at the figures of the census since 1850, this transformation of the Swiss religious landscape, which can hardly be overestimated, becomes even more obvious: cf: bfs.admin.ch. Available online: https://www.census1850.bfs.admin.ch/de/religionslandschaft.html (accessed on 16 February 2023). |

| 6 | For an overview of these Christian reasonings, see (Rüegger and Sigrist 2014). |

| 7 | Also summarized online: https://www.zh.ch/de/sport-kultur/religion.html (accessed on 19 February 2023). |

| 8 | To obtain further information on those two: https://swissvotes.ch/vote/547.00 (minaret initiative, accessed on 19 February 2023) and https://www.humanrights.ch/de/ipf/menschenrechte/religion/kopftuchverbot-oeffentlichen-schulen (headscarf debate in Switzerland, accessed on 19 February 2023). |

| 9 | This can be read in (QuaMS 2021, p. 23). |

| 10 | On the legal situation of religious communities, see (Reber 2020, p. 73). |

| 11 | See Article 8 of the “Directives on advice, guidance, and support for the Army Chaplaincy, the Armed Forces Psychological-Pedagogical Service and the Armed Forces Social Service”. |

References

- Baumann, Max Peter. 2019. Transkulturelle Dynamik und die kulturelle Vielfalt musikbezogenen Handelns. In Transkulturelle Erkundungen. Wissenschaftlich-künstlerische Perspektiven. Edited by Ursula Hemetek, Daliah Hindler, Harald Huber, Therese Kaufmann, Isolde Malmberg and Hande Sağlam. Wien, Köln and Weimar: Böhlau, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Begovic, Muris. 2022. Sdt Muris Begovic, angehender Armeeseelsorger mit muslimischem Hintergrund, 05.Mai 2022—Technical talk at the technical course A Armeeseelsorge TLG A AS 2022. Available online: https://www.vtg.admin.ch/de/armee.html (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Bobert-Stützel, Sabine. 1995. Dietrich Bonhoeffers Pastoraltheologie. Gütersloh: Kaiser. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, Alexander, and Christoph Sigrist, eds. 2022. Gemeinwesendiakonie und Resonanz. Eine deutsch-schweizerische Begegnung. Hannover: Blumhardt-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Eurich, Johannes. 2020. Diakonie als Akteurin Öffentlicher Theologie im sozialen Nahraum. In Konzepte und Räume Öffentlicher Theologie. Wissenschaft—Kirche—Diakonie. Edited by Ulrich H. J. Körtner, Anselm Reiner and Christian Albrecht. Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, pp. 117–43. [Google Scholar]

- Götzelmann, Arnd. 2006. Zum Verhältnis von Seelsorge und Diakonie. Zuordnungsmodelle, Konzepte und Thesen auf dem Weg zu einer diakonischen Orientierung der Seelsorge. In Diakonische Seelsorge im 21. Jahrhundert. Edited by Arnd Götzelmann, Karl-Heinz Drescher-Pfeiffer and Werner Schwartz. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, pp. 18–50. [Google Scholar]

- Götzelmann, Arnd, Karl-Heinz Drescher-Pfeiffer, and Werner Schwartz, eds. 2006. Diakonische Seelsorge im 21. Jahrhundert. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter. [Google Scholar]

- Hehli, Simon. 2018. Weshalb muslimische Seelsorger in Spitälern für Kritik Sorgen. NZZ. Available online: https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/auch-islamische-seelen-brauchen-sorge-ld.1397952?reduced=true (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Inniger, Matthias. 2019. Die Schweizer Armeeseeslsorge und die Förderung des Religionsfriedens. Internationale Kirchliche Zeitung (IKZ) 109: 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Jörns, Klaus-Peter. 2007. Lebensgaben Gottes feiern. Abschied vom Sühneopfermahl: Eine neue Liturgie. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus. [Google Scholar]

- Kanton Zürich, Direktion der Justiz und des Innern Generalsekretariat. 2017. Staat und Religion im Kanton Zürich—Eine Orientierung. Zürich. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiDsszWuLX-AhUUgv0HHdRyDpYQFnoECAgQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.zh.ch%2Fcontent%2Fdam%2Fzhweb%2Fbilder-dokumente%2Fthemen%2Fsport-kultur%2Freligion%2FStaatundReligion.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1KdQLFZReUDhb-hGRCXxbW (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Kanton Zürich, Direktion der Justiz und des Innern Generalsekretariat. 2022. Staat und Religion im Kanton Zürich—Gemeinsame Schwerpunkte und Projekte von Kanton und Religionsgemeinschaften. Zürich. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiRl5_W9bCAAxUIh_0HHSMiCDEQFnoECA4QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.zh.ch%2Fcontent%2Fdam%2Fzhweb%2Fbilder-dokumente%2Fthemen%2Fsport-kultur%2Freligion%2FStaat%2520und%2520Religion%2520im%2520Kanton%2520Z%25C3%25BCrich_Gemeinsame%2520Schwerpunkte%2520und%2520Projekte%2520von%2520Kanton%2520und%2520Religionsgemeinschaften.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2ep9DbG8sPRbh9djK-dUkR&opi=89978449 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Lang, Andrea, Hansjörg Schmid, and Amir Sheikhzadegan. 2019. Von der interkulturellen Kommunikation zur transkulturellen Praxis: Fallgestützte Analysen der muslimischen Asyl- und Spitalsorge. Spiritual Care 8: 367–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marquis, David. 2022. Mit Gesetzestafeln, Halbmond und Kreuz für alle da. Kommunikation Verteidigung. Available online: https://www.vtg.admin.ch/de/armee/service/suche.detail.news.html/vtg-internet/verwaltung/2022/22-12/221220-armeeseelsorge.html (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Moos, Thorsten. 2023. Öffentliche Diakonie. Ein praxistheoretischer Zugang. In Diakonische Ethik. Systematisch-theologische Beiträge. Edited by Thorsten Moos. Stuttgart: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, pp. 165–80. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthaler, Christoph. 2005. Der Blick des Anderen. Die Ethik des Helfens im Christentum. In Ethik und Praxis des Helfens in verschiedenen Religionen. Anregungen zum interreligiösen Gespräch in Seelsorge und Beratung. Edited by Helmut Weiss, Karl H. Federschmidt and Klaus Temme. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Vandenhoeck-Ruprecht, pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Muslimische Seelsorge Zürich (QuaMS). 2021. Jahresbericht 2021. Available online: https://www.fids.ch/index.php/06/2022/jahresbericht-der-quams/ (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Peng-Keller, Simon. 2019. Spiritual Care im Gesundheitswesen des 20. Jahrhunderts. Vorgeschichte und Hintergründe der WHO-Diskussion um die ‹spirituelle Dimension›. In Spiritual Care im globalisierten Gesundheitswesen Historische Hintergründe und aktuelle Entwicklungen. Edited by Simon Peng-Keller and David Neuhold. Darmstadt: WBG Academic, pp. 13–72. [Google Scholar]

- Reber, Christian. 2020. Die Schweizer Armeeseelsorge auf dem Weg in die multireligiöse Zukunft. In Schweizerisches Jahrbuch für Kirchenrecht. Annuaire suisse de droit ecclésial. Band 24/2019. Edited by Dieter Kraus. Zürich: TVZ, pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Regierungsrat des Kantons Zürich. 2021. Auszug aus dem Protokoll des Regierungsrates des Kantons Zürich. Zürich. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiRx46cwbX-AhXthv0HHTTeDv8QFnoECA8QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.zh.ch%2Fbin%2Fzhweb%2Fpublish%2Fregierungsratsbeschluss-unterlagen.%2F2021%2F783%2FRRB-2021-0783.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0E7ahd4LRXzrvxoCaXy-c8 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Rüegger, Heinz. 1993. Kirche als seelsorgerliche Gemeinschaft. Dietrich Bonhoeffers Seelsorgeverständnis im Kontext seiner bruderschaftlichen Ekklesiologie. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Rüegger, Heinz, and Christoph Sigrist. 2011. Diakonie—eine Einführung. Zur theologischen Begründung helfenden Handelns. Zürich: TVZ. [Google Scholar]

- Rüegger, Heinz, and Christoph Sigrist. 2014. Helfendes Handeln im Spannungsfeld theologischer Begründungsansätze. Zürich: TVZ. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Hansjörg, Amir Sheikhzadegan, and Aude Zurbuchen. 2022. Muslimische Seelsorge in Bundesasylzentren Evaluation des Pilotprojekts zuhanden des Staatssekretariats für Migration. Freiburg: Schweizerisches Zentrum für Islam und Gesellschaft (SZIG). Available online: eval-muslimische-asylseelsorge.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Schmid, Hansjörg, Mallory Schneuwly Purdie, and Andrea Lang. 2018. Muslimische Seelsorge in öffentlichen Institutionen. SZIG-Papers 1. Available online: https://www.unifr.ch/szig/de/forschung/publikationen/szig-papers.html (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Schmid, Samuel. 2020. Die Vielfalt der religiösen Hintergründe stärkt unsere Kompetenz. Interview vom 6.5.2023. Available online: https://www.vtg.admin.ch/de/armee/service/suche.detail.news.html/vtg-internet/verwaltung/2022/22-05/kommando-ausbildung----die-vielfalt-der-religioesen-hintergruend.html (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Schweizer Armee. 2022. Weisungen über die Beratung, Begleitung und Unterstützung der Armeeseelsorge, den Psychologisch-Pädagogischen Dienst der Armee und den Sozialdienst der Armee“ (WBBU). Available online: https://www.vtg.admin.ch/de/mein-militaerdienst/dienstleistende/seelsorge.html#dokumente (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Sigrist, Christoph. 2020. Diakoniewissenschaft. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Staatssekretariat für Migration (SEM). 2023. Die muslimische Seelsorge wird in den Bundesasylzentren dauerhaft eingeführt. Available online: https://www.sem.admin.ch/sem/de/home/sem/medien/mm.msg-id-92717.html (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Stolz, Jörg, Olivier Favre, and Emmanuelle Buchard. 2014. Die Wettbewerbsstärke des evangelisch-freikirchlichen Milieus in der Schweiz. In Phänomen Freikirchen. Analysen eines wettbewerbsstarken Milieus Stolz. Edited by Jörg Stolz, Olivier Favre, Caroline Gachet and Emmanuelle Buchard. Zürich: TVZ, pp. 25–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tittus-Düzcan, Rabia. 2018. Spirituelle Ressourcen für eine islamische Seelsorge. Spiritual Care 7: 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucak-Ekinci, Dilek. 2019. Spiritual Care in muslimischen Kontexten. Ein Überblick über aktuelle Entwicklungen. In Spiritual Care im globalisierten Gesundheitswesen. Historische Hintergründe und aktuelle Entwicklungen. Edited by Simon Peng-Keller and David Neuhold. Darmstadt: WBG Academic, pp. 207–30. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Helmut. 2005a. Ansätze einer Hermeneutik des helfenden Gesprächs in interreligiöser Hilfe und Seelsorge. Vorbemerkungen zur Reflexion der Fallberichte. In Ethik und Praxis des Helfens in verschiedenen Religionen. Anregungen zum interreligiösen Gespräch in Seelsorge und Beratung. Edited by Helmut Weiss, Karl H. Federschmidt and Klaus Temme. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Vandenhoeck-Ruprecht, pp. 241–47. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Helmut. 2005b. Viele Stimmen mit drei Grundtönen. Einführung zu Teil I. In Ethik und Praxis des Helfens in verschiedenen Religionen. Anregungen zum interreligiösen Gespräch in Seelsorge und Beratung. Edited by Helmut Weiss, Karl H. Federschmidt and Klaus Temme. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Vandenhoeck-Ruprecht, pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Welsch, Wolfgang. 2005. Transkulturelle Gesellschaften. In Kultur in Zeiten der Globalisierung. Neue Aspekte einer Soziologischen Kategorie. Edited by Peter-Ulrich Merz-Benz and Gerhard Wagne. Frankfurt a.m.: Humanities Online, pp. 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann-Wolf, Christoph. 1991. Einander beistehen. Dietrich Bonhoeffers lebensbezogenes Glaubensverständnis für gegenwärtige Klinikseelsorge. Würzburg: Seelsorge Echter Verlag. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).